Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

LOUIS W. POTTS

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist

On August 3, 1787, the parson of the

Congregational Church in

Ipswich (now Hamilton) Massachusetts

returned to his hamlet. He

calculated he had traversed 885 miles in

his one-horse sulky in the

past two months and considered it

"one of the most interesting and

agreeable journies I ever made in my

life. It had in every view been

prosperous but in many respects

infinitely exceeded my expecta-

tions."1 Somewhat the

polymath, he could cite among his feats the

reestablishment of acquaintances with

President Ezra Stiles and oth-

er divines at Yale, the addition of many

new plants for his preeminent

botanical collection, and a visit to the

wondrous zoological exhibits

of Charles Willson Peale. The crowning

deed was not that he had

gained proselytes for his faith, but

rather that he was on the verge of

sealing the largest public contract yet

negotiated in the United States.

He had successfully bid for more than

four million acres of the pub-

lic domain. Further, according to some

later historians (if not contem-

poraries), he had made significant

contributions to two major docu-

ments being drafted in the early summer

of 1787: the Northwest

Ordinance molded by the Congress under

the faltering Articles of

Confederation and the Constitution

evolving in the Grand Conven-

tion. How much credit should this

extraordinary clergyman be giv-

en? What were his tactics and strategies

as an agent? Edward Chan-

ning offered this appraisal of Manasseh

Cutler: "He took not

unkindly to the devious methods that

were necessary in those days

Louis W. Potts is Associate Professor of

History at University of Missouri-Kansas

City.

1. August 3, 1787, Journey Book II-B,

Manasseh Cutler Collection, Northwestern

University. Hereafter citations to these

manuscripts will be listed MCC. For a critique

of the published version of Cutler's papers see Lee

Nathaniel Newcomer, "Manasseh

Cutler's Writings: A note on Editorial

Practice," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47

(June, 1960), 88-101. Newcomer noted:

"At the hands of his editors Manasseh Cutler

has been under-humanized as well as

over-politicized. Because of the liberties which

they took with his writings, a more

nearly complete and better balanced portrait of

Cutler must depend upon the manuscripts rather than

upon the edited version pro-

duced by his grandchildren."

102 OHIO HISTORY

to put a contract through Congress, and

the perusal of his journal in-

spires one with the thought that

lobbying is by no means a modern

art."2

There is little in Cutler's biographical

background to indicate

where or how he perfected his social and

political skills. His Puritan

ancestors had come to New England in

1634, but his own parents, at

the time of his birth in 1742, had

achieved station as substantial

farmers and prominent church leaders in

Killingly, Connecticut, close

to the northeastern border with Rhode

Island. Among inherited

and acquired characteristics he would

utilize were his physical coun-

tenance and deportment. As he matured,

he carried himself with un-

derstated self-confidence. Though he

dressed in black, he was no

somber cleric. He might be revered for

his position as a religious au-

thority, but his style was that of a

sociable and learned counselor. A

pen portrait left by a grandson depicts

Cutler's appearance as "un-

commonly prepossessing - a florid

complexion; a good-humored ex-

pression of countenance; a

full-proportioned, well-set frame of body.

He was remarkably slow and deliberate in

all his motions. He pos-

sessed a natural dignity of manners, in

which there was no air of stiff-

ness or reserve, but on the contrary the

utmost frankness and cordial-

ity."3 This joie de

vivre is communicated in Peale's portrait of Cutler,

now housed at the Historical Society of

Pennsylvania. Whether in

New England taverns, New York City

boarding houses, or Philadel-

phia garden parties, Cutler proved an

entertaining, instructive and

trustful colleague. No matter what

section or cultural background his

companions came from, they found Cutler

infectious.

Cutler's intellectual talents were

identified and reinforced by the

Reverend Aaron Brown who tutored the

youth and sent him to Yale.

Following graduation in 1765, Cutler

continued his studies in order to

attain a Master of Arts in 1768. As his

mind was attracted by a wide

spectrum of subjects from the natural

sciences to religion, so Manas-

seh also manifested restlessness as a

young adult. Perhaps like his

biblical namesake, Manasseh felt he had

not gained a substantial

family blessing to call him home to

Killingly. After stints as school

teacher, storekeeper, lawyer, and even

venturing into the whaling in-

dustry, the peripatetic Cutler found a

stabilizing influence in the Rev-

2. Edward A. Channing, A History of

the United States (New York, 1935), III:542.

3. Nathan N. Withington, "Manasseh

Cutler and the Ordinance of 1787," New Eng-

land Magazine, 24 (July, 1901), pp.494-96; Robert Elliott Brown, Manasseh

Cutler and

the Settlement of Ohio, 1788 (Marietta, 1938), 8; Benjamin Wadsworth, A

Discourse,

Delivered July 30, 1823 in Hamilton

on the internment of the Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LLD

(Andover, 1823).

|

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 103 |

|

Ipswich, Massachusetts, home of Manasseh Cutler. (SOCIETY COLLECTIONS) erend Thomas Balch of Dedham, Massachusetts. In 1766 he wed Mary (Polly) Balch. Two years later, he determined to study divinity under his father-in-law. He hoped his "inclination" would be "ever so profitable, or promising."4 After a lengthy search for a pulpit of his own, he had settled as pastor in Ipswich, a post he would retain for fifty-two years. Reportedly he became an ordinary preacher, not a profound theo- logian. In 1771 membership in his parish was sixty-eight adults; in 1814 the total was seventy-three. He found kindred spirits through- out the region. "The New England of which Cutler was a part was full of learned clergymen like him, ministers who combined deep

4. William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkins Cutler (eds.), Life, Journals and Corre- spondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D. (Cincinnati, 1888), I, 17-20; Janice Gold- smith Peelsifer, "The Cutlers of Hamilton," Essex Institute Historical Collections, 107 (October, 1971), 336-39. The honorary degree of Doctor of Laws was conferred by Yale on Cutler in September, 1789, but the diploma was not issued until 1791. J. L. Kinsley to E. M. Stone, June 13, 1839, General Collection, MCC, I. |

104 OHIO HISTORY

learning and piety with public service

and liberal views." As the

youngest of three ministers in Ipswich

parishes, Cutler deferred to

his superiors on theological matters and

proved equally agreeable to

his peers among the community leaders.

At his home, located next to

the meeting house, he hosted parish and

town meetings for the farm-

ing community of approximately 800. A

somewhat paltry income, plus

a family that would ultimately number

seven children, channeled

Cutler's endeavors into supplemental

fields. The parsonage was filled

with boarders: pupils from the North

Shore's best families studying

bookkeeping or navigation, or preparing

for college. His third-floor

study was littered with sermons,

mounting piles of daybooks, and a

melange of personal correspondence. He

accumulated a barometer,

thermometer, microscope, telescope,

spyglasses and a celestial globe.

Such diverse interests would draw

criticism. Later a younger minister

from Salem, and a political antagonist,

would opine, "Dr. Cutler . . .

has no talent in writing of any kind,

but he has been one of the busy

men, who has been in untried paths ...

He has published upon

Botany without science, taught languages

without skill in them, pro-

fessed navigation without numbers or

experience, and overlooked all

talents in his profession . . . He has

succeeded in promoting the

utmost contentment with the prevalent

habits of life without ambi-

tion."5

As early as December 1774 the parson had

committed himself to

the patriot cause as he joined townsmen

in military drills. In 1775

when news arrived of fighting at

Lexington and Concord, Cutler led a

party of Ipswich men to aid in the seige

at Cambridge. The early

years of the War for Independence found

him periodically serving as

a chaplain to Massachusetts' regiments.

Doubtless he was happy to

comply with his commission which

directed, "You are therefore

carefully and diligently to inculcate in

the minds of the Soldiers of

said Regiment, as well by Example as

Precept, the Duties of Religion

and Morality, and a fervent Love of

their Country ... "6 Diary ac-

counts of his service are replete with

commaraderie he shared with

the officers. In the latter stages of

the war he apprenticed himself to

medical training under a neighborhood

physician. He sought to aug-

5. Henry Steele Commager, The Empire

of Reason (Garden City, 1977), 26; Peelsifer,

351-52.

6. Cutler and Cutler (eds.), Life, I:

59-60. Indicative of Cutler's attitude was his rec-

ord of being bombarded by the British at Newport:

"Stood by the Marquis [Lafay-

ette] when a cannon ball just passed us. Was pleased

with his firmness, but found I

had nothing to boast of my own, and as I

had no business in danger concluded to stay

no longer lest I should happen to pay

too dear for my curiosity." Ibid, I:69.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 105

ment his income amidst rampant

inflation. The war experience vastly

expanded Cutler's horizons and

competencies. From military ac-

quaintances he developed innumerable

personal contacts in his home

region as well as farther afield. These

connections would later yield

him leadership posts in the efforts to

settle New England veterans in

Ohio and in a Congressional seat for

himself (1801-1805). From travels

with the army he cultivated an urge to

comprehend New England

botany. Soon after the war he was

classifying more than 350 species

of New England flora according to the

Linnean system and ascending

Mount Washington to ascertain its correct

height.7

Such feats indicated his ambition

transcended his provincial par-

ish. His pursuits also developed his

bent to examine new challenges,

to pursue his goals tenaciously, and to

master and coordinate details.

These organizational skills would be

integral to his style. Later in life

he would counsel his son on the

attributes of an agent: "Indeed, as I

have remarked to you before, you cannot

[be?] content, as an agent, if

you delay and are not punctual in

everything." He sermonized on

"the ominous consequences of having

too many irons in the fire at

the same time," and pointedly noted

"never suffer public employ-

ment to injure your private

interest."8 He was a most active member

in the American Philosophical Society

and the American Academy

of Arts and Sciences where he frequently

contributed papers on as-

tronomical and botanical subjects.

Cutler was one of those "Enlight-

ened" clergymen who saw a prophecy

coming true in the emerging

American republic. One of his preserved

sermons captures this

worldview: "the bright day of

science, virtue, pure religion, and free

government shall pervade the western

hemisphere." He was a her-

ald that "a new Empire should be

called into being."9

A favorite classical quotation of Cutler

was from Virgil: "Happy is

the man who can recognize the course of

things." He recognized the

opportunity to become a pivotal force-to

play the role of philo-

sophe-in his nation's history which

came in the quest to open the

7. Withington, "Cutler,"

494-97; John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of

Jefferson (Ames, Iowa, 1984), 255, notes: "In the ensuing

years this gentleman 'so mild

in his manner and so ardent in his

researches'; as Samuel L. Mitchell described Cut-

ler, continued to gather materials for a

flora of New England, although hampered con-

siderably by the lack of suitable

reference works. He corresponded widely in both

Europe and America ... On a cold snowy

day in January 1812, however, fire broke out

in his study while he was at dinner.

Many of the botanical manuscripts were de-

stroyed; Cutler, now seventy years old,

sorrowfully abandoned his long-cherished

dream of publishing a botany of New

England."

8. Manasseh Cutler to [Ephraim Cutler],

January 12, 1802, Correspondence, MCC.

9. Cutler and Cutler (eds.) Life, II:

439-50.

106 OHIO HISTORY

Ohio country. In the midst of the

critical 1780s, "Ohio fever" in-

fected him. An enterprising businessman,

enlightened expansionist,

botanical explorer and republican

advocate, Cutler's private and

public aspirations could be best

realized by transplanting New Eng-

land communities to the northwest bank

of the Ohio River.10 In 1783

his interests in diseases and migration

had caused him to scrutinize

the Ipswich census. He observed that

folk leaving the town "consist

chiefly of the young healthy and robust

on whom population princi-

ply depends . . . The newer settlements

must therefore greatly ex-

ceed the old, in populations, in proportion

to the number of inhabit-

ants."11 Herein was the

theme of the robust settler which Cutler

would repeat in the following decade. He

argued that systematic set-

tlement of the backcountry by covenanted

communities of industri-

ous patriots would insure growth of the

Federal republic.

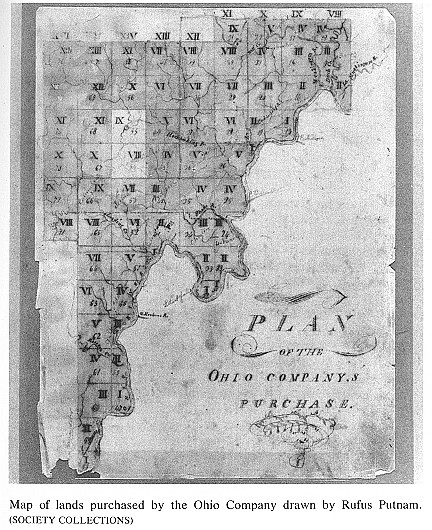

The Ohio Company of Associates was

formed in the spring of 1786

at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern in Boston

by veterans of the War for

Independence. The objective of this

venture, initiated in eight coun-

ties of Massachusetts, was "to

raise a fund in continental certificates,

for the sole purpose, and to be

appropriated to the entire use of

purchasing LANDS in the western

territory (belonging to the United

States) for the benefit of the company

and to promote a settlement in

that country."12 Each

investor (who could purchase a maximum of

five shares) would contribute $1,000 in

certificates plus $10 in gold or

silver for each share purchased. The

former funds would purchase

lands across the Ohio; the latter was

"for defraying the expenses of

those persons employed as agents in

purchasing the lands and other

contingent charges that may arise in the

prosecution of the busi-

ness." It was even anticipated that

interest yielded from the potential

$1 million fund could assist "those

who may be otherwise unable to

remove themselves" to the new

settlements.

As early as March 24, 1786, Cutler

plunged into the venture. Al-

though handicapped by lack of copies of

the Articles and without

descriptions of the Ohio country, he

solicited subscribers, "some of

them of considerable property,"

inclined to become adventurers.13

10. Brown, "Cutler," 9;

Commager, Empire, 28.

11. Manasseh Cutler to [Edward Cutler?],

February 14, 1783, Correspondence,

MCC; Cutler and Cutler (eds.), Life,

I: 131-34.

12. Articles of the Ohio Company, (Worcester,

1786), 3-4.

13. Manasseh Cutler to Winthrop Sargent,

March 24, 1786, in Cutler and Cutler

(eds.), Life, I:187; "The

Part Taken by Essex County in the Organization and Settle-

ment of the Northwest Territory," Historical

Collections of the Essex Institute, 25 (July-

Sept. 1888), 165-234.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 107

He advocated dissemination of reports of

the fertility and climate of

Ohio via newspapers in his region. Such

accounts would turn his col-

leagues from "emigrating into the

northern frozen deserts" and over-

come "fear of the savages and the

distance from connections." With-

in a month he was predicting he could

recruit eighty shareholders

and thus asserted himself into a policy

making role. He advocated

soliciting only in New England and

co-opting "any men of conse-

quence" who might appear as leaders

of rival "petty companies."14

He was set to emigrate and establish a

number of vegetative experi-

ments on the Ohio River.

On March 8, 1787, while Cutler was home

sick, the Association

held its initial organizational meeting

at Brackett's Tavern in Boston.

Samuel Holden Parsons, Rufus Putnam, and

Manasseh Cutler were

unanimously elected Directors. Winthrop

Sargent was chosen perma-

nent secretary. All would subsequently

own four or five shares in the

venture and act as agents to solicit

subscribers.15 The assignment for

the three directors was to alter

Congressional policy, evinced in the

Land Act of 1785, so that large

corporate bids tendered privately

would prevail over purchases of the

national domain by individuals

in the public market. Putnam, a

celebrated war hero from Massachu-

setts, had been instrumental in

orchestrating soldiers' demands for

land bounties as well as in advocating

westward migration. It later

developed that he temporarily found

interior lands in Maine more at-

tractive. Parsons, another former

brigadier, had negotiated with In-

dians in the Northwest and thus knew the

land firsthand. He was a

leading citizen of Connecticut who

coveted an estate in Ohio.

Sargent, a former major from

Massachusetts and surveyor for New

Hampshire under the Land Ordinance of

1785, would prove well

connected with financiers in New York

City.16 Putnam and Cutler

proved to be complements. As one analyst

put it: "Putnam was a sol-

dier, Cutler was a diplomat; Putnam was

a surveyor, Cutler was a so-

cial engineer . . . Putnam knew and

represented the pressing needs of

the prospective settlers; Cutler was

conspicuous in inaugurating and

14. Same to same, April 20, 1786, Ibid.,

I:189-90.

15. Ohio Company's Purchase, Proprietors

and Holdings [n.d.], Ohio Co., MCC;

Ledger Book A, MCC, p. 97, lists among

seventeen agents responsible for 1,000 shares

the following: Winthrop Sargent 166, M.

Cutler 151, General Parsons 99, General Put-

nam 62. Cutler and Cutler, (eds.), Life,

I, 192. At the time of his death in 1823 Cutler

held title to 2,543 acres in Ohio.

Peelsifer, "The Cutlers," 355.

16. William D. Pattison, Beginnings

of the American Rectangular Land Survey Sys-

tem, 1784-1800 (New York,

1979) 124-33; Archibald Hulbert (ed.), The Records of the

Original Proceedings of the Ohio

Company (Marietta, 1917).

108 OHIO HISTORY

achieving the plan for this

settlement."17 As critical to the success of

the Association was Cutler's

relationship with Sargent. The one pro-

moted the venture among politicians

while the other cultivated capi-

talists. Cutler provided the direction

and rhetoric; Sargent amassed

clout to sustain the venture.

Cutler immediately recognized the

challenge confronting the Ohio

Company in the spring of 1787.

Simultaneously he addressed letters

to his compatriot Sargent and a

Massachusetts delegate, Nathan

Dane. To the former he emphasized that

their venture would prove

enticing to two types of New Englanders:

those who were enterprising

yet troubled that "almost every

kind of business is stagnated here"

and those presently "unable to

obtain a living" as land had been

purchased and improved by prior

generations. Both groups would

purchase federal lands only if the price

were competitive with state

lands. To the latter Cutler pointed out,

"An immediate and great set-

tlement must be an object of consequence

in the [view of Congress,

and settlers from the northern states,

in which this company is made

up, are undoubtedly preferable to those

from the southern states.

They will be men of more robust

constitutions, inured to labor, and

free from the habits of idleness."

Cutler specifically solicited Dane's

"influence in favor of the Company

... so far as is consistent with the

general interest of the Union."18

To both correspondents Cutler em-

phasized that the price of federal lands

must be whittled down to

compete with those offered by the

states. The spirit of emigration

from New England which "never ran

higher" could then be chan-

neled to the northwest, thereby

benefitting the nation.

Cutler kept different accounts of his

activities as they unfolded in

1787. As had become his habit in the

last couple of years, he main-

tained entries routinely in a diary or

almanac. Therein he recorded

his activities such as plantings,

acquaintances such as dining with

Governor Bowdoin, ailments (he suffered

from apparent skin cancer

of his face), observations on the

weather and topics for preaching.

Unfortunately this source is not totally

revealing. For example, it is

barren of entries for the critical

period of May 2 through June 22,

1787, when Cutler was doubtlessly

preparing for his venture south-

ward. Simultaneously he developed two

ledgers: one of the obliga-

tions of the Ohio Company to him as director;

the other of payments

made on behalf of the Associates. A few

conscientious entries serve

17. Brown, "Cutler," 7-8.

18. Cutler to Sargent, March 16, 1787;

Cutler to Nathan Dane, March 16, 1787, Cut-

ler and Cutler (eds.), Life, I:192-95.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 109

as clues as to his approach to his role:

he charged $10 (specie) to at-

tend a three-day directors' meeting in

May in Boston, calculated

travel expenses at $183.30 for his

summer junket to New York and

Philadelphia, and spent $20 for the

autumn's advertisement of Com-

pany lands for sale.19 He

would not gain full reimbursement for these

expenses until 1790. Finally, as an

indication that he sensed momen-

tous events, on June 24 when he departed

Ipswich, he began a loose-

leaf journeybook-actually a pad 3"

x 7". This device permitted him

later to emend his entries. It is clear

that hindsight editing by Cutler

was aimed at enhancing the importance of

events. Yet he did not

seek to inflate his own contributions.

It must also be noted that the

pages covering the events of July 20-27

are in noticeably smaller

script, indicating they were not

contemporary to the other entries.

In early summer it seemed propitious for

the Company to press its

case. In May, Parsons had been

unsuccessful in personally carrying

the Ohio Company's offer to Congress in

New York City. Putnam and

Cutler, believing Parsons had mishandled

the specification of

boundaries, were willing to travel to

Congress if "there is a sufficient

representation for completing our

business." They wrote to Sargent in

New York, "Our principal fears of a

disappointment are that Congress

may dispose of those lands before it will

be in our power to apply for

them.20 If Sargent could not

successfully push the bid of the Ohio

Company, he was instructed to thwart

bids from rivals. Of these

maneuverings Parsons was to be kept

ignorant, and delegates from

Massachusetts were to be kept at arms

length. Among many activities

on June 25, Cutler conversed a half day

with General Putnam about

strategies and tactics. The two

directors probably rehearsed argu-

ments for opening the west: the public

would secure much needed

revenues to pay war debts, the

enterprising Associates hoped for pri-

vate gains in reselling of lands, and

the frontier would be secured by

planting robust communities of veterans.

Putnam and Cutler probably

also analyzed points of resistance

offered in Congress: that the bid

per acre was too low, that some lands

would be reserved for commu-

nal concerns such as education and

religion, and that the company

sought profits in its role as retailer.

Cutler jotted that Putnam and he

19. Ledger Book B, 75-78, Ohio Company,

MCC. Revealingly, he was ultimately

able to charge one half of his summer

trip expenses to the Ohio Company and the bal-

ance to the Scioto Company, as the two

became interwoven in efforts to secure Con-

gressional grants.

20. Putnam and Cutler to Sargent, May

30, 1787, Cutler and Cutler (eds.), Life,

I:196-97.

110 OHIO HISTORY

"Settled the principles on which I

am to contract with Congress for

lands on act of the Ohio Company."21

Cutler's notes indicate that he

purposely amassed more than two

score letters of introduction to

important men. A catalog of these ad-

dresses reveals two key points. First,

Cutler from his departure

planned to visit both New York and

Philadelphia. For the former he

had targeted members of Congress and the

financial community. For

the latter he aimed only at making new

acquaintances among the sci-

entific and religious leaders of the

community. Perhaps he antic-

ipated visiting only the Massachusetts

delegation to the Grand Con-

vention. Perhaps he did not anticipate

the opportunity or need to

lobby on behalf of his Company to

representatives of other re-

gions.22 Second, Cutler's

scientific reputation served as both an en-

tree and a cover for his fundamental

mission. He did, upon occasion,

travel out of his way to visit a number

of curiosities-a steam engine in

Rhode Island, botanical gardens in

Pennsylvania or an apiary in New

Jersey. But such opportunities also

enabled him to pursue his

number-one priority. In the first

setting he was able to solicit sub-

scribers to the Company: in the second

he found a private environ-

ment for open discussions with selected

delegates to the Convention;

in the third he could inquire of George

Morgan of the plans of the

Indiana Company, a contemporary speculation.

In the mixture of

business and pleasure, business came

first.

On his way to New York, Cutler's

itinerary passed through scenic

Middletown, Connecticut. There he paused

for a day and a half to

converse with another company director,

Samuel Holden Parsons,

and to preach twice to a crowded Meeting

House. It was Parsons, on

May 9, who had presented a memorial and

unsuccessfully tried to

overcome Congressional resistance to the

Company's bid.23 Al-

though there might have been previous

feelings that Parsons had

not adequately or sincerely represented

the Company before Con-

gress, Cutler found him convivial and

complaisant. New strategies

devised in Massachusetts were evidently

affirmed. Cutler was re-

21. June 25, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC.

The entry for the following day indicates

an acquisitive undercurrent in Cutler's

motive. After viewing the impressive home of a

Providence brother of the cloth, Parson

Cutler offered the rationalization: "Provi-

dence, all wise in its dispensations,

tho unfathomable by us, has allotted us different

portions of the means of happiness in

this World. We have no ground for complaint

and the only relief is to rejoice in the

happiness of our friends. We then secure to our-

selves a share of what heaven has given

to them, and denyed to us."

22. Frederick D. Stone, "The

Ordinance of 1787," Pennsylvania Magazine of Histo-

ry and Biography, 13 (October, 1889), 318.

23. June 29, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 111

stocked with more letters of

introduction. By the midafternoon of

July 5 Cutler arrived in New York. It

had been an enjoyable jaunt.

His diary, for example, noted that at a

Milford tavern he had drunk

cider with Judge Randal "which made

me a little loquacious & we

settled the nation completely, leaving

only triffles for the Convention

and Congress to adjust." A quick

walk through the city enabled Cut-

ler to reconnoiter. He chose to lodge on

Golden Hill in the Bowery at

the home of Hugh Henderson, a merchant

and former Loyalist who

would own a share in the Ohio Company.

From this base he vigor-

ously pursued his goals. Perhaps with

amusement he noted his alma-

nac's printed maxim for July 5:

"Brains and Heads, not Powder and

Perukes, must support a

government."24

On Friday July 6 he made three

initiatives.25 First he delivered

most of his letters of introduction to

members of Congress before the

morning session commenced. Second,

somewhat unprecedentedly,

at eleven A.M. he was led on to the

floor of Congress, only recently re-

convened on July 4 in the City Hall.

There Colonel Edward Carring-

ton, member from Virginia and chair of

the committee appointed to

develop terms for negotiating land

sales, introduced him to a number

of the members. Cutler seized the

opportunity to make formal appli-

cation "for the purchase of lands

in the western country for the Ohio

Company." He presented a petition,

proposed terms and conditions

for the sale, and exchanged views with

the Committee.26 There was,

however, no formal debate this day on

the Ohio Company offer.

Third, he sought contact with the Board

of Treasury as a means to

bring bureaucratic pressure on the

politicians. Perhaps Cutler, in or-

der to gain assistance, dangled shares

in the Ohio Company in front

of ambitious policymakers; perhaps he

merely convinced statesmen

to invest personal funds in ventures

that could also be portrayed as

patriotic.27 Delegate Nathan

Dane from Massachusetts persuaded

24. July 5, 1787, Diary, MCC.

25. Worthington C. Ford (ed.) Journals

of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789

(Washington, D.C., 1904-1937), 32: 308;

July 6, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC. This entry

is uncharacteristically marred by heavy

interlinations by a thicker pen than that

which made the original entries. As a

result there are some indecipherable words.

26. Members of the Committee included

Edward Carrington (Va.), Rufus King

(Mass.), Nathan Dane (Mass.), James

Madison (Va.), and Egbert Benson (N.Y.). In

July only Dane and Carrington were

present. Pattison, Beginnings, 171.

27. Later listings of Ohio Company

shareholders made by Cutler and Sargent in-

clude Congressmen Edward Carrington (4),

Elbridge Gerry (1), Melancton Smith (1),

and Arthur St. Clair (1); Treasury

officials William Duer (5), Arthur Lee (2), and Eben-

ezer Hazard (1); prominent investors

included banker William Constable (5); lawyer

Alexander Hamilton (5); and hero John

Paul Jones (5). Hulbert (ed.), Ohio Company

Papers, II, 235. Stockholders listed as of February 1, 1796,

differs in small detail from

undated listings found in MCC.

112 OHIO HISTORY

his housemate, James Milligan, the

Treasury Comptroller from

Philadelphia, to dine with Cutler, but

the lobbyist calculatingly ex-

cused himself so he could spend the

evening with several members

of Congress.

Saturday July 7 found the lobbyist and

the Congressional commit-

tee in conference. But for the notation

that he again stated the terms

offered by the Company there is little

comment in Cutler's records;

the Journal of the Continental Congress

makes no mention of Cutler

until July 24. Whenever the Ohio Company

was discussed, between

July 10 and 27, the topic was referred

to as the memorial from General

Parsons.28 Four further sets

of acquaintances were cultivated: Gener-

al Henry Knox, who possessed wide

influence among veterans as

head of the Order of the Cincinnati and

as Secretary of War, was the

resident expert on Indian affairs; Sir

John Temple, who was a social

lion as Counsul General of Great

Britain; Thomas Hutchins, the Ge-

ographer of the United States who knew

the most attractive locations

in the Northwest; and numerous fellow

clergymen. On the sabbath,

perhaps to assure that Providence was on

his side, Cutler attended

three different sermons. These services

were interspersed with meals

with Treasury Board member Arthur Lee

and Ebenezer Hazard who

served both as Treasurer of Congress and

Postmaster General.29 In

sum, Cutler campaigned vigorously on a

wide front.

Monday July 9 looked promising. An early

morning conference

with the congressional committee was

followed by in-depth discus-

sions with Hutchins. Cutler was

convinced that the Company should

locate its purchase on the confluence of

the Muskingum and Ohio.

An afternoon session with the committee

indicated an impasse. Cut-

ler's journeybook noted, "Debated

on terms but were so wide apart

that there appears little prospect of

closing a contract."30 He refused

to be frustrated as he returned to

consult with the Geographer and,

after supper, prevailed on the

Massachusetts' delegation to take him

to their lodgings in Hanover Square for

discussions with several other

members of Congress. The following

morning he again met in confer-

ence with the committee, quickly put in

a sidetrip to discuss obstet-

rics with faculty at Columbia, and made

a crucial dining appoint-

28. Ford (ed.) JCC, 32: 305-46,

376.

29. July 7-8, 1787, Diary, Journeybook

II, MCC.

30. July 9, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC.

This entry is filled with detailed observa-

tions of the physical surroundings in City Hall. Cutler

chose to focus on portraits of

George Washington and other

Revolutionary War heroes. Perhaps he used them as

props in arguing that the Ohio Company

offered a means to make good on public obli-

gations to members of the Continental

Army as well as provide superior defense for the

nation's frontier.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 113

ment.31 The host was William

Duer, secretary to the Board of

Treasury who lived "in the stile of

a Nobleman." Cutler noted that

among beverages available were fifteen

sorts of wine plus cider, por-

ter and several other kinds of strong

beer. He was particularly "de-

ceived" by a glass of

"exceedingly fine" bottled cider. Whatever

the effects of the fare, the topic of

conversation was doubtlessly land

sales. Present around the table were

Samuel Osgood, head of the

Treasury Board, and several other

gentlemen. Cutler, supported by

Sargent and Hazard, could measure his

prospects. His manuscripts

yield a list of members then serving

terms in Congress.32 Notations

were made of those absent. No

indication, however, is made of the

positions for or against the Ohio

Company taken by the twenty-three

delegates thought present. In fact,

during July 1787, attendance

charts indicate that during his initial

stay only fifteen members were

present. In the last week of the month

he was dealing with twenty-

two Congressmen.33

It is at this point that Cutler's

journeybook becomes controversial

and problematic. Two questions are

foremost: 1) What role did Cutler

play in the formulation of the Northwest

Ordinance then being de-

liberated in Congress? 2) Why did he

choose to break negotiation at

this time? The entry for late July 10

records:

As Congress was now engaged in settling

the form of Government for the

Federal Territory, for which a Bill had

been prepared, & a copy sent to me,

with leave to make remarks & propose

amendments, & which I had taken

liberty to remark upon & to propose

several amendments, I thought this the

most favorable opportunity to go on to

Philadelphia. Accordingly, after I had

returned the Bill with my observations

[xx], I set out at 7 o'clock.34

The day after Cutler departed, the

Carrington Committee reported

"An Ordinance for the Government of

the Territory of the United

States North West of the river

Ohio," a revision of a document last

discussed on the floor May 9 two days

before adjournment. This lat-

est draft, containing additions to the

previous bill, was read a second

time on July 12 and passed on July 13.

The Northwest Ordinance,

three years in gestation, thus appears

to have been rather rapidly

31. July 10, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC.

The diary entry for the same date reveals

nothing concerning timing, motive and

intention of the decision to leave New York City

for Philadelphia.

32. N.D., 1787 Diary, MCC.

33. Edmund C. Burnett (ed.), Letters

of Members of the Continental Congress

(Washington, D.C. 1921-1936), VIII: Ivi.

34. July 10, 1787 Diary, MCC, (xx)

indicates two words in the manuscript rendered

illegible due to cross-outs.

114 OHIO HISTORY

born with Dr. Cutler as midwife. It was

adopted by the unanimous

vote of the eight states present. Of the

eighteen members specified in

the final rollcall, only Abraham Yates

voted nay. With visions of rev-

enues pouring in from sales of millions

of acres of the public domain,

the delegates quickly directed the Board

of Treasury to prepare fiscal

plans for the coming year, including

requisitions on the states.35

American politics, not to say American

historiography, has been

the setting for controversy concerning

authorship of the various arti-

cles of the Northwest Ordinance. Most

notoriously debates such as

those among Daniel Webster, Robert

Hayne, and Thomas Hart Ben-

ton in 1830 championed various

statesmen: the latter two credited

Thomas Jefferson while the New England

camp put forward Cutler,

Rufus King, and Nathan Dane.36

In the past century of scholarship

Cutler's contributions have been

highlighted by numerous advocates.37

A number of points found in

Cutler's papers are worthy of emphasis.

First, in those diary entries

and journeybook observations made in the

summer of 1787 Cutler

portrays the establishment of a temporary

government as a piece, in-

tegral but not primary, in his efforts

to bargain successfully with Con-

gress. He spent more time and energy

with those men, in Congress

and out, who were concerned with land

market considerations: price

per acre, credit terms, various

allowances for surveying, bad lands or

plots to be reserved for public uses.

His formal discussions were pri-

marily with the Congressional committee

charged with land sales,

not that assigned development of plans

for western government.38

35. Edmund C. Burnett, The

Continental Congress (New York, 1964), 682-87. Bur-

nett (p. 683) notes "the Rev. Mr.

Cutler appears to have proven himself a past master of

the art of lobbying, and in almost no

time at all was stroking the bristles of all Congress

- that is, of all except Abraham Yates

of New York, and in his case, if Nathan Dane is

to be believed, obstinacy merely sat

stolidly on the stool of non-comprehension."

36. Ray Allen Billington, "The

Historians of the Northwest Ordinance," Illinois

State Historical Society, Journal, XL

(December, 1947) 397-413; Joseph Grady Smoot,

"Freedom's Early Ring: The

Northwest Ordinance and the American Union," Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Kentucky,

1964, pp. 224-64; Dennis Denenberg, "The Miss-

ing Link: New England's Influence on

Early National Educational Policies," New Eng-

land Quarterly, 52 (1979) 219-33. For a subset of this

historiographical conflict see J.

David Griffin, "Historians and the

Sixth Article of the Ordinance of 1787," Ohio His-

tory, 78 (Autumn, 1969), 252-60. Ralph Bertram Harris,

"A Pioneer of the Northwest."

Historical Collections of the Essex

Institute, LXI (July, 1925), 201-16

offers a synopsis

drawn from Cutler's published works.

37. William Frederick Poole, "Dr.

Cutler and the Ordinance of 1787," North Ameri-

can Review, CCLI (April, 1876), 229-65 emphasizes Cutler's role.

Frederick D. Stone,

"The Ordinance of 1787," Pennsylvania

Magazine of History and Biography, 13 (Octo-

ber, 1889), 309-40, minimizes Cutler's

contributions. Newcomer, "Editing," 4, particu-

larly attacks the printed edition of

Cutler's works on this topic.

38. Theodore C. Pease, "The

Ordinance of 1787," Mississippi Valley Historical Re-

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 115

Second, assertions that Cutler was a

prime architect and penman of

the Northwest Ordinance were advanced

only by himself and family

members much after the fact. In the

summer of 1787 Cutler wrote,

when he saw the final terms of the

Ordinance, "It is in a degree new

modeled. The amendments I proposed have

all been made except

one, & that [concerning

Congressional taxation and representation] is

better qualified." However, in

1804, as an embattled Federalist Con-

gressman amidst Republicans in

Washington, Cutler told his son that

he [not Thomas Jefferson nor Nathan Dane

as claimed by most

scholars] was the fountainhead of

Article Six in the Ordinance, that

provision which banned slavery on the

northwest bank of the Ohio

River. A son-in-law in the 1840s and

grandchildren after the Civil

War particularly made this point

emphatically.39 Examination of Cut-

ler's correspondence and diaries fails

to yield any private statements

against slavery. In his later years

Cutler did employ a freed mulatto

couple as domestic servants. It is

incontrovertible that specific contri-

butions made by Cutler were provisions

for public schools, estab-

lishment of a university, and

encouragement of religion. The central

points of the Ordinance had been

evolving within Congressional cir-

cles since at least 1780. Cutler brought

these to fruition.

The question of the timing and nature of

Cutler's trip from Congress

to the Grand Convention is also fraught

with intrigue. By July 10 the

Carrington Committee had been persuaded

to propose that the

Board of Treasury be authorized and

empowered to contract with

the Ohio Company agent for whatever

lands desired. Perhaps Cutler

sensed that the plans concerning western

governance were Congress's

first priority and that an act was

imminent. A tactful respite for him-

self and negotiators across the tables

might prove beneficial. Also a

possible explanation was that Duer and

other speculators had ap-

proached Cutler with propositions to

pool capital and lobbying ef-

forts in pursuit of land purchases. Duer

might have told Cutler that

time was needed to recruit substantial

investors. A third explanatory

element has been advanced tentatively by

historian Staughton

Lynd: Cutler was a courier carrying news

critical to a sectional bar-

gain then being developed in the

Convention.40 Soon after a 6:30 P.M.

arrival (48 hours after his departure

from New York) he met with

"several members of Congress."

Possibly these were the half-dozen

view, 25 (1938), 167.

39. July 19, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC;

Poole, "Dr. Cutler," 261-62.

40. Staughton Lynd, "The Compromise

of 1787," Political Science Quarterly,

LXXXI (June, 1966), 225-50. Cutler and

Cutler (eds.), Life, 1:252-54.

116 OHIO HISTORY

or so who had earlier journeyed to

Philadelphia. This evening con-

fab lasted until 1:30 A.M.

Cutler's observations and accounts of

his stay in Philadelphia July

12-14 are most renown. His ubiquitous

and all encompassing eye plus

his stylish pen provide scholars with

"color" in portraying the back-

drop to the Federal Convention. Cutler

partook of late night confabs

among the southern and eastern delegates

at the Indian Queen Tav-

ern, provided a charming vignette of

Benjamin Franklin holding forth

at a garden party, painted detailed

descriptions of the Convention's

meeting hall in the State House, and

noted how a trip to William Bar-

tram's botanical gardens served as a

caucus before the Grand Com-

promise was affirmed July 16. 41 If he talked

medicine with Benjamin

Rush, or "natural curiosities"

with Charles Willson Peale, he found

time to wax eloquent about national

growth within the presence of

the distinguished delegates,

particularly those from southern dele-

gations. From the catalog of letters of

introduction sought by Cutler

and from the foci of discussions within

greater Philadelphia, it can

be hypothesized that he was making a

personal bid to become a

botanist attached to the University of

Pennsylvania. Diary entries

lead to a conundrum: no sooner did he

arrive in Philadelphia than

he began telling everyone that he must

speedily return to New York.

Perhaps in addition to his personal

quest, he was acting as courier. A

colleague, Nathaniel Gorham remarked

about Cutler's popularity

and that "letters or packets were

left" at the Philadelphia tavern for

him.42 Whatever his purpose,

he returned to New York City July 17.

Cutler's manuscripts yield no direct

comment on the nature of the de-

bates in Convention. He does mention

that Franklin was about to

confide in him and then reconsidered.

It took ten intense days for Cutler to

convince the Board of Treas-

ury and the Congress to accept the terms

of the Ohio Company. It ap-

pears Congress worked steadily and

cautiously on the sale from July

13 onward. A crucial point was gained

July 14 when Congress di-

rected the Board of Treasury to

negotiate "with Samuel Holden

Parsons esquire or any other agent or

agents" of the Ohio Company.

An effort to solicit other bids for

public lands was defeated in a

41. July 12-14, 1787, Journeybook II,

MCC. Cutler twice attended informal caucuses

comprised of delegates from Massachusetts,

North Carolina, South Carolina, Virginia

and New York. He thus was privy to the

alignment of the large states' strategy at this

crucial time in the convention. Calvin

C. Jillson and Cecil L. Eubank, "The Political

Structure of Constitution Making: The

Federal Convention of 1787," American Journal

of Political Science, 28 (August, 1984), 443-45.

42. Cutler and Cutler (eds), Life, I:284.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 117

rollcall (two ay, four no, two divided).

In the following fortnight Con-

gressional deliberations would focus on

a number of western sub-

jects: Indian depredations, British

retention of forts, and the land

sale questions. On July 18 and 19 Cutler

renewed negotiations with

the Congressional committee. He quickly

assessed Congressional fac-

tions: "As there are a number in

Congress decidedly opposed to my

terms of negotiation, and some to any

contract, I wish now to ascer-

tain the number for and against, and who

they are and must then, if

possible, bring the opponents over."43

By the nineteenth he be-

lieved he had the committee persuaded to

be Company advocates

but was not certain of sentiments in

Congress at large. His diary for

this period lists frequent dining

appointments, the most pivotal being

on Friday, July 20. That evening he took

the ferry to Brooklyn to sup

with Duer, Sargent and others. At an

"elegant" dinner over "deli-

cious" oysters and later at the

speculator's home, a deal was made.

In addition to the one and one-half

million acres sought by the Ohio

Company, Cutler would put forward a bid

for another five million

acres. This parcel would be open to

option by an unidentified group

of investors known as the Scioto

Company, Cutler obliquely identi-

fied them merely as "a number of

the principal characters in the

city." Cutler and Sargent in turn

would receive thirteen of the thirty-

two shares of this venture from Duer and

associates. Duer's initial

prime contribution was to supply

$143,000 as the down payment to

Congress. Such resources were much

needed as Cutler and his Ohio

Company Associates had amassed only

one-fourth of their goal of $1

million in securities.44 Cutler

portrayed himself in his journeybook as

reluctantly conceding to Duer's

"generous terms." Such agreement

cemented Cutler not only with the

unscrupulous New Yorker but also

bonded him and his New England

colleagues with those Southern

and Middle Atlantic investors recruited

by Sargent. He agreed to

keep their pact "a profound

secret." The following day Cutler again

made the rounds, visiting Knox and more

than forty members of the

Order of the Cincinnati, in search of

investors in either or both

companies.

43. Nathan Dane to Rufus King, July 16,

1787; July 19, 1787, Diary, Cutler and Cutler

(eds.), Life, I, 371-72; 293-94;

Ford (ed.), JCC, 32:345-46.

44. July 20, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC;

Francis S. Philbrick, The Rise of the West

1754-1830 (New York, 1965), 124-25. H. James Henderson, Party

Politics in the Conti-

nental Congress, (New York, 1974), 410-13. Ultimately the Ohio Company received less

than half the land for which it

contracted. The Scioto Company, which failed in 1792,

never formally entered into a contract.

118 OHIO HISTORY

The parson believed he was negotiating

from a position of strength.

He rejected terms put forward by a

Congressional ordinance July 20.

He assumed a stance of preferring to

purchase state lands, such as

those available in Maine, at

"incomparably better terms" than those

proffered in the national domain. Cutler

joyously recorded, "The

Committee were mortified, and did not

seem to know what to say,

but still urged another attempt."

Privy to inside information, Cutler

believed that he could bluff Congress.

His journeybook confided

that members of the Committee assured

him, "I had many friends in

Congress who would make every exertion

in my favor." He urged

them to press the matter immediately

though noting it might take two

or three months to succeed. Meanwhile he

developed a tallysheet.45

Among "warm advocates" in

Congress he listed the Virginia triumvi-

rate of Carrington, Grayson and Richard

Henry Lee. Cutler's grand-

children later hypothesized that

"the interests of Virginia were

closely connected with plans of the Ohio

Company." Virginians saw

permanent occupation of the Ohio Valley

as both a defensive line and

a link in their own commercial

aspirations.46 Never one to take things

for granted, Cutler listed the

representatives of Massachusetts: Sam-

uel Holton as "may be trusted"

and Nathan Dane "must be carefully

watched." Some Eastern delegates,

sensitive that state land sales

would diminish if federal deals were

struck with the Ohio Company,

were cool to Cutler. He focused on a

pivotal quintet composed of four

from the middle states-Abraham Clark

from New Jersey, William

Bingham from Pennsylvania, Abraham Yates

from New York, and

Dyre Kearny from Delaware-plus William

Few from Georgia. These

"troublesome fellows" would be

"attacked by my friends at their

lodgings. If they can be brought over I

shall succeed, if not, my busi-

ness is at an end."

While city allies outside of Congress

and converts within carried

out his plans, Cutler patiently

maintained his routine. He attended

three services on the sabbath, increased

formal and informal visits

with members of the Board of Treasury,

and solicited intelligence

from delegates such as Dane and

bureaucrats such as Milligan. All

the while he projected the facade that

he was indifferent to the en-

treatments of Congress. By Saturday July

21 he thought such a

stance "had the desired

effect" as he then put forward the auda-

cious offer of the Ohio and Scioto

Companies to retire $4 million of

45. July 19, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC;

Cutler and Cutler (eds.), Life, I:vii; Poole,

"Dr. Cutler," 252-53.

46. Cutler and Cutler (eds.), Life,

I:453, 352, 370.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 119

the national debt through land-sale

revenues. Among his arguments

was the pitch to renew negotiations:

"That our intention was an actu-

al, a large, & immediate settlement of the most

robust, & industrious

people in America. And that it would be

made systematically, which

must instantly enhance the values of

federal lands and prove an im-

portant acquisition to Congress."47

The tract he sought had its east-

ern border touching the western extent

of the seventh range of town-

ships already surveyed by Congress; the

Ohio River served as the

southern perimeter; the western line was

the meridian drawn

through the western cape of the Great

Kanawha River; the northern

border was an east-west line from that

meridian to the seventh range.

Cutler's rhetoric plus the fieldwork of

teams of three and four friends

orchestrated by Duer and Sargent gained

a triumph when, after a

warm debate July 23, Congress produced a

third ordinance concern-

ing land sales. This directive to the

Board of Treasury was not entire-

ly to Cutler's liking but left room for

negotiation, an opportunity he

did not let pass.

Two objectives came in focus for Cutler.

First, to further cement

clout in Congress he agreed to a

bargain. To add to his Southern

base of friends, he pursued support of

delegates from the middle

states. In the patronage devised by the

Northwest Ordinance the

relative plum was that of the

territorial governorship. In an informal

caucus with southern delegates, Cutler

agreed to dump Samuel

Holden Parsons. He switched allegience

to the candidacy of Penn-

sylvanian Arthur St. Clair, then

presiding over Congress. Further, he

supported Winthrop Sargent as secretary

and supported nomination

of Parsons and Putnam as two of three territorial judges. Such maneu-

vers, Cutler believed, "would

solicit the eastern members to favor

such an arrangment. This I found rather

pleasing to the southern

members." There was no push to

place a southerner among territory

officers. Shrewdly Cutler declined an

office for himself, a stance that

surprised his cronies who were "so

much used to solicit, or to be so-

licited, for appointments of honor or

profit."48

Secondly, the lobbyist, in yoke with

Sargent, brought his skills to

bear on the Board of Treasury. In

concert with Sargent and Duer he

dispatched an "ultimatium" on

July 24.49 Then he gained a dinner

47. July 21, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC.

48. July 23, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC;

Burnett, Continental Congress, 687.

49. July 24, 1787 Journeybook II, July

25-26, 1787, Diary, MCC; Burnett, LMCC,

8:629n; Cutler and Cutler (eds.), Life,

II: 429-30. The contract offered by Congress July

23 and the counteroffer, dated July 26

and extending the payment schedule, are in

Ford (ed.), JCC, 33:399-401,

427-29.

120 OHIO HISTORY

appointment with Samuel Osgood and lunch

with Michael Hillegas,

Treasurer of the United States. Cutler,

as was his wont, won over

Osgood; he recorded he found the head of

the Board "to be very

solicitous to be fully informed of our

plan. No gentleman has a higher

character for planning & calculation

than Mr. Osgood." It is clear

that Cutler confided plans of both the

Ohio and Scioto Companies.

Through befriending Congressman Richard

Henry Lee, Cutler had

also "taken the measure" of

Arthur Lee's "foot." Thus he gained

support of both active members of the

Board. Reflecting on his own

experiences Cutler had learned to be

"very suspicious [and] cau-

tious" in his dealings: "such

is the intrigue and artifice which is of-

ten practiced by men." Although the

Board was supposedly fo-

cusing its energies on a packet destined

for Britain (and thus could

not carry on negotiations with the Ohio

Company), its President, a

former delegate from Massachusetts, was

able to spend the afternoon

and evening alone with the lobbyist! In

awe, and in private, a Massa-

chusetts Congressman remarked "he

never knew so much attention

paid to any one person" than Cutler

was gaining from Congress. "He

could not have supposed that any three

men from New England, even

of the first character, could have

accomplished so much in so short a

time."50 Such flattery

might have warmed Cutler, but he continued

to work diligently.

By July 26, Thursday, cultivations were

bearing fruit. The trio of

Cutler, Knox and St. Clair, symbolizing

accord among land adventur-

ers, veteran officers, and Congressional

leadership, made a symbolic

early morning tour. They visited the

representatives of foreign nations

to discuss western settlements.51

St. Clair confided in the morning

that he would press Congress to accept

conditions stipulated by Cut-

ler's bid. "Every machine in the

city that it was possible to set to

work we now put in motion," the

strategist noted. It is apparent that

Cutler then believed the Board would

recommend his bid. From

Congressman Holton, constantly

counseling patience and providing

information on colleagues, the trio of

Cutler, Duer and Sargent learn-

ed that Bingham had been won over. Few

now seemed less resistant,

but Kearny was written off as a

"stubborn mule." Nonetheless, a

"warm seige was laid on Few and

Kearny from different quarters."

Cutler calculated he could only gain his

contract if seven of the eight

states present sided with the Ohio

Company. A backup plan was de-

veloped. Should the lobbyists fail to

gain the necessary majority,

50. July 26, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC.

51. July 26, 1787, Cutler and Cutler,

(eds.), Life, I:300-03.

|

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 121 |

|

|

|

Sargent would travel to Maryland while Cutler sped to Connecticut and Rhode Island. Sargent was "to prevail on the members to come on, and to interest them, if possible, in our plan." The New England- er would "lay an anchor to the windward." He and his colleagues plotted their moves until 2 A.M. Cutler was not sure enough of a major- ity to press for a congressional roll call. On Friday morning, July 27, the Board of Treasury recommended that Congress accept the terms specified by Cutler's "ultimatum." In 1785 and again on April 21, 1787, Congress had resolved that a mini- |

122 OHIO HISTORY

mum price of $1 per acre (specie or

equivalent) would stand. Cutler,

however, demanded a reduction in the

form of allowances for bad

lands, surveying costs and incidental

expenses. Such deductions

would cut the price by one-third.

Additionally he would gain stipu-

lations that in each township 640 acres

would be set aside "for pur-

poses of religion; an equal quantity for

the support of schools; and two

townships, of twenty-three thousand and

forty acres each, for a uni-

versity." The crucial demand was

that though total payment be

made in eight installments, deeds would

be gained after the first $1

million paid.52 Cutler made

another threatening gesture when he

packed his baggage and spoke for the

first time about frontier unrest

in Kentucky. He felt sure no other

companies were prepared to enter

bids at this time although he knew of

the aspirations of John Cleves

Symmes.

When a debate began early in the day,

Richard Henry Lee would

speak an hour on Cutler's behalf. It was

rumored that Few had capit-

ulated. Cutler lurked outside City Hall.

By adjournment Congress

conceded. The Board of Treasury was

ordered to contract with Cut-

ler, Sargent and Associates. A down

payment of a half-million dollars

would accompany execution of the

contract, and a like sum would be

paid when the land surveys were complete

and the balance would

be met by six equal, semiannual

installments. There was never a roll

call made on the decision! Cutler,

informed by 3:30 P.M. of this

"agreeable, but unexpected

intelligence," hurried arm in arm with

Sargent to the Board of Treasury.53

Somewhat surprisingly he deter-

mined to depart immediately for home rather

than enter into comple-

tion of the contract. Perhaps he had

amassed insufficient funds to

meet the stipulations of down payment.

After "making a general ver-

bal adjustment" with the Board and

leaving Sargent to work on de-

tails, the lobbyist hastened to his

lodgings. As he trod up Broadway

to Henderson's, friends and Congressmen

stepped forward to offer

congratulations. By 6 P.M. he was on the

road home. Whether that

night, or more probably at a later date,

he recorded his triumph in

his journeybook:

By this ordinance we obtained the grant

of near 5,000,000 of acres of land,

amounting to 3 million & half of

dollars. One million & an half of acres for the

Ohio Company & the remainder for a

private speculation, in which many of

52. Ohio Company Proceedings, August 29,

1787, Cutler and Cutler (eds.), Life,

I:319.

53. July 27, 1787, Journeybook II, MCC;

Cutler and Cutler, Life, II:429-30.

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist 123

the principal characters in America are

concerned, without connecting this

speculation, similar terms &

advantages could not have been obtained for

the Ohio Company.54

Cutler was home in time to preach to his

Ipswich congregation Au-

gust 5. He had completed the first of

many successful trips on behalf

of the Ohio Company. In October he would

return to New York City

to sign the contracts on behalf of both

the Ohio and Scioto Compa-

nies with the national government.

Within the year he would dis-

patch the first contingent of settlers,

including one of his sons, from

Massachusetts to Marietta, Ohio. Soon

thereafter, Cutler the natural-

ist set off to examine firsthand the flora

as well as fauna of the Ohio

Company purchase gained by his efforts

as lobbyist.

Analysis of Cutler's activities in the

spring and summer reveals the

fortuitous meshing of his personal

attributes with political opportuni-

ty. His character was that of a

keen-eyed, energetic, and persistent

actor in history. His care for detail

and scheme-making enabled him

to orchestrate various tactics to

cultivate subscribers to the Ohio

Company and to convince congressional

delegates of the feasibility of

his plans. His affable style appealed to

companions from all sections

of the country. No matter what his

character, Cutler could not have

made much headway had not the

expectations of men in and out of

Congress come to focus on the west in

1787. Nor could he have been

triumphant if political

circumstances-the votes gained by fair means

or otherwise-had not swung his way.

There factors combined for

Cutler to accomplish "the greatest

contract every made in America,"

as he boasted in 1787.55

54. The euphoric entry of the Journeybook for July 27, 1787, runs to eight

pages and

appears to be a later embellishment of

the diary entry of the same date. Cutler is

uncharacteristicly profuse with kudos to

Duer. Also mentioned is Hazard who, with

Sargent, appears to have provided loyal

support in the entire campaign. The use of the

past tense in the diary indicates it

might not been created on the dates specified.

55. October 26 [27], 1787, Journeybook

I, MCC. Lee Nathaniel Newcomer, "The

Big World of Manasseh Cutler," New

England Galaxy, 4 (1962), 29-37, outlines Cutler's

career after 1787.

LOUIS W. POTTS

Manasseh Cutler, Lobbyist

On August 3, 1787, the parson of the

Congregational Church in

Ipswich (now Hamilton) Massachusetts

returned to his hamlet. He

calculated he had traversed 885 miles in

his one-horse sulky in the

past two months and considered it

"one of the most interesting and

agreeable journies I ever made in my

life. It had in every view been

prosperous but in many respects

infinitely exceeded my expecta-

tions."1 Somewhat the

polymath, he could cite among his feats the

reestablishment of acquaintances with

President Ezra Stiles and oth-

er divines at Yale, the addition of many

new plants for his preeminent

botanical collection, and a visit to the

wondrous zoological exhibits

of Charles Willson Peale. The crowning

deed was not that he had

gained proselytes for his faith, but

rather that he was on the verge of

sealing the largest public contract yet

negotiated in the United States.

He had successfully bid for more than

four million acres of the pub-

lic domain. Further, according to some

later historians (if not contem-

poraries), he had made significant

contributions to two major docu-

ments being drafted in the early summer

of 1787: the Northwest

Ordinance molded by the Congress under

the faltering Articles of

Confederation and the Constitution

evolving in the Grand Conven-

tion. How much credit should this

extraordinary clergyman be giv-

en? What were his tactics and strategies

as an agent? Edward Chan-

ning offered this appraisal of Manasseh

Cutler: "He took not

unkindly to the devious methods that

were necessary in those days

Louis W. Potts is Associate Professor of

History at University of Missouri-Kansas

City.

1. August 3, 1787, Journey Book II-B,

Manasseh Cutler Collection, Northwestern

University. Hereafter citations to these

manuscripts will be listed MCC. For a critique

of the published version of Cutler's papers see Lee

Nathaniel Newcomer, "Manasseh

Cutler's Writings: A note on Editorial

Practice," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47

(June, 1960), 88-101. Newcomer noted:

"At the hands of his editors Manasseh Cutler

has been under-humanized as well as

over-politicized. Because of the liberties which

they took with his writings, a more

nearly complete and better balanced portrait of

Cutler must depend upon the manuscripts rather than

upon the edited version pro-

duced by his grandchildren."

(614) 297-2300