Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

ERIC J. CARDINAL

The Ohio Democracy and the

Crisis of Disunion, 1860-1861

One of the least understood political

groups in American history

has been the northern Democratic party

during the Civil War. Their

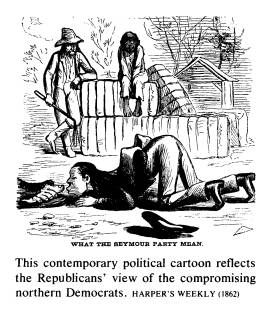

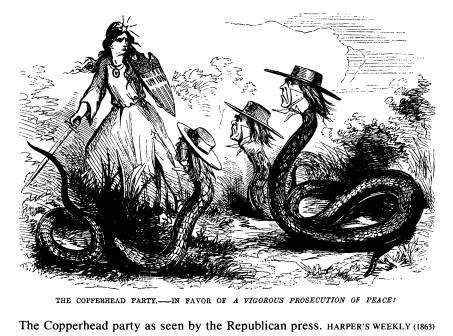

contemporary Republican foes vilified

them as traitors, and

subsequent historians have for the most

part agreed with that

verdict.1 Political

partisanship, ideological conflicts, and wartime

passions account for the original

animus; it is less clear why scholars

have tended to follow so closely the

Republican lead. The primary

reason for the continuing bad

reputation of the wartime Democrats is

that they, nearly as much as the

confederates themselves, "lost" the

war and thus the legitimacy of their

position. The war destroyed their

hopes for the preservation of "the

Union as it was and the

Mr. Cardinal is a Teaching Fellow at

Kent State University where he is in the final

stages of work on his dissertation, a

project being advised by Professor Frank L.

Byrne.

1. See for example Curtis H. Morrow, Politico-Military

Secret Societies of the

Northwest, 1860-1865 (Worcester, MA, 1929); Leonard Kenworthy, The Tall

Sycamore of the Wabash: Daniel Wolsey

Voorhees (Boston, 1936); Wood Gray,

The Hidden Civil War: The Story of

the Copperheads (New York, 1942);

George F.

Milton, Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth

Column (New York, 1942); Christopher

Dell, Lincoln and the War Democrats:

The Grand Erosion of Conservative

Tradition (Cranbury, NJ, 1975); F. L. Grayson, "Lambdin P.

Milligan-A Knight of

the Golden Circle," Indiana

Magazine of History, XL (1947), 379-91; Frank C.

Arena, "Southern Sympathizers in

Iowa During the Civil War Period," Annals of Iowa,

XXX (1951), 486-538; Bethania M. Smith,

"Civil War Subversives," Journal of

the Illinois State Historical

Society, XLV (1952), 220-40; Robert S.

Harper, "The

Ohio Press in the Civil War," Civil

War History, III (1957), 221-52, which are studies

embracing, in whole or in part, this

general conception. This is not an exhaustive list,

nor does it fully indicate the

pervasiveness of this view of the northern Democracy. For

example, Norman A. Graebner et al., A

History of the American People (New York,

1975), 423; and Keith I. Polakoff et

al., Generations of Americans: A History of the

United States (New

York, 1976), 366 are two recently-published texts that reflect this

view.

For lucid critiques of the interpretive

literature concerning the northern Democrats,

see Richard O. Curry, "The Union as

it Was: A Critique of Recent Interpretations of

the 'Copperheads,' " Civil War

History, XIII (1967), 25-39; and Robert H. Abzug,

"The Copperheads: Historical

Approaches to Civil War Dissent in the Midwest,"

Indiana Magazine of History, LXVI (1970), 40-55. For balanced views of the

"Copperheads" which tend to

revise the traditional picture see Frank L. Klement, The

Copperheads of the Middle West (Chicago, 1960); and Idem, The Limits of

Dissent: Clement L. Vallandigham and the Civil War (Lexington, 1970), in addition

20 OHIO HISTORY

Constitution as it is" just as

surely as it did southern independence.

While historians have long noted, and

for the most part hailed, the

modernizing tendencies of the war,2

Democratic aspirations always

required an American Union that was

politically static. Essentially

Jeffersonian in outlook, they harkened

back to a lost past, to a

decentralized, agrarian, pre-industrial

America. As Clement L.

Vallandigham, the most notorious of the

"Peace Democrats," put it

in the early days of the war, the role

of the Democratic party was to

save the country from destruction,

"to restore the Union, the

Federal Union as it was forty years

ago."3 The dilemma of the

Democrats was that the Civil War

intensified processes already at

work transforming the Federal Union they

cherished into the

centralized nation they feared.

Similarly, the apotheosis of Abraham

Lincoln has helped further to

discredit the Democrats. The

"Lincoln theme"-stressing the

development of Lincoln as chief

executive, as war leader, as

emancipator, as humanitarian-has been a

compelling one for

historians. The number of historical

works whose titles begin with the

words "Lincoln and . .

." attests to this. Lincoln's wartime political

opponents have suffered by contrast.

Further, the racism inherent in the

Democratic ideology has made it

morally unattractive to modern scholars.

The Democratic view of a

static American political order

necessarily entailed, whether explicitly

or implicitly, a defense of slavery.

Even those Democrats who were

opposed to the institution were willing

to perpetuate it in order to

avert, and later to end, civil war.

Americans of the latter twentieth

century must consider the implications

of such views and recognize

that the Democrats themselves did not.

Yet they were, after all, men

to his numerous articles; Van M. Davis,

"Individualism on Trial: The Ideology of the

Northern Democracy During the Civil War

and Reconstruction" (Ph.D. Dissertation,

University of Virginia, 1972); James A.

Rawley, The Politics of Union: Northern

Politics During the Civil War (Hinsdale, IL, 1974); and Leonard P. Curry,

"Congressiona

Democrats, 1861-1863," Civil War

History, XII (1966), 213-29.

2. See for example Woodrow Wilson's

classic celebration of the nationalizing effects

of the war in Division and Reunion,

1829-1889 (New York, 1893), especially 273-75

298-99. For more recent expressions see

William B. Hesseltine, Lincoln and the Wa

Governors (New York, 1948); and Idem, Lincoln's Plan for

Reconstruction (Chicago

1960); Allan Nevins, The Warfor the

Union: The Organized War, 1863-1864 (New York

1971); and Idem, From Organized War

to Victory, 1864-1865 (New York, 1971); Harold M

Hyman, A More Perfect Union: The

Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on the

Constitution (New York, 1973); and Rawley, The Politics of Union.

For an analysis of thi

view in American historiography of the

Civil War period, see Thomas J. Pressly, Amer

cans Interpret Their Civil War (Princeton, 1962).

3. Clement L. Vallandigham to Alexander

S. Boys, August 13, 1861, The Papers o

Alexander S. Boys, Ohio Historical

Society.

Ohio Democracy 21

of their times, and racism was not

confined to the ranks of the

Democracy in the mid-nineteenth century.4

Certainly at a time when

Lincoln himself treated blacks as

"only his stepchildren,"5 the

Democrats were not outside the American

mainstream with their

white supremacist beliefs.

A first step in considering the wartime

Democrats more

dispassionately is a careful examination

of their course during the

secession crisis and the opening months

of hostilities. The factors that

have tended to discredit the wartime

Democrats have also obscured a

little appreciated fact: as the

shattering events which accompanied the

election of Lincoln pushed the United

States over the precipice of

sectional bitterness into civil war, the

northern Democracy-more

than any other political group-stood

unwaveringly for the

preservation of the Union.6 Southern

leaders generally advocated

secession and Republicans faced the

crisis initially with seeming

ambivalence-some counseled peaceful

dissolution, others armed

coercion, and still others separation

and coercion in almost the same

breath. Northern Democrats, however,

stressed one

theme-resolution of the crisis through

an equitable compromise.

They recognized neither the right of

secession nor that of coercion, and

this remained the heart of their problem

throughout the war.

Moreover, northern Democrats first

articulated positions concerning

secession and civil war during this

early period which, with few

modifications, they maintained

throughout the conflict.

Since the national political parties in

the mid-nineteenth century

4. See Leon F. Litwack, North of

Slavery (Chicago, 191); Eugene H. Berwanger,

The Frontier Against Slavery: Western

AntiNegro Prejudice and the Slavery

Extension Controversy (Urbana, 1967); Jacque Voegeli, "The Northwest and

the

Race Issue, 1861-1862," Mississippi

Valley Historical Review, L (1963), 235-51; and

Eric Foner, "Politics and

Prejudice: The Free Soil Party and the Negro, 1849-1852,"

Journal of Negro History, L (1965), 235-56.

5. Don E. Fehrenbacher, "Only His

Stepchildren: Lincoln and the Negro," Civil

War History, XX (1974), 293-310.

6. The Constitutional Union men,

supporters of John Bell and Edward Everett, were

also undeniably for the preservation of

the Union by compromise. But their strength as

a party after the defeat of 1860 was

negligible and they increasingly identified their

course with the northern Democrats.

Democrats clearly took the lead in advocating

compromise measures, even those

originally proposed by non-Democrats such as

Kentucky Senator John J. Crittenden. In

so doing, Democrats hoped to induce the

Constitutional Unionists Americans,

old-line Whigs, and all other conservative men to

act with them under the Democratic

banner. It was clear to Republican observers that

the Democracy was to be the

institutional rallying point of all such conservatives. See

Simeon Nash to John Sherman, December 3,

1860; F. D. Parish to Sherman, February

2, 1861, The Papers of John Sherman,

Library of Congress. In addition, see Portsmouth

The Union and the Times, November 1860-April 1861, passim.

22 OHIO

HISTORY

were the respective state parties in the

aggregate, it is useful to

examine the political events during this

period at the state level.

Because of its leadership position

within the Old Northwest and its

later notoriety as a

"Copperhead" stronghold, Ohio may be used as a

case in point.7 The

presidential campaign of 1860 had proven to be a

divisive one for the Ohio Democracy,

even as it had for the party

nationally. The great majority of

Democrats in the Northwest

supported the candidacy of the Little

Giant of Illinois, Stephen A.

Douglas. Indeed, "the feeling in

his favor in the West is un-

mistakable," wrote Vallandigham.

"It amounts to a popular furor ...."8

Despite this broad base of popular

support, a number of

prominent Ohio Democrats, who had broken

with Douglas when he

split with the Buchanan Administration

over the Lecompton issue in

1858, threw their support in 1860 to the

candidacy of John C.

Breckinridge. Though Breckinridge

support remained negligible

among the mass of Ohio Democrats, the

divisive campaign shattered

the unity of the party.9 Thus,

with the election of Lincoln and the

march of the southern states out of the

Union, Ohio Democratic

leaders sought not only a solution to

the national crisis but also to

heal their own intra-party wounds and

insure political survival.10 The

recent rift within the party

particularly worried them. "If the

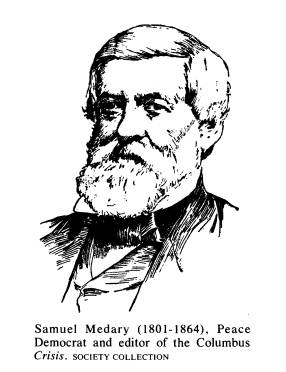

7. Ohio was the home base of many of the

most noted "Copperheads" during the

Civil War: Archibald MacGregor, Samuel

Medary, Edson B. Olds, William Allen,

Allen G. Thurman, Alexander Long, George

Pendleton, and Clement L. Vallandigham.

The Ohio gubernatorial campaign of 1863

pitted the exiled Vallandigham against Union

party nominee John Brough; for an

analyis of this critical election see Eugene

Roseboom, "Southern Ohio and the

Union in 1863," Mississippi Valley Historical

Review, XXXIX (1952), 29-44.

8. Vallandigham to Alexander H.

Stephens, June 4, 1860, Vallandigham File,

Western Reserve Historical Society,

photocopy, original is in The Papers of Alexander

H. Stephens, Emory University.

9. See Roy F. Nichols, The Disruption

of American Democracy (New York,

1948), 213-14, for the background for

this split in Ohio. At the height of the 1860

canvass, Archibald MacGregor of Canton

estimated that only eight Democratic journals

in Ohio supported Breckinridge. In

addition to his own Canton Stark County

Democrat, MacGregor cited the Cleveland National Democrat, the

Cadiz Sentinel,

the Carrolton Democrat, the Warren

Democrat, the St. Clairsville Gazette, the

Steubenville Union, and the Newark Advocate. Canton Stark County

Democrat,

July 24, 1860. In contrast, the Columbus

Ohio State Journal estimated that 80 papers

in the state supported Douglas; Columbus

Ohio State Journal, July 23, 1860. At the

election itself, Breckinridge ran fourth

in the state, receiving 11,403 votes, compared to

231,809 for Lincoln, 192,421 for

Douglas, and 12,194 for Bell. Joseph P. Smith, History

of the Republican Party in Ohio (Chicago, 1898), I, 128-29.

10. For a discussion of these

developments throughout the North see John T.

Hubbell, "Politics as Usual: The

Northern Democracy and Party Survival, 1860-1861,"

Illinois Quarterly, XXXVI (1973), 22-35. For a slightly different view, see

Robert W.

Johannsen, "The Douglas Democracy

and the Crisis of Disunion," Civil WarHistory,

IX (1963), 229-47.

Ohio Democracy

23

Democratic party were united as in

former days my hopes for a

settlement of all the troubles would be

anchored within the Vail," wrote

state Representative William Parr.

"But as we are divided I fear

trouble. "11 With remarkable

unanimity, however, Ohio Democratic

spokesmen sought to solve the crisis by

conciliation while

demonstrating themselves to be the true

Union men. Thus they created a

common ground upon which most Ohio

Democrats could stand.

The key to the Democratic response was

compromise, which they

saw as the only means by which to

preserve the Federal Union as it

was then constituted. "All

[Democrats] seem willing to risk an[d]

sacrifise [sic] everything for the Union," wrote state

Representative

George Converse early in the crisis.

Democrats believed that either

unchecked secession or a coercive civil

war to prevent dissolution

ultimately would spell the permanent

destruction of the Union. Only

in a compromise settlement that

reasonable men of all sections could

approve did they see hope for the

country's salvation. Accordingly,

the Democratic press of the state

immediately began to call for

compromise measures as soon as it became

evident that secession

and disunion were not merely idle

southern threats. As one Franklin

County Democrat explained, "the

Democrats are all in favor of an

honorable conciliation of the trouble,

so as to preserve the Union,

allowing the South all her

Constitutional rights, and withholding

nothing from the North that legitimately

belongs to her by virtue of the

Constitution." William B. Woods, a

state Representative, confirmed

that this was the dominant impulse among

his colleagues: "There is a

universal sentiment among the Democrats

here in favor of any

measures which will bring peace to the

country and save the

confederacy."12

At the same time, Democrats disavowed

any responsibility for the

crisis. Southerners were rebelling

specifically at the election of a

Republican President. All Democrats

could, therefore, rightly say of

the difficulties, "This is not my

work!", as party leader Allen G.

Thurman emphasized at a party convention

in January 1861.

11. William Parr to Samuel S. Cox,

January 10, 1861, The Papers of Samuel S. Cox,

Brown University Library.

12. George Converse to Samuel S. Cox,

January 2, 1861, Ibid.; John Bobo to Cox,

January 14, 1861, Ibid.; William B. Woods to

Cox, January 12, 1861, Ibid. See also

Cincinnati Enquirer, December 8, 9, 11, 1860, January 9, 1861; Cleveland

Plain

Dealer, December 20, 1860, January 2, 1861; Columbus Ohio

Statesman, December 20,

21, 29, 1860, January 2, 3, 1861; Canton

Stark County Democrat, November 21, 1860;

Celina Western Standard, January

10, 1861; Georgetown Southern Ohio Argus,

December 5, 1860, January 9, 1861; Newark

Advocate,January 4, 18, 25,1861; Ravenna

Portage Sentinel, December 19, 1860; Wooster Wayne County Democrat, December

13,

January 3, 17, 1861, for early editorial

expressions favoring compromise measures.

24 OHIO HISTORY

Democrats not only denied their own

culpability, they quickly placed

blame squarely upon other shoulders. As

a correspondent of state

Representative James Gamble put it:

"A momentous question is now

to be decided by the conservative men of

the Union, and that

is:-Shall their liberties be frittered

away by a corrupt faction in the

North and another in the South?"

Similarly, the powerful Cincinnati

Enquirer remarked that

the opponents of a compromise settlement

of our national difficulties at the

present time consist of two classes-the

Disunionists per se at the South, who

are for breaking up the Confederacy at

any rate, and a class of politicians at

the North who oppose it because it will

run athwart of their peculiar political

views, by which they obtained power and

office.13

Thus Democrats tarred both northern

Republicans and southern

fire-eaters with the same brush of

disunionism. At the same time, by

advocating conciliation, they hoped to

attract to their standard the

conservative masses of the country who

occupied a middle ground

that was essentially antagonistic to the

two radical extremes.

Although Ohio Democrats condemned both

southern radicals and

northern Republicans, they clearly

reserved their most bitter

vituperation for the latter. This was a

crucial point, for when

Democrats continued in a similar vein

after the war began,

Republicans immediately branded such

criticisms as treason.

Democrats generally portrayed secession

as a censurable, but

understandable, response to Republican

antislavery aggression.14

"The Black Republican traitors

& disunionists have done the work,"

wrote Vallandigham; "the

Republicans will not compromise .. ."

Similarly, the Canton Stark County

Democrat placed the cause of

the crisis "at Northern doors-at

Republican hearths." The

Republican party was "avowedly the

unrelenting and bitter enemy

of the South"; now that the Republicans had won control of the

government, the South was rebelling.

"Is it to be wondered at?" the

Democrat queried.15

Several factors accounted for the

special antipathy Democrats held

for Republicans. Partisanship, of

course, was one source of their

bitterness. More importantly, most

Democrats considered antislavery

agitation, and not the existence of the

institution itself, to be

13. Thurman quoted in Columbus Crisis,

February 8, 1861; William Sample to James

Gamble, quoted in bid., February

28, 1861; Cincinnati Enquirer, December 28, 1860.

14. See Cincinnati Enquirer, January

9, 1861.

15. Vallandigham to Dr. J. A. Walters,

January 9, 1861, Vallandigham File; Canton

Stark County Democrat, January 9, 1861. For similar expressions see Cincinnati

Enquirer, December 14, 1860; Columbus Crisis, January 31,

1862; Columbus Ohio

Statesman, December 27, 1860; Circleville Watchman, December

28, 1860.

Ohio Democracy 25

responsible for the country's current

difficulties. The Republican

party, as the political agent of that

agitation, bore the brunt of

Democratic wrath. Democrats flatly

denied the Republican premise

that slave labor and free labor were

incompatible. The two systems

were "not necessarily

antagonistical" in the American system,

commented the Cincinnati Enquirer, "but

for political purposes

efforts have been made to make them

so." One Ohio Democrat

believed that "if the [slavery]

question had not been muddled with

and wantonly made a cause of quarrel, if

we had continued to live as

we formerly did, without making the

question an engine of politics,

we might have lived for one century

longer in a state of perfect

concord." Another charged the

Republicans were "impressed with a

fanaticism of a dangerous moral and

religious sentiment" against

slavery, and wrongly "believe they

are commissioned by a higher law

to carry out the dogmas of their

revolutionary faction."16 Quite

simply, most Democrats did not see

African slavery as an appalling

moral wrong; did not wish it to be

abolished; and wanted agitation

over it to cease. To those Democrats who

viewed the Constitution

with near-mystical reverence, there was

no "higher" law; advocacy

of such a thought was tantamount to

treason.

Exacerbating Democratic fears in this

regard was the talk of

peaceful dissolution that filled the

pages of the Columbus Ohio State

Journal, the Cincinnati Commercial, and other powerful

Republican

organs during the secession winter.17

Such expressions confirmed the

Democratic belief that Republicans, as

much as southern

secessionists, were radical

disunionists. "The whole Republican press

of Ohio will be out in full chorus for

the dissolution of the Union and

the formation of a Northern and Southern

Confederacy," predicted

the Columbus Ohio Statesman, the

voice of the Democracy at the

state capital. "That is what the

[Republican] leaders have been

secretly driving at, their wishes and

desires for dissolution being as

strong as those of Rhett, Yancey, and

Co." The Cleveland Plain

Dealer concurred. Commenting in March 1861 on the early

inactivity

of the Lincoln Administration, this

powerful voice of the Douglas

Democracy observed that "we have no

doubt the administration

16. Cincinnati Enquirer, January

2, 1861; Frederick Grimke to Alexander S. Boys,

April 20, 1861, Boys Papers; John A.

Trimble to Stephen A. Douglas, January 2, 1861,

The Papers of John A. Trimble, Ohio

Historical Society. Also, Columbus Crisis,

January 31, 1861; Canton Stark County

Democrat, January 16, 1861.

17. Eugene H. Roseboom, The Civil War

Era, 1850-1873, vol. IV of The History of

the State of Ohio, ed. Carl Wittke (Columbus, 1944), 373-74, outlines this

Republican

position. See Columbus Ohio State

Journal, November 13, 17, 28, 1860; Cincinnati

Commercial, January 31, February 1, 1861.

26 OHIO HISTORY

policy is this,-Divide the Republic with

as little fighting as

possible. The President and his advisors are Sectional men . . .

they

cannot become National now ..." The administration was carrying

out this policy, the Plain Dealer believed,

in order to maintain itself

in office: "Look to this Black

Republican party for an attempt to

establish two Republics, relinquishing

all power in the one with the

vain hope of perpetually ruling the

other." Likewise, the Ravenna

Portage Sentinel complained that the Republicans "will not

compromise, and rather than yield they

are GOING TO GIVE THE

UNION UP. . . . This is the end which

fanaticism and sectionalism

have wrought for a great

Republic."l8

But while Democrats were disturbed by

the Republican discussion

of dissolution, they found the prospect

of armed coercion to prevent

dissolution no more to their liking. As

the crisis wore on, Republicans

increasingly spoke of the need to employ

coercive measures to keep

the seceding states within the Union.

Democrats at once expressed

their revulsion at such Republican

rhetoric "breathing little else than

vengeance, misery and hopes of bloodshed

. . ." and denounced

Republican policies that were destined

"to drench our country in

fratricidal blood," and "to

plunge the whole nation in a heep [sic] of

ruins." Democrats feared coercion

inevitably would destroy the

delicate fabric of what they held to be

a voluntary union of sovereign

states. Coercion might maintain the

Union in name, but it could only

destroy its spirit. Democrats generally

condemned the Republican

party for being, as Samuel Medary

declared in his Columbus Crisis,

"resolved on revolution and vengeance."19

The Democratic answer to the national

crisis and the perils of

Republicanism was conciliation.

"Moderation is the true policy of the

Northern western Democracy in my humble

judgement," wrote state

Representative William Parr.20 Epitomizing

Democratic efforts in this

regard was the party convention that met

in Columbus on January 23,

1861, to consider the national

difficulties. The assembled delegates

formally declared themselves to be in

favor of any compromise

measure that might be found

acceptable-the proposals of John J.

Crittenden, those of Douglas,

resolutions of representatives of the

18. Columbus Ohio Statesman, February

2, 1861; Cleveland Plain Dealer, March

20, 27, 1861; Ravenna Portage

Sentinel, April 3, 1861. Robert Barnwell Rhett of

South Carolina and William Lowndes

Yancey of Alabama were perhaps the most

extreme of the southern disunionists.

19. A. O. Larason to Samuel S. Cox,

February 5, 1861, Cox Papers; William Bell to

Cox, February 16, 1861, Ibid.; John

Bobo to Cox, January 14, 1861, Ibid.; Columbus

Crisis, January 31, 1861.

20. William Parr to Samuel S. Cox,

January 10, 1861, Cox Papers.

Ohio Democracy 27

border states, "or any other

settlement of our affairs honorable to us

all, which can be effected by

conciliation and compromise, and

mutual concessions of all concerned to

secure the safety and

perpetuity of the Union."

Specifically, they called upon the Ohio

legislature to pass resolutions

requesting a national convention to

propose amendments to the Constitution

that would guarantee the

rights of slaveholders, and upon the

people of the North to give up

such aggravations to the South as

personal liberty laws. In the

clearest of terms, they delcared such

laws to be "nullification," and

therefore no less censurable than

secession: "When the people of the

North shall have fulfilled their duties

to the Constitution and the

South-then, and not until then, will it

be proper for them to take into

consideration the question of the right

and propriety of coercion."21

These boldly stated views served to

foster Republican charges that

the Ohio Democracy was plainly in

sympathy with the South. Many

Ohio Republicans would have agreed with

influential editor William

T. Coggeshall, who tersely noted:

"Dem. State Conven-

tion-Compromised with secession."22

More serious from the

point of view of party harmony,

however, was the danger that some

Ohio Democrats, particularly those who

had been angered by

southern intransigence at Charleston,

would reject the conciliatory

tone assumed by the Columbus delegates.

Indeed, one Douglas paper

from the Western Reserve, the Ravenna Portage

Sentinel, was

outraged at the tenor of the

resolutions:

The South can secede from the

Charleston and Baltimore conventions; they

can prevent the choice of 1,300,000

freemen, and give the election to one who

has no sympathy with their institutions;

. . . declare themselves out of the

Union ... seize the forts ... fire upon

vessels bearing the flag of the Union ...

and more, and yet the Democratic State

Convention of Ohio says in

substance that the North has been the

cause of the trouble .... Out upon all

such Democratic resolutions!

Most Democrats, however, did not appear

to share these

objections. In fact, the Douglas press,

which might be assumed to

have been most frustrated at southern

efforts to defeat their man,

overwhelmingly favored the action of

the convention. The resolutions

had "the ring of the true

metal," commented the Cincinnati

Enquirer, and would be "endorsed by every Democrat and

national

21. The Ohio Platforms of the

Republican and Democratic Parties, 1855 to 1881,

Inclusive (n.p., 1881), 15.

22. William T. Coggeshall Diary entry,

January 23, 1861, The Papers of William T.

Coggeshall, Ohio Historical Society. See

also Columbus Ohio State Journal, January 24,

1861; and Medina Gazette, January

27, 1861.

|

28 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

man in Ohio." The Wooster Wayne County Democrat termed the resolutions "just what they should be; bold, dignified and conciliatory.... Nothing more appropriate could have been said."23 The spirit of compromise and the hope for a peaceable solution to the national troubles struck a responsive chord with most Ohio Democrats. Thus, while the convention did draw criticism, it succeeded in uniting most Ohio Democrats upon a common ground. Throughout the state they earnestly and unceasingly pushed for the adoption of effective compromise measures, as their almost universal support for the Crittenden proposals, the most widely known of the plans, indicated. The Crittenden Plan was "so practicable and so just," one Highland County Democrat wrote, that it "presents itself at once to every calm, reflective and dispassionate mind" as "the remedy" for the crisis. A correspondent of Congressman Samuel S. Cox urged, "For God's Sake, have our folks hold on to the

23. Ravenna Portage Sentinel, January 30, 1861; Cincinnati Enquirer, January 25, 1861; Wooster Wayne County Democrat, January 31, 1861. See also Columbus Ohio Statesman, January 24, 1861; and Georgetown Southern Ohio Argus, February 6, 1861. In addition, although they did not include specific remarks of praise, other Douglas papers placed the resolutions in their editorial columns, indicating an adherence to the principles stated therein: Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 24, 1861; Celina Western Standard, January 31, 1861. |

Ohio Democracy 29

Crittenden proposition."24

But Democratic advocacy of compromise

was not confined to talk;

they also worked actively for a

conciliatory solution. When the

second session of the Fifty-Fourth Ohio

General Assembly convened

in early January 1861, the Democratic

members quickly went on

record in favor of compromise measures.

Although the Democrats

were a decided minority in both houses,

they were more united in

purpose than their Republican opponents

and often were able to

divide them.25 Democrats in

both houses met in caucus soon after

their arrival at the capital and agreed

to endorse the compromise plan

that had been proposed by a committee of

senators and

representatives from the border states.26 In

addition, individual

Democrats in the Ohio House offered

thirteen separate resolutions in

response to the national crisis, all of

which were conciliatory in

tone.27 In contrast,

individual Republican members also offered

thirteen resolutions dealing with the

crisis, each expressing the

24. John A. Trimble to Stephen A.

Douglas, January 2, 1861, Trimble Papers; Joseph

Burns to Samuel S. Cox, January 8, 1861,

Cox Papers; Columbus Crisis, January 31,

1861. See also Cincinnati Enquirer, February

21, March 28, 1861; Canton Stark

County Democrat, February 13, 1861; Celina Western Standard, January

24, 1861;

The Crittenden Plan called for a

series of Constitutional amendments which provided

for the re-institution of the Missouri

Compromise line of 36° 30' and its extension

across the country; the admission to

statehood of any qualified territory with or without

slavery as its Constitution should

provide; and the guarantee that no further

amendment ot the Constitution should

ever be made allowing Congress to touch

slavery in the states.

25. The Republicans held a 58-46

majority in the House, and a 25-10 majority in the

Senate. Columbus Ohio State Journal, October

27, 1859. The Democrats as a group

were much more cohesive in their actions

than the Republicans. In thirteen key roll-call

votes in the House at this session that

dealt with the national crisis, the Democrats had

an "index of cohesion" for

each of the thirteen votes of 100%, 100%, 98%, 92%, 87%,

100%, 95%, 100%, 83%, 100%, 100%, 100%,

100%. In the same thirteen roll calls, the

Republicans' "index of

cohesion" for each of the votes was 49%, 37%, 13%, 47%,

19%, 17%, 72%, 69%, 80%, 14%, 4%, 96%,

100%. An index of cohesion merely

indicates the degree of solidarity that

exists among members of a certain party.

26. The Border State Proposals," as

they came to be called, were similar to the

Crittenden measures. They provided for the repeal of all personal liberty

laws, coupled

with an amendment of the Fugitive Slave

Law to prevent kidnapping; the prohibition of

interference with the interstate slave

trade, coupled with a permanent ban on the

re-opening of the African slave trade;

the re-institution of the Missouri Compromise

line and its extension to the Pacific;

the admission to statehood of any qualified

territory with or without slavery as its

Constitution should provide; and an amendment

to the Constitution prohibiting Congress

from touching slavery within the several

states. Ohio, General Assembly, House of

Representatives, Ohio House Journal, 54th

General Assembly, January 8, 1861, 12.

27. Two resolutions called for Ohio to

send commissioners to confer with the Border

State representatives; one denounced

coercion in general terms; one enjoined the Ohio

militia from making any military

preparations unless and until Kentucky's did so; two

denounced all personal liberty laws; and

seven called for a national convention to meet

to consider means to guarantee the

rights of slaveholders through Constitutional

30 OHIO HISTORY

general Republican unwillingness to

compromise with the South.28

Democrats hoped that their unity would

enable them to control the

actions of the legislature.

Specifically, they wished to pass a law

preventing Negro immigration into Ohio,

another making it illegal to

aid fugitive slaves, and other

legislation and resolutions unmistakably

conciliatory in tone. Such measures

might in fact have little practical

effect, but they would serve to

demonstrate to southerners, as

Representative George Converse put it,

that "a terrible reaction is

going on in Ohio." They failed,

however, to effect decisive positive

action. "Our movements here are

tardy & stupid-Everything looks

blue or black," lamented Senator

George W. Holmes midway through

the session. "Let our prayers be

delivered from the curse of

Republican rule and domination."29

Despite the absence of dramatic

accomplishment, by uniting with

Republican conservatives the Democrats

were able to check the

actions of the radicals. The general

tone of legislative action remained

conciliatory. Due largely to Democratic

pressure, the legislature

provided for Ohio to send commissioners

to the Washington Peace

Conference. Late in the session

Democrats won passage of a

resolution calling for a national

convention of the states. Still later,

the legislature passed the Corwin

Amendment.30 The Washington

Conference, however, was a dismal

failure. Two months of debate

were required to secure passage of the

resolution calling for a national

convention, and the Corwin Amendment was

approved only after

hostilities had commenced.

The legislative record in regard to

compromise was thus a mixed

amendments; of these, two specifically

endorsed the Crittenden proposals. Ibid.,

January 7, 8, 11, 14, 17, 21, 24, 1861,

pp. 5-6, 12, 13, 32, 45-46, 64-65, 66, 77-78.

28. One resolution demanded no extension

of slavery into the territories, one called

in general terms for the preservation of

the Union; one suggested that all further

resolutions dealing with the secession

crisis be referred to committee without

discussion; one condemned all compromise

proposals then under consideration; two

opposed any amendments to the

Constitution to guarantee slavery; two repudiated

secession; two called for Ohio to be

militarily prepared; and three called for the

enforcement of all the Federal laws. Ibid.,

January 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 18, 1861, pp. 5, 10,

11, 28, 30, 32-33, 35, 37, 72-73.

29. George Converse to Samuel S. Cox,

January 9, 1861, and George W. Holmes to

Cox, February 27, 1861, Cox Papers.

30. The Corwin Amendment, the

result of the work of the House of Representatives

Committee of Thirty-three, chaired by

Ohio Republican Thomas Corwin, provided that

"no amendment shall ever be made to

the Constitution which will authorize or give to

Congress power to abolish or interfere,

within any State, with the domestic institutions

thereof, including that of persons held

to labor or service by the laws of said State."

Ohio and Maryland were the only two

states to ratify the amendment. See R. Alton

Lee, "The Corwin Amendment in the

Secession Crisis," Ohio Historical Quarterly,

LXX (1961), 1-26.

Ohio Democracy 31

one, but most Democratic members

regarded the session as a

complete failure. But their failure did

not diminish the sincerity of

their effort. In debate over various

specific issues, Democrats spoke

in general terms which encompassed the

entire question of sectional

bitterness and secession and which

clearly illustrated the basic tenets

of the Democratic ideology:

conservatism, constitutionalism, racism,

and especially an overwhelming desire

for compromise. When

Representative Joseph Jonas discussed

at length the merits of a bill to

prohibit giving aid to fugitives from

servitude, he concluded his

remarks by speaking to the larger issue.

"We are also discussing a

compromise by which we can harmonize

with our Southern brethren,

and more especially with the Border

States . . .," he told his

colleagues. "If we remain

obstinate and uncompromising, as sure as

we now stand here the Border Slave

States will also secede, and civil

war will prevail in all its

enormities." The rights of the slaves or the

morality of the institution of slavery

were of little concern to

Democrats such as Jonas when weighed

against the spectre of

dissolution of the Union. "The

Democracy of the North and West are

opposed to slavery, but we respect the

rights of the South," he

concluded. "Are we to ruin our

glorious republic for an inferior

race?"31 Likewise,

Representative W. C. Moore, speaking for

passage of the same bill, discussed

fully the entire slavery question.

Although "in common with my

Democratic brethren of the North"

Moore was "opposed to

slavery," he argued that southern

slaveholders needed a "positive

guarantee" against the "false

philanthropy" of the

"anti-slavery sentiment of the north," which

had led some deluded northerners to

steal slaves from their

"comfortable home" and to

throw them "on society here." Moore

denounced "sacrificing the high

destinies of the Anglo Saxon race

upon this continent" in order to

"gratify an unnatural sympathy for

the slave."32 Democratic members

in general bridled at Republican

"abolitionism, mingled with

coercionism," as Representative Henry

L. Dickey put it. "Gentlemen, you

must come down from your higher

law, you must humble yourselves before

the Constitution and laws of

our common country and beg their

pardon....."33

Such rhetoric demonstrated Democratic

desire for conciliation, but

it did little else. Certainly it was

powerless to stay the course of

31. Quoted in Columbus Crisis, March

20, 1861.

32. Quoted in Columbus Ohio

Statesman, March 1, 1861.

33. Henry L. Dickey, "Freedom is

Always Within the Union: Despotism Follows

its Downfall," Speech of Hon.

Henry L. Dickey on the Duty of Ohio in the Present

Crisis (Columbus, 1861), 15,16.

32 OHIO HISTORY

events. As the legislators wrangled, the

nation edged closer to open

hostilities. With the firing upon Fort

Sumter, the Democrats' worst

dread, civil war, with its concomitant

threats to the tenets of the

Democratic orthodoxy, was at hand.

Nevertheless, Ohio Democrats

reacted to the outbreak of war with

ready support of Lincoln's call for

troops; the use of armed force by the

South had roused their martial

ardor. The South's overt act had made

the issue a clear one: the war

was to be waged to restore the Union and

defend the government.

"Devotion to the National flag is

the religion of the hour," wrote the

Cleveland Plain Dealer. Even Samuel Medary, soon to be one of

the most bitter "Copperhead"

critics of the administration, pledged

his allegiance to the war effort.

"We can offer our old friends [of the

South] no encouragement now," he

wrote shortly after the fall of Fort

Sumter. "We must now have every

star retained on our old and glorious

flag.... 34

But Democrats quickly made it clear that

they supported the war

effort expressly to restore the Federal

Union; not to abolish slavery.

They stressed that the conflict must not

be allowed to become, as the

Columbus Ohio Statesman put it,

"a war of invasion, subjugation

and desolation." From the outset

Democrats feared that radical

Republicans would attempt to transform

the war into an abolitionist

crusade. Equally important, many

Democrats feared that the

Republicans would attempt to use wartime

conditions to abrogate the

traditional civil rights that they held

sacred. "The great problem to

work out now," observed Medary,

"is whether we can pass through

the ordeal and retain our individual

freedom." Similarly, while the

Cincinnati Enquirer declared unequivocally that "the UNION MUST

BE SUSTAINED," it also warned,

"let us not forget that we are to

preserve the Constitution also,

and maintain the laws inviolate, for what

would the Union be worth without the

Constitution and the laws?"

Consequently, Democrats kept a sharp eye

on the conduct of the

administration from the beginning of

hostilities. Only weeks into the

war, for example, William Parr bitterly

complained that Lincoln, by his

"unconstitutional acts," was

making himself "the perfect Monarch."35

34. Cleveland Plain Dealer, April

24, 1861; Columbus Crisis, April 25, 1861. Fo

similar Democratic expressions see

Celina Western Standard, April 18, 1861

Georgetown Southern Ohio Argus, April

21, 1861; Newark Advocate, April 19, 1861

A correspondent of John Sherman noted

the Democratic ardor, writing shortly after the

outbreak of hostilities, "There are

no parties in Ohio-all are for the Union and fol

sustaining the Government-In fact I am

not certain but that the Democracy are not thl

most enthusiastic in favor of sustaining

the Administration" (S. E. Brown to Sherman

May 1. 1861, Sherman Papers).

35. Columbus Ohio Statesman, May

3, 1861; Columbus Crisis, April 25, 1861

Cincinnati Enquirer, May 1, 1861; William Parr to Samuel S. Cox, July 9,

1861, Co:

Ohio Democracy 33

Democratic support for the war at its

outset, then, may be

characterized as willing, but

conditional. In their assiduity to maintain

the forms of free government in wartime

lay the seeds for their

subsequent bitter conflicts with Lincoln

and his party. While it was

clear that Ohio Democrats would fight

for the preservation of the

Union-as the enlistment rolls

attested-it was equally clear that most

of them still preferred to achieve that

result by conciliation rather

than conquest. Not surprisingly, given

these factors, most Ohio

Democrats believed that their party was

the one best capable of

bringing a peaceful end to the strife.

Even before the outbreak of war,

Democrats pinned their hopes for

sectional settlement upon their

success at the polls. Convinced that a

powerful reaction against the

fruits of the Republican victory was

already at work in the North,

Democrats were quick to read significant

results into even the most

inconsequential local elections. The

Canton Stark County Democrat

enthused that the Democratic triumph in

that city's elections in early

April was "a glorious victory for

the friends of our undivided

American Union. . . . Whenever the

country is in danger, safety is

sought and found in the conservative and

safe counsels of the

Democratic party." Similarly, the Cleveland

Plain Dealer and the

Cincinnati Enquirer both hailed Democratic municipal victories in

Ohio's two largest cities as the onset

of a "Great Union movement"

and evidence that "the ball of

revolution [has] commenced here"

against the evils of dissolution under

Republicanism.36

Although such victories created

momentary exuberance and good

editorial copy for Democratic

journalists, the will of the people in

regard to the national crisis was best

gauged in the fall election when

the new state administration was to be

chosen. But it was during the

campaign of 1861 that the Ohio Democracy

began once again to

founder on the rocks of internal

divisiveness. At issue was the Union

party movement which first surfaced

during the summer of 1861. In

June the Republican central committee

called upon all Ohioans

"without reference to"

previous party affiliations, to join

together-under Republican auspices-to

present a united political

front in order to demonstrate to the

South northern solidarity. The

majority of the Democratic press and the

leadership of the state party

opposed the movement, seeing in it a

political maneuver by the

Papers. See also Celina Western

Standard, May 9, 1861; Gerogetown Southern Ohio

Argus, July 3,

1861; Newark Advocate, April 19, 1861.

36. Canton Stark County Democrat, April

3, 1861; Cleveland Plain Dealer, April

10, 1861; Cincinnati Enquirer, April

2, 1861. Republicans objected bitterly to the

Democrats "thrusting national

politics into ... city affairs" (Cincinnati Commercial,

March 19, 1861).

34 OHIO HISTORY

Republicans to lay party claim to the

spirit of patriotism and devotion

to country to attract Democratic

votes-particularly in Democratic

districts-in order to gain electoral

victory. The Dayton Empire, the

powerful voice of Vallandigham in

southwestern Ohio, complained

bitterly that

it was all right enough for the

Republicans to make party nominations in

[Thomas] Corwin's and [John] Sherman's

districts because the Republicans

have a majority in these Districts, but

for the Democrats to insist on

preserving their organization, is all

wrong. It is worse, it is "Treasonable" in

their eyes. The truth is these

[Republican] journals fear the result of the

election.37

Accordingly, the Democratic state

committee summarily rejected

the Republican call, and instead

proceeded with plans to hold its own

convention in Columbus in August. At the

same time, however, a

relatively small but significant number

of Democrats decided that in

good conscience they must support the

war effort by a show of

political solidarity. "Let us for

once go out of party harness," the

Cleveland Plain Dealer urged, "while we give to our glorious but

endangered country our every thought and

energy." The great and

overriding question presented by the

rebellion, wrote one Ohio

Democrat to his congressman, was

"whether we now have, and shall

have to all future time, a government?

or whether we are to be broken

by the power of Southern traitors."

Enough Ohio Democrats shared

these concerns to insure a muddled and

divisive campaign.38

But the great mass of Ohio Democrats,

along with the regular party

leadership, believed they could best

serve the cause of the Union

from within the party. Indeed, given the

Democratic belief that

Republicans as well as secessionists

were responsible for the conflict,

any other course would have been most

surprising. "I am firm of the

opinion that the only policy for the

Democratic party to pursue is to

preserve its organization intact [and]

nominate a thorough Democratic

ticket of tried and true men,"

wrote one Ohio Democratic planner. "I

am unable to see what some of our men

expect to gain by [a] Union

ticket. We have always been Union men

since the organization of our

party. .. ." In a similar vein,

Samuel Medary declared that Ohio

Democrats would have "nothing to

do" with any cooperative effort

with Republicans but would instead

"have a Union Ticket made up

37. Dayton Empire, July 13, 1861.

See also Cincinnati Enquirer, July 7, 1861;

Columbus Ohio Statesman, July 27,

1861; Celina Western Standard, June 23, 1861;

Georgetown Southern Ohio Argus, July

3, 1861; Newark Advocate, July 5, 1861, for

similar views.

38. Cleveland Plain Dealer, June

5, 1861; Uriah Heath to Samuel S. Cox, July 13,

1861, Cox Papers.

|

Ohio Democracy 35 |

|

|

|

of all sound, honest, reliable Democrats and nothing else." The Cincinnati Enquirer announced that "Democrats cannot have any cordial political union with Republicans" because the Lincoln Administration had already "usurped powers, violated personal rights of citizens, and trampled upon some of the dearest privileges guaranteed by the Constitution." Vallandigham urged the "maintainance [sic] of the organization & integrity of the Democratic party" to provide "an ancient & still admirable machinery" with which "to safe [sic] the Constitution & public & private liberty" and "restore the Union...."39 Thus when Democratic delegates convened at Columbus in August 1861 to rechristen themselves the "Democratic-Union" party, nominate a ticket, and formulate a platform, they did not believe they were guilty of unseemly partisanship. Rather, they felt they were following the surest course to a peaceable restoration of the Union.

39. B. F. Potts to Samuel S. Cox, June 30, 1861, Cox Papers; Columbus Crisis, June 20, 1861; Cincinnati Enquirer, July 7, 1861; Clement L. Vallandigham to Alexander S. Boys, August 13, 1861, Boys Papers. |

36 OHIO HISTORY

They nominated Hugh J. Jewett, a Douglas

Democrat and an

unwavering Union man, for governor. In

their platform they

emphasized once again the need for

compromise and conciliation to

end the conflict and bring the seceded

states back into the Union.

Stressing familiar Democratic points,

they labeled the war "the

natural offspring of misguided

sectionalism, engendered by fanatical

agitators, North as well as South."

They vowed their support to the

war effort, but again stressed that its

aims must remain "to defend

and maintain the supremacy of the

Constitution, and to preserve the

Union with all the dignity, equality and

rights of the several States,

unimpaired." Further, they renewed

their call for a national

convention "for the purpose of

settling our present difficulties and

restoring and preserving the

Union." It is significant that Democratic

advocacy of peace and reunion by

compromise during the summer of

1861 was not adopted after the war had

begun, but rather was a

reiteration of a position they had taken

at the outset of the crisis.40

Clearly, such beliefs were becoming

increasingly tenuous with

significant numbers of the Democracy as

the war continued. The

Cleveland Plain Dealer, for example, questioned the efficacy of

continued attempts at conciliation by

asking:

Shall we propose terms of peace to armed

traitors or dictate terms of peace to

disarmed traitors? With the overawed

loyal people of the South we have

neither opportunity nor occasion to

treat. Our business is with armed traitors

who steadily declare they want no terms

and will accept no terms of Union,

even if they were handed blank paper

with permission to write the terms from

which there should be no appeal.41

Further complicating the situation was

the fact that the Union party

movement of 1861 was, at least

nominally, just that. Three of the

seven nominees on the Union state ticket

were Democrats, including

gubernatorial candidate David Tod. Tod

had been the chairman of the

Baltimore convention which had nominated

Douglas in June 1860,

and had supported the various compromise

proposals prior to the

outbreak of the war. At the state Union

convention in Columbus in

early September, the Republican leaders

who had initiated the

movement consciously sought to insure

that the proceedings would be

"harmonious," in the term of

Republican editor William T.

Coggeshall. They chose a conservative,

veteran Whig, Thomas Ewing,

to chair the convention, and his address

keynoted the Union effort to

attract Democratic support. "The

Ship of State is among breakers

40. The Ohio Platforms of the

Republican and Democratic Parties, 15-16.

41. Cleveland Plain Dealer, September

11, 1861.

Ohio Democracy 37

now," Ewing told the delegates.

"I do not propose to inquire what

Lincoln has done or what Buchanan has

done; let all that pass. Let all

past differences among us be laid aside;

our duty is to save the

country." Implicit in Ewing's

remarks was the assertion that only the

Union party was capable of that task.

The delegates then endorsed

the Crittenden Resolutions, recently

passed by Congress, which

declared in part that the war was not to

be waged for the purpose of

"conquest or subjugation," nor

to interfere with the "rights or

established institutions" of any of

the states, but rather was to

"maintain the supremacy of the

Constitution"; once this object was

attained, "the war ought to end.'42

Because Tod was nominated and the

Crittenden Resolutions

embodied the views of most Democrats

concerning the conduct of the

war, a muddied campaign was insured.

Further, in many respects the

Union campaign took on aspects of a

great eulogy for the recently

deceased Douglas. Republican newspapers

which had vilified the

Little Giant now published with warm

praise exerpts from his last

speeches supporting the war effort. The

issue was so clouded that

Democratic voters could leave their

regular party and still vote for

one of their own, Tod, a champion of

their dead leader Douglas, and

for a platform that largely echoed that

of the Democracy. At one

point before the Union convention, the Cleveland

Plain Dealer, the

most powerful Democratic organ to join

the movement, was able to

endorse the nominations of the regular.

Democratic convention. On

the other hand, the Cincinnati

Enquirer, a staunch foe of the Union

party, remarked shortly before the election

that "the candidates upon

both sides occupy the same position as

regards the vigorous

prosecution of the war, all being in

favor of it, so that on that question

there is no choice."43

Because of this similarity in tickets

and platforms, and because of

the abiding attention most northerners

gave to military operations, the

canvass itself was an unusually

desultory one. Although acrimony on

both sides existed, the usual campaign

furor was absent. "Thus far

there has been a remarkable degree of

public indifference concerning

this election," observed the Cincinnati

Commercial only a week

before election day. While Unionists

anticipated a victory, there were

by no means sure of it. Similarly, while

Democrats spoke hopefully of

42. Proceedings of the Great Union

Convention of Ohio (Cleveland, 1861), 17-19,

20-24, and passim; William T.

Coggeshall Diary entry, September 5, 1861, Coggeshall

Papers; Ewing quoted in Smith, Republican

Party in Ohio, I, 138; Crittenden

Resolutions quoted in Cincinnati Commercial, July

29, 1861.

43. Cleveland Plain Dealer, August

14, 1861; Cincinnati Enquirer, October 4,

1861.

38 OHIO HISTORY

a triumph, they professed to be ready to

accept defeat with

equanimity.44

Ultimately, the Union ticket swept to

victory. Tod defeated Jewett

by a majority of 55,223 votes, running

well ahead of the total obtained

in 1859 by William Dennison, the

Republican winner in the previous

gubernatorial contest. Although Tod

increased Dennison's majorities

in heavily Republican areas, it was

clear the truly decisive factor was

the crossover vote in areas previously

controlled by the Democracy.

Tod carried sixty-two of Ohio's

eighty-eight counties, or 70 percent;

in 1859 Dennison had carried forty-eight

counties, or just over half.

Jewett's total was nearly twenty

thousand less than that of the

Democratic standard bearer of 1859.

Similarly, Democratic votes

helped to win for the Unionists an

overwhelming majority in the state

legislature. In addition, of the

Unionist totals of sixty-six

Representatives and twenty-six Senators,

thirty-two and five,

respectively, were Union Democrats.45

Clearly, Tod's appeal and that

of the entire Union campaign had been

focused to attract Democratic

support. It had been overwhelmingly

successful. But for this very

reason, Democrats who had opposed the

Union movement could

view the election results and feel far

from discouraged. Some believed

the party had had what amounted to two

tickets in the field. The

Cincinnati Enquirer claimed the results indicated the first signs of a

"political revolution" in

Ohio. The Cleveland Plain Dealer, an

advocate of the Union party, remarked

that the victory had been as

much a Democratic triumph as a

Republican one. Moreover, while it

was true that a significant number of

Democrats had voted the Union

ticket, the regular Democracy clearly

remained the political home of

the great majority of the party's rank

and file. Democrats throughout

Ohio believed, at least in terms of

grass roots support, that the

Democracy was the state's dominant

party.46

The split in the Ohio Democracy during

the campaign of 1861, only

indicated the deeper rift that was to

develop between the "War

Democrats" and the regular party.

The "War Democrats," who

remained a decided minority, generally

were to support the Union

party and the Lincoln Administration in

its conduct of the war for the

duration of the conflict. The regular

Democrats, by far the majority of

44. Cincinnati Commercial, October 1, 1861. Feeling approximately the same

public pulse, the Cincinnati Enquirer

remarked shortly thereafter that "very little

interest is manifested by the people in

the election ..." (Cincinnati Enquirer, October

6, 1861).

45. Smith, Republican Party in Ohio, I,

95, 140.

46. Cincinnati Enquirer, November

15, 1861; Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 16,

1861.

|

Ohio Democracy 39 |

|

|

|

the prewar party, continued to support the war for the restoration of the Union, but bridled at what they believed to be usurpations by the Lincoln Administration in the prosecution of the war. The President's emancipation policy, inaugurated in 1862, was particularly repugnant to them. Peaceful sectional compromise remained central to their program. Condemned as "Peace Democrats" or "Copperheads" by their political rivals, these Democrats continued throughout the war to preach the same basic doctrines that they had adopted immediately following the election of Lincoln. Their condemnation of all extremists, and their advocacy of conciliatory measures to preserve the Union, had been during the secession winter both a patriotic embodiment of Democratic ideology and an effective political strategy. However, it became increasingly anachronistic as the conflict wore on. "The Union as it was, the Constitution as it is" was an epigrammatic summary of the Democratic hopes and, in 1861, one that seemingly had a fair chance of accomplishment. But as the war ground on and became ever more massive in its effects, the saying became little more than an empty political slogan. All this should not obscure the fact that northern Democrats conceived of themselves as the true men of the Union, the true |

40 OHIO HISTORY

defenders of political liberty, and the

guardians of the American

system of government. Within the limited

framework of their own

ideology, moreover, they were correct.

Certainly the Republicans

bore little allegiance to the Union

"as it was," nor, as events were to

show, to the Constitution "as it

is." The most rabid critics of the war

could agree, clear of conscience, with

the sentiments of

Vallandigham, who wrote less than a year

prior to his arrest for

treason: "We are the loyal men: we

are the Union men."47 That there

was even a modicum of truth in this

declaration has seldom been

recognized. Yet the Democrats were

fiercely loyal; loyal to an older,

federalized American Union that was

passing from the scene forever,

unable to withstand the irresistable and

irreversable forces of

modernization and the exigencies of a

massive civil war.

47. Clement L. Vallandigham to Dr. J. A.

Walters, June 15, 1862, Vallandigham File.

ERIC J. CARDINAL

The Ohio Democracy and the

Crisis of Disunion, 1860-1861

One of the least understood political

groups in American history

has been the northern Democratic party

during the Civil War. Their

contemporary Republican foes vilified

them as traitors, and

subsequent historians have for the most

part agreed with that

verdict.1 Political

partisanship, ideological conflicts, and wartime

passions account for the original

animus; it is less clear why scholars

have tended to follow so closely the

Republican lead. The primary

reason for the continuing bad

reputation of the wartime Democrats is

that they, nearly as much as the

confederates themselves, "lost" the

war and thus the legitimacy of their

position. The war destroyed their

hopes for the preservation of "the

Union as it was and the

Mr. Cardinal is a Teaching Fellow at

Kent State University where he is in the final

stages of work on his dissertation, a

project being advised by Professor Frank L.

Byrne.

1. See for example Curtis H. Morrow, Politico-Military

Secret Societies of the

Northwest, 1860-1865 (Worcester, MA, 1929); Leonard Kenworthy, The Tall

Sycamore of the Wabash: Daniel Wolsey

Voorhees (Boston, 1936); Wood Gray,

The Hidden Civil War: The Story of

the Copperheads (New York, 1942);

George F.

Milton, Abraham Lincoln and the Fifth

Column (New York, 1942); Christopher

Dell, Lincoln and the War Democrats:

The Grand Erosion of Conservative

Tradition (Cranbury, NJ, 1975); F. L. Grayson, "Lambdin P.

Milligan-A Knight of

the Golden Circle," Indiana

Magazine of History, XL (1947), 379-91; Frank C.

Arena, "Southern Sympathizers in

Iowa During the Civil War Period," Annals of Iowa,

XXX (1951), 486-538; Bethania M. Smith,

"Civil War Subversives," Journal of

the Illinois State Historical

Society, XLV (1952), 220-40; Robert S.

Harper, "The

Ohio Press in the Civil War," Civil

War History, III (1957), 221-52, which are studies

embracing, in whole or in part, this

general conception. This is not an exhaustive list,

nor does it fully indicate the

pervasiveness of this view of the northern Democracy. For

example, Norman A. Graebner et al., A

History of the American People (New York,

1975), 423; and Keith I. Polakoff et

al., Generations of Americans: A History of the

United States (New

York, 1976), 366 are two recently-published texts that reflect this

view.

For lucid critiques of the interpretive

literature concerning the northern Democrats,

see Richard O. Curry, "The Union as

it Was: A Critique of Recent Interpretations of

the 'Copperheads,' " Civil War

History, XIII (1967), 25-39; and Robert H. Abzug,

"The Copperheads: Historical

Approaches to Civil War Dissent in the Midwest,"

Indiana Magazine of History, LXVI (1970), 40-55. For balanced views of the

"Copperheads" which tend to

revise the traditional picture see Frank L. Klement, The

Copperheads of the Middle West (Chicago, 1960); and Idem, The Limits of

Dissent: Clement L. Vallandigham and the Civil War (Lexington, 1970), in addition

(614) 297-2300