Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

KIM M. GRUENWALD

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern in the Ohio Country: A

Reinterpretation

As historians of the Early Republic,

scholars of the Progressive era created

a long-lasting, influential school of

interpretation for the decades following

the American Revolution. The Progressive

school focused on the conflict be-

tween common men who favored local

control and an elite which favored

strong central authority-as they deemed

it, the forces of democracy versus

the forces of aristocracy. The Old

Northwest provided a perfect arena for these

historians to test their hypotheses.

Following in the footsteps of Frederick

Jackson Turner, they described how the

forces of the common man developed

as Americans spread through the new

territories in the Old Northwest. In The

Civilization of the Old Northwest: A

Study of Political, Social, and

Economic Development, 1788-1812, Beverley Bond described the new region

as the laboratory where Americans first

experimented with democracy. Settlers

took colonial ideas about law,

government, and society with them. But once

they were in the West, they adapted to

their new life in the wilderness,

dropped conventional ideas that no

longer served their needs, and developed

egalitarian institutions. In Valley

of Democracy: The Frontier versus the

Plantation in the Ohio, 1775-1818, John D. Barnhart followed up on Bond's

work, focusing even more narrowly on the

Ohio Valley to show how the

frontier produced American democracy.1

Marietta, Ohio, occupied a peculiar

place in this historiography of the Early

Republic-a place which relegated the

town's story to a peripheral role within

the Progressive school's lexicon. The

town was settled in 1788 by the Ohio

Company, a group of New England

Revolutionary War veterans and their as-

sociates. Historians wrote that

Marietta's settlers recreated a New England vil-

lage in the wilderness. Composed chiefly

of those who adhered to

Federalism, Mariettans seemed too

different from the pioneer farmers inhabit-

ing the rest of the state to be

considered typical. Thus, although Marietta's

Kim M. Gruenwald is Assistant Professor

of History at Kent State University.

1. John D. Barnhart, Valley of

Democracy: The Frontier versus the Plantation in the Ohio

Valley, 1775-1818 (Bloomington,

Ind., 1953); Beverley W. Bond, Jr., The Civilization of the Old

Northwest: A Study of Political,

Social, and Economic Development, 1788-1812 (New York,

1934).

126 OHIO

HISTORY

status as the first permanent

Anglo-American settlement in the Old Northwest

assured its place in American history,

many historians moved further west to

the history of the Scioto and Miami

Valleys, feeling their stories were more

representative of the history of the

settlement of the Ohio country. The tradi-

tional story presented Marietta as a

stronghold of Federalism in early Ohio

that faded from significance quickly as

Jeffersonian Republicans wrested con-

trol of the territory from them. For

most historians, Marietta's traditional

place in history remained unchanged even

while the history of the Old

Northwest itself evolved.2

Recent historians have reinterpreted the

story of the struggle between East

and West between 1795 and 1820. In The

Frontier Republic: Ideology and

Politics in the Ohio Country,

1780-1825, Andrew Cayton stressed that

while

the antifederal and Jeffersonian

localists of the Miami and Scioto Valleys

eventually won out in the political

struggle to define Ohio's character, they

were never precisely egalitarian as the

Progressives had maintained. The

Jeffersonian Republicans resented the

hold Ohio Federalists and Arthur St.

Clair attempted to keep over the

settlement of the Ohio Valley, but they were

far from poor, simple farmers. The

controversies of the Early Republic in the

West, he argued, had less to do with

competing class interests than with is-

sues of home rule: in other words, the

competition involved localism versus

nationalism.3

But despite the evolution of the

historiography of the Old Northwest, one

question has remained unanswered. With

such conflict dividing Ohio localists

from the metropolitan leaders of the East,

how did the Ohio Valley ever be-

come part of the Union? The answer lies

in the history of the town that the

Progressive historians deemed unique and

outside the mainstream of the his-

tory of the Old Northwest-the history of

Marietta, Ohio.

From a political standpoint, Mariettans

did sink into the background of

Ohio's history, but Marietta itself

survived, evolved, and grew, even if it

never rivalled the size and strength of

Cincinnati, Cleveland, or Columbus

(but, of course, few Ohio towns did).

But it is precisely because Marietta's

founders had at least half of their

intentions grounded in old, colonial views

that a historian can discern the more

successful strategies of those who ac-

2. Reginald Horsman, The Frontier in

the Formative Years, 1783-1815 (New York, 1970),

36-42, 75; Malcolm J. Rohrbough, The

Land Office Business: The Settlement and

Administration of American Public

Lands, 1789-1837 (New York, 1968),

48-49, 119-20; Robert

E. Chaddock, Ohio Before 1850: A

Study of the Early Influence of Pennsylvania and Southern

Populations in Ohio (New York, 1908); bibliographical essay in Andrew R.L.

Cayton, Frontier

Republic; Ideology and Politics in

the Ohio Country, 1780-1825 (Kent,

Ohio, 1986), 181;

Cayton, "Marietta and the Ohio

Company," in Appalachian Frontiers: Settlement, Society, &

Development in the Preindustrial Era,

ed. by Robert D. Mitchell (Lexington.

Ky., 1991), 187-

88; Don Harrison Doyle, The Social

Order of a Frontier Comunity: Jacksonville, Illinois,

1825-70 (Urbana, Il1., 1983), 23-38.

3. Cayton, Frontier Republic.

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern 127

companied the leaders of the Ohio

Company to the confluence of the

Muskingum and Ohio Rivers. The

nationally-oriented patronage system of

the Federalists failed, but that failure

stands in contrast to and highlights the

successful links to the East forged by

the merchants who came with Rufus

Putnam and his followers to the Ohio

Valley.

The story of Marietta as a town whose

past provides a window into the his-

tory of the Old Northwest must begin

with the plans Rufus Putnam and the

Ohio Company had for the Ohio Valley.

These plans went far beyond trans-

planting a New England town in the

wilderness, and thus they attracted many

different types of settlers. Founding

Marietta proved difficult, but after ban-

ishing the Native Americans who lived in

the Ohio Valley, Anglo-American

settlement exploded. In establishing the

community, Mariettans utilized two

different kinds of networks-one based on

the patronage of the federal gov-

ernment and one based on credit

relationships between local merchants and

others. When the Federalists lost

control of the national government, it was

the second type which allowed Marietta

to survive and grow.

I

By 1770 the fertile land on the banks of

the Ohio were well known to

would-be American settlers, especially

on the southern side of the valley.

Squatters with no legal claim moved

north of the Ohio River during and after

the Revolution, and by 1785 some 300 lived

along the Muskingum, 300

along the Hocking, 1500 along the

Scioto, and 1500 along the Miami. The

army tried to uproot squatters in the

late 1770s in an effort to keep the

Delaware Indians neutral in the

Revolutionary War. In 1785, after the war,

they erected Fort Harmar at the mouth of

the Muskingum to control squatting

and to secure the Ohio country for the

newly formed United States.4

The Confederation displayed keen

interest in the Ohio country for strategic

reasons, but government leaders also

hoped land sales there would help offset

the young nation's debts. Members of

Congress and leaders such as George

Washington believed that the Ohio

squatters posed a threat to their plans to

create an orderly society capable of

securing the Revolution and the new

Republic. Congressional leaders deemed

the squatters too individualistic and

selfish to make good citizens. They

feared the squatters would be easily sub-

verted by British or Spanish agents,

making them a threat to security.

Congress decided to use force to evict

settlers, burning their cabins, but found

the task an impossible one.5

4. Archer Butler Hulbert, "The Ohio

Company," in The Records of the Original

Proceedings of the Ohio Company, ed. by Hulbert (Marietta, Ohio, 1917), xxi-xxiii.

5.

Cayton, Frontier Republic, 2-11.

128 OHIO HISTORY

Because of the attempts by the army to

control the banks of the Ohio, the

Ohio Valley was as well known to the

military as to the squatters them-

selves, and army officers knew the lands

were rapidly being settled. In

September of 1783 while stationed with

Washington's army at Newburgh on

the Hudson, a group of Continental

officers began to formulate plans of their

own for making use of the Ohio Valley-plans

that did not include letting it

fill up with squatters. Led by Brigader

General Rufus Putnam, these officers

petitioned Congress to grant the land to

them in the tradition of military

bounty lands. Putnam argued in the

petition and elsewhere that by allowing

his group to set up a permanent

settlement on the Ohio, the new American

government would gain a buffer against

the British and the Spanish, as well

as providing communication between the

East and the West through the Great

Lakes. Putnam emphasized that if

settlement was not carried out in an or-

derly fashion, a European power might

gain control of the area. Nearly all

the petitioners, as members of the

Society of Cincinnati, intended to make

their settlement a bulwark of the

authority of the federal government in the

West.6

When their push for their bounty lands

met with no success, Rufus Putnam

and some of his associates created the

Ohio Company in 1786. Set up as a

joint-stock company, instead of

requiring military service to obtain land, it

gave membership to those who could

purchase a share of stock for $1000 in

continental securities or $10 in gold.

This allowed men to turn depreciated

securities into profit-land. They

limited the number of shares a person

could buy to five to insure that

professional speculators could not cash in-

thus preserving the speculative

advantage for themselves.7

The federal government agreed to sell

land to the Ohio Company because

Congress believed that the Ohio

Company's plans would further the national

interest and provide for a systematic

settling of the West. Those who would

be labelled Federalists in a very few

years regarded the interior as a place they

could mold into an asset to the new

nation. They wished to settle the trans-

Appalachian region not with the

squatters who grew corn, lived in cabins, and

hunted in the woods, but with farmers

bent on improving the land and estab-

lishing communities. To accomplish this

aim, Congress gave control of the

Ohio country to "gentlemen of the

proper persuasion," who would establish

system and order on the banks of the

Ohio.8

Neither Putnam nor his associates

envisioned an egalitarian society; they

expected their ties to the national

government to secure their own individual

social status. Most of the prominent

members of the company had lost capi-

6. Hulben, "The Ohio Company,"

xxvi-xxx, xl-xlii.

7. Timothy J. Shannon, "The Ohio

Company and the Meaning of Opportunity in the

American West, 1786-1795," New

England Quarterly, 64 (September, 1991), 396-97, 402.

8. Cayton, Frontier Republic, 13-25.

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern 129

tal during the war, and in the social

chaos that followed the Revolution. In

some ways, they wanted to recreate the

more orderly world they had known

before the war. Joseph Gilman of New

Hampshire was one such man.

Chaotic currency conditions after the

Revolution and the decline in the value

of state securities caused Gilman to

lose much of his property in the late

1780s. He had been a creditor to his home

state during the Revolution, pro-

viding troops with clothing and

blankets, but he could not collect on many of

these debts after the war, and his

economic status collapsed. Gilman intended

to make a new start in the West, away

from the eyes of his neighbors who

had witnessed his ruin. Rufus Putnam

himself sought an increase in status;

appointed Surveyor General of the United

States, and as one of the directors of

the Ohio Company, Putnam would control

the patronage system in what

would become Washington County, Ohio.9

But Putnam's plans also attracted men

very different from Gilman.

Recently one historian has explored

other facets in the Ohio Company's plans

for the region. Rufus Putnam envisioned

an urbanized West fully integrated

into the Atlantic community and economy.

Putnam's West would have an

interdependent relationship with

Atlantic culture and society, rather than an

independent one. But the Ohio

settlements would be no mere colony of the

East. Putnam planned to promote manufactures

in his scheme. Churches and

schools would provide social control.

The as-yet-unnamed city of Marietta

was to be the hub of western commercial

and cultural exchange with the East.

Putnam and others planned the city on a

grid. They knew that farmers would

provide the economic base of western

society, but wanted them to support ur-

ban areas of manufactures and commerce.

Putnam envisioned a complex,

economically diverse society in the

West, not an agrarian paradise.10

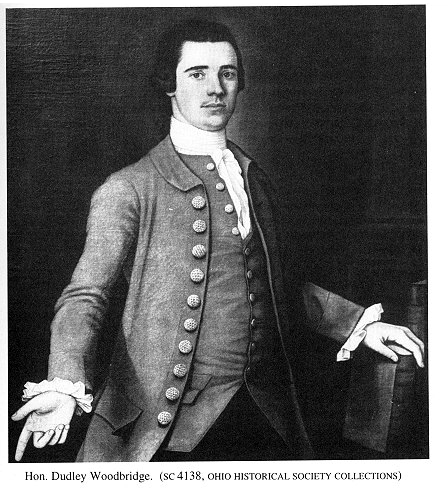

Although he never became a stockholder,

Dudley Woodbridge was one man

who found himself attracted to this

vision of the Ohio Company. Born in

1747, Woodbridge moved to Norwich,

Connecticut, in 1770, established

himself as a lawyer, married the

daughter of a prominent iron manufacturer,

and turned to mercantile pursuits soon

thereafter. In the years following the

Revolution, Connecticut merchants found

their path to the West Indies

blocked by the English, and Woodbridge

decided to find an alternate route to

the Atlantic world down the Mississippi

through New Orleans.11

9. Ibid., 16, 26, 34, 49; Mrs. Charles

P. Noyes, ed., A Family History in Letters and

Documents, 1667-1837 (St. Paul, Minn., 1919), 155; S.P. Hildreth, Biographical

and Historical

Memoirs of the Early Pioneer Settlers

of Ohio (Cincinnati, Ohio, 1852),

302-03.

10. Cayton, Frontier Republic, 21-31.

11. Frances Manwaring Caulkins, History

of Norwich, Connecticut (Hartford, Conn., 1866),

397, 511; Richard Anson Wheeler, History

of the Town of Stonington, County of New London,

Connecticut, facsimile reprint (Mystic, Conn., 1966), 693; Bruce C.

Daniels, "Economic

Development in Colonial and

Revolutionary Connecticut: An Overview," William and Mary

Quarterly, 3d ser., 37 (July, 1980), 438, 448.

130 OHIO HISTORY

That many Mariettans' plans went beyond

recreating a New England village

can be seen in a series of debates held

on snowy Ohio evenings during the

winter of 1790. Bent on restoring their

lost status, many of the leaders of the

Ohio Company in Marietta were full of

the rhetoric of orderly, civilized set-

tlement. But Thomas Wallcut, who spent

the winter of 1790 in Marietta,

recorded that when the local debating

society was given a choice between dis-

cussing capital punishment, the harmony

between farmers, mechanics, and

merchants in society, the establishment

of a police force in Marietta, and the

legality of Americans utilizing the

Mississippi River, they chose to debate

navigating the Mississippi. The choice

of debate topics indicates that along

with the plans for the establishment of

a civilized society, there were men in

Marietta who had no less interest in

economic success than in the Ohio

Company's plans for American society.12

Marietta's settlers intended that the

Ohio territory would be much more

than an Atlantic hinterland or a

backcountry. They looked further west to the

Mississippi River and wanted to take

advantage of the New Orleans trade.

Members of the Ohio Company intended to

make money for themselves

rather than being dependent on

established Boston or Philadelphia merchants.

Pennsylvania merchants would be their

suppliers, but the Marietta merchants

and farmers planned to make their own

profits by selling in New Orleans.

They looked beyond just giving the

eastern merchants their produce for fin-

ished goods. These men intended to

create and control a trade route that pene-

trated deep into the heart of the

continent. Ohio Company leaders felt that

Marietta had to represent much more than

the furthest line of western settle-

ment-some sort of expanding buffer and

furthest reach of civilization. The

founders of the Ohio Company intended to

control the most important trade

and migration route in the northern part

of the continent-the Ohio River.

They would provide a portal, giving

direction to the settlement of the vast

new lands available to Americans now

that the French and the English had

been banished from the long desired Ohio

Valley. The interior of the conti-

nent was there for the taking, and they

planned to be at the forefront of that

effort.

The image of their western settlement as

a portal rather than a hedge is the

key. In the earlier colonial period, the

"frontier" usually meant the settle-

ments at the point of the colonists'

furthest expansion into the wilderness,

making it either a buffer zone against

Indian attack, a backcountry isolated

from the mainstream life of the colony,

or a hinterland which traded with the

coastal communities. The Marietta

settlers, on the other hand, crossed the

Appalachian Mountains and put themselves

near the headwaters of a mighty

12. Thomas Wallcut Journal, entry of 27

January 1790, Thomas Wallcut Papers, 1671-1866,

microfilm edition, Massachusetts

Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts (hereafter referred

to as Wallcut Journal), reel 3.

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern 131

transport system that flowed to the

west, away from the old world and on to a

new continent. The Ohio Company leaders

wanted their town to be a gate-

way for a nation moving west. They

envisioned a mighty nation by looking

westward, down the river, not back over

their shoulders to the Atlantic coast;

they faced the interior and wanted to

take advantage of all the hinterland that

would connect them with the port of New

Orleans. These men planned to

harness a river to claim a continent,

not just carve a town out of the wilder-

ness. In addition to attracting New

Englanders like Joseph Gilman seeking

the recreation of a stable society,

Putnam's vision also attracted men like

Dudley Woodbridge eager to found a

continental trading empire.

II

The first group of men who went west in

1788 to establish the town of

Marietta were surveyors, boatbuilders,

and guards employed by the Ohio

Company. They came to survey town lots

and get ready for settlers to arrive.

One surveyor, a young man named James

Backus, sent very good reports of

the western country to family back home

in Norwich, Connecticut. He wrote

that the Indians were friendly: one

family had even stayed in the white set-

tlement and helped them plant corn, and

that a treaty with the Ohio tribes was

only a few months away. James also

reported that settlers were flocking in

by the boatload, and he asked his father

to send him 10 pounds of nails and

100 pairs of shoes to be sold for a tidy

profit. He sent along the names of

four Ohio Company shareholders (three of

whom appeared in the Norwich

business records of his brother-in-law,

Dudley Woodbridge) and urged his fam-

ily to buy their shares to sell later

for a much higher price.13

Dudley Woodbridge wrote James in

December to ask for more information

about the western country. Complaining

that business was dull in Norwich,

and money growing scarcer, he asked

about "the prospects of business" in the

West. He asked for a detailed report:

What is the climate, a healthy or

unhealthy one, what is the danger in going, or af-

ter you are there, where can vessels go,

and have the least land carriage

Philadelphia, Virginia, or where, are

vessels suffered to go down and up the

Mississippi unmolested, how far can a

vessel of a hundred tons get up the Ohio,

are materials for shipbuilding plenty

and good . . . is the navigation down the

rivers safe and good, what is the demand

for goods and what kinds will best an-

swer, with the prices of liquors etc.

there, what is the price per ton for land car-

13. Thomas J. Summers, History of

Marietta (Marietta, Ohio, 1903), 55, 77-81; Hulbert,

"Ohio Company," cxxiii;

Shannon, "The Ohio Company," 407; James Backus to Elijah Backus,

9 June and 15 June 1788, in the

Backus-Woodbridge Collection, microfilm edition, Ohio

Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio

(hereafter referred to as Backus-Woodbridge Collection,

ME), box 1, folder 1.

132 OHIO HISTORY

riage, from Philadelphia or your nearest

seaport, what are the remittances that will

be made for goods, cash or produce, if

produce, what kind and the price? In short, I

should be glad of a particular and

minute information with regard to what does now

or may relate to the mercantile line that

part especially which relates to naviga-

tion viz. building, loading, and kind of

cargo.14

Woodbridge visited James in Marietta in

May and June of 1789, at the be-

ginning of a summer during which James

traveled as a surveyor for the Ohio

Company. He asked James to report on

good lands to invest in, and to buy

shares from nonresident shareholders for

him. Dudley planned to speculate in

land, mills, and mines, using Backus's

advance local knowledge of land, soil,

and resources to his advantage.

Woodbridge also discussed going into busi-

ness with such prominent Ohio Company

stockholders as Samuel Parsons

and Griffin Greene. Obviously, Marietta's prospects pleased

Dudley

Woodbridge, and he decided he could make

his fortune there.15

Lucy Woodbridge followed her husband to

Ohio with some of their children

in late September, arriving in early

November. Dudley Woodbridge as yet

owned no property. He rented a home and

shop, but constantly looked for

property to buy. Apparently the move

cost him most of what he had, but he

remained confident that he could make

profitable business deals and alliances

in Marietta. With his business knowledge,

experience as a lawyer, and his

connections within the Ohio Company

through his brother-in-law,

Woodbridge must have felt that he had an

excellent chance of succeeding.16

While Woodbridge was busy establishing

his business, Joseph Gilman's

son, Benjamin Ives Gilman, arrived in

town. He wrote his eastern fiancee

that Marietta already had the look of an

old settlement: "Those people who

wish it have not only the necessaries

but the luxuries of life in as great plenty

here as in N England." He also

bragged of how quickly the settlers cleared the

land and planted crops.17

But a year after the arrival of the

Woodbridges and the Gilmans, the out-

break of war with the Delaware Indians

interrupted all the carefully-laid plans

of the Ohio Company. During the 1780s,

the American army had established

numerous forts in the western country,

but it lacked the troops to enforce

peace in the region. Constant warfare

between the Kentuckians and the Ohio

Indians made the region a battleground

much of the time. In January of 1789,

14. Dudley Woodbridge to James Backus, 9

December 1788, Backus-Woodbridge

Collection, ME, box 1, folder 1.

15. Dudley Woodbridge to James Backus,

14 June 1789, Backus-Woodbridge Collection,

ME, box 1, folder 1.

16. Dudley Woodbridge to Roger Griswold,

11 November 1789, typescript, Dudley

Woodbridge-Roger Griswold

Correspondence, Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford,

Connecticut.

17. Benjamin Ives Gilman to Hannah

Robbins, 16 August 1789, in Noyes, A Family History,

163.

|

Marietta's Example of a Settlement Pattern 133 |

|

|

|

two treaties were signed at Fort Harmar, across the Muskingum from Marietta, in which the Indians, including Delaware and Wyandot leaders, agreed to peace in exchange for goods and the punishment of white aggres- sors. But many of the Ohio Indians, including the Shawnee and the Miamis further west, refused to abide by a treaty in which they had taken no part. 18 During the summer of 1790, white and Indian attacks continued unabated. Colonel Josiah Harmar convinced Governor Arthur St. Clair that the Americans would need to "'chastise'" the Indians. In September, Virginia and Pennsylvania militia gathered at Fort Washington (on the site of Cincinnati) to stage an expedition against Indian villages in northeastern Indiana. Poorly trained, supplied, and prepared, these troops suffered disastrous defeat as they marched north. Harmar's humiliation only increased the confidence of the Indians, and other Ohio tribes joined in the warfare against the American set- tlers. The federal government decided that more troops and money would help

18. Cayton, Frontier Republic, 36-38; Reginald Horsman, The Frontier in the Formative Years, 39-40. |

134 OHIO HISTORY

settle the area. Arthur St. Clair

himself, at the head of a force in the summer

of 1791 which aimed to secure the

Maumee-Wabash portage, lost nearly 1000

of his 1200 troops. The federal

government switched once again to peace ne-

gotiations between late 1791 and 1793,

but after their early victories, the

Ohio Indians were unwilling to make any

concessions.19

Marietta's settlers lived under siege in

the early 1790s. During the winter of

1790-1791, Indians attacked a settlement

at the Big Bottom about thirteen

miles up the Muskingum River, killing

twelve. Afterward, the settlers aban-

doned the outer settlements and

retreated to blockhouses and stockades in

Marietta and Belpre. By the end of 1793,

less than 500 people lived on the

Ohio Company's lands.20

The Indian wars ended with the Treaty of

Greenville in 1795. During the

winter of 1793-1794, General Anthony

Wayne established Fort Greenville

nearly one hundred miles north of

Cincinnati and trained troops there. With

better troops, better preparation, and

carefully secured supply lines, Wayne de-

feated the Indians at the Battle of

Fallen Timbers on 20 August 1794. One

year later the Indians ceded the Ohio

lands in southern and eastern Ohio to the

settlers.21 Having ousted the

earlier occupants, Ohio pioneers could at last

turn their full attention to settling

the region.

III

The Woodbridges' Marietta neighbors

included New England Revolutionary

War veterans and their contemporaries,

many of whom were accompanied on

their westward journey by sons,

sons-in-law, and nephews-young adults just

starting their families. William Dana, a

Continental Army captain from

Massachusetts, had sunk all his capital

into continental currency in 1788.

When that depreciated, he was forced to

move to Amherst, New Hampshire,

where his brother lived. He rented a

farm there, and earned extra cash as a car-

penter and deputy sheriff. In 1789, he

decided to move to the banks of the

Ohio with the Ohio Company and become

the owner of his own land once

again. Joseph Barker, a newlywed at age

24 in 1789, had worked as an ap-

prentice with his architect father and

later as a carpenter. But when he married

William Dana's eldest child, Elizabeth,

they followed Captain Dana to the

Ohio Valley. Barker settled on a

donation tract, and his descendants remained

in Marietta first as prosperous farmers,

and later as merchants well beyond the

Civil War.22

19. Cayton, Frontier Republic, 39;

Horsman, The Frontier in the Formative Years, 40, 44,

20. Horsman, The Frontier in the

Formative Years, 40-42.

21. Ibid., 47-49; Cayton, Frontier

Republic, 39, 47-49.

22. Hildreth, Early Pioneer Settlers,

337-39; Rodney T. Hood, "Genealogy and Biography of

Joseph Barker," in Joseph

Barker: Recollections of the First Settlement of Ohio, ed. by George

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern 135

But many young men who came west with

their fathers and fathers-in-law

wanted something more after the

Revolution. They were in their twenties

rather than in their forties or fifties

like Dudley Woodbridge, Rufus Putnam,

and the Ohio Company leaders. Benjamin

Ives Gilman was born in 1765, and

his primary interests lie in being in

the center of things. When Joseph's fi-

nancial difficulties forced him to move

west, his son went with him.

Benjamin returned to the East briefly in

1790 to marry Hannah Robins, and

then set about establishing a mercantile

business in Marietta. Benjamin Ives

Gilman sought an active role in the

government of the Northwest Territory,

and he became one of Marietta's most

active land speculators in the early

1800s. In addition to his political

ambitions and land speculation activities,

Gilman also hoped to build a fleet of

ocean-going vessels in order to connect

the Ohio Valley to the Atlantic trade

world. He wanted to participate actively

in the growth of the new nation. For

Benjamin, the move west was not to

re-establish traditional family

security, but rather to start a whole new life for

himself. He wrote a relative in Congress,

Nicholas Gilman, often, seeking

territorial appointments for himself.23

Like Benjamin Gilman, Dudley Woodbridge

was a Federalist, and like

Joseph Gilman, he accepted appointments

from Putnam in the territory's

government. The two families even allied

for a time-Dudley Woodbridge,

Jr., married Benjamin Ives Gilman's

eldest daughter (she died in childbirth a

short year later). But Woodbridge did

not rely primarily upon political and

status-oriented social connections, and

his son even less so. Dudley

Woodbridge established a different sort

of connection between his community

and the larger world, one of credit and

capital. His economic network grew

slowly, however, and Woodbridge

encountered many difficulties in cstablish-

ing it.

Despite the ambitions of Ohio Company

leaders, Marietta grew slowly in

the early 1790s. Dudley Woodbridge's

business early in the decade consisted

mostly of local barter. He received

mostly whiskey as payment for goods,

and in turn sold the liquor to men

working in town, many in the employ of

the Ohio Company. The townsmen paid

Woodbridge in work-carting rails,

plowing a garden, doctoring a cow,

killing a calf, bringing in stock, or draw-

ing millstones. Some paid with venison, which, like the

whiskey,

Woodbridge sold in Marietta to others

who raised no stock or did not hunt for

meat. The Woodbridge store provided the

community with a thriving busi-

ness and a center for social interaction

among the stream of customers coming

Jordan Blazier (Marietta, Ohio, 1958),

iii.

23. Hildreth, Early Pioneer Settlers, 306-10; Benjamin Ives Gilman to Hon. Nicholas Gilman,

27 February 1790 and 27 December 1795,

Benjamin Ives Gilman to Hannah Gilman, 25 April

1795, in Noyes, ed., A Family

History, 170-71, 206-11; Lee Soltow, "Inequality Amidst

Abundance: Land Ownership in Early

Nineteenth Century Ohio," Ohio History, 88 (Spring,

1979), see table two, "Top Twelve

... Property Owners in 1810," 137.

136 OHIO HISTORY

through daily. Besides the goods

Woodbridge received from local hunters and

farmers, he also sold cloth, thread,

tobacco, powder, wine, coffee and just

about anything else people needed to

make themselves more comfortable in

the woods.24

Dudley Woodbridge's business remained

healthy during the war with the

Delawares thanks to the opportunities it

furnished: he supplied goods to the

army and members of the local militia in

exchange for their pay vouchers, and

sold goods to the army directly as well.

In 1794 Woodbridge noted that "[m]y

principle remittance is by militia

order."25 Most of the fighting was centered

to the west of Marietta, and goods came

through Pennsylvania and down the

Ohio unimpeded.

Throughout the first decade, Woodbridge

overcame a series of obstacles to

his mercantile plans. A shipment which

arrived a month late in the spring of

1793 cost him an estimated $200 in sales.

The limited market during the

Indian wars meant that competition

between merchants was keen, and who-

ever received his goods first made what

money was to be had. The main army

sometimes moved through, heading west,

days before a big shipment ar-

rived-those sales were lost, although

the local militia was a constant buyer

during the summer. Another time

Woodbridge wrote that goods he had or-

dered in January "did not arrive

seasonably to answer a particular purpose for

which I designed them," indicating that,

once again, he took a loss.26

Reliable shipping presented a problem as

well. Woodbridge believed that

his shipments were so late because the

middleman in Pittsburgh did not get

them out on time. Once he complained

that his Pittsburgh correspondent had

carelessly stored his goods in a damp

cellar, and when they finally arrived, the

dry goods were wet, the tea was musty,

and many goods had sustained other

damage. In October of that same year, he

lamented that none of his commu-

nications to Philadelphia were received.

Woodbridge speculated that due to

the yellow fever epidemic in the city,

his messengers refused to enter and

simply "scattered" his

letters. No matter how good his markets were,

Woodbridge was at the mercy of forces

beyond his control-middlemen in

Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, sickness in

the cities, wagoners taking his goods

across Pennsylvania, and ship captains

on the Ohio River.27 In addition to

Woodbridge's personal troubles, local

society seemed to be under the same

siege by outside forces. After one

particularly lengthy period without sup-

24. Account Book, April to September

1790, Backus-Woodbridge Collection, Ohio Historical

Society, Columbus, Ohio (hereafter

referred to as Backus-Woodbridge Collection), box 17,

folder 2, Ibid., account with Henry

Rockwell; Wallcut Journal.

25. Letterbook, Dudley Woodbridge to

Webster and Co., 21 April 1794, Backus-

Woodbridge Collection, box 18.

26. Letterbook, Dudley Woodbridge to

Webster and Co., 9 April 1793, 5 May 1793, 28 June

1793, 26 October 1793, 26 May 1794,

Backus-Woodbridge Collection, box 18.

27. Ibid.

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern 137

plies, Woodbridge wrote that "our

women have not a shoe to their feet nor

any tea to drink."28

A merchant named Charles Greene provided

Woodbridge's main competi-

tion in the early 1790s. When trade was

slack in the summer of 1793,

Woodbridge wrote that trade would have

been even worse if Greene had failed

to take his goods further down the

river. At another time, Woodbridge re-

ferred to Greene getting shipments on

time and scooping sales while

Woodbridge's sat in a warehouse in

Pittsburgh. In one letter Woodbridge

complained that Greene sold linen

cheaper than he could, and speculated that

rapid price fluctuations allowed Greene

to buy at a lower price.29

Perhaps Woodbridge's most important

contribution to his community in-

volved helping other sorts of

businessmen become established. General mer-

chants created a diversified economy by

helping artisans make a start in the

cash-starved economy of Marietta. The

Woodbridges had tin brought in, and

the whitesmith paid his account with

cups, providing the Woodbridges with

goods to sell. Coopers paid with

barrels, blacksmiths paid with nails and

horseshoeing services, tailors paid with

coats and trousers, tanners paid with

leather.30

Dudley Woodbridge's dreams of building a

trading empire seemed to float

within his grasp at last in the fall of

1797 when a man named Harman

Blennerhassett arrived in Marietta. Like

Rufus Putnam's use of political pa-

tronage, Woodbridge sought to exploit

outside contacts, but in a different

way. A businessman from Pittsburgh named

Edward T. Turner sent

Blennerhassett to Woodbridge with a

letter of introduction stating that

Blennerhassett was a gentleman from

Europe who wanted to become a resi-

dent of the West. A second letter,

presumably a sealed one Blennerhassett

couldn't read, stated, ".. . he is

a man whom I know to be worth 25,000

L(pds). Could you persuade him to set

down among you I think it would be

a great acquisition as monied men will

give a celebrity to the settlement and

enhance its value."31

Blennerhassett was in fact the youngest

son of a noted Irish family, who

through the death of his elder brothers

had inherited a large estate. He traveled

throughout Europe for a time, before

returning to marry a niece, Margaret

Agnew, thirteen years younger than he.

His family was upset over the mar-

riage as well as his support of the

French Revolution, so the thirty-two year

28. Letterbook, Dudley Woodbridge to

Webster and Co., 25 September 1794, Backus-

Woodbridge Collection, box 18.

29. Summers, History of Marietta, 245;

Letterbook, Dudley Woodbridge to Webster and Co.,

21 April 1794, 14 July 1794,

Backus-Woodbridge Collection, box 18.

30. Ledger, 1799-1809, Backus-Woodbridge

Collection, box 23, folder 3; ledger, November

1799-December 1800, Backus-Woodbridge

Collection, box 27, folder 1.

31. Edward Turner to Dudley Woodbridge,

31 July and 2 August 1797, Backus-Woodbridge

Collection, ME, box 3, folder 1.

138 OHIO HISTORY

old Blennerhassett sold the family

estates for $160,000 and sailed for New

York in 1796.32

Blennerhassett's money and reputation

were all Woodbridge needed to set

himself up as the preeminent merchant in

Marietta. Through Blennerhassett,

Woodbridge ordered goods directly from

London, enhancing his local status by

the quality of goods he obtained. In an

agreement made on 15 June 1799,

Woodbridge and Blennerhassett became

equal partners, sharing the profits

from the goods from London.

Blennerhassett supplied the credit to buy the

goods, while Woodbridge stored and

disposed of them, and kept the books and

accounts.33

Mariettans made quick use of the peace

that arrived on the Muskingum after

1794. Dudley Woodbridge began to handle

much more produce as farmers

began planting and harvesting in

earnest, and more settlers arrived all the

time. Woodbridge took in bulk produce:

corn, rye, oats, and wheat. He also

took in processed foods such as meat,

cheese, and butter. Marietta's farmers

began to turn a profit; after 1800, more

and more customers were paying for

goods with cash.34

These farmers made up the majority of

Marietta township's population and

the population of Marietta's hinterland

along the Ohio and Muskingum

Rivers, and Wolf and Duck Creeks. Many

of these families provided

Washington County with stable,

persistent kinship networks that figured

prominently in the Civil War rolls seven

decades later. Without their ambi-

tions and persistence, all of the

Woodbridges' plans would have come to

naught.

The Ohio Company sold 817 shares, but

less than a third were purchased

by settlers who went to Ohio; those

intent on speculation bought the rest.35

Most settlers purchased allotments from

local stockholders or agents who rep-

resented nonresident proprietors, or

they took over vacant donation tracts.

Two of the most successful and

persistent New England-born farmers in the

first half of the nineteenth century

gained their start on donation tracts, al-

though both had family in the area to

provide help if needed-Joseph Barker

and Benjamin Dana.

Settlers had abandoned the outlying

settlements during the Indian Wars

from 1791 to 1794, but shortly

thereafter, young men who received donation

tracts for their military service-men

like William Dana's son-in-law, Joseph

32. Raymond E. Fitch,

"Introduction: 'The Fascination of This Serpent,'" in Breaking

With

Burr: Harman Blennerhassett's

Journal, 1807, ed. by Fitch (Athens,

Ohio, 1988), xi.

33. Dudley Woodbridge, Jr. to Mordecai

Lewis, 1 February 1799 and Partnership

Agreement, in the Woodbridge Mercantile

Company Records, microfilm edition, Regional

History Collection, West Virginia

University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

34. Ledger, April 1799-September 1800,

Backus-Woodbridge Collection, box 23, folder 1.

35. Shaw Livermore, Early American

Land Companies: Their Influence on Corporate

Development (New York, 1939), 134-46.

|

Marietta's Example of a Settlement Pattern 139 |

|

|

|

Barker-cleared land and planted crops along the Muskingum and along Wolf Creek. Barker's contemporary Benjamin Dana kept a journal during 1794 that gives a picture of life in these outlying settlements. Benjamin Dana traveled to Ohio in the spring of 1794 with his cousin, Israel Putnam III. Young Israel's father, a stockholder in the Ohio Company, had removed there only a short time before. Benjamin Dana obtained land by agreeing to improve a donation tract, and he managed to farm it as a single man by providing labor to area farmers who in turn lent him labor, oxen, and equipment. In May, Dana plowed and planted corn for Timothy Gooddale one day, and another farmer the next. He planted corn for a man named Davis, and then helped Gooddale build a fence. The next week he plowed and planted his |

140 OHIO HISTORY

own land with corn; then he helped a

farmer named Pierce. Davis helped him

with his land the following day; then

Dana spent time planting corn for a

man named Loring, and then for Gooddale

again. One day Dana helped

Captain Miles raise a barn, after which

he attended a ball there. Other social

events combined with work included

shooting and exploring trips with other

men on Sundays. He used Miles' oxen one

day and Putnam's hoes another.

Dana worked on the Curtis farm, and

Curtis worked on Dana's the next week.

Dana delivered his corn by boat to

Cincinnati, and traveled back to New York

in January in 1795, returning to Belpre

once again in the summer of 1795.36

Once the land had been secured, Marietta

grew quickly. The bonds estab-

lished in Marietta in order to make the

community work represented a mixture

of old and new strategies. Farmers

established their traditional local kinship

and neighborhood networks. But while

Federalists like Rufus Putnam and

Joseph Gilman's son, Benjamin, counted

on the patronage system of the fed-

eral government to establish their local

status and power, merchants like

Dudley Woodbridge and his son, Dudley,

Jr., were establishing connections,

based on credit, between Marietta and

the outside world. When in a decade's

time the Federalists lost control of the

national government, it was these

commercial connections that ensured

Marietta's survival.

IV

Despite the spectacular success of white

settlement in southeastern Ohio af-

ter the Indian Wars, Rufus Putnam's

world came under siege in 1800 with the

election of Thomas Jefferson, and then

collapsed altogether in 1803 with

Ohio's statehood. Putnam controlled the

patronage system in Washington

County and Marietta from 1790 to 1803.

With the power of a federal ap-

pointment as Surveyor General and

ajudgeship behind him, Putnam served as

the town's principal leader. He

appointed some officers, and his recommenda-

tions to Governor St. Clair and Congress

carried weight for territorial posts.

In 1798, Dudley Woodbridge's

brother-in-law, Matthew Backus, brought

himself forward as a candidate for a

territorial judgeship. Putnam denounced

Backus as a candidate for lack of social

standing and trying to circumvent the

patronage network. Putnam's power and

status came from outside the town

of Marietta.37

But change had swept through Ohio

despite Putnam's denial of it.

Virginians and others settled along the

Miami and Scioto River Valleys in the

1790s, many of whom would later become

Jeffersonian Republicans. These

men had no ties to the federal

government, and they wanted to establish local

36. Benjamin Dana Journal, typescript,

Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

37. Cayton, Frontier Republic, 49-50.

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern 141

control within Ohio. They sought to

replace the patronage system with local

competition for offices. After the

election of Jefferson as president, they

called for frequent elections and an

Ohio state government based on a strong

legislature and a weak executive.38

The Virginians wanted statehood as soon

as possible; the Mariettans did

not. In 1801, the electors of the town

met and resolved to oppose statehood

on the grounds that Ohio's society had

not developed a stable order yet, and

needed to remain under the paternalistic

eye of St. Clair and the federal

Congress. But the more numerous

Jeffersonian Republicans carried the day,

and Ohio became a state in 1803.39

The Revolution of 1800 shook Marietta's

political structure to its very

foundations. Some men who had owed their

offices to Putnam-Return J.

Meigs, Jr., Griffin Greene, and Joseph

Buell-began opposing the old general

in 1801. They sided with the Virginians

in state politics, and when the

Virginians emerged as the winners, these

men received appointments in the

new state government. Rufus Putnam

retired from active politics when he

was replaced as Surveyor General of the

United States in September of

1803.40

The Federalists in Marietta continued to

try to keep the town in the fore-

front of the development of Ohio and the

United States despite losing the

statehood battle, because they still

envisioned Marietta as the connecting-

point between East and West. In 1804

Congress was expected to make a pro-

posal to use two percent of the money

from land sales in Ohio to build a road

from Washington to the Ohio River to

connect interior navigable rivers with

the Atlantic coast. Dudley Woodbridge,

his brother-in-law Matthew Backus,

Paul Fearing, David Putnam, Rufus

Putnam, Benjamin Ives Gilman, Joseph

Barker, and Return Meigs all served on a

committee for the town of Marietta

to petition the federal government to

use their city as the terminus. They

wrote that the route to Marietta would

be easier to reach than any place above

it on the river; that a good road

already connected them to Chillicothe, the

main seat of government; that Kentucky,

Tennessee, Indiana, and Louisiana

would all be accessible to the road by

way of the Ohio; that Marietta was sit-

uated in a safe place for winter travel,

above the falls of the Ohio; and that the

town could be connected with Lake Erie

up the Muskingum and Cuyahoga

Rivers. But it was not to be. The road

bypassed Marietta, and later genera-

tions lived and died, happily enough, in

a town that thrived but never grew to

be the regional power that Cincinnati

became.41

Despite his disappointment, Rufus Putnam

stayed in Marietta until he died.

38. Ibid., 52-77.

39. Ibid., 73-77.

40. Ibid., 78-79.

41. A Circular Sent to Congress, 1804,

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus, Ohio.

142 OHIO HISTORY

Another family better serves as an

example of the failure of the Federalists

and a foil for the success of the

Woodbridges-the Gilmans. Joseph Gilman

lived very much in the colonial world he

had been raised in when he moved to

Marietta in 1789. Gilman was pleased

when St. Clair appointed him as a ter-

ritorial judge on the basis of his

"character," without reference to talent.42

But Gilman remained more interested in

his farm than in the bench until the

end of his days. Like any good

colonial-era leader, he served as a judge when

asked, but his personal ambitions did

not lead him to seek a political posi-

tion.

But Joseph's son was more involved than

his father in the Ohio

Company's hopes for Marietta. Benjamin

Ives Gilman had ambitious plans

for Marietta, but his attitudes changed

after 1808 when Jefferson's embargo

destroyed his ship-building enterprise.

That same year, his daughter Jane,

Dudley Woodbridge, Jr.'s wife, died in

childbirth, and shortly thereafter

Benjamin's father died as well. Although

a decade earlier he had written that

Marietta had the look of an old

settlement, he began to complain that

Marietta had all the problems of a

"new settlement," including poor schools.

He began to see Marietta as a failed

experiment, and his discontent grew as

his fortunes declined. He removed to

Philadelphia in 1812. Perhaps Gilman

felt that the national government had

abandoned him (the navy had refused to

buy his surplus ships in 1808); it had

clearly abandoned Marietta. He went

into the mercantile business in

Philadelphia, and lived there until he died in

the 1830s, having given up his plans to

be part of the building of the new na-

tion.43

Benjamin looked forward in terms of the

economy, wanting to build an

ocean-going ship enterprise to help

claim the West for America, but he

looked backward in terms of his social

ambitions. Benjamin Gilman was

comfortable in the world created by

Rufus Putnam's patronage network, but

when that world collapsed after Ohio

became a state, he left Ohio forever.

Benjamin Gilman and others like him saw

themselves as pursuing the na-

tional interest-not as poor relatives,

but as leaders. With the ties between

the early Marietta leaders and the

Federalist government, they could make

some claim to being central to the

planning of what the new nation would be,

rather than just an appendage to the

older states. They planned to be central to

the purpose of the expansion of the new

United States, but in the end decided

that they had not achieved all they

hoped for.

Marietta failed to become all that

Woodbridge hoped for, too, but he stayed

42. Joseph Gilman to Hon. Nicholas

Gilman, 23 February 1790, in Noyes, ed., A Family

History, 168.

43. Benjamin Ives Gilman to Hon.

Nicholas Gilman, 6 January 1808 and 6 December 1809;

Gilman to Benjamin Clark Gilman, 11

March 1811, in Noyes, ed., A Family History, 277-79,

296-98, 302-03.

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern 143

anyway. Based on credit and capital, his

links to the world outside Marietta

were quite different in character from

Gilman's or Putnam's. Dudley

Woodbridge, Jr., thirteen years Benjamin

Gilman's junior, would improve on

his father's business practices and

function perfectly in a society that judged

men differently than Gilman's had.

Dudley's brother Jack wrote from

Chillicothe, looking for a boy to work

in the bank in the spring of 1813, and

Dudley replied that he knew of some with

good enough character, but none

with good enough arithmetic skills.

Dudley wrote, "In this quarter every

young man who can add up a sum in

addition gets employed as a clerk."44

The economic connections based on credit

and markets proved to be much

more flexible and adaptable than the

political links of the Federalists had

been. Dudley Woodbridge, Jr., built upon

his father's foundations. He

formed partnerships with merchants in

surrounding towns, supplied many

merchants as far away as Zanesville well

into the 1820s, utilized local capital

through banks, and sold and distributed

Pittsburgh nails and glass as well as

Kentucky tobacco, Tennessee cotton, and

Louisiana sugar after the War of

1812. Through his business connections,

Dudley Woodbridge, Jr., helped

make Marietta the hub for life in

southeastern Ohio, even if the Mariettans

did fail to make their town the hub of

the West.45 In 1807

William

Woodbridge, Dudley's younger brother,

reported to his Uncle James Backus

that "our little place continues to

increase in wealth and population Thanks be

to the unremitting activity of our

commercial people."46

Farmers turned to the merchants rather

than to the political elite to further

their economic interests. They sought to

do all they could to promote easy

movement between their homes and

Marietta, in a conscious attempt to ce-

ment their ties to Marietta merchants.

In February 1806, the citizens of

Marietta organized a lottery for the

purpose of constructing a bridge over the

Little Muskingum River. Most of the

subscribers made their pledges in corn,

whiskey, and labor, usually under five

dollars. Not surprisingly, most of

those with cash to pledge were the city

dwellers-merchants and professionals

like the Greenes, Gilmans, Mixers,

Woodbridges, and Putnams. The farmers

allied themselves with the merchants'

interests.47 When depression hit the

region following the Panic of 1819,

farmers did not content themselves with

subsistence agriculture but strived to

establish new cash crops such as tobacco

in southeastern Ohio.48

44. Letterbook, Dudley Woodbridge, Jr.

to John Woodbridge, 15 April 1813, Woodbridge

Mercantile Records, ME.

45. Kim M. Gruenwald, "Settling the

Old Northwest: Changing Family and Commercial

Strategies in the Early Republic"

(Ph.D. diss., University of Colorado, Boulder, 1994), 185-278.

46. William Woodbridge to James Backus,

21 June 1807, Backus-Woodbridge Collection,

ME, box 2, folder 1.

47. Muskingum Bridge, Case Western

Reserve Library, Cleveland, Ohio.

48. Robert Leslie Jones, History of

Agriculture in Ohio to 1880 (Kent, Ohio, 1983), 143-54,

144 OHIO HISTORY

The experiences of Marietta's farmers

and merchants have much to tell us

about the settling of the Old Northwest

and the Ohio Valley. Benjamin Dana

and farmers like him established new

family nuclei, but merchants forged

chains of credit relationships that

bound their region and their nation together.

Utilizing lines of credit, Dudley

Woodbridge, Jr., built regional ties from St.

Louis to Pittsburgh and ties between

regions from the Ohio Valley to

Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore.

These ties ensured that Ohio would

remain firmly connected to the financial

and commercial centers of the East

long before the era of canals and

railroads. Merchants moved west to extend a

network of trade and in so doing helped

insure that the United States would be

more than a collection of local kinship

and neighborhood networks growing

up in isolated places. When merchants

helped settle a place like Marietta dur-

ing the early national period, that

place became part of an economic network

rather than a backcountry or a buffer

against attack. Alliance with like-

minded farmers was crucial, but it was

because of the eastern links of the

merchants that the new United States

could set out to claim a continental em-

pire and still survive as a nation.

219-20, 244-47, 251-55, 275.

KIM M. GRUENWALD

Marietta's Example of a Settlement

Pattern in the Ohio Country: A

Reinterpretation

As historians of the Early Republic,

scholars of the Progressive era created

a long-lasting, influential school of

interpretation for the decades following

the American Revolution. The Progressive

school focused on the conflict be-

tween common men who favored local

control and an elite which favored

strong central authority-as they deemed

it, the forces of democracy versus

the forces of aristocracy. The Old

Northwest provided a perfect arena for these

historians to test their hypotheses.

Following in the footsteps of Frederick

Jackson Turner, they described how the

forces of the common man developed

as Americans spread through the new

territories in the Old Northwest. In The

Civilization of the Old Northwest: A

Study of Political, Social, and

Economic Development, 1788-1812, Beverley Bond described the new region

as the laboratory where Americans first

experimented with democracy. Settlers

took colonial ideas about law,

government, and society with them. But once

they were in the West, they adapted to

their new life in the wilderness,

dropped conventional ideas that no

longer served their needs, and developed

egalitarian institutions. In Valley

of Democracy: The Frontier versus the

Plantation in the Ohio, 1775-1818, John D. Barnhart followed up on Bond's

work, focusing even more narrowly on the

Ohio Valley to show how the

frontier produced American democracy.1

Marietta, Ohio, occupied a peculiar

place in this historiography of the Early

Republic-a place which relegated the

town's story to a peripheral role within

the Progressive school's lexicon. The

town was settled in 1788 by the Ohio

Company, a group of New England

Revolutionary War veterans and their as-

sociates. Historians wrote that

Marietta's settlers recreated a New England vil-

lage in the wilderness. Composed chiefly

of those who adhered to

Federalism, Mariettans seemed too

different from the pioneer farmers inhabit-

ing the rest of the state to be

considered typical. Thus, although Marietta's

Kim M. Gruenwald is Assistant Professor

of History at Kent State University.

1. John D. Barnhart, Valley of

Democracy: The Frontier versus the Plantation in the Ohio

Valley, 1775-1818 (Bloomington,

Ind., 1953); Beverley W. Bond, Jr., The Civilization of the Old

Northwest: A Study of Political,

Social, and Economic Development, 1788-1812 (New York,

1934).

(614) 297-2300