Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

DAVID L. PORTER

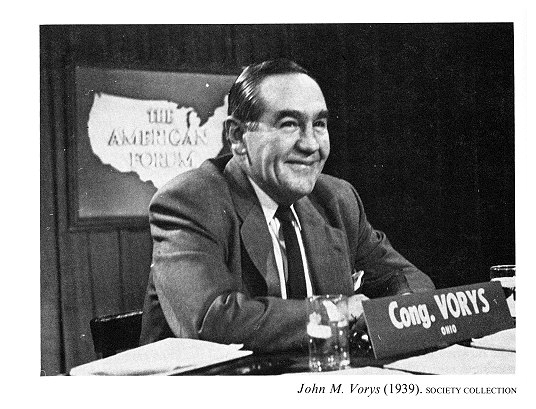

Ohio Representative John M. Vorys

and the Arms Embargo in

1939

During the last few years, Congress

increasingly has favored a reduction in Ameri-

can commitments to foreign nations. This

action has reversed a long-standing pol-

icy of globalism stemming from World War

II. Congress probably has not wit-

nessed such widespread

noninterventionist sentiments since shortly before World

War II, when the legislative branch

refused to repeal the arms embargo or permit

munitions sales to belligerent nations.

Numerous historians have analyzed the con-

troversial attempt to repeal the arms

embargo at the regular 1939 session, but have

devoted surprisingly little space to the

significant role of freshman Republican John

M. Vorys of Ohio in leading a determined

movement to cling to the bastions of non-

interventionism.' This study

investigates the crucial role played by this Ohio Con-

gressman in preventing Congress from

removing the arms embargo before the out-

break of World War II.

Vorys, a member of a prominent Ohio

family, rose quickly in the world of poli-

tics. The second of four sons, he was

born June 16, 1896, in Lancaster and began

his education in the public schools

there. His father, Arthur, who practiced law and

served as city solicitor of that upper

Hocking Valley industrial center, later joined

the law firm of Sater, Seymour and Pease

in Columbus. Arthur also served as a

State Superintendent of Insurance and as

a Republican national committeeman.

After the family had moved to the

capital city, young Vorys graduated in 1914 from

East High School and entered Yale

University. Following the outbreak of World

War I, he enlisted in the Naval Reserve

Flying Corps, saw action overseas as a

fighter pilot, and rose to the rank of

Second Lieutenant. Returning to Yale to earn

a B. A. degree in 1919, he taught the

next year in Changsha, China, and spent 1921

and 1922 as an assistant secretary for

the American delegation at the Washington

Naval Disarmament Conference. Vorys

received a law degree in 1923 from Ohio

State University and joined his father's

firm. He then began dabbling in politics,

serving in 1923-24 as a representative

from Franklin County in the Ohio General

Assembly and sitting the next two years

for the Tenth District in the Ohio senate.

An aviation enthusiast and author of an

article on airplane supervision, he was ap-

1. The most comprehensive work on

neutrality revision is Robert Divine, The Illusion of Neutrality

(Chicago, 1962).

Mr. Porter is Assistant Professor of

History, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York.

|

pointed in 1929 as Ohio's first Director of Aeronautics and then resumed his private law practice.2 After Democrat Franklin Roosevelt entered the presidency in 1933, the conserva- tive Vorys became increasingly disenchanted with events in the nation's Capitol. He disliked the growing tendency of the Federal Government to infringe upon states' rights, protested the rapid growth of executive power under a Democratic President, and consistently disapproved of Roosevelt's New Deal programs. A critic of Roosevelt's pro-labor policies, he opposed the Wagner Act of 1935 estab- lishing collective bargaining, favored an investigation of the National Labor Rela- tions Board, and advocated reducing funds for the Works Progress Administration and other federal relief agencies. In addition, he denounced the President's at- tempt in 1937 to enlarge the Supreme Court.3 Impatient at remaining on the sidelines, Vorys aspired to holding a national elec- tive office. He capitalized in 1938 on what the New York Times classified as a "ti- dal wave of anti-New Deal and anti-CIO sentiment" in Ohio and captured a seat in the United States Congress as a Representative from the state's Twelfth District (Franklin County). Ohio Republicans fared remarkably well in the 1938 elections, as John Bricker and Robert A. Taft replaced Democratic incumbents for governor and United States Senator, respectively, and nine other Republicans joined Vorys in unseating Democratic Congressmen. Shortly after the Seventy-sixth Congress con-

2. U. S. Congress. Biographical Directory of the American Congress, 1774-1961 (Washington, 1961); "John M. Vorys," Current Biography, 1950, p. 588. 3. For these views, see folders on the subjects in Boxes 3 and 4, John Vorys Papers, Ohio Historical Society. There is no biography of Representative Vorys. |

John M. Vorys 105

vened in January 1939, Vorys joined the

prestigious Foreign Affairs Committee and

worked hard in his new position.4

Congressman Vorys rapidly won popularity

among a majority of his Franklin

County constituents. Representing

farmers, businessmen, and many employed in

state government and at the educational

institutions in the county, he was reelected

easily in November 1940, and even

returned 25 percent of his campaign funds to the

donors. His supporters generally

criticized the tendency of the New Deal to favor

organized labor over big business,

protested the rapid expansion of the Federal

Government bureaucracy, and believed

that the 3,000 mile Atlantic Ocean ade-

quately protected the United States from

any foreign invasion.5

Between 1918 and 1938, the United States

had pursued largely isolationist poli-

cies. Preoccupied with the economic

depression, Congress had concentrated on do-

mestic affairs in enacting relief,

recovery, and reform measures to eliminate the ling-

ering unemployment problem. In foreign

affairs, a Senate committee, headed by

isolationist Republican Gerald Nye of

North Dakota, charged that bankers and mu-

nitions makers had drawn the United

States into World War I for financial profits

and drafted numerous proposals designed

to prevent American involvement in any

future war. Revisionist scholars and

journalists also denied that American security

had been at stake in World War I and

cautioned that interventionist actions should

be avoided in the future. In response to

these pressures, Congress approved the

Johnson Debt Default Act of 1934

prohibiting loans to any foreign country default-

ing on debt payments, and between 1935

and 1937 enacted a series of neutrality

laws preventing the United States from

exporting arms, ammunition, and imple-

ments of war to any belligerent country.

All warring nations wishing to purchase

non-military goods in the United States

were required to pay cash for such items

and to transport them in their own

vessels.6

By late 1938 the Roosevelt

administration began advocating a revision of isola-

tionist policies. After Hitler pledged

to Great Britain and France at the Munich

Conference of September 1938 not to seek

any additional European territory, the

German dictator within two months

intensified both Nazi rearmament and per-

secution of the European Jews. In

response, Roosevelt promptly requested $300

million for national defense and

recalled the American ambassador to Germany,

Hugh Wilson; State Department officials

recommended that Congress revise the ex-

isting neutrality laws at the next

session by repealing the arms embargo and placing

all trade on a cash-and-carry basis. In

his annual message to Congress in January

1939, the President complained that

American neutrality laws "may actually give

aid to an aggressor and deny it to the

victim." He also intimated that he favored

neutrality revision, but did not make

any specific recommendations about legisla-

tion and left the issue in the hands of

Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chair-

man Key Pittman of Nevada.7

Pittman, however, delayed acting on the

neutrality question for over two months.

Besides being more interested in western

silver legislation than in foreign affairs

4. New York Times, November 1938;

Current Biography, 1950, p. 588; John Vorys to Author, May 2.

1968. For election, see Milton

Plesur, "The Republican Comeback of 1938," Review of Politics, XXIV

(October 1962), 525-562.

5. For constituent views, see Boxes

3 and 4, Vorys Papers.

6. See John Wiltz, In Search of Peace: The Senate Munitions

Inquiry, 1934-1936 (Baton Rouge,

1963); Warren Cohen, The American

Revisionists (Chicago, 1967); Divine, Illusion, 81-228.

7. Robert Divine, The Reluctant

Belligerent: American Entry into World War II (New York, 1965),

55-57.

106 OHIO HISTORY

measures, the moderate internationalist

did not press for action principally because

isolationists controlled the Senate

Foreign Relations Committee. Roosevelt also re-

mained silent on the issue until German

forces on March 15 suddenly violated the

Munich Pact by conquering all of

Czechoslovakia. The President then publicly

urged Congress to act, prompting Pittman

on March 20 to introduce a bill repealing

the arms embargo and putting all

commerce on a cash-and-carry basis. Pittman's

Foreign Relations Committee again

disappointed the President by holding lengthy

hearings from early April to mid-May and

by failing to reach any agreement on

neutrality, thus letting the cash-and-carry

provision expire on May 1.8

The German annexation of Czechoslovakia,

meanwhile, alarmed Great Britain

and France. British Prime Minister

Neville Chamberlain, who had made territorial

concessions to Hitler at the Munich

Conference, particularly was dismayed by the

latest German action and indicated for

the first time determination to stand up to

the Nazis. Fearing that Poland might be

the next target of expansion, Chamberlain

on March 30 promised that Great Britain

and France would provide assistance to

the Polish Government in case Hitler

attacked that East European nation. The

guarantee, though, meant little in

reality because Great Britain and France would

face geographical barriers in providing

direct assistance to Poland and lacked mili-

tary personnel to open up a second front

against Hitler.9

Congressman Vorys, meanwhile, strongly

favored continuing American neutrality

policies toward Europe. Besides claiming

that European developments did not en-

danger American security, he insisted that

the 3,000 mile Atlantic Ocean would pre-

vent Germany from launching an effective

air or land assault upon the United

States. Protesting that New Deal

programs had enhanced Roosevelt's power con-

siderably, he hoped to maintain strict

congressional control over the President's

movement into European affairs. The Ohio

Republican particularly opposed

granting Roosevelt broad authority

either to determine aggressors or to sanction the

selling of arms to belligerent nations

in Europe because such leeway would permit

him to declare war, a privilege which

the Constitution specifically gives to the legis-

lative branch.

With bitter memories of the World War I

experience, Vorys hoped to avoid a re-

currence of similar American involvement

in future European affairs. In addition

to stressing that the United States had

spent $33 billion and suffered 116,000 deaths

in the conflict, he asserted that the

American crusade to save the world for democ-

racy had not prevented the rise of

European dictatorships. A midwesterner sus-

picious of the influence of the eastern

establishment upon the Federal Government,

the Ohio Republican alleged that bankers

and munitions makers had drawn the

United States into World War I for their

financial profits against American interests.

Vorys feared that idealism and

profiteering might embroil the nation in another Eu-

ropean conflict, leaving similar

legacies of massive spending, heavy casualties, and

unfulfilled ambitions.10

On the other hand, Vorys had no sympathy

for Hitler or Mussolini. He criticized

the Axis leaders for pursuing

dictatorial tactics and violating fundamental individ-

ual liberties, and particularly for

promoting themselves as peacemakers. "Hitler

8. Fred Israel, Nevada's Key Pittman (Lincoln,

1963), 131; Divine, Illusion, 241-251.

9. Divine, Reluctant Belligerent, 63-64.

10. For Vorys' views on foreign policy, see

Boxes 3 and 4, Vorys Papers.

John M. Vorys 107

has the ability," the Congressman

contended, "by eloquent and plausible mis-

statements of fact, law and history, to

convince his own people that he is peaceful

when he isn't, truthful when he

isn't." Although acknowledging that Hitler might

attempt to move into Western Europe,

Vorys intensely desired to keep the United

States out of foreign wars, opposed

taking punitive action against Hitler, and in-

sisted that "we have no assurance

that the threat of our force will be sufficient to

stop war."11

From the outset, Vorys criticized three

specific Senate proposals for changing the

neutrality laws toward Europe. Opposed

to allowing the President "a free hand in

assisting France and Great

Britain," Vorys denounced a controversial amendment

proposed by interventionist Elbert D.

Thomas (Democrat-Utah) designed to

empower the Chief Executive to send arms

and raw materials to attacked nations.

The Thomas amendment specifically was

designed to assist China, but Vorys

warned that it "might affect some

other situation we haven't thought of." On the

other hand, he disapproved of a proposal

sponsored by isolationists Gerald Nye

(Republican, North Dakota), Joel Bennett

"Champ" Clark (Democrat, Missouri),

and Homer T. Bone (Democrat, Washington)

to remove existing neutrality legisla-

tion and to return to traditional

principles of international law. Finally, he criti-

cized the portions of the Pittman bill

intended to repeal the arms embargo. Vorys,

though, liked certain features of that

bill, especially the sections preserving the exist-

ing neutrality law and prohibiting the

President from defining an aggressor.12

Even though Europe seemed more important

to the administration, Vorys pre-

ferred more active American responses on

the Asian front. Following in the Re-

publican tradition, he warned, "our

interests are not involved in Europe the way

they are in the Orient" and claimed

that Japanese expansion in Asian countries

posed a greater threat to American

security than did German or Italian activity at

that moment. Vorys contended that Japan

had disobeyed the Nine Power Treaty

of 1922, which outlawed aggression in

the Far East, by attacking China in 1937 and

by establishing puppet regimes in Inner

Mongolia, North China, and Nanking. He

remarked, "We have no treaty in

Europe comparable to the nine power Pacific

treaty that is being violated daily,

with increasing affrontery."13

In practical terms, the Ohio Republican

urged that the United States cease imme-

diately shipping scrap iron, oil, and

other war materials to Japan. An arms em-

bargo, Vorys insisted, would force Japan

to stop attacking China within six months

and would aid American defense policy by

"preventing a possible triumph of a fu-

ture potential enemy in the

Pacific." If munitions sales to Japan were terminated,

Vorys contended that Congress would not

be surrendering additional authority to

11. Vorys to Joseph McGhee, September

26, 1939, Box 3. Vorys Papers; Congressional Record, 76

Cong., 1 Sess., 8151. For views toward

Hitler, see Boxes 3 and 4, Vorys Papers.

12. Vorys to Miss Elizabeth Jones, March

24, 1939, Box 3, Vorys Papers; Vorys to Mrs. Harold Kauf-

man, April 22, 1939, Box 4, ibid. For

Thomas amendment, see Congressional Record, 76 Cong.. I Sess..

1347. For Nye-Clark-Bone amendment, see

New York Times, March 29, 1939.

13. Vorys to Miss Ellen Benbow, April

28, 1939, Vorys to Charles Seymour, April 27, 1939, Vorys to

Members of the Foreign Affairs

Committee, June 3, 1939, Box 3, Vorys Papers. The Nine-Power Treaty

was an international recognition of the

Open Door in China, first stated by the United States at the turn

of the twentieth century. The United

States, Japan, Britain, France, China, Italy, Belgium, Holland, and

Portugal agreed to respect the

sovereignty and territorial integrity of China and to refrain from taking ad-

vantage of China's weakened position to

seek special commercial rights or privileges at the expense of

other signatory powers. The treaty did

not commit its signers to any kind of action if one of them vio-

lated the treaty. David Shannon, Between

the Wars: America, 1919-1941 (Boston, 1965), 51-52.

108 OHIO

HISTORY

Roosevelt because "the President

[already] has power to declare an embargo in the

Chinese-Japanese War."14

During April and early May, the freshman

Vorys received his official baptism on

the neutrality issue. He participated

actively in exploratory House Foreign Affairs

Committee hearings and interrogated

various witnesses, ranging from Congressmen

to pressure group spokesmen, who

typically detected flaws in the existing law but

usually refrained from supporting any

particular neutrality bill. In response to his

vigorous campaign for a "straight

out Japanese embargo," Vorys encountered a

stormy reception from most witnesses,

and lamented, "I am discouraged at the ex-

perts who say that this would be

provocative, bad economics, etc."15

In the meantime, President Roosevelt was

upset that Pittman's committee had

procrastinated on the neutrality issue

and turned to the House of Representatives

for assistance. At a White House

conference held on May 19, Roosevelt personally

urged prominent Representatives to

repeal the arms embargo by the middle of July

(when the British royalty were scheduled

to visit Washington) and prompted the

State Department to draft legislation

for House Foreign Affairs Committee Chair-

man Sol Bloom (Democrat, New York).

Within ten days Bloom proposed the State

Department measure to the

Democratic-controlled committee. The Bloom bill

sanctioned arms sales to belligerents,

permitted American ships to transport cargoes

abroad, authorized the President to

designate combat zones, and otherwise dupli-

cated the earlier Pittman proposal.16

With the President's measure directly

before the House Foreign Affairs Com-

mittee, Vorys became further embroiled

in the neutrality controversy. When

Bloom ordered the committee to conduct

hearings in early June on his measure,

Vorys engaged the chairman in tactical

warfare over which proposals should have

top priority. The Ohio Representative

did not favor giving immediate consid-

eration to the Bloom bill and demanded

that the committee first give attention to

various proposals designed to place arms

embargoes upon Japan. Bloom naturally

advocated quick approval of the State

Department proposal and, fearing that hear-

ings on the Japanese bills might take

several days or even weeks, used his authority

as chairman to prevent Vorys from

speaking in the committee. After failing to in-

fluence Bloom, Vorys wrote a candid

letter on June 3 to his committee colleagues

stating directly what he had not been

permitted to say in person:

I feel we are making a great mistake trying

to determine our possible conduct as to future

wars in Europe before we determine our

present conduct as to an existing war in the Orient;

we have let our excitement about what may

happen to our remote interests in Europe blind

us to what is now happening to

our immediate interests in the Pacific. We have no treaty in

Europe comparable to the nine power

Pacific treaty that is being violated daily, with increas-

ing affrontery. The people back home

don't want us to interfere in Europe; but they are de-

manding that we stop supporting Japan in

this uncivilized, immoral conquest that violates

our treaty rights and threatens our

national interests.

I do not insist on any particular bill

and am committed to no specific proposals, but I feel

certain that if we solve this immediate

Far Eastern problem first it will go far toward solving

14. Vorys to Jones, March 24, 1939,

Vorys to Seymour, April 27, 1939, Box 3, Vorys Papers.

15. U. S. Congress, House, Committee on

Foreign Affairs, Hearings, "American Neutrality Policy,"

April-May, 1939 (Washington, D.C.,

1939); Vorys to Kaufman, April 22, 1939, Vorys to H. Schuyler Fos-

ter, Jr., April 17, 1939, Box 4, Vorys

Papers.

16. Divine, Reluctant Belligerent, 58-59.

John M. Vorys 109

the rest of our international problems,

and that until we decide this immediate problem, we

cannot reach any very satisfactory

conclusion on the general problem... .

Committee Democrats, led by Chairman

Bloom and Luther A. Johnson of Texas,

seized the initiative from Vorys and

strongly defended a Europe-first policy. Fol-

lowing the approach advocated by the

Roosevelt administration, they asserted that

German and Italian aggression in Europe

posed a greater threat than Japanese ac-

tions in the Pacific to American

interests and advocated repeal of the arms embargo

to assist victims of Axis expansion in

Europe. They also hoped to aid Great Britain

and France in defeating Nazi Germany

before these countries were themselves

overrun. Exhibiting little concern about

increasing presidential power in foreign

affairs, the Democrats favored

designating authority to Roosevelt to discriminate in

favor of attacked nations and to discourage

potential aggressors from provoking

war. Since the administration controlled

fifteen of twenty-five seats, the committee

turned deaf ears to Vorys' pleas and

opened hearings June 5 on the Bloom bill as

scheduled.18

Unable to sway the committee to delay

hearings, Vorys vowed to cripple the

chairman's measure. The Ohio Republican

attempted to restore part of the 1937

Neutrality Act by introducing an

amendment to prohibit the export of arms and

ammunition to all belligerents. He again

encountered insurmountable resistance,

and blamed ultimate committee rejection

of the embargo on "the New Deal major-

ity." Vorys, falling a few votes

short (12-8) of preventing the committee from re-

porting the Bloom bill, promptly denounced

the action in a minority report. He

feared the President might commit the

United States to assist attacked nations mili-

tarily and denounced giving him

authority to declare combat zones. Cognizant of

Roosevelt's earlier attempts to dominate

Congress, Vorys warned colleagues, "We

should not evade our responsibility by

granting the President additional power" and

vowed to wage an intensive battle in the

House against the Bloom bill. Besides

planning to utilize extensive debate to

delay voting, he hoped to arouse American

public opinion so as to encourage

congressional defeat of the measure and to secure

House approval of amendments

"keeping us out of war entanglements with foreign

conflicts."19

Boldly challenging several veteran

Representatives, Vorys battled vigorously

against neutrality revision on the House

floor. Administration officials selected

Democrat Luther Johnson of Texas, an

effective debater, expert tactician, and excel-

lent organizer, to direct floor strategy

for the advocates of arms embargo repeal.

Also chosen was Majority Leader Sam

Rayburn of Texas, an industrious and

shrewd Representative, to assist in the

struggle for approval of the Bloom bill. In

another move, the administration wisely

persuaded Foreign Affairs Committee

Chairman Bloom to play a subordinate

role because he possessed only mediocre

speaking talents and often told off-beat

jokes at improper times.

17. Divine, Illusion, 266-268;

Sol Bloom, The Autobiography of Sol Bloom (New York, 1948), 233;

Vorys to Foreign Affairs Committee, June

3, 1939, Box 3, Vorys Papers; New York Times, June 6, 1939.

Republicans Fred Crawford of Michigan

and Hamilton Fish, Jr., of New York, along with Democrat

John Coffee of Washington had introduced

bills to place arms embargoes upon Japan.

18. See majority report of U. S.

Congress, House, Committee on Foreign Affairs, Report No. 856,

"Neutrality Act of 1939," June

17, 1939 (Washington, D.C., 1939).

19. New York Times, June 7, 8,

17, 1939; Vorys to Mr. and Mrs. John 0. Gockenbach, June 30, 1939,

Vorys to Henry Durthaler, June 14, 1939,

Box 4, Vorys Papers; House Foreign Affairs Committee Report

856, "Neutrality," 21-24.

110 OHIO

HISTORY

Although freshmen Congressmen rarely

steal the limelight, Vorys delivered a ma-

jor floor address on June 28 for the

noninterventionist forces, criticizing the pro-

posed repeal of the arms embargo as a

step toward involvement in European affairs

and cautioning "the way to peace is

not to promise or threaten to fight anybody."

Despite conceding that Roosevelt desired

to keep the United States out of bellig-

erent conflicts, Vorys warned "if

you threaten enough you get into war" and admon-

ished, "we should furnish to no

nation the means of murder in wartime." Greeted

with widespread applause at the end of

the speech, Vorys later explained, "Some of

the members told me that I was

persuasive because I didn't claim too much for my

position and didn't criticize too much

those who had other views."20

In hopes of outmaneuvering

administration forces, Vorys sought to rescue victory

from the throes of defeat. The Ohio

Republican adeptly assumed the offensive the

next evening by introducing his

committee amendment to prohibit the sale of arms

and ammunition to all belligerents, but,

in an attempt to attract support from some

vacillating Democrats, did not include

aircraft and other possible implements of war

on the embargo list. After the House

rejected this plan, Republican Hamilton Fish,

Jr., of New York, a Foreign Affairs

Committee colleague of Vorys, the same night

arranged a deal with wavering Democrats

and promised that he and other Republi-

cans would support the Bloom bill in

exchange for their approval of the Vorys

amendment. Several Democrats either

swallowed Fish's bait or left the floor tem-

porarily when he requested a teller

vote, thus enabling the House to reverse its ear-

lier decision and narrowly (159-157)

approve the arms embargo amendment.

Vorys understandably rejoiced over the

deal and the sudden turn of events which

temporarily negated the Bloom bill and

seemingly doomed the prospects for Ameri-

can military intervention in European

affairs.21

Although stunned, administration leaders

soon struck back with a rare parlia-

mentary device. Before crowded galleries

and a packed House floor, Luther John-

son surprised the Vorys forces the next

day by proposing, in effect, the removal of

the arms embargo amendment and thereby

nearly (180-176) defeated the con-

troversial restriction on munitions

sales. Visibly angered, Johnson forces increased

the drama by refusing to concede defeat

and by insisting upon a roll call to reverse

the outcome. Both sides expected another

close tally and watched the suspense in-

tently. Republican Clifford Hope of

Kansas remarked, "It is going to be a close

fight" because the

"Administration is straining every nerve to get this bill through,"

while Democrat J. Hardin Peterson of

Florida labeled the situation as "a tug of war

from the start." To the astonishment of most present,

however, Vorys' supporters

registered a smashing victory over the

bewildered administration forces and, ex-

ceeding even Vorys' wildest

expectations, easily (214-173) restored the arms em-

bargo.22

A formidable bipartisan coalition had

rallied behind the Ohio Republican's

cause. Over one-fourth of the Democrats,

afraid of being tabbed publicly as inter-

20. Divine, Illusion, 269;

"Washington Correspondents Name Ablest Members of Congress in Life

Poll," Life, March 20, 1939,

13-17; Congressional Record, 76 Cong.. I Sess., 8151-8152; New York Times,

June 30, 1939: Vorys to Edward Hume,

July 18, 1939, Box 4, Vorys Papers.

21. For developments, see Congressional

Record, 76 Cong., I Sess.. 8320-8321, 8325; New York Times,

June 30, 1939.

22. Congressional Record, 76

Cong., 1 Sess., 8502-8503, 8511-8512; New York Times, July 1, 1939;

Clifford Hope to Herman Rome, June 30,

1939, Legislative Correspondence, Box 150, Cliford Hope Pa-

pers, Kansas State Historical Society;

J. Hardin Peterson Newsletter, July 6, 1939, Box 20, J. Hardin Pe-

terson Papers, University of Florida

Library.

John M. Vorys 111

ventionist, followed the safer route by

supporting the Vorys amendment and were

joined by an overwhelming 95 percent of

the Republican Representatives. Vorys

promptly labeled the measure as

nonpartisan because "it would have been impos-

sible for the Republicans to have put

through the amendment for a modified arms

embargo without Democratic support"

and also since "distinguished Republicans,

such as [James W., Jr.] Wadsworth and

[Bruce] Barton of New York, spoke and

voted against it." Further

discounting political motivations, Vorys observed, "I

know of no measure that has come up

since I have been down here where there was

more searching of hearts and attempting

to vote our real convictions as to the ulti-

mate best way to keep America out of

war."23 As a result of

the sudden alliance, ad-

minstration forces again had failed to

remove the controversial restriction against

munitions sales or to sanction American

military assistance to belligerent nations.

Bolstered by their resounding victory,

the Vorys forces took even bolder steps.

Republican George H. Tinkham of

Massachusetts, an isolationist colleague of

Vorys, sought to send the measure back

to the Foreign Affairs Committee and thus

kill all efforts at the 1939 session to

repeal the arms embargo. But Democratic

whips reformed their shattered

batallions just enough (196-194) to reject the Tink-

ham proposal, as twenty-six of their

party members, who had voted for the Vorys

amendment, rejoined the administration

forces and turned the tide against the isola-

tionist forces this time.24

After the exciting maneuvering and

tallies, the House anticlimactically (201-187)

gave the seal of approval to the

modified Bloom bill. Vorys, thankful that numer-

ous Democrats had supported his embargo

amendment earlier, abided by Fish's

pledge and supported the revised

measure. He had made concessions regarding

munitions sales and presidential

discretionary authority, but actually had sacrificed

little because he already had appended

the arms embargo amendment and had suc-

ceeded in retaining most of the 1937

Neutrality Act. Republican Hope of Kansas

aptly summarized the situation for the

Vorys forces by remarking, "The bill, as

passed, was much less harmful than the

one which was originally introduced [be-

cause] the House adopted a number of

good amendments."25

In letters to constituents, Vorys portrayed

vividly the impact of the House out-

come. The Congressman considered the

approval of his amendment as a major

step toward keeping the United States

out of war and out of foreign alliances. He

particularly praised international law

experts and "the overwhelming majority of

just plain American people" for

facilitating the retention of the arms embargo.

Adamantly defending noninterventionist

policies toward European nations, he still

cautioned that the United States should

not sell any belligerent "things with which

23. Roll Call Data, 76th Congress,

Inter-University Consortium for Political Research, University of

Michigan; Vorys to Hume, July 18, 1939,

Box 4, Vorys Papers. For further substantiation of the biparti-

san nature of the neutrality issue, see

J. Wilburn Cartwright Washington Newsletter, July 3, 1939, Box

168, J. Wilburn Cartwright Papers,

University of Oklahoma Library. On the Vorys amendment, 61 of

225 Democrats, 149 of 156 Republicans,

and 4 of 6 third party members favored restoration of the em-

bargo.

24. Congressional Record, 76

Cong., I Sess., 8512-8513; New York Times, July 1, 1939. On the Tink-

ham vote, 35 of the 228 Democrats, all

156 Republicans, and 3 of 6 third party members favored re-

commital. Data, Consortium.

25. Congressional Record, 76

Cong., I Sess., 8513-1814; Hope to Stanley Esser, July 3, 1939, Box 150,

Hope Papers. On the final roll call, 193

of the 226 Democrats, 5 of the 156 Republicans, and 3 of the 6

third party members approved neutrality

revision. Data, Consortium.

112 OHIO

HISTORY

to kill each other." He advised

instead "of attempting to arm victims of aggressors

we ought to stop arming

aggressors"-meaning Japan.26

The Roosevelt administration, Vorys

contended, exaggerated the seriousness of

the European situation. He claimed that

American tourists returning from abroad

and stock market leaders both pictured

Europe as "apparently settling down to a so-

lution of her problems without war"

and that the only European war cloud he could

see appeared in "the American

newspapers." Besides doubting that the retention

of the arms embargo "would have any

substantial military effect on the situation in

Europe," Vorys quickly reminded

repeal advocates that the United States still could

furnish many supplies to belligerent

nations and promised that "if and when the

struggle in Europe becomes our struggle,

we will do our part."27

European events, Vorys maintained, still

continued to sidetrack congressional at-

tention from more critical Far Eastern

problems. He intensified his campaign to se-

cure House action on Japanese embargo

legislation and finally induced Chairman

Bloom to open hearings on July 18, but

complained that Secretary of State Cordell

Hull "intends to do nothing about

the Japanese situation at this time." To Vorys'

pleasant surprise, however, Secretary

Hull in late July seized the initiative from

Congress on the Japanese issue and

warned Japan the United States would termi-

nate the commercial treaty of 1911

within six months.28 The Vorys forces in the

House seemed to be gaining support for a

prompt consideration of the Japanese

threat. The executive branch, still

zealously campaigning for repeal of the arms

embargo, had lost another bruising

battle with the Vorys group. Roosevelt priva-

tely denounced the House action toward

Europe as "a stimulus to war" and

prompted Secretary Hull to complain that

the embargo jeopardized American

peace and security.

Alarmed by the state of affairs,

Roosevelt urged Pittman's Senate Foreign Rela-

tions Committee to reconsider the

neutrality question and even threatened to delay

congressional adjournment until

munitions sales were sanctioned to European na-

tions.29 Administration

advocates, though, fared no better in the Upper Chamber.

Several leading noninterventionists

conferred in early July, determined that at least

thirty-four members opposed selling

munitions to belligerents, and vowed to cam-

paign intensively for postponement of

neutrality revision "by every honorable and

legitimate means" including

filibuster. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee

on July 11, after shrewd

behind-the-scenes maneuvering by isolationist Democrat

Bennett Clark of Missouri, narrowly

(12-11) approved a motion to delay consid-

eration of all neutrality legislation

until 1940. Roosevelt still advocated immediate

action and summoned congressional leaders

to another White House conference on

July 18. According to Vorys, the

conference showed that Roosevelt had wanted a

chance to make "another of his

sabre-rattling speeches." A confrontation between

Secretary Hull and isolationist Borah of

Idaho broke up the meeting and doomed

any chances for revising the neutrality

laws. Congress, unaware that Germany was

26. Vorys to Mrs. Doris Foster, July 11,

1939, Vorys to Carl A. Norman, July 12, 1939, Vorys to S. P.

Bush, July 22, 1939, Box 4, Vorys

Papers.

27. Vorys to Bush, July 22, 1939, Vorys

to Hume, July 18, 1939, Box 4, Vorys Papers.

28. Vorys to Bush, July 22, 1939, Vorys

to Foster, July 11, 1939, Box 4, Vorys Papers; Cordell Hull, The

Memoirs of Cordell Hull (New York, 1948), I, 637-638; Herbert Feis, The Road

to Pearl Harbor (Prince-

ton, 1950), 23.

29. Elliott Roosevelt, ed., FDR: His

Personal Letters, 1928-1945 (New York, 1950), II, 900-901; Hull,

Memoirs, I, 646-649.

John M. Vorys

113

preparing to attack Poland, adjourned

within three weeks.30

In the 1939 session of Congress, Vorys

contributed substantially to the demise of

the arms embargo repeal forces. An

advocate of federal concentration on Far East-

ern problems, he lobbied extensively for

his arms embargo amendment in the For-

eign Affairs Committee, carried his

struggle to the House floor, made two important

floor speeches, and astonished some

colleagues by securing approval of his con-

troversial amendment. Historians may

debate whether Vorys or Fish played the

more dominant role in the fight for the

noninterventionists, but the neutrality

struggle definitely had brought a new

face to the forefront.

In the final analysis, Vorys left a

mixed record on the neutrality issue. Even

though he had been a member of Congress

for only a few months, the Ohio Re-

publican exhibited unusual leadership

throughout the conflict with the adminis-

tration, displaying an uncanny ability

to rally bipartisan support behind the nonin-

terventionist cause. He also correctly

warned about the gravity of the Far Eastern

situation and recognized more than most

Representatives the dangers posed both by

Japanese expansion and by American

insistence upon sending arms to aggressors.

Although fulfilling the wishes of many

Americans desiring to keep the United States

out of a European foreign war, Vorys

incorrectly assumed more popular backing for

nonintervention than actually existed on

this extremely controversial issue.31 While

invoking the consequences of World War I

as motivation for avoiding future Ameri-

can commitments to Europe, he also

underestimated the nature of the German

threat to Western Europe and the United

States.32 With Vorys and other isolation-

ists carrying the day in Congress, the

United States nearly waited too long before

sending military supplies to Western

European nations. As subsequent events

showed, Hitler was planning to attack

the Low Countries, France, and Great Britain

at the same time he was reassuring a

gullible world that his intentions were

peaceful.

30. Clyde Reed to William Allen White,

July 13, 1939, Box 222, William Allen White Papers, Library

of Congress; "34 in a Lair," Time,

July 17, 1939, p. 13; "Neutrality Bill," Newsweek, July

17, 1939, pp.

17-18; Divine, Illusion, 277-278.

Clark persuaded two conservative Democratic members, Walter

George of Georgia and Guy Gillette of

Iowa, the night before to vote for postponement of the neutrality

question. See T.R.B.,

"Politics at the Water's Edge," New Republic, August 2, 1939,

p. 360. For the July

18 White House conference, see Joseph

Alsop and Robert Kintner, American White Paper (New York,

1940), 43-44 and especially Warren

Austin Memorandum, July 19, 1939, Folder 10, Box 20, Warren Aus-

tin Papers, University of Vermont

Library. For the reaction of Vorys to the conference, see Vorys to

Bush, July 22, 1939, Box 4, Vorys

Papers.

31. One large group that favored repeal

of the arms embargo and was against the Vorys amendment

was the Franklin County League of Women

Voters. See Vorys to Mrs. Wilson Hoge, July 11, 1939 for

the Congressman's reprimand to the group

and his statement: "I derive considerable comfort from the

fact that my own views, which I reached

after months of hearings, study and discussion, are in accord

with the mass of ordinary Americans and

also the overwhelming majority of experts on international

law." Box 4, Vorys Papers.

32. Samples of Vorys' statements

indicating that he underestimated Hitler's threat to Europe appear in

a letter written on July 22, 1939 to S.

P. Bush: "I don't think that an arms embargo would have any sub-

stantial military effect on the situation in Europe. I

think the insistence for its repeal is for diplomatic

and political effect.... Europe is

apparently settling down to a solution of her problems without war ... I

believe that America can contribute more

to world peace by threatening to stay out of Europe than by

threatening to go in ... I think that

instead of attempting to arm victims of aggression we ought to stop

arming aggressors .. ." Box 4, Vorys Papers.

DAVID L. PORTER

Ohio Representative John M. Vorys

and the Arms Embargo in

1939

During the last few years, Congress

increasingly has favored a reduction in Ameri-

can commitments to foreign nations. This

action has reversed a long-standing pol-

icy of globalism stemming from World War

II. Congress probably has not wit-

nessed such widespread

noninterventionist sentiments since shortly before World

War II, when the legislative branch

refused to repeal the arms embargo or permit

munitions sales to belligerent nations.

Numerous historians have analyzed the con-

troversial attempt to repeal the arms

embargo at the regular 1939 session, but have

devoted surprisingly little space to the

significant role of freshman Republican John

M. Vorys of Ohio in leading a determined

movement to cling to the bastions of non-

interventionism.' This study

investigates the crucial role played by this Ohio Con-

gressman in preventing Congress from

removing the arms embargo before the out-

break of World War II.

Vorys, a member of a prominent Ohio

family, rose quickly in the world of poli-

tics. The second of four sons, he was

born June 16, 1896, in Lancaster and began

his education in the public schools

there. His father, Arthur, who practiced law and

served as city solicitor of that upper

Hocking Valley industrial center, later joined

the law firm of Sater, Seymour and Pease

in Columbus. Arthur also served as a

State Superintendent of Insurance and as

a Republican national committeeman.

After the family had moved to the

capital city, young Vorys graduated in 1914 from

East High School and entered Yale

University. Following the outbreak of World

War I, he enlisted in the Naval Reserve

Flying Corps, saw action overseas as a

fighter pilot, and rose to the rank of

Second Lieutenant. Returning to Yale to earn

a B. A. degree in 1919, he taught the

next year in Changsha, China, and spent 1921

and 1922 as an assistant secretary for

the American delegation at the Washington

Naval Disarmament Conference. Vorys

received a law degree in 1923 from Ohio

State University and joined his father's

firm. He then began dabbling in politics,

serving in 1923-24 as a representative

from Franklin County in the Ohio General

Assembly and sitting the next two years

for the Tenth District in the Ohio senate.

An aviation enthusiast and author of an

article on airplane supervision, he was ap-

1. The most comprehensive work on

neutrality revision is Robert Divine, The Illusion of Neutrality

(Chicago, 1962).

Mr. Porter is Assistant Professor of

History, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York.

(614) 297-2300