Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

JOHN M. WEGNER

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives, 1900-1911: An Analysis

of Roll-Call Voting

Students of legislative behavior have

long had a penchant for examining the

workings of the United States Congress,

foreign parliaments, and other na-

tional assemblies. They have paid less attention to

state legislatures.

Despite a growing interest in

subnational legislative bodies, research on state

legislatures is still in its infancy.1

Lack of attention by historians to this

area of research is particularly

surprising when one considers the pivotal posi-

tion occupied by these bodies in the

past. Until the 1930s, when the activist

programs of the New Deal tipped government's

"center of gravity" to

Washington, state legislatures exercised

a disproportionate amount of power

over the lives of citizens.2

Although systematic investigations of

legislative behavior at the state level

have taken a "back seat" to

national studies, one facet of research-that per-

taining to party voting-has not been so

sorely neglected.3 Beginning in the

1950s, numerous studies appeared which

assessed the nature and impact of

partisanship on the legislative process

in state assemblies.4 Historians, how-

ever, can take little comfort from these

studies since their ambit has been al-

John M. Wegner teaches American history

courses at colleges in northwest Ohio and south-

east Michigan. He would like to thank

Drs. James Q. Graham and Bernard Sternsher, emeriti

of the Department of History at Bowling

Green State University, and James Marshall, Donna

Christian and the staff of the Local

History and Genealogy Department of the Toledo-Lucas

County Public Libary for their help and

suggestions during the research process.

1. Ballard C. Campbell, Representative

Democracy: Public Policy and Midwestern

Legislatures in the Late Nineteenth

Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1980), 1;

Malcolm E. Jewell,

The State Legislature: Politics and

Practice, second ed., (New York,

1969), 3.

2. Campbell, 2; Philip R. VanderMeer, The

Hoosier Politician: Officeholding and Political

Culture in Indiana 1896-1920 (Urbana, 1985), 3.

3. Jonathan P. Euchner,

"Partisanship in the Iowa Legislature: 1945-1989," paper presented

at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest

Political Science Association, Chicago, Illinois, April 5-

7, 1990, 2.

4. As examples, see Malcolm E. Jewell,

"Party Voting in American State Legislatures," The

American Political Science Review, 49 (September, 1955), 773-91; William J. Keefe,

"Party

Government and Lawmaking in Illinois

General Assembly," Northwestern University Law

Review, 47 (March-April, 1952), 55-71; W. Duane Lockard,

"Legislative Politics in

Connecticut," The American

Political Science Review, 48 (March, 1954), 166-73; and Charles

W. Wiggins, "Party Politics in Iowa

Legislature," Midwest Journal of Political Science, 11

(February, 1967), 86-97.

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 147

most exclusively within the recent

(i.e., post-World War II) past.

Notwithstanding a very few historical

studies on party voting, our knowledge

in this area is quite limited.5

It is the purpose of this study to

investigate the impact of party on roll-call

voting in the Ohio House of

Representatives during the early progressive pe-

riod. Time and place were selected so as

to provide a particularly rich setting

in which to examine this phenomenon.

During the first years of the twenti-

eth century, the so-called

"Progressive Era," existing political institutions

found themselves under increased

pressure to respond to vast changes in the

social and economic order.6 Old

political habits, including established forms

of partisanship, were subject to the

stresses accompanying these changes.

Ohio, a wealthy industrial state of

durable political traditions, occupied a key

position in a region acutely sensitive

to changes in the national polity.7 Its

institutions of government-including the

state legislature-were intimately

caught up in the struggle over the major

political issues of this period.8

This investigation will be concerned

first of all with answering three gen-

eral questions about the nature of party

voting. First, how frequently and to

what degree did the major political

parties divide during roll-call votes?

Second, did levels of party voting vary

noticeably throughout the period, and

further, do these variations appear

related to changes in the relative sizes of

party delegations or divided control of

executive and legislative branches of

government? Third, were certain public

policy issues more likely than others

to provoke partisan discord? In addition

to examining party voting (i.e., divi-

sions between the parties), this

study will also ascertain levels of party cohe-

sion (i.e., unity within the

parties) for all sessions in order to understand

more fully the dynamics of the party

factor in the legislative process.

Finally, an attempt will be made to

determine whether party voting reflected

randomized approaches to public policy

or whether it was rooted in substan-

tive differences between the parties.

This study will investigate partisanship

in the six regular sessions of the

Ohio House from 1900 to 1911.9

An essential prerequisite to any study of

5. Two of the best historical studies

which consider party voting in state legislatures are

Campbell, Representative Democracy; and

James Edward Wright, The Politics of Populism:

Dissent in Colorado (New Haven, 1974).

6. Jewell, State Legislature, 9;

VanderMeer, 2-3.

7. Graham Hutton, Midwest At Noon (Chicago,

1946), 294-95; also, as Meredith Nicholson

notes: "Outside of New York and

Pennsylvania, .. . here is no region where the cards are so

tirelessly shuffled as in the Middle

Western commonwealths, particularly in Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, and Kansas, which no party can

pretend to carry jauntily in its pocket." The Valley of

Democracy (New York, 1918), 185-86.

8. Harlow Lindley, Ohio in the

Twentieth Century, 1900-1938, Vol. VI of The History of the

State of Ohio, ed. by Carl Wittke (Columbus, 1942), 4.

9. A total of nine sessions is actually

included in the analysis. In addition to six regular ses-

sions, several additional meetings of

the General Assembly were held between 1900 and 1911.

In 1902 a brief "special

session" of the Seventy-fifth General Assembly was held to consider a

|

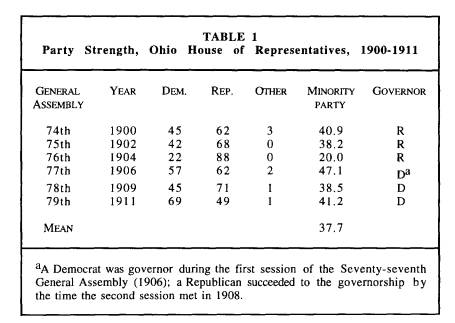

148 OHIO HISTORY

legislative partisanship is the presence of a competitive two-party system, and Ohio in this regard certainly qualifies.10 By the turn of the century, the Buckeye State had developed a strong two- party system. Democrats and Republicans actively vied for supremacy, and victory margins were often extremely close.11 The durability of the two-party system is reflected in the composition of the House (Table 1). In all sessions |

|

|

|

but one, minority party representation was substantial, ranging from 38 to 47 percent of the total. The lone exception was the Seventy-sixth General Assembly, where, emerging from an election campaign in which Mark Hanna's organizational skills had been finely honed, the Republicans out- numbered their Democratic opponents by a margin of four to one.

new municipal code. Also, a constitutional amendment passed in 1905 changed elections from odd to even-numbered years. As a result, members of the Seventy-seventh General Assembly had their terms extended an additional year, and a "second session" was held in 1908. Also, to accommodate the changes engendered by the amendment, the Seventy-eighth General Assembly held a brief "extraordinary session" in 1909 and returned for a second the following year. 10. Malcolm E. Jewell, and Samuel C. Patterson, The Legislative Process in the United States, first ed., (New York, 1966), 422. 11. Thomas A. Flinn, "The Outline of Ohio Politics," The Western Political Quarterly, 13 (September, 1960), 702; Jewell, "Party Voting," 779; Ohio Almanac 1973 (Lorain, Ohio, 1972), 19. |

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 149

Association with the Democratic or

Republican party was virtually essential

if a candidate was to succeed in

election. In the sessions of 1900 to 1911 no

member of a minor party won a seat in

the House, and only seven members

out of a total of 687, or just over one

percent, did not claim regular affiliation

with the Democrats or Republicans.12

The first years of the twentieth century

were a time of political turbulence

in Ohio, and particularly vexing for the

established party organizations in the

state. Boss-domination of parties, a

traditional feature of 19th century poli-

tics, came increasingly under attack

following 1900.13 Groups of reformers,

the so-called "progressives,"

attempted to weed out the most pernicious

abuses of contemporary partisanship

(patronage, dealmaking between parties,

etc.), and a handful even went so far as

to call for the abolition of parties al-

together.14 Whether intended

or not, the progressive insurgency blurred party

lines and created shifting alliances among lawmakers.15 A resurgent

Democratic party, once dominated by

conservative interests and now inspired

by reformers like Tom Johnson of

Cleveland, threatened the traditional major-

ity of the Republican party, itself

increasingly fragmented by battles between

progressives and conservatives.

Selection of Roll Calls

Did these nascent challenges to the

existing party system translate into

shifts in party voting behavior among

state legislators? A detailed examina-

tion of roll calls is an obvious point

of departure. Including all roll calls

taken in the House during this period

would be a ponderous task, and would

even run the risk of producing

misleading results. Most legislative bodies

have a tendency to pass "hurrah

votes," roll calls on which nearly all mem-

bers are in agreement.16 The

inclusion of these unanimous (and nearly unan-

imous) roll calls tends to deflate

actual levels of party conflict. Accordingly,

many researchers have examined only

those votes producing certain minimum

levels of dissent.17

12. Due to their lack of party

affiliation and their very small numbers, these seven members

have been excluded from the analysis of

roll-call voting.

13. Frederic C. Howe, a Cleveland

progressive elected to the Ohio General Assembly in

1905, noted in his autobiography:

"Ohio at that time was managed like a private estate by

Senators Hanna and Foraker." The

Confessions of a Reformer (New York, 1925), 157; for a

brief look at bossism, see Ohio

Almanac 1973, 359-64; for a more extensive treatment, see

Philip D. Jordan, Ohio Comes of Age,

1873-1900, Vol. V of The History of the State of Ohio, ed.

by Carl Wittke (Columbus, 1942),

189-219.

14. Hoyt Landon Warner, Progressivism

in Ohio, 1897-1917 (Columbus, 1964), 32.

15. George W. Knepper, Ohio and Its

People (Kent, Ohio, 1989), 332; Ohio Almanac 1973,

359.

16. Julius Turner, Party and

Constituency: Pressures on Congress, rev. ed. by Edward V.

Schneier, Jr. (Baltimore, 1970), 18-19.

17. As examples, see Jewell, "Party

Voting," 773-91 and Wiggins, 86-97; in a notable ex-

150 OHIO

HISTORY

For purposes of this study a number of

criteria have been established to re-

duce the number of roll calls to

manageable proportions while retaining those

which provide the greatest insight into

the impact of partisanship. First,

only bills pertaining to statewide

policy were considered. Although special

acts of a purely local nature, county or

township for example, were elimi-

nated, all measures relating to general

oversight of municipalities were re-

tained. Second, only final votes on

bills were culled.18 Consideration of

these votes offers a way of studying

legislative behavior at a most crucial

stage in the policymaking process-after

the contents of bills had been final-

ized during amendatory skirmishes and

when these measures were on the verge

of becoming state law. Third, only House

bills and Senate bills considered

by the House were culled; House

resolutions, joint resolutions and memorials

to Congress were eliminated. Finally,

roll calls had to pass a quantitative test

for inclusion in this sample of

"contested votes." Only roll calls in which

two-thirds or more of the total House

membership voted were included in the

sample.19 In addition, a

"contested vote" was defined as one in which at least

15 percent of those voting dissented

from the majority position.20 Use of the

aforementioned criteria produces a pool

of 337 "contested votes." Only these

"contested votes" will be

analyzed during the course of this study.

Party Voting

Since there is no agreement as to just

what constitutes a "party vote," three

indices will be initially employed in

order to gain a broad perspective of the

impact of party on roll-call responses.21

The least stringent of these indices

counts as "party votes" those

roll calls on which a simple majority of the par-

ties have taken opposite sides.22 The

most severe index, propounded by A.

Lawrence Lowell, defines as "true

party votes" those roll calls in which at

least 90 percent of the members of one

party opposed 90 percent or more of

ception, Lockard analyzed party voting

in Connecticut's General Assembly over a twenty year

period and included all roll calls,

including unanimous ones.

18. Final dispensation votes included

passage, defeat, and successful motions to indefinitely

postpone.

19. Consideration of this "degree

of participation" is a good way to avoid sampling in the

selection process and helps insure that

research will be confined to the more strongly con-

tested issues. Lee F. Anderson, Meredith

W. Watts, Jr., and Allen R. Wilcox, Legislative Roll-

Call Analysis (Evanston, 1966), 78-80; use of the

"two-thirds" criterion for selecting roll calls

was adapted from Don S. Kirschner, City

and Country: Rural Responses to Urbanization in the

1920s (Westport, Conn., 1970), 262.

20. David R. Derge uses this "15

percent dissention" standard in studying the Illinois legisla-

ture. "Metropolitan and Outstate

Alignments in Illinois and Missouri Legislative Delegations,"

The American Political Science

Review, 52 (December, 1958), 1054;

Kirschner uses the same

criterion in studying the legislatures

of Illinois and Iowa. City and Country, 262.

21. Campbell, 83; Keefe, 57.

22. Turner, 16.

|

Partisanship in the Ohio House of Representatives 151

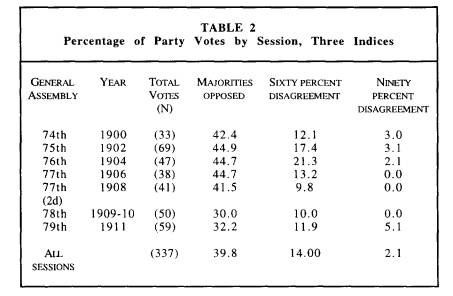

the other party.23 The third index, which sets a more exacting standard than the "simple majority" method, but less than that of the "Lowell index," re- quires a minimum of 60 percent disagreement between the parties. Specifically, the difference between the percentage of "yea" votes in one party and those of the other on a given vote must equal or exceed 60.24 As indicated in Table 2, party did not have an unusually strong impact on voting. No matter what index is employed, party divisions always occurred |

|

|

|

on less than half the contested roll calls. Just under 40 percent of the "contested votes" were "party votes" on the majority opposition index. Using the 60 percent disagreement index reduces the incidence of party voting to about 14 percent of the total. Finally, use of Lowell's highly stringent index requiring 90 percent of one party to vote in opposition to 90 percent of the other brings the level down to about two percent-only seven votes out of 337. Although there are no dramatic shifts from session to session,25 there is

23. A. Lawrence Lowell, "The Influence of Party Upon Legislation," Annual Report of the American Historical Association for 1901, 1,324. 24. Keefe uses a "60 percent disagreement" standard to define party votes in his study of the Illinois General Assembly. Both parties, however, must maintain at least 80 percent unity to qualify. "Government and Lawmaking," 58; Campbell also uses a 60 percent disagreement in- dex, but allows for greater proportional variations in the degree of party unity needed to meet this level of disagreement. Representative Democracy, 83. 25. The special session of 1902 was included with the regular one. The extraordinary ses- sion of the Seventy-eighth General Assembly (1909) and the regular session (1910) have been |

152 OHIO HISTORY

one trend which is readily apparent: the

level of party voting tends to decline

throughout the period. The most

significant decline occurs between the sec-

ond session of the Seventy-seventh

General Assembly (1908) and the

Seventy-eighth General Assembly

(1909-10). Using the majority opposition

index, one finds a decrease of nearly 11

percent occurs between these sessions.

In the former, just over 41 percent of

roll calls were party votes-fairly con-

sistent with previous sessions. In the

latter, however, less than one-third of

all roll calls fail to meet even this

most lenient definition of party voting.

Increased factionalism within Republican

ranks is probably the most likely

reason for this diminution in party

voting. During this decade a split had de-

veloped between conservative members of

the GOP (called "standpatters") and

progressives. The progressive faction, previously a minority among

Republicans, was strong enough to

organize the House in 1909.26

Progressive Republicans, who shared some

of the policy positions of Ohio

Democrats, no doubt found it expedient

to cross party lines on a greater num-

ber of votes than before, thereby

leading to an increase in GOP fragmentation

and a concomitant decline in party

voting.27 Ironically, while party voting

decreased on the majority opposition

index, a sudden upsurge is noted on

Lowell's 90 percent disagreement index

during the final session. No roll calls

registered as party votes on the Lowell

index during the Seventy-eighth

General Assembly while just over five

percent did so in the Seventy-ninth,

the highest in the period. The final

(Seventy-ninth General Assembly) ses-

sion marks the first time in twenty

years that Democrats had a majority in the

House and this change in party control

undoubtedly helped generate a new se-

ries of policy conflicts in which party

lines were most tightly drawn. An in-

crease in party voting at the highest

levels of opposition is a natural result.

It has sometimes been asserted that

fluctuations in the relative sizes of

party delegations will affect the level

of party voting. Although several stud-

ies have produced differing results, it

is usually theorized that the closer the

party balance, the greater will be the

incidence of party voting.28 This theory

is not valid for Ohio, and there is some

evidence that the opposite may be

true. Party balance held relatively

constant throughout the period, with one

exception. Republicans outnumbered

Democrats by a four-to-one margin dur-

ing the Seventy-sixth General Assembly

in 1904. Despite this enormous

imbalance, party voting occurred as

frequently-or even more so-than in

combined. In both cases, there was

little change in personnel and the party of the administra-

tion remained constant. The two sessions

of the Seventy-seventh General Assembly (1906 and

1908) are considered separately due to

slight attrition in membership and a change in the ad-

ministration party.

26. Warner, 226.

27. Ibid., 226-27.

28. Wiggins finds little relation

between party balance and party voting. "Party Politics," 86-

87; Campbell finds some relationship. Representative

Democracy, 83.

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 153

other years. When measured by the

majority opposition index, party voting

occurred on about 44 percent of the

contested roll calls, the same as for the

immediately preceding and succeeding

sessions. More significantly, party

voting measured at the 60 percent level

of disagreement reached a high point

for the period during the Seventy-sixth

General Assembly, suggesting that

Democrats and Republicans were more

inclined to sharper divisions than in

other years-despite a very large

disparity in the size of the delegations.

Divided control of the executive and

legislative branches is also a poor pre-

dictor of party voting. In the

Seventy-fourth through the Seventy-sixth

General Assemblies, a Republican

governor faced a House of Representatives

controlled by his own party. Control was

divided between a Democratic gov-

ernor and a Republican-dominated House

in the first session of the Seventy-

seventh General Assembly. The ensuing

death of the Democratic governor

and succession of the Republican

lieutenant governor to this office meant that

control of both the House and the

administration reverted to the GOP for the

second session of this assembly (1908).

With the election of a Democrat as

governor in 1908, control was again

divided during the Seventy-eighth

General Assembly (1909 and 1910), while

Democrats took charge of both the

House and governorship during the

Seventy-ninth (1911). Levels of party

voting varied significantly in the two

sessions in which control of the two

branches was divided. Further, the

change from divided control in 1906 to

Republican domination in 1908 produced

only marginally lower rates of party

voting. Although barely significant, the

level of party voting increased from

the Seventy-eighth General Assembly

(divided control) to the Seventy-ninth

(Democratic governor and House).

Comparison of the data culled for this

study with that on other legislative

bodies amplifies the relatively low

level of party voting in the Buckeye State.

Comparisons between studies can be

difficult because of differing methods

used to select roll calls for analysis

as well as standards for defining a "party

vote." Nonetheless, several studies

exist which use methods similar to those

employed here. A. Lawrence Lowell's

study found that members of the lower

chambers of five states in the late 19th

century cast "true party" votes (90

percent opposition) on about 18 percent

of contested roll calls, nearly nine

times the rate of similar votes in Ohio

from 1900 to 1911. Ohio, one of the

states examined by Lowell, ranked third

among the five states in the incidence

of these "true party" votes.29

Lowell's data should be used with caution.

Although unanimous votes were eliminated

from the study, Lowell considered

many procedural motions and resolutions

unrelated to policymaking. As an

example, it was noted that in Ohio only

six of the 18 "true party" votes in

the House concerned legislative matters.

Elimination of all but these six

29. Percentage is derived from data in

Lowell, 541.

154 OHIO HISTORY

votes brings the level of "true

party" voting in Ohio to about three and one-

half percent of contested roll calls.30

In a study of the lower chambers of the

legislatures in three states (Illinois,

Iowa, and Wisconsin) in the 1880s and

1890s, Ballard C. Campbell found that

just over 65 percent of all significant,

non-unanimous votes were "party

votes" as measured by the majority opposi-

tion index. This far outdistanced Ohio

which had a comparable level of just

under 40 percent of the roll calls

studied. Employing the measure of 60 per-

cent disagreement, Campbell's study

found almost 31 percent of roll calls to

be party votes, a figure more than twice

that for Ohio. Using the rigid stan-

dards of Lowell's index, Campbell found

the three legislatures had an average

of 11 percent party voting, far in

excess of the two percent figure for Ohio.31

James Wright's study of the Colorado

House of Representatives in the 1880s

and 1890s generally shows similarly high

levels of partisanship. Although

limited to certain "significant

issues" selected by Wright, this inquiry ascer-

tained that a majority of the major

party delegations opposed each other on 55

percent of the roll calls in the 1887

session. This rate increased to nearly

three-quarters of the roll calls in the

sessions of 1893 and 1894. Using the 60

percent disagreement measurement, Wright

found no party voting in 1887.

There was, however, a dramatic upsurge

to more than one-third of all roll

calls in 1893 and 1894.32

It has generally been assumed that

partisanship is a less significant factor in

decisionmaking in state legislatures

than in the U.S. Congress.33 Two stud-

ies of party voting in Congress during

the early 20th century confirm this as-

sumption. If party voting occurred less

frequently in Ohio than in other state

legislatures of the period, then it was

dwarfed even more by levels in the

United States Congress. In an

examination of all roll call votes in the United

States Senate between 1909 and 1915,

Jerome Clubb and Howard Allen found

that 71 percent qualified as "party

votes" on the majority opposition index,

nearly one and three-quarter times the

number recorded in the Ohio House be-

tween 1900 and 1911.34

Applying Lowell's 90 percent index to all roll call

votes taken in the U. S. House, David

Brady and Phillip Althoff also found a

high level of partisanship. Just over 35

percent of the votes taken in the ses-

sions between 1901 and 1911 were party

votes when measured by this stan-

dard, seventeen times the rate for roll

calls taken in Ohio during the same pe-

riod.35

30. Ibid., 338-39.

31. Campbell, 81-83.

32. Wright, 94, 164, 178.

33. Belle Zeller, ed., American State

Legislatures: Report of the Committee on American

Legislatures, American Political

Science Association (New York, 1954),

189.

34. Jerome M. Clubb and Howard W. Allen,

"Party Loyalty in the Progressive Years: The

Senate, 1909-1915," The Journal

of Politics, 29 (August, 1967), 571-72.

35. David W. Brady and Phillip Althoff,

"Party Voting in the U.S. House of Representatives,

|

Partisanship in the Ohio House of Representatives 155 |

|

|

|

Malcolm Jewell' s study of party voting in the legislatures of eight states in the 1940s provides a means of comparing the frequency of this phenomenon in the early 20th century with that of a later period. Remarkably, levels of party voting had changed very little in the Ohio House. Jewell found that in the sessions of 1941 and 1945, 38 percent of all roll calls found majorities of both parties on opposite sides, a figure which approximates that of 39.8 per- cent for the period 1900 to 1911. Also significant is the fact that Ohio con- tinued to rank low relative to other states in party voting. Jewell found that approximately 56 percent of roll calls taken in the lower chambers of the eight states qualified as party votes, a figure about 18 points higher than that

1890-1910: Elements of a Responsible Party System," The Journal of Politics, 36 (August, 1974), 755-56. |

156 OHIO HISTORY

of the Ohio House alone. Ordinally, Ohio

tied for sixth place in levels of

party voting; five state Houses had

higher rates while only one had lower.36

The question remains whether certain

policy issues were more likely to lead

to party voting than others. In order to

answer this question it was necessary

to classify all contested roll calls

according to policy content. A two-tiered

classification scheme, originally

propounded by Ballard Campbell, was used

in this study.37 All

roll-call votes were assigned to one of five general

"policy spheres" with the roll

calls in each of these spheres subdivided into a

number of much more specific

"policy topics."

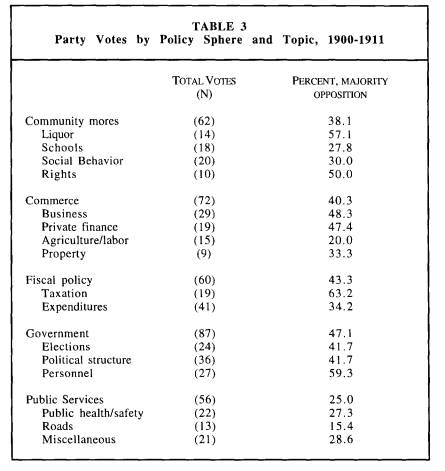

The percentage of "party

votes" (i.e., majorities of both major parties in

opposition) in each policy sphere/topic

is shown in Table 3. As indicated,

levels of party contentiousness varied

depending on the type of issue under

consideration. Among the five policy

spheres, roll calls dealing with the

structure of government (creation of

offices, oversight of municipalities,

composition of commissions, etc.) were

most likely to lead to party votes,

with just under half producing majority

opposition. Roll calls pertaining to

the state's fiscal policies were a close

second while those concerning com-

merce and community mores ranked third

and fourth, respectively. Public

services issues produced comparatively

few party votes; only one roll call in

four found majorities of Democrats and

Republicans on opposite sides of the

issue.

Variations in patterns of party voting

may be illustrated by comparing

these ordinal rankings of policy spheres

for Ohio with those obtained by

Ballard Campbell in his study of three

Midwestern legislatures in the late

19th century. Fairly similar rankings

were accorded to three policy spheres:

where government, fiscal policy, and

commerce ranked first, second, and third

(respectively) in producing party votes

in Ohio, these same spheres ranked

second, third, and fourth in levels of

party voting in the other states. The

most significant difference was in the

relative importance attached to mores

issues in producing partisan splits.

While legislators in the states studied by

Campbell were more likely to divide

along party lines in this sphere than any

other, those in Ohio found these issues

to be less a matter of party concern;

community mores ranked fourth among the

five policy spheres in levels of

party voting. Lack of party

contentiousness on public services issues, how-

ever, was consistent. This sphere was

least likely to find Democrats and

Republicans in opposition in Ohio as

well as in the states studied by

Campbell.38

36. Jewell, "Party Voting,"

784.

37. Campbell, 54-78.

38. Ibid., 88-91; ordinal rankings have

been used for comparative purposes because of dif-

ferences in the definition of a

"party vote." This study has analyzed "majority opposition"

votes while Campbell relies on a

"60 percent disagreement" index.

|

Partisanship in the Ohio House of Representatives 157 |

|

|

|

Party voting varied widely among the sixteen policy topics. Legislators voted much more often along party lines on bills relating to the collection of public funds (taxation) than they did on those dealing with spending them (expenditure). Tax bills, in fact, were the single most likely topic to produce opposition between Democrats and Republicans. Although fewer party votes were cast in the area of community mores than most other policy spheres, in- dividual topics varied greatly in degree of party contentiousness. Temperance was bound to be a volatile issue given the activism of various "dry" groups, such as the Anti-Saloon League, in the early 20th century. It is clear that parties in particular were sensitive to debate on these matters. Overall, liquor policy ranked third among the sixteen topics in producing party divisions. Nearly six out of ten roll calls taken on this subject found Democrats and Republicans in opposition. Criminal rights issues were only slightly less contentious, this topic ranking fourth in provoking partisan splits. By con- trast, very little party discord occurred on roll calls relating to school policy and social behavior. On roll calls in the commerce sphere, the parties tended to divide much more often on business and private finance (insurance, bank- |

158 OHIO HISTORY

ing, etc.) bills than on those

concerning agricultural and labor policy and

rights and/or conditions of property

ownership. Some disparity existed in

levels of party voting on topics in the

government sphere. While about four

out of ten roll calls dealing with

elections practices or oversight of the politi-

cal structure produced party splits,

nearly six out of ten roll calls pertaining to

personnel (such as specific issues

related to officeholding) did likewise.

Personnel, in fact, provoked more party

divisions than any other topic save

taxation. Democrats and Republicans

rarely disagreed on public services is-

sues. Roll calls on public health and

safety as well as those of a miscella-

neous nature (mostly fish and game

legislation), however, were almost twice

as likely to result in party opposition

than those concerning road policy-the

least contentious of all topics.

Party Cohesion

Studies examining the influence of party

on legislative voting are most

useful if they move beyond consideration

of divisions between parties to the

question of unity (cohesion) within them

as well. Fragmentation within par-

ties necessarily affects overall levels

of partisanship; consequently, calculation

of cohesion rates offers a good way to

determine reasons for advances or de

dines in party voting.

To what extent did Democrats and

Republicans in the Ohio House unite as

voting blocs? In order to answer this

question, Rice indices of cohesion have

been calculated for Democrats and

Republicans on all 337 "contested roll

calls." The Rice index was selected

primarily for its simplicity and ease of

operation. The index is derived from

converting the number of "yeas" and

"nays" into percentages of the

total number of party members voting. The

index is then expressed as the absolute

difference between the two percent-

ages.39

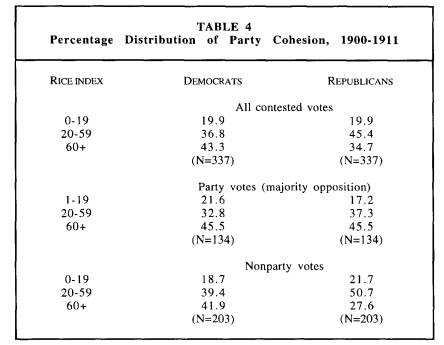

Democrats maintained slightly higher

levels of cohesion throughout the pe-

riod than Republicans (Table 4). Just

over 40 percent of all the roll calls

found 80 to 100 percent of the Democrats

voting as a bloc (60 or more on the

Rice index). By contrast, slightly less

than 35 percent of the roll calls found

Republicans unified to this degree. On

the other hand, Republicans main-

tained moderate levels of unity (60 to

79 percent of party members, or 20 to

59 on the Rice index) on a somewhat

larger share of roll calls than

Democrats. Both parties were evenly matched

at low cohesion rates (50 to 59

percent voting alike, or 0 to 19 on the

index), with less than one-fifth of all

roll calls appearing in this category.

39. For a concise explanation see

Anderson, Watts and Wilcox, 32-33.

|

Partisanship in the Ohio House of Representatives 159 |

|

|

|

Calculation of cohesion indices for party votes (those in which a majority of one party voted in opposition to the other party) separate from nonparty votes produces a somewhat different distribution. Generally, dissent from party ranks was more common among Republicans than among Democrats. Several other studies have suggested that a majority party is more likely to suffer internal factionalism than the minority.40 The lower cohesion rates observed in the Ohio GOP, which held about 59 percent of House seats in five of six assemblies, lend weight to this view. Significantly, however, high cohesion rates for Republicans declined only on nonparty votes. On roll calls in which the parties opposed each other, Democrats and Republicans were equally successful in maintaining high levels of unity, with at least 80 percent of partisans voting together on 45 percent of all roll calls. Thus, Democrats and Republicans had fairly similar cohesion rates on roll calls which found the parties on opposite sides. Roll calls which saw majorities of both parties on the same side produced a very different distribution. Generally, Democrats were able to maintain levels of unity similar to that ob- tained on party votes while their Republican counterparts were more seriously divided. As the minority party in all but one of the Assemblies, Democrats

40. Clubb and Allen, 580; Wiggins, 91. |

|

160 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

had less chance to affect the final outcome on votes and were less likely to deviate in levels of unity on party and nonparty votes. Republicans, on the other hand, had to protect their margin of majority. On roll calls which found the parties on the same side, there could be greater freedom for members of the GOP to desert party ranks. With the parties going separate ways, how- |

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 161

ever, Republican disaffection could

spell defeat. Greater unity was needed, and

(on party votes) Republicans were able

to maintain it.

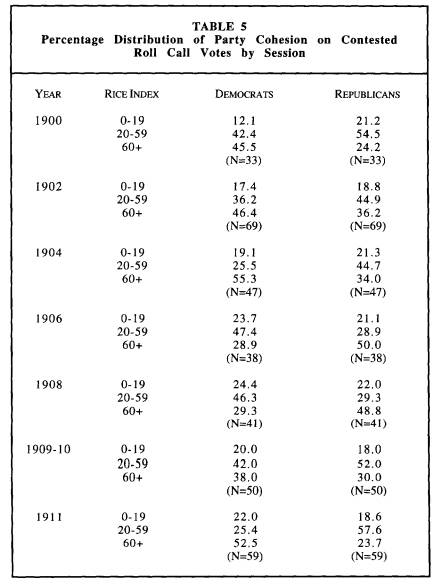

Neither Democrats nor Republicans were

able to maintain high levels of

cohesion in all sessions (Table 5).

Instead, some rather abrupt shifts are ap-

parent. At the beginning of the period,

Republicans were in relative disarray;

less than one-quarter of the contested

roll calls in the Seventy-fourth General

Assembly found this party unified at an

index level of 60 or more. GOP co-

hesion rose noticeably in the following

session, however. Thirty-six percent

of roll calls in 1902 found Republicans

voting at the highest cohesion levels.

Party cohesiveness fluctuated

significantly in the three sessions from 1904 to

1908. Democrats, ironically, experienced

their greatest levels of unity in

1904, when their party's fortunes were

at their nadir. Outnumbered four to

one by Republicans during this session,

the Democrats achieved 80 percent

unity on over 55 percent of the votes.

Democratic unity suffered a serious

setback during the sessions of 1906 and

1908. Specifically, votes producing

a cohesion index of 60 or more reached a

low point during these sessions

while those engendering the least unity

(0 to 19 on the index) were propor-

tionately more numerous than in other

years. Although this study has not at-

tempted to analyze specific reasons for

party unity (or lack thereof), it may be

inferred that a lockhold of House seats

in the state's two largest counties

(Cuyahoga and Hamilton) by reform

Democrats during these years helped cre-

ate something of a progressive

"phalanx" which aroused the antipathy of more

conservative rural elements in the

party.41 While Democrats

were suffering

their most serious divisions, levels of

unity among Republicans were reach-

ing their highest levels. Exactly half

of all votes in 1906, and not quite half

in 1908, found 80 percent of GOP House

members voting together.

Republican cohesion tumbled late in the

period, with the most significant

decrease in high (60 percent plus) rates

occurring between 1908 and 1909-10.

Not too surprisingly, this decline took

place at the time when the party's

progressive faction first successfully

challenged conservatives in controlling

the Republican delegation in the House.

This factional strife between the

progressive and conservative elements of

the GOP thus appears to be the deci-

sive element in lowering rates of party

voting beginning in 1909.

Democrats, on the other hand,

experienced a rise in high cohesion rates during

the final sessions. In 1911, Democrats

achieved 80 percent unity on over

half the contested roll calls. Attaining

majority status in the House appears

to have been a strong-and

successful-inducement for getting Democrats to

vote together. Democratic unity, oddly

enough, seems related to extremes in

the party's fortunes. In only two

sessions during the period did 80 percent or

more of Democrats vote together on over

half the roll calls; in 1911, when

41. Warner, 175-76.

162 OHIO HISTORY

their party controlled the greatest

share of House seats, and in 1904, when

they controlled the least.

Policy Stances

Did Democrats and Republicans take a

wavering and randomized approach

to the issues which divided them, or did

the parties develop reasonably coher-

ent stances on public policy? In order

to answer this question the positions

the parties took on all bills producing

majority opposition votes have been

examined for the purpose of discerning

any common characteristics. The pro-

cess, while somewhat subjective,

provides a means for making some infer-

ences about the presence (or absence) of

a "guiding philosophy" on policy is-

sues among Ohio's major parties during

the Progressive Era.

Although community mores issues produced

fewer partisan divisions than

other policy spheres, the stances of

Democrats and Republicans were nowhere

as consistently opposed as on two

topics, liquor and social behavior, in this

area. Considering legislation concerning

liquor and social behavior, the most

important generalization is that

Republicans favored extending the powers of

the state to regulate stricter standards

of public morality.

Since at least the 1880s, Ohio

Republicans had been more receptive to

temperance legislation than their

opponents, and there is evidence that this

proclivity continued unabated into the

Progressive Era.42 Liquor was a par-

ticularly "hot" topic after

the founding of the Anti-Saloon League at Oberlin

in 1893,43 and the party

votes on the numerous measures concerning this

subject produced unilateral responses:

Republicans were "dry" and Democrats

were "wet." Consistent with

the League's strategy for drying up the state

piecemeal, Republican legislators backed

measures to extend local-option vot-

ing to residenctial districts,

municipalities, and eventually to entire coun-

ties.44 In 1911, with county

option an accomplished fact, Democrats sup-

ported legislation to loosen its

strictures by permitting "wet" urban centers to

retain their saloons in the event their

counties voted dry.45 Republican

sup-

port for the temperance cause was also

evident in GOP endorsement of mea-

42. Ohio Almanac 1973, 359.

43. For a detailed account of the

evolution of the League see, K. Austin Kerr, Organized for

Prohibition: A New History of the

Anti-Saloon League (New Haven, 1985),

66-114.

44. Lloyd Sponholtz, "The Politics

of Temperance in Ohio, 1880-1912," Ohio History, 85

(Winter, 1976), 8-13; see also Norman H.

Clark, Deliver Us From Evil: An Interpretation of

American Prohibition (New York, 1976), 95-97.

45. These bills were introduced after

residents of Newark, a "wet" center, harassed offi-

cials of the Anti-Saloon League,

eventually beating and lynching a young detective employed

by the League. For a detailed account of

this incident, see Charles E. Zartman, "The

Prohibition Question in Licking County,

1908-1912," (M.A. thesis, Ohio State University, 1938),

18-32.

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 163

sures to permit women to vote in

local-option contests, to outlaw "treating"

in saloons, and to increase the state's

liquor tax. Although the last measure

seems, on its face, to grant a certain

imprimatur to the liquor industry, it

should be borne in mind that many

prominent "drys" considered tax increases

as part of an incremental strategy for

eliminating the saloon. GOP support,

under these circumstances, is easier to

comprehend.

Republican support for tighter

regulation of moral conduct extended beyond

liquor legislation to measures embracing

various facets of social behavior.

Championing the cause of "personal

liberty," Democrats supported several

bills to legalize Sunday baseball and

also attempted to block a Republican-

sponsored measure to prohibit the

manufacture and sale of cigarettes. Perhaps

because their party found increasing

favor with immigrants from eastern and

southern Europe, Democrats voted to

compensate a Catholic chaplain at the

state penitentiary, thereby transcending

the bounds of Ohio's Protestant estab-

lishment.

In contrast to bills concerning liquor

and social behavior, those pertaining

to education and rights produced fewer

distinctive patterns of partisanship. No

consistent trends were in evidence at

all on the latter topic while only one

rather generalized characteristic may be

observed about the former. By favor-

ing state action more consistently than

their opponents, Republicans were

more receptive to tailoring educational

policy to uniform standards rather than

allowing local communities to dictate

practices. For instance, a bill mandat-

ing the creation of pension funds for

custodians in city schools won the ap-

proval of House Republicans, as did

measures to expand the state's normal

college system and to regulate the

curriculum in most institutions of higher

education. Republicans did endorse a

bill allowing local school boards to dis-

pense with the election of a district

treasurer, having all financial duties de-

volve on the district clerk. This

concession to local autonomy was to be

granted, however, only if the districts

had designated a state-approved deposi-

tory for school funds.

While Democrats and Republicans

responded to two aspects of commercial

legislation, agriculture/labor and

property rights, inconsistently, they did pur-

sue coherent stances on bills in others

such as business and private finance.

With only a few exceptions, Democrats

favored using government to regulate

these two facets of commercial

enterprise while Republicans were hesitant to

endorse this action. Although the

platforms of both parties frequently found

it expedient to denounce the trusts and

other monopolies in restraint of trade,

the Republicans in one document

recognized the "right of both labor and capi-

tal to combine . ..for the general

good."46 This qualification underscores the

GOP's willingness to grant commercial

enterprise greater freedom from gov-

46. Toledo Blade, June 25, 1901.

164 OHIO HISTORY

ernment restraint and specifically

illustrates party alignments on a number of

votes related to business combinations.

Republicans, for example, approved

a bill legalizing the consolidation of

municipal water companies with street

railroad and electric light

corporations. On the other hand, Democrats sup-

ported two bills designed to expedite

antitrust cases: one which exempted

from prosecution those persons giving

incriminating evidence in trust inves-

tigations, and the other which required

all corporations to file lists of share-

holders with the state.

Beginning in 1901, the Democratic party

of Ohio fell increasingly under

the sway of municipal reformers, most

notably Mayor Tom Johnson of

Cleveland. Supremely important to

Johnson and his followers was the exten-

sion of government regulation of public

utilities, especially the granting of

street railroad franchises and

enlargement of public transportation systems.

Although Ohio Republicans were willing

to endorse formally the referendum

as a means of approving public

transportation grants in their 1908 platform (a

provision which Democrats had attached

to their platform seven years earlier),

party votes on bills which actually

attempted to impose tighter regulation of

the franchising process were

unilaterally supported by Democrats and opposed

by Republicans. As examples, Democrats

lined up in favor of measures

mandating use of the referendum in

franchise-granting procedures, enlarging

the scope of "eminent domain"

statutes along proposed street railroad routes,

granting municipalities the right to

award franchise renewals to companies

other than those holding original

grants, and-most radical of all-sanction-

ing municipal ownership of these

utilities. Consistent with their tradition of

favoring tighter regulation of business,

Democrats in 1900 approved a mea-

sure which divested all corporations

from availing themselves of "fellow ser-

vant" defenses in employer

liability lawsuits. This law had previously been

applied to railroads and now, over

Republican objections, Ohio Democrats

sought its enlargement to include nearly

all commercial enterprises.

Bills introduced in 1900 and 1902

provide the only exception to this pattern

of Democratic approval and Republican

hostility of measures imposing

tighter regulations on business.

Responding to the entreaties of Republican

governors, GOP legislators endorsed

bills during these sessions requiring

corporations doing business in Ohio to

file annual reports with the Secretary

of State. Democrats balked, apparently

less out of hostility to the principle

of these measures than to their

disappointment that they did not go further.47

As indicated, the Republican tendency to

favor a "hands off approach ex-

tended to private finance as well as

business. Specifically, bills expanding

the purview of and/or lifting

restrictions on the functioning of private finan-

cial institutions almost routinely

received the blessing of the GOP. House

47. Warner, 99.

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 165

Republicans, for instance, backed

measures to restore guardianship privileges

to trust companies, to permit accident

and life insurance companies to write

health policies, and to allow

consolidation of savings and loans with safe de-

posit and trust companies. On the other

hand, bills designed to "cap" rates of

interest charged by pawnbrokers and to

impose a fee on banks to cover the

cost of annual examinations by state

inspectors won the approval of

Democrats while alienating the GOP. The

only major exception to the ten-

dency for Democrats to support, and

Republicans to balk, at increased gov-

ernmental regulation of financial

matters occurred in 1904, when GOP legis-

lators endorsed a bill creating a

three-member board to examine the records of

banks and to designate certain ones as

"official depositories" for state funds.

Votes on fiscal policy generally found

Republicans both more receptive to

levying new (or higher) taxes and

embracing a more liberal policy on expendi-

tures than their Democratic opponents.

Some caution should be observed,

however, in regard to the GOP tendency

to endorse tax increases. A majority

of tax measures were debated during

sessions in which a Republican occupied

the governor's chair, and many of these

bills were specifically earmarked as

"administration bills." The

desire to remain loyal to a GOP governor may

have won out over concomitant desires to

turn down increases on the part of

Republican legislators. Further, there

is evidence that Democrats opposed

such important bills as those creating

an inheritance tax and levying excise

taxes on insurance companies and

public-service corporations less out of the

desire to "pinch pennies" than

because they felt these measures were unjustly

construed and even offered tax breaks to

corporations and wealthy persons.48

In addition to favoring a greater number

of levies, Republicans also ap-

peared to endorse tighter state

regulation of the taxation process. As exam-

ples, GOP lawmakers favored bills to

create a state tax commission and to

transfer powers of appointment for local

assessment boards from municipal to

state authority, as well as mandating

that allowances be made to compensate

collectors

of delinquent taxes. On the other hand, Republicans also backed

two bills which loosened the reins of

state control somewhat, allowing mu-

nicipalities greater leverage in raising

funds to meet certain enumerated im-

provements. This seeming contradiction

in stances may be explained by the

fact that one of the principal goals of

the Ohio Democracy throughout this

period was the establishment of

municipal "home rule." Democratic opposi-

tion to these last two bills may have

been based on a desire to refrain from

endorsing measures which, while

increasing the purview of municipalities in

conducting their own financial matters,

stopped far short of granting them the

general independence desired by

"home rule" advocates. The Democrats' en-

thusiasm for granting greater autonomy

to municipalities was in evidence in

48. Ibid., 99-100, 147, 177.

166 OHIO HISTORY

1911, as members of this party endorsed

a bill which established at least

some hope of urban home rule by

abolishing existing city assessment boards,

whose members were appointed by state

rather than local officials.49

Democrats exhibited far more parsimony

in expending public funds than

their Republican colleagues. For

example, two general appropriations bills,

introduced in 1902, received the backing

of the GOP. While the Democrats'

opposition to these bills was initially

related to Republican attempts to rush

passage, the demand for specific

spending cuts was the principal reason for

their hostility.50 Moreover,

of eleven bills dealing with specific appropria-

tions (mostly for increases in

salaries), Republicans supported ten, the

Democrats only one. The lone bill

provoking Democratic support, further-

more, was introduced in 1911, the only

session in which Democrats con-

trolled both the executive and

legislative branches of government. The power

of patronage may have impelled otherwise

fiscally conservative Democrats to

toe the line on this bill.

With one qualification, Democrats and

Republicans exhibited no coherent

patterns in their responses to measures

concerning the operation of govern-

ment. The exception occurred in those

instances when proposed legislation

was seen to benefit, or strengthen, the

fortunes of a party organization. Not

surprisingly, when party interests were

at stake, legislators operated as parti-

sans.

Votes on elections policy sometimes

found the parties adopting inconsis-

tent-even contradictory-stances.

Nonetheless, several bills were closely

tied to specific party interests and

consequently evoked predictable responses

from representatives. In 1904,

Republicans strongly supported a bill to

change the time of municipal elections

from spring to fall. As Ohio's major-

ity party in 1904, the GOP was likely to

increase its strength in municipal

contests by requiring them to be held

concurrently with state and national

elections.51 On two

occasions, House Democrats unanimously backed a bill

to repeal a law prohibiting candidates'

names from appearing more than once

on a ballot. Repeal would likely have

enhanced Democratic prospects by al-

lowing coalitions of independent voters

in the state's urban areas-hitherto

having supported Democrats as

"fusion" candidates-to make a separate ballot

endorsement of these individuals.

Turnabout, however, became fair play after

repeal of the law became fact in 1906.

Four years later, Republicans backed a

bill to reinstate the old law barring

multiple listings of a candidate's name.

In addition to elections policy,

legislators found a number of measures per-

taining to other facets of government,

such as political structure and person-

nel, directly impinging on party

aggrandizement, and responded accordingly.

49. Ibid., 281.

50. Toledo News-Bee, April 18,

1902.

51. Tom L. Johnson, My Story (New

York, 1913), 206-07; Warner, 146.

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 167

Redrawing congressional district

boundaries was a none too subtle technique

for advancing party prospects, and when

in the majority, Democrats and

Republicans alike backed bills designed

to hold the opposition at bay.

Legislation to guarantee minority-party

representation in various offices and

to divest opposition party officials of

appointive and/or supervisory powers

naturally received the endorsement of

representatives of the party benefiting

from such measures.

As indicated above, public services

issues rarely found Democrats opposing

Republicans. This was probably because

party organizations themselves

rarely devoted much attention to

articulating specific positions on these mat-

ters. A search of party platforms for

the period reveals that on only one occa-

sion, in 1905, did a party speak at any

length about a public services topic,

and that in this instance, it related to

singing the praises of legislation already

passed at the party's behest rather than

setting an agenda for the session to

come.52

Opinion concerning legislation relating

to public health/safety issues as

well as roads transcended party lines

since neither Democrats nor Republicans

displayed a consistent policy

orientation in opposition to the other party.

Nonetheless, one topic in this

sphere-that of miscellaneous legislation-

does show partisans moving in opposite

directions. Democrats' traditional

antipathy to extending government

control over matters that many regarded as

the province of "personal

liberty" may have been particularly manifest in

moving members of this party to adopt a

negative stance on miscellaneous

bills, most of which concerned fish and

game. For example, Republicans en-

dorsed measures to require the licensing

of nonresident hunters in Ohio and

also voted to grant authorities greater

leeway in seizing various hunting and

fishing paraphernalia which might have

been used illegally. Also, over

Democratic objections, members of the

GOP voted to augment the authority

of fish and game commissioners by

permitting them to authorize construction

of fish chutes around dams when county

authorities failed to take this action.

In 1909, however, Democrats voted to

ease restrictions on carp fishing by en-

larging the territory in which these

catches could be taken lawfully.

Conclusions

The preceding analysis indicates that

partisanship must not be dismissed as

a significant factor in influencing the

course of roll-call voting in the Ohio

House. On nearly two out of five

contested votes, a majority of Democrats

opposed a majority of Republicans.

Further, on more than one vote in ten,

80 percent of the members of the major

party delegations took an opposing

52. Toledo Blade, May 25, 1905.

168 OHIO HISTORY

stance. Nonetheless, the effects of

party on voting should not be overstated.

Seen from a slightly different

perspective, it is apparent that Democratic and

Republican delegations did not operate

consistently as highly disciplined

forces. The simple fact is that on over

half the roll calls more Democrats and

Republicans were in agreement than in

opposition. Also, compared with leg-

islative bodies of contemporaneous (and

near contemporaneous) periods, the

Ohio House of Representatives tended to

experience fewer party divisions.

Democrats maintained slightly higher

levels of cohesion throughout the pe-

riod than Republicans. Nonetheless, when

cohesion rates are considered sepa-

rately for party (i.e., majority of both

parties in opposition) votes and non-

party votes, the discrepancy between the

parties is found to be entirely due to

Republican disunity on nonparty votes.

Democrats and Republicans main-

tained similar levels of cohesion on

party votes.

There is some evidence that a general

assault on existing party structures by

progressives translated-however

slightly-into a reduction of voting align-

ments based on party. The most

noticeable decline in party voting occurred

beginning in 1909, the same year that

progressive Republicans (who sup-

ported much of the Democrats'

legislative agenda) captured control of the

House delegation. That disaffection in

Republican ranks was mostly respon-

sible for this situation is evident in a

sharp decline in GOP unity beginning

in 1909. Democrats, conversely, saw

their party cohesion increase signifi-

cantly at the close of the period.

Attainment of majority status in 1911, the

first time in twenty years, was

undoubtedly a factor in propelling Democratic

unity to particularly high levels. On

the other hand, Democrats do not appear

to have been immune to disaffection

resulting from progressive challenges.

Democrats experienced particularly low

levels of unity in 1906 and 1908,

when the representative delegations from

the state's two largest counties were

comprised entirely of Democrats with

strong progressive tendencies.

Although ideological battles, such as

progressive versus conservative, ap-

pear to have affected the incidence of

partisan discord, several other factors

seem to have had little, if any,

relationship to these divisions. Rates of con-

flict varied widely regardless of

divided or unified party control of the House

and governorship. Also, with perhaps one

exception, party voting seemed

unaffected by the relative sizes of

Democratic and Republican delegations.

The lone exception occurred in 1904 when

a vast disparity in party delega-

tions was coincident with fairly high

levels of party conflict. However, the

absence of any additional sessions in

which one party was overwhelmingly

outnumbered makes it impossible to

determine whether this phenomenon was

part of a pattern.

Rates of party conflict varied depending

on the type of issue under consider-

ation. Votes on bills relating to the

institution of government and the state's

fiscal policy were most likely to lead

to party splits while those dealing with

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives 169

various public services, such as public

health and roads, were the least con-

tentious. One facet of fiscal

policy-taxation-ranked as the single most

likely topic to find Democrats and

Republicans on opposite sides of the vote.

Perhaps the most surprising finding was

the somewhat modest level of party

divisions registered on bills concerning

moral issues. Slightly less than 40

percent of bills dealing with community

mores found a majority of

Democrats opposing a majority of

Republicans. The Ohio House ranked low

compared to the legislatures of three

other states in the degree of party opposi-

tion on these issues. Two topics within

the mores sphere, however, actually

precipitated a good deal of party

conflict. Temperance and liquor policy

ranked third among the sixteen policy

topics in pitting Democrats against

Republicans, while criminal rights

issues ranked fourth.

Given the somewhat low levels of party

voting, it does not appear that leg-

islators were bound by an

elaborately-defined program. Nonetheless, an ex-

amination of bills which found Democrats

opposing Republicans reveals that

the parties adopted reasonably distinct

positions on certain facets of public

policy.

Party stances were most consistent in

the area of public morality. Ohio

Republicans, who had a long tradition of

supporting the temperance cause,

continued to favor government

proscriptions on drinking as well as a gener-

ally stricter code of morality.

Democrats seemed ill at ease with government

intrusions in this area, even going so

far as to resist GOP attempts at

strengthening state authority in

educational matters.

Despite their "hands off' approach

to mores issues, Democrats were far

more receptive than Republicans to

increasing government oversight of

commercial enterprise. A much-debated

topic in Ohio during the Progressive

Era concerned the regulation of street

railroads and in this, as in other matters

related to business and private finance,

Democrats led the fight for expanded

state control while Republicans resisted

these attempts.

Although votes on taxation were more

likely than any other to produce par-

tisan divisions, it was difficult to

discern any clear-cut pattern in Democratic

and Republican positions. Generally, the

GOP seemed to be somewhat more

receptive to levying new taxes and

imposing stricter state control over the

taxation process, but the apparent

differences may be deceptive. There is evi-

dence that Democratic opposition was

rooted in the belief that Republican

measures were not stringent enough.

Another facet of fiscal policy, however,

reveals a fairly consistent pattern:

when it came to monetary outlays

(expenditures), Democrats were far more

likely than Republicans to embrace

fiscal conservatism.

Neither Democrats nor Republicans took a

clearcut position regarding gov-

ernment operations, except insofar as

bills directly impinged on party for-

tunes. Despite progressive attempts to

stanch excessive partisanship, there is

170 OHIO HISTORY

evidence that on such matters as

apportionment and patronage the parties were

quick to endorse bills which enhanced

their standing and oppose those which

detracted from it.

Two of the three topics comprising

public services issues (public

health/safety and roads) did not evoke

consistent policy stances from either

party. The remaining topic,

miscellaneous legislation, encompassed mostly

fish and game bills and found Democrats-perhaps

motivated by the same

spirit of "personal liberty"

displayed on mores measures-resisting GOP at-

tempts to enact stricter state control

over wildlife management.

JOHN M. WEGNER

Partisanship in the Ohio House of

Representatives, 1900-1911: An Analysis

of Roll-Call Voting

Students of legislative behavior have

long had a penchant for examining the

workings of the United States Congress,

foreign parliaments, and other na-

tional assemblies. They have paid less attention to

state legislatures.

Despite a growing interest in

subnational legislative bodies, research on state

legislatures is still in its infancy.1

Lack of attention by historians to this

area of research is particularly

surprising when one considers the pivotal posi-

tion occupied by these bodies in the

past. Until the 1930s, when the activist

programs of the New Deal tipped government's

"center of gravity" to

Washington, state legislatures exercised

a disproportionate amount of power

over the lives of citizens.2

Although systematic investigations of

legislative behavior at the state level

have taken a "back seat" to

national studies, one facet of research-that per-

taining to party voting-has not been so

sorely neglected.3 Beginning in the

1950s, numerous studies appeared which

assessed the nature and impact of

partisanship on the legislative process

in state assemblies.4 Historians, how-

ever, can take little comfort from these

studies since their ambit has been al-

John M. Wegner teaches American history

courses at colleges in northwest Ohio and south-

east Michigan. He would like to thank

Drs. James Q. Graham and Bernard Sternsher, emeriti

of the Department of History at Bowling

Green State University, and James Marshall, Donna

Christian and the staff of the Local

History and Genealogy Department of the Toledo-Lucas

County Public Libary for their help and

suggestions during the research process.

1. Ballard C. Campbell, Representative

Democracy: Public Policy and Midwestern

Legislatures in the Late Nineteenth

Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1980), 1;

Malcolm E. Jewell,

The State Legislature: Politics and

Practice, second ed., (New York,

1969), 3.

2. Campbell, 2; Philip R. VanderMeer, The

Hoosier Politician: Officeholding and Political

Culture in Indiana 1896-1920 (Urbana, 1985), 3.

3. Jonathan P. Euchner,

"Partisanship in the Iowa Legislature: 1945-1989," paper presented

at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest

Political Science Association, Chicago, Illinois, April 5-

7, 1990, 2.

4. As examples, see Malcolm E. Jewell,

"Party Voting in American State Legislatures," The

American Political Science Review, 49 (September, 1955), 773-91; William J. Keefe,

"Party

Government and Lawmaking in Illinois

General Assembly," Northwestern University Law

Review, 47 (March-April, 1952), 55-71; W. Duane Lockard,

"Legislative Politics in

Connecticut," The American

Political Science Review, 48 (March, 1954), 166-73; and Charles

W. Wiggins, "Party Politics in Iowa

Legislature," Midwest Journal of Political Science, 11

(February, 1967), 86-97.

(614) 297-2300