Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

LEWIS L. GOULD

Chocolate Eclair or Mandarin

Manipulator? William McKinley, the

Spanish-American War, and the

Philippines: A Review Essay

The Spanish War: An American

Epic-1898. By G.J.A. O'Toole. (New

York: W. W. Norton, 1984. 447p.;

photographs, notes, bibliogra-

phy, index. $19.95.)

Sitting in Darkness: Americans in the

Philippines. By David Haward

Bain. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984.

464p.; notes, bibliography,

index, photographs. $24.95.)

The Spanish-American War and the

Philippine Insurrection that

followed were significant historical

events that continue to attract

scholarly and popular authors. G.J.A.

O'Toole sees the war with

Spain as "a national rite of

passage, transforming a former colony into

a world power" (p. 18). His book

examines the background of the

conflict, but concentrates most heavily

on the military events in the

spring and summer of 1898. David Haward

Bain uses the life and ca-

reer of Frederick Funston, and

especially his capture of the Filipino

leader Emilio Aguinaldo in 1901, as a

basis for exploring the Ameri-

can relationship with the Philippines

since George Dewey's victory at

Manila Bay on May 1, 1898.

Though the amount of space which each

book devotes to Pres-

ident William McKinley varies with their

contrasting purposes,

O'Toole and Bain both attempt to

interpret and analyze the twenty-

Lewis L. Gould is Eugene C. Barker

Centennial Professor of American History at the

University of Texas at Austin.

|

Chocolate Eclair or Mandarin Manipulator? 183 |

|

|

|

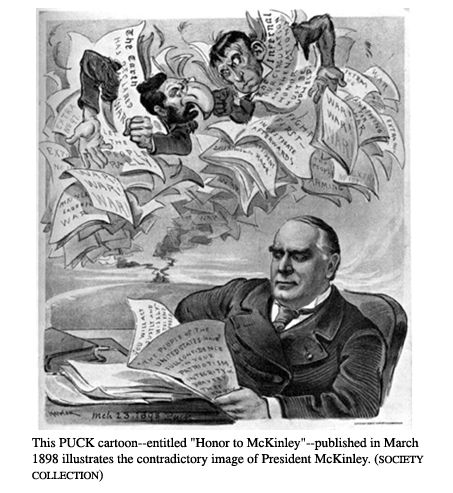

fifth president as diplomat and war leader. Their conclusions about him reflect the negative emphasis of most writing on McKinley, but they criticize him in mutually inconsistent ways. O'Toole follows what might be called the traditional "chocolate eclair" approach, arguing as Theodore Roosevelt reportedly said, that the president was weak and had "no more backbone than a chocolate eclair."1 Bain, on the other hand, depicts McKinley as a "mandarin" who controlled events for his own imperial designs (p. 56).

1. Edmund Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (New York, 1979), 610. |

184 OHIO HISTORY

O'Toole extends an historiographical

tradition that is more than six

decades old. After the First World War,

the belief grew among

scholars that the war with Spain should

have been avoided. McKin-

ley's alleged submission to the tide of

popular hysteria in the spring

of 1898 became a cliche of American

history. It ran through the pages

of Walter Millis, The Martial Spirit (1931),

Ernest May, Imperial De-

mocracy (1961), and even David F. Trask, The War with Spain

in 1898

(1981), the most recent and impressive

one-volume history of the war.

This point of view has withstood the

challenges of Margaret Leech,

H. Wayne Morgan, Paul Holbo, and others,

and persists in most

American History texts to this time.2

O'Toole does not list Wayne Morgan's

book among his sources, nor

has he consulted President McKinley's

own papers or the equally im-

portant collection of the president's

secretary, George B. Cortelyou.

He has done some interesting digging

into the military intelligence

side of the conflict, but he does not

integrate these findings into a

fresh look at how the president managed

the fighting. And there are

a number of careless slips. Enrique

Dupuy de Lome was a minister,

not an ambassador (p. 65), William

Jennings Bryan was nominated by

the Democrats in July 1896, not June (p.

66), and McKinley spent sev-

en terms in the House of

Representatives, not two (p. 84).

More important, however, O'Toole simply

slides McKinley away

from the center of events, and installs

Theodore Roosevelt in particu-

lar and other proponents of war with

Spain in general into the spot-

light. Diplomatic and military policy in

1897-1898, in O'Toole's ver-

sion, appears to have been the product

of autonomous forces apart

from the president himself. Thus,

Roosevelt, a sub-Cabinet official

and relatively minor military figure in

these years, gets equal space

and more with the actual architect of

American policy. Had O'Toole

looked at Courtelyou's diary in the

Library of Congress, the Cortel-

you Papers, and McKinley's own records,

he would have had a

much sounder grasp of how the war came.

The central issue in the onset of

hostilities in April 1898 is whether

Spain had capitulated to American

demands about Cuba before

McKinley sent his message to Congress on

April 11. O'Toole claims,

as do many other writers, that Madrid

asked for an armistice. In fact,

the Spanish sought a suspension of

hostilities on April 9. The distinc-

tion is crucial. A Spanish armistice

would have involved political rec-

2. Joseph A. Fry, "William McKinley

and the Coming of the Spanish-American

War: A Study of the Besmirching and

Redemption of an Historical Image," Diplomatic

History, 3(1979),

77-97.

Chocolate Eclair or Mandarin

Manipulator? 185

ognition of the Cuban rebels; a

suspension of hostilities merely would

give Spain a temporary military respite.

It did not include agreement

to the American demand for Cuban

independence, and it left the de-

cision about the resumption of the

fighting to the Spanish command-

er on the island. Getting this key issue

in the dispute right is decisive

for a judgment about whether Spain gave

in, whether they wanted a

settlement and Cuban independence, and

whether McKinley's

message on Cuba was justified or not.

O'Toole has the matter wrong

on almost every aspect of this question,

and it tilts his whole narrative

against McKinley in a false way.

The Spanish War is more an historical pastiche than a fresh treat-

ment of its subject. It adds little that

is new to a comprehension of

the war's significance, and it achieves

its narrative effects by dodging

the hard historical questions and

misrepresenting McKinley's presi-

dency.

Sitting in Darkness belongs in a newer tradition of Spanish-

American War scholarship about McKinley.

In the early 1960s, histo-

rians critical of American foreign

policy, most notably William A.

Williams, Walter LaFeber, and Thomas

McCormick, described

McKinley as a sort of imperialistic evil

genius. According to these and

other writers, McKinley managed events,

manipulated men, and was

an adroit agent of American capitalism

as it sought overseas markets.

A popular writer named Walter Karp

adopted this view and he, in

turn, convinced Bain of its accuracy.3

Bain has large pretensions for his

study, and his handling of Mc-

Kinley is a relatively small part of his

sprawling narrative. His text fol-

lows Funston from his Kansas origins

through a stint in Cuba and on

to the Philippines between 1898 and

1901. Bain himself and some

friends actually went to the Philippines

in 1982, and physically dupli-

cated Funston's route in Northern Luzon.

The book speaks of histor-

ical events as they relate to the

current crisis in the Philippines, and it

is as much an indictment of the rule of

Ferdinand Marcos now as a

critique of American policy between 1898

and 1902.

At first glance it would seem that Bain

has been more thorough

than O'Toole. Wayne Morgan's book is

present, as are the McKinley

papers, although Bain did not use the

Cortelyou Papers either. Some

careless errors are troublesome. Once

again, de Lome is an ambassa-

3. Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: An

Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860-

1898 (Ithaca, New York, 1963), 327-33; Walter Karp, The

Politics of War: The Story of

Two Wars Which Altered Forever the

Political Life of the American Republic (1890- 1920)

(New York, 1979), 69-95; Bain, Sitting

in Darkness, 423 at 56.

186 OHIO HISTORY

dor, and Spain declares an armistice in

April 1898. Bain confuses

Thomas Collier Platt (R.-N.Y.) with

Orville H. Platt (R.-Conn.), and

he has George Dewey (1837-1917) serving

with Stephen Decatur

(1779-1820). Presumably he means David

Farragut (1801-1870).

Finally, William Howard Taft never

served as Vice President (Bain,

pp. 58, 61, 68, 393).

There are, however, more serious errors

that impair the credibility

of Bain's narrative. He has McKinley in

December 1897, April 1898,

and February 1899 delivering messages to

Congress in person. On the

last occasion, as the Senate debated the

peace treaty with Spain,

Bain says that "William McKinley

appeared in the hall. He stood

ready to address them" (p. 78). As

every American history student

should learn in a survey course, no

president addressed Congress in

person from Thomas Jefferson's

abandonment of the practice in 1801

through Woodrow Wilson's resumption of

it in 1913. It might be pos-

sible to attribute this blunder to

simple ignorance. A non-historian

raised in an era when chief executives

regularly appear before joint

sessions of Congress might

understandably slip on a point of fact in

this way. Since McKinley did send

messages to Congress in Decem-

ber 1897 and April 1898, Bain's

quotations from these documents as

presidential speeches are careless

errors, not fatal ones.

In the case of McKinley's alleged

appearance before the Senate in

person on February 6, 1899, no such

excuses can be made. The event

never happened, and McKinley said

nothing. Bain proceeds to quote

words that the president supposedly

uttered. Checking Bain's notes,

one finds a reference to a volume of

McKinley's published speeches.

The cited pages reveal that the

president did in fact say the words

quoted, but he delivered them not in

February 1899 but six months

later. And they were not addressed to

senators but to the Tenth

Pennsylvania Regiment of Volunteers in

Pittsburgh on August 28,

1899. Bain's notes give no clue to what

he has done with McKinley's

August 1899 remarks.4

Two possible interpretations exist for

this strange bit of legerde-

main. Bain may have been inexcusably

careless and sloppy in his

handling of the evidence. Or he may have

deliberately manipulated

the information to enhance his argument.

When an author breaks the

trust that must exist with the reader,

and does so either willfully or

carelessly, confidence in the rest of

his narrative vanishes. If he can

misuse a McKinley speech either out of

ignorance or to further his po-

4. Speeches and Addresses of William

McKinley From March 1, 1897 to May 30, 1900

(New York, 1900), 216; Bain, Sitting

in Darkness, 78, 425-26.

Chocolate Eclair or Mandarin

Manipulator? 187

lemical goals, then why should the

reports of his conversations in

the Philippines, quotations from primary

sources, or conclusions

about historical events be trusted at

all. It would be interesting to

check all of Bain's sources to see what

else he may have done, but

surely it is not the task of every

reader to see that an author is accu-

rate and trustworthy. That is the

responsibility of Bain and his pub-

lisher, and on this point they have

failed.

If historical scholarship is cumulative,

then it is time that writers

on William McKinley, the

Spanish-American War, and the Philippine

Insurrection recognize their obligation

to deal with the sources about

these subjects fairly and fully. That

does not mean, of course, that

their conclusions must be favorable to

the twenty-fifth president.

The importance of McKinley's tenure and

its consequences for the

nation insure that debate will continue.

If the United States had not

intervened in Cuba in 1898, would the

war there have persisted, re-

quiring American action at a later date

under more difficult circum-

stances? Some scholars, especially

Philip S. Foner, assert that the

Cuban rebels had virtually achieved a

victory over Spain by April

1898. The Spanish, however, did not

admit defeat and resolved to

continue the struggle to preserve Cuba

as part of their nation. In the

case of the Philippines, if the United

States had sailed away after the

war ended, the outcome for the

inhabitants of the archipelago

would likely have meant Japanese,

German, or other imperial overse-

ers, not national independence.5

The broad tends of writing about

McKinley and his times that

these books represent will persist. The

alternative thesis-that Mc-

Kinley was the first modern president

with a varied record of success

and failure-may even in time prevail. In

fairness to McKinley, how-

ever, everyone should concede that he

made policy between 1897

and 1901, not Theodore Roosevelt, and

that it is wrong to view his

administration as if he was not in

charge. Whether he was eclair,

mandarin, or modern president, he is

entitled to have his deeds

rendered accurately, and the

significance of his presidency analyzed

fairly and honestly. McKinley asked no

more from history when he

was alive and he deserves no less now.

5. Philip S. Foner, The

Spanish-Cuban-American War and the Birth of American Im-

perialism, 1895-1902 (2 vols., New York and London, 1972), I, 248-49.

LEWIS L. GOULD

Chocolate Eclair or Mandarin

Manipulator? William McKinley, the

Spanish-American War, and the

Philippines: A Review Essay

The Spanish War: An American

Epic-1898. By G.J.A. O'Toole. (New

York: W. W. Norton, 1984. 447p.;

photographs, notes, bibliogra-

phy, index. $19.95.)

Sitting in Darkness: Americans in the

Philippines. By David Haward

Bain. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984.

464p.; notes, bibliography,

index, photographs. $24.95.)

The Spanish-American War and the

Philippine Insurrection that

followed were significant historical

events that continue to attract

scholarly and popular authors. G.J.A.

O'Toole sees the war with

Spain as "a national rite of

passage, transforming a former colony into

a world power" (p. 18). His book

examines the background of the

conflict, but concentrates most heavily

on the military events in the

spring and summer of 1898. David Haward

Bain uses the life and ca-

reer of Frederick Funston, and

especially his capture of the Filipino

leader Emilio Aguinaldo in 1901, as a

basis for exploring the Ameri-

can relationship with the Philippines

since George Dewey's victory at

Manila Bay on May 1, 1898.

Though the amount of space which each

book devotes to Pres-

ident William McKinley varies with their

contrasting purposes,

O'Toole and Bain both attempt to

interpret and analyze the twenty-

Lewis L. Gould is Eugene C. Barker

Centennial Professor of American History at the

University of Texas at Austin.

(614) 297-2300