Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

CARY D. WINTZ

Race and Realism in

the Fiction of

Charles W.Chesnutt

In this day of increased awareness of

the role blacks have played in American history

and culture it is somewhat surprising

that Charles W. Chesnutt is only recently being

recognized by students of history and

literature. He played an important part in the

development of black American literature

during the last decade of the nineteenth

century, and also helped to lay the

foundation for the "Negro Renaissance" of the

1920's. For his contemporaries,

including William Dean Howells, the first publication

of his short stories in The Atlantic

Monthly marked the "coming of age" of Negro

literature. This was the first time

black literature had appeared in a major literary

journal without the tacit understanding

that it was inferior to white fiction.1

Initially, at least, critics judged

Chesnutt's work on the basis of its artistic merits

and not according to the color of its

creator. To disregard his race, however, is to

avoid coming to terms with the essence

of Chesnutt's literature and to ignore com-

pletely the one major theme that runs

through his work. In referring to the Negro

author's work, Howells naively noted,

"in this [the field of literature] there is, happily

no color line."2 Mr.

Howells, of course, was seriously mistaken. Not only was there

a color line in literature, but also it

is totally inaccurate to expect there would be no

difference in the artistic expression of

blacks and whites. Indeed, the major significance

of Chesnutt is that he was black, not

white, and that he was one of the first to success-

fully depict the condition of blacks in

post-Civil War America. In doing so, however,

he ran counter to the accepted practice

of white writers to use the widespread racial

prejudice and increasing antipathy

toward the Negro for popular literary success.

Thus we are faced with the dualism which

permeates Chesnutt's work, as well as

black literature in general of the

period. On the one hand we see the attempt to

accurately present black experience and

the true aspirations of Negro life in America.

This entailed the discussion of themes

and problems that generally fell outside of

white experience, that often went

against the political and social beliefs of white

society and frequently invoked hostility

in the majority of whites. On the other hand

1. Hugh

M. Gloster, "Charles W. Chesnutt:

Pioneer in the Fiction of Negro Life," Phylon, II

(1941), 57. Three of Chesnutt's novels, The

Conjure Woman, The Marrow of Tradition, and

The Wife of His Youth, were printed in paperback editions in 1969 by the

University of Michigan

Press.

2. William Dean Howells, "Mr.

Charles W. Chesnutt's Stories," Atlantic Monthly, LXXXV

(1900), 700.

Mr. Wintz is Instructor of History,

Texas Southern University, Houston, Texas.

|

|

|

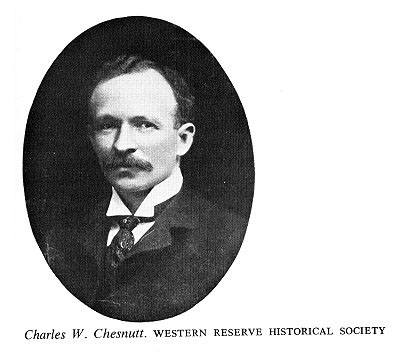

there was the desire of Chesnutt and other black writers to win acceptance by the white literary establishment, resulting in the frustrating attempt to develop their work within the framework of contemporary American literature. It is necessary to evaluate Chesnutt's work against this basically hostile environment.3 Chestnutt was born in Cleveland on June 20, 1858. His parents were free Negroes who had moved from North Carolina two years earlier. After the Civil War, the family returned to Fayetteville, North Carolina, where Chestnutt grew up and was educated. By age twenty-two he had achieved virtually the highest success a black would obtain in the South when he was appointed principal of the Normal School in Fayetteville. Convinced that he would find greater opportunity in the North, Ches- nutt returned to Cleveland where he spent the rest of his life and where he was able to earn a comfortable living as a lawyer, a writer, and a highly skilled court reporter.4 Chesnutt's first success in writing came in 1887 when The Atlantic Monthly pub- lished one of his first short stories, "The Goophered Grapevine." This story and six others were later published in Chesnutt's first book, The Conjure Woman. These first stories were somewhat similar to the folk tales of Joel Chandler Harris. Like Harris, Chesnutt created an old Negro character, Uncle Julius, who related old plantation folk stories and legends to a white audience. Beyond this, however, there was little relationship between the "Uncle Julius" and the "Uncle Remus" stories. Chesnutt's stories, with the exception of the "Goophered Grapevine" which was based

3. For discussion of pressures on black writers, see James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way (New York, 1961), 158-161; for example of white writers utilizing widespread racial prejudice for popular literary success, see Thomas Dixon, The Leopard's Spots (New York, 1902) and Harold Bell Wright, The Winning of Barbara Worth (New York, 1911). 4. For a more complete account of Chesnutt's life see Helen M. Chesnutt, Charles W. Chesnutt: Pioneer of the Color Line (Chapel Hill, 1952). Miss Chesnutt's biography is especially valuable in that it quotes extensively from Mr. Chesnutt's letters and journal. |

124 OHIO HISTORY

on an old plantation folk legend, were

all the product of his imagination although they

were presented in the form of folk

tales.

The format of The Conjure Woman was

quite simple and fairly traditional. It was

a collection of stories concerning a

wealthy white couple who moved from the Cleve-

land area to North Carolina in hopes of

regaining the wife's health in a warmer climate

as well as reestablishing the grape culture

of the region. In the course of their activi-

ties they encountered Uncle Julius,

"who was not entirely black" and had "a shrewd-

ness in his eyes, too, which was not

altogether African," and he recounted folk

legends concerning slave life to amuse

the family. The common element of his stories

was that each involved a "conjure

woman" or sorceress as a major factor in the plot.

Beneath this deceptive facade,

Chesnutt's stories were his own creations. Uncle

Julius was a fully developed and complex

character. On one hand he appeared as the

typical Uncle Tom, shuffling, jiving,

and entertaining the white folks with his quaint

and childishly superstitious tales of

antebellum life. Superficially, Uncle Julius' tales

were about a race of children--a simple

and charmingly ignorant people who were

ideally suited to slavery and required

the parental welfare system provided by the

benevolent planter.

Actually, both Uncle Julius and his

stories have a much deeper meaning. Julius

was really a sly, almost Machiavellian

old man who always had a motive, sometimes

selfish, sometimes noble, behind his

actions. For example, in "The Conjurer's

Revenge" Julius recounted to his

employer, the vineyard owner, a tale about a con-

jured mule and persuaded him to buy his

friend's horse instead of the "metamor-

phosed unfortunate." Julius then

supposedly received on the side a generous com-

mission from the friend, who had been

able to sell his worthless animal. In "Po'

Sandy" he prevented the wrecking of

an old schoolhouse, which his fellow parish-

ioners wished to use as a church, by

telling his employer's wife a sentimental tale

about the building. As a result of an

unfortunate set of circumstances it was haunted

by the ghost of a slave who had been

"goophered" or conjured into the tree that had

been accidentally used to provide the

lumber for the building before the spell could

be lifted. Uncle Julius thus emerged not

as an Uncle Tom, but as an astute old

Negro who took advantage of the white

woman's gullibility and sympathies and turned

the white's belief that the blacks lack

serious mental capacity back on to the origi-

nators of the myth.5 In this

sense Julius was typical of the "hustler" whose affectations

reinforced the stereotype of black

inferiority, but who was slyly turning every possible

opportunity to his own advantages,

without, however, ever confronting the political

and social dominance of the white

majority.

Julius' stories were deceptive in other

ways also. Throughout them Chestnutt wove a

delicate pattern of racial oppression

and the inhumanity of slavery. He handled this

theme so subtly that the reader is often

only half aware of it. In this collection of

stories Chesnutt avoided melodrama and

did not cloud the issue with sentimental

rhetoric or propaganda. Instead, by

describing the situation realistically and simply

he revealed the full horror of slavery.

Refraining from discussing either cruel masters

or rebellious slaves, the author

demonstrated the inhumanity encountered by "good

slaves" and how even

well-intentioned and humane slave owners were corrupted by

the system.

The fate of the good slave was depicted

in "Po' Sandy" the same one who had been

5. Charles W. Chesnutt,

The Conjure Woman (Cambridge, 1899), 10, 135.

Fiction of Charles Chesnutt 125

"goophered" into a tree. Poor

Sandy was the best slave of "Mars Marrabo's" planta-

tion--so good in fact that Mr. Marrabo's

children regularly borrowed him to help

out on their own plantations. Once when

Sandy returned he discovered that while

he was gone his wife had been traded

away for another slave woman. Magnanimously,

"Mars Marrabo gin'im a dollar, en

'lowed he wuz monst'us sorry fer ter break up de

fambly, but de spekilater had gin 'im

big boot, en times wuz hard en money skaese, en

so he wuz bleedst ter make de

trade." Sandy recovered from this imposition and

eventually married the new woman, but he

still remained disturbed by the uncertainty

of his master's generosity, or

gullibility, as the case may be. Also he expressed fear

that his new wife would also be sold or

traded while he was absent: "I'm gittin'

monst' us ti'ed er dish yer gwine roun'

so much .... I wisht I wuz a tree, er a stump, er a

rock er sump'n w'at could stay on de

plantation fer a w'ile." Sandy's wife, who con-

fessed that she was a conjure woman,

granted him this wish; but their hope for a life

free from interference ended in even

more grief for both of them.6

In "Sis' Becky's Pickaninny"

Chesnutt again described the cruel destruction of a

black family, this time showing how

slavery and the accompanying racism forced

the weak, but kind, planter to become a

party to the evil deed. Sister Becky's first

crisis came when her husband from a

neighboring plantation was sold down to New

Orleans following the death of his

master. Becky's master Colonel Pendleton, would

have bought her husband except he had

lost too much money betting on horses.

Pendleton's weakness for race horses

also separated Becky from her infant son when

he traded her for a prize-winning horse.

When the Colonel, who was aware of the

bond between Becky and her baby, tried

to convince the trader to take the child also,

he was told, "I doan raise niggers;

I raises hosses, en I doan wanter be both'rin' wid

no nigger babies. Nemmine de baby. I'll

keep dat 'oman so busy she'll fergit de baby;

fer niggers is made ter work, en dey

ain' got no time fer no sich foolis'ness ez babies."7

Colonel Pendleton accepted the logic of

this argument and Becky lost her baby.

The loss would have been permanent if

the magic of a conjure woman had not con-

vinced both men that they had been

cheated, and the horse and Becky were returned

to their original owners.

In each of the other stories in The

Conjure Woman Chesnutt presented an ad-

ditional example of the difficulties

Negroes faced during slavery. These problems

rarely resulted from the cruelty of the

planter, but arose from the nature of the slave

system which gave the slaves no control

over their lives. Their only resource of

power was the magic of the conjure

woman; the use of this magic became, then, a

means of resistance or even subtle

rebellion against the system that oppressed them.

Chesnutt's second collection of short

stories, The Wife of His Youth and Other

Stories of the Color Line, was published in 1899, the same year The Conjure

Woman

appeared. In this second volume Chesnutt

turned his attention to the racial problems

of blacks after emancipation. Whereas

the first was set in rural North Carolina and

was somewhat guarded in its discussion

of race, The Wife of His Youth directly and

openly dealt with racial questions both

in the rural South and in the newly arising

northern urban ghettos. Instead of

restricting himself to the relatively non-contro-

versial issue of slavery, Chesnutt now

turned to the emotional and highly explosive

subjects of racism, intermarriage, the

problem of "passing," and racial distinction and

6. Ibid., 42, 44-45.

7. Ibid., 141-142.

126 OHIO HISTORY

prejudice within the black community

itself. The cautious and hesitant approach of

his first stories was discarded in favor

of a direct frontal attack on racism.

The reception of Chesnutt's second book,

although relatively favorable, was not

as enthusiastic as that of The

Conjure Woman. A female reviewer writing in The

Bookman sounded a particularly ominous note in reaction to the

particular racial

problem considered in one of the nine

stories, "The Sheriff's Children." The story

involved a sheriff, who while attempting

to protect a black prisoner from an angry

lynch mob, discovered that the prisoner

was his own son. In a confrontation between

father and son, the sheriff felt remorse

because of the heartlessness with which he

had treated the child and its mother

years ago. The son, on the other hand, was

willing to kill his white father, both

to avenge the injustices of the past and in order

to escape the terrible death he was sure

to receive from the mob. In attempting to

come to terms with the psychological

conflicts of mulatto-white relationships in his

direct treatment of the scene, Chesnutt

exposed the realities of the color line through

literature. The reviewer, while not

denying the potential reality of the situation in

the story, criticized the author for a

lack of good taste in his handling of the subject:

" 'The Sheriff's Children'

furnishes, perhaps, the most shocking instance of his reckless

disregard of matters respected by more

experienced [white?] writers. In saying this

there is no intention to deny the too

probable truth of the untellable story. .. ."8

Actually several fairly serious

weaknesses are revealed in Chesnutt's writing in

Wife of His Youth. As he became more directly involved with developing the

prob-

lems of race, the literary quality of

his work suffered, according to modern standards.

The plots in this book tended to be

melodramatic, and the characters were often

poorly developed. Curiously, while he

experimented with a more realistic treatment

of racial issues and portrayal of subtle

psychological problems resulting from racial

discrimination and racial conflict, his

characters and language at times lacked de-

velopment and realism, and the stories

seemed to be written for immature rather than

adult readers. This pattern was

continued in the three novels which the Ohioan pub-

lished between 1900 and 1905.

In 1904, however, Chesnutt clearly

demonstrated his ability as a writer in the

superb short short story, "Baxter's

Procrusters." As one critic, Vernon Loggins, has

pointed out, this story "is not

only Mr. Chesnutt's most artistic achievement, but it is

perhaps the best short story which any

American Negro has yet written."9 Ironically,

"Baxter's Procrusters" was the

only story which does not deal with race at all.

Although Chesnutt's novels are defective

in many respects, they are significant

because they present the complete

development of the author's racial theme. In each

of the novels Chesnutt discussed a

different aspect of the unfolding tragedy of the

black man in America. In his first

novel, The House Behind the Cedars (1900),

he examined the social and psychological

stresses involved in "passing," and the

complications this act brought to

personal relations between persons of different races.

The heroine of the novel was a light

skinned mulatto girl who passed for white and

became engaged to an upper-class white

man. When her masquerade was exposed,

the young woman found herself unable to

relate to either race and became a victim

of the racism of both the white and

black world.

Chesnutt's second novel, The Marrow

of Tradition (1901), was concerned with

8. Nancy Huston Banks, review of Wife

of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line,

by Charles W. Chesnutt, The Bookman, X

(1900), 597.

9. Vernon Loggins, The Negro Author:

His Development in America to 1900 (New York,

1961), 318-319.

Fiction of Charles Chesnutt 127

the many problems encountered by former

slaves when they endeavored to become

part of white society in the years

following emancipation. Chesnutt was especially

concerned with describing the stubborn

white opposition blacks faced when they

attempted to assert their basic rights. The

Marrow of Tradition is based on the race

riots which occurred in Wilmington,

North Carolina, in 1898, and the author at-

tempted to analyze the social and

political forces in the white community that culmi-

nated in the massacre. Also examined are

the alternative approaches, accommoda-

tion and militancy, which were open to

blacks confronting white dominated society.

The dilemma of choosing between the two

extremes, however, was unresolved. Ac-

commodation meant impotency, which left

blacks entirely at the mercy of a hostile

white society; militancy, while

honorable and courageous, was suicidal.

The reality which Chesnutt described in The

Marrow of Tradition was not one

which offered much hope for the southern

blacks. None of Chesnutt's characters

were able to work out a viable

relationship with white society. Sandy and Jerry, for

example, sought accommodation through

service. Sandy, formerly the faithful slave

but now servant of an old southern

gentlemen, was barely saved from lynching when

his employer interceded on his behalf.

Though rescued, Sandy's future was dim.

Southern aristocracy was clearly dying,

and with it the paternalistic protectoral re-

lationship, such as that between Sandy

and old Mr. Delamere, appeared doomed.

There was at least some dignity

preserved in the relationship between Sandy and

Mr. Delamere. There was none, however,

between Jerry and Major Carteret. Jerry's

service involved constant humiliation,

both direct and indirect at the hands of the

Major and his political associates.

Jerry's livelihood depended on his ability to hustle

tips; like Sandy he linked his survival

to the protection of his white patron. At best

this solution was a tragic one. Jerry's

position involved rejection of his blackness, a

betrayal of his race, and a surrendering

of his rights as a citizen. When the crisis

finally came, Jerry's pleas for help

went unheard and he was destroyed by the mob

set in motion by Major Carteret.10 Clearly

Chesnutt argued that even if the black

man accepted servitude, he could no

longer rely on the protection of white society.

The South was changing, and with the

extinction of the old southern aristocracy the

Negro was left defenseless.

Having rejected continued servitude as a

viable solution to the black man's prob-

lems, Chesnutt then turned to the

question of the black man's political position vis a

vis white society. Two characters are used to illustrate

the conflict between opposing

alternatives. One, Dr. Miller,

represented the wealthy, well educated upper-class

Negro who accepted the political

position of accommodation, Miller (like Booker T.

Washington) was convinced that practical

education was what was needed to uplift

the blacks. Once blacks learned a useful

trade they would win the respect of the

whites and they would be given their

political rights. In the meantime they must be

cautious and patient. Miller's own

patience was tested early in the story. While

traveling by railroad from Philadelphia

to North Carolina he was forced to ride in

the Jim Crow car after the train entered

Virginia. Although his white traveling com-

panion protested vigorously, Miller

accepted the outrage calmly. As Chesnutt ex-

plained:

Miller was something of a philosopher.

He had long ago had the conclusion forced upon

10. Charles W. Chesnutt, The Marrow

of Tradition (Boston 1901), 307.

11. Ibid., 59-60.

128 OHIO

HISTORY

him that an educated man of his race, in

order to live comfortably in the United States,

must be either a philosopher or a

fool...11

Josh Green represented the other

extreme. He was poor and uneducated; the

consuming passion in his life was to

avenge the lynching of his father. Like Dr. Miller,

he too was somewhat of a philosopher.

More clearly than Miller, however, he saw

through the hypocrisy of white morality,

especially when it told the blacks that they

should forgive their enemies. He was

also impatient with Miller's advice that he

should turn the other cheek:

"Yas, suh, I've l'arnt all dat in

Sunday-school, an' I've heared de preachers say it time an'

time ag'in. But it 'pears ter me dat dis

fergitfulniss an' fergivniss is mighty one sided.

De w'ite folks don' fergive nothin' de

niggers does. Dey got up de Ku-Klux, dey said,

on 'count er de kyarpit-baggers. Dey

be'n talkin' 'bout de kyarpit-baggers ever sence, an'

dey 'pears ter fergot all 'bout de

Ku-Klux. But I ain' fergot. De niggers is be'n train' ter

fergiveniss; an' fer fear dey might

fergit how ter fergive, de w'ite folks gives 'em somethin'

new ev'y now an' den, ter practice on. A

w'ite man kin do w'at he wants ter a nigger, but

de minute de niggers gits back at 'im,

up goes de nigger, an' don' come down tell somebody

cuts 'im down. If a nigger gits a'

office, er de race 'pears ter be prosperin' too much, de w'ite

folks up an' kills a few, so dat de res'

kin keep on fergivin' an' bein' thankful dat dey're

lef' alive. Don't talk ter me 'bout dese

w'ite folks--I knows em, I does! Ef a nigger

wants ter git down on his marrow-bones,

an' eat dirt, an' call 'em 'marster,' he's a good

nigger, dere's a room fer him. But

I ain' no w'ite folks' nigger, I ain'. I don' call no man

'marster.' "12

The confrontation between these two

positions occurred during the race riot.

When the whites launched their attack on

blacks of Wilmington, Josh Green organized

an armed defensive force and asked Dr.

Miller to become the leader. Miller argued

reason instead of futile heroics.

"My advice is not heroic, but I

think it is wise. In this riot we are placed as we should be

in a war: we have no territory, no base

of supplies, no organization, no outside sympathy,

--we stand in the position of a race, in

a case like this, without money and without

friends. Our time will come,--the time

when we can command respect for our rights;

but it is not yet in sight. Give it up,

boys, and wait. Good may come of this, after all."13

Josh Green did not buy this empty

illusion of hope offered by Dr. Miller. He turned

away with the comment: "Come along,

boys! Dese gentlemen may have somethin'

ter live fer; but ez fer my pa't, I'd

ruther be a dead nigger any day dan a live dog!"14

Josh lost his life, ironically, in a

vain attempt to protect Dr. Miller's hospital and

nursing school from the mob. Dr.

Miller's son was killed by the same mob.

Chesnutt did not attempt to solve the

dilemma. Clearly both alternatives were

tragic. Josh's action was noble, but it

was also futile and it cost him his life. Although

Dr. Miller survived, he lost everything

that he had worked for and loved except his

wife. The real tragedy was that the

black man had no viable choice. As Dr. Miller

correctly pointed out, they had no

friends or allies to help them in their struggle.

The tragedy of the black man was also a

tragedy for the South. Chesnutt refused

to accept the separation of the two

races. In his novel he indicated this by making

12. Ibid., 113-114.

13. Ibid., 283.

14. Ibid., 284.

Fiction of Charles Chesnutt 129

the wives of two of the major

protagonists, Dr. Miller and Major Carteret, half-

sisters. Chesnutt concluded his novel

with a confrontation between the two women.

Significantly it was only Dr. Miller who

could prevent the final tragedy begun with the

riot. Major Carteret's son was dying,

and Dr. Miller was the only man available to

save him. Mrs. Carteret pleaded with her

sister to allow Dr. Miller to attend the sick

child. Mrs. Miller rejected her sister's

offers of recognition and conciliation now

presented after twenty-five years, but

she sent her husband out on the mission. Ches-

nutt here offered his only hint of

optimism. He suggested that the fate of the races

was bound together and that it was the

black man who held the solution. This is not a

unique position. A number of his

contemporaries argued that the viability of Ameri-

can society depends upon the successful

solution of the race problem. The problem

was crucial, for as Chesnutt concluded

in The Marrow of Tradition, "there is time

enough, but none to spare."15

Chesnutt's last novel was his most

pessimistic. In The Colonel's Dream (1905)

the ineffectiveness of well-intentioned

liberals in upgrading the social and economic

conditions in the South were exposed by

their failure to take into account the realities

of racial prejudice. Colonel French, the

main character in the novel, returned to his

home in the South after spending a

number of years in the North where he had ac-

quired a fortune and a number of liberal

racial ideas. His attempt to revive the

stagnant economy and reform the town

were applauded by the local population until

he began to attack racial injustice. In

the ensuing power struggle Colonel French's

dream was shattered, and he retreated in

defeat to the North leaving conditions in the

town in substantially no better shape

than when he arrived.

The tragedy that Chesnutt portrayed in

the novel was the inability of either northern

liberals or southern aristocrats to

resist the racial attitudes that were a part of southern

life and politics. Even though, as

Chesnutt contends, many of the prominent south-

erners recognized that racial oppression

was unjust, reactionary, and opposed to the

best interest of the South, they did not

have the courage or the strength to express

these views publicly. All Colonel French

succeeded in doing by opposing racial

injustice was to isolate himself from

most of the southern community.16

The conclusion at which Chesnutt arrived

was that the Civil War and emancipation

did nothing basically to alter the

situation of the black man in southern society. New

forms, such as the convict labor system

and the crop lien system, still undermined

the freedom of blacks. New masters which

supplanted the old southern aristocracy

continued to prosper off the system

which suppressed the blacks. Colonel French,

who combined the qualities of southern

aristocrats and northern liberals, underesti-

mated how deep-rooted and

well-entrenched southern social institutions were. He

failed in his dream to create a

"regenerated South, filled with thriving industries, and

thronged with a prosperous and happy

people." In spite of the pessimism of the

novel, Chesnutt concluded on a somewhat

optimistic note, hoping that ultimately

the Colonel's ideas of regenerating the

South through industrial development will be

carried forth by others and that

ultimately oppression and stagnation will be elimi-

nated. For the present, however,

Chesnutt saw no improvement of the black man's

situation in the South.17

The historical background against which

Chesnutt developed his pessimistic view

15. Ibid., 329.

16. Charles W. Chesnutt, The

Colonel's Dream (New York, 1905), 194-195.

17. Ibid., 280-281, 293.

130 OHIO

HISTORY

of the racial situation hardly inspired

any other interpretation. The "industrial educa-

tion" and accommodation championed

by Booker T. Washington was losing its appeal

for many Negro intellectuals as a result

of the deteriorating position of blacks in the

South. During the years around the turn

of the century there was a dramatic increase

in the amount of racial violence, both

in the number of lynchings and in the number

of brutal attacks on Negroes, such as

occurred in Wilmington in 1898. In addition

to this, there was an increase in the

popularity of pseudo-scientific racist beliefs which

provided an ideological basis for both

American imperialism and the oppression of

blacks.

Following the publication of The

Colonel's Dream, Chesnutt quit writing. Ap-

parently, he was thoroughly

disillusioned both with his failure to rally public support

against the racial oppression that was

increasing daily and with his failure to achieve

the literary success he desired. This

latter failure was particularly disappointing.

Chesnutt's novels simply did not sell.

Judging by today's works, he was not a great

writer. His literary weaknesses were

manifested most clearly in his inability to develop

his characters fully. At best Chesnutt's

characters appear dull, stiff, and unbelievable;

at their worst, they are flat, one

dimensional stereotypes. In The Marrow of Tradition,

for example, Tom Delamere is an

unbelievable embodiment of corruption and de-

cadence while Lee Ellis is equally

unbelievable as a combination of honor and good.

Even Chesnutt's most developed

characters, such as Major Carteret in The Marrow

of Tradition and Colonel French in The Colonel's Dream, fail

to come alive for the

reader. Nevertheless, no matter how weak

he is stylistically, the themes developed in

his novels are both significant and

original portrayals of the black experience in

America. Actually, it appears that it

was Chesnutt's strength in this area rather than

his weaknesses as a writer that limited

his success.

Artistic limitations, in fact, seldom

prevent a novel from becoming a best seller.

During the decade Chesnutt was writing,

many of the best sellers, those of Harold

Bell Wright, for example, were as

melodramatic and stylistically weak as Chesnutt's

were. However, Chesnutt's insistent

exposure of racial problems alienated potential

book buyers. Although the white author,

Thomas Dixon, published two blatantly

racist novels, The Leopard's Spots (1902)

and The Clansman (1905), which en-

joyed great commercial success, it was

not until the literary "renaissance" in Harlem

following the First World War that black

writers found any substantial audience for

works reflecting their racial views.

Even James Weldon Johnson's Autobiography

of an Ex-Coloured Man, a book of unquestionable literary merit, was virtually

un-

noticed when it was first published in

1912. Its success came only after it was re-

printed in 1927, when the merits of

Negro literature were more fully recognized.

About this time, also, Chesnutt was

awarded the Spingarn Medal for his 'pioneer

work as a literary artist depicting the

life and struggle of Americans of Negro de-

scent ....' Even though he no longer

wrote for publication, Chesnutt continued his

'long and useful career as a scholar,

worker and freeman in one of America's greatest

cities.'18

18. Irving J. Sloan, comp., Blacks in

America, 1492-1970: A Chronology and Fact Book

(Dobbs Ferry, 1971), 26, 29. The

Spingarn Medal is awarded to "colored Americans" for "dis-

tinguished merit and achievement." It was first instituted by Joel E. Spingarn,

chairman of the

board of directors of the NAACP on May

13, 1914, and is awarded yearly. Chesnutt's award

was given for 1928; he died November 15,

1932.

CARY D. WINTZ

Race and Realism in

the Fiction of

Charles W.Chesnutt

In this day of increased awareness of

the role blacks have played in American history

and culture it is somewhat surprising

that Charles W. Chesnutt is only recently being

recognized by students of history and

literature. He played an important part in the

development of black American literature

during the last decade of the nineteenth

century, and also helped to lay the

foundation for the "Negro Renaissance" of the

1920's. For his contemporaries,

including William Dean Howells, the first publication

of his short stories in The Atlantic

Monthly marked the "coming of age" of Negro

literature. This was the first time

black literature had appeared in a major literary

journal without the tacit understanding

that it was inferior to white fiction.1

Initially, at least, critics judged

Chesnutt's work on the basis of its artistic merits

and not according to the color of its

creator. To disregard his race, however, is to

avoid coming to terms with the essence

of Chesnutt's literature and to ignore com-

pletely the one major theme that runs

through his work. In referring to the Negro

author's work, Howells naively noted,

"in this [the field of literature] there is, happily

no color line."2 Mr.

Howells, of course, was seriously mistaken. Not only was there

a color line in literature, but also it

is totally inaccurate to expect there would be no

difference in the artistic expression of

blacks and whites. Indeed, the major significance

of Chesnutt is that he was black, not

white, and that he was one of the first to success-

fully depict the condition of blacks in

post-Civil War America. In doing so, however,

he ran counter to the accepted practice

of white writers to use the widespread racial

prejudice and increasing antipathy

toward the Negro for popular literary success.

Thus we are faced with the dualism which

permeates Chesnutt's work, as well as

black literature in general of the

period. On the one hand we see the attempt to

accurately present black experience and

the true aspirations of Negro life in America.

This entailed the discussion of themes

and problems that generally fell outside of

white experience, that often went

against the political and social beliefs of white

society and frequently invoked hostility

in the majority of whites. On the other hand

1. Hugh

M. Gloster, "Charles W. Chesnutt:

Pioneer in the Fiction of Negro Life," Phylon, II

(1941), 57. Three of Chesnutt's novels, The

Conjure Woman, The Marrow of Tradition, and

The Wife of His Youth, were printed in paperback editions in 1969 by the

University of Michigan

Press.

2. William Dean Howells, "Mr.

Charles W. Chesnutt's Stories," Atlantic Monthly, LXXXV

(1900), 700.

Mr. Wintz is Instructor of History,

Texas Southern University, Houston, Texas.

(614) 297-2300