Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

RICHARD M. BUDD

Ohio Army Chaplains and the

Professionalization of Military

Chaplaincy in the Civil War

While the study of military chaplains is

fascinating if only because of the

apparent incongruity of peacemakers

serving in an institution of warmakers,

military chaplaincy during the American

Civil War is of particular interest

because of the insight it offers into

the development of the office of chaplain.

While chaplains had been appointed by

Congress as far back as 1775, their role

and status were not clearly defined, and

their qualifications for appointments

were not well established. The wartime

appointment of chaplains on such an

unprecedented and massive scale raised a

host of issues concerning the role of

the chaplain in war, his status as a

participant in battle, and the evolution of

chaplaincy as a profession. Evidence

suggests that the Civil War chaplains

from Ohio played a typical and

substantial role in the professionalization and

definition of American military

chaplaincy.

Civil War chaplaincy has been studied

from Union and Confederate stand-

points, from the viewpoint of particular

religious denominations, and from the

experiences of individual chaplains. To

date no one has studied the subject

from the perspective of one state's

experience. Ohio appointed approximately

one-tenth of the 2,500 Union army

chaplains who served in the Civil War.1 By

concentrating closely on the experience

of these approximately 240 Ohio men

and then generally comparing their

experiences with those of chaplains in other

northern states, it is possible to

produce a reasonably accurate and typical pic-

ture of what chaplaincy was like in the

Federal armies from 1861 to 1865.2

Richard M. Budd is a Ph.D. candidate in

military history at The Ohio State University.

1. Herman A. Norton, Struggling for

Recognition: The United States Army Chaplaincy, 1791-

1865. History of the United States Army Chaplaincy, vol. 2

(Washington, D.C., 1977), 108.

2. For a comprehensive view of Union

chaplains see Warren Bruce Armstrong, "The

Organization, Function, and Contribution

of the Chaplaincy of the United States Army, 1861-

1865" (Ph.D. diss., University of

Michigan, 1964). For the official accounts see Roy J. Honeywell,

Chaplains of the United States Army (Washington, D.C., 1958) and Norton, Struggling for

Recognition. For a recent listing of articles on Union chaplains see

Edmund S. Redkey, "Black

Chaplains in the Union Army," Civil

War History, 33 (December, 1987), 332-50.

For a detailed examination of

Confederate army chaplaincy, which offers many interesting par-

allels to the Union road toward

professionalization, see Herman A. Norton, "The Organization and

Function of the Confederate Military

Chaplaincy, 1861-1865" (Ph.D. diss., Vanderbuilt University,

6 OHIO HISTORY

Chaplains in the Regular Army on the eve

of the Civil War were not an inte-

gral part of the military organization;

rather they existed more as hired civilians

grafted on to the army stem. Army

chaplains wore the uniform of their calling

rather than of the United States

government. While generally treated as officers

(e.g., they were given housing

equivalent to officers), they had no official rank,

no provision for promotion, no

supervisory organization of their own, and little

sense of cohesion as a corps. Chaplains,

in short, were very much on their own.

Outside of the regular process of

ordination, American churches were involved

only haphazardly in the selection or

qualifications of those clergymen hired by

the government to serve at military

facilities. Choosing a chaplain was very

much a local decision of the commander

and the administrative council of the

post. Official delineation of the

chaplain's duties was limited. For instance,

chaplains were required to hold

religious services and serve as schoolmasters

for children of military families; the

government was often as concerned about

chaplains' abilities as teachers as much

or more than their qualifications as pas-

tors. The conditions of the frontier

army were not such as to bring to the atten-

tion of Congress issues such as a more

detailed enumeration of chaplains'

duties, combatant status, pay, rank,

organization, qualifications, or appointment

procedures. Such matters became

pertinent only when the country became

involved in a major war requiring large

numbers of chaplains and their partici-

pation in battlefield scenarios.

In the spring of 1861 there were only

thirty chaplains in the whole Regular

Army, and all of them were post

chaplains.3 The practice of assigning chaplains

to regiments, which had been the

practice from colonial times through the War

of 1812, had been replaced by having

contract chaplains at military posts.4

Scattered frontier units had no occasion

to form up as regiments and conse-

quently no need for regimental

chaplains. The outbreak of war in April 1861

changed all of that, as the northern

states began to raise dozens of volunteer

regiments, each with its own chaplain.

General Order 15 of 4 May 1861 autho-

rized the regimental commander to

appoint a chaplain upon a vote of his field offi-

cers and company commanders, and such

regimental chaplains were to be

regularly ordained and to receive the

pay and allowances of a captain of cavalry.5

1956) and Frank L. Hieronymus, "For

Now and Forever: The Chaplains of the Confederate States

Army" (Ph.D. diss., University of

California, Los Angeles, 1964). See also Sidney J. Romero, "The

Confederate Chaplain," Civil War

History 1 (June, 1955). For an overview of chaplains in the larg-

er context see Gardner H. Shattuck, A

Shield and a Hiding Place: The Religious Life of the Civil

War (Macon, 1987).

3. Honeywell, Chaplains of the United

States Army, 104.

4. A handful of chaplains served with

American forces in the war with Mexico. Two Roman

Catholics priests served on an at-large

basis with Zachary Taylor's army through special appoint-

ment by President Polk, and a very few

brigade chaplains were authorized for volunteer regiments

in legislation of 11 February 1847. This

brief return to chaplains within the tactical organization of

the army ended with the cessation of

hostilities and the return to a peacetime structure. Norton,

Struggling for Recognition, 64-77.

5. Honeywell, Chaplains of the United

States Army, 104. This allowance meant that the chap-

Ohio Army Chaplains 7

As Ohio regiments began to organize, the

procedures outlined in General

Order 15 became the pattern. In the

enthusiasm of the moment most Ohio regi-

ments were able to obtain a chaplain.

There were no age limits, nor were there

any educational requirements. Ordination

was required but there was no

method of ensuring accreditation from a bonafide

denomination. Not until July

1862 did the law require chaplains to be

members of an "authorized ecclesiasti-

cal body" or recommended by

"not less than five accredited ministers" of such

a denomination.6 Apparently

even the requirement that all chaplains be

ordained ministers was not always

followed. One Union chaplain wrote that

"men who were never clergy of any

denomination" became chaplains and that

sometimes "the position was given

to an irreligious layman."7 General Order

15 had specified that the chaplains must

be Christians, but the new law also

dropped this requirement.8

Successful candidates for the post of

regimental chaplain were usually cler-

gymen known personally by the officers

of the regiment. Jefferson Harrison

Jones, who became chaplain of the 42d

Ohio Volunteer Infantry (O.V.I.), was a

close personal friend of the regiment's

colonel, James Abram Garfield. The

colonel invited Jones to preach for the

men at Camp Chase, much like a con-

gregation listening to a potential

candidate being considered for a pastoral call.

Shortly thereafter the colonel offered

Jones the chaplain position.9 The same

happened to Wilhelm Stangel, who became

chaplain of Cincinnati's 9th O.V.I.

The Germans of that unit, many of whom

were free-thinking "Forty-Eighters,"

liked Stangel's "intelligent and

liberal tone" and the fact that "neither he nor the

regiment were too pious."10 Confirmation

and the issuance of the commission,

lain received money to furnish himself

with a horse and to maintain it, whether or not the chaplain

actually did keep a mount. This also meant

that the chaplain made more money than a captain of

infantry.

6. Honeywell, Chaplains of the United

States Army, 105.

7. Norton, Struggling for

Recognition, 85.

8. Ibid., 92. Ohio's controversial

Democratic congressman, Clement L. Vallandigham, had ini-

tially sought to remove the stipulation

for Christian chaplains but had been overruled by his fellow

lawmakers. Later his suggestion was

passed into law with the legislation of 22 July 1862. While no

Ohio regiments appointed Jewish

chaplains, the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry and the 54th New York

Infantry did. Rabbis also were appointed

to posts as hospital chaplains in Philadelphia and

Louisville. This study's limited

investigation into the denominational profile of Ohio's chaplains

has identified only two Roman Catholics:

William T. O'Higgins and Edward P. Corcoran, of the

10th and 61st Ohio Volunteer Infantry,

respectively. These two priests represented only .8 percent

of the total number of Ohio's regimental

chaplains. Nationally only forty-three priests served Union

regiments (1.7 percent). Aidan Henry

Germain, Catholic Military and Naval Chaplains

(Washington, D.C., 1929), 58,65-66, 92.

The largest identifiable denominational affiliation of Ohio

chaplains was the Methodist Episcopal

Church. Other denominations identified include

Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Disciples

of Christ, Baptists, and Lutherans (for the German immi-

grant regiments).

9. James A. Garfield to Lucretia

Garfield, 8 October 1861, and James A. Garfield to Lucretia

Garfield, 1 December 1861, James A.

Garfield Papers (Washington, D.C., Presidential Papers

Microfilm, 1970), reel 5.

10. Constantin Grebner, We Were the

Ninth: A History of the Ninth Regiment, Ohio Volunteer

8 OHIO

HISTORY

however, still were the prerogatives of

the governor. Colonel C.W.B. Allison's

letter to Governor David Tod of 24 June

1862 is typical. The officers of

Allison's unit had voted on the second

ballot unanimously for The Reverend

Edwin P. Goodwin, and the colonel

informed the governor that Goodwin

would be appointed regimental chaplain,

subject to Tod's approval.11

All sorts of men sought the chaplain

position. Some were young men with-

out a church of their own and looking to

make a living. Major General Jacob

Cox, one of Ohio's own, recalled the

visit of one "clerical adventurer" who

before seeking a chaplain position

wanted to know "just what the pay and

emoluments of a Captain of Cavalry"

were.12 Some applicants were older men

like one forty-five year old pastor from

Dayton who claimed to have much

experience with young people and said he

could stand the "rough and tumble

life" in the army.13 Many

clergymen came highly recommended for their expe-

rience, education, piety and patriotism.

William G. Brownlow, a Tennessee

Unionist who became chaplain of the 69th

O.V.I., had been offered a

Confederate chaplaincy.14 Often

it was the local military committee that wrote

the recommendation. On at least two

occasions Ohio clergymen were put for-

ward for chaplain because of their

superior recruiting efforts on behalf of the

regiments.15 Religion and

patriotism were often linked in the minds of many

people both North and South during the

Civil War.

Frequently chaplains came from the ranks

of privates, as it was fairly com-

mon practice for ministers to enlist as

regular soldiers; perhaps the job of chap-

lain was already filled, perhaps the

minister wanted to win the trust of the men

first before seeking the job of chaplain

or maybe he just had a desire to fight for

the Union. Both the Reverend S.T. Boyd,

a private in the 120th O.V.I., and

Elder James Craft, a private in the 1st

Ohio Volunteer Cavalry (O.V.C.), sought

chaplaincies.16 Erastus M.

Cravath, who enlisted as a private in Company G of

the 101st O.V.I., was promoted to

chaplain the next day. George Scott was First

Sergeant in Company C of the 96th O.V.I.

before he was selected to be regi-

mental chaplain. Frederick J. Griffith,

a Methodist minister, was age forty-one

Infantry, April 17,

1861, to June 7, 1864, Frederic

Trautman, trans. and ed., (Kent, 1987), 67.

Originally published as Die Neuner.

11. Colonel C.W.B. Allison to Governor

David Tod, 24 June 1862, Governor David Tod

Papers, Ohio Historical Society,

Columbus, Ohio. Hereafter cited as OHS.

12. Jacob Dolson Cox, Military Reminiscences of the Civil War, (New York, 1900), vol. 1, 35.

13. J. Ellis to Governor David Tod, 16

August 1862, Governor David Tod Papers, OHS.

14. "You will remember that General

[Gideon] Pillow tendered Brownlow that position in the rebel

army, and that he gave the

characteristic reply that when he made up his mind to go to h-ll he would cut

his throat and not take a circuitous

route through the Southern Confederacy." Lewis D. Campbell to

Governor William Dennison, 4 November

1861, Governor William Dennison Papers, OHS.

15. G.C. Townsend to Governor David Tod,

11 August 1862, and M.G. Mitchell to Governor

David Tod, 11 August 1862, Governor

David Tod Papers, OHS.

16. S.T. Boyd to Governor David Tod, 27

August 1862, and C.W. Show to Governor David

Tod, 3 September 1862, Governor David

Tod Papers, OHS.

Ohio Army Chaplains 9

when he "dropped his Bible and

buckled on his sword" to become a captain in

the 53d O.V.I. When Chaplain Thomas

McIntyre resigned from the unit,

Griffith was commissioned as a chaplain

to replace him. Nor was Griffith the

only other minister who had served as a

line officer, as one or possibly two

other Methodist ministers served in the

regiment in line billets. George Pepper,

another Methodist preacher, had been

selected as captain because of his recruit-

ing efforts in the 80th O.V.I. Pepper

often performed religious functions for his

regiment, and when his unit's chaplain

resigned due to illness, Pepper applied

for and was chosen as the replacement

chaplain.17

Not everyone chosen to be a chaplain was

necessarily the best person for the

job, and not everyone was clear as to

the qualifications necessary to be chaplain

or the need for ordination. On at least

one instance the Governor of Ohio was

asked to clarify the matter.18 Moreover,

some were more qualified by their

friendships and personal contacts than

by their pastoral abilities or religious

interest. Even Chaplain Pepper, an

outspoken defender of army chaplaincy,

admitted there were a few

"drones" and "uneducated imposters" among the

regimental chaplains.19 The

army rectified this situation somewhat in 1862

when the War Department instructed

regimental commanders to evaluate their

chaplains for fitness and to discharge

those who were unsuited.20

The State of Ohio appointed chaplains to

volunteer regiments of infantry,

cavalry, and artillery. Most of the 208

Ohio regiments had a chaplain assigned

sometime during the life of the unit, as

chaplains served in 84 percent of the

Buckeye regiments. The figures show that

162 of the 192 infantry regiments,

ten of the thirteen cavalry regiments,

and all three of the artillery regiments had

a chaplain attached at some point.

Clearly the state officials, the local military

committees, and the officers and men

themselves saw the presence of a chap-

lain as a positive addition to the units

and worked to fill the position which the

law allowed.21

17. L.W. Day, Story of the One

Hundred and First Ohio Infantry (Cleveland, 1894), 362.

Robert F. Bartlett, Roster of the

Ninety-Sixth Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1862-1865 (Columbus,

1895), 8. John K. Duke, History of

the Fifty-Third Regiment Ohio Volunteer Infantry, during the

War of the Rebellion 1861-1865 (Portsmouth, 1900), 5, 288. George W. Pepper, Under Three

Flags: The Story of My Life as

Preacher, Captain in the Army, Chaplain, Consul, with Speeches

and Interviews (Cincinnati, 1899), 83-93.

18. F.G. Backus to Governor David Tod, 6

November 1861, Governor David Tod Papers, OHS.

19. George W. Pepper, Personal

Reflections of Sherman's Campaigns in Georgia and the

Carolinas (Zanesville, 1866), 197-98. For a representative sample

of negative comments about

Civil War chaplains see Bell Irwin

Wiley. "'Holy Joes' of the Sixties: A Study of Civil War

Chaplains," Huntington Library

Quarterly, 16 (May, 1953), 287-304.

20. Shattuck, A Shield and a Hiding

Place, 54.

21. Most of the figures, with some minor

additions and alterations from other sources, are

drawn from the regimental rosters in

Whitelaw Reid, Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Her

Generals, and Soldiers, vol. 2 (Cincinnati, 1883).

10 OHIO HISTORY

This does not mean that the chaplain's

billet was always filled. A frequent

criticism of the system of army

chaplaincy was that there were just not enough

chaplains to go around. It was difficult

to get and keep men in the billets.

Nationally only about one-quarter of the

total chaplains were serving at any

given time. While there are no exact

figures for Ohio, there is no doubt that

there were gaping holes in the chaplain

corps' ranks throughout the war. Few

chaplains served their regiments from

"muster in" to "muster out."

Enlistments themselves varied from three

months to three years depending

on the time of the war when the regiment

was organized. Most Ohio regiments,

some 127, had three-year enlistments and

average service time for chaplains in

these regiments was fourteen months. The

twenty-nine regiments formed from

Ohio militia units in the summer of 1864

were called up for 100 days, and

chaplains in these regiments served for

that same amount of time. In the sixteen

regiments formed primarily in the last

year of the war (as the three-year regi-

ments' enlistments expired) chaplains

served an average of seven months. An

approximate average of all Ohio regiments

puts the chaplains present in their

regiments from a third to half of the

time. Some men did serve for long periods

with their regiments. John Poucher of

the 38th O.V.I. served the longest of any

Ohio chaplain, forty-four months. The

prize for shortest hitch as an army chap-

lain went to William G. Brown of the

69th Ohio who was mustered in on 15

April 1862 and mustered out the next

day. Service time for Ohio chaplains

based on the data gathered for this

study compares roughly with that of Roy J.

Honeywell, who lists the average Union

chaplain's service at twelve to fifteen

months, and with Gardner H. Shattuck who

lists the average Union chaplain as

serving eighteen months. These figures

do not include ten Ohio chaplains who

never accepted their commissions.22

Many regiments, especially the

three-year ones, had more than one chaplain

over the course of their history (though

never more than one at a time). Both

the 45th and the 73d O.V.I. had four different

men serve them as chaplains in

the course of their existence, and seven

chaplains saw service in two different

regiments (again not at the same time).

Chaplain Collier of the 34th Ohio had

his regiment amalgamated with the 36th,

while the other six chaplains resigned

from service and later joined other

regiments. In all, this writer found 237 Ohio

regimental chaplains who served at one

time or other during the war.23

In addition to these regimental

chaplains, Ohio appointed eight men as hos-

pital chaplains to minister to the

spiritual needs of the wounded. Congress had

22. Honeywell, Chaplains of the

United States Army, 121, and Shattuck, A Shield and a Hiding

Place, 63. Dates for service time were drawn primarily from

regimental rosters in Reid, Ohio in the

War, vol. 2.

23. Figures taken from Reid, Ohio in

the War, list 233 regimental chaplains. But research from

regimental histories has uncovered four

men not listed by Reid; only in two of these cases is infor-

mation listed as to actual dates of

commission and service.

Ohio Army Chaplains 11

authorized the appointment of hospital

chaplains in May 1862, and Ohio com-

missioned the first one the next month.24

The men served for an average of

thirty-two months, more than twice as

long as regimental chaplains, a disparity

which no doubt reflected the more

comfortable and safer living conditions that

these hospital chaplains experienced as

compared to the hardships of camp life

and the dangers of battle which

regimental chaplains faced.25

As the war dragged on and the glamour of

soldiering wore off, the number of

clergymen volunteering to be chaplains

declined. Thirteen of the forty-two

1864 militia regiments, who had only a

hundred-day obligation, went without

chaplains. In the one-year regiments

established by Ohio in 1864 and 1865, ten

out of twenty-five (forty percent) did

not have chaplains.26 Attrition was con-

siderable. About half of the Ohio

chaplains have the notation "resigned" in the

remarks section of the regimental roster

rather than "mustered out with unit" or

"honorable discharge." While

no chaplains from Ohio died in battle, at least

four chaplains died in service.27 Some

chaplains resigned their commissions to

accept positions as line officers.

William Stangel of the 9th O.V.I. accepted a

captaincy in that unit.28 Three

Ohio chaplains went on to accept commissions

as line officers in the United States

Colored Troops, and one, Harvey Proctor, a

captain in the 41st O.V.I. before he

became the unit's chaplain, went back to

the line as a major for a Black unit.29

On the national level, General Grant

selected John Eaton, chaplain of the

27th O.V.I., to be Superintendent of

Freedmen in the Department of the

Tennessee in November 1862. To strength-

en his authority in this endeavor Eaton

later resigned his chaplaincy and accept-

ed a line commission as a colonel in the

9th Louisiana Regiment of African

Descent, later the 63d U.S. Colored

Troops. In March 1865 Eaton was breveted

Brigadier General of Volunteers for his

work with the freedmen.30 Other chap-

lains resigned to take jobs with the

United States Sanitary Commission and the

United States Christian Commission.

These civilian organizations provided

employment similar to the military

chaplaincy but without as many hazards and

without the strictures of military

life.

24. Honeywell, Chaplains of the

United States Army, 105.

25. Reid, Ohio in the War, vol.

1,1013. Ohio also furnished three Black chaplains for regiments

in the United States Colored troops.

Although all three had been born in slave states (one had been

born a slave), they all listed their

residence as Ohio. Redkey, "Black Chaplaincy in the Union

Army," 350, Appendix.

26. Statistics are from regimental

rosters in Reid, Ohio in the War, vol. 2.

27. At least eleven Union chaplains were

killed in battle. William Fox, Regimental Losses in

the American Civil War 1861-1865 (Albany, NY, 1893), 43. Sixty-six Union chaplains died

in ser-

vice from all causes. Honeywell, Chaplains

of the United States Army, 120.

28. Stangel was court martialed and

cashiered about six months later for reviling the President

of the United States. Constantin, We

Were the Ninth, 115.

29. Reid, Ohio in the War, vol.

2, 259.

30. John Eaton, Grant, Lincoln, and

the Freedmen (New York, 1907), xvii, 5, 26, 109-17.

12 OHIO HISTORY

The chaplain's position was still in a

state of flux in many ways, including

the questions of rank and pay. The pay

and rations equivalent of a captain of

cavalry, to which Ohio regimental

chaplains were entitled, totalled $1,746 annu-

ally in 1861. The next year an

economizing Congress, concerned that chaplains

were making inordinate amounts compared

to their civilian counterparts,

reduced this to $1,433 and forage for

one horse; in 1864 this pay was upgraded

to include forage for two horses. This

put chaplains on a par with officers, but

technically they still had no rank. Not

until April 1864 were army chaplains

officially designated officers, as

"chaplain[s], without command," to rank after

surgeons, who ranked as majors.31

Not surprisingly in such an ambiguous

situation, chaplains were often con-

fused about their uniform. Some took

their cue from the pay designation and

put on shoulder straps of a cavalry

captain, while others even wore a sword.

The Army sought to end this confusion

with General Order 102 of 1861 which

called for chaplains to wear a plain

black frock coat with black buttons, black

trousers, and a black felt hat or forage

cap.32 In America's land and sea services

at this time a chaplain's uniform was

supposed to be distinctive enough to indi-

cate he was a member of the military but

not so military as to obscure his cleri-

cal function. The chaplain's uniform

reflected the societal ambivalence toward

the role of chaplains in the military

and their limbo status as officers. Ohio

chaplains were very much caught up in

this dilemma.

Chaplains were not appointed to

regiments in order to directly contribute to

the army's military effectiveness,

however much their presence may have indi-

rectly contributed by bolstering unit

morale. Instead, they were commissioned

to be pastors, to preach, to teach Bible

studies, to preside at the celebration of

the sacraments, to lead prayer at

military formations, to counsel the men, and to

evangelize the unconverted. This they

did. However, conditions dictated the

frequency and feasibility of ministry.

Charles McCabe, Methodist chaplain of

the 122d O.V.I., often held services

afternoon and evening, while other chap-

lains held services despite their

proximity to the battlefield. One Ohio soldier

in August 1864, for example, wrote:

"The Chaplain of the 98th O.V.I.

preached to the brigade today. An occasional

bullet whizzed over the audi-

ence."33 The war being

no respecter of the Sabbath, frequently there were no

Sunday services. For some chaplains the

unusual at times became the common-

place. Carl Bancroft, chaplain of the

133d O.V.I., married about twenty "con-

traband" couples (i.e., freed

slaves) in Virginia and then baptized their

31. Honeywell, Chaplains of the

United States Army, 118; Shattuck. A Shield and a Hiding

Place, 55.

32. Trumbull, War Memories, 2.

Honeywell, Chaplains of the United States Army, 110.

33. Honeywell, "Men of God in

Uniform," Civil War Times Illustrated, 6 (August, 1967), 32.

F.M. McAdams, Every-day Soldier Life

or A History of the One Hundred and Thirteenth Ohio

Volunteer Infantry (Columbus, 1884), 97.

|

Ohio Army Chaplains 13 |

|

|

|

children.34 Evangelism remained a priority, especially in extended camps where revivals were held, an enterprise in which the army chaplains cooperated with representatives of the United States Christian Commission and the American Tract Society. In general, chaplains performed their clerical duties and served as models for the men by "sharing the exposure and sufferings of the men" and "exerting a strong and wholesome moral influence."35 Caring for the wounded was also a major chaplain responsibility; one Baptist applicant from Ohio even listed his part-time prewar practice of medicine as one of his qualifications to serve as a regimental chaplain. Often the chaplain would station himself with the surgeon in a crude field hospital to assist in the care of the wounded. A.R. Howbert, one such chaplain, described his role in helping to dress wounds and caring for the men's physical needs as they lay in the hospital after a battle in Virginia. Joseph Morris, chaplain of the 113th

34. S.M. Sherman, History of the 133rd Regiment, O. V.I. (Columbus, 1896), 122. 35. F.H. Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio Infantry: A History of the Organization and Services of That Regiment in the War of the Rebellion (Cleveland, 1876), 45. |

14 OHIO

HISTORY

O.V.I., found himself in charge of the

spiritual care of 800 men in the

Fourteenth Corps hospital. His job, he

said, was "to aid, comfort, and instruct

the living, and bury the dead."36

Chaplain Aaron D. Morton, 105th O.V.I.,

became ill and was sent to the hospital

in Chattanooga along with other sick men

from the regiment; upon his recovery

Morton was retained for duty by the hospi-

tal. While perhaps necessary given the

exigencies of the time, borrowing regimen-

tal chaplains only reduced further the

ratio of chaplains to troops in the field.37

Ohio chaplains in aiding the wounded

often cooperated with the United

States Sanitary Commission, a wartime

organization dedicated to improving

camp and hospital hygiene as well as the

spiritual well-being of the soldiers.

After his stint as chaplain for the 84th

O.V.I., Pastor Howbert was sent by

Governors David Tod and John Brough to

report on the conditions of hospital-

ized Ohio soldiers and to assist in

providing for their needs. In doing so

Howbert worked with both the U.S.

Sanitary Commission and the U.S.

Christian Commission.38

While chaplains tried to foster a spirit

of cooperation with such agencies,

there were territorial battles that arose

from separate and outside organizations

involved in work that overlapped that

done by the regimental chaplains. The

same can be said of the chaplains'

relationships with other staff corps officers,

especially the medical corps. Surgeons

often viewed chaplains as useless or

worse, and chaplains returned the

compliment by branding surgeons as callous,

lazy, or disdainful of the spiritual

side of life. Chaplain Stevenson of the 78th

O.V.I. said it was "a rare thing

for surgeons and chaplains to agree."39

Chaplains in the Civil War also often

found themselves saddled either will-

ingly or unwillingly with a host of

non-spiritual duties. These duties were usu-

ally in some fashion connected with

morale. Frequently the chaplain was the

regimental postmaster, and his duties

included distributing religious books and

tracts. William W. Lyle, chaplain of the

11th O.V.I., acquired a sizable library

of 400 such volumes.40 At

other times Ohio chaplains functioned almost as

bankers, taking money home to the

families of men who did not trust the mail.

Chaplain Lyman Ames went home to

distribute money to families of men in

the 29th O.V.I. in October 1864, and

Chaplain Lyle regularly went on leave to

36. G. Cyrus Sedwick to Governor David

Tod, 29 July 1862, Governor David Tod Papers,

OHS. A.R. Howbert, Reminiscences of

the War (n.p., 1888), 64. McAdams, Every-day Soldier Life,

389.

37. Albion W. Tourgee, The Story of a

Thousand: Being a History of the Service of the 105th

Ohio Volunteer Infantry in the War

for the Union from August 21, 1862 to June 6, 1865 (Buffalo,

1896), 390. Tourgee is perhaps best

known for his Reconstruction novel A Fool's Errand.

38. Howbert, Reminiscences, 1-2,31-32,70.

39. Thomas M. Stevenson, History of

the 78th O.V.V.I. (Zanesville, 1865), 100. Quoted in

Rollin W. Quimby, "The Chaplain's

Predicament," Civil War History, 8 (March, 1962), 36.

40. Armstrong, "The Organization,

Function and Contribution of the Chaplaincy of the United

States Army," 63.

Ohio Army Chaplains 15

do the same for the soldiers of his

unit.41 Additionally, it was not unusual for

the chaplain to organize and manage the

officers' mess. Other chaplains pro-

vided instruction for the soldiers,

ranging from basic reading and writing skills

to college subjects. Taking it a step

further, Chaplain Charles McCabe of the

122d Ohio, while confined at Libby

Prison in Richmond, organized a "univer-

sity" in conjunction with other

educated Union prisoners.42 Almost anything

that chaplains considered wholesome or

beneficial for morale was liable to

come under their purview. Chaplain James

Gardner of the 17th O.V.I., joining

in the troops' love of athletics, took

part in a unit football game and allegedly

"outran every man in the

regiment."43 Finally, chaplains even functioned as de

facto social workers for the freedmen who increasingly

flocked to the Union

armies. John Eaton's pioneering work and

conversion to line officer have

already been mentioned, and many of his

policies and methods were later

adopted by the postwar Freedmen's

Bureau.

In many areas of this study the outline

of what today's military chaplain does

is recognizable and familiar. The

chaplain of our time is primarily a spiritual

leader who, outside of religious

functions, is usually involved only in collateral

duties of unit morale. There was one

aspect of Civil War chaplaincy, however,

that differs markedly from our own time:

the involvement of chaplains, normal-

ly noncombatants, in operational duties

that directly made them combatants.

No clear consensus existed on this issue

among Ohio's regimental chaplains

themselves, certainly not in the early

years of the war, and the law itself was

not yet clear. Even the duties of

chaplains were not plainly delineated, as the

law did not forbid them to participate

in combat. (For that matter, there was no

draft exemption for pastors.)44 The

government could legally put clergymen in

the ranks as regular soldiers. And, as

mentioned earlier, many volunteered on

their own to fight in the ranks.

Chaplains in the Civil War could be

found in virtually all levels of involve-

ment in combatant roles. The extent of

chaplain participation varied enormously

depending upon the disposition of

regimental commanders, many of whom

were themselves primarily amateurs at

officership and the conduct of war and

consequently desirous of using all the

talent under their command. Some chap-

41. In explanation for one of Chaplain

Lyle's leave requests his Commanding Officer, Colonel

P.P. Lane, wrote that "Chaplain

Lyle has something over twenty five thousand dollars $25,000 in

his hands for distribution among the

families and friends of the soldiers of this reg't, and it has been

the custom of the regiment for the past

eighteen months to deposit all surplus funds with him to be

sent to Ohio, and he has acted as financial

and general business agent for the reg't." Service

Record, Files of the Adjutant General's

Office, Record Group 94, National Archives, quoted by

Armstrong, "The Organization,

Function and Contribution of the Chaplaincy of the United States

Army," 64-66. Armstrong also notes

that numerous other similar requests for such leave by chap-

lains were regularly granted.

42. Honeywell, "Men of God in

Uniform," 33.

43. C.T. DeVelling, History of the Seventeenth Regiment, O.V.I. (Zanesville, 1889), 72.

44. Shattuck, A Shield and a Hiding Place, 56.

16 OHIO HISTORY

lains were more willing to step into the

combat role than others, a decision

which was based on their own religious

traditions and personal attitudes. Ohio

army chaplains exemplified this diverse

approach. James Garfield, a religious

man himself, wrote his wife that

Chaplain Harry Jones was routinely present at

the regimental "council of

war" and that he was a "privileged character in all

our deliberations."45 Chaplain

Dean Wright acted as aide-de-camp for General

Tyler at the battle of Port Republic,

Virginia, in June 1862, while Frederick

Brown, who preceded Wright in the post

of chaplain in the 7th O.V.I., "in addi-

tion to his duties as chaplain ...

rendered important service as bearer of unwrit-

ten dispatches from Col. Tyler to Gen.

Cox, going alone across the country

occupied by guerrillas and

bushwackers."46 Jacob Cox himself describes

Brown on this daring cross-country ride

as "disguised as a mountaineer in

homespun clothing, his fine features

shaded by a slouch hat."47 In this instance

Chaplain Brown was clearly more of a spy

than a preacher of the Gospel. Many

chaplains stood in the line of battle

even if they did not carry rifles. Harrison

Jones, acting as Colonel James

Garfield's aide-de-camp at the battle at Middle

Creek, Kentucky, stood beside his

colonel amid what Garfield described as a

hail of bullets that "cut the

twiggs above us and splintered the rock on which

we stood."48

It was but a short step to full

combatant. The chaplain had only to pick up a

gun, and there were chaplains not averse

to doing so. Both Union and

Confederate chaplains debated the issue,

particularly regarding the status of

chaplains as prisoners of war. Chaplain

McCabe was initially scheduled to be

released following his capture while

tending Union wounded, but General

Jubal Early countermanded the order and

made McCabe a prisoner. The issue

was largely settled in July of 1862 when

both the Confederate and Union gov-

ernments issued orders that henceforth

all chaplains would not be held prison-

ers of war. This policy held for all but

one three-month period of time in 1863

when there was a dispute over other

prisoner issues.49

This ruling did not settle the issue,

however, as chaplains continued to follow

their individual consciences. As we have

seen, many ministers joined the army

45. James A. Garfield to Lucretia Galfield, 13

January 1862, Garfield Papers, reel 5.

46. Lawrence Wilson, ed., Itinerary

of the Seventh Ohio Volunteer Infantry 1861-1864 (New

York, 1907), 522.

47. Cox, Military Reminiscences, 85.

48. James A. Garfield to Lucretia

Garfield, 13 January 1862, Garfield Papers, reel 5. For more

readable and convenient access to

Garfield's references to his regimental chaplain see Frederick D.

Williams, The Wild Life in the Army:

Civil War Letters of James A. Garfield (East Lansing, 1964).

My decipherment of the future

President's battlefield scrawl in this particular quotation differs

slightly from Williams version.

49. Honeywell, "Men of God in

Uniform," 33. General Early addressed the Chaplain: "So

you're a preacher, are you? You

preachers started this war and have kept it up with your cries of

'On to Richmond,' so on to Richmond you

shall go." As mentioned previously, McCabe ended up

in Libbey Prison. Honeywell, Chaplains

of the United States Army, 97-98.

Ohio Army Chaplains 17

to serve as line officers or enlisted

personnel. For ninety-seven Federal chap-

lains who had prior experience as

combatants, it must have been natural to pick

up a rifle and join the fray. Confusions

about uniforms, rank, and combatant

status made it easy to cross the line

from noncombatant to combatant. One such

case was Russel B. Bennett of the 32d

O.V.I. who, at the battle of Atlanta in

July 1864, "carried his musket and

fought all day in the ranks."50 Doubtless

Bennett saw his role as little different

than that of Granville Moody, the "fight-

ing parson," who as a line officer

commanded the 74th O.V.I. and who, like

Bennett, was also a Methodist minister.

The Civil War was a transitional period

for chaplains. The prevailing view as

strengthened by law on both sides of the

Mason-Dixon line was that chaplains

should not be combatants. The

experiences of the war and the thinking of most

army chaplains tended to reinforce this

outlook. All that took time, however,

and there were Union chaplains who were

commended for their battlefield

exploits. In fact, three Union chaplains

were later awarded the Medal of Honor,

two for carrying wounded men to safety,

one for actually engaging in combat.51

But overall, the tide of thinking flowed

generally toward a noncombatant role

for army chaplains.

Ohio's regimental and hospital chaplains

proved typical of the national expe-

rience during this watershed for the

institution of military chaplaincy. The scale

of the war itself brought many changes

to the office of the chaplain and rede-

fined to a large degree the duties of

chaplains. The prewar conditions of the

frontier army with its scattered and

small number of chaplains provided no real

precedent or need for regimental

chaplains. The scanty and undefined qualifica-

tions necessary for becoming a chaplain

and the crush of mobilization pressures

at the beginning of the war produced

army chaplains of uneven quality. Some

were well qualified; some were not.

Which is to say that standards of profes-

sionalism were not much better than

those of their line counterparts.

Gradually the Army culled the initial

heterogeneous collection of chaplains

and ordered regimental commanders to

discharge unsuitable men like previous-

ly mentioned Wilhelm Stangel of the 9th

O.V.I. Newly appointed chaplains had

to be properly ordained and their

endorsing church had to have a minimum

amount of ecclesiastical integrity; the

letters of recommendation and the prof-

fers of service which prospective Ohio

chaplains sent to the Ohio governors

routinely reflected both of these

professional standards. This movement toward

greater involvement of the churches in

the selection of chaplains, and the deci-

sion to accept only college and

seminary-trained individuals, which is the stan-

dard today but which was not officially

binding until the twentieth century,

50. Fox, Regimental Losses, 44.

51. Honeywell, "Men of God in

Uniform," 37.

18 OHIO HISTORY

became accepted practice because of the

problems encountered in the early

years of the Civil War.

What it meant to be a chaplain was

placed in sharper focus as a result of the

war. When Ohio's chaplains signed their

commissions, they were not, as we

have seen, sure what uniform to wear,

how they fit into the military rank struc-

ture, or exactly what their duties were.

Confusion reigned until the government

and the chaplains themselves could sort

out these issues of pay, uniform, rank

and collateral duties. In no area was

this more evident than the issue of how

militarily active a chaplain should be

on the battlefield. The reader has seen

how Ohio chaplains served in a variety

of roles from aide-de-camp to dispatch

rider to rifleman on the skirmish line.

That there is only one direct account of

an Ohio chaplain firing a rifle in

battle over a four-year period seems to indi-

cate that most chaplains did not follow

such a practice. Ohio chaplains mainly

did what they did best--preach, teach,

counsel, evangelize, and administer the

sacraments. Because the exigencies of

war often made these activities impossi-

ble, chaplains sought to help out

wherever possible in tasks that needed doing

and which supported the morale of the

men. Chaplains were there to fight their

own kind of war, namely "to stay

... the evil influences incident to a soldiers

life" and serve in a ministry of

presence by sharing "the exposure and suffering

of the men."52 Ohio

chaplains played a major part in the professionalization

and definition of American military

chaplaincy, a role much more contempo-

rary to us in description and scope than

it was before the war began.

52. Day, Story of the 101st, 123.

Mason, The Forty-Second, 45.

Appendix: Statistical Data for Ohio

Civil War Chaplains

Analysis by Regimental Type

192 Infantry Regiments

162 had chaplains assigned (84 percent)

30 had no chaplains assigned (16

percent)

13 Cavalry Regiments

10 had chaplains assigned (77 percent)

3 had no chaplains assigned (23 percent)

|

Ohio Army Chaplains 19

3 Artillery Regiments 3 had chaplains assigned (100 percent) 0 had no chaplains assigned (0 percent)

Total of 208 Ohio regiments organized 175 had chaplains (84 percent) 33 had no chaplain assigned (16 percent)

Analysis of Ohio Regimental and Hospital Chaplains

237 regimental chaplains (including ten who did not accept commissions)

8 hospital chaplains

Mortality Figures for Ohio Regimental Chaplains

4 chaplains died on active service (none apparently in action)

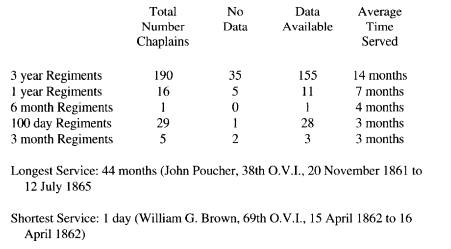

Duration of Service of Ohio Regimental Chaplains |

|

|

RICHARD M. BUDD

Ohio Army Chaplains and the

Professionalization of Military

Chaplaincy in the Civil War

While the study of military chaplains is

fascinating if only because of the

apparent incongruity of peacemakers

serving in an institution of warmakers,

military chaplaincy during the American

Civil War is of particular interest

because of the insight it offers into

the development of the office of chaplain.

While chaplains had been appointed by

Congress as far back as 1775, their role

and status were not clearly defined, and

their qualifications for appointments

were not well established. The wartime

appointment of chaplains on such an

unprecedented and massive scale raised a

host of issues concerning the role of

the chaplain in war, his status as a

participant in battle, and the evolution of

chaplaincy as a profession. Evidence

suggests that the Civil War chaplains

from Ohio played a typical and

substantial role in the professionalization and

definition of American military

chaplaincy.

Civil War chaplaincy has been studied

from Union and Confederate stand-

points, from the viewpoint of particular

religious denominations, and from the

experiences of individual chaplains. To

date no one has studied the subject

from the perspective of one state's

experience. Ohio appointed approximately

one-tenth of the 2,500 Union army

chaplains who served in the Civil War.1 By

concentrating closely on the experience

of these approximately 240 Ohio men

and then generally comparing their

experiences with those of chaplains in other

northern states, it is possible to

produce a reasonably accurate and typical pic-

ture of what chaplaincy was like in the

Federal armies from 1861 to 1865.2

Richard M. Budd is a Ph.D. candidate in

military history at The Ohio State University.

1. Herman A. Norton, Struggling for

Recognition: The United States Army Chaplaincy, 1791-

1865. History of the United States Army Chaplaincy, vol. 2

(Washington, D.C., 1977), 108.

2. For a comprehensive view of Union

chaplains see Warren Bruce Armstrong, "The

Organization, Function, and Contribution

of the Chaplaincy of the United States Army, 1861-

1865" (Ph.D. diss., University of

Michigan, 1964). For the official accounts see Roy J. Honeywell,

Chaplains of the United States Army (Washington, D.C., 1958) and Norton, Struggling for

Recognition. For a recent listing of articles on Union chaplains see

Edmund S. Redkey, "Black

Chaplains in the Union Army," Civil

War History, 33 (December, 1987), 332-50.

For a detailed examination of

Confederate army chaplaincy, which offers many interesting par-

allels to the Union road toward

professionalization, see Herman A. Norton, "The Organization and

Function of the Confederate Military

Chaplaincy, 1861-1865" (Ph.D. diss., Vanderbuilt University,

(614) 297-2300