Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

ROBERTA MENDEL

Carl Frederick Wittke:

Versatile Humanist

There're too many do-gooders

and organizers and not enough

quiet humanitarians among us.

Cleveland Sun Press,

November 18, 1971

Native Ohioan Carl Frederick Wittke

distinguished himself in many areas of aca-

deme. At such Ohio institutions of

higher learning as Ohio State University, Ober-

lin, and Western Reserve University, he

is recognized as an outstanding teacher, ad-

ministrator, and mediator. Nationally,

he is remembered as an indefatigable,

forceful, and courageous civil

libertarian and fighter for academic freedom. Inter-

nationally, he is acknowledged as one of

the historians largely responsible for the

development of the cultural aspects of

American immigrant historiography. Before

it was fashionable, he recognized

cultural pluralism-not the melting pot-as the

hallmark of American society. As an

historian and critic Dr. Wittke expressed his

thematic ideas with succinctness, more

than a dash of imagery, and a great deal of

tolerance. His impact was thereby felt

outside as well as inside his own field of

interest.

Dr. Wittke's many accomplishments

reflect a strict but compassionate home life.

Carl Wittke, the senior, was a German

immigrant who, upon landing in the port of

New York, bought a ticket as far west as

his money would stretch. This happened to

be Columbus, Ohio. It was here, on

November 13, 1892, that a son, Carl Frederick,

was born. While Carl senior was not a

formally educated man and had no degree in

engineering, he was a "mechanical

genius." Through a combination of aptitude and

diligence, he started a factory and

prospered enough to provide educational op-

portunities and adequate comforts for

his family.1 As all immigrants, Wittke

struggled to combine the ways of his

adopted country with familiar customs of the

Old Country without losing the flavor

and substance of the latter. His son's work,

which covered a span of forty-nine

years, 1921-1970, is a testament to the fact that

the father successfully instilled a deep

and abiding respect and love of his German

1. Interview with Thya Johnson,

September 13, 1971. Miss Johnson was Dr. Wittke's secretary for

twenty-four years. See also C. H.

Cramer, "Speech Honoring Dr. Wittke," March 31, 1971, p. 3, in Case-

Western Reserve University Library.

Ms. Mendel is a lecturer, teacher, and

author from the Cleveland area. She is presently on the staff of

Cuyahoga Community College-Eastern

Campus.

|

heritage in young Carl. This respect and love provided the basis for his under- standing sympathy of all the other ethnic minorities that contributed to the flow of American immigration from colonial times to the mid-1960's. Dr. Carl Wittke's greatest work, We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant, as well as twelve other major works, a comprehensive six volume history of Ohio for which he was editor, hundreds of articles, and 262 critical book reviews, resulted from his dedica- tion to the ideals and values of his childhood. In the "Dedicatory Preface" of We Who Built America, Dr. Wittke credits the experiences of his father-Mr. Common Immigrant-as the stuff of which "the real Epic of America must eventually be writ- ten." 2 German was young Carl's first language. The consistent use of English did not come until his entrance to school. Eventually, these two languages were augmented by French, Latin, and Greek-good tools for the future historian. In 1913 he gradu- ated Phi Beta Kappa from Ohio State University, joined the faculty a few years later, and began work on his doctorate under Harvard Professor Charles H. McIlwain, "a brilliant and humane scholar of English legal institutions." Wittke re- ceived his doctorate in 1921, and in 1925 became history department chairman (and later, dean of the graduate school) at Ohio State University where he remained until 1937, when he took a position at Oberlin College. From 1939 to 1947 he was dean at Oberlin, and, since that position was not a specialized one at the time, he was rather

2. Carl F. Wittke, We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant (Cleveland, 1964), v. |

|

a jack-of-all-trades. Because he got along so well with people, he was often the mediator of the various elements involved in campus labor disputes. Like former United States Secretary of State Dean Acheson, Dr. Wittke subscribed to the theory that "the best diplomacy is on the personal level."3 In the spring of 1948, having been lured away from Oberlin by Western Reserve University, Dr. Wittke became dean of the graduate school, a position he retained until his retirement in June 1963. He also served as vice president of the University, chairman of the history department, and-for a short period-chairman of the politi- cal science department. Throughout his professional life, unsought honors and degrees were heaped upon him. He received five honorary degrees, honorary membership in the Deutsch Aka- demie, fellowship in the Royal Historical Society, the Elbert Jay Benton Distin- guished Professor of History Award, the Sol Fetterman Memorial Award of Cleve- land B'nai B'rith (1951), and the Brotherhood Award of the National Conference of Christians and Jews (1956); twice he won the annual Book Award of the Ohio Acad- emy of History. He was selected by the Federal Government to be on the advisory committee to the Museum of Immigration, located in the base of the Statue of Lib-

3. C. H. Cramer, "Carl Frederick Wittke, 13 November 1892-24 May 1971: In Memoriam"; Cramer, "Carl Frederick Wittke," Ohio Academy of History Newsletter, II (November 1971), 1; Harvey Wish, "Carl Wittke, Historian," in Fritiof O. Ander, ed., Festschrift, In the Trek of Immigrants (Rock Island, Ill., 1964), 3; Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 13, 1971. Thya Johnson stated that Dr. Wittke remained at Oberlin until spring 1948, so there is a slight discrepancy of dates. |

Carl Wittke

81

erty, and by the State Department to put

together a library which was ultimately

sent to various underdeveloped

countries. He was the choice of the Cleveland Civil

Liberties Union for its Man of the Year

Award (1961). Upon his retirement, his

friend, historian Fritiof Ander,

compiled a Festschrift, In the Trek of Immigrants, in

his honor, and Dr. Lyon N. Richardson,

librarian of Western Reserve's Freiberger

Library, collected all Dr. Wittke's

works as well as everything written about him, in

a special section of the library put

aside for that purpose. Dr. Wittke's personal pa-

pers will eventually find their place

here also.4

After his retirement, Dr. Wittke

continued to live by the two rigorous rules that he

had set for himself: "to meet every

task today, not on the morrow" and "to have a

project always in progress-to have

something constantly simmering in the research

kettle."5 He held to this dictum

even in the last three years of his life which were

plagued by illness. In fact, he

continued to write book reviews and articles until the

end of 1970. He died in May 1971,

leaving a widow, a son who is a teacher at

Shaker Heights High School, and two

grandchildren. During his long life, he made

a lasting imprint on his times as a

scholar, teacher, administrator, and human being.

Dr. Wittke was a many-faceted

individual. Besides his historical pursuits, he had

an abiding interest in baseball, a sport

which he not only wrote about, but one in

which he actively participated. He could

also hold his own in any discussion on the

fine points of such varied subjects as

dentistry or architecture. He loved music and

was capable of playing at least six

musical instruments well. In his early years, he

played clarinet and sang in a variety of

minstrel shows throughout the Midwest.

While at Oberlin he often played violin

in the local symphony orchestra. Later at

Western Reserve University, while

retaining his love of classical music, he mastered

the guitar and accompanied himself and

friends in singing German folk songs,

which he loved.6 In short he

could be termed a versatile humanist.

The comments of those who knew him,

whether they be student, colleague, or

friend were all the same: unassuming . .

. fair . . . warm . . . objective . . . under-

standing ... humble . . . rational and

humanistic... humorous ... enthusiastic ...

inquisitive . . . energetic . . .

courageous.7 But, perhaps the best way to sum up Carl

Wittke, the man, is through his own

words when he commented on the life of educator

William Oxley Thompson, a man with whom

he empathized and obviously ad-

mired:

[He] remained something of an enigma,

for despite his instinctive friendliness and gener-

osity, he was never demonstrative and

few knew him well . . . a courteous, yet forceful,

gentleman, outspoken, sometimes

amazingly frank and uninhibited with a real sense of hu-

mor... not afraid to make decisions, though

he knew they would be sharply criticized ...

also understood that there is a place

for administrative inertia, when time is needed to let

crises settle themselves .. . loved to

preach and make speeches ... not a flowery orator ...

nor a coiner of many unforgettable

phrases ... extraordinary success on the platform ... due

4. Dean Cramer and Fritiof Ander differ

as to the number of honorary degrees held by Dr. Wittke.

Cramer, in his "Speech" of

March 31, 1971, p. 10, claims there were six, while Ander, in his essay,

"Four

Historians of Immigration" (Trek,

41), claims there were only five. Dr. Wittke also served on the editorial

boards of the Mississippi Valley

Historical Review, Canadian Historical Review, and the Ohio Historical

Society Quarterly. He held the

presidency of the American Historical Association for the 1940-41 term.

5. Cramer, "Speech," 7.

6. In his essay, "Carl Wittke,

Historian," Dr. Wish states that these experiences inspired Dr. Wittke to

write Tambo and Bones: A History of

the American Minstrel Stage (Durham, 1930); Cramer, "Speech," 2.

7. This is a composite of the comments

taken from interviews with colleagues, co-workers, and former

students of Dr. Wittke.

82 OHIO

HISTORY

rather to his directness and integrity,

and the sheer physical power which made his words

tumble out like a torrential mountain

stream ... massive person, who combined dignity with

democracy ... read widely ... played

baseball occasionally on campus, and shocked a num-

ber of the faculty by sliding into a

base . . . was patient and understanding; a man who

sought justice tempered with compassion,

and people knew he could be trusted.8

Like educators William Oxley Thompson

and James Lewis Morrill, Dr. Wittke

was a firm proponent of state supported

higher education which combined the vo-

cational with the cultural. He did not

see the Federal Government as a threat to

university autonomy. Indeed, it appears

that as far back as 1961, he foresaw some of

the financial problems that are

besetting higher educational institutions in the

1970's. In his review of James Lewis

Morrill's book, The Ongoing State University,

he agreed with the author's conclusion

that unless more research grants were forth-

coming from the Federal Government, the

schools would have to make up the slack,

a proposition that most could ill afford

if they were to uphold quality education.9

The facts show that by 1961 the quality

of education was already being diluted by

the overexpansion of old schools and a

plethora of "not very good new ones." He

agreed with educator G. S. Ford that

good teaching, not size, determines excellence;

and that the most important job of the

administrator was "to choose good men, and

to build a good library." Dr.

Wittke also felt that a good administrator who "had the

ability and will to work, need not

forego the pleasures of productive scholarship. In-

deed, in enriching himself, [he would]

become a better administrator." Instead of

expending so much energy castigating

real or imagined inroads by the Federal Gov-

ernment, Wittke felt that administrators

should try to remedy the "underliberalized-

overprofessionalized" land grant

college. In this way, graduates would become more

receptive, adaptive individuals than the

colleges were turning out.10

The old nineteenth century argument of

liberal versus practical education was

again rearing its head. But, being a man

of reason and moderation, Dr. Wittke re-

fused to be caught in the position of

either/or. While he sympathized with many of

the goals of progressive education, his

distrust of "superindividualism" and espe-

cially his awareness of the many

problems inherent in implementing an inter-

disciplinary approach kept him from

accepting a progressive educational structure

carte blanche. 11

Dr. Wittke's special talents and

personal characteristics made him an effective ad-

ministrator and teacher. In the words of

Thya Johnson, his former secretary, "He

could talk to anybody, high or low, make

anyone feel at ease" for he liked people in

general-but he especially liked his

students. He was always available to them to

provide that decisive word of

encouragement, to help sort out confused thoughts;

however, he did not mollycoddle either

his students or his colleagues and was ex-

tremely frank-but this was a frankness

tempered with compassion and under-

standing. Indeed, he welcomed rational,

well-thought-out disagreement, although

he admitted that at times he let his

"heart overrule his head." 12

As an administrator, he, with President

Thompson, prized "educational states-

manship . . . practical wisdom"; he

was tolerant of such things as "occasional [fac-

8. A list of selected book reviews by

Dr. Wittke (WBR) accompanies this article. WBR, N: 1. (The capi-

tal letter designates the journal in

which the review is published, and the Arabic number the specific book

reviewed.)

9. Ibid.; F:3, 7; K:34.

10. WBR,N:l; F:3.

11. Thya Johnson interview; WBR, F:3;

K:34; N: l.

12. Thya Johnson interview; C. H. Cramer,

"Bibliography of Wittke's Works," Trek, 41.

Carl Wittke 83

ulty] aberrations." Perhaps one of

the reasons that he consistently kept a finger in

the teaching pie-even though his

schedule as an administrator, teacher, researcher,

"rapid" writer, book reviewer,

prolific reader and inveterate correspondent would

have sapped the energy of several

men-was that he wished to retain a sense of

"scholar's balance." This,

when carried over into his non-academic duties, allowed

him to be a successful mediator in

matters both petty and important between fac-

ulty and administration. He wanted each

to feel that there had been a fair hearing

and that a just decision had been made.

On both the administrative and academic

levels, he refused to become bogged down

in inhuman, often self-defeating, ele-

ments as personalities, minutiae,

statistics, and irrelevant data, always insisting

upon adhering to standards of excellence

in all his endeavors.13

As the area of civil rights was closely

allied with his chief historical interest, the

American immigrant, it is not surprising

that Dr. Wittke was an active participant

in, and a vigilant watchdog of, academic

freedom. As chairman of Committee "A"

(Academic Freedom and Tenure) of the

American Association of University Profes-

sors (AAUP) for three years, he expended

"massive energy and courage in fighting

national battles [on behalf] of academic

freedom" at a time when "professional ten-

ure was but an aspiration." In

1942, he vehemently disagreed with the results of a

sociological study of the academic

profession which stated that the most important

objective of the AAUP was to increase

the bargaining power of its members. In-

stead, Dr. Wittke replied, the

"delicate question of teacher's rights . . . more ade-

quate and rational bases for appraising

academic people, . . . [and] academic free-

dom" were the major concerns of the

AAUP.14

In a 1961 book review, he touched on one

avenue of academic freedom. In true

Jeffersonian tradition, he took issue

with Merle Curti and agreed with the AAUP

that "membership in the Communist

Party should [not] ipso facto disqualify a fac-

ulty member...." He held true to

his courageous opinions expressed five years pre-

viously that a university is only free

when it does not coerce man in reference to his

beliefs nor suppress his freedom to

express them; "error of opinion can be tolerated

so long as reason is left free to combat

it." 15

According to Thya Johnson, the McCarthy

era of the fifties was terribly dis-

tressing to Dr. Wittke; however, his

concern did not inhibit him in the classroom, on

the podium, or in print. In fact, he

went out of his way to speak up for those he felt

were unjustly accused in the academic

community, just as Dean Acheson President

Truman's Secretary of State did in the

governmental sphere. Mr. Acheson had char-

acterized Senator McCarthy as a

"very cheap, low scoundrel; to denigrate him is to

praise him." It is probable that

Wittke's stand helped to bolster the moral support

which Western Reserve University

extended to the members of its community. And

he certainly felt as one with Merle

Curti in his "concern over our recent retreat from

reason, in this so-called age of

science, into an era of uncritical faith and public dis-

plays of piety," a type of

filiopietism.16 This is demonstrated by one of the few times

that Dr. Wittke shed his mantle of

objectivity in reviewing another's work. In 1958

13. WBR, N:l; Wish, "Carl Wittke,

Historian," Trek, 5; Thya Johnson interview; Cramer,

"Speech,"

5. See also WBR, F:8 for a detailed discussion of what Dr.

Wittke meant by the term "scholar's balance."

14. Wish, "Carl Wittke,

Historian," Trek, 3; Cramer, "Speech," 5; WBR, F:8.

15. WBR, F:7; N: 1; Cramer,

"Speech," 8; Cramer, "Carl Frederick Wittke."

16. Thya Johnson interview; WBR, K:7;

Cramer, "Carl Frederick Wittke." Dr. Wittke had expe-

rienced firsthand McCarthyite-type

tactics during World War I and in the early 1920's. As a result he had

an abiding intolerance for those who

exploited their fellow citizens, a determination to fight them, and a

dislike of hyphenated terminology in

reference to various immigrant groups.

84 OHIO

HISTORY

he praised author-educator John Caughey

for his refusal to take the Loyalty Oath at

the University of California. Toward the

end of the review, he let loose a diatribe

against McCarthyite tactics which he

remembered well from his youth during the

"anti-Hun hysteria" of World

War I. He ended his review by stating that Caughey's

book "should help us understand

that the greatest damage which the Communists

have done our people has been in

frightening many good Americans into surrender-

ing their basic liberties and betraying

the historic mission of the country they

love." 17

Dr. Wittke was such a prolific reader

that, to quote his secretary, he "read books

faster than I could bring them to him

from the library." And, not only books: the

daily New York Times got a

thorough perusal, as well as numerous articles and es-

says on a variety of subjects. So it is

not surprising that he produced as many book

reviews as he did. What is surprising

is that he was able to limit himself to the sub-

jects of review, for he was sought after

by the many editors with whom he had built

up a voluminous correspondence and, in

some cases, a personal friendship through

membership in various historical

organizations.

As a reviewer, Dr. Wittke demanded as

much excellence of the writer as he did of

himself in his own writings. Just as, in

his opinion, no point of history was too small

for historical research, so too none was

too insignificant for the reviewer to concern

himself. He gave no quarter, but was as

"scrupulously fair" in this endeavor as he

was in all other areas of his life. In

fact, at times he bent over backwards to say

something nice about even the most mediocre work. The only

exceptions occurred

when he reviewed works by foreign-born

authors who showed little appreciation or

understanding for their immigrant

heritage-and had the gall to produce a work

which clearly exhibited their

ignorance. He was especially critical when he was deal-

ing with themes or theses which

paralleled his own. He abhorred the "scholarly

vendettas" practiced by not a few

European historians. Gratified that he found little

of this among his own countrymen, he

thought that historical scholarship and learn-

ing in the United States compared

favorably with that in all other countries.18

It was not necessary for a book to be

scholarly to earn Dr. Wittke's approval, al-

though the highest accolades were

reserved for this type of work. He was only

slightly less impressed by a paper which

contained off-beat subject matter, popu-

larly treated, as long as it indicated

comprehensive research, fairness and objectivity

on the part of the author, and was

written "in a simple, pragmatic" manner. In his

estimation, F. E. Hill's What Is

American? written in an "informal journalistic style

and in a liberal, tolerant spirit"

is one of those books which fell into this category. In

fact, Dr. Wittke often made allowances

for non-professional historical writers, espe-

cially in the matter of form and style,

when they delved into unfamiliar subject mat-

ter. But he made none for

professional historians, or those who aspired to that pro-

fession-unless the author happened to be one of the lucky ones who had

unearthed

a heretofore unknown primary source.19

For such a one a great deal could be for-

given, but this happened only rarely.

Although Dr. Wittke found it easy to

forgive an author lapses in technique, inad-

17. WBR, K:5; Wish, "Carl Wittke,

Historian," 4, especially credits the "anti-Hun" hysteria

prevalent

during World War I with Dr. Wittke's

almost phobic preoccupation with the historical role of the Ger-

man-American and civil rights; Cramer,

"Speech," 8.

18. Thya Johnson interview; WBR, A:5,

15, 18, 23, 25; C: 1; D:4; F: 1; G:3; J: 1; K:3, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18,

19, 20, 26, 38. As Cramer states in

"Carl Frederick Wittke," Dr. Wittke was "never known to raise

his

voice or dip his pen in vitriol!"

19. WBR, H:1; K:17, 23, 26, 30, 37.

Carl Wittke 85

vertent factual carelessness,

editorializing and other minor irritations, there were a

number of things that he felt were

inexcusable in a published work. Any "sin

against precision" was at the top

of this list: "careless proofreading," "slipshod

bibliographies," gushiness and an

"exuberance of adjectives and adverbs," poor or-

ganization, "undistinguished,

uncritical style," use of unimportant anecdotes, long

quotations, and a lack of synthesis. Any

hint of apologism, bias, or simplistic gener-

alizations drew the most scathing, often

sarcastic comments, for Dr. Wittke felt these

faults led to "defective

conclusions." He found the ignorant writer and the racial

theorist pathetic; one can only

speculate as to his reasons for choosing such a work

to review. Perhaps it was to point out

how the author had misused factual data in

order to support an unsupportable

theory, thus producing-as had Madison Grant

with his The Conquest of a Continent:

Or the Expansion of Races in America-a

blatantly ridiculous and a thoroughly

bad work. Or perhaps he chose to review it as

a means to emphasize the fact that since

this type of work is all too prevalent, the

reader must beware.20

There were a number of other aspects of

writing that Dr. Wittke felt denigrated

historical scholarship. He enumerated

some in his review of Eric F. Goldman's John

Bach McMaster. These were heavy reliance on secondary

sources-especially when

with little or no effort the author

could have used primary sources-close para-

phrasing, careless quotations which

sometimes changed the meaning of the original

context, inaccurate footnoting, or

footnoting the obvious and ignoring that which

needed clarity, "intemperate

language," and yielding too easily to pressure groups

so as to insure larger markets for a

textbook.

Several faults dealing more with content

than scholarship irritated Wittke with

such Canadian authors as Thomas Wood

Stevens, Emil L. Jordan, and Gerald S.

Graham. He faulted Stevens and Jordan

for attempting to cover too large a topic in

too short a book, while he severely

reprimanded Graham for producing a lopsided

history of Canada by devoting the major

portion of Canada: A Short History to that

country's colonial beginnnings before

1763, leaving only seventy-five pages for the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Canadian authors-and some American au-

thors-were also scored for such things

as presuming that the average reader was

more knowledgeable than he actually was,

and for antiquarianism. He felt that

"reminiscences of men who wrote

when they were ninety years old . . . about events

that occurred a half a century

before" were boring, repetitious, and of little value.

He not a little sarcastically ended his

review of J. W. Pickersgill's The Mackenzie

King Record with the statement, "there are many pages in the

diary, all handwritten,

and unfortunately not represented here,

dealing with the illness, death, and burial

of the P. M.'s pet Irish terrier,

Pat." Genealogy, as such, did not interest him.21

All told, Dr. Wittke expected the same

of authors and their books as he did of ad-

ministrators and teachers: he demanded

that they be courageous, ingenious, and

thorough. Authors, he thought, should have

an affection for and be well steeped in

their subject matter so that they would

be able to bring objectivity, humor, tact, un-

derstanding, and a wealth of

pertinent detail, enhanced by dramatic imagery, as well

as "intellectual balance" and

a "masterly synthesis" to their work. Finally, the prod-

uct should be punctuated by

comprehensive, pertinent footnotes.22

20. Quotations taken from selected

reviews listed at the end of this article.

21. WBR, A:12; F:4; G:6; K:24, 41.

22. Cramer, "Bibliography of

Wittke's Works," Trek, 41; quotations taken from selected reviews

listed

at the end of this article.

86 OHIO

HISTORY

Although philosophically he may have

been as one with such scholars as Oscar

Handlin, a representative of the New

School of immigrant reappraisal, Wittke could

not as an historian accept Handlin's

cavalier attitude toward footnoting and bib-

liographic detail. While Dr. Wittke's

own method was rather unorthodox in that he

never used a formal bibliography when he

could avoid it, much preferring to place

his combined footnotes, remarks, and

bibliographical references at the end of each

chapter, it can never be said that his

references were any less complete or scholarly

than an historian who followed the set

pattern.23

Dr. Carl F. Wittke, along with Theodore

C. Blegen, Marcus Lee Hansen, and

George M. Stephenson are often referred

to as the pioneer, or grass root historians

of United States immigration. Each

"touched upon certain aspects of civilization's

transit." Basically these four

Midwest historians held similar views in broad areas of

civil rights and immigration, although

the development of their approaches and in-

terests were largely divergent. Thus,

even if these scholars had been the sort to

indulge in self-defeating intellectual

and professional jealousy, they did not; the

frontiers in the field were unlimited.

Instead, a supportive and lively four-way in-

tellectual correspondence gradually

developed based on mutual respect and interest

in each other's work; in the case of

Drs. Wittke and Blegen, a warm enduring

friendship was forged.24

Edward N. Saveth, editor of Understanding

the American Past, stated that in the

period 1875 to 1925 "history had

hardly more than occasional insight into the role

of immigration in our national

redevelopment. When [historians] treated the subject

of European immigration at all, they

treated it as a sort of historiographic hang-

nail-a side issue to which little

attention need be paid." The immigrant was

"viewed as a 'problem,' which could

only be resolved by assimilation, American-

ization." In 1926, Dr. George N.

Stephenson became the first to realize that the his-

tory of America could not be complete

without an understanding of the causes and

motives behind the "exodus from

Europe to America" and that this understanding

would not be found in documents or

literature which celebrated the exploits of a

few. It would only be found in the local

social and political history of the common

immigrant, but his history was

"scattered ... scanty, colored by prejudice, and . . .

difficult for later generations to

interpret and animate." However, by 1939, when

Dr. Wittke's We Who Built America was

published, significant inroads had been

made not only in discovering and

cataloging the voluminous primary source mate-

rial relating to the Old immigrant in

America and Europe, but also in developing

fresh approaches for deriving new

theories.25

Dr. Fritiof Ander, a close friend of Dr.

Wittke, has stated that the immigrant his-

torians "climbed mountain peaks for

new vistas from which to view history." Dr.

Stephenson was "among the first to

see and exploit the objective and non-

filiopietistic study of

immigration," although he limited himself largely to the reli-

23. Ander, "Notes," Trek, 268,

note 39.

24. Ander, "Four Historians of

Immigration," Trek, 18, 22; Carlton C. Qualey, "Eulogy of

Wittke,"

American Historical Review (February 1972), 249-250; Merle Curti, "The Impact

of the Revolution of

1848 on American Thought," in

Edward N. Saveth, ed., Undrstanding the American Past (Boston, 1965),

234-235; Marcus Lee Hansen, The

Immigrant in American History (Cambridge, 1940); Thya Johnson in-

terview.

25. Edward N. Saveth, American

Historians and European Immigrants: 1875-1925 (New York, 1965), 9;

Ander, "Four Historians of

Immigration," Trek, 20; George M. Stephenson, A History of

American Im-

migration: 1820-1924 (New York, 1926), 8 as quoted in Ander, Trek, 17;

WBR, A:2. See Hansen, The

Immigrant in American History for a commentary on the status of immigrant history in

1940.

Carl Wittke

87

gious and political aspects of the Old

immigration. Dr. Hansen was drawn toward

economic causality and the "broad

significance of migrations" rather than toward

the narrower sphere of individual

nationalities. Dr. Blegen, influenced by his heri-

tage and the fact that he was a

Minnesotan, was intrigued with the Scandinavian

migrations. Dr. Wittke was less

concerned with causality than with the impact of im-

migrant contributions on American life.

Therefore, he "stressed the cultural aspects

of immigration," especially those

of the German and the Irish.26

The late twenties was the gestation

period during which these scholars established

their goals and explored many

sources-immigrant letters, newspapers, literature,

diaries, memoirs, recollections, church

histories-both here and abroad. The thirties

and forties, a period when emphasis on

minority problems was growing, were the

years of fruition for this first wave of

immigrant historians. The early works re-

flected the authors' close

identification with particular regions and social groups, as

well as the "progressive and

pragmatic ideas" which were then prominent in the

field of historical scholarship. As all

firsts, John Higham states in his essay, "The

Historian As Moral Critic," these

pioneers were somewhat "self-conscious represen-

tatives of various ethnic minorities . .

. turning up facets of our history reflective of

[ethnic] claims or grievances and

championing regionalism." As such, they "played

a significant role in reviving an

interest in state and local history which they helped

to make respectable." 27

In addition to being one of the

pioneering historians, Dr. Wittke belonged to what

Hansen spoke of as the "third

generation historians," those "culture" historians who

stressed immigrant contributions to

the overall culture pattern as opposed to those

"second generation"

historians, such as Oscar Handlin, who stressed immigrant ad-

justment to and assimilation of an illusory "American" culture. Hansen also

believed

that it was the duty of the "third

generation" historian to exploit the immigrant

theme in American history, for he alone

could recapture the atmosphere of his eth-

nic background. He was not hampered by

embarrassment of his forebears' peculiar-

ities; on the contrary, with distance

(in time) he had developed a certain pride in

their achievements, a feeling of ethnic

uniqueness which, along with his linguistic

fluency, would allow him not only to

unlock and preserve those letters and other

memorabilia which lay buried in the

immigrant tongue, but also to grasp the men-

tality of people who had to straddle two

cultures in adjusting to American condi-

tions. Dr. Wittke took on this

obligation with a vengeance and produced works

which are considered classics in

American historiography.28

To Dr. Wittke there was, as yet, no such

thing as an "American" culture. Perhaps

there never would be, for although each

group within the successive waves of immi-

26. Ander, "Four Historians of

Immigration" and Wish, "Carl Wittke, Historian," Trek, 17-32;

Ber-

nard Titowsky, ed., American History:

A Guide to Student Reading for Teachers and Librarians, McKinley

Bibliographies (Brooklawn, N.J., 1964),

IV, 24; WBR, K:21; Marcus Lee Hansen, "The Third Gener-

ation," in Saveth, Understanding

the American Past, 467.

27. Ibid., 466-467; Ander,

"Four Historians of Immigration" and Wish, "Carl Wittke,

Historian,"

Trek, 3-32; John Higham, "The Historian as Moral

Critic," in Edward N. Saveth, ed., American History

and the Social Sciences (London, 1964), 496; Robert Allen Skotheim, ed., The

Historian and the Climate

of Opinion (London, 1969), 197-198.

28. H. Hale Bellot, American History

and American Historians: A Review of Recent Contributions to the

Interpretations of History of the

U.S. (Great Britain, 1952), 157;

Hansen, "The Third Generation," 467;

Hansen, The Immigrant in American

History; see Oscar Handlin, The Americans: A New History of the

People of the United States (Boston, 1963) and Oscar Handlin and Mary F. Handlin, Facing

Life: Youth

and the Family in American History (Boston, 1971) for recent examples of the Handlin

approach to immi-

grant history.

88 OHIO HISTORY

grants, consciously and unconsciously,

blended certain aspects of its cultural heri-

tage with those of other groups-and this

mixture simultaneously acted upon and

determined the "American way of

life"-a core of latent ethnicity remained within

each individual. Dr. Wittke referred to

this ethnicity as a "national self' and defined

it as an ephemeral something of the

body, mind and spirit; it "determined what a

person is, what he is able to do, and

what he is likely to do in a new environment."

Because ethnicity is an integral part of

each person, it is something that one cannot

escape.29

The theme of historical continuity-of

cultural blending, but not of assimilation-

threads its way through many of Dr.

Wittke's writings. He realized that in order to

understand America-that "mother of

exiles ... [that] young nation with Old World

memories"-and her history, one

needed to indulge in a radical analysis of the het-

erogeneous American population. This,

Wittke, Blegen, and Hansen among others

proceeded to do. Blegen and Hansen

delved into the Kulturgeschicht of the Scanda-

navian countries, while Wittke concerned

himself with the adjustments of ethnic

communities on a local-regional basis.

The immigrant was traced from his birth-

place, across the Atlantic, and then

from one frontier settlement to another. It was

recognized that both Europe and America

would need to be the field of research for

anyone who desired a mastery of American

immigrant historiography. Because of

this, Dr. Wittke was a vocal exponent of

the value of traveling fellowships, and was

an ardent linguist.30

Although Wittke did not rely on any

single source in his research, he felt that the

foreign language press was one of the

most important elements available in main-

taining ethnic historical continuity.

Printed materials not only aided the immigrant

in preserving his ties wih the Old

Country but also constituted a major resource in

easing his communication problems and

orienting himself to his new environment.

Mainly because of his own background,

but partly because the German immigrant

belonged to the largest non-English

speaking group in America, Dr. Wittke became

expert in all the nuances of the German

language press. He was especially fasci-

nated with the influence of the

German-American mind, as exemplified by the Ger-

man Forty-eighters, on the American

scene. Infrequently, his enthusiasm got the

better of him and he indulged in the

same hyperbole for which he scored others. For

example, reviewer Alice Felt Tyler felt

he made excessive claims for the German

Forty-eighters, "in the way of

cultural contributions for there was interest [in all im-

migrant cultural contributions] before

they came and it [the interest] would have

grown even without them." However,

perhaps he exaggerated intentionally for ef-

fect because, as reviewer Tyler admits,

Dr. Wittke's larger purpose was to use the

Forty-eighters as a "cultural

leaven" for studying all German Americans.31

Directly connected with his thesis of

historical and cultural continuity was Dr.

Wittke's interest in the underlying

theories of change, for he felt that the reasons for

change were more important than the

change itself. For example, in his review of G.

29. Carl F. Wittke, "Melting Pot

Literature," College English, VII (1945-46), 189; Wittke, "The

Norwe-

gian Element in the Northwest," American

Historical Review, XL (1934), 72-73; Ander, "Notes," Trek,

268-269, notes 38, 50.

30. Wittke, "The Immigrant in

America," in Miers, The American Story, 245, 248; Wittke,

"Melting

Pot Literature," 189; Wittke, We

Who Built America, 533; see also WBR, A:2, 4, 13; K:33, 44.

31. Wish, "Carl Wittke,

Historian," and Ander, "Four Historians of Immigration," Trek,

7, 23, 27, note

52, Chapter 2, 269; Alice Felt Tyler,

review of Carl Wittke, Refugees of Revolution: The German Forty-

Eighters in America (Philadelphia, 1952), in American Historical Review,

LVIII (October 1952), 134;

WBR, A:9.

Carl Wittke

89

Frederick Knaller's The Educational

Philosophy of National Socialism, he said of the

Nazi philosophy that one must understand

it before one can cope with it, for "ideas

are not defeated on a battlefield."

Although he disliked labels, he was inclined to

place history within the sphere of the

humanities rather than the social sciences. He

felt that "you could read all the

facts, but it took a certain art to put them all to-

gether to make theirs a meaningful

story." Like Stephenson-and unlike some social

historians who relied heavily on

statistical evidence and technical jargon-Wittke

did not think that cold facts, brutally

and mathematically expressed, were "history."

Much could be "hung on other

racks," for history was, above all, complexity and

people.32

According to Wittke, these "other

racks" are what should be brought out by the

historian. He thought that the historian

should be content to describe historical phe-

nomena and, from this, make simple

deductions. He should not be-as is often the

case with sociologists and social

psychologists-a "specialist in curiosities" who in-

creases or perpetuates "minority

caricatures," thus stimulating ignorance and prej-

udice rather than understanding and

social reform. Neither should he ignore any

facet of history because it is "too

small to dwell on," for history can only be known

by its parts, both small and large,

important and unimportant, and as it is rewritten

by each generation "in terms of its

own problems and concerns." It can never be

known in toto, nor, for the same

reason, should the historian dedicate himself to

being one kind of historian.33

Dr. Wittke felt that there were many

areas and themes that were either ad-

vertently or inadvertently neglected in

American historiography. His mind was for-

ever open to new ideas; indeed, his

secretary says that in large part his subjects were

chosen by "serendipity." He

would come across a great deal of manuscript material

which suggested an interesting theme or

thesis; soon, sometimes with the help of his

wife, he would simultaneously busy

himself taking voluminous notes on 3 by 5 note

cards and mentally compose the book,

essay, article, or whatever, so that when he

felt that he had done a thorough job of

research, the actual writing came quickly

and easily. The imagery, the tart

phrase, the wit seemed to roll off the tip of his pen:

"prodigious research";

"steerage slime . . . damned lop-eared Dutchmen"; "trestle

board of life"; "patriotic

cobwebs"; "splay-footed Irish bog trotters"; "elusive his-

torical materials"; "hammering

out a new civilization on the anvil of 'American-

ization,'" to name a few. Although

he was approached many times by many promi-

nent authors and editors to collaborate

on books, he always refused. He wanted all

that he produced to be his own work, to

reflect only his own ideas. Once he had de-

cided what he wished to say and how he

wished to say it, he would not be moder-

ated-or sidetracked-but would speak out

regardless of the consequences.

Some of the areas which Dr. Wittke felt

would benefit from a bit of historical re-

32. WBR, F:6; Thya Johnson interview. A

sociological historian differs from a social historian in that

the latter emphasizes the how rather

than the what; see Dixon Ryan Fox's excellent explanation in Ideas

in Motion (New York, 1935); see also Bellot, American

History and American Historians, 157, who called

Dr. Wittke's History of the State of

Ohio a "scientific state history," and Higham, "The

Historian as

Moral Critic," American

Historical Review, LVIII (April 1962), 609-625.

33. Carl F. Wittke, "Immigrant

Theme on the American Stage," Mississippi Valley Historical Review,

XXXIX (September 1952), 231; WBR, A: 11,

18, 25; F:5; G:5; K:2, 13, 16, 44; L:1. Although most of his

work deals with immigrant groups, Cramer

in "Carl Frederick Wittke" points out that Wittke placed the

major emphasis in his work on "men

who struggled against the current for an ideal." Dr. Wittke was of-

ten on the borderline between general

and bibliographic, but in the last analysis he could not be stereo-

typed, for he never confused the part

with the whole.

|

furbishment were historian-layman, American-Canadian, and local-national-inter- national governmental relations. He advocated an expansion and testing of the Turner thesis in human terms, a further consideration of reverse migration, nativ- ism, and the "transit of representative institutions across the Atlantic." Neglected topics needing in-depth coverage included study of the immigrant Welsh and Finns, and the Irish in the 1830's. Wittke also saw peripheral areas that should have atten- tion, such as ethnic religious institutions, the immigrant in and of literature, com- parisons and contrasts of the "old" immigrant to the "new" immigrant, and Amer- ica's raison d'etre. Dr. Wittke-historian, essayist, reviewer, administrator, mediator, and orator- was above all a practical idealist, a teacher. Dean Cramer stated that Dr. Wittke "often said that his pride in the accomplishments of former students exceeded the very real satisfactions he gained from numerous publications." He must have been inordinately proud of such former students as Ted Saloutis who, under Dr. Wittke's tutelage at Oberlin College, eventually produced a history of the Greek immigrant, and Dean C. H. Cramer, who, long before he himself embarked on an illustrious ac- ademic career or had occasion to honor Dr. Wittke publicly, had chosen Dr. Wittke as his spiritual mentor. The establishment of an award-The Carl F. Wittke Award for Distinguished Teaching-coming toward the end of a long and rewarding career, was probably one of Wittke's most cherished honors, for he had often expressed the |

Carl Wittke

91

opinion that excellence in research was

always recognized, but excellence in teach-

ing was taken for granted.

Teaching, civil rights, academic

freedom, and the American immigrant were

Wittke's most important academic and

historical concerns. Like the men he wrote

about, he was courageous, but quietly

so. There was nothing flamboyant or pushy

about Carl Wittke, for the lessons of

history had taught him well the virtue of true

humility. Miss Johnson, his secretary,

has stated that Dean Cramer's "great speech

sums up Dean Wittke in a nutshell,"

but it seems that Dr. Wittke's words honoring

his father might reflect his own

contributions as well:

Unpretentiously, simply, and

harmoniously, his life blended into the American Stream, and

became an humble but honorable fragment

of the record of forgotten thousands who have

helped to build this nation. His plain

virtues of perseverance, thrift, patience, and rugged

honesty, and his remarkable gifts as a

thoroughly trained mechanic [academician], brought

him a measure of success which enabled

him to provide for those he loved the advantages of

which his youth had been deprived. His

deep-seated devotion to the basic ideals of our

American life was born of a long and

satisfying experience in the land of his choice.34

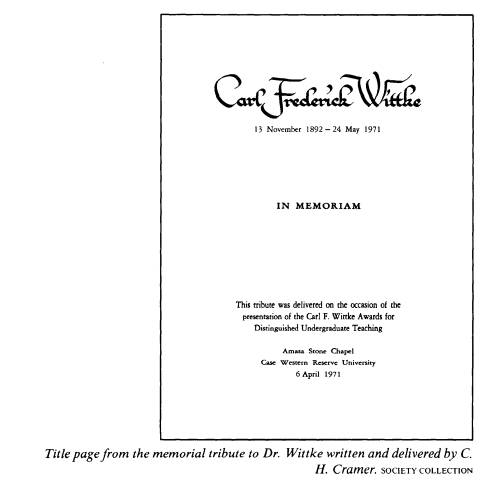

34. Wittke, "Dedicatory

Preface," We Who Built America, v. Miss Johnson and Dean Cramer

also

would certainly agree with Carlton

Qualey's comment that "Carl Wittke will have personal immortality.

For the historical profession his life's

work should be an inspiration, and it is a permanent treasure." In

keeping with this character, Dr. Wittke

desired neither a funeral nor a memorial service; however, his

widow was so impressed with Dean

Cramer's speech on the occasion of the announcement of the Wittke

Award for Distinguished Teaching (March

1971) that she felt Dr. Wittke would not have objected to this

kind of a memorial. She, therefore,

decided to have the speech duplicated and a copy sent to all of his

friends and colleagues.

92

OHIO HISTORY

SELECTED BOOK REVIEWS BY WITTKE (WBR)

A. American Historical Review:

1. Allbeck, Willard D., A Century of

Lutherans in Ohio, LXXI (July 1966), 1454.

2. Blegen, T. C., Grass Roots

History, LIII (April 1948), 567.

3. --, Immigration and American

History: Essays in Honor of Theodore C. Blegen,

LXVII (January 1962), 444.

4. Brebner, John Bartlet, North

Atlantic Triangle: The Interplay of Canada, The United

States, and Great Britain, LI (January 1946), 286.

5. Broden, Robert, Canada in the

Commonwealth: From Conflict to Cooperation, XXXIV

(July 1929), 896.

6. Brown, George W., ed., Canada, LVI

(October 1950), 158.

7. Conway, Alan, The Welsh in

America: Letters from the Immigrants, LXVI (July 1961),

1128.

8. Dewey, A. Gordon, The Dominions

and Diplomacy: The Canadian Contribution,

XXXV (April 1930), 619.

9. Dobert, Eitel W., Deutsche

Demokraten in Amerika: Die Achtundvierziger und Ihre

Schriften, LXIV (April 1959), 726.

10. Ellis, John Tracy, American

Catholicism, LXII (January 1957), 401.

11. Fetjo, Francois, ed., The Opening

of an Era: 1848-An Historical Symposium, LV (July

1950), 898.

12. Graham, Gerald S., Canada: A

Short History, LVI (July 1951), 958.

13. Hansen, Marcus Lee, The Immigrant

in American History, XLVII (October 1941), 161.

14. Higham, John, Strangers in the

Land: Patterns of American Nativism, LXI (April 1956),

657.

15. Kenney, James F., ed., The

Founding of Churchill, Being the Journal of Captain James

Knight, Governor-in-Chief in Hudson

Bay, from the 14th of July to the 15th of September

1717, XXXVIII (April 1933), 610.

16. Kloss, Heinz, Um die Einigung des

Deutschamerikanertums: Die Geschichte einer unvol-

lendenten Volksgruppe, XLIII (April 1938), 644.

17. Lehmann, Heinz, Das Deutschtum in

Westkanada, XLV (April 1940), 667.

18. Luckwaldt, Friedrich, Der

Anfstieg der Vereinigten Staaten zur Weltmacht, XLI (Octo-

ber 1935), 159.

19. --, Geschichte der Vereinigten

Staaten von Amerika, XXVII (October 1921), 2.

20. McDonald, M. Justille, History of

the Irish in Wisconsin in the Nineteenth Century, LX

(July 1955), 1002.

21. Rose, J. Holland, ed., The

Cambridge History of the British Empire, Vol. 6; Canada and

Newfoundland, XXXVI (January 1931), 374.

22. Schott, Carl, Landnahme und

Kolonisation in Canada am Beispiel Sudontarios, XLIII

(January 1938), 399.

23. Stulz, Josef, Die Vereinigten

Staaten von Amerika, XLI (October 1935), 159.

24. Watjen, Hermann, A us der

Fruhzeit des Nordatlantikverkehrs: Studien zur Geschichte

der deutschen Schiffahrt und

deutschen A uswanderung nach den Vereinigten Staaten bis

zum Ende des Amerikanischen

Burgerkniegs, XL (January 1935), 351.

25. Whitridge, Arnold, Men in Crisis:

The Revolutions of 1848, LV (January 1950), 360.

B. American Political Science Review

1. Hartshorne, Edward Y., German

Universities and National Socialism, XXXII (February

1938), 150.

C. The Canadian Historical Review:

1. Wrong, George M., The Canadians, XIX

(September 1938), 316.

D. The Catholic Historical Review:

1. Berthoff, R. T., British

Immigrants in IndustrialAmerica, XL (April 1954), 84.

Carl Wittke

93

2. Fishman, Joshua A., Language

Loyalty in the United States: The Maintenance and Per-

petuation of Non-English Mother

Tongues by American Ethnic and Religious Groups,

LV (January 1970), 644.

3. Lucas, Henry S., Dutch Immigrant

Memoirs and Related Writings, XLII (July 1956),

250.

4. Robertson, Priscilla, Revolutions

of 1848: A Social History, XXXVII (October 1952),

357.

E. The Journal of American History:

1. Bennett, Marion T., American

Immigration Policies: A History, LI (June 1964), 100.

F. The Journal of Higher Education:

1. Barzun, Jacques and Henry F. Graff, The

Modern Researcher, XXIX (January 1958),

52.

2. Davis, R. B., ed., Correspondence

of Thomas Jefferson and Franics Walker Gilmer,

1814-1826, XVIII (January 1947), 50.

3. Ford, G. S., On and Off the

Campus, X (February 1939), 113.

4. Goldman, Eric F., John Bach

McMaster, XIV (June 1943), 337.

5. Hendricks, Luther V., James Harvey

Robinson: Teacher of History, XVIII (October

1947), 388.

6. Knaller, G. Frederick, The

Educational Philosophy of National Socialism, XIII (April

1942), 226.

7. Morrill, James Lewis, The Ongoing

State University, XXII (January 1961), 55.

8. Wilson, Logan, The Academic Man: A

Study in the Sociology of a Profession, XIII

(November 1942), 453.

G. The Journal of Modern History:

1. Cleverdon, Catherine Lyle, The

Woman Suffrage Movement in Canada, XXIII (June

1951), 201.

2. Dawson, R. MacGregor, The

Conscription Crisis of 1944, XXXIV (December 1962),

467.

3. Giraud, Marcel, Histoire du

Canada, XIX (September 1947), 283.

4. Longley, Ronald S., Sir Francis

Hincks: A Study of Canadian Politics, Railways, and

Finance in the Nineteenth Century, XVI (December 1944), 315.

5. Osland, Birger, A Long Pull from

Stavanger: The Reminiscences of a Norwegian Immi-

grant, XVII (September 1945), 261.

6. Pickersgill, J. W., The Mackenzie

King Record, Vol. 1: 1939-1944, XXXIII (September

1961), 355.

7. Savelle, Max, The Diplomatic

History of the Canadian Boundary, 1749-1763, XIII

(March 1941), 96.

8. Somers, Hugh Joseph, The Life and

Times of the Hon. and Rt. Rev. Alexander Macdon-

ell, D.D., First Bishop of Upper

Canada, 1762-1840, IV (June 1932),

300.

9. Thomson, Dale C., Alexander

MacKenzie: Clear Grit, XXXIV (March 1962), 102.

H. The Journal of Southern History:

1. Clark, Thomas D., The Rampaging

Frontier: Manners and Humors of Pioneer Days in

the South and the Middle West, V (August 1939), 398.

2. Jones, M. A., American

Immigration, XXVIII (February 1961), 80.

J. Labor History:

1. Ping Chiu, Chinese Labor in

California, V (Winter 1964), 76.

K. The Mississippi Valley Historical

Review:

1. Adams, William Forbes, Ireland and

Irish Emigration to the New Worldfrom 1815 to

the Famine, XIX (March 1933), 588.

2. Angus, H. F., ed., Canada and Her

Great Neighbor, XXV (December 1938), 437.

3. Ausubel, Hermann, Historians and

Their Craft: A Study of the Presidential Addresses of

the American Historical Association,

1884-1945, XXXVIII (June 1951), 144.

94

OHIO HISTORY

4. Blegen, Theodore C., Norwegian

Migration to America, 1825-1860, XVIII (December

1931), 405.

5. Caughey, John, In Clear and

Present Danger: The Crucial State of Our Freedom, XLV

(September 1958), 353.

6. Child, Clifton J., The

German-Americans in Politics: 1914-1917, XXVI (March 1940),

599.

7. Curti, Merle, Probing Our Past, XLII

(June 1955), 152.

8. --, and Vernon Carstensen, The

University of Wisconsin: A History, 1848-1925, Vol.

1, XXXVI (June 1949), 159.

9. --, The University of Wisconsin: A

History, 1848-1925, Vol. 2, XXXVI (December

1949), 539.

10. Easum, Chester V., Carl Schurz:

Vom deutschen Einwanderer zum Amerikanischen

Staatsmann, XXV (June 1938), 114.

11. Finley, John H., The Coming of

the Scot, XXVII (September 1940), 321.

12. Flenley, R., ed., Essays in

Canadian History Presented to George MacKinnon Wrongfor

His Eighteenth Birthday, XXVII (June 1940), 157.

13. Fox, Dixon Ryan, Ideas in Motion,

XXII (March 1936), 615.

14. Freund, Max, ed. and tr., Gustav

Dresel's Houston Journal: Adventures in North Amer-

ica and Texas, 1837-1841, XLI (March 1955), 710.

15. Gibson, Florence E., The Attitudes

of New York Irish Toward State and National Af-

fairs, 1848-1892, XXXVIII (September 1951), 325.

16. Gjerset, Knut, Norwegian Sailors

in American Waters: A Study in the History of Mari-

time Activity on the Eastern

Seaboard, XX (September 1933), 291.

17. Golden, Harry L. and Martin Rywell, Jews

in American History: Their Contribution to

the United States of America,

1492-1950, XXXVII (March 1951), 689.

18. Golden, John and Viola Brothers

Shore, Stage-Struck John Golden, XVIII (December

1931), 419.

19. Goodale, Katherin, Behind the

Scenes, XVIII (December 1931), 420.

20. Grant, Madison, The Conquest of a

Continent: Or the Expansion of Races in America,

XX (March 1934), 589.

21. Hansen, Marcus L., The Atlantic

Migration, 1607-1860, XXVII (December 1940), 449.

22. --, The Mingling of the Canadian

and American Peoples, XXVII (September 1940),

305.

23. Hill, Frank Ernest, What Is

American? XX (September 1933), 295.

24. Jordan, Emil L., Americans: A New

History of the Peoples Who Settled the Americas,

XXVI (September 1939), 287.

25. Lebeson, Anita Libman, Jewish

Pioneers in America, 1492-1848, XIX (September

1932), 290.

26. Leyburn, James G., The Scotch

Irish: A Social History, XLIX (December 1962), 497.

27. MacKenzie, Norman and L. H. Laing,

eds., Canada and the Law of Nations, XXVI

(June 1939), 128.

28. Marcus, Jacob Pader, ed., Memoirs

of American Jews, 1775-1865, Vols. 1 and 2, XLII

(March 1956), 742.

29. Munro, W. B., American Influences

on Canadian Government, XVII (December 1930),

495.

30. O'Malley, Charles J., It Was News

to Me, XXVI (December 1939), 444.

31. Overdyke, W. Darrell, The

Know-Nothing Party in the South, XXXVIII (June 1951),

117.

32. Peterson, H. C., Propaganda for

War: The Campaign Against American Neutrality,

1914-1917, XXVI (September 1939), 280.

33. Qualey, Carlton C., Norwegian

Settlement in the United States, XXV (June 1938), 105.

Carl Wittke

95

34. Report... by the Stanford School of

Humanities, The Humanities Chart Their Course,

XXXIII (September 1946), 310.

35. Roebling, Johann August, Diary of

My Journey from Muelhausen in Thuringia via Bre-

men to the United States of North

America in the Year 1831, XIX

(September 1932),

508.

36. Sallet, Richard, Russlanddeutsche

Siedlungen in den Vereinigten Staaten, XIX (Septem-

ber 1932), 292.

37. Schuyler, Hamilton, Jr., The

Roeblings: A Century of Engineers, Bridge-Builders and

Industrialists: The Story of Three

Generations of an Illustrious Family, XVIII

(March

1932), 596.

38. Sears, Paul B., Who Are These

Americans? XXVI (September 1939), 287.

39. Stephenson, George M., A History

of American Immigration, 1820-1924, XIII (April

1933), 264.

40. --, The Religious Aspects of

Swedish Immigration: A Study of Immigrant Churches,

XIX (September 1932), 291.

41. Stevens, Thomas Wood, The

Theatrefrom Athens to Broadway, XIX (September 1932),

515.

42. Stondt, John B., Nicolas Martian:

The Adventurous Huguenot, the Military Engineer,

and the Earliest American Ancestor of

George Washington, XX (September

1933), 299.

43. Vagts, Alfred, Deutsch-Amerikanische

Ruckwanderung: Probleme, Phanomene, Statis-

tik, Politik, Soziologie, Biographie,

XLVII (December 1960), 506.

44. Walters, Thorstina, Modern Sagas:

The Story of the Icelanders in North America, XLI

(June 1954), 151.

L. The New England Quarterly:

1. Billington, Ray A., The Protestant

Crusade, 1800-1860, XII (March 1939), 136.

2. Clarke, Mary Patterson, Parliamentary

Privilege in the American Colonies, XVII

(March 1944), 132.

3. Handlin, Oscar, The Uprooted, XXV

(March 1952), 119.

4. McInnis, Edgar W., The Unguarded

Frontier: A History of American-Canadian Rela-

tions, XV (December 1942), 730.

M. Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly:

1. Barnhart, John D., Valley of

Democracy: The Frontier Versus the Plantation in the Ohio

Valley, 1775-1818, LXIII (April 1954), 204.

2. Cox, James M., Journey Through My

Years: An Autobiography, LVI (April 1947), 205.

3. Hamil, Fred Coyne, The Valley of

the Lower Thames, '640-1850, LX (October 1951),

434.

4. Kolehmainen, John I. and George W. Hill,

Haven in the Woods: The Story of the Finns

in Wisconsin, LX (July 1951), 329.

N. Ohio Historical Quarterly:

1. Pollard, James E., William Oxley

Thompson, "Evangel of Education," LXV (April

1956), 195.

2. Weisenburger, Francis P., Ordeal

of Faith: The Crisis of Church-Going America,

1865-1900, LXIX (January 1960), 89.

O. The Scientific Monthly:

1. Toksvig, Signe, Emanuel

Swedenborg, Scientist and Mystic, LXVII (July 1948), 68.

ROBERTA MENDEL

Carl Frederick Wittke:

Versatile Humanist

There're too many do-gooders

and organizers and not enough

quiet humanitarians among us.

Cleveland Sun Press,

November 18, 1971

Native Ohioan Carl Frederick Wittke

distinguished himself in many areas of aca-

deme. At such Ohio institutions of

higher learning as Ohio State University, Ober-

lin, and Western Reserve University, he

is recognized as an outstanding teacher, ad-

ministrator, and mediator. Nationally,

he is remembered as an indefatigable,

forceful, and courageous civil

libertarian and fighter for academic freedom. Inter-

nationally, he is acknowledged as one of

the historians largely responsible for the

development of the cultural aspects of

American immigrant historiography. Before

it was fashionable, he recognized

cultural pluralism-not the melting pot-as the

hallmark of American society. As an

historian and critic Dr. Wittke expressed his

thematic ideas with succinctness, more

than a dash of imagery, and a great deal of

tolerance. His impact was thereby felt

outside as well as inside his own field of

interest.

Dr. Wittke's many accomplishments

reflect a strict but compassionate home life.

Carl Wittke, the senior, was a German

immigrant who, upon landing in the port of

New York, bought a ticket as far west as

his money would stretch. This happened to

be Columbus, Ohio. It was here, on

November 13, 1892, that a son, Carl Frederick,

was born. While Carl senior was not a

formally educated man and had no degree in

engineering, he was a "mechanical

genius." Through a combination of aptitude and

diligence, he started a factory and

prospered enough to provide educational op-

portunities and adequate comforts for

his family.1 As all immigrants, Wittke

struggled to combine the ways of his

adopted country with familiar customs of the

Old Country without losing the flavor

and substance of the latter. His son's work,

which covered a span of forty-nine

years, 1921-1970, is a testament to the fact that

the father successfully instilled a deep

and abiding respect and love of his German

1. Interview with Thya Johnson,

September 13, 1971. Miss Johnson was Dr. Wittke's secretary for

twenty-four years. See also C. H.

Cramer, "Speech Honoring Dr. Wittke," March 31, 1971, p. 3, in Case-

Western Reserve University Library.

Ms. Mendel is a lecturer, teacher, and

author from the Cleveland area. She is presently on the staff of

Cuyahoga Community College-Eastern

Campus.

(614) 297-2300