Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

CHARLOTTE W. DUDLEY

Jared Mansfield: United

States Surveyor General

Jared Mansfield (1759-1830), one of the

first men of science in the

republic's formative years, made a

significant contribution to post-

Revolutionary Ohio. Appointed by

President Thomas Jefferson in 1803

to replace General Rufus Putnam as

Surveyor General, Mansfield re-

mained in the post for nine years,

resigning in 1812 when fresh Indian

uprisings made further surveys

impractical and dangerous. During his

term of office Mansfield with his wife

and family lived successively at

Marietta (1803-1805), at Ludlow Station

east of Cincinnati (1805-1809),

and at Bates' Place, also near

Cincinnati (1809-1812). From these loca-

tions as headquarters, he ran several of

the meridian and base lines on

which surveys of the public lands

throughout the Northwest Territory

were based. His unique contribution to

the surveys in this early period

was his ability to determine meridian

and base lines accurately by

astronomical observations: in effect, he

adapted principles of celestial

navigation to the determination of

longitude and latitude on land. His

familiarity with navigation was due to

his being the son of a sea captain,

Stephen Mansfield, and to his

mathematical and scientific studies at

Yale College.l

The essential links between the American

Revolution and Mansfield's

work in Ohio were both ideological and

practical. He shared Jefferson's

political philosophy and undoubtedly

believed in the President's vision

of a democratic society.2 If

it may be said that Jefferson was one of the

chief "architects" of a new

nation based in part upon freedom for

ordinary men to own and improve land,

then Jared Mansfield may be

1. Biographical details on Jared

Mansfield may be found in the following sources:

George Cullum, "Jared

Mansfield," Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates

of the United States Military Academy

(New York, 1868), I, 77; Alois F.

Kovarik, "Jared

Mansfield," Dictionary of

American Biography (New York, 1928-1937), XII, 256-57;

Edward D. Mansfield, Personal

Memories, Social, Political and Literary, with Sketches

of Many Noted People, 1803-1843 (Cincinnati, 1879), 1-47 (hereafter cited as E.

Mansfield,

Personal Memories); Horace Mansfield, Descendants of Richard and Gillian Mansfield

Who Settled in New Haven, 1639 (New Haven, 1885), 43-45 (hereafter cited as H.

Mansfield, Mansfield Genealogy); and

Roswell Park, History of West Point (Philadelphia,

1840), 54-55, 59, 68.

2. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories,

5-6.

|

232 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

considered one of his hand-picked "contractors." Mansfield's work helped implement the revolutionary ideas that all men had a right to a portion of land, not just eldest sons, and that the government would make access to land relatively easy for settlers, rather than use it as a means of enriching the United States Treasury. Working closely with Commissioners of the Land Office and Receivers of Public Money, Mansfield benefitted in a practical way the common people beginning to pour over the Alleghenies to cultivate the fertile lands of the Ohio Valley.3 Few histories of Ohio give more than cursory attention to Mansfield's contribution to the state. The naming of the city of Mansfield after him in 1808 is sometimes the only point included.4 The significance of his role

3. Beverley W. Bond, Jr., The Civilization of the Old Northwest, A Study of Political, Social and Economic Development, 1788-1812 (New York, 1934), 278, 315. 4. Ohio, Work Projects Administration, The Ohio Guide (New York, 1940), 289. |

Jared Mansfield

233

in helping to bring into being

Jefferson's dream of new states founded on

democratic principles is largely

overlooked.5 To be sure, Mansfield's

work benefitted all of the Northwest

Territory, and ultimately the or-

derly settlement of the entire nation;

but it was in Ohio that his methods

were first used, and it was from Ohio

that he superintended the complex

public business of the Surveyor General's

office. The purpose of this

article is to bring into clearer view

the person and character of Jared

Mansfield as he labored to bring order

out of chaos in the land surveys of

the Northwest Territory.

Born in New Haven in 1759, Jared

Mansfield had been educated at

Yale, graduating with the class of 1777,

and after several years of

graduate work had become a school

teacher in New Haven and

Philadelphia. His father died in

1774,just as the Revolutionary War was

beginning, and the young Mansfield was

forced to live at home for a time

to help his mother with the care of a

younger brother and two sisters. In

1800, however, he married Elizabeth

Phipps, daughter of an American

naval officer.6 The following

year he wrote and had printed a series of

scientific papers, entitled Essays

Mathematical and Physical, which

were highly instrumental in the further

development of his career.7

According to his son's memoirs, Essays

was an original work, and but a few

copies were sold; for there were but few men

in the country who could understand it.

The book, however, established his

reputation as a man of science, and

greatly influenced his after life. Abraham

Baldwin [a former student of Jared

Mansfield's] was, at that time, Senator from

Georgia, and brought this book to the

notice of Mr. Jefferson, who was fond of

science and scientific men. The

consequence was, that my father became a

captain of engineers, appointed by Mr.

Jefferson, with a view of his becoming

one of the professors at the West Point

Military Academy, then established by

law.8

Mansfield and his wife, Elizabeth,

together with their infant son, moved

to West Point in the spring of 1802.9

They were comfortably situated

5. The following Ohio histories have

been examined in a search for mention of Jared

Mansfield: John D. Barnhart, Valley

of Democracy: The Frontier versus the Plantation in

the Ohio Valley, 1775-1818 (Bloomington, 1953); Beverley W. Bond, Jr., The

Foundations

of Ohio (Columbus, 1941); Rufus King, Ohio, First Fruits of

the Ordinance of 1787

(Boston, 1888); E. O. Randall and D. J.

Ryan, History of Ohio, 5 vols. (New York, 1912);

William T. Utter, The Frontier State:

1803-1825, vol. II of A History of the State of Ohio

(Columbus, 1942); Nevin O. Winter, A

History of Northwest Ohio (Chicago, 1917).

6. H. Mansfield, Mansfield Genealogy,

28, 43-45.

7. Jared Mansfield, Essays

Mathematical and Physical (New Haven, 1801).

8. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories, 2-3;

Abraham Baldwin to J. Mansfield, April 4,

1802, H. Dearborn to J. Mansfield, May

4, 1802, The Papers of Jared Mansfield, Ohio

Historical Society (hereafter cited as

Mansfield Papers, OHS).

9. H. Mansfield, Mansfield Genealogy,

77.

234 OHIO HISTORY

there when a new, unsolicited

appointment came in the Summer of 1803

from President Jefferson, that of

Surveyor General of the United States.

This second presidential appointment in

less than two years reflects

how Mansfield must have fit within

Jefferson's overall plans for the old

Northwest Territory. In March of 1803

Ohio became the first state

carved out of the Territory. Danger from

Indian uprisings had subsided

in the portions of Ohio south of the

Greene Ville Treaty Line, and follow-

ing the Treaty of Fort Wayne in June of

that year there were prospects of

further extinguishing the Indian titles

in the Indiana Territory.10 The

Louisiana Purchase, also concluded in

1803, promised outlets via the

Mississippi to New Orleans for the flow

of goods from interior regions to

the East Coast. The time was favorable,

therefore, for Jefferson to push

forward a long-cherished vision of the

creation of several more states in

the old Northwest Territory.11

As for the incumbent Surveyor General,

Rufus Putnam, Jefferson felt

constrained to replace him. He may have

found Putnam a political

adversary, because the General had been

a leader of the Federalists in

Marietta who opposed statehood for Ohio.

12 For scientific reasons, too,

Putnam did not meet Jefferson's

standards. As Mansfield's son Edward

later wrote, "Mr. Jefferson became

annoyed by the fact that the public

surveys were going wrong,.. . for the

accuracy of the surveys depended

upon establishing meridian lines with

base lines at right angles to

them."13 Jefferson may

have remembered, too, that Mansfield's vol-

ume of Essays contained sections

devoted to the solution of problems of

latitude and longitude, applicable on

land as well as at sea.14

Although Congress was not in session in

the summer of 1803, Jeffer-

son exercised his constitutional right

to appoint Jared Mansfield Sur-

veyor General. When Congress reconvened

in the fall of 1803, Mansfield

was formally nominated, on November 11,

and confirmed by the Senate

on November 15. He was instructed to

"survey Ohio and the lands north

of the Ohio River."15 Later,

the scope of his work was broadened to

include the Indiana and Illinois

Territories.16

10. Utter, The Frontier State, 31;

U. S. National Archives, The Territorial Papers of the

United States, edited by Clarence E. Carter (Washington, D. C., 1940),

VII, 173, n. 47

(hereafter cited as Carter, ed., Territorial

Papers).

11. Utter, The Frontier State, 66

ff.; William D. Pattison, Beginnings of the American

Rectangular Land Survey System,

1784-1800 (Chicago, 1957), 15-36.

12. Utter, The Frontier State, 7.

13. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories, 3.

14. J. Mansfield, Essays Mathematical

and Physical, 74-84, 105, 108-45.

15. Senate Executive Journal, I, 453,

455, cited in Carter, ed., Territorial Papers, VII,

191, n. 86.

16. Carter, ed., Territorial Papers, VII,

173, 174; Ray Allen Billington, Westward

Expansion (New York, 1960), 267.

Jared Mansfield

235

A letter by Mansfield written in August

1803 and addressed to Colonel

William Lyon, husband of his cousin,

Lois Mansfield, expressed both

his misgivings and his pleasure at the

President's request. "He who once

commits himself to the Vortex of public

life," Mansfield began,

is liable to be hunted in any direction:

tangential, vertical, horizontal, central,

excentral, etc. I have been lately called

by Government to move in a different

orbit...

Though I feel much gratitude towards

those who have designated me to a

lucrative office under the U. States

Government, I shall notwithstanding reject

the offer, if my friends should start

objections which are more powerful than any

which suggest themselves to my mind. It

is certain that I never sought for or

desired any public employment, and

though this which I hold, and the one

offered, came without solicitation, I

would with pleasure bid adieu to them, if I

were sure of obtaining a maintenance for

my family without the irksome, and I

may say pitiful means of

schoolkeeping-which in N. Haven and other places is

held in contempt, though in my opinion

it merits the highest consideration of

Society. I have nearly worn myself out

in this business, and have it is true

Obtained some reputation as a teacher.

This is flattering to my vanity; for

sometimes I have been led to suppose

myself a Cypher, and was glad to think

that I was in some repute among Sailors,

boys, etc....

The business I suppose will be

principally Astronomic surveys of the principal

points in the U. States, such as were

lately begun by [Andrew] Ellicott, but not

as yet finished. It was my Ability in

this business among the corps of Engineers,

which recommended me to the Secretary of

War, and from thence to the

President of the U. States. Whether I

accept this business or not it is certainly

very flattering to me that Gentlemen of

the Army, entire strangers to me should,

in less than the space of one year have

given me such a good report; Indeed, my

friend, I am flattered more with this

than all the appointments in the World ....17

Mansfield was by temperament a scholar

and mathematician, and

therefore somewhat reluctant to plunge

into public service. He was

aware that going to frontier Ohio to

engage in a responsible public

business "would give him more or

less of trouble and vexation."18

But

the promise of financial security and

future promotions was an induce-

ment to go. There was also the fact that

it was an honor to be chosen.

Mansfield was the only man, according to

Edward's report, who had

been appointed to an important public

office solely on the ground of his

scientific attainments. "This was

due to Mr. Jefferson who, if not

himself a man of science, was really a

friend of science."19

17. J. Mansfield to Col. William Lyon,

August 12, 1803, Mansfield Papers, OHS.

18. According to Mrs. Mansfield, her

husband decided to accept the offer, although in

her opinion "Our Situation at the

point was perfectly agreeable. I fear we shall not profit by

the exchange we have made." They

sold most of their furniture at auction before leaving

West Point, and took nothing with them but their linen.

Elizabeth Mansfield to H. Sisson,

September 11, 1803, Mansfield Papers,

OHS.

19. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories, 3.

236 OHIO HISTORY

The appointment, of course, was

accepted. The Mansfields' trip from

New Haven to Marietta was described by

Elizabeth Mansfield in a letter

to Jared's niece, Harriet Sisson. She

reported that they took the mail

stage to Philadelphia, traveling all

night, and arrived there forty-eight

hours after leaving New Haven. Mansfield

hired a "coachee and one

span of horses" to take them to

Pittsburgh, which she said was a

comfortable but very expensive way of

traveling. Crossing the Al-

legheny Mountains caused her a great

deal of anxiety and apprehension,

and there was a lack of comfortable

places to stay at night. Yet they were

not detained by bad weather or ill

health. When they reached Pittsburgh

they found the Ohio River was so low

that they had to hire the same

carriage to take them to Wheeling. There

a friend of Mansfield's met

them and was extremely helpful in

arranging for them to get down the

river. Instead of going in a large and

convenient boat, they went in a little

skiff, rowed by two men. At night they

lodged in little cabins on the

banks of the river. On the third night

they arrived at Marietta, and

"happy indeed did I feel

myself," Elizabeth wrote, "to be once more in

a place of safety and among New England

people."20

Two months later, in February 1804,

Elizabeth Mansfield again wrote

to Harriet Sisson, describing their

house in Marietta and its furnishings,

as well as her fortune in obtaining a

good servant, setting her free for

social occupations.21 That

same month Jared Mansfield wrote to his

favorite confidant, William Lyon,

describing the political situation he

encountered in Marietta. "The

variety of scenes through which I have

passed," he observed,

since seeing you, & the multiplicity

of affairs which have occupied my attention,

would hardly permit me to devote much

time to a correspondence with my

private acquaintances. I have also

experienced much illness & lowness of

spirits .... These circumstances

together with the malevolence of party rage

have produced a complication of evils,

which have not yet entirely destroyed

me. Indeed I find myself more elevated

in proportion as the difficulties increase.

On the first news of their attacking me

in the Eastern papers, on account of my

appointment, I was somewhat agitated,

from the idea of my great distance & the

total impossibility of conveying truths

instead of lies. Genl Putnam is wholly

incompetent to the business for which I

was selected. He has had everything

which he could do, & is well enough

satisfied. But if he were the greatest

scientific character in the Union, his

age would not permit him to move to those

distant countries, where the Surveyor

General's business is to be conducted. He

& I are on perfect terms of

intimacy. It is not he, but the abusive scriblers who

wish to make a ... [?] of this business

against the present Administration who

make all the mischief....

20. Elizabeth Mansfield to H. Sisson,

December 1, 1803, Mansfield Papers, OHS.

21. Elizabeth Mansfield to H. Sisson,

February 5, 1804, Ibid.

Jared Mansfield

237

We find here a good society-but small.

Political concerns have somewhat

poisoned it, as well as in other parts.

This country two years ago was federal &

almost the only one of that cast. It is

now republican in spite of the most

strenuous efforts of a number of men who

have always considered themselves a

kind of Noblesse. The measures of the

present Administration, overweigh the

abuse & calumny heaped on them. The

Acquisition of Louisiana, the economy

& frugality practiced are very

congenial to the feelings of the hardy countrymen.

I perceive by some late regulations of

congress that they are about to cut out

work enough for a Surveyor General. The

country about Vincennes on the

Wabash, & another tract about the

confluence of the Ohio & Mississippi are to

be surveyed. In doing this if I do not

give entire satisfaction, I should wish to be

stigmatized, but the public will find,

that there will be no Occasion for its being

resurveyed in consequence of blunders,

twice or thrice, as was the case in the

Surveys executed by my Predecessor.

Whenever I shall be informed of the full

extent of my business, I shall be able

to inform you & others, what prospects [for

employment] there may be for my friends

.. "22

Edward Mansfield, in describing his

father's relationship with Gen-

eral Putnam, noted that although the

latter had been a Revolutionary

officer and a Federalist, while his

father was a Republican and a partisan

of Jefferson, the political tensions

soon abated. "The people of Marietta

were intelligent, upright people,"

he wrote, "and my father not one to

quarrel without cause. The Putnams were

polite, and my parents passed

two years at Marietta pleasantly and happily."23

In accepting the new

post, Jared and Elizabeth Mansfield were

willing to face personal risk

and endure unjustified criticism.

The Mansfields moved from Marietta to

Cincinnati in October of

1805. Cincinnati then was a dirty little

village. The chief houses were on

Front Street, from Broadway to Sycamore,

and were two-story, painted

white. After just a few days, the family

moved to Ludlow Station, built

by Colonel Israel Ludlow, one of the

original proprietors of Cincinnati

and chief surveyor of the Symmes tract.

The "station" was a large

two-story house, with wings, one of the

largest then at Cincinnati.

Mansfield took one of the wings as the

office of the Surveyor General,

and the other wing was used as a

kitchen.24

Soon after the move, Mansfield wrote to

Colonel Lyon of his grief

over the loss of one of his deputy

surveyors, David Sanford, by acciden-

tal drowning: ". .. the business

... for which he was best adapted was

that of Astronomical Observations.

Unfortunately, our Instruments

22. J. Mansfield to Col. Lyon, February

20, 1804, Ibid.; as to Putnam's incompetence,

see Malcom Rohrbough, The Land Office

Business (New York, 1968), 34, where the

necessity of resurveying all of Putnam's

work for the past three years is discussed.

23. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories,

5-6.

24. Ibid., 19-21.

238 OHIO HISTORY

have been detained in England, for 18

months beyond the time expected.

I had just received the account of their

arrival at N. York, and was just

about to communicate the intelligence to

Mr. Sanford when a messenger

arrived with the account of his

Death." Mansfield went on to say that

Dr. Timothy Dwight, then President of

Yale, "and the gentlemen of

College . . . will feel the deepest

regret for the loss of one who in every

respect was calculated to do honour to

his instructors and to the institu-

tion." 25

The astronomical instruments mentioned

were, of course, vital to the

conduct of Mansfield's surveys. In fact,

the type and quality of instru-

ments he elected to use distinguished

his surveys from those of his

precursor. Since in his administration

Jefferson tried to observe princi-

ples of economy, he used his own

contingency fund, rather than money

appropriated by Congress, to pay for the

instruments. They were made

by a well-known British firm, but did

not reach the United States until

nearly three years after they were

ordered. Arriving in New York in

October 1805, they were further delayed

by a malignant fever in the city

and by winter in the Allegheny

Mountains.26 Jared Mansfield's son,

Edward, sketched the importance of these

instruments and the histori-

cal background of his father's

astronomical work during an 1845 address

he delivered before the Cincinnati

Astronomical Society. "Official

documents show," he began,

that astronomical observations were a

part of the duties of the Surveyor General,

in that early settlement of the Ohio

Valley. He was directed, if possible, to

determine the southern extremity of Lake

Michigan, the western extremity of

Lake Erie, the confluence of the Ohio

with the Mississippi, and the western

boundary of the Connecticut Reserve. For

this purpose astronomical instru-

ments were necessary.... They arrived in

Cincinnati in 1805 or 6; were placed in

the house of the Surveyor General and

constituted, I believe, the first real

observatory erected West of the

Allegheny Mountains.

There, during a series of years,

numerous and interesting astronomical obser-

vations were made.... The meridian first

surveyed with scientific accuracy was

called the second principal meridian,

and is that which commences at the

confluence of Little Blue River with the

Ohio, in the state of Indiana .... By this

meridian and the principal base line at

right angles to it, nearly the whole state of

Indiana and a portion of Illinois were

surveyed.27

25. J. Mansfield to Col. Lyon, November

19, 1805, Mansfield Papers, OHS.

26. The invoice for these instruments

listed: "A three-feet Reflecting Telescope,

mounted in the best manner, with powers,

lever-motion, Wollaston's Catalogue of the

Stars, Mackelyne's Observations and

Tables, A thirty inch Portable Transit Instrument,

answering also the purpose of an Equal

Altitude Instrument and Therdolete, An As-

tronomical Pendulum Clock." Quoted

by E. Mansfield, "The Annual Address Delivered

before the Cincinnati Astronomical

Society, June, 1845," in Lectures (Cincinnati, 1845),

note f, 30, 31.

27. Ibid. 15-16.

Jared Mansfield

239

The problem which faced Jared Mansfield

in surveying the Indiana

Territory, as Edward indicated, was

complex. If Mansfield had simply

extended the lines used in Ohio, it

would have produced confusion due

to the seven different surveying

patterns used by Putnam and his own

men. Further, Mansfield desired to

establish a precedent which could be

used for the whole of Indiana as well as

the rest of the old Northwest

Territory. At the same time, such a

precedent needed to be flexible

enough to take into account the problems

of surveying the global surface

of the earth as if it were a flat map.

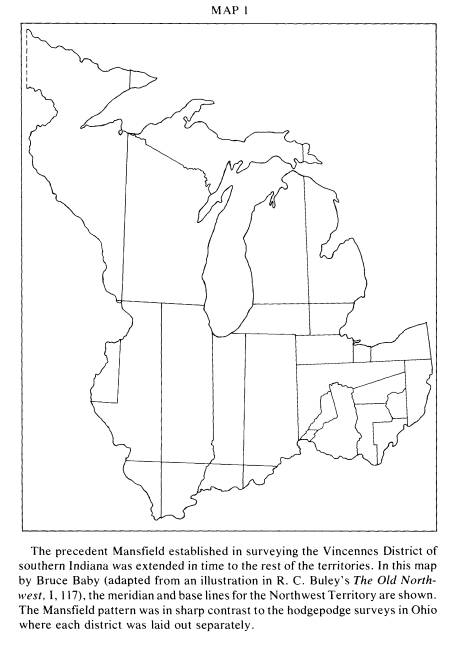

Finally, in 1804, Mansfield decided to

lay down an arbitrary meridian, which he

called the second principal

meridian, and an intersecting east-west

base line in what is now southern

Indiana. From these two lines all other

surveys would be made. For later

surveys of the Northwest, three more

principal meridians and additional

base lines were added as necessary (see

Map 1). The precedent would in

time be extended to the rest of the then

unsurveyed United States.28

According to Edward, this system

may be called the astronomical system

of surveying. The whole subdivision of

lands, surveys in the northwest states,

and those west of the Mississippi, with

very little exception, is made in this

manner, and depends on mathematical lines

connected by astronomical observations.

It is not merely a beautiful plan, but it

is the best possible security to titles,

and the surest prevention of litigation. In

reference to this great utility of

scientific surveys, Mr. [Return Jonathan] Meigs,

Commissioner of the Land Office,

remarked that "a man brings the heavens to

the earth for his convenience. A few

geographical positions on the map of the

public surveys being determined by

astronomical observations, it is with little

difficulty that latitude and longitude

of every farm, and of every log hut and court

house may be ascertained with

precision."29

Jared Mansfield personally reflected

upon his success in Indiana in a

letter he sent during July 1807 to his

good friend Colonel Lyon. "I avail

myself of this opportunity," he

began,

to transmit to you ... a Plan of the

Indiana Territory, as far as it is known by our

surveys, which on account of the

innumerable meridianal and parallel lines,

actually run and marked, as well as of

the courses of all rivers and streams of any

considerable size, taken by the

Surveyors, supersede the necessity of ever

arriving at more perfect material for a

general topography of that part which has

been surveyed. Cities, Towns and

Villages, Roads, etc. may be added according

to the progress of improvement, but no

further improvement can be made, than

to copy more correctly than probably we

have done, the surveys in this office, at

28. For further information, see

Pattison, American Rectangular Land Survey System,

210-12, and R. Carlyle Buley, The Old

Northwest: Pioneer Period, 1815-1840, 2 vols.

(Bloomington, 1951),I, 117-23.

29. E. Mansfield, "Address to

Cincinnati Astronomical Society," 14-16; see also J.

Meigs, "How the Public Lands Were

Surveyed," Niles' Weekly Register, July 24, 1819,

363.

|

240 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

Jared Mansfield

241

least I may say, no improvement can be

made for general purposes and for a map

of an ordinary size. For we have the

description and the local situation of various

parts to such a degree of minuteness as

to be invisible on a general map. There

are wanting some particulars for the

perfection of the Geography, even of those

parts which have been surveyed by chain

and compass, which we should have

long since furnished, had we received as

was expected, from England, the

proper Astronomical Instruments for the

purpose. The precise Latitudes and

Longitudes of the most important points

such as the Mouth of the Ohio, the

Wabash, the Illinois, the Southern

Extremity of Michigan etc. are still Desidera-

ta. As now put down, they are drawn from an estimate

founded on Surveyors

measures reduced to Geographical

Measure, and may be presumed tolerably

correct, but we want to verify them and

to determine the outlines of the whole N.

Western Territory, and to estimate its

Contents, which has never been done,

otherwise than by conjecture.30

Many notable people passed through the

Surveyor General's house at

Ludlow Station in the years between 1805

and 1809. As Edward Mans-

field put it, "at that time, a

gentleman's country house was a semi-

hotel. Taverns were scarce, and it would

have been a breach of hospital-

ity not to have received and entertained

any respectable looking person

who came along."31 Some

of the visitors were deputy surveyors, a

number of whom became famous. Among

these men who helped Jared

Mansfield survey the great body of lands

to the north and west of

Cincinnati were Thomas Worthington,

Lewis Cass, and Ethan Allen

Brown.32 In connection with

notable or interesting visitors, Edward

remembered with particular interest the

day when the Indian chief Little

Turtle entered Ludlow Station for a

conference with his father. Little

Turtle signed the treaty of Greene Ville

with the chiefs often tribes, and

never again appeared on the field of

battle. A few years after that... he

came . . . to my father's house . . . to

arrange for the survey of the

Greenville line. As he rode away from

the house, in the declining sun, I

might, without any violent stretch of imagination

have seemed to see the

last great spirit of the Indian race

leaving the land of his fathers.... "33

In the fall of 1809, Mansfield rented a

house called Bates' Place, two

miles closer to Cincinnati than Ludlow

Station. The Mansfields re-

mained there three years. Edward

Mansfield paints the scene:

We were really on the frontier, my

father and his surveyors being in the

wilderness where is now the most

populous portion of Indiana. My father's

business varied little. ... He was

pursuing intently the business he was

30. J. Mansfield to Col. Lyon, July 5,

1807, Mansfield Papers, OHS.

31. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories, 33.

32. Ibid., 32; Family Register of Gerret Van Sweringen and

Descendants (Washington,

1894), 16. Edward Mansfield would later

marry one of Worthington's daughters (Mar-

garet).

33. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories,

25, 26.

242 OHIO HISTORY

employed to do. His surveyors were out

through Northwestern Ohio and India-

na, while he, himself, was recording the

work, and making astronomical obser-

vations.34

No further personal letters of Jared

Mansfield's are available for this

final period in Cincinnati, until close

to the end, when the following one,

to his wife's brother-in-law, Joseph

Mix, describes the state of affairs

just before the War of 1812:

Cincinnati Jan 24th 1812

Dr Sir,

It is now a long time since I have

written to you and almost as long since, I have

received anything from you ....

Leaving excuses to the air ... we are

now in a very comfortable situation as to

health. I have felt very little of my

old complaints ... Betsey and the children are

uncommonly hearty ... I might ...

mention one occurence of a very extraordi-

nary nature, viz. Earthquakes, which

we have experienced here more or less at

intervals since the 16th of December

last. ... [Mansfield went on to describe the

severity and duration of the quakes at

some length. He turned then to the subject

of impending war.] We have had other

matters of alarms since I wrote you....

The Indians on the Wabash, under a

leader called the Prophet have attacked our

troops under the command of General

Harrison of the Ind. Territory, but have

been defeated....

This man is an Imposter who has assumed

the same arts of seducing the

Indians as have been used before in the

World by pretenders to inspiration, and

communication with the Great Spirit. One

really inspired... could not advise to

bloodshed. This alone, with civilized

people, would be evidence sufficient of his

imposture, but what can we expect from

poor untutored Indians? They would be

oftener deceived, were they not

possessed of a natural, inherent vigor of mind,

which appears to equal if not surpass

that of almost any other people ....

War, War, War, appears now to be the

topic. I was in hopes, that I should

never see any more of it in my time; but

the people, of this part of the country,

appear to prefer it, to a relinquishment

of our rights, and I have no doubt, that the

Army of 25,000 men might nearly be

raised, this side of the mountains, especially

as 160 acres of land is offered as a

bounty. I hope England will come to her sense,

and not think of holding out against

reason. ... I do not expect war would be so

calamitous as before, because there is

no probability of an invasion, but it still

would be calamitous, as numbers must

lose their lives, and the whole country

must lose property. Let us hope for a

happier issue.

I expect the Corps of Engineers will be

augmented, so as to embrace Profes-

sorships of the Mathematics and Natural

and Experimental Philosophy. In such

case I shall join it at W. Point, or

somewhere in the Vicinity, and you may rely on

my being at N. Haven in that event....

Jared Mansfield35

Mansfield had good reason to expect that

a position would be awaiting

34. Ibid., 41, 42, 44, 45.

35. J. Mansfield to Major J. Mix,

January 24, 1812, Mansfield Papers, OHS.

Jared Mansfield 243

him back at West Point, for as early as

March 20, 1809, Jonathan

Williams, Lieutenant Colonel in the

Corps of Engineers, and then

Superintendent of the Military Academy,

wrote to tell him that though a

bill relative to improvements in the

training of cadets had lost in Con-

gress, "your rank in the Corps is

doubtless settled, and I wish you were

here to take the direction of the Academy."36

This letter, coming as it

did in the spring of 1809, may have

triggered in Jared Mansfield a desire

to return to teaching. But since the

legislation for reorganization of the

Academy was not to pass Congress until

1812, Mansfield made up his

mind to return to Ohio. When he

eventually returned to West Point, it

was to become Professor of Mathematics

and Natural and Experimental

Philosophy, just as he had intimated to

Major Mix; Mansfield never did

assume the direction of the Academy,

although under his persistent and

persuasive influence its academic

standards were raised.37 He resumed

his teaching career in 1814 and remained

at West Point until his retire-

ment in 1828. He and his wife then

returned to Cincinnati to live. He

died, while on a visit to New Haven,

February 3, 1830.38

Edward Mansfield reported that his

father had "fulfilled his office as

surveyor general" when the family

prepared to return east in the early

part of June 1812.39 Whether Jared

Mansfield had fulfilled all the direc-

tives which had reached him from the

Secretary of the Treasury would

require further study in original

documents, but historian William Patti-

son credits Mansfield with a number of

accomplishments. They include

his laying down principal meridian and

base lines in southern Indiana;

establishing a framework which offered a

practical solution to the con-

flict between rectangularity and

convergency; enforcing the Land Act of

1796 in making meridian lines and others

adhere to true north; develop-

ing the closure of surveyed lines upon

one another; terminating the

confusing practice of basing township

numbers on the Ohio River,

instead making them consistent with a

uniform base line; and being the

first to envision the extension of

rectangular surveying over a great

area.40 Another assignment

which he fulfilled, not mentioned so far, was

to help settle a dispute between the

Connecticut Land Company and the

Federal Government as to the location of

the forty-first parallel of

36. Col. Jonathan Williams to J.

Mansfield, March 20, 1809, The Papers of Jared

Mansfield, United States Military

Academy, West Point (hereafter cited as Mansfield

Papers, USMA).

37. See Mansfield Papers, USMA.

38. H. Mansfield, Mansfield

Genealogy, 44.

39. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories,

48.

40. Pattison, American Rectangular

Land Survey System, Fig. 8, Fig. 16, and pp.

10-12, 215, 216, 227.

244 OHIO HISTORY

latitude. He examined it, about the year

1810, and advised that it not be

disturbed.41 In his spare time,

Mansfield cooperated with his friend Dr.

Daniel Drake in keeping meteorological

records between 1807 and

1812.42 His scientific interests reached

beyond his job.

One way of evaluating a man's work is to

ask how well he fulfilled his

own intentions. In 1826, fourteen years

after resigning from the Sur-

veyor Generalship, Jared Mansfield in a

letter to Edward wrote his own

appraisal of his conduct of that office.

It was occasioned by his being

threatened with a lawsuit brought

against him by two or three former

deputy surveyors because of alleged financial

losses they had incurred

while under his employment. The tone of

Jared's letter to Edward was

indignant and defensive, but the

accompanying statement was a well-

organized review of his work. "My

mission," he remarked.

as Surveyor Genl to the Western Country,

had two principal objects in view,

both of which, I have accomplished to

the entire satisfaction & even applause of

the Government, & of all men of

intelligence, who are acquainted with the

surveys as they were conducted in Ohio

& other parts. The first object was to

establish on scientific principles a

system of surveying, which would prevent the

endless interference of claims, to

remedy which Congress had been appealed to,

& though they passed a great number

of laws, no effectual remedy could be had,

to establish the Geography of the

Country by Astronomical Observations, & fix

topographical boundaries. 2d to reduce

the expense of the common Compass

running of lines, for which the maximum

price of 3$ per mile had always been

given, especially in places of easy

access, where provisions were cheap. The

proposition of reducing the price caused

the old Surveyors, who had been

accustomed to 3$ per mile, to grumble.

... I was enabled ... to reduce the price

. .. to 2 1/2 to 2$. There were some

surveys, however, which would not admit of

this reduction on account of their

[personal financial] difficulty. .. .43

The practice of advancing payment to

deputy surveyors was com-

mon, and only after 1844 did the

government agree to pay the surveyors

directly. In Mansfield's time the

deputies' accounts were settled by the

Surveyors General from funds placed to

their credit by the Government.

But to provision themselves for weeks in

the woods, surveyors had to

have money. Since many of them were, as

Jared Mansfield says, poor

men, they were not able to afford such

outlays of capital without help.44

It is a tribute to his sense of fairness

and his concern for his deputies

41. Charles Whittlesey, "Surveys of

the Public Lands in Ohio," Tract #61 of the

Western Reserve and Northern Ohio

Historical Society, in Henry Howe, Historica

Collections of Ohio, 2 vols. (Cincinnati, 1908), I, 135.

42. Buley, The Old Northwest: Pioneer

Period, I, 200.

43. J. Mansfield to E. D. Mansfield,

February 6, 1826, Mansfield Papers, OHS.

44. Lowell O. Stewart, Public Land

Surveys (Ames, Iowa, 1935), 50, 51.

Jared Mansfield

245

welfare that Mansfield was willing to

advance money to them, appar-

ently without charging interest.

This article has attempted to show that

Jared Mansfield made it

possible for the rectangular survey

system to be carried across the

American continent. His method of

establishing principal meridians and

base lines accurately furnished

reference points for a whole century of

westward survey and settlement.45

We have reviewed only briefly and in

highly condensed form the

historical evidence substantiating our

claim. Our focus has been on

previously unpublished personal

correspondence, revealing the nature

of the man who was Surveyor General in

Ohio in the early nineteenth

century. His letters show him to have

been conscientious, patriotic,

thrifty, diligent, and courageous in the

fulfillment of his office. They

show him also to have been sensitive,

generous, empathetic, and a

loving husband and father. Occasionally,

he was testy or resentful in the

face of criticism. But it is

characteristic of scholarly men that they are

also thin-skinned. It was said of him

that he had a good sense of humor

and a hearty laugh.46 Edward

Mansfield's comment on the portrait of his

father by Thomas Sully was that it shows

a man of a "calm and abstract

expression."47

In his conduct of the office of the

Surveyor General between 1803 and

1812, Mansfield gave substance to

Jefferson's ideal of democratic op-

portunity for even the humblest man. Of

course he did not work alone,

but in collaboration with many others.

Jefferson was among the giants of

our nation who cherished a revolutionary

idea that the thirteen original

colonies might become a farflung nation

of independent citizens, living

in states which would be created

systematically out of the wilderness.

Jared Mansfield responded affirmatively

to the challenge of serving a

new government, based on such

principles. He undoubtedly felt, with so

many of his contemporaries, the lure of

Western lands. He knew he had

the capability, as a student of

astronomy and navigation, to fulfill what

was asked of him. He was willing to set

aside personal preferences as to

45. Rohrbough, The Land Office Business,

55.

46. Howe, Historical Collections of

Ohio, II, 768. Mansfield had many life-long friend-

ships among men in the scientific and

political communities. His love of his family may be

judged from a letter he wrote to his

wife, "Betsey," when he was absent in the field: "I feel

a blank & gloomey void, which

nothing but my dear little family can supply, & do very

much wonder, how some people can content

themselves in similar circumstances. I am

sure I should be extremely miserable,

were it not for a hope of seeing you & my dear boy

soon" (J. Mansfield to Elizabeth

Mansfield, October 27, 1804, Mansfield Papers, OHS).

Among his family at Cincinnati were his

son Edward, his daughter Mary Ann, and his

nephews John Fenno Mansfield and Joseph

G. Totten. Joseph later had a long and

illustrious career in the Army Corps of

Engineers (Cullum, Biographical Register, 94-96).

47. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories, 74.

246 OHIO HISTORY

occupation and place of residence to

help put Jefferson's vision of the

creation of new states on a scientific

footing, and to serve the interests of

settlers intending to go West into the

new land.

One can picture Mansfield working with

quill pen, and often by

candlelight, recording his surveyors'

field notes, or at his telescope

taking necessary sightings on the stars.

One can also imagine the patient

labor required to keep up a never-ending

correspondence with sur-

veyors, including the principal deputy

surveyors who were in charge of

various regions, such as at Vincennes or

Kaskaskia, as well as to

maintain a frequent exchange of letters

with Albert Gallatin, Secretary

of the Treasury.

As he worked, Mansfield was tracing what

proved to be indelible

marks on the American landscape.48 He

worked in post-Revolutionary

Ohio, and from his Cincinnati

headquarters his remarkably conceived

system spread into the evolving states

of Indiana and Illinois. Other men

would take up where he left off, and

with gradual improvements the

surveys of the public lands would

continue to the Pacific Coast, still

governed by meridians and base lines.49

Ohio may well claim Jared Mansfield as

its adopted son, and at this

time of Bicentennial celebration be

grateful for the part he played in

translating Revolutionary ideals from

vision into down-to-earth

realities. The medium through which this

translation took place was his

character as a man, a character which in

itself embodied some of the

finest aspects of Revolutionary

idealism.

48. Bond, Civilization of the Old

Northwest, 315, n. 6.

49. Pattison, American Rectangular

Land Survey System, Frontispiece: Map, "Extent

of the American Rectangular Land Survey

System"; John B. Jackson, "The Squaring of

America," The Sacramento Union, October

5, 1975; Vernon Carstensen, "A Long Way

from the Crow to the Stewpot," The

National Observer, October 18, 1975.

CHARLOTTE W. DUDLEY

Jared Mansfield: United

States Surveyor General

Jared Mansfield (1759-1830), one of the

first men of science in the

republic's formative years, made a

significant contribution to post-

Revolutionary Ohio. Appointed by

President Thomas Jefferson in 1803

to replace General Rufus Putnam as

Surveyor General, Mansfield re-

mained in the post for nine years,

resigning in 1812 when fresh Indian

uprisings made further surveys

impractical and dangerous. During his

term of office Mansfield with his wife

and family lived successively at

Marietta (1803-1805), at Ludlow Station

east of Cincinnati (1805-1809),

and at Bates' Place, also near

Cincinnati (1809-1812). From these loca-

tions as headquarters, he ran several of

the meridian and base lines on

which surveys of the public lands

throughout the Northwest Territory

were based. His unique contribution to

the surveys in this early period

was his ability to determine meridian

and base lines accurately by

astronomical observations: in effect, he

adapted principles of celestial

navigation to the determination of

longitude and latitude on land. His

familiarity with navigation was due to

his being the son of a sea captain,

Stephen Mansfield, and to his

mathematical and scientific studies at

Yale College.l

The essential links between the American

Revolution and Mansfield's

work in Ohio were both ideological and

practical. He shared Jefferson's

political philosophy and undoubtedly

believed in the President's vision

of a democratic society.2 If

it may be said that Jefferson was one of the

chief "architects" of a new

nation based in part upon freedom for

ordinary men to own and improve land,

then Jared Mansfield may be

1. Biographical details on Jared

Mansfield may be found in the following sources:

George Cullum, "Jared

Mansfield," Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates

of the United States Military Academy

(New York, 1868), I, 77; Alois F.

Kovarik, "Jared

Mansfield," Dictionary of

American Biography (New York, 1928-1937), XII, 256-57;

Edward D. Mansfield, Personal

Memories, Social, Political and Literary, with Sketches

of Many Noted People, 1803-1843 (Cincinnati, 1879), 1-47 (hereafter cited as E.

Mansfield,

Personal Memories); Horace Mansfield, Descendants of Richard and Gillian Mansfield

Who Settled in New Haven, 1639 (New Haven, 1885), 43-45 (hereafter cited as H.

Mansfield, Mansfield Genealogy); and

Roswell Park, History of West Point (Philadelphia,

1840), 54-55, 59, 68.

2. E. Mansfield, Personal Memories,

5-6.

(614) 297-2300