Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

TOM D. CROUCH

Thomas Kirkby:

Pioneer Aeronaut in Ohio

The decade of the 1830's marked the dawn

of American aeronautical history.

Although the first American balloon

ascent had been made on June 24, 1784, when

Edward Warren, a thirteen year old

Baltimore lad made a captive flight in a home-

made balloon, the citizens of the young

republic remained aloof from so impracti-

cal an enterprise as free ballooning.1

The American tour of Jean Pierre Blanchard

in 1793 demonstrated that even a highly

successful European aeronaut, the first

man to fly the English Channel, could

rarely draw a large enough crowd of paying

spectators to meet his expenses. While

the flights of Louis-Charles Guille in 1819

and Eugene Robertson in 1825 attracted

wide attention, balloon ascents remained

infrequent and were confined to the

large cities of the East Coast.2

The return of Charles Ferson Durant to

the United States in 1830 heralded a

"golden age" of American

aerostation. Having studied in Europe with Eugene

Robertson, Durant was to become the

nation's first professional aeronaut. His

ascents were well publicized and

attended. Durant's first American flight, at Castle

Garden, New York, was followed by a

national tour which proved that an aero-

naut could profitably devote full time

to ballooning. George Elliot, Samuel Wal-

lace, Hugh Parker, Nicholas Ash, and

others followed his lead in introducing the

wonders of manned flight to the people

of New York, Baltimore, and Charleston.

Despite the fact that no ascents had

been made in the state, Ohioans had taken

an early interest in aeronautics. As

early as 1815 a Mr. Gaston had announced to

the citizens of Cincinnati that he would

release a large free balloon prior to a fire-

works demonstration.3 Cincinnati

newspapers carried front page accounts of major

European and American ascents, placing

particular emphasis on such sensational

events as the death of Madame Blanchard

in 1819.4 The "aerial steam-boat" con-

1. Jeremiah Milbank, Jr., The First

Century of Flight in America: An Introductory Survey (Princeton,

1943). Milbank offers a fine

introduction to nineteenth century ballooning.

2. Ibid., 35. Milbank reports that Louis-Charles Guille brought a

balloon to Cincinnati in 1819.

However, a check of the city's

newspapers for the period failed to disclose any mention of his presence.

In view of the fact that the Cincinnati

papers regularly printed accounts of Guille's eastern ascents, it

seems improbable that they would have

ignored a flight in their own city.

3. Cincinnati Liberty Hall, May

15, 1815. Gaston's Fourth of July exhibitions were a yearly tra-

dition in Cincinnati. The balloon

portion of the program was evidently designed to attract crowds for

the more important pyrotechnic display.

Although Gaston's aerostat was large enough to carry a man,

no manned flights were attempted.

4. Mme. Madeline-Sophie Blanchard, wife

of aeronaut Jean Blanchard died when her balloon

caught fire during a fireworks

exhibition in Paris.

Mr. Crouch is supervisor of education at

the Ohio Historical Society.

Thomas Kirkby 57

structed by a Mr. A. Mason of Cincinnati

is further evidence of the interest which

Ohioans took in flight. Mason's flying

machine consisted of a standard small boat

hull, about ten feet in length, covered

with silk rather than wood to reduce the

weight. A two-horsepower steam engine

turned four "wings" which were placed on

rotating shafts. Similar

"wings" were positioned at the rear of the craft to provide

forward motion. The "ingenious

mechanic" exhibited his invention at the Com-

mercial Exchange in August 1834 and drew

much favorable comment from the

local press. Although Mason expected his

machine to "ascend beyond the surface

of this earth to an altitude of, say, 100

feet," the outcome of the experiments was

not recorded.5

Little is known of the background of

Thomas Kirkby, Ohio's first successful

aeronaut. He is reported to have come to

Cincinnati from Baltimore, so we may

assume that he had witnessed the flights

of Durant or other members of the "Bal-

timore school." It is quite

possible that Kirkby had purchased his balloon and

received some instruction in its

operation prior to his appearance in Cincinnati in

the late summer or early fall of 1834.6

Upon his arrival he immediately began to

prepare for his first ascent by ordering

the construction of a large amphitheater

capable of seating 4000 to 5000 persons.

The admission charge of fifty cents would

permit the spectator to observe the

inflation of the balloon, witness the release of

small trial balloons to test the

direction and velocity of the wind, and enjoy the

fine "Band of Music" provided

by Kirkby for the "entertainment of the specta-

tors."7 Preparations

were complete by November 20, and the aeronaut announced

his intention of taking to the air on

the 27th. The gates were to open at noon and

the ascent was to take place at 3:00

P.M.

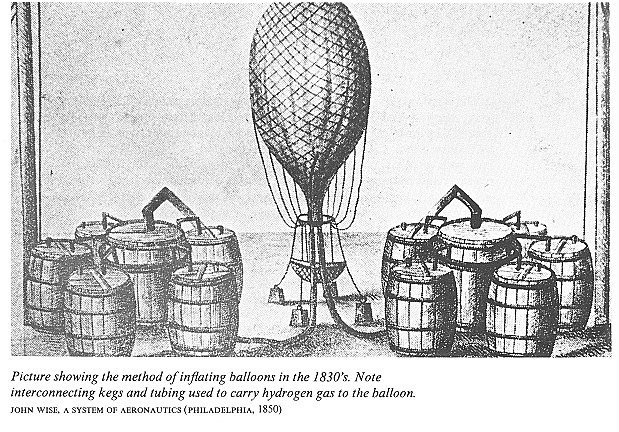

By noon on the appointed day the

apparatus used to inflate the balloon was in

place. A number of casks, connected by

leather pipes, surrounded the two uprights

which supported the limp envelope.

Another pipe ran from the casks to the neck

of the balloon. Each of the casks was

filled about half full with soft iron scraps

to which water was added until they were

two-thirds full. If all went well, a quan-

tity of sulphuric acid, usually about

one-tenth the volume of the water, would be

slowly introduced into each. The casks

were then tightly sealed, and the resulting

hydrogen gas was carried to the balloon

through the system of pipes. As gas gen-

erators became more sophisticated,

washers and dryers. were added to cool and

purify the gas, but Kirkby's use of such

refinements is doubtful.8

The balloon had a 10,000 cubic foot capacity,

which meant that two and one-

half hours time would be required to

fully inflate it. As afternoon passed into eve-

ning, however, it became apparent that

the balloon was not filling properly. By

dusk Kirkby, forced to admit defeat,

distributed "checks" which would admit the

bearer to a second attempt. The problem

lay in the generating apparatus, not the

balloon. Laboring through the night, he

attempted to seal the casks so that the

precious gas would not leak out of the

pipes.

5. Liberty Hall and Cincinnati

Gazette, June 26, 1834; Cincinnati Chronicle

and Literary Gazette,

October 25, 1834; Daily Cincinnati

Republican and Commercial Register, August 23, 1834; October 22,

1834.

6. Commercial Register, November 27, 1834.

7. Ibid., November 20, 1834.

8. Milbank, First Century of Flight, photo

facing page 55; "Field Hydrogen Generation: Vitriol

Process," Balloon Bulletin No. 17,

Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps, United States Army, May 21,

1917.

58

OHIO HISTORY

On the morning of November 28, Kirkby

offered a public apology and prom-

ised that a second attempt would be made

at two o'clock that afternoon, ". . . at

which time the public may rest assured

it [the ascension] will positively take

place."9 That afternoon,

as those who had paid the day before filed into the amphi-

theater, a crowd began to gather outside

where they could have a fine view of the

proceedings once the balloon was

launched. When it became apparent that the gas

generator was still not functioning as

it should, Kirkby again distributed checks

to the paid audience and promised a

successful ascent in a few days. The crowd

outside was unwilling to allow a second

failure to pass so lightly, however. Some

had been standing in the cold since noon

without benefit of the band music inside.

Realizing that the aeronaut was about to

give up for a second time, they refused

to allow anyone to leave the amphitheater.

Although the crowd was inspired by a

"determination to level every thing

connected with it [the balloon]," Kirkby was

able to convince them of the folly of

mob action, and they dispersed.10

The next morning the mob collected

outside the amphitheater again, threaten-

ing to destroy the balloon and the

apparatus. The timely arrival of Mayor Samuel

W. Davies and a squad of nineteen

officers saved the aeronaut and his equipment

from a fate not uncommon for nineteenth

century balloonists. Mayor Davies

assured the crowd that an ascent would

take place and that on the occasion either

he or John J. Wright, a prominent

auctioneer, would take a place in the car with

Kirkby. The mob, feeling that this

demonstration of faith was sufficient guarantee,

broke up. Nevertheless, the nineteen men

stood guard all that night.11

On November 29, in a considerably less

confident tone, Kirkby placed the fol-

lowing announcement in the Cincinnati

papers:

Thomas Kirkby exceedingly regrets that

the apparatus which he had prepared for the

inflation of his Balloon was

insufficient. He regrets the disappointment of the citizens,

and pledges himself that no exertions on

his part shall be wanting to furnish the respecta-

ble audience who waited on him on

Thursday last, with an ascent in a few days, such as

has never been witnessed West of the

Mountains.

He returns thanks to the Mayor of the

city, the Police officers, and the numerous Gen-

tlemen who so kindly assisted him on the

occasion, and solicits the indulgence of the citi-

zens of Cincinnati and the vicinity, for

a few days, to give him time to prepare for a

second attempt, which he trusts will be

successful.12

A week later the aeronaut

"respectfully informed" the citizens that the fault

had indeed been in the generator and that

the ascent would take place in the

middle of the coming week. Kirkby had

solicited the aid of a number of "scientific

gentlemen," including Drs. Slack,

Flagg, and Riddle of the medical college.13 With

their help, he built an entirely new

generator and announced December 15 as the

date of the next attempt. A cannon was

to be fired on the half-hour from nine

o'clock to three o'clock on the day of

the ascent. Every precaution was taken to

9. Commercial Register, November 28, 1934.

10. Rebekah Gest to Erasmus Gest,

December 4, 1834. Erasmus Gest Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

11. Ibid.

12. Commercial Register, November

29, 1834; Cincinnati Gazette, December 4, 1834.

13. Kirkby is undoubtedly referring to

the Reverend Elijah Slack, Professor of Chemistry and

Pharmacy, and Melzer Flagg, M.D. The

identity of Dr. Riddle is not clear. John L. Riddell, the

botanist, was in Cincinnati during this

period, however, and, as a man of universal interests, would

certainly have been attracted to Kirkby's

project.

|

avoid a repetition of the fiasco of November 28. The public was assured that "city officials will be present to preserve order." To avoid confusion, persons holding "checks" were to redeem them at the office of Esq. Harrison before coming to the amphitheater.14 By three o'clock on the afternoon of December 15, "the largest [crowd] that we have ever seen collected in this city," had gathered to witness the spectacle. It seemed for a time that Kirkby would again disappoint the spectators, for the bal- loon was still far from fully inflated when the scheduled ascent was to take place. The crowd became restless and began to "talk about using the poor man up, because he was unable to peril his life for their entertainment." A small striped balloon was released to quiet the mob, but it soon became apparent that if the ascent were not made shortly, real trouble might ensue. Fortunately, it was not long before Kirkby's balloon began to swell. The aero- naut climbed into the car and called for the restraining lines to be released. To the amazement of the audience, and, quite possibly to the performer himself, the balloon rose slowly out of the amphitheater. The editor of the Cincinnati Chroni- cle and Literary Gazette described the reactions of the crowd: "'Drizzle me if he an't off,' muttered a disappointed rioter who thought he had not been fairly used inasmuch as he came there on purpose to have a row--'Well,' said a grey-headed son of the soil at our elbow, 'I've seed a mighty chance o' things in my day, but nothin quite so pokerish curus as that.'"15 Rising steadily now, Kirkby waved the Stars and Stripes and accepted the shouts of encouragement offered by the crowd below. The balloon resembled a "brilliant star" shining in the late afternoon sun as it disappeared to the east. 14. Commercial Register, December 11, 1834; Cincinnati Gazette, December 18, 1834. 15. Literary Gazette, December 20, 1834. |

60 OHIO

HISTORY

The wind, which was blowing from the

southwest at takeoff had shifted to the

west, carrying Kirkby over the bend in

the Ohio River. Approaching Columbia,

east of Cincinnati, he had already

reached his maximum altitude of two and one-

half miles. From this height, the

village appeared as "a confused mass of build-

ings with no discernable outline."

In order to fight the cold, Kirkby put on his

overcoat and resorted to "a draft

of generous cordial which I had in the car as a

companion." Again the wind shifted,

carrying the balloon over Cincinnati a sec-

ond time, giving the aeronaut a fine

view of the Queen City:

It was indescribably beautiful. The

regularity of its plat, the bright light cast upon it by

the setting sun, covering the roofs with

apparently a tissue of silver, contrasted with the

black lines which marked the streets

running north and south and the sombre shades of

those laid out east and west--the

landscape of the country surrounding it, drawn out in

miniature, dotted by the cheerful hand

of industry with innumerable farms;--the beautiful

Ohio appearing like a silver cord

carelessly thrown upon the picture.

In spite of this graphic description of

the sights, Kirkby was in no position to

enjoy the scenery. Although the balloon

was no longer rising, it was spinning "in

a constant whirl" and the aeronaut

became airsick. Also, as he passed between

Milford and Batavia, it began to lose

altitude rapidly. Realizing that the flight

could not continue much longer, Kirkby

prepared to descend in Clermont County.

As he approached a large swamp three

miles from Williamsburg, he brought his

epic voyage to a successful conclusion

in the top of a tree on the farm of one

Samuel Riley. The farmer and a number of

his neighbors arrived soon after and

were able to extricate the balloonist

and his equipment from the branches. The

flight had covered a distance of about

thirty-one miles in slightly less than

an hour.16

In the wake of this successful ascent

Kirkby was referred to as a man of science

and his voyage described as a

"beautiful and sublime spectacle."17 He was, how-

ever, in financial trouble. The expense

of the balloon and equipment, the construc-

tion of the amphitheater, and the acid

and iron scraps, as well as the necessity of

readmitting those disappointed by the

abortive attempts and the cost of an entirely

new generator had taken what small

profit he might have expected. Now several

hundred dollars in debt, Kirkby welcomed

the opportunity to recoup his losses

with a second ascent.18

He announced that, weather permitting,

the next flight would be made on

Christmas Day, 1834. As on the previous

occasion, a cannon would be fired at

half-hour intervals to inform the public

that the ascent would take place. It was

hoped that the balloon would develop

sufficient lift to permit Dr. Riddle to accom-

pany Kirkby so he could conduct

scientific tests in the upper atmosphere.19 Unfor-

tunately, the sky was overcast on the

25th and 26th, but the 27th dawned cold

and clear. The extreme cold kept

attendance to a minimum, and preparations for

the ascent proceeded without incident.

Dr. Riddle was disappointed, however, for

in spite of the trouble-free inflation,

the balloon refused to leave the ground with

16. Commercial Register, December

18, 1834. This article contains Kirkby's personal account of the

first flight.

17. Cincinnati Gazette, December

18, 1834.

18. Ibid., January 1, 1835.

19. Commercial Register, December

23, 24, 25, 1834.

20. Ibid., December 29, 1834.

Thomas Kirkby 61

both men aboard. Kirkby then decided to

go alone. Free of the restraining lines,

the aerostat made a rapid vertical

ascent, describing a half-circle over the city at

an altitude of three-quarters of a mile

before disappearing behind a range of hills

to the east. Kirkby remained in view for

thirty-seven minutes. He brought the bal-

loon to rest in a soft, plowed field two

miles from Milford after a flight of thirteen

miles.20

Although he had now completed two

successful flights, the aeronaut remained

"poorly remunerated for his

trouble, expense and risk."21 His second Cincinnati

ascent was also his last in the state.

While he is reported to have made a flight in

Louisville on March 7, 1835, no further

mention of him is to be found in Cincin-

nati newspapers.22

The achievements of Thomas Kirkby were

soon overshadowed by the spectacu-

lar flight of Richard Clayton from

Cincinnati to Monroe County, Virginia, in

April 1835.23 Compared with this flight,

which set a world distance record for free

balloons, Kirkby's ascents seemed

insignificant and his pioneering efforts were

soon forgotten.

21. Ibid.

22. Literary Gazette, March 7,

1835.

23. Maurer Maurer, "Richard Clayton--Aeronaut,"

Bulletin, Historical and Philosophical Society

of Ohio, XIII (1955), 142-150.

* When Kirkby took coach from the earth to the sky,

And gavefolks a sample of how he

could fly,

Some thought he ne'er meant it, t'was

nought but a joke,

And that on us a hoax he was meaning

to poke;

I doubted myself, but determined to

see,

So to have a good view I climbed up

in a tree.

But Kirkby ascended, and grand was

his flight,

And great was the wonder we felt at

the sight;

Like an eagle he soared on his

heavenly track,

But the next point of wonder was how

he'd come back;

I came down from the tree, and I

looked all about,

To find some sage who could clear up

this doubt.

I saw a great man who, to judge from

its size,

His head must holdplenty of brains to

be wise;

I asked him the question, which he

answered quite bluff

"Why he'll let out the gas, when

he's gone far enough."

"Och no," said an Irishman,

standing hard by,

With a humorous shrug, and a wink of

his eye,

"He's not sich afool, I swear by the crass,

"To do any sich thing, I should count him an ass;

"He's gone off to glory, where

he's free from all sorrow,

"If he's not there to-night,

he'll be there to-morrow,

"And Heaven I'm sure has

forgiven his sin,

"For I saw the sky open, and saw

him pop in."

* This poem was probably written on the

occasion of Kirkby's first flight from Cincinnati. Liberty

Hall and Cincinnati Gazette, January 8, 1835.

TOM D. CROUCH

Thomas Kirkby:

Pioneer Aeronaut in Ohio

The decade of the 1830's marked the dawn

of American aeronautical history.

Although the first American balloon

ascent had been made on June 24, 1784, when

Edward Warren, a thirteen year old

Baltimore lad made a captive flight in a home-

made balloon, the citizens of the young

republic remained aloof from so impracti-

cal an enterprise as free ballooning.1

The American tour of Jean Pierre Blanchard

in 1793 demonstrated that even a highly

successful European aeronaut, the first

man to fly the English Channel, could

rarely draw a large enough crowd of paying

spectators to meet his expenses. While

the flights of Louis-Charles Guille in 1819

and Eugene Robertson in 1825 attracted

wide attention, balloon ascents remained

infrequent and were confined to the

large cities of the East Coast.2

The return of Charles Ferson Durant to

the United States in 1830 heralded a

"golden age" of American

aerostation. Having studied in Europe with Eugene

Robertson, Durant was to become the

nation's first professional aeronaut. His

ascents were well publicized and

attended. Durant's first American flight, at Castle

Garden, New York, was followed by a

national tour which proved that an aero-

naut could profitably devote full time

to ballooning. George Elliot, Samuel Wal-

lace, Hugh Parker, Nicholas Ash, and

others followed his lead in introducing the

wonders of manned flight to the people

of New York, Baltimore, and Charleston.

Despite the fact that no ascents had

been made in the state, Ohioans had taken

an early interest in aeronautics. As

early as 1815 a Mr. Gaston had announced to

the citizens of Cincinnati that he would

release a large free balloon prior to a fire-

works demonstration.3 Cincinnati

newspapers carried front page accounts of major

European and American ascents, placing

particular emphasis on such sensational

events as the death of Madame Blanchard

in 1819.4 The "aerial steam-boat" con-

1. Jeremiah Milbank, Jr., The First

Century of Flight in America: An Introductory Survey (Princeton,

1943). Milbank offers a fine

introduction to nineteenth century ballooning.

2. Ibid., 35. Milbank reports that Louis-Charles Guille brought a

balloon to Cincinnati in 1819.

However, a check of the city's

newspapers for the period failed to disclose any mention of his presence.

In view of the fact that the Cincinnati

papers regularly printed accounts of Guille's eastern ascents, it

seems improbable that they would have

ignored a flight in their own city.

3. Cincinnati Liberty Hall, May

15, 1815. Gaston's Fourth of July exhibitions were a yearly tra-

dition in Cincinnati. The balloon

portion of the program was evidently designed to attract crowds for

the more important pyrotechnic display.

Although Gaston's aerostat was large enough to carry a man,

no manned flights were attempted.

4. Mme. Madeline-Sophie Blanchard, wife

of aeronaut Jean Blanchard died when her balloon

caught fire during a fireworks

exhibition in Paris.

Mr. Crouch is supervisor of education at

the Ohio Historical Society.

(614) 297-2300