Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

RICHARD K. FLEISCHMAN AND

R. PENNY MARQUETTE

Chapters in Ohio Progressivism:

The Cincinnati and Dayton Bureaus

of Municipal Research and

Accounting Reform

Introduction

During the Progressive era in American

history, reformers attacked

corruption, bossism, unbridled

plutocracy, and what they perceived to

be the decay of traditional American

morality. Following the depres-

sion of 1893, one of the most severe in

the nation's history, many

reformers focused on a new common

cause-the appalling condition of

the country's municipalities. Though

the muckraking efforts of Jacob

Riis and Lincoln Steffens did not focus

on the need for municipal

reform until after the turn of the

century, the cat was definitely out of

the bag. The English observer James

Bryce declared city administra-

tion America's "most conspicuous

failure," while the American

educator Andrew White wrote that

municipal governance in this

country was the "most corrupt in

Christendom."1

A lengthy list of urban ills can be

found in any of the many standard

histories of the Progressive movement.

Political bosses maintained

themselves in power with the immigrant

vote and the ward system of

representation. Most distressing to the

Progressive was the apparent-

ly Diogenian futility of trying to find

an honest city official. The

inevitable result was not only

corruption, but rampant administrative

inefficiency.

Richard K. Fleischman is Associate

Professor and Chairman of Accounting at John

Carroll University and R. Penny

Marquette is Professor of Accounting at The University

of Akron. They would like to thank

Arthur Andersen & Company for financial support

of this research.

1. Richard K. Fleischman and R. Penny

Marquette, "The Origins of Public

Budgeting: Municipal Reformers During

the Progressive Era," Public Budgeting &

Finance, 6

(Spring, 1986), 71.

134 OHIO HISTORY

Municipal accounting and reporting were

so chaotic that effective

urban governance would have been

impossible even with an honest

administrator at the helm. Governmental

accounting methodology was

"in swaddling clothes,"

observed one contributor to The Journal of

Accountancy.2 The problems were glaring. There was no uniformity in

municipal accounts; different

departments of the same city government

often had different bookkeeping systems;

auditing of city books was

rarely done; and cost accounting methods

as basic as centralized

purchasing, work standards, and control

over inventories awaited

future development.3

Progressives attacked urban problems in

a great variety of ways.

Much fanfare surrounded attempts at

structural reform-centralization

of power in the office of mayor, direct

democracy (initiative, recall,

referendum), home rule, and charter

reforms (city manager and

commission forms of city government).

However, the real strides

forward came as a result of the

utilization of experts and the imple-

mentation of systems, what John W.

Chambers has called the "new

interventionism."4 Cities

needed better methods of accounting and

control-systems which would allow for

planning, efficient administra-

tion, and oversight by a vigilant

public.

The improvements in municipal

record-keeping accomplished in

Cincinnati and Dayton were typical of

the age. Yet, despite the high

degree of reforming activity and

achievement, historians have failed to

be concerned with developments in

accounting. In an early classic of

the historical literature, Richard

Hofstadter highlighted the role of the

"alienated professional"

classes, including lawyers, university profes-

sors, ministers, and newspaper editors.5

Samuel Hays subsequently

took Hofstadter to task for ignoring the

contributions of engineers,

architects, and doctors.6 Neither

considered the accountants who

played the largest role in one of the

major success stories of the

Progressive era-the genesis of urban

fiscal responsibility.

2. W. D. Hamman, "Efficiency in

Municipal Accounting and Reporting," The

Journal of Accountancy, 17 (January, 1914), 28.

3. Edward M. Hartwell, "The

Financial Reports of Municipalities with Special

Reference to the Requirements of

Uniformity, "Proceedings of the National Municipal

League, 5 (1899), 127, and Frank J. Goodnow, City Government

in the United States

(New York, 1904), 300-01.

4. John W. Chambers II, The Tyranny

of Change: America in the Progressive Era

1900-1917 (New York, 1980).

5. Richard Hofstadter, The Age of

Reform (New York, 1955), 148-64.

6. Samuel P. Hays, "The Politics of

Reform in Municipal Government in the

Progressive Era," in D. M. Kennedy,

ed., Progressivism: The Critical Issues (Boston,

1971), 90.

Chapters in Ohio Progressivism 135

Modern analysis has revealed broader

roots of the Progressive

movement than Hofstadter imagined.

Historians such as Wiebe,

Weinstein, Huthmacher, Buenker, and

Thelen have extended the base

far beyond the professional classes to a

more "universal framework,"

including businessmen, consumers,

taxpayers, and citizens.7 Local

studies have become significantly more

important given these widened

parameters of Progressivism.8 Still,

except for the work of Augustus

Cerillo on the budgeting and accounting

activities of the New York

Bureau of Municipal Research, little has

been done in the municipal

accounting area.9 This study

of the activities of the Cincinnati and

Dayton Bureaus of Municipal Research

will focus on this neglected

facet of urban Progressivism.

The accounting profession was in a

nascent state of development

during the early Progressive era, which

might explain in part this lack

of attention. Accounting in this country

was imported from abroad in

great measure. Foreign creditors and

stockholders of large domestic

enterprises hired leading English

auditors in an effort to safeguard their

investments, particularly in the

railroad industry. The presence of

these overseas experts spawned the

growth of branch offices here and

the rise of a domestic profession to

staff them. In 1887, the American

Association of Public Accountants came

into existence, a direct

predecessor of the current practitioner

organization, the American

Institute of Certified Public

Accountants.

It was not until 1896 that the title

"Certified Public Accountant" was

first legally recognized in this country

and the first C.P.A. examination

administered. Throughout the first

decade of the twentieth century,

various states passed C.P.A.

legislation-Ohio in 1908. However,

these early years of the profession's

development did not impact

governmental accounting which remained

the province of untrained

bookkeepers. It was not until 1906 when

the American Association was

invited to work with the Keep Commission

investigating accounting

methods in the federal government that

the public sector became a

subject of interest to the profession.

There had been some earlier

associations as C.P.A.s were

occasionally hired as experts to install

7. Michael H. Ebner and Eugene M. Tobin,

The Age of Urban Reform (Port

Washington, New York, 1977), 3.

8. Ibid., 4-5.

9. Augustus Cerillo, Jr., "The

Impact of Reform Ideology: Early Twentieth-Century

Municipal Government in New York

City," in Michael H. Ebner and Eugene M. Tobin,

The Age of Urban Reform (Port Washington, New York, 1977), 82-85.

136 OHIO HISTORY

accounting systems in state and

municipal governments, but generally

the young public accounting firms viewed

governmental auditing with

disdain.

The State of Ohio has enjoyed a certain

notoriety in the multitude of

historical studies of the Progressive

era. In particular, two of the most

famous reform mayors, Cleveland's Thomas

L. Johnson and Toledo's

Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones,

were Ohio-based. Lincoln Steffens, the

consummate muckraker, brought national

attention to the state with

his 1905 article in McClure's

Magazine, "Ohio: A Tale of Two Cities,"

as he contrasted Johnson's Cleveland and

Boss George Cox's Cincinnati

as a respective prototype and antithesis

of good urban government.

Hoyt Warner has written a seemingly

exhaustive, five-hundred page

book on Progressivism in Ohio, but just

as with other historians,

Warner devoted little attention to

municipal accounting reform.10

Consequently, the leadership role of

accountants in Ohio's Progressiv-

ism requires investigation and, if the

record warrants, due credit given.

Municipal Progressivism

The first decade of the twentieth

century was a seminal period in the

development of a municipal accounting

methodology. More sophisti-

cated techniques and a new awareness of

purpose were just develop-

ing. Most of the new procedures emanated

from New York City, but

contributions were also forthcoming from

traditional Progressive

strongholds, including LaFollette's

Wisconsin and Johnson's Cleveland

(Tom Johnson and his administration in

Cleveland were in the van-

guard nationally in the areas of systems

development and citizen

awareness).11 The end results were a

heightened utilization of budget-

ing, a greater involvement of expert

accountants and auditors in

municipal finance, and the installation

of accounting systems to

guarantee control and accountability.

The National Municipal League (NML

hereafter) was organized in

1894 as the capstone organization for

various local and regional efforts

to improve urban governance. Its

Committee on Uniform Accounting

Methods had initially written and

subsequently popularized standard-

ized accounting schedules which brought

the benefits of uniform

10. Hoyt L. Warner, Progressivism in

Ohio, 1897-1917 (Columbus, 1964).

11. Richard K. Fleischman and R. Penny

Marquette, "Municipal Accounting Reform

c. 1900: Ohio's Progressive

Accountants," The Accounting Historians Journal, 14

(Spring, 1987), 89-92.

Chapters in Ohio Progressivism 137

reporting practices to a number of state

and local governments.12 The

State of Ohio was the first to mandate

common accounting forms for all

constituent municipalities, villages,

and even school districts. In 1902,

a fifty year-old state scheme of

grouping municipalities for legislative

purposes was declared unconstitutional,

and suddenly no legal govern-

mental form existed for any Ohio municipality.

Progressives hoped the

state legislature would adopt liberal

municipal charters, but the results

were far different. The Ohio Code of

1902 was extremely disappoint-

ing, but the accounting provisions were

encouraging. In a reactionary

attempt to maintain control, the state

government provided a great

service in the area of municipal

accountability by requiring standard-

ized financial reporting. The clear

result was Progressivism but for all

the wrong reasons.

Perhaps the most important antecedent of

the Cincinnati and Dayton

Bureaus of Municipal Research (founded

in 1909 and 1912, respective-

ly) was the organization of the New York

Bureau of Municipal

Research (NYB hereafter) in 1906. The

accountants and political

scientists of this agency, acting as

advisors to New York City Comp-

troller Herman A. Metz, revolutionized

municipal governance in the

country's largest city. More

importantly, the NYB did not hide its light

under a bushel. Reports on the success

of the new techniques were

distributed to state and municipal

governments the length and breadth

of the country, thanks to the resources

of a fund the independently

wealthy Metz endowed. Municipal experts

associated with the NYB

were available for hire to conduct surveys

for municipal governments

anxious to reform their systems. The NYB

organized the endowment

of the Training School of Public

Service, a postgraduate program in

municipal administration. Graduates of

this institution went forth from

New York City to become leaders in the

municipal reform movement.

The success of the NYB spawned a number

of similar efforts in many

major American cities. Chester E.

Rightor wrote an article on these

research bureaus which appeared in the

1916 National Municipal

Review, the official publication of the NML. At the end of his

piece

Rightor listed twenty-three such

agencies functioning in the United

States-five of these (Akron, Cincinnati,

Cleveland, Columbus, and

Dayton) were located in Ohio.13 It

is within this context of significant

12. Richard K. Fleischman,

"Foundation of the National Municipal League," The

Journal of Accountancy, 163 (May, 1989), 297-98.

13. Chester E. Rightor, "Recent

Progress in Municipal Budgets and Accounts,"

National Municipal Review, (1916), 637.

138 OHIO HISTORY

municipal Progressive activity in Ohio

that we now focus on the

activities of the Cincinnati and Dayton

Bureaus of Municipal Research.

The Cincinnati Bureau of Municipal

Research

By a large margin the most active and

productive research agency in

the State of Ohio was the Cincinnati

Bureau of Municipal Research

(CBMR hereafter). Perhaps its success

was in part explained by the

fact that municipal governance was at

such a low ebb under Boss

George Cox that there was more to

accomplish. It has even been

suggested that the CBMR was initially

established for the purpose of

gathering evidence to overthrow the

machine.14 However, the Bureau

delineated for itself a nobler

purpose-to study the methods of city

government, to recommend improvements in

methodology, to promote

efficiency and economy, and to furnish

the facts necessary for an

informed citizenry. In its inaugural

statement the CBMR recognized its

role in the betterment of municipal

accounting, "In many respects the

work of the Bureau resembles that of

expert accountants who are

summoned by business men to examine

their methods and point out

where savings can be made or better

results secured."15

The CBMR was founded in 1909 as a

cooperative effort of a

half-dozen organizations including the

City Club and the Chamber of

Commerce. Rufus E. Miles, formerly of

the NYB, was recruited as

director, with another New York trained

colleague, F. R. Leach, as

associate director and head of

accounting-related operations. The staff

was composed of faculty and students

from the University of

Cincinnati's political science

department. It is no coincidence that the

birth of the CBMR corresponded to the

decision of the NML to hold its

annual convention in the Queen City that

very year. The NML

traditionally chose its venues carefully

and would never have come but

for the confidence that the reign of Cox

was over.

The initial focus of the CBMR was the

Parks Department whose

accounting was in an absolute shambles.

A single-entry system was in

effect which offered no hope for

accountability. Expense statements

were totally unsupported by

documentation, and entries to the various

funds were so confused as to defy

sorting out. Proper cost accounting

techniques were totally absent. There

was no inspection of supplies, no

knowledge of quantities, and no way to

check for waste or pilferage.

14. Norman N. Gill, Municipal

Research Bureaus (Washington, 1944), 17.

15. Cincinnati Bureau of Municipal

Research, Annual Report (Cincinnati, 1910), 8.

Chapters in Ohio Progressivism 139

Small lot purchasing was so rampant that

in 1909 the average order for

a $25,000 supplies and materials budget

was $30. All of these defects

were outlined in a report the CBMR

prepared for the Parks Depart-

ment. By the next year the Parks

Department had reacted positively to

the suggestions, and there was in place

a modern double-entry account-

ing system and cost accounting controls

which the Bureau called

similar to a first class business

corporation and to the system in place

in New York City.16

Over the course of the next seven years,

the CBMR worked closely

with nearly every department in city

government. The major focus was

on improved record-keeping and revamped

accounting methods. De-

partments had differing requirements for

accurate statistics, but the

bottom line was "strict

accountability." The city came to be able to

depend on departmental reports for

planning and control purposes.

The CBMR also dealt extensively with the

departments in introduc-

ing cost accounting methods. The Bureau

sent a letter to Mayor

Schwab in 1911 requesting a Committee on

Economy and Efficiency

whose agenda would include a feasibility

study of work standards, the

utilization of monthly cost statements,

heightened supplies control and

inspection, and the introduction of

purchase price standards.17 The

CBMR not only lobbied successfully for

the implementation of cost

accounting generally, but also accepted

credit for improved cost

methods in seven different city

departments. The monetary impact was

greatest in the Purchasing Department

where the Bureau estimated

annual savings of $70,000 in supply

procurement alone. The CBMR in

its 1913 report noted proudly, "The

Purchasing Department has

already reached a state of efficiency

which is attracting attention

outside of Cincinnati. It has not only

proved its ability to save money

for this city, but it is exercising

influence over other cities."18 The

Bureau bragged further in a pamphlet

distributed in 1913, "Cincinnati

will soon be one of the few cities in

the country where accurate figures

as to cost are obtainable."

The Bureau also worked with the City

Auditor in an attempt to

overhaul the accounting methods for the

entire city. In particular, the

Bureau identified three major problems:

the single-entry accounting

system in use; the absence of control

documentation over assets other

than cash; and an over-reliance upon an

accounting system based on

cash flows rather than the actual

earning of revenues and the incurring

16. Ibid., 11-13.

17. CBMR, Annual Report (Cincinnati,

1911), 10-11.

18. CBMR, Annual Report (Cincinnati,

1913), 7-8.

140 OHIO HISTORY

of expenses.19 Corrections

to the system came haltingly, but with the

coming of home rule a new general

accounting system became effective

on September 1, 1913. The new method

featured double-entry account-

ing and monthly expense and revenue

reports. Rightor concluded that

Cincinnati was one of the few cities in

the country with complete

control over its assets and

liabilities.20

Another major focus of the Bureau was

budget. In its first year of

operation the Bureau urged on Mayor

Schwab three suggestions in the

budget area: (1) a standardized,

printed form to be circulated to all city

departments for estimating purposes

(showing past and present expen-

ditures); (2) a policy that these

estimates be made public; and (3) that

public hearings be held on them.21

A reluctant Schwab accepted the

uniform blank of the Bureau's design

and also acquiesced in the

hearings. The Times-Star called

the 1911 hearing "the most represen-

tative body of citizenship seen in

Cincinnati in many years."22 The

CBMR rated the city's "budget

methods among the best in the

country."23 The budget

did not lack of precision. The 1913 edition had

a line item of $9,794.67 to cover the

cost of the new general accounting

system implemented that year.24

Another idea imported from the NYB was

the municipal budget

exhibit concept. Following the success

of expositions held in New

York in 1908 and 1910, the innovation spread

to other cities. In 1912,

Lent Upson was hired by Mayor Hunt of

Cincinnati and the CBMR to

organize a municipal exhibition. The

immediate cause was the need of

the administration to secure voter

approval to levy taxes beyond the

one percent of assessed valuation as

provided in Ohio's Smith Law.

The Bureau, on the other hand, was

motivated by the nobler goal of

citizen education.

The exhibit was advertised extensively.

Speeches were made before

every organization whose members were

willing to invite the promot-

ers. Advertising appeared in the

monthly billings of merchants, water

bills, and streetcars. Clergymen made

announcements from their

pulpits.25 The Cincinnati

press, particularly the Enquirer, was respon-

sive to the cause. The end result was

the largest municipal exhibit held

19. Ibid., 5-7.

20. Rightor, "Recent Progress . .

.," 631.

21. CBMR, Annual Report (1910),

15-16.

22. Rufus E. Miles, "The Cincinnati

Bureau of Municipal Research," in The Annals:

Efficiency in City Government (Philadelphia, 1912), 267.

23. CBMR, untitled pamphlet distributed

at 1913 Budget Exhibit.

24. Zane L. Miller, Boss Cox's

Cincinnati (New York, 1968), 215.

25. Lent D. Upson, Practice of

Municipal Administration (New York, 1926), 67.

Chapters in Ohio Progressivism 141

outside New York City. Estimates of

attendance varied from 109,000 to

150,000.26 The 1912 exhibit was so

successful that another was

attempted the next year with even

greater crowds. The Enquirer

estimated the 1913 numbers at 180,000.

Incidentally, Cincinnati voters

approved the tax levy by a two to one

majority, a remarkable

achievement in itself.

The CBMR had an enviable track record of

accomplishments during

its early years. However, as there came

to be increasingly less to

reform, contributions to the Bureau

declined. Pledges plummeted from

a high point of $21,627 in 1913 to a

meager $9,330 in 1915.27 The

Cincinnati Bureau went out of existence

during World War I.

The Dayton Bureau of Municipal

Research

The Dayton Bureau of Municipal Research

(DBMR hereafter) was

born out of the home rule legislation of

1912 that accorded voters in all

Ohio's municipalities the right to

select one of three governmental

structures prescribed by the state

legislature. The founding force

behind the Dayton Bureau, as well as its

sole financial support, was

John H. Patterson, President of National

Cash Register. Patterson as

early as 1896 had advocated the

introduction of business methods into

municipal government and the education

of the citizenry. He felt the

city was "a business enterprise

whose shareholders are the people."28

Patterson interviewed several candidates

for bureau director from the

NYB's Training School of Public Service.

The position was given to

Dr. Lent Upson, an exceptionally active

and prolific municipal re-

searcher, who was to go on to occupy a

similar post in Detroit after

1915. Upson was succeeded in turn by

Chester E. Rightor, another

distinguished director, who wrote an

excellent book on Dayton's city

manager system and who, with A. E. Buck

of the NYB, reported for a

decade to the National Municipal

Review on local and state govern-

ment advances in the budget-making

process.

Like every municipality in Ohio, Dayton

found itself with choices

following home rule in September, 1912.

The DBMR urged a revamped

structure of government. Many of the

problems with the old system

were accounting-related; i.e., excessive

expenditures, absence of

quality specifications for

contract-holders, and no cost or work stan-

26. Cincinnati Enquirer, October

1-15, 1912, passim.

27. CBMR, Annual Report (1913),

27 and CBMR, Annual Report (Cincinnati, 1915),

11.

28. Chester E. Rightor, City Manager

in Dayton (New York, 1919), 2.

|

142 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

dards. The Bureau worked diligently to secure passage of the new charter. Staffers collected data on the inefficiency and waste under the previous governmental form and disseminated the information by pamphlet, lecture, and newspaper report.29 When Upson spoke to the Dayton Evening Herald, it was often front-page news. Dayton's charter commission opted for a city manager form of government. This decision made Dayton the largest city in the nation to have a city manager and made it a focal point of great interest. The charter commission subscribed to the Progressive notion that govern- mental inefficiency results from an inadequacy of methods rather than the shortcomings of men. Consequently, the charter came to include provision for the establishment of budgeting and accounting proce- dures. With the help of the Dayton Bureau, the charter passed by a two to one majority. Following this initial success the Bureau embarked on years of distinguished service in the cause of municipal reform in Dayton. To facilitate these efforts the Dayton Bureau maintained close relations with the NYB. Carl E. McCombs of the Training School did a survey of Dayton's Department of Health in 1913, and the next year the NYB

29. Lent D. Upson, A Charter Primer (Dayton: 1914), 3-22. |

Chapters in Ohio Progressivism 143

did a survey of the Department of Public

Safety. The DBMR partici-

pated in the preparation and publication

of municipal budgets through-

out its short history. The Bureau

designed the item classification

format of the budgets and generated

citizen input through public

hearings. The DBMR called the Dayton

budget model "one of the most

complete budgets found in any

city."30

One of the parameters of municipal

Progressivism was the increased

participation of experts in city

governance. Henry M. Waite, Dayton's

first city manager, was influenced by

the DBMR to utilize specialists.

In particular, he appointed a local

public accountant as his director of

finance. The new official took steps to

institute controls over appro-

priations which insured greater

accountability. No less an astute

observer of the urban scene than

Frederic Howe, a trusted minion of

Tom Johnson, was impressed with the

business methods and expert

supervision in Dayton.31

The DBMR, in cooperation with the

Cincinnati Bureau, installed a

new accounting system for the Department

of Finance. The salient

feature of the new system was improved

control over the financial

records. Previous to 1914, the city had

depended solely on the annual

State Auditor's investigation.

Afterwards the city retained a C.P.A.

firm to audit the accounts continuously.

Rightor called the new

accounting system the most modern of any

city government by virtue

of its absolute control over public

funds.32 In 1914, the city at the

Bureau's behest instituted a central

purchasing system that included

standardization of costs and

specifications.

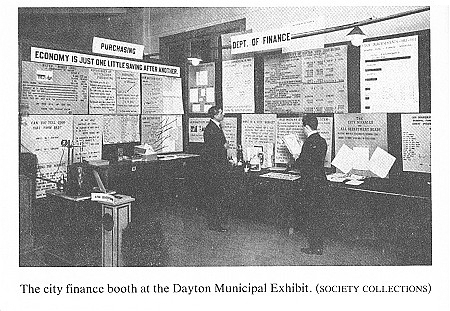

A municipal exhibit was also conducted

in Dayton in October 1915

by the DBMR. As was the case in

Cincinnati, the city fathers had a

vested interest-the need for a

two-thirds majority for passage of a one

million dollar bond issue. Fifty

thousand citizens attended the exhibit

during its ten-day run, and the bond

issue subsequently passed.

A testimony to the success of the DBMR

and the city manager

innovation was the decision of the NML

to hold its 1915 annual

convention in Dayton. Never before had

such a small city venue been

selected. Like its Cincinnati

counterpart the DBMR went out of

existence during the war.

30. Rightor, "Recent Progress ..

.," 644.

31. Frederic C. Howe, The Modern City

and Its Problems (College Park, Maryland,

1969), 116.

32. New York Bureau of Municipal

Research, Citizen Agencies for Research in

Government (New York, 1916), 54.

144 OHIO HISTORY

Conclusion

The Cincinnati and Dayton Bureaus of

Municipal Research were

typical of the substantial number of

reforming groups that failed to

survive a rechanneling of energies

precipitated by America's entry into

World War I. However, it is not to be

thought that the disappearance

of these civic organizations signaled

the end of municipal Progressiv-

ism in the two Ohio cities. Rather, one

does observe in the 1920s, as

Blaine Brownell has pointed out, an

"intensification of the quest for

efficiency and social control" at

the expense of political democracy.33

The Cincinnati and Dayton bureaus were

not reborn after the war

because the job had been done and the

pressing problems solved. City

officials in the 1920s saw the value in

utilizing trained accountants to do

the necessary record-keeping and

auditing tasks. The systems required

for adequate planning and fiscal control

were by then in place, thanks

to the earlier efforts and successes of

the municipal research bureaus.

33. Blaine A. Brownell,

"Interpretations of Twentieth Century Urban Progressive

Reform," in David R. Colburn and

George E. Pozzetta, eds., Reform and Reformers in

The Progressive Era (Westport, Connecticut, 1983), 17.

RICHARD K. FLEISCHMAN AND

R. PENNY MARQUETTE

Chapters in Ohio Progressivism:

The Cincinnati and Dayton Bureaus

of Municipal Research and

Accounting Reform

Introduction

During the Progressive era in American

history, reformers attacked

corruption, bossism, unbridled

plutocracy, and what they perceived to

be the decay of traditional American

morality. Following the depres-

sion of 1893, one of the most severe in

the nation's history, many

reformers focused on a new common

cause-the appalling condition of

the country's municipalities. Though

the muckraking efforts of Jacob

Riis and Lincoln Steffens did not focus

on the need for municipal

reform until after the turn of the

century, the cat was definitely out of

the bag. The English observer James

Bryce declared city administra-

tion America's "most conspicuous

failure," while the American

educator Andrew White wrote that

municipal governance in this

country was the "most corrupt in

Christendom."1

A lengthy list of urban ills can be

found in any of the many standard

histories of the Progressive movement.

Political bosses maintained

themselves in power with the immigrant

vote and the ward system of

representation. Most distressing to the

Progressive was the apparent-

ly Diogenian futility of trying to find

an honest city official. The

inevitable result was not only

corruption, but rampant administrative

inefficiency.

Richard K. Fleischman is Associate

Professor and Chairman of Accounting at John

Carroll University and R. Penny

Marquette is Professor of Accounting at The University

of Akron. They would like to thank

Arthur Andersen & Company for financial support

of this research.

1. Richard K. Fleischman and R. Penny

Marquette, "The Origins of Public

Budgeting: Municipal Reformers During

the Progressive Era," Public Budgeting &

Finance, 6

(Spring, 1986), 71.

(614) 297-2300