Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

DONALD J. RATCLIFFE

Captain James Riley and Antislavery

Sentiment in Ohio, 1819-1824

Captain James Riley had an unusually

powerful reason for hating slavery: he had

himself been a slave.

Riley was born in 1777 in Middletown,

Connecticut, the fourth child of a humble

farming family. Between the ages of

eight and fourteen he attended common school

while earning his keep by working for

local farmers. At the age of fifteen, tired of

hard work on the land, he decided to

turn to a seafaring life. During the next twenty

years, as seaman and merchant, he

traveled widely, "making voyages in all climates

usually visited by American ships,"

but mainly to South America, the Caribbean, and

western Europe. The years of maritime

conflict with Britain and France after 1806

proved as financially disastrous to

Riley as to most other American overseas mer-

chants, and he spent the War of 1812 at

home in Connecticut trying to provide a

regular living for his wife and four

children. After the war when Riley again em-

barked on an overseas trading venture,

he suffered such a disastrous and agonizing

experience that he decided

"never" again to leave his native country.1

For a brief period after 1815 Riley

acted as a lobbyist in Washington, but his eyes

soon turned to the developing lands of

the West. In 1818 he traveled through Ken-

tucky, the Old Northwest and Upper

Canada. In 1819 he secured the office of deputy

surveyor of the public lands, a post for

which the technical skills he had learned as a

navigator qualified him. His particular

task was to survey the lands in the Maumee

River Valley recently purchased from the

Indians. Through his surveys the enter-

prising Riley offered the first

practical demonstration of the feasibility of connecting

the Wabash and Maumee rivers by a canal.

Deciding to settle in this promising land,

Riley moved his family in 1820 from New

England, first to Chillicothe, and then, in

the following year, to a frontier home

on the St. Mary's River near the Indiana line.

Here, with the aid of his sons, this

"large and powerful" man established the first

settlement in Van Wert County, Ohio, and

in 1822 laid out the town of Willshire. A

figure of local prominence, Riley was

elected to represent the sparsely settled north-

western counties in the General Assembly

for the session of 1823-24. In the legisla-

ture he was an eager advocate of schemes

for internal improvement, especially those

which would benefit his own locality.

Unfortunately, ill-health soon forced him to

1. James Riley, An Authentic

Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce . . .

revised ed., Hartford, Conn., 1829),

15-18, 260.

Mr. Ratcliffe is Lecturer in Modern History,

University of Durham, England.

|

|

|

give up frontier life, and in 1826 he returned East to live in New York.2 Two years later he took to the sea again, and in 1831 he began to pioneer American trade with Morocco. He died at sea in March 1840.3 The adventure which made Captain Riley famous occurred immediately after the War of 1812. He was sailing the brig Commerce, as the supercargo and master, from Gibraltar to the Cape Verde Islands in August 1815 when the ship was wrecked on the coast of Africa. Riley and the crew reached the shore safely, but were attacked by savages who killed one of the sailors. Miraculously the Americans escaped in the ship's damaged long boat and sailed down the coast until finally forced to beach their

2. His years in Ohio are documented in W. Willshire Riley, Sequel to Riley's Narrative: Being a Sketch of Interesting Incidents in the Life, Voyages and Travels of Capt. James Riley ... (Colum- bus, 1851), 17-29, 396-411; "Reminiscences by W. Willshire Riley," in History of Van Wert and Mercer Counties, Ohio . . . (Wapakoneta, Ohio, 1882), 244-253, and, in part, in Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio (Columbus, 1891), III, 413-416, 418-420; James Riley to John F. Watson, July 3, 1824, in Northwest Ohio Quarterly, XVI (1944), 41-44. Both the introduction to this letter and Henry Howe's brief account of Riley contain a number of factual errors. Ibid., 41; Howe, Historical Collections (Cincinnati, 1847), 497, and (Columbus, 1891), III, 410. For Riley's survey of the Maumee-Wabash canal route, see W. W. Riley, Sequel, 401-403, 406, and Logan Esarey, A History of Indiana from Its Exploration to 1850 (Indianapolis, 1915), 354, 356. For Riley's brief political career in Ohio, see Ohio General Assembly, House Journal, 1824 and James Watson Riley to Governor Jeremiah Morrow, April 10, 1824, Morrow Papers, Ohio Historical Society. Two of Riley's sons made their careers in Ohio, where the eldest, James Watson Riley, founded the town of Van Wert. W. W. Riley, Sequel, 29, 49, 154; Howe, Historical Collections (1891), III, 409. 3. For these later years, during which he traveled widely in France and Morocco, see W. W. Riley, Sequel, 30-328. |

|

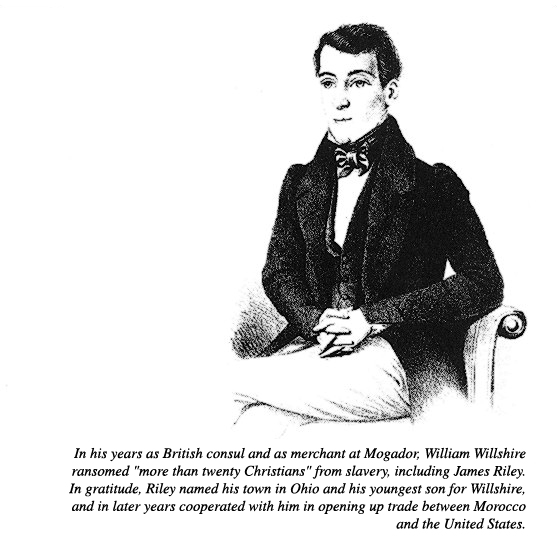

sinking craft. The point where they landed proved desolate and devoid of both vege- tation and water. Thirst and starvation seemed inevitable. The castaways were saved only when a band of wandering Arabs chanced upon them and seized them as slaves. The captives were stripped of their clothes and then carried off into the Sahara. With no protection from the sun, their skin and flesh were literally roasted off. Only a meager daily ration of camel's milk kept them alive. Fortunately the party of nomads met two Arab traders in the desert. The ingenious Riley, by means of sign language and a smattering of Spanish, told these merchants that a generous ransom would be paid for him and his fellow Americans at Mogador in Morocco, though in fact he knew no one there. Nevertheless, the merchants be- lieved him, and purchased both Riley and four of his companions. Then followed a terrible journey across the Sahara Desert to Mogador, a journey in which they suffered severely from heat, thirst, hunger, and sores. Bands of robbers tried to cap- ture such valuable slaves, and corrupt local rulers threatened to confiscate them. Through remarkable good fortune the five Americans all survived the trip, and found at Mogador a British consul named William Willshire who ransomed them for the |

James Riley 79

princely sum of $920 and two

double-barrelled shotguns. After his two month

ordeal, Riley's weight was reduced from

240 pounds to ninety pounds, and his bones

"appeared white and transparent

through their thin and grisly covering."4

When Riley arrived in Washington to

arrange for the reimbursement of Willshire

and the redemption of the rest of his

crew, should they ever be found alive, his story

so impressed many distinguished

Americans, including James Monroe, that they per-

suaded him to write an account of his

ordeal.5 He submitted the manuscript to a

New York publisher, who considered it

carelessly written and in need of revision;

consequently, on the advice of the young

Thurlow Weed, he "availed himself of the

services of a school-teacher, who

improved the whole narrative in its style and

grammar."6 This book,

first published in 1816, transformed Riley into a celebrity and

distinguished him from the many other

seamen, European and American, who had

suffered a similar fate in that part of

Africa.7 His Authentic Narrative immediately

became a best seller on both sides of

the Atlantic, and at least nine editions were

printed in the first five

years--including one edition published in Chillicothe in 1820.

Reissued with minor revisions in 1829,

the book was regularly reprinted down to the

Civil War; in 1851 Riley's son claimed

that it had been read by over one million

readers.8 Clearly one of the

most popular books of the period, the Narrative can

still exercise its morbid fascination on

the modern reader.

One attraction of the book obviously

lies in its description of human beings under-

going extreme suffering without entirely

losing their spirit. Equally interesting is the

picture Riley offers of a completely

alien society which observed apparently barbarous

customs, lacked law and order, and was

obsessed by rigid social stratifications based

on religious prejudice. Yet the Narrative

also had a special relevance for Riley's

contemporaries because of the view it

offered of slavery "from the bottom up"; his

story enabled white men to empathize

with the lot of the slave, while it alarmingly

revealed that even white men might be

enslaved by an enemy who had the will and

power to do so. This was a lesson which

some writers claim was not lost upon

Abraham Lincoln, who read the book as a

youth in Indiana and who certainly later

warned that slavery in America could

threaten the liberty of white men.9 Riley him-

4. J. Riley, Narrative (1829),

21-159, 224-261. The ransom figure is also given as totaling

$1,852.45. Ibid., 110, 260.

5. Riley's story was believed at the

time by intelligent men who knew the surrounding circum-

stances at first hand. His published

account included several letters from participants who

corroborated the story. J. Riley, Narrative

(1829 ed.), iii, v-vi, xi-xiv, 260; J. Riley, Narrative

(Hartford, Conn., 1817),

"Postscript," 449-460, xi-xxiii; W. W. Riley, Sequel, 343-366,

434.

6. Harriet A. Weed, ed., Autobiography

of Thurlow Weed (Boston, 1883), 57-58; J. Riley,

Narrative (1829), v. Weed, later renowned as a New York

politician, was at the time working

for the publisher, William A. Mercien. See

also William Coyle, ed., Ohio Authors and Their

Books, 1796-1950 (Cleveland, 1962), 531-532, which, however, contains

some inaccuracies.

7. For references to others suffering a

similar plight, see J. Riley, Narrative (1829), 111-112,

156-157, 268-270; W. W. Riley, Sequel,

v, 291, 356, 362.

8. J. Riley, Narrative (1829),

xi; W. Riley, Sequel, iv-v, 326-327; Ralph R. Shaw and

Richard H. Shoemaker, American

Bibliography: A Preliminary Checklist for 1816, 1817, 1818

(New York, 1963); R. H. Shoemaker, A

Checklist of American Imprints for 1820 (New York,

1964). The Chillicothe edition was

advertised for subscription in Scioto Gazette, July 9, 1819.

Later American editions appeared in

1823, 1828, 1829, 1833, 1839, 1842, 1844, 1846, 1847, 1850,

1859, and perhaps at other times.

9. R. Gerald McMurty, "The

Influence of Riley's Narrative upon Abraham Lincoln," Indiana

Magazine of History, XXX (1934), 133-138; Louis A. Warren, Lincoln's

Youth: Indiana Years,

1816-1830 (Indianapolis, 1959), 109-111; Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham

Lincoln, A Biography

(New York, 1952), 147.

80

OHIO HISTORY

self spelled out the antislavery

implication of his book and announced his own devo-

tion to the antislavery cause:

Adversity has taught me some noble

lessons: I have now learned to look with compassion

on my enslaved and oppressed

fellow-creatures; I will exert all my remaining faculties in

endeavours to redeem the enslaved, and

to shiver in pieces the rod of oppression; and I

trust I shall be aided in that holy work

by every good and every pious, free, and high-

minded citizen in the community, and by

the friends of mankind throughout the civilized

world.10

Accordingly Riley's years in Ohio were

marked by several efforts to strike blows at

slavery, and the nature of these efforts

is very revealing of the general character of

popular antislavery sentiment at that

time.

In Ohio, public opinion was already in

some measure in tune with Riley's outlook;

indeed, by 1819 antislavery sentiment

was much stronger than is commonly ap-

preciated. In the Quaker dominated

communities of eastern Ohio there was a com-

mitted abolition movement led by Charles

Osborn and Benjamin Lundy. This move-

ment, organized in 1816 as the Union

Humane Society, openly denounced slavery,

advocated gradual emancipation,

agitiated for the repeal of the Black Laws, and

opposed schemes for colonizing freed

blacks abroad. Vigorous antislavery senti-

ments were also voiced by Presbyterians

in the southern counties, as well as by some

other congregations.11 Most Ohioans, however, showed little concern

over slavery,

for it did not appear, at this time, to

involve them very closely. Yet, whenever an

occasion arose necessitating an

expression of public opinion on slavery, that opinion

was always adverse to the institution.

In 1818 when a number of citizens petitioned

the General Assembly to promote the

gradual abolition of slavery and the coloni-

zation of the freedmen, the legislature

promptly obliged by passing, with little debate,

cursory resolutions calling on Ohio's

Senators and Representatives in Congress "to

use their best endeavors to procure the

passage of a law which will effect the purposes

aforesaid."12 No

politician, in fact, wished to be branded as favoring the institution.

In 1816 when a candidate for Congress in

the Cincinnati district was charged with,

among other things, being "a friend

to slavery," his supporters clearly felt this accusa-

tion to be potentially damaging and

carefully refuted the charge before considering

the others.13 Even more

significant was the way in which proposals to revise the state

constitution were resisted in 1817,

1818, and 1819 by those who feared the possible

introduction of slavery into Ohio.

Informed opinion in general believed that:

10. J. Riley, Narrative (1829),

261.

11. Richard F. O'Dell, "The Early

Antislavery Movement in Ohio," (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Michigan,

1948), 179-225, 294-300; William Birney, James G. Birney

and His Times (New

York, 1890), 163-171, 390-391, 431-435. For the early abolition movement

in eastern Ohio, see also Randall

M. Miller, "The Union Humane Society: A Quaker-Gradualist

Antislavery Society in Early Ohio,"

Quaker History (forthcoming); Ruth A. Ketring [Nuerm-

berger], Charles Osborn in the

Antislavery Movement (Columbus, 1937), 34-40; and Merton

L. Dillon, Benjamin Lundy and the

Struggle for Negro Freedom (Urbana, Ill., 1966), 7-36. The

work most notable for its failure to

recognize the strength of antislavery feeling in the North by

1819 is Glover Moore, The Missouri

Controversy, 1819-1821 (Lexington, Ky., 1953).

12. Ohio, Senate Journal, 1818, p.

103, 109, 131, 133, 138, 143, and House Journal, 1818, p.

395.

13. "To the Electors of the First

Congressional District," Cincinnati, October 1, 1816, political

broadside, Ohio Historical Society. The candidate was a

future President, William Henry Harri-

son.

James Riley 81

Such fears are groundless. The aversion

to slavery is deeprooted and universal. If there

should be some individuals who would

wish to introduce a slave population among us,

they are few in number, and the

sentiments of the people are so decidedly hostile to it, that

the bare suggestion of the idea would

forever ruin their influence.

Despite such reassurances, the call for

a state constitutional convention was de-

feated by popular referendium in 1819,

apparently because of the persistence of

the rumor.14

However motivated or justified, this

general agreement in Ohio that slavery was an

evil institution indicated most Ohioans

would oppose any suggestion for the United

States government to countenance the

expansion of slavery within the country. In

1818 when Missouri applied for admission

to statehood with a constitution which

protected slavery, the people of the

northern states were in effect being asked, for

the first time in a decade, to

participate in a national decision concerning slavery. In

Ohio public opinion strongly opposed the

admission of a slave state from the new

lands of the Louisiana Purchase, and by

December 1819 this opposition was being

forcefully expressed through the press

and public meetings.15 One young Ohio poli-

tician urged his Congressman and law

partner to take a firm stance against the ex-

tension of slavery, if only to

strengthen himself among the people: "the question with

regard to our own Constitution aroused

them, and no detail of the [Missouri] question

will now pass them unheeded."16

Amidst the clamor James Riley made his

own contribution to the anti-Missouri

cause. Among other things, he attempted

to prod the Ohio General Assembly into

action by persuading Governor Ethan

Allen Brown to raise the question before the

legislature. In the following letter

which he sent to Brown, Riley mobilized the power-

ful antislavery arguments and the great

emotional force which he had previously

displayed in his Narrative.17

Zanesville, Decr. 24th 1819.

Sir

In traversing much of the central

part of this state and conversing with the most

intelligent & thinking part of

the community, it is with the utmost satisfaction I find

in every quarter sentiments according

with my own on the subject of the extention of

slavery westward of the Mississippi

River particularly in the now territory of Missouri.

On this question there appears to be

no difference of opinion all wishing to prevent by

all the means in their power the

further extention of that crying Evil alike inhuman

14. Liberty Hall and Cincinnati Gazette, November 10, 1817;

committee report, January 17,

1818, Ohio, House Journal, 1818 p.

294; Scioto Gazette (Chillicothe), June 11, 1819, and The

Supporter (Chillicothe), June 16, 1819. See also O'Dell, "Early

Antislavery Movement," 228-229;

William T. Utter, The Frontier State,

1803-1825 (Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the State of

Ohio, II, Columbus, 1942), 327-328.

15. Howard Horton to M. T. Williams, et

al., December 31, 1819, Micajah T. Williams Papers,

State Library of Ohio; Cleaveland

Herald, December 14, 1819; Liberty Hall and Cincinnati

Gazette, December 21, 1819; Moore, Missouri Controversy, 80-81,

204-207, 324-325; O'Dell,

"Early Antislavery Movement,"

258-260.

16. Thomas Ewing to Philemon Beecher,

January 1, 1820, quoted in Paul I. Miller, "Thomas

Ewing, Last of the Whigs"

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, 1933), 35-36.

17. James Riley to Governor Brown,

December 24, 1819. Ethan Allen Brown Papers, Ohio

Historical Society. For another

discussion of the letter, see John S. Still, "The Life of Ethan

Alien Brown, Governor of Ohio"

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State University, 1951),

141-144.

82 OHIO HISTORY

and disgraceful in a country like

ours--Boasting (& justly too,) of the purity & ex-

cellency of our moral and Political

institutions.

Impressed with the importance of the

crisis (the admission of Missouri into the

Union as a state where slavery will

be tolerated and thus entail not only on that state

but on the widely spread regions west

of the Mississippi eternal slavery,) the inhabi-

tants of this Town and County

[Zanesville and Muskingum] have agreed to meet,

and express by resolutions, memorial,

or otherwise their detestation of the principle

& practice of enslaving mankind,

& their abhorrence of the attempt now making at

Washington to extend & perpetuate

this (in a free country) abominable enormity.

When the subject of slavery is

brought forward--every nerve & sinew about my

frame is strangely affected, the

blood thrills quickly through my heart to the extremi-

ties, my former sufferings among

barbarians, rushes across my mind like a torrent,

my whole body is agitated in a

powerfull manner, the situation of my late mate &

shipmates who if living are still

groaning in wretchedness & slavery in Africa are

presented to my minds-eye smarting

under the wounds inflicted by their cruel owners,

naked, shrivelled, bleeding, bereft

even of hope, and expiring amidst the greatest

tortures, and agonies indescribable,

the bare recital of which will arouse every citizen

to exertions by which his countrymen

may be redeemed & restored to liberty & the

comforts of civilized society &

the Bosom of their disconsolate families.18 overcome

by this crowd of sensations which

torment me almost incessantly, I endeavour to

shake them off by sleep, or laborious

employment, but all in vain; if sleeping, my

agonized soul is harrowed up by

phantoms,--fancying myself in my own country,

sometimes, after having endured every

pang that could be inflicted by barbarian

cruelty & religious intolerance

and bigotry, I thank my God I am in a Christian Land

--where all enjoy freedom &

religious toleration[.] In the midst of these gratifying

reflections I am suddenly transported

to the Banks of the Mississippi where I behold

hundreds of Black Slaves--who have

been snatched & torn from their native country

by CHRISTIAN CUPIDITY & where

they are doomed with their posterity to per-

petual slavery--by professors too of

moral & political freedom & christian benevo-

lence, charity, humanity and every

virtue that adorns or ought to adorn the christian

character.19

These Black Slaves are driven by

white men with whips to their labour daily, are

forced to finish the task appointed

them--dragging along a frame just mangled by

the whip & still bleeding,

exposed, naked or nearly so, to the inclemency of the sea-

sons--fed with a peck of dried indian

corn and a pint of salt only per week, without

even a bite of flesh or fish &

forced to eat their corn raw or employ a portion of the

time allotted them for sleep in

boiling it. at the break of day they are aroused & then

horrid to relate, all those whom a

mercinary overseer or driver imagines have not

done their task the preceding day are

stretched with their faces to the ground their

arms & legs lashed fast to posts

driven into the earth for the purpose. when they

receive, on their naked backs &

posteriors, as many lashes as these merciless demons

18. Two of the six shipmates who had

been separated from Riley in the desert had been

ransomed by Willshire and the American

consul at Tangier in 1817. Nothing more was ever

heard of the other four, including the

mate, despite the efforts of Willshire and his consular

colleagues and the provision by the

United States government of money to ransom them with.

J. Riley, Narrative (Hartford,

1817), "Postscript," 449-455, xi-xxiii; W. W. Riley, Sequel, 38,

44, 334, 341, 356, 362, 384-385; J.

Riley to Watson, 44.

19. This paragraph is reminiscent of a

more disciplined passage in J. Riley, Narrative (1829),

260-261.

James Riley 83

see fit to order, from a whip that

takes out a piece of skin & of flesh at every stroke

& then in order to encrease their

torment, these worst of monsters cause STRONG

BRINE to be poured into their

bleeding wounds. This is the oil & the wine afforded to

assuage their anguish.

From daybreak in the morning untill

9, 10, or 11 o clock still--the whip is heard

to crack on these devoted victims all

along the settled parts of Louisiana & Mississippi

& the agonising shrieks of

tortured negroes fills the air with appalling outcries, which

however, is relished by many a slave

holder overseer and driver, as the sweetest

musick[sic]. Not alone in Louisianna

& Mississippi are these enormities practised--

they extend to Georgia, the

Carolinas, & the seabord[sic] of Virginia & Maryland--

And this is but a faint description

of what my eyes have beheld--thus tortured many

expire even while receiving their

punishment and crying out to their masters & our

common Parent for mercy &

protection; others literally cut to pieces groan a few days

in agony & expire, nor does the

inhuman perpetrator receive any punishment for

this demonlike butchery.20

It is high time that the inhabitants

of the non slave holding states should rise in

their strength & put a stop to

the further extention of these accursed practices that

continue to blacken the American

character. Every citizen every free & virtuous man

is interested in this thing, &

when the whining pretended Christian HYPOCRITES

in Missouri come solemnly forward

under the garb of sanctity as a religious society,

and resolve that it is expedient

& proper to admit the Principle & practice of slavery

in that State & its constitution,21

the indignation of every virtuous mind should, in

my opinion, teach them that men

though covered with a black skin are not brutes

& that the hypocritical advocate

of slavery shall be detested by all mankind.

I cherish a hope, therefore, that

your Excellency as the chief magistrate of this

great & powerful as well as free

state will cause the subject to be brought before the

Enlightened Legislative Bodies now in

session at Columbus, and that (according with

me in principle) you will feel it a

duty to do all in your power to arrest in any way

that your better Judgment shall

dictate, the extension of slavery beyond the Missis-

sippi River.

Please excuse the length & hasty

manner of this communication.

And I have the Honour to be with

distinguished regard & great considerations of

respect & esteem

Your Excellencys most humble &

most devoted servant

James Riley

Ethan A. Brown

Governor of Ohio

P.S. I shall set out tomorrow for the

seat of the General Government where I expect

20. Riley is, of course,

overgeneralizing. The treatment of the slaves was usually rather better

than he portrays, yet there can be no

doubt that on occasions cruelties similar to those he de-

scribes did occur, and much more

frequently than southerners cared to admit. For a scholarly

account of the treatment of the slaves, see

Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution (New

York, 1956). Riley had visited the Deep

South on his voyages to New Orleans and he had be-

come acquainted with the Upper South

during his stay in Washington, 1816-1818. J. Riley,

Narrative (1829), 17-20, 261; W. W. Riley, Sequel, 17-18.

21. For another reference to religious

support in Missouri for the maintenance of slavery

there, see Annals of Congress, 16

Cong., 1 Sess., 848.

84

OHIO HISTORY

to remain a few weeks & where I

should be thankful to receive from you such

sentiments on this or any other

subject as your excellency may think proper to

communicate22

and am as before JR

As Riley wished, the General Assembly

took up the Missouri question in the fol-

lowing month, though without any formal

prompting from Governor Brown. The

debates on the question revealed,

however, that the issue was far more complex than

Riley had assumed. For there was a

subtle difference between preventing the "further

extention" of slavery and opposing

the admission of Missouri "as a state where

slavery will be tolerated"--a

distinction which arose simply because slavery already

existed in the territory of Missouri.23

When a majority of members of the Ohio

senate advocated that Congress should

refuse to permit (or "admit") the legal exist-

ence of slavery in Missouri, they were

in effect trying to compel that territory, as the

price of statehood, to emancipate or at

least remove the slaves already there. The

majority of members of the Ohio house,

on the other hand, wanted to oppose only

"the further extension of

slavery." The reporter of the Scioto Gazette interpreted

this as "tacitly allowing the

territories now holding slaves to retain them."24 Since

neither house would accede to the

other's position, a joint committee had to hammer

out a compromise resolution. This passed

both houses with virtually no opposition.

As finally worded, the resolution called

on Ohio's representatives in Congress "to use

their utmost exertions to prevent the

admission or introduction of slavery into any of

the territories of the United States,

and any new state that may hereafter be admitted

into the Union."25

This wording, of course, was ambigious,

and the interpretation of its meaning was

left to the Ohio Congressmen and

Senators. Did "admission" have the sense it had

possessed in the senate draft--the sense

of "permission"? In that case they must

press for some scheme of emancipation in

Missouri, such as that which four of them

22. No reply from the governor has been

discovered. The purpose of Riley's trip to Washing-

ton was to lobby for an appointment as

Register or Receiver of the public moneys in one of the

new land offices in Ohio. Riley failed

in this application, as he did also in a later application for

the Indian Agency at Fort Wayne. W. W.

Riley, Sequel, 20, 23-24, 159-164.

23. In 1820 there were over 10,000

slaves in Missouri, nearly one-sixth of the total popula-

tion. Fourth Census of the United

States, 1820 (Washington, 1821).

24. Scioto Gazette (Chillicothe),

January 14, 1820; Ohio, Senate Journal, 1820, pp. 136-138,

145-147 and House Journal, 1820, pp.

161-164.

25. Ohio, Senate Journal, 1820, pp.

145-147, 154, 169; House Journal, 1820, p. 166, 176,

198-199. The leading secondary

authorities are wrong or misleading in their interpretation of this

significant episode. Moore, Missouri

Controversy, 205; O'Dell, "Early Antislavery Movement,"

260-262. In view of the disagreements

between the two houses, there cannot be said to have

been general unanimity, nor was the

debate merely over wording, since at least one contemporary

observer perceived real differences of

principle between the two houses. Scioto Gazette (Chillico-

the), January 14, 1820. The house proposal

contained the more strongly worded preamble, but the

demands in the resolutions it proposed

were much less extreme in effect. The amendment, moved

abortively by W. H. Harrison in the

senate, was not intended primarily to extend the principle of

restriction to the whole West, but to

provide a loophole by raising doubts as to the constitutional

power of Congress to restrict slavery in

this case. See Dorothy B. Goebel, William Henry Harri-

son, A Political Biography (Indianapolis, 1926), 232-233. There was little

disagreement on ex-

tending the proposed restriction to all

the territories. Western Herald and Steubenville Gazette,

January 29, 1820.

James Riley

85

had voted for and four had opposed in

the previous session.26 If, on the other hand,

"admission" was merely a rough

synonym for "introduction" (as, in its verb form,

the word is used later in the same

sentence), then it would be possible for the state's

Representatives to vote for Missouri's

statehood on condition that no more slaves

were to be introduced into the state. In

the course of the debates the legislators from

Ohio joined with other northerners in

adopting this latter, more moderate position.

By January 1820 the free-state members

of Congress were demanding only that the

"further introduction" of

slaves into Missouri be prohibited. As Ohioan William A.

Trimble pointed out in the United States

Senate, there was nothing in such a restric-

tion that interfered with any property

already in Missouri.27 Historians have all too

often overlooked this willingness on the

part of northerners to accept Missouri as a

slave state in 1820, on condition only

that the further importation of slaves was

banned.28

The South, however, refused to accept

even this more moderate proposal. With

the aid of a handful of northerners,

just sufficient to provide a majority in both

houses of Congress, southerners gained

the admission of Missouri without any restric-

tion on slavery whatsoever, though they

conceded the prohibition of slavery in the re-

maining lands of the Louisiana Purchase

north of 36°30'. The Ohio delegation in Con-

gress unanimously opposed the admission

of Missouri on these terms, even as part of

a compromise, thereby gaining the

applause of most of their constituents at home.29

The South, by its recalcitrance, had

made it possible for Ohioans to unite behind the

vague sentiment expressed in the 1820

resolutions that slavery was "a national

calamity, as well as a great moral and

political evil," and ought not to be allowed to

expand. Ohioans were thereby saved from

having to decide how far to carry their

antislavery principles, and a breach was

prevented between those who were more

ready to compromise with slavery where

it already existed, and those who were willing

to demand a retraction of slavery from

the limits it had already reached west of the

Mississippi.

It is doubtful whether James Riley would

have objected to the triumph of moderate

26. The vote in question had been on the

second clause of the Tallmadge amendment of 1819,

which had provided for the emancipation,

at the age of twenty-five, of all children born of slaves

in Missouri after the admission of the

state. The first clause, which prohibited the further intro-

duction of slavery into Missouri, had

been unanimously supported by the Ohio delegation in

1819. Moore, Missouri Controversy, 52-53,

55, 61; Annals of Congress, 15 Cong., 2 Sess. 1214-15.

27. Ibid., 16 Cong., 1 Sess.,

290. For Senator Trimble's willingness to compromise in spite

of his dislike of slavery, see Trimble

to Brown, January 29, 1820. Brown Papers.

28. Glover Moore, Missouri Controversy,

fails to mention this basic shift in the North's bar-

gaining position (cf. 86, 89-90,

100), while George Dangerfield claims that in 1820 the North

had moved to a more extreme position

than that of the Tallmadge amendment and was now

demanding that all children subsequently

born of slaves should be free at birth. George Danger-

field, The Era of Good Feelings (New

York, 1963), 220, 464, and Dangerfield, The Awakening of

American Nationalism (New York, 1965), 122-123. In fact the Roberts

amendment in the

Senate prohibited only "the further

introduction" of slaves, while the Taylor amendment in the

House made no mention of children or

emancipation and specifically stated that the amendment

"shall not be construed to alter

the condition or civil rights of any person now held to service

or labor in the said Territory." Annals

of Congress, 16 Cong., 1 Sess., 119, 359, 802, 947, 1540.

The point is correctly made, though not

emphasized, in the good account of the debates from the

Ohio point of view in O'Dell,

"Early Antislavery Movement," 262-269. The position adopted

by the North in 1820 in effect involved

accepting the ultimate admission of Arkansas as a slave

state.

29. Scioto Gazette (Chillicothe),

March 16, 1820; Western Herald and Steubenville Gazette,

March 11, April 22, 1820; Moore, Missouri

Controversy, 100, 108, 144, 145, 156, 158, 205.

86 OHIO HISTORY

counsels in the Ohio legislature and

within the Ohio congressional delegation, for he

always demonstrated a great respect for

property rights and expressed real concern

about the dangerous consequences of

releasing slaves in large numbers. In the 1830's

he was to be very sarcastic about the

philanthrophy of the British government which,

in his view, irresponsibly freed the

slaves in the British West Indies while being

isolated by distance from the effects of

emancipation.30 Riley's awareness of the

dangers of abolition accordingly meant

that his antislavery opinions were always

qualified by reservations. At the very

climax of his peroration against slavery in

his Narrative, he had written:

I am far from being of opinion that they

[the slaves] should all be emancipated immedi-

ately, and at once. I am aware that such

a measure would not only prove ruinous to great

numbers of my fellow-citizens, who are

at present slave holders, and to whom this species

of property descended as an inheritance;

but that it would also turn loose upon the face of

a free and happy country, a race of men

incapable of exercising the necessary occupations

of civilized life, in such a manner as

to ensure to themselves an honest and comfortable

subsistence; yet it is my earnest desire

that such a plan should be devised, founded on the

firm basis and the eternal principles of

justice and humanity, and developed and enforced

by the general government, as will

gradually, but not less effectually, wither and extirpate

the accursed tree of slavery, that has

been suffered to take such deep root in our otherwise

highly-favoured soil: while, at the same

time, it shall put it out of the power of either the

bond or the released slaves, or their

posterity, ever to endanger our present or future

domestic peace or political

tranquillity.31

This belief in the inferiority and

undesirability of the Negro was typical of the

racial prejudice generally prevalent in

Riley's day. Throughout the North free

Negroes were treated as inferior and

suffered under legal disabilities. In Ohio the

constitution of 1802 and the Black Laws

of 1804 and 1807 had established a code of

discrimination which was designed to

ensure the subordination of Negro inhabitants

and to discourage further black

immigration.32 When several hundred slaves in Vir-

ginia belonging to an Englishman, Samuel

Gist, were freed and settled in Brown

County in 1819, there were voluble

protests against the introduction of a "depraved

and ignorant . . . set of people"

into Ohio. Though they received some charitable

assistance from the Quakers, these black

settlers were ostracized and even persecuted

by their neighbors.33 What is

more, even the opposition to the extension of slavery,

whether into Ohio or into new states

like Missouri, was based not only on moral and

political objections to slavery as an

institution, but also on the belief that the extension

or introduction of "a slave

population" was "fraught with the most fearful conse-

quences." This phrase, "a

slave population," can reasonably be interpreted to mean

30. W. W. Riley, Sequel, 183,

186.

31. J. Riley, Narrative (1829),

261.

32. Samuel P. Chase, The Statutes of

Ohio and the Northwestern Territory (Cincinnati, 1833-

35), 378, 393-394, 556-557; O'Dell,

"Early Antislavery Movement," 146-155, 230-232; and the

pioneer but unreliable study, Frank U.

Quillin, The Color Line in Ohio: A History of Racial

Prejudice in a Typical Northern State

(New York, 1913), 1-36. For the North

in general, see

Leon F. Litwack, North of Slavery:

The Negro in the Free States, 1790-1860 (Chicago, 1961).

33. Western Herald and Steubenville

Gazette, July 3, 1819, March 25, 1820; The History of

Brown County, Ohio (Chicago, 1883), 591-592; O'Dell, "Early Antislavery

Movement," 156-159,

223-224; Miller, "Union Humane

Society." The most accurate figure for the number of black

settlers appears to be about 300.

James Riley 87

that the sort of people who were slaves

was being objected to rather than the fact

that they were slaves.34

In comparison with many contemporary

expressions of prejudice, Riley was rela-

tively liberal in his attitude to

Negroes, as indeed, his letter to Governor Brown sug-

gests. On one occasion during his

captivity in Africa, his colleagues had been most

aggrieved when a Negro slave, with the

approval of their Arab masters, treated the

Americans as being racially inferior.

Riley, however, perceived that this was a natural

human reaction for a person in the

Negro's situation.35 Even more revealing is the

fact that, when the Ohio House of

Representatives debated in 1824 a new bill "to

regulate black and mulatto

persons," Riley was one of the handful of members who

supported an amendment exempting from

the operation of this Black Law "any

negro or mulatto emigrating to this

state from a state in which negroes and mulattoes

are allowed the privileges of

citizens."36 Yet, liberal as this attitude was compared

with that of the majority of Ohio

legislators, Riley still believed that, if the slaves were

freed, they could not be allowed to

remain in America.

Combining practicality with

humanitarism, Riley considered it entirely possible

to devise a means of abolishing slavery

"without endangering the public safety, or

even causing the least injury to individual

interest."37 A scheme which apparently

fitted his requirements had been

advocated since 1816 by the American Colonization

Society. This movement planned to raise

enough money to buy slaves at the market

price, free them and then send them to a

colony in Africa; the colonizationists also

hoped that the possibility of

repatriation would encourage voluntary manumissions,

while the colony would have a civilizing

influence on Africa and would help to under-

mine the persistent, though outlawed,

transatlantic slave trade. Presumably these

proposals were the ones to which the

Ohio General Assembly had given its moral

support in 1818. In the following

session Congress passed a Slave Trade act, the

terms of which President Monroe

interpreted as authorizing him to assist the coloni-

zationists in founding the colony in

West Africa which was soon to be called Liberia.

Although the prospects of this colony

seemed far from promising by the end of 1823,

the Ohio General Assembly of which James

Riley was a member proposed that the

nation take advantage of the

colonizationists' initiative in order to bring about the

ultimate abolition of slavery.38 Resolutions

were passed which went far beyond the

gesture of 1818, for these resolutions

offered for national discussion a specific and

apparently practicable scheme for

emancipation. The Assembly, presumably with

Riley's support, proposed that the

general government, with the consent of the slave-

holding states, should pass a law

providing "that all children of persons now held in

34. Liberty Hall and Cincinnati

Gazette, November 10, 1817, December 21, 1819. The argu-

ment that anti-Negro prejudice lay

behind hostility to the extension of slavery is forcefully ex-

pressed in Eugene H. Berwanger, The

Frontier Against Slavery: Western Anti-Negro Prejudice

and the Slavery Extension Controversy

(Urbana, Ill., 1967), which, however,

pays almost no

attention to the Missouri crisis. It is

important that the moral, religious, and political objections

to slavery, for example as expressed in

Riley's letter to Brown, should not be overlooked or their

power underestimated.

35. J. Riley, Narrative (1829),

57-58.

36. Ohio, House Journal, 1824, p.

366. The amendment failed by 10 votes to 55.

37. J. Riley, Narrative (1829),

261.

38. Philip J. Staudenraus, The

African Colonization Movement, 1816-1865 (New York,

1961), 1-93, 170; O'Dell, "Early

Antislavery Movement," 290-294, 298-305. The debates in the

Senate reveal that the members were well

aware of the Liberian experiment. Columbus Gazette,

January 22, 1824.

88 OHIO HISTORY

slavery, born after the passage of such

law, should be free at the age of twentyone

years"--on condition that they then

consented to be transported abroad to a foreign

colony. The "duties and

burthens" of the scheme, meaning primarily its expense,

were to be borne by all the states in

the Union, "upon the principle that the evil

of slavery is a national one."

These statesmanlike and conservative proposals were

then forwarded, on the legislature's

instruction, both to Ohio's representatives in

Congress and to all the other states for

their consideration.39

In making emigration a condition of

emancipation, the Ohio General Assembly

was ensuring that the immediate result

of emancipation would not be an increase in

Negro immigration into Ohio. As if to

emphasize the point, the same Assembly

considered establishing new measures

"to regulate blacks and mulattoes." Although

this bill failed in the senate after

passage in the house, the original Black Laws were

ordered to be reprinted among the acts

of the session.40 Yet this desire to rid the

country of the freedmen did not mean

that the resolutions of 1824 were in any way

a less genuine expression of a desire to

abolish slavery. It is true that in the debates

on the resolutions the rapid increase in

the numbers of "these people" was declared

to be one of the evils which slavery

entailed on the United States, but on the whole

the debaters were much more concerned

about destroying a pernicious institution

than about removing an unwanted race.41

Compulsory repatriation was accepted

at the time as being the only way of

procuring a national agreement on emancipation;

colonization was viewed not as an end in

itself, but as an acceptable means of achiev-

ing a higher end. In fact, down to the

mid 1830's many of the most ardent anti-

slavery men in Ohio, including some who

were or later became abolitionists, con-

tinued to embrace colonization as a

legitimate and morally acceptable means of bring-

ing about ultimate abolition.42 In

this context, the Ohio resolutions of 1824 must be

seen as designed primarily to achieve

what the authors and their contemporaries said

was the object--to "effect the

entire emancipation of the slaves in our country,

without any violation of the national

compact, or infringement of the rights of

individuals."43

Apparently the passage of the

resolutions in January 1824 served an immediate

political purpose for Ohio politicians.

At that time great interest centered on the

coming Presidential election. For the

first time since Ohio had become a state, there

was no general agreement within the

Republican party as to its national candidate,

and Ohioans were particularly concerned

that the victor should be a man who satis-

39. Ohio, House Journal, 1824, pp.

80-81, 170-171, 196, 213; Senate Journal, 1824, pp. 156-

157. The evidence of proceedings in the

house is too scanty to reveal whether or not Riley ad-

vocated and supported these proposals; however, no opposition

to them was recorded in the house.

40. Ohio, House Journal, 1824, p. 168, 175, 340, 359-360, 366-367, 412; Senate

Journal, 1824,

p. 293, 295, 322; Laws of Ohio, XXII,

335-337.

41. Columbus Gazette, December

18, 1823; January 22, 1824.

42. For example, Thomas Morris, David

Smith, James H. Purdy, and even Benjamin Lundy.

Ohio, Senate Journal, 1832, pp.

401-404; B. F. Morris, The Life of Thomas Morris . .. (Cin-

cinnati, 1856); Ohio Monitor (Columbus),

October 30, 1824, May 26, 1830, March 20, May 26,

1833; Xenia Free Press, February

4, 11, June 2, 1832, October 26, 1833; Dillon, Benjamin Lundy,

24, 27-30, 57, 130. Most recent

historians agree that, at least initially, a legitimate and morally

principled antislavery sentiment lay

behind northern support for colonization. Staudenraus,

African Colonization Movement; O'Dell, "Early Antislavery Movement,"

292-293, 298, 315, 354;

Merton L. Dillon, "The Antislavery

Movement in Illinois, 1824-1835," Journal of the Illinois

State Historical Society, XLVII (1954), 149-166.

43. Ohio, House Journal, 1824, p.

171.

James Riley 89

fled the sectional interests of the Old

Northwest. Accordingly many political leaders

advocated the claims of Henry Clay, the

undoubted champion of the "western in-

terest" and its demand for internal

improvements and a protective tariff. However,

the movement in favor of this Kentucky

slaveowner met with strong resistance, and,

in the state legislative session of

1822-23, many politicians refused to commit

themselves to Clay's cause. The

indications are that they were afraid if they sup-

ported Clay the cry "No

Slavery!" would be used against them by local rivals who

preferred a non-slaveholding

candidate.44 By the end of 1823, though, it was be-

coming clear that there was no

non-slaveholding candidate in the field who both

stood a chance of national success and

was favorable to the "western interest." Hence

many politicians felt that there was no

alternative but to support the leading western

candidate, even if he was tainted by

slavery. Despite the lack of direct evidence, it

seems reasonable to argue that, in those

circumstances, the emancipation and coloni-

zation resolutions of 1824 offered to

many Ohio politicians the opportunity to demon-

strate to their constituents that they

were sound on slavery, even if they did support

a slaveholder for the Presidency.

In the end, three out of every four

Ohioans who voted in the Presidential election

agreed to prefer a western candidate who

happened to be a slaveholder, be it Jackson

or Clay, rather than sacrifice their

economic interests as westerners. Even so, anti-

slavery sentiment probably still

influenced the election returns just as it had earlier

embarrassed the maneuverings of the

politicians. Those who were most concerned

about the influence of slavery in the

nation refused to vote for a southerner. James

Riley himself, after the close of the

Assembly in February 1824, rode around Ohio

advocating the claims of John Quincy

Adams, the one remaining northern candidate;

and in November a large proportion of

Riley's fellow settlers from New England and

most of the Quakers voted for Adams,

even though his views on economic policy at

that time were considered hostile to

western interests. In this way the popular con-

cern over slavery in the early 1820's

not only helped to produce the emancipation

resolutions of 1824, but also influenced

the early formation of national political

parties in Ohio.45

The existence of a widespread popular

concern over slavery at this period must be

ascribed in large measure to the

educative effect of the Missouri crisis. Benjamin

Lundy believed that the controversy, by

revealing that slavery, far from dying of its

own accord, was actually growing with

menacing vigor, had stimulated awareness of

the problem and made many people

receptive to antislavery ideas; hence he was en-

couraged to begin publication in Mount

Pleasant in 1821 of his newspaper, The

Genius of Universal Emancipation.46

Another sign of the desire to

behave consistently

with the principles expressed during the

crisis, and even to strike back at the trium-

phant slave interest, was the refusal,

from 1820 on, of some newspapers in eastern

44. Donald J. Ratcliffe, "The Role

of Voters and Issues in Party Formation: Ohio, 1824,"

Journal of American History (forthcoming). In Wayne County one Ohio politician

carefully

noted for future reference that a local

rival had defended the caucus nomination of Clay by the

Ohio legislature in January 1823 and had

said that "he would not care if slavery was admitted

in all or every state in the Union . . .

if the majority wished it." Memorandum, in the hand-

writing of Joseph H. Larwill, July 12,

1823, Larwill Family Papers, Ohio Historical Society.

45. Ratcliffe, "Voters and Issues

in Party Formation: Ohio, 1824." For Riley's canvassing in

1824, see "Reminiscences by

W. Willshire Riley," 249.

46. Dillon, Benjamin Lundy, 40-41.

90 OHIO HISTORY

Ohio to print fugitive slave

advertisements.47 As for the widespread reluctance to

support Henry Clay for the Presidency in

1822 and 1823, many Ohio politicians

ascribed this opposition to the fact

that "the country has not so soon recovered from

the Missouri question." Clay was

considered reprehensible by many people not just

because he was a slave-owner, but also

because he was widely regarded as the archi-

tect of the Missouri compromises and

therefore was held responsible for the ex-

tension of slavery into the Louisiana

Purchase.48 Similarly, the legislative committee

which drafted the emancipation

resolutions of 1824 pointed in justification to the

lesson of the Missouri crisis. The

preamble which they proposed for the resolution

openly declared that "the curse of

slavery . . . is gradually spreading its evils over

the face of our country, menacing

jeopardy to our happy institutions, and threatening

at some future day, and that day not far

distant, to involve in one common ruin the

non slaveholding with the slaveholding

part of the community .. ." This growing

menace made it necessary for "those

evils" to be "averted by timely and efficient

means."49 What form the

threatened ruin would take was not stated, but clearly one

obvious danger was a dissolution of the

Union and even a civil war, such as many

Ohioans, among others, had believed

possible in 1820.50

Another immediate experience also

underlay popular awareness in Ohio of the

slavery problem in the early 1820's.

Throughout these years great interest was shown

throughout the United States in the

struggles of the Greek and Latin American

peoples to throw off the rule of foreign

powers, and in December 1823 President

Monroe focused national attention on

these conflicts by his annual message to Con-

gress. On that occasion he spoke with

approval of Greece's growing success in her

struggle for independence and declared

that the United States would oppose any

attempt by the Holy Alliance to

intervene in the Americas in order to reimpose Euro-

pean rule.51 In these

critical times many Americans regarded themselves as the

champions of all peoples struggling to

be free; yet at the same time their own country

47. Western Herald and Steubenville

Gazette, May 27, July 1, August 12,

September 9, 1820;

O'Dell, "Early Antislavery

Movement," 269-274; Miller, "Union Humane Society"; Eber D.

Howe, Autobiography and Recollections

of a Pioneer Printer [Painesville, 1878], 25. There

are many signs of a general increase in

anti-slavery activity after 1820. See Alice D. Adams,

The Neglected Period of Anti-Slavery

in America, 1808-1831 (Boston, 1908),

and O'Dell,

"Early Antislavery Movement,"

355-394.

48. Edward King to Rufus King, January

23, 1823, in Charles R. King, The Life and Cor-

respondence of Rufus King (New York, 1900), VI, 497; John Sloane to Henry Clay,

October

16, 1822, in James F. Hopkins and M. W.

M. Hargreaves, eds., The Papers of Henry Clay

(Lexington, 1963), III, 294-295;

Painesville Telegraph, March 5, 1823; Western Herald and

Steubenville Gazette, March 22, 1823. See also "Clay and

Slavery!!," October 22, 1824,

political broadside, Ohio Historical

Society.

49. Ohio, House Journal, 1824, p.

170. The preamble was unanimously rejected in the senate,

not because its sentiments were

unpopular, but because it was considered "that this was not

proper language to hold, where we wish to conciliate

the feelings of those we addressed and induce

them if possible to think with us."

Columbus Gazette, January 22, 1824; Senate Journal, 1824,

p. 157.

50. Cleaveland Herald, December 14, 1819, March 21, 1820; Western Herald

and Steubenville

Gazette, February 26, March 4, 1820; Trimble to Brown, December

28, 1819, Brown Papers.

51. James D. Richardson, ed., A

Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents

(New York, 1921), II, 786-787; Columbus Gazette,

January 15, 29, 1824; Western Herald and

Steubenville Gazette, January 10, 17, 1824. Through the early 1820's Ohio

newspapers and the

letters sent from Washington by Ohio's Congressmen and

Senators contained numerous reports

of foreign affairs.

James Riley 91

maintained an institution which was the

very antithesis of liberty. As the committee

which produced the Ohio emancipation

resolutions of 1824 stated,

While we manifest to the world our

benevolent and charitable feelings in the cause of the

Greeks, the glorious triumphs of our brothers of South

America . . . and the

laudable

exertions of the devoted patriots of all

nations for freedom and self -government, we ought

not to disregard the complaints of the

sons and daughters of Africa, who, in violation of

every principle of justice and humanity,

attended with circumstances often of the most

attrocious [sic] wickedness and cruelty,

have been forced .. .to suffer with their posterity,

interminable and ignomenious [sic]

bondage in a foreign land....52

James Riley shared the general anxiety

about the fortunes of liberty throughout

the whole world. During the legislative

session of 1824 he was elected to an un-

official committee appointed to raise

money in Columbus to aid the Greeks in their

fight for independence.53 Then,

shortly after the passage of the emancipation resolu-

tions, Riley proposed in the house a

further set of resolutions which expressed Ohio's

support for Monroe's declaration of the

previous month. The Holy Alliance, Riley

said, was planning to eradicate the

principles of freedom and liberty; if these Old

World powers were allowed to intervene

in the affairs of the western hemisphere, they

would "strike at and endanger the

very foundation of our national indepen-

dence and individual liberties and

independence." When other legislators suggested

that his resolutions were superfluous

and over-grandiose, he justified his initiative on

the ground that he himself "knew

what it was to feel the effect of oppression and

tyranny, and he could therefore the

better sympathize with those who were menaced

by despotism." Riley's resolutions

passed the house, though in a simplified form,

thus further revealing the ideological

concern for political freedom which had helped

to produce the emancipation resolutions.54

Riley himself undoubtedly identified

despotism and imperialism with slavery,

and he appreciated that American concern

for the success of liberation movements

in other countries conflicted with the practice

of holding men as slaves. In a speech of

1825, at the first July Fourth celebration

held in Van Wert County, Riley hailed

the Latin American revolutions as "the

triumph of the principles contained in

our Declaration of Independence in the New

World"; yet on the same occasion he

also declared that "our glorious Declaration"

would remain unfulfilled in the United

States until "we can with truth 'proclaim

liberty throughout all the land to all

the inhabitants thereof.'"55 It was exactly this

sense of inconsistency between American

ideals and practice that Riley had previously

expressed in his writings; the force of

the point was now reemphasized in the early

1820's, for him and other Americans, by

the revival of enthusiasm for international

liberation movements on the pattern of

the American republican experiment.

Yet, however powerful the emotional and

ideological drive to do something to

promote the abolition of slavery, or at

least restrict it to its present limits, Riley's

antislavery sentiment was always closely

limited by countervailing feelings which

rendered his aspirations ineffective.

The general fear of the consequence of releasing

52. Ohio, House Journal, 1824, pp.

170-171.

53. Columbus Gazette, January 15,

29, 1824. The committee raised $500.

54. Ibid., January 22, 1824;

Ohio, House Journal, 1824, p. 221, 225-227.

55. Oration and toast, Willshire, July 4, 1825, in "Reminiscences by

W. Willshire Riley,"

250-251.

|

uncivilized Negroes on the white community convinced Riley, as he wrote in 1833, that "colonization of free colored persons offers the best, if not the only means of ridding our country of the great curse of slavery." He therefore pinned his hopes on the efforts of the American Colonization Society to found a Negro colony in Liberia, a scheme which proved quite ineffective, impractical, and far too expensive as a means of ending slavery.56 Furthermore, his practical proposals always depended on the cooperation of the South, which was never forthcoming. In 1820 the power of the South in the United States Senate ensured the extension of slavery across the Mississippi River, while Ohio's moderate emancipation and colonization proposals of 1824 were not merely rejected by the slaveholding states, but vehemently denounced and abused.57 In these circumstances Riley's antislavery zeal was doomed to futility, unless he were to adopt an outlook which was both less Negrophobe and less respect- ful of the constitutional rights and political power of the slaveholders.58 In these inhibitions to his antislavery zeal, Riley probably reflected the outlook of most northerners. Fear of the consequences seemed to cripple their desire to end slavery; they were unwilling to pay the price their ideals demanded. Most Ohioans were unwilling to press their antislavery sentiments farther than the South would allow, as both the Missouri crisis and Ohio's failure to follow up the emancipation reso- lutions of 1824 revealed. When the issue came up again in 1827-28, the General Assembly passed resolutions which made no mention of emancipation and asked only

56. J. Riley to R. R. Gurley, March 11, 1833, in W. W. Riley, Sequel, 54-56. 57. Herman V. Ames, ed., State Documents on Federal Relations, nos. 101-104 (reprint ed., New York, 1970), 203-208; Charles S. Sydnor, The Development of Southern Sectionalism, 1819-48 (Baton Rouge, 1948), 151-152; Dillon, Benjamin Lundy, 104-106; Staudenraus, African Colonization Movement, 170-171. Eight northern states approved the Ohio proposals. 58. Riley's eldest son later showed sympathy with a far more radical position than that of his father. In 1846 he bravely supported the Garrisonian abolitionist Augustus Wattles who was being persecuted and threatened with violence by his Mercer County neighbors. Young Riley wrote: the "only sins complained of, in our community," are that Wattles "feeds, clothes, assists, & teaches negroes, and refuses to vote, for locofoco, Whig, or liberty men, consequently does not do all he can, to support and sustain the government, but lets that be taken care of, by men, less intelligent, moral & intellectual than himself." J. W. Riley to Governor Mordecai Bartley, August 21, 1846, Bartley Papers, Ohio Historical Society. |

James Riley 93

for national aid for colonization; and

in 1831, after the South had protested even at

this proposal, the legislature adopted

the position that it was inexpedient to express

any opinion on the subject at all.59

At the same time as they tried to

appease the South, Ohioans also reinforced their

determination to prevent a mass influx

of freed Negroes into the state. When such an

influx began to take place after 1825,

racial prejudice and discrimination became far

more evident than before that date.

Local colonization societies, of which there had

been none before 1826, now multiplied

rapidly, and were openly justified on the

ground that they would promote the

removal of the "degraded" and "improverished"

blacks who were beginning to

"infest" the state. Stiffer enforcement of the Black

Laws was demanded and a harsh spirit of

intolerance and even persecution of blacks

now appeared, most notably in the tragic

Cincinnati race riots of 1829, 1836, and

1841.60 In many ways basic

attitudes in Ohio were similar to those of southerners,

though Ohioans were free of the extreme

fears created by living in close proximity

to black slaves. Indeed, the similarity

in attitude was fully revealed by the hostile

popular reaction in both North and South

to the "modern" abolitionists of the 1830's,

who insisted that the price of American

ideals should, indeed must, be paid. Their

proposal of immediate action in defiance

of the South and their advocacy of racial

justice and equality were so alarming

and unpalatable that many Ohioans resorted

to violence to suppress the

abolitionists. In so doing, they appeared to belie the anti-

slavery sentiment expressed in Ohio

before 1825.61

Yet one must not conclude from the

conservatism and Negrophobia of northerners

that they did not deeply hate slavery.

As a Baptist minister from Rhode Island wrote

after touring Ohio in 1842, "most

of the inhabitants of the free states agree that

Slavery is an evil, although some

difference of opinion exists concerning its abroga-

tion."62 Most Ohioans

may, after 1825, have retreated from their earlier positive

antislavery stand, and they may have

shown considerable willingness to reassure the

South that they rejected the demands of

the abolitionists. But there were still limits

to the lengths that northerners would go

in appeasing the South. When the slave states

began to insist upon more than laissez-faire

neutrality and respect for constitutional

rights, when southerners began to

require the free states to provide positive protection

for the interests of slavery and its

territorial expansion, then the basic dislike of

slavery asserted itself--as it always

did do whenever the suggestion was made that

northerners share the responsibility for

extending the South's peculiar institution. By

the mid-1850's a majority of people in

the free states had determined to concede no

more to the slave power, and the

political triumph of this antislavery stance persuaded

59. Ames, State Documents on Federal

Relations, 210-211.

60. O'Dell, "Early Antislavery

Movement," 159-165, 174-175, 305-354; Carter G. Woodson,

"The Negroes of Cincinnati Prior to

the Civil War," Journal of Negro History, I (1916), 1-16;

Berwanger, Frontier Against Slavery, 30-59;

Staudenraus, African Colonization Movement,

136-143. For typical expressions

concerning Negro immigration and colonization, see Scioto

Gazette (Chillicothe), November 3, 1825; Ohio Republican (Zanesville),

November 3, 1827;

H. Safford to Thomas Ewing, June 25,

1828. Thomas Ewing Family Papers, Library of Congress.

61. Gilbert H. Barnes, The

Antislavery Impulse, 1830-1844 (New York, 1933); Leonard L.

Richards, "Gentlemen of Property

and Standing": Anti-Abolition Mobs in Jacksonian America

(New York, 1970); for the eastern

states, Lorman Ratner, Powder Keg: Northern Opposition to

the Antislavery Movement, 1831-1840 (New York, 1968).

62. James L. Scott, A Journal of a

Missionary Tour . . (Providence, R. I., 1843), 51.

94 OHIO HISTORY

the South to secede from the Union in

1860-61 and so begin the train of events which

led to the Emancipation Proclamation and

the Thirteenth Amendment.

In this context the importance of James

Riley is clearly that he helped to reaffirm

the North's basic prejudices against

slavery. He revealed its cruelties and indignities,

demonstrated the potential menace of

slavery to white men, and asserted its incom-

patability with American political and

religious ideals. By thus reinforcing the wide-

spread belief in the inherent evil of

the institution, Captain Riley played a meaningful,

if minor, role in preparing the way for

the ultimate downfall of slavery in America.

DONALD J. RATCLIFFE

Captain James Riley and Antislavery

Sentiment in Ohio, 1819-1824

Captain James Riley had an unusually

powerful reason for hating slavery: he had

himself been a slave.

Riley was born in 1777 in Middletown,

Connecticut, the fourth child of a humble

farming family. Between the ages of

eight and fourteen he attended common school

while earning his keep by working for

local farmers. At the age of fifteen, tired of

hard work on the land, he decided to

turn to a seafaring life. During the next twenty

years, as seaman and merchant, he

traveled widely, "making voyages in all climates

usually visited by American ships,"

but mainly to South America, the Caribbean, and

western Europe. The years of maritime

conflict with Britain and France after 1806

proved as financially disastrous to

Riley as to most other American overseas mer-

chants, and he spent the War of 1812 at

home in Connecticut trying to provide a

regular living for his wife and four

children. After the war when Riley again em-

barked on an overseas trading venture,

he suffered such a disastrous and agonizing

experience that he decided

"never" again to leave his native country.1

For a brief period after 1815 Riley

acted as a lobbyist in Washington, but his eyes

soon turned to the developing lands of

the West. In 1818 he traveled through Ken-

tucky, the Old Northwest and Upper

Canada. In 1819 he secured the office of deputy

surveyor of the public lands, a post for

which the technical skills he had learned as a

navigator qualified him. His particular

task was to survey the lands in the Maumee

River Valley recently purchased from the

Indians. Through his surveys the enter-

prising Riley offered the first

practical demonstration of the feasibility of connecting

the Wabash and Maumee rivers by a canal.

Deciding to settle in this promising land,

Riley moved his family in 1820 from New

England, first to Chillicothe, and then, in

the following year, to a frontier home

on the St. Mary's River near the Indiana line.

Here, with the aid of his sons, this

"large and powerful" man established the first

settlement in Van Wert County, Ohio, and

in 1822 laid out the town of Willshire. A

figure of local prominence, Riley was

elected to represent the sparsely settled north-

western counties in the General Assembly

for the session of 1823-24. In the legisla-

ture he was an eager advocate of schemes

for internal improvement, especially those

which would benefit his own locality.

Unfortunately, ill-health soon forced him to

1. James Riley, An Authentic

Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce . . .

revised ed., Hartford, Conn., 1829),

15-18, 260.

Mr. Ratcliffe is Lecturer in Modern History,

University of Durham, England.

(614) 297-2300