Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

RICHARD THEODORE BOEHM

Tod B. Galloway:

Buckeye Jongleur, Composer of

"The Whiffenpoof Song"

How did the music for Yale's famous

"Whiffenpoof Song" come to be composed by

an Amherst College grad in Central Ohio?

And how did the Columbus tune come

to be matched to a New Haven college

verse, thence grow to become a part of the

common heritage of the world of American

music?

The answers emerge from a varied skein,

starting with homesick British soldiers

serving in Victoria's India, tracing to

Central Ohio and the pastime talents of a col-

orful Columbus

judge-musician-entertainer, thence on to Connecticut through the

musical lives of five Yale University

students. Throughout the tangle, the mark of a

popular Buckeye musician is indelible.

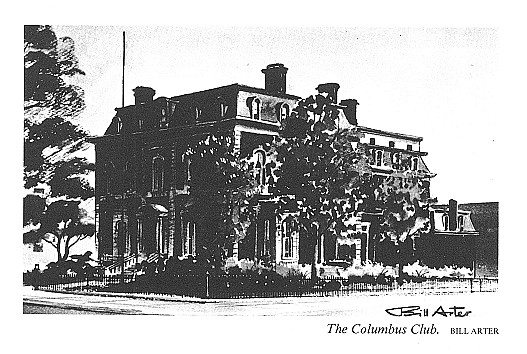

The threads all came together in Colum-

bus: the time was New Years Night, 1908;

the place, the Columbus Club.

The concert that evening by the Yale

Glee, Banjo and Mandolin Clubs was "the

best ever given here by a college

club," reported the Ohio State Journal. The per-

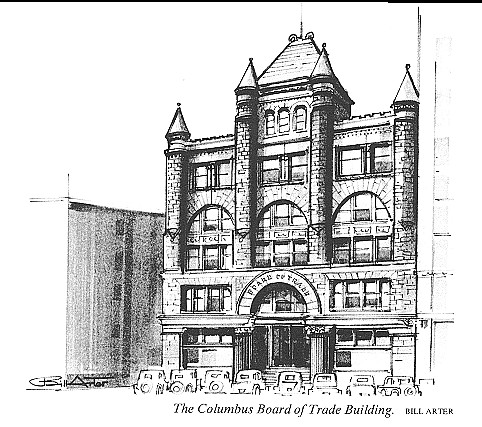

formance at the Board of Trade

auditorium was an enthusiastic success enjoyed by

a "large and fashionable audience.

. ." which included "the social element in large

numbers." The Journal methodically

set out a roster of thirty-seven "patronesses,"

alphabetically arranged; the list was

studded with family names from the upper

strata of Columbus society, many of them

with Yale connections.

The third number on the club program was

Tod Galloway's popular "Gypsy

Trail," composed more than ten

years earlier. It was sung by Yale's soloist, Phillip

Hamilton Collins, a senior from

Cleveland, who, the critic adjudged, had a "smooth

baritone voice of splendid quality, and

he was most successful with this song. It

was very well received, and Judge

Galloway, who was in the audience, must have

been very happy over its

reception." 1

After the concert, the glee clubbers

moved a couple of blocks east on Broad Street

to the Columbus Club (still today a

fashionable uppercrust club), where "a delight-

ful smoker" was sponsored by the

Yale alumni for the twenty-three choristers. Gal-

1. Ohio State Journal (Columbus), January 2, 1908. See also Columbus Evening

Dispatch, January 2,

1908; Yale Daily News, December

13, 1907. Galloway applied to himself the term "jongleur," which, he

said, was a medieval French word used in

France and Norman England. A jongleur was a minstrel who

traveled 'from place to place, singing

songs, often of his own composition and usually to his own accom-

paniment.' "The Trail of a

Jongleur," The Etude (February 1929), 95.

Mr. Boehm, a Columbus lawyer, certified

public accountant, and lecturer in law, has been a contrib-

utor to more than a dozen leading

technical journals.

|

loway, already credited with almost a score of published musical compositions, en- tertained the visiting songsters in his popular solo style. He played for them his own rendition of the refrain from Rudyard Kipling's "Gentlemen-Rankers." The Yale guests all joined in singing the words set to the Ohioan's catchy tune:

We're poor little lambs who've lost our way, Baa! Baa! Baa! We're little black sheep who've gone astray, Baa-aa-aa! Gentlemen-rankers out on the spree, Damnedfrom here to Eternity, God ha' mercy on such as we, Baa! Yah! Bah! They sang the chorus again, and they sang it yet again. One of the gleemen later re- counted for the record that three choruses were sung by the audience after Gallo- way had taught them the now-famous tune. The reprise from the Columbus Club still runs on, into the days of our years. The Judge's melody as the setting for Kipling's verse made a lasting impression on the young singers. When they got back to New Haven, five of the clubbers gath- ered to harmonize. Years later, "Caesar" Lohmann, baritone in the Varsity Quar- tette, one of the five founders of the Whiffenpoof Club, retold the Columbus story of "The Whiffenpoof Song":

The tune was suggested in a song sung for them by Tod Galloway, Amherst, '85, sometime Judge of Probate Court of Franklin County, Ohio. The original Whiffenpoofs had met him after a concert in Columbus which he attended because one of his compositions was on the Glee Club's program. Afterwards he entertained them by singing some of his unpublished songs, among them a setting of Kipling's Gentlemen Rankers. They remembered it with pleasure and in casting about later for an anthem, found it admirably suited for their pur- |

|

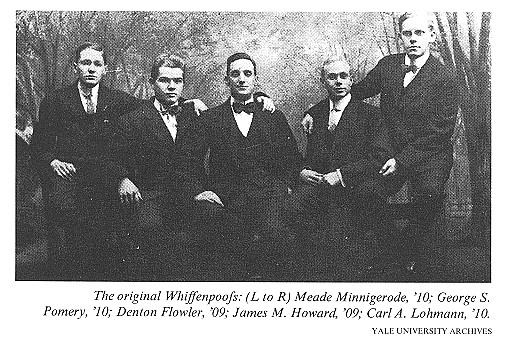

pose. The [Kipling] chorus needed only the change of a word-"rankers" to "songsters." 2 The five founding Whiffenpoof singers-all at Columbus that night-were Meade Minnigerode, George S. Pomeroy, Jr., James M. Howard, Denton "Goat" Fowler, and Carl A. "Caesar" Lohmann. Lohmann drew up a crude constitution for the club and a few simple membership rules. Monday at Mory's Temple Bar, at six, was fixed as the regular singing date. Thus a year later, in January 1909 was born the Whiffenpoof Club, and its anthem designated. Kipling's verse, Galloway's tune, Yale's traditions, the clubber's poetic revision and the captivating voices of the singers all combined to produce the popular college song which became a per- manent part of Yale life, its reprise perpetuated by generations of students who gathered each week to hear the Whiffenpoofs sing.3

2. Rudyard Kipling's Verse, Definitive Edition (New York, 1940), 422-423. Carl A. Lohmann, "The Whiffenpoof Song" from one segment of a large collection of materials about the Whiffenpoofs. Arnold G. Dana, comp., Yale Old and New (n.p., 1932-1943), L, available only in the reference department, Yale University Archives, Yale University Library. 3. All of the five singing founders of the Whiffenpoof Club were on the Yale Glee Club trip of 1907-1908 and presumably were in Columbus on New Years Day 1908. (There were two non-singing founders as well.) Two members, both of the Yale class of 1910, were the author of the Whiffenpoof verse: Meade Minnigerode (1887-1967), of Essex, Conn., later a prolific writer for such popular maga- zines as Saturday Evening Post, Colliers, and Ladies Home Journal, and author of a score of books, and George S. Pomeroy, Jr. (1888-1964), of Reading, Pa., later a tycoon of an eastern Pennsylvania depart- ment store chain. (These two received royalties as authors of the Whiffenpoof verse.) The other three founders included James Merriam Howard (1886-1971), Yale, 1909, a longtime Presbyterian clergyman, Carl A. Lohmann (1887-1957), Phi Beta Kappa scholar, LL.D., Yale, 1910, a native of Akron, Ohio, a World War I veteran, a lifetime career administrator, secretary of Yale University, and Denton "Goat" Fowler (1886-1910), Yale, 1909, who was killed by gunshot during a payroll robbery in 1910. Of his per- formance in Columbus, the Ohio State Journal said, "The hit of the evening was made by Mr. Fowler. Here is a young fellow who is a natural comedian, and if he ever happens to go on the stage he will be heard from." January 2, 1908; pamphlet, "A History of the Whiffenpoofs ... Prepared for the 60th An- niversary Celebration, February 22, 1969" (Yale University, New Haven, Conn., n.d. n.p.); National Cyclopedia of American Biography (New York, 1961), XLIII, 382. |

|

|

|

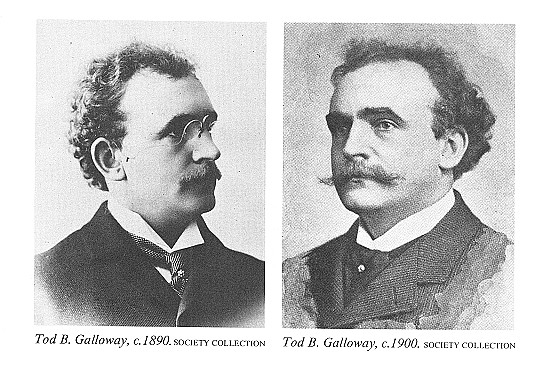

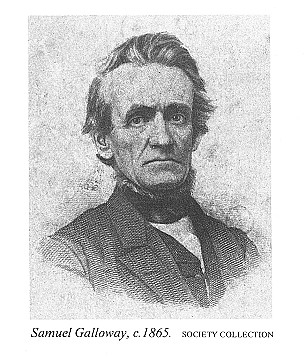

The young Whiffenpoofs were sure they had wrought well. Pleased by the magic of their singing, they set into their club constitution-and promised never to permit amendment-the euphoric command that "Whiffenpoof Song" be sung "all stand- ing" and that "under no consideration [may it] be sung at any other time or place." 4 The last vestage of this strict standard and tight monopoly disappeared thirty years later when Yale-grad radio star Rudy Vallee promoted the lovely tune, adorned with his own new arrangement, into radio's big time hit parades. The composer of the Whiffenpoof melody never guessed the climax of this tale. Judge Galloway died in 1935, seventy-two years of age. Not until the next year did the biggest things begin to happen to "Whiffenpoof Song." But what of the Buckeye singer? What manner of man was this handsome, dis- tinguished looking, entertaining, personable bachelor, he of the aristocratic pince- nez glasses and the lovely second-tenor voice? When came the muse which made him the ranking idol of the Columbus evening set? He was, as the saying goes, "quite a guy." Tod Buchanan Galloway came from demonstrably good stock. Two ancestors served in the American Revolution. His father, Samuel (1811-1872), of Scottish descent, was a cousin of President James Buchanan. Samuel graduated at the head of his class from Miami University at Oxford, studied law and theology, taught Greek and classical languages, was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1842. After two years of law practice in Chillicothe, he was elected secretary of state (1844-1850), whereupon he moved to Columbus. Galloway took pride that he had greatly ex- panded the work of the secretary's office in furthering the public school system. Elected to Congress (1855-1857), he participated as an antislavery Whig. De-

4. The Whiffenpoof constitution explicitly commanded that the words of the song be sung to the tune of "Gentlemen Rankers." Section I, article 4; Section II, article 6. The constitution in full is contained in the depositions in Miller Music, Inc. v. G. Schirmer, Inc., Equity Case E85-227, U.S. District Court, Southern District of New York; a full copy is on file, Tod B. Galloway Papers, Ohio Historical Society. |

|

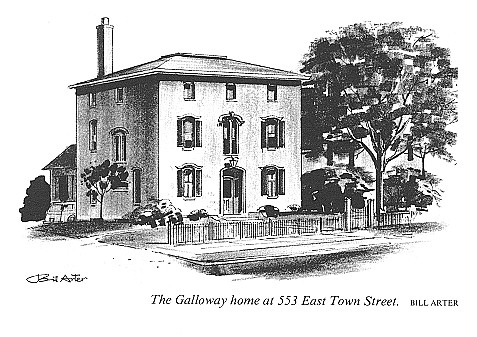

feated, he returned to the practice of law, campaigned for Abraham Lincoln, re- jected appointment to public office, although he served as judge advocate at Camp Chase and as secretary to Governor David Tod (1861-1863). In 1872 Galloway un- successfully sought the Republican nomination for governor. All the while a respected Columbus lawyer, Congressman Galloway was a recog- nized civic leader, trustee of Capital University, and in 1861 received an honorary LL.D. degree from Indiana University. It was said that he was an accomplished public speaker with a charming, witty platform manner. He developed Galloway, a village in Prairie Township, a few miles west of Columbus. A small cemetery and a county road near the village, a downtown Columbus alley and an eastside avenue still carry the Galloway name. The family lived at 553 East Town Street (near Par- sons Avenue, then East Public Lane) in a classic brick house built by Samuel in 1852, subject of one of the elegant Bill Arter Columbus Vignettes in 1966. Samuel Galloway died in 1872. He committed his "soul by faith to Christ my Redeemer and commended [his] family and friends to His precious love and care." The tall, imposing family tombstone in a stylish section of Green Lawn Cemetery boldly proclaims "Resurgam. "5 Ample resources were on hand to rear several or- phaned children and support his widow in a comfortable "carriage-trade" style. His not small estate included real property in Michigan and Louisiana, in Colum- bus, and in Prairie and Truro townships. Twenty-three years after he died, a ful- some eulogy of his career, along with special recognition as a founding member of Westminster Presbyterian Church, was preached and then published by Washing- ton Gladden, famed Columbus minister.6 Tod Galloway's mother had talent and ability which, he later said, had great ef- 5. Bill Arter, Columbus Vignettes (Columbus, 1966), [I], 84; first published in Columbus Dispatch, No- vember 21, 1965; Ella Lonn, Desertion During the Civil War (New York, 1928), 96. For a short treatment about this fascinating man, see "The Legacy of Bill Arter," Ohio State University Monthly (July 1973), 16. 6. Will of Samuel Galloway, Franklin County Probate Court, Will Record F (1872), 225; Washington Gladden, "Samuel Galloway," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly (1896), IV, 263-278. See also Biographical Directory of the American Congress, 1774-1961 (1961), 925; A Centennial Biographical History of Columbus and Franklin County, Ohio (Chicago, 1901), 184-187; and William Alexander Tay- lor, Centennial History of Columbus and Franklin County, Ohio (Chicago, 1909), I, 534-536. |

Tod Galloway 261

feet on him as a blooming youngster.

Born in Cincinnati, Joan Wallin (1821-1892)

was educated there at Stoughton's Young

Ladies Seminary. As a student, she ex-

celled in music and French. Shortly

after graduation, she served as a teacher in Dr.

Sanis' School for Young Ladies in

Hillsboro. One time when Samuel came to Hills-

boro to visit his sisters, in attendance

at the school, he met Miss Wallin. Her future

husband was ten years her senior; they

were married when she was eighteen.7

In his last years, Tod wrote with

evident pride about his mother's broad culture,

her fund of humor, her brilliance in

conversation, her fine French language and mu-

sical ability. Galloway's latter day

letter was also an apt description of their lovely

Italianate house and their way of life:

A large, square house with an ample ell.

A home of high ceilings, broad hallways and spa-

cious rooms, of big windows with

old-fashioned outside shutters and a broad winding stair-

way leading to an attic which covered

the entire third story. An attic where were numerous

bound volumes of old newpapers which

contained a rare delight-advertisements of Van

Amberg's Wonderful Show, Jenny Lind and

Tom Thumb, Smithsonian Reports, Perry's Ex-

pedition to Japan and the Exploration of

the Amazon River. Another place of delight was

the big, cool cellar with rafters hung

with strings of onions, peppers and all things so placed

for drying.

Around the walls were barrels of apples,

potatoes, molasses, vinegar, and cider; while a

generous swinging shelf held hams,

tongue and fresh vegetables from the farm. In one part

was a sunken place in the floor lined

with stone slabs where with fresh water, the milk and

cream could be kept cool and sweet. Ice

packed in sawdust was always kept in an icehouse.

This plenteous supply of provender was

indicative of the open-handed hospitality of the

home through which passed a constant stream

of guests-one day, the most distinguished;

the next, plain and humble. A United

States senator, often; and often visiting politicians, a

stump speaker or a county chairman....

Spacious grounds surrounded the house

filled with all kinds of trees, cedar, maple, silver

leaf poplar, fruit trees of all kinds,

including six apricots-a rare tree in central Ohio...

Then there was the generous barn or

stable near which stood the ash barrels where the soft

soap for the laundry was made. The

cow-barn-for no one depended upon dairies-and the

chicken yard were near by, for then

families had to be independent of butchers and bakers

and candle-stick-makers....

Columbus in the 60's and 70's was a

charming little city emerging from the Civil War. Its

broad trees, unpaved streets and

cobblestone gutters, its stone hitching posts and carriage

steps and its general air of hospitality

and manners made it seem quite Southern in charac-

ter. One evidence of this was the way

many of the ladies did their shopping. It was called

"carriage shopping." A lady

would drive in her carriage to the stores she frequented and

obliging clerks would bring out bolts of

silk, muslin, or whatever articles she wished to in-

spect-she not leaving her vehicle....

Sunday newspapers had not appeared but

religious papers such as the Herald and the

Presbyter and the Christian Union (later

the Outlook) were reserved for Sunday perusal.

There were always family prayers .... My

mother was broadly cultured with a fund of hu-

mor, brilliant in conversation on all

subjects, a fine French scholar and accomplished musi-

cian. I can well remember her

hand-copied books of thorough bass. When Oscar Wilde

was in this country in the late 80's he

remarked that next to Lady Stanley, my mother was the

most brilliant conversationalist he had

met.8

Tod Galloway was the youngest of ten

children, all Columbus bred, only five of

whom survived to reach adulthood. He was

born when his accomplished father

7. Gladden, "Samuel Galloway";

see also Ruth Young White, ed., We Too Built Columbus (Columbus,

1936), 101-102.

8. Ibid.

|

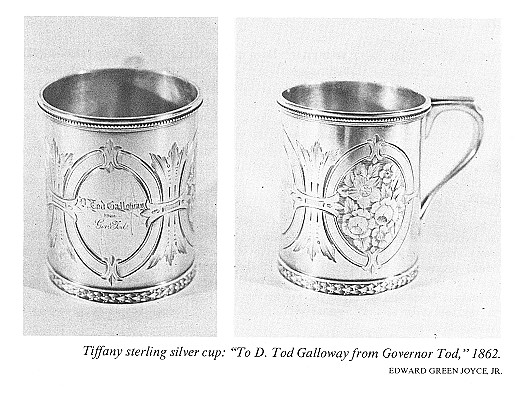

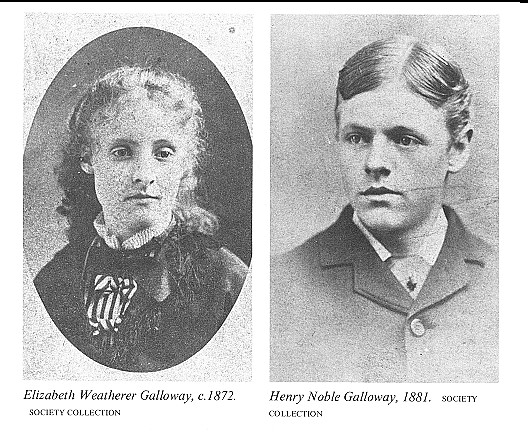

was fifty-two years old, when Congressman Galloway was serving as private secre- tary to the governor, who lived across the street. To celebrate the occasion, the in- fant was given a handsome sterling silver cup from Tiffany's of New York, beauti- fully decorated, inscribed "D. Tod Galloway from Governor Tod." The lad was not yet nine years old when his father died; he grew up with his mother, who had her own full cup of sorrow. A few months after Congressman Galloway died, Elizabeth Weatherer Galloway, the second daughter, died at age eighteen. The next year, John S. Galloway, the eldest son, almost twenty-two, freshly graduated from college, while visiting a new blast furnace in the southend, was badly mangled in an elevator accident. After a day of suffering, he died from his injuries.9 Henry Noble Galloway, the second son, named for a distinguished Columbus lawyer who later became his preceptor, was graduated at Amherst College in 1881, and the next year he was admitted to the Columbus bar. When his health failed, he moved in 1883 to Los Angeles to practice as an attorney and abstractor of titles, all the while hoping to regain his health in the California climate. An urgent message in 1887 from Henry's physician summoned Mrs. Galloway and Tod, newly home from Amherst, to Los Angeles. Henry's condition became much worse. The three started back to Columbus, but Henry died enroute, at Las Vegas, New Mexico, in May.10 Tod had followed his older brother, Henry, to Amherst. At college he formed a

9. Ohio State Journal, November 9, 10, 1873; the Tiffany cup is in the possession of Edward Green Joyce, Jr., of Columbus, grandson of Helen Black Joyce, Tod Galloway's niece. The Ohio Historical Society and the author are indebted to Mr. Joyce for his assistance and for making available numerous family photographs. 10. Ohio State Journal, November 9, 10, 1883; May 26, 27, 1887; Amherst College vita of Henry Noble Galloway (1858-1887). |

|

life-long friendship with a classmate, Frank Ellsworth Whitman (1862-1946), later a perennial class secretary, high-ranking business executive, still a helping friend forty years later. Tod's roommate was Clyde Fitch (1865-1909), who went on to become a leading American playwright. In his junior year, Tod went to New York with Fitch, on vacation, and managed to go to eleven plays in six days. They were both members of Chi Psi Fraternity at Amherst.11 Galloway later dedicated published melodies to both Whitman and Fitch. Graduated with honors in 1886, Tod returned to the family homestead. After reading law with Messrs. Nash and Lentz, distinguished Columbus lawyers, Tod, the second Galloway son to follow their father's profession, was admitted to the Ohio bar in 1888. He traveled in central Europe in 1892 and methodically put to- gether a hefty scrapbook collection of postcards. Practicing law with his preceptors from an office in the Board of Trade building, he also became Republican county chairman in 1893, and president of the Buckeye Republican Glee Club. Occasion- ally the club rehearsed at the family residence on Town Street. He became Colum- bus city councilman for the Seventh Ward (the "Silk Stocking Ward") in 1894-1895. "Judge," his complimentary title, and indeed a lifelong nickname, was earned dur- ing two terms as a Franklin County Probate Judge (1896-1904). As an extra activ- ity, he organized a traveling free library for the county schools in Franklin County and, in 1904, wrote to Andrew Carnegie, soliciting his interest in the project and a

11. For a biography of Frank E. Whitman, see National Cyclopedia of American Biography (1948), XXXIV, 537. That Galloway was Fitch's roommate was mentioned in one obituary. New York Times, December 16, 1935. |

|

major contribution for its support.12 His workaday career as a probate judge induced a stage hit in which he became an unwitting model. As a raconteur, the Judge told his college buddy, Clyde Fitch, then a New York playwright, about a juvenile who had come before the Probate Court. Fitch used the episode as the nucleus of a Broadway play, The Girl and the Judge (1901). This inspired comedians Joseph M. Weber and Lewis Maurice Fields to produce a comic parody called The Curl and the Judge. Fitch's chroniclers retold the story in detail: "The Girl and the Judge" was always called by Fitch his Taormina play, because most of it was written there; it was also called "Tod's play," because Judge Galloway had told him a court story which had come under his notice while he was a probate judge in Franklin County, Ohio. The plot was based on a human incident said to be the case of Ikey Einstein, probably a fictitious name. The incorrigible boy had been brought to court again and again

12. George Kilbon Nash (1842-1904) was governor of Ohio, twice attorney general, twice prosecuting attorney of Franklin County. Robert H. Bremner, "George K. Nash, 1900-1904," in The Governors of Ohio (Columbus, 1954), 136; Centennial Biographical History, 186-187. John Jacob Lentz (1856-1931), Columbia Law School, 1883, and admitted to the Ohio bar, 1883, practiced in Columbus with Governor Nash and (later) John Delano Karns, until 1915, when his job as president of the American Insurance Union effectively precluded daily general practice. He had earlier served as a Democratic representative to Congress (1897-1901). Biographical Directory of the American Congress, 1774-1961, p. 1211; Osman Castle Hooper, History of Columbus, Ohio (Columbus, 1919), 318-320; William S. Taylor, Ohio in Con- gress (Columbus, 1900), 310; Tod B. Galloway to Andrew Carnegie, January 28, 1904, Box 14, Herrick Letterbook, p. 43, Myron T. Herrick Papers, Ohio Historical Society. |

Tod Galloway 265

by his mother; she sought to have him

committed to a reformatory, one of her particular rea-

sons being that his conduct interfered

with her daughter's matrimonial prospects.

Ikey was an old offender in the

Children's Court, yet each time, when it came to the mo-

ment of sentence, the old woman would

weaken and beg him off. But one day, after a par-

ticularly harrowing plea to have him

"sent up," the Judge told the mother firmly that this

time Ikey must feel the full rigor of

the law. To this Mrs. Einstein readily agreed. So sen-

tence fell upon the boy's head; he was

lectured soundly by the Court and ordered to serve a

term in the Reformatory. The fat old

woman threw herself on her knees, to the astonish-

ment of the Judge, her body swaying back

and forth, and with outstretched hands, she cried

distractedly, "Oh, Ikey, Ikey! get

down on your knees and maybe you can soften the hard

heart of the Judge!"

This story particularly appealed to the

humor of Clyde Fitch, and he wrote to Judge Gal-

loway: "I have put you and your

Court into a play." But the central plot dealt with a klepto-

maniac mother of the "girl,"

the Judge being the hero.13

A major new period in Galloway's life

began in 1904 when, in January, he left the

courthouse and moved upstreet to the

Statehouse as personal secretary to Ohio's

Governor Myron T. Herrick, during a two

year term (1904-1906). From the first

week, Galloway was immersed in a

staggering volume of the governor's correspond-

ence, much of it merely trivial.

Patronage problems came soon and often; convicts

sought relief and were told to follow

normal channels; churches and charities seek-

ing handouts needed to be turned away;

and explanations were sent to excuse the

governor's inability to appear for

speeches. Galloway handled several dozen rail-

road passes for the governor's use in

those days before legal prohibitions stopped

this practice and rescued the carriers

from widespread patterns of shakedowns by

politicians. The secretary soon came to

feel secure enough to criticize Amherst Col-

lege, his alma mater, for failing to

recognize Clyde Fitch, and for being "entirely too

local in its recognition of her sons

.... Here in Central Ohio, we hardly ever hear her

name any more ... [but I am] devoted to

Amherst and its interests...."14

Three weeks after he moved into the new

job, Galloway received from Delevan,

Wisconsin, a letter from a lady

soliciting help for her father, a resident of Colum-

bus:

When I was quite a child one day, after

interpreting for my mother at the Court House, you

took me on your lap and said something

about my being a sweet child, then added, "If you

ever ask a man to marry you and he

refuses, come and ask me." Now, being satisfied with

teaching... I have not found any use for

what you said; but cannot it be turned in another

way? My father-a deaf man-wants a

position .... Wont you help? ... if you will just get in

a few words, Father will have the

position [as extra clerk] and I shall not have to take advan-

tage of your promise even if it is leap

year.15

The governor's secretary often covered

for his boss, making numerous speeches,

including appearances at the opening of

historical sites. Galloway also participated

extensively in the election campaign of

1905. One of his campaign arrangements

13. William Clyde Fitch (1865-1909) was

said to be "America's most successful playwright." Mon-

trose J. Moses and Virginia Gerson, Clyde

Fitch and His Letters (Boston, 1924), v, 207-208. On numer-

ous occasions, he had several hits

running at the same time. See also Dictionary of American Biography

(1958), III, 428-429; Montrose J. Moses,

The American Dramatist (Boston, 1925), 309. The Weber and

Fields parody was mentioned in Felix

Isman, Weber and Fields (New York, 1924), 280-284.

14. Galloway to Henry E. Whitcomb,

January 19, 1904, Box 14, Herrick Letterbook, p. 221, Herrick

Papers.

15. Letter to Galloway, January 20,

1904, Box 1, folder 3, ibid.

|

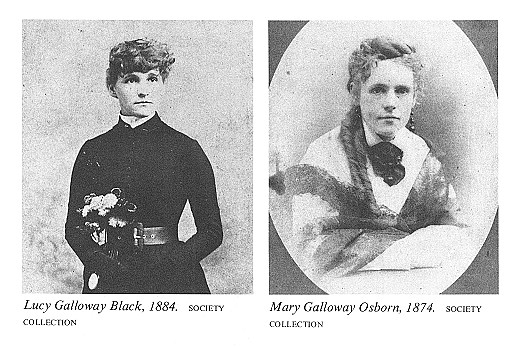

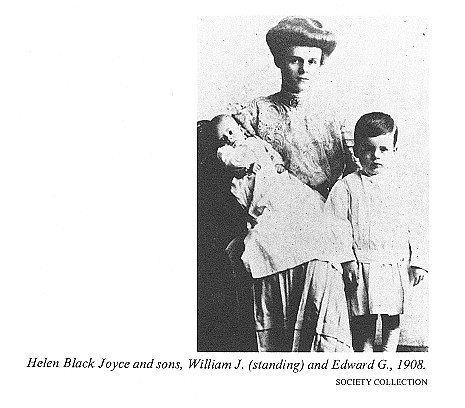

produced a free traction car for Herrick's use for political stumping in western Ohio.16 The governor, however, was defeated by John M. Pattison, a reform candi- date. When Herrick's term of office in the Statehouse ended in early 1906, Gallo- way returned to a lacklustre practice of law in Columbus. He served in business as the secretary of an insurance company. Four years later, in 1910, he went to New York. Galloway, dressy bachelor, ladies' man, scintillating singer, stage-center solo en- tertainer for thirty years, would have loved to tell his own story. He lectured, wrote dozens of serious articles, usually on music. He dabbled in history, loved to re- search the past, belonged to the Ohio Historical Society as a life member, to the Old Northwest Genealogical Society, the Sons of the American Revolution, to the Co- lumbus Club for twenty years, and to the Ohio Society of New York. But music was his main joy; he performed often, his own and anybody's. In later life, he put these all together and became an accomplished writer of articles on music history. Popular Judge Galloway lived in the old family residence with his gifted mother. When she died in 1892, her three remaining children promptly put the house into the name of Lucy Galloway Black, her second daughter. Thereupon Lucy and her husband, William, a railroad official, and their daughter Helen, returned from Chi- cago and took up residence in the classic homestead. The oldest sister, Mary Os- born, died soon afterward, leaving only Lucy and Tod surviving. For another dec-

16. Only two years later both the Federal and Ohio legislatures outlawed the free railroad pass for pub- lic officials. The Hepburn Act, 34 Stat 584 (1906), now 49 U.S. Code sec. 1 (7) (1952), and an Ohio stat- ute, 98 Ohio Laws 347 (1906), now Ohio Revised Code sec. 4907.30 (1953), forbid this practice. In the wake of the reform movement, the Interstate Commerce Commission rescued all the carriers from their less ethical competitors and the subtle pressures from men in public life. Colorado Free Pass In- vestigation (1913), Interstate Commerce Commission Report, XXXVI, 491. To the extent that railroad passes were considered to be political contributions, they were also forbidden by the Tillman Act of 1907, Public Law 59-36, 35 Stat. 864, now 18 U.S. Code sec. 610 (1972), by the Hunt Act in Ohio, 113 Ohio Laws 307, 400 (1908), now Ohio Rev. Code 3599.03 (1953), and by laws enacted in dozens of states. R. T. Boehm, "Taxes and Politics," Tax Law Review, XXII (March 1967), 369-438. |

|

ade Judge Galloway resided with Lucy's family, until 1902 when the Town Street house was foreclosed by a mortgage creditor. The Blacks' daughter was a handsome, teenage "daynty little ladye" (whom the Judge so complimented in a song dedication). Helen's close chum, Grace B. Kel- ton, a neighbor who lived in a stately mansion across the street came and went in the Black-Galloway household countless times. Miss Kelton remembered that, during her teenage days, Tod was at the upright piano a great deal of his time, sing- ing, playing, working on chords and progressions, phrases and verses, diligently composing melodies. Music for him came easy, Miss Kelton recalled as a non- agenarian, and he had a wide variety of selections. Galloway would play untiringly for his friends, and often just for himself, she said, and there was always music in the house. A cousin, related through Mother Galloway's family in Hillsborough, remembered the Galloways in the stylish Town Street manse: "Evenings I have sat in the old family library, listening to Tod Galloway trying his songs and melodies on the families and neighbors. His voice through the open windows was always a wel- come invitation. His audiences were many, and gay!" 17 The Judge wrote that he had no formal training in music theory or composition. He played piano by ear. Taking a likely verse from some well-known poet, he would patiently experiment till he produced his own musical setting for the words. The music for his two biggest hits-"Gypsy Trail" and "Whiffenpoof Song"-were arrangements using poetry by Kipling (with whom Galloway was slightly ac- quainted), a turn-of-the-century favorite. Other songs were based on verses chosen

17. Grace B. Kelton, born in Columbus, August 3, 1881, told us fondly that she was a neighborhood buddy, from childhood on, of Helen Galloway Black (1882-1957). "Keltons Stately Mansion," built by her grandfather, Fernandez Cortez Kelton (1812-1866), Columbus merchant, was the subject of an affec- tionate treatment by Bill Arter, Columbus Vignettes, 72. On November 29, 1974, Miss Kelton deeded the venerable residence, an 1852 jewel, for museum and cultural purposes. DB 3444, p. 285, Franklin County. Capital University plans to take over the day-to-day operation, subject to various contingencies. Samuel G. Hibben (1888-1972), a Galloway cousin, to Ben Hayes, Columbus Citizen-Journal, October 23, 1961, copy in Galloway Papers. |

|

from Shelley, James Whitcomb Riley, Lawrence Hope, Kendall Banning, Sara Teasdale, Austin Dobson, and Eugene Field, among others. But to ready a song for final manuscript, Galloway relied upon trained musicians to produce the formal publications, almost all handled through the Theodore Presser house, then of Phila- delphia. Invariably, he dedicated his published songs to a friend. Tod's chief loves were his sister, Lucy Black and her daughter, Helen. Lucy too was interested in music and dramatics as a performer. To each of them he dedi- cated a published song. Ben Hayes, current chronicler of Columbus citizenry, in 1958, reported nuggets gleaned from Helen Black Joyce about her uncle's ways: "He was the soloist at one time or another with every musical organization in town. But you would call him a parlor singer. Uncle John Taylor would play the piano, and Galloway would sing-that guaranteed the success of any party." 18 The musical history of Columbus is studded with reports of his activities. For the gala Franklinton Centennial Celebration of 1897, a notable exercise in organized civic nostalgia, he was chairman of the music committee and a member of the exec- utive and the invitations committees. He belonged to and performed repeatedly for the Women's Music Club. He sang with the Columbus Maennerchor for at least a decade, served on four committees of the fiftieth anniversary celebration, and was the featured toastmaster at the gala golden anniversary dinner in 1898.19 He di- rected Columbus plays and operas, lectured to music and literary clubs, sang tenor solos, and composed songs. Club notices indicate a wide variety of appearances

18. Ben Hayes Column, Columbus Citizen, December 28, 1958. 19. Galloway's picture and name appeared in the Golden Jubilee souvenir program of the Columbus Maennerchor (1898) and in the club's display pictures of 1898 and 1908. Maennerchor also published my short appreciation, "Tod B. Galloway," in the 125th anniversary publication, A Return to Yesteryear (Columbus, 1973), unpaged. |

|

|

|

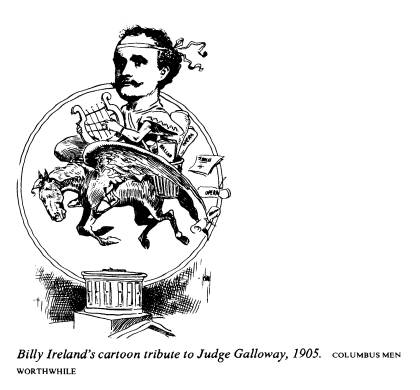

over a period of twenty years. In his last days, Galloway became a recognized member of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. In 1904, his accompanist was Elise Fitch Hinman, clubwoman and editor of the women's page of the Ohio State Journal.20 Galloway's activities attracted the praises of the Columbus press: Billy Ireland, fabled Columbus cartoonist, in 1905 published a complimentary cartoon. Johnny Jones, peddler of homespun nostalgia, wrote an adulatory paean in 1948; and Ben Hayes wrote a more sophisticated article ten years later. The Judge was so popular among the distaff set that, a quarter century after it happened, a Columbus lady still remembered that when Tod moved to New York, the ladies organized a party to be- moan his departure.21 Galloway's popularity in Columbus musical circles spread to the national scene. His national music reputation began as the consequence of a hearing in the Frank- lin County Probate Court, the Honorable Tod B. Galloway presiding. An aging lady had been brought before the Judge to determine whether she should be com- mitted to the hospital for the insane. The evidence did not support the proposal and the application was denied. Afterward, the defendant, a skilled musician, in gratitude, transcribed and arranged seven Galloway melodies for his first pub- lication. The lady, of whom this pleasant-ending story was later told by Galloway, took the initiative and got them published in Philadelphia in 1897 by Theodore 20. George S. Marshall (1869-1957) (mayor of Columbus, 1910-1911, longtime Columbus lawyer), The History of Music in Columbus (Columbus, 1956), 176. The Marshall list of appearances is far from com- plete. See also White, We Too Built Columbus, 101-102. Elise Fitch Hinman, to whom Galloway dedi- cated "My Brown Rose" in 1911, wrote the words for "Hurrah for Basketball," published locally in 1907. 21. Columbus Dispatch, December 5, 1948. Jones relied heavily on information furnished by Helen Joyce, Galloway's niece, who, Jones said, was "an exceptional beauty." Several inaccuracies can be ob- served in the Jones article. The Ben Hayes article was published in Columbus Citizen on December 28, 1958. See also White, We Too Built Columbus, 101-102. |

270 OHIO

HISTORY

Presser's leading music house. They were

released together as Seven Memory

Songs, characterized a half-century later by critic-historian

Sigmund Spaeth as "a

charming set." 22

"Gypsy Trail" (1897), one of

the seven, was based on Rudyard Kipling's classic

ballad. The song became a widespread

favorite, was acclaimed by Etude as "a

great success" along with the

"pronounced success" of other songs which came later.

Etude trumpeted Galloway's "extraordinary melodic

gifts." "Trail" became Law-

rence Tibbet's classic; the tune was

also used as a North Carolina college class song,

and in 1969 it was newly republished and

acclaimed as one of the Songs That

Changed the World.23

Galloway's second group of seven, called

Friendship Songs, were published in

1907 by Theodore Presser. Included in

this were "O Heart of Mine" (1905), based

on a verse by James Whitcomb Riley, and

"The Twenty-third Psalm" (1905), one of

the few plainly religious titles in his

known repertoire. His music was coming off

the presses for many years to follow.

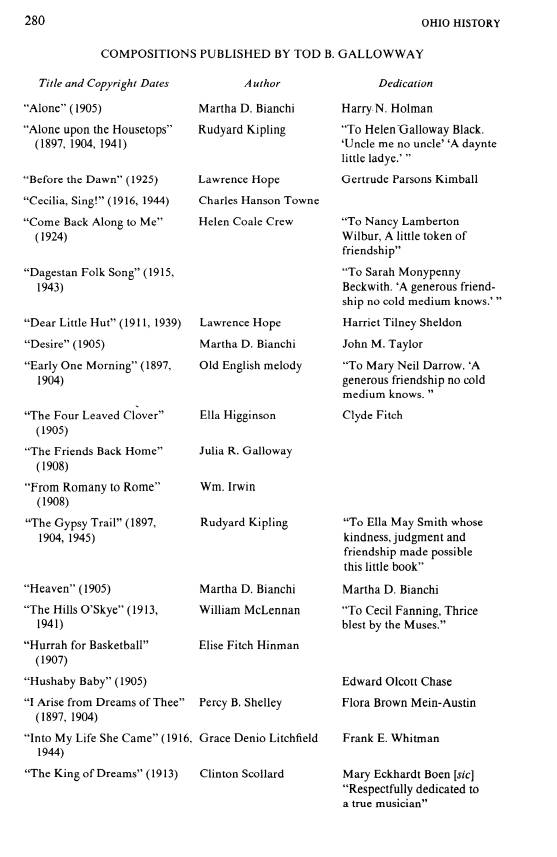

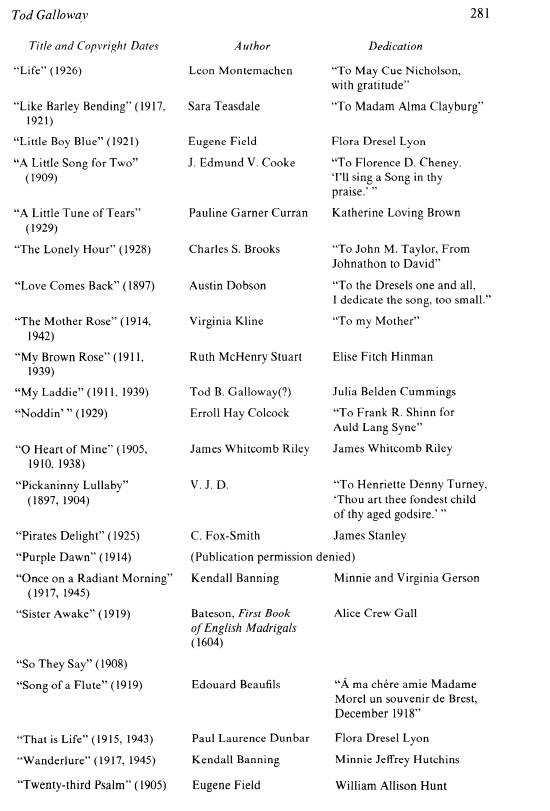

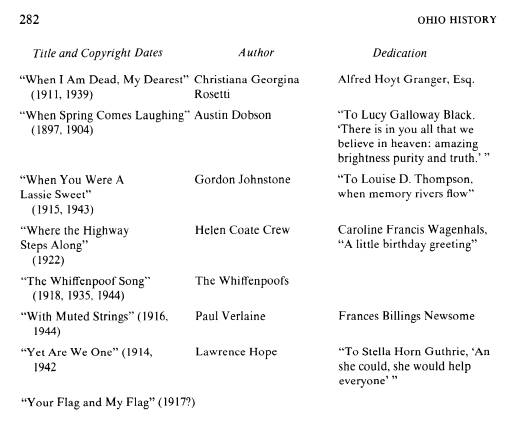

Fifty published numbers have been identi-

fied; in his obituary he is credited

with twice that many. (See the end of this article

for an alphabetical listing of

Galloway's published tunes.)

We know that Galloway's departure was

Columbus' loss, but we cannot establish

that his presence was necessarily a

distinct gain for New York City. The available

evidence does not tell us what happened to

him in Manhattan in the decade of the

'teens. There is a strong trace of his

presence in Philadelphia in 1912. Several mu-

sical compositions date from the period,

and his Amherst College vita inconclusively

says that he was practicing law in New

York and Columbus and that he served on a

draft board in World War I. Little other

proof of his whereabouts can be found ex-

cept the vague summary that he was

engaged in editorial work at the Macmillan

publishing house. What that means, we do

not know. But whatever, Tod had not

lost his personal touch; 1918 brought

another signal epoch.

America's entry into the World War in

1917 found Galloway in New York, fifty-

five years old, hardly a prime specimen

for enlistment as a combat trooper. After a

term on a draft board, he got himself an

assignment as a YMCA entertainer and

shipped overseas to the war zone, not

quite sure what his role was to be "over

there." He reached Brest early in

1918, traveled a bit and bubbled enthusiastically

about France in his letters to sister,

Lucy Black. Soon he reverted to type. A one-

man entertainment team, he talked, sang,

and played to soldiers everywhere-to

small groups in the trenches of

Champagne and Lorraine, to larger groups in the

rear areas, to crowds of men in

make-shift auditoriums-along a route two hundred

miles long, from the Channel to the

Vosges. Galloway's sentimental nature showed

up time and again in his songs and even

more in his letters to Lucy. His writings

show an explicit unabashed patriotism,

and a love affair with the American soldier:

"true American Knights of

Democracy," he called them. He puffed his pride in

them, his fellow countrymen, although he

had a somewhat curdled view of the

American officers: the soldiers

"are vastly more responsive and much more inter-

esting...." His letters told Lucy

that the doughboys got along well with the French

22. This summary has been drawn from

Galloway's own account: "The Romance of a Famous Song:

Judge Galloway's 'The Gypsy

Trail,'" The Etude (April 1920), 226; and Sigmund Spaeth, A

History of

Popular Music in America (New York, 1948), 573.

23. North Carolina State Normal

College Song Book (Greensboro, 1917), 20-21; Wanda Willson Whit-

man, ed., Songs That Changed the

World (New York, 1969), 94, 95. Kipling's poem, "The Gypsy Trail"

was published in the Inclusive Edition

of his works (1885-1932) (New York, 1938), 207-208.

|

|

|

poilus in spite of the language differences, and with the Canadians and the Aussies; but he said sadly, the American soldiers "cannot stand the [British] Tommies...." For their part, the soldiers seemed to have enjoyed Galloway. He sang them his own popular "Gypsy Trail" and "Your Flag and My Flag." He talked to them about the French countryside, its history, the lovely landmarks, "the poster bits of France." He enthused about the medieval towns, the old buildings and churches, the frescoes and wood carving. He reported to Lucy about "an interesting sub- terranean passage connecting the convent [of St. Bernard, built in 1056] with the old chateau of the Dukes of Burgundy .. ." And the soldiers seemed interested when he helped them find and understand the history behind the ancient Roman coins they uncovered while they were digging military trenches near Toul. He persuaded them to take their larger excavated stones, with Latin inscriptions, to the Musee nearby. His frequent letters to Lucy were censored, so he sent back to her, by a traveler, a code from which she could tell his whereabouts. Writing in a bold, shapely hand, he methodically numbered his own letters, most of them quite long, and carefully kept track of Lucy's letters to him, similarly serialized. Also pre- served is his postcard collection of scenes of his visits in France. At the front, Galloway moved often, sometimes several times a day, between en- tertainments. He required no band, no supporting cast, no arrangements, no phys- ical sets, but merely the means to move. Sometimes he moved on an army truck carrying an ancient French piano, occasionally on a continental railroad flatcar, equipped for the show. At the front he used a collapsible organ which, when |

272

OHIO HISTORY

folded, was no larger than a good-sized

suit case. This instrument, strapped on the

side of a faithful Ford, was put to use,

close to the trenches, whenever his soldier au-

diences could safely assemble, free of

the risk of enemy shelling.

His travels extended across the Western

Front, from Flanders and Piccardy to the

Alsatian Vosges, and back. He wrote Lucy

that the Commandant at the French

fortress at Verdun, scene of history's

longest, bloodiest battle, just two years earlier,

had given him a silver medal. His

travels were extensive: "Having been all along

the front," he said, "I am as

familiar with it as I am with High Street from Colum-

bus to Worthington." He was disappointed

because he did not get to perform for

the Ohio troops; one scheduled show at

the front lines during the crucial Argonne

campaign was spoiled because the unit

was suddenly moved off on a combat assign-

ment. And he marveled how the doughboys

could fight in the rough, tough country

of the Argonne forest. (This latter day

tourist, having recently retraced the area,

likewise marveled at the difficulty of

military maneuvers in the rugged countryside

at the Argonne front.)

French was not a language barrier. He

bragged to Lucy about his lingual ability

and was proud that the French soldiers

asked him to play and sing for them. Post-

ers in red and blue printing advertised

his coming: "Good morning Judge! Todd

[sic] B. Galloway of Ohio in a series of interesting tales

and talks. American

YMCA: The Best in Entertainment."

He also instructed the men in American his-

tory and translated some of his tunes.

He reported that converting into French his

two American Negro dialect songs,

"My Brown Rose" and "Pickaninny Lullaby"

for French audiences was a lost effort,

partially salvaged by their enthusiasm and re-

sponsiveness.24

During the 1918 show season, Tod played

at the front on the same program with

Elsie Janis, Columbus' own Elsie

Bierbower, the greatest favorite of them all, the

"sweetheart of the AEF." And he was pleased to report that noted

Homer

Rodeheaver, the "musical

missionary" associated with Evangelist Billy Sunday, had

learned Galloway's "O Heart of

Mine," had added it to his own repertoire, and fre-

quently used it in appearances with the

troops.25 "Judge" (as the soldiers called

Galloway) asked Lucy to look out for

syndicated news material about his efforts,

written by newsman Maximillian Foster in

August 1918.26 Le Jongleur showed

pride repeatedly in the applause and

approval of his audiences. He was pleased

that an officer had told him to sing

until he was hoarse, and was proud when the

troops demanded encores. His life with

the men was counted as "a priceless privi-

lege." With only a few days off, he

resented organization foul-ups which prevented

his daily performance for the troops,

his favorite people. His effusion of August 5,

24. This extensive paraphrase of

Galloway's activities in the front lines was drawn primarily from Gal-

loway's letters to his sister, Lucy

Galloway Black (1856-1942), married in 1880 to William Francis Black

(1851-1929). Galloway Papers. See also

Galloway, "Trail of a Jongleur."

25. Homer Alvan Rodeheaver (1880-1955),

"the musical missionary," born at Union Furnace (Hock-

ing County), Ohio, grew up in Jellico,

Tennessee, attended Ohio Wesleyan University. Famed as a con-

ductor of enormous groups of singers,

including choruses of 250,000, 150,000, 85,000, and 62,000, he be-

came a YMCA entertainer in France during

World War I and was associated with evangelist Billy

Sunday from 1909-1931. New York Times,

December 29, 1955; John Jasker Howard, Our American

Music (New York, 1965), 606, 611-612; National Cyclopedia

of American Biography (1962), XLV, 250.

26. Maximilian Foster (1872-1943), a

journalist, an author who later wrote for the Saturday Evening

Post. As official correspondent with the American

expeditionary force, he accompanied Woodrow Wil-

son during much of the President's

post-war sojourn abroad, leading up to the Treaty of Versailles. He

served as a reporter and writer on New

York newspapers, wrote ten novels, several plays and scenarios

for motion pictures. New York Times, September

22, 1943.

Tod Galloway 273

1918, would be a patriotic speech in any

language:

I cannot tell you with what joy I

welcome my going back tomorrow to be with the troops.

They are so wonderful. It seems as

though these things which the founders of our Republic

foresaw with prophetic views were coming

to pass.

And it is not because I am intensely

patriotic and American and therefore liable to over-

state and overestimate, but there is no

doubt about it that the fruits of this crop, grown by

those who had the Faith, are being

ripened right here in this awful war. You may recall that

early in March soon after I landed here

I wrote about the annealing we Americans must un-

dergo. They are undergoing it and all

the dross and sham is being burned away, and we as a

nation will be so much greater &

grander than we ever were before-& Our natural blow-

hardedness (if there is such a word)

being tempered by its contact with England and France

who have done such incomparable things,

will be sweetened and broadened and we will be

saner and more stable than we have ever

been before-& As to the development of our

Americanism along the lines as they

should be, I could write volumes. It is the daily in-

timate touch that I get that gives me

this absolute knowledge....27

This extravagant-perhaps unnoticed-mix

of metaphors and the absolutism of his

emotional judgments can be easily

embraced. Obviously Galloway's love affair

with the American soldier was only the

outward manifestation of much deeper emo-

tions which occasionally surfaced to

permanent visibility.

Life was quieter for Galloway after the

Armistice in November 1918. He stayed

a few months longer in France,

entertaining groups of transient men who were itch-

ing to get away, to get back home. He

managed to visit Morlaix, a tiny town in

Brittany, and wrote a lighthearted

travel article weighted with historical data about

the visit by Mary, Queen of Scots, to

the same place, 370 years earlier.28

The Galloway letter collection ends in

mid 1919, when the Judge presumably

went back to New York. We do not know

how far his performing talents extended

past his career in France. By the

mid-twenties, something caused a significant

change in his life style. The cause

might have been economic. By then Galloway

had passed sixty. We see no sign of

affluence. In the summer of 1925, he pur-

chased a new suit and paid for it by a

charge against his royalty account with Theo-

dore Presser, his publisher.29 The large royalties earned by

"Whiffenpoof Song"

would not begin for another ten years,

after his death. But he was back at his edito-

rial job with the Macmillan house and

this was the beginning of a prolific period of

writing on music history. He produced

several articles a year for the next decade

for the Etude, "The Journal

of the Musical Home Everywhere," published by Theo-

dore Presser. Several articles reached

print after his death.30 Besides his literary

work, two songs were published as late

as 1929, and several others earlier in the

decade.

Galloway's writing has a simple quality

that is akin to storytelling. His vocabu-

lary is adequate but not heavy, and the

language is supple and free flowing. His

work shows extensive research and

suggests also capacious classical reading and a

27. Galloway to Lucy Galloway Black,

August 5, 1918, Galloway Papers.

28. Tod B. Galloway, "When Mary and

I Went to Morlaix," Catholic World (July 1920), 494-502.

29. On June 9, 1925, Galloway signed a

request, addressed to Presser, to pay $50 to Frank E. Whitman,

his bosom friend of college days. For

the Union-Buffalo Mills Company, Whitman, treasurer and a high

ranking director of the company,

submitted the request for payment by a letter dated September 1, 1925.

Files, Theo. Presser & Co., Bryn

Mawr, Pa., copies in Galloway Papers.

30. One posthumous article was about

Heinrich Heine, "Great Poet as Music Critic," The Etude (Octo-

ber 1936), 626; another was a

re-publication of "Church Music Before Palestrina," ibid. (February

1938), 116.

274

OHIO HISTORY

retentive memory. He essayed

nontechnical articles about the technical part of mu-

sic: he wrote about the work of the

percussion drummer in the symphony and about

the family of woodwind instruments. He

enthusiastically acclaimed the work of the

conductor by way of an epigram:

"Temperament ... cannot be acquired by educa-

tion, hard work or favor. It is an

inborn free gift of nature. It is an endorsement of

the heart, not of the

understanding." 31

Or again, Galloway wrote about types of

music, about gypsy music, which was to

him, it is easy to detect, a subject of

some emotional interest. He described with

evident joy the music of the circus,

noting that he had fond memories of the tanbark

ring from his childhood, seen in the

company of his eldest sister. The ballet and the

waltz were the subjects of separate

articles, and he was fascinated by the evolution

of church music and its reformation

under Palestrina, the "Prince of Music." But

most often he wrote about musicians,

royal and common, ancient and recent, from

Old Testament days to nineteenth century

opera stars: about Beethoven, Men-

delssohn, Purcell, Rossini, Friederich

von Flotow, Offenbach, Allesandro Scarlatti, a

score of others, some unknown today.32

His historical writings were mostly

matter-of-fact, flavored all the while by his un-

quenchable love of music. In one

effusion, bachelor Galloway expressed a thought

about the special qualities of women:

"How very colorful, ever varied, never ending,

all embracing is the theme of the

inspiration to mankind of women.... Music is the

universal language. It begins life with

a cradle song; it ends life with a requiem.

What greater work can claim women's

attention? She always has been and always

will be, as long as human affections

exist, its [music's] inspiration ... she will be [its]

greatest interpreter."33

From his younger days on, he did well

with yet other types of literary efforts. As

a young lawyer, he was a banquet speaker

for the annual meeting of the Ohio His-

torical Society, his subject,

"Ohio's Congressmen During the [Civil] War." An even

more serious presentation was a

full-fledged article about the Ohio-Michigan

boundary dispute, not realizing that one

small remnant would persist, to be decided

by the Supreme Court in 1973. He edited

some of the papers of Columbusite John

Greiner who had been the first governor

of New Mexico Territory, but this minor

effort only indicated another direction

of his interest. During the Great War, he fo-

cused on Elizabethan history in the

article about his visit to Moraix, in Normandy.

Galloway's historical writings show

industry and ability, but they were only diver-

sions, pastimes for an active mind. In

the 1930's he broke into the toney world of

New England letters literate with an

article about a child prodigy who did not de-

velop into maturity. Two other articles

documented numerous endowments by

31. Galloway, The Etude: "Keep

Your Eye on the Drummer" (December 1930), 859, 906-907; "A Leg-

acy from Pan" (January 1932),

15-16, 57; "Why a Conductor?" (December 1928), 915-916.

32. Galloway, The Etude: "The

Irresistable Lure of Gypsy Music" (April 1926), 259, "The Music of

the

Tanbark Ring" (August 1932),

547-548; "The Story of the Ballet and Its Music" (October 1928),

745-746;

"The Music of the Waltz and Its

Creators" (August 1930), 541-542; "Church Music Before

Palestrina"

(February 1938), 116-117;

"Palestrina, The Prince of Music" (May 1935), 261-262; "The

Stabat Mater

and Its Illustrious Composers"

(October 1934), 577-578; "Music in the Bible" (March 1929), 185-186;

"Music Makers in the Day of Good Queen

Bess" (June 1932), 401-402; "Royal Musicians" (October

1931), 703-704, 745, 752, 757;

"Beethoven's Life Tragedy" (January 1928), 23-24; "The Romance

of

Mendelssohn" (August 1934),

459-460, 444; "The Divine Purcell" (May 1934), 288, 319; "The

Romance

of Alessandro Stradella" (July

1931), 475-476; "The Curious Story of Jacques Offenbach, The King of

Opera Bouffe" (July 1930), 469-470;

"What Music Owes to Allesandra Scarlatti" (April 1931), 245-246,

300.

33. Galloway, "Noted Women in

Musical History," The Etude (November 1929), 809-810, 855.

|

|

|

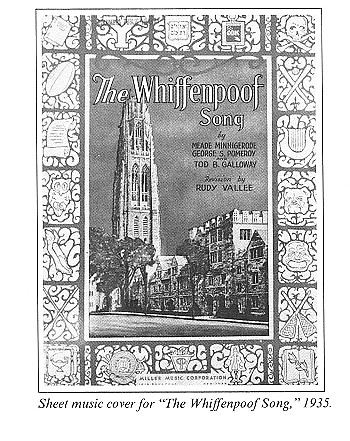

Theodore Presser for construction of college buildings to house their schools of mu- sic. Presser Hall at Ohio Northern University at Ada was one built in Ohio.34 By the time Tod Galloway died in 1935, the big story of "Whiffenpoof Song" had only begun. Generations of Yale men had come, sung the nostalgic verse, and re- membered the sentimental melody. (Cole Porter was a member of the elite Whif- fenpoof group in 1912-1913, and Lanny Ross in 1926-1928.)35 In the mid-thirties, Rudy Vallee of the crooners performed the song on radio, whereupon a gusher of royalties began to come in. The prospect of more income from the burgeoning favorite brought a 1937 Fed-

34. E. O. Randall, "Minutes of the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Ohio State Archaeological and His- torical Society," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, IV (1895), 446-448; Galloway, "The Ohio Michigan Boundary Line Dispute," ibid., 199-230. The line was finally fixed by the Supreme Court in 1973. Michigan v. Ohio, 410 U. S. 420, 35 L. Ed. 2d 397 (1973); Galloway, "Private Letters of a Govern- ment Official in the Southwest," Journal of American History, III (1909), 541. This was an edited collec- tion of letters written from New Mexico Territory between May 12, 1851 and October 30, 1852, by John Greiner (1811-1871), Indian Agent (1851) and Governor of New Mexico Territory (1852). (Greiner re- turned to Columbus in 1853). Galloway, "A Forgotten New England Prodigy," New England Quarterly, IV (July 1931), 515-524, is the story of Zerah Colburn (1804-1839), a mathematical genius from Cabot, Vermont, characterized as the eighth wonder of the world. See The Etude (September 1932), 620; and ibid. (October 1932), 697 for the account of the Presser endowments. 35. Cole Porter (1891-1964) was one of the Whiffenpoofs of 1912-1913. Composer of more than 500 published compositions, Porter is generally recognized as one of the top few American musical comedy composers. George Eells, The Life That Late He Led (New York, 1967), 40. For a photograph of Porter from Whiffenpoof days, see pp. 128-129. Lancelot Patrick Ross (b. 1906) (Yale, 1928), has been busy in radio and concert tours and has had his own shows. The ASCAP Biographical Dictionary of Composers, Authors and Publishers (New York, 1966), 625. |

276

OHIO HISTORY

eral court suit in Manhattan over the

copyright. In 1935, the copyright had been

assigned to Miller Music, Inc. by Meade

Minnigerode, George S. Pomeroy, and by

Tod Galloway's executor. The Vallee

version was challenged by G. Schirmer, Inc.,

who correctly stated that they had

published a "Whiffenpoof Song" in The New

Yale Song-Book in 1918. Based on this, Schirmer urged that earlier

publication,

standing alone, gave them rights

superior to the Miller Music copyright of 1935.

Miller, however, seemed to have the

better of the argument, based on their 1935 as-

signment of a formal copyright derived

from the legal grants from Galloway, the

composer, and from Minnigerode, and

Pomeroy, authors of the verse. The lawsuit

dragged on with little progress. Lawyers

went away on active military duty during

World War II. A fat file of

depositions about "Whiffenpoof Song," reported by

knowing people, was assembled and is

still available in the court records. After a

half-dozen years, the claim was finally

dismissed without trial, with Miller Music

still in command of the copyrights.

Concluded in 1945 by settlement, there was no

explicit court decision on the merits of

the conflicting priority arguments advanced

by the two publishers. The dismissal

order effectively validated the Miller copy-

right claims, and, in reliance,

thousands of dollars in royalties have since been paid.

The significance of the court proceeding

as to Galloway lies not in the determina-

tion of the copyright priority, which

was the precise legal issue between the two pub-

lishers, but primarily in the sworn

testimony of the origin of the music supplied by

the three living original Whiffenpoofs.

Detailed, signed, sworn depositions establish

that from the very beginning, they all

credited Judge Galloway as the composer of

the music of "Whiffenpoof

Song." 36

As if to challenge whether the original

Whiffenpoofs really knew, during the

1940's emerged a johnny-come-lately

claim that "Whiffenpoof Song" was not Gal-

loway's composition at all, along with a

charge that the Yale tune had been earlier

written and sung at Harvard, of all

places! But this version was at best a stale, un-

documented claim, unheard-of for thirty

years.37 Those three who knew best, they

who were in Columbus, had publicly sworn

that credit for the composition belonged

to Galloway. The thick record in the New

York Federal court establishes beyond

doubt-with nary a hint of difference-by

positive, detailed, contemporary court de-

positions from Minnigerode, Pomeroy and

Howard, supplemented by a published

essay by Lohmann, the fourth member,

that the tune had come from Galloway in

1908.

36. Three of the original five

Whiffenpoof founders of 1909, under oath in litigation, recognized Gallo-

way as the composer. "The words of

the last five lines of the song came from a poem by Rudyard Kipl-

ing and the music was composed by Tod

Galloway." Deposition of George S. Pomeroy (December

1944) (one of two authors of the words

of "Whiffenpoof"), p. 2. He also said that Meade Minnigerode

was the co-author of the words.

Minnigerode joined the other two in affirming Galloway's composition.

Deposition to Cross Interrogatories, p.

1, line 20, December 20, 1944. The testimony of James M. How-

ard was cumulative. Deposition, December

20, 1944, pp. 3-4. A fourth Whiffenpoof founder, Carl Al-

bert Lohmann, though not on oath, wrote

the same thing in the club's thirtieth anniversary pamphlet of

1939. Thus, by the end of 1944, all the

four living original Whiffenpoofs (Fowler had died in 1910) had

united in affirming Galloway's

composition. Miller Music, Inc. v. G. Schirmer, Inc., Equity Case

E85-227, U. S. Dist. Ct., S.D.N.Y.

(Copies of the key court documents and the depositions are on file in

the Galloway Papers.) N.B. Large

royalties have been paid to Galloway's heirs, undoubtedly in reliance

upon the legal effect of the court

proceedings.

37. The challenging claim to Galloway's

composition is based on the allegation by Carl B. Spitzer

(1877-1962) (Yale, 1899), Toledo

financier, that the Whiffenpoof tune was written by Guy H. Scull (Har-

vard, 1898), and used at Cambridge. This

late claim could never override the legal effect of the copy-

right, the credibility of the affidavits

on file in the court case, and the quieting effect of the court pro-

ceedings. Indeed, could such allegations

ever be credited, thirty-five years later, to offset the founders'

current (1909) knowledge to the

contrary? Carl Lohmann, "The Whiffenpoofs," 8.

Tod Galloway 277

These were the four living witnesses who

had been members of the Yale Glee

Club and had performed in Columbus that

New Years Night; it was they who

adapted their own New Haven words to his

old tune and altered Kipling's verse. It

was they who formed the now-famous

Whiffenpoof Club and tied it to the cele-

brated tune by their unchangeable

constitution. At no point in the long lawsuit was

there the slightest suggestion which

impugned the fact of Galloway's composition.

Whether Galloway may have elsewhere

picked up the idea for the melody (few

ideas are totally exclusive and

original) cannot be said or gainsaid. Whatever the

latter-day claims of others, they cannot

overcome the legal ownership of the music

based upon the testimony of the original

witnesses that it was Galloway who taught

the tune to the Yale men and, from the

first, was publicly credited with the composi-

tion.38

The composition of "Whiffenpoof

Song" is made up of three major evolutionary

elements. Galloway first took the words

from Kipling's "Gentlemen-Rankers," a

poem reflecting the predicament of

middle class English soldiers serving in Vic-

toria's India. This was just the first

step; and Kipling's "baa-baa" chorus is the only

original part still extant in the song.39

Galloway's music for the British verse was

the second element carried into today's

content; this was the memorable tune

brought back to New Haven from the

pleasant smoker at the Columbus Club. The

third ingredient came out of the

Yale-centered inspirations of Minnigerode and

Pomeroy, perpetuated in their own

colorful college verse:

THE WHIFFENPOOF SONG

To the tables down at Mory's

To the place where Louie dwells,

To the dear old Temple Bar we love so

well,

Sing the Whiffenpoofs assembled with

their

glasses raised on high,

And the magic of their singing casts

its spell.

Yes, the magic of their singing of

the songs

we love so well,

"Shall I wasting, "and

"Mavourneen,"

and the rest.

We will serenade our Louie

While life and voice shall last,

Then we'll pass and be forgotten with

the rest.

We're poor little lambs who have lost

our

way: Baa! Baa! Baa!

We're little black sheep who have

gone

astray: Baa! Baa! Baa!

Gentlemen songsters off on a spree,

Doomedfrom here to eternity,

Lord have mercy on such as we,

Baa! Baa! Baa!

38. A knowledgeable official of a large

music publishing house told me in 1973, viva voce, that many a

favorite popular song produces claims of

conflicting origin. In this, he said the "Whiffenpoof" challenge

278

OHIO HISTORY

But the words need interpretation,

replete as they are with arcane references.

The nonsense title was lifted from a

Victor Herbert musical, "Little Nemo," then

running on Broadway, in which Joe

Cawthorne, a Broadway comedian, popularized

the Whiffenpoof, a mythical fish-like

creature of which no reliable anatomical de-

scription has been located. Three unique

references import meanings not in-

telligible except to the initiate.

Generations of Yale students have hung around an

eating club called "Dear Old Temple

Bar," named after the New Haven street on

which it was located. The place had

acquired a nickname, "Mory's," a contraction

of the Moriarity family name, its early

proprietors who had started the eatery a

dozen years before the Civil War. And

the special serenade in the verse was to

Louis Linder (1866-1913), who had come

as an immigrant from Wurtemberg at age

fourteen and had been the properietor of

Mory's Tavern from 1898 until his death.

Louis had encouraged and applauded the

songsters in their efforts and so earned

their affection--and their

patronage--that he was named and still lives on as the

first honorary Whiffenpoof.40

Despite the esoteric content of the

verse, "Whiffenpoof Song" became a national

favorite, a well-known standard on

radio. In 1943 Moss Hart used it in Winged

Victory, the Army Air Force show, "a big and deserving hit

upon the [Broadway]

stage." The next year it was moved

into a "stunning production" movie of the

same name, by Twentieth Century Fox,

featuring Edmund O'Brien, Jeanne Crain,

and the Andrews Sisters. The tune has

been recorded at least thirty-five times by

an impressive collection of two generations

of America's musical greats. Bing

Crosby and Fred Waring collaborated in

one version which sold a million copies.

Louis Armstrong, Perry Como, the Norman

Luboff Choir, Les Brown, Montavani,

Lawrence Welk, Count Basie, the Mills

Brothers, Edie Adams, Jaye P. Morgan, and

Cal Tjader grace a long list of

distinguished performers.

The artistry of younger generations has

added new joys to the music; a sensuous

"triple-slide," a three-part

harmonic glissando in the best barbershop tradition, or-

naments the Martin Alexander (jazz

musician of Canton, Ohio) arrangement sung

by the Ohio State University Glee Club

and by the Columbus Maennerchor. A

five-part glissando by gifted, inspiring

Lowell F. Riley, adorns his delightful eight-

part arrangement for mixed voices for

the justly famous Vaudvillities chorus of Co-

lumbus, Ohio.

was not unusual. Infringement suits are

common to many successful songs; the claims are not neces-

sarily spurious, but are occasionally

arguable. Challenges to copyrights and their usual lack of founda-

tion is a ordinary event in the

industry. Only about one in ten has a reasonable claim to merit. He

guessed that these claims are the

inevitable result of widespread talent and interest in music. This crea-

tivity, he says, occasionally produces

compositions which have at least arguable claims of superficial

similarity.

39. The "baa-baa" chorus,

obviously drawn from Kipling's "Gentlemen Rankers," might well have

been the basis for a challenge by the

Kipling interests. Johnny Jones quoted Helen Joyce (Galloway's

niece) that the Kipling estate had

brought suit because the song was taken from the poem. Columbus

Dispatch, December 5, 1948. No other confirmation of this

litigation has come to notice. Information

attributed by Jones to Mrs. Joyce

reflects minor confusion in the history.

40. Carl A. Lohmann, "The

Whiffenpoofs." One non-Yale reference in the text of the new verse was

to the song, "Shall I Wasting in

Despair?" These words were suggested by lines from a "classic of Eng-

lish literature ...," written in

the middle 1600's. The special barbershop qualities of the melody were

explained by Sigmund Speath, Barber

Shop Ballads and How to Sing Them (New York, 1940), 77-79.

Mory's as a club has since been incorporated.

Its male exclusiveness was shattered by court orders to

accept female patrons and the club gave

up its three years fight to exclude women. New York Times,

March 30, 1974. It has since elected

four women to its Board of Governors. UPI dispatch, Columbus

Citizen-Journal, July 18, 1974.

Tod Galloway

279

Far from being parochial,

"Whiffenpoof Song" has gained international fame;

the words have been translated into

French and German, and royalties were said to

have been paid from Norway and Sweden.41

The tune has earned a fortune in roy-

alties, which are still averaging a

thousand dollars a month. Until her death in

1959, Helen Galloway Joyce, Galloway's

favorite niece, was still receiving thou-

sands of dollars in royalties from her

uncle's song. Her descendants still receive siz-

able remittance checks.42

Galloway returned home to Columbus in

1933, retired from his job at Macmillan

publishing house. His sister, Lucy

Black, widowed since 1929, lived in the old

neighborhood with her daughter, Helen,

who had been married in 1904 to William

J. Joyce, of the socially prominent

Columbus merchant family. Tod boarded

nearby with a family on Washington

Avenue. In July of 1935, he was injured in a

fall. After that, his health failed

rapidly, and by November, his nervous condition

had reduced his bold, shapely handscript

to a pitiable scribble. John M. Taylor,

who had been his accompanist in the old

days, was acting as his "agent in all per-

sonal and financial matters."

Taylor observed that Tod's signature was "almost il-

legible, owing to his extreme nervous

condition.... His condition is desperate and

I, as an old friend, am trying to smooth

the path, and to make him as comfortable as

possible." Taylor reported that

Galloway was pleased to give the Presser pub-

lishing house permission to use his

compositions in forthcoming publications, and to

see another of his articles in the pages

of Etude.43

Death came a few weeks later, on

December 12, 1935, to the "eminent lawyer,

musicologist, composer and writer,"

one of the most colorful characters that Colum-

bus has known in the last

half-century." Judge Galloway lies interred at Green

Lawn Cemetery in the family lot,

alongside his brilliant parents and near the graves

of a group of historic Columbus

families. His beloved sister, Lucy Black, lies

nearby, with her husband.

Galloway himself wrote our final lines.

The words of "Whiffenpoof," notwith-

standing, the magic of his singing is

not forgotten with the rest. His name shows up

in a sizeable number of periodical index

entries. His reputation is current, fre-

quently refreshed by his latter-day

admirer, Colubmus Citizen-Journal columnist

Ben Hayes. The most important part of

the Tod Galloway story cannot be printed:

it will be heard--and felt--where people

assemble, sing and listen. When the fi-

nal type has been set, it will be

Galloway's music that we shall recall, even after the

composer's name has escaped our memory:

Forgotten are the creators of the music,

workers with their struggles and triumphs. Their

works alone are remembered and

cherished--and will so continue--for music is

deathless.44

41. New York Times, December 21,

1944. In the movie version, at a Christmas party, three soldiers

burlesqued the singing of the Andrews

Sisters. They mimic voicelessly as the Sisters' voices were dubbed

in by a phonograph record.

42. Miller Music, Inc. to author, July

23, 1973, copy on file, Galloway Papers; Ben Hayes, Columbus

Citizen, December 28, 1958; telephone conversation with William

J. Joyce, Jr., St. Clair Shores, Mich-

igan, grandnephew of Tod B. G lloway;

August 1973.

43. John Myers Taylor to Theodore

Presser Co., November 5, 1935, copy in Galloway Papers. Taylor

occasionally acted as Galloway's

accompanist. His wife was Elizabeth Campbell, the "socially gifted"

daughter of James E. Campbell, governor

of Ohio (1889-1891), three-term congressman, former Middle-

town lawyer, veteran of the Union Navy

during the Civil War.

44. Obituary, The Etude (February

1936), 66; Columbus Dispatch, December 13, 1935; Galloway, "A

Queen and a Quarrel about

Musicians," The Etude (July 1928), 517-518, 553.

RICHARD THEODORE BOEHM

Tod B. Galloway:

Buckeye Jongleur, Composer of

"The Whiffenpoof Song"

How did the music for Yale's famous

"Whiffenpoof Song" come to be composed by

an Amherst College grad in Central Ohio?

And how did the Columbus tune come

to be matched to a New Haven college

verse, thence grow to become a part of the

common heritage of the world of American

music?

The answers emerge from a varied skein,

starting with homesick British soldiers

serving in Victoria's India, tracing to

Central Ohio and the pastime talents of a col-

orful Columbus

judge-musician-entertainer, thence on to Connecticut through the

musical lives of five Yale University

students. Throughout the tangle, the mark of a

popular Buckeye musician is indelible.

The threads all came together in Colum-

bus: the time was New Years Night, 1908;

the place, the Columbus Club.

The concert that evening by the Yale

Glee, Banjo and Mandolin Clubs was "the

best ever given here by a college

club," reported the Ohio State Journal. The per-

formance at the Board of Trade

auditorium was an enthusiastic success enjoyed by

a "large and fashionable audience.

. ." which included "the social element in large

numbers." The Journal methodically

set out a roster of thirty-seven "patronesses,"

alphabetically arranged; the list was

studded with family names from the upper

strata of Columbus society, many of them

with Yale connections.

The third number on the club program was

Tod Galloway's popular "Gypsy

Trail," composed more than ten

years earlier. It was sung by Yale's soloist, Phillip

Hamilton Collins, a senior from

Cleveland, who, the critic adjudged, had a "smooth

baritone voice of splendid quality, and

he was most successful with this song. It

was very well received, and Judge

Galloway, who was in the audience, must have

been very happy over its

reception." 1

After the concert, the glee clubbers

moved a couple of blocks east on Broad Street

to the Columbus Club (still today a

fashionable uppercrust club), where "a delight-

ful smoker" was sponsored by the

Yale alumni for the twenty-three choristers. Gal-