Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

LYSLE E. MEYER

Radical Responses to Capitalism

in Ohio Before 1913

By the time Ohio entered the last two

decades of the nineteenth century, various

forms of radicalism had already emerged

which challenged the basic tenets of the

prevailing style of life. A number of

communitarian settlements had been estab-

lished in the state, beginning with the

first Shaker experiments, Union Village in

1805 and Shakertown in 1806. The

Wurttemberg Separatists, soon after, founded

the Zoar community in 1817. Some of

these settlements represented apocalyptic

sectarian communism with emphasis on

withdrawal from the neighboring world for

the purpose of religious and social

regeneration. As such, they were the outgrowths

of religious movements ultimately

traceable to the Protestant Reformation. All re-

jected individualism as offering no hope

to a troubled world.1 The social and eco-

nomic aspects of the Shaker program, for

instance, included the following considera-

tions:

The great inequality of rights and

privileges which prevails so extensively throughout the

world, is a striking evidence of the

importance of a reformation of some kind . . . .

The United Society of Believers (called

Shakers) was founded upon the principles of

equal rights and privileges, with a

united interest in all things, both spiritual and temporal. . . .2

Not all communitarian experiments were

basically religious movements; some

were clearly secular and designed

primarily for social reform. Perhaps the best

examples of the secular type were those

based upon the theories of the European

utopian socialists Robert Owen and

Charles Fourier. After achieving fame as

founder of the model factory town of New

Lanark in Scotland, Owen, a wealthy,

self-made British industrialist,

established a community in New Harmony, Indiana,

in 1825. Here he hoped to put into

practice his beliefs in the equality of men and

the necessity for community ownership of

goods. It was Owen's view that controlled

environmental improvement was the key to

social progress. Although New Harmony

was unsuccessful, due largely to

inadequate planning and supervision, Owen's

1. Arthur E. Bestor, Jr., Backwoods

Utopias: The Sectarian and Owenite Phases of Communitarian

Socialism in America, 1663-1829 (Philadelphia, 1950), 5-7; Albert T. Mollegen,

"The Religious Basis of

Western Socialism," in Donald Drew

Egbert and Stow Persons, eds., Socialism and American Life

(Princeton, 1952), I, 114.

2. Calvin Green and Seth Y. Wells, A

Summary View of the Millennial Church, or United Society of

Believers, Commonly Called Shakers .

. . (Albany, 1848), 2-3.

Mr. Meyer is chairman, department of

history, Moorhead State College, Moorhead, Minnesota.

194

OHIO HISTORY

dream inspired other similar experiments

in America. Indeed, even before New

Harmony took shape, some other reformers

assembled a community at Yellow

Springs, Greene County, in 1825. Within

a year and a half this effort failed, but

other Owenites had slightly more success

with the Kendal community in Stark

County from 1826 to 1829. And in the

southwestern part of the state during the

same period still other like-minded

communitarians, such as the Rational Brethern

of Oxford and the Swedenborgians, had

their brief flings at creating better worlds

in microcosm.3

Fourier, the French visionary, proposed

a model society which would abolish

evil through a transformation of the

social environment but would use the phalanx

to accomplish the goal. The phalanx was

a social unit within which there would be

communal living, free choice of

occupations, and easy mobility from one occupation

to another but not economic equality.

The phalanxes were to be cooperative associ-

ations in rural settings where annual

profits would be divided in ratio of five-twelfths

to the laborers, four-twelfths to the

investors of capital, and three-twelfths to the

intellectuals or imaginative leaders who

provided the ideas.4 Over forty schemes,

based more or less on the phalanx plan,

were put into operation in the United

States, four of them in Ohio during the

1840's. The Fourierists of Ohio, however,

had no more success than the followers

of Robert Owen.

Although these groups, both religious

and secular, never attracted large num-

bers into their ranks, it would be a

mistake to discount completely their effect on

the attitudes of others. By means of

books and pamphlets many persons received

information about their ideas and

activities. In some cases, such as the Zoar com-

munity, outstanding management and high

quality production units focused atten-

tion on the project, giving the group an

influence on its neighbors out of proportion

to its size.

Other radical currents passed through

Ohio after the Civil War, several of them

lingering on as a result of certain

long-standing conditions. Liberal Republicanism,

the Cheap Freight Railway League, the

Free-Trade League, and Greenbackism

were some of the responses generated in

the Midwest by reformers and specific

interest groups. The Greenback movement,

of particular importance, represented

strong support on the part of farmers

and debtor classes in Ohio for inflationary

measures by the Federal Government.

Eventually, in 1877, these increasing demands

for financial relief were brought to a

head with the formation in Columbus of an

"Independent Greenback Club"

which later became the Greenback party. In addi-

tion to an altered monetary policy, the

Greenbackers called for governmental re-

strictions on all corporations and

demanded Federal programs to insure fuller

employment as well as a graduated income

tax--in short, economic equality for

all segments of the population.5

The foregoing expressions of discontent

were rurally based. During the same

period conditions in the cities also

encouraged unrest and dissatisfaction with the

status quo. The rapid growth after the Civil

War of the principal cities engendered

the explosive political and social

problems which were to arouse ever-increasing

3. Bestor, Backwoods Utopias, 160-201,

205-213; Mark Holloway, Heavens on Earth: Utopian Com-

munities in America, 1680-1880 (New York, 1966), 104-106; Wendall P. Fox, "The

Kendal Community,"

Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Publications, XX (1911), 176-219.

4. Holloway, Utopian Communities, Chapter

8.

5. Chester McArthur Destler,

"Western Radicalism, 1865-1901: Concepts and Origins," Mississippi

Valley Historical Review, XXXI (December 1944), 339-341; Philip D. Jordan, Ohio

Comes of Age, 1873-

1900 (Carl Wittke, ed. The History of the State of Ohio, V,

Columbus, 1943), 154-155.

Responses to Capitalism 195

cries for reform in Cincinnati,

Cleveland, and Columbus toward the end of the

century. As industry progressed and

business expanded, the cities attracted greater

numbers from rural areas and from

overcrowded countries of Europe. The labor

movement gradually became a more

significant element for reform in the larger

urban areas amid wretched working

conditions and oppressive policies of employers.

Working women and children were

especially ill-treated and their situation con-

tinued to demand rectification. Through

the seventies, hardship was rife among

city workers; wage cuts, unsuccessful

strikes, and severe unemployment were the

lot of Ohio's labor.6

Scientific socialism, the doctrine of

Marx and Engels, was an imported ideology

which had come to the United States with

European immigrants. The German

newcomers were the principal supporters

of this type of socialism in the 1850's.

The "forty-eighters," refugees

of revolutions in 1848, established the first socialist

clubs in the United States. After the

Civil War, the German influx continued, and

from 1881 to 1885 Germans represented

the largest single group of annual arrivals

to the United States and to Ohio. In the

census of 1880, Cincinnati showed the

largest German population in the

state--greater, in fact, than that of Cleveland,

Columbus, and Toledo combined.7

The first American socialist

organizations were sections of the Marxist Interna-

tional Working Men's Association and

were set up shortly after the Civil War. By

1872 there were about thirty sections

with five thousand members of the First

International in the United States.

Lassallean socialists, who differed from the Marx-

ists in that they tended to ignore the

labor union movement and concentrate

exclusively on the formation of workers'

political parties, founded the "Social-

Democratic Party of North America"

in 1874. These two antagonistic organizations

existed concurrently until 1876, when

they merged into the new Working Men's

party of the United States. The new

party had a Marxist platform but was directed

by Lassalleans. Conflict continued

between the two wings of the party, and the

Lassalleans won complete control in

1877, changing the name of the group to the

"Socialist Labor Party of North

America."8

The new party concentrated its efforts

on mobilizing the working class to vote. It

was, in fact, the first socialist party

in the United States that was intended for par-

ticipation in national elections. Local

and state elections gave the Socialists some

successes from 1876 to 1878, as the

nation still smarted from the Panic of 1873.

Party membership rose from 3000 to

10,000 in that period. Specific local conditions

also assisted the Socialists. In the

municipal elections in Cincinnati, for instance, the

party won 9000 votes in 1877 as a result

of the serious strikes preceding the elec-

tions, but this artificial boom was soon

over and the vote the next year was a meager

500. This great fluctuation can be

explained partly as the result of Cincinnati Social-

ists' failure to build any ties with the

trade unions in that city. Generally, member-

ship in the party as a whole grew in the

late seventies, but, as some degree of

prosperity returned to the country after

1879, the party rolls shrank, the national

6. Eugene H. Roseboom and Francis P.

Weisenburger, A History of Ohio (Columbus, 1956), 228-229.

7. Ira Kipnis, The American Socialist

Movement, 1897-1912 (New York, 1952), 6-7; Ohio, Annual

Report of the Secretary of State,

1885. p. 888; United States Bureau of

the Census, Immigrants and

Their Children 1920, Census Monographs VII (1927), 395.

8. Kipnis, American Socialist

Movement, 7-10. Ferdinand Lassalle (1825-1864) was the founder of

the German Social Democratic movement.

He emphasized the importance of political action toward

such goals as universal suffrage, but he

eschewed all violence.

196 OHIO

HISTORY

total being about 1500 members in 1880,

of whom only ten percent were native

Americans.9

Organization and expansion of the party

in the 1880's was difficult because inter-

nal party strife increased. Since trade

union forces within the Socialist ranks had

enjoyed no tangible results from limited

election successes, they wanted to give all

their attention to union activity.

Other, more extreme factions, believed that direct

action was necessary; these elements

increasingly joined emerging anarchist groups.

Not surprisingly, the dissension

prevented effective electioneering for socialist pro-

grams, with the result that the party

supported Greenback candidates for the presi-

dency in 1880, evidently hoping to

capitalize on some of that organization's

spectacular success in 1878. The

disastrous failure of the Greenbackers in 1880 as

well as their own internal troubles,

caused the Socialists to abstain from the 1884

election. Even in 1888, although an

independent ticket was put forward, candidates

were run only in New York.10

All through the eighties the Greenback

party campaigned in Ohio and had pro-

labor planks in its platform.11 The

Greenbackers made "Labor" part of their title in

1883 and the Greenback Labor party was

born. Faced with such competition, the

Ohio Socialist Labor party found itself

working with the Greenbackers, supporting

their local candidates while becoming

less active and influential in its own cause.

Socialists might have had a brief local

appeal in connection with particular labor

disputes, such as the serious Hocking

Valley coal strike of 1884, but their popularity

was short-lived.

Among other obstacles to Socialists'

progress at this time was the fact that the

party was composed predominately of

foreigners and had few English-speaking

organizers to work in the state. The

only English-language Socialist paper in Ohio

was moved from Cincinnati to Chicago

after the severe party defeat in 1878 in that

major Ohio city. Also of concern to the

Socialists during the early 1880's was the

challenge from the anarchist ranks. The

increasingly successful appeal of this im-

ported Russian ideology was considered

detrimental to Socialist interests in urban

centers. By 1885 there were some

English-speaking groups in Cleveland and Cin-

cinnati that were affiliated with the

Black International (Mikhail Bakunin's Anarch-

ist International Working People's

Association) as well as an indefinite number of

foreign language units. The competition

between the Socialists and anarchists was

resolved in favor of the Socialists as a

result of the infamous Haymarket Massacre

of 1886, in which a group of anarchists

was accused of throwing a bomb that caused

heavy casualties among a Chicago police

unit. After this bloodshed the Socialist

party was able to increase the number of

its sections in most of the midwestern

states.12

During this same period another response

evoked by the socioeconomic system

was the Single Tax movement conceived by

Henry George (1839-1897). In 1871

the former newspaper man published a

forty-eight page pamphlet Our Land and

Land Policy, which was expanded into a book length presentation, Progress

and

Poverty, in 1879. In these works George advocated the

destruction of land monopoly

9. Ibid.; John R. Commons and others, History of Labor in the

United States (New York, 1918),

II, 282; Daniel Bell, "The

Background and Development of Marxian Socialism in the United States,"

in Egbert and Persons, Socialism, I,

237.

10. Kipnis, American Socialist

Movement, 10-11; George Harmon Knoles, "Populism and Socialism

with Special Reference to the Election

of 1892," Pacific Historical Review, XII (1943), 297-298.

11. Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia . .

. 1881, VI, 701-702.

12. Commons, History of Labor, II,

282, 300, 390.

|

|

|

as a solution to the nation's economic ills. He would accomplish his purpose by shifting all taxes from labor and the products of labor to land. Land was considered to be the essential commodity for taxable purposes since he saw it as the source of all employment. To correct the unequal distribution of wealth as well as cure the abuse of recurring business depression the Single Tax on the value of land, irres- pective of improvement, should be adopted. Such a tax would make "land specu- lation unprofitable, land monopoly impossible, and so open to the possessors of the power to labor the ability of converting it [the ability to work] by exertion into wealth or purchasing power" and thus eliminate the preposterous situation in which "a man able to work suffers from want of things that work produces."13 George's writings were widely distributed, and by 1886 he was asked to run for mayor by the Central Labor Union of New York City. He was nominated, he said, "because it was believed that I best represented the protest against unjust social 13. Henry George, Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth, The Remedy (Cincinnati, 1905), 263-294; Henry George, "Causes of Business Depression," essay by George based on his book Progress and Poverty, reprinted by the Robert Schalkenbach Foundation, New York, 1930, pp. 12-13. |

|

|

|

Tom L. Johnson, c. 1896. conditions [inflicted on the Irish workingmen] and the best means of remedying them." Pitted against him in a hotly contested campaign were Abram S. Hewitt, Democrat, and Theodore Roosevelt, Republican. The official result of the balloting was Hewitt, 90,552; George, 68,110; Roosevelt, 60,435.14 Even though George lost in the election, he gained widespread publicity and many converts to his ideas. One such person was the thirty-one year old business- man Tom L. Johnson, who would become Ohio's Congressman from 1891 to 1895 and be mayor of Cleveland, 1901-1909. In an effort to publicize George's ideas, Johnson in 1892 led a small group of Single Taxers in the House in a project to read into the Congressional Record another of the reformer's books, Protection or Free Trade, as part of their remarks on the tariff question then at issue. The 332 page book was subsequently mailed, without cost, to Single Taxers (more than 1,200,000) under the franking privilege, after printing costs had been paid by those wishing to circulate the information. Also, in Ohio, a Single Tax League was formed which claimed that a total of forty-one towns had Single Tax clubs or committees. It published a paper that carried attacks on tariffs and taxes along with appropriate 14. Arthur Nichols Young, The Single Tax Movement in the United States (Princeton, 1916), 95-107. |

|

|

|

Edward Bellamy, c. 1890. COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS quotes from George, Herbert Spencer, and Thomas Huxley. From an office in Cleve- land the league mailed to members the names of likely prospects for its propaganda barrage and weekly missives were sent to the contacts.15 When Tom Johnson became mayor of Cleveland, he continued his allegiance to George's ideas and the struggle against "Privilege." This he defined as "the ad- vantage conferred on one by law," and identified five major classes of privileges: land monopolies, taxation monopolies, transportation monopolies, municipal monop- olies, and patent monopolies, emphasizing that "the greatest of all governmental favors or special privileges is land monopoly, made possible by the exemption from taxation of land values." Johnson explained carefully what he meant by "land value" in a speech to farmers that was published and widely distributed in pamphlet form by the Joseph Fels Fund of America in 1908. To Johnson the "single-tax" would not be on the amount of land a person owned, which would unjustly penalize farm- ers, but on "land values" or value due to improvements or mineral wealth of all kinds. The burden of taxation would then be lifted from farmers and workingmen 15. Ibid., 142-145; Tom L. Johnson, My Story, edited by Elizabeth J. Hauser (New York, 1915), 52; Single Tax (Cincinnati), March 15, 1890. |

200

OHIO HISTORY

and be placed on those who were

profiting most from the monopolies. Even though

the Single Taxers were not able to pass

direct legislation in the Ohio Assembly,

efforts by Johnson and like-minded

disciples of Henry George helped swell the

ranks of those clamoring for reforms, especially among

the middle class in Ohio.16

Another radical response which caught

the imagination of Ohioans in the late

nineteenth century for improvement of

the economic system was the American-born

socialist movement known as

"Bellamy Nationalism." This was the name given, at

the suggestion of William Dean Howells,

by Edward Bellamy to the utopian system

portrayed in his novel, Looking Backward,

2000-1887. Published in January 1888,

200,000 copies had been sold by December

1889. In place of the laissez faire prac-

tices of the Gilded Age, Bellamy

advocated a paternalistic state that would main-

tain an economy of abundance in which

all citizens, even those infirm and insane,

would share equally. To achieve this

goal he advocated such reforms as municipal

ownership of water, gas, electricity,

and street railways; government ownership of

railroads, telegraph, and telephone;

government regulation and eventual ownership

of all mines; the initiative, the

referendum, and minority representation; and several

other reforms as well.

Bellamy's ideas were initially advanced

through clubs established by his followers.

The first Nationalist club in Ohio was

formed in Cincinnati in 1889, one year after

the first had been established in

Boston. Thereafter clubs were founded by middle-

class elements in Cleveland, Akron,

Columbus, and Findlay, and other groups ex-

isted, such as the Dayton Citizens' Club

and the Cleveland Citizens' Alliance, which

espoused principles related to those of

Nationalism. In 1893 the Nationalists, in

cooperation with the National Farmers'

Alliance, formed a new political party, the

Peoples Party of Ohio or Populist party.

Nationalist influence in Ohio reached its

climax in 1894 when the Labor party

joined in a coalition with the Populist party.

At a convention in Columbus that year

the platform adopted was a composite,

including, in addition to those

Nationalist aims cited above, the following

Nationalist-oriented planks: collective

public ownership of all means of production

and distribution, passage of fair labor

laws, currency reform, and female suffrage;

it also included a vaguely worded

single-tax plank denouncing land monopoly.

After a poor showing at the polls in

1894, the Nationalist movement declined, and

in 1896 the Populist party merged with

the Democratic party, leaving the Nation-

alist faction without coalition support.

The Nationalist clubs thereafter quickly dis-

appeared from Ohio, but it may be

assumed that more than one person found

Socialism via Bellamy Nationalism.17

Following the Panic of 1893, Ohio

experienced a depression. The spirit of unrest

was widespread and strikes were common

throughout the state. Unemployment was

high and no relief was in sight. In 1894

Jacob S. Coxey, an Ohio businessman-

politician, decided to do something

about this situation. He organized a so-called

"industrial army" of the

unemployed and marched to the nation's capital. The

march was to call attention to the

workers' distress and bring to the Government

16. Johnson, My Story, xxxv-xxxvi;

Johnson "Tom Johnson to Farmers," leaflet published by The

Joseph Fels Fund of America, Cincinnati,

n.d., n.p. For a fuller discussion of the work of Single Taxers

in Ohio, see Lloyd Sponholtz,

"The 1912 Constitutional Convention in Ohio: The Call-up and Non-

partisan Selection of Delegates,"

in this issue.

17. This discussion of the Bellamy

movement is based on William F. Zornow's article, "Bellamy

Nationalism in Ohio 1891 to 1896," Ohio

State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, LVIII (April

1949), 152-170; Arthur E. Morgan, Edward

Bellamy (New York, 1944), 248, 276-277; Appletons'Annual

Cyclopaedia, 1894, 627; Ohio State Journal (Columbus), August 8,

16, 18, 1894.

|

|

|

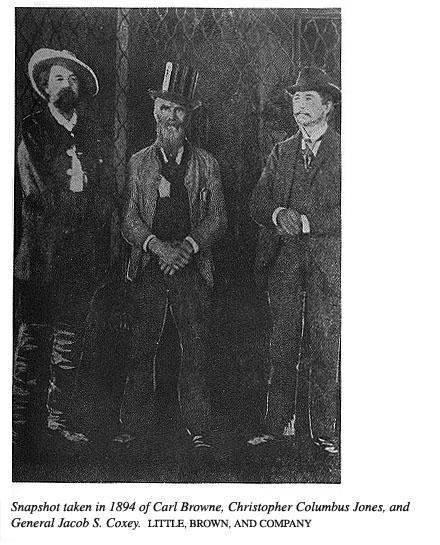

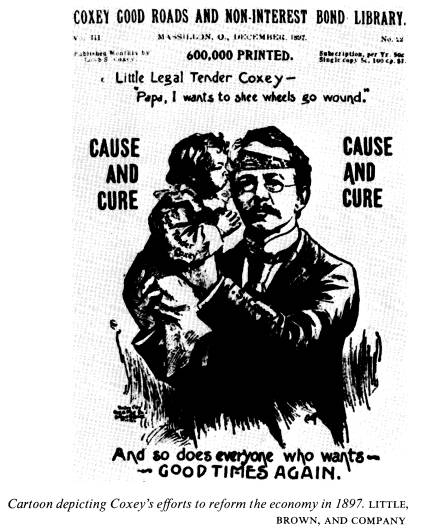

pleas for Federal work projects to relieve the unemployment. Coxey's home town of Massillon, Ohio, was the starting point of the demonstration, but many partici- pants were from Cleveland and Chicago, and workingmen were added to the group along the way. In desperation men joined "The Commonweal of Christ." This was the name adopted by Carl Browne, one of the leaders, who fostered a religious aspect in the movement. One observer noted, nevertheless, that their minds were "unfortunately, fast grounded on socialism." It is likely that many of the discour- aged marchers returned home only to become associated with more radical ele- ments. Coxey, however, turned to the Populists for support and was run for gover- nor in 1895, receiving 50,000 votes. His early radicalism evidently did not leave an indelible mark on him, for in 1932, while mayor of Massillon, Coxey polled 75,000 votes in the Republican presidential preference primary.18 Another movement responding to the economic and social problems in Ohio was Christian socialism. This effort represented the new liberal tendencies in theology, 18. Donald L. McMurry, Coxey's Army: A Study of the Industrial Army Movement of 1894 (Boston, 1929), 32-53; Roseboom and Weisenburger, A History of Ohio, 248. See also Osman C. Hooper, "The Coxey Movement in Ohio," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications, IX (1901), 155-176. |

|

|

|

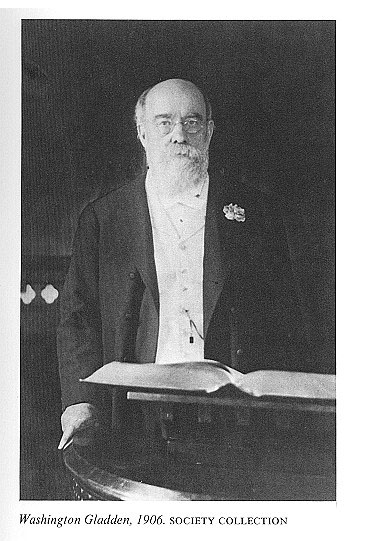

the basic concern for social justice, the influence of political economists, as well as the response to charges made against religion by Socialists, labor leaders, and others. Organized Christianity was said to be unconcerned with the many social ills bred by the industrial revolution in America. Leaders of the Social Gospel took up this challenge and tried to stem the tide of individualism which long had dominated Christian thinking. These leaders placed emphasis on the salvation of society in addition to that of individuals.19 Among the foremost exponents of the Social Gospel was Washington Gladden, pastor in Columbus from 1882 until his death in 1918. An indefatigable leader in the movement to keep Christianity a dynamic force in a changing industrial society, he took the offensive and questioned the premises of the Socialists and other re- formers. He attempted to show that the great problem of society was the proper relationship of man to his fellow-man; that man's relation to persons is deeper and diviner than his relation to things. Gladden appreciated the plight of the common man and did much to organize charity for relief of the suffering. The capitalist class 19. James Dombrowski, The Early Days of Christian Socialism in America (New York, 1936), 3-13. |

|

|

|

was told to recognize the good sense in helping labor to become prosperous so that everyone would benefit, and the urban dwellers were told that responsibility for good city government was theirs--they could not expect to receive benefits while they ignored their obligations. Gladden probably went further than most of his colleagues in his tolerant attitude toward Socialism; he held that "It is not wise to denounce Socialism and Socialists hotly and by wholesale, as so many do; it is much better to try to understand what they have to say and to discern the truth which is mingled with what we may admit to be their errors and exaggerations."20 Churchmen of many denominations participated in the Christian socialist move- ment in one degree or another, speaking out for reform or giving direct comfort to the unfortunate groups in society. During the 1890's an increasing number of theo- logical seminaries conducted special lecture courses on the relationship of the church to social problems. One such conference in 1894 on the subject, "Causes and Pro- posed Remedies for Poverty," was held at Oberlin College, sponsored by the Ameri- can Institute of Christian Sociology. This seminar was exceptional in that Socialist 20. Washington Gladden, Christianity and Socialism (New York, 1905), 51-53, 140, 230-231, 241-244. Gladden was well regarded in some Socialist papers; see The Socialist (Columbus), January 21, 1911. |

204

OHIO HISTORY

Thomas J. Morgan,

labor leader Samuel Gompers, and Rev. Washington Gladden

were asked to be

speakers stating their own cases. Professor John R. Commons,

the institute's

secretary, was on the faculty of Oberlin and was partly responsible

for that institution's

leadership in the teaching of social Christianity.21

In the period

1899-1914, Ohio rose from eighth to third in the nation in the in-

crease of number of

wage earners.22 This factor, when taken into consideration with

other conditions

previously mentioned, helps to account for the growth of the Social-

ist party during this

period. Ohio ranked third nationally in total Socialist vote in

1904 and was first by

1910. Lucas and Montgomery counties began to return rela-

tively more Socialist

votes by 1900, ahead of the Prohibition party, with both coun-

ties surpassing the

Franklin County Socialist vote that year. Candidates for president

that year were William

McKinley, William Jennings Bryan, and Eugene V. Debs.23

Indicative of growing

Socialist influence was the expansion of the Socialist press.

Not only did

additional newspapers appear but there was also a concerted attempt

to coordinate the

journalistic efforts of foreign-speaking and English-speaking sec-

tions of the party.

This question of coordination, of course, was part of the larger

problem of over-all

cooperation and consistency between language groups in the

movement. It was estimated

at one time that many foreign language sections of

the Socialist party in

Cleveland were practically isolated from the main units; they

were so much in

ignorance and behind the times that some of them still circulated

literature against

feudalistic institutions and called for separation of Church and

State.24

Socialist party

sections were organized throughout Ohio during the first decade

of the twentieth

century. Some of these groups in small hamlets such as Rawson,

Roseville, Aurora, and

Alpha had only half a dozen members, but all contributed

to the movement. Nor

was membership a simple automatic procedure. An applica-

tion had to be filed;

the applicant had to endorse without qualification the prin-

ciples of Socialism;

he had to be supported by a party member; and the prospective

member was then

examined by a committee. The party was specific in expressing

its determination not

to accept for membership anyone who was an "old ward-

heeler type." It

was claimed that such elements "could not break into the Socialist

party with an

ax." An incomplete breakdown of the delegates who made up the

1910 Ohio state

convention of the Socialist party showed the following backgrounds

represented:

Capitalists and small

businessmen 8

Professional men 11

Wage workers 115

Farmers 11

Also noteworthy was

the fact that 113 representatives were native born and only

seventeen foreign

born, giving clear indication of the success of the party's "Ameri-

canization"

process.25

In the drive to make

Socialism appeal to native-born Ohioans, the party organized

21. Dombrowski, Christian

Socialism, 72.

22. United States

Bureau of the Census, The Growth of Manufactures 1899-1923, Census

Monographs

VIII (1928), 84.

23. Socialist, April

13, 1912; Ohio, Annual Report of the Secretary of State, 1900, pp.

188-189.

24. Socialist Party, Proceedings

of the National Convention . . . Indianapolis, Indiana, May 12-18,

1912 (Chicago, 1912), 86.

25. Socialist, February 10, 17, March 2, 1912. Forty-nine of the workers

were labor union members.

Responses to Capitalism

205

programs similar to those sponsored by

many middle-class organizations. In Colum-

bus there was a Socialist Dramatic Club,

a Glee Club, and a Young People's Social-

ist League. Annual outings held in

Olentangy Park attracted as many as 20,000

Socialists, their families and friends

from all over the state. They were urged to

come and see the balloon ascensions and,

by congregating in large numbers, also

to "strike terror to [the] hearts

of plutes." In Mansfield, the party members occu-

pied themselves with the distribution of

leaflets and campaign literature, the mail-

ing of a party paper, the maintenance of

a Socialist library, and the arrangements

for lectures and speeches.26 These

activities probably represented the largest share

of the work done by the general

membership in the state. Thus it seems that be-

cause of the need to appeal to the

predominately bourgeois values of the American

working class, a type of "respectable"

radicalism was evolving which could attract

a wider following than could the parties

of the 1880's which were commonly asso-

ciated with the lunatic fringe.

Lectures were regular affairs in major

Ohio Socialist centers. In Columbus the

"Chicago Daily Socialist Lyceum

Course and Lectures" were offered. These com-

prised a series of evening talks and

discussions which were crowned on the final

night with a concert by the Socialist

Quartette Concert Company. Speakers were

invited to tour the state, and such

figures as Big Bill Haywood, Ella Reeve Bloor,

Eugene Debs, and Victor Berger made

appearances at various times and places in

Ohio. When the first-mentioned speaker

arrived he was heralded by the following

notices in the Columbus Socialist:

Come and Hear the Radical Speaker

of the Industrial Fight. He Talks

Common, Everyday, United States

Language.

If you are Timid or Middle Class,

you had Best Beware for He will Jar You.27

Haywood, the indefatigable organizer of

the Industrial Workers of the World,

evidently was a great drawing card,

providing a vicarious thrill to those who liked

to hear someone utter radical phrases

they could not bring themselves to express

in public.

The colleges and universities in the

state were not neglected. Socialist speakers

addressed the students at Ohio State

University on several occassions. In 1911,

"Comrade" Frank Bohn, as

associate editor of the International Socialist Review,

spoke in the university chapel under the

auspices of the school's Socialist Club.

Another Socialist spoke to "a

goodly number" on the Columbus campus and

described how the American workingman

was being exploited by the "money

power." Also, an Intercollegiate

Socialist Society, composed of representatives from

many schools across the country, had

clubs at Ohio Northern and Ohio Wesleyan.28

The Socialist party press broadcast

official views, continually disseminated propa-

ganda, and spoke out on local issues.

Taking the Columbus Socialist as an example

of expressed opinion, one can ascertain

how the party stood on important questions

of the time. Organized charity was

termed a "fake"; the workers, it was said, wanted

justice not charity. The contract system

for prison labor was a major object of

26. Ibid., May 27, 1911; February

17, 1912.

27. Ibid., January 14, 1911;

April 6, 1912.

28. Ohio State Lantern, October

11, 1911; Socialist, April 6, March 16, 1912.

|

|

|

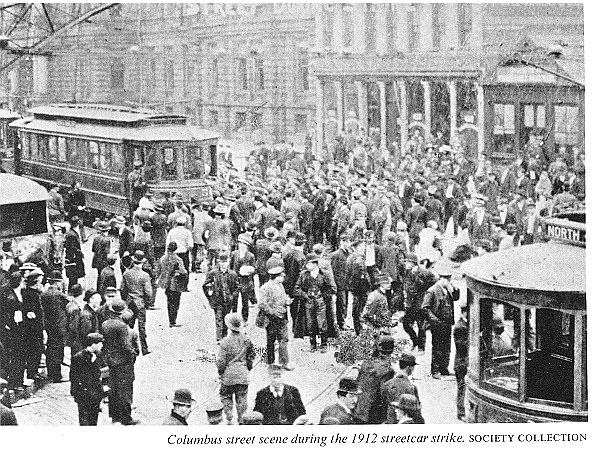

Socialist ire in this period and was termed an abusive practice by which the state made millionaires. Southern anti-Negro legislation was attacked by Socialists, as were matters such as poor slaughtering inspection and bad streetcar service. Party support was voiced for the eight-hour day for women. Daily fare in a Socialist paper, of course, was a diatribe against the capitalists and monopolists in general, or certain employers and "slave drivers" in particular. Then, too, the capitalist press was usually taken to task for its poor coverage of Socialist activities.29 All this effort paid dividends, for some startling results were achieved by the Socialist party in 1910. In the race for governor with Judson Harmon and Warren G. Harding the leading Democratic and Republican contenders, the Ohio Socialists doubled their vote of 1908 and became the major Socialist state in the nation with 62,356 votes, followed by Pennsylvania with 59,630, Illinois with 49,896, and New York with 48,982. In 1911 Socialists were elected to city council posts in Columbus and to mayoralties in St. Marys, Salem, Cuyahoga Falls, Barberton, Lorian, Martins Ferry, Canton, Mt. Vernon, Fostoria, Toronto (Jefferson County), and Lima. In 1910 Columbus registered a Socialist vote more than twelve times that of 1908 and larger than that of Cleveland and Cincinnati combined. The victory in Columbus in 1911 was due to several factors. There had been serious labor disturbances in the city during 1909 and 1910. The most important was the streetcar strike during the latter year which occupied center stage for three months. The transit authority (Columbus Railway and Light Company) refused to recognize the employees' union and discharged some of its members for reasons interpreted by the union as retalia- tory. When initial attempts at arbitration threatened to break down, Republican 29. Ibid., March 4, February 18, 1911; December 24, 31, 1910. |

Responses to Capitalism

207

Governor Harmon readied the militia in

anticipation of trouble. Troops eventually

camped in several parts of the city,

despite the mayor's assurances that he could

control the situation without

soldiers.30

In typical fashion for the time,

strike-breakers were imported by the company,

and before the regular car operators

walked out they were ordered to teach these

"scabs" their jobs. Union men

protested that they had to train workmen who

"cursed unionism and bragged of

successful strikebreaking" elsewhere. Even the

police were shocked at the apparent

injustice of the company's stand, and about

fifty of their number mutinied, refusing

to obey commands to guard streetcars.

Columbus was exposed to numerous

incidents of violence during this bitter con-

frontation as cars and carbarns were

dynamited and troops, deputies, and detectives

clashed with strikers. Organized labor

further was enraged by a judicial order halt-

ing picketing and the distribution of

union leaflets against the company. Eventually

the workers gave in but enjoyed no

concessions from their employers. Many men

were not rehired. It seemed that all

authority was against the working class. The

Governor, the courts, the Chamber of

Commerce--all were held to be in collusion

with capitalist management. A Socialist

candidate for Congress suggested that the

people could expect nothing else; the

company owned the line and could control

it any way it saw fit. The only

solution, he declared, was public ownership. The

strike understandably was the prominent

issue with the blue-collar groups of cen-

tral Ohio by election time.31

Also significant in explaining Socialist

gains is the fact that Columbus won spe-

cial attention from party organizers.

Hoping to exploit a favorable situation, Emil

Ruthenberg, the state leader of the

Socialist party, brought Ella Reeve Bloor, a

highly dedicated and experienced

Socialist, to Columbus for an all-out organizing

campaign in Ohio. Much work was done in

the capital itself, as the party claimed

that thirteen branches held weekly

meetings before the election. Mrs. Bloor's efforts

in other parts of the state seem to have

been crowned with some success, but none

more than in her Columbus headquarters.32

Eventually new troubles for Socialism

loomed on the horizon. Ohio's fourth

constitutional convention in 1912 paved

the way for important reforms in the

state, many of which had been championed

by Socialists. A Democratic adminis-

tration led by Governor James M. Cox

took over the reins of government in 1912

and proceeded to enact some of these

reforms into law. It was a new era in con-

structive legislation. Labor benefited

by laws regulating child labor, restricting cate-

gories of work demanding more than an

eight hour day and setting up precautions

against occupational hazards. These and

other reforms understandably took some

of the wind out of the Socialists'

sails. The Ohio Socialist party continued to have

successes in 1912, but its 90,144 out of

a total of 1,037,094 votes that year marked

the peak. In 1913 the Socialist party

began to lose ground nationally, and in the

following year the Ohio unit had only

51,000 supporters at the polls. The "golden

age" of American Socialism was at

an end.33

External factors, such as the general

progressive movement, the brief rise of

Theodore Roosevelt's Progressive party,

and the appeal of President Wilson and

30. Ibid., November 11, 1911;

April 13, 1912; Ohio, Annual Report of the Secretary of State, 1910,

pp. 268, 290, 311; Ohio State

Journal, June 21, June 29, July 3, July 4, 1910; see also, Ella

Reeve Bloor,

We Are Many (New York, 1940), 95.

31. Ohio State Journal, July 30,

August 14, 30, 1910.

32. Ibid., September 16, 1910;

Bloor, We Are Many, 96.

208

OHIO HISTORY

his policies, while certainly

contributing markedly to the decline of socialist strength,

nevertheless do not in themselves

sufficiently explain this phenomenon. Party fac-

tionalism had become extremely

disruptive and must further account for the Social-

ist party's changing fortunes. A key

party convention took place in 1912 at which

a major split occurred. Elements opposed

to violence passed a resolution outlawing

acts of sabotage as a means for

achieving Socialist ends. This resolution was aimed

directly at the syndicalists in the

movement. The pacifist element then proceeded

to force the leading syndicalist, Bill

Haywood, to resign from the national executive

committee. This resulted in the latter

deserting the party along with many left wing

sympathizers. Such a purge, however, did

not end factionalism. The non-syndicalist

radicals who remained in the

organization, though opposed to violence, were none-

theless political actionists who

continued to fight the gradualism of the more con-

servative group then controlling the

party. These currents clearly were felt in Ohio,

where the state organization took the

initiative in striking out at the national leader-

ship. Bitter divisions bred in these

circumstances were not to be easily nor quickly

healed.34

In review it can be seen that radicalism

in Ohio in its various forms was not a

dominant force in Ohio history during

the period discussed here, but it had a

definite influence on the ultimate

course of events. As a response to the shortcom-

ings of the prevailing capitalistic

system, its many-headed presence helped make

people more aware of the need for

economic and social reform, even though the

system itself was modified only

slightly.

33. Ohio, Annual Report of the

Secretary of State, 1914, pp. 259-261. For an account of the reform

legislation enacted 1912-1917, see John

D. Buenker, "Cleveland's New Stock Lawmakers and Progres-

sive Reform, Ohio History, LXXVIII

(Spring 1969), 116-137.

34. Bell, "Marxian Socialism,"

I, 292; David A. Shannon, Socialist Party of America: A History

(New York, 1955), 76-80. See also

Kipnis, American Socialist Movement, Chapter 18, for a somewhat

different interpretation of these

events. There was great dissension within Socialist ranks over the posi-

tion to be taken on the European war,

and when the United States entered the conflict, Socialists were

often persecuted for their opposition to

the war and America's part in it. See Richard A. Folk, "Social-

ist Party of Ohio--War and Free

Speech," Ohio History, LXXVIII (Spring 1969), 104-115.

LYSLE E. MEYER

Radical Responses to Capitalism

in Ohio Before 1913

By the time Ohio entered the last two

decades of the nineteenth century, various

forms of radicalism had already emerged

which challenged the basic tenets of the

prevailing style of life. A number of

communitarian settlements had been estab-

lished in the state, beginning with the

first Shaker experiments, Union Village in

1805 and Shakertown in 1806. The

Wurttemberg Separatists, soon after, founded

the Zoar community in 1817. Some of

these settlements represented apocalyptic

sectarian communism with emphasis on

withdrawal from the neighboring world for

the purpose of religious and social

regeneration. As such, they were the outgrowths

of religious movements ultimately

traceable to the Protestant Reformation. All re-

jected individualism as offering no hope

to a troubled world.1 The social and eco-

nomic aspects of the Shaker program, for

instance, included the following considera-

tions:

The great inequality of rights and

privileges which prevails so extensively throughout the

world, is a striking evidence of the

importance of a reformation of some kind . . . .

The United Society of Believers (called

Shakers) was founded upon the principles of

equal rights and privileges, with a

united interest in all things, both spiritual and temporal. . . .2

Not all communitarian experiments were

basically religious movements; some

were clearly secular and designed

primarily for social reform. Perhaps the best

examples of the secular type were those

based upon the theories of the European

utopian socialists Robert Owen and

Charles Fourier. After achieving fame as

founder of the model factory town of New

Lanark in Scotland, Owen, a wealthy,

self-made British industrialist,

established a community in New Harmony, Indiana,

in 1825. Here he hoped to put into

practice his beliefs in the equality of men and

the necessity for community ownership of

goods. It was Owen's view that controlled

environmental improvement was the key to

social progress. Although New Harmony

was unsuccessful, due largely to

inadequate planning and supervision, Owen's

1. Arthur E. Bestor, Jr., Backwoods

Utopias: The Sectarian and Owenite Phases of Communitarian

Socialism in America, 1663-1829 (Philadelphia, 1950), 5-7; Albert T. Mollegen,

"The Religious Basis of

Western Socialism," in Donald Drew

Egbert and Stow Persons, eds., Socialism and American Life

(Princeton, 1952), I, 114.

2. Calvin Green and Seth Y. Wells, A

Summary View of the Millennial Church, or United Society of

Believers, Commonly Called Shakers .

. . (Albany, 1848), 2-3.

Mr. Meyer is chairman, department of

history, Moorhead State College, Moorhead, Minnesota.

(614) 297-2300