Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

ARTHUR E. DeMATTEO

The Downfall of a Progressive: Mayor

Tom L. Johnson and The Cleveland

Streetcar Strike of 1908

On November 6, 1907, Cleveland Mayor Tom

L. Johnson awoke to head-

lines announcing his landslide triumph

in the previous day's municipal elec-

tion. Democrat Johnson, the champion of

progressive urban reform and pub-

lic control of utilities, had solidified

his position as the city's most powerful

politician by crushing the best

candidate the Republican Party could offer.

The vote was a referendum on the mayor's

six-year crusade for low streetcar

fares, and the Cleveland Plain Dealer

reported that"the victory of Mayor Tom

and 3-cent fare was complete."1

Johnson immediately declared his intention

to run for a fifth term two years hence,

and appeared to desire nothing more

than leadership of the Ohio Democratic

Party. But the mayor's impressive

reelection had attracted national

attention, and some party luminaries, notably

House Democratic leader Champ Clark,

began to eye Johnson as a possible

1908 presidential alternative to the

twice-rejected William Jennings Bryan.2

A series of mishaps and miscalculations,

centered around Cleveland's street

railway situation, soon eclipsed the

promise of that autumn morning. The

1907 victory was Johnson's last, and

within two years he lost city hall to a

political lightweight, the victim of a

reversal in fortune more dramatic than

any in the city's history. Robert H.

Bremner has described Tom Johnson as

"greedy for affection and greedy

for accomplishment."3 In the months follow-

ing the election these characteristics,

manifested in a single-minded determina-

tion to push through his streetcar

reforms, set the mayor on a collision course

with Cleveland's unionized transit

employees. The ensuing strike of 1908 ru-

ined Johnson's political career and

probably hastened his death.

Arthur E. DeMatteo is a Ph.D. candidate

in American labor history at the University of

Akron. He wishes to thank Professors

Daniel Nelson and James F. Richardson for reading

earlier drafts of this article and

providing helpful criticisms and suggestions.

1. Cleveland Plain Dealer, November

6, 1907.

2. Ibid., November 11, 22, 1907; New

York Times, November 8, 9, 1907.

3. Robert H. Bremner, "The Civic

Revival in Ohio: The Fight Against Privilege in Cleveland

and Toledo, 1899-1912" (Ph.D.

diss., Ohio State University, 1943), 46.

Downfall of a Progressive

25

Tom L. Johnson was the quintessential

"self-made man." The product of

an impoverished Southern family, he made

his fortune in the street railway

business after developing a new-style

glass-and-metal farebox in Louisville,

Kentucky, in 1873. The money earned from

this inventionenabled Johnson

to purchase interests in streetcar lines

in Indianapolis, St. Louis, Brooklyn,

Cleveland, Detroit, and Johnstown,

Pennsylvania. To produce rails for his

lines, he obtained interests in steel

mills in Lorain, Ohio, and in Johnstown,

where he also manufactured electric

streetcar motors. Johnson deservedly

earned a reputation for innovative

business techniques, particularly in his op-

eration of the Johnstown plant.4 But

he also gained notoriety for his ques-

tionable ethics, as he specialized in

refurbishing rundown lines, watering the

stock, and then selling his interests at

inflated prices.5

In 1883 Johnson became familiar with the

writings of Henry George, the

single-tax reformer. He later claimed to

have been deeply troubled by

George's condemnation of the

inequalities in society, and nearly retired from

business. After the two became friends,

however, George convinced Johnson

to continue his entrepreneurial

pursuits, but to devote his riches to the causes

of reform. Johnson followed this advice

by financing George's political cam-

paigns and subsidizing various

single-tax publications, most notably The

Public. With George's encouragement Johnson ventured into

politics him-

self, representing Cleveland's

Twenty-first District in Congress from 1891 to

1895.6

Eugene C. Murdock has written that

"the pre-Georgian Johnson and the

post-Georgian Johnson were two different

men,"7 but Johnson's struggle with

Mayor Hazen Pingree of Detroit from 1895

to 1899 provides evidence to the

contrary. In 1894 Johnson's brother

Albert headed a group of investors which

purchased Detroit's Citizens' Street

Railway Company, and upon leaving

4. James R. Alexander,

"Technological Innovation in Early Street Railways: The Johnson

Rail in Retrospective," Railroad

History, 164 (Spring, 1991), 64-85; Alfred Chandler Jr. and

Stephen Salsbury, Pierre S. DuPont

and the Making of the Modern Corporation, (New York,

1971), 25-28; "Louisville Scenes:

The Autobiography of Fr. Richard J. Meaney," Filson Club

Historical Quarterly, 58 (January, 1984), 11-12; Tom L. Johnson, My Story,

ed. Elizabeth J.

Hauser, (New York, 1911), 1-33; Michael

Massouh, "Innovations in Street Railways before

Electric Traction: Tom L. Johnson's

Contributions," Technology and Culture, 18 (April, 1977),

202-17, and "Technological and

Managerial Innovations: The Johnson Company, 1883-1898,"

Business History Review, 50 (Spring, 1976), 46-68; Eugene C. Murdock,

"Cleveland's

Johnson," Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, 62 (October, 1953), 323-33;

Daniel Nelson, "Scientific

Management in Transition: Frederick W. Taylor at Johnstown,

1896," Pennsylvania Magazine of

History and Biography, 99 (October, 1975), 466-67.

5. Frederic C. Howe, The Confessions

of a Reformer, (New York, 1925; reprint ed.,

Chicago, 1967, with introduction by John

Braeman), 87; Eugene C. Murdock, "A Life of Tom

L. Johnson" (Ph.D. diss., Columbia

University, 1951), 15.

6. Johnson, My Story, 48-81;

Murdock, "Cleveland's Johnson," 327. For Johnson's

Congressional career, see Robert Gordon

Rawlinson, "Tom Johnson and His Congressional

Years" (M.A. thesis, Ohio State

University, 1958).

7. Murdock, "Cleveland's

Johnson," 327-28.

26 OHIO HISTORY

Congress Tom Johnson joined the company

as president. The Citizens' line

enjoyed monopoly control of public

transit in the city, and charged a fare of

six tickets for twenty-five cents. In

1895 Pingree, determined to provide low

fares for Detroit's working class,

convinced the city council to franchise a

new privately-owned streetcar line, the

Detroit Railway Company, stipulating

a fare of eight tickets for twenty-five

cents and free transfers. Realizing the

danger this new competition posed to the

Citizens' Company, Johnson at-

tempted to stop the low fare line.

Appealing to the Wayne County Court and

the Michigan Supreme Court, Johnson

contended that his company's fran-

chise gave it exclusive rights to

operate streetcars in Detroit, but both courts

ruled in favor of the city's right to

grant competing franchises.8

Having failed to thwart the new low-fare

company, Johnson lobbied city

council for a thirty-year franchise

renewal for the Citizens' line. Pingree, ve-

hemently opposed to Johnson's plans to

institute a five-cent fare, vetoed the

enabling ordinances. When Johnson

retaliated by raising fares and eliminat-

ing free transfers, Pingree led

thousands of angry workers in a boycott of the

Citizens' Company. Forced to capitulate,

Johnson temporarily reinstated the

old fare in December 1895. But a short

time later he purchased the Detroit

Railway Company and merged it with the

Citizens' line. By 1897 Johnson

once again had monopoly control over

Detroit's public transportation sys-

tem.9

Nonetheless, Pingree's political clout

prevented Johnson from winning his

coveted thirty-year franchise. After a

series of maneuvers and negotiations,

Johnson agreed in 1899 to sell his lines

to the Detroit Street Railway

Commission, a quasi-public holding

company conceived by Pingree. But the

mere fact that he was willing to sell

raised suspicions, so great was the pub-

lic's distrust of Johnson. Detroit's

newspapers and numerous civic leaders

questioned Johnson's motives and feared

that he would swindle the city. "If

Tom L. Johnson has not always been an

enemy of the people," asked one city

official, "then in the name of

common sense who has?" Under increasing

public pressure, the Citizens' Company

withdrew its offer to sell in July,

1899. Johnson resigned his post soon

after and departed for Cleveland.10

The conflict with Pingree began twelve

years after Tom Johnson's sup-

posed conversion to humanitarian reform,

and is inconsistent with the "pre-

Georgian/post-Georgian" argument.

During most of his stay in Detroit

8. Melvin J. Holli, Reform in

Detroit: Mayor Hazen S. Pingree and Urban Politics, (New

York, 1969), 101-04; Graeme O'Geran, A

History of the Detroit Street Railways, (Detroit,

1931), 126-41.

9. Holli, Reform in Detroit, 105-11;

O'Geran, History of the Detroit Street Railways, 146-47.

10. Holli, Reform in Detroit, 111-20;

Ashod Rhaffi Aprahamian, "The Mayoral Politics of

Detroit, 1897 through 1912" (Ph.D.

diss., New York University, 1968), 92-96. Holli's account

of Johnson's experiences in Detroit,

culled from local newspapers and court and city council

records, contrasts with Johnson's self-serving

version in My Story, 91-97.

Downfall of a Progressive 27

Johnson did everything in his power to

disrupt Mayor Pingree's progressive

streetcar program. In the process, he

also learned a great deal from the mayor.

As Melvin Holli has noted, Pingree

undoubtedly had a more profound impact

on Johnson than any of George's

writings. Many of the reforms Johnson

would promote as Mayor of Cleveland were

similar to Pingree's programs in

Detroit, most notably the low-fare campaign.ll

Johnson admitted in his au-

tobiography that "It was Mayor

Pingree's promotion of that three-cent-fare

line for Detroit that first impressed me

with the practicality of this rate of

fare."12 The public

ridicule he experienced in Detroit humiliated Johnson.13

Cleveland's city hall and the low-fare

issue presented the means to resuscitate

his bruised ego.

Tom Johnson won election as mayor of

Cleveland in April 1901. During

his years in office he attacked

corruption in government, modernized and ex-

panded city services, provided parks and

playgrounds, fought for tax reform,

worked for the humane treatment of

prisoners, and promoted various beautifi-

cation projects. But these

accomplishments were peripheral to Johnson's ma-

jor goal: municipal control of public

transit. Running his campaigns on the

slogan, "Three Cent Fares and

Universal Transfers," the mayor waged a high-

energy crusade against the private

streetcar companies from the day he took

office. 14

Although Ohio laws at this time

prohibited municipal ownership of public

transportation systems, Johnson devised

a scheme to give the city control

over the street railways. As the

franchises of the high-fare companies expired,

the mayor and city council denied

renewals of the old grants. Instead, they

franchised new companies, bound by the

terms of the grants to charge three-

cent fares-the average had been 4.71

cents-and to sell the lines to the city

once state laws could be amended. After

numerous delays caused by nearly

sixty court injunctions obtained by the

old companies, Cleveland's first three-

cent streetcar line, the Forest City

Railway Company, went into operation on

November 1, 1906. One month later, a

second three-cent line, the Low Fare

Company, was added. A quasi-public

holding company, the Municipal

Traction Company, took control of the

lines. To insure de facto public con-

trol over Municipal Traction, a number

of Johnson's political allies served on

the board of directors. The high-fare

lines, meanwhile, had merged into a sin-

gle entity called the Cleveland Electric

Railway Company, or "Concon," in

11. Holli, Reform in Detroit, 121-22,

242fn.

12. Johnson, My Story, 95.

13. Holli, Reform in Detroit, 120-21.

14. Bremner, "Tom L. Johnson,"

Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, 59

(January, 1950), 3-4; George W. Knepper,

Ohio and Its People, (Kent, Ohio, and London,

England, 1989), 330-31; Murdock,

"Cleveland's Johnson: Elected Mayor," Ohio Historical

Quarterly, 65 (January, 1956), 28-43; Hoyt Landon Warner, Progressivism

in Ohio, 1897-

1917, (Columbus, 1964), 72-73.

28 OHIO

HISTORY

1903. The company carried its battle

with Johnson all the way to the United

States Supreme Court, but after an

unfavorable ruling in December, 1906,

Concon reasoned that it would be only a

matter of time before the city re-

scinded all of its franchises. Concon's

very survival, therefore, depended on

the defeat of Johnson in the 1907

mayoral election.l5

Mayor Johnson did, in fact, show signs

of political vulnerability.

Although elected by large pluralities in

1901, 1903, and 1905, extenuating

circumstances in each case prevented

Johnson from demonstrating anything

approaching invincibility. In 1901, for

instance, the Republicans nominated

William J. Akers, whose association with

previous, scandal-ridden administra-

tions doomed him to likely defeat.

Johnson's margin of victory was 6056

votes; any reputable Democrat would have

done as well. The 1903 election

represented an opportunity for the

electorate to show its disapproval of the so-

called "Nash Code," a

Republican-sponsored effort to weaken the mayor's

control over city government. Strongly

associated with political bossism and

the city's unpopular private streetcar

faction, the code was a burden to the

GOP's Harvey Goulder, who fell to

Johnson by 5985 votes. In 1905

Johnson crushed Republican William H.

Boyd by over 12,000 votes. But

Democrats throughout the state scored

similar victories that November by rid-

ing the coattails of gubernatorial

candidate John M. Pattison, whose landslide

victory over Governor Myron T. Herrick

can be attributed to the public's re-

pudiation of the political machine of

Cincinnati's George B. "Boss" Cox.

Pattison's margin of victory in

Cleveland was actually greater than

Johnson's.16

Republicans took note of the peculiar

nature of these elections and pointed

to the gubernatorial race of 1903 as a

true indicator of Johnson's standing

with the Cleveland electorate. After his

mayoral reelection in April of that

year, Johnson challenged Governor

Herrick, a fellow-Clevelander, in Novem-

15. Edward W. Bemis, "The Street

Railway Settlement in Cleveland," Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 22 (August, 1908), 543-49; Bremner, "The Street

Railway Controversy in

Cleveland," American Journal of

Economics and Sociology, 10 (January, 1951), 186-94, and

"Tom L. Johnson," 4-5; Electric

Railway Review, January 5, 1907, 11, January 12, 1907, 55,

January 19, 1907, 66-67; Warren S.

Hayden, "The Street Railway Situation in Cleveland,"

Proceedings of the Cincinnati

Conference for Good City Government and the Fiftieth Annual

Meeting of the National Municipal

League, (1909), 403-04; Howe, Confessions

of a Reformer,

116-18; Johnson, My Story, 237-38,

246-49.

16. Barbara Clemenson, "The

Political War Against Tom L. Johnson, 1901-1909" (M.A.

thesis, Cleveland State University,

1989), 239-69. There are slight, inconsequential discrepan-

cies in ward-by-ward vote totals in

Cleveland's daily papers for municipal elections from 1901

to 1909; Clemenson's figures, obtained

from the Cuyahoga County Archives, are used through-

out this article, unless otherwise

noted. Cleveland Leader, October 21, 1907; Knepper, Ohio

and Its People, 332; Murdock, "Cleveland's Johnson: The Burton

Campaign," American

Journal of Economics and Sociology, 15 (July, 1956), 408, 412-13, and "Cleveland's

Johnson:

Elected Mayor," 31-32, 38-41,

42fn., 43; Plain Dealer, April 2, 3, 1901, April 7, 8, 1903,

November 8, 1905; James B. Whipple,

"Municipal Government in an Average City: Cleveland,

1876-1900," Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, 62 (January, 1953), 1-24.

|

Downfall of a Progressive 29 |

|

|

|

ber. Herrick captured the statewide contest and topped Johnson by 4591 votes in the city, taking seventeen of twenty-six wards. As a result, the Republicans reasoned that a high-profile, well-supported candidate could un- seat the mayor in 1907. A significant voter registration increase, particularly in traditional Republican wards on the city's east side, was another cause for party optimism that "the latent anti-Johnson sentiment of the community" would defeat the mayor.17 The Republican nominee in 1907 was Congressman Theodore E. Burton, "one of the ablest and best-trusted men in the city."18 An expert on banking, monetary, and economic issues, and Chairman of the Rivers and Harbors

17. Cleveland Leader, September 11, October 21, 1907. For background on Johnson's statewide efforts, see Warner, Progressivism in Ohio, 119-42. 18. Paul Leland Haworth, "Mayor Johnson of Cleveland: A Study of Mismanaged Political Reform," Outlook, 93 (October 23, 1909), 469. |

30 OHIO

HISTORY

Committee, Burton represented the

progressive wing of the party. President

Theodore Roosevelt's personal choice to

oppose Johnson, Burton had gained a

reputation for high principles and

independence after clashing with the Marcus

Hanna political machine from 1902 to

1904. He and Johnson were hardly

strangers, having faced each other at

the polls on three previous occasions. In

1888 Burton defeated Johnson to capture

the Twenty-first District seat. Two

years later Johnson defeated Burton, and

served two terms before Burton re-

gained his seat in the Republican

landslide of 1894.19

Johnson and the Democrats understandably

made the street railway contro-

versy the issue of the 1907

campaign, and painted Burton as a representative

of big business, "privilege,"

and the Cleveland Electric Railway Company.20

Burton denied "any alliance or

other affiliation with any public service corpo-

rations, street railway or other."21

He questioned the practicality of three-cent

fares, proposing instead a temporary

rate of seven tickets for twenty-five cents

until October 1, 1908. Afterwards, an

independent commission would estab-

lish the lowest possible fare, one which

would provide sufficient funds for

improvements and expansion. If Concon

agreed to maintain this fare for at

least ten years, and to keep its books

open for inspection at all times, a

twenty-year franchise would be awarded

to the company. But this compro-

mise to end Cleveland's divisive

streetcar battle backfired on Burton. The

Johnson forces condemned him for

surrendering to the interests of Concon,

and on October 28 the company

unwittingly played into the mayor's hands

when it publicly announced its

acceptance of Burton's proposals. Despite his

efforts, Burton had become the

representative of the private street railway fac-

tion.22

As the campaign progressed, it also

became painfully obvious to the GOP

that its candidate was ill-suited as a

local campaigner. Burton was out of place

in the rough-and-tumble world of

Cleveland ward politics and, according to

Johnson, "exhibited a surprising

ignorance of local affairs."23 Burton was

unable to deal with the hecklers and rowdies

placed at his rallies by the

Johnson forces. In desperation he

questioned the competence of certain mem-

bers of the mayor's administration, but

only managed to create martyrs out of

those being attacked. Most damning to

his campaign was an awkward last-

19. Plain Dealer, November 8,

1888, November 6, 1890, November 9, 1892, November 7,

1894; Cleveland News, September

18, 1907; Forrest Crissey, Theodore E. Burton: American

Statesman, (Cleveland and New York, 1956), 132-37; Johnson, My

Story, 59-63, 74; Murdock,

"Cleveland's Johnson: The Burton

Campaign," 414-15; David D. Van Tassel and John J.

Grabowski, eds., The Encyclopedia of

Cleveland History, (Bloomington, Ind., 1987), 139-40.

20. Murdock, "Cleveland's Johnson:

The Burton Campaign," 416, 419.

21. Plain Dealer, September 4,

1907.

22. Electric Railway Review, November

2, 1907, 742; Haworth, "Mayor Johnson of

Cleveland," 473, (on the

questionable practicality of three-cent fares); Murdock, "Cleveland's

Johnson: The Burton Campaign," 419;

Plain Dealer, October 11, 1907.

23. Johnson, My Story, 271.

Downfall of a Progressive 31

minute mailing of a pamphlet attacking

Johnson's integrity. As the cam-

paign closed, Burton appeared to be a

pathetic, confused man.24

Although a Johnson victory was a

foregone conclusion by election day, the

magnitude of his triumph could hardly

have been expected. The mayor cap-

tured twenty of the city's twenty-six

wards, topping Burton by 9326 votes.

Despite the fact that his plurality was

2799 votes less than in 1905, this vic-

tory was far more impressive for a

number of reasons. In the eight strongly-

Democratic working class wards of the

west side, for example, Johnson had

defeated Boyd by 4871 votes in 1905,

winning over 59 percent of the total.

But in 1907, with 4643 additional voters

going to the polls in the west side

wards, Johnson beat Burton by 6782

votes, increasing his total to nearly 62

percent of the vote. On the

heavily-Republican east side, Johnson had de-

feated Boyd by 7261 votes in 1905,

capturing close to 56 percent of the total.

With the Republicans fielding a

formidable candidate in 1907, with an in-

creased turnout of over 10,000

additional voters in these wards, and without

the coattails of John Pattison to assist

him, the mayor could hardly have been

expected to win again on the east side.

Yet, he was victorious in twelve of

the eighteen wards east of the Cuyahoga,

winning over 51 percent of the total

vote, for a plurality of 2542 votes.

Additionally, in each of eight so-called

"debatable" wards, which the

Republicans felt confident of winning given the

significant voter registration

increases, Johnson emerged victorious. His total

margin over Burton in these wards was

3074, despite increased turnouts in

each, totalling 4295 over 1905. Finally,

counting the six "at large" council

seats, twenty-five of the thirty-two

city council members were now pro-

Johnson, three-cent fare advocates.25

Seeing the handwriting on the wall, Concon

entered into negotiations with

the city to resolve the streetcar

controversy. After numerous meetings be-

tween December 1907 and April 1908,

Concon and the low-fare companies

consolidated into a new entity, the

Cleveland Railway Company, which the

city granted a franchise. Municipal

Traction took control of Cleveland

Railway, with the understanding that

three-cent fares would be charged within

the city. The deal took effect on April

27, 1908, and all streetcars were free

of charge the following day, to

celebrate Tom Johnson's victory over

"privilege." But this

jubilation was short-lived, due to a labor impasse then

developing.26

24. Johnson, My Story, 271-72;

Murdock, "Cleveland's Johnson: The Burton Campaign,"

416-22.

25. Clemenson, "Political War

Against Tom Johnson," 260-79; Cleveland Leader, October

21, 1907; Plain Dealer, November

6, 7, 21, 1907. Wards 1-8 are west side wards; wards 9-26

are east side wards. According to an

article by John T. Bourke in the Cleveland Leader of

October 21, 1907, the

"debatable" wards were nos. 7, 9, 10, 15, 18, 19, 23, and 24.

26. Bemis, "Street Railway

Settlement in Cleveland," 549-50, 558-61; Bremner, "Street

Railway Controversy in Cleveland,"

194-97.

32 OHIO

HISTORY

Johnson's union troubles stemmed from

the fact that Cleveland's street

railway motormen and conductors were

working under two separate union

contracts. In 1906, Concon and Division 268 of the Amalgamated

Association of Street and Electric

Railway Employees of America signed an

agreement stipulating that first-year

workers would earn twenty-one cents per

hour, those in their second year would receive

twenty-three cents per hour, and

longer service workers would earn

twenty-four cents per hour. There was also

a clause in the agreement stating that

if the company signed a franchise re-

newal with the city prior to May 1,

1909, all workers would receive a two-

cent across-the-board pay increase. The

workers of the low fare lines, mean-

while, had been represented by Division

245 of the Association since 1906.

Their current contract, signed in

January 1907, called for an hourly rate of

twenty-three cents for the first year of

service, twenty-four cents the second

year, and twenty-five cents thereafter.27

The wage disparity was unacceptable to

both the Amalgamated Association

and the city, and each attempted to have

the contract most favorable to its re-

spective interests recognized as

binding. A.L. Behner, the Association's inter-

national vice-president, claimed that

the traction settlement constituted a

"franchise renewal" with the

city, and that all workers were entitled to the

two-cent per hour raise stipulated in

the renewal clause of Division 268's con-

tract. When efforts to merge the two

locals proved futile, Behner revoked

Division 245's charter in late April

1908. As a convenient excuse, he

claimed that a conflict of interest

existed, since many of the local's members

had purchased stock in Municipal

Traction.28

The city, meanwhile, saw the

Association's jurisdictional dispute as an op-

portunity to destroy Division 268.

Lowered fares meant decreased revenues,

and with the country suffering from a

business recession, strict economies

would have to be imposed on Municipal

Traction's operations. Getting rid of

over one thousand high-priced employees

would make this easier. The mayor

contended that Concon's agreement to the

two-cent raise was merely a cynical

effort to buy the support of the workers

in the company's battle with

Johnson, and on April 28 the city's

traction administrator, A.B. duPont, de-

clared Division 268's contract null and

void. DuPont offered the men only a

27. "The Cleveland Electric Ry. Co.

and Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric

Railway Employes [sic] of America

Division No. 268, Memorandum of Agreement, Cleveland,

O., December 22nd, 1906," Pamphlet

c1646, Western Reserve Historical Society, (WRHS),

Cleveland; Bremner, "Street Railway

Controversy in Cleveland," 198; Murdock, "A Life of

Tom L. Johnson," 384-85; Electric

Railway Review, May 9, 1908, 578; Street Railway Journal,

May 9, 1908, 796; Plain Dealer, April

29, 30, 1908; Cleveland Citizen, May 2, June 13, 1908.

The Citizen was the official

organ of the United Trades and Labor Council (UTLC). The June

13, 1908, edition carries the

"Report of the Grievance Committee on the Street Railway

Strike," hereafter cited as

"UTLC Grievance Committee Report."

28. Johnson, My Story, 280;

Murdock, "A Life of Tom L. Johnson," 386; Street Railway

Journal, May 9, 1908, 796; UTLC Grievance Committee Report.

Downfall of a Progressive 33

one-cent across-the-board pay increase,

to bring them in line with Division

245's pay scales, and rescinded the free

rides to and from work which they had

enjoyed under their old contract. When

the former Concon employees balked

at this offer, duPont began replacing

them with lower-paid, low-seniority

men.29

Angered by duPont's actions, members of

Division 268 voted to strike if

the matter was not resolved.30 On

Saturday, May 2, Behner informed duPont

and Johnson of the union's resolve, and

in the early hours of the following

day the three men finally agreed that a

three-member arbitration board would

be named to make a binding decision on

the validity of Division 268's con-

tract. On May 4 the members voted to

accept this proposal. DuPont and

Johnson then began to stall for time.

The mayor conveniently left town,

while duPont continued to discharge the

old Concon men and place members

of Division 445 on the favored runs. On

May 12 the parties finally agreed on

the membership of the arbitration board,

with the first meeting scheduled for

May 15.31

According to the union, duPont and

Johnson then "displaced over 150 old

men, some of them having been 14 and 15

years in the service, placing them

back upon the extra list, and putting

new men on their runs. They had also

discharged up to this time over 100 old

employes [sic]."32 The union further

contended that "the officers of the

company had been holding meetings at the

various barns seeking to discredit the

officers and committeemen and divide

and destroy the organization. On the

very day on which the arbitration

agreement expired [May 15] the company

discharged 27 old employes [sic]."33

Municipal Traction again offered

arbitration, but Behner, by now convinced

"that the company is planning to

break up the union," refused. Two separate

meetings took place on Friday evening,

May 15, at the United Trades and

Labor Council (UTLC) headquarters. The Plain

Dealer reported that "violent

debate" grew out of a wide range of

issues, including "wages, seniority rights,

[and the] open shop." The speech of

one disgruntled member summed up the

desperation of Division 268's

rank-and-file:

I know, you all know, they are going to

fire us all. They are going to fire me, as

soon as they get around to it. We are

all going to be fired anyhow in the end.

Let's get out now and make a fight for

our rights before we are kicked out. I vote

we strike at once.

29. Bremner, "Street Railway

Controversy in Cleveland," 197-98; Electric Railway Review,

May 9, 1908, 578; Murdock, "A Life

of Tom L. Johnson," 386; Street Railway Journal, May 9,

1908, 796; UTLC Grievance Committee

Report.

30. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 386-87.

31. Street Railway Journal, May

16, 1908, 833-34; UTLC Grievance Committee Report.

32. UTLC Grievance Committee Report.

33. Ibid.

34 OHIO HISTORY

Thirteen hundred-fifty of this man's

union brothers agreed, and voted "almost

unanimously" to walk out, effective

at 4:45 A.M. on Saturday, May 16.34

Despite duPont's assurance that the

"cars will run as if there were no

strike,"35 the walkout

of Division 268 inaugurated a week of violence and dis-

ruption. Strikers and their sympathizers

stoned streetcars, cut electric wires,

laid trees across tracks, destroyed

switches, and beat non-striking workers.

The city hired two hundred extra police,

but the remainder of the week was

characterized by arson, shootings,

dynamitings, and the death of a four-year-

old girl crushed under the wheels of a

streetcar.36

On Sunday, May 17, the Association's

international president, W.D.

Mahon, arrived in Cleveland to help

resolve the impasse. Despite assurances

from the Ohio State Board of Arbitration

that the mayor was anxious for a

meeting, Johnson flatly refused to talk

with any union officials. Mahon then

proposed that an arbitration board be

set up to rule on the legitimacy of

Division 268's contract, the cases of

all discharged workers, and discrimina-

tion against high-seniority men. DuPont

refused to meet with the union un-

til "all lawlessness and disorder

has ceased," and further declared that seniority

rights would not be considered under any

circumstances. He then relented, of-

fering to submit all questions to an

arbitration board, providing the men re-

turned to work and waived their

seniority rights pending the board's decision.

The strikers voted to accept this

proposal.37

Meanwhile, however, the conflict had

begun to shift in the city's favor. By

Friday, May 22, most violence had ended

and a number of men had returned to

work. DuPont decided to take a hard line

with the union. He argued that

since the arbitration of Division 268's

seniority rights would affect the work-

ers of both locals, it was only fair to

allow the members of Division 445 to

decide whether arbitration should take

place. Naturally, the Division 445

workers voted overwhelmingly against

arbitration of their seniority and this,

essentially, was the end of the strike.

On May 25 duPont announced that all

Division 268 members who reported for

work by 6:00 P.M. the following

day would be considered for

reemployment. But the company turned down

most of those who bothered to reapply,

and over one thousand strikers lost

their jobs.38

Given Tom Johnson's reputation for

empathy with the laboring classes, it

34. Plain Dealer, May 15, 16,

1908.

35. Plain Dealer, May 16, 1908.

36. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 387-91.

37. "To the People of

Cleveland," typed statement of A.B. duPont, May 21, 1908, A.B.

duPont Papers, Mss. A, D938, folder 7,

Filson Club, Louisville, Ky.; UTLC Grievance

Committee Report.

38. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 391-92; Electric Railway Review, May 30, 1908,

660; Street Railway Journal, May

30, 1908, 918; Plain Dealer, May 25, 26, 1908. The number

of men who lost their jobs is an

estimate, since it is unknown how many of the original 1350

strikers went back to work during and

immediately after the strike.

Downfall of a Progressive 35

is tempting to blame duPont for the

city's inflexibility. Eugene C. Murdock,

for instance, cites duPont's broken

promises and tactlessness as evidence that

he "thirsted for the fight, and

basked in his victory."39 But duPont, an inno-

vative railway administrator of national

reputation, had long enjoyed amicable

relations with organized labor. When

duPont left his post as general manager

of Detroit's Citizens' Company line in

1901 to accept a similar position in

St. Louis, the Amalgamated Association

sponsored a testimonial dinner in

his honor, prompting the Detroit News

to exclaim that duPont would "never

be more popular with the street railway

men in St. Louis than he had been in

Detroit."40 DuPont and

the mayor were close friends and longtime business

associates since Johnson's early days in

Louisville. The pair met daily for a

morning conference, lunch, and dinner,

and it is inconceivable that duPont

acted without Johnson's knowledge and

direction. DuPont's loyalty and devo-

tion to the mayor made him "not

only willing, but eager, to assume all un-

popular acts which seemed

necessary" in implementing Johnson's programs,

in this case the suppression of the

union.41

Mayor Johnson, apparently confident that

duPont would defeat the strike,

had remained uncharacteristically

passive throughout the ordeal. When direct

intervention would likely have prevented

injuries and destruction of property,

he maintained a low profile, refusing to

meet with union officials and spend-

ing much of his time perfecting a new

coin box to accommodate three-cent

fares.42 But his response to

the strike was also true to the form he had exhib-

ited in Detroit a decade earlier.

Johnson could be ruthless when dealing with

threats to his success. The motormen and

conductors of Division 268 bore

the brunt of this ruthlessness.

In fairness to Johnson, it must be

emphasized that he was not anti-union

and had no quarrel with working-class

movements. As a congressman

Johnson had supported the eight-hour day

for federal employees and con-

demned police brutality against Coxey's

Army in 1894.43 Samuel Gompers

commented that while in Congress

"Mr. Johnson always expressed a friendly

feeling to our cause and was favorable

to the measures in which labor was in-

39. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 392-93.

40. Undated clipping, A.B. duPont

Papers, Filson Club, folder 1.

41. "The Forest City Railway

Company, new sale of stock, Statement by Mayor Johnson,

Issued by The Municipal Traction

Company, Superior Building, Cleveland, O.," n.d., Tom

Johnson Vertical File, WRHS; Hauser,

"A.B. duPont-An Appreciation," reprint of article

originally published in The Public, June

28, 1919, n.p., A.B. duPont Papers, Filson Club, folder

3; "Around the Clock with a Human

Steam Engine," and "A.B. duPont's Daily Dose," uniden-

tified clippings, ca. 1908, scrapbook in

A.B. duPont Papers, Filson Club, folder 17. For Tom

Johnson's connections with Louisville

and the duPont family, see Chandler and Salsbury, Pierre

S. duPont, 25-28, "Louisville Scenes," 11-12, and My

Story, 9-14.

42. Hauser, introduction to Johnson, My

Story, xxii; UTLC Grievance Committee Report.

43. Warner, Progressivism in Ohio, 71,

83fn., citing Rawlinson, "Tom Johnson and His

Congressional Years," 64, 105.

36 OHIO

HISTORY

terested."44 Johnson's

steel workers received higher wages than employees of

his major competitors, and even during

economic slumps he refused to enact

layoffs. When, on the eve of the 1907

election, a committee of Cleveland

trade unionists supporting Theodore

Burton condemned Johnson for allegedly

thwarting unionization and running

"the dirtiest scab mills in America," a

former employee came to the mayor's

defense, claiming that Johnson had

never discouraged unionization at the

Johnstown plant, and on one occasion

had even provided the company's

facilities for an organizer to hold a meet-

ing.45

One need look no further than the

Cleveland streetcar workers themselves

for evidence that the mayor was not

anti-labor, for the men of Division 445

met no resistance in their organizing

efforts of 1906, and enjoyed rates of pay

exceeded by only a few railway locals in

the country. Johnson campaign lit-

erature boasted that "there has

never been a strike on any railroad lines with

which Mr. Johnson has been

connected."46 When asked about the high wages

and good conditions granted to his steel

and railway employees, Johnson ex-

plained, "I did not do that because

I loved the men. I did it because I thought

it was the best thing for the

company."47 Johnson biographer Carl Lorenz

summed up this attitude by commenting

that Johnson "favored labor unions

as long as they did not interfere with

the success of legitimate business."48

Johnson apparently saw Division 268 as

just such an "interference." Given a

mandate to implement a three-cent line,

the mayor may have considered the

elimination of the union necessary.

Despite the boasts of one Johnson

cabinet member that "the strikers were

utterly defeated, and the union has gone

to pieces,"49 the outcome of the con-

flict was a dubious victory for Johnson.

The disruption of the strike and the

use of inexperienced replacement

motormen and conductors caused poor ser-

vice, alienating much of Municipal

Traction's ridership. Accompanying this

loss of business were the expenses

incurred through the destruction of prop-

erty. Expecting a profit of $40,000 for

the month of May, the company in-

44. Plain Dealer, November 1, 1907, citing a letter from Gompers to A.B.

Crutch, Secretary

of the UTLC Political Committee, October

17, 1907.

45. Massouh, "Technological and

Managerial Innovation," 61, 62; Plain Dealer, November

3, 1907; "To the Workingmen of the

City of Cleveland," Pamphlet c838, n.p., WRHS.

46. "Manager duPont's

Statement," June 6, 1908, in UTLC Grievance Committee Report;

"Tom L. Johnson's Past Utterances

on Present Issues: Three Cent Fares and Other Municipal

Questions, Cleveland, March, 1901,"

3, Tom Johnson Vertical File, WRHS.

47. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 306, citing Plain Dealer, March 14, 1901.

48. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 306, citing Carl Lorenz, Tom L. Johnson: Mayor

of Cleveland, (New York, 1911), 85.

49. Bemis, "Street Railway

Settlement in Cleveland," 572. Edward W. Bemis was

Cleveland's Water Works Superintendent

and one of Johnson's most important advisors. See

Murdock, "Cleveland's Johnson: The

Cabinet," Ohio Historical Quarterly, 66 (October, 1957),

386-88.

Downfall of a Progressive 37

stead lost over $50,000.50 More

importantly, the workers who had lost their

jobs were eager to strike back at the

mayor and desperate to regain employ-

ment. The opportunity to achieve these

goals came in the form of the

Schmidt Act, a state law passed earlier

in 1908 stipulating that fifteen percent

of the electorate could petition for a

referendum on public franchise grants.

As the strike died out in late May, the

men of Division 268 collected 23,000

signatures, 9000 more than required.

They reasoned that the referendum

would embarrass the mayor regardless of

the outcome, and that a defeat of

Municipal Traction might lead to a

return of Concon, and their jobs. Despite

earlier support for the Schmidt bill,

Johnson challenged the petitions and used

delaying tactics to prevent the public

from voting, thus disillusioning many

of his closest supporters. When the

referendum finally took place on October

22, 1908, Clevelanders voted to rescind

Municipal Traction's franchise grant,

38,249 to 37,644.51

Although ostensibly a referendum on the

city's streetcar system, the vote

was nothing less than a rejection of

Johnson. The nucleus of strikers, led by

Behner, had joined forces with the

Republican-sponsored Citizens Referendum

League to create a formidable, if

improbable, anti-Johnson coalition.52 The

mayor had long relished the animosity of

the city's business establishment,

but his poor judgement in handling the

strike had now begun to erode his

support among Cleveland's working class,

as illustrated by Johnson's show-

ing on the west side. After winning all

eight wards in 1907 with nearly 62

percent of the vote, the mayor lost

outright in three wards, and slipped to 53

percent of the total. This was not

nearly enough to offset the expected losses

on the east side.53 In light

of the 1907 Johnson landslide, the referendum rep-

resented a stunning defeat for the

mayor.

The administration charged that the striking

conductors and motormen had

been paid by "interested parties,

in printing literature and actively canvassing

against the Traction Company."54

It claimed that large sums of money had

been provided by former Concon

stockholders, the Cleveland Electric

Illuminating Company, and streetcar

interests throughout the country, and

even that the May strike itself had been

planned and financed by anti-Johnson

business interests. Johnson's followers

contended that the public had been

misled, since the local newspapers were

supposedly under the control of

50. Clemenson, "Political War

Against Tom Johnson," 172, citing figures from The Public,

July 3, 1908, 324; Johnson, My Story,

281.

51. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 395-99, 404-06; Lorenz, Tom L. Johnson, 171-

72; Plain Dealer, October 23,

1908.

52. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 404-06.

53. Plain Dealer, October 23,

1908.

54. Bemis, "The Cleveland

Referendum on Street Railways," Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 23 (November, 1908), 179.

38 OHIO HISTORY

"privilege."55 Citing

alleged irregularities in precincts where voting ma-

chines were used, one of the mayor's

assistants went so far as to claim that

"thousands appear to have voted

against the franchise who thought they were

voting to sustain the Mayor and his

policy."56 These charges ignore a more

compelling explanation of the outcome of

the referendum: the men simply

wanted their jobs back. They had been

denied their livelihoods, and the refer-

endum was their last recourse. The

people of Cleveland, meanwhile, used the

referendum to voice their disapproval of

Tom Johnson's handling of the trac-

tion situation. It is undeniable that

business interests subsidized the cam-

paign against the franchise grant, and

quite plausible that they extended finan-

cial assistance to the men during the

strike. But to paint the strikers as un-

thinking pawns in the hands of evil

monopolists, and to portray the public as

easily-manipulable and too ignorant to

read a ballot correctly, was an affront

to the intelligence of the very people

whose cause Johnson had long champi-

oned.

In the wake of the referendum, Municipal

Traction went into receivership,

under the direction of the Federal

Circuit Court. As a result, the Depositors'

Savings and Trust Company, a bank

organized by Johnson in 1906 to finance

Municipal Traction and facilitate the

sale of stock, immediately failed, caus-

ing hundreds of stockholders to lose

their investments. Meanwhile the re-

ceivers, anxious to make peace with

Division 268 and concerned over the

poor service plaguing the system,

announced on November 18 that they

would give the strikers preference in

filling job vacancies. Three days later

A.L. Behner declared that "our

fight was on the Municipal. The receivers

have met us in a spirit of fairness, and

we are glad to cooperate with them."

The union members voted to accept the

conditions, and the streetcar strike of-

ficially ended on November 21, 1908.57

Despite his defeat Tom Johnson

stubbornly continued the crusade for three-

cent fares. A referendum election held

on August 3, 1909, asked whether an

east side franchise should be granted

to the mayor's friend, Herman Schmidt.

By this time even many of the mayor's

longtime political supporters ques-

tioned his sincerity in serving the

city's interests, while the normally sympa-

thetic Plain Dealer criticized

Johnson for "a spirit of obstinacy and narrowness

that is far from agreeable to

contemplate."58 Anti-Johnson, pro-business

forces, officially known as the

"Citizens Committee of 100," waged a spir-

55. Bremner, "Civic Revival in

Ohio," 199; Howe, Confessions of a Reformer, 125; Johnson,

My Story, 282.

56. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," citing Bemis, "Cleveland Referendum on Street

Railways," 182.

57. Hayden, "Street Railway

Situation in Cleveland," 412-13; Lorenz, Tom L. Johnson, 177;

Johnson, My Story, 265; Murdock,

"A Life of Tom L. Johnson," 413-15; Plain Dealer,

November 19, 22, 1908.

58. Plain Dealer, August 1, 1909.

Downfall of a Progressive 39

ited, well-financed campaign against the

ordinance, and succeeded in defeating

the Schmidt grant, 34,785 to 31,022. The

low turnout was a disappointment

to the Johnson administration, which had

expected at least 85,000 voters to

participate. The lack of interest was

particularly pronounced on the city's

west side. Wards One through Eight gave

the grant a slim majority of 1740

votes, but Johnson had anticipated a

margin of three to four times that. As in

the 1908 referendum, the west side

plurality was not nearly enough to offset

the Republican wards on the east side.

In one particularly-strong GOP ward

the Schmidt franchise lost by 2121

votes, 381 more than the entire pro-

Johnson west side margin.59

With his traditional base of support

crumbling and his prestige at low ebb,

Tom Johnson was obviously ripe for

defeat in the November 1909 mayoral

election. To oppose him the Republicans

chose the "weak and colorless"

Cuyahoga County recorder, Herman Baehr.60

A brewer by trade, Baehr had a

strong following on the west side, which

was heavily populated by his fellow

German-Americans. The party reasoned

that Baehr could take advantage of

Johnson's decreasing strength on the

west side, while winning easily on the

east side. In contrast to 1907, Johnson

avoided the street railway controversy,

campaigning instead on a tax reform

platform, while stressing his administra-

tion's achievements over the past eight

years. Baehr, meanwhile, said little

of substance and avoided controversy. He

ignored Johnson's calls for public

debate, and knowing that the east side

was safely Republican, did most of his

campaigning on the west side.61

Baehr defeated Johnson by 3694 votes,

winning fifteen of twenty-six wards,

including three of the eight west side

wards. The Republicans also took

twenty-five of the thirty-two council

seats, as a number of pro-Johnson in-

cumbents lost. The Plain Dealer described

the results as a case of the mayor's

streetcar troubles "frightening his

friends and driving his opponents to the

polls." This was particularly true

on the west side, where the Republican

candidate's popularity "cut the

heart out of Johnson's strength on Baehr's side

of the city." With 1242 fewer west

siders going to the polls than in 1907,

the mayor's 6782-vote west side majority

in the Burton election shrunk to a

mere 1052 votes in 1909. This was not

nearly enough to offset the expected

huge losses on the east side, where

Baehr crushed Johnson by 4746 votes.62

59. Cleveland Press, August 4,

1909; Johnson, My Story, 288; Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 417-19; Plain Dealer, August

3, 4, 1909.

60. Carol Poh Miller and Robert Wheeler,

Cleveland: A Concise History, 1796-1990,

(Bloomington, Ind., and Indianapolis,

1990), 108.

61. Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 424-28; Plain Dealer, November 1, 1909; Van

Tassel and Grabowski, Cleveland

Encyclopedia, 65. Johnson's attempt to downplay the street-

car issue and instead promote tax reform

is apparent in 1909 campaign literature in the Tom L.

Johnson Vertical File at the Western

Reserve Historical Society, and the A.B. duPont Papers at

the Filson Club.

62. Clemenson, "Political War

Against Tom L. Johnson," 270-79, 291-302; Cleveland

|

40 OHIO HISTORY

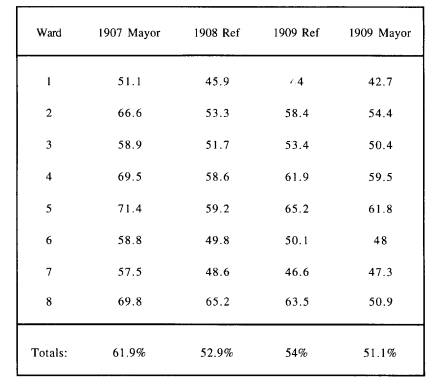

Johnson's defeat was not an example of labor punishing its enemies. There is no evidence of a union campaign to "get" the mayor in any of Cleveland's newspapers, including the Citizen, published by the UTLC. Labor's Political League did refuse to endorse the mayor in 1909, citing Johnson's "unwarranted stand against the street railway men's union."63 But Johnson had never enjoyed strong support from organized labor; the UTLC, wary of the mayor's business background, usually backed a Socialist candidate for city hall. The shift away from Johnson was more subtle, marked by an increasing loss of support in the traditionally pro-Johnson, working class wards of the west side. This is illustrated by the mayor's west side vote percentages in his final four municipal elections: |

|

|

|

After winning almost 62 percent of the vote in 1907, Johnson slipped to 53 and 54 percent in the referendums of October 1908 and August 1909, respec- tively. In the 1909 Baehr election, Johnson garnered only 51 percent of the

Leader, November 4, 1909; Plain Dealer, November 3, 1909. 63. Plain Dealer, October 31, 1909. |

Downfall of a Progressive 41

vote, his lowest total west of the

Cuyahoga since the loss to Governor

Herrick in 1903. Tom Johnson's

supporters had obviously grown tired of the

street railway controversy.

The strike was central to this

development. Prior to May 1908 the traction

issue had been a catalyst for Johnson's

electoral support, as shown by his

huge vote totals in 1907. But the

strike, by itself quite damaging to the

mayor's prestige, set in motion a series

of events which killed this enthusi-

asm in only a few months. The

mistreatment of the strikers led to the peti-

tion drive and a referendum which would

not otherwise have taken place; the

mayor's awkward attempts to invalidate

the petitions disappointed many of

his closest friends; the loss of one

thousand experienced men caused poor

transit service, angering riders and

providing ammunition to Johnson's critics;

the expenses of repairing and replacing

property damaged in the strike put

added strain on a system already

strapped for revenue, hindering service even

further; and the failure of the

Depositors' Savings and Trust Company caused

hundreds of the mayor's strongest

supporters to lose money.64

In his eight-year battle with

"privilege," that amalgam of industrialists,

bankers, and crooked politicians

supposedly intent on destroying him, Tom

Johnson portrayed himself as a champion

of the common people. But his

mistreatment of the motormen and

conductors of Division 268 exposed the

mayor as a cynical elitist, convinced he

knew what was best for the people of

Cleveland, and determined to realize his

dream of three-cent transit. It was the

misfortune of the strikers to

unwittingly get in the way of this dream. The

irony is that these working class men

accomplished with petitions what

"privilege," with all of its

money and power, could not. And that was Tom

Johnson's misfortune.

64. Haworth, "Mayor Johnson of

Cleveland," 471-72; Lorenz, Tom L. Johnson, 171-72;

Murdock, "A Life of Tom L.

Johnson," 399-403.

ARTHUR E. DeMATTEO

The Downfall of a Progressive: Mayor

Tom L. Johnson and The Cleveland

Streetcar Strike of 1908

On November 6, 1907, Cleveland Mayor Tom

L. Johnson awoke to head-

lines announcing his landslide triumph

in the previous day's municipal elec-

tion. Democrat Johnson, the champion of

progressive urban reform and pub-

lic control of utilities, had solidified

his position as the city's most powerful

politician by crushing the best

candidate the Republican Party could offer.

The vote was a referendum on the mayor's

six-year crusade for low streetcar

fares, and the Cleveland Plain Dealer

reported that"the victory of Mayor Tom

and 3-cent fare was complete."1

Johnson immediately declared his intention

to run for a fifth term two years hence,

and appeared to desire nothing more

than leadership of the Ohio Democratic

Party. But the mayor's impressive

reelection had attracted national

attention, and some party luminaries, notably

House Democratic leader Champ Clark,

began to eye Johnson as a possible

1908 presidential alternative to the

twice-rejected William Jennings Bryan.2

A series of mishaps and miscalculations,

centered around Cleveland's street

railway situation, soon eclipsed the

promise of that autumn morning. The

1907 victory was Johnson's last, and

within two years he lost city hall to a

political lightweight, the victim of a

reversal in fortune more dramatic than

any in the city's history. Robert H.

Bremner has described Tom Johnson as

"greedy for affection and greedy

for accomplishment."3 In the months follow-

ing the election these characteristics,

manifested in a single-minded determina-

tion to push through his streetcar

reforms, set the mayor on a collision course

with Cleveland's unionized transit

employees. The ensuing strike of 1908 ru-

ined Johnson's political career and

probably hastened his death.

Arthur E. DeMatteo is a Ph.D. candidate

in American labor history at the University of

Akron. He wishes to thank Professors

Daniel Nelson and James F. Richardson for reading

earlier drafts of this article and

providing helpful criticisms and suggestions.

1. Cleveland Plain Dealer, November

6, 1907.

2. Ibid., November 11, 22, 1907; New

York Times, November 8, 9, 1907.

3. Robert H. Bremner, "The Civic

Revival in Ohio: The Fight Against Privilege in Cleveland

and Toledo, 1899-1912" (Ph.D.

diss., Ohio State University, 1943), 46.

(614) 297-2300