Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

STEVEN P. GIETSCHIER

The 1951 Speaker's Rule

at Ohio State

Like many public institutions of higher

learning, The Ohio State

University's support for the principles

of academic freedom has often

been limited by the political and social

views of those who have shaped

its destiny. Because of the university's

location in the state capital,

and certainly because of its dependence

upon a penurious General

Assembly for funding, Ohio State has,

over the years, generally re-

flected its origins as a land grant

institution. In the spirit of the Mor-

rill Act, the University has tended to

emphasize the practical arts over

the humanities and to cultivate a

functional and, when necessary,

patriotic approach to education. As

early as 1883, the Ohio State

Board of Trustees dismissed the

University's president, Walter Scott,

because "he promulgated unsound and

dangerous doctrines of politi-

cal economy," including the Henry

Georgian ideas that "capital was

robbery," and "dividends were

theft." In the ensuing years, however,

such spectacular incidents were few.l

After World War II, the Ohio State

administration responded to the

anxieties of the Cold War with a series

of policy decisions restricting

the exercise of academic freedom. Led by

its Board of Trustees and

by President Howard Bevis, the

University passed a series of resolu-

tions to regulate political discussion

on campus, the appearance of

outside speakers, and the right of

faculty members to discuss con-

troversial subjects in the classroom.

Overall, these measures demon-

strated the Trustees' decision that the

unrestrained exchange of ideas

must be partially curtailed in the

interests of national security.

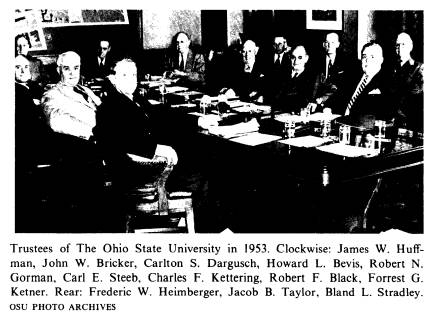

Given the Board's composition, its

accommodation to the Cold War

ethos was hardly surprising. During

these years the Trustees were led

by Brigadier General Carlton Dargusch,

the former Deputy Director of

Selective Service, and by Senator John

Bricker, a conservative Repub-

Steven P. Gietschier is Director of the

Ohio Labor History Project at the Ohio His-

torical Society.

1. Alexis Cope, 1870-1910, ed. T.

C. Mendenhall, Vol. 1 of History of The Ohio State

University (9 vols., Columbus, 1920-1976), 79. For a wider

discussion of higher educa-

tion's sensitivity to public pressure,

see Richard Hofstadter, Anti-intellectualism in

American Life (New York, 1963), Chapters 12-14.

OSU Speaker's Rule

295

lican and supporter of Senator Joseph

McCarthy. Other board mem-

bers, all of whom were appointed by

Ohio's governor, included Charles

Kettering, the General Motors research

genius, Forrest Ketner, an

agricultural association executive, and

Robert Black, president of

Cleveland's White Motor Corporation. The

University was firmly

governed by a group of conservative

politicians and industrialists.

As early as December 1946, Senator

Bricker had accused the Univer-

sity of harboring communists. This

charge led to an investigation of

campus groups for leftist ties and to

the introduction of a University

loyalty oath. The trustees of the Ohio

Historical Society, which occupied

a building on the campus, dismissed one

employee of the museum for

disloyalty.2 At the same

time, the University Trustees decided to forbid

the use of campus facilities to all

candidates for public office and later,

to their surrogates. When the Board

first passed this resolution, on

April 22, 1946, its announced purpose

was to prevent the overcrowding

of an already crowded postwar campus.3

In fact, the 1946 rule was

simply the formalization of an existing,

de facto policy. That the Board

had something more in mind than the

over-utilization of facilities was

evident in its passage of a follow-up

resolution in 1947. This time, on a

motion by General Dargusch, the Trustees

warned the teaching staff

that, although it was their right to

teach objectively in controversial

areas, they were required to maintain

"complete impartiality of opinion

in class room discussion."4

Protests against these resolutions arose

intermittently, especially

when their provisions seemed to be enforced

unequally. Paul Robeson

and Henry Wallace were both barred

during the 1948 presidential cam-

paign, although Norman Thomas was

allowed to speak, as were two

Republican officials, Senator Wayne

Morse (Ore.) and Congressman

John Vorys (Ohio). Petitions by faculty

members, students, and the

student newspaper, The Lantern, led

to the rule's reconsideration, but

the Board re-affirmed and expanded its

stance to include all campus

political meetings, even if no candidate

were set to appear. Only in

1950 did the Board amend its rules to

permit one campus meeting per

party per year, an opportunity only the

Republicans chose to utilize.5

This was the situation in 1951 when the

Representative Assembly of

Graduate Students in Education organized

the sixth Boyd H. Bode

2. James E. Pollard, The Bevis

Administration, 1940-1956, Part 2, The Post-War

Years and the Emergence of the

Greater University, 1945-1956, Vol.

VIII of History of

The Ohio State University, 158-60.

3. Ohio State University, Board of

Trustees, Record of Proceedings of the Board of

Trustees of The Ohio State

University, April 22, 1946 (Columbus,

1946), 310.

4. Pollard, Bevis, 126-29.

Trustees, Proceedings, January 6, 1947, 275-76.

5. Trustees, Proceedings, May 10,

1948, 308, and July 7, 1950, 42-43.

296 OHIO HISTORY

Conference on Education, an annual

convocation in honor of a promi-

nent emeritus professor of education at

Ohio State. To address the con-

ference on the theme, "Frontiers in

Educational Theory," the Bode Con-

ference Committee invited Harold Rugg, a

retired education professor

at Columbia University. Rugg's three

appearances, on July 10 and 11,

consisted of two lectures and a

question-and-answer session and threw

the campus community into unprecedented

turmoil. A nationally

prominent, progressive educator and an

intellectual compatriot of John

Dewey, Rugg was the author of numerous

textbooks, many of which

had been subsequently dropped by various

school systems for being too

"leftist." In addition, Rugg

had become a frequent target of Allen Zoll,

whose chosen profession was to alert

America to dangerous books and

subversive individuals. Zoll at various

times headed organizations called

the National Council for American

Education, the Conference of Ameri-

can Small Business Organizations, and

American Patriots, Inc., the

last of these having itself been

labelled as subversive by the Attorney-

General.6

Although Rugg's appearance on the OSU

campus became a matter

of great controversy and bitterness, not

much attention was paid to what

he actually had said. His remarks were

neither recorded nor taken down

by a stenographer. What remains today of

the three sessions are a very

sketchy set of notes of unknown origin

and the contemporaneous rec-

ollections of several students who were

present. In addition, there

exists a transcript of a radio interview

given by Rugg at Ohio State on

July 15. Taken together, these sources

give a varied and choppy account

of Rugg's addresses. He seems to have

focused on two points: first,

that the postwar world, with its

increasing complexities, demanded a

new effort from the schools to use

history to teach about current prob-

lems, and second, that a new social

order was possible through the

application of new, advanced knowledge

of human behavior. Clearly,

Rugg was not satisfied with the way

schools were studying contem-

porary problems. More often than not, he

said, the fault lay with parents

who simply did not understand what their

schools were trying to

accomplish. He explained on the radio:

I think one of the tragic lags in our

society is the lag of understanding of the

parents and the citizens generally of

what the newer schools are trying to do in

6. Pollard, Bevis, 140. Edward N.

Saveth, "What to Do About 'Dangerous' Text-

books," Commentary (January

1952), 100. Vinton McVicker, "Is OSU Heading for An-

other Witch Hunt?" Cleveland

Press, July 21, 1951. "What's Really Back of OSU Gag

Rule?" (editorial), Ibid., September

15, 1951. [The Bevis Papers at Ohio State (see

note 7) are a particularly rich source

of newspaper clippings, but most of these do not

include the page number. I have

endeavored to include headlines, article titles, and

correspondents' names in these footnotes

because the newspapers were active partici-

pants in the events described, and their

contributions should be fully referenced.]

OSU Speaker's Rule

297

our times. There has been a great gap.

And I think it is partly caused by the fact

that while we've been trying to learn how to build a

good school, we have not,

perhaps, given enough energy to bringing

parents in on it.

Then, in what was soon regarded as his

most outrageous utterance,

Rugg argued that his hopes for America

and its schools were not being

realized, and he suggested that another

depression would be necessary

to awaken people to the real need for

further social and economic

change.7

The ammunition for what was soon to be

known as the "Rugg con-

troversy" was probably supplied by

Colonel William Warner, executive

director of Ohio Civil Defense, on leave

from his position as Professor

of Industrial Arts Education at Ohio

State. Warner's reputation as a

scholar and educator was questionable.

One former OSU professor

noted that colleagues dubbed him

"The Professor of Whittling." Others

have remembered that he was once called

on the carpet for repeatedly

refusing to allow members of a graduate

committee to read his students'

dissertations and that he probably did

not get a pay raise during the

whole postwar era.8 Perhaps

Warner felt more accomplished in his

self-appointed role as Ohio State's

resident Red hunter, an avocation

which occupied much of his time both

before and after his appointment

as Ohio's Civil Defense chief. There is

no direct evidence linking War-

ner with either Allen Zoll or with the

Wolfe family, prominent in Co-

lumbus business and politics. The Wolfes

published the two newspapers,

the Columbus Dispatch and the Ohio

State Journal, whose editorial

policies fueled the Rugg controversy's

flames. Nevertheless, these

connections received wide credence on

campus. In fact, Warner was the

frequent antagonist of H. Gordon

Hullfish, the Education professor who

served as adviser to the Bode committee

and was partly responsible for

the invitation to Rugg. Moreover,

simultaneous with the September

meeting of the Board of Trustees at

which the Rugg matter was consid-

ered, Warner had arranged a special

anti-communist program at the

7. Notes, Box 45, File: Rugg . . .

Correspondence, L-R, The Papers of Howard L.

Bevis, RG 3/h, The Ohio State University

Archives, Columbus (hereafter cited as Bevis

Papers). Statements of Students, Box 45,

File: Prof. Rugg, Official Correspondence

. . ., Bevis Papers. Radio Transcript,

July 15, 1951, Box 37, File: Rugg, Harold O.

(1st of 2), The Papers of the College of

Education, Office of the Dean, RG 16/a, The

Ohio State University Archives.

8. "War Against the Schools"

(editorial), Akron Beacon Journal, September 11,

1951. Letter to author from Dudley Williams,

former Physics professor, Ohio State,

April 9, 1975. Interview with Harold

Fawcett, former Education professor, Ohio State,

April 4, 1975. Letter to author from

Harvey Mansfield, Sr., former Political Science

professor, Ohio State, April 8, 1975. I

solicited the opinions, by questionnaire and letter,

from a number of professors and

administrators who played prominent roles in these

controversies. Generally, the persons I

chose to contact were members of faculty com-

mittees which became involved in the

Rugg controversy.

298 OHIO HISTORY

Columbus Rotary Club. Without the

consent of any other members of

the program committee, Warner

substituted reporter Frank Hughes for

the previously scheduled speaker.

Hughes, who worked for the Chicago

Tribune, spoke about leftist propaganda in American schools,

centering

his criticism on the Citizenship

Education Project, sponsored by

Teachers' College at Columbia

University.9

Without a doubt, the two conservative

Columbus newspapers, the

Dispatch and the Journal, were ready to make Rugg's

campus appear-

ance a cause celebre. Professor

Hullfish, in his introductory remarks

before Rugg's speech of July 10,

referred to the controversy already

present on the campus. On the next day,

Rugg himself displayed the

news clippings about the first talk.10

These stories focused, not sur-

prisingly, on his call for a new

depression. The Dispatch quoted Rugg

as saying, "I hope for a

depression, but I don't think it will materialize

in the near future. Only under the

stress and strain of nationwide unem-

ployment can the people be brought up

short to ask why." In addition,

these newspapers noted that Rugg had

predicted an increase in the

extent of the public control of

production. They also made sure to show

the alleged intellectual connection

between the controversial Rugg and

the faculty in the College of

Education.11 By way of contrast, the other

Columbus daily, the Citizen, covered

only the second day of the Bode Con-

ference. Its story included Rugg's

prediction of increased public control

of the economy, but it also quoted

Hullfish on his sharp philosophical

differences with Rugg.12

Much more vituperative and accusatory

than these news stories was

the flurry of editorials and letters to

the editor which followed in the

aftermath of the Rugg visit. These items

detailed the two-fold case

against Harold Rugg: first, that Rugg

himself was a socialist or perhaps

a communist and certainly unfit to

address a college audience; second,

that Rugg's invitation could be

attributed to a conspiracy within the

College of Education, which influenced

the Bode committee to invite

him to indoctrinate the future teachers

of Ohio's youth. The Journal

9. Letter to author from Harold Burtt,

former Psychology professor, Ohio State,

April 3, 1975. Letter to author from

Grant Stahly, former Microbiology professor,

Ohio State, March 25, 1975. Interview

with Harold Fawcett. Lowell Bridwell, "Warner

Acted Alone in Blast on Educators,"

Columbus Citizen, September 13, 1951. Memo,

William Warner to Rotary Club, September

10, 1951, Box 37, File: Rugg, Harold O.

(lst of 2), Education Papers.

"Rotary Told of Leftist School Cult," Citizen, Septem-

ber 10, 1951.

10. Notes, Box 45, File: Rugg . . .

Correspondence, L-R, Bevis Papers.

11. Dean Jauchius, "Educator Tells

OSU Meeting He's Hoping for Depression,"

Columbus Dispatch, July 11, 1951. "Dr. Rugg Cites Two Teacher

Problems," Ohio

State Journal, July 12, 1951. Jauchius, "Rugg Is Praised by OSU

Dean As Campus

Conference Ends," Dispatch, July

12, 1951.

12. "TVA Exemplifies American Way

of Life, Rugg Asserts," Citizen, July 12, 1951.

OSU Speaker's Rule 299

seethed editorially that public funds

had been expended to bring to

OSU "the Marxian doctrinaire of

school textbook fame," and the Dis-

patch complained that "people who will teach hundreds of

thousands

of Ohio youngsters in the years to come

are being indoctrinated with

the subversive political ideas advocated

by a notorious and discredited

propagandist .. .."13 Those persons

who accused the College of

Education of harboring a "Rugg

cult," dedicated to furthering his ideas,

demanded an investigation of the college

by the newly-created Ohio

Un-American Activities Commission. That

the evidence of this con-

spiracy would be hard to uncover, as the

often anonymous accusers

admitted, was simply proof of its

sinister existence.14

Rumors and suspicions persisted that

Colonel Warner had master-

minded the entire anti-Rugg campaign and

that he was responsible for

the anonymous letters and the editorials.

Certainly, this was the opinion

held by many OSU faculty members. There

is no hard evidence con-

necting Warner with the effort to

besmirch Rugg and to discredit the

College of Education. Yet, a careful

examination of the entire episode

leaves the inescapable conclusion that

someone did engineer the whole

effort. The letters to the editor of the

Journal began appearing on July

11, only one day after the Bode

Conference. These writers had to be

aware of Rugg's reputation from some

outside source since the only

news story announcing Rugg's invitation

was a very simple, non-in-

flammatory publicity release in the Journal

of July 4. Then too, the

flood of editorials and letters to the

editor overpowered by far the

limited news coverage given to Rugg and

strongly suggests the influ-

ence of especially interested persons.15

University President Howard Bevis at

first responded to the

charges against Rugg and Ohio State by

appealing to the tradition of

academic freedom, asserting that the

University must allow a wide

latitude of expression. In late July,

Bevis elucidated his position fur-

ther and implicitly refuted the charge

of a conspiracy within the Educa-

tion faculty. In a letter to a member of

the Board of Trustees, Bevis

wrote that the Bode Conference had been

organized by graduate stu-

dents, that Hullfish had played an

advisory role only, and that Rugg

13. "Dr. Rugg and His New Social

Order" (editorial), Journal, July 28, 1951.

"Campus Probe in Order"

(editorial), Dispatch, July 17, 1951.

14. "Investigation Called For"

(editorial), Journal, July 16, 1951. "Rugg Episode

Calls for Thorough Stock Taking"

(editorial), Journal, August 31, 1951. Anonymous

letter to editor, Dispatch, July

15, 1951. "Of All People, Why Rugg?" (editorial),

Journal, July 11, 1951.

15. Letter to author from Paul Varg,

former History professor, Ohio State, April 11,

1975. Letter from Dudley Williams.

Letters to editor, Journal, July 11, 1951. "Educa-

tors Set OSU Conference," Journal,

July 4, 1951. For a summary of the case support-

ing collusion, see Ohio C.I.O. Council, Keep

Them Free (Columbus, n.d.).

|

300 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

had been invited because the graduate student committee had selected him. Bevis added that he thought the invitation showed poor judgment and that he disagreed with much of what Rugg supposedly had said, but, "within the bounds of loyalty to the Government, considerable latitude of expression must be allowed on a university campus."16 If the attack upon Rugg's appearance had included nothing more than the virulent reactions published in the Columbus newspapers, President Bevis' public stand might well have ended the incident. But the Board of Trustees and Governor Frank Lausche also took a strong interest in the Rugg invitation, and their concern kept the controversy alive. Once the governor got involved, Bevis and the Board were quick to announce an investigation of the entire matter. As Bevis now explained to General Dargusch, the new Chairman of the Board of Trustees, the invitation to Harold Rugg was "a minor issue. The underlying and major issue is the curricular content and teaching approach in courses given to prospective teachers. ... It concerns, as I sense it, the economic, social, and political predilections, if any, which manifest themselves in the courses and the teaching."17 16. Jauchius, "Rugg Is Praised." Bevis to Robert Black (copy), July 23, 1951, Box 45, File: Prof. Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis Papers. 17. Benjamin Fine, "Education in Review: Issue of Academic Freedom Is Raised Again, This Time at Ohio State University," New York Times, October 28, 1951. "OSU's Trustees Plan Rugg Probe," Journal, July 19, 1951. Bevis to Dargusch, July 21, 1951, Box 45, File: Prof. Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis Papers. |

OSU Speaker's Rule

301

Yet the result of this investigation,

which took better than a month

to conclude, had very little to do with

curricular content and teaching

approach. Instead, at the September

meeting of the Board at Gibraltar

Island, Ohio, the Trustees passed a

resolution commanding the Presi-

dent to establish procedures,

"under which all proposed invitations to

speakers appearing on the University

campus or under University

auspices, shall be submitted to his

office for clearance ten days prior to

the extension of the actual invitation

by the individual, department or

College concerned." This

resolution, which came to be known as the

Speaker's Rule, was accompanied by a

statement in which the Board

condemned the Rugg invitation as

"not in accord with the traditions

and objectives of the Ohio State

University. . . . The function of a

University," the statement

concluded, "is teaching, not indoctrination.

The University must not be used as an

agency of un-American propa-

ganda."18 Thus it was

that the original concern of President Bevis for

preserving the widest latitude in

matters of free speech on campus was

subordinated to the Board's desire to

insulate the University from indoc-

trination and propaganda, the presence

of which was to be determined

by the president.19

The furor set off by the announcement of

this policy far surpassed the

original uproar over Rugg's appearance.

The sustained outburst of

opposition caught Bevis and the Board

completely by surprise. The

controversy over academic freedom which

the Board had sought to

stifle mushroomed as protests to the

resolution, now dubbed the "gag

rule," rose from inside and outside

the campus.20 In addition, the imple-

mentation of the rule by the President

soon became both an intolerable

administrative burden and a severe

interference with the normal course

of education on the campus. Critics of

the rule, including faculty mem-

bers, church leaders, civic and

professional groups, and private citizens,

accused the Board of repressing freedom

in the name of defending it.

They argued that the issues at stake in

the country at large could be met

only by discussing them openly, and they

rejected the Trustees' implicit

assumption that college students could

not grapple successfully with

controversial ideas. Perhaps the most

strident objection to the rule

came from the Cleveland Press:

18. Minutes, Board of Trustees,

September 4, 1951, typed copy, Box 45, File: Prof.

Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis

Papers. "Campus Speakers: President Must

Clear Them," Ohio State

University Monthly, XLIII (October 15, 1951), 5.

19. It would be foolish to assume that

each member of the Board of Trustees re-

acted exactly the same to the Rugg

crisis, but the Board always met in secret, published

abbreviated proceedings, and spoke in

public with one voice.

20. Letter to author from Robert Patton,

former Economics professor, Ohio State,

March 28, 1975.

302 OHIO

HISTORY

In their [the Board's] apparent

determination to play star chamber censors

to a great public education institution,

they ignored the earnest wishes of most

of the faculty. . . . The greatest

danger, of course, is the strong possibility

that these first tragic repressions will

snowball. When you start monkeying

with people's freedom to think and act,

you get intellectual zombies in a

terrible hurry. Everybody votes Ja.21

Although many faculty members made known

their opposition to the

rule as soon as it was announced, the

full extent of faculty disapproval

did not emerge until Bevis began to

implement its provisions. Initially,

when debate over the rule was still just

a matter of principle (because

classes were in recess until the end of

September), protest seems to

have come most frequently from the

Colleges of Arts and Sciences,

Education, and Law. Soon, though, these

faculty members were joined

by other colleagues as the full burden

of the rule was realized. As imple-

mented by President Bevis, the rule

called for every sponsor of every

invited speaker to fill out and file

with the President a detailed ques-

tionnaire prior to the issuance of any

invitation. This form included

spaces to list the sponsoring

organization, describe the character of the

meeting, and supply biographical data on

the proposed speaker as well

as "any pertinent information

affecting the desireability of his appear-

ance as a speaker on the campus."

Each form had then to be co-signed

by the appropriate dean and filed ten

days in advance of the proposed

22

appearance.

It soon became apparent that the

speaker's rule was an administra-

tive and intellectual nightmare. In the

three weeks after the rule's

adoption, Bevis had to rule on 138

separate requests, each one demand-

ing, in effect, its own security

investigation. This process was not only

a physical impossibility, but required

the President to rule on the fit-

ness of individuals about whom he often

knew very little. In addition,

there were several activities scheduled

at the University, such as the

annual Institute for Education by

Radio-Television and the opening of

new health education and medical

facilities which, with their huge num-

ber of participants, put an intolerable

strain on this haphazardly con-

structed system.23 More

serious than this bureaucratic problem was the

21. "Gag at Ohio State"

(editorial), Toledo Blade, n.d.; "Let Us Hear" (editorial),

Ohio State Lantern, n.d.; Letter of Walter McCaslin, Jr., to editor, Ohio

State Univer-

sity Monthly; "Book Burning Next?" (editorial), Cleveland

Press, n.d., all in Ohio State

University Monthly, XLIII (November 15, 1951), 8, 9, 10, 15. There are

several files

of correspondence and reactions to the

rule in Boxes 45 and 46 of the Bevis Papers.

22. Letter to author from Robert Patton.

Letter to author from Harold Burtt. Sam-

ple questionnaire; Bevis to Dean Donald

Cottrell, College of Education (copy), Sep-

tember 24, 1951, both in Box 45, File:

Prof. Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis

Papers.

23. "Campus Speakers," 5.

Interview with Harold Fawcett. I. Keith Tyler, Director,

Office of Radio Communication, to Bevis,

October 10, 1951, Box 47, File: Speaker

OSU Speaker's Rule

303

startling decision by groups and

individuals alike to avoid coming to

Columbus or, in the case of Ohio State

faculty, to rescind invitations

rather than subject guests to the new

rule. The American Physical

Society moved its 1952 meeting of some

eight hundred physicists from

Columbus to Chicago, and the Art Section

of the Ohio Education

Association switched its conference to

Canton. One prospective

speaker, a psychologist, explained quite

clearly why he would not sub-

mit to the screening process. An

unfavorable report would be highly

undesirable, he argued, but even a

satisfactory clearance would tie him

to the views of the Board, with which he

disagreed.24

The speaker's rule did far more than

cause bureaucratic inconven-

ience and a decrease in the number of

guest speakers on campus. When

Bevis declined to approve a proposed

speaker, the inescapable

implication was that the individual was

subversive. This was exactly

the case when Bevis refused to allow Dr.

Cecil Hinshaw, a Quaker and

a pacifist, to address the student

chapter of the Fellowship of Recon-

ciliation. Hinshaw's record bore no

trace of subversion, and he was in

fact staunchly anti-communist, but

Bevis' negative decision reflected

adversely on Hinshaw's reputation.25

The rule could be as damaging as

its most vocal critics feared. When

Bevis consistently refused to reveal

his reasons for banning Hinshaw, other

invitations to him were can-

celled, and his reputation was injured.

Bevis' silence on the matter soon

became an issue in itself. Hinshaw's

repeated requests that Bevis

explain the ban went unfulfilled, and

Hinshaw left Columbus unsatis-

fied and vexed. Privately, Bevis argued

that neither Hinshaw's pacifism

nor his Quakerism had caused the ban;

instead, Bevis objected to Hin-

shaw's public insistence on his right to

counsel men to violate the draft

law. The Ohio State president believed

that such a position, if ex-

pressed on campus, could have subjected

the University to legal dif-

ficulties.26

Faced with a barrage of criticism during

the first weeks of the rule's

application, President Bevis made an

administrative adjustment to

Rule Clearances, Bevis Papers. Dean

Charles Doan, College of Medicine, to Bevis,

October 11, 1951, Box 45, File: Prof.

Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis Papers.

24. "Screening Rule: Issue Becomes

National," Ohio State University Monthly,

XLIII (November 15, 1951), 6-7. Manuel

Barkan, Professor of Fine Arts, to Bevis,

November 2, 1951; Oscar Adams, Professor

of Psychology, to Bevis, November 7,

1951, both in Box 45, File: Rugg . . .

Correspondence, A-D, Bevis Papers.

25. Hinshaw request, n.d.; Bevis to

Wilbur Held, faculty adviser, Fellowship of Re-

conciliation (copy), September 29, 1951,

both in Box 45, File: Rugg . . . Correspon-

dence, E-K, Bevis Papers. Jack Fullen,

"Letter from Home: Background On Screen-

ing," Ohio State University

Monthly, XLIII (November 15, 1951), 1.

26. Citizen, October 5, 1951.

Hinshaw letter to editor, Citizen, October 22, 1951.

Bevis to William Greeley (copy), January

1, 1952, Box 45, File: Rugg . . . Corres-

pondence, E-K, Bevis Papers.

304 OHIO HISTORY

reduce his own staffs investigatory

responsibilities. This change re-

quired faculty to supply more

biographical information on potential

speakers. But the Board, Bevis, and the

governor all stood firm in

defense of the basic policy. General

Dargusch argued that the rule had

nothing to do with academic freedom, but

was merely a way to prevent

Ohio State from being used by

"those who would subvert our people

and destroy our institutions by force or

other unconstitutional means or

to those who lend aid, comfort and

assistance to such persons." Senator

Bricker agreed with Dargusch, and

Governor Lausche, in part responsi-

ble for the Trustees' initial concern

over Rugg, refused to tamper with

the rule. He asserted simply that

"someone has to assume the respon-

sibility of seeing to it that those who

want to overthrow our Government

are not allowed to speak at the

university."27

Faculty opposition to the speaker's rule

was at first sporadic, disor-

ganized, and limited to certain

departments.28 But, as more faculty

members came to see that the rule would

hamper their own activities

and would not be confined to the rooting

out of "subversives," the

faculty began to organize opposition to

the Trustees' position. The

Planning Committee of the Faculty of the

College of Education called

a meeting of the entire Education

faculty at which a resolution was

passed expressing concern that the Board

had infringed upon the

traditional principle of faculty

responsibility for academic freedom. The

resolution urged the Faculty Council and

the Conference Committee of

the Teaching Staff to seek redress of

this grievance.29

As these two faculty groups began to

consider how best to deal with

the crisis, at least one member of the

Board suggested to Bevis that the

rule needed further interpretation and

clarification.30 Simultaneously,

Academic Affairs Vice-President Frederic

Heimberger recommended

to Bevis a list of faculty members who

could be called upon to work

out a modus vivendi with the

Trustees. These two developments were

without doubt inspired in part by the

growing array of faculty oppo-

sition. At the same time, the Trustees

may well have been influenced

by the moderation of both the Faculty

Council and the Conference

Committee. Neither body demanded a

completely unrestricted

27. "Campus Speakers," 5.

Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1951. Citizen, Oc-

tober 4, 16, 1951.

28. For an example of faculty support of

the rule, see J. F. Haskins, Professor of

Physics, to Bevis, n.d., Box 45, File:

Prof. Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis Papers.

29. Memo, Planning Committee, College of

Education, to Education Faculty, Sep-

tember 27, 1951, Box 37, File: Rugg . .

. Correspondence . . . (confidential), Educa-

tion Papers. Education Faculty

resolution, October 2, 1951, Box 45, File: Prof. Rugg,

Official Correspondence, Bevis Papers.

30. Robert Gorman to Bevis, October 11,

1951, Box 45, File: Rugg . . .Correspon-

dence, E-K, Bevis Papers.

OSU Speaker's Rule

305

approach to the speaker question. The

resolution passed by both

groups admitted that fundamental

freedoms were subject to abuse and

that indoctrination could be a problem.

But the faculty felt aggrieved

that the Board of Trustees had not

demonstrated enough confidence in

them to let them handle the situation,

as they had in the past. Their

resolution, moreover, attacked the new

rule's bureaucratic require-

ments which virtually ruled out the

appearance of any speaker on short

notice.31

The faculty-passed resolution

established a basis for compromise

between the existing Speaker's Rule and

no rule at all. Even before the

Faculty Council approved the resolution

on October 9, a group of

faculty members and several Trustees

held an informal meeting.32

Although some Board members accepted the

evidence of a subversive

conspiracy within the Education faculty

and although some faculty

members resented even the slightest

administrative intrusion into

academic conduct, the moderate stance

expressed in the faculty reso-

lution allowed this small group to begin

to seek a solution to the prob-

lem which was creating so many

difficulties on the campus.

Once members of the Board of Trustees

learned firsthand the true

depth of faculty feeling on the issue,

the Board itself began a tortuous

effort to extricate itself from the full

consequences of its action. There

was some speculation that the abandonment

of Columbus by profes-

sional societies and conference groups

had had a severely adverse effect

on the city's hotel and restaurant

trade, and that this development influ-

enced the Trustees. More important,

perhaps, was the Board's percep-

tion that it had over-reacted in

September and that Ohio State was

being severely criticized in the

national media, including the New York

Times.33 Whatever the reasons, the Board met at Wooster, Ohio,

on

October 15 and proceeded to modify its

rule. Although the only sub-

stantive change was the suspension of

the ten-day clearance provision,

the Board agreed to meet with the new,

formally established Faculty

Council Committee, the successor to the

informal faculty group. At

the same time, the Trustees issued a new

clarifying statement, designed

"to encourage the fullest academic

freedom consistent with national

security."34 Still, the

Speaker's Rule stood firm, and, as General Dar-

31. Heimberger to Bevis, October 5,

1951, Box 45, File: Rugg . . . Correspondence,

E-K, Bevis Papers. Conference Committee

to Bevis, October 4, 1951, Box 45, File:

Rugg . . . Correspondence, A-D, Bevis

Papers. Minutes, Faculty Council, Ohio State

University, October 9, 1951, 2-9.

32. Pollard, Bevis, 146.

33. Milt Widder, "Sights and

Sounds," Cleveland Press, November 17, 1951. New

York Times, October 27, 28, 30, 1951.

34. Minutes, Board of Trustees, October

15, 1951, typed copy, Box 45, File: Prof.

Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis

Papers. Plain Dealer, October 16, 1951.

306 OHIO HISTORY

gusch asserted, "The president of

Ohio State still has the final say

about campus speakers."35

The Faculty Council Committee,

consisting of five members and two

alternates, met with four Trustees on

two occasions, October 26 and

November 16. At the first session, the

Board members asked the Faculty

Committee for a statement of principles

and procedures which would

embrace the faculty position and still

preserve the Board's intentions.

At the second meeting, the Committee

delivered such a statement,

which indicted the Trustees for placing

"restrictions on freedom of

discussion and investigation. By such

rules imposed on the Faculty

there is a danger of indoctrination by

exclusion of unpopular ideas."

The Committee recommended that the issue

be resolved in favor of free

discussion, but they also proposed that

the decision to invite speakers

whose views might be contrary to the

overall well-being of the Uni-

versity be made by the inviting faculty

member in consultation with

his colleagues, his chairman, his dean,

and the President, if necessary.36

Had the Board accepted the Committee's

position without alteration,

the supporters of academic freedom at

Ohio State would have been

more than completely vindicated. The

rule would have been revoked,

the Board would have lost face, and even

the traditional, pre-Rugg

restraints would have been jeopardized.

But this did not occur. Instead,

the Trustees took the first official

faculty proposal under advisement

and, in the interim, approved additional

interpretations of the rule.

These changes, announced by Bevis on

November 8 after he had con-

sulted with Dargusch, granted permission

for faculty members to

invite any speaker to a class, without

Presidential clearance, relying

only on a professor's own judgment; they

also provided that off-campus

organizations and professional societies

could meet without any

clearance procedure as long as they

accepted responsibility for their

own speakers. The Board approved these

interpretations on November

12.37

Neither the first meeting between the

Board and the Faculty Com-

mittee nor the November interpretations

entirely quelled opposition

to the Speaker's Rule. The Ohio State

chapter of the American Asso-

ciation of University Professors voted

to oppose the rule, and the

35. Lantern, October 16, 1951.

36. Pollard, Bevis, 148-49.

Faculty Council Committee Statement, November 19,

1951, Box 45, File: Prof. Rugg, Official

Correspondence, Bevis Papers.

37. Bevis to Dargusch (memo), November

6, 1951, Box 45, File: Prof. Rugg, Of-

ficial Correspondence, Bevis Papers.

Announcement of Interpretations, November 8,

1951, Box 11, File: Speaker's Rule

Controversy, The Papers of the College of Arts

and Sciences, Office of the Dean, RG

24/a, The Ohio State University Archives. Min-

utes, Board of Trustees, November 12,

1951, typed copy, Box 45, File: Prof. Rugg, Of-

ficial Correspondence, Bevis Papers.

OSU Speaker's Rule

307

national AAUP threatened an official

censure. The Graduate School

Council refused to approve the

interpretations, voting instead to sup-

port the Faculty Committee in its

continuing talks with the Trustees.

In a special referendum, Ohio State

students voted 2986 to 637 to

oppose the rule, and Dean Donald

Cottrell of the College of Education

wrote that the faculty's fight had not

yet been won. Finally, the Educa-

tion Faculty adopted a statement which

sought to counteract the con-

spiracy charge and to re-state their

principles and motives, so sharply

impugned by the local press.38

Final action on the Rugg controversy was

taken by the Board of

Trustees at its December 10 meeting.

After intensive private consulta-

tions involving Bevis, Board members,

and members of the Faculty

Committee, a detailed response to the

November 16 faculty proposal

was worked out to the parties' mutual

satisfaction. On December 13,

Bevis announced an extensive, three-part

revision of the policy on out-

side speakers. Responsibility for

inviting speakers and determining

their fitness was to rest with the

faculty. When a speaker's fitness was

questionable, a decision on the

invitation would be made through the

consultation process detailed in the

faculty proposal. In addition, a

Committee of Evaluation was to be

established to report annually on

the operation of the new procedure. The

Board had approved these

changes on December 10, and the Faculty

Council agreed on the 11th.39

The controversy surrounding the

invitation and appearance of Harold

Rugg at Ohio State was an intense,

protracted struggle which aroused

passions and divided the University

community. Both sides realized that

they were arguing over those principles

by which the University should

be run. So vociferous was this battle

and so basic the issue it raised that

neither side ever acknowledged defeat.

The Board of Trustees never

completely revoked nor repealed its

September 4 resolution. In each

month, October, November, and December,

the Board clearly labelled

its action as a new

"interpretation." Just before the December Board

meeting, at least one Trustee still

insisted that Rugg had been invited

surreptitiously, that the invitation had

violated a longstanding, unwrit-

38. George Eckelberry, "Academic

Freedom at Ohio State University," Journal of

Higher Education, XXII (December 1951), 497-98. Citizen, November

7, 1951. Dean

N. Paul Hudson, Graduate School, to

Bevis, November 12, 1951, Box 45, File: Prof.

Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis

Papers. "OSU Students Vote Against Gag,"

Plain Dealer, November 16, 1951. Cottrell to Benjamin Fine, November

12, 1951,

Box 25, File: Fine, Dr. Benjamin,

Education Papers. Faculty, College of Education,

"A Statement," Educational

Research Bulletin, XXX (December 12, 1951), 1-6.

39. James Fullington, Faculty Council

Committee, to Bevis, December 7, 1951,

Box 45, File: Rugg . . . Correspondence,

E-K, Bevis Papers. Minutes, Board of Trus-

tees, December 10, 1951, typed copy, Box

45, File: Prof. Rugg, Official Correspondence,

Bevis Papers. Minutes, Faculty Council,

December 11, 1951, 26-32.

308 OHIO HISTORY

ten policy, and that the Speaker's Rule

had done nothing more than

formalize that policy.40

On the other side, the faculty never

totally assented to the December

compromise. One member of the Faculty

Committee argued strongly

that the Board never admitted that the

rule was wrong in principle but

adjusted it simply to improve its

workability. Another Committee mem-

ber thought that the compromise fell

substantially short of the Com-

mittee proposal, that at least some

faculty members were still unhappy,

but that its real effect "was to

break down moral support for opposition

to the clearance rule."41

Between these two groups stood President

Bevis, who did not

emerge unscathed from the controversy.

Whatever Bevis' commitment

to academic freedom, he was constrained

by a Board of Trustees who

controlled policy and, with the

legislature, the purse strings of the

University. After his initial defense of

academic freedom, Bevis kept

his own views to himself and did the

Board's bidding. He incurred the

faculty's wrath for not representing

their point of view, especially in

public. But it is doubtful that he could

have remained as President had

he opposed the Trustees, and even then,

their course might not have

been altered. However important the free

discussion of ideas was to

Bevis and the Trustees, in 1951, with

Americans on the battlefield in

Korea, controversy even remotely

connected with national security

would not be tolerated.42

For several years thereafter, the

Committee of Evaluation, estab-

lished by the Board of Trustees in

December 1951, made a diligent effort

to assess the effects of the Trustees'

actions on academic freedom. Each

year, the Faculty Council elected the

Committee, which solicited faculty

opinion by means of a questionnaire and

reported its findings to the

President. The results of these surveys

strongly suggest that even by

1952 the controversy had pretty much

waned. Throughout the remain-

der of the politically quiescent decade

the procedures worked out in

December 1951 were effective in

preventing any further incidents

over the suitability of campus speakers.43

40. Statement of Robert Gorman, Board of

Trustees, December 6, 1951, Ohio State

University Monthly, XLIII (January 15, 1952), 33-34.

41. Letter to author from Dudley

Williams. Dean Jefferson Fordham, College of Law,

to Gorman, February 2, 1952, Box 26,

File: Gorman, Robert N., Education Papers.

42. On Bevis' attitude see letter to

author from Harvey Mansfield, Sr.; letter to

author from Harold Burtt; letter to

author from Grant Stahly; and Rod Peattie, Professor

of Geography, to Bevis, n.d., Box 45,

File: Prof. Rugg, Official Correspondence, Bevis

Papers.

43. Report on the Speaker's Rule, 1952,

Box 11, File: Speaker's Rule Controversy,

Arts and Sciences Papers. Some faculty

members commented that no incidents had

OSU Speaker's Rule 309

The failure of the 1951 compromise to

resolve the dispute became

apparent to all when political life

revived on campus in the early 1960s.

The administration invoked the speaker's

rule to ban California radical

William Marx Mandel in 1961, to prevent

three opponents of the House

Un-American Activities Committee from

speaking in 1962, and to

bar Communist party theoretician Herbert

Aptheker from addressing a

campus audience three years later.

Despite the vigorous protests of

students and faculty, the Board of

Trustees reaffirmed the speaker's rule

in May 1965 and reserved for the

administration ultimate authority in the

matter.44 Free speech remained fettered at The Ohio State University.45

arisen because no controversial speakers

had been approached to come to campus.

Another wanted a prominent liberal to be

invited, presumably by someone else, simply

to test the new rules.

44. Columbus Dispatch, April 26, 27, 28, 1962, April 24, May 21, 23, 1965; New

York

Times, April 26, 1962, April 24, May 21, June 9, 1965.

45. As of March 1978 there continues to

be a university rule governing the appear-

ance of guest speakers on campus. Rule

3335-5-06 of the University's Administrative

Code states: "It is the policy of

the university to foster a spirit of free inquiry and to

encourage the timely discussion of the

broad range of issues which concern our nation.

... no topic or issue is too

controversial for intelligent discussion on the campus.

Restraints on free inquiry should be

held to that minimum which is consistent with

preserving an organized society in which

change is accomplished by peaceful, demo-

cratic means."

Recognized student organizations and

faculty members may invite guest speakers

subject to provisions that the sponsor

insure that the meeting be orderly, that it be

made clear that the speaker expresses

his or her own views, and that the sponsor pro-

vide means for "critical evaluation

of a speaker's view," including as a minimum an

open question period.

The current rule also provides for those

situations when a speaker's appearance may

create "extreme emotional

feeling." In these cases, the steering committee of the uni-

versity senate has the right to

"prescribe conditions for the orderly and scholarly con-

duct of the meeting but may not select

the speaker or topic." The steering committee

may require that a tenured faculty

member chair the meeting, that attendance be lim-

ited to students, faculty, and staff,

that additional speakers be scheduled at the same

meeting or at subsequent meetings, or

that a debate format be utilized.

Finally, the present rule notes that no

speaker may advocate or "urge the audience

to take action which is illegal under

the laws of the United States, the state of Ohio, or

which is prohibited by the rules of the

university." Sponsors must inform each speaker

of this prohibition in writing.

STEVEN P. GIETSCHIER

The 1951 Speaker's Rule

at Ohio State

Like many public institutions of higher

learning, The Ohio State

University's support for the principles

of academic freedom has often

been limited by the political and social

views of those who have shaped

its destiny. Because of the university's

location in the state capital,

and certainly because of its dependence

upon a penurious General

Assembly for funding, Ohio State has,

over the years, generally re-

flected its origins as a land grant

institution. In the spirit of the Mor-

rill Act, the University has tended to

emphasize the practical arts over

the humanities and to cultivate a

functional and, when necessary,

patriotic approach to education. As

early as 1883, the Ohio State

Board of Trustees dismissed the

University's president, Walter Scott,

because "he promulgated unsound and

dangerous doctrines of politi-

cal economy," including the Henry

Georgian ideas that "capital was

robbery," and "dividends were

theft." In the ensuing years, however,

such spectacular incidents were few.l

After World War II, the Ohio State

administration responded to the

anxieties of the Cold War with a series

of policy decisions restricting

the exercise of academic freedom. Led by

its Board of Trustees and

by President Howard Bevis, the

University passed a series of resolu-

tions to regulate political discussion

on campus, the appearance of

outside speakers, and the right of

faculty members to discuss con-

troversial subjects in the classroom.

Overall, these measures demon-

strated the Trustees' decision that the

unrestrained exchange of ideas

must be partially curtailed in the

interests of national security.

Given the Board's composition, its

accommodation to the Cold War

ethos was hardly surprising. During

these years the Trustees were led

by Brigadier General Carlton Dargusch,

the former Deputy Director of

Selective Service, and by Senator John

Bricker, a conservative Repub-

Steven P. Gietschier is Director of the

Ohio Labor History Project at the Ohio His-

torical Society.

1. Alexis Cope, 1870-1910, ed. T.

C. Mendenhall, Vol. 1 of History of The Ohio State

University (9 vols., Columbus, 1920-1976), 79. For a wider

discussion of higher educa-

tion's sensitivity to public pressure,

see Richard Hofstadter, Anti-intellectualism in

American Life (New York, 1963), Chapters 12-14.

(614) 297-2300