Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

DAVID A. NIEDRINGHAUS

Dress Rehearsal For World War I:

The Ohio National Guard

Mobilization of 1916

The Ohio National Guard, like the

National Guard of other states,

has a long history of service to its

citizens and to the United States. Its

heritage is rooted in the militia

system that has played such a vital role

in the nation's history. In times of

crisis-natural disasters, civil

disturbances, or wars and rebellions-it

has often been called upon to

serve until the crisis subsides and

either order or peace is restored.

However, the role of these local

organizations within the national

defense structure has gone through many

changes. Early militia units

provided local defense for the

community and belonged entirely to

state governments for use in civil or

military emergencies. States

seldom permitted their militia to serve

outside their own borders, and

the federal government had little

authority to compel them to do so. In

times of national crisis-the Civil War,

for instance-the federal

government relied on its regular

standing army and on newly-created

volunteer units that it used to bring

the Regular Army up to sufficient

strength. These volunteers normally

were untrained, and it took time to

train these units to where they could

fight effectively in wartime.1

In the ensuing years, Ohio's militia

and those of other states slowly

assumed a greater role in the national

defense. The Ohio militia evolved

into a part of the National Guard,

distinct from the old militia in that it

now had a clear dual responsibility to

both the state of Ohio and the

federal government. In state internal

matters, it still served the

Governor of Ohio in quelling civil

disturbances or providing assistance

to areas hit by natural disasters. Its

role in the nation's defense,

Captain David A. Niedringhaus recently

completed a three-year assignment as an

Assistant Professor of History at the

U.S. Military Academy, West Point. He received

his M.A. in history from The Ohio State

University in 1987 and is currently a student at

the U.S. Army Command and General Staff

College in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

1. Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski,

For the Common Defense: A Military

History of the United States of

America (New York, 1984), 165-67.

36 OHIO HISTORY

however, became that of a reserve force

that the President could call to

service when he needed additional

trained military forces beyond what

the Regular Army could provide.2

One of the key periods in the Ohio

National Guard's history

occurred during the Mexican border

crisis in 1916. National Guard

reform acts in 1903, 1908, and 1916 had

significantly altered the Ohio

National Guard's relationship with the

federal government. Those acts

increased federal funding to the

National Guard in return for a greater

commitment from the National Guard to

conform to War Department

directives. Officials hoped that the

improved mobilization system

would increase the ability of state

units to respond to federal calls for

troops. And for the first time, the

federal government now had the

authority to employ National Guard units

outside the United States

once they were "federalized,"

or inducted into federal service.3

The June 1916 mobilization was the first

test of the new system, and

it gave the Ohio National Guard an

opportunity to demonstrate how

well prepared it was to meet its new

responsibilities. This would prove

to be crucial, since the 1916

mobilization was only a portent of things

to come. A scant ten months later, in

April 1917, the Ohio National

Guard would receive yet another call to

mobilize, this time for

America's entry into World War I.

Setting the Stage for the 1916

Mobilization

In the summer of 1916, President Woodrow

Wilson faced a crisis

along the border between the United

States and Mexico. Growing

political turmoil in Mexico after a

revolution in 1910 made relations

between the two nations extremely tense.

Wilson's recognition of the

tenuous government of Venustiano

Carranza aggravated rival political

leaders. On March 9, 1916, tensions

reached a breaking point when one

of Carranza's rivals, Pancho Villa,

raided Columbus, New Mexico, in

retaliation for American support for

Carranza. Wilson responded to

this provocation by sending a force

under Brigadier General John J.

Pershing into Mexico to find and destroy

Villa's force and other bands

that appeared to threaten American

territory.4

On May 5, another raid occurred against

the Texas town of Glen

Springs. Four days later, Wilson

responded to a request by the U.S.

2. John K. Mahon, History of the

Militia and the National Guard (New York, 1983),

260-61.

3. Millett and Maslowski, Common

Defense, 312-13.

4. Thomas Paterson, American Foreign

Policy: A History (Lexington, Mass., 1983),

237.

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 37

Army Southern Department Commander,

Major General Frederick

Funston, by calling up militia units

from Texas, New Mexico, and

Arizona to protect the border against

further raids. Border skirmishes

continued nonetheless. By mid-June,

Wilson determined that Ameri-

can military strength on the border was

insufficient and needed

bolstering. On June 18, 1916, he ordered

the mobilization of the

Organized Militia and the National Guard

of the remaining states for

service along the Mexican border.5

For the Ohio National Guard, as for

Guard units in other states, the

1916 call-up was the first mobilization

for federal service since the war

with Spain in 1898. The 1898

mobilization of state militias had

demonstrated significant flaws in the

entire American system for

wartime mobilization at both the state

and federal levels. The militia

system officially had changed little

since the Uniform Militia Act of

1792; in fact, that act remained on the

books for 111 years, until 1903.

It required states to maintain a

militia, with every citizen in theory

subject to enrollment and possible

militia service. Officers assigned as

militia captains were required to enroll

every able-bodied white male

citizen "residing within the bounds

of this company," and every

citizen subsequently had to provide his

own firearms and equipment.6

Modifying acts in 1795, 1798, and 1808

provided for a small degree of

federal financial support. In return for

this aid, states incurred an

obligation to support Presidential calls

for state governors to provide

milita in case of invasion or rebellion.7

Through the remainder of the 19th

century, Congress tacked on

minor amendments to the 1792 act, but

the law and the system did not

change radically. In actual practice,

volunteer companies became the

mainstay of local military

organizations. These units often went their

own way in establishing uniform and

equipment requirements. Even

with some reforms in the 1880s and

1890s, few National Guard

companies conducted serious military

training. Enthusiasm was often

high in such units, but these

organizations seldom were anything more

than social clubs.8 As a

solid basis for a standardized, integrated

reserve force for national emergencies,

they were far from adequate.

During the 1898 mobilization, the

McKinley administration tried to

enlarge the Regular Army by asking for

individual volunteers from the

National Guard to fill existing units

for the duration of the war.

5. Clarence C. Clendenen, Blood On

the Border (London, 1969), 289.

6. Eldridge Colby, The National Guard

of the United States: A Half-Century of

Progress (Manhattan, Kansas, 1977), 9-12.

7. Ibid., 11-12.

8. Ibid., 23.

38 OHIO HISTORY

However, at the same time McKinley

called for 125,000 Guardsmen,

most of whom decided they would rather

serve with existing or newly

formed units from their local area

rather than with a Regular Army

unit. Potential volunteers often

preferred to join National Guard units

because they only had to serve for the

duration of the war rather than

for the fixed enlistment terms required

by the Regular Army. Only a

second call for further volunteers

finally filled the Regular Army's

authorized strength.

The War Department now had to support

and train the state

volunteer regiments that flooded into

large, hastily organized federal

camps. Unprepared for the huge numbers

of new soldiers, the War

Department initially proved incapable of

logistically and medically

supporting the volunteer units. Disease

and chaos reigned for several

weeks. War Department officials reacted

to this situation quickly, but

the memory of sick, bored, untrained and

ill-prepared soldiers lingered

on as a symbol of the army's ineptitude

in mobilizing for the war with

Spain.9

At the same time, the experience showed

the Guard's potential as a

structure for training and equipping men

before they might be called

into federal wartime service. The

National Guard was not yet part of a

truly workable and responsive reserve

system. By law the Guard was

still basically a state-funded militia,

as established in the 1792 Uniform

Militia Act that remained in force. In

1899, though, the newly appoint-

ed Secretary of War, Elihu Root, began

to initiate reforms that

profoundly affected the Guard's role in

the nation's defense.10

Several important changes took place in

the eighteen-year period

between the 1898 experience and Wilson's

National Guard call-up in

1916. In 1903, Congress passed the Dick

Act as a direct response to

some of the severe problems experienced

during the 1898 mobilization.

Among other things, this act created a

Division of Militia Affairs within

the War Department that managed militia

and National Guard matters.

Also, federal subsidies to the Guard

increased dramatically. By 1906,

the federal government provided

$2,000,000 per year to arm state

militias, up from the $400,000 annual

subsidy it had provided earlier. In

return for the huge increase in federal

dollars, the Regular Army gained

increased control of National Guard

training and organization.11

A follow-up act in 1908 continued the

reform movement by giving the

federal government more discretion in

employing the Guard outside the

United States and for greater lengths of

service. Some restrictions

9. Millett and Maslowski, Common Defense, 272-73.

10. Mahon, History of the Militia, 138.

11. Ibid., 139-40.

|

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 39 |

|

|

|

remained. The federal government had to keep the Guard intact in its original units rather than using it as a pool of individual replacements for Regular Army units. It also could keep the Guard units in its service only for the duration of the emergency.12 The Attorney General in 1912 declared parts of the 1908 act unconstitutional, questioning whether the federal government could employ the Guard outside the country after all. The 1916 National Defense Act confirmed Congress' intent to allow the Guard to serve outside the continental United States if necessary. It established a dual oath required for all Guardsmen that bound each man to serve the federal government once his unit was called into service.13 The changes initiated by the acts of 1903, 1908, and 1916 significantly increased the ability of the National Guard to equip itself and to mobilize quickly and efficiently for federal service.14 By 1916 the system appeared to be firmly in place and working smoothly. Ohio Guard units organized the same way Regular Army units did and made great strides in training during weekly drill periods and annual summer training encampments. When the mobilization call came in mid-1916, there seemed to be little reason to expect that the Ohio National Guard would have any significant problems.

12. Colby, National Guard, 33. 13. Ibid., 34. 14. Ibid., 34-36. |

40 OHIO HISTORY

Status of the Ohio National Guard in

1916

The Ohio National Guard in 1916

contained eight infantry regiments

and one separate infantry battalion, one

squadron of cavalry, one

battalion of field artillery, an

engineer battalion, a signal corps battal-

ion, and a medical department consisting

of three field hospitals and

two ambulance companies. It also had a

small contingent of officers

that served on the staff of the Adjutant

General, including the Inspector

General, the Judge Advocate General (for

legal affairs), the Quarter-

master detachment (for supply

administration), and the Ordnance

Department, which handled weapons and

ammunition matters.15 Three

of the infantry regiments-the Second,

the Third, and the Sixth-

belonged to the First Brigade, while

three more-the Fourth, the Fifth,

and the Eighth-belonged to the Second

Brigade. The First and

Seventh Infantry Regiments, along with

the Ninth Infantry Battalion

(black), remained unattached.16

The Ohio National Guard in 1916 centered

on local communities.

Company-sized units generally drew their

members from no more than

one or two counties, with the company

headquarters located in the

largest or most central small town in

the area. Regiments followed a

regional organization, with the larger

cities in Ohio serving as regimen-

tal headquarters. Thus, the First

Regiment, headquartered in Cincin-

nati, drew on the population of

southwest Ohio, the Fourth Regiment

(Columbus) consisted of companies in

central Ohio, and so forth. The

companies of the Fourth Regiment were

located in surrounding small

towns and county seats, including

London, Marion, Marysville, New-

ark, Delaware, Lancaster, and Washington

Court House. The remain-

ing regimental headquarters were located

in Lima, Dayton, Cleveland,

Toledo, Marietta, and Bucyrus, all among

the larger cities in Ohio in

1916.17 Most of these units maintained a

peacetime strength sufficient

to meet federal requirements and to deal

with internal state emergen-

cies such as natural disasters or civil

disturbances. In a mobilization for

federal service, however, units expanded

to a higher, wartime autho-

rized strength.18 Ohio

National Guard units relied on volunteers to fill

the difference between peacetime and

wartime strength levels in

existing units.

Despite the federal government's

involvement in directing what

kinds of units it wanted the Ohio Guard

to maintain, recruiting

15. "Report of the Chief of the

Militia Bureau," War Department, Annual Reports,

1916 (Washington, D.C., 1916), 1080-87.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid., 1132.

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 41

remained very much a local process. If a

man wished to join the

National Guard during a period of

wartime mobilization, signing up

with an existing unit in or near his own

area was usually his only

option. Occasionally, he had a choice of

what kind of unit he could

enlist in. A volunteer in the Columbus

area, for example, might join B

or I companies of the Fourth Infantry,

Company B of the Signal

Battalion, or Troop B of the First

Cavalry Squadron. 9 Competition for

recruits was often spirited in the

larger towns. Local pride in small-

town communities meant that most

volunteers from outlying areas

chose to enlist with the one infantry

company in their area. Black

citizens were restricted to the Ninth

Infantry Battalion, which had

companies in Springfield, Columbus,

Dayton, and Cleveland.20

By 1916, Ohio National Guard units

reflected much progress as a

result of the reforms of the 1903 Dick

Act, although many problems

remained. The law specified that

National Guard units be organized

according to the regulations which

governed like units in the Regular

Army.21 The Ohio National

Guard's regulations, most recently updated

in 1912, established training

guidelines, equipment allocations, officer

selection criteria, and standards of

performance for its units to ensure

that those units would meet federal

standards. Most Guard officers

made obvious efforts to attain and

maintain standards dictated by the

federal government, but standards among

Ohio Guard units still varied

widely.

Guard and federal officers enforced some

of the standards more

rigorously than others. Article XV of

the Ohio regulations, for exam-

ple, directed that each company would

assemble for drill and instruc-

tion at least once each week, a

directive that many units found difficult

to comply with.22 Many of

those that did muster at the required

intervals fell short of actually

conducting meaningful training at those

drill periods. Federal inspecting

officers noted this fact in their negative

evaluations of several Guard units that

had reported meeting fifty times

each year. Often, the degree of interest

that a Guard unit showed in

complying with training regulations was

proportional to the level of

interest shown by the federal

government. Ohio Guard units complied

better with another regulation that

directed them to conduct an annual

19. Adjutant General, State of Ohio,

General Order 27 (1915), November 14, 1915.

Ohio Historical Society, State Archive

Series 30.

20. Ibid.

21. "Report of the Chief of the

Militia Bureau," War Department, Annual Reports,

1917 (Washington, D.C., 1917), 864.

22. Adjutant General, State of Ohio, Regulations

for the Ohio National Guard, 1912,

(Columbus, 1912) 99-100.

42 OHIO HISTORY

encampment for a period of eight to

fourteen days each year between

the 1st of May and the 1st of November.23

Most Ohio Guard units conducted their

annual encampment at Camp

Perry, the major Ohio Guard training

facility along Lake Erie in

northern Ohio. One reason for strict

compliance with this regulation

was that it was the primary means for

federal inspecting officers to

monitor the Ohio National Guard's

ability to meet federal standards.

Federal officers used the annual

training encampments to evaluate,

over a period of several weeks or

months, the training and performance

of virtually every unit within the Ohio

Guard as it rotated through. The

stakes were high, since the results of

these inspections directly affected

the funding Ohio could expect to get

from the federal government.24

The reports from federal officers went

to the Militia Bureau, which

published the overall results annually

in its report to the U.S. Army

Chief of Staff. Each company's results

appeared in the report; com-

panies could be rated satisfactory, they

could be placed on probation,

or, in the worst case, they might have

their federal recognition

withdrawn. To the War Department,

unrecognized units were merely

state militia, meaning that those units

were not entitled to receive

federal funds.25 The 1916

Militia Bureau report on the Ohio National

Guard showed thirteen infantry companies

placed on probation and

eleven having their federal recognition withdrawn.26

Between one-

fourth and one-third of Ohio National

Guard infantry companies

therefore were in serious trouble. The

usual reasons for such sanctions

were insufficient strength or

chronically low turnouts for instruction

and drill periods. While some units

struggled to meet minimum federal

proficiency expectations, others

achieved outstanding results consis-

tently, both in turnout and in training

results. Standards for uniformly

evaluating Guard units were firmly in

place in 1916, but the ability of

individual units to meet those standards

still varied considerably.

Along with statewide training standards,

the Ohio Guard had the

responsibility to equip its soldiers to

the same standards as Regular

Army soldiers. This was a big step

forward from 1898, when Guard

soldiers had to wait for long periods of

time to receive weapons that

were generally old and outdated.

However, most Ohio Guard units had

only enough equipment available to equip

their peacetime strength.27

During mobilization for federal service

and expansion to war strength,

23. Ibid.

24. War Department, Annual Reports, 1917,

864.

25. Ibid.

26. War Department, Annual Reports, 1916,

1080-87.

27. Ibid., 895-99.

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 43

Guard units had to rely on the federal

government to provide the

weapons for any volunteers used to fill

the existing units.

The procedure for mobilizing Guard units

and inducting them into

federal service was straightforward. The

Ohio Guard regulations

required local company-sized units to

muster those soldiers already

assigned to them, conduct inventories of

property, and ensure that

their soldiers were physically and

medically fit for federal service.28 At

the same time, they began recruiting to

fill the gap between existing

strength and full authorized wartime

strength. Most units could expect

to accomplish this within two or three

days. At this point, unit

commanders and regimental quartermaster

officers arranged for trans-

portation to a state mobilization site.

The usual method, and most

convenient one, was to move troops by

rail.29

At the state mobilization site, federal

officers screened Guard

soldiers for medical and physical

fitness for federal service. Mean-

while, Guard units conducted training in

preparation for their antici-

pated duties. After a federal mustering

officer inducted the Guard into

the national service, Guard units fell

under the full control of the

federal government and the War

Department. The War Department

was responsible for moving the newly

inducted soldiers to federal

mobilization sites.30 In a broad sense,

the Ohio National Guard

mobilization of 1916 followed this process,

although numerous units

failed to comply fully with federal

directives and those of the Adjutant

General's office. This led to some

interesting results as the Ohio Guard

began to mobilize as quickly as possible

for federal service.

The Ohio National Guard Mobilizes

When President Wilson and Secretary of

War Newton D. Baker

issued their call for National Guard

units on June 18, 1916, Benson W.

Hough was Ohio's Adjutant General. In

1892, at the age of seventeen,

Hough had enlisted in the National Guard

and served during numerous

strike-breaking and natural disaster

relief assignments through 1897.

He was a student at Ohio State

University in 1898 and missed serving

in the war with Spain. After graduating

in 1899, he opened a law firm

in Delaware, Ohio, and soon established

a successful practice there. In

28. Regulations for the Ohio National Guard, 1912, 86-87.

29. Adjutant General, State of Ohio, Annual

Report of the Adjutant General, 1913,

292-93.

30. Cole C. Kingseed. "A Test of

Readiness: The Ohio National Guard and the

Mexican Border Mobilization,

1916-1917" (M.A. thesis, Ohio State University, 1980),

22.

44 OHIO HISTORY

1902, he received an officer's

commission in the Ohio Guard and soon

rose to command Company K of the Fourth

Ohio Infantry Regiment at

Delaware. In 1905, he was promoted to

major, and shortly thereafter he

was promoted to lieutenant colonel. By

1909, at the relatively young

age of 34, he commanded the Fourth Ohio.31

In 1915, Governor Frank Willis appointed

Hough to be the Adjutant

General of Ohio. Interestingly (and

perhaps not coincidentally), Willis

and Hough both were from Delaware

(Ohio).32 Hough served as

Adjutant General only briefly, resigning

his position almost immedi-

ately after the mobilization call so he

could reenlist as a private in his

old regiment, the Fourth Ohio. On July 8

he accepted his old

commission as the lieutenant colonel of

the regiment. He did, however,

stay on as the acting Adjutant General

through the mobilization period,

until September 6. By this time the Ohio

Guard had moved to the

Mexican border, and Hough had completed

his primary task as

Adjutant General. His Assistant Adjutant

General, Colonel Edward

Bryant, then replaced him.33 Hough

went on to compile a distinguished

record during World War I as the

commander of the Fourth Ohio,

which was redesignated the 166th

Infantry Regiment and fought as part

of the famous 42nd (Rainbow) Division in

northeastern France.34

Unlike the 1898 call-up, Secretary of

War Baker's mobilization

telegram to Governor Willis specified

precisely which units the federal

government wanted for service on the

Mexican border.35 This was

important, since it left no doubt that

this mobilization would rely

entirely on existing units as bases for

the recruitment of volunteers.

Baker's directive called the Ohio

Guard's two infantry brigades into

service, along with Ohio's one squadron

of cavalry, its battalion of field

artillery, its signal battalion, and its

ambulance companies and field

hospital units.36 The Second

and Seventh Infantry Regiments and the

Ninth Separate Infantry Battalion were

not called up for federal service

and went on to conduct their scheduled

summer training in 1916. The

Ninth Infantry Battalion, however,

played an important role in con-

structing the mobilization site during

the latter part of June.

After receiving the mobilization

instructions on the afternoon of June

18, Hough and his small staff

immediately went to work preparing and

31. Robert Cheseldine, Ohio in the

Rainbow (Columbus, 1924), 26-27.

32. Frank B. Willis Pamphlets, Ohio

Historical society, Box 276; and Cheseldine,

Ohio in the Rainbow, 26.

33. Adjutant General, State of Ohio,

Special Order 226, September 6, 1916.

34. Cheseldine, Ohio in the Rainbow, 36-109.

35. Ohio General Statistics

(Springfield, Ohio, 1916), 249.

36. Ibid.

|

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 45 |

|

|

|

issuing the necessary orders to mobilize the selected Ohio Guard units. At 4:00 A.M. on the 19th, the Governor's office released to the press the Adjutant General's General Order Number 12 of 1916, outlining initial instructions to the Ohio Guard for mobilization. In addition to detailing the units that had been called for federal service, Hough's order charged regimental and battalion commanders with the responsibility for feeding their enlisted men once they mustered. In addition, the order authorized a subsistence allowance of 75 cents per day for each man actually present. Commanders also had to provide bedding for their soldiers (most units used local armories when available) and forage and shoes for their horses. If suitable facilities for bunking soldiers were not available, commanders had the authority to allow enlisted men to sleep at home.37 General Order Number 12 devoted considerable attention to medical concerns. The directive admonished commanders to examine carefully

37. Frank B. Willis Papers, Ohio Historical Society, State Archive Series 325.5.17. |

46 OHIO HISTORY

their soldiers to detect any sign of

contagious diseases, especially

typhoid fever, measles, and mumps. The

order specified that if an

office of the Ohio National Guard

Medical Corps was unable to

conduct such inspections, commanders

were to have local health

officials and physicians make the

inspections. The order bluntly stated

that "no infected soldier will be

brought to the mobilization camp."

Equally important, the order directed

that "no recruit will be accepted

until he has been given a thorough

physical examination by a Medical

Officer and has been found to conform to

the physical standard

prescribed for the Regular Army."38

Hough's orders appeared clear

enough, but the Ohio Guard would run

into significant problems as a

result of inadequate compliance with

this directive.

Each regimental or separate battalion

commander assigned one

officer to be accountable for medical

property, another officer to

account for quartermaster property, and

a special accountability

officer who was responsible for any

ordnance, engineer, or signal

equipment within the command. In his

order, Hough reminded ac-

countable officers and local commanders

of the requirement during

mobilizations to inventory and inspect

all property belonging to the

state or the federal government which

the Ohio National Guard would

take into federal service. In addition,

the order directed that as soon as

a unit had been raised "to the

maximum practicable [strength] at its

home station," had at least reached

its prescribed peace minimum

strength, had conducted its property

inventories, and had made

suitable arrangements for "caring

for the armory and property to be

left behind," it should notify the

Adjutant General's office and await

further instructions.39

For most units, the "maximum

practicable" strength level was full

wartime strength, and the Ohio Guard

units selected for service on the

Mexican border sought to fill their

rolls to meet that level. The

peacetime strength of the mobilizing

Ohio Guard units was 7,295, little

more than half of the desired wartime

level of 13,541.40 Recruitment

began almost immediately throughout the

state, beginning from the

Governor's office. Willis' next press

release after the mobilization

order was a call to arms that appealed

to Ohio patriotism. He urged

Ohioans to enlist immediately "to

fill up every Ohio organization to its

war strength." Willis then released

a series of press statements

designed to stir up support for the

Mexican venture.41 His office

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid.

40. War Department, Annual Reports, 1916,

1132.

41. Ohio State Journal, June 20,

1916.

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 47

printed letters from eight-year old boys

and seventy-six-year old men

volunteering for service. One old man

who claimed to have lived in

Mexico for thirty-five years urged

people to volunteer in order to "go

into Mexico and clean it up once and for

all," the implication being that

since he had lived in Mexico he knew the

importance of sending

American units down to fight in Mexico.

On June 26, Willis released for

the newspapers another letter from a

large group of Civil War veterans

that volunteered for service despite the

fact that "some of [us]

physically are a little shaky."42

While the appeals for volunteers based

on patriotism were nothing

new, the 1916 mobilization was different

from past efforts in one

important respect. When an interested

citizen and ex-officer of the

Austro-Hungarian army named M. Wall

wrote to the Governor re-

questing the authority to organized a

company of fellow Austro-

Hungarians, Willis politely acknowledge

receipt of the request and

referred the matter to General Hough. He

also advised Mr. Wall that if

he really wanted to serve his adopted

country, he ought to consider

instead enlisting in an existing unit.43

Clearly, volunteer units formed

by ambitious citizens desiring quick

commissions and immediate high

rank were a thing of the past by 1916.

Governor Willis was not the only one who

used the newspapers to

attract volunteers to fill existing

units. Local newspapers were perhaps

the primary recruiting tools for the

company commanders and their

recruiting officers to enlist new

members into their units. These papers

often were even more open and

enthusiastic than the Governor had

been about using patriotic ideals to

stir up enthusiasm and encourage

the young men in their towns to join the

local military unit. The June

29th Kenton Graphic News Republican (home

of I Company, 2nd Ohio

Infantry) had a headline proclaiming,

"Men, show your patriotism

now!" Other towns across Ohio had

newspapers that offered similar

sentiments.44

Ohio National Guard recruiting officers,

of course, encouraged and

supported this form of advertising. They

also worked with local mayors

and officials (more often than not they

might be personal friends or

acquaintances) to gain further help in

making Guard services appealing

to the local citizenry. Many communities

responded by organizing

social affairs and meetings to support

their local Guardsmen and to

influence others to join the Guard.

Recruiting officers also pointed out

42. Willis Papers, Series 325.5.17.

43. Ibid.

44. Kingseed, "A Test of

Readiness," 15.

48 OHIO HISTORY

the financial benefits of serving in the

Guard during federal service.

Second lieutenants earned $4.72 per day,

sergeants $1 a day, and

privates $.60 a day plus meals after

being mustered in, amounts that

were not insignificant in 1916.45

It is important to note that while many

Guard members looked

forward to federal service and to

deploying to the Mexican border,

others were far less enthusiastic. Every

regiment designated for

movement to the border had a few

officers who resigned their

commissions to avoid service or who

submitted resignations prior to

the order to mobilize. The reasons for

avoiding service varied. Some

apparently found Guard service

inconvenient for their personal busi-

ness interests, while others felt

distaste at having to serve so far away

in the hot climate of Texas, New Mexico,

and Mexico itself. It is

unclear as to what, if any, penalties

this small minority of Guardsmen

may have received; probably few

regiments wanted to retain such

unenthusiastic leaders by forcing them

to stay on. As a result, the

Special Orders that the Adjutant

General's office issued regularly were

full of names of new officers elected by

their units to fill the vacancies,

and listed the results of state review

boards that determined whether

they were suitable for commissioning.46

Equipment shortages also plagued the

Ohio National Guard mobili-

zation. The Chief of the Militia

Bureau's report to the Secretary of War

for 1916 noted that, as of June 18, the

Ohio National Guard was short

large quantities of field equipment in

numerous categories and thus

could not completely equip its minimum

authorized strength for

wartime service. The Ohio Guard was also

short some weapons,

including thirty-two pistols and 268

pistol magazines. Unlike several

other states, Ohio was not short of

rifles, a significant change from

1898.47

The blame for equipment shortages also

belonged to the War

Department, which had the responsibility

to provide the weapons,

equipment, and supplies to make up the

difference between normal

National Guard strength levels and the wartime level that the federal

government required. The War Department

too had difficulty in

adequately fulfilling its requirements

to arm and equip those soldiers

that the Ohio National Guard could not

equip. The major problem

appeared to be that one depot stored the

reserve equipment and

supplies for all of the National Guard

units in the country.48 The War

45. Ibid., 20.

46. Adjutant General, State of Ohio,

Special Orders (1916), State Archive Series 117.

47. War Department, Annual Reports, 1916,

1151.

48. Kingseed, "A Test of

Readiness," 11.

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 49

Department was unable to appropriate

enough transportation to pro-

vide every state's Guard units with the

equipment that they needed. As

a result, most of the Ohio National

Guard's units were unable to fully

equip all of their soldiers until well

after they had been mustered into

federal service. Since the Ohio units

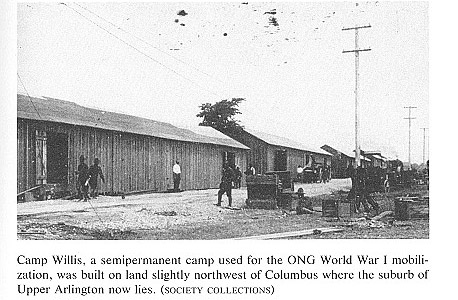

remained in Ohio at Camp Willis

(the mobilization site) for several

weeks after the muster, most did

manage to acquire the needed equipment

by the time they moved to the

federal mobilization site in late August

and early September of 1916.

The Camp Willis Mobilization Site

U.S. Army regulations of 1912 required

Division (or Department)

commanders having jurisdiction over

National Guard units to ensure

that mobilization camps within their

divisions were suitable. The

regulations also charged them with the

responsibility to correct any

deficiencies. The division commander

could direct state authorities to

prepare an adequate mobilization site.49

In Ohio's case, neither the

state administration nor the U.S. Army's

Central Department complied

with their responsibilities in

identifying and preparing such a site.

When the call to mobilize came on June

18, Ohio was almost

completely unprepared.

For the 1898 mobilization, Ohio National

Guard units had mobilized

near the Columbus suburb of Bexley.

After that mobilization, com-

plaints by citizens of that city ensured

that the site could not be used

for future mobilizations. In 1911, state

and federal officials selected

Camp Perry as a prospective mobilization

site.50 Camp Perry had

numerous drawbacks for that purpose,

however, along with its obvious

benefits. Located along Lake Erie in

northern Ohio, Camp Perry was

a long way from many Ohio National Guard

units, particularly the First

Ohio Infantry Regiment at Cincinnati and

the Seventh Ohio Regiment

at Marietta. Furthermore, though it had

good training facilities, Camp

Perry was not particularly suited for

handling huge numbers of

soldiers. Normally, one or two regiments

at the most trained there at

any one time.51 While the rail and

transportation network near Camp

Perry was capable or receiving and

supporting one or two regiments, it

was inadequate for handling the demands

that moving the entire Ohio

National Guard would place on it.

In 1914, Adjutant General George H. Wood

appointed a board of

officers to review the suitability of

Camp Perry as a mobilization site.

49. Adjutant General, State of Ohio, Annual

Report, 1913, 200.

50. Kingseed, "A Test of

Readiness," 11.

51. Ibid.

50 OHIO HISTORY

This board determined that Camp Perry

was not a good place to have

a mobilization camp, and it submitted a

recommendation to move the

site to a place near Columbus. Columbus

had enough land for a camp

and drill field, particularly in the

northwest which was still mainly

farmland. The area had good drainage,

and the transportation system

around Columbus could easily handle the

demands of moving a large

number of men into the area. Finally, it

was easily accessible from all

parts of the state because it was a

railroad hub and was centrally

located. The U.S. Army

Inspector-Instructor for Ohio, Major George

C. Saffarrans, apparently forwarded the

recommendations and the

reasons behind them to the Central

Department in May 1914.52

Unfortunately, nothing more seems to

have happened between May

1914 and June 1916 to prepare a site

that could receive and support the

Ohio National Guard. Thus, Ohio Guard

officials in 1916 were caught

completely off guard by not having made

critical decisions and

preparations for a mobilization site

before the urgent need for one

arose.

The failure by state and federal

officials to establish or prepare a

suitable site meant that Adjutant

General Hough had to make some

immediate and difficult decisions after

the mobilization order. The site

that Adjutant General Hough picked for

the Ohio National Guard's

mobilization in 1916 was slightly northwest

of Columbus, where the

suburb of Upper Arlington now lies. Two

Columbus real estate

developers-King Thompson and his brother

Ben-had recently bought

most of the sprawling Henry Miller farm

there (in the area between the

current Fifth and Lane avenues in Upper

Arlington). By 1916 they had

just begun to build homes on that land,

with twelve families living in the

new development. At this point, the area

was still unincorporated and

lacked a full system of drainage

culverts and sewer lines.53

Because of the lack of necessary support

facilities, Hough elected to

establish a semipermanent camp that

could house and support a large

number of troops for an extended period.

The influx of National

Guardsmen became a temporary

inconvenience for the residents, but

proved beneficial to the Thompson

brothers because of the additional

roads, sewers, culverts, and gas and

water lines that the Ohio Guard

emplaced and then abandoned when it

moved down to Texas. The

issue of who should fund the project was

not fully clarified. State

officials spent over $200,000 to build

the camp, believing that the

federal government would pay for the

cost of the Camp Willis

52. Ibid., 12.

53. Marjorie Sayers, ed., History of

Upper Arlington, (Columbus, 1977), 13.

|

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 51 |

|

construction. The War Department, however, considered the camp far too elaborate for what is suspected would be a one-term mobilization site. It flatly refused to pay the full cost. Ultimately the state and the federal government shared the cost.54 The Thompson brothers, of course, were the big winners in the whole affair. The delays in constructing the camp and the facilities to support thousands of men would have a significant effect on Ohio's mobiliza- tion schedule. The delay caused Ohio to lag well behind other states in mustering its soldiers into federal service and deploying them to the border. Given the War Department's desire to get units to the border as soon as possible and the resulting urgency to mobilize quickly, Hough's decision earned him some criticism later from the Central Department commander for creating a long delay in assembling the Ohio National Guard. Hough named the site Camp Willis after the Governor, and initiated the construction he believed necessary to provide a livable and sanitary mobilization site. He directed his Chief Quartermaster, Colonel William H. Duffy, to stake out the camp, supervise the construction of latrines, roads, drainage systems, and water supply systems, arrange for garbage disposal, purchase forage, rations, and fuel, and to complete a

54. Kingseed, "A Test of Readiness," 10. |

52 OHIO HISTORY

host of other requirements. On the same

day, June 19, he notified the

mobilizing units that he expected to be

able to receive troops by the

23rd of June. Hough issued orders to

several other officers to assist

Duffy, and he detailed the Ninth

Infantry Battalion to provide the men

to do the actual construction. Colonel

Duffy also hired local workers

and used prisoners from the state

penitentiary in Columbus to speed up

the process. Camp Willis was completed

on June 27, nine days after the

initial mobilization notice.55 Colonel

Duffy and the men who worked

for him did a remarkable job in

constructing the camp so quickly, but

it was not fast enough to avoid a

lengthy delay in mobilizing the Ohio

Guard.

The construction of Camp Willis was the

major reason behind the

Ohio National Guard's failure to

mobilize as quickly as the War

Department expected. The Central

Department Commander's report

to the U.S. Army Adjutant General

severely criticized Hough for

selecting "an absolutely

unsuitable" site and for constructing facilities

"of no permanent value." The

report went on to state that federal

officials had tried to speed up the Ohio

Guard's mobilization, but

concluded that "it was impossible

to get state authorities to hasten

assembly."56 The

criticism was not entirely fair, since the Central

Department shared part of the blame for

not fulfilling its responsibili-

ties in monitoring state mobilization

sites as directed by the U.S.

Army's regulations.

Nevertheless, of the fourteen states

under the Central Department's

jurisdiction, Ohio was the last to

assemble. The states closest to Ohio

in tardiness-Iowa, Minnesota, and South

Dakota-assembled a full

four days earlier than Ohio, while

Missouri and Wisconsin had done so

nine days before Ohio finally completed

its assembly on July 2.57 Even

after the Ohio Guard began assembling

at Camp Willis, however,

further delays unfolded.

Mustering the Ohio National Guard

Into Federal Service

Once Guardsmen arrived at Camp Willis,

two other actions had to

occur before federal officials mustered

them in. The first was a medical

screening and physical examination,

while the other was the adminis-

tering of a dual oath of allegiance and

service which Congress had just

passed into law on June 3, 1916. The

mustering officer in charge of

supervising these tasks was U.S. Army

Major Robert W. Mearns.58

55. Columbus Evening Dispatch, June

28, 1916.

56. "Militia Bureau Report,"

1916, as cited in Kingseed, "A Test of Readiness," 26.

57. Ibid., 27.

58. Central Department, United States

Army, Special Order 50 (1916), June 20, 1916,

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 53

Ohio National Guard units generally did

not comply with Hough's

directive to conduct thorough physical

and medical screenings of their

soldiers and new recruits. Federal

medical screeners found that local

commanders allowed many Guardsmen to

enlist without physical

examinations, and that others had

enlisted even after local medical

examiners identified disqualifying

characteristics. The Ohio National

Guard's Surgeon General, Colonel Joseph

Hall, and his state medical

examiners embarrassed themselves by

clearing for service many

Guardsmen that federal examiners

rejected later. The final results of

the federal screenings showed that over

25 percent of the Ohio

Guardsmen were rejected for medical and

physical deficiencies, includ-

ing over 400 in the Eighth Regiment

alone.59 This too was the worst

showing within the Central Department,

where the average rejection

rate was still a disturbing 15.5

percent.60 Although it is possible that

Major Mearns imposed standards that may

have been higher than those

of mustering officers in other states,

it was nevertheless apparent that

Ohio's medical and physical screening

procedures were fundamentally

flawed.

The attrition of Guardsmen rejected for

medical reasons ensured that

when the Ohio National Guard did finally

muster into federal service,

it was far short of the wartime strength

level that state and federal

officials had expected. The huge number

of medical rejections sparked

a public outcry and grumblings from

those units that were hit the

hardest. Mearns' attitude, as he later

explained, was that he "would

rather take to the border 65 good, fit,

and able-bodied men than 100,

part of whom couldn't stand the

pace."61 The rigorous standards used

to evaluate the Ohio Guardsmen (and

those of other states as well)

clearly indicated that when the federal

government mobilized the

National Guard, it now expected the

states to provide first-rate soldiers

from the start.

A final delay in mustering occurred due

to confusion by many Guard

members over a dual oath that each had

to take before entering federal

service. The National Defense Act of

1916 established the requirement

that Guardsmen had to take a new oath of

allegiance to the United

States upon enlistment. Under the old

law, Guardsmen would take an

oath each time they mustered for federal

service, but that oath was

only in force for the duration of that

specific period of service. Once a

as cited in Kingseed, 32.

59. "Report of the Mustering in of

the National Guard in the Central Division," NG

File 370.01, National Archives of the

United States, as cited in Kingseed, 33.

60. Ibid.

61. Ohio State Journal, July 6,

1916.

54 OHIO HISTORY

Guardsman reverted back to state

control, his allegiance reverted back

to the state as well. Congress' intent

with the dual oath of 1916 was to

make it unnecessary to administer a new

oath of allegiance to Guard

members every time they mustered into

federal service. Also, under

the new act the federal government no

longer needed to be concerned

about a specific limit to the time a

Guardsman could stay in federal

service. 62

Unfortunately, many Ohio Guardsmen did

not fully understand the

law or the dual oath's purpose. Many

understood the "permanent

allegiance" aspect of the law to

mean that they would be permanently

obligated to serve in the Regular Army.

Actually, the oath only applied

to the remainder of their enlistment

term. Eventually, commanders

convinced reluctant soldiers that the

dual oath was not an indefinite

commitment to the U.S. Army, and the

oath controversy subsided. On

July 15, 1916, Mearns finally completed

the federalization of the Ohio

National Guard, four weeks after the

initial notification.63

Conclusion

The Ohio National Guard's 1916

mobilization and induction into

federal service saw some encouraging

successes and some even more

noticeable failures. The major

disappointment during the mobilization

was the embarrassing series of delays

that plagued the Ohio Guard

during the month it took to complete the

process of federalization. The

first serious delay arose from state and

federal officials' failures to

prepare a mobilization site. Federal

regulations clearly indicated the

importance of taking these actions, but

officials at all levels had done

little before President Wilson rather

suddenly issued his call to

federalize the National Guard.64 The

lack of a suitable mobilization

site, coupled with General Hough's

decision to begin construction at

Camp Willis after the notification

alert, delayed Ohio's mobilization by

about nine days.65 Another

embarrassment to the Ohio National Guard

occurred after units arrived at Camp

Willis and underwent medical

screening from federal mustering

officers. Federal and state guidelines

again clearly outlined the necessary

procedures and standards for

establishing physical fitness for

federal wartime service. General

Hough reiterated the major requirements

in his initial General Order

62. Millett and Maslowski, Common

Defense, 324-25.

63. Ohio State Journal, July 16,

1916.

64. Kingseed, 34-36.

65. Ibid., 26.

Dress Rehearsal For World War I 55

for mobilization.66 Local

commanders and recruiting officers and state

medical officers generally failed to

comply with those directives, or

failed to achieve the required

standards. As a result, federal screening

officers rejected over a quarter of the

Guardsmen that came to Camp

Willis.67

Problems in the federal supply system

and equipment shortages

caused other minor delays. In the

mobilization camp, another small

delay arose due to confusion among

Guardsmen as to what the dual

oath of allegiance actually meant. As a

result, they were reluctant to

take the oath until they were completely

satisfied that they were not

being tricked into joining the U.S.

Regular Army permanently.68

The procedures for mobilizing were far

better and clearer than they

had been in 1898. Yet, the Ohio

mobilization in 1916 certainly did not

go as smoothly or successfully as state

or federal officials had expected

or desired. The Ohio National Guard did

mobilize, but it did so behind

schedule and below minimum federal

standards. The reason for the

relatively poor performance was not that

the system was inherently

faulty, but because problems arose from

poor planning (no planned

mobilization site) or sloppily executed

directives (poor medical and

physical screening of prospective

Guardsmen). Perhaps the most

damning indictment of the Ohio Guard's

performance during the

mobilization and mustering stages was

that Ohio was the last state in

the entire Midwest Region (Central

Department) to mobilize and had

the highest percentage of Guardsmen

rejected as being physically unfit

for federal service.69 Other

states mobilized, mustered, and deployed

several weeks before the Ohio Guard was

able to do so.

Encouragingly, many of the problems that

plagued the 1916 mobili-

zation were solvable in time for the

next mobilization. The Ohio

National Guard now had a mobilization

site, and should Camp Willis

become unavailable in the future, Ohio

Guard officers now had a

clearer idea of the importance of

finding and building a new one

quickly. Having experienced the federal

medical screening process, the

Ohio National Guard's medical officers

could adjust their procedures

and standards accordingly.

Despite the setbacks, the 1916

mobilization had some successes as

well. Many communities showed great

support for their local Guard

units, which enhanced the mobilization

process. Hough's construction

66. Willis Papers, Series 325.5.17.

67. Kingseed, 33.

68. Ohio State Journal, July 16,

1916.

69. "Report of the Mustering in of

the National Guard of the Central Division," NG

File 370.01, National Archives of the

United States, as cited in Kingseed, 33.

56 OHIO HISTORY

of Camp Willis may have delayed the

mobilization, but it also ensured

that once the Guardsmen did arrive there

would be adequate facilities

to support them. Unlike 1898, the Ohio

Guard in 1916 had no serious

problems with disease. More importantly,

once Ohio units did get to

the Mexican border, most performed very

well.70 These factors erased

much of the bad taste from the

frustrating delays experienced during

the mobilization period. With these

encouraging successes comple-

menting the lessons learned from the

failures, the 1916 mobilization, in

the final analysis, proved to be a

valuable trial run for the bigger

mobilization that occurred less than a

year later when the United States

entered the First World War.

70. Kingseed, 79-80.

DAVID A. NIEDRINGHAUS

Dress Rehearsal For World War I:

The Ohio National Guard

Mobilization of 1916

The Ohio National Guard, like the

National Guard of other states,

has a long history of service to its

citizens and to the United States. Its

heritage is rooted in the militia

system that has played such a vital role

in the nation's history. In times of

crisis-natural disasters, civil

disturbances, or wars and rebellions-it

has often been called upon to

serve until the crisis subsides and

either order or peace is restored.

However, the role of these local

organizations within the national

defense structure has gone through many

changes. Early militia units

provided local defense for the

community and belonged entirely to

state governments for use in civil or

military emergencies. States

seldom permitted their militia to serve

outside their own borders, and

the federal government had little

authority to compel them to do so. In

times of national crisis-the Civil War,

for instance-the federal

government relied on its regular

standing army and on newly-created

volunteer units that it used to bring

the Regular Army up to sufficient

strength. These volunteers normally

were untrained, and it took time to

train these units to where they could

fight effectively in wartime.1

In the ensuing years, Ohio's militia

and those of other states slowly

assumed a greater role in the national

defense. The Ohio militia evolved

into a part of the National Guard,

distinct from the old militia in that it

now had a clear dual responsibility to

both the state of Ohio and the

federal government. In state internal

matters, it still served the

Governor of Ohio in quelling civil

disturbances or providing assistance

to areas hit by natural disasters. Its

role in the nation's defense,

Captain David A. Niedringhaus recently

completed a three-year assignment as an

Assistant Professor of History at the

U.S. Military Academy, West Point. He received

his M.A. in history from The Ohio State

University in 1987 and is currently a student at

the U.S. Army Command and General Staff

College in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

1. Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski,

For the Common Defense: A Military

History of the United States of

America (New York, 1984), 165-67.

(614) 297-2300