Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

ARNOLD SHANKMAN

Soldier Votes and Clement L.

Vallandigham in the 1863 Ohio

Gubernatorial Election

The Ohio gubernatorial election of 1863

was a hotly contested election with over-

tones extending to the national level.

The nation was engaged in a bitter civil war

which showed no signs of terminating,

and many citizens of the Buckeye State were

rapidly tiring of the conflict. A large

number of Ohio Democrats were dissatisfied

with the Lincoln administration's

handling of the war, and after the President issued

the Emancipation Proclamation they began

to fear that the Federal Government

was more interested in freeing the

slaves than in restoring the old Union. Further-

more, the peace Democrats, who were

derisively nicknamed Copperheads,1 believed

that continuation of the fighting would

cost Ohio millions of dollars, would cause the

deaths of even more Ohio soldiers, and

would promote the immigration of Negroes

who would compete with whites for jobs.

The most radical of the peace men called

for an armistice and proposed that a

convention of all the states devise a political

solution to the war. Others, agreeing

that further fighting was useless, protested

against the suppression of anti-war

newspapers and denial of the writ of habeas

corpus to men imprisoned for criticizing the government.2

The most eloquent spokesman of the peace

Democracy was Clement Laird Val-

landigham of Dayton. A fiery orator and

a skilled lawyer, he was the Third District's

1. Shortly after the start of the Civil

War the Springfield (Ohio) Republic published a letter

from a man who noted that the

rattlesnake was the emblem of the Palmetto State. He declared

that evil as this snake was, he thought

it better than the copperhead snake which struck without

giving any warning. Eventually

"Copperhead" became a term used to designate northerners

opposed to the continuation of the war.

Peace Democrats, nevertheless, did not consider the

epithet to be degrading, and some made

copperhead badges out of copper pennies which then

featured the likeness of the Goddess of

Liberty. Cincinnati Gazette, n.d. quoted in Philadelphia

Evening Bulletin, February 28, 1863; Wood Gray, The Hidden Civil War:

The Story of the

Copperheads (New York, 1942), 140-141.

2. Frank L. Klement, The Copperheads

in the Middle West (Chicago, 1960), 17-19, 29,

115-118; George Porter, Ohio Politics

During the Civil War Period (New York, 1911), 103,

107-108, 145-146; Eugene H. Roseboom, The

Civil War Era, 1850-1873 (Carl Wittke, ed., The

History of the State of Ohio, IV, Columbus, 1944), 409-410.

Mr. Shankman is a National Endowment for

the Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard

University.

|

|

|

representative in Congress until March 1863. Even before the outbreak of hostilities, in November 1860, he had gained notoriety when he told a public assembly in New York City that

If any one or more of the States of this Union should at any time secede for reasons of the sufficiency and justice of which, .. . they alone may judge, much as I should deplore it, I never would as a Representative in the Congress of the United States vote one dollar of money whereby one drop of American blood should be shed in a civil war.3

One month later at a meeting of Ohio delegates to Congress, who were assembled to discuss the question of secession, he supposedly stated that "no armed force

3. Quoted in James L. Vallandigham, A Life of Clement L. Vallandigham (Baltimore, 1872), 141-142. |

90 OHIO

HISTORY

should march through his District

to aid in putting down Southern rebellion."4

Because Vallandigham refused to moderate

his views after the firing on Fort

Sumter, many Republicans and some war

Democrats considered him to be a traitor.

In 1862, when the pro-war Ohio General

Assembly reapportioned the state's con-

gressional districts, Vallandigham

discovered that his district had been gerryman-

dered so that he could not win

reelection to Congress. The legislature's plan worked,

for Vallandigham was defeated in the

October elections. This setback only tempo-

rarily discouraged the Dayton lawyer. In

January 1863 he announced his candidacy

for the Democratic gubernatorial

nomination. War Democrats shuddered at the

thought of Vallandigham as governor, and

they rallied behind Hugh J. Jewett, the

Democracy's gubernatorial candidate in

1861. Vallandigham's nomination, how-

ever, was assurred after he was arrested

on May 5 for disloyalty. After a military

trial having dubious jurisdiction, he

was exiled to the Confederacy. Banishment to

Dixie made Vallandigham look like a

martyr for truth and liberty to most peace

Democrats. When the party's nominating

convention met in Columbus the next

month on June 11, Vallandigham's

popularity was at an all time high. George Hoyt

of the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported

that Democratic sentiment in the state capital

was "all [for] Vallandigham,

Vallandigham, nothing but Vallandigham." Not sur-

prisingly, the exiled Copperhead leader

was nominated for governor on the first

ballot.5

One week later, on June 17, 1863, the

Unionists held their party convention in

Columbus. Unwilling to nominate

incumbent Governor David Tod for a second

term because of his unpopularity with

the troops, the delegates turned instead to

William Henry Smith's choice, John

Brough, as their standard bearer. Brough, a

war Democrat who supported President

Lincoln, had been a state auditor and news-

paper editor but was at the time a

railroad executive. He insisted that the most

important issue before the voters was

the support of "the Government in the great

work of suppressing this most wicked

rebellion...."6

In the spirited campaign that followed,

both parties held scores of meetings in

every corner of the state and brought in

nationally known speakers to address the

electorate. Until the middle of

September it appeared as though the home vote

would be very close, and political

observers predicted that soldier ballots would

decide the election. To win soldier

votes the Democrats tried to persuade men in

blue that Vallandigham was their friend.

This could be done by looking at the rec-

ord. In Congress Vallandigham had

endorsed resolutions of condolence to the

orphans and widows of Union soldiers. He

had voted in favor of all bills to help

disabled Yanks and was among the first

who sought to amend the Volunteer Army

4. Dayton Journal, December 22,

1860. This paper wondered whether "chivalrous" Vallan-

digham meant "to make such an ass

of himself as to say he will resist to the death the organiza-

tion of a volunteer force in his district."

It added that the troops would not have to march over

his dead body, for they would travel

instead by train. Therefore, he would have "to throw

himself upon the iron rails, and allow a

dozen cars to pass over his mangled corse [sic]." See

also Congressional Globe, 37

Cong., 3 Sess., 1408-10.

5. Frank L. Klement, The Limits of

Dissent: Clement L. Vallandigham and the Civil War

(Lexington, 1970), Chapter 11; Cleveland

Plain Dealer, June 12, 1863.

6. During the war years the Ohio

Republican party campaigned under the Unionist party

banner. William Henry Smith was editor

of the Cincinnati Gazette. The Governors of Ohio

(Columbus, 1969), 85; Cleveland Morning

Leader, June 30, 1863.

|

bill so that Jewish rabbis could serve the troops on a basis of equality with Christian chaplains. Though Democrats probably would have to concede that Vallandigham had often tried to amend military bills in such a way as to embarrass Lincoln, they would be able to note that he had voted for some Army appropriation bills. As might be expected, they would try not to mention that Vallandigham had refused to endorse resolutions praising Major Robert Anderson for his stand against the Confederates at Fort Sumter or that he had refused to thank the officers and soldiers who fought at First Bull Run for their services to the country, nor would they note that their candidate had favored the Fugitive Slave Law and slavery on constitu- tional grounds.7

7. Frank L. Klement, "Clement Vallandigham," in Robert Wheeler, ed., For the Union: Ohio Leaders in the Civil War (Columbus, 1968), 12; Congressional Globe, 36 Cong., 2 Sess., 280, 453; 37 Cong., 1 Sess., 427, 448; 37 Cong., 2 Sess., 157; Sefton Temkin, "Isaac Mayer Wise and the Civil War," American Jewish Archives, XV '1963), 140-141; Cincinnati Enquirer, Sep- tember 16, 1863; The Crisis (Columbus), September 16, 1863; Vallandigham, Life of Clement L. Vallandigham, 71. See also Congressional Globe, 37 Cong., 1 Sess., 97-98, quoted in Cin- cinnati Enquirer, September 16, 1863. |

92 OHIO

HISTORY

Soldiers in favor of the war, however,

might not be influenced by such reports; they

had their own firsthand memories of

Vallandigham. They remembered that when he

had visited the Second Ohio Regiment in

the summer of 1861, he had been greeted

with cries, "There is that d - - d

traitor in camp," and "He is no better than a Rebel."

According to one account, a group of

Ohio volunteers approached the congressman

and told him that his presence in their

camp was not desired and that he should

return to Washington. Vallandigham

angrily retorted, "Do you think that I am to

be intimidated by a pack of blackguards.

. . ? I shall come to this camp as often

as I please,--every day if I

choose,--and I give you notice that I will have

you taken care of." As he departed

the camp, he had been pelted with "onions and

old boots" and was obliged to pass

a bullet-riddled effigy of himself bearing the

inscription "Vallandigham the

Traitor." Moreover, Union soldiers would remember

that it was the testimony of two Ohio

Yanks who had attended the fateful rally in

Mount Vernon on May 1, 1863, that had

led to his arrest four days later.8

News that Vallandigham had been arrested

for his anti-war speeches excited many

of the men in blue. Tully McCrea, an

Ohio officer from Christiansburg, happily

wrote, "Served him right and I only

wish that some more of the same sort could

be treated in the same way." One

enlisted man claimed that he knew "of nothing

which . . .has cheered the hearts of

these Western soldiers so much as the arrest and

sentence of Vallandigham. There are

upwards of fifty Ohio regiments in this army,

and the severest trial which they have

been obliged to undergo was the treason of

Vallandigham in their own State."9

Another declared that if "Vallandigham had

been turned over to the soldiers for

punishment, he would have received just desserts.

He would have been on his way to glory

by this time. God is just and will take him

in his [sic] own good time."

Apparently these men cared little about the question-

able aspects of Vallandigham's trial,

and agreed with an unidentified Ohio officer

who argued that treason flourishing in

the Middle West "must be stopped and put

down now. . .and military tribunals are the only ones that can do

it."10

Naturally these soldiers were disgusted

when they learned that Vallandigham

was the Democratic gubernatorial

nominee. One Illinois officer reflected the senti-

ments of most of his Ohio friends when

he wrote:

Vallandigham nominated for Governor of

Ohio! Shame! Shame! upon the professed

Union men who permitted such a

convention in their midst . . .I can only adequately

express my feeling in big sounding

"cuss" words.ll

8. Cleveland Plain Dealer, July

11, 1861; Charles Carleton Coffin, The Boys of '61; or, Four

Years of Fighting... (Boston, 1883), 9-11; Vallandigham, Life of Clement

L. Vallandigham,

168-169. The two men were Captains John

Means and Harrison Hill. Arnold Shankman, ed.,

"Vallandigham's Arrest and the 1863

Dayton Riot--Two Letters," Ohio History, LXXIX

(Spring 1970), 120-121.

9. Tully McCrea, Dear Belle, edited

by Catherine Crary (Middletown, Connecticut, 1965),

198-199; Boston Journal, n.d.,

quoted in The Liberator (Boston), June 12, 1863.

10. B. S. DeForest, Random Sketches

and Wandering Thoughts (Albany, 1866), 205-206;

Mildred Throne, ed., "An Iowa Doctor

in Blue; The Letters of Seneca B. Thrall, 1862-1864,"

Iowa Journal of History, LVIII (April 1960), 149, 157; Leverett Bradley, A

Soldier Boy's Let-

ters, edited by Susan Bradley (Boston, 1905), 25;

unidentified Ohio army officer letter quoted

in Pittsburgh Gazette, May 30,

1863.

11. June 16, 1863, Diary entry in Paul

Angle, ed., Three Years in the Army of the Cumber-

land: Letters and Diary of Major

James Connolly (Bloomington, 1959),

88-89.

Soldier Votes 93

Equally indignant that "the Prince

of traitors" had received the Democratic nomina-

tion was Lieutenant Tully McCrea, who

announced that he would vote against Val-

landigham. He wished that he possessed a

hundred more "votes to dispose of in the

same manner" and added, "If it

had not been for him and others like him, I think

that the war would have ended long

ago."12

Although Rutherford B. Hayes did not

"like arbitrary or military arrests of civil-

ians in States where the law is

regularly administered by the Courts," he considered

the Democrats' selection of Vallandigham

a "pretty bold move":

Rather rash if it is considered that

forty to sixty thousand soldiers will probably vote. I

estimate that about as many will vote

for Vallandigham as there are deserters in the

course of a year's service--from one to

five per cent. A foolish (or worse) business,

our Democratic friends are getting

into.13

Hayes' letter was quite mild compared to

one Lucius Wood, an Ohio volunteer

from the Western Reserve, sent to his

father, a minister. Wood dismissed Vallandig-

ham as an "old arch instigator of

treason" and predicted that "he shall fall as the

angels whose hearts were full of

treachery fell from the holy gates of Paradise." To

him, Vallandigham's nomination meant

that Ohioans had lost their sense of honor.

Therefore he urged his father "to

leave no stone unturned, for the contest will be

a hot one":

In the name of my brethren in the field

I appeal to you to leave the plough in the field,

leave your trade & business until

the needful work is accomplished... we, the soldiers,

look to you in the central and northern

portion of the State to cast the votes largely in

favor of the cause of humanity and

justice.14

For the Unionists, news of John Brough's

nomination delighted such officers as

James Garfield, who had strongly opposed

another term for Governor Tod, and

he sent a letter of congratulations to

William Dennison, the chairman of the Unionist

convention.15 Others were

less satisfied with Brough, whom one soldier described

as a "fat English bloat."

Another noted that "there are many that don't like the

Administration and are not suited with

the nomination of Mr. Brough"; he acknowl-

edged that he was one "among that

number." Nonetheless he would "eagerly cash

in" his vote for Brough and under

no circumstances would he cast a ballot for the

Copperhead Vallandigham16

Several factors in addition to the

national patriotism it symbolized commended

the Unionist party to the soldiers.

First, Unionists had recognized three delegates

12. May 16, 1863, letter, McCrea, Dear Belle, 199.

13. Hayes to S. Birchard, June 14, 1863, in

Charles R. Williams, ed., Diary and Letters of

Rutherford Hayes (Columbus, 1922), II, 413.

14. Lucius Wood to parents and sister,

September 17, 1863. Lucius and Julius Wood Papers,

Western Reserve Historical Society.

15. Garfield to [John Q.] Smith, May 30,

1863, and Garfield to wife, June 21, 1863, in

Frederick D. Williams, ed., The Wild

Life of the Army: Civil War Letters of James A. Garfield

(Lansing, 1964), 284; Cleveland Plain

Dealer, June 25, 1863.

16. Thomas Galwey, The Valiant Hours, edited

by Colonel Wilbur Nye (Harrisburg, 1961),

149-150; Lucius Wood to parents and

sister, October 11, 1863, Wood Papers.

94 OHIO

HISTORY

to their nominating convention who

represented--or claimed to represent--the

Army of the Cumberland. At the

Democratic convention there had been no dele-

gates from the Buckeye troops. Second,

the Unionist candidate for lieutenant gov-

ernor was Colonel Charles Anderson,

brother of the hero of Fort Sumter and a dis-

tinguished soldier who had escaped from

a Texas jail at the start of the war. Finally,

Vallandigham's anti-war speeches in

Congress hardly enhanced his popularity with

Yanks determined to defeat the

Confederates on the battlefield. In fact, when the

Democracy of Champaign County nominated

Lieutenant William Hamilton of the

Sixty-Sixth O.V.I. for a county office,

he insisted that he would not run on the same

ticket as Vallandigham. To do so, he

claimed, would be to descend "a little lower

in the scale of degradation than I had

expected to reach." He promised to vote for

Brough at the coming election. Nor would

George Pugh, Vallandigham's running

mate appeal to the soldiers since he had

been the candidate's defense lawyer at the

court martial and had been making

speeches violently opposing General Burnside's

Order No. 38 under which the arrest had

been made.17

Despite these handicaps Democrats

attempted to win soldier votes. Unionists

made this task difficult because they

were constantly reminding the men in blue that

in congressional debates on military

appropriations in 1862 Vallandigham had op-

posed a hundred dollar bounty and a pay

increase for them. Moreover, they said,

Vallandigham believed that their

courageous services to their country were in vain.

To counter these charges the Democrats

explained that their candidate had opposed

the pay increase only because he wanted

the soldiers to be paid in gold rather than

in depreciated greenbacks and that he

had even introduced legislation in Congress

to give them a larger salary and bounty.

Congress, however, had not seen fit to enact

his proposal into law. Vallandigham's

supporters also denounced the Republicans

in Congress who were giving away public

lands to "those who remained at home"

instead of reserving the 160 acres

promised to each man who enlisted in 1861. Val-

landigham, they claimed, had voted

against the land give away but the Republicans

were still charging him with "being

the soldiers' enemy!"18 In a further effort to dem-

onstrate that the veterans would not

fare well under the Republicans, it was noted

by the Democrats at the end of the

campaign that when in Congress, Abraham

Lincoln had voted against giving

soldiers fighting in the Mexican War tracts of land

of 160 acres.19

Not only did Democrat journals attempt

to portray Vallandigham as the friend

of the soldier, but they also tried to

prove that Brough, the president of the Indian-

apolis, Pittsburgh, and Cleveland

Railway, was the enemy of the fighting man. They

noted that even George B. Wright,

ex-Governor William Dennison's quartermaster

general, had accused Brough of refusing

to transport sick and wounded soliders on

his railroad for half-fare. At

Vallandigham rallies one could often see banners pro-

claiming, "No half-fare

arrangements for soldiers on this Railroad.--By order of

17. Cleveland Herald, September

28, 1863; Roseboom, Civil War Era, 415; Porter, Ohio

Politics, 170-174.

18. The Crisis (Columbus),

September 16, 1863; Cincinnati Enquirer, September 10, 16, 1863;

William Young, "Soldier Voting in

Ohio During the Civil War" (unpublished M.A. thesis, The

Ohio State University, 1948), 40.

19. Marietta Republican, October

1, 1863.

Soldier Votes 95

John Brough, Receiver."20

Democratic strategy concentrated on

exploiting possible soldier discontent. Why,

their orators asked, must the fighting

men suffer the privations of war and separation

from their loved ones just to fight a

war for the abolitionists? Was emancipation

worth the fighting, killing, and dying?

Lurid stories were told about underfed Union

forces standing guard at lavish Negro

picnics. The following arguments summarized

the basic Democratic position:

You desire when you return to civil life

to be secure in person and property. Then stand

by the Constitution and laws which

guarantee that security. Vote the Democratic ticket,

and when you return to your homes, you

will have the satisfaction of remembering that

in this contest you took the right

side.21

In his "Democratic Address to

Soldiers," General William S. Rosecrans pro-

claimed that political tracts could be

distributed to the Army unless such literature

was "licentious, lying, or

traitorous" and might endanger the morality or vigor of

the soldiers. Treasonable pamphlets, he

declared, should not be allowed to circulate.

Apparently the "Address" was

interpreted by some as being a justification for the

suppression of Democratic publications.

One private in Rosecrans' army wrote

his brother:

There are about one-half the troops in

this department who would vote the Democratic

ticket if they could only get a

Democratic paper occasionally. But that pleasure is denied

them, for what reason I cannot say,

unless it is for political interest. It seems strange to

me they won't let us read what we

choose... they cried out that the soldiers did not want

to read them [Democratic newspapers].

Now, if this were so, they would have no cause

to stop their circulation. Let them go

on and impose upon the soldiers while they can,

is evidently their determination.22

In many regiments Democratic orators

were as unwelcome as Vallandigham political

literature. According to the Cincinnati Commercial,

a Brough organ, Democrats

had been prohibited from visiting Ohio

troops south of Nashville. Those sent to

make sure that the Army of the

Cumberland would have ample Democratic ballots

were stopped since the Army did not want

Vallandigham "'missionaries' to reach

Ohio regiments anywhere."23

Unionists, on the other hand, had no

trouble deluging the Yanks with propa-

ganda. One provocative leaflet entitled

"The Peace Democracy, Alias the Copper-

heads" denounced Vallandigham for

his "excessive vanity and audacity, his fanatic

passions and morbid prejudices, [and]

his destitution of patriotism." It also stated

that the Democratic candidate had

"no intellectuality, moral worth. . .or social stand-

20. Cincinnati Enquirer, August

18, 26, 1863; Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 2, September 3,

1863; Richard Abbott, Ohio's Civil

War Governors (Columbus, 1962), 39.

21. Young, "Soldier Voting,"

27. The August 5, 1863 issue of The Crisis (Columbus) fea-

tured a letter from a soldier in a local

hospital who could not afford to subscribe to that paper

because he had not been paid. He estimated that half of

the soldier patients in the hospital

then were "Vallandigham men" and that in one

month two-thirds would support Vallandigham

if they had access to The Crisis.

22. Young, "Soldier Voting,"

24; Marietta Republican, August 27, 1863.

23. Young, "Soldier Voting,"

46.

96 OHIO HISTORY

ing." Other propaganda claimed that

Vallandigham had only proposed to raise the

pay of soldiers in gold rather than

greenbacks because he knew that the precious

metal was unavailable in sufficient

quantities to make such payments; moreover,

when he was in exile in Dixie, they

declared, he had refused to request adequate

rations for Union prisoners-of-war. With

great satisfaction Chaplain Randall Ross

of the Fifteenth Ohio Volunteers wrote

to the Ohio State Journal (Columbus) on

October 3, 1863, that those soldiers who

received Copperhead political propaganda

in his regiment tore it into strips,

stamped the scraps of paper into the dust, and

yelled, "damn all such papers....

If we were home, we'd clear them out."24

Ross may have overstated the soldiers'

hostility to Democratic literature, and he

certainly neglected to mention that

Unionist tracts were often ineffective as political

propaganda. Thomas Galwey, a volunteer

from northern Ohio, noted on September

11, 1863, that just as he and his

comrades were stretched out to rest, a "handsome

barouche drawn by two horses drove

up." At first he thought that the men inside

were peddlers:

But we soon found that they had been

sent out to teach us how to vote at the coming

election for Governor of Ohio. Their

credentials were beyond dispute, and they had

passes from Secretary Stanton admitting

them to all parts of the Army. They had a great

number of copies of a pamphlet,

professing to give the "record" of Clement Vallan-

digham, the Democratic candidate for

Governor of Ohio. The pamphlet also exhibited

the patriotic struggle of the Republican

candidate, a Mr. Brough, who was a sort of rail-

road king at the time in Ohio. He was an

enormously fat specimen of [a] selfish English

glutton. But to the enthusiastic Yankees

of the Western Reserve, he was the beau ideal

of a patriotic Union man. We took their

pamphlets and slept on them, for we stuffed

them in our knapsacks.25

On the whole, however, soldier letters

and diaries indicate that the Unionist

campaign was much more effective than

the Democratic effort to win their votes.

One Buckeye Yank wrote his cousin:

Father writes to me and tells me not to

vote for Vallandingham [sic].... do you think

the soldiers will vote for a man that

they hate worse than they do the rebels?... for we

know that just such men as Vallandingham

[sic] is keeping up this war and by keeping

up this war and by keeping it up is

causing all this misery. It makes me feel bad for a

friend to tell me not to vote for a

worse than rebel.26

Another volunteer, who feared that

Vallandigham might win a majority of the civil-

ian vote, rejoiced that most of his

comrades were opposed to the Copperhead leader.

"Once in a while I see a soldier

who says he will vote for him," he stated, "but they

are few in number." A third soldier

wrote a friend: "There are quite a number here

anxious to give that exile Vallandigham

a kick and Brough a vote." Many equated

supporting the Democratic candidate with

expressing sympathy for the South, and

after Morgan's Raid into Ohio, one Yank,

who was stationed at a "frontier" outpost

24. Ibid., 20, 42; Cleveland Morning

Leader, October 9, 12, 1863.

25. Galwey, Valiant Hours, 141.

26. Eugene H. Roseboom, "Southern

Ohio and the Union in 1863," Mississippi Valley His-

torical Review, XXXIX (1952), 34.

Soldier Votes 97

claimed that "Morgan certainly

deserves something from the admirers of Vallandig-

ham for stumping his state for him

during his absence."27

A few soldier correspondents expressed

hostility not only to Vallandigham but

also to anyone who expressed willingness

to vote Democratic in the election. One,

for example, urged his parents to

"torment" their Copperhead neighbors "all you can

until we get home." Another Ohio

Yank, writing from Mississippi a week after

the surrender of Vicksburg, expressed

his desire to kill all voters back home in Shelby

County "who were going to vote for

Old Val." A Brough partisan wrote to his

cousin, a Vallandigham Democrat:

"They say that all bad men will go to Hell, but

I think there will be a special part of

it fitted out for just such men as you are."28

Occasionally Unionist soldiers made

known their opposition to Vallandigham

at Democratic rallies. At one political demonstration

in Franklin County at which

Congressman Samuel "Sunset"

Cox and a Colonel Groom spoke to 1000 civilians,

about sixty furloughed Yanks approached

the speaker's stand armed with sticks,

clubs, and revolvers. In an effort to

avoid a confrontation the soldiers were invited

to listen to the speeches and to join in

the picnic that was planned for them after

the rally. Since the soldiers were

unimpressed with the offer, the orators left the

speaker's platform as "it became

evident that men, women, and children would be

massacred if the speeches

proceeded." The rally was adjourned until later in the

afternoon. Meanwhile one Democrat went

to nearby Camp Chase and another to

Columbus to summon help. Fifty men came

from Columbus, but they "were very

loth [sic] to do their

duty." While Cox was addressing the assemblage, one Buckeye

volunteer drew his gun as if to shoot

the speaker. Before violence errupted three

"omnibusses [sic]" of

Columbus Democrats arrived at the site of the gathering.

Some of these men were armed and they

"drove the assailants back." The congress-

man "appealed to" the Yanks to

honor and uphold the Constitution, which guar-

anteed peaceable assemblages. The New

York Tribune denounced "some excitable

invalid soldiers" who destroyed a

Vallandigham banner at another Democratic rally

in Franklin County and noted that the

episode had "given immense satisfaction to

the Copperheads." That "silly

act," the Tribune argued, had "given a show of rea-

son to the cry of persecution, and the

Vallandighammers are making the most of it."29

Intoxicated Democrats returning to their

homes from a Vallandigham meeting

were once stopped by guards from Camp

Chase, who made the civilians take an

oath of loyalty in which they promised

not to vote for Vallandigham or Pugh. One

man refused, stating that he would

rather die than to take such an oath; he changed

his mind, however, when one of the Yanks

asked for a rope to hang him.30

Who then did support Vallandigham?

Seneca Thrall, an Iowa volunteer who had

been born in Ohio, spoke about the men

he thought belonged to the Vallandigham

faction. According to him, Irish

Catholics and especially the party leaders who

27. Lucius Wood to parents and sister,

October 11, 1863, Wood Papers; John A. Kummer

to Colonel Lewis P. Buckley, quoted in Summit

County Beacon (Akron), August 20, 1863;

Nannie Tilley, ed., Federals on the

Frontier: The Diary of Benjamin Mclntyre (Austin, 1967),

203.

28. Julius Wood to parents and sister,

October 11, 1863, Wood Papers; John Stipp to author,

March 27, 1969, concerning Stipp's grandfather; Ohio

State Journal (Columbus), October 3,

1863.

29. Cleveland Plain Dealer, August

31, 1863; New York Tribune, August 6, 1863.

30. Young, "Soldier Voting,"

38-39, 41.

98 OHIO

HISTORY

would vote for the Dayton Copperhead

were the men who expected "large crumbs

from the public treasury" if a

slave power ruled the country. He therefore con-

sidered them to be traitors:

Vallandigham and others of that stripe are

so much to be execrated, as was even Aaron

Burr, and deserve the traitor's death,

by hanging by the neck until they are dead--dead

--dead.... Such is the feeling of 29 out

of 30 men in the army.... Vallandigham in

Ohio and Tuttle in Iowa, have no more

prospect of being elected than I have....31

Rare indeed was the soldier who publicly

acknowledged that he would support Val-

landigham. To make such an admission was

to invite one's colleagues to torment

him. One Yank from Youngstown informed

his father that it was useless to con-

tinue sending him Democratic campaign

progaganda. He complained:

I stand nearly alone here, the defender

of the patriot exile, Clement L. Vallandigham.

There is a perfect furor of excitement

against him, and others, who pretended to be good

Democrats at Potomac Creek have yielded

to the damnable pressure.32

Democratic newspapers, however, refused

to admit that the situation was as dis-

mal as the above soldiers indicated.

With great avidity they printed and reprinted

every pro-Vallandigham letter from Ohio

Yanks they could find. The Columbus

Enquirer of August 23, 1863, reprinted a letter from the

Circleville Democrat which

stated that the number of soldiers

favoring Vallandigham was increasing. This, the

writer said was "owing to the zeal

of ultra Abolitionists...." The men in blue

resented hearing their sergeants call

"all who do not go in for the nigger. . .a Copper-

head, a Butternut, and all the other

beautiful names by which Democrats are desig-

nated ...." Another letter from the Circleville Democrat which

was published on

August 15, 1863, and reprinted in the Enquirer was

from a volunteer who was not

certain that he would vote. If he did

decide to cast a ballot, he stated, it would be

for Vallandigham, for "the very

best soldiers we have got will vote for Vallandig-

ham." Though he considered himself

to be "a Democrat and a good Union man,"

he would "never give up for the

Republicans to rule the Democrats." He concluded

by asking that two hundred Vallandigham

voting tickets be sent him, claiming, "I am

acquainted with that many Democratic

voters."33

According to a soldier letter printed in

the Cincinnati Enquirer, the officers and

men of one regiment were afraid to make

their political views known if they favored

Vallandigham since enlisted men had been

denied a furlough granted to them pre-

viously, and the field officers were

warned that they would be charged with disloyalty

if they supported Vallandigham. Peace

newspapers became so skeptical about the

possibility of soldiers being able to

vote Democratic in large numbers that they be-

came disenchanted with the soldier

voting law. A number of Copperhead organs

announced that if Vallandigham won a

majority of the civilian votes, they would

consider him to be the lawful governor

of Ohio and would not count the soldier

votes.34

31. Throne, "Letters of Seneca

Thrall," 169.

32. Quoted in Roseboom, "Southern

Ohio and the Union," 34.

33. Cincinnati Enquirer, August

18, 23, September 23, 1863.

34. Ibid., October 9, 1863;

Porter, Ohio Politics, 182.

Soldier Votes 99

Noting that the soldier voting laws of

Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and New Hamp-

shire had been ruled unconstitutional,

peace journals wondered whether the Ohio law

was valid. "A soldier vote law is

no more constitutional here," declared the Cin-

cinnati Enquirer, "than it

is in the other States...." Such sentiments were not likely

to influence soldiers to vote for

Vallandigham, but Democrats were still afraid that

soldier ballots might cost Vallandigham

the election. Late in the campaign when it

was becoming apparent that soldier votes

would most likely be Brough votes, Val-

landigham encouraged his friends to

concentrate on winning votes on the home front.

He would be satisfied, he claimed, if he

received a substantial majority of the non-

military votes, for then he would have

"a fair prospect of carrying the election

straight out all over."35

Some Unionists feared that Ohio Yanks

would not be able to vote on election day

because of military engagements or other

difficulties, but they should not have wor-

ried. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton

needed no reminder as to the importance of the

election. He arranged for Ohioans

working as clerks in the War Department "to go

home on leave with free railroad

passes." There is also good reason to believe that

he permitted many Ohio soldiers to have

fifteen to twenty day furloughs so that they

might return home and urge their friends

to vote for Brough. Lucius Wood reported

that the Yanks in his camp were

"all going home to vote;. . . [they number] about

seven hundred and a more highly pleased

set of fellows you have never seen." Re-

ports of hordes of soldiers returning to

Ohio from distant camps to "help beat Val-

landigham" caused the Wilmington Journal

(North Carolina) to comment that is was

no longer "very confident of

Vallandigham's election."36

When the votes were counted, it was

evident that most of the Ohio Yanks who

participated in the October elections

voted for Brough. The New York Tribune, a

Unionist paper, had predicted that

because of his opposition to the war Vallandigham

would not win one-tenth of the soldier

vote; actually he barely received half that

number. (See Table on Election

Returns on p. 102.) His supporters were chagrined

that he had done so poorly, and they

attributed his failure to obtain more votes to

coercion at the polls and the inability

of Ohio troops to obtain Democratic news-

papers.37

There was much truth to the charge of

electoral irregularities. Captain John

Means denied charges that he had

interfered with the rights of his men to vote as they

pleased, but he admitted that no

Democrat voting tickets [ballots] had been sent to

his camp. Had any arrived, he stated,

"I would have thrown them into the fire; that

I never would be caught peddling tickets

for a traitor, that I expected every man to

vote for whom he pleased, but that I

considered Vallandigham as great a traitor as

Jeff Davis, but not as honest, and the

soldier who voted for him was but little better."

He sent a list of those Yanks who still

dared to vote against Brough to the Summit

County Beacon (Akron) so that all residents of the Akron area would

know who

35. Vallandigham to Manton Marble,

October 4, 1863, Marble Papers, Library of Congress;

Cincinnati Enquirer, February 6,

July 19, 1863; Josiah Benton, Voting in the Field (Boston,

1915), 73-75.

36. Harold Hyman and Benjamin Thomas, Stanton:

The Life and Times of Lincoln's Sec-

retary of War (New York, 1962), 292, 294; Thomas Thoburn, My

Experiences During the

Civil War, edited by Lyle Thoburn (Cleveland, 1963), 40, 42;

Lucius Wood to parents and

sister, October 11, 1863, Wood Papers;

Wilmington Journal, (North Carolina), October 6, 1863.

37. New York Tribune, August 29,

1863; Cincinnati Enquirer, October 14, 17, 1863.

100 OHIO

HISTORY

they were. In several camps newspaper

reporters peered over the shoulders of

soldiers as they voted, noting whether

they could properly sign their names and for

whom they cast their ballots. In one

instance reported to the Crisis, Democratic

voters were sent away from their

barracks on election day so they would be unable

to cast ballots. Since only twenty-four

of the Yanks left behind were willing to vote

Unionist, authorities let the Negro cook

vote for Brough.38

A number of soldiers found it to be

dangerous to make known their support of the

Democratic gubernatorial candidate. The Highland

News (Hillsboro) reported on

November 12, 1863, that it had received

an interesting soldier letter which it printed.

The author claimed that in his company

at Camp Dennison there were two Vallandig-

ham supporters. One was whipped for

"hallowing" Vallandigham before the election;

afterwards he deserted. The other

soldier became "ashamed" and voted for Brough.

Two Ohio Yanks who voted for

Vallandigham in camps in Kentucky allegedly were

arrested and placed under guard.

Another, Captain B. F. Sells, of the 122nd O.V.I.,

Company D was jailed for campaigning for

the Democrats. He had supposedly urged

the troops to vote for Vallandigham and

had circulated copies of the Columbus Crisis,

the Coshocton Democrat, the

Guernsey Jeffersonian, and Vallandigham's Record.39

Thomas Galwey of the Eighth Ohio

Infantry noted:

Not more than one-third of my regiment

who voted were qualified, being under age,

residents of other states, or

unnaturalized foreigners. But so biased had we simple men

become, by the misrepresentations of the

so-called loyal and patriotic "Union" man who

had been sent out at public expense to

canvass the soldiers to vote for the bloated English-

man [Brough], that we excused any

irregularity in the mode of conducting the election

as being a military necessity.

Galwey was elected a judge for the

election although he was not yet "twenty-one

years of age as the law requires."

The soldiers claimed that "a man who is old enough

to fight for his country and to risk his

life for it is better qualified to vote than are

the stay-at-home patriots." Before

casting ballots, the men unanimously resolved

to vote "each and every one of

us" for Brough. Thomas Taylor wrote from Poca-

hontas, Tennessee, that many soldiers in

Company F of the Forty-Seventh Ohio

Infantry were minors and unable to vote.

He cryptically added that he had knowingly

counted Brough ballots from scores of

soldiers who were ineligible to vote. He

warned his wife, "You need not say

anything concerning this to anyone."40

Lieutenant John C. Gray reported one instance

of soldiers reacting negatively to

the pro-Brough pressure:

The Ohio troops in this division are now

voting, many of them for Vallandigham; sev-

eral, they say, vote for him because

their captains do not and they wish to spite their

38. Means to editor, dated December 4,

1863, in Summit County Beacon (Akron), Decem-

ber 17, 1863. John Means was one of the

men who took notes on Vallandigham's Mount Vernon

speech which led to the ex-congressman's

arrest. The Crisis (Columbus), December 23, 1863;

Young, "Soldier Voting," 47.

39. Roseboom, "Southern Ohio and

the Union," 34 fn. 11; Cincinnati Enquirer, October 17,

1863; Montrose Democrat (Pennsylvania),

December 10, 1863; Young, "Soldier Voting," 47;

specifications against Sells, quoted in Pittsburgh

Post, November 18, 1863.

40. Galwey, Valiant Hours, 149-150;

Taylor to wife, October 13, 1863, Taylor Papers (micro-

film at Emory University).

Soldier Votes 101

captains. So much for the advantages,

military and political, of introducing voting into

the army.41

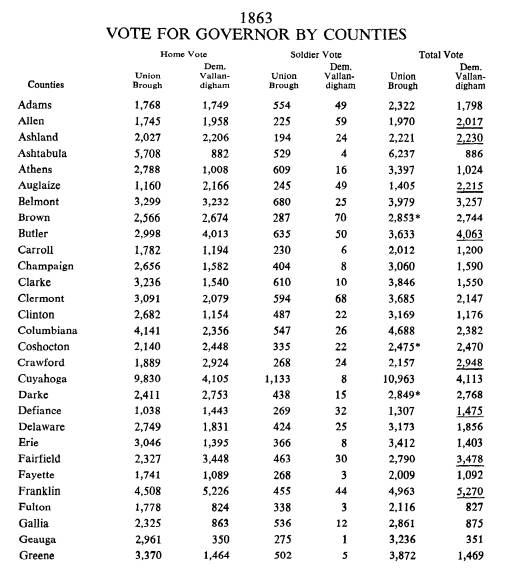

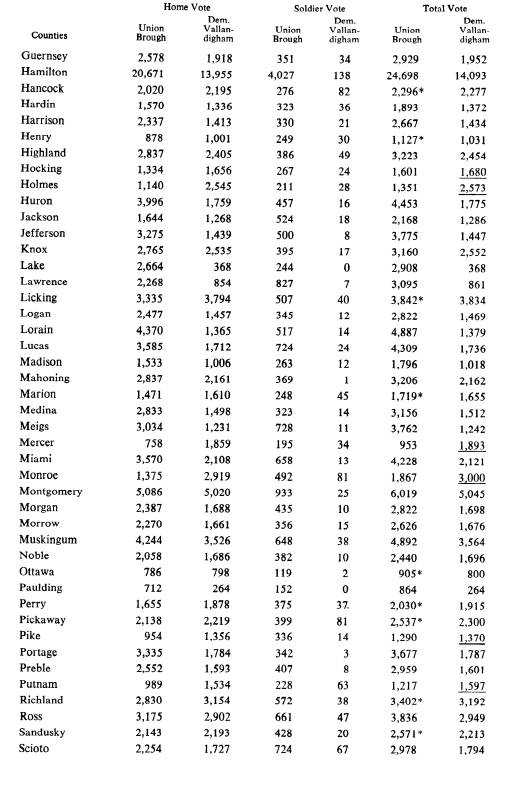

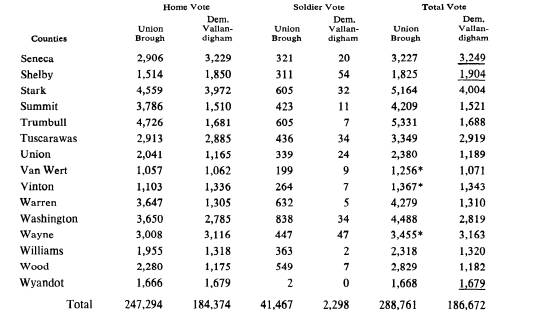

Despite the great efforts made by the

Unionists and others to enable soldiers to

vote, less than thirty percent of the

Ohio troops actually cast ballots. Of the Yanks

who exercised the franchise, 41,467

voted for Brough and only 2,298 for Vallandig-

ham. Thus, the military vote was an

overwhelming triumph for Brough and a vote of

confidence for the Lincoln

administration. The Utica Herald (New York) observed:

"As for the [Ohio] soldier's vote,

it won't do to mention that. Bullets are disagree-

able, but soldiers' ballots are worse

than their bullets." This paper alleged that more

than half of the men in the army were

Democrats, and it concluded, "It is sad to

be slain in the house of one's

friends."42

News of Brough's victory aroused

enthusiastic response from the troops. Accord-

ing to one story told at the time, a

soldier in Tennessee reported that when General

Rosecrans received telegraphic reports

of the election, he sent them around to all of

the camps. "You should have heard

the cheering," he wrote to a friend, for "the

Ohio bands played on [n]early all night,

and there was rejoicing generally." Another

story claimed that the noise of the

celebrating by the Ohioans at Fort Wood, Tennes-

see was so loud that it attracted the

attention of rebel pickets stationed at a nearby

Confederate camp. One asked what the

commotion was all about and when told

that Vallandigham had been defeated, he

advised a comrade to send word of the

result of the election to General

Braxton Bragg.43

Ohio officers shared in the jubilation

of their men. From Chattanooga, General

James Garfield noted that from the

"hour, but not till that hour [that we knew Brough

had won], the army felt safe from the

enemy behind it." Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes

gave a similar report and equated the

Unionist victory with "a triumph of arms in an

important battle." To him it showed

"persistent determination, willingness to pay

taxes, to wait, to be patient."44

In the Army of the Cumberland

festivities were beclouded by the bloody setback

experienced on September 19-20, 1863. To

an Ohio citizen leaving for home on

October 14, 1863, General Rosecrans gave

this message: "Tell them that this army

would have given a stronger vote for

Brough, had not Vallandigham's friends over

yonder killed two or three thousand Ohio

voters the other day at Chickamauga."45

Even though the Democratic party leaders

in 1864 tried to give the impression of

having moderated their stand on the war

with the selection of General George B.

41. Worthington Ford, ed., The War

Letters of John Gray and John Ropes (Boston, 1927),

229.

42. Porter, Ohio Politics, 183;

Joseph Smith, History of the Republican Party in Ohio (Chi-

cago, 1898), I, 162; see table

showing the vote for governor by counties, p. 102; quoted in

Albany Atlas and Argus (New

York), October 16, 1863.

43. Charlie M. D. to Mollie Post,

October 19, 1863, Philip S. Post Papers, Knox College;

Frazar Kirkland, The Pictorial Book

of Anecdotes and Incidents of the War of the Rebellion

... (Toledo, 1873), 70.

44. Burke A. Hinsdale, ed., The Works

of James Garfield (Boston, 1882), I, 17; Williams,

Diary and Letters of Hayes, II, 440; see also J. W. Chamberlain,

"Scenes in Libby Prison,"

Sketches of War History by the Ohio

Commandery of the Loyal Legion (Cincinnati,

1888),

II, 356.

45. Quoted in Hinsdale, Works of

Garfield, I, 480.

|

102 OHIO HISTORY

McClellan as presidential nominee, the selection of the Ohio peace Democrat George A. Pendleton for vice president as well as the peace plank in the platform, which was the work of Vallandigham, resulted in a "confusion of tongues." The ensuing defeat, though decisive, however, failed to still Vallandigham and the other peace Democrats.46 |

|

46. Roseboom, Civil War Era, 432-434. |

|

104 OHIO HISTORY |

|

LEGEND: 1. Underline indicates Democratic majority vote in county. 2. Asterisk indicates county where home vote was Democratic but soldier vote made a Union majority. DOCUMENTATION: Figures corrected from Joseph Smith, History of the Republican Party in Ohio (Chicago, 1898), I, 161-162. OBSERVATIONS: 1. Seventeen counties voted Democratic in the total count. Fifteen other counties gave a majority to Vallandigham in the home vote, but the large pro-Brough soldier vote put these counties in the Union column. 2. If the soldier votes cast for Brough and Vallandigham were reversed, the total number of counties carried by the Democrats then would have increased from 17 to 41, and the Union party would have carried only 46 counties instead of 71. Noble County's vote would have resulted in a tie. Nevertheless, Brough would still have won the election with a total vote of 249,592 to 225,841 for Vallandigham, a difference of only 23,751 votes. This narrowed margin indicates that emphasis on the soldier vote was important but not decisive. |

ARNOLD SHANKMAN

Soldier Votes and Clement L.

Vallandigham in the 1863 Ohio

Gubernatorial Election

The Ohio gubernatorial election of 1863

was a hotly contested election with over-

tones extending to the national level.

The nation was engaged in a bitter civil war

which showed no signs of terminating,

and many citizens of the Buckeye State were

rapidly tiring of the conflict. A large

number of Ohio Democrats were dissatisfied

with the Lincoln administration's

handling of the war, and after the President issued

the Emancipation Proclamation they began

to fear that the Federal Government

was more interested in freeing the

slaves than in restoring the old Union. Further-

more, the peace Democrats, who were

derisively nicknamed Copperheads,1 believed

that continuation of the fighting would

cost Ohio millions of dollars, would cause the

deaths of even more Ohio soldiers, and

would promote the immigration of Negroes

who would compete with whites for jobs.

The most radical of the peace men called

for an armistice and proposed that a

convention of all the states devise a political

solution to the war. Others, agreeing

that further fighting was useless, protested

against the suppression of anti-war

newspapers and denial of the writ of habeas

corpus to men imprisoned for criticizing the government.2

The most eloquent spokesman of the peace

Democracy was Clement Laird Val-

landigham of Dayton. A fiery orator and

a skilled lawyer, he was the Third District's

1. Shortly after the start of the Civil

War the Springfield (Ohio) Republic published a letter

from a man who noted that the

rattlesnake was the emblem of the Palmetto State. He declared

that evil as this snake was, he thought

it better than the copperhead snake which struck without

giving any warning. Eventually

"Copperhead" became a term used to designate northerners

opposed to the continuation of the war.

Peace Democrats, nevertheless, did not consider the

epithet to be degrading, and some made

copperhead badges out of copper pennies which then

featured the likeness of the Goddess of

Liberty. Cincinnati Gazette, n.d. quoted in Philadelphia

Evening Bulletin, February 28, 1863; Wood Gray, The Hidden Civil War:

The Story of the

Copperheads (New York, 1942), 140-141.

2. Frank L. Klement, The Copperheads

in the Middle West (Chicago, 1960), 17-19, 29,

115-118; George Porter, Ohio Politics

During the Civil War Period (New York, 1911), 103,

107-108, 145-146; Eugene H. Roseboom, The

Civil War Era, 1850-1873 (Carl Wittke, ed., The

History of the State of Ohio, IV, Columbus, 1944), 409-410.

Mr. Shankman is a National Endowment for

the Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at Harvard

University.

(614) 297-2300