Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

H. ROGER GRANT

Erie Lackawanna: An Ohio Railroad

The Erie Railroad possessed a strange

past. In the nineteenth century it

could claim to be an unusual road. For

one thing, it was America's first

long-distance trunk line. Under the

corporate banner of the New York

& Erie Railway, the company in April

1851 completed a 483-mile route

"Between the Ocean and Lakes,"

linking the New York communities of

Piermont on the Hudson River with

Dunkirk on Lake Erie. The railroad

also extolled its distinctive broad or

"Erie Gauge," the impressive six feet

between its iron rails rather than what

emerged as the standard width of

four feet eight and one-half inches.

(Later the company advertised ex-

tensively that because of its uncommon

construction, "[It] ... is select-

ed over and over again for handling

oversize shipments because it is fa-

mous for the highest and widest

clearances of any eastern railroad.")1

But there was a dark side to Erie. Its

building process took nearly a gen-

eration, in part because self-serving

politicians forced it to push through

New York's rugged and sparsely settled

"Southern Tier" of counties. As

a result the road missed direct ties to

the burgeoning cities of New York

and Buffalo and skirted the traffic

centers of northeastern Pennsylvania,

thus weakening its earnings

capabilities. The property was hardly a mod-

el for emulation. In the 1850s it was in

such wretched shape that Edward

Harold Mott, the Erie's first chronicler,

observed that it "became notori-

ous for the insecurity of travel upon

it." When reorganized and revitalized

during the Civil War, the Erie Railway

soon became the "Scarlet Woman

of Wall Street." The unscrupulous

speculator, Daniel Drew, discovered

the company and manipulated its stock.

Then, in 1867, a three-way bat-

tle erupted for control, with interests

represented by the wily Drew; John

Eldridge of the Boston, Hartford &

Erie; and "Commodore" Cornelius

Vanderbilt of the New York Central. Two

other financiers joined the fra-

cas: the resourceful Jay Gould and the

flamboyant Jim Fisk. When the

smoke cleared, Vanderbilt lost, although

subsequent negotiations between

Drew, Eldridge and Vanderbilt produced a

satisfactory compromise agree-

H. Roger Grant is Professor of History

at The University of Akron.

1. Edward Hungerford, Men of Erie: A

Story of Human Effort (New York, 1946), 105-

35; Erie Magazine, 45 (October,

1949), 36.

6 OHIO HISTORY

ment. "Having scraped the oyster

clean," observes historian Maury Klein,

"the participants were content to

toss the empty shell to Gould and Fisk."2

A silver-lining of sorts came with the

"Erie War." The able Gould took

the throttle, and he immediately sought

to rehabilitate the Erie rather than

destroy it. Notwithstanding the

railroad's poor overall condition and its

heavy burden of fixed charges-the conflict

alone cost nearly $10 mil-

lion-Gould's guidance made it a better

property.3

Jay Gould, however, was no magician. The

Erie did not emerge as a pow-

erful concern. He did not have enough

time to work wonders; his enemies

ousted him from the presidency soon

after Jim Fisk's death in early 1872.

And so the company limped along under

the ineffectual leadership of John

Dix and Peter Watson until its second

bankruptcy in 1874.4

A better day for the Erie seemed to have

arrived by the late 1870s;

reorganization in 1878 as the New York,

Lake Erie & Western Railroad

bode well for the struggling pike.

Modernization of rolling stock, stan-

dardization of gauge and creation of an

expanded "system" that included

a 998-mile main line from Jersey City,

New Jersey, to Chicago, Illinois,

highlighted the administrations of Hugh

Jewett (1874-1884) and John King

(1884-1894). In fact, the Erie's new

artery into the Windy City, opened

by its subsidiary, the Atlantic &

Chicago Railway, between Marion,

Ohio, and Hammond, Indiana, in June

1883, sported "air-line" qualities.

Likely this 250-mile extension could

claim to be the best engineered right-

of-way between Ohio and Illinois.5

But the Erie stumbled again. This time

the deadly Panic of 1893, which

made a shambles of American business,

sent the company into its third

bankruptcy. Two years later, in 1895,

the New York, Lake Erie & West-

ern became the Erie Railroad Company.

Shortly, a seasoned railroader,

Frederick Underwood, assumed the

presidency, and he became an out-

standing chief executive. The Underwood

era began in May 1901, and last-

ed for twenty-six years; this would be

the Erie's "Golden Age." The com-

pany extensively upgraded its plant and

its crack passenger trains, most

of all the "Vestibuled

Limited," daily trains 3 and 4 between New York,

Chicago and Cincinnati, symbolized the

"New Erie."6

Toward the end of Frederick Underwood's

tenure, the Van Sweringen

brothers (O.P. and M.J.) of Cleveland,

who were in the process of "col-

2. Edward

Harold Mott, Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie (New

York,

1899), 109-22, 147-60; Maury Klein, The

Life and Legend of Jay Gould (Baltimore. 1986),

81-87.

3. Klein, Jay Gould, 86.

4. Ibid., 92-97, 122-26; Hungerford, Men

of Erie, 171-99.

5. Mott, Between the Ocean and the

Lakes, 230-94; George H. Minor, The Erie System

(New York, 2nd ed., 1936), 53-63.

6. Hungerford, Men of Erie, 211-23.

Erie Lackawanna

7

lecting railroads," won control.

They particularly liked the Erie's low-

grade, double-tracked speedway for coal

trains between Ohio and Chica-

go connections. The carrier remained in

their orbit until their empire col-

lapsed during the Great Depression. The

Erie itself entered bankruptcy in

1938, where it lost most vestiges of

these remarkable Ohioans.7

While the Erie failed to be the

embodiment of a nineteenth century rail-

road, it could likely make that claim

for the twentieth century, in part due

to Frederick Underwood's considerable

skills. Argues historian Richard

Saunders: "It may have been the

quintessential American railroad, a rail-

roader's railroad-double track, heavy

rail, long trains, and high speed."

But the case for the Erie being

"America's railroad" involves more than

track and operations. The saga of the

Erie during the past half century re-

veals that it experienced all the

major forces at work in the complex world

of railroading. The Erie was: a

causality of the Great Depression when a

third of the nation's rail mileage went

into bankruptcy; a dependable mover

of materials and personnel during World

War II; a leader of dieselization,

two-way radios and other cost-saving

technologies; an early player in the

"merger madness" of the 1960s;

and a victim in the 1970s of modal com-

petition, a substantially restructured

rail industry, and a hostile econom-

ic environment.8

Like most railroads, the 2,313-mile

Erie, headquartered in Cleveland

since the days of the Vans, enjoyed

relative prosperity during the 1940s

It emerged from a three-year

receivership (its fourth) in 1941, with a more

streamlined corporate structure and a sense

of optimism. Reduced inter-

est payments and robust wartime earnings

prompted the company to de-

clare a modest dividend in 1942, the

first in sixty-nine years and a proud

moment for management. The press

release, orchestrated by its image-

conscious president (1941-1949), Robert

Woodruff, said in part: ". . . Wall

Street tradition was shattered and

Brokers were dazedly groping for reli-

able replacements for the immemorial

dictums-When Erie Common pays

a dividend there'll be icicles in

hell-and three things are certain-

Death, Taxes, and no dividends for Erie

Common."9

Paying dividends did not mean that the

Erie was splurging. Quite the

contrary, it was "a penny-pinching

property." The company correctly rec-

ognized early on that substantial

savings could be derived from dieseliza-

tion. Even before the war ended,

powerful and sleek General Motors road

7. Ibid., 235-38; Henry S. Sturgis, A

New Chapter of Erie: The Story of Erie's Reorga-

nization, 1938-1941 (New York, 1948), 1-6.

8. Richard Saunders, "Erie

Railroad," in Keith L. Bryant, Jr., ed., Railroads In the Age

of Regulation, 1900-1980 (New York, 1988), 137.

9. Robert E. Woodruff, "I Worked

for the Erie," unpublished ms., ca. 1954, Erie Lack-

awanna papers, The University of Akron

Archives, hereafter cited as EL papers.

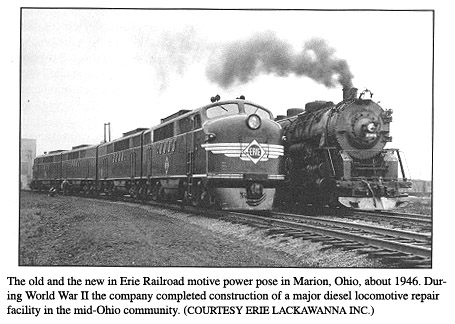

8 OHIO HISTORY

units pulled long trains over the hilly

main line between Marion, Ohio, and

Meadville, Pennsylvania. President Paul

W. Johnston, Sr., who succeed-

ed Woodruff, reported in February 1950

that "The Erie has invested

$34,400,000 in its present ownership of

178 diesel locomotives and now

has one of the highest percentages of

diesel ownership of any railroad in

the east." And he added,

"These locomotives have produced impressive

savings in operating costs and we expect

to realize further savings in the

years to come." The Erie retired

its last steamer three years later. Finan-

cial gains from dieselization, however,

were finite. Then during the lat-

ter part of the 1950s expanding

competition from motor vehicles that rolled

over better roads, including ever-more

abundant "superhighways" and

"thruways," hurt the Erie as

it did other eastern carriers, with the possi-

ble exception of the

"Pocahontas"-region coal roads. The Erie, moreover,

suffered from high terminal costs,

including extensive lighterage opera-

tions in New York Harbor;

"confiscatory" property taxes in New Jersey;

unprofitable commuter trains in the

metropolitan New York City area; and

erosion of on-line manufacturing, for

example, tire production in Akron,

Ohio.10

Understandably management and the

financial community thought

merger might guarantee Erie's solvency.

So in the late 1950s the compa-

ny explored corporate marriage with the

940-mile Delaware, Lackawan-

na & Western, the faltering

"Road of Anthracite," and the 700-mile

Delaware & Hudson, a strategic

bridge line between northern Pennsylvania

and Canada. Although the D&H left

the talks-it considered itself

"wealthy" and refused the

proposed stock-exchange formula-a wedding

still occurred. The new couple was the

3,188-mile Erie-Lackawanna

Railroad (EL), and it met the public

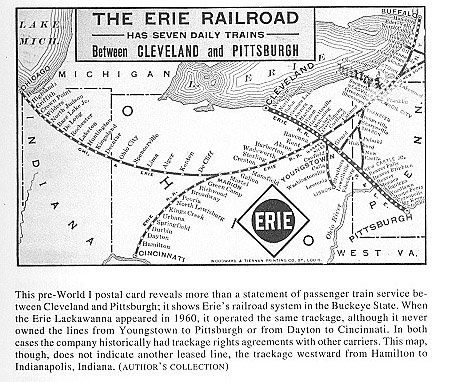

officially on October 17, 1960. 11

After a shaky and discouraging start,

the merged company showed some

promise. Most of all, economies

predicted by the respected consulting firm

of Wyer, Dick & Company became

reality. By 1963 savings amounted to

about $21 million annually rather than

the $13 million initially anticipated.

"Yet if there was an error in the

merger process," contends Charles Shan-

non, a Wyer, Dick associate, "it

was the assumption that both members

of the proposed merged company would be

efficiently operated."12

In fact, that was the problem. The

management team, headed by Mil-

ton McInnes, "Mr. Mac," a

long-time Erie officer who assumed the pres-

10. 1949 Annual Report, Erie Railroad

Company (1950), 3; Interview with Milton G.

Mclnnes, Southbury, Connecticut, 5 June

1989, hereafter cited as Mclnnes interview.

11. Interview with Perry M. Shoemaker,

Tampa, Florida, 19 August 1989, hereafter cit-

ed as Shoemaker interview; Richard

Saunders, Railroad Mergers and the Coming of Con-

rail (Westport, Conn., 1978), 95-118; New York Times, 17

October 1960.

12. Interview with Charles J. Meyer,

Livingston, New Jersey, 25 May 1988; Interview

|

Erie Lackawanna 9 |

|

|

|

idency on November 22, 1960, floundered. The most talked about matter was its failure to control rivalries between former Erie and Lackawanna personnel. As one Erie official remembers, "DL&W fellows had chips on their shoulders." Perhaps they did, since in reality the Erie absorbed their former employer and Erie people frequently, although not always, pros- pered at Erie-Lackawanna. The trouble ran much deeper than Erie versus Lackawanna. Unwilling to continue in the number two position as Chair- man of the Board, Perry Shoemaker, the last president of the Lackawan- na, accepted a lower paying job as head of the sickly Central of New Jer- sey in 1962, leaving the less capable McInnes in charge. Shoemaker was probably the most talented of EL's top officers. Part of the problem in- volved the conduct of Garret "Gary" White, Vice-President-Operations. According to some he was the "bad guy," "a real Tartar." For instance, White refused to modernize the company's obsolete station service. "Gary was a great lover of L.C.L. (less-than-carload) merchandise," re- calls consultant Shannon. "[I]t was killing the company. [LCL] was too expensive to handle; it should have been going by piggyback [trailer-on- flatcar] or by truck." But McInnes was close to White and "he had grown up with these [Erie] people and he couldn't bring himself to do what had to be done." In desperation, the Board of Directors turned to the aging

with Charles Shannon, Arlington Heights, Illinois, 1 October 1988. |

10 OHIO HISTORY

William "Bill" White, former

president of the Lackawanna and the New

York Central and then Chairman and Chief

Executive Officer of the

Delaware & Hudson, "to clean

house." This he did. White fired his broth-

er, Gary, and demoted Mclnnes -"I

was put out to pasture." Gregory

Maxwell, a "good operating

man" whom White had trusted at the New

York Central, became second in command.

(The EL lacked a president

from 1963 until 1965 when Maxwell

assumed the post; White served as

Chairman of the Board.)13

Bill White did his best to save

Erie-Lackawanna. This seasoned exec-

utive, considered by some to be one of

the best railroad leaders of the cen-

tury, worked effectively. He closed six

terminal yards which saved mil-

lions of dollars annually and increased

freight-train efficiency; opened a

heavy car repair facility in Meadville,

Pennsylvania, which, although built

in the late 1950s, had never been

brought into full operation (the "bad-

order" ratio of cars in the EL

freight fleet soon dropped from 15.9 to an

acceptable 4.5 percent); and chipped

away at chronic suburban service

losses in New Jersey, ultimately leading

to healthy state subsidies.14

Yet Bill White and associates in

Cleveland correctly concluded that the

Erie-Lackawanna could not operate in

perpetuity. For the "mega-mergers,"

which eventually produced Penn Central

(Conrail), CSX, and Norfolk

Southern, were starting to develop, and

poor roads, like EL, needed to find

merger partners. While the carrier made

modest yearly profits during

White's tenure (he, unfortunately, died

suddenly in 1967), it was hardly

a money-machine, for as Gregory Maxwell

admitted, "a small cold could

easily turn into fatal pneumonia."15

The Norfolk & Western (N&W), the

future Norfolk Southern, seemed

to offer the best hope for financial

security. As a condition of its merger

with the New York, Chicago & St.

Louis (Nickel Plate) and Wabash rail-

roads in 1964, the Interstate Commerce

Commission (ICC) provided for

inclusion of the Erie Lackawanna in the

expanded N&W. At EL's insis-

tence, the ICC ordered the N&W in

June 1967 to include EL, Delaware &

Hudson and the Boston & Maine

(B&M) in its galaxy of subsidiaries. (The

B&M later decided not to enter.)

Then on March 27, 1968, the Supreme

Court of the United States upheld the

ICC's position. There was rejoic-

ing in Cleveland but none in Roanoke.16

13. Interview with Milford M. Adams,

Perry, Ohio, 18 March 1988, hereafter cited as

Adams interview; Shoemaker interview;

Interview with Gregory W. Maxwell, Moreland

Hills, Ohio, 19 February 1988, hereafter

cited as Maxwell interview; Wall Street Journal,

12 February 1962; McInnes interview.

14. Interview with Robert G. Fuller,

Singer Island, Florida, 26 December 1989, hereafter

cited as Fuller interview; 1966

Annual Report, Erie Lackawanna Railroad Company (1967),

3-5.

15. Maxwell interview.

16. 1967 Annual Report, Erie

Lackawanna Railroad Company (1968), 3-4; Fuller inter-

Erie Lackawanna 11

Norfolk & Western control began on

April 1, 1968. Rather than ab-

sorbing Erie-Lackawanna, the N&W

used a holding company, Dereco, to

protect itself in case of an EL failure.

Dereco, this wholly-owned sub-

sidiary of the N&W, took

Erie-Lackawanna Railroad and merged it into

the Erie Lackawanna Railway. This cost

the N&W about $50 million. Yet

no cash was involved; "it was a

paper deal." The N&W gave EL investors

Dereco preferred stock which it agreed

to exchange after five years for div-

idend-paying N&W common stock.

"It was a good deal for holders of EL

securities," remarked an Erie

Lackawanna financial officer; "after-all, they

owned a railroad with no earnings."17

Immediately, Norfolk & Western

President Herman Pevler sent his able

senior vice-president, John

"Jack" Fishwick, whom he despised and

feared, to Cleveland to head the

"booby prize." Fishwick became presi-

dent of Dereco while Gregory Maxwell

remained as head of Erie Lack-

awanna.

Jack Fishwick labored hard for Norfolk

& Western. Even though he con-

sidered his new job as "almost

impossible since the likelihood of doing

anything with the Erie was slight"

and he did not wish to leave Roanoke

for Cleveland-"I felt that I was

being sent to Siberia," he knew that a good

performance would advance his career at

the parent company. (He was cor-

rect about the potential rewards of his

"high-risk assignment;" he became

president of N&W in 1970 after he

led a successful coup against Pevler.)

Luckily for Fishwick, he got off to a

good start. The EL showed a slight

profit for the first quarter, but as he

recalls, "this figure was really a mat-

ter of luck." For the "Erie

Lack-of-Money" was in his opinion "unprof-

itable and wouldn't ever be made so.

There was too much trackage in the

East."18

The arrival of Jack Fishwick and several

talented associates from Nor-

folk & Western, "the Virginia

Mafia," boosted morale in Cleveland head-

quarters and throughout the railroad.

The company, nonetheless, slipped

badly in the early 1970s. Even though

Erie Lackawanna generated a net

income of $1,259,000 in 1969, it lost

$10,890,000 in 1970; another

$2,247,000 in 1971; and generated a

whopping $16,292,000 deficit be-

tween January 1 and June 26, 1972. (The

latter includes $5.4 million

caused by Hurricane Agnes in June 1972.)

"The balance sheets hemor-

rhaged red ink as revenues

dropped."19

view.

17. Interview with Isabel Hamilton

Benham, New York, New York, 6 June 1989; Inter-

view with John P. Fishwick, Roanoke,

Virginia, 9 May 1989, hereafter cited as Fishwick in-

terview.

18. Fishwick interview; Maxwell

interview.

19. 1972 Annual Report, Dereco, Inc. (1973),

3, 5; 1972 Annual Report, Erie Lackawanna

12 OHIO HISTORY

Admittedly Agnes, an unusually intense

storm which blew out of the

Gulf of Mexico and dumped record

rainfall throughout much of New

York's Southern Tier and adjoining

areas, axed Erie Lackawanna. The

company sustained damage to 375 miles of

trackage; especially hard hit

was its main line between Owego and

Salamanca, New York. Crews

worked continuously for twenty-one days

to restore service, and the price

was high: extra wages, lost revenues,

and the cost of rerouting traffic. This

was too much. The EL did not wait for

waters to drain completely from

its flood-ravaged arteries before it

filed for bankruptcy.20

Had the heavens not opened over New York

and Pennsylvania in June

1972, the Erie Lackawanna would

undoubtedly still have failed. Several

forces worked against the road's

success. One involved loss of consider-

able traffic through the Maybrook, New

York, "gateway." For decades the

Erie and then the EL interchanged

hundreds of cars daily with the New

York, New Haven & Hartford (New

Haven) for delivery to and from

Boston and other southern New England

destinations. Recalls Gregory

Maxwell: "On Day 1 of the Penn

Central merger [February 1, 1968], the

company [Penn Central] sent an Assistant

General Manager to New

Haven from Philadelphia to destroy the

connection at Maybrook." He did

his job effectively. "With the slow

down policy of the PC, it might take a

week for the cars to arrive [in

Boston]." Before this happened, cars from

the EL would reach Maybrook at eight or

so in the morning and then be

in Boston that evening. Of course, Penn

Central did not want to "short-

haul" itself; it sought to move

traffic from Chicago and other midwestern

points to New England entirely over its

own rails, namely the former New

York Central to Albany and the former

Boston & Albany, an NYC affil-

iate, to Boston. The impact of the

slowdown was staggering: the EL ex-

perienced a decline of 34,000 cars in

1969 with a loss of $9.5 million of

gross revenues; 22,900 cars in 1970 and

an $8.3 million decline of gross

revenues; and 16,925 cars in 1971 and

$4.8 million in losses. In Decem-

ber 1969 the company won an order from

the ICC to restore service and

made a second complaint in May 1970 when

little improvement had oc-

curred. Because EL accepted conditions

of the Penn Central merger of

1968, it could not appeal to the federal

courts; it was stuck with the reg-

ulatory process. Eventually the ICC

reopened the gateway but permanent

damage had been done; shippers seemed

leery of using the old Erie-New

Haven route and for good reason.21

Railway Company (1973), 2-3; Interview with Richard H. Hahn, Cleveland, Ohio,

32 March

1989, hereafter cited as Hahn interview.

20. Minutes of the Board of Directors,

Erie Lackawanna Railway Company, 26 June 1972,

59-60, EL papers.

21. Maxwell interview; 1970 Annual

Report, Dereco, Inc. (1971), 5-6; 1971 Annual Re-

port, Dereco, Inc. (1972), 6.

|

Erie Lackawanna 13 |

|

Government's fostering of what business historian Albro Martin has la- beled "Enterprise Denied" seemed ubiquitous. Like all Class I roads, with exception of the Florida East Coast after 1963, labor costs adversely af- fected the Erie Lackawanna. During the 1960s the company made little headway against "full-crew" laws in New York, Ohio and Indiana. (In the latter state, an EL freight train needed a six-person crew if it were longer than seventy cars.) And, too, the railroad was still required to have fire- men on diesel locomotives. When "featherbedding" was coupled to in- dustry-mandated wage increases and an employee protection agreement as a condition of the N&W inclusion case, which meant life-time tenure after 1968, the company lost even more money. As Maxwell argues, "La- bor was bleeding us dry." Even the former general chairman of the Broth- erhood of Locomotive Engineers agrees: "I'm sure that wage and protec- tion agreements severely hurt the carrier, but they were legally ours to have."22 The federal government, most of all, continued to foster highway ex- pansion. By the early 1970s the network of interstate highways, created

22. Maxwell interview; Interview with J. D. Allen, Cleveland, Ohio, 10 May 1989. |

14 OHIO HISTORY

by the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956,

covered New York, New Jer-

sey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and

Illinois like a morning dew. Truck

tonnage increased and railroad freight

traffic dropped. Revenue carload-

ings in the Eastern District of the

nation, for example, fell from 10,071,261

in 1970 to 9,009,574 by 1972, and

similar data from the EL reflected this

downward trend.23

There is usually the expectation that a

railroad bankruptcy will give way

to a re-energized company. In the case

of the Erie this had been so after

its reorganizations of 1861, 1878, 1895,

and 1941. Yet the failure of Erie

Lackawanna in 1972 did not hold as much

promise, although management,

especially Maxwell, and the road's two

trustees felt during the latter half

of 1972 and much of 1973 that it might

be possible to restructure this Ohio-

based carrier. The Norfolk &

Western, though, did not care. It was de-

lighted to "get out from under the

Erie." N&W may have lost its invest-

ment in Erie Lackawanna Railway through

Dereco, but it "made a damn

lot of money with the tax losses,"

in excess of $100 million and possibly

as high as $150 million.24

The reorganization process started

auspiciously. The judge named to

oversee the bankruptcy was Robert

Krupansky of the Northern District of

Ohio. He was bright, honest and a

"workaholic;" moreover, he had served

earlier in his legal career as trustee

for the reorganization of a midwest-

ern brokerage firm. "I knew

something about business bankruptcies." But

Judge Krupansky admitted that this was a

"highly complex" case, and so

he sought counsel from judges involved

in the now fallen Penn Central,

Reading, and Lehigh Valley railroads.

Judge Krupansky grew close to John

Fullam, judge in the Penn Central case.

"He acted as my adviser." Judge

Krupansky quickly decided that the

trustees (two or possibly three) must

possess extraordinary business skills

and financial connections. "I want-

ed qualified people and ideally ones who

had a positive reputation in the

financial world. This was a national

case with major national significance."

Fortunately, he located two top-notch

Clevelanders, Thomas Patton, re-

tired chairman of the board of Republic

Steel Corporation, and Ralph

Tyler, Jr., retired chairman of the

board of the Lubrizol Corporation. As

the judge later reflected, "I had

two big-league businessmen with nation-

al connections." More exactly what

he had were two trustees who com-

plemented each other superbly: Patton

was an able businessman and civic

leader and Tyler was "a lawyer's

lawyer." They, together with Gregory

Maxwell, made an exceptionally strong

team.25

23. Yearbook of Railroad Facts (Washington,

D.C., 1973), 25.

24. Fishwick interview; Interview with

Harry G. Silleck, Jr., Cleveland, Ohio, 19 Octo-

ber 1988, hereafter cited as Silleck

interview.

25. Interview with Robert Krupansky,

Cleveland, Ohio, 21 February 1989, hereafter cit-

Erie Lackawanna

15

Trains continued to run and the overall

quality of service remained sur-

prisingly high. The company ordered

twenty-six 3600 horsepower loco-

motives and leased or rebuilt additional

rolling stock, although it experi-

enced a critical shortage of all types

of freight cars and trailers. "An

estimated $17 million of revenues were

lost due to these shortages dur-

ing [1973]," stated that year's Annual

Report. While Erie Lackawanna

lacked funds for an adequate rail and

tie replacement program, it made

some track improvements. Remembers

Joseph Neikirk, the road's vice-

president for operations, "We

bought a lot of ballast!" Trains generally

moved at speeds of 45 to 50 mph; the

Erie had been a 60 mph freight hauler

during the 1940s and 1950s. Still the

company enjoyed a coveted contract

with United Parcel Service, like the EL,

a consumer-oriented concern.

"UPS liked the schedules, even

though the Erie was no speedway." And

the EL wisely expanded its intermodal

operations. Railway Age reported

in an October 1974 feature story,

"EL: A Winning Strategy Against Long

Odds," that "EL

trailer/container volume in 1973 was not just up, it was

up to a record-high of almost 190,500

units. EL intermodal revenues were

not just up, they were up to a

record-high of more than $46 million." Thus

for the latter part of 1972 and 1973 the

company operated on a positive

cash-flow basis: its power to generate

revenues ($289,379,364 in 1973)

and the court's prohibition of payments

of property taxes and interest on

its debt made this possible.26

While piggyback service became nearly

twenty percent of Erie Lack-

awanna's total revenues in 1973, other

bright spots on the traffic front were

not apparent. Economic conditions

worsened in the nation and through-

out the EL's service territory in 1974

and 1975. Double-digit inflation that

came in the wake of the Arab oil boycott

of 1973, a nationwide recession,

and the accelerating decline of

"smoke-stack" industries, especially in the

steel-producing Mahoning Valley, once

called the "breadbasket of the

Erie," damaged earnings. The

question most commonly being asked

among senior management on the

thirteenth floor of Cleveland's Midland

Building was "What should Erie

Lackawanna do?"27

The railroad was not alone with

concerns about the future. Carriers in

the Northeast were rapidly declining;

indeed, the region by the early 1970s

had become a railroad graveyard.

Casualties included the Central of New

Jersey in March 1967; the Boston &

Maine in March 1970; Penn Central

ed as Krupansky interview; Interview

with Thomas Patton, Cleveland, Ohio, 7 February 1989,

hereafter cited as Patton interview.

26. 1973 Annual Report, Erie

Lackawanna Railway Company (1974), 4-5; Interview with

Joseph Neikirk, Norfolk, Virginia, 16

May 1989; "EL: A Winning Strategy Against Long

Odds," Railway Age, 175 (28

October 1974), 24, 26, 29.

27. Maxwell interview; Hahn interview.

16 OHIO HISTORY

in June of that year (America's greatest

business failure); Lehigh Valley

a month later; Reading in November 1971;

and the Lehigh & Hudson Riv-

er in early 1972. This obvious crisis

worried more than railroad managers,

workers and investors; it prompted

politicians to act, "but not until these

dead dogs were dropped on the doorsteps

of the federal government."

There existed widespread fear of the consequences

of a court-threatened

liquidation of Penn Central. Some

troubled carriers, however, already had

received assistance from both state and

federal authorities; EL, for one,

had forced New Jersey to assume the

principal costs of its highly unprof-

itable commuter service in the

mid-1960s, and it benefitted from passage

of the Emergency Rail Facilities

Restoration Act in 1973, which provid-

ed generous loans to repair roadways,

structures and equipment damaged

by Hurricane Agnes. But massive infusions

of funds, whether direct

grants, guaranteed loans or a

combination of the two, were needed ur-

gently. After considerable debate,

Congress passed in late 1973 the Re-

gional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973

or 3R Act. In order to conduct the

planning process necessary to aid the

bankrupts, the measure created the

United States Railway Association

(USRA). Thus the process began that

led to formation of the quasi-public

Consolidated Rail Corporation, Con-

rail, in April 1976.28

Since Erie Lackawanna decided to

reorganize in the traditional fashion,

it rejected participation in the

Northeast railroad reorganization under the

3R Act, and the court agreed on April

30, 1974. Recalls Judge Krupansky,

"A successful reorganization was initially

in sight." Instead, the EL and

also the Boston & Maine attempted to

reorganize on an income basis un-

der Section 77 of the Bankruptcy Act;

the other bankrupts, however, will-

ingly accepted inclusion in some future

type of Conrail system.29

Although the United States Railway

Association worried about how rail-

roads in the Northeast might be

restructured without Erie Lackawanna, its

concerns came to naught. The

ever-worsening economic climate forced

EL to reconsider. The company suffered a

net income loss of nearly

$17.2 million during 1974, and its

forecasts for 1975 were even more

gloomy. As the road said officially,

"[I]t became obvious that Erie Lack-

awanna would need financial assistance

from the Federal Government to

carry on its operations."

Therefore, on January 9, 1975, trustees Patton and

Tyler asked the USRA for inclusion in

its planning. They decided that their

only recourse was to come under the

government's wing and thus to qual-

28. Saunders, Railroad Mergers, 295-323;

The Great Railway Crisis: An Administrative

History of the United States Railway

Association (Washington, D.C., 1978),

170-211; In-

terview with Albro Martin, Detroit,

Michigan, 27 September 1991.

29. Krupansky interview; Silleck

interview.

Erie Lackawanna 17

ify for funds appropriated under the 3R

Act to keep bankrupt carriers op-

erating while the process of

restructuring continued. Judge Krupansky

agreed.30

The Erie Lackawanna's inclusion in

Conrail required considerable ef-

fort. Since the 3R act had to be amended

to include the EL, trustees turned

to Harry Silleck, a partner of the New

York law firm of Mudge, Rose and

an experienced railroad attorney,

"probably the best in the business," to

draft the necessary legislation. The

enabling measure that he devised said

that "a company in Section 77 could

either reorganize or liquidate its as-

sets, subject to such terms and

conditions that the Reorganization Court

found reasonable." Some opposition

developed. The Department of Trans-

portation objected to the EL trustees

having two chances to make up their

minds and it fussed about the cost of

inclusion. However, public opinion

favored EL's request and Patton and Silleck

worked carefully with Re-

public Steel's lobbyists in Washington

to win Congressional approval in

February 1975.31

The cash-starved Erie Lackawanna soon

received substantial amounts

of federal assistance; the government

provided nearly $50 million between

March 1975 and April 1976. Under Section

213 of the 3R Act, EL got

$27.9 million in outright grants

"to defray certain costs of essential trans-

portation service." And it received

under Section 215 approximately

$10 million, which it also had no

obligation to repay, for maintenance. The

government likewise provided about $11

million to help meet EL's ma-

turing equipment debt.32

While the company got crucial public

monies, the United States Rail-

way Association moved toward formation

of its "Final System Plan." This

document appeared on July 26, 1975, and

included sale of a major segment

of the Erie Lackawanna-about 1,200 miles

of main line from northeast

Ohio to New Jersey-to the Chessie

System; Conrail would acquire the

bulk of the EL' s remaining trackage.

But Chessie did not buy. The inability

of that company to reach agreement with

labor unions over employee pro-

tection prompted it to withdraw from the

scheme in February 1976.33

Until much of Erie Lackawanna entered

Conrail on April 1, 1976, the

trustees and top management considered

several options during 1975 and

early 1976. As Thomas Patton observes,

"Things were volatile during

those months." Initially United

States Railway Association planners liked

30. Financial Reports for Year Ended

December 31, 1975 and Three Months Ended March

31, 1976, Erie Lackawanna Railway

Company (1976), 1-4; Silleck

interview.

31. Interview with Bernard V. Donahue, 9

March 1988, hereafter cited as Donahue in-

terview; Silleck interview; Patton

interview.

32. Silleck interview; Financial

Reports, 1976, 1-3.

33. The Great Railway Crisis, 512-60;

Silleck interview.

18 OHIO HISTORY

the concept of "MARC-EL," an

acronym for Mid-Atlantic Railroad Cor-

poration-Erie Lackawanna. It would

consist of the Central of New Jersey,

Lehigh Valley, Reading and EL, and

seemed viable. Indeed, Charles

Bertrand, Reading's president, became

MARC-EL's great "messiah."

EL liked the idea, too, although Gregory

Maxwell wanted to add Penn Cen-

tral's "Big Four" line from

Galion, Ohio, through Indianapolis to St. Louis.

In reality MARC-EL would become

"Little Conrail" with "Big Conrail"

consisting of the Penn Central (less its

Galion-St. Louis line) and the

Ann Arbor, a mostly Michigan carrier

that had failed in October 1973.

Even though "MARC-EL would have

worked," pressure became great

for "three systems east"

(Conrail, Norfolk & Western and Chessie) rather

than four, and so MARC-EL was stillborn.34

A less likely possibility for a home for

Erie Lackawanna outside of gov-

ernment sponsorship came from the

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe. This

prosperous western road had long been

Erie's principal interchange part-

ner in Chicago, and it obviously had a

strong interest in the fate of EL. Ex-

cept for a detailed study, little

happened. "I told John Reed [Santa Fe pres-

ident]," recalls Gregory Maxwell,

"that we were too far along with our

commitment to Conrail." Yet he

added, "I wish that we could have got-

ten together sooner."35

About the same time as the Santa Fe

feeler, an attorney who represent-

ed Nelson Bunker Hunt and William

Herbert Hunt, the colorful Texas oil-

men, contacted EL about

"affiliation with a western carrier." Apparently

the Hunt brothers had become interested

in railroads; they already con-

trolled a shortline in Oklahoma.

Although EL sent an officer to Dallas with

a package of financial data, nothing

materialized.36

Equally ill-fated was a suggestion of

employee ownership. It was "dis-

cussed internally" in Cleveland and

more so among workers in Marion,

location of the company's principal

diesel shops and home of a major yard.

The model would have been the Chicago

& North Western Transportation

Company, which embarked upon an employee

ownership scheme in 1972.

"We had good relations with our

employees," relates Maxwell, "and it

might have worked, particularly at an

earlier point in time." But as an

EL electrician recalls, "I was

afraid it [employee ownership] would go

down the tubes. I wasn't about to invest

any of my money in such a scheme,

although I wanted the company to stay in

Marion." Perhaps Maxwell was

too optimistic.37

34. Patton interview; Maxwell interview.

35. Maxwell interview.

36. Adams interview.

37. Adams interview; Maxwell interview;

Interview with Leonard Kellogg, Marion, Ohio,

12 May 1989, hereafter cited as Kellogg

interview; Marion (Ohio) Star, 16 August 1975.

|

Erie Lackawanna 19 |

|

|

|

The Erie Lackawanna Railway Company disappeared as a railroad on April 1, 1976. It was a sad day, most of all for thousands of dedicated em- ployees. "We didn't want Conrail. We knew that we wouldn't be number one in this arrangement." And they were correct. Workers, particularly those in Ohio, who did not retire or take severance pay, commonly faced relocation to former Penn Central offices and facilities, since "Penn Cen- tral people came out on top with Conrail.... Penn Central's lines, not Erie's, were used by Conrail." For example, the former EL workforce in Marion, numbering about 1,300, declined dramatically, even though em- ployees, civic leaders and others had battled since the summer of 1975 to protect these jobs. Their MONEY (Marionites Opposed to the Negation of the Erie Yards) grass-roots crusade collected thousands of signatures on petitions that opposed any downgrading, but it found few supporters outside the community.38 Fortunately, the world did not end for those associated with this "fall- en flag." Employees who had worked for Erie Lackawanna at least five

38. Kellogg interview; Marion Star, 23 August 1975, 6 September 1975, 7 October 1975. |

20 OHIO HISTORY

years kept their jobs, found new ones,

or took cash settlements. And some

bondholders eventually "made a

killing."39

The losers of the Erie Lackawanna's

absorption into Conrail were

those shippers who no longer enjoyed

access to the "Friendly Service

Route." Particularly hard hit were

those along the former Erie in Ohio and

Indiana. Not only did Conrail quickly

end through service between New

York and Chicago, but scrappers

subsequently pulled much of the track.

By the early 1990s the line had become

mostly a memory west of Akron,

although scattered former shippers

retained modest service. These are cus-

tomers of shortlines-for example,

Akron-Barberton Belt Railroad; Ash-

land Railway; and Spencerville &

Elgin Railroad in Ohio, and Tippeca-

noe Railroad in Indiana-that operate

small segments of former Erie

Lackawanna main line.40

The wake of Erie Lackawanna continues.

Likely the outcome, mostly

known, will be one of the most

successful large business liquidations in

the nation's history. Trustees Patton

and Tyler (who died in 1986), their

legal counsel, their remaining employees

and Judge Krupansky effectively

handled a myriad of problems and

details. After protracted and forceful

negotiations, they persuaded the

government to pay more than $350 mil-

lion for property transferred to

Conrail. This was a major victory; the gov-

ernment's initial offer was about $60

million.41

With a favorable settlement with Uncle

Sam, Erie Lackawanna Railway

reorganized as Erie Lackawanna Inc. (EL

Inc.) on November 30, 1982.

Since then this Cleveland-based firm has

gone forward with the process

of liquidation. Sales of track,

equipment and real estate not taken by Con-

rail and other assets, even old stock

certificates, produced considerable

income. These funds have made possible

full payment to taxing authori-

ties and creditors, including secured

bondholders. Remaining monies ei-

ther have or will go to EL Inc.

stockholders, former owners of unsecured

bonds. By 1992 the last traces of Erie

and Erie Lackawanna will disappear,

a happy ending to the old "Weary

Erie" and "Erie Lack-of-Money."42

39. Silleck interview.

40. Interview with Harry Zilli, Jr.,

Cleveland, Ohio, 5 April 1989, 12 June 1989; Silleck

interview.

41. Journal of Commerce, 25 April

1983; Donahue interview.

42. Zilli interview.

H. ROGER GRANT

Erie Lackawanna: An Ohio Railroad

The Erie Railroad possessed a strange

past. In the nineteenth century it

could claim to be an unusual road. For

one thing, it was America's first

long-distance trunk line. Under the

corporate banner of the New York

& Erie Railway, the company in April

1851 completed a 483-mile route

"Between the Ocean and Lakes,"

linking the New York communities of

Piermont on the Hudson River with

Dunkirk on Lake Erie. The railroad

also extolled its distinctive broad or

"Erie Gauge," the impressive six feet

between its iron rails rather than what

emerged as the standard width of

four feet eight and one-half inches.

(Later the company advertised ex-

tensively that because of its uncommon

construction, "[It] ... is select-

ed over and over again for handling

oversize shipments because it is fa-

mous for the highest and widest

clearances of any eastern railroad.")1

But there was a dark side to Erie. Its

building process took nearly a gen-

eration, in part because self-serving

politicians forced it to push through

New York's rugged and sparsely settled

"Southern Tier" of counties. As

a result the road missed direct ties to

the burgeoning cities of New York

and Buffalo and skirted the traffic

centers of northeastern Pennsylvania,

thus weakening its earnings

capabilities. The property was hardly a mod-

el for emulation. In the 1850s it was in

such wretched shape that Edward

Harold Mott, the Erie's first chronicler,

observed that it "became notori-

ous for the insecurity of travel upon

it." When reorganized and revitalized

during the Civil War, the Erie Railway

soon became the "Scarlet Woman

of Wall Street." The unscrupulous

speculator, Daniel Drew, discovered

the company and manipulated its stock.

Then, in 1867, a three-way bat-

tle erupted for control, with interests

represented by the wily Drew; John

Eldridge of the Boston, Hartford &

Erie; and "Commodore" Cornelius

Vanderbilt of the New York Central. Two

other financiers joined the fra-

cas: the resourceful Jay Gould and the

flamboyant Jim Fisk. When the

smoke cleared, Vanderbilt lost, although

subsequent negotiations between

Drew, Eldridge and Vanderbilt produced a

satisfactory compromise agree-

H. Roger Grant is Professor of History

at The University of Akron.

1. Edward Hungerford, Men of Erie: A

Story of Human Effort (New York, 1946), 105-

35; Erie Magazine, 45 (October,

1949), 36.

(614) 297-2300