Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

SHIRLEY LECKIE

Brand Whitlock and the

City Beautiful Movement

in Toledo, Ohio

"We are hearing much of the city

beautiful in these days," wrote

Brand Whitlock in 1912. "Hardly a

city or a town that has not its

commission and its plans for a unified

treatment of its parks, for a

civic center of some sort-in a word, its

dream." To Whitlock, who

had recently appointed a second Toledo

City Hall and Civic Center

Commission, these were "the

expression of that divine craving in

mankind for harmony, for beauty, for

order, which is the democratic

spirit."1

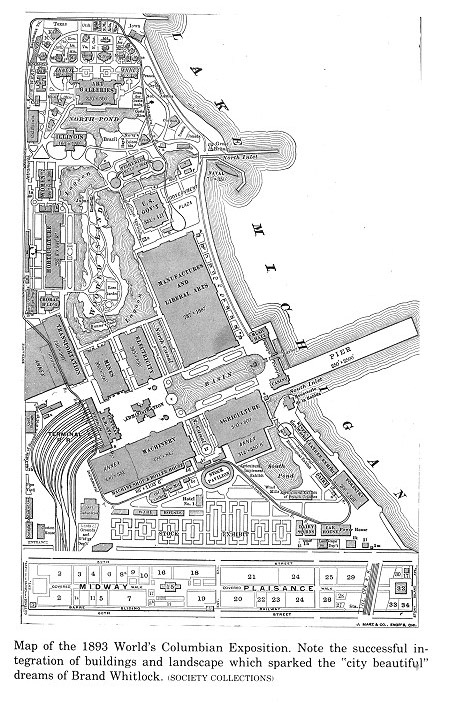

The Toledo mayor was an enthusiastic

supporter of the beautifica-

tion movement which swept the United

States at the turn of the

century. Originating in the earlier park

movement, it was, accord-

ing to Charles Robinson, one of its

leading practitioners, "immense-

ly strengthened, quickened and

encouraged" by the Columbian Ex-

position of 1893.2 The reconstruction of

Washington, D.C., in 1902,

based on the rediscovery of L'Enfant's

original plan, inspired simi-

lar projects elsewhere.3 While

none matched the success of the capi-

tol city, before the movement ran its

course, it led to the construc-

tion of civic centers, broad thoroughfares

and parks throughout the

United States. The cities that drew up

comprehensive plans in-

cluded San Francisco (1905), Los Angeles

(1907), New Haven (1910)

and Rochester (1911).4 By

1909, however, the movement had

reached its high point, culminating in

the publication of Daniel

Burnham's Plan of Chicago, a work

that in both concept and scope

Shirley Leckie is Associate Dean of

Continuing Education at Millsaps College.

1. Brand Whitlock, "The City and

Civilization," Scribners, 52 (November, 1912,),

623.

2. Charles Robinson, "Improvement

in City Life: Aesthetic Progressive," Atlantic

Monthly, 83

(June, 1899), 771.

3. John Reps, The Making of Urban

America (Princeton, N.J., 1965), 514.

4. Harvey Perloff, Education for

Planning: City, State and Regional (Baltimore,

1957), 55.

6 OHIO HISTORY

treated Chicago as the center of a

region. In its emphasis upon

transportation and circulation, it

forecast the direction city plan-

ning would take in the succeeding era of

the "city efficient."5

Not all of Whitlock's contemporaries

shared his enthusiasm for

the city beautiful, and even today,

historians and planners remain

divided concerning the movement's

significance and contribution.

One of the earliest critics was Louis

Sullivan, designer of the Trans-

portation Building, the one deviation

from the Beaux-Arts stan-

dards adhered to by all the other

buildings at the Columbian Ex-

position. The impact of the Chicago

Fair, especially its Court of

Honor, was so profound on the American

public that it ushered in

two to three decades of public and monumental

architecture domi-

nated by neoclassicism. Sullivan charged

that the Fair set back in-

digenous American architecture and

substituted "the virus of a cul-

ture, snobbish and alien to the land . .

"6 Charles Eliot Norton

agreed, noting that the Fair buildings

were "magnificent decorative

pieces, but otherwise not

architecture." Influenced by Sullivan's

functionalism, he concluded that:

"As they often failed to reveal the

purpose of the buildings behind them, so

they failed to express the

vital spirit of the nation."7

The largely derivative, neoclassical

architectural style, however,

was not the most important legacy of the

Columbian Exposition.

Both critics and supporters agreed that

the Fair demonstrated that

beauty depended largely upon the harmony

attained through a uni-

fied treatment of buildings and sites.

Daniel Burnham, one of the

Fair's chief architects, stated the

principle this way: "There are two

sorts of architectural beauty, first,

that of an individual building

and second, that of an orderly and

fitting arrangement of many

buildings; the relationship of all the

buildings is more important

than anything else."8 Americans

everywhere took note, contrasting

the serenity of the "White

City" with the urban chaos so prevalent

elsewhere. By crystallizing

dissatisfaction with existing cities, the

Fair acted as the catalyst for the first

large-scale efforts at changing

American cities.9

5. Daniel Burnham and Edward Bennett, Plan

of Chicago, ed. by Charles Moore

(New York, 1970). Originally published

by the Commercial Club of Chicago, 1909.

6. Louis Sullivan, The Autobiography

of an Idea (New York, 1956), 325. Originally

published by the American Institute of

Architects, 1924.

7. Quoted by Thomas Adams in Outline

of Town and City Planning: A Review of

Past Efforts and Modern Aims (New York, 1935), 181.

8. Quoted by Christopher Tunnard and

Henry H. Reed in American Skyline (New

York, 1956), 143-44.

9. Roy Lubove, The Progressive and

the Slum: Tenement House Reform in New

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 7

Proponents of the city beautiful

movement largely confined their

efforts to downtown sections,

thoroughfares, parkways and parks

and, on the whole, ignored the

deep-seated problems of housing and

congestion. Even while the Columbian

Exposition was still in prog-

ress, a group of settlement workers,

attending a conference in Chi-

cago, organized their own exhibit to

underscore the contrast be-

tween the "White City" and the

all too prevalent slums and tene-

ments in Chicago and elsewhere.10

In 1925 the Committee for Community

Planning of the Regional

Plan Association of America, in a Report

to the American Institute

of Architects, dismissed the city

beautiful movement as "an attempt

to put a pleasing front upon the scrappy

buildings, upon the monoto-

nous streets and the mean houses that

characterized the larger

American cities." This same Report,

moreover, alleged that the

"grand avenues and places were

costly beyond measure, and, when

all was said and done, they did not

fundamentally alter the environ-

ment in which the greater part of the

population, rich and poor,

were still destined to live."11

Finally, many critics have charged that

the movement drew its

constituency from middle and upper

classes, businessmen's groups

and commerce clubs and, in the end, its

appeal was often based on

boosterism, while the values it promoted

were commercial, not so-

cial. Adherents of this view cite Daniel

Burnham's Plan of Chicago,

originally published by the Commercial

Club of Chicago, which con-

tained the following statement:

"The plan frankly takes into consid-

eration the fact that the American city,

and Chicago predominantly,

is the center of industry and traffic.

Therefore attention is given to

the betterment of commercial facilities,

the method of transporta-

tion for persons and goods; to removing

the obstacles which prevent

or obstruct circulation; and to the

increase of convenience." The

needs of workers received attention

because: "It is realized also, that

good workmanship requires a large degree

of comfort on the part of

the workers in their homes and their

surroundings, and ample

opportunity for that rest and recreation

without which all becomes

York City, 1890-1917 (Pittsburgh, 1962), 217-18.

10. Stanley P.Caine, "Origins of

Progressivism," in Louis L. Gould, ed., The Pro-

gressive Era (Syracuse, N.Y., 1974), 25.

11. Committee for Community Planning of

the Regional Plan Association of

America, Report to the American

Institute of Architects, in Roy Lubove, The Urban

Community: Housing and Planning in

the Progressive Era (Englewood, N.J.,

1967),

124.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 9

drudgery."12 As one

historian would later note, such concerns "be-

tray the values of the

businessman."13

The city beautiful movement has had its

defenders as well as its

critics. The historian Roy Lubove, for

example, has viewed the

movement as valuable for a number of

reasons. Beginning with the

Chicago Fair, he notes: "However

one might disparage the some-

what sterile classicism of the fair,

its ultimate influence was salut-

ary. Americans saw in its planned

beauty, order and picturesque

design an irresistable alternative to

the dirt, monotony and prevad-

ing dinginess of the existing

municipalities. This," he contends,

"was the real meaning of the

Chicago Fair, it created new ideals and

standards by which to measure the

quality of urban life."14 Else-

where he states: "Probably the most

distinctive legacy of the City

Beautiful was the ideal it embodied of

the city as a deliberate work

of art."15 Yet another

authority notes: "The symbolic value of the

magnificent fair can hardly be

overstated; it encouraged people to

think about their cities as artifacts,

and to believe that with suffi-

cient effort and imagination they could

be reshaped nearer to im-

ages of civilized living."16 Such a view represented a necessary pre-

condition for the widespread acceptance

of a professional city plan-

ning movement and this was the major

contribution of the city

beautiful movement. It paved the way for

the creation of municipal

planning agencies.

In Toledo, Ohio, largely through the

continuing efforts of Sylvan-

us Jermain, the architect E. O. Fallis,

and individuals such as Wil-

liam H. Maher, George Stevens, and above

all, Mayor Brand Whit-

lock, the drive for the city beautiful

accomplished two things: it

perpetuated the older ideals of the park

movement and it left in its

wake a city planning commission. It

achieved little success, howev-

er, in its major objectives-the

establishment of a notable city hall

and an impressive civic center. To a

large extent, continuing divi-

sions within the community, both in

terms of attitudes and geogra-

phy, worked against these projects. But

despite its limited achieve-

ments, the Toledo city beautiful

movement merits scrutiny. While a

number of long-held historical

generalizations about the movement

12. Burnham, Plan of Chicago, 4.

13. Mel Scott, American City Planning

Since 1890. A History Commemorating the

Fiftieth Anniversary of the American

Institute of Planners. (Berkeley.

1969), 107.

14. Lubove, The Progressive and the

Slum, 218.

15. Lubove, Urban Community, 9.

16. Charles N. Glaab and A. Theodore

Brown, History of Urban America, 2nd ed.

revised by Charles N. Glaab (New York,

1976), 240.

10 OHIO HISTORY

are validated, in Toledo's case some

are not. A careful examination

indicates that Brand Whitlock, Toledo's

major advocate for civic

beautification, was motivated by ideas

that were far more compli-

cated and idealistic than those held by

many city beautiful propo-

nents elsewhere.To understand this, one

has to begin with Whitlock

and his attitudes toward cities in

general.

Whitlock was an enthusiastic supporter

of city life. There had

long been a tradition among American

intellectuals, dating back

most notably to Thomas Jefferson, that

city life was "artificial."17 In

Toledo, among Whitlock's associates in

the beautification move-

ment, S.P. Jermain often argued the

need for parks on the basis that

city life was "unnatural."18

Whitlock disagreed-not on the need for

parks, but on the character of life in

municipalities.To Toledo's

mayor, the city was "the most

natural thing in the world, an

elemental form of human association

like the family or tribe, built

in obedience to some divine, if obscure

instinct."19 This was true, he

explained elsewhere, because:

"Mankind is gregarious. People love

to live together and so all down

through history, we find them

crowding together on small acres of land

..."20 Moreover, not only

did Whitlock accept cities as natural,

but he was at times almost

evangelical concerning their benefits.

It was in the city that man

would "free himself from the

slavery of an obdurate isolation and

from the thraldom of primitive

fear." It was the city that repre-

sented "the symbol of his titanic

effort to conquer nature." And

finally, it was in the city that man

achieved the necessary security

and found the opportunity "to rise

above the merely physical, and to

release the spirit to higher

flights."21 In short, to Whitlock the city

and civilization were coterminous.

In this, Whitlock was not original. He

echoed often the ideas of

other progressives, especially those of

Frederick Howe whose works

he not only read, but reread many times.

Whitlock referred con-

17. Morton and Lucia White, The

Intellectual Versus the City: From Thomas Jef-

ferson to Frank Lloyd Wright (Cambridge, Mass., 1962).

18. Jermain constantly referred to city

life as "artificial" or "unnatural" through-

out the 1890s and early 1900s. By 1909

he had not changed his mind. See: Sylvanus

P. Jermain, personal letter to Emma K.

Rinehart dated 12 May, 1909, S.P. Jermain

Collection, Personal Correspondence in

Local History Room of the Toledo Public

Library (hereafter referred to as

Jermain Collection).

19. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 631.

20. Brand Whitlock, "Toledo-Its

City and Its People," Speech delivered in Toledo,

Ohio, on 27 February 1906, 3. Located in

Brand Whitlock Papers in Library of

Congress, Washington, D.C. (hereafter

referred to as Whitlock Papers).

21. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 629.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 11

stantly, for example, to Howe's

"excellent book," The City: The Hope

of Democracy, and agreed wholeheartedly with the book's thesis,

stated in its title.22 Whitlock

elaborated on this in various writings.

In 1912 he reasoned that since cities

were "microcosms" of the larg-

er society, "in them the cleavages

that divide society are easily

beheld, the problems that weary mankind

are somehow reduced to

simpler factors .. ."23 Thus it

made sense that in an urban setting

America's problems could be most easily

identified and eventually

resolved. Two years later in his

autobiographical work he made this

comment regarding Tom Johnson, the

progressive Cleveland mayor:

"I do not know how much of history

he had read, but he knew

intuitively that the city in all ages

has been the outpost of civiliza-

tion and if the problem of democracy is

to be solved at all, it is to be

solved first in the city."24 This

possibility inspired Whitlock; it had,

he thought, implications, not only for

the United States but for the

entire world as well, and this led him

to prophesize in 1912:

"Already we apprehend a new truth,

that in the inspiring tendency

of the neo-democratic spirit there is to

be realized not only aesthetic,

but an ethic beauty, and the time is

foreshadowed when our cities

will be beautiful in works, in their

spirits and in the common lot and

in the individuality, the personality of

their citizens." Then he

added his own statement of the old idea

of the "city upon a hill."

"And thence from the city into the

state and from the state into the

nation, is it, in this old and moody and

nervous age, too much to

hope?-from the nation into the world. It

is the dream of America, at

any rate, the goal of democracy and the

purpose of civilization."25

Before the American city could represent

a beacon to the rest of

the world, however, it was necessary

that it become what Whitlock

termed the "free city." He

described this freedom in a number of

ways. From the practical standpoint, the

necessary precondition for

a free city was, of course, a free

citizenship, and this required the

advancement of democratic principles and

reforms. Viewed politi-

cally, the free city would no longer be

subservient to a rural-

dominated legislature, nor would it

continue to be administered by

political machines financed by corrupt

businessmen. Instead it

22. Ibid, 626. See also other

references such as Brand Whitlock, "Patriotism vs.

Partyism: A Straight Conscience vs. a

Straight Vote," Saturday Evening Post, 179 (17

November 1906), 9; Brand Whitlock, Forty

Years of It (New York, 1925), 1973. Origi-

nally published in 1914.

23. Whitlock, "City and Civilization,"

633.

24. Whitlock, Forty Years of It, 172

25. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 633.

12 OHIO HISTORY

would enjoy home rule, embrace the

principles of nonpartisanship,

and would achieve municipal ownership

of utility and traction

companies.26 At a deeper,

moral level, however, Whitlock believed

that cities, like men, possessed their

own unique characters. On one

occasion he was quoted in the popular

press explicitly on this point.

"Cities have personalities, just

as men have; and cities must be left

free to realize these

personalities."27 Moreover, the truly free city

like the truly free person would be

essentially moral, obeying its

own internal, freely chosen moral code,

based on an understanding

of the "law of social

relations."28 For that matter, cities would play

an instrumental role in the uncovering

and illumination of this law.

Whitlock stated it this way: "The

cities are the centers of the na-

tion's thought, the citadels of its

liberties, and, as they were once

and originally the trading posts and

the stockades whence the hardy

pioneers began their conquest of the

physical domain of the conti-

nent, so are they now the outposts

whence mankind is to set forth on

a new conquest of the spiritual world

in which the law of social

relations is to be discovered and

applied."29 Once this was achieved,

then the "free city" would

provide a setting in which men would

become free, not simply as citizens,

but as persons. In 1907 he had

summarized his views in this statement:

"We want cities that will

be filled with free civic spirit,

expressing itself in artistic forms;

above all cities that will be better,

kindlier places to live in, cities

that will offer to every man on equal

terms the opportunity to live a

beautiful life-that is, to realize his

own personality. For this is the

great purpose of democracy-to let every

man realize his own

personality."30

Whitlock was both more cautious and

critical in his thought and

expression and more reserved in his

bearing and personality than

his predecessor Samuel Jones had been.

Nonetheless, it is obvious

that at this stage of his life he

maintained an optimistic faith in

democratic progress. Evidence of this

is found in his autobiographi-

cal work Forty Years of It, in

which he wrote, for example: ". . . it is

the vast strain, the irresistable urge

of democracy to render life

26. Whitlock, "Patriotism vs.

Partyism," 8; See also "The Free City," Saturday

Evening Post, 180

(6 June 1908), 3-5, and comments by Jack Tager, The Intellectual

as Urban Reformer: Brand Whitlock and

the Progressive Movement (Cleveland,

1968),

79, 145-46, 181.

27. Whitlock, "Patriotism vs.

Partyism," 8.

28. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 633; Whitlock, Forty Years of It, 366-67.

29. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 633.

30. Again see Tager, The Intellectual

as Urban Reformer, 79.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 13

more equal, more secure, more precious

in obedience to an instinct

that grows less and less obscure, as

amid the perplexities of life,

reason and the good-will of men discern

a better purpose, a better

order and a better way."31

For Whitlock, the city played a crucial

role in advancing this

progress. The interdependence of urban

life created both the ne-

cessity and the opportunity for men to

come together, share ideas,

seek solutions and finally overcome the

"hard selfishness of unres-

trained individualism."32 This

had been Howe's recurrent theme in

his most famous work on the American

city, and it was an idea that

Whitlock wholeheartedly embraced.

Whitlock's study of history, combined

with his reading of Howe,

convinced him that the development of

great cities followed an evo-

lutionary path. In February 1906,

shortly after becoming mayor, he

shared his ideas on city development in

an address entitled "Tole-

do-Its City and Its People." The

speech, beginning with the words

"Toledo has reached a crisis in her

development," represented a call

to begin beautifying the city,

specifically by constructing a notable

city hall as the focal point for an

impressive civic center.

There was, Whitlock thought, echoing

Howe's ideas on civic im-

provement, a natural, but not

inevitable, progression in the history

of cities. First came the physical

development of the area, a period in

which a "large population crowded

together on one piece of ground"

and in which eventually there were

"many streets crossing each

other with houses on them and people

living in the houses, coming

and going and bustling about them with a

great business." At this

stage the town still exhibited a good

many "provincial characteris-

tics," the citizens displayed a

"village" outlook, and, in general, it

was difficult to begin and complete

municipal projects because the

citizenry lacked what Whitlock, quoting

Howe, termed a "city

sense." This was the stage Toledo

had reached in its development.33

Whitlock never really succeeded in

defining the "city sense" with

any precision. As late as 1912 he still

found the idea somewhat

nebulous. "It is something vague

and dim, unrealized as yet, some-

thing difficult to describe, perhaps

impossible to define." Yet it

struck him as extremely important.

"It is something more than

civicism, or the sense of solidarity, or

mass consciousness; it is the

31. Whitlock, Forty Years of It, 371.

32. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 631.

33. Whitlock, "Toledo-Its City and

Its People." For Whitlock's indebtedness to

Frederick C. Howe, see The City: The

Hope of Democracy (Seattle, 1967), 239-48.

14 OHIO HISTORY

expression of the common hopes and

ardors of mankind . ."34 In his

1906 speech before Toledoans, Whitlock

did not attempt to give a

definition, but he did inform his

listeners that it was the one prereq-

uisite to the building of a true city:

"Before there can be a city, there

must be the 'city sense'," adding,

"Toledo is big enough to take on

the airs of a city, not as a mere

affectation, but because the problems

that confront the multitudes of people

who compose a city cannot be

solved unless there be unity and

collective effort. The people must

be inspired by a single ideal, and all

other things must be subsidiary

to the achievement of this ideal."35

Prior to the emergence of the "city

sense," Toledo, like other

municipalities, would remain fixed in

that stage in which citizens

devoted their energies and efforts to

simply obtaining commercial

prosperity. Elsewhere he explained that

this was the period in

which men viewed their city "merely

as a place to make a living but

not to live in."36 By

1906 Toledo was "large and prosperous and

wealthy," and it was time for the

city to take the next step and begin

"to build in the municipal

sense." After all, he had observed Toledo's

character and personality, and he was

convinced that the city pos-

sessed "a great and free spirit . .

. I believe," Whitlock told his

audience, "that the time has come

when Toledo must begin to real-

ize her own individuality, and it is

important, I think, that we take

counsel and decide how this shall be

done."37

There were a number of concerns that

demanded immediate

attention. The city needed a larger

police force, a more efficient

health department, while its social

agencies were, the new mayor

warned Toledoans, "woefully behind

the times." He termed the

workhouse "an anachronism and a

shame" and the city prison "a

disgrace." There still existed no

municipally owned hospital, no cen-

ter for the treatment of tuberculosis,

and little in the way of agen-

cies to care for orphans or to

rehabilitate juvenile delinquents.38 Yet

critical as all these needs were, the

purpose of Mayor Whitlock's

speech was to arouse Toledoans to the

necessity of making their city

more beautiful.

He noted that it was commonly agreed

that the time had come for

the city to construct a new bridge over

the Maumee. Civic pride also

dictated that Toledo build a number of

new municipal buildings, for

34. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 631.

35. Whitlock, "Toledo-Its City and

Its People," 1.

36. Whitlock, "City and

Civilization," 631.

37. Whitlock, "Toledo-Its City and

Its People," 1-2.

38. Ibid, 2-3.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 15

there existed only one municipal

building "worthy of the name," and

that was the courthouse constructed in

1897. Moreover, Toledo rep-

resented an anomaly among cities; it had

no city hall. "The city

today is living in rented quarters that

are as inadequate in the space

they provide as they are unworthy of the

dignity of a municipality

that makes any municipal

pretensions." The cost of renting space

for city offices was increasing

annually, and given this situation

prudence dictated building a city hall

as quickly as possible. Since

this was the case, Whitlock argued that

"splendid results" could be

"obtained and magnified many fold

if the city hall and the bridge

and other public buildings that must be

erected-the police stations,

fire houses, schools-are part of one

comprehensive scheme that

embraces the whole city and includes its

parks, its boulevards, its

playgrounds, and its water front."39

Whitlock had grasped the cen-

tral idea of the city beautiful

movement, with its emphasis upon the

construction of monumental civic

structures, designed to harmonize

architecturally as part of a

comprehensive plan. At the very least,

attention was given to the landscape

architecture of the building

sites and the surrounding areas. The

more ambitious projects, such

as Chicago's Plan of 1909, dealt

extensively with the development of

parks, boulevards and parkways,

especially those along the lake

shore.40

To bolster his arguments, Whitlock

reminded his listeners of the

history of the world's great cities.

"Athens was a commercial center

long before Pericles and Phidias crowned

her with those works of

municipal art that have since been the

inspiration and despair of all

citizens." A similar pattern had

developed in Rome, later in Venice,

Florence, Milan, and even later in

Vienna, Munich and Frankfort,

among other notable cities. More

recently in the United States, in

Washington, the dream of L'Enfant and

Jefferson was "now slowly

being realized in concrete and material

form." Elsewhere other

cities had been inspired, and in New

York, San Francisco, Kansas

City, Cleveland and even in Springfield,

Illinois, "this same city

sense is expressing itself in the form

of movements for a unitifed

treatment of public buildings."41

39. Ibid, 3-4.

40. Burnham, Plan of Chicago. In

this 1970 edition by DeCapo Press, there is an

excellent introduction from the original

Commercial Club edition by Wilbert R. Has-

brouck. On page viii Hasbrouck discusses

the long-term results of Burnham's plans

for the lake shore as they would be

realized over time in the Chicago metropolitan

region.

41. Whitlock, "Toledo-Its City and

Its People," 3-4.

16 OHIO HISTORY

Whitlock then turned to the major point

of his address. "It seems

to me, therefore, and I wish to propose

to you tonight, that the time

is auspicious for the city of Toledo to

decide upon some definite,

artistic and beautiful plan for the

construction of these public build-

ings which are inevitable, if this city

is to maintain its growth and

fulfill the predictions we have so long

been making for her." He was

not, he reminded his listeners,

"insensible to the many obstacles,"

but he expressed confidence that . . .

"if other cities can overcome

them, we can overcome them. In the very

process of overcoming

them," he added, "we shall

increase our own strength and effective-

ness and intensify the spirit of unity,

the wholesome spirit that

must make what has been called the city

sense."42

Thus to Whitlock, the building of a city

hall.as the nucleus of a

civic center represented the physical

manifestation of an ideal he

sought for Toledo. It arose not simply

from boosterism, although

there were comparisons with other

municipalities and references to

a national movement in which he hoped

Toledo would participate.

Rather, Whitlock viewed "municipal

art" or "municipal adornment"

(he used both terms interchangeably) as

expressions of "democracy

in artistic forms." Above all, the

very act of building a city hall and

civic center would contribute to the

growth of the vital "city sense,"

and after its completion, the existence

of these commonly-owned

and beautiful buildings would both

nurture and strengthen that

essential requirement for the growth of

a great city.

To accomplish this, he called for a

commission "whose duty it

should be to consider this

question." He charged it with the task of

soliciting ideas from Toledo citizens,

investigating the progress of

other cities, and finally directed it

"to secure the services of artists

and architects who have had experience

in this work elsewhere, and

before it is too late, to decide on some

plan to which we propose to

adhere in the future."

As a beginning, he advocated the

submission of a three to five

million dollar bond issue to the voters,

and at the same time warned

citizens that if they failed to act

"the opportunity will have forever

passed, and Toledo will be outstripped

in the race for municipal

prominence by other cities that are not

blessed with half her natural

advantages," adding: "When we

have such a place as this, or such as

they have in Washington, or in New York,

or in Cleveland, or in

Boston, then our ideal has already taken

concrete form and we can

begin to work toward it, and to live up

to it; and finally," he noted,

42. Ibid, 4-5.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 17

"long after we have gone away, of

course, there will be here a city in

which the ideal of democracy will be

realized; a city that shall help

every one of its citizens to lead a

kind, helpful and beautiful life." At

the conclusion of his speech, he again

emphasized the importance he

assigned to such a project. "If we

are to enlarge our cities, we must

enlarge our ideas and our ideals, and

sectionalism and provincial-

ism must be left behind. We must think

in urban sequences, and in a

word, if we would have a city, we must

build a city."43

Whitlock seized any opportunity he could

to advance his ideas on

Toledo's need for civic beautification.

When his young friend Fran-

cis Macomber, the Director of Public

Safety, died in 1908, a memo-

rial service in January of the following

year seemed an appropriate

occasion, especially since Macomber had

shared Whitlock's views on

beautification and had prepared his own

plans for a civic center.44 In

his address, Whitlock praised Macomber's

interest and his contribu-

tion to the further development of

Toledo's parks, playgrounds and

the city beautiful ideal. To a large

extent, the city beautiful move-

ment continued the work begun by the

older park movement, keep-

ing alive its hopes for "breathing

spots" within the city and stres-

sing the importance of incorporating

rural aspects into the city

proper.45 A new emphasis had

been added, however, visible in the

stress on harmony, unity and

coordination. The older idea that art,

combined with nature, would act as

teacher and uplifter for the

masses was still accepted, and the way

in which older and newer

ideas were blending can be seen in

Whitlock's eulogy for his friend.

"He thought that the activities of

a city should be so coordinated

that they would present a vision of

harmony, and in the vast scheme

which he planned of parks and

playgrounds and groups of public

buildings and al that-there were to be

for all the people the benison

of healing, of music, of all the

arts."46

Four years later, Whitlock made similar

comments at the funeral

of William H. Maher, a prominent

Toledoan. Like Macomber, Mah-

er had given the mayor support in his

beautification projects and, in

addition, he had served on both the 1910

and 1912 City Hall and

Civic Center Commissions. In this

eulogy, Whitlock again re-

counted the many civic contributions

Maher had made, noting espe-

cially his efforts at arousing interest

in improving Toledo's appear-

43. Ibid, 4-6.

44. Whitlock, Forty Years of It, 208.

45. Lubove, Urban Community, 9.

46. Brand Whitlock, "Remarks at

Memorial Service for Franklin Smith Macomber

at Zenobia Theatre," Toledo, Ohio, 3 January 1909,

Whitlock Papers.

18 OHIO HISTORY

ance, stating, "... the end of his

labors was to present to the city

fathers a plan for the improvement of

the physical order of the

town," a plan that Whitlock held

would express in physical form

"the worth and character and the

beauty of that town."47

Throughout these writings and in his

autobiographical work Forty

Years of It there was one other recurrent theme. Whitlock constant-

ly referred to the hope of transforming

the American city into the

New Jerusalem, the Heavenly City here on

earth. Again, there was

nothing original about this. Other

progressives, especially those

who were proponents of the Social

Gospel, such as the clergyman

Washington Gladden, had expressed

similar hopes based on old

Christian themes and ideas, revived to

bolster and invigorate the

progressive crusade to reform American

city life.48 Moreover, de-

spite the differences in intellectual

sophistication and personality,

Whitlock had been deeply influenced by

his mentor and friend,

Samuel Jones. Jones' speeches, as

Whitlock frankly acknowledged,

were sermons. Thus perhaps it is not

surprising that at times Whit-

lock also gave what can be termed

secular sermons rather than

speeches, and, like Jones, reached back

into Christian thought and

traditions to describe his own hopes as

a progressive.49 The follow-

ing passage from the Memorial Service

for Macomber gives some

evidence of this strain in Whitlock's

thought. Referring to Macom-

ber, Whitlock stated: "Practical as

he was, he was essentially an

idealist, and he had a dream of a whole

beautiful city in which men

would be equals and brothers, a city of

loving friends." Then he

added what would become for him a constant

theme. "It was an old

dream, the oldest dream in the world; to

the mystic John on Patmos,

it was as a city that Heaven was

revealed, a city symmetrical and

complete ... it is the beautiful dream

of democracy and brother-

hood, a dream which will come true in

America when men can

envisage it as it appeared in the

imagination of Franklin

Macomber."50 Whitlock's

funeral oration for Maher touched the

47. Brand Whitlock, "Remarks at

Funeral of William H. Maher," 4 February 1913,

Toledo, Ohio, Whitlock Papers.

48. Whitlock, Forty Years of It, 374;

Thomas Kail, "Urban Visions and Visionaries:

Responses to the Rise of the Industrial

City," (Ph.D. dissertation, The University of

Toledo, 1975), 125.

49. Whitlock described in considerable

detail the strong impact Jones made on his

life in a number of writings, most

notably Forty Years of It, 112-51. In a short essay

"Golden Rule Jones" in The

World's Work, September 1904, 5308-11, Whitlock de-

scribed the effect of Jones' speeches:

"And so it was that the stranger happening into

a Jones meeting might have supposed that

it was a religious meeting, or at least a

revival . . ."

50. Whitlock, "Remarks at Memorial

Service for Franklin Smith Macomber,"

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 19

same themes. "There had come to him

the conception of a city, a

conception hidden from the minds of many

persons, as a place where

all its people might find life beautiful

and splendid, if only inequali-

ties might be lessened and privileges

and immunities done away."51

Whether these men shared Whitlock's

fervent enthusiasm is im-

possible to say. The constant reference

to the city as a dream so

idealistically expressed probably

revealed more about Toledo's pro-

gressive mayor than the individuals he

was praising. By 1914, in

the concluding paragraphs of Forty

Years of It, he returned to the

same theme and expressed it in similar

ways:

... For the great dream beckons, leads

them on, the dream of social

harmony always prefigured in human

thought as the city. This radiant

vision of the city is the oldest dream

in the world. All literature is saturated

with it. It has been the ideal of human

achievement since the day when the

men of the plains of Shinar sought to

build a city whose towers should reach

unto heaven. It was the angelic vision

of the mystic on Patmos, the city

descending out of heaven, and lying

foursquare, the city where there was to

be no more sorrow nor crying....52

Whitlock was not the first Toledo mayor

to campaign actively for

a city hall, nor was he the last. His

predecessor, Samuel Jones, had

felt the need keenly, and in 1899 had

devoted a part of his annual

Mayor's Message to the topic. To Jones,

as to Whitlock several years

later, renting was impractical, since

the cost increased each year.

More important, however, there was the

question of public dignity.

If a city were truly great, it would

have proper quarters in which to

conduct its business.

While Jones did not advance the idea of

building a civic center, he

did propose that the city hall should be

placed in a spacious setting,

leaving room for public gatherings such

as speeches, band concerts

and other recreational and educational

public events. To expedite

this, Jones announced that he, the City

Solicitor, the City Clerk,

and a representative from the Board of

Alderman and two from the

Common Council had determined that the

most desirable site lay

between Adams, Madison, Michigan and

Ontario Streets.53

Toledo, Ohio, 3 January 1909, Whitlock

Papers.

51. Whitlock, "Remarks at Maher

Funeral," Toledo, Ohio, 4 February 1913, Whit-

lock Papers.

52. Whitlock, Forty Years of It, 374.

53. Samuel Jones, "Mayor's

Message," Annual Statement of the Finances of Tole-

do: Together with the Mayor's Message

and Reports of the Various Departments for the

Year Ending April 1st, 1900 By Order

of the Council (Toledo, 1900), 20-21.

Located in

20 OHIO HISTORY

A year later, Jones returned to the

subject in his 1900 Mayor's

Message, and this time he based his

appeal on grounds different

from those of public dignity of

practicality. A city hall would stand

as physical evidence of Toledo's

community spirit, he informed his

audience, since this would be one

building owned in common by all

city inhabitants. "There is a real

dignity underlying the idea of

democratic equality to which our system

of government is commit-

ted. We are all equals only at the

ballot box as yet, but we must

actualize the idea of equality, and

there is no way that we can better

do this than by enlarging the scope of

common ownership." A well

constructed city hall would contribute,

moreover, to both "civic

pride" and "the spirit of

patriotism." In this light, it seemed obvious

to Jones that "Toledo should not

occupy renter quarters beyond the

term of the present lease."54

No progress was made toward building a

civic center during Jo-

nes's administration primarily because

most of Toledo's residents

and council members gave priority to the

construction of a new

Cherry Street Bridge. Since 1890 a

number of bridge plans had been

advanced; none of them gained the

support of the entire community.

Those that were given serious, if often

momentary, consideration

encountered lawsuits, and thus the

matter of building a new bridge

dragged before the City Council for well

over a decade. In April

1906, Mayor Whitlock reluctantly

approved City Council's recom-

mendations for a straight bridge,

beginning at Cherry Street on the

west side and extending to Main Street

on the east side, a steel

structure, eighty-two-and-a-half feet

wide with a projected cost of

$665,000. The mayor expressed his

disappointment, stating that he

had favored building a U-shaped bridge

that would have followed

the lines of the Jackson Street Viaduct.

But he did not veto the

measure since he hoped that by signing

the legislation, the bridge

would be completed as rapidly as

possible.55 Instead, the proposed

bridge aroused new controversy,

resulting in lengthy lawsuits, and

it was not until March 1910 that the

legal impediments were re-

moved and construction actually began.

By this time the projected

cost had risen to about one million

dollars, while the date set for

completion was optimistically given as

1913.56 The bridge opened a

the Local History Room of the Toledo

Public Library I hereafter referred to as Annual

Report (1899)].

54. Samuel Jones, "Mayor's

Message," Annual Report (1900), 17.

55. Toledo Blade, 19 April 1906.

56. Toledo Blade, 26 March 1910.

|

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 21 |

|

|

|

year later in 1914, while construction work continued for another three years. Despite the many problems that had plagued its completion, the bridge, designed by architect Arnold W. Brunner, received national publicity and widespread praise. the American City extolled the concrete structure, which was 1,200 feet long and designed with a central span allowing for a clear channel of 200 feet, as "an example for other cities, proving as it does that a bridge may be absolutely useful and at the same time a thing of beauty."57 Whitlock's interest in the city beautiful movement had preceded his electon as mayor of Toledo. He had first raised the issue publicly in a speech given at Memorial Hall in 1902 and had returned to the subject in an address delivered two years later at the Toledo Club. In

57. "Toledo Spain and Toledo, Ohio," American City, 11 (August, 1914), 116-17. |

22 OHIO HISTORY

July 1906 and again in January 1907, he

had brought the matter

before the City Council, but it appeared

that Council did not share

the mayor's interest.58 He

did, however, enjoy the support of indi-

vidual Toledoans, such as E. O. Fallis,

the architect, and George

Stevens, the Director of the Toledo

Museum of Art. Fallis, for exam-

ple, had drawn up fairly elaborate and

painstaking plans for a civic

center as early as 1904, selecting a

site on Jackson Street, across

from the courthouse, at that time

Toledo's only impressive public

building.59

In March 1907, George Stevens arranged a

public exhibition at

the Toledo Museum of Art, devoted

entirely to the results of the city

beautiful movement elsewhere. Among the

displays were models of

Washington, St. Louis, Buffalo, San

Francisco, and, closer to home,

Cleveland. New plans drawn up by Fallis

were also shown, under

the auspices of the Toledo Architectural

Club.60 Fallis' newest civic

center design was both more ambitious

and extensive than the ear-

lier one had been. In 1904 he had

located the civic center between

Jackson, Cherry, Tenth and Huron

Streets, placing the city hall

northwest of Courthouse Square and the

police headquarters be-

tween Spielbusch and Canton. The

original plans had called for a

new public library to be built east of

the civic center mall, and

beyond that, an art museum, while on the

slope below Cherry

Street, he had proposed that the city

erect a new large auditorium.

These earliest plans had only envisioned

the widening of Jackson

Street at one end of the proposed new

Cherry Street Bridge. By

1907, however, Fallis's revisions

included widening Beech Street

into a boulevard and joining Summit,

Cherry and St. Clair into a

circular drive.61

Francis Macomber had also drawn up plans

for a civic center.

Shortly after his

death in 1908, Sylvanus Jermain, a

prominent

Toledoan active in the park movement,

presented them to the

mayor.62 In an open letter,

dated May 12, 1908, to Emma K. Rine-

hart, a Toledo woman active in the

Playground Association, Jer-

main called upon the Board of Park

Commissioners to begin acquir-

ing land in the core of the city between

the Courthouse and Cherry

58. Toledo Blade, 13 April 1912.

59. John M. Killets, Toledo and Lucas

County, Ohio 1623-1923. 3 vols. (Chicago,

1923), 510:I.

60. Toledo Blade, 22 March 1906,

23 March 1907, 24 March 1907.

61. Toledo Blade, 24 February

1911; Toledo City Journal, 7 (8 July 1922), 289.

62. Killets, Toledo and Lucas County,

Ohio, 510:1.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 23

Street, and additional land on the east

side on Front Street adjoin-

ing the site of the proposed new high

school.63

Shortly after this, at the City Council

meeting of May 24, 1909,

Mayor Whitlock announced that, following

Jermain's open letter, he

had received a message from the Board of

Park Commissioners,

calling for a meeting of all municipal

department heads. Its purpose

was to consider placing before Toledo

voters a bond issue sufficient

to build a city hall, civic center and

complete the park and boulevard

system and any other matters

"deemed advisable." The City Council

passed a resolution, requesting the

mayor to appoint a City Hall

Commission to first study the proposed

projects.64

Mayor Whitlock selected a group of

well-known Toledoans which

included William H. Maher, Harry T.

Batch, George B. Rheinfrank,

John Ulmer and Sylvanus P. Jermain.65

The commission issued its

report to the Mayor on March 28, 1910,

in a document which began:

Every citizen is in most hearty sympathy

with any wish and effort that is

made towards making Toledo a City

Beautiful. A similar civic spirit is

quickening the whole country, and all

thinking men and women agree that

they not only owe it to themselves, and

to their children, but succeeding

generations, that their surroundings

should appeal to the senses, and that

the spirit of beauty, as well as of

utility, shall guide the community in its

plans for the future.66

It was unfortunate, the report

continued, that the original city

fathers had not seen fit to set aside

adequate space "for breathing

and recreation grounds and for locations

for public buildings that

every growing city must possess."

This had resulted in lost opportu-

nities and meant, moreover, that the

costs would be far greater now

that these problems were being rectified

at a later date. Despite

this, the commission cautioned that

further delay would only add to

the future burden of debt, and, in this

light, any further postpone-

ment of Toledo's building needs was

viewed as "not only unwise, but

... impossible."67

63. Sylvanus P. Jermain, personal letter

dated 12 May 1909, in S.P. Jermain

Collection.

64. "Minutes of the Toledo Park

Commissioners," 15 June 1909. Located on Micro-

film in the Northwest Ohio Regional

Center, Bowling Green State University.

65. Toledo City Journal, 7 (8

July 1922), 289.

66. "Report of the City Hall

Commission Made to Mayor Whitlock and By Him

Transmitted to the Common Council," Sylvanus P.

Jermain "Scrapbook," 221, Jer-

main Collection.

67. Ibid.

24 OHIO HISTORY

The commission's report advised the city

to acquire, through

purchase or condemnation, the property

bounded by Beech, Erie,

Jackson and Spielbusch Avenues.

Estimating the value of this prop-

erty at $325,000, it advised the city to

construct a city hall at a

projected cost of $350,000. A more

ambitious plan, calling for the

purchase of an additional four blocks

north of the courthouse in

order to build a Cherry Street city

hall, had been discarded as im-

practical due to the "great expense

and our heavy burden of debt."

Instead the commission's report called

for erecting the city hall

north of the Court House Square in the

two blocks between Jackson,

Erie, Beech and Spielbusch. As for the

police headquarters, the

report recommended the placement of a

safety building north of the

county jail near Beech Street.68

In his report to the council on April

18, Whitlock endorsed the

document fully, reminding the City

Council that a city hall as the

basis for a civic center was not simply

a place to conduct the city's

business, but rather: "It is

primarily for the people, and it should

reflect the people's aspirations, their

identity and their spirits."

Then he added: "it should bring

forth in a material form the city's

pesonality and be constructed, not for

utility alone, but with higher

purposes of art and beauty. It should

be," he concluded, "the city's

center and heart, with beautiful and

imposing surroundings. It

should be a place in which the people

find joy and pride and become

an inspiring and ennobling influence on

the community."69

That November, Toledo voters approved a

$360,000 bond issue,

and the first bonds totalling $300,000

were sold in January 1911.

When the first land appropriation bills

passed the City council in

February, it appeared that Whitlock's

hopes for a civic center would

soon be realized.70 The Mayor

now enjoyed the support of a number

of groups, including the Toledo Civic

Federation and the Commerce

Club. These two organizatons, in fact,

had done much to ensure the

passage of the November bond issue, and

it was largely due to their

efforts that Arnold Brunner, a leading

architect actively involved in

Cleveland, Baltimore and Rochester beautification

projects, arrived

in the city early in February.71

Brunner spoke to a number of local

groups, showing slides of

improvements in European and American

cities and restating the

68. Ibid.

69. Toledo Blade, 19 April 1910

70. Killets, Toledo and Lucas County,

Ohio, 510:I.

71. Toledo Blade, 2 February

1911.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 25

common themes of the park and city

beautiful movements. Such

projects, he assured Toledoans, were not

undemocratic. To the con-

trary: "Art isn't for the rich man

exclusively, for the rich man can

buy it and take it home. Art ought to be

where the poor man can

have it close." In this sense he

praised the preliminary work com-

pleted by the Toledo City Hall

Commission; its members had laid

the foundation for Toledo's civic

renaissance. Brunner did find it

unfortunate, however, that Toledo had

waited this long to begin

such an undertaking, for one of the

costs of postponement was a lack

of coordination among the city's various

improvements. An example

of this was the new Museum of Art,

currently under construction at

the corner of Monroe and Scottwood,

which should have been a part

of the proposed civic center. His advice

to Toledoans was that in the

future they should keep their city offices

closer together for both

convenience and beauty. He also

commented on the city's downtown

area, noting the relatively narrow major

thoroughfares, and, for this

reason, warned against building

additional skyscrapers. Not only

would they further decrease the amount

of light and the number of

trees in the city, but the additional

traffic generated would overtax

the capacity of the surrounding streets.72

Finally, at his last public speech,

delivered at the Memorial Hall

Annex, Brunner concluded with this

statement: "Toledo has an

opportunity for a civic center equalled

by no other city in America,

and," he added in remarks similar

to those made twelve years before

by the landscape architect George

Kessler during his visit to Toledo,

"the same may be said of the

possibilities of beautifying her water-

front." The new thrust towards the

emerging science of city plan-

ning was evident in his final words.

"In the building of a city, it is a

crime not to plan for the future. A

scheme for the future means

economy."73

In March, Memorial Hall was the scene of

an exhibit displaying

the plans for Toledo's proposed civic

center, the new Cherry Street

Bridge, which was under construction,

and a projected continuation

of the park and boulevard system. This

exhibit, largely the result of

the efforts of Mayor Whitlock,

celebrated Toledo as a "progressive"

city and included "a report, as it

were," according to the Survey, "of

the elected directors and public agents

of Toledo." Its purpose was to

acquaint citizens with the fifteen

different departments overseeing

72. Ibid.

73. Toledo Blade, 4 February

1911.

26 OHIO HISTORY

the various municipal functions and to

give Toledoans a better idea

of developments planned for the future.74

The progress towards the building of a

city hall and civic center

was more apparent than real. Even as the

first City Hall Commis-

sion met, other Toledoans were calling

attention to another long-

standing and increasingly serious

municipal problem. As Toledo

had grown, annexing what had formerly

been independent com-

munities, there had emerged three

distinct sections to the city-

east, west, and south, all separated

from one another by either the

Maumee River or the meandering course of

Swan Creek. Moreover,

passage from one part of the city to

another was impeded by traffic

congestion occurring at certain critical

points. The new Cherry

Street Bridge would eventually alleviate

the congestion between

Summit Street on the west bank and Main

Street on the east. It

would, however, have little effect on

the traffic problems encoun-

tered in going from Summit Street to

Broadway, the south side's

major thoroughfare.75

For decades thoughtful Toledoans had

sought to eliminate some

part of Swan Creek as a first step

towards the straightening of

Summit Street. The lengthy jog between

Summit and Broadway,

characterized as the south side's

"Chinese Wall," represented a se-

rious impediment to the free flow of

traffic from Toledo's business

district to the rapidly expanding neighborhoods

to the south. As

early as 1870 a councilman from the

Fifth Ward had proposed shift-

ing Swan Creek's channel eastward,

filling in its west band and

extending Summit Street through to

Broadway.76

At that date there was still

considerable traffic on the old Miami

and Erie Canal, but by the twentieth

century much of this had died

out and the canal bed now emptied into

the creek. By 1908 a group

calling itself the South Side

Improvement Association demanded

the elimination of the rest of the canal

bed and Swan Creek within

the city limits. In a resolution

addressed to City Council, the Asso-

ciation proposed the diversion of both

streams through Delaware

Creek above Walbridge Park. Furthermore,

the plan was both feasi-

ble and advantageous, for the city would

be spared, among other

things, the cost of maitaining bridges

over the two streams. The

improvement would result, moreover, in

reclaimed land, which,

74. James P. Heaton, "Budget

Exhibits in Two Cities, "Survey, 26 (April, 1911),

135.

75. See Toledo News-Bee, 28

November 1912, which contains a lengthy interview

with Dan Segur, the son of a southside councilman.

76. Toledo News-Bee, 28 November

1912; Toledo Times, 5 February 1913.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 27

given the area's excellent railroad

facilities, would provide a desir-

able site for wholesale and warehousing

establishments. More im-

portant, it would permit the

straightening of Summit Street as well

as the extension of Superior, thereby

tying south and west Toledo

directly together for the first time.

Finally, south-siders noted that

the Lake Shore Railroad had indicated

its willingness to begin plan-

ning for a new and impressive Union

Station, once the area in

question had been improved and Summit

Street had been

straightened.77

While these considerations were all

important, the major impetus

for the elimination of Swan Creek

stemmed from the fact that the

stream had become "an open

sewer." In the nineteenth century, lum-

ber yards and saw mills had lined its

banks just below Summit

Street. By 1900 this activity had

diminished, leaving behind un-

sightly decaying wharves and buildings.78

As south Toledo's popula-

tion expanded, the creek received

increasing amounts of sewage and

industrial waste. One authority

estimated that by 1911 as many as

six million gallons of sewage emptied

into the torturous and slow

moving steam on a daily basis. Droughts

were not uncommon dur-

ing the summer months, and when the

water level fell, area resi-

dents found that their environmental

problems were exacerbated.79

By the summer of 1910 the problem had

assumed crisis propor-

tions. Angry south-siders met

frequently, voicing their demands

that the city take immediate action. To

further their cause they

passed a resolution appealing to the

State Board of Health to in-

vestigate the situation. One Colonel J.

C. Bonner spoke for many

residents when he warned: "Toledo

will never be a great city until

Swan Creek is eliminated .... The Swan

Creek improvement should

be made right now without any more

talk." Others agreed. "You

talk about booming Toledo," noted

one disgruntled citizen, "making

it bigger and better. We have three

cities now. Eliminate Swan

Creek and we will have one. Begin in the

center of the city and work

outward."80

Mayor Whitlock responded to these

complaints by appointing a

special commission, including E. O.

Fallis, ex-state representative

Louis Paine, Councilman James Staunton,

physician Peter Donnely

77. Toledo Blade, 15 December

1908, 17 December 1908.

78. Toledo Blade, 17 December

1908.

79. Toledo Blade, 20 August 1910,

19 March 1912. See also George Sherman,

"Pollution of Swan and Ten Mile

Creeks" (Toledo, n.p., 1911), 12. "Swan Creek-

1908-1948" MSS collection located

in Local History Room of Toledo Public Library.

80. Toledo Blade, 30 August 1910,

11 September 1910.

28 OHIO HISTORY

and city engineer George Tonson. They

were assigned the task of

recommending solutions to the problems

of Swan Creek and the

Miami and Erie Canal bed within the city

limits. When the group

made little progress in the winter and

spring of 1911, the Mayor

approached the City council, and in June

received appropriations

permitting the commission to hire the

services of George Sherman,

a civil engineer.81

Sherman quickly became convinced that the

city confronted two

separate but related issues. One

concerned the question of eliminat-

ing, or at least reducing, the growing

pollution of Toledo's streams

and waterways. The other stemmed from

the need to determine the

feasibility of altering Swan Creek's

channel in order to tie the city

together. He concluded very quickly that

whatever else the city

decided to do, it had to begin

constructing an intercepting sewer

system as rapidly as possible. In March

of 1912, before the commis-

sion as a whole was prepared to file its

report, Sherman, on the basis

of a preliminary report, discussed what

he saw as the city's three

alternatives and indicated his personal

preference.82

As he reviewed the matter, it was

necessary that Toledo build an

intercepting sewer at a minimum cost of

$200,000. For an expendi-

ture of $650,000, Sherman thought that

the creek's neck could be

straightened, resulting in a freer flow

of water. The course which he

favored, however, was to direct the

stream into the Maumee at

Delaware Creek after constructing a

large intercepting sewer. He

estimated that the entire cost of this

was $2,250,000.83 The other

commission members filed their own

separate report, and the rift

which had developed between Sherman and

the others is obvious in

the following statement contained in the

separate report: "The com-

mission derived but little benefit from

the engineer appointed. In

fact the engineer acted entirely

independent of the commission and

to some extent assumed its

functions."84

Apparently unaware of the serious

implications these problems

held for his plans, Whitlock, in April

1912, appointed a second City

Hall and Civic Center Commission whose

members included both

Maher and Jermain from the first City

Hall Commission, in addi-

81. Toledo Blade, 27 September

1910, 29 June 1911.

82. Toledo Blade, 19 March 1912;

see also Sherman's "Pollution of Swan Creek and

Ten Mile Creek," 11-12.

83. Ibid.

84. Toledo Tug Men's Association

"Swan Creek" (Toledo, Published by the Tug

Men's Association, n.d., 1913), 12-13.

Located in "Swan Creek-1908-1948" MSS

collection.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 29

tion to the retired industrialist Edward

D. Libbey and two other

prominent Toledoans, H.W. Ashley and

J.F. Egan. The extent of

Whitlock's optimism regarding the

proposed city hall and civic cen-

ter can be seen in the directives he

gave this second group. Since no

one believed any longer that the city

could build a proper city hall

for $350,000, these men were asked to

determine whether Toledo

should spend as much as 1.5 million or

limit itself to $750,000 for

the proposed structure. Whitlock,

moreover, now hoped that the

civic center would also include a new

Soldier's Memorial Building,

and the new commission was asked to

select an appropriate site.

Finally, despite the fact that the first

commission had recommended

the small plan, rather than the large

plan which entailed extending

the civic center's boundary to Cherry

Street, this new body was

asked to reconsider that question.85

In the spring of 1912 many

Toledoans, most notably the mayor, were

confident that the prop-

osed civic center would soon

materialize.

On October 7, the second commission,

after consultations with the

architect Arnold Brunner, presented its

findings to the mayor.

Essentially it favored an expenditure of

$750,000 to one million

dollars for a building, 160 by 160 feet,

designed to "harmonize

architectually with the court

house." In addition this group selected

a civic center site similar to the one

recommended by the first com-

mission, the area bounded by Erie,

Jackson, Spielbusch and Beech

Streets. Now the commission suggested

broadening the streets lead-

ing into the civic center and widening

Beech Street, so that it could

form a direct link to the new Cherry

Street Bridge.86

On October 23, 1912, two weeks after the

second City Hall and

Civic Center Commission issued its

recommendations, the City

Council authorized a bond issue for

$750,000.87 Early in 1913

Arnold Brunner again arrived in Toledo

to begin working with the

architectural firm of Mills, Rhines,

Bellman and Nordhoff.88 For an

entire year, Brunner and this firm

worked on plans for the proposed

city hall and civic center, but the

final outcome was meager. In 1917

the American Institute of Architects

revealed that despite an ex-

penditure of $30,000, "at no time

was a printed report of the pro-

ceedings of the Committee submitted, nor

any drawings of the pro-

85. Toledo Blade, 23 April 1912.

86. Toledo Blade, 8 October 1912.

87. Killets, Toledo and Lucas County,

Ohio, 513:I.

88. Toledo Blade, 5 February

1913.

30 OHIO HISTORY

posed civic center and the grouping of

buildings therein made."89

There were good reasons why this

happened. Shortly after the

passage of the new bond issue late in

1912, the Swan Creek ques-

tion, which had been an issue for some

time, erupted in full force.

Sherman's recommendations, while not

those of the Swan Creek

Commission, received substantial support

among south Toledoans.

By January of 1913 a group known as the

Swan Creek Elimination

League was waging a strong campaign for

their implementation.

Specifically the group dedicated itself

to the "entire elimination of

Swan Creek and the canal within the city

limits by diverting both

through Delaware Creek above Walbridge

Park." The League's

pamphlets and newspaper advertisements

argued: "We will get rid

of one of the worst nuisances any city

could be cursed with. In a

short time the Swan Creek basin would be

filled with streets and

houses that would increase the tax

duplicate so as to entirely pay

out the principal of the debt incurred,

the interest being paid out of

the expenses cut out. We will

then," the League continued, "tear

down the Chinese wall between south and

north side of the Swan

Creek basin and give free commercial and

social intercourse be-

tween the two sides." Since the

area in question was the location of

the Union Station, League pamphlets

informed Toledoans: "We will

then clean house and permit visitors to

Toledo to get and retain a

favorable impression of our otherwise

beautiful city."90

There is no evidence that the Swan Creek

Elimination League

ever received funds from any of the

railroads which owned property

in the area, known in Toledo as the

Middle Grounds. The Clover

Leaf, for example, still maintained

wharves along Swan Creek and

objected to the League's elimination

plans. When it became known,

however, that Lake Shore officials had

endorsed the League's plans,

members of the Civic Federation withdrew

their original support.91

By February of 1913 a new group calling

themselves the Conserva-

tionists had formed in opposition to the

League and public meetings

were scheduled to allow both sides to

debate one another. E.O. Fal-

lis, although a member of the mayor's

Swan Creek Commission,

joined the Conservationists, who by now

had attracted such well

known community leaders as Irving

Macomber, the brother of the

late Francis Macomber, and the

industrialist John Willys.92 It

89. American Institute of Architects,

Committee on Town Planning, City Planning

Progress in the United States: 1917 (Washington, D.C., 1917), 178.

90. Toledo Blade, 5 February

1913.

91. Toledo Blade, 14 February

1913, 14 June 1913.

92. Toledo Blade, 21 February

1913.

Whitlock and the City Beautiful 31

seems probable, although it cannot be

stated with certainty, that

both Fallis and Macomber saw in the

League's objectives a threat to

the mayor's proposed civic center.

The Conservationists attempted to

counter the League's proposals

by arguing that Swan Creek, in its

entirety, should be retained and

beautified. Fallis went so far as to

draw up plans calling for the

building of a park between Cushing and

Newton Streets, connected

to a proposed extension of Summit Street

by a winding drive. On the

east bank of Swan Creek, Fallis hoped,

the city would erect a play-

ground. "I can imagine the children

playing there now, laughing

and romping on the green, splashing

barefooted in the ponds, doing

a thousand joyful things that arise

spontaneously, and," he added,

indicating the faith that progressives

still placed in parks and play-

grounds, "I can see all of this

weaving into the tapestry of a better

world."93

By May of that year, the Swan Creek

Elimination League pre-

sented to the mayor a petition carrying

7,000 signatures, calling

upon the city to set an election date

for a vote on the creek's elimina-

tion within the city limits. For the

first time, the two issues of

building a civic center and eliminating

the Swan Creek nuisance

were explicitly joined. The petition

began by stating that the creek's

elimination took precedence over any

other project currently under

consideration. It then added that while

the League did not oppose

the building of Whitlock's civic center,

it did question the advisabil-

ity of constructing a "truly

colossal and expensive civic center," a

"luxury" which could only

diminish the commercial productiveness

of city land and decrease the city's tax

base. By contrast, the elim-

ination of Swan Creek would add to the

city's store of usable land,

and in this way over the years would

increase the municipal tax

rolls. Most important, however, the

petition noted that the creek's

elimination would remove a long-standing

health hazard.

The petition also argued with

considerable justice that the pro-

posed project would provide

beautification benefits similar to those

of boulevards and parks. Furthermore,

important railroad com-

panies, such as the New York Central and

Lake Shore, had indi-

cated that once Swan Creek and the canal

bed were eliminated from

the city limits and Summit Street

straightened, they were prepared

to work with the city on plans for the