Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

DANIEL NELSON

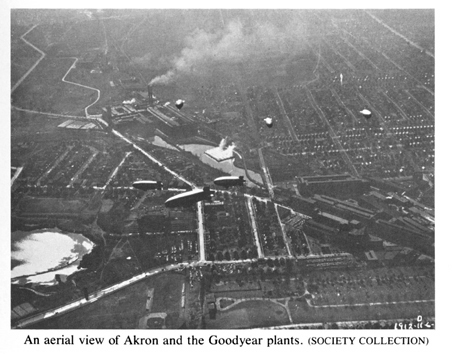

The Great Goodyear Strike of 1936

It was the "first" CIO strike,

a "stepping stone toward the automo-

bile industry," an affirmation of

the potentialities of the sit-down

strike, a case study of rank and file

militancy, and a "remarkable" ex-

ample of the effects of non-violent

agitation.' Its beginnings were ob-

scure, its consequences uncertain.

"The circumstances in which the

strike was carried on and the method

used" rather than the imme-

diate causes or results made it a

turning point in the labor history of

the 1930s.2 It was the great

Goodyear strike, which paralyzed Akron

for more than a month in February and

March, 1936.

Contemporary journalists and writers,

all CIO partisans, first called

attention to the importance of the

conflict. Edward Levinson and

Mary Heaton Vorse published brief

histories of the strike in 1937;

Ruth McKenny followed in 1939, Alfred W.

Jones in 1941, Rose Pe-

sotta and Harold S. Roberts in 1944.3

These works, building blocks

for more recent students of the

turbulent years, help explain the often

insubstantial foundations of their

studies.4 The Levinson and Vorse

Daniel Nelson is Professor of History at

The University of Akron. He is indebted to

Bernard Sternsher, Warren Van Tine and

Lorin Lee Cary for their critical reading of an

earlier draft of this essay.

1. John Brophy, A Miner's Life (Madison,

1964), 264; Edward Levinson, Labor On

the March (New York, 1956), 146; "Lewis Wins Akron

Victory," Business Week (March

28, 1936), 20; P. W. Chappell to H. L.

Kerwin, March 21, 1936; Federal Mediation and

Conciliation Service Records, National

Archives RG 280, File 182/1010.

2. "The Goodyear Tire & Rubber

Co. Strike," Monthly Labor Review, 42 (May,

1936), 288. The most recent and

comprehensive assessment of the labor history of the

1930s is Bernard Sternsher,

"Workers in the 1930's: Middle Range Questions and

Ethnocultures," Paper presented to

the 1982 meeting of the Organization of American

Historians, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

3. Levinson, Labor On the March, 143-46;

Mary Heaton Vorse, Labor's New Millions

(New York, 1938), 5-6; Ruth McKenny, Industrial

Valley (New York, 1939), 277-370;

Alfred W. Jones, Life, Liberty and

Property (Philadelphia, 1941), 101-07; Rose Pesotta,

Bread Upon the Waters (New York, 1944), 195-227; Harold S. Roberts, The

Rubber

Workers (New York, 1944), 147-51.

4. Walter Galenson, The CIO Challenge

to the AFL (Cambridge, 1960), Ch. 6; Irving

Bernstein, Turbulent Years (Boston,

1970), 592-97. James R. Green; The World of the

Worker (New York, 1980), 153.

|

Goodyear Strike of 1936 7 |

|

|

|

accounts are hopelessly flawed, inaccurate in virtually every detail. The McKenny book is more fiction than fact, worthless except for its description of the activities of the local Communist party, the one fea- ture of the conflict the author knew from firsthand experience. The Jones essay is highly speculative; the Roberts account is superficial. Pesotta's recollections, though accurate and valuable, are limited by her tangential role in the dispute. But factual errors and distortions are only part of the problem. With the possible exception of Jones, the early students of the Goodyear strike reflected the intellectual milieu of the 1930s. Whether liberal or radical, they brought to their work a set of assumptions that strongly colored their writing. The strike was a struggle between progress (the workers, represented by the United Rubber Workers) and reaction (the company). Because the union was "right," it "won" the strike and provided a powerful example for other workers. For decades no one questioned these judgments and assumptions.5 Essentially the strike is no more acces- sible than it was forty years ago.

5. The Goodyear historian attributed the strike to a small group of malcontents and CIO agitators. Hugh Allen, The House of Goodyear (Akron, 1949), 368-72. |

8 OHIO HISTORY

A reexamination of the Goodyear strike,

based in part on informa-

tion unavailable to the writers of the

late 1930s and early 1940s, sug-

gests a different view. The conflict was

indeed a precursor of the sit-

down era and a test of the CIO, as the

early historians of the strike

observed. But it bore few other

similarities to their schemata. Good-

year was hardly a reactionary employer

and the URW wore the man-

tle of progress badly. The principal

struggle featured hostile groups of

workers, not management and labor.

Though the URW was the ma-

jor beneficiary of the strike, few

knowledgeable union leaders would

have chosen it as an example for other

workers. And far from demon-

strating the strength of the CIO, the

Goodyear strike exposed the

limitations of the Lewis group. Not

least, the strike was a reminder of

the critical role of groups other than

managers and workers in the re-

sults of the struggles of the 1930s.

The major events of the Goodyear

conflict are not in dispute. Fol-

lowing many months of hostility between

the Rubber Workers locals

and the Akron manufacturers, a series of

brief sit-downs closed sev-

eral plants in January and early

February, 1936. The overriding issue

was the Goodyear decision to shift from

the six-hour day, which it

had adopted in 1930, to the conventional

eight-hour day and to dis-

charge redundant fourth-shift workers.

The last of the sit-downs, at

Goodyear Plant 2, led to a series of

meetings and ultimately to a spon-

taneous move to picket Goodyear on the

evening of February 17.

From that point the contest escalated

rapidly. The workers soon

picketed the entire Goodyear complex, halted

production, and idled

nearly 15,000 employees. URW Local 2

took up the cause of the

fourth-shift workers, transforming the

dispute into a full-scale con-

frontation between the URW and the

industry's most powerful em-

ployer. CIO leaders rushed aid to the

strikers. The company refused

to negotiate and obtained an injunction

that severely restricted the

pickets; the sheriff's effort to enforce

the injunction produced the

most famous incident of the strike, a

dramatic confrontation between

deputies and strikers on February 25.

Faced by 5000 club and gun-

wielding strikers, the law officers

retreated and the plant remained

shut. After February 25 the strike

became an endurance contest,

with federal and local government

representatives trying to foster ne-

gotiations. A breakthrough occurred in

mid-March when company

representatives prevailed upon union

leaders to accept a compromise

plan. At a ratification meeting on March

14, the workers rejected the

proposed settlement. Within hours former

mayor C. Nelson Sparks

announced the formation of a Law and

Order League to reopen

Goodyear. Unhappy with the prolonged

strike, most Akron citizens

Goodyear Strike of 1936 9

were even less pleased with the prospect

of a violent confrontation.

The League effort quickly aborted.

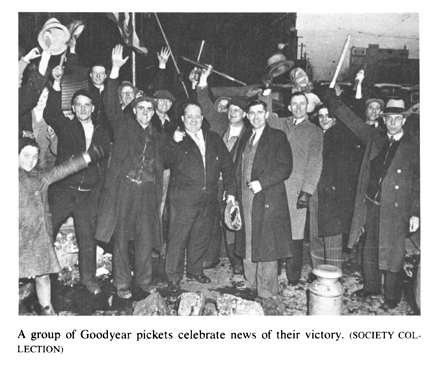

Negotiations resumed and the

company made additional concessions. On

March 21 the strikers ap-

proved an agreement that continued the

six-hour day and provided

formal grievance procedures for union

members. Akron unionists,

their CIO allies, and, it seemed,

industrial workers in Detroit, Flint,

and other cities viewed the settlement

as a unprecedented victory.

The Sit-Downs

To later observers the most distinctive

feature of the strike was its

beginning. In early 1936 the sit-down

was a novelty in American in-

dustry, a little-used expression of rank

and file protest.6 The Good-

year strike irrevocably changed that;

henceforth the sit-down would

be a hallmark of the militant behavior

associated with the rise of

mass production unionism and the CIO.

Like John L. Lewis, it be-

came a symbol of "labor on the

march." But it is essential to distin-

guish between the impact of the

sit-downs of January 28-February 18

on Goodyear workers and on outsiders.

Neither the sit-down as a

weapon nor the tactics of the successful

sit-down were new to the

former. The first sit-down in the rubber

industry had occurred at

the General Tire Company in June 1934;

the sit-down era in American

industry dated from that incident.7

In 1934 and 1935 rubber workers

avoided sit-downs because of lingering

hopes that negotiations or liti-

gation would result in conventional

bargaining procedures and be-

cause of union leaders' desires to avoid

strikes. By late 1935, howev-

er, many workers had become

disillusioned with the unions, and

sit-downs resumed, this time without

union sanction. There were two

in late 1935, both successful.8 They

were a modest prelude to the up-

heavals of 1936.

Four of the six sit-downs associated

with the beginning of the

Goodyear conflict were reminiscent of the

General Tire sit-down.9 At

Firestone on January 28, at Goodyear

Plant 2 on January 31, at Good-

rich on February 7, and at Goodyear

Plant 2 again on February 14,

6. For the background of the sit-downs,

see Daniel Nelson, ed. "The Beginning of

the Sit-Down Era: The Reminiscences of

Rex Murray," Labor History, 15 (Winter, 1974),

89-90.

7. Ibid., 91-96.

8. Akron Beacon Journal, Nov. 8, 11, 1935.

9. This paragraph is based on Daniel

Nelson, "Origins of the Sit-Down Era: Worker

Militancy and Innovation in the Rubber

Industry, 1934-38," Labor History, 22 (Spring,

1982), 208-11.

10 OHIO HISTORY

tire builders, the handicraft workers

who assembled tire casings be-

fore vulcanization, instigated the

protests. Their actions were rela-

tively brief and non-violent. Though

unauthorized, they were trade

union protests for improved working

conditions; the tire builders

had no larger visions or goals.

Employers also reacted much the same

way as they had in 1934. They did not

attempt to expel the strikers.

Instead, they kept the plants open and

tried to reduce tensions. In-

deed, the Firestone personnel manager

inadvertently gave the tech-

nique a powerful boost when he agreed to

pay strikers half their

wages for the period they occupied the plant.

Executives and super-

visors apparently were more surprised

than frightened by the sit-

downs; at least until the Goodyear

strike, they did not grasp their

disruptive potential.

The other sit-downs, at Goodyear Plant 1

on February 17-18 and at

the Columbia Chemical Company in nearby

Barberton, Ohio, from

February 17 to February 22 are less

well-known, because they oc-

curred after the beginning of the

Goodyear strike, but no less impor-

tant. They introduced features of the

sit-down movement that would

become increasingly prominent in the

following months. Both inci-

dents involved workers who had not sat

down in the past and who

had no special grievances. They

dramatized the infectious character

of the sit-down movement. Like their

co-workers and neighbors, the

Goodyear and Columbia Chemical workers

sat down without union

authorization. At Goodyear Plant 1

several hundred tire builders sat

down when the Plant 2 workers began to

picket. On the evening of

February 18, 200-300 women tube workers

joined them. At Columbia

Chemical eight, then forty, then 460

workers, an entire shift, sat by

their machines. Like the rubber workers,

they succeeded in

resolving grievances. And they, too,

perplexed and antagonized com-

pany and union officials.10 Their

actions were irrefutable evidence

that the sit-down was not unique to the

rubber industry and that in-

dustrial employees required only the

briefest exposure to it to per-

ceive their latent power.

The other notable aspect of the Goodyear

Plant 1 and Columbia

Chemical sit-downs was the employers'

response. At General Tire

and at Firestone, Goodrich, and Goodyear

Plant 2 the plant manag-

ers had carefully avoided any

provocations that might lead to van-

dalism in the occupied buildings. For

various reasons they behaved

differently in the other two cases. When

the Plant 1 workers sat

10. See Akron Beacon Journal, Feb.

18, 1936; Akron Times Press, Feb. 18, 20, 22,

1936.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 11

down, Goodyear managers sealed off the

struck departments. They

maintained heat and power, but barred

access to the rest of the

plant. Unable to go to the cafeteria,

strikers lowered ropes to outside

pickets who attached packets of

sandwiches. Yet many of the work-

ers had no way to reach the outside

windows and thus went hungry.

For this reason, as well as the union

leaders' desire to reinforce the

elongated picket line, the Plant 1

strikers left the plant at midnight on

the 18th.11 The Columbia Chemical

managers hastily shut their

plant on February 18. They could not

turn off the heat because of

sub-zero tempratures, but otherwise they

isolated the strikers. For

the workers this approach presented

immediate problems. But after

some deliberations they decided that an

unpleasant existence in the

plant was superior to frigid picket

duty. To compensate they adopted

techniques that became famous in Flint

and elsewhere in 1937. Wives

"formed almost a continuous line .

. . carrying food and supplies to

their husbands" which they passed

through the windows.12 The

strikers slept on benches and amused

themselves with boxing

matches and other amateur

entertainments. This regimen continued

until a union-management agreement ended

the occupation five days

later.

The sit-downs of January 28-February 22

also foreshadowed much

of the subsequent history of the

Goodyear strike. They were protests

against the status quo, the Goodyear

management but also the organ-

izations, including the URW, that vied

for the workers' allegiance.

They created opportunities for the

Rubber Workers, but underlined

the need for new and more vigorous policies

if the union was to be

successful. The sit-downs marked the

beginning of a period of reas-

sessment and conflict among the workers

that often overshadowed

the better known struggle between

management and "labor."

The Non-Strikers

The Goodyear strike marked the beginning

of the decisive phase

in the evolution of formal workers'

organizations at Goodyear. The

first phase had occurred between 1910

and 1920 with the growth of

Goodyear and the rise of Paul W.

Litchfield as production superin-

tendent and later vice president for

manufacturing. Under Litchfield,

Goodyear installed an extensive array of

employee benefit programs,

11. Akron Times Press, Feb. 19,

1936.

12. Ibid., Feb. 20, 1936.

12 OHIO HISTORY

notably insurance, athletic, and stock

and home-ownership plans.13

A unique feature of the Goodyear effort

was the "flying squadron," a

select group of production workers who

were trained to perform any

task in the factory. Their assignment

was to prevent delays that

would curtail production in the

integrated complex.14 The capstone

of the Litchfield effort was the

Industrial Assembly, an elaborate

congressional-style company union formed

in 1919. The Industrial

Assembly was a "flying

squadron" of the rank and file, an institution-

al device for maintaining personal

contact with the workers, boosting

morale and productivity, and, when necessary,

resolving griev-

ances.15 Though the postwar

recession of 1920-21 decimated Good-

year and its labor force, the ensuing

reorganization enhanced

Litchfield's standing (he became

president in 1926), and preserved

the personnel program. The effects of

the depression of 1930-33 were

similar. Production, profits, and

employment opportunities declined,

but the personnel program remained

intact.

The NRA posed the first serious

challenge to the Goodyear pro-

grams. Workers from all the rubber plants

rushed to join the AFL

federal locals established in the summer

of 1933. The Goodyear lo-

cal's membership may have reached 7000.16 It offered an

alternative

to the Industrial Assembly, one

seemingly more attuned to the New

Deal era, and many former Assembly

leaders joined the new organi-

zation. They soon discovered that the

AFL union could do little

more than the company union. By late

1935, when relations between

the Rubber workers and the rubber

manufacturers reached crisis

proportions, the Goodyear local had less

than 500 members.17 On

the eve of the Goodyear strike, neither

organization represented

more than a small minority of Goodyear

workers. The Industrial As-

sembly seemed inadequate and the URW

unsuccessful.

The sit-downs inaugurated a period of

organizational innovation

second in magnitude and significance

only to the 1910s. Though the

13. See Paul W. Litchfield, Industrial

Voyage (New York, 1954), 120, 128-31, 183-86;

Allen, House of Goodyear, 166-75.

14. "Outline of the Goodyear Flying

Squadron Training Course," H. L. Matti to

Hugh Allen, Dec. 28, 1933, Goodyear

Archives, Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company,

Akron, Ohio.

15. See Daniel Nelson, "The Company

Union Movement, A Reexamination," Busi-

ness History Review, LVI (Autumn, 1982), 335-57.

16. Compare John D. House, "Birth

of a Union," (microfilm, Ohio Historical Socie-

ty, 1981), 19, and "A History of

Goodyear," Unpublished MS, Goodyear Archives, 336.

Also see W. W. Thompson, "History

of the Labor Movement in Akron, Ohio," CI0 Pa-

pers, National and International,

Catholic University.

17. House, "Birth of a Union,"

34-38.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 13

sit-down technique was associated with

the Rubber Workers, most

Goodyear employees who sat down had no

formal ties with either

the URW or the Assembly.18 In

essence, they repudiated both

groups. Their actions created what in

effect were two new organiza-

tions: a militant, streamlined version

of the Industrial Assembly that

opposed the strike and a militant CIO

union that sustained it. The

ensuing conflict was, above all, a

struggle between these groups for

the allegiance of the Goodyear labor

force.

Initially the more promising of the new

organizations was that of

the non-strikers. By late 1935 the

Industrial Assembly was largely in-

operative. Its limited ability to cope

with the conditions of the 1930s,

exemplified by its inability to stop the

return to the eight-hour day,

had undermined its standing and

demoralized its leaders. A former

Assembly representative and 1936 URW

strike leader summarized its

plight when he recalled that it had gone

"as far as it could go."19

The Assembly continued to meet during

the crisis of February 14-17,

but few workers, and probably even fewer

of its leaders, believed

that it could successfuly cope with the

situation. P. W. Chappell, a

Labor Department mediator, reported that

its attempts to take credit

for minor concessions the company made

to the sit-down strikers "in-

flamed workers who felt [the] real

grievance . . . had not been ad-

justed."20 To most

observers the Assembly was a hopeless anachro-

nism. In fact, it lingered for a year

and a half until the Supreme Court

administered the coup de grace in

NLRB v Jones and Laughlin

(1937). But it was moribund, a shell

without substance.

The last Assembly meeting of the strike

period, on February 19,

coincided with the first meeting of the

"non-strikers." The initial im-

petus for the group remains a mystery.

Local 2 officials argued that

"foremen and supervisors,"

operating directly or indirectly at the

bidding of the management, were responsible.21

Several leaders of

the non-strikers were salaried

employees, and company executives

clearly favored the new organization,

but Lyle Carruthers, its head,

vehemently denied any company tie. A

veteran production worker,

Carruthers asserted the non-strikers

were "not connected with the

company in any way. Piece workers . . .

are running this entirely."22

18. Nelson, "Origins of the

Sit-Down Era," 211.

19. Interview with C. L. Skinner, April

23, 1976; Also see "Annual Report, Seven-

teenth Goodyear Industrial Assembly,

1935-1936," National Labor Relations Board Pa-

pers, National Archives RG 25, Box 1878,

No. 1578, cases 8-R-184, 8-C-378.

20. Chappell to Kerwin, Feb. 18, 1936,

FMCS File 182/1010.

21. United Rubber Worker, I

(April, 1936), 2.

22. Akron Times Press, Feb. 22,

1936

14 OHIO HISTORY

John House, Local 2 president, probably

came closest to the truth

when he charged that a combination of

plant supervisors and Indus-

trial Assembly leaders had created the

non-strikers.23 Whatever the

exact circumstances of its birth, the

group had a substantial follow-

ing. Chappell asserted that 12,000

Goodyear employees, 80 percent of

the total, backed the non-strikers, but

his estimate lumped all neutral

and uncommitted workers in the anti-strike

camp.24 Non-striker

meetings typically attracted 3500 or

more enthusiasts and there were

many other sympathizers. No one doubted

that non-strikers sub-

stantially outnumbered strikers in the

early stages of the dispute.25 A

vote at any time during February 1936

probably would have given

the non-strikers an overwhelming

victory.

Contemporary accounts suggest that

non-strikers were typically

middle-aged, veteran employees who had

little to gain and much to

lose from the strike. Candidates in the

previous Industrial Assembly

election, who played leading roles in

the organization, were men in

their late 30s and early 40s.

Ninety-five percent had five or more

years of service; their ties to Goodyear

antedated the Depression.26

Non-strikers often boasted of their

superior experience, dedication

and loyalty. They were the heart of

Goodyear.27

Age and experience were not the only

characteristics that distin-

guished the non-strikers. Regardless of

their backgrounds, non-

strikers were men and women of

utilitarian views and middle-class

pretensions. Their overriding concern

was steady work at a high

wage. Their goals were largely

external-home ownership, material

comforts, and standing in the community.28

For years Goodyear had

satisfied these desires. When it failed

to do so in the early 1930s,

many of these individuals turned to the

union, but only briefly. By

late 1935 they had become disillusioned

with the URW. For long-

service workers the company's decision

to move from four six-hour

shifts, the work-sharing expedient of

the Depression years, to three

eight-hour shifts signified a return to

normality. Through the long

Depression period their earnings had

been severely reduced, in part

23. Akron Beacon Journal,Feb. 22,

1936.

24. Chappell to Kerwin, March 21, 1936,

FMCS File 182/1010.

25. Powers Hapgood reported to John L.

Lewis that the strikers had only a "hand

full [sic] of adherents." Quoted in

Melvyn Dubofsky, "Not so Turbulent Years: Another

Look at the American 1930's," Amerikastudien,

Vol. 24, (1979), 16.

26. Wingfoot Clan, 24 (Oct. 2,

1935), 3-7; 24 (March 27, 1935), 1, 3. Goodyear employ-

ees were overwhelmingly native-born.

Ethnic and racial distinctions were unimportant.

27. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb.

24, 1936; Akron Times Press, Feb. 28, 1936.

28. This description is based on Daniel

Nelson, "The Leadership of the United

Rubber Workers, 1933-42," Detroit

in Perspective, 5 (Spring, 1981), 25.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 15

because of the six-hour day. By

eliminating fourth-shift men hired

during the expansion of 1935, the

company proposed to increase their

incomes by one-third or more. To protest

that change seemed irra-

tional, to strike against it

inconceivable. Non-strikers were captive to

their expectations. For the first two

weeks of the strike they, not the

union militants, posed the greatest

threat of violence.

The non-strikers made their presence

known quickly. On February

19 several hundred men jammed city hall,

demanding police protec-

tion for workers entering the plant.

When Mayor Lee D. Shroy and

Police Chief Frank Boss urged patience

and calm, they responded

with jeers and catcalls. If there was no

agreement in twenty-four

hours, their spokesman warned, they

would ask the Governor to call

out the National Guard. Many

non-strikers volunteered to serve as

special deputies.29 The group

then moved to a nearby high school

auditorium to elect representatives and

make plans. By that time

there were 1400 in the crowd. On

February 20 they returned to the

high school, angrier than ever.

"Throughout the meeting," a jour-

nalist reported, "leaders attempted

to quiet the rising resentment of

the crowd, insisting that violence was

unnecessary."30 As the crowd

grew, Carruthers and other non-striker

leaders decided to move the

meeting to the Akron Armory, a larger

facility. When National Guard

officials refused to open the Armory,

Carruthers lost control.

'Let's take it,' the workers shouted,

and a general rush began for the

doors. A cheering section of nearly 200

shouted derision at Mayor ...

Schroy and Sheriff Jim Flower.

Leaders brandished placards bearing such

sentiments as 'it's up to you to

protect us, Mr. Mayor.' 'We have the

right to work.' 'Down with mob rule'

and 'We work, you strike.'

A petition directed to both officials

and demanding protection for the

company and the non-strikers was

circlated in the crowd as it swept down

Mill Street.31

After breaking into the Armory, the

throng filled the 3,000-seat

building to overflowing and non-striker

leaders began an unruly se-

quel to the earlier meeting. Summoning

public officials for interroga-

tion, the non-strikers pressed for

immediate action. "'We demand

that you do your duty and see to it that

we are returned to our jobs,'

one man shouted. His assertion that 'if

you don't we will' was wildly

29. Akron Times Press, Feb. 20,

1936.

30. Ibid., Feb. 21, 1936

31. Ibid.

16 OHIO HISTORY

applauded."32 The mayor

and the sheriff demurred, however,

when the militants demanded to be

deputized.

For the next four days the non-strikers

reassembled daily at the

Armory to devise strategy and to

intimidate public officials. On Feb-

ruary 21 they perfected their

organization; Carruthers selected fifty

men, including ten captains, who

"will be ready to go help Sheriff

Flower or city police . . . and will

round up non-strikers when any un-

expected meeting is called.33 Later

he appointed three committees

that "separated the non-strikers

into mobile units."34 The non-

strikers also discussed credit

arrangements with local merchants. At

the end of the session they joined in

loud choruses of "Let Me Call

You Sweetheart," "I Want a

Girl," and other songs.35 On February

22 Carruthers counseled patience and

cautioned against any act that

might discredit the non-strikers. To his

relief, news of the injunction

against mass picketing arrived during

the meeting. The men ad-

journed in high spirits, believing that

local officials would now have

to aid them. Another overflow meeting on

February 23 disavowed

any intention of attacking the picket

line.36 Entertainment and group

singing replaced the fiery speeches of a

few days before. On Febru-

ary 24, the day before the sheriff was

to enforce the injunction,

Carruthers announced that no more mass

meetings were planned.

The men left the Armory with every

expectation of returning to their

jobs the next day.37

In the meantime, a second group of

non-strikers was organizing in a

somewhat different fashion. When pickets

closed the Goodyear

complex on February 18, between 600 and

1000 employees remained

in the factories. They included

President Litchfield and other top

officials, who stayed to dramatize their

contempt for the strikers, and

a large contingent of loyal production

workers. Soon they were

trapped. The pickets did not prevent

them from leaving, but they

could not abandon their posts without

appearing to surrender to the

strikers. After a week, Litchfield and

the executives left to direct the

strike resistance from a downtown hotel,

but most of the "captives"

remained for the duration of the dispute.

The company provided

cots, meals, mail and telephone service,

and paid them their regular

wages, but there were hardships. The

absence of barbers, beauti-

32. Ibid.

33. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb.

22, 1936.

34. Akron Times Press, Feb. 23,

1936.

35. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb.

22, 1936.

36. Ibid., Feb. 24, 1936

37. Chappell to Kerwin, Feb. 24, 1936,

FMCS File 182/1010.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 17

cians and liquor bothered some workers.

(Women workers were re-

ported to be near tears as they wondered

what to do about facials,

manicures, and hair waves.)38 Inactivity

was a universal affliction.

Since there was little or no work for

most of the inmates, athletic ac-

tivity, cards, and reading became their

preoccupations. On Sundays

they held impromptu religious services

under the direction of A. C.

Horrocks, head of Goodyear's eductional

programs. Altogether it

was a "hectic existence . . . but

not a difficult one to take."39 Like

their compatriots on the outside, they

were aggressive, unyielding,

and not a little self-righteous.

Horrocks captured their outlook in his

February 28 sermon:

We have built an industrial leadership

that is second to none, and.... it

stands out as a city built upon a hill.

We are going on to still greater things

because we have a well founded belief in

ourselves, in the people with

whom we work, in that coming of the

soul, often referred to as our Goodyear

spirit.. . 40

Despite their numbers, leadership and

commitment, the non-

strikers faced serious, ultimately

insurmountable obstacles. First and

most obvious was the problem of allegiance.

The non-strikers had

abandoned their fellow employees at a

critical juncture. In an era of

heightened class sensitivity, this was

no small matter. To many non-

strikers, the memory of the company's

pre-Depression record and

the union's erratic 1933-36 performance

was more than sufficient to al-

leviate any qualms about their actions.

To them, the strike was a des-

perate, irresponsible, and largely

leaderless gamble, not the heroic

struggle of the Levinson, McKenny, and

Pesotta accounts.41 But for

other non-strikers the problem of

allegiance was increasingly trouble-

some. Rubber Workers' officials,

unionists in other industries, news-

paper reporters and even, on occasion,

company spokesmen treated

the dispute as a labor-management

conflict. Obviously the non-

strikers were not managers. By the

latter stages of the dispute they

were less certain about their loyalties.

Probably few of them became

union supporters during the strike;

many, nevertheless, were weaned

38. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb.

22, 1936.

39. Ibid.

40. Akron Times Press, Feb. 24,

1936.

41. The more active non-strikers

continued to oppose the URW after the strike.

Operating though several small but

vigorous organizations, they were a constant irritant.

In an August 1937 NLRB election, 3193

Goodyear employees voted against the URW.

Akron Beacon Journal, August 25, 1937.

18 OHIO HISTORY

from their instinctive, pragmatic

identification with the Goodyear

management.

Second was the problem of leadership, a

more serious matter.

Who was in charge of the anti-strike

forces, non-strikers or company

executives? Initially the non-strikers

played the leading role. Thanks

to the Industrial Assembly, they counted

in their ranks most of the

Goodyear workers with leadership

experience. They organized with-

out difficulty and demonstrated their

political sophistication in deal-

ing with public officials. From February

19 to February 24 they were

the most important force in the strike;

thereafter their influence

waned. Like the Industrial Assembly

representatives, the non-

strikers were never wholly independent.

They had substantial re-

sources but nothing like those of the

executives. Gradually, perhaps

inevitably, they fell under the

company's sway. Litchfield's emer-

gence from the plant on February 25

symbolized this shift. Goodyear

executives tried to preserve the

non-strikers role, but without great

conviction or success. In the days after

the injunction fiasco, Car-

ruthers and his associates devoted most

of their energies to fruitless

appeals for state intervention. By early

March they were reduced to a

peripheral role in the conflict.

Finally, there was the problem of

morale. Having deferred to com-

pany officials, most non-strikers lost

interest in the day to day prog-

ress of the dispute, though not in the

outcome. Carruthers cautioned

against this possibility but was

powerless to avert it. When negotia-

tions broke down in mid-March, the

non-strikers tried to regain the

initiative, but were again thwarted. As

P. W. Chappell had surmised,

the strike was in essence a contest

between union members and non-

strikers. By mid-March the former had

triumphed; only the details

remained to be settled.

URW Militancy

The transformation of Local 2, and to a

lesser degree the URW,

was the critical development of the

strike period. The Local entered

the conflict with little support and

little prospect of success. It

emerged a larger and stronger

organization; more importantly, it ac-

quired the shared experiences and

leadership skills that sustained it

in the difficult years ahead. Before the

strike the union was only one

of several groups contending for the

employees' favor; afterward it

occupied an established niche, whatever

its actual strength or influ-

ence. By most measures the strike was a

modest union victory. By

this gauge it was an unquestioned

triumph. The conflict gave the lo-

Goodyear Strike of 1936 19

cal (and the international, which was

almost exclusively an Akron or-

ganization in 1936) a degree of

legitimacy in the eyes of Goodyear and

Akron workers that it had not enjoyed

before and had no immediate

prospect of acquiring.

By early 1936 Local 2 had declined to a

hard core of 500-600 dues-

paying members, men and women who in

many respects were indis-

tinguishable from the non-strikers. The

men were nearly all veteran

employees.42 John House, the

president, had worked at Goodyear

since 1925. Ralph Turner, the

vice-president, had started in 1919,

and Everett G. White, the

secretary-treasurer, in 1920. Other union

officials had similar backgrounds. They

also had had leadership op-

portunities: House had served in the

"flying squadron" and the In-

dustrial Assembly; Turner and Charles

Skinner, a prominent commit-

teeman, had been "speakers" of

the Assembly; Tracy Douglas,

another prominent committeeman, had been

the key figure in the

"senate" during and after

World War I. A few of these men also had

had trade union experience, as members

of the United Mine Workers

in particular.43 A profile of

rank and file union members would proba-

bly reveal considerably less seniority.

On the whole, however, Local

2, like the non-strikers, was an

organization of middle-aged individu-

als who had substantial experience and

responsibilities.

The distinguishing characteristic of

union activists, and probably

Local 2 members generally, was their

sensitivity to managerial au-

thoritarianism.44 In mass

production facilities like the Goodyear

complex, the quest for efficiency was

unrelenting and changes in work

techniques and assignments were continuous.

In return for their coop-

eration, workers received the highest

wages in American industry.45

Union activists shared the values,

ambitions, and aspirations of oth-

er workers, but were more alert to

issues of personal freedom. Their

recollections repeatedly emphasize this

point.46 In the 1920s, when

42. A committeeman's notebook listing

560 union members in a major department

indicates that 64 percent of the male

union members had ten years service and 88 per-

cent preceded the Depression. Only 13

percent of the female members had ten years

service; 40 percent had been employed

before 1930. NLRB Records, Box 347, case

8-C-378.

43. Nelson, "Leadership of the

United Rubber Workers," 24.

44. Ibid., 25. See also Dubofsky,

"'Not so Turbulent Years,'" 16-17; Robert H.

Zieger, "Memory Speaks:

Observations on Personal History and Working Class Cul-

ture," Maryland Historian, 8

(Fall, 1977), 2-9.

45. Federal Housing Administration,

"Akron, Ohio Housing Market Analysis,"

Nov. 1938, 109-10; Akron Beacon

Journal, July 13, 1937; U.S. Department of Labor,

"Wages in the Rubber Manufacturing

Industry, August, 1942," Bureau of Labor Statis-

tics Bulletin, No. 737 (Washington, D.C., 1943).

46. Nelson, "Leadership of the

United Rubber Workers," 25.

20 OHIO HISTORY

changes in production methods were most

rapid, they were quies-

cent, if unhappy. Many turned to the

Industrial Assembly, but the

Assembly, successful in many areas, was

powerless to deal with the

fundamental issue. By the 1930s these

individuals had become de-

termined opponents of the status quo in

the plant.

These attitudes were reflected in the

operation of Local 2. Union

activists did not risk their careers to

create a new dictatorship.

Leaders, they believed, should be

spokesmen rather than decision

makers. The men they selected were

articulate and personable; they

"spoke well." Many had high

school diplomas.47 They were also in-

different to personal gain. Only House

served the local through the

1930s, and none of the Local 2

executives sought or served in other

union offices. Their colleagues and

successors were men of similar

outlook. Local 2 became a rank and file

enterprise, committed to the

well-being and independence of the

individual.

The six-hour dispute added a new group

to the union ranks, the

low-seniority workers. These men were

younger and less experi-

enced; they had not worked at Goodyear

in the 1920s and were less

alert to the issue of managerial power,

except in the special way it af-

fected them. The joining of old and

young, veteran and novice,

proved a potent combination. It created

a strike organization, main-

tained the picket line, and rallied a

growing number of uncommitted

employees to the union cause. In the

course of the dispute the local's

ranks grew tenfold. By mid-March the

union had become a power in

Goodyear and in the industry.48

The creative tension that infused the

local union in early 1936 was

evident in many ways. It was

unmistakable at the tumultuous meeting

of February 17, when Local 2 leaders

condemned the management's

arbitrary behavior and sit-down

participants emphasized their eco-

nomic plight.49 It was

apparent a week later, when union sympathiz-

ers of all descriptions rallied to

thwart the sheriff's effort to disperse

the pickets.50 It reappeared

on numerous other occasions. On Febru-

ary 24 House, confronting a sheriff's

deputy, asserted in mock inno-

cence that he had "no

responsibility at all" for the presence of the

men or their actions. An unsuspecting

and literal-minded striker

47. House, "Birth of a Union";

Interview with John D. House, April 4, 1972; Inter-

view with Ralph Turner, May 10, 1976;

Interview with Charles L. Skinner, April 23, 1976.

48. Membership did not drop below 5000

again until the 1960s. Local 2 Member-

ship Records, Local 2 Papers, Akron,

Ohio.

49. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb.

18, 1936.

50. This statement is literally true.

House recalls the many characters who mobi-

lized on Market Street in "Birth of

a Union," 34-35.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 21

nodded his assent. We have no leader, he

told the officer. "We're

here as individuals."51

Chappell summarized the workers' position

when he reported that the "union

officials lacked control over their

men .... These workers, not all

organization-minded, had joined

the union merely as an aid in the fight

for their jobs [but] now that

they had the plant down and the

authorities on the run they had no

intention of surrendering any ground

gained."52 By late February

the alliance of committed veterans and

newcomers had bested the

non-strikers' organizations and won the

grudging respect of the man-

agement. The question that remained was

whether it could translate

the union's new power into an enhanced

role in the plant.

Two critical incidents illustrated the

union's situation. The first, on

February 28, was an outgrowth of a

strike settlement plan proposed

by Edward F. McGrady, the Assistant U.S.

Secretary of Labor. Af-

ter the sheriffs rebuff on February 25,

city officials, with the help of

the local Congressman, prevailed upon

Labor Secretary Frances Per-

kins to dispatch McGrady.53 McGrady

found Litchfield utterly un-

cooperative and prepared to leave.54

As a final gesture, however, he

proposed a compromise plan: an immediate

end to the strike, the

reinstatement of all strikers, and the

arbitration of differences be-

tween the company and the union.55 After

a day of consultation, the

union negotiators, including

International President S. H. Dalrymple

and Vice-President Thomas F. Burns,

accepted the plan. They be-

lieved that Litchfield would reject it

and had no expectation of an

immediate end to the strike. Their

action was a public relations ges-

ture.

At an impromptu meeting at the Local 2

hall that evening, Dalrym-

ple announced the committee's action and

called for a membership

ballot on the plan. As he explained the

arbitration proposal, there

were shouts of "No! No! No!"

He continued, only to be interrupted

again.56 A reporter described

the next moments:

51. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb. 25, 1936.

52. Chappell to Kerwin, March 21, 1936,

FMCS File 182/1010.

53. Akron Times Press, Feb. 26,

1936.

54. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb. 27, 28, 1936; Akron Times Press, Feb. 27,

28, 1936;

"Transcript of Telephone

Conversation with Mr. Chappell," Feb. 28, 1936, FMCS File

182/1010. McGrady was perceived as a

pro-union demagogue. W. R. Murphy to J. W.

Thomas, Feb. 27, 1936, Firestone

Archives Firestone Tire and Rubber Company,

Akron, Ohio.

55. Akron Times Press, Feb. 28,

1936.

56. "There was an instant outburst

of indignation, everybody talking at once."

Pesotta, Bread Upon the Waters, 201.

22 OHIO HISTORY

A storm of dissension rose powerfully

from every corner of the hall.... A

big man shoved forward and the crowd

surged after him.

'I'd like to know what the hell we

walked out that night to freeze for?' he

demanded. A great shout shook the hall.

Another rose: 'I don't see why it should

be necessary to go back to work

before the arbitration is ended.' he

said.

William Carney, a Plant 1 tire worker

who had emerged as a spokes-

man for the most militant of the union

newcomers, stepped forward to

shouts of "take the microphone,

Bill!"57 Carney opposed the Mc-

Grady plan and called for a postponement

of the vote. Burns sought

to defend the committee's action, only

to be shouted down.

'If that's all we are going to get, why

did we got out in the first place?' a

heated member shouted.

'We want a special meeting to discuss

the question. We don't want to vote

now,' voices from the floor cried out.

John House . . . said a few words for

the proposals. "Although I favor the

plan, remember it is your decision that

is final,' he said.

Then he took an informal vote on the

question of beginning balloting imme-

diately. It appeared to be defeated.

Another union official announced that

Powers Hapgood, one of the

corps of CIO advisors who were aiding

the URW leaders, would

speak for the committee's action.

The announcement did not pacify the

crowd.

A demand that William Carney . . . be

given the floor soon grew so loud

that instead of allowing Hapgood the

floor, a vote was taken to see which

would speak. When Carney won, Dalrymple

stepped from the inner office

and declared the meeting over.58

Realizing the problems their gesture had

caused, URW officials

immediately dropped the McGrady Plan.

The strike continued, its

leaders chastened and wary.

The second incident occurred a week

later and nearly eliminated

the gains of the previous two weeks. After

the sheriff's failure to

break the picket line, the non-strikers

had devoted their energies to

political intimidation. In frequent

communications with the governor,

sheriff, mayor, and city council, they

warned of reprisals if "law and

order" were not restored. Schroy

and the council members were

most vulnerable to this pressure.59

The non-strikers' minimal de-

57. Akron Times Press, Feb. 29,

1936.

58. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb. 29, 1936.

59. Akron Beacon Journal, March 3, 1936; Akron Times Press, March 4, 1936;

Chappell to Kerwin, March 21, 1936, FMCS

File 182/1010.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 23

mand was that the rude shelters the

pickets had erected at the plant

gates be removed. The mayor could hardly

deny this request; the

huts violated city ordinances and were

highly visible reminders of

the strikers' defiance of authority.

Schroy conferred with House and

C. M. O'Harrah, the Local 2 picket

captain, several times during the

week of March 2-6. They promised to

remove the shelters "as soon

as possible." In fact they did

nothing. O'Harrah probably did not

even inform the pickets of his promise

to remove the huts.60 By

March 6, Schroy's impatience was

exhausted. Believing his credibil-

ity and political future were at stake,

he ordered sanitation workers to

remove the huts. At 7 a.m. on Saturday,

March 7, five trucks and 56

workers accompanied by 75 police arrived

to dispose of the huts.

They destroyed four of the shanties

before the surprised and sleepy

pickets sounded the alarm.

Ed Heinke, a reporter for the Akron

Times Press and an eyewitness,

described the response:

Pickets poured out of the nearby union

headquarters. Hurry calls were sent

out for reinforcements...

A moment later, at the General [Tire]

plant . . . the word went down the

production line that trouble had

developed at Goodyear.

The men dropped their tools, shut the

presses and rushed from the

building ....

Union men in the Goodrich plant were

told to stand by. Men in the union

headquarters at Firestone rushed to the

scene....

Down over Newton Street hill machine

loads of strike sympathizers, with

hatless, coatless men hanging to the

running boards, raced toward the strike

scene. Picket reinforcements filled the

streets.... 61

Within minutes two or three thousand men

jammed the street, forc-

ing the police and sanitation men away

from the huts. In the scuffles

that ensued, two policemen were injured.

Outraged, Mayor Schroy

first ordered a renewed assault, then

hesitated when the police

warned that they would have to go back

shooting.62 Several hours

later he met House and O'Harah. Schroy

agreed to postpone any ac-

tion if the union acted immediately to

remove all huts from major

thoroughfares. The union leaders acceded

to his ultimatum and the

shanties disappeared. Henceforth,

pickets sat in cars near the gates

60. Adolph Germer Diary, March 6, 1936,

Adolph Germer Papers, State Historical

Society of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin.

61. Akron Times Press, March 7,

1936.

62. Brophy recalled a striker showing

him a gun and confiding, "We've passed the

word to the police that we'll give them

as good as they send." Brophy, A Miner's Life,

264.

24 OHIO HISTORY

and city officials made no effort to

interfere.63 By Sunday the crisis

had passed.

To many observers these incidents were

serious indictments of the

strike leaders. The union hall debacle

and the near riot of March 7

underlined the unionists'

"inexperience" and the precarious hold of

the union officers on their charges.

Chappell believed that only out-

side direction of the strike, perhaps

the participation of John L. Lew-

is himself, would avert disaster.64

Fortunately, he might have

added, experienced advisors were

available to provide the element

of professionalism that the URW officers

lacked. By late February

they had made the Goodyear contest the "first

CIO strike."

The CIO Role

The CIO role in the Goodyear strike was

one of the conflict's most

celebrated features. Supposedly it

inaugurated the labor alliance as a

militant organization, a successful

alternative to the AFL and an all

but irresistible force in American

industrial affairs.65 This was what

Lewis, John Brophy, his lieutenant, and

their representatives in Ak-

ron intended.66 In

retrospect, however, a somewhat different picture

emerges. Brophy hinted at this view when

he noted that "our people

found that one of their most demanding

jobs was to restrain the local

talent.. . ."67 Rather than

inciting the strikers to greater militancy,

as Levinson and other contemporary

analysts suggested (and as CIO

critics charged), or guiding the Rubber

Workers, as Chappell antic-

ipated, CIO representatives played

little direct role in the conduct of

the strike or the negotiations. Their

contributions fulfilled neither

the hopes nor the fears of the other

participants.

The Goodyear strike was an opportunity

for the CIO to outflank the

AFL and to establish the credibility of

the Lewis committee with in-

dustrial employees in other industries.

In the first of these endeavors

the CIO had an immense advantage; the

Rubber Workers had al-

ready opted for industrial unionism and

had aligned itself with Lew-

is. Following visits by Adolph Germer on

February 22-23 and by

63. Akron Times Press, March 7,

8, 1936; Akron Beacon Journal, March 9, 1936.

64. Chappell to Kerwin, March 21, 1936;

"Long Distance Telephone Conversation

Between H. L. Kerwin and P. W. Chappell,

March 17, 1936," FMCS File 182/1010.

65. See Levinson, Labor On the March,

146-47.

66. Brophy, A Miner's Life, 263; Akron

Beacon Journal, Feb. 25, 26, 1936; CI0 Exec-

utive Committee Minutes, Dec. 9, 1935,

"Report by Director for Meeting of Feb. 21, 1936,

April 14, 1936," Katherine P.

Ellickson Papers, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

67. Brophy, A Miner's Life, 263;

Lorin Lee Cary, "Institutionalized Conservatism in

the Early C.I.O.: Adolph Germer, A Case

Study." Labor History, 13 (Fall, 1972), 488-91.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 25

Brophy on February 23, the CIO threw all

its resources into the

Goodyear cause.68 Germer, who

returned on February 24, worked

behind the scenes with the strike

leaders; Powers Hapgood, who

arrived on February 26, served as the

principal CIO liaison with the

public; and Rose Pesotta of ILGWU, who

also arrived on February

26, maintained contacts with the

pickets. Brophy made three short

visits, Leo Krzycki of the Amalgamated

Clothing Workers and Ben

Schafer of the Oil Workers remained for

longer periods, and envoys

from the Clothing Workers, Mine Workers,

and Auto Workers spoke

at rallies and meetings. The CIO also

contributed $3000 to the strike

fund. By contrast, the AFL role was

meager. Green contributed

$1000 and had agreed to a speaking

appearance when the strike

ended.69 Apart from

Akron-area functionaries who provided assis-

tance through the Central Labor Union,

the only AFL organizer to

appear was Coleman Claherty, Green's

former Akron representative.

Claherty toured the picket line one

Sunday afternoon. No strike

leader greeted him.

Although generally successful in working

with strike leaders, Ger-

mer and his colleagues had some difficulty

impressing the strikers

themselves. For all their ability and

good intentions, the CIO offi-

cials were outsiders, unfamiliar with

the industry and community.

They and their resources were welcome,

but on the strikers' terms.

The gulf between them and the strikers

was epitomized by their

physical isolation; they lived at the

Portage Hotel in downtown

Akron and spent their free moments in

each other's company. Their

late-night gatherings at the Portage bar

attracted reporters, curious

citizens, and company informants.70

It is not surprising that they

found Vice-President Burns, a Chicopee

Falls, Massachusetts-

resident also housed at the Portage, the

most accessible and cooper-

ative of the URW officials.

From the time of their arrival, the CIO

advisors handled the strik-

ers' press and public relations. In the

hectic early days of the strike,

Germer undertook this job with minimal

assistance. He wrote press

releases, met with reporters, and

coordinated the publicity work of

the other CIO representatives.

Presumably it was he who decided

that the strikers should rely on the

radio to communicate with sym-

pathizers and potential allies.

Dalrymple, Burns, Frank Grillo, the In-

68. Brophy, A Miner's Life, 263

69. United Rubber Worker, I

(April, 1936), 16.

70. Germer reports many such gatherings

in his diary. Also see Akron Beacon Jour-

nal, Feb. 28, 1936.

26 OHIO HISTORY

ternational secretary-treasurer, and

Local 2 officials made frequent

broadcasts; their statements, with only

two exceptions between Feb-

ruary 26 and March 10, were products of

Germer's facile pen.71

Thereafter, McAllister Coleman, a labor

journalist Germer brought

from New York to relieve the burden,

composed both press releases

and broadcast scripts. The climactic

episode in the union radio blitz

was a nine-and-a-half hour all-night

broadcast on March 16-17,

when union leaders feared a vigilante

attack on the picket line. Grillo

and Coleman coordinated the program,

which featured amateur

entertainment, recorded music, news from

the picket line, and pro-

strike editorials.72 Unionists

agreed that it was a remarkable

achievement.

The less imaginative Goodyear public

relations staff was hopelessly

outclassed. Masters of newspaper

advertising, they stumbled badly

when they sought to employ the new

technology of industrial con-

flict. Litchfield's broadcasts confused

rather than edified his listen-

ers, and those of other executives and

non-strikers lacked the profes-

sional quality of the union appeals.

Even union critics agreed that the

strikers won the battle of the air

waves.73 The only unpleasant note

for the CIO was personal rather than

professional. After his all-night

stint, Coleman began a five-day

alcoholic binge that ended his use-

fulness and ultimately led to his

dismissal.74

CIO representatives were equally

effective in public appearances.

Germer, Hapgood, Pesotta and others made

daily inspection tours of

the picket lines, often pausing for

impromptu rallies.75 They also par-

ticipated in countless meetings at the

union hall and in a series of

mass rallies at the Armory. Beginning on

March 3 the union spon-

sored daily programs in a theater near

the strike area. Pesotta re-

cruited amateur musical and theatrical

groups for these sessions and

led the strikers in labor songs and

parodies of popular tunes. Hap-

good specialized in inspirational talks

to the strikers, their families,

and allies. His dapper appearance,

measured tone, and educated air

confounded popular notions of the labor

agitator. Local journalists

devoted far more attention to him than

his role in the strike organiza-

71. Germer Diary, Feb. 26-March 10,

1936.

72. Akron Beacon Journal, March,

17, 1936; Akron Times Press, March 17, 1936.

73. Akron Beacon Journal, March 23,

1936; Pesotta, Bread Upon the Waters, 221-22;

United Rubber Worker, I (April, 1936), 2.

74. Germer Diary, March 17-21, 1936.

75. Pesotta recalled that "we all

took turns speaking from the union sound truck. Au-

diences would gather quickly whenever

the truck stopped. The loud speaker never lost

its novelty for them." Pesotta, Bread

Upon the Waters, 206-07.

|

Goodyear Strike of 1936 27 |

|

|

|

tion warranted. Goodyear officials seemed to despise him more than the other CIO advisors, perhaps because of his bourgeois demeanor and disarming manner.76 After March 4 Germer devoted most of his time to the Goodyear negotiations. Aware of his outsider status, he proceeded cautiously. He was a "servant" or "first mate" to "Captain Dalrymple."77 His job was to counsel, not to dictate. Still, he found it difficult not to be- come more deeply involved. His assignment was to see that the strike did not end in disaster. Despite the union's gains since February 25, that possibility remained. And given the URW's leaders and their method of operating, it was likely to persist until an agreement was concluded. Fearful that a prolonged stalemate would work against the union, Germer increasingly pressured the strike leaders for a set- tlement, almost any settlement that would give the union a base at Goodyear.

76. Akron Times Press, March 10, 1936; Akron Beacon Journal, March 10, 1936; L. A. Hurley to E. S. Cowdrick, July 23, 1936, U.S. Senate, "Violations of Free Speech and Rights of Labor," Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Committee on Education and Labor, 76 Cong., 1 Sess. (Washington, D.C., 1939). 16898. 77. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb. 28, 1936. |

28 OHIO HISTORY

Germer began to take a more active role

in early March. Secret talks

between March 4-7 produced the first

Goodyear concessions: an of-

fer to reinstate the strikers, retain

the six-hour day, and consult union

representatives before making policy

changes. The company also

agreed to reduce the number of

"flying squadron" members.78

However, in a March 9 radio broadcast

President Litchfield seemed

to suggest a different and less generous

settlement. Believing they

had been "double-crossed," the

union negotiators decided to make

their aims public.79 In a

broadcast on March 10 House asked for

clarification of the Goodyear proposals

and for action on the URW

demand for termination of financial

assistance to the Industrial As-

sembly.80 But when the

negotiators met on March 12, the Goodyear

representatives refused to consider

House's demands. They insisted

on a ratification vote.81

After considerable discussion and pressure

from Germer, the union negotiators

grudgingly agreed to present the

company's proposals to the strikers at

an Armory meeting on Satur-

day, March 14. As Germer reported to

Brophy, he "hoped [the] men

would accept [the] company's proposition

and then build up their

union."82

As Saturday approached there were

ominous signs of rank and file

discontent. To many strikers the

proposal seemed more like a back to

work order than a union victory. The

union negotiators, led by

House, made no attempt to hide their

feelings. On Thursday night

Germer, Krzycki, Schafer, and Burns

discussed the possibility of re-

jection, though Germer remained hopeful.

On Friday evening the

strike rally at the theater turned into

an anti-settlement protest led by

Carney.83 After that, even

Germer saw that there was little hope for

ratification.84

On Saturday morning the strike leaders

and Germer met to com-

plete their plans for the afternoon.

They decided that House would

open the meeting and call on George

Hull, a member of the negotiat-

ing committee, to read the Goodyear

proposal. When Hull finished,

House would ask Dalrymple to explain the

procedure for amending

the company plan and open the meeting to

discussion. They agreed

78. Chappell to Kerwin, March 12, 1936,

FMCS File 182/1010; Germer Diary, March

4-9, 1936; Akron Times Press, March

8, 1936; Akron Beacon Journal, March 9, 1936.

79. Chappell to Kerwin, March 21, 1936;

FMCS File 182/1010.

80. Akron Times Press, March 11,

1936; Akron Beacon Journal, March 11, 1936.

81. Akron Times Press, March 12,

1936; Akron Beacon Journal, March 12, 1936.

82. Germer Diary, March 13, 1936.

83. Akron Beacon Journal, March

14, 1936

84. Germer Diary, March 13, 1936.

Goodyear Strike of 1936 29

that there would be a secret ballot on

the amended Goodyear offer.

At that point W. H. Ricketts, a Local 2

activist, appeared. Ricketts

claimed to represent a group of pickets

and announced that he would

introduce a series of detailed

amendments. They were the work of

James Keller, the local Communist Party

leader, who had been meet-

ing with a handful of strikers.85 The

amendments included the de-

mands that the union negotiators had

raised on March 12 and that

the Goodyear representatives had refused

to consider. House and

other union executives expressed

sympathy toward the proposal.

Germer, however, was dismayed: "I

had already prepared a substi-

tute resolution without definite

instructions to [the] negotiating com-

mittee but this fellow [Ricketts] also

House preferred to tie the com-

mittee down to specific points. I told

them I thought it was poor

strategy but I couldn't get them to see

it."86

By 2:00 the Armory overflowed with 4000

or more strikers. Few at-

tempted to disguise their

dissatisfaction with the settlement. A news-

paperman who eluded the union guards

reported that it was "pretty

plain from the start that the crowd

wasn't going to accept the compa-

ny's peace plan."87 When

a malfunction of the public address sys-

tem delayed the start of the meeting,

House led the group in singing.

The refrain of a popular labor song,

"No, No, a Thousand Times

No," provided dissidents with a

theme.88 When House finally

stepped to the microphone to begin the

meeting, he was greeted by

chants of "No! No! No!"89

After a brief introductory statement,

House turned to Hull. The events of the

next few minutes eliminated

the last small hope of an immediate

settlement. Germer recalled:

[Hull] gave [a] brief but very

unsatisfactory explanation of what hap-

pened.... [He] did not read [the]

company proposition.... Then House

'explained' some more. Dalrymple got no

chance to read his statement.

After Ricket [sic] read his resolution

House took it upon himself to change

the program. He called Burns and

Dalrymple into a huddle at the table and

had Burns say 'the negotiating committee

accepts the resolution as part of its

report

. . .'

I walked upon the stage and told Burns

he blundered. He resented the

suggestion, so I went to the hotel in

disgust. I considered leaving.90

85. McKenny, Industrial Valley, 353-55;

Daily Worker, March 13, 14, 23, 1936. For a

candid assessment of the Communists'

limited role, see John Williamson, "Akron, A

New Chapter in American Labor

History," Communist, XV (May, 1936), 424-25.

86. Germer Diary, March 14, 1936.

87. Akron Times Press, March 15,

1936.

88. Akron Times Press, March 15,

1936; Interview with John D. House, April 1973;

Pesotta, Bread Upon the Waters, 219.

89. Akron Times Press, March 14,

1936.

90. Germer Diary, March 14, 1936; Akron

Time Press, March 15, 1936.

30 OHIO HISTORY

House explained that the Ricketts

amendments meant a return to the

picket line, but no one spoke up for the

Goodyear plan. By a show of

hands Local 2 members adopted the

amended report. C. M. O'Har-

rah had the last word: "I'm telling

you right now," he exclaimed,

"this strike has just started.

We're going out to hold that picket

line.' "91

P. W. Chappell summarized the views of

Germer and the other

outsiders when he wrote that House

"allowed the meeting to get

away from him."92 House

would likely have replied that the meeting

was never his to control. What to

Chappell and Germer was poor

management was to URW leaders the rough

and tumble of a demo-

cratic union. Roberts Rules might be

observed in the breech, but

the principle of consensus was

maintained. On March 14 that meant

the strikers would continue to press

their demands. As Germer had

anticipated, their decision was costly.

Within hours former Akron

Mayor C. Nelson Sparks announced the

formation of the Law and

Order League. The strike was once more

in jeopardy.

Community Response

From the beginning of the Goodyear

strike the elements of an anti-

strike coalition were present in Akron.

Two of them, the Goodyear

management and the non-strikers, require

little additional comment.

Goodyear officials had consistently

opposed the URW since 1933;

they would continue to do so until 1941.

The non-strikers, their zeal

and possibly their numbers somewhat

diminished, were also deter-

mined opponents.93 A third

element was a substantial minority of lo-

cal citizens not directly involved in

the conflict. Farmers, profession-

als, and upper-income residents of all

backgrounds were deeply

suspicious of the URW and the strikers.94

In most cases their anxiety

did not arise from hostility to unions

or collective bargaining per se

but from fear of their possible

consequences. Anything that threat-

ened the prospect of economic recovery

became the object of their

enmity. For several years they viewed

the URW with misgivings. Aft-

er February 18 most of them probably saw

Local 2 as a threat.

Finally, there were local government

figures, pragmatic in outlook

91. Akron Times Press, March 15

1936.

92. Chappell to Kerwin, March 21, 1936,

FMCS File 182/1010.

93. See Roberts, Rubber Workers, for

post-strike activities.

94. Jones, Life, Liberty and

Property, 143-236. For a recent effort to cast such an align-

ment in broader, theoretical terms, see

Edward Greer, Big Steel (New York, 1979).

Goodyear Strike of 1936 31

sensitive to interest group pressures

and wary of any move that would

expose themselves to electoral

retaliation. The mayor, sheriff, prose-

cutor, and most of the thirteen

councilmen needed Rubber Workers'

votes to be elected and dared not appear

indifferent to the strikers'

interests. In addition, the mayor was

supposedly miffed at Goodyear

executives for not supporting his

election campaign in 1935.95 The

URW was by no means devoid of political

influence. Yet the strikers

were vulnerable on the critical economic

growth issue. The one point

on which company and union, pro-strike

and anti-strike forces,

agreed was the desirability of

expansion. Any threat to the city's fu-

ture prosperity would provoke a reaction

that cut across other lines.

Though the strikers subscribed to the

growth ideal like everyone

else, their actions invited criticism.

By closing the plant they reduced

spending and profits and increased

unemployment and uncertainty.

In the minds of many people this was

tantamount to opposing growth.

No politician could-or would-tolerate an

anti-growth movement.

As long as the strike lasted there was

danger that these groups

would coalesce into an anti-strike

movement. The sheriff's attempt to

implement the injunction had been a

close call for the strikers. Only

the prospect of violence had deterred

the mayor and governor.96

The police confrontation of March 7 also

might have served as an

anti-strike catalyst. The March 14 vote

created a new crisis, the most

serious of all. By that time it was

widely acknowledged that the inter-

ests of the community demanded an end to

the dispute, and to many

people rejection of the company's offer

was a rejection of the city as

well. Political neutrality became more

difficult.

In the meantime, anti-union activists

and Goodyear representatives

had formulated a plan to break the

strike. Non-strikers supposedly

originated it, while Litchfield and the

heads of other rubber compa-

nies provided financial support.97 Sheriff

Flower may have been in-

volved in the discussions, though he was

determined not to appear

as the leader of the effort. Schroy,

whose relations with Goodyear,

the non-strikers, and Flower had been

less than happy since the in-

junction confrontation, stoutly refused

any tie. The non-strikers then

turned to local businessmen.98 They

found a willing leader in former

Mayor Sparks, an outspoken community

booster who had headed a

"Citizens Committee" of

prominent businessmen during the first two

95.

Ibid., 107.

96. Akron Beacon Journal, Feb.

25, 1936; Akron Times Press, Feb. 25, 1936.

97. U.S. Senate Hearings, 29,

51-52.

98. Germer Diary, March 12, 1936.

32 OHIO HISTORY

weeks of the strike.99 From

their discussions emerged the Law and

Order League. By March 14 Sparks was

ready to act. When word

came of the strikers' decision, Sparks

and his allies implemented

their plan. Goodyear issued a statement

withdrawing its concessions

and Sparks announced the formation of

the League. His objective,

he said, was to aid law enforcement

officials when the plant reo-

pened. If they refused to cooperate, the

League would act alone.100

Statements by Litchfield and Sparks on

Sunday, March 15, em-

phasized the economic growth issue. In

refusing Chappell's last min-

ute request for an interim agreement,

Litchfield maintained that he