Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

ROBERT L. DAUGHERTY

Problems in Peacekeeping:

The 1924 Niles Riot

On November 1, 1924, Niles, Ohio was

the scene of one of the

state's most famous riots. Replete with

violence, the riot was

characterized by beatings, overturned

automobiles, and even

shootings. Bands of armed men freely

roamed the streets of Niles,

meeting with little or no opposition

from law enforcement agencies.

Local civil authority in the Niles

area-both municipal and

county-had all but evaporated in the

face of violence, and Ohio's

state government had refused to involve

itself in what it felt to be a

local problem. Thus the forces of law

and order had given way to mob

rule, and the result was that for a

period of time domestic peace and

public safety ceased to exist. As one

contemporary observed, the

situation in Niles was "a damned

serious matter."1

Responsible for the "damned serious

matter" were two

violence-prone groups who had been

waging nearly open warfare for

some time: the Ohio Knights of the Ku

Klux Klan and a second

organization which had formed solely to

oppose the Klan-the

Knights of the Flaming Circle. The Ku

Klux Klan of the early 1920s

was a formidable organization, with

estimates of its national

membership ranging around five million.

In Ohio alone it numbered

approximately 450,000, with the bulk of

its strength centered in

smaller towns and villages.

Traditionally anti-Negro, the Klan had

increased its membership by broadening

its program of intolerance to

include foreigners, Jews, and Catholics.

Added to these warped

appeals was a fondness for secret

rituals, burning crosses, outlandish

costumes, and impressive-sounding

titles. In the unkind words of

Frederick Lewis Allen, "here was a

chance to dress up the village

bigot and let him be a Knight of the

Invisible Empire."2

Dr. Daugherty undertook his graduate

studies at The Ohio State University and has

taught at Temple University, Morris

Harvey College, and Fairmont State College.

1. Ohio, Adjutant General, Transcript

of Evidence Taken by Military Investigation

Board Appointed by General Orders No. 7, November 3-12,

1924, 10. This document

may be found in the archives of the Ohio

Historical Society, Columbus.

2. Frederick Lewis Allen, Only

Yesterday: An Informal History of the

Nineteen-Twenties (New York, 1931), 65. See also John A. Garraty, The

American

Nation Since 1865 (New York, 1966), 290-91. For a brief look at the Ohio

Klan, see

|

Problems in Peacekeeping 281 |

|

|

|

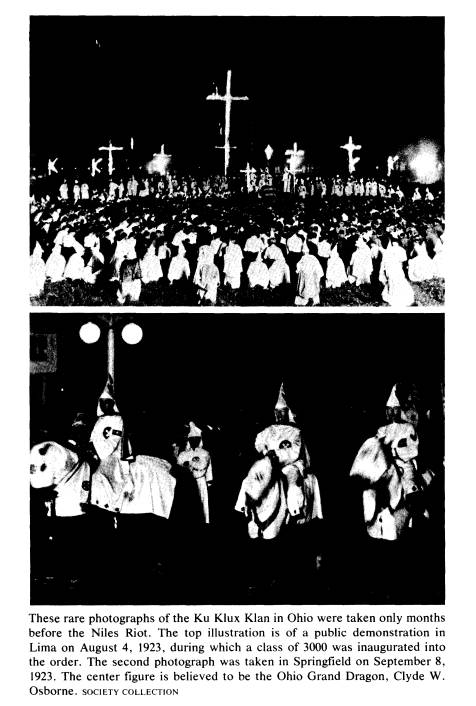

In the Niles area of northeastern Ohio, the Klan was a powerful social and political force. According to newspaper reports, which proved to be accurate, Harvey Kistler, the mayor of Niles, openly courted its political support. In addition, numerous other Niles officials, including the chief of police, were reported to be sympathetic to Klan activities. In nearby Youngstown, whose mayor was openly pro-Klan, municipal law-director Clyde W. Osborne became the Klan's Grand Dragon of the Ohio Realm in September 1924; moreover, Osborne's successor as law-director was a County Cyclops, and the police chief and other town officials as well were Klan members.3 Clearly, the Klan exercised much power, both official and unofficial, in northeastern Ohio in late 1924.

pages 1-2 of John A. Cooley, "Use of the National Guard in the 1924 Ku Klux Klan-Knights of the Flaming Circle Riot in Niles, Ohio," unpublished monograph, 1970, in the possession of Dr. Allan R. Millett, The Ohio State University. 3. Youngstown Telegram, September 8, 13, 1924; Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1924. |

282 OHIO HISTORY

As might be expected, the Klan's

intolerance generated opposition.

In this instance the opposition

centered around an organization of

Italian-American Catholics who called

themselves the Knights of the

Flaming Circle. Holding their first

meeting in Steubenville on

September 27, 1923, the Knights

virtually declared war upon the Ku

Klux Klan when they publicly and

emphatically proclaimed that they

were being organized solely for the

purpose of combatting the Klan.

Ironically, their organizational

meeting bore a marked resemblance to

a typical Klan rally: a huge circle was

burned on a mountain, while

around the circle stood members clad in

white robes on which were

painted red circles encompassing the

figure of the Statue of Liberty.

In one respect the ritual did differ

from those of the Klan: the robes

were hoodless. In any event, there was

no mistaking that the Knights

intended to take vigorous measures to

halt the Klan's activities.4

Open conflict between the two groups

broke out in the summer of

1924, with Niles as the focal point. In

June the Klan was forced to

postpone a parade at Niles after a

two-hour clash with the Knights. A

truce was arranged, the two groups

agreeing to forego such

provocative practices as burning

crosses or circles. The truce was

short-lived, however, as disturbances

broke out again in August,

including the burning of a cross in

front of a Catholic church and the

beating of an unfortunate man whose

only crime was his refusal to

join either side.5

Against this background of mounting

disorder, Mayor Harvey

Kistler compounded an already

inflammatory situation by introducing

his own one-sided version of how peace

should be restored. First of

all, in what appeared to be an

impartial effort to maintain order, he

issued a proclamation prohibiting the

burning of either crosses or

circles. To enforce the terms of the

proclamation, however, he

appointed a number of Klansmen as

"special policemen," a move

that in no way could be construed as

neutral.6 If Kistler thought that

his appointments would intimidate the

Knights of the Flaming Circle,

he was mistaken. The Knights, it

appears, grew even more

determined in their opposition to the

Klan. Furthermore, the Knights

now considered Kistler a member of the

enemy camp and would treat

him as such.

4. Columbus Ohio State Journal, September

27, 1923; Cooley, "Use of the National

Guard in Niles," 2-3.

5. Columbus Ohio State Journal, August

6, 12, 1924; Cooley, "Use of the National

Guard in Niles," 6.

6. Columbus Ohio State Journal, November

2, 13, 1924; Cleveland Plain Dealer,

November 3, 1924.

Problems in Peacekeeping 283

Niles remained a powder keg. The Klan

persisted in publicly

advertising that a parade would be held

in Niles, while opposition

groups headed by the Knights just as

stoutly proclaimed that such a

parade would not be allowed. The

situation was ripe for violence.7

In late October 1924, Mayor Kistler

provided the final spark which

set off the Niles riot when he granted

the Klan a permit to hold a rally

on a field just outside Niles, and to

parade through the city itself on

November 1. Accepting Kistler's act as a

challenge, various

Italian-American groups led by the

Knights immediately responded

by requesting a permit of their own to stage

a counter-demonstration

and parade in Niles on the same day as

the Klan rally. Kistler,

reflecting his pro-Klan biases as well

as perhaps some common sense,

refused the request; but the Knights,

not deterred, announced that

they would nevertheless stage their

demonstration.8 Mayor Kistler

justifiably interpreted the Knights'

announcement as a hostile act,

labeling it an "open declaration of

war." Any lingering doubts about

their hostility were dispelled in the

early morning hours of October

29, when an attempt was made to bomb his

home. Although those

responsible for the bombing were never

discovered, under the

circumstances it seems probable that

either the Knights or their allies

were guilty. Kistler obviously felt that

this was the case, for he spent

the next two nights in Warren at the

home of Dr. B. A. Hart,

Trumbull County Cyclops of the Klan.9

In the meantime, on October 27 and

amidst rumors that as many as

ten thousand Knights and twenty-five

thousand Klansmen were about

to gather in Niles, Mayor Kistler had

conferred with Trumbull County

Sheriff John E. Thomas about how the

impending clash might be

averted. They agreed that outside police

help was needed. Answering

their request for aid, Youngstown

officials quickly promised to send

police, at the same time suggesting to

Kistler that he seek help from

Canton, Akron, and Cleveland.10 Within

two days, however, Kistler

decided that local police, in whatever

numbers, would not be able to

prevent a riot. No doubt influenced by

the attempted bombing of his

home, he announced on October 29 that he

would ask Governor A.

Victor Donahey to send national guard

troops. The request was made

on the following day. Thus, unwilling to

prohibit the parade by the

Klan, and unable to prevent a

counter-demonstration by the Knights,

7. Columbus Ohio State Journal, August

10, 1924.

8. Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1924. Indicating the tension of the

situation,

the Knights publicly urged that

"women and children [should] stay at home."

9. Columbus Ohio State Journal, October

30, November 2, 3, 1924.

10. Youngstown Telegram, October

27, 1924; Cooley, "Use of the National Guard in

Niles," 6-7.

284 OHIO HISTORY

Kistler attempted to pass on to the

state the burden of maintaining

peace in Niles.11

There was a recurring theme in the

history of Ohio's state-local

relations during the strife-ridden

1920s and 1930s: when faced with

the necessity of preserving law and

order, local officials would often

look to the state for help rather than

risk alienating members of their

own community by maintaining order with

local forces. In fact, the

local officials' desire for state

forces to halt disorders often seemed to

increase in direct proportion to the

voting strength of the local

disturbers of the peace. The state,

however, was not blind to the

possible political repercussions

connected with sending armed state

forces into Ohio communities. After

all, governors were no more

eager than local elected officials to

antagonize voters. Calls for the

national guard, consequently, were

seldom answered until the

governor was completely satisfied that

local law enforcement

agencies had made a sincere effort to

end the disturbances

themselves. The result was a tug-of-war

over law-enforcement

responsibility between local and state

authorities, with both levels of

government wanting the law maintained,

but each expecting the other

to supply the force.12

Governor Donahey wanted no part of what

he felt to be a local

problem, and Kistler knew it. On

October 27, or two days before

announcing that he would ask for the

national guard, Kistler had

contacted Donahey concerning the

possibility of state aid. Donahey's

reply could not have been more

negative: he flatly informed Kistler

that city and county authorities were

expected to handle any possible

emergency in Niles. Furthermore, on the

evening of October 30,

approximately two hours after receiving

Kistler's official request for

troops, Donahey wired to the mayor an

even more forceful reply,

telling him, "I stand on my letter

to you under date of Oct. 27, and

will hold you to strict

accountability."13 Donahey's position, then,

was clear. As it stood, the Niles

situation was a local problem, and

Kistler and other local officials on

the scene were expected to cope

with it.

While the governor and mayor were

exchanging messages,

Trumbull County Sheriff John Thomas was

busy attempting to do

exactly what Donahey expected of him:

recruit extra deputies to

11. Canton Evening Repository, October

27, 1924; Youngstown Telegram, October

30, 1924; Columbus Ohio State Journal,

October 31, 1924.

12. For examples of local-state

frictions, see Robert L. Daugherty, "Citizen Soldiers

in Peace: The Ohio National Guard,

1919-1940" (Ph.D. dissertation, The Ohio State

University, 1974), 88, 283, 284.

13. Columbus Ohio State Journal and

Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 31, 1924.

|

Problems in Peacekeeping 285 |

|

|

|

enforce the peace in Niles. In contrast to Niles Police Chief L. J. Rounds, who, like Mayor Kistler, had already decided that local forces could not cope with a serious outbreak, Thomas was at first optimistic. On October 30, two days before the demonstration, he stated that he expected to have enough deputies "to handle any situation." Shortly afterward, however, and after conferring with other local officials and representatives of the governor, presumably national guard officers in plainclothes, he completely reversed himself by wiring Donahey for help, saying that the situation was "impossi- ble."14 Sheriff Thomas apparently had learned a basic lesson in re- cruiting: enlisting deputies to enforce speed laws was one thing, but finding men willing to be caught in the squeeze of Klan-Knights vio- lence was another. Upon receiving the sheriff's telegram, Donahey immediately conferred with the Ohio National Guard's Adjutant General, Frank D.

14. Akron Beacon Journal, October 31, 1924; Columbus Ohio State Journal, November 1, 1924. |

286 OHIO HISTORY

Henderson. After being assured by

Henderson that troops, should

they really be needed, could be quickly

transported to Niles,

Donahey wired a refusal to Sheriff

Thomas, telling him that he and

Mayor Kistler were responsible for

controlling the situation:

Both you and the mayor have had ample

warning and ample time to prepare

for any possible emergency. If riot,

tumult or disorder develops, every

agency of the state government will be

used to quell the same immediately

and restore order. In any event, I will

hold you and mayor strictly

accountable.15

Donahey had again stated his position

clearly. The Klan-Knights

controversy was a local problem, and

thus state forces would be

committed only as a last resort.

On October 31, with a riot all but

scheduled for the following day in

Niles, confusion reigned. In Niles

Sheriff Thomas frantically sought

to deputize men willing to do possible

combat with two

violence-prone extremist groups, while

at the same time eight

hundred prominent Niles citizens

attempted in vain to persuade

Mayor Kistler to revoke the Klan's

parade permit. Viewing the

chaos, Colonel Ludwig S. Conelly and

other national guard officers,

who had been in Niles since the night of

the attempted bombing of

Kistler's home, reported that the

situation was "menacing."

Meanwhile, in Columbus, Governor Donahey

remained convined that

Niles authorities could and would cope

with any possible trouble. His

view was seconded by Adjutant General

Henderson, who publicly

announced that no national guardsmen

were being readied for

emergency duty in Niles.16 Against

this backdrop, a riot broke out in

Niles early the next day.

Saturday morning, November 1, 1924, was

not a pleasant

experience for Ohio Klansmen. Determined

to prevent their parade,

the Knights of the Flaming Circle set up

roadblocks on the major

streets. All approaching automobiles

were stopped and searched by

armed Knights, who unceremoniously

removed any Klan costumes or

guns. In some cases the passengers were

beaten, while in others the

autos were overturned. Sporadic shooting

broke out, for both

Klansmen and Knights were armed; before

the day concluded, at

least thirteen people were wounded.

Niles had become a battle-

ground. 17

15. Columbus Ohio State Journal and

Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 1, 1924.

16. Columbus Dispatch, October

31, 1924; Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 1,

1924.

17. See Ohio, Adjutant General, Transcript

of Evidence.

|

Problems in Peackekeeping 287 |

|

|

|

As reports of shootings and even killings (there were no killings) reached Columbus, an alarmed Governor Donahey found himself forced to reconsider the use of state forces. Prodding him was a telephone call from Colonel Conelly, on the scene in Niles, informing him that the national guard should be sent quickly. Still reluctant however, to commit the guard unless absolutely necessary, Donahey conferred at length with Adjutant General Henderson. At 1:15 p.m., or roughly two hours after Conelly's call, the decision was made-the national guard would be sent to Niles immediately. After ordering Henderson to dispatch the guard units, Donahey issued a proclama- tion declaring that Niles was in a "state of riot" and was being placed under qualified martial law.18 Once having decided to commit the state's military forces, "the modern governor's ultimate dependence for law and order,"19

18. Columbus Ohio State Journal, Canton Evening Repository, and Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 2, 1924; James K. Mercer, Ohio Legislative History, 1923-1924 (Columbus, 1924), V, 156-57. Niles became the first Ohio city to be placed under "qualified" martial law since the Civil War. 19. Philip Taft and Philip Ross, "American Labor Violence: Its Causes, Character, and Outcome," in Hugh Davis Graham and Ted Robert Gurr, eds., The History of Violence in America (New York, 1964). 282. |

Problems in Peacekeeping 289

Donahey followed sound riot-control

practice by sending enough

troops to guarantee that order would be

restored. Some thirteen

hundred men from northeastern Ohio went

to Niles.20

In Niles Colonel Conelly assumed

temporary command of the

troops, pending the arrival of General

Benson W. Hough in whose

hands Governor Donahey had left the

entire situation. Conelly, upon

receiving Donahey's proclamation,

immediately took over the "police

authority." Unlike strict martial

law, qualified martial law did not

supercede civil law in the area.

Instead, military orders had to

conform to civil law, and persons

arrested had to be turned over to

civilian authorities. Civil courts

continued functioning, and it was

clearly understood that law enforcement

would revert to local

officials as soon as possible.21

Conelly wasted no time in restoring

order in Niles. Utilizing the

powers granted him by Donahey, he

publicly declared that no more

than three people were to congregate at

any one time, and that all

people were to be off the streets by

6:00 p.m. All pool rooms, movie

theaters, restaurants, and other

gathering places were closed. In

addition, a national guard intelligence

section was established to

gather evidence concerning who was

responsible for the riot.22

Shortly after Conelly's action, the

first contingent of national guard

units reached Niles; the rest of the

guardsmen arrived sporadically

throughout the day. The appearance of

the first troops, coupled with

Conelly's prohibition of the forming of

crowds, abruptly ended the

Niles riot. Conelly's declaration

cancelled the Klan's parade permit

simply by banning crowds. To enforce

Conelly's directives; and to

guarantee that order would be restored,

national guard vehicles

conspicuously sported mounted machine

guns, while guardsmen on

foot marched through Niles with bayonets

fixed. Word was sent to

the Klan that there would be no parade,

and troops were stationed at

20. Akron Beacon Journal, November

1, 1924; Columbus Ohio State Journal,

November 2, 1924. The National Guard

units included the 145th Infantry companies

from Cleveland, Canton, Akron,

Youngstown, Warren, and Berea; four batteries of the

135th Field Artillery, three from Canton

and one from Youngstown; the 112th

Engineers battalion from Cleveland; and

two troops of cavalry, one from Akron and the

other from Barberton.

21. Columbus Ohio State Journal, November

2, 1924; Canton Evening Repository,

November 2, 3, 1924; and Cleveland

Plain Dealer, November 2, 1924. For terms of

qualified martial law, see Ohio,

Adjutant General, Regulations for the Ohio National

Guard, 1905,

9; and Ibid., 1913, 12-22, 297-300, 322. See also Howard Foster, "A

History of the Ohio Executive,

1923-1929" (M.A. thesis, The Ohio State University,

1934), 82-83 for the effect of Donahey's

declaration.

22. Columbus Ohio State Journal, November

2, 1924; Canton Evening Repository,

November 21, 1924; Cleveland Plain

Dealer, November 2, 1924.

290 OHIO HISTORY

the Klan encampment to disperse those

who had already gathered for

the parade. Finally, guardsmen

prevented a trainload of Klansmen

from Kent and other places from

entering Niles. As Klansmen

scattered, so did the Knights of the

Flaming Circle; with the parade

cancelled, the Knights no longer had

any reason to be in Niles. By the

end of the day a real disaster had been

averted. General Hough, after

taking over Colonel Conelly's temporary

command, kept the troops in

Niles for several more days although

there was no further trouble

worthy of note. Peace having been

restored, Governor Donahey

ended qualified martial law an November

5.23

The national guard's performance at

Niles merits further comment.

The troops were capably led, first by

Colonel Conelly and then by

General Hough. Conelly's performance

was especially meritorious.

Serving first as a "scout in

civilian clothing" before the riot, he was

Governor Donahey and Adjutant General

Henderson's most reliable

source of information. Then, when

placed in command of the

guardsmen at Niles, he acted decisively

and professionally. Following

generally accepted rules for dealing

with rioters, he neither

temporized nor sided with either the

Klan or the Knights. His job was

to "absolutely prevent all

disorder, no matter from what source," a

duty which he performed in a forceful,

no-nonsense manner.24

General Hough's performance also was

commendable. By late

November 1, when he assumed Conelly's

temporary command, the

riot was over. The possibility of a

recurrence existed, however, in the

form of a Klan declaration that another

parade was scheduled for

Niles in the near future. Moreover,

Mayor Kistler, ever sympathetic

to Klan interests, announced that he

"would grant Klansmen a permit

to parade anytime they asked for

it." Hough quickly squelched the

idea, bluntly stating that there would

be no parades or demonstrations

of any type as long as the national

guard was on duty. The Klan did

not parade.25

Not everyone appreciated the national

guard's handling of the riot.

Ku Klux Klan officials, led by Ohio

Grand Dragon Clyde W.

Osborne, felt that the guard had been

anything but neutral in

23. Mercer, Ohio Legislative History,

V, 156-57; Columbus Ohio State Journal,

November 2, 1924. See also pages 17-19

of Frank L. Howe, "Fiery Crosses, Flaming

Circles, and Citizen Soldiers," unpublished

monograph, 1971, in the possession of Dr.

Allan R. Millett, Ohio State University.

24. See U. S., Department of War, War

Plans Division, "The Use of Organized

Bodies in the Protection and Defense of

Property During Riots, Strikes, and Civil

Disturbances," Military

Protection: United States Guards, War Department Document

No. 882 (Washington, D.C., 1919), 14,

17, 73 for Conelly's adherence to generally ac-

cepted guidelines for dealing with

riots.

25. Akron Beacon Journal, November

3, 1924.

Problems in Peacekeeping 291

cancelling their parade. Miffed, Osborne

absolved the Klan of any

blame for the disturbances. The true

troublemakers, he asserted,

were outsiders "largely of foreign

birth." He went on to say that

"this outrage rests with the

confessed enemies of the republic, with

the hidden forces of Societism and

anarchy, which acknowledge no

God and look with equal contempt upon

the religious faith of Jew,

Catholic and Protestant."26 That

Osborne and the Klan were so

concerned about the religious faiths of

Jews and Catholics must have

evoked some amazement, especially among

those Italian-American

Catholics who largely comprised the

Knights of the Flaming Circle.

The national guard had a final role to

play at Niles. Angry at being

forced to call out the guard, Governor

Donahey established a Military

Investigation Board to discover who was

responsible for the riot.

Donahey, still convinced that local

authorities had not been

sufficiently energetic in attempting to

prevent violence, implied in a

November 2 letter to General Hough that

the heads of local officials

would roll:

Civil authorities had ample warning and

time to prepare for the threatened

danger. They failed. The reason for this

breakdown of civil control must be

ascertained and official derelection, if

any, punished, as well as justice meted

out to the criminal assailants against

law and orderly society.27

Amid rumors that local officials would

be held to "strict

accountability," General Hough

ordered Mayor Kistler, Sheriff

Thomas, and Trumbull County Prosecutor

Harvey Burgess to his

headquarters at Niles for a conference.

Hough, reflecting Donahey's

disgust with the recent behavior of

local law authorities, asked: "Will

you make any real attempt to discover

and prosecute the persons who

were responsible for the riot?" The

three assured him they would.

Mayor Kistler, not short on audacity,

added, "I have done my whole

duty and invite investigation." The

Military Investigation Board was

established the following day, with the

understanding that a special

grand jury headed by County Prosecutor

Burgess would act on the

Board's findings.28

The military board consisted of

Lieutenant Colonel Wade C.

Christy who presided, two other guard

officers, and one enlisted

26. Columbus Ohio State Journal, November

2, 1924.

27. Ibid., November 3, 1924.

28. Howe, "Fiery Crosses,"

19-20; Columbus Ohio State Journal, November 2, 3,

1924.

292 OHIO HISTORY

man; it met for ten days, and heard over

125 witnesses.29 It

accomplished nothing other than

discovering that those witnesses

summoned suffered terrible lapses of

memory. Although their

testimonies abounded with accounts of

the events leading up to the

riot, witnesses proved almost totally

incapable of making any

identifications more specific than that

certain perpetrators of violence

were "foreigners" or

"Italians." Apparently, citizens of the 1920s

were just as reluctant to become

"involved" as those of a later

date.30

Strangely, those who might have

contributed crucial testimony

were never called to testify by the

military board. For reasons yet not

clear, Colonel Conelly and other guard

officers who were in Niles

before the riot were never questioned.

Nor were Mayor Kistler,

Police Chief Rounds, Sheriff Thomas, and

prominent Klan and

Flaming Circle leaders.31 The

absence of such key witnesses suggests

that once the riot had been successfully

dealt with, and once tempers

had cooled, Ohio officials-notably

Governor Donahey-quickly lost

interest in attempting to fix blame for

its outbreak. Governor

Donahey's earlier threats

notwithstanding, there was little profit in

prolonging state-local frictions.

Moreover, fixing responsibility for the

riot might have proved impossible in any

event, given the chaotic

conditions that characterized those days

leading up to the final

eruption of November 1. Most riots begin

under such confusing

circumstances that holding anyone

legally responsible for them is

nearly impossible. The Niles riot of

1924 was probably no exception.

29. The primary source for the

investigation is Ohio, Adjutant General, Transcript of

Evidence. The investigation's progress was cited in various

newspapers, such as the

Columbus Ohio State Journal, November

4, 5, 1924, and Youngstown Telegram,

November 14, December 9, 1924. See also

Howe, "Fiery Crosses," 20.

30. See Ohio, Adjutant General, Transcript

of Evidence; and Howe, "Fiery

Crosses," 24.

31. The Columbus Ohio State Journal, November

2, 1924, reported that Sheriff

Thomas had observed Mayor Kistler

swearing in Klan members as "special police-

men," yet the military board

questioned neither Kistler nor Thomas.

ROBERT L. DAUGHERTY

Problems in Peacekeeping:

The 1924 Niles Riot

On November 1, 1924, Niles, Ohio was

the scene of one of the

state's most famous riots. Replete with

violence, the riot was

characterized by beatings, overturned

automobiles, and even

shootings. Bands of armed men freely

roamed the streets of Niles,

meeting with little or no opposition

from law enforcement agencies.

Local civil authority in the Niles

area-both municipal and

county-had all but evaporated in the

face of violence, and Ohio's

state government had refused to involve

itself in what it felt to be a

local problem. Thus the forces of law

and order had given way to mob

rule, and the result was that for a

period of time domestic peace and

public safety ceased to exist. As one

contemporary observed, the

situation in Niles was "a damned

serious matter."1

Responsible for the "damned serious

matter" were two

violence-prone groups who had been

waging nearly open warfare for

some time: the Ohio Knights of the Ku

Klux Klan and a second

organization which had formed solely to

oppose the Klan-the

Knights of the Flaming Circle. The Ku

Klux Klan of the early 1920s

was a formidable organization, with

estimates of its national

membership ranging around five million.

In Ohio alone it numbered

approximately 450,000, with the bulk of

its strength centered in

smaller towns and villages.

Traditionally anti-Negro, the Klan had

increased its membership by broadening

its program of intolerance to

include foreigners, Jews, and Catholics.

Added to these warped

appeals was a fondness for secret

rituals, burning crosses, outlandish

costumes, and impressive-sounding

titles. In the unkind words of

Frederick Lewis Allen, "here was a

chance to dress up the village

bigot and let him be a Knight of the

Invisible Empire."2

Dr. Daugherty undertook his graduate

studies at The Ohio State University and has

taught at Temple University, Morris

Harvey College, and Fairmont State College.

1. Ohio, Adjutant General, Transcript

of Evidence Taken by Military Investigation

Board Appointed by General Orders No. 7, November 3-12,

1924, 10. This document

may be found in the archives of the Ohio

Historical Society, Columbus.

2. Frederick Lewis Allen, Only

Yesterday: An Informal History of the

Nineteen-Twenties (New York, 1931), 65. See also John A. Garraty, The

American

Nation Since 1865 (New York, 1966), 290-91. For a brief look at the Ohio

Klan, see

(614) 297-2300