Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

|

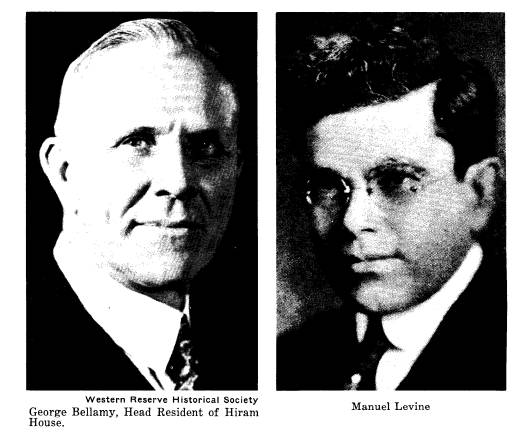

Twenty Years at Hiram House by JUDITH A. TROLANDER Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the settlement movement reached the United States. Hull House, the most outstanding and second oldest settlement, was established in Chicago in 1889. The first social set- tlement in Cleveland to actually do settlement work as such was Hiram House, founded in 1896.1 Today, however, Hiram House has been largely forgotten, partly because George Bellamy, the founder and director through- out its existence, published very little. Fortunately, Bellamy was a com- pulsive saver of papers relating to his work. Recently, his widow presented these letters, reports, notes for speeches, and other papers dating back to 1901 to the Western Reserve Historical Society. As a result, it is now pos- sible to present a fuller and more detailed picture of the significance of Hiram House in the early years of the settlement movement. George Bellamy was born on September 29, 1872, in a small town in Michigan. He was a "descendant of the Wolcott [Oliver] who signed the Declaration of Independence and who was Secretary of the Treasury and in the Cabinet of George Washington."2 Unusual for one who worked as extensively with immigrants as he did, Bellamy was proud enough of his "old family" background to become a member of the New England Society of Cleveland and the Western Reserve and also the Society of the Descen- NOTES ON PAGE 69 |

|

26 OHIO HISTORY |

|

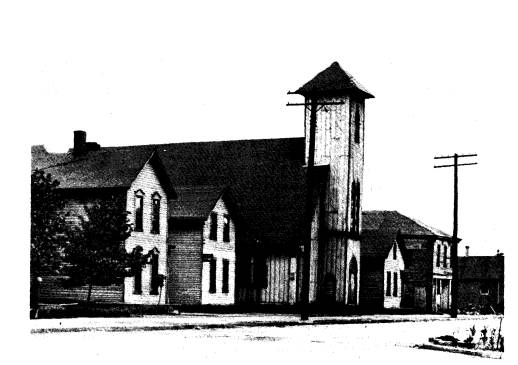

dants of Henry Wolcott, one of the first settlers of Windsor, Connecticut.3 Bellamy's immediate family had little money, and from the day George left home, he found it necessary to earn his own living. He worked his way through Hiram College in northeastern Ohio with various selling jobs and graduated in 1896. The idea of founding a settlement, or neighborhood house in a congested area that would provide various social services to the community, was con- ceived by Bellamy while still in college. Two years before graduation, he met Graham Taylor who had just founded the Chicago Commons settlement and had written the Y.M.C.A. Handbook used by members of a club study- ing sociological questions at Hiram College. Later Bellamy was to credit Taylor with "the motivation of my life work."4 In the spring of 1896 this club voted to study the need for a social settlement in Cleveland. A quick trip to Cleveland convinced them that the need did in fact exist. In the summer Bellamy and two other members of the club moved to Cleveland to begin a settlement which they named Hiram House because the first residents were graduates of Hiram College. Four others joined them to make an initial group of seven residents, or social workers who lived in the neighborhood they were trying to help. Bellamy's financial resources during the first few years were slender. To finance the fledgling project, he solicited contributions, but the largest amount given by anyone during the first year was $75.00.5 He rented a |

|

HIRAM HOUSE 27 small house which provided only enough space for a nursery and the clubs, forcing him to find living space across the street. In the spring, the settle- ment was evicted from its first home because too many people were using the house and causing too much wear on it, in the opinion of the landlord. The rent had been paid, but Bellamy had fallen behind in paying salaries, including his own. In order to buy a badly needed suit, he had to take a temporary job collecting pledges for the Anti-Saloon League. By 1898, the settlement in its second location had expanded to include nine clubs, a nursery, and a kindergarten with sixty-five children enrolled.6 Also, with incorporation in 1898, the house began to receive gifts from prominent Cleveland philanthropists, led by Samuel Mather, and in 1899 ground was broken for its own building near Twenty-seventh and Orange. Bellamy was then at last able to relax secure in the knowledge that Hiram House was going to have a place where the settlement work could proceed. To Bellamy and many of his contemporaries, the key to social problems was the environment--improve the environment and social problems will be alleviated, or so they thought. Specifically, Bellamy blamed congestion in the slums for health problems, law-breaking, low morals, and truancy. In response to these and other social problems, settlements offered facilities and programs which were intended to be of a remedial nature. They also supported the rehabilitative efforts of other charities and organizations, and they became closely connected with the social gospel and progressive |

28 OHIO HISTORY

movements. However, from the beginning

of the first settlement in the

world, Toynbee Hall founded by Samuel

Barnett in London, the settle-

ment approach differed from that of

other organizations. Early leaders of

the settlement movement, such as Stanton

Coit (founder of the first settle-

ment in the United States), Jane Addams,

Graham Taylor, and Robert

Woods of South End House in Boston, stressed

the importance of residence

in the neighborhood to be helped. For

example, Taylor talked about resi-

dents identifying themselves with the

poor by actually living among them.

In return for the help which they gave,

the residents would receive insights

into the lives of the poor. In fact,

when Taylor began in 1894, he thought

of Chicago Commons "primarily as a

'social observatory' and 'statistical

laboratory' for his students."7

He added other programs as the need for

them became apparent. Bellamy attempted

to put into practice as much of

this philosophy as possible.

The usual procedure in determining the

needs of an area was to make a

study of some aspect of the

neighborhood, such as housing, and then, armed

with the facts, seek community support

through publicity in order to get

local government legislation to correct

the situation. Hiram House made

such a study in 1901 on housing. At the

time of the report the neighbor-

hood, bounded roughly by East Fourteenth

and East Fifty-fifth Streets,

Carnegie and Broadway, was predominantly

Jewish, Russian immigrants

in the majority. The survey showed that

there were two types of slum

dwellings-the tenement, a large building

originally divided into apart-

ments, and the small house, crowded two

or more onto one lot. The latter

type was more common in Cleveland.

Garbage boxes, sheds, and manure

heaps occupied the space on each lot not

taken up by the small frame

houses, which were often partitioned to

accommodate two or more families.

The following houses were not the worst,

but only representative:

An investigation of a piece of property

37' by 140', with two three-

story buildings [revealed]: Three

closets in the yard with water connec-

tions but the water don't run. Sixteen

people live in the front house

and seventeen in the rear. No bath

rooms. Yard is built up with sheds.

These sheds are on the fifteen per cent

of the ground space not occu-

pied by the buildings. House in the rear

has wooden balcony for fire

escapes. A fire trap. Heated by stoves.8

This report summarized the results of

the first study of slum housing

made in Cleveland. It urged that new

laws be passed to prevent the worst

types of slum housing and the

enforcement of laws regulating housing

where they existed. The report was

prepared for the Cleveland Council of

Sociology and then was presented to the

mayor.

Who were the people who lived in these

substandard houses? They were

mostly immigrants, first Jews, then

Italians, but also Slavs, Poles, and oth-

ers from southern and eastern Europe.

Their families were often large,

which meant that neighborhood schools

were crowded. Poverty was the

rule. In many cases, family ties were

loose, reflecting an estrangement be-

tween the foreign-born parents and their

American-born children.9 Street

gangs flourished. Deserted wives or

widows struggling to support them-

HIRAM HOUSE 29

selves and their children on sweat shop

wages were common. Income for

some families was as low as $2.00 to

$3.00 per week.

One such woman was a Russian-Jewish

immigrant who lived in a one-

room apartment on highly congested

Cherry Alley. She regularly left her

three children at the Hiram House day

nursery for five cents per day per

child. She then went to a factory and

carried home "heavy loads of boys'

suits . . . and then returned them to

the factory when the labor on them

had been finished. She toiled all day

sewing buttons on the suits, being

paid one cent for each suit she

completed."10 Such people were typical of

Hiram House's neighbors.

Another of the settlement's efforts to

improve the neighborhood environ-

ment focused on the dance halls. Bellamy

revealed his methods in the fol-

lowing candid letter to another reformer

in West Virginia:

We made an investigation of the dance

halls .... We kept it quiet

from the papers or any one else,

employed a woman, paying $100.00

per month, furnished escorts to her, and

she made a thorough study of

the dance hall situation. We called in

the mayor, two or three good

councilmen, and a few men whom we could

trust, and read the report

and said it had been kept absolutely

quiet, and if they would go ahead

and put the ordinance, which we had

already drafted, through the

council, we would let them get the

credit of the good work done. Then

we secured the appointment of an excellent

man to put into execution

the requirements of the ordinance. That

is the best way to go after

these things.11

The resulting ordinance was passed in

1911 and established an inspection

system which was designed to improve the

moral tone of the halls. Dance

hall inspectors had the authority to

censor "all freak or immodest danc-

ing," eliminate "objectionable

advertising," maintain order, and prohibit

children under eighteen from the

premises unless "properly chaperoned."

Although this ordinance dealt only

indirectly with the selling of liquor, a

1913 state law prohibited

"temporary bars in the same building as dance

halls."12 By 1915, Hiram

House had evidently developed some dissatisfac-

tion with the municipal inspector for he

was invited to one of the neighbor-

hood's dances in order to "show him

how a dance should be run."13 The

settlement recognized that the mere

passage of an ordinance did not al-

ways produce sufficient and lasting

change, and so Hiram House kept a

vigilant eye on the enforcement of this

regulation in the years that followed.

In 1912, with reformer Newton D. Baker

as mayor, Bellamy was active

in politics as chairman of the campaign

committee for the Municipal Play-

ground Bond Issue. The committee sought

$1,000,000. The issue failed to

pass that year, but in 1913 Bellamy

again sought to place the bond issue

on the ballot. This time Mayor Baker

opposed the move, saying that he

doubted the issue would pass although he

favored more money for play-

grounds.14 At the same time,

Baker was trying to get Bellamy to accept

the post of commissioner of recreation.

Bellamy hesitated, but nine months

later took the job on a temporary basis

for the following public-spirited

reasons:

30 OHIO HISTORY

The Department of Public Recreation

seems to be in a bad way and

the Council refused to appropriate any

money to carry it on, for they

want McGinty, an ex-pugilist and

saloonkeeper to be appointed Direc-

tor of Recreation. In order to save the

day until the Mayor comes back,

I accepted the temporary appointment and

have already appointed

playground directors so that our

playgrounds will start on June 29th.

In the meantime . . . there will be

quite a fight on and I rather antici-

pate considerable enjoyment from it,

although it is going to mean a

great deal of extra effort.15

Although obviously interested in the

recreation position, Bellamy was

forced to be practical about money

matters and did not stay in the public

recreation department. Francis F.

Prentiss, chairman of the Hiram House

board, had recognized his financial

need. When Bellamy had been offered

the job of secretary of the Playground

Association in 1910, Prentiss held

out the possibility of a salary increase

and mentioned picking up the deficit

on Bellamy's farm if he would not leave

the settlement.16 By the depres-

sion years Bellamy's salary reached

$7500 plus "other benefits"--Samuel

Mather and others also paid for the

college education of his daughters.

Even so, Bellamy probably made less

money than if he had gone into busi-

ness with his ability as a salesman and

fund raiser.17

The settlement's efforts on behalf of

playgrounds, housing, and recrea-

tion helped to produce some constructive

results. A survey of the neighbor-

hood in 1899 showed that it lacked

playgrounds, public gyms, parks, and

was deficient in school facilities. But

by 1912, through its cooperation on

civic committees and by means of other

activities, Hiram House had the

right to claim partial credit for the

following results:

Better housing laws, the establishment

of public baths, the improve-

ment of school conditions, the

establishment of Juvenile Court, the se-

curing of a dance hall ordinance, the

reduction of hours of labor for

women and children in factories, the

extension of the school age of

children, and the establishment of

better public recreation.18

Also, Hiram House preceded the Board of

Education in the introduction

to Cleveland of new types of education.19

While the public schools hesi-

tated, the settlement made available a

kindergarten, domestic education,

and manual training classes. The

kindergarten and nursery were among

its first activities. In 1900 there were

estimated to be 2500 children in the

neighborhood under six. The House

secured a teacher trained at Graham

Taylor's Institute in Chicago, a school

which emphasized the theories of

Pestalozzi and Froebel. By 1912, the

public schools had established their

own kindergartens, but since they could

not accommodate all the children,

Hiram House still temporarily donated

space for this purpose while the

school board paid the teachers' salaries

and furnished supplies.

Sewing and cooking classes began at

Hiram House in 1898. In the early

1900's, one of the houses adjacent to

the settlement was bought and con-

verted into a "model cottage,"

where classes were conducted in a realistic

HIRAM

HOUSE 31

home setting. Throughout the first

twenty years, Hiram House continued

to offer domestic education courses of

this type.

In 1901, the manual training department

was organized. Using the do-

nated presses, the students printed all

Hiram House publications, plus

tickets, stationery, and other items.

Printing proved to be the most popular

subject offered. Other classes during this

period were given in bookkeep-

ing, stenography, mechanical drawing,

carpentry, metal work, telegraphy,

and machine shop. Thus Hiram House

partially filled the gap until voca-

tional education was adopted by the

public schools.

Less successful than manual training and

domestic education were the

adult education classes in academic

subjects. In 1898, Hiram House offered

twenty different classes in such

subjects as general history, Latin, Greek,

French, English literature, and

arithmetic. Enrollment was small. For ex-

ample, only two boys chose to study

Greek. There were, however, three

students qualified to enter college by

1900. The main problem was the

fact that its volunteer teachers did not

always appear to teach their classes.

The program may have been too ambitious

for the young settlement. What-

ever the reason for failure, Hiram House

switched from academic to manual

training classes in 1901.

Some of the early adult education

classes were in English for immigrants,

and these were not discontinued. It was

in connection with this activity

that Hiram House had a hand in the

success story of Manuel Levine. Levine

was a sixteen year old Russian-Jewish

immigrant who arrived at Hiram

House early in 1897. He wanted to learn

English so George Bellamy found

a tutor who worked with him three

mornings a week without charge. In

the fall of 1897, the director helped

the young man get into the Western

Reserve University Law School. He almost

"flunked out" during his first

year because of his language problem,

but in three years he graduated

among the top students in his class. In

1899, Levine joined the Hiram

Social Reform Club to which he belonged

until his death in 1939. Bellamy

claimed, "Levine often attributed

much of his educational and debating

ability to his experiences in this

club."20 Levine also organized citizenship

classes at Hiram House and spent his

Saturday nights teaching immigrants.

He was appointed judge on the Police

Court in 1908 and worked to stop

the unethical practices in which lawyers

often took advantage of immi-

grants. He went on to help establish the

Municiple Court of Cleveland, the

first conciliation court in America, and introduced the

probation system

in Common Pleas Court. He was appointed

a judge of the District Court

of Appeals in 1922 and became its chief

justice in 1932. In addition to this

distinguished legal career, Newton D.

Baker referred to Levine as "The

Father of the Cleveland Immigration

Bureau."21 Although Levine's was

the outstanding success story of Hiram

House, there were others who made

considerable progress after they left

the settlement. Some early members

of the Webster Debating Club attended

the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, Case School of Applied

Science, Western Reserve University

Medical School, Cleveland Pharmaceutical

School, and two law schools.22

|

32 OHIO HISTORY The Cleveland Immigration Bureau, mentioned in connection with Le- vine, was supported also by George Bellamy. The Bureau was established in 1913 with three aims: to meet immigrants on arrival, to get immigrants out of difficulty with the law, if necessary, and to further their Americani- zation. To accomplish the third objective, the Bureau organized a course to train teachers as instructors in English for immigrants. Through its ef- forts, over 30,000 immigrants attended English classes and over 4,000 en- rolled in citizenship classes at Hiram House as well as other cooperating settlement houses in Cleveland. |

|

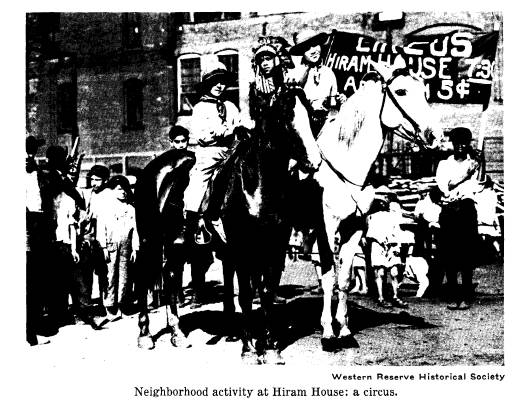

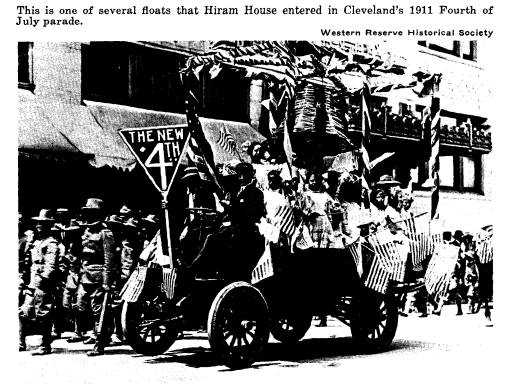

A unique feature of the settlement approach was the principle of social interaction. It was the hope that some of the problems of the people would be alleviated by this means, with the settlement house providing the com- mon meeting place. The first club providing such interaction at Hiram House was the Buckeye Literary and Debating Club, dating back to the summer of 1896. It was composed of Russian-Jewish boys. The Social Re- form Club, which Manuel Levine praised, grew out of this club. The group discussed current topics and invited such prominent Clevelanders to speak as President Thwing of Western Reserve University and Mayor Tom L. |

HIRAM

HOUSE 33

Johnson. The original members were

students who, as the years passed,

continued to meet as adults. Many early

settlements had clubs such as this

one.

Not all the groups were intellectually

oriented. Girls' clubs were organ-

ized around such activities as music,

dramatics, basket-weaving, doll-dress-

ing, and dancing. Boys' clubs often

emphasized athletics. Both the Camp

Fire Girls and the Boy Scouts met at

Hiram House. There were also sev-

eral bands and choruses and arts and

crafts clubs, as well as purely social

clubs. Some of the social activities

were not organized functions. In the

early days, neighborhood receptions were

held often and were continued

later on special occasions. Thursday

nights in the summer a band concert

was scheduled on the playground.

Programs featuring stereopticon lectures

and later moving pictures were also

given. The game room and gymnasium

provided further facilities in a

neighborhood starved for wholesome public

recreation. To acquaint people with all

its activities, Hiram House Life

was published bi-monthly beginning about

1900. The Hiram House Echo,

which was started to help club members keep

in touch with each other,

appeared in 1910.

Of its many activities, the workers at

Hiram House were proudest of the

playground program. The play area was

the gift of Mrs. Samuel Mather

and was installed after the permanent

building was constructed in 1900.

This was the first playground to be

lighted at night and was cited years

later "as the best programed play

space in the land."23 Very early Bellamy

discovered that the children needed

adult supervision, and he was among

the first to develop the job of

playground director.

About 1906, he began the Progress City

program which eventually re-

ceived national recognition.24 The

children were organized into a govern-

ment similar to Cleveland's, with a

mayor, city judge, and other officials.

Each child had a job, such as clean-up

worker (Sanitation Department),

for which he received play money which

was then put into the Progress

City Bank. At the end of the summer, a

store such as Halle's would donate

goods that the children could purchase

with their play money. The children

went so far as to imitate government

corruption. Occasionally mayors stole,

judges were bribed, and bankers

embezzled. The children, however, "im-

peached and punished the offenders . . .

with such a vengeance" that Pro-

gress City was considered an excellent

learning experience.25 Bellamy's

commitment to the value of recreation is

further revealed in his only

published writings--one article urging

that playgrounds be open in the

evening and the other promoting

wholesome recreation as is a builder of

character and preserver of morals.26

The "neighborhood visitor" is

a key figure in the early settlement move-

ment, and this person performed many of

the functions of the present day

caseworker. Before 1907, neighborhood

visiting was the responsibility of

all the workers at Hiram House. With the

addition of Margaret Mitchell

to the staff in 1908 neighborhood

visiting received special emphasis.27 Miss

Mitchell found herself doing a variety

of things, from finding work for

the unemployed to settling marital

squabbles. When social agencies called

34 OHIO HISTORY

to ask the settlement to look after a

neighbor, the job was usually delegated

to her. She also got referrals from

Juvenile Court. Consequently, she be-

came closely acquainted with many people

in the neighborhood. Her re-

ports present a vivid picture of their

personal problems. This family was

one such case:

The family is Hungarian, there are three

little children, the father

is a sober, hardworking machinist and

the mother is a drunkard. As

soon as the husband leaves for work, she

sends ten-year-old Arthur or

seven-year-old Annie for beer or

whiskey. When they return, she loses

no time in getting drunk. Then the baby

may lie neglected for hours,

the children go dirty and hungry . . .

If she could not get her drink

at home, she had friends who would

gladly treat and she would

often go away in the morning and be gone

all day. [The children were

left in charge of the house, and

unsupervised, they were also starting

to drink.] The mother was sent to the

State Hospital, but at the end of

three weeks, in despair because there

was no housekeeper at home and

in hopes that his wife would keep the

promises she made, the husband

brought her home and in a few days the

situation was as bad as ever.

Threats were made, but these did no

good, except to make the mother

more cunning .... We decided that

patient work was the only thing

that might do any good. For some time, I

called at the home almost

every day and tried to encourage the

mother to a better performance

of home duties--letting her know, too,

that we were keeping a watchful

eye on her. Tile home conditions seemed

to be improving and the hus-

band said his wife was doing better, but

I have not seen the family

since New Years, so I can not tell how

long she held out.28

This case shows the frustration and

inconclusive results that Margaret Mit-

chell faced in much of her work.

Another knotty problem that Miss

Mitchell encountered was that of the

neighborhood gang. There were a number

of such groups made up of boys

whose parents had little interest in or

control over them. One rowdy gang

lived independently of their families in

a shanty they had constructed be-

tween the blast furnaces and tile

railway. They supported themselves by

stealing. The youngest member was six. A

great deal of work was spent

drawing it into Hiram House; but mainly

due to the efforts of Margaret

Mitchell, the settlement succeeded.29

More representative than this group was

"Joe the Robber's Gang" which

had long caused a great deal of trouble

in the neighborhood, including the

Hiram House playground. They would enter

the playground at one end,

start a series of fights and break up

games in progress, and be out the other

end before they could be caught. After

much work on the part of Miss

Mitchell, the gang was persuaded to come

to Hiram House and form a

club. The boys, of course, elected Joe

president, but Margaret was elected

treasurer, not out of gratitude, but

"because the boys said she would not

shoot craps with the money." The

club also elected two sergeants-at-arms

"to literally 'bat' the members

into some semblance of order." In one in-

stance trouble followed in the gym as a

result of a game between some

|

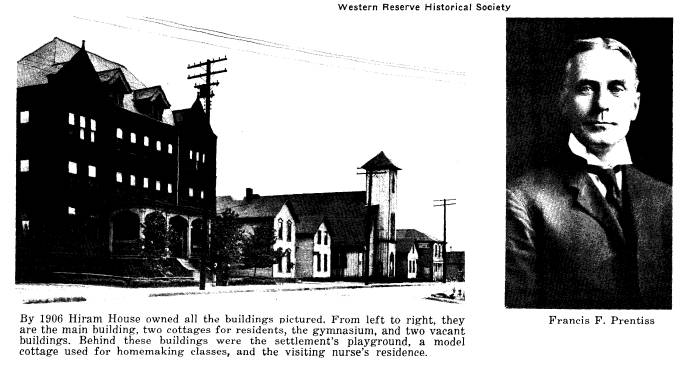

HIRAM HOUSE 35 Jewish boys and this Italian gang. The gang threatened a fight outside the building, a knife was flashed, and the police were called; but no fight ensued before the police arrived. After four months of working with the group, including two months as a club, the boys' behavior improved. They fol- lowed the rules in the gym, did not threaten other boys, and occasionally mixed with them. The boys reduced their gambling; and Joe said he had cut his smoking down to one cigarette a day and was playing "hooky" less. Here, the success of Hiram House was more definite. Before coming into contact with the House, the gang had been largely independent of adult supervision. The settlement, however, changed that and the boys' energy was then channeled more constructively. In cases such as this, it was Mar- garet Mitchell's main job to go out into the neighborhood and make the initial contacts. Thus, on the neighborhood visitor fell some of the toughest and most challenging assignments.30 During its first twenty years Hiram House was supported in a variety of ways, reflecting a general transition relative to the collection and spending of private donations to public charities. In the beginning, the settlement relied on private contributions to pay expenses; all funds were personally solicited by George Bellamy or his associates and the contributors were personally acquainted with the House. At the end of this period, organized philanthropy became prevalent, and at a later date an all-powerful Welfare Federation with its United Appeal was formed. As has been mentioned, George Bellamy was a master at the art of fund- raising. He once remarked to Francis F. Prentiss, "As a boy, our church |

36 OHIO HISTORY

always used to get me to sell

tickets."31 By 1899, Bellamy had gone from

selling church tickets to soliciting

large sums of money from Samuel Mather

and John D. Rockefeller. The list of

contributors to Hiram House soon

read like a "Who's Who in

Cleveland." The major figure who supported

the settlement with his philanthropy was

Francis F. Prentiss. He was also

chairman of the board during the last

ten years of this period under study.

A busy man, Prentiss was president and

general manager of the Cleveland

Twist Drill Company, president of the

Cleveland Chamber of Commerce

in 1906, and a director of the Cleveland

Life Insurance Company. During

his lifetime, he headed numerous civic

and philanthropic enterprises. In

addition, he was a trustee of both

Western Reserve University and Case

School of Applied Science, president of

the Cleveland School of Art, and

vice-president of the Western Reserve

Historical Society. Prentiss seemed

to derive satisfaction from both

donating and soliciting funds for Hiram

House. He made a substantial

contribution each year while helping Bellamy

get more money from others. In addition

to money, Prentiss made a Christ-

mas gift of 400 to 700 or more pounds of

candy to the neighbors of the

settlement. This gift became an annual

custom extending from 1906 to

1931, when Mrs. Prentiss, the former

Elizabeth S. Severance, had to un-

happily inform Bellamy that she could no

longer afford to keep it up.

As a recipient of many requests for

donations and an associate of other

contributors of large amounts, Prentiss

knew from first hand experience

what it was like to be asked for money.

Through him Bellamy became

even more aware of the fine techniques

of fund-raising. For example, in

1912, he very much wanted W. S. Tyler,

head of the Cleveland Wire Works,

to name Hiram House as a beneficiary in

his will. Before typing a letter

to Tyler with this request, Bellamy

consulted Prentiss, who replied:

With reference to bequests, I think a

printed circular letter to con-

tributors would be better than a

typewritten one. My reason for this

is than none will feel they were singled

out for special consideration:

for instance, if you should send a

typewritten letter to Mr. Tyler he

might feel you were anticipating too

rapidly, and be offended, and the

same true of others.32

In 1913, fifty-three charities in

Cleveland organized the Federation for

Charity and Philanthropy, "the

first of the larger existing Federations" in

the United States.33 Its

purpose was to pool all fund raising efforts for cur-

rent expenses into one big drive, the

Community Chest. When a charity

joined the Federation, it agreed not to

solicit funds on its own from Feder-

ation subscribers to meet current

expenses. Furthermore, before soliciting

money for other needs, Federation

charities were expected to get permission

from the Federation board. Thus

belonging to the Federation meant a con-

siderable loss of independence on the

part of the individual charity. Before

formation of the Federation, the boards

of directors for each charity ap-

proved the programs of that charity.

Since the directors were usually the

major contributors, they had a great

deal of control over how their money

was spent under the old system but

little under the Federation. To a char-

ity like Hiram House which had much

success in raising funds the advant-

HIRAM HOUSE 37

ages of the organization were

questionable. Samuel Mather stated the case

against the Federation when he wrote to

George Bellamy in 1910:

I told them [the Federation officials]

frankly that I had been unable

so far to come to a conviction that

things would be better to have all

charitable gifts made in a lump sum to

the committee and distributed

by them to the various charities of the

city. I felt that it would destroy

far too much the interest felt by the

giver in the various charities of the

city, which depended much on the

information and interest he receives

through personal contact with those in

control of the institutions. I

presume it [the Federation] would result

in an economy of time and

money but at the expense it seems to me,

of a vital interest and con-

nection, both to the giver and the

worker.34

An institution, nevertheless, would

appear selfish if it stayed out so Hiram

House relunctantly joined the

Federation. With the exception of John D.

Rockefeller, the early contributors were

actively interested in the settle-

ment and played a more important role in

its work before the Federation

assumed control of the budget. Many had

supported it out of a sense of

generosity and civic duty, and Hiram

House owed its continued existence

to these men.

Only the first twenty years of Hiram

House are discussed here, a time span

chosen because these years appeared to

be the ones in which its work was

most significant as well as

representative of the settlement movement. At the

end of this period, the buildings on the

blocks across the street from the

settlement were demolished to make way

for a railroad. As a result, the

House lost almost one-half of its

neighborhood but remained active in this

location until the 1930's. From then

until 1947, its programs were carried

on in various school buildings. In 1947,

when Bellamy retired, the Federa-

tion voted to discontinue financing the

settlement but to continue its sup-

port of Hiram House Camp, acquired as

part of the settlement in 1903. The

Camp, located near Chagrin Falls, is all

that is left at the present time. The

land on which Hiram House was located is

now covered by a freeway; and

what remained of the old neighborhood

has been leveled, with one or two

exceptions, under the St. Vincent Urban

Renewal Project.

With so few physical reminders of the

past left, the question remains

what, if anything, was significant about

Hiram House. The only unique

contributions made by the House were in

connection with its playground,

but its human contacts were many and

varied. The settlement compensated

for the school board's hesitancy to

provide kindergarten, cooking, and man-

ual training classes. It helped the

immigrant to adjust to a new environ-

ment; it tried to improve that

environment by serving as a force for reform

during the progressive era. The

"neighborhood visitor" was one of the fore-

runners of today's caseworker. In

summary, even though Hiram House was

not a major innovator or leader among

settlements on the national scene,

its significance lies, instead, in the

fact that it participated fully and actively

in most aspects of the early settlement

movement and thereby attempted to

meet the needs of its neighborhood.

THE AUTHOR: Judith A. Trolander is

a doctoral candidate at Case Western

Re-

serve University.

|

Twenty Years at Hiram House by JUDITH A. TROLANDER Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the settlement movement reached the United States. Hull House, the most outstanding and second oldest settlement, was established in Chicago in 1889. The first social set- tlement in Cleveland to actually do settlement work as such was Hiram House, founded in 1896.1 Today, however, Hiram House has been largely forgotten, partly because George Bellamy, the founder and director through- out its existence, published very little. Fortunately, Bellamy was a com- pulsive saver of papers relating to his work. Recently, his widow presented these letters, reports, notes for speeches, and other papers dating back to 1901 to the Western Reserve Historical Society. As a result, it is now pos- sible to present a fuller and more detailed picture of the significance of Hiram House in the early years of the settlement movement. George Bellamy was born on September 29, 1872, in a small town in Michigan. He was a "descendant of the Wolcott [Oliver] who signed the Declaration of Independence and who was Secretary of the Treasury and in the Cabinet of George Washington."2 Unusual for one who worked as extensively with immigrants as he did, Bellamy was proud enough of his "old family" background to become a member of the New England Society of Cleveland and the Western Reserve and also the Society of the Descen- NOTES ON PAGE 69 |

(614) 297-2300