Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

MARK V. KWASNY

A Test for the Ohio National

Guard:

The Cincinnati Riot of

1884

Riots have been a part of our history

since the colonial days. Crowds

clashing with civil and military

authorities, violence in the streets, and

the deaths of citizens at the hands of

law enforcement agencies-these

are not unknown in the history of the

United States. The Cincinnati

Riot, March 28-30, 1884, contained all

of these elements. For three

days citizens, police, and soldiers of

the Ohio National Guard (ONG)

fought in the streets of Cincinnati,

leaving more than forty people dead

and well over one hundred injured. This

riot was remarkable, though

not unique, for the intense anger and

hostility exhibited by the crowd,

and the willingness of the police and

militia to meet these emotions

with all necessary force.

The Cincinnati Riot was a severe test

for both the ONG and the

entire state command system, from the

governor down to the regimen-

tal commanders. National Guard

organizations were relatively new

then, having replaced the state militia

units which had died out after the

Civil War. The 1877 Railroad Strike

impressed upon the states the need

for an effective internal police force,

and in that same year some states

began to hold summer camps for their

Guard units. Ohio held its first

in 1879.1 The riot in 1884 challenged

how much the ONG had improved

during these five years.

Domestic disturbances such as riots have

always posed a severe

problem for civilian and military

authorities. Civilian leaders often wait

too long before calling for military

assistance, usually because of an

unwillingness to admit they have lost

control of the situation, as well as

from a desire to avoid the costs

involved. At the same time, military

leaders are hesitant to involve

themselves in civilian affairs, preferring

Mark V. Kwasny is a Ph.D. candidate in

history at The Ohio State University.

1. Robin Higham, ed., Bayonets in the

Streets: The Use of Troops in Civil

Disturbances (Lawrence, Kansas, 1969), p. 27; William H. Riker, Soldiers

of the State

(New York, 1979), pp. 51, 56; John K.

Mahon, History of the Militia and the National

Guard (New York, 1983), p. 113.

24 OHIO HISTORY

to be summoned by civilian authorities

before moving.2 This tendency

to hesitate was a potential danger

during the hectic days in March 1884.

The civilian and military leaders of

Ohio had to pass such a test posed

by the Cincinnati Riot.

George Hoadly was governor of Ohio and

commander-in-chief of the

ONG during this crisis. He was not,

however, an experienced politi-

cian or military commander. Born in New

York and raised in Cleve-

land, by 1847 he was an aspiring young

lawyer in Cincinnati. He

married into a prominent Cincinnati

family, the Burnets, and held the

position of Judge of the Superior Court

of Cincinnati during the Civil

War. In 1883, during his gubernatorial

campaign, he needed the

support of the ethnic German vote, of

which Cincinnati had a large

proportion.3 Thus when the

riot began in March 1884, the commander

of Ohio's military force had little

political and no military experience,

while he had strong ties with Cincinnati

society and its German

population.

The governor received important help

from his staff during the crisis.

Adjutant General Ebenezer Finley,

Brigadier General Michael Ryan,

Quarter Master General and Commissary

General of the ONG, and

Colonels J. W. Harper, Samuel

Courtwright, and S. H. Church, all

aides-de-camp of the governor, were in

Cincinnati at various times

throughout the riot.4 Their

actions helped determine how well the ONG

reacted to this test.

The ONG at this time consisted of eleven

regiments, one battalion,

and two independent companies of

infantry, and seven batteries of

artillery. These units were scattered

throughout the state. Ohio had no

larger units of organization, though

Finley had previously advised a

reorganization. He believed that the

brigading of the regiments would

enable the officers to train with larger

field commands, which would

better prepare them for any emergency

that called for more than the

local militia. As of March the 4829

officers and enlisted men of the

ONG drilled only with their regiment,

company, or battery.5

The number of drills and level of

training of these units varied

widely. Attendance at unit drills was

poor, with less than one-half of

2. Higham, Bayonets, pp. 6-7.

3. Mary G. Roberts, "The

Governorship of George Hoadly, Governor of the State

of Ohio, 1883-1885" (M.A. Thesis,

Ohio State University, 1952), pp. 1-3, 6.

4. E. B. Finley, Adj. Gen., Annual

Report of the Adjutant-General, to the Governor

of the State of Ohio, for the Year

1884 (Columbus, 1885), pp. 4, 7. This

source cited

hereafter as AR 1884.

5. "Consolidated Report of Strength

of the Ohio National Guard for the Quarter

ending March 31, 1884," and

"Annual Report of Militia in the State of Ohio, Nov. 15,

1884," Ohio, Adjutant General, Ohio

National Guard, Administration, Morning, Quar-

terly, and Annual Reports, 1881-1890,

1898, 1907, 1911, ser. 2531, box 17,

1884, Ohio

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 25

the members usually participating. Also,

the Guardsmen in general

were not veterans of the Civil War, and

their only experience in the

field came from occasional strikes and

riots.6 Thus, the ONG in March

1884 consisted of scattered regiments

and batteries of soldiers with

little training and experience.

Cincinnati provided a real test for this

military force.

The test came when the situation in

Cincinnati pushed the citizens

too far. The problem centered around

political leaders John R. McLean

and Tom C. Campbell, who together

controlled Cincinnati politics.

Campbell, a criminal lawyer, also had a

reputation for manipulating

juries and the law to suit his clients.

Under this corrupt system, crimes

increased while convictions became

scarce. As one newspaper, the

Cincinnati Enquirer, wrote, Cincinnati was a "COLLEGE OF MUR-

DER."7 Tension mounted as one

gruesome murder followed another.

In March, twenty-three men accused or

convicted of murder were in

the county jail. Some had been in jail

for months without a trial.

Thomas J. Stephens, the mayor, was

allegedly involved with McLean

in the control of city politics. This

corruption rested on a voting system

that the politicians manipulated. As one

historian of the time described

it, the elections were for sale.8 Cincinnati

citizens, therefore, were

angry with their government and their

criminal justice system, and by

March 1884 they were close to action.

The final transgression occurred in

mid-March when William Berner

beat his employer to death. The people

followed his trial closely and on

March 22, the final day of the trial, a

large crowd filled the courtroom.

When the jury handed down a verdict of

manslaughter, the judge called

it "a damned outrage," while

the crowd hissed and threatened to hang

the jury.9 The fact that

Campbell was Berner's defense attorney did not

ease the situation. Thursday, March 27,

the newspapers printed an

announcement calling for a meeting of

citizens on Friday to condemn

the verdict, citing disgust at the

"fixed" juries of this and many other

Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio. This

source cited hereafter as MQAR.

6. "Consolidated Report, March 31,

1884," MQAR, box 17; J. S. Tunison, The

Cincinnati Riot: Its Causes and

Results (Cincinnati, 1886), p. 68.

7. Carl Wittke, ed., The History of

the State of Ohio, 6 vols. (Columbus, 1943), vol.

5: Ohio Comes of Age, 1873-1900, by Philip D. Jordan, pp. 193, 197; Rev. Charles F.

Goss, Cincinnati: The Queen City,

1788-1912, 4 vols. (Chicago, 1912), I, 256; Cincinnati

Enquirer, 9 March 1884, quoted in Iola H. Silberstein, Cincinnati

Then and Now

(Cincinnati, 1982), p. 126.

8. History of Cincinnati and Hamilton

County, Ohio; Their Past and Present

(Cincinnati, 1894), p. 367; Henry C.

Wright, Bossism in Cincinnati (Cincinnati, 1905),

p. 17; Tunison, Riot, p. 22.

9. Cincinnati Enquirer, 23 and 25 March 1884.

|

26 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 27

cases. According to the Volksfreund, "Judge

Lynch would soon be

honored in Cincinnati."10

The meeting occurred as scheduled Friday

evening, March 28, in the

Music Hall. Attended by "solid

men" of the city, it was the largest

indoor meeting in Cincinnati history to

that date, with the hall holding

about 8000 people. The leaders of the

meeting, trying to keep the

people calm, proposed resolutions

condemning the verdict and the

court system. Despite their efforts,

however, the speeches stirred the

people and the crowd began shouting

suggestions to hang Berner. The

presiding chairman decided to end the

meeting around 9:30 P.M.11

As the people left the hall, a shout

sounded: "To the jail! Come on!

Follow me, and hang Berner!" With

about 200 men leading the way,

much of the crowd moved toward the jail.

The Enquirer caught the

mood: "At LAST The People Are

Aroused." According to the best

estimates, thousands actually went to

the jail.12

County Sheriff Morton Hawkins had been

expecting trouble that

night and had thirteen deputy sheriffs

with him at the jail. A veteran of

the Civil War who had risen from private

to company commander, he

reacted well to the situation. When he

received word of the crowd's

size, temper, and movements, he rang the

riot alarm to signal the police

around the city. He and his men then

waited inside the jail. Though

criticized later for ringing the riot

alarm because it attracted more

people to the scene, he had no choice.

In the days before radios and

cars, he had no other way to call the

police force to the jail. The crowd,

however, did swell, filling Sycamore

Street in front of the

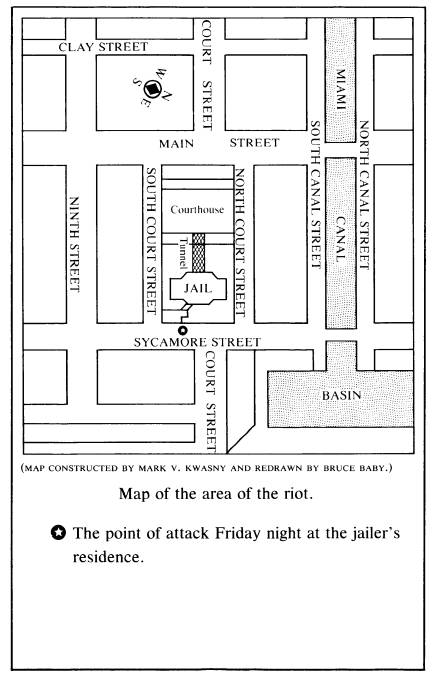

jail. At 10:00 P.M. the situation

reached the first crisis point. (See map,

page 26.)13

Attacking the street level entrance to

the jailer's residence, the

leaders of the crowd broke through the

door. People then poured

through the residence and up into the

cells in search of Berner. Berner,

however, had been sent to the Columbus

Penitentiary earlier in the

10. Cincinnati News-Journal, 27

March 1884; Enquirer, 27 March 1884; Cincinnati

Commercial-Gazette, 27 March 1884; Cincinnati Volksfreund, 25

March 1884, quoted in

Zane L. Miller, Boss Cox's

Cincinnati: Urban Politics in the Progressive Era (New

York, 1968), p. 60; Tunison, Riot, pp.

10-11; Laird Kleine, "Anatomy of a Riot,"

Bulletin of the Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, 20

(October, 1922), 235.

11. AR 1884, pp. 62-3; Enquirer,

29 March 1884.

12. AR 1884, p. 63; Enquirer, 29

March 1884; News-Journal, 29 March 1884.

13. G. M. Roe, Our Police. A History

of the Cincinnati Police Force, from the

Earliest Period until the Present Day

(Cincinnati, 1890), pp. 55-6; News-Journal,

29

March 1884; AR 1884, p. 63; Map

in The Great Cincinnati Riots! Being the only correct

history of that most Lamentable

outbreak in Ohio's Greatest City, Because of the

Villainous Verdict of the Berner jury

(Philadelphia, 1884), p. 9.

28 OHIO HISTORY

day, and the crowd did not bother the

other prisoners in the cells.

Hawkins and his deputies, pleading and

shoving, persuaded the people

to leave the cells after about thirty

minutes. At this point the police

wagons from around the city began to

arrive. The crowd on the streets

turned the first one back, but then

Chief of Police Reilly's wagon

arrived, driving up Sycamore to the jail

door. At this point a member

of the crowd fired the first shot, and

rioters nearer the jail fired several

more. A seventeen-year-old boy fell, hit

in the head. A thrown stone

knocked a policeman unconscious. With

the front of the jail blocked by

the crowd, Reilly led his men to the

Courthouse entrance on Main

Street and entered the jail through the

tunnel that connected the two

buildings. The police and deputies then

cleared the jail. Throughout

this initial violence, the police never

drew their guns.14

The worst was not over. The gathering in

the Music Hall-and the

majority of the people who first went to

the jail-had been a mixture of

wealthy, middle-class, and working

citizens who wanted justice. After

Hawkins and the police cleared the jail,

a change occurred in the

crowd, a change that many noticed. The

"solid men" gave way to

people who were only interested in

destroying and looting, and the

crowd "now degenerated into a

communistic mania to burn and

pillage," according to Adjutant

General Finley. This mob renewed the

assault on the jail, directing its

attacks against the main jail entrance

several feet below street level, while

others used a plank set over the

stairwell to crawl across to the windows

at street level. Breaking into

both levels, the rioters found iron

doors barring their passage to the

inside of the jail, so they began to

hammer at these doors.15

Around 11:00 P.M., with the doors about

to break, Hawkins sent a

call for help to the local 1st Regiment

of the ONG, which had two

companies on guard duty at the armory.

Colonel C. B. Hunt, regiment

commander, left Captain John Desmond and

five men on guard, while

he led fewer than forty soldiers

immediately to the jail. He also sent

men to assemble the rest of the

regiment. Arriving at the scene of the

riot, he led the Guardsmen into the

Courthouse and through the

tunnel. 16

The situation in the jail, meanwhile,

became critical during these

minutes before Hunt's arrival. Using

sledgehammers, the mob broke

down the doors and flooded into the jail

where Hawkins and Reilly had

14. News-Journal, 29 March 1884; AR

1884, pp. 63-4; Enquirer, 29 March 1884.

15. Great Riots!, p. 11; News-Journal, 30 March 1884; AR 1884, p.

64, and report of

Col. Church, p. 224; Enquirer, 29-30

March 1884.

16. News-Journal, 29

March 1884; AR 1884, p. 64, and report of Col. Hunt, p. 224.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 29

their men stationed with clubs. Hawkins

refused to allow his men to

draw their revolvers, even though the

rioters were wielding bricks,

stones, and pistols. Then the gas went

out, and the building went black.

There was a pause. The gas came back on,

and the attack renewed. It

was at this point that the ONG arrived.17

Hunt sent his men through the tunnel two

abreast because of its

narrow width. As they neared the jail

side, several rioters fired their

pistols and hit four soldiers. Hawkins

then ordered the Guard to fire

over the crowd's heads. The mob

hesitated at this fire, and the police

took advantage of the pause to push them

back. Ignoring the warnings

to stay back, the mob made a second rush

on the police and soldiers.

The Guardsmen fired four shots and

killed the crowd's leader. The

police and militia were then able to

clear the jail for the second time.18

This fight occurred around midnight.

Inside the jail were about 100

militia and police. Outside, only about

400 people were actually near

the jail, though hundreds of others were

still on the streets, and this

mob was still not ready to quit. After

firing their pistols and yelling for

about thirty minutes, the rioters

decided to set fire to the jail by pouring

oil down the stairs to the main entrance

and trying to light it. Hunt

quickly ordered a detachment of soldiers

out the door. They went out

and fired into the crowd. Under fire

from the mob but reinforced from

inside, the Guardsmen then advanced to

the railing at the top of the

stairwell and ordered the crowd back.

The warnings ignored, the

soldiers fired again into the mob,

hitting three rioters and one police

officer who was standing by a wagon in

the street. The crowd wounded

three Guardsmen during this encounter.

Then police and militia

together then went out and cleared

Sycamore, North Court, and South

Court Streets, which they held until

morning.19

Elsewhere, the looting spread. Looters

broke into the armory of the

Grand Army of the Republic and into B.

Kittredge and Co.'s gun shop,

where they found many guns but no

ammunition. Desmond and his

guard prevented a possible attack on the

ONG armory. Meanwhile, the

composition of the crowd continued to

change. The looters now were

mostly boys under sixteen and men

without jobs, a dramatic change

from the "solid men" at 9:30

P.M. Finally, between three and four in

the morning, the crowd began to

disperse. Four were dead, all

townspeople, with several militia and

police and an unknown number

17. Tunison, Riot, p. 62; Enquirer,

29 March 1884.

18. Reports of Col. Hunt and Surgeon

Jones in AR 1884, pp. 224, 227-28;

Commercial-Gazette, 30 March 1884.

19. News-Journal, 29 March 1884;

Report of Col. Hunt in AR 1884, pp. 224-25;

Enquirer, 29

March 1884.

30 OHIO HISTORY

of citizens hurt.20 It had

been a costly Friday night, but Hawkins and

Hunt had done a good job of protecting

the jail and prisoners and

preventing any major destruction.

The individual soldiers, too, had done a

good job, following orders

and firing only on command. The soldiers

felt justified in their actions.

In later interviews, one Guardsman said

he had fired on Friday evening

and would again. Another said this was

the most dangerous mob he had

ever seen. Not all of the Guard,

however, felt this way. One soldier

described how he shot into the air

because he and many others in the

regiment sympathized with the crowd. As

this was a local regiment,

many of the men probably did have such

sympathies. The regiment,

though, did its duty. The soldiers did

not use unnecessary force and

used their guns only when commanded by

Hawkins or Hunt to do so.

For inexperienced soldiers, in a cramped

tunnel with shouts, screams,

and shots ahead, their performance was

excellent.21

When Saturday dawned, the men inside the

jail did not fool

themselves. They knew the riot was far

from over. Hawkins therefore

called for more reinforcements early

that morning. At 9:00 A.M.

Captain Frank Joyce, commander of the

ONG battery in Cincinnati,

received an order from Hawkins to come

to the jail. Joyce reported for

duty at noon with only about twenty men

and no cannons. He

dismantled the guns and left them behind

with a three-man guard

because he had no ammunition for the

guns. His men instead armed

themselves with rifles and served for

now as infantry. By 10:00 A.M.

those of the 1st Regiment that would

ever show during the riot had

reported for duty. Altogether only 117

out of a total of 525 soldiers and

officers served. With these men and

Joyce's few, Hawkins now had

almost 200 deputies, police, and militia

to face a possible renewal of

fighting.22

The poor turnout of the Guard Saturday

morning was due to two

factors. Saturday's newspaper accounts

of the riot the previous night

"terrorized" the men,

according to Hunt, convincing them to stay

home. The Enquirer even admitted

on Sunday that certain newspaper

accounts had demoralized the members of

the Guard. The second

factor was the underlying sympathy many

Guardsmen had for the

people and their cause for discontent.

Six of Joyce's men "absolutely

20. Tunison, Riot, p. 86; John A.

Johnson, On The Roof of Europe; Behind the

Guardsman's Rifle (Covington, Ky., 1920), pp. 75-76; Enquirer, 29

March 1884; Report

of Col. Hunt in AR 1884, p. 225.

21. Enquirer, 30 March 1884;

Tunison, Riot, p. 84.

22. Reports of Col. Hunt and Capt. Joyce

in AR 1884, pp. 225, 237-38; "Consolidated

Report, March 31, 1884," MQAR, box

17; News-Journal, 29 March 1884.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 31

refused to turn out or give any excuse,

save that they did not propose

to guard and protect murderers and

thieves."23 The problems with

using local militia units to fight

fellow citizens became apparant in

Cincinnati.

The defenders of the jail, meanwhile,

prepared their defenses as well

as possible. Hawkins took overall

command, while Hunt commanded

the Guard and Reilly controlled the police.

They then held a conference

with the other officers and staff

members of the Guard to decide how

best to prepare for the coming night.

Hunt suggested concentrating

their small force to defend the jail.

The other leaders agreed that they

had too few men to defend the

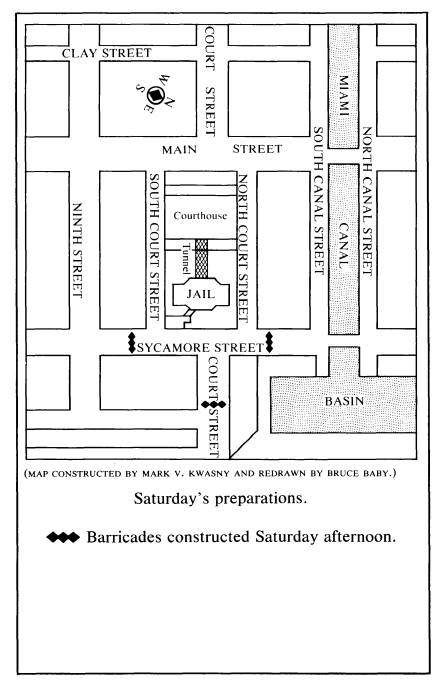

Courthouse. They therefore ordered the

creation of three barricades around the

jail: one at the corner of South

Court and Sycamore, another at North

Court and Sycamore, and the

third at East Court and the canal basin.

They stationed about twenty-

five men at each. Desmond commanded the

reserve inside the jail. (See

map, page 33). Some police helped guard

the barricades while others

roamed the city, ready to move on

command.24

The morning conference also led to a

second measure for defense: a

request for more aid from the ONG.

Around 11:00 A.M. Saturday,

Hawkins sent his first request to

Adjutant General Finley for more

men. As Hawkins wired, "Great

danger apprehended to-night."

Colonel J. W. Harper, a member of

Hoadly's staff who was in

Cincinnati, wired the same message to

the governor. Just before noon

Hawkins asked Finley to send the 14th

(Columbus) and 4th (Dayton)

Regiments because he expected

"deadly work to-night."25

Governor Hoadly was reluctant to commit

more of the Guard so

quickly. He explained his dilemma that

afternoon: "I shall keep the

men under arms until the danger is past,

but am anxious to avoid

unnecessary expense to the State, and

unnecessary excitement. I don't

wish to stampede the State for nothing,

nor to fail to have the men on

hand if necessary." He also wanted

to avoid endangering his political

support in Cincinnati by acting too

rashly. In order to gauge the mood

of the civilian leaders of the city, he

asked for advice from leading

citizens, such as Henry C. Urner, on

whether the situation warranted

the mobilization of the ONG. Meanwhile,

he ordered the 4th and 14th

Regiments and a Springfield, Ohio,

battery to prepare to move at a

23. Enquirer, 30 March 1884;

Reports of Col. Hunt and Capt. Joyce in AR 1884,

pp. 225, 238.

24. Enquirer, 30 March and 3

April 1884; AR 1884, p. 65, and reports of Brig. Gen.

Ryan and Col. Hunt, pp. 221, 225; Roe, Our

Police, p. 69.

25. Hawkins to Finley, 11:01 and 11:55,

Harper to Hoadly, 11:16, 29 March 1884,

telegrams, in AR 1884, pp.

147-48.

32 OHIO HISTORY

moment's notice. All of this occurred

within one hour after Hawkins'

request. Hawkins quickly asked Hoadly to

send the regiments at

once.26

So far, all was going well from Hawkins'

viewpoint. Then compli-

cations arose. Around 1:30 P.M. Hoadly

received telegrams, one of

which was from Brigadier General Michael

Ryan in Cincinnati, that

said the riot had ended and no militia

would be needed. Unsatisfied,

Hoadly asked for more opinions. He

believed this pause to ask advice

would not delay the sending of the

Guard, if that proved necessary,

because the troops were not ready to

leave. If, on the other hand, the

reports were right and the riot were over,

Hoadly wanted Hawkins to

withdraw his request. Hawkins, however,

reconfirmed his request for

"all the military" possible.27

It was now past 2:00 P.M., more than two

hours after Hawkins' initial

request. The militia force was ready to

move, but Hoadly continued to

hesitate because the advice from the

citizens of Cincinnati continued to

be unanimously against sending the ONG.

Hawkins, Hunt, and Harp-

er, however, all agreed that the

soldiers were necessary. At 3:00 P.M.

Hoadly asked Ryan to consult with the

sheriff. Around 4:00 P.M.,

civilian advice began to change. Urner

and Ryan did finally consult

with Hawkins and they withdrew their

objections. With everyone now

in agreement in Cincinnati, Hoadly hesitated

no longer. By 5:00 P.M.,

the battery and the two regiments had

orders to move to Cincinnati.28

Five hours after Hawkins' first request

for two regiments, those

regiments received orders to move to the

city. As Hoadly said, the first

two hours probably did not matter

because the units were not yet ready

to move. The additional three hours of

delay are harder to justify.

Hoadly did need concrete knowledge that

the Guard was necessary.

He also wanted agreement from the

leaders of Cincinnati, his home

town and political base. The fastest way

to get advice was to consult as

many trusted people as possible, both

military and civilian. As long as

there was disagreement, he had some

reason to hesitate. From that

standpoint, it is understandable that he

hesitated until he received

unanimous agreement on the necessity of

sending the ONG.

26. Hawkins to Finley, 11:55, to Hoadly,

1:20, Hoadly to Urner, 11:55, to Mott,

12:04, to Sintz, 12:40, to Hawkins,

12:47, to Ryan, 3:00, 29 March 1884, telegrams, in

ibid., pp. 147-48, 151.

27. Ryan to Hoadly, 1:29, John Bell to

Hoadly, 1:30, Hoadly to Urner, 1:45, to Ryan,

1:55, to Bell, 1:55, Hawkins to Hoadly,

2:10, 29 March 1884, telegrams, in ibid., p. 149.

28. Finley to Mott, 2:25 and 4:46, Urner

to Hoadly, 2:26 and 2:49, Hoadly to Ryan,

3:00, to Hawkins, 5:00, Urner and Ryan

to Hoadly, 4:41, 29 March 1884, telegrams, in

ibid., pp. 150-52.

|

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 33 |

|

|

34 OHIO HISTORY

Although understandable, his hesitation

still was not justified. The

advice he sought was not worth the

delay. Ryan, Urner, and the other

citizens he asked had not witnessed the

riot and had not yet been to the

jail. They were all against the use of

more troops until they went to the

jail, saw the results of the fight, and

talked with Hawkins and Hunt.

They then decided Hawkins was right.29

Meanwhile, the commanders

who were on the spot knew the situation

and urged the immediate

dispatch of the units requested. As

commander-in-chief, Hoadly

should have analyzed better the merits

of the different opinions.

The delay notwithstanding, Hoadly decided

to send the Guard. At

6:00 P.M. the 14th Regiment left Columbus. The 4th Regiment left

Dayton at 6:30 P.M., and the

Springfield battery joined them en route.

Hoadly told Hawkins to expect the

reinforcements in Cincinnati at 9:00

P.M. In addition to these units, Hoadly

had a Cleveland battery and

three additional infantry companies

prepared to move if necessary.30

Altogether, the equivalent of two and

one-half regiments and two

batteries, over 1200 men on paper, had

been mobilized. Once Hoadly

decided his course of action, he moved

with determination.

Cincinnati was fortunate that he did act

because Hawkins proved

correct. The riot had not ended. Hawkins

and Hunt did not expect

problems until evening, though, since

Saturday was a workday.

Unfortunately for them, Saturday was

also a payday, and they feared

that many workers would get drunk and

contribute to the problems. As

evening approached, the groups around

the barricades increased. Just

after dark the crowd swelled and filled

Main Street from the canal to

Ninth Street, and also extended west

past Clay. More people filled the

streets around the three barricades. It

was a clear, cold night, and as

the defenders feared, the crowd

contained many intoxicated men. The

situation grew ominous as the troops

repulsed a few initial pushes

against the barricades. The defenders

inside the perimenter could

only wait and hope that the promised

reinforcements would arrive by

9:00 P.M.31

Between 9:00 and 10:00 P.M., some

rioters began throwing stones and

shooting revolvers and shotguns at the

Courthouse windows, while

others started bonfires in the streets.

The defenders ignored these

provocations, and the crowd grew bolder.

Finally, several rioters

29. Ibid., p. 66.

30. Hoadly to Hawkins, 6:15 and 7:00, to

Harper, 7:26, 29 March 1884, telegrams, in

ibid., pp.

153-55, and reports of Col. Freeman and Capt. Smithnight, pp. 231, 259.

31. Kleine, "Anatomy," p. 241;

Johnson, On the Roof, pp. 77, 85; Commercial-

Gazette, 30 March 1884; News-Journal, 30 March 1884; AR

1884, p. 67; Great Riots!, p.

19.

|

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 35 |

|

|

|

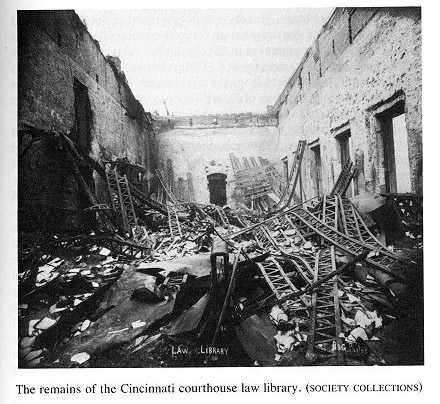

broke into the Treasurer's office in the Courthouse and set it on fire. The fire quickly spread to the other offices. At the same time other rioters tried to move east on North and South Court Streets toward the jail, but the troops at the barricades cleared the streets with gunfire. The mob retreated and charged again, shouting "Burn the town!" and "Kill the S-n of B-s!"32 These rioters were no longer trying to give justice a little help. They wanted revenge for Friday's wounded and slain. The fire in the Courthouse continued to spread as the mob prevented the firemen from working. Hawkins therefore ordered Desmond and the reserve through the tunnel to the Courthouse to protect and assist the firemen. When the soldiers emerged outside, a rioter shot Desmond in the head. Desmond fell dead, the only fatality of the ONG during the riot. After a second shot wounded another soldier, the troops retired back inside. The firemen also retreated.33 The Courthouse continued to burn through the night. Hawkins failed to save the Courthouse through no fault of his own. During the attack on the Courthouse, the troops around the jail had to

32. AR 1884, p. 67; Enquirer, 30 March 1884. 33. AR 1884, p. 67, and report of Col. Hunt, p. 226. |

36 OHIO HISTORY

repulse several attacks against the

barricades and down North and

South Court Streets. Hawkins committed

his only reserve, but it had to

retire after its leader fell. He also

had sent deputies to meet and hurry

the reinforcements to the jail, but the

reinforcements were late.34 He

could have done nothing else.

The expected reinforcements were indeed

late. The 4th Regiment,

commanded by Colonel Frank B. Mott,

arrived in the city by 9:30 P.M.

The battery accompanying the 4th arrived

later. By 9:45 P.M. the

regiment was at Ninth and Walnut, only

three squares from the jail,

when it halted. The mob mingled with the

soldiers, hurling taunts and

insults at them. Finally, the regiment

retreated to the train depot. The

regiment's 300 men never made it to the

scene of action Saturday

night.35

The reasons for the 4th's failure

provide a good example of the

problems National Guard units faced when

confronted by hostile

citizens. First, no staff officer met

Mott at the depot, though a deputy

apparently did. Guided by the deputy,

the regiment made it to Ninth

and Walnut where it halted because both

Mott and the deputy wanted

further orders from Hawkins. The deputy

went to find Hawkins but did

not return, so Mott decided to return to

the depot and attempt to

contact the sheriff by phone. Surrounded

by a threatening mob, Mott's

indecision did not inspire the soldiers.

Inexperienced, just called from

home, and not having eaten since noon,

many in the 4th could not have

been disappointed by the decision to

retire.36 Mott and the 4th did,

however, fail to do their duty, which

the noise from the Courthouse

square should have made clear.

The 4th's retreat left Hawkins in a

perilous situation. The fire had

roused the mob to fever pitch, and the

repulse of the 4th only increased

the rioters' boldness. The rioters

continued the fight around the

barricades and on North and South Court

Streets.37 No estimates of

the crowd's number were given, but it

probably reached its peak

around this time. Hawkins could only

defend the perimeter and await

the arrival of reinforcements.

The violence continued to spread beyond

the immediate vicinity of

the jail and Courthouse. At one point, a

group of rioters left the

34. Harper to Hoadly, 9:51, 29 March

1884, telegram, in ibid., p. 155, and report of

Col. Hunt, p. 225.

35. Ibid., p. 66; Enquirer, 30

March 1884.

36. Court of Inquiry, in AR 1884, p.

298; Enquirer, 30-31 March 1884, including an

interview with Mott on 30 March; Commercial-Gazette,

3 April 1884, including inter-

views with a captain and several

privates of the 4th Regiment.

37. Johnson, On the Roof, p. 88;

Tunison, Riot, p. 88.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 37

Courthouse and moved south on Main to

William Powell and Co.'s gun

shop. Several store clerks, armed with

rifles, warned the approaching

crowd to leave. The mob advanced anyway

until the clerks shot two

men dead and three wounded.38 The

mob then apparently decided that

Powell's gun shop was not worth the

price.

The Courthouse was burning and the

fighting was spreading when,

between 10:30 and 11:00 P.M., the 14th

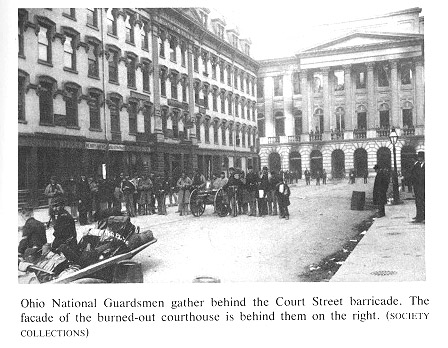

Regiment, commanded by

Colonel George D. Freeman, arrived in

Cincinnati. A deputy sheriff

and Quarter Master Ryan met the new

arrivals with written orders to

proceed immediately to the jail. Hawkins

planned to avoid the confu-

sion the 4th had suffered. Freeman,

though, would not have allowed

such a failure to occur. He was a

seven-year veteran of the ONG, and

had commanded the regiment in two

previous crises. He and his

regiment were well prepared.39

The 14th arrived with a Gatling gun and

four extra companies, in all

about 425 men. At the depot Freeman told

his men to stand firm and to

fire only on command. After receiving

twenty rounds of ammunition

each, the men began the march to the

jail. On the way the crowds of

people insulted them, threw stones, and

fired pistols, but the soldiers

"remained cool and declined to be

provoked into making retort."

Freeman's command reached the perimeter

near the jail without

serious incident, and Freeman reported

to Hawkins. Hawkins told him

to send the Gatling gun to the Court

Street barricade, and then to clear

the streets around the Courthouse.

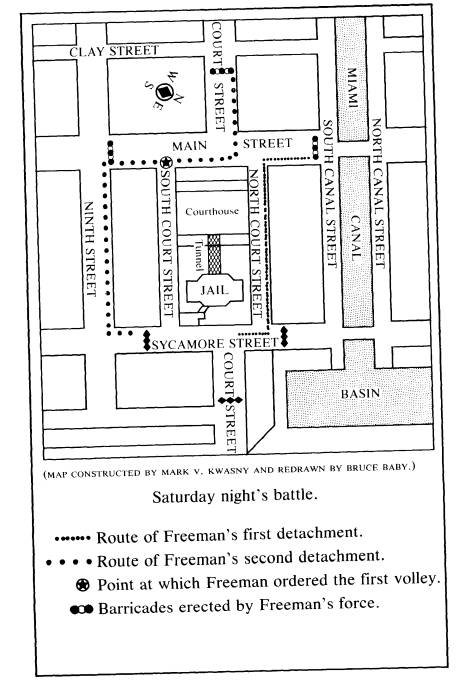

Freeman sent two companies to

support the Gatling gun, and then

divided the rest of his force into two

groups. One group marched past the

barricade at Sycamore and North

Court and moved up North Court to Main.

This detachment pushed the

crowd in front of it at bayonet point

north on Mair and out over the

canal. (See map, page 39.) They then

began to erect a barricade near

the bridge.40

The second group moved up Ninth to Main.

Freeman left three

companies at the intersection of Ninth

and Main to hold back the

crowds south and west of the crossroads,

while he sent one company

north on Main toward Court Street. As

this company neared South

Court Street, the mob began to resist,

throwing stones and firing

revolvers. An additional company from

the crossroads moved to the

38. Enquirer, 30 March 1884.

39. AR 1884, pp. 68, 127, and

reports of Col. Church and Col. Freeman, pp. 222, 231;

Enquirer, 30-31 March 1884; News-Journal, 31 March 1884.

40. AR 1884, p. 68, and Church to

Hoadly, 11:41, 29 March 1884, telegram, p. 156,

and reports of Col. Freeman and Maj.

Harper, pp. 231, 264.

38 OHIO HISTORY

support of the first company, but the

rioters continued to press

forward. Finally Freeman brought a third

company forward to support

the detachment, and he and several

officers warned the crowd to retire.

They instead advanced. Freeman ordered

the first platoon to fire, and

the mob fell back to Court Street, their

leader dead and several rioters

wounded. The detachment pushed to Court

Street and then west on

Court to Clay, where it held back the

crowd. Main was now clear from

the canal to Ninth, and Freeman reported

to Hawkins that the firemen

could return to fight the fire at the

Courthouse.41

Rioters hiding near the Market House a

block west of Court and Clay

continued to fire on the militia. A

platoon of soldiers finally returned

the fire after the rioters had wounded

ten soldiers. The troops then

gathered materials and constructed a

barricade. The units at Main and

Ninth also built a barricade, at which

point all streets leading to the jail

and Courthouse had defenses.42 For

the moment, the heavy fighting on

the perimeter subsided.

The importance of Hoadly's hesitation to

commit the Guard can now

be seen. The "fatal delay," as

Hunt called it, was three hours longer

than necessary. The 4th arrived in

Cincinnati around 9:30 P.M. Three

hours earlier the rioting had not begun,

and the 4th probably could have

reached the jail without incident. With

the addition of this regiment's

300 men, Hawkins could have defended the

Courthouse. The 14th

arrived around 11:00 P.M. At 8:00 P.M.

the rioting had just begun. At the

height of the crisis, this force cleared

the block around the Courthouse.

Had it been available earlier, perhaps

the fighting around the jail and

Courthouse could have been cut short.

When Hoadly sent these two

regiments, he wired Hawkins orders not

to move them from the depots

"unless absolutely necessary."43

Instead, Hoadly could have placed

these units in Cincinnati by 8:00 P.M.

under similar restrictions, and

then they would have been available at

the beginning of the action.

Events, however, could not be changed,

and the battle around the

Courthouse had now raged for hours.

Surprisingly, the rioters still had

not had enough. The saloons were busy,

and more drunken men and

looters were joining the crowds.

Meanwhile, the violence and looting

continued to spread throughout the city.

Around midnight thieves

broke into T. and A. Pickering's store,

but nearby police reacted

quickly and caught many of the criminals

inside. A little before 3:00

41. Ibid., p. 69, and reports of Col. Church and Col. Freeman, pp.

223, 231-32.

42. Ibid., p. 69, and report of Col. Freeman, p. 232.

43. Hoadly to Hawkins, 5:00 and 6:15, 29

March 1884, telegrams, in ibid., pp. 152-53,

and report of Col. Hunt, p. 225.

40 OHIO HISTORY

A.M. rioters broke

into the Music Hall and found Joyce's dismantled

guns. They reassembled the guns (Joyce

doubted the guns could have

been fired) and began hauling them

toward the jail. The Hammond

Street Police Station warned Hawkins,

who immediately sent three

companies of the 14th, the Gatling gun,

and a company of police to stop

this group. The police, not encumbered

with a hand-drawn Gatling gun,

moved faster, met the rioters pulling

the cannons, and captured the

guns and several of the rioters. They

brought the cannons to safety

within the perimeter.44

The fighting around the barricades

continued to rage. The rioters at

the Market House launched several

unsuccessful attacks on the

Court-Clay barricade, after which they

contented themselves with

sniping at the soldiers from under

cover. A Commercial-Gazette

reporter tried to enter the barricade at

Sycamore and Ninth but police,

hiding near the walls of the buildings

outside the perimeter, warned him

to stop. They told him an earlier group

had ignored a similar warning

and had continued to advance. The

reporter could see the dead bodies

in the street. Finally, a little after

3:00 A.M., the fighting began to

subside.45

Throughout the battle, the 4th Regiment

and the Springfield artillery

remained at their respective depots. The

4th, after its retreat, did not

venture forth again. The battery,

however, never left its depot. Captain

George Sintz, the battery commander,

arrived in the city at 11:00 P.M.

with two guns and thirty-one men. No

guides met them, and they could

not contact Hawkins at the jail or Mott

with the 4th. They had no

horses to move their guns (horses were

supposed to be supplied at the

depot), so Sintz placed his guns in a

defensive posture. He then went

to the 4th to ask the officers if they

would escort his battery to the jail,

but they refused.46 Neither

the regiment nor the battery participated

further in Saturday night's battle.

Governor Hoadly remained in Columbus

throughout the night,

performing the duties of a

commander-in-chief. He spent the entire

night in a railroad company's office

with a wire for his own use. He

kept in constant communication with his

aides in Cincinnati, with the

commanders of regiments and batteries

around the state, and with the

men in charge of the railroads. He did

not go to bed until almost five in

the morning, long after the firing had

ceased in Cincinnati.47

44. Commercial-Gazette. 30 March

1884; Enquirer, 30 March 1884; Reports of Col.

Freeman and Capt. Joyce in AR 1884, pp.

232, 238.

45. AR 1884, p. 69, and report of

Col. Freeman, pp. 232-33; Commercial-Gazette, 30

March 1884.

46. Report of Capt. Sintz in AR 1884,

p. 257.

47. News-Journal, 31 March 1884.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 41

Hoadly's decision to stay in Columbus

rather than to go to Cincinnati

was wise. Had he gone to Cincinnati, he

would have been out of touch

with everyone while on the train, and

his headquarters would have

been in transit, making communication

with it difficult. He then would

have had to get inside the perimeter to

consult with the commanders,

possibly losing contact with the

outside. He had able men on the scene

who could command the tactical movements

and who had had some

experience, and he had more important

duties to perform. By concen-

trating on the mobilization of the ONG,

he was able to coordinate the

necessary movements, trains, and logistics.

Thus, Hoadly was correct

to remain in Columbus at a central

headquarters.

His actions during the night prepared

the way for the amassing of

almost 2000 troops, as well as the

necessary ammunition and equip-

ment, in Cincinnati by the end of

Sunday. He based his moves on

information received from his aides

throughout the night. Harper and

Colonel S. H. Church, who had arrived in

Cincinnati with the 14th

Regiment, both wired the governor

several times, informing him of the

destruction, deaths, and injuries, and

of the failure of the 4th. By

midnight, Hoadly realized that the 4th

and 14th Regiments were not

enough. Wiring Harper that he would stay

at the wire "all night, if

necessary," he began to mobilize

the rest of the ONG.48

Between 12:30 and 5:00 A.M. Hoadly accomplished a great deal. He

ordered five regiments to assemble their

commands, and asked local

railway companies to prepare special

trains. Warned by Church that

the troops in Cincinnati were low on ammunition,

Hoadly prepared two

different shipments of ammunition,

totaling 50,000 rounds, along with

the necessary escorts, to move to

Cincinnati. He sent Adjutant General

Finley to Cincinnati to take command of

the ONG in the field, while

Hoadly tried to coordinate the arrival

of new units with escorts at the

depots. He ordered the 4th to move to

the jail, but that regiment

ignored the order. Throughout this

mobilization, he ignored costs:

ONG officers were to "spare no

expense" and use whatever trains

were necessary, as the state "Will

pay bills."49 By the time Hoadly

went to bed Sunday morning, he had the

entire ONG and 50,000 rounds

of ammunition on the move or preparing

to move.

48. Harper to Hoadly, 9:51, 11:06, and

12:00, Church to Hoadly, 11:41, Hoadly to

Harper, no time, 29 March 1884,

telegrams, in AR 1884, pp. 155-56.

49. Hoadly to Orland Smith, 12:30 and

2:00, to Harper, 12:30 and 12:35, to Entrekin,

12:35, to Pocock, 12:55, 2:10, 3:20, and

4:10, to Williamson, 1:00, to Church, 2:30, 3:45,

and 3:55, to Hetrick, 3:00, Harper to

Hoadly, 1:40, Church to Hoadly, 2:06 and 2:21,

F. Green to J. E. Rose, 4:41, 30 March

1884, telegrams, in ibid., pp. 157-61, 163-64, and

report of Col. Picard, p. 239.

42 OHIO HISTORY

As the sun rose on Sunday morning, the

ruins of the Courthouse

must have been a reminder to all within

the perimeter that they were in

the middle of a city gone berserk. At

9:45 A.M. Finley arrived at this

scene of destruction and took command of

the state troops. Finding the

soldiers exhausted and without food, he

arranged for as many meals as

possible. He also found that the

principal commanders in Cincinnati

expected more trouble that night. He

agreed and wired Hoadly of this

fear. The mayor, Thomas Stephens, made

his first appearance that

morning, having been ill with pneumonia.

He called for a meeting of

citizens and published a list of 100

names of the people he thought

should attend. By 9:45 A.M., Hoadly was

also up and at work again.50

He learned quickly that the trouble in

Cincinnati had not ended.

The mayor's conference met before noon

with twenty-five to thirty

"leading citizens" in

attendance. As a result of the conference, the

mayor closed all the saloons until

Monday, and he asked Hoadly for all

available ONG. He also called for the

citizens of the city to emerge and

join a special police force to help stop

the riot.51 After a two-day

absence, the civil government was back

on the job. The civil authori-

ties were finally helping the police and

military regain control of the

city.

The mobilization and deployment of the

ONG continued without a

pause on Sunday. At 6:30 A.M. Colonel

Frederick J. Picard arrived in

Cincinnati with twenty-seven men and

20,000 rounds of ammunition.

He knew the soldiers at the Courthouse

needed the supplies badly, so

when the 4th disobeyed an order to

escort Picard to the jail, he decided

to march with only his one company.

Three blocks from the jail a

crowd formed between him and the

perimeter. Using bayonets,

Picard's men continued their advance,

twice losing and recapturing the

precious ammunition wagon. They finally

reached the barricade in

front of the Courthouse and entered the

perimeter. Several of Picard's

men had injuries from thrown stones.52

Finley set up military headquarters in

the City Buildings about one

mile west of the defensive perimeter. He

then began preparations to

meet the expected reinforcements as they

arrived throughout the day.

He also ordered Sintz's battery and the

4th Regiment to the jail.

Around noon, Mott, commanding 115 men of

the 4th, arrived at Sintz's

50. Finley to Hoadly, 9:45 and 10:58,

Hoadly to Finley, 9:45, 30 March 1884,

telegrams, in ibid., pp. 165-67; Great

Riots!, p. 24; Enquirer, 31 March 1884.

51. Finley to Hoadly, 12:08, 30 March

1884, telegram, in AR 1884, p. 168; Enquirer,

30-31 March 1884.

52. Reports of Col. Freeman and Col.

Picard in AR 1884, pp. 233, 239-40.

|

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 43 |

|

|

|

depot. The rest of the regiment had gone home during the morning. Horses were delivered, and together the battery and regiment marched to the jail, arriving by 2:15 P.M. During the afternoon, Finley, with Hoadly's permission, ordered a Cleveland battery to Cincinnati, and he sent a newly arrived regiment to the City Buildings as a reserve. Freeman remained in command at the jail.53 Hoadly continued to work from Columbus. Between noon and 1:30 P.M. he ordered the rest of the ONG to move to Cincinnati as soon as possible, while he communicated with the railroads to arrange special trains for the men to use. He also prepared to send more supplies and ammunition to the infantry and artillery and even considered declaring martial law, though he refrained from this as the civil authorities were

53. News-Journal, 31 March 1884; AR 1884, pp. 66-67, and Hoadly to Finley, 12:35, Finley to Hoadly, 2:16 and 6:51, 30 March 1884, telegrams, pp. 169-70, 173, 183, and reports of Col. Freeman, Col. Entrekin, Capt. Sintz, and Capt. Smithnight, pp. 233, 249, 257-59; Enquirer, 31 March 1884. |

44 OHIO HISTORY

beginning to take charge. Hoadly was in

command of the situation, and

by 6:00 P.M. he had the entire state

force in motion.54

The command arrangement in Cincinnati

between civil and military

authorities was also working well.

Finley announced to the soldiers

that he would take orders from the mayor

and that the ONG was in

Cincinnati to support the civil

authorities. Mayor Stephens, with

Finley's support, asked the mayors of

Newport and Covington to block

the bridges from their towns into

Cincinnati to prevent more people

from entering and joining the mob.

Stephens and Finley also stationed

squads of police to defend important

buildings such as Kittredge's and

Powell's gun shops.55 The

coordination between the city officials, the

police, and the state troops was a major

advantage for the defenders of

the law.

The soldiers already in Cincinnati spent

an uncomfortable Sunday,

though Quartermaster Ryan tried to feed

them as well as possible. He

had a hospital and two hotels provide

plenty of coffee while he used the

jail's kitchen and a local establishment

to prepare meals. The men,

however, got little sleep as they

remained on constant duty patrolling

the streets and manning the barricades.

Some members of the 1st had

not slept since Friday afternoon, and

the troops who had arrived

Saturday had not slept since their

arrival. In addition, the weather was

still cold, and the soldiers had few

overcoats.56 Altogether, it was a

miserable, uncomfortable day for the

soldiers and police on duty that

Sunday.

Cincinnati was fortunate to have these

Guardsmen and police on

hand. Throughout the day the crowds

increased and tension mounted

as rioters threatened the soldiers, and

police arrested some rioters near

the barricades. Finley reported a few

"disturbances" and the death of

one citizen, but no major fighting

erupted during the day. Many in the

crowd, however, had armed themselves

from the guns looted from the

stores the previous two nights. Finley

expected trouble that night.57

54. Hoadly to C. E. Henderson, 11:06, to

Williamson, 12:00, to McMaken, 12:15, to

Hetrick, 1:00, to Finley, 12:55 and 5:35,

to Thorp, 1:03, to Norton, 1:10, to R. Shurtleff,

1:15, to Harper, 1:24, to C. C. Waite,

1:30, to Pocock, 2:00, to R. Smith and B.

Eggleston, 4:50, R. Smith and B.

Eggleston to Hoadly, 3:50, 30 March 1884, telegrams,

in AR 1884, pp. 168-72, 177, 180-81.

55. Finley to Hoadly, 4:12 and 5:06, 30

March 1884, telegrams, in ibid., pp. 178-79,

181, and Gen. Order no. 1, 30 March

1884, p. 208; Enquirer, 31 March 1884;

News-Journal, 31 March 1884.

56. Enquirer, 31 March 1884; Ryan to Hoadly, 10:41, 30 March 1884,

telegram, in AR

1884, p. 188, and report of Col. Hunt, p. 226; Commercial-Gazette,

31 March 1884;

News-Journal, 1 April 1884.

57. AR 1884, p. 70, and Finley to

Hoadly, 4:12, 30 March 1884, telegram, p. 178, and

report of Col. Freeman, p. 233.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 45

A new regiment, escorting the ammunition

and artillery supplies,

arrived in Cincinnati at 7:00 P.M. As of

this time Finley's force was

formidable. He had units from six

different regiments and one battalion

of infantry, and two artillery

batteries, a total of approximately 1100

soldiers, six cannons, and one Gatling

gun. He positioned his men

throughout the town in cooperation with

the mayor, stationing about

700 men inside the perimeter and 400 in

reserve in the City Buildings.

One company went to the Hammond Street

Station to cooperate with

the police, while small detachments

garrisoned the Music Hall, ar-

mory, and gas works.58

At 8:00 P.M. Hawkins ordered Freeman to

send three companies to

guard the powder stored in Clifton

Heights, north of the city. Accord-

ing to reports, a crowd of 2000 was

threatening to attack. The troops

drew sixty rounds each and, with a

deputy sheriff as guide, marched to

Clifton. Their arrival stopped the

impending attack, but the soldiers

remained on guard until midnight when

local police took over the duty.

The soldiers returned to the jail later

that night.59

Despite the presence of such a strong

force of armed soldiers in the

city, the riot resumed Sunday night. By

now Hawkins, Finley, and

Hoadly must have been wondering what it

would take to stop the

violence. No one could have predicted

the determination and perse-

verance of the mob in the face of such a

formidable force. This mob had

been stirred to a fighting spirit and

had not yet vented its full wrath.

The violence in town began around 8:30

P.M. when a group of 150

rioters left the crowd near the jail and

moved several blocks away,

where they began to push streetcars off

the tracks. Thirty minutes later

they moved to Power Hall behind the

Music Hall, where they found the

disassembled parts of a cannon. The

police warned Finley, who then

had Colonel Samuel Courtwright, another

one of the governor's aides

on duty in Cincinnati, dispatch two

companies of about seventy-five

men from the reserve. These troops

quickly marched to the scene. As

they deployed in front of the halls, the

crowd scattered, leaving behind

the cannon and three men whom the police

arrested. There were no

casualties. The soldiers, joined by

fifteen police from a nearby station,

guarded the halls throughout the night.

At the same time, another

company went to strengthen the guard at

the gas works. Other police,

meanwhile, were busy with thieves who

were looting some pawn-

shops.60

58. Gen. Order no. 1, 30 March 1884, in ibid.,

p. 208, and reports of Col. Entrekin and

Col. Pocock, pp. 249-50, 261; Commercial-Gazette, 31

March and 1 April 1884.

59. Report of Col. Picard in AR 1884,

p. 240.

60. Enquirer, 31 March 1884;

Finley to Hoadly, 10:40, 30 March 1884, telegram, in

46 OHIO HISTORY

The fighting increased between 10:00 and

11:00 P.M. when rioters

near the Market House began shooting at

the soldiers behind the

Court-Clay barricade. Officers warned

the rioters to stop, but they

continued to fire. The soldiers then

fired twenty rounds from the

Gatling gun, inflicting several wounds

and scattering the crowd. For

the next couple of hours the Market

House crowd fired only a few

random shots, to which the troops did

not respond; they were under

orders not to fire individually, only on

command. Meanwhile, Finley

received word of shots near one of the

train depots. He sent one

company and some police to the scene to

stop that fight.61

Reinforcements began to arrive in the

city at midnight. One battery

and the equivalent of three companies

arrived with 30,000 more rounds

of ammunition. These units reported to

Finley at headquarters in the

City Buildings. At 1:00 A.M. a river steamer dropped off two companies

from the river towns, and at 2:30 A.M. the 3rd Regiment arrived.

Lieutenant Colonel James E.

Shellenberger, temporarily in command

of the 3rd, ordered his advance guard to

fire only single shots if they

met resistance between the depot and the

City Buildings. The 3rd

joined the growing reserve.62

Even the United States Army became

involved in the increasingly

serious state of affairs in Cincinnati.

As early as 5:30 P.M. on Sunday,

Hoadly had informed Finley that he was

free to requisition artillery

ammunition from the U. S. Army's Newport

Barracks. According to

the Enquirer, some ammunition was

sent to Cincinnati.63 The riot had

grown to proportions no one could have

imagined Friday.

The final outbreak of fighting occurred

at 1:00 A.M., again near the

barricade at Court and Clay. As a large

crowd prepared to advance on

the barricade, Hawkins, Hunt, and other

officers stationed themselves

at Court and Main to command the

situation. The rioters fired over fifty

shots, but the Guard did not respond.

Finally, with a shout to "clean

out those blue coats," the mob

charged the barricade. When they had

closed to a short distance, Freeman

ordered two volleys, by company,

in rapid succession. The crowd

retreated, leaving behind several

wounded. This was the last extensive

firing as the streets slowly

became quiet.64

AR 1884, p. 188, and report of Col. Entrekin, p. 250; Tunison, Riot,

p. 92.

61. Finley to Hoadly, 11:35, 30 March

1884, telegram, in AR 1884, pp. 188-89, and

report of Col. Freeman, pp. 233-34.

62. Reports of Col. Entrekin, Lt. Col.

Shellenberger, Capt. Smithnight, and Maj.

Harper, in ibid., pp. 250, 255,

260, 264-65; Enquirer, 31 March 1884.

63. News-Journal, 31 March 1884; Enquirer,

31 March 1884; Hoadly to Finley, 5:30,

30 March 1884, telegram, in AR 1884, p.

181.

64. Report of Col. Freeman in AR

1884, p. 234.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 47

Finley telephoned Hoadly at 3:00 A.M. to say that

he had enough men

for the moment. Hoadly then tried to

contact the regiments still on the

move, wiring: "War probably

over." Three regiments already en route

could not be stopped, but he was able to

contact and halt a fourth.65

The people of Cincinnati awoke Monday

morning to quiet streets. At

7:00 A.M. Freeman had his

men unload their weapons. During the

morning reinforcements reported to the

jail, which enabled Freeman to

relieve the men who had been without

sleep since Saturday. Almost

800 more men arrived in the city by

noon, completing the deployment

of the ONG in Cincinnati. The force deployed

as of Monday totaled

approximately 2500 soldiers, ten

cannons, and one Gatling gun from

ten regiments and one battalion of

infantry, and three batteries. Only

one regiment of the ONG was not on hand.66

The city seemed quiet but Finley took no

chances. He kept his forces

in place around the city: about 900 men

at the Music Hall; 1070 men,

six cannons, and one Gatling gun at the

jail; and over 400 men, four

cannons, and one police Gatling gun at

the City Buildings. He had two

companies support the police at the

Hammond Street Station, and one

company at the gas works. He also sent

two companies to the Plum

Street Station, and one to Fountain

Square. These preparations,

however, did not receive a test, and the

men spent a quiet night in their

positions. In fact, Freeman's men kept

their guns unloaded through the

night. The governor put it best:

"war over."67

Finley immediately began relieving units

on Tuesday. The first to

leave were those that had arrived first,

including the 4th and 14th

Regiments. As the soldiers left, the

civilians prepared to take over. The

mayor's committee began swearing in the

special police force to

augment the existing force.68

65. Finley to Hoadly, 3:00 a.m.,

telephone call, Hoadly to Hetrick, 5:00 a.m., Finley

to Hoadly, 5:05 a.m., telegrams, 31

March 1884, in George Hoadly Papers, 1847-1886,

MSS. 314, box 1, folder 3, March 1884,

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio,

hereafter cited as GHP; Hoadly to

Finley, 5:43, 31 March 1884, telegram, in AR 1884,

p. 191.

66. Norton to Hoadly, 1:54, Hetrick to

Hoadly, 8:30, Hoadly to Thorp, 10:45, 31

March 1884, telegrams, in AR 1884, pp.

190-91, 193, and reports of Col. Freeman, Col.

Picard, Col. Norton, Col. Pocock, and

Maj. Harper, pp. 234, 240, 243-44, 262, 265.

67. Hoadly to A. L. Conger, 11:51, 31

March 1884, telegram, in ibid., p. 194, and Gen

Order no. 6, 31 March 1884, pp. 209-10,

and reports of Col. Norton, Col. Entrekin, Lt.

Col. Shellenberger, Col. Pocock, Maj.

Harper, and Col Hetrick, pp. 244, 250, 256, 262,

265-66; News-Journal, 1 April

1884; Commercial-Gazette, 1 April 1884.

68. Finley to Hoadly, 4:20, 31 March

1884, telegram, in AR 1884, p. 196, and Spec.

Orders nos. 7-9, 1 April 1884, p. 212,

and report of Col. Freeman, p. 234; News-Journal,

1 April 1884.

48 OHIO HISTORY

Wednesday the demobilization continued,

though Hoadly and Finley

decided not to empty the city entirely.

Hawkins, Mayor Stephens, and

the mayor's committee of citizens all

requested that Hoadly leave a

regiment in the city a few days longer,

possibly until Tuesday, April 8,

the day after the spring elections.

Finley ordered one regiment to stay

until that Tuesday, and upon Hoadly's

advice, he ordered a second

regiment to remain until Thursday, April

3, just to be safe. In addition,

forty-one men of the 1st Regiment would

remain at the armory until

April 17.69

The rest of the soldiers left Wednesday,

as did Finley. Ryan stayed

throughout the whole period, supplying

coats, blankets, and food to the

soldiers. Finally, at 8:00 A.M. Tuesday,

April 8, the day after Cincinnati's

spring elections and eleven days after

the riot had begun, the last unit

of the ONG left Cincinnati.70 As

the soldiers left, the police replaced

them on the streets. They allowed no one

near the jail or Courthouse

without a pass until Thursday, when the

barricades came down. Main

Street finally reopened. Police,

however, continued to guard the

area.71

The best estimate of the total

casualties during the riot is forty-five

dead and at least 139 wounded. Guard

casualties were approximately

forty wounded and two dead. The

fatalities were Desmond on Saturday,

and Private Israel Getz, who apparently

died by accident Tuesday,

April 1.72 The number of militia

casualties indicates the ferocity and

deadly intent of the rioters, while the

deaths among non-soldiers shows

the Guard's willingness to defend

itself.

Troubles began over a sham verdict of

manslaughter. Two weeks

later almost 200 men were dead or

wounded and the Courthouse was

destroyed. What were the results of this

display of hostility? For

Cincinnati there seemed to be few.

Monday, April 7, the people voted

in an election that changed nothing. The

political machine still con-

trolled the election and the same

politicians won. McLean was not

ousted until the next year. One gain,

however, was that Tom Campbell

fled the city soon after the riot. Crime

continued to increase while the

69. Finley to Hoadly, 5:50, 1 April, and

11:44, 2 April 1884, telegrams, in AR 1884,

pp. 201, 205, and report of Col. Hunt,

p. 226; Urner to Hoadly, 2 April, Executive

Committee to Hoadly, 2 April 1884, GHP,

box 1, folder 4, April 1884.

70. Finley to Hoadly, 12:02, 2 April,

Ryan to Hoadly, 10:36 and 12:10, 3 April,

Church to Hoadly, 4:04, 8 April 1884,

telegrams, in AR 1884, pp. 205-07, and Spec.

Orders nos. 13-39, 1-2 April 1884 (for

details of the departures of the various units), pp.

213-220.

71. Enquirer, 2-4 April 1884.

72. Ibid., 6 April 1884; Commercial-Gazette,

2 April 1884; Gen. Order no. 8, 2 April

1884, in AR 1884, p. 210, and

reports of Col. Freeman, Lt. Shepherd, Surgeon Guerin,

and Surgeon Hough, pp. 234-36, 241.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 49

people's indifference grew. Capital

punishment, though, also increased.

New laws were passed regulating criminal

trials. Thus there was some

gain in the legal justice system which

had, after all, been the spark that

had started the explosion. Cincinnati,

however, was not free from

violence. Six months later, during the

fall elections, more riots erupted,

though that time the ONG did not have to

intervene.73 Cincinnati paid

a heavy price for these few gains.

The local authorities deserve some

mention. Hawkins did an excel-

lent job as commander of the military

until Finley arrived. Though in

command when the Courthouse burned, he

could not defend every-

thing with his weak force. He accepted

the personal thanks of the

governor and, in 1890, he received

further recognition when he became

the Adjutant General of the ONG. The

police also were faithful to their

duty, serving side by side with the

soldiers throughout the crisis. They

deserved the praise they received from

the newspapers and authori-

ties.74 The mayor's absence

during the first two days of rioting marred

his performance. On Sunday, however, he

began to reestablish civilian

control, rallying the citizens and

coordinating, through Finley, the use

of the militia and police. His actions

during those days deserve credit.

The experience in Cincinnati disturbed

the ONG. Hunt feared that

the hostility of the rioters would have

an adverse effect on the 1st

Regiment, and he was right. Hunt

resigned in June, and the Lieutenant

Colonel, Major, and Chaplain of the 1st

all resigned before the end of

the year. Joyce's battery suffered a

similar fate as its three ranking

officers all resigned by the end of

September. The 4th Regiment,

meanwhile, faced a Court of Inquiry,

which relieved Mott of command.

The Court ruled that the 4th had failed

to do its duty, and found Mott

guilty of incompetence and disobedience

of orders. Rather than face a

court-martial, Mott "Resigned for

the good of the service" in July. On

May 31, 1884, the headquarters of the

4th disbanded, as did three of its

companies. The other companies formed

the nucleus of a new regi-

ment.75

73. Wright, Bossism, p.

23;Tunison, Riot, pp. 72-74; Wittke, History of Ohio, V, 198;

History of Cincinnati, 1894, p. 371; Johnson,On the Roof, p. 94; Gary

P. Kocolowski,

"Expanding Police Services in

Late-Nineteenth-Century Cincinnati," The Cincinnati

Historical Society Bulletin, 31 (Summer 1973), 117.

74. Hawkins to Hoadly, 2 April 1884, in GHP,

box 1, folder 4; D. F. Pancoast, Adj.

Gen., Report of the Adjutant General

of Ohio to the Governor of the State of Ohio for

the Year 1946 (Columbus, 1947), p. 19.

75. Enquirer, 3 April 1884; Ohio,

Adjutant General, Ohio National Guard, Adminis-

tration, Commissioned Officers'

roster, by Company, 1875-1917, ser. 73, 1884, Ohio

Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio, pp.

433, 505-10, 736; Regimental Rosters, 1863,

1870-1904, ser. 162, 1st Regiment, 1884, Ohio Historical Society,

Columbus, Ohio; Court

of Inquiry, in AR 1884, pp.

297-302.

50 OHIO HISTORY

Other organizational matters also

received attention. In April,

Hoadly and Finley implemented Finley's

suggestion to brigade the

regiments to increase large-unit drills

and to help ease future mobili-

zations. Hoadly had Finley study the

advisability of attaching a Gatling

gun to each regiment. As Hoadly

explained, "Gatling-guns seem to

extinguish a mob quicker than any other

weapon."76 The crowd facing

the Court-Clay barricade Sunday night

probably would have agreed.

Overall, Finley and Hoadly planned to

gain from the experience in

Cincinnati.

The Cincinnati riot did, in the end,

provide testimony to the

efficiency and skill of the state

command system and the ONG. The

governor received many messages of

congratulations, including one

from Mayor Stephens' executive committee

which thanked Hoadly for

the prompt concentration of a force

large enough to stop the violence.

The Cleveland Leader wrote:

"This was the Governor's first experi-

ence in military affairs. He is cool in

all his movements, and is

undoubtedly competent for any

emergency." Hoadly coordinated the

movements of all the units, maintained

the logistical support, and kept

abreast of the situation in Cincinnati.

In short, he ably performed the

functions of a commander in chief. His

hesitation on Saturday delayed

the arrival of the Guard Saturday night,

which left the Courthouse open

to destruction. In light of Sunday's continued

violence, however, his

hesitation did not materially lengthen

the riot.77

The number of soldiers in Cincinnati did

not seem to impress the

rioters. They fought the police and a

few Guardsmen Friday night, they

battled over 500 Guardsmen Saturday, and

finally on Sunday they

fought over 1100 soldiers. With 2500

soldiers in Cincinnati on Monday,

the violence ceased. Hoadly, however,

was justifiably reluctant on

Saturday to send almost one-half the

entire ONG after one night's

rioting. He sent over 700 men on

Saturday, and without definite

knowledge that more were needed, Hoadly

could not justify a further

mobilization. When he received such

knowledge late Saturday night,

he immediately began a full

mobilization. His decision to commit the

ONG in stages was the best possible,

given the circumstances of the

moment.

The ONG in general earned the praise it

received. Finley cooperated

with the civil authorities, subordinated

the ONG to the mayor, and

several times Sunday coordinated the

movement of the military with

76. AR 1884, pp. 25-26, and

Hoadly to Finley, 10:00. 1 April 1884, telegram, p. 198.

77. Executive Committee to Hoadly, 2

April, Urner to Hoadly, 2[6] April 1884, in

GHP, box 1,

folder 4; Cleveland Leader, 31 March 1884, quoted in Roberts,

"George

Hoadly," p. 28.

The Cincinnati Riot of 1884 51

those of the police. His dispositions on

Sunday met all emergencies. As

of Monday he read the situation

correctly and pulled out quickly but

not prematurely. The governor's staff

also provided essential assis-

tance by sending information and

coordinating logistics in Cincinnati.

The soldiers themselves performed

admirably. They received praise

from Hoadly, the newspapers of

Cincinnati, and Finley, who wrote,

"Soldiers of the Regular Army could

not have done better." Called to

service unexpectedly, these men entered

a confused and dangerous

situation but stayed under control,

obeying orders and avoiding

unnecessary use of force. Finley summed

this restraint in his report:

"Repeated assaults by the mob were

repelled by the troops, with as

little injury as possible." Freeman