Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

K. AUSTIN KERR

The Movement for Coal Mine Safety

in Nineteenth-Century Ohio

In the nineteenth century Ohioans, as

other Americans, faced a host

of new situations arising from the

industrial revolution. As the level of

industrial production increased, unique

forms of occupational

organization emerged which often

confronted workers or the public with

unaccustomed hazards, creating demands

that government begin

regulating the affairs of private

industry. By the 1860s state government

began addressing the special dangers in

the railroad and coal mining

businesses, two industries which were

essential in the burgeoning

economy. The growth of coal mining

brought peculiar dangers new to

miners in America.

During the winter of 1869-1870 miners

began agitating for state

enactment and enforcement of mining

regulations. Their initiatives

questioned prevailing ideologies

concerning the proper relationship

between the government and the

governed. The legislature in 1871

designated a Mining Commission to

investigate the working condi-

tions of the state's mines, and enacted

a statute in 1872 defining

health and safety standards in the

growing industry. In 1874 it

provided the first bureaucratic and

professional means of enforcing

the mining code by creating the post of

State Inspector of Mines. In

1882 it designed a means of insuring

that the Inspector and his

assistants were qualified persons, and

subsequently in the decade,

along with the Board of Trustees of

what was to become The Ohio

State University, funded an active

Department of Mines to provide

the educational basis for achieving

mine safety. Behind this

century-old legislative outline lay a

controversy which revealed the

origins of government

"welfare" policies, the beginnings of a struggle

which lasted at least through the 1930s

to have the state and federal

government assume responsibility for

improving the conditions of

work in the industrial age.

The story of the beginnings of coal

mine health and safety

Dr. Kerr, Associate Professor of History

at The Ohio State University, received

research assistance for this article

from Susan Busey, Michael J. Fitsko, Gerald Huss,

Michael R. McCormick, and Daniel

Schneider.

4 OHIO HISTORY

regulation extended from the anthracite

fields of northeastern

Pennsylvania across the bituminous

centers of Illinois, and in the

early 1870s the subject caused

political controversy in three states:

Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois.1 It

involved several significant

themes in the unfolding of American

history. The movement stemmed

in part from the flow of men and ideas

across the Atlantic from Great

Britain, and the struggles for union

organization, political reform, and

mine regulation on that island. It

resulted from the growing

importance of coal in fueling the

nation's emerging industrial

economy. It concerned a growing

ideological clash prompted by

men's perceptions of the differences of

economic interest between

employer and employee, of capital and

labor, and efforts to seek

public policies to ease, if not

eliminate, industrial conflict. The

miners' movement for state regulation

of working conditions revealed

that the political system of the Gilded

Age was capable of responding

in a positive and sympathetic way to

the perceived interests of

industrial workers.

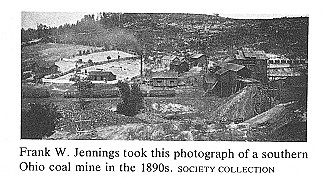

Americans discovered in the nineteenth

century that their land was

rich in coal resources. As did other

states, Ohio commissioned a

geological survey which began to report

in 1838 on the state's mineral

resources.2 But the ability

of entrepreneurs to mine coal profitably

was dependent on the development of

inexpensive transportation

systems and, once coal outcroppings on

the earth's surface were

exploited, to find men with the

technical skills that deep underground

mining required. Coal was mined

commercially before the Civil War

along water routes; and by the 1860s

men were digging substantial

tonnages in the Mahoning and Tuscarawas

valleys. The full opening

of the rich Hocking Valley reserves

awaited the building of rail lines

into the region, a task nearing

completion in 1870.3 As for the skills

needed for underground mining, Ohio

businessmen, as their

counterparts elsewhere in the United

States, looked to the experience

of British miners. British miners were

recruited as early as the 1820s

1. Alexander Trachtenberg, The

History of Legislation for the Protection of Coal

Miners in Pennsylvania, 1814-1915 (New York, 1942), 23-76; Earl R. Beckner, A History

of Labor Legislation in Illinois (Chicago, 1929), 283-345.

2. Ohio, Geological Survey,First

Annual Report of The Geological Survey of the

State of Ohio (Columbus, 1838).

3. David G. Taylor, "Hocking Valley

Railroad Promotion in the 1870's: The Atlantic

and Lake Erie Railway," Ohio

History, LXXXI (Autumn 1972), 263-64. Statistics o

coal production before the census of

1880 were at best estimates. Ohio, Inspector o

Mines, Sixth Annual Report (Columbus,

1881), 8-10.

Coal Mine Safety

5

to develop anthracite seams in eastern

Pennsylvania, and by the 1860s

midwestern coal fields were dotted with

British migrants.4

The recruitment of British miners proved

a mixed blessing for coal

operators, however. The colliers were

schooled in the traditions of

their homeland's Chartist agitation and

the emerging British union

movement which, operating from a

perceptual basis of

class-consciousness, expressed a growing

determination to reform the

political system in order to ameliorate

the welfare of workers.

American miners lived in relatively

isolated coal camps; not only did

they maintain their cultural identity

thereby, but a constant flow of

men back and forth across the Atlantic

seeking economic opportunity

insured a continuing contact with the

British union movement. The

ramifications were important in America,

and in Ohio, as events

proved in the 1870s. Miners began to

express attitudes of class-

consciousness, consequent initiatives at

early trade union

organization, and the first mass

movement to direct government

action in the distinct interests of

workers.5

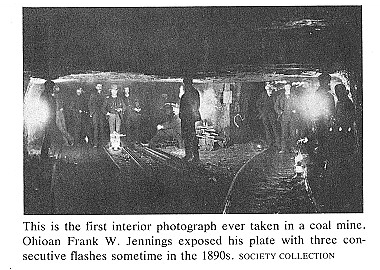

British miners at mid-century focused

their political attention upon

the improvement of underground working

conditions. Mining was an

inherently dangerous occupation. It

posed special problems of

cave-ins, flooding, and ventilation.

Shafts had to be supported

properly, pumps provided to remove

water, and steady air currents

supplied to carry off the wastes of

human and animal toil, smoke from

blasting powders, and the deadly

explosive methane gas (called "fire

damp" in the jargon of the day). In

response to miners' agitation

Parliament began in 1850 to devise

safety codes and an inspection

system.6

British miners migrating to America

brought these safety concerns

with them and by the 1860s were asking

their state governments to

emulate the British example. Traditions

of class-consciousness

combined with economic frustrations and

observations of dangerous

working conditions, prompted miners in

Pennsylvania, Ohio, and

Illinois to form unions whose principal

political objective in the

decade after the Civil War was to

achieve a system of state mine

4. The 1870 census showed that at least

one-third of Ohio's miners were born in

Britain; Charlotte Erickson, American

Industry and the European Immigrant,

1860-1885 (Cambridge, MA, 1957), 107.

5. A standard account of British

influence on the American labor movement is

Clifton K. Yearley, Jr., Britons in

American Labor (Baltimore, 1957), 123-41.

6. No modern history of the entire

British mine safety movement has been

published, but see O. O. G. M.

MacDonagh, "Coal Mines Regulation: The First

Decade, 1842-1852," Ideas and

Institutions of Victorian Britain, ed. Robert Robson

(New York, 1967), 58-86. An informative

nineteenth-century history written by an

engineer is R. Nelson Boyd, Coal Pits

and Pitmen (London, 1892).

6 OHIO HISTORY

inspection.7 America's first

spectacular mine disaster at Avondale,

located in Luzerne County, Pennsylvania,

which cost the lives of 110

workers on September 6, 1869, lent an

emotional fervor to the cause

and prompted Ohio miners to begin

agitation for state safety

regulations.8

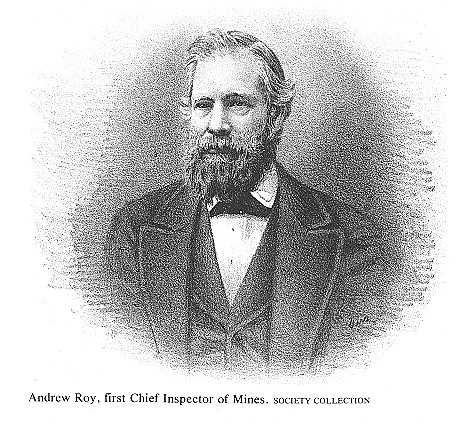

The Avondale disaster spurred the miners

of the Mahoning and

Tuscarawas valleys and their unions to

mount a campaign for state

intervention. The leaders included

William Thomson of Mineral

Ridge, educated at the University of

Edinburgh before settling in the

Mahoning Valley; John Pollock,

Irish-born and active in the Scottish

miners' union before migrating to the

Tuscarawas Valley where he led

the local union movement; and Scotsman

Andrew Roy, who, after

recovering from Civil War wounds,

settled near Youngstown and

educated himself in mining engineering,

geology, and the British

inspection system.9 Roy's

knowledge allowed him to emerge as the

leading figure in the Ohio safety

movement and eventually become

the first State Inspector of Mines in

the nation.

These experienced miners and their

followers were appalled by the

condition of the state's mines.

Businessmen eager for rapid return on

investment often failed to offer even

the most rudimentary safety

provisions. They resisted supplying

adequate timbers for the "dead

work" of shoring roofs. Or they

failed to insure adequate drainage in

places where water posed special hazards

of flooding. Too often

inadequate means of ventilation were

constructed, or no artificial

ventilation provided. Worst of all, the

simple safety of building double

entries to all working places was

overlooked in search of cost

economy. The Avondale disaster had

resulted when the single

wooden shaft of the mine ignited and the

men, not having an escape

route, suffocated. Miners all over the

country agitated for a law

forcing operators to invest in double

means of egress to forestall such

disasters. Nor was this the only goal

the men championed. Detailed

and standardized mine maps were needed

in case of accident, or to

7. The only narrative history of the

miners' unions in nineteenth-century America is

Andrew Roy, A History of the Coal

Miners of the United States (Columbus, 1907).

A history of the first bituminous

miners' union is Edward Wieck, The American

Miners Association (New York, 1940).

8. Trachtenberg, History

ofLegislation, 23-41. A mine accident is termed a "disaster"

when five or more persons are killed in

a single incident. For an account of the Avondale

disaster by a local newspaper editor,

see H. W. Chase, An Account of the Unparalleled

Disaster at the Avondale Colliery,

Luzerne County, Pa., September 6th, 1869, by which

One Hundred and Ten Lives were Lost (Scranton, 1869).

9. Edward Pinkowski, John Siney, The

Miners' Martyr (Philadelphia, 1963), 136;

Roy,History of the Coal Miners, 125-26; "American Labor Portraits-Andrew

Roy,"

Workingman's Advocate, January 17, 1874.

Coal Mine Safety

7

insure that future operations of

neighboring mines did not lead to

unnecessary hazards. Safety appliances

on elevators and mine cars

had to be tested and provided. Safe

mining required a reliable

communication system to every seam being

worked and supervision

of the use of safety lamps.10

The miners were unwilling to rely upon

the beneficence of coal

operators to apply the necessary safety

measures. Their leaders were

experienced and educated men who

observed that operators were

ignorant of safety concerns and hostile

to encumbering any expense

for the improvement of working

conditions. The British experience

taught them that mine safety could be

improved only by government

supervision. Caught up in the American

labor reform movement of

the era which instructed that society

was dividing rapidly into two

social classes, labor and capital, the

miners turned to democratic

government for redress against

businessmen who seemed mainly

interested in profiting from the value

created by labor.11

After discussing safety matters in the

columns of local newspapers

in the winter of 1869-1870, the miners had Andrew Roy

draft a bill to

submit to the 1871 session of the

General Assembly. Roy and John B.

Lewis, President of the Miners' and

Laborers' Benevolent

Association in the Mahoning Valley, went

to Columbus to lobby for

its passage. The bill outlined the

miners' observations concerning

safety requirements. Most important to

the miners, it divided the

state into two inspection districts and

designated two Mine Inspectors

to supervise and enforce the mining code

on a full-time basis.

Inspectors were to be appointed by the

governor, and approved by

the Senate, only after they had been

certified as competent by a

Board of Examiners, composed of a state

geologist, two "practical

miners," one "practical mining

engineer," and one chemist chosen

by the governor. The bill empowered the

inspectors to enter the

mines to investigate their conditions.

It outlined the safety

responsibilities of the miners.

Inspectors finding violations were to

prosecute offenders by initiating civil

suits in the local courts.12

10. Direct, reliable evidence of the

ideology of rank-and-file workers is scarce. For

the above, use was made of the testimony

reprinted in Ohio, Mining Commission, 1871,

Report of the Mining Commission

Appointed under Joint Resolution . . .

(Columbus, 1872), 105-66; for the

provisions of the regulatory bill which the miners'

supported, see Ibid., 173-79.

Hereafter this source shall be cited as Report of the Mining

Commission.

11. The most recent study of the labor

and labor reform movements of the 1860s is

David Montgomery, Beyond Equality:

Labor and the Radical Republicans,

1862-1872 (New York, 1967).

12. Senate Bill 249 is reprinted in Report

of the Mining Commission, 173-79. Roy,

History of the Coal Miners, 112.

|

8 OHIO HISTORY |

|

Senator Michael Daugherty, representing the Hocking Valley introduced the bill which prompted immediate opposition from the state's coal operators. They designated a lobbying committee o thirteen members, representing every Ohio mining district, and employed an attorney to work against it. The operators' argumen was simple. The relative shallowness of Ohio mines meant that fou air was absent and methane not encountered. Whenever any problem arose in the mines, they asserted, the operators were fully capable o remedying it. The miners' bill, if enacted, would cause unnecessar expenses, threaten to close mines, and thwart development of th state's resources. State officials entering mines would b mischievous, their very presence prompting men to grumble an strike. Society was an organic unity whose every group relate naturally to every other group, but the miner's bill, "class' |

Coal Mine Safety 9

legislation, would upset the

time-honored social relationships of coal

communities while imposing unwarranted

expenses on taxpayers. The

proposal, in short, was nothing short

of the work of demagogues who

hoped to secure sinecures from it.13

Roy, believing that safer working

conditions would ease the

discontent of workers, had expected

many coal operators to accept

the bill's wisdom, but he was

frustrated in his lobbying effort. He told

the Senate about the British safety

efforts, described the various

dangers which miners faced, and

explained the minimum ventilation

and safety requirements which mining

experts of the day agreed

upon. "We want mine inspectors to

see that good and sufficient

ventilation is provided, and an

escapement shaft sunk for the

withdrawl of the mine in case of

accident to the main opening," he

noted. Ohio miners deserved the same

precautions taken in European

mines. We "are asking for nothing

but what is right," he concluded.

"We ask for a mouthful of fresh

air amidst the mephitic blasts of

death which surround us; and for a hole

to crawl out when the

hoisting shaft is closed up, as was the

case at the Avondale shaft a

year ago. ... "14

A Senate vote of eleven to sixteen on

April 12 killed the safety bill

for the 1871 session, but Roy and Lewis

did not return home

empty-handed. Senator Lauren D.

Woodworth, representing the

Mahoning Valley, introduced a resolution,

passed on May 2 by a

fourteen to thirteen vote in the

Senate, to establish a mining

commission to ascertain the conditions

of the state's mines and

recommend remedial legislation.15 The

three-member commission

was to include a "practical

miner" and a representative of the

operators. It was instructed "to

visit" and "inspect" the "leading

coal mines of the State" to

determine the facts concerning the

"health and safety" of

miners. Its second charge was "to inquire into

the causes of strikes among the miners

. . . and report the facts and

their conclusions .. ." and

recommend any needed legislation.16

Governor Rutherford B. Hayes chose

Charles Reemelin, a

prominent Cincinnati Democrat and

German-American leader who

had enjoyed a long career in state

politics, to head the commission.

13. Views of operators are summarized in

Roy,History of the Coal Miners, 113-14,

and are reprinted in Report of the

Mining Commission, 105-66.

14. Roy's History of the Coal Miners does

not report dates reliably, but it does

reprint his testimony to the Senate,

114-20. See also Youngstown Mahoning Register,

November 3, 1870.

15. Ohio, General Assembly, Senate, Journal

of the Senate of the State of Ohio,

59th General Assembly, April 12, 1871,

513-14; Ibid., May 2, 1871, 782.

16. The quotations are from the

resolution as reprinted in Report of the Mining

Commission,' 3.

10 OHIO HISTORY

Reemelin had invested in a Muskingum

County mining firm and,

though he claimed ignorance of mining,

Hayes chose him as an

industry representative. The Governor

also appointed Roy as the

group's "practical miner" and

Benjamin M. Skinner, a businessman

and Republican functionary from

coal-producing Meigs County.17

In the summer and autumn of 1871 the

commission traveled to the

state's leading coal fields and recorded

testimony from coal

operators, mine superintendents and

bosses, union leaders, and

ordinary miners. Roy inspected mines and

bitterly criticized his

colleagues for not doing so. Reemelin

studied mining reports from

Prussia. The three commissioners found

much at fault in the state's

mines, but could not agree on the

language to characterize them or,

more importantly, on the remedial

legislation required.

The majority report, clearly dominated

by Reemelin, expressed no

sense of alarm concerning safety and

health conditions in the mines.

"The shell of primitiveness is

sticking to every part of them," it

stated, "but the evidences of a

gradual improvement are also visible

everywhere." All mines could stand

some improvement but the only

ones "absolutely dangerous to

life" were those "with but one

opening." "The most numerous

causes of insecurity and

insalubriousness arise from . . . our western

mannerism, which

dislikes close regulations, and is

heedless of personal dangers."

Accidents were few and usually not

"dreadful," caused most often by

the carelessness of individual miners.18

Nor was there any particular cause for

alarm on the subject of

strikes. According to Reemelin and

Skinner, strikes arose from the

peculiar combination of the

circumstances of immigration and

industrial growth. Men came to Ohio to

mine coal from homelands

where "wealth held by

privileges" angered them; then in America

they were "surrounded by folks, who

grew rich without the

qualifications, which are usually

presumed to be requisite for

acquiring wealth." In the rapidly

changing economic scene the miners

"could discover no criterion by

which to measure the value of thei

own work"; they observed "the

operator whose wealth was, so far a

they could judge, an accident and not a

merit. .. ." Miners' wages

the majority found, were adequate; the

solution to their discontent lay

in saving, investing in real estate, and

rising into the capitalist class

17. Hayes to Reemelin, May 16, 1871,

Reemelin to Hayes, May 20, 1871, Hayes t

L. D. Woodworth, May 29, 1871, Woodworth

to Hayes, June 3, 1871, A. D. Fassel

and David Owens to Hayes, June 3, 1871,

The Papers of Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes Library. Charles

Reemelin, Life of Charles Reemeli,

(Cincinnati, 1892), 200.

18. Report of the Mining Commission,

7.

|

Coal Mine Safety 11 |

|

|

|

Strikes were a product in part of misperceptions leading to a determination to use force against the economic interests of the opposition; inevitably they harmed both capital and labor. The proper state policy was to rely on natural social 'evolution toward a realization that strikes did-more harm than good. "Children quit playing with edged tools when they find that they cut both ways," Reemelin and Skinner concluded; "why not hope that the children of labor will eschew strikes, when they have learned their, positively, injurious effects."19 Because the conditions of work and the social relations of the industry were no cause for special alarm, there was no need in the eyes of the majority for special laws dealing specifically with coal mining. Reemelin was prominent nationally for expressing an ideology of the organic nature of society. His views were rooted in the experience of the urban middle class with a regressive system of property taxation which was encountering pressures to support an expanding system of governmental services.20 The commission's recommendations for coal regulations fit into this circumstance. The state must avoid the costs of an inspection system. The miners' demands for state inspection stemmed from a misguided social understanding. They looked upon society as a collectivity of special

19. Ibid., 19-21. 20. Clifton K. Yearley, Jr., The Money Machines (Albany, 1970), 32-34. |

|

12 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

interests whereas, in Reemelin's view, it was properly understood as an organic unity. Thus the state must exercise great care to avoid legislation which treated only one segment of the population; even-handedness was the only proper course of action.21 The commission recommended three interrelated laws. The first defined the obligations of all employers to provide "wholesome air" in industries. The second codified common law by leaving damage payments to injured workers up to the results of civil suits. The third would have the state establish in each county a Sanitary Commission consisting of the Sheriff, the Surveyor, and two local physicians to regulate health and safety conditions in local industries.22 Thus the organic unity of society would remain intact in the application of law, control kept within local communities, and the costs of regulating health and safety conditions in industry would stay low. Andrew Roy disagreed entirely with these recommendations and used the opportunity of writing a minority report to explain carefully the need for state regulation and inspection. Knowing that most legislators were ignorant of the industry's details, he explained the various kinds of mine operations and their special problems. He reported the conditions he found upon inspecting numerous mines and concluded that "the majority are badly ventilated, and the smaller quite as badly as the leading mines." He reviewed the practices of European nations in mining education and regulation and urged legislation modeled after their experience. In deprecating the majority recommendations he asserted that laws "must be based upon the facts in the premises"; and the facts were clear, both fron the miners' testimony and from his inspections. The "majority" o

21. Report of the Mining Commission, 27-51. 22. Ibid., 169-73. |

Coal Mine Safety 13

miners were immigrants who knew that

even "despotic

governments" provided mining codes

and inspectors; they should not

expect less from their new democratic

homeland. Not only would

state regulation of the industry bring a

sense of greater justice to these

workers, it would also improve all

aspects of the industry, allowing

coal to be mined more economically, more

efficiently, and ultimately

more profitably. In the future an expert

state inspectorate could

resolve unforeseen problems with

recommendations based upon

careful, knowledgable observation and

experience. Roy urged the

legislature to enact a modified version

of the miners' bill.23

The mining commission finished its Report

in November, and

when the General Assembly convened in

Columbus for the 1872

session the two sides clashed again. Roy

and John Pollock, sent to

Columbus to work for the inspection

bill, were hopeful. There seemed

to be considerable public support for

their cause, and the Senate

enacted the bill unanimously on April

10. But the House of

Representatives balked, and by the end

of the month Roy and Pollock

were embittered.24

Leading the fight against inspection

were Charles Reemelin and

Joseph Conrad, mine operator and

Representative from Portage

County. Reemelin's three-part

recommendation had encountered

"derisive laughter" in the

Senate Committee on Mines and Mining

but in the House, according to Roy and

Pollock, "his labored theories

and blundering statements of facts were

accepted, by members who

had never seen a coal-mine, and who

believed that Reemelin had

really inspected the coal mines, in

accordance with his duties as State

Commissioner." The miners'

lobbyists were prepared to refute his

arguments, but were unable effectively

to counter Conrad's legislative

machinations. He arranged to have the

House strike out all the

provisions for inspection, the heart of

the Senate bill as far as the

miners were concerned. Pollock

admonished that "this is a question

of voting for capital, or human life. .

."25

When the conflicting bills went to a

conference committee, the

miners' lobbyists failed to obtain a

hearing. The House delegates,

which included two coal operators, were

intransigent on the question

of inspection. Friends in the

legislature urged Roy and Pollock to

accept a compromise mining code without

an inspectorate on the

23. Ibid., 55-96.

24. Ohio, Mining Commission, 1871, Report

of Messrs. Roy and Pollock, Miners'

Committee to Columbus, To Urge the

Passage by the Legislature, of the Miners'

Bill, for the Ventilation and

Inspection of Coal Mines (Cincinnati,

1872).

25. Report of Messrs. Roy and

Pollock; Columbus Ohio Statesman, April 22,

1872.

14 OHIO HISTORY

grounds that it established a desirable

legislative precedent. Though a

law was passed, the two men returned

home bitterly disappointed

with the failure to achieve inspection.26

"An Avondale disaster may

furnish an argument before another

winter," a sympathetic editorial

in The Ohio Statesman concluded.27

Less than three months later

the state witnessed its first mine

disaster which cost ten lives in

Portage County.28

Frustrated by the legislative process,

the miners saw their next

opportunity in the Constitutional

Convention which met in the

summer of 1873. There the miners' cause

was led by Martin F. Foran

of Cleveland, national president of the

Coopers' Union and later a

member of Congress. The miners sought to

have the constitution

contain a section which required the

General Assembly to enact laws

for the regulation and inspection of

mines. "We want . . . to put it

beyond the power of rich lobbyists to

defeat humanitarian projects . . .,"

exclaimed one supporter. Delegates

complained of the legislative

power of mine owners and sympathized

with the felt needs of miners.

With only six delegates voting against

including the section, the

convention responded favorably to the

miners' wishes.29

The voters defeated the new constitution

the following year, but

meanwhile the miners succeeded in

persuading the 1874 session of the

legislature to provide an inspector to

enforce the mining code. Roy

returned to Columbus in March. "The

legislature of Ohio this session

contains many farmers, or would-be

farmers," he wrote his

supporters. "Perhaps the granger

movement has suddenly converted

a politician into a farmer." He

found the new governor, William

Allen, "well-informed in coal

mining" and on mining legislation. "He

had read the reports of the . . .

English House[s] of Lords and

Commons of the monstrous abuses as

practiced on miners," he

noted.30 With a sympathetic

governor behind it, new member,

present in the legislature, and the

reality that a mine disaster had

occured in the state, the bill, amended

to provide for the single office

of State Mine Inspector, passed both

houses by wide margins.31 I

26. Report of Messrs. Roy and

Pollock.

27. The bill was passed on April 27,

1872.

28. Workingman's Advocate, July

13, 1872; Roy,History of the Coal Miners, 128

29. Ohio, Constitutional Convention,

1873-1874, Official Report of th,

Proceedings and Debates of the Third

Constitutional Convention of Ohi

(Cleveland, 1873), I, 345-47, II, 2869.

30. Workingman's Advocate, March

14, 1874.

31. Ohio, General Assembly, Senate, Journal

of the Senate of the State of Ohio

61st General Assembly, March 12, 1874,

332; Ohio, General Assembly, House o

Representatives, Journal of the House

of Representatives of the State of Ohio

61st General Assembly, March 5, 1874,

361-62. The statute is reprinted in Ohio

Inspector of Mines, First Annual

Report (Columbus, 1875), 84-88.

Coal Mine Safety 15

April 1874 Roy found himself appointed

State Inspector of Mines.

The new statute did not specify all that

Roy and his supporters had

sought. The miners had wanted a two-man

inspection force; they

obtained a single officer. This

reduction meant that Roy could not

possibly visit each of the state's three

hundred mines annually. The

miners had sought a procedure ensuring

that the inspectors were

chosen on merit and not on patronage

considerations, but the

procedures of certifying state

inspectors were stricken from the law.

Nor was there any provision for

government certification of mine

managers or, in Roy's view, adequate

educational facilities for

providing qualified men. These

inadequacies were to provide the

content of future dispute and

legislation.

Roy approached the administration of the

law in a judicious

fashion. He viewed his role as inspector

partly as that of an educator,

hoping that he could teach operators the

proper techniques of

ventilation and safety. He believed that

a helpful role would appeal to

their self-interest by showing how

miners working in a well-

ventilated, safe operation could produce

more coal and be less

inclined to strike. Failing gentle

persuasion, however, he did not

hesitate to take recalcitrant operators

to court for violations of the

mining code.32

Roy's enforcement policy and his close

association with the labor

and labor reform movements led to continuing

acrimony and

eventually cost him his job. In the 1876

session coal operators urged

the legislature to replace the

inspectorate with another office which

would combine geological surveying, the

gathering of mining

statistics, and wage arbitration with

the inspection function. The

miners rallied to Roy's support,

however; Governor Hayes was

assured of his engineering competence,

and the move to oust him died

for the time being.33

But when the Democrats recaptured control

of the statehouse,

Governor Richard M. Bishop in 1878

refused to reappoint Roy to a

second four-year term. Roy's Greenback

party affiliation provided a

ready excuse in an age of intense

partisanship, but it was probably

patronage considerations combined with

his policy of enforcing the

law which cost him the job. The miners

supported him for

32. Ohio, Inspector of Mines, First

Annual Report, 8-9; Idem, Second Annual

Report (Columbus, 1876), 30-31; NationalLabor Tribune, January

27, 1877.

33. National Labor Tribune, February

19, March 11, 1876; Miners' National

Record, II (February 1876), 57; Workingman's Advocate, April

1, 1876; John Siney,

William Thomson, and John James to

Hayes, February 23, 1876, and I. S. Newberry to

Hayes, March 20, 1876, Hayes Papers;

Ohio, Inspector of Mines, Fourth Annual

Report (Columbus, 1877), 164.

16 OHIO HISTORY

reappointment, but Bishop, after

studying Roy's use of the courts and

hearing the arguments of operators and

allied party officials, chose

James D. Poston of the Hocking Valley as

the second State Inspector of

Mines.34

Poston's appointment outraged Roy and

the miners. Poston seemed

to know little if anything about mine

safety and made no inspections

while in office. He refused to initiate

suits against operators who

violated the law, and at least one firm

whose mines had been closed

by Roy resumed operations two days after

Poston's appointment.

Poston left office in 1879 without

writing the Annual Report which

the law required.35

In 1880 Roy was reappointed by Governor

Charles Foster to

another four-year term and continued to

work for improvements in

state policy regarding mine safety. He

had a bill introduced in the

1882 legislature which would require all

inspectors and mine

managers to be certified as competent by

a board of examiners

appointed by the governor. Such

certification procedures were never

enacted during the nineteenth century,

but the legislature did provide

safeguards against the appointment of

patently inappropriate

inspectors in a code revision. This

response to the miners' outrage

over Poston's appointment provided that

any fifteen citizens upon

posting bond could require the

appointment of a board of examiners

to inquire into the competency of any

inspector and, if found wanting,

remove him.36 Meanwhile, in

1881 the state gave Roy an assistant,

and further expanded the staff of the

inspectorate in 1883.37

The vision expressed by Roy and his

supporters at the time of the

Avondale disaster of the state providing

education in mining

engineering began to come to fruition in

the 1880s also. In 1877 the

legislature had mandated a School of

Mines and Mine Engineering in

the Agricultural and Mechanical College

in Columbus (now The Ohio

State University). Although it allocated

$4,500 for equipment for the

program, it failed to provide funds for

staffing the faculty position.

34. National Labor Tribune, April

6, April 13, May 4, 1878. In 1878 Roy ran for

Secretary of State on the Greenback

ticket. Ohio, Secretary of State, Annual Report

of the Secretary of State for 1878 (Columbus, 1879), 196. John D. Martin to

Governor Richard M. Bishop, March 18,

1878, The Papers of Richard M. Bishop, Ohio

Historical Society.

35. NationalLabor Tribune, April 20, May 11, June 1, June 15, July 20, 1878; Ohio,

Inspector of Mines, "Fifth Annual

Report of the State Mine Inspector," in Ohio, Office

of the Governor, Ohio Executive

Documents, 1878, part II (Columbus, 1879),

1123-147.

36. Ohio, Inspector of Mines, Eighth

Annual Report (Columbus, 1882), 30-31.

37. Ohio, Inspector of Mines, Seventh

Annual Report (Columbus, 1882), 8; Idem,

Ninth Annual Report (Columbus, 1884), 129.

Coal Mine Safety 17

Consequently the Board of Trustees

voted to discontinue the

Department of Political Economy and

Civil Polity in order to release

funds for a professor of mine

engineering. Adequate appropriations

remained a problem for the next decade.

In 1887 Andrew Roy and a

group from the Ohio Institute of Mining

Engineering worked with

trustee Rutherford B. Hayes and the

legislature to insure funding for a

three-man department offering a regular

four-year engineering course,

a special two-year course which hoped

to attract "practical miners,"

and independent studies.38

By some measures this movement to

install a state safety program

for coal mining was successful; by

others it was not. One standard

used to point to the success of

inspection involved a favorable

comparison of the number of tons mined,

the number of men

employed, and the number of deaths and

serious injuries which

occured each year.39 Though

the rates of serious injury and death

may have gone down, however, the

state's mines did not become safe

places in which to work. In 1881 the

state witnessed its first deadly

explosion of methane.40 Roy's

successors, Chief Inspectors Thomas

Bancroft and R. M. Hazeltine, were

confident that their policy of

educating mine managers short of

initiating court suits was bringing

safer mines. After he retired from

public office, Roy complained that

not enough had been done.41 A

century after the 1874 inspection law,

however, the achievement of healthy and

safe working conditions

underground continues to elude

scientists, engineers, miners, and

public officials alike.42

Clearly in the 1870s, however, the

miners' agitation over unsafe

and unhealthy working conditions was

breaking ground for erecting

what was to become in the next century

an elaborate structure of

government intervention into the

affairs of private business firms.

They established a precedent the end

result of which was a broad

public consensus on the propriety of

such state regulation. Their

actions, moreover, hold significance

for a historical understanding of

the Gilded Age. Older conceptions of

the period as a time of

laissez-faire, as a period of

inhumanity on the part of businessmen

and the public officials they allegedly

controlled, and as an age of the

38. Alexis Cope,History of The Ohio

State University (Columbus, 1920), I, 49-52.

39. Ohio, Inspector of Mines, Sixth

Annual Report (Columbus, 1881), 4.

40. Idem, Seventh Annual Report, 17.

41. Andrew Roy, "The Protection of

Miners," Ohio Mining Journal, XXIV (1895),

50-54.

42. For an analysis of the continuing

safety problems, see Curtis Seltzer, "The

Unions-How Much Can a Good Man Do,"

The Washington Monthly, VI (June,

1974), 7-24.

18 OHIO HISTORY

powerlessness of labor have been

revised recently. Some writers have

suggested that the humanitarian

impulses which supported the

anti-slavery movement were transfered,

in part, after the Civil War to

promote public policies of ameliorating

the conditions of life in

factories and cities.43 Other scholars have pointed

out that as the

nation's economic system was undergoing

rapid industrial

reorganization, persons whose lives

were rooted in local community

structures and local socio-economic

patterns frequently behaved in

ways sympathetic toward the workers who

bore the psychological

and economic brunt of industrialism.44

The story of the mine safety

movement in Ohio fits into this larger

pattern of reinterpretation. The

miners showed an early tendency toward

union organization based on

perceptions of social stratification

and, most important, gave

evidence of considerable political

power in the age of the "robber

barons." For historical insight

the lasting significance of this

particular story rests on the

proposition that ordinary workers willing

to agitate, able to organize, and

recruiting capable leaders could make

their weight felt on the political

system of the time. The success of

their efforts, in the final analysis,

is a tribute to them.

43. David Montgomery, "Radical

Republicanism in Pennsylvania, 1866-1873,"

Pennsylvania Magazine of History and

Biography, LXXXV (October, 1961),

439-57; James C. Mohr, The Radical

Republicans and Reform in New York During

Reconstruction (Ithaca, 1973). See also Sidney Fine, Laizzez-Faire

and the

General-Welfare State (Ann Arbor, 1956). In the research for this essay we

made no

effort to identify "radical"

Republicans and to measure their influence on the

legislative outcome. State inspection

did receive the support of Republican Governors

Hayes and Charles Foster, Democratic

Governor William Allen, though not Democratic

Governor Richard M. Bishop.

44. Herbert Gutman, "The Workers'

Search for Power," The Gilded Age, ed. H.

Wayne Morgan (Syracuse, 1970), 31-54.

K. AUSTIN KERR

The Movement for Coal Mine Safety

in Nineteenth-Century Ohio

In the nineteenth century Ohioans, as

other Americans, faced a host

of new situations arising from the

industrial revolution. As the level of

industrial production increased, unique

forms of occupational

organization emerged which often

confronted workers or the public with

unaccustomed hazards, creating demands

that government begin

regulating the affairs of private

industry. By the 1860s state government

began addressing the special dangers in

the railroad and coal mining

businesses, two industries which were

essential in the burgeoning

economy. The growth of coal mining

brought peculiar dangers new to

miners in America.

During the winter of 1869-1870 miners

began agitating for state

enactment and enforcement of mining

regulations. Their initiatives

questioned prevailing ideologies

concerning the proper relationship

between the government and the

governed. The legislature in 1871

designated a Mining Commission to

investigate the working condi-

tions of the state's mines, and enacted

a statute in 1872 defining

health and safety standards in the

growing industry. In 1874 it

provided the first bureaucratic and

professional means of enforcing

the mining code by creating the post of

State Inspector of Mines. In

1882 it designed a means of insuring

that the Inspector and his

assistants were qualified persons, and

subsequently in the decade,

along with the Board of Trustees of

what was to become The Ohio

State University, funded an active

Department of Mines to provide

the educational basis for achieving

mine safety. Behind this

century-old legislative outline lay a

controversy which revealed the

origins of government

"welfare" policies, the beginnings of a struggle

which lasted at least through the 1930s

to have the state and federal

government assume responsibility for

improving the conditions of

work in the industrial age.

The story of the beginnings of coal

mine health and safety

Dr. Kerr, Associate Professor of History

at The Ohio State University, received

research assistance for this article

from Susan Busey, Michael J. Fitsko, Gerald Huss,

Michael R. McCormick, and Daniel

Schneider.

(614) 297-2300