Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

MARK PITCAVAGE

"Burthened in Defence of our Rights":

Opposition to Military Service in Ohio

During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 has long been famous as

a war to which substantial op-

position existed in the United States.

The nearness of the Congressional vote

over the declaration of war, the refusal

of several New England states to pro-

vide militia for the invasion of Canada,

and the Hartford Convention in 1814

are all notable examples of the degree

to which the nation divided over the is-

sue of war with Great Britain.

Unfortunately, these incidents have led

historians to concentrate on the po-

litical opposition to the War of 1812,

viewing it as the natural outgrowth of

the Federalist-Republican battles of the

early national period. Because

Federalists so vocally opposed the war,

they receive attention at the expense

of other groups, and New England, that

bastion of Federalism, receives atten-

tion at the expense of the rest of the

country. The danger of concentrating

solely on political issues is that the

effects of the war itself on American

communities-and thus public

opinion-might be overlooked.1

This article examines the opposition to

military service that arose in Ohio

during the course of the War of 1812,

the nature of that opposition, and its ef-

fects. Along with Kentucky and

Tennessee, Ohio (dominated by Jeffersonian

Republicans) was one of the western

states which cried out for war in 1811

and 1812, and whose citizens flocked to

the colors when war appeared immi-

nent. As the war dragged on, however,

Ohioans became less enthusiastic

Mark Pitcavage would like to thank Allan

R. Millett, Joan E. Cashin, Mark Grimsley, and

Virginia Boynton for their advice and

assistance in writing this article. Any errors are his own.

1. Of the standard scholarly histories

of the war, the two which provide most coverage of

opposition to the war are Donald R.

Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict, (Urbana,

Ill, 1989), and J. C. A. Stagg, Mr.

Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the

Early American Republic, 1783-1830, (Princeton, N.J., 1983). John K. Mahon, The War of

1812, (Gainesville, Fla, 1972), provides some information.

Recent specific studies of opposi-

tion include Edward Bryan,

"Patterns of Dissent: Vermont's Opposition to the War of 1812,"

Vermont History, 40 (Winter 1972), 10-27; Sarah M. Lemmon, "Dissent

in North Carolina

During the War of 1812," North

Carolina Historical Review, 49 (Spring 1972), 103-18: Myron

F. Wehtje, "Opposition in Virginia

to the War of 1812," Virginia Magazine of History, 78

(January 1970), 65-86; and Ellen P.

Hoffman, "Unnecessary, Unjustified and Ruinous: Anti-

war Rhetoric in Massachusetts Federalist

Newspapers" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Massachusetts, 1984).

Burthened in Defense of our

Rights

143

about performing the military service

required to conduct the war. Opposition

to service in the militia took three

forms. The first substantial opposition

arose in communities along the frontier

that feared Indian attack and the con-

sequences of sending their men away from

their homes and families. The

second type of opposition came from

communities and individuals that felt

they were bearing a greater part of the

burden of the war than their neighbors.

The third type, arising only late in the

war, took the form of a general war-

weariness characterized by considerable

desertions and mass refusals to serve.

It was only in this last phase of

opposition that Federalist propaganda had any

discernible impact.2

The Exposed Frontier

The initial response on the part of

Ohioans to military service was largely

positive. Ohio Governor Return Jonathan

Meigs and Michigan Territorial

Governor William Hull, commissioned a

major general in the U.S. Army,

had few problems assembling 1,200 troops

in the spring and summer of 1812

to march to Detroit. Indeed, a larger

army could have been raised, but was not

2. As militia historian Jerry Cooper has

noted, until recently most scholars who have exam-

ined the militia have followed the lead

of nineteenth century Army officer Emory Upton,

whose The Military Policy of the

United States (Washington, D.C., 1904) condemned the role

played in wartime by militia or

volunteers. These studies tend to focus on wartime use of the

militia and federal mobilization

efforts, and emphasize the value of the Regular Army as op-

posed to the poor performance of militia

units; see Cooper, The Militia and the National Guard

in America Since Colonial Times: A

Research Guide (Westport, Conn, 1993),

13-17, 51-56.

While historians of colonial America

have examined the militia in a variety of social, religious,

economic, and ideological contexts,

those studying the militia of the early republic have gen-

erally followed Uptonian themes. Thus

Richard Kohn examines the failure of efforts to give

the federal government greater control

over the militia in Eagle and Sword: The Beginnings of

the Military Establishment in America

(New York, 1975), 73-90, 128-38, and

Lawrence

Delbert Cress explains the same failure

as a result of republican ideology in Citizens in Arms:

The Army and the Militia in American

Society to the War of 1812 (Chapel

Hill, N.C., 1982),

passim. John K. Mahon, in his History

of the Militia and the National Guard (New York, 1983),

provides the most balanced overall

depiction of the militia, including information on the state

level, but in The American Militia:

Decade of Decision, 1789-1800 (Jacksonville, Fla., 1960),

even he concentrates on the issue of

greater federal control over the militia. More understand-

ing of the social background of the

militia is Marcus Cunliffe, Soldiers and Civilians: The

Martial Spirit in America, 1775-1865 (New York, 1973), 177-260. A satisfactory recent

overview of the militia system is

Kenneth Otis McCreedy, "Palladium of Liberty: The

American Militia System, 1815-1861"

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of California,

Berkeley, 1991). Specific studies of the

militia in the period 1789-1815 are quite rare, but see

Martin K. Gordon, "The Militia of

the District of Columbia, 1790-1815" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, George Washington

University, 1975); Jean M. Flynn, "South Carolina's

Compliance with the Militia Act of

1792," South Carolina Historical Magazine, 69 (January,

1968), 26-43; John K. Mahon, "The

Citizen Soldier in National Defense, 1789-1815,"

(unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of California at Los Angeles, 1950); and Mark

Pitcavage, "Ropes of Sand:

Territorial Militias, 1801-12," Journal of the Early Republic, 31

(Winter, 1993), 481-500.

144 OHIO HISTORY

because it could not be supplied.

Ohioans were not just being patriotic, they

were being practical: a war against the

British, many assumed, would in turn

reduce the pressures Indians placed on

white settlers.3

Settlers' fears of Indians also provided

the first significant opposition to

military service in Ohio in the summer

and fall of 1812. People living along

the ill-defined

"frontier"-which ran from southwest Ohio north by northeast

towards Lake Erie-viewed with alarm the

prospect of stripping the frontier

of men capable of bearing arms by

sending them to Canada. Not surpris-

ingly, they wanted the state and

national governments to provide more protec-

tion, rather than less. Benjamin

Mortimer, minister to a mixed community

of Indians and whites, observed to

Governor Meigs that while fear of Indians

was one of the excuses used by those who

would rather stay at home, "a still

greater number are in fact under much

anxiety on this head, and represent to

themselves, that if during their

absence, an Indian war should break out ...

their families would be in great danger

of their lives."4

Similar sentiments came from a group of

Richland County settlers, self-

described "young enterprising

people who have brought our helpless families

to the gloomy wild." These families

would be left defenseless by a calling-

up of the militia, "exposed to the

brutal disposition of the merciless savages."

While the settlers realized their

services were needed, they felt that "yet the

calls of our tender wives and infants

ring louder in our ears than the calls of

consulted authority." A second

petition from Richland County asked for arms

and for release from having to perform

military service outside the county.5

Some settlers believed their work in

taming the frontier was service enough

to the state. Others added economic

arguments against military service. One

group of petitioners, for example,

hoping for release from militia duty, noted

that they were the economic mainstays of

both their families and of the fron-

tier community-families would suffer and

crops would fail if they were

called away. This would result in

"very flourishing townships in this

county" becoming entirely depopulated,

and fertile fields returning to a howl-

ing wilderness. The Indian threat would

increase the exodus, because the set-

tlers called out to militia service

would take most firearms from the commu-

nity. With the remaining settlers

without arms or ammunition, the petition-

ers asked, "what safety or what

refuge they can have other than to take to their

heals [sic] and clear out as fast

as possible ...."6

3. See Stagg, Mr. Madison's War, 193-200,

on the raising of Hull's army. For more infor-

mation on the effect that poor relations

with Native Americans had on Ohioans, see James E.

Pallet, The Indian Menace in the Old

Northwest, 1809-12, (Columbus, 1959), passim.

4. Benjamin Mortimer to Return J. Meigs,

August 8, 1812, Reel 1, Frames 436-440, Return J.

Meigs, Jr. Papers, Microfilm Edition,

Ohio Historical Society.

5. Citizens of Richland county to Return

J. Meigs, August 17, 1812, September 4, 1812, Reel

1, Frames 509-10, and Reel 2, Frames

33-34, Ibid.

6. Petition to Return J. Meigs, June 17,

1812 (damaged), Reel 1, Frame 330, Ibid. In gen-

|

Burthened in Defense of our Rights 145 |

|

|

|

The news of Hull's shameful surrender of Detroit on August 16, 1812, which reached Ohio some days later, only increased the clamor for protection of the frontier, as settlers envisioned a horde of savage Indians descending upon their communities. Governor Meigs ordered frontier militia generals to take defensive measures, while armed citizens rushed to the frontiers in what one newspaper described as a "spontaneous and rapid" movement. Militia generals not on the frontier itself ordered units held in readiness to march in case of emergency. One such general, John S. Gano, also argued that no militia units should be sent to join the army, so that the frontier could be protected. The surrender of General James Winchester's Northwestern Army to the British in January 1813 only increased the concern about Indian at- tacks.7

eral, spelling and grammar have not been altered in this article, although in one or two in- stances slight punctuation has been added to enhance comprehension. 7. Ohio Centinel, September 23, 1812; Major General John S. Gano to Major Samuel McHenry, September 16, 1812, in "Selections from the Gano Papers, 1,"Quarterly Publication of the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, 15 (January-June, 1920), 1-105. |

146 OHIO

HISTORY

The pressure to protect the frontier

eventually led Meigs to adopt a general

policy of exempting frontier settlements

from militia drafts by allowing mili-

tia officers to except them from filling

divisional quotas. Exactly when this

practice began is not clear. One militia

general in 1815 claimed that Meigs

issued a general order in 1812 to that

effect. However, a letter to Meigs in

April 1813 which complained that

residents of Piqua, Ohio, were drafted to

serve 35 miles away (leaving their own

settlement exposed), and called for the

governor to exempt from draft militia

companies bordering on the frontier,

suggests such a policy was not yet in

place. It is likely that the practice was

more informal than formal, although the

state legislature, in its revision of

the militia laws passed February 9,

1813, gave the governor authority to ex-

empt the militia from frontier

settlements from being called into service and

to make any further provisions thought

necessary for the defense of the fron-

tier.8

Through 1813 and 1814, most frontier

settlements were not called upon to

fill militia quotas for service away

from their communities, but Thomas

Worthington questioned the practice when

he became governor in late 1814.

Concerned about the defense of the

frontiers of Ohio (as well as Indiana and

Illinois), Worthington proposed to

Secretary of War James Monroe in

November 1814 a plan of defense arguing

for, among other things, the divi-

sion of frontier militia regiments into

six classes, each to serve as minutemen

(militia ready for immediate call-up)

for two months, to meet every week for

drill, but to be exempt from all other

militia duties. This measure, he argued,

Ohio had already substantially adopted.

Actually, the state had adopted no

such measures, though Worthington

desired them. In any event, the federal

government did not adopt the suggestions

before the war's end.9

In early 1815 Worthington ended the

policy of absolutely exempting fron-

tier militia units from duty outside

their settlements, because he believed the

exemption promoted a decay of the

militia in those areas. He could obtain

relatively little information about the

condition of the frontier militia, be-

8. Colonel John Moore to Thomas

Worthington, February 27, 1815, Reel 9, Frames 711-717,

Thomas Worthington Papers, Microfilm

Edition, OHS; John Johnston to Meigs, April 8, 1813,

Reel 3, Frames 325-326, RJM Papers, OHS;

Chapter 43, Section 39, "An Act for Disciplining

the Militia," February 9, 1813, Acts

Passed at the First Session of the Eleventh General

Assembly of the State of Ohio. Later complaints by Johnston indicate that the problem

existed-

at least near Piqua-through the end of

1814, and also give further evidence of the informality

of the practice. One militia general

drew an exemption line through his division's territory, ex-

empting all outside of it. However, the

officer's successor allowed no exemptions for militia

drafts. See Johnston to Othniel Looker,

May 12, 1814 and October 7, 1814, Reel 1, Frames 69-

71 and 229-231, Othniel Looker Papers,

Microfilm Edition, OHS.

9. Worthington to James Monroe, November

21, 1814, in Journal of the House of

Representatives of the State of Ohio,

Thirteenth General Assembly, 116-18;

Thomas

Worthington to Isaac Van Horn, February

4, 1815, Reel 1, Frame 23, Letters from the

Executive of Ohio, Executive Letterbooks Microfilm Edition (hereafter

abbreviated as LEO),

OHS.

Burthened in Defense of our

Rights 147

cause militia returns were infrequent at

this late stage of the conflict, and be-

cause those few returns available were

in the possession of his adjutant gen-

eral, who lived in Zanesville, a

considerable distance from the capital city of

Chillicothe. Worthington eventually sent

a subordinate around to the various

regiments to ascertain their condition

and the number of weapons they had,

with a view to reorganizing the frontier

defenses (and in February appointed a

new adjutant general).10

Worthington's plan was essentially the

one that he had suggested to

Monroe was already in operation: "I

think it probable, I shall exempt all the

Battalions, immediately on the frontier

. . . and organize them into minute

men, for their own immediate

defence." However, the news of peace took

away much of the necessity for such

actions. As a result, many frontier

communities successfully avoided most of

the militia duty with which other

parts of the states had to comply.1l

An Equal Burden

While frontier communities protested the

calling away of their men for mil-

itary service, people elsewhere in Ohio

protested that they were being called

upon to provide an unequal share of

military manpower. Like the settlers on

the frontier, these protesters were

generally in agreement about the justness of

the war, and represented themselves as

being willing to serve. But they cast

envious eyes at other communities whom

they felt were called upon less of-

ten for troops.

Because Ohio had for some time been on a

hostile frontier, where the pos-

sibility of military service was

considerable, its lawmakers had designed the

state's militia laws in such a way as to

spread the burden of such service as

equally as possible among the

population. Unlike many other states, Ohio's

militia laws dictated two methods of

military organization that both comple-

mented and contradicted each other. The

militia throughout the state were di-

vided into standard military units of

divisions, brigades, regiments, battalions,

and companies. But except for the

hypothetical case of a general invasion of

Ohio, in which the whole militia could

be called out to defend the state, the

divisions in practice existed as

administrative units. The second form of or-

ganization occurred at the company

level. According to law, militia captains

each divided their companies into eight

distinct groups or classes. When the

governor or high-ranking officers acting

on his orders ordered a militia draft,

10. Colonel John Moore to Thomas

Worthington, February 27, 1815, Reel 9, Frames 711-

717, Worthington Papers, OHS.

11. Thomas Worthington to John Johnston,

February 18, 1815, Reel 1, Frames 29-30, LEO,

OHS; Chapter 54, Section 43, "An

Act for Organizing and Disciplining the Militia," February

14, 1815, Acts Passed, Thirteenth

General Assembly.

148 OHIO HISTORY

the first class of each affected company

would be ordered into service. The

next tour of duty required would fall

upon members of the second class, and

so forth. The only exception to the

principle that every ablebodied man

would perform his share of the duty was

a provision that allowed men to pro-

cure substitutes for themselves.12

Not surprisingly, it proved impossible

in practice to insure an equitable dis-

tribution of military service, which

caused resentment among communities

that perceived others were not

performing their fair share. Conscientious ob-

jectors-primarily Quakers and

Shakers-formed the most visible target for

resentment. Many other states had long

since listed members of the two sects

among their standard exemptions to

military service, but Ohio had not done

so, although the 1809 militia law did

allow those "conscientiously scrupu-

lous" of bearing arms to avoid

service by purchasing a certificate for $3.50.

But the state legislature denied the

petition of Shakers from Warren County

who wanted to perform work on the

highways instead of doing military duty

in 1811. A legislative committee

reported that it would be "inauspicious" to

interfere with the militia system during

a time of crisis; that granting exemp-

tions to Shakers might cause Quakers,

Mennonites, and other denominations

to claim exemptions as well; and that,

perhaps most importantly, "even the

present applicants themselves in another

memorial . . . spurn the thought of

having any distinction made between them

and our other citizens."13

The outbreak of war increased the

determination among Ohioans that

Shakers and Quakers should do their fair

share. The 1809 provision for ex-

empting conscientious objectors for a

fee fell by the wayside in the revisions

to the militia laws over the winter of

1812-13. An amendment in the House

to exclude all conscientious objectors

from duty failed by a vote of forty-

seven to three. A committee on Quakers

the same day recommended no ex-

emptions, even partial, from militia

duty for the conscientiously scrupulous,

because it was "improper at the

present momentous crisis to lessen the effec-

tive force of the state." The

committee must have known, of course, that a

force of Quakers was hardly an effective

force (officers as early as August

1812 reported that Quakers would not

serve if called on to do so), but they

could not easily let some groups avoid

military service while others did their

duty. "The Quakers are flanking

about us, pleading for exceptions," com-

plained one lawmaker who wished that

Congress would take the problem of

exemptions out of the hands of the

states. The legislature held firm, however:

no conscientious objectors were excused

by law from duty or paying fines for

the remainder of the war.14

12. Chapter 1, Sections 30-40, "An

Act for Disciplining the Militia," February 14, 1809, Acts

Passed, Seventh General Assembly.

13. Ohio House Journal, Eleventh

General Assembly, January 11, 1812, 175.

14. Ohio House Journal, Eleventh

General Assembly, February 2, 1813, 224-29; Colonel

Burthened in Defense of our

Rights

149

After the initial outbreak of support

for the war, the burden of military ser-

vice was not borne very

enthusiastically. Although the officers of his de-

tachment were cheerful, wrote one

militia general to his superior in

September 1812, "the privates are

like all other militia, uneasy and many de-

sirous of returning home and it will be

with the greatest difficulty that they

can be induced satisfactorily to remain

in the service two weeks." A year

later, after American victories leading

to the recapture of Detroit in September

1813 and the Battle of the Thames in

October, respectively, a Zanesville,

Ohio, newspaper congratulated its

readers: "How cheering to the wife and

children of those militia now in

service, to know that the dangers of battle are

no longer to be dreaded: and to those

who fearful that another draft might

soon call them from their homes . . .

what a pleasing reflection that the ne-

cessity for militia will be daily

decreasing." Added to the dangers of battle, in

the minds of the militia, were the

hazards of camp life, the economic hard-

ships caused by leaving home, and the

long delays in getting paid for their

services (see below).15

Those communities protesting military

service on the grounds of being

asked to perform more than their share

took pains to demonstrate their patrio-

tism, the amount of service they had

performed, and their willingness to serve

in the future. Junior officers of one

regiment that had not filled its quota of

militia informed their divisional

commander in August 1812 that they had al-

ready volunteered one company, despite

the fact that most of the men had

families to provide for, and had that

very day volunteered a large number to go

on yet another expedition. In fact,

"in consequence of our turning out so

large a proportion . . . other regiments

have not been burthened in defence of

our rights as we have done." The

men were aware of the duty they owed their

"felow[sic] creatures and our

families and our own persons in exercising a

laudable zeal in defense of our country

. . . to sacrifice a full proportion of

time and property to the service of our

country. . ." However, they believed

"as a regiment" they had already

offered as much as circumstances permitted,

and so wanted relief from the latest

draft. A similar protest from another unit

in the same division stressed that the

militiamen had served their country and

beseeched their general to "grant

relief by appointing to us only our share of

John Hindman to Major General Elijah

Wadsworth, August 1, 1812, MSS 3133, War of 1812

Collection, Western Reserve Historical

Society; Duncan McArthur to Thomas Worthington,

January 20, 1813, Thomas Worthington

and the War of 1812: Vol. III of the Document

Transcriptions of the War of 1812 in

the Northwest, (Columbus, 1957), 151.

The refusal to ex-

empt Quakers may also have had roots in

the fact that those Quakers who were politically ac-

tive tended to be Federalists, because

of their opposition to the war; see William Cooper

Howells, Recollections of Life in

Ohio from 1813 to 1840 (Gainesville, Fla., 1963 [orig. pub.

1895]), 33-34.

15. Brigadier General Simon Perkins to

Major General Elijah Wadsworth, September 4,

1812, Elisha Whittlesey Papers,

container 71, folder 1, WRHS; Muskingum Messenger,

October 20, 1813.

150 OHIO HISTORY

the burdens ...."16

Such militia attitudes led to sharp

reactions against militia officers who

were deemed to have acted too

enthusiastically in calling out the militia.

James Kilbourne, the central Ohio

surveyor, manufacturer, and politician,

complained to Governor Meigs in 1812

about the "most ruinous and oppres-

sive system" operating in Franklin

and Delaware counties under General

Joseph Foos. Foos, said Kilbourne, had

called out the whole military force

(several hundred men) of both counties

on what proved to be a false alarm,

then kept that force in service. While

some units were later allowed to return,

two companies from Worthington were not,

though forty-five men had fami-

lies "with not a person beside

women and small children to do the smallest

chore of work," and others were

landless laborers whose families depended

upon their daily presence. Captain

Stephen Smith of Williamsburg,

Clermont County, had the unfortunate

audacity to volunteer the services of

his company to the state. According to

one observer, evidently a member of

the company, the men cheerfully made

preparations to march, thinking that a

general call on the militia had been

made, but then discovered that no com-

pany other than Smith's was to march.

"The men," reported the observer,

"being freeborn Americans and

jealous of their rights began to think that they

were some way imposed upon," then

reacted with anger upon discovering that

Smith had several times solicited

Governor Meigs for orders: "had not Smith

behaved in a humble manner he would not

have escaped without blows...."

The observer, after stressing the amount

of duty the local militia had will-

ingly performed, argued that the

opposition arose from a love of liberty and

an abhorrence of tyranny and foul play,

rather than disaffection from the gov-

ernment. "When an equal call of the

militia is made," he assured the gover-

nor, they would step forward with

willingness.l7

The zealousness with which Ohioans

guarded their sense of military fair

play eventually reached the higher

ranks, though whether from officers' sense

of equity or simply their desire not to

anger the people whom they com-

manded is hard to say. Brigadier General

George Kisling had to inform his

superior, John Gano, in early 1813 that

a colonel from his brigade refused an

order to provide a company of militia

from his regiment on the grounds "that

the order is oppressive in taking the

whole of the company from the one

Regiment," and that other units had

also been taken from that regiment.

(Kisling, also conscious of equalizing

burdens, noted that the population from

which that regiment was drawn was much

larger than his other regiment.)

Gano himself two days later, when

issuing general orders for detachments of

16. Petition to Elijah Wadsworth, August

28, 1812, Ibid; Petition to Elijah Wadsworth,

October 22, 1812, Container 71, Folder

3, Ibid.

17. James Kilbourne to Return J. Meigs,

1812 (only date), Reel 2, Frames 537-538, RJM pa-

pers, OHS; John Morris to Meigs,

September 8, 1812, Reel 2, Frames 86-87, Ibid.

Burthened in Defense of our

Rights 151

militia from his division, noted that,

because two brigades situated on the

frontier had been more exposed and

performed more duty, he would not call on

them for this detachment. This sort of

justification was necessary to preempt

protests from the other brigades, and to

demonstrate to the Fourth and Fifth

Brigades that their commanding general

would not force upon them an undue

burden. Gano, like other militia

officers, had to walk a tightwire between

military necessity and the outcry that

military hardships perceived as unfair

would raise. It is not surprising that

he felt "a militia office is truly an ardu-

ous, troublesome, expensive, and

unthankful one if strictly and properly at-

tended to."18

The idea of equalizing burdens extended

itself to economic issues as well, as

rich and poor suffered in differing

degrees because of the war. Taxes bore

down more harshly on those of fewer

means, and in addition, the wealthy

could avoid military duty by purchasing

substitutes, or by occupying posi-

tions that would exempt them from

service. Othniel Looker, acting governor

of the state in 1814, recognized the

"undue pressure" of the militia system on

the poor, but suggested that if the

burden were "judiciously apportioned," then

"the spirit of our citizens will be

equal to any emergency."19

Because so many citizens of means found

positions that let them avoid mil-

itary service, exemptions were the first

symbol of economic inequality to

come under fire. Before the war began,

Ohio exempted from military duty all

ministers of the Gospel, judges of the

supreme court, presidents of the courts

of common pleas, jailkeepers,

custom-house officials, postal workers, ferry-

men (on post roads), and those exempt by

federal law. The revisions to the

militia law debated by the Ohio

legislature over the winter of 1812-13 in-

cluded a proposal adding associate

judges, sheriffs, and clerks of court to the

list of exemptions. Defenders of this

measure argued that other states allowed

these exemptions, and that "the

poor man who may have suffered, is obliged

to sit down in silence, and wait the

return of [the armies] before he can have

that justice." Opponents replied

that "no man holding a lucrative office, such

as that of sheriff, or clerk . . . ought

ever to be exempt from military duty;

for if the office is worth holding, it

will furnish the means of procuring sub-

stitutes." The measure failed,

though so too did a simultaneous attempt to

remove the exemption for ministers of

the gospel. The next revision of the

militia laws, passed at the very end of

the war, actually saw most exemptions

removed from the list: only customs

officials, postal workers, and ferrymen

could avoid the prospect of serving in

the military or procuring a substitute.

18. Brigadier General George Kisling to

Major General John S. Gano, February 2, 1813,

"Selections from the Gano Papers

II," Quarterly Publications of the Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio , 15 (April-June, 1921), 25-80; Western Spy, February

13, 1813;

John S. Gano to Major Thomas B. Van

Home, January 17, 1813, "Selections from the Gano

Papers II."

19. Ohio House Journal, Thirteenth

General Assembly, 36-38.

152 OHIO HISTORY

Ohioans were determined that as many

people as possible bear their share of

the burden.20

However, equalizing the burden of the

war did not extend very far towards

making the financial burdens of militia

service more equitable, though there

were calls for such measures. As one

newspaper observed, while the rich and

poor received equal personal protection

from the militia, the poor also pro-

vided property protection for the

rich. The newspaper called for taxes on

wealth so that the poor would not

subsidize the wealthy in this way.21

In late 1814, Thomas Worthington,

recognizing that willingness to per-

form militia duty existed only in

proportion to the perception that the weight

of defense should rest equally on every

member of the community, tried to

convince the legislature to make the

system more fair. "Every man feels con-

solation and satisfaction under the

conviction that he does not bear an unequal

proportion of the public burdens. Such a

state of things will not fail to create

an attachment to the government and a

readiness to contribute to its defence

and support." Worthington observed,

however, that there were people able to

avoid much of the burden: the wealthy

could avoid personal services by pay-

ing a fine, while men without families

could absent themselves during drafts.

This threw the burden of support

"on others in moderate circumstances, un-

able to pay the fine, with large

families to maintain, whose sole dependence

for support is on the head of the

family, and what is worse, taken by such

evasions of the law from their homes,

when least expected and most unpre-

pared." The way the law operated,

Worthington argued, the greatest share of

personal service fell upon that part of

the community least able to bear it.22

Worthington wanted more severe

punishments for draft evaders, but he also

argued for using taxation as a way to

equalize the contributions that citizens

made towards the war. Under his plan,

all males eighteen and over in each

company district would pay an equal

share, but property "real and personal" in

the district would also be taxed

"in fair proportion with the other moiety."

The district would then use the money

raised to engage substitutes equal to

the number of men required, or (in the

event substitutes could not be ob-

tained) to pay the men drafted from the

district. The men could either keep

the money as compensation, or use it to

defray the cost of substitutes. Those

better off would thus help to subsidize

the military burdens of the poor.

20. For prewar exemptions, see Chapter

1, Section 2, "An Act for Disciplining the Militia,"

February 14, 1809, Acts Passed,

Seventh General Assembly. Changes to exemptions can be

found in Chapter 39, Section 29,

"An Act for Disciplining the Militia," February 9, 1813, Acts

Passed, Eleventh General Assembly, and Chapter 54, Section 30, "An Act for Organizing

and

Disciplining the Militia," February

14, 1815, Acts Passed, Thirteenth General Assembly.

21. Zanesville Express &

Republican Standard, February 17, 1813.

22. Muskingum Messenger, November

9, 1814 (reprinted from the Washington Gazette);

Governor's Message to Legislature,

December 21, 1814, in Ohio House Journal, Thirteenth

General Assembly, 104-05.

Burthened in Defense of our

Rights 153

Every man in the community would

contribute, each more or less according

to his means.23

This was too radical a scheme for the

legislature, which did not adopt it.

Legislators recognized the problems that

Worthington pointed out, but were

unwilling to adopt the sort of

progressive taxation for which the governor

called. The measure that the legislature

did adopt was one that affected far

fewer people. For "the purpose of

carrying into effect the provisions of this

act with equality and justice to all

descriptions of the militia," the revised

militia act prescribed that those

individuals who had heretofore been exempted

from militia duty because of physical

infirmity who owned a tract of land, a

house and lot in town, or were

proprietors of a store, would be listed on the

local company muster rolls, and would

have to pay equal shares, along with

all other militiamen, towards purchase

of a substitute (this system is de-

scribed in more detail below).24

This act would, to a certain extent,

help to equalize the burdens of military

service by making certain members of the

community who had not previ-

ously contributed to the public defense

bear their fair share. It did not, how-

ever, act to remedy the problems with

the militia system that Worthington

outlined. Community leaders were more

willing to exhort people to con-

tribute to the war and to exercise

charity towards neighbors in straitened cir-

cumstances than to advocate a new system

of taxation. Be kind to the fami-

lies whose men are in service, advised

one newspaper, because "it is a com-

mon cause, and the family of that man

who by lot has been called into the

service, ought no more to suffer than

those who have the means of living

well." But while many families did

receive aid from others in their commu-

nity, hardships could never be

altogether alleviated.25

A Land Weary of War

As the war dragged on with no end in

sight, spirits flagged considerably in

Ohio, and patriotic ardor lessened. As

early as February 1813 the Zanesville

Express lamented the reluctance of Ohioans to turn out for

defense: "The re-

port of a draft causes some to abscond,

while others obstinately refuse to enter

the ranks of war, and set the laws at

defiance-Where is the spirit of '76?

Where is the patriotism of 1812 ...

?" The patriotism had not disappeared

altogether, but the willingness to serve

in the militia had slowly ebbed away.

Tiresome service in garrisons and

frequent false alarms coupled with severe

lags in service pay led eventually to a

virtual disintegration of Ohio's militia,

23. Ibid, 105-06.

24. Chapter 54, Section 49, "An Act

for Organizing and Disciplining the Militia."

25. Muskingum Messenger, October

20, 1813.

|

154 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

and provided Ohio Federalists, who used discontent with the militia system to oppose the war and Republicans, with political ammunition.26 While no one doubted the importance of serving in the militia if threats to Ohio were imminent, many disliked the most common forms of militia ser- vice, which usually consisted of garrison duty or responding to real or sup- posed British and Indian threats. "We have lately had afalse alarm which has given considerable trouble," General Duncan McArthur confessed to Thomas Worthington in 1813; "I have just returned from a ride of about 200 miles in consequence of it. And in course of my travels called many off from their harvest, who could illy spare the time." Those called off for false alarms- like the militia noted earlier who served under Joseph Foos--seldom took such occurrences lightly.27 The most important false alarms for the Ohio militia were the Fort Meigs incidents in 1813, the lasting consequences of which can be identified as the

26. Zanesville Express, February 17, 1813. 27. Duncan McArthur to Thomas Worthington, July 10, 1813, Reel 8, Frames 485-87, Worthington Papers, OHS. |

Burthened in Defense of our

Rights 155

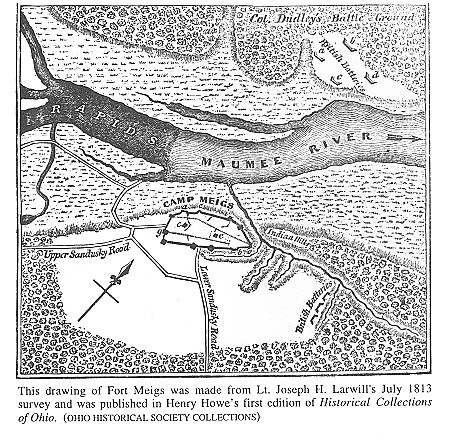

turning point for people's willingness

to serve in the military. Fort Meigs, a

strong fort constructed in early 1813,

was situated on the Maumee Rapids in

northern Ohio, where its blockhouses and

batteries protected supply lines and

the surrounding country. In the spring

of that year, British general Henry

Procter and an army of over 2,000

regulars, militia, and Indians travelled

across Lake Erie to attack the fort,

defended by only about 550 men under

William Henry Harrison. Procter resorted

to siege warfare to take the fort,

beginning with an artillery bombardment

on May 1, 1813. An attempt by

Kentucky militia a few days later to

relieve the fort overran the British guns,

but a sharp counterattack by British and

Indians resulted in almost 50 percent

casualties (mostly prisoners) for the

1,200 Kentuckians. But Procter, whose

militia were unhappy and whose Indians

were leaving in large numbers, lifted

the siege on May 9 and returned to

Canada. In July he returned, this time

with some 5,000 troops, and tried

enticing the defenders of Meigs to leave

their fortifications, but with no

success. Procter withdrew his forces a second

time, this time for good, as the American

navy under Oliver Hazard Perry

soon achieved command of Lake Erie.28

Fort Meigs became a problem for the Ohio

militia because during the crisis

Governor Return J. Meigs had mobilized a

force of several thousand Ohio

militia to come to the relief of the

fort. Harrison, however, preferred instead

to rely on the Kentuckians to fight the

British. Once the British left,

Harrison met Meigs and his militia at

Lower Sandusky in mid-May. After

giving the troops an address praising

their patriotism in assembling to relieve

the fort, Harrison dismissed most of

them, keeping only a few Ohio militia.

Initially, Ohioans were simply proud of

the "zeal and alacrity" that their citi-

zens had shown in turning out so many

militia (estimates vary, but at least

2,000 actually marched) in so short a

period of time. "Such zeal, such

promptitude, such patriotism was never

surpassed in the annals of the world,"

gushed the Freeman's Chronicle in

late May. "All ages and ranks of citizens

flocked by one noble impulse

simultaneously to the standard of their country.

The aged veteran and the beardless

stripling, the farmer, the merchant and the

mechanic mingled indiscriminately in the

ranks.... We are confident that if

the fort had not relieved itself for

10 days longer, ten thousand men from

Ohio would have been on the march

towards it." Another newspaper noted in

mid-May that the "honorable display

of patriotism" was almost universal,

28. This account is largely drawn from

Alec R. Gilpin, The War of 1812 in the Old Northwest

(East Lansing, Mich., 1958), 173- 93,

201-08; Mahon, The War of 1812, 159-64; and Reginald

Horsman, The War of 1812 (New

York, 1969), 99-102. A contemporary author, Robert

Breckinridge McAfee, describes these

incidents in more detail in History of the Late War in the

Western Country (Lexington, Ky., 1816), Chapters VI-VIII. The Canadian

militia were un-

happy because they needed to return to

Canada to plant corn in order to feed their families

during the winter.

156 OHIO HISTORY

and party distinctions done away with.29

But the exultation at the initial relief

of Fort Meigs soon turned sour,

largely because the events of the next

few months, especially Procter's second

attempt to take the fort, caused what

amounted to more false alarms for the

militia. They once more mobilized to

defend against British invasion, but

never saw the enemy. As one officer

observed in July, "The militia were col-

lecting again to relieve Fort Meigs . .

. but the emergency must have been

great indeed to have roused the people

at this busy season of the year.

Numbers however convened until the glad

tidings were received that the Army

and the outposts were [safe]. You can

hardly imagine, Sir, how joyful was

the news, to the laboring people of the

state who are just beginning harvest.

To have been compelled to march at this

period must have ruined many fami-

lies, and left the crops

unattended." The Zanesville Express, which in May

had been so proud of how Ohioans of all

political stripes had responded to the

siege of Fort Meigs, three months later

was quite bitter that ". . the militia of

this state have once more been sent to chase

the wild goose. They are or-

dered to return home, except 2,000 ....

Such repeated calls upon the mili-

tia, and so much ado about nothing, is

calculated to damage the ardor of their

patriotism, and to lessen their

sensibility in behalf of their country. There

has been gross mismanagement

somewhere." Similarly, the Freeman's

Chronicle was no longer speaking proudly of militia call-ups:

". .. our

Farmers and Mechanics are as patriotic

and as willing to defend their rights as

any people under the sun-but they are

irritated and disgusted at being

marched and countermarched as they have

been during the last four or five

months, when no good has been effected

by all their sacrifices." To some,

militia service seemed even less useful

after the American victories at the

Thames River and on Lake Erie in the

fall of 1813, which seemed to remove

any immediate threats to Ohio.30

Militia alarms, real and false alike,

caused Ohioans considerable economic

hardships, especially as active periods

of campaigning usually coincided with

peak times of farming. Other

militia-related hardships included militia fines

and problems in paying those who served;

of the two, militia fines were less

of a problem, inasmuch as they applied

only to those who refused to perform

their required duty. But the fines were

resented, even though they allowed

those who paid to avoid serving. Eleven

people were fined a total of $157.00

(a considerable sum) in December 1812 in

Zanesville, and this was by no

means exceptional as fines for

individuals who refused to serve tours of duty

could reach sixty dollars or more. The

fines were made even more painful be

29. Freeman's Chronicle, May 28,

1813; Zanesville Express & Republican Standard, May

12, 1813.

30. Jesup N. Couch to Thomas

Worthington, July 5, 1813, in Thomas Worthington and the

War of 1812, 212; Zanesville Express, August 18, 1813; Freeman's

Chronicle, August 20, 1813.

|

Burthened in Defense of our Rights 157 |

|

cause they often were not applied uniformly across the state. Depending upon arbitrary enforcement by officers, militia companies might be fined heavily or not at all. Because of the lack of uniformity, in fact, Governor Meigs directed at least one militia general not to collect fines, an action which did little to enforce discipline or to stop the arbitrary imposition of penalties. The case of militiaman George Bright, an inhabitant of Lancaster, is instructive in this regard. Bright was fined $120 in February 1814 for not performing a tour of duty with the militia the previous winter. In his defense, he produced several witnesses who testified that he had been sick almost all that winter. However, when one of the members of his board of inquiry asked Bright whether he would have served had he been healthy, Bright equivocated, saying he did not know whether he would have, after which, in the words of the clerk, "the court decided that he may as well be fined." Militiamen far more |

158 OHIO

HISTORY

circumspect and intelligent than Bright

also found the imposition of militia

fines arbitrary.31

The most important cause of militia

disintegration in Ohio, though, was

the fact that Ohio militia more

frequently than not received pay for their ser-

vices only well after the fact, if at

all. Ohio, with very little money of its

own, depended upon the United States to

pay its militia for their services

when called up against Indians or the

British. Consequently, compensation

for militia duty meant a tortuous

process of delay and red tape leading all the

way to Washington, D.C., and back.

Indifferent record-keeping and military

exigency often created additional

problems. This knowledge that payment

would be slow in coming, if in fact it

came, made the economic hardships

that militia service often entailed all

the more threatening. How could the

head of a household take care of his

family if he were to go on a six-month

tour of militia duty but not receive pay

for an extended period of time?

The problem of nonpayment obviously

created difficulties for officers try-

ing to raise troops. One officer tried

to raise a company of militia in

Circleville in January 1813, but failed.

The men would not volunteer, he told

Meigs, because they had not been

remunerated for past services, "nor noticed

in any other way to distinguish them

from the men who sit quietly at home,

heedless of their country's call,

bettering their circumstances by the necessity

of the times." The problem worsened

as the war progressed. A year later, the

same officer addressed Thomas

Worthington: "The Militia draft will be very

oppressive at this time, and what makes

it more discouraging to them, is that

government have been very remiss in

paying those that have been out. There

is not a man in this Division, who will

turn out at all, but what has been out

at one time or another; and you know

that few of them have been paid. This

neglect on the part of the general

government have begun to lose the patrio-

tism of the citizens of Ohio."32

Worthington experienced the problem

firsthand when he became commander

in chief of Ohio's militia in late

1814. Discussing the problems of raising a

regiment of militia with his adjutant

general, Worthington noted that because

of the current state of militia

organization, as well as the militia law, it

31. The example of militia fines is from

the Zanesville Express & Republican Standard,

February 3, 1813. That it is not

atypical can be seen by inspecting surviving regimental record

books. For instance, the record book for

the Second Regiment, Fourth Brigade, Third Division

of Ohio Militia during the war contains

mostly fines of small amounts for lack of equipment or

not appearing at muster, but several

fines of $60 or more (often to be paid in monthly pay-

ments); see MSS 2396, Western Reserve

Historical Society. The Third Regiment, First

Brigade, Second Division of Ohio Militia

issued some very heavy fines; see the John Hayslip

Papers, MSS 2944, WRHS. For the Bright

case, see "Proceedings of a Court of Inquiry in [the]

Case of George Bright," February

18, 1815, George Bright Papers, VFM 2733, OHS.

32. James Denny to Return J. Meigs,

January 16, 1813, Reel 3, Frame 19, RJM Papers, OHS;

Denny to Thomas Worthington, February

12, 1814, Reel 9, Frame 44, Worthington Papers,

OHS.

Burthened in Defense of our

Rights 159

would be difficult to raise the desired

number of men. "Other causes will con-

tribute to this effect," he

observed, "and one principally I have much com-

plaint against because of the

non-payment of those who have already per-

formed service." We must, he added,

do the best we can.33

By the beginning of 1815 the militia in

Ohio had virtually collapsed. The

economic hardships, the fines, the lack

of pay, the repeated call-ups-all with

no end in sight-caused support for the

institution to drop to almost nothing.

The problems with the militia proved

fertile ground for Federalist propaganda,

which many Ohioans felt fueled the

problems in the first place.

Federalists, though few in number in

Ohio, tried to use dissatisfaction with

the militia system to their advantage.

One resident of Dayton, identifying

himself as "one of the

people," warned his fellow residents in late 1813 that a

recent meeting of a board of militia

officers that had produced a slate of candi-

dates for local office had been

infiltrated by Federalists, who tried to have

"federal proceedings" pass as

Republican ones. "Beware of snakes," the writer

declared, "something, is

busy to make you believe it will have the militia law

altered, or modified, or repealed-that

you will not have military duty to per-

form, or military fines to pay .... The

scheme is to do away the militia sys-

tem, and make you believe that taxes on

non-resident lands can . . . defray all

the expenses of the militia

system." Whether or not the individuals in ques-

tion actually were Federalists, or had

simply been labeled as such, is difficult

to say; what is important is that

Federalists, or someone in sympathy with

them, were associated with opposing the

militia system.34

The most notorious Ohio Federalist was

Charles Hammond, editor of the

Ohio Federalist, published in St. Clairsville in the eastern portion of

the

state. Hammond frequently used invective

and sarcasm in the pages of his

paper to oppose the war and the

Republican leadership running it. He also of-

ten protested the "harassing calls

on the militia." According to Isaac Van

Horn, the adjutant general, the efforts

of Hammond's paper and other

Federalists "nigh put down the

drafting of militia" in the region around

Zanesville and St. Clairsville in the

late summer of 1814. "There are in-

stances of whole companies refusing to join,"

he stated, and though fines had

been assessed, none had yet been

collected.35

Such circumstances were by no means

unusual in 1814. The Freeman's

Chronicle reported in March of that year that a recent draft of

1,400 militia

had not yet been half-filled. "A

most culpable remissness exists some-

where," the editor stated, but

could not pinpoint the source. Militia generals

33. Thomas Worthington to Isaac Van

Horn, December 19, 1814, LEO Reel 1, Frames 07-

08.

34. Ohio Centinel, October 4,

1813.

35. The Ohio Federalist, January

5, 1815; Isaac Van Horn to Othniel Looker, August 16,

1814, Reel 1, Frames 162-163, OL Papers,

OHS.

160 OHIO

HISTORY

frequently had to inform their superiors

that draft requirements could not be

met, and those who did turn out

increasingly were substitutes. "Every exer-

tion is used," confessed one

officer, "but the men refuse to march."36

Van Horn was quick to attribute blame

for the laxness in the militia to do-

mestic opposition. He had no doubt that

it would take a great deal of effort to

make Ohio's militia effective,

"seeing that a host of internal enemies to the

administration of the general government

are exerting themselves to parralise

and render the militia as contemptable,

and inefficient as possible." By late

1814, even his hometown Zanesville

Express, a paper that took pains to

stress that though it was a federal

newspaper it was not extreme, labeled the

state's inability to raise militia a

heinous dereliction of duty. "Proh pudor!

[For shame!]" the newspaper

exclaimed scornfully, "that Ohio the most war

loving state in the Union, except

Kentucky, should be so wanting in patrio-

tism!"37

By the tail end of 1814, the militia

system was in complete disarray. The

state government had no idea how many

weapons or men were in the frontier

areas, and across the state, especially

in its eastern portion, men refused to

serve. Indeed, many militia units

consisted almost entirely of substitutes

raised from fines collected from those

not serving. Discharge certificates,

proving that one had performed a tour of

duty, had become a medium of ex-

change, as militiamen sold them to

citizens who wanted to avoid duty. The

state was unable to comply with federal

requisitions of militia.38

Worthington proposed revisions to the

militia law, many explained above,

but to his irritation the legislature

took no action on most of them,

"nonwithstanding we are threatened

with destruction by both internal and ex-

ternal opposers and enemies." At

the same time, frustration with the militia

system caused Worthington and the state

legislature to consider alternative

means of furnishing a military force by

doing away with compulsory militia

service entirely and creating in its

place a state army of some 3,000 officers

and men for a period of two to three

years. Ohio would offer this body of

men to the United States in lieu of

militia drafts. Several other states had

considered creating state armies, most

notably Massachusetts, which passed a

bill establishing one (never actually

raised) largely in order to have a military

force free from federal control.

Worthington, on the other hand, had no

36. Freeman's Chronicle, March

11, 1814; Brigadier General J. Patterson to Elijah

Wadsworth, September 30, 1814, Elisha

Whittlesey Papers, Container 71, Folder 4, WRHS;

Brigadier General John Campbell to

Wadsworth, December 12, 1814, Ibid.

37. Isaac Van Horn to Othniel Looker,

May 11, 1814, Reel 1, Frames 62-64, OL Papers,

OHS; Zanesville Express, November

16, 1814. For another example of Van Horn's opinion of

the effect of political opposition, see

Van Horn to Looker, April 9, 1814, Reel 1, Frames 15-16,

OL Papers, OHS.

38. On discharge certificates, see

Duncan McArthur to Return J. Meigs, June 28, 1813, Reel

1, Frames 38-39, Duncan McArthur Papers,

Microfilm Edition, Ohio Historical Society.

McArthur claimed that such exchanges

occurred daily.

|

Burthened in Defense of our Rights 161 |

|

|

|

qualms about letting the general government use his state army; he simply wanted to establish an alternative to militia drafts.39 The legislature refused to create the corps of troops, causing another frustra- tion for Worthington, who admitted he had been "very desirous" of it. What the state government did do, however, was quite important: it fundamentally transformed the nature of the militia system, eliminating the idea of equal service. It openly admitted what had for some time become obvious, that the militia system had devolved into a system of purchasing substitutes. Under the revisions to the militia law passed by the Thirteenth General Assembly, militia captains called upon for men would divide their militia company into a number of classes, or groups, each of which would provide a single man. A class could draft one of its members, or, the more likely possibility, its members could together purchase a substitute. In essence, the legislature provided Worthington with his state army by another route. By doing away with the principle that every man should be required to perform military ser-

39. Worthington to Van Horn, February 4, 1815, LEO, Reel 1, Frame 23; Worthington to James Monroe, January 17, 1815, Ibid, Frames 17-19. |

162 OHIO HISTORY

vice the new laws changed the militia

system into a recruiting service. The

ideal of the

"citizen-soldiers" who would step forward to serve their country

was dropped in the face of the realities

of war.40

Conclusion

News that peace had finally been reached

between the United States and

Great Britain reached Ohio only a little

more than a week after the legislature

had passed the law altering the nature of

the militia system. As a result,

though concern for the frontier existed

for some time, most of the pressure on

the militia system evaporated. Later

revisions of the militia law established a

rather more traditional system.

Ohio's experiences with the militia

during the war, though, provide valu-

able insight into the relationship

between the military and society. In Ohio,

only after several years of war did

political opposition to it have an effect on

people's attitudes and actions. Rather,

it might be argued that it was the war

itself, with its perceived hardships and

the nation's lack of success at waging

it, that provided its own opposition.

Many served willingly, while other

communities and individuals by their

protests gave notice that they were will-

ing to serve as long as their service

was matched by that of their fellow citi-

zens. The state ultimately failed to

convince its citizens that the hardships

they endured were equitable. Under the

resulting pressure, the militia system

metamorphosed into something quite

different from the republican bulwark of

liberty it had originally symbolized,

because the people rejected their

"people's army."

40. Worthington to Monroe, February 20,

1815, Reel 1, Frames 32-33, LEO, OHS; Chapter

54, Sections 44-45, "An Act for

Organizing and Disciplining the Militia," Acts Passed,

Thirteenth General Assembly.

MARK PITCAVAGE

"Burthened in Defence of our Rights":

Opposition to Military Service in Ohio

During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 has long been famous as

a war to which substantial op-

position existed in the United States.

The nearness of the Congressional vote

over the declaration of war, the refusal

of several New England states to pro-

vide militia for the invasion of Canada,

and the Hartford Convention in 1814

are all notable examples of the degree

to which the nation divided over the is-

sue of war with Great Britain.

Unfortunately, these incidents have led

historians to concentrate on the po-

litical opposition to the War of 1812,

viewing it as the natural outgrowth of

the Federalist-Republican battles of the

early national period. Because

Federalists so vocally opposed the war,

they receive attention at the expense

of other groups, and New England, that

bastion of Federalism, receives atten-

tion at the expense of the rest of the

country. The danger of concentrating

solely on political issues is that the

effects of the war itself on American

communities-and thus public

opinion-might be overlooked.1

This article examines the opposition to

military service that arose in Ohio

during the course of the War of 1812,

the nature of that opposition, and its ef-

fects. Along with Kentucky and

Tennessee, Ohio (dominated by Jeffersonian

Republicans) was one of the western

states which cried out for war in 1811

and 1812, and whose citizens flocked to

the colors when war appeared immi-

nent. As the war dragged on, however,

Ohioans became less enthusiastic

Mark Pitcavage would like to thank Allan

R. Millett, Joan E. Cashin, Mark Grimsley, and

Virginia Boynton for their advice and

assistance in writing this article. Any errors are his own.

1. Of the standard scholarly histories

of the war, the two which provide most coverage of

opposition to the war are Donald R.

Hickey, The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict, (Urbana,

Ill, 1989), and J. C. A. Stagg, Mr.

Madison's War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the

Early American Republic, 1783-1830, (Princeton, N.J., 1983). John K. Mahon, The War of

1812, (Gainesville, Fla, 1972), provides some information.

Recent specific studies of opposi-

tion include Edward Bryan,

"Patterns of Dissent: Vermont's Opposition to the War of 1812,"

Vermont History, 40 (Winter 1972), 10-27; Sarah M. Lemmon, "Dissent

in North Carolina

During the War of 1812," North

Carolina Historical Review, 49 (Spring 1972), 103-18: Myron

F. Wehtje, "Opposition in Virginia

to the War of 1812," Virginia Magazine of History, 78

(January 1970), 65-86; and Ellen P.

Hoffman, "Unnecessary, Unjustified and Ruinous: Anti-

war Rhetoric in Massachusetts Federalist

Newspapers" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Massachusetts, 1984).

(614) 297-2300