Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

WILLIAM M. DONNELLY

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division: Major General Robert S.

Beightler and the 37th Infantry

Division, 1940-1945

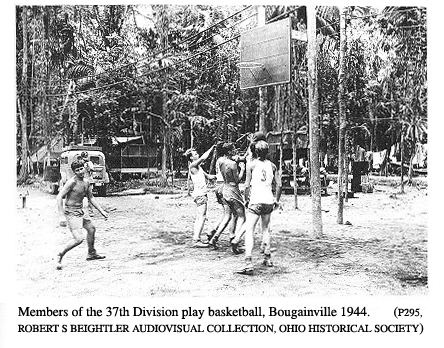

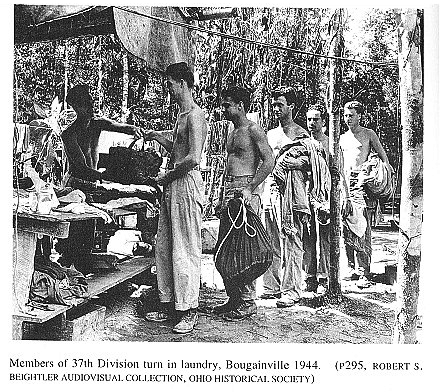

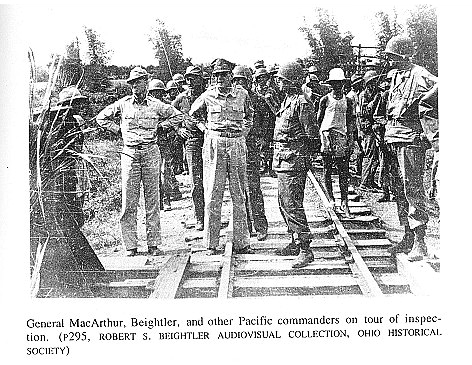

On 15 October 1940 Major General Robert

S. Beightler and the 37th

Infantry Division of the Ohio National

Guard reported for what was supposed

to be a one-year tour of Federal

service. Five years later Beightler and the

Buckeye Division returned to Ohio. Its

original mission had been to expand

to full wartime strength and train

draftees from Ohio at Camp Shelby,

Mississippi. The Buckeyes accomplished

that mission and performed well in

the Louisiana Maneuvers of 1941. These achievements led the

War

Department to select the 37th to be one

of the first American divisions de-

ployed overseas after Pearl Harbor. The

division arrived on Fiji in June 1942,

trained there and on Guadalcanal, after

which it fought two island jungle cam-

paigns against the Japanese on New

Georgia and Bougainville in 1943-1944.

The 37th then landed on the island of

Luzon in the Philippines in January

1945, engaging the Japanese in bitter

street fighting during the liberation of

Manila. The division then conducted a

combined arms attack through the is-

land's northern mountains to the coast.1 In 592 days of combat, the

Buckeyes earned a reputation as one of

the best Army divisions in the Pacific,

at a cost of 1,834 dead and 8,218

wounded.2

William M. Donnelly is a Ph.D candidate

in American history at The Ohio State University.

1. Stanley Frankel, The 37th Infantry

Division in World War II (Washington, D.C., 1948);

Christopher R. Gabel, The U.S. Army

GHQ Maneuvers of 1941 (Washington, D.C., 1991): John

Miller, Jr., Cartwheel: The Reduction

of Rabaul (Washington, D.C., 1959); Robert Ross Smith,

Triumph in the Philippines (Washington, D.C., 1963); Major General Robert S.

Beightler,

"Report on the Activities of the

37th Infantry Division 1940-1945" (n.p., n.d., copy in Box 63/9,

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus,

Ohio).

2. Frankel, The 37th Infantry

Division in World War 11, 387. On the 37th's reputation, see

Frankel, The 37th Infantry Division

in World War II; Beightler, "Report on the Activities of the

37th Infantry Division"; Geoffrey

Perret There's a War to be Won: The United States Army in

World War II (New York, 1991), 237-38, 489-93, 498; the memoirs of a

member of the 37th's

band, Frank F. Mathias, G.I. Jive: An

Army Bandsman in World War II (Lexington, Ky., 1982);

Bruce Jacobs, "Tensions Between the

Army National Guard and the Regular Army", Military

Review, (October, 1993), 5-17; Army Times, 14 October

1944, 10. Beightler noted that "a

reputation for getting things done

certainly gives us an abundance of opportunities to justify and

rejustify it." Letter, 12 May 1945,

Beightler to Major General Dudley J. Hard (a retired Ohio

National Guard officer), Box 1, Folder

2, Robert S. Beightler Papers, Ohio Historical Society

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division

43

The 37th Infantry Division compiled this

record with a strong sense of its

National Guard and Ohio identities.

Before the battle for Manila, the divi-

sion's costliest, these identities were

strong throughout the division. After

Manila and the start of rotation of

troops back to the United States, these

identities weakened at the lower levels,

but they always remained strong

among the division's key senior leaders

and staff.3

The persistence of Guard and Ohio

identities within the division was the re-

sult of a number of factors. Some were

outside the control of the division,

such as the War Department's decision to

fill the 37th in 1940 with draftees

only from Ohio. (This decision was made

primarily to blunt the unpopular-

ity of the draft by having Ohio draftees

trained by fellow Ohioans.) Another

was the War Department's decision in

early 1942 to deploy the 37th overseas.

This spared the division from major

levies to feed the rapidly expanding Army

Ground Forces.4

Reorganizations also tended to preserve

the 37th's character. In early 1942,

the War Department reorganized the

37th as a "triangular" division, a system

in which each level from platoon to

division had three subordinate maneuver

units and which also led to major

changes in the division's artillery and sup-

port units. But while these changes

removed about 7,000 men from the 37th,

they did not add any troops or units

which would dilute the 37th's identity.5

Shortly after Pearl Harbor, the War

Department levied the 37th for engi-

(hereafter, Beightler Papers, OHS)

3. Matthias, G.I. Jive; Beightler,

"Report on the Activities of the 37th Infantry Division";

Letter, 6 April 1945, Beightler to

Lieutenant Colonel William P. O'Connor (a former chaplain

in the 37th), Box 1, Folder 2, Beightler

Papers, OHS; Charles A. Henne, "Battle History of the

3d Bn. 148th Inf: Manila the Unwanted

Battle (4 February through 7 March 1945)," unpub-

lished manuscript, copy in U.S. Army

Military History Institute World War II Veterans Survey,

Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania

(hereafter USAMHI WWII Survey).

4. Frankel, The 37th Infantry Division in World War II, 9-10:

Beightler, "Report on the

Activities of the 37th Infantry

Division". For a good portrayal of the 37th's Ohio character in

1940, see V. Keith Fleming,

"Mobilization of a Rifle Company," National Guard (September,

1980), 26-30, which looks at Kenton's

Company E. 148th Infantry Regiment.

5. "Triangularization" was

developed during the interwar period in response to changes in

tactics and technology that made

obsolete the World War I "square" division of two infantry

brigades, one artillery brigade, and one

regiment each of engineer, quartermaster, and medical

troops. Regular Army divisions began

converting from square to triangular in 1939: the de-

mands of mobilization and the Louisiana

Maneuvers prevented Guard divisions from doing so

until early 1942. See Gabel, The US.

Army GHQ Maneuvers of 1941, 9-13. In triangularizing,

the 37th lost its infantry and artillery

brigade headquarters (the 74th Brigade Headquarters was

converted into the 37th's new

reconnaissance troop and the artillery brigade headquarters was

converted into the division artillery

headquarters battery); the 166th Infantry Regiment; three

artillery regimental headquarters; two

artillery battalions: and reduced the numbers of quar-

termaster and medical troops.

Additionally, at mobilization in 1940 the division's tank company

was detached from the 37th and sent to

the Philippines, where it fought well before surrender-

ing in 1942. While at Camp Shelby, the

637th Tank Destroyer Battalion was organized out of

elements of the division and fought

alongside the division on Luzon. Shelby

L. Stanton, Order

of Battle U.S. Army World War II (Novato, Calif., 1984), 121, 195, 381-82, and Frankel,

The

37th Infantry Division in World War

II, 385-86.

44 OHIO

HISTORY

neers; one group was sent to Northern

Ireland and others became part of a

bridging unit. To replace them, the

division received an engineer battalion

drawn from another Guard division.6

In April 1942, the 147th Infantry

Regiment and the 134th Field Artillery

Battalion were detached from the divi-

sion to form an independent regimental

combat team which was deployed to

the South Pacific. As replacements, the 37th received the

129th Infantry

(Illinois National Guard) and the

6th Field Artillery Battalion (Regular

Army).7

The nature of the 37th's combat

experiences in the Pacific also favored the

maintenance of an Ohio identity. The

relatively short battles on New Georgia

and Bougainville "blooded" the

division but did not gut it; these battles pro-

vided invaluable experience of actual

combat, something training, no matter

how good, can ever fully duplicate. New

Georgia and Bougainville also

strengthened the cohesion and teamwork

within and between units of the divi-

sion, preparing the 37th for its

greatest campaign, the liberation of Luzon.

Even on Luzon, only the battle for

Manila resembled the grinding attrition

that devastated American divisions in

Italy and Northwest Europe. While

cumulative casualties and the Army's

rotation policy began to erode the

Buckeye spirit at lower levels after

Manila, many key leaders followed

Beightler's example by refusing rotation

to remain with the division until V-J

Day.8

However, the most important factor in

maintaining the division's Ohio and

Guard identities was that of Robert

Beightler's command of the 37th Infantry

Division from mobilization to

demobilization, becoming the only National

Guard division commander to do so and

the longest continuously serving com-

6. This was the 117th Engineer

Battalion, drawn from the 29th Infantry Division, Maryland

and Virginia National Guards and the

remnants of the 37th's 112d Engineer Regiment.

Frankel, The 37th Infantry Division

in World War 11, 34.

7. The 129th originally had been part of

the 33d Infantry Division while the 6th Field

Artillery Battalion was created in 1941

out of the 6th Field Artillery Regiment. Stanton, Order

of Battle, 221,

394. The 129th Infantry had lost its First Battalion in 1942 to provide cadre

for a

new regiment. This battalion was rebuilt

in the Pacific with a large number of men from the

37th, including the 147th Infantry.

Letter, 13 February 1947, Colonel John D. Frederick

(Commander of the 129th, 1942-1945) to

Chaplain Frederick Kirker (Editor of the division

history), Box 5, Folder 23, Beightler

Papers, OHS. While of Regular Army origin, two of the

three identified commanders of the 6th

FA during 1943-1945, Howard Haines and Chester

Wolfe, were prewar Ohio Guardsmen.

8. Beightler, "Report on the

Activities of the 37th Infantry Division"; Frankel, The 37th

Infantry Division in World War II; Mathias, G.I. Jive; Letter, 13 May 1945, Beightler to Maude

and Shelby Pickett; Letter, 25 May 1945,

Beightler to Jeanette Hodges, both in Box 1, Folder 2,

Beightler Papers, OHS; Letter, 1 June

1945, Beightler to Colonel S. A. Baxter (former com-

mander of the 148th Infantry), Box 1,

Folder 3, Beightler Papers, OHS, Charles Henne, a pre-

war enlisted Guardsmen in the 148th

Infantry who finished the war as a battalion commander,

thought that the 37th's performance

peaked during the battle for Manila. Henne, USAMHI

WWII Veterans Survey.

|

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye Division 45 |

|

|

|

manding general of an American division in World War II.9 Beightler's extraordinary tenure of command was the result largely of his own considerable abilities. Born in 1892 in Marysville, Ohio, Beightler graduated from Ohio State University with an engineering degree. He enlisted in the Fourth Ohio Infantry in 1911, was commissioned in 1916, and served on the Mexican Border during the 1916-1917 mobilization of the National Guard in response to the actions of Pancho Villa. In World War I, he served in France with Ohio's 166th Infantry, part of the famous 42d "Rainbow" Division.10 After the war Beightler returned to Ohio, working first for the state highway department, then as cofounder of a private engineering firm. He became active in the Ohio Republican Party and in 1939 newly elected Governor John Bricker (best man at Beightler's wedding) appointed him State

9. See Stanton, Order of Battle, 47-188 for a list of divisions and their commanders. Only two other National Guard divisions (the 31st and the 43d) were commanded in combat by Guardsmen, but neither for the same length of time as Beightler did with the 37th. See Jacobs, "Tensions." 10. The 42d Division was nicknamed the "Rainbow" because it was created in 1917 out of National Guard units from twenty-six states and the District of Columbia. See R.M. Cheseldine, Ohio in the Rainbow: Official Story, of the 166th Infantry, 42d Division in the World War (Columbus, Ohio, 1924). Beightler and Cheseldine were good friends; Beightler contributed to this book and wrote Cheseldine often during 1940-45. |

46 OHIO

HISTORY

Highway Director to straighten out that

troubled department. 11

Beightler was typical of many Guard

officers in the interwar period who

made the Guard their "exclusive

hobby": generally, they grew up in small-

town America, were political

conservatives, and were middle class profession-

als able to afford the investment of

time Guard duties required.12 But what

made Beightler stand out among many of

his peers was his determination to

improve his military abilities. In 1926

he graduated first in his class of the

National Guard Officer's Course at the

Command and General Staff School, at

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, followed by

graduation in 1930 from the Army

War College's G-2 course. From 1932 to

1936 he was on active duty with

the Army General Staff in Washington,

working mainly on plans for an in-

terstate highway system. This exposed him to the highest levels of the

Army, an experience not available to the

majority of Guard officers. In the

37th Division Beightler served in a

number of key positions, including divi-

sion chief of staff and commander of the

74th Infantry Brigade, before

Governor Bricker appointed him

commanding general in 1940 to replace

Major General Gilson D. Light, who had

failed his mobilization physical ex-

amination.13

In the 1930s, two related factors

motivated Beightler's professional devel-

opment as a soldier. First, like many

Regular officers, he felt that Japan and

the United States were headed toward a

military confrontation, that America's

citizen soldiers would play a vital role

in this war, and that thus he had to be

prepared, both for the Japanese and for the

U.S. Army.14 Second, Beightler

and many of his fellow Guard officers

harbored a deep distrust of the Regular

Army's intentions concerning the use of

the Guard in wartime. Preparation

11.

This paragraph is based on official biographies prepared during 1940-1945 in

Box 1,

Folder 1, Beightler Papers, OHS;

Richard 0. Davies, Defender of the Old Guard: John Bricker

and American Politics (Columbus, Ohio, 1993), 49; Correspondence between

Beightler and

Bricker in Boxes 1, 29, 36, and 90 of

the John W. Bricker Papers, Ohio Historical Society;

Letter, 2 July 1945, Beightler to Mrs.

John W. Bricker, Box 1, Folder 3, Beightler Papers, OHS.

Also very helpful was Beightler's son,

Robert S. Beightler, Jr., whose January 1995 letter to the

author provided important information on

his father's career.

12. Martha Derthick, The National

Guard in Politics (Cambridge, Mass, 1965), 51-52, 78-82.

The quote is from Letter, 31 May 1939,

Governor John W. Bricker to the Secretary of War,

Box 1, Folder Adjutant General W-Z,

Bricker Papers, OHS.

13. Official Biographies, Beightler

Papers, OHS; Letter, January 1995, Robert S Beightler,

Jr., to author. One reason for the

37th's success in the Pacific was the quality of its Guard field

grade officers, which reflected the

emphasis the division's leadership during the interwar

years had placed on improving military

skills. See Robert L. Daugherty, Weathering the

Peace: The Ohio National Guard in the

Interwar Years, 1919-1940 (Lanham, Md,

1992), 47-57,

181-200.

14. Letter, 29 August 1945, Beightler to

William H. Rabe, Box 1, Folder 3, Beightler Papers,

OHS. In this letter, Beightler commented

that "I am glad now that I spent some years in

following my avocation, for it has meant

a great deal to me during the war." Beightler's image

of himself was that of a

"civilian-soldier.". Letter, 7 October 1945, Beightler to P. J.

Freeman

(an old friend), Box 1, Folder 4,

Beightler Papers, OHS.

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division

47

before a war would enable Beightler

"to demonstrate that an all civilian-com-

ponent division could render equally

good service to that of divisions whose

key officers were largely Regular

Army."15

During his command of the 37th,

Beightler stressed thorough preparation

not just to demonstrate the abilities of

citizen-soldiers, but also because he

was acutely conscious of the costs of

combat. A few days after the war ended,

he wrote a friend that" ... I have

never been able to completely harden my-

self to the sacrifice of American lives.

I have always felt a deep-seated re-

sponsibility to the families of these

men, many of whom might be called my

neighbors." 16

To keep his casualties down, Beightler

emphasized preparation before bat-

tle, especially extensive training on

which he placed great stress from the start

of his command.17 This soon

paid dividends in the Louisiana Maneuvers of

1941, where the 37th began building its

reputation of excellence and Beightler

earned praise as "one of the

best" National Guard commanders.l8 Beightler's

emphasis on training continued

throughout the war; during the campaign in

northern Luzon, Beightler lamented that

the pace of operations usually pre-

vented training to his standard the many

new soldiers arriving to replace casu-

alties and those soldiers rotating home.19

Beightler combined preparation by

extensive training before battle with a

preference, when possible, for using in

battle American firepower instead of

American infantrymen to kill "those

loathsome people."20 This practice was

common throughout the U.S. Army, which

had to answer to an American

15. Letter, 28 August 1945, Beightler to

Major General Ellard A. Walsh, Box 1, Folder 4,

Beightler Papers, OHS. For an overview

of this distrust during the years of Beightler's military

career see Jacobs, "Tensions"

and Mark S. Watson, Chief of Staff; Prewar Plans and

Preparations (Washington, D.C., 1950), 261-63.

16. Letter, 16 August 1945, Beightler to

P. J. Freeman.

17. Speech, Beightler to 37th Division

Officers, (undated but probably December 1940); text

of Beightler's remarks, January 1941,

concerning results of Third Army inspection of 37th; text

of Beightler's 9 December 1941 talk to

Division officers and noncommissioned officers; all in

Box 1, Folder 6, Beightler Papers, OHS.

18. Gabel, The U.S. Army GHQ

Maneuevers of 1941, 117; Memo, 7 October 1941, Lieutenant

General Leslie J. McNair for General

George C. Marshall, Box 76, Folder 31, George C.

Marshall Papers, George C. Marshall

Foundation, Lexington, Virginia. This was, however, in

some respects damming with faint praise

from General McNair, who did not like or trust the

National Guard. Many Guard officers saw

McNair as their greatest enemy among Regular

Army officers. Before his death in 1944

(he was killed by friendly fire in France while

observing operations with the 30th

Infantry Division, a Guard unit), McNair proposed to

Marshall that the Guard be eliminated

after the war. See Jacobs, "Tensions."

19. Frankel, The 37th Infantry

Division in World War II; Beightler, "Report on the Activities

of the 37th Infantry Division";

Mathias, G.I. Jive. Bryon W. Brown believed that the 37th "had

more training than most divisions,"

in Brown, USAMHI WWII Veterans Survey. Letter, 1

June 1945, Beightler to Colonel S.A. Baxter;

Letter, 25 May 1945, Beightler to Brigadier

General Ludwig S. Conelly (a long time

Ohio National Guardsman and former Assistant

Division Commander of the 37th), Box 1,

Folder 2, Beightler Papers, OHS.

20. Letter, 16 August 1945, Beightler to

P. J. Freeman.

48 OHIO

HISTORY

people sensitive to casualties; as a

citizen-soldier, Beightler was perhaps even

more alert to this consideration.

Beightler considered the Philippines prefer-

able as a battlefield to the division's

previous jungle ones because the dense,

confusing terrain of the jungle made it

difficult to use all available means of

firepower. That was not the case in the

Philippines, where for the first time

in the war Beightler was able to employ

fully all his material resources, espe-

cially the formidable capabilities of

American field artillery.21

Beightler's preference saw its greatest

expression in the division's attack on

Intramuros, the extensive Spanish

fortifications that created a walled city

within Manila. The 37th showered

Intramuros with a massive week-long ar-

tillery preparation, then fired about

7,900 rounds in support of the actual as-

sault on 23 February 1945. This action

involved the entire 37th Division

Artillery, the cannon companies of the

division's infantry regiments, three

platoons of tank destroyers, six tanks,

two companies of heavy mortars, and

eight batteries from XIV Corps

Artillery; all told 120 guns ranging from

76mm antitank weapons to 240mm howitzers

were used.22 One story that

made the rounds of the division in

mid-1945 was that Beightler had threatened

to appeal directly to the War Department

if General Douglas MacArthur did

not lift his restrictions on the use of

artillery in Manila.23

While Beightler's papers show that he

held MacArthur, a fellow Great War

veteran of the 42nd "Rainbow"

Division, in high esteem, his experiences dur-

ing 1940-1945 reinforced both his

distrust of the Regular Army as an institu-

tion and his determination to maintain

the 37th's identity as an Ohio National

Guard division. For instance, Beightler

interpreted the transfer of the 147th

Infantry Regiment out of the division as

an attempt by "the powers that be"

to "break up our old closely knit

division."24 Beightler, along with most

Guard officers, resented what he saw as

the condescension and hostility of

many Regular officers. In August 1945

Beightler wrote to Major General

Ellard A. Walsh, head of the National

Guard Association, that his experience

hasn't been too pleasant. My job was

desired by many Regulars who take the atti-

tude that no civilian-component officer

should take over what they assumed to be

their perogatives to hold all the

high-ranking positions in the Army . . . I, my-

self, have been greatly disillusioned,

as I had always been given decent treatment

21. Letter, 18 March 1945, Beightler to

Harry A. Hoopes, Box 1, Folder 2, Beightler Papers,

OHS; Beightler, "Report on the

Activities of the 37th Infantry Division." For an overview of

the role of the "King of

Battle" in the World War II U.S. Army, see Russell F. Weigley,

History of the United States Army (Bloomington, Ind., 1984), 473-74, and Boyd J. Dastrup,

King

of Battle: A Branch History of the

U.S. Army's Field Artillery (Fort

Monroe, Va., 1992), 203-

39.

22. Smith, Triumph in the

Philippines, 291-97.

23. Edwin E. Hanson, USAMHI WWII

Veterans Survey; Mathias, G.I. Jive, 139-40.

24. Letter, 7 October 1945, Beightler to

Lieutenant Colonel Walter N. Davies, Commanding

Officer 147th Infantry, Beightler

Papers, Box 1, Folder 4, OHS.

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division 49

when serving in lower grades on active

duty.25

There was one crucial exception to this

general climate: Beightler formed a

close relationship with Oscar W.

Griswold, who as XIV Corps Commanding

General was Beightler's commander for

most of the his combat service in the

Pacific. In a postwar letter, he told

Griswold that "[Y]ou have consideration

and understanding, you have toleration

for the shortcomings of your subordi-

nates, and particularly for the civilian

soldier in high position, whose status

at times is not too pleasant with some

officers of the Regular Army."26

Beightler wrote his son that Griswold

was "tops" of all the "field soldiers" he

had known, and that "there is no

comparison" between Griswold and the

commander of I Corps, "who

certainly was a 'dummkopf' until the 37th

Division went to his help" during

the campaign in northern Luzon.27

Beightler's image of himself as a

"civilian-soldier" fitted perfectly, he be-

lieved, with the type of soldiers he had

to lead: "I view the problems of my

men through those same civilian-tinted

spectacles. Such an attitude may not

be productive of efficiency postulated

by some, but at least it is human and I

know it pays dividends."28

The success or failure of a division,

whether Regular Army or National

Guard, rests primarily on its leaders.

While on Fiji, prior to entering combat,

the 37th operated an Officer Candidate

School which produced many of the

company grade officers who would carry

the division through the rest of the

war. This school also helped preserve

the Ohio character of this level of the

division's leadership as a majority of

its graduates were Ohioans.29

Comments by veterans show that while the

37th did have some ineffective

25. Letter, 28 August 1945, Beightler to

Walsh. Similar sentiments can be found in other

letters Beightler wrote shortly after

the war. Immediately after VJ Day Beightler became

commander of Luzon Area Command (while

not permanently giving up command of the 37th),

formed to replace XIV Corps as the

administrator of Luzon after XIV Corps was sent to oc-

cupy Japan. This was the equivalent of a

corps command, a lieutenant general's position, but

Beightler kept his two stars. In a 11

October 1945 letter to Walsh, Beightler wrote that he

thought this "advancement in

responsibility, if not in rank." was "simply a sop with an ap-

peasement objective." See letters,

Beightler to Brigadier General D.F. Pancoast, Adjutant

General of Ohio, 4 October 1945;

Beightler to P. J. Freeman, 7 October 1945; and Beightler to

Walsh, 11 October 1945, all in Box 1,

File 4, Beightler Papers, OHS.

26. Letters, 23 April 1945 and 2 May

1945, Beightler to Griswold, Box 1, Folder 2, Beightler

Papers, OHS; Letter, 2 November 1945,

Beightler to Griswold, Box 1, Folder 4, Beightler

Papers, OHS. The quote is from the 2

November 1945 letter from Beightler to Griswold.

Beightler's post-VJ Day letters to

Griswold dropped the salutation "Dear General" and began

"Dear Gris." Griswold was also

popular with the men of the 37th; he attended reunions of the

division in Ohio until prevented by ill

health.

27. Letter, 3 November 1945, Beightler

to Robert S. Beightler, Jr., Box 1, Folder 4, Beightler

Papers, OHS.

28. Letter, 7 October 1945, Beightler to

P. J. Freeman.

29. Frankel, The 37th Infantry

Division in World War 11, 54-55. The roster of graduates of

this school's second class shows that 89

of 121 were Ohioans. Memo: Roster of Cadets, Officer

Candidate School, Second Session, Box 5,

Folder 27, Beightler Papers, OHS.

|

50 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

leaders, particularly during its first combat operations on New Georgia, the overall level of leadership in the division, especially by 1945, was very high and the division's troops greatly respected Beightler.30 In addition to its commanding general, the 37th "was blessed with an ex- traordinary staff and fine regimental and battalion commanders."31 Most of these officers were National Guardsmen, as Beightler intentionally set out to prove that a Guard division "could render equally good service to that of divi- sions whose key officers were largely Regular Army."32 However, Beightler did not let this ambition stand in the way of utilizing talented Regular Army officers. Charles F. Craig, for example, spent the entire war with the 37th, first as the Division Chief of Staff and then as the Assistant Division Commander. (Craig, it should be noted, had a stronger connection to the 37th than other Regulars; in 1940 he was the senior Regular Army instructor

30 See conmments in USAMHI WWII Veterans Survey. 31. Letter, January 1995, Robert S. Beightler, Jr., to author Captain Beightler, a West Point graduate and infantry officer in the 1lth Airborne Division, visited his father several times while both their divisions were serving in the Philippines. 32. Letter, 28 August 1945, Beightler to Walsh. |

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division

51

assigned to the division and then joined

it during mobilization.) Colonel

L.K. White, as executive officer and

then commander of the 148th Infantry

(until he was wounded in action), and

Colonel A.R. Walk, Division Chief of

Staff and White's successor in the 148th,

both earned high praise from

Beightler. Colonel John D. Frederick led

the 129th Infantry during its time

in combat, deserving "full credit for

making the 129th Infantry Regiment one

of the best in the Army." And

Beightler called Lieutenant Colonel George

Coleman, killed in action at Manila

while leading the Second Battalion of the

145th Infantry, "brilliant"

and "one of the most promising young officers I

have ever met."33

These Regular Army officers, however,

were the exception as key division

staff and battalion and regimental

command positions were dominated by

Guardsmen even after the major changes

in the division caused by reorganiza-

tion in early 1942 and the demands of

overseas service and combat after June

1942. Brigadier General Leo M. Kreber

commanded the 37th's artillery from

mobilization to demobilization, earning

high praise from all for his leadership

and professional skills.34 Of

the ten artillery battalion commanders identified,

eight were Guardsmen.35 Of

the thirteen senior division staff officers who

have been identified for this period,

nine were prewar Guardsmen.36 One

of

33. Beightler's 1945 evaluations of

Craig, Walk, and Frederick can be found in Box 5,

Folder 19, Beightler Papers, OHS. See

also Henne USAMHI WWII Veterans Survey; Letter,

2 May 1945, Beightler to Griswold;

Letter, 16 June 1945, Beightler to Colonel L.K. White, Box

1, Folder 3, Beightler Papers, OHS;

Letter, 29 September 1945, Beightler to Colonel John D.

Frederick, Box 1, Folder 4, Beightler

Papers, OHS. On Coleman, see Letter, 22 February 1945,

Beightler to Colonel S.A. Baxter, Box 1,

Folder 2, Beightler Papers. OHS. An informative and

opinionated look at both Regular and

Guard senior officers of the 37th is in Major General

Loren G. Windor's Oral History, U.S.

Army Military History Institute. A prewar Ohio

Guardsman, Windom during 1940-45 served

as the 37th's Assistant Chief of Staff for

Operations and then as commander of the

145th Infantry. In 1959, newly elected Governor

Michael DiSalle appointed Windom

commander of the 37th and Adjutant General of Ohio.

34. This analysis is based on names from

Frankel, The 37th Infantry Division in World War

II, Miller, Cartwheel, and Smith, Triumph in the

Philippines which were then checked in the

National Guard Register for 1939, 1945 and 1951, and the Army Register for

1945. On

General Kreber, see Beightler's

evaluations of him in Box 5, Folders 3 and 19, Beightler

Papers, OHS. Kreber would lead the

reorganization of the 37th in the postwar Ohio National

Guard and command it during its Korean

War service, which was a most frustrating experi-

ence for the division. Mobilized in

January 1952, it moved to Camp Polk, Louisiana, for ex-

pansion to wartime strength with

draftees (though this time not just Ohio ones) and soldiers ro-

tated from Korea. After doing so, the

37th was gutted by levies to support the Army's rotation

policy in Korea and spent the rest of

its Federal service training draftees to provide replace-

ments for other units. See Kreber's

unhappy correspondence with Governor Frank Lausche in

Box 8 of the Frank Lausche Papers, Ohio

Historical Society.

35. All eight of these officers had

served before the 37th's mobilization under either Kreber

or Kenneth Cooper, a member of the 37th

since 1917 and Kreber's executive officer from

1942 to demobilization. These officers

were: 6th Field Artillery, Howard Haines and Chester

Wolfe; 135th Field Artillery, Robert

Chamberlin and John Crossen; 136th Field Artillery, Henry

Shafer and Wilbur Fricke; and 140th

Field Artillery, Chester Wolfe, Clarence Loescher, and

Bud Nellis. Wolfe first commanded the

140th, then took over the 6th.

36. These officers were Ludwig Conelly,

Assistant Division Commander; Loren Windom,

52 OHIO

HISTORY

two engineer battalion commanders was a

Guardsman, as was one of two

commanders of the 37th Reconnaissance

Troop.37 And in the heart of the

37th Infantry Division, its infantry

regiments, Guardsmen also dominated.

Of eight regimental commanders

identified, four were Guardsmen and eighteen

out

of twenty-three infantry

battalion commanders identified were

Guardsmen.38

Beightler was something of an Ohio

chauvinist; concerning the speculation

back home in 1945 that he would run for

governor in 1946, he wrote that

ending his public career as governor of

"the grand old state of Ohio" was an

appealing prospect.39 But he

did not take the plunge into electoral politics as

he believed, incorrectly as it turned

out, that Frank Lausche probably could

not be beaten in 1946. More importantly,

he believed that citizen-soldiers re-

cently freed from the restrictions of

military service would not vote to make

the former enforcer of those

restrictions their new governor.40

Beightler continually stressed the

importance of the 37th's Ohio origins and

the power of the Buckeye spirit:

"We Buckeyes are a neighborly people, but

we are also clannishly Ohio. It has

never been better shown than in the way

Ohio soldiers stick together and fight

together . . . the Ohio spirit at home

and the Ohio spirit on the battle-front

is an unbeatable combination . . . the

37th is, and will remain, a strong and

stalwart piece of Ohio wherever it goes.

The Buckeye spirit has infused the 37th.

It will never be eradicated if we pre-

serve the fundamental virtues and

strengths that have always characterized

Assistant Chief of Staff for Operations;

Raymond Strasburger, Division Signal Officer; Richard

Graham, Division Quartermaster; Demas

Sears, Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence; John

Peters; Sam Davis, Division Special

Services Officer; Wayne Litz, Division Signal Officer; and

Gage Spies, Division Ordnance Officer.

37. These were engineer William Eubank

from Virginia and cavalryman John McCurdy

from Iowa.

38. Regimental commanders in the 145th

Infantry: Cecil Whitcomb and Loren Windom; in

the 148th Infantry: Stuart Baxter and Delbert

Schultz. Battalion commanders in the 145th

Infantry: Richard Crooks (killed in

action at Manila), Herald Smith, Theodore Parker, William

Morr, Russell Ramsey, and Sylvester

DelCorso; in the 148th Infantry: Delbert Schultz, Vernon

Hydaker, James Gall, Charles Henne,

Herbert Radcliffe, and Howard Schultz; in the 129th

Infantry: Albert Firebaugh, Preston

Hundley, and Morris Naudts from the Illinois Guard,

Raymond Scheppach from the Connecticut

Guard, George Wood from the New York Guard,

and Chan Coulter, a prewar member of the

145th Infantry.

39. Letter, 23 August 1945 Beightler, to

Vinton McVickers (political columnist for The

Columbus Citizen), Box 1, Folder 3, Beightler Papers, OHS.

40. There is an extensive correspondence

between the general and his network of contacts

back in Ohio concerning this topic

contained in Box 1 of the Beightler Papers, OHS.

Beightler's reluctance to become

involved in challenging Lausche was complicated by the fact

that, at least until August 1945,

Beightler "was pretty much in agreement with the Governor on

nearly every stand he took" on

issues between Lausche and the General Assembly. Letter, 23

August 1945, Beightler to Vinton

McVickers. On the strength of Beightler's prospective oppo-

nent, Frank Lausche, see Brian Usher,

"The Lausche Era, 1945-1957" in Alexander P. Lamis,

ed., Ohio Politics (Kent, Ohio,

1994), 18-41. Also helpful on this issue was the January 1995

letter to the author from Robert S. Beightler,

Jr.

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division

53

Ohioans."41 While the

"Buckeye spirit" powered the 37th, it was the core of

Ohio Guardsmen and Ohio draftees who

remained from the days at Camp

Shelby that made commanding the 37th

Infantry Division a special thing for

Beightler. In July 1945, with the end in

sight of the campaign in northern

Luzon and thus the imminent release for

rotation home of most of these men,

Beightler wrote that "[S]omehow

there is no particular pleasure to look for-

ward to in commanding the division when

all my faithful 'old timers' are

gone."42

Throughout the 37th's Federal service.

Beightler maintained an extensive

network of correspondents back in

Ohio. This network started with

his

friend, Governor John W. Bricker, who

visited the division several times be-

fore it left for Fiji, and included

numerous personal, political, engineering,

media and National Guard contacts.43

Beightler returned several times to

Ohio during 1940-1942 to build up

personally the links between Ohioans at

home and Ohioans in the 37th. When he

could not get back, he participated

in radio broadcasts (both for national

networks and Ohio stations), an activity

his wife Claire would later adopt.44

Beightler believed that the support of

Ohio for the 37th was a major reason for

the division's great esprit and high

morale even after hard fighting and long

service overseas.45

Beightler used these contacts both to

reinforce the 37th's Ohio identity and

to mobilize support for the division

when he believed it to have been wronged

41. Text of radio address given by

Beightler in 1942 on Ohio stations, Box 1, Folder 7,

Beightler Papers, OHS. Beightler was

quick to react to anything that placed either Ohio or the

37th in an unwarranted unfavorable

light.. In August 1941, LIFE carried a story on the low

morale, bad leadership and unrealistic

training in an unidentified Northern National Guard

Division stationed in the South. The

story discussed how these conditions were symbolized by a

piece of grafitti that appeared all over

the division's camp: "OHIO," standing for "Over the

Hill in October," the month men

drafted under the Selective Service Act of 1940 were to have

been released before Congress extended

their service by an additional year, the implication

being that they would desert once their

original term of service ended. Beightler wrote LIFE,

complaining that the implication of the

story was that the 37th was the unidentified division and

that a "large part of the article

has little application to this division." LIFE printed Beightler's

letter and noted under it that the 37th

"did not provide documentation for LIFE's story on Army

morale." See LIFE, September

8, 1941,6.

42. Letter, 16 July 1945, Beightler to

Harry Hoopes, Box 1, Folder 3, Beightler Papers, OHS.

In November 1945 the 148th Infantry's

officers had a farewell party at the regimental mess

before redeployment back to the United

States. Beightler attended, which for Charles Henne

"made the evening for me. He seemed

most interested in talking to me and the other few

originals." Charles Henne,

"Reduction of the Shobu Group, The 2nd Luzon Campaign", 206,

unpublished manuscript in the USAMHI

WWII Veterans Survey.

43. Box 1 of the Beightler Papers at OHS

holds his surviving correspondence and illustrates

the wide range of the General's contacts

in Ohio. On Governor Bricker's visits, see Frankel,

The 37th Infantry Division, 27, 31-32.

44. Copies of Beightler's radio talks

are in Box 1, Folders 6 and 7, Beightler Papers, OHS.

On Claire Beightler's radio career, see

Letter, 14 September 1945, Beightler to Sam Roderick,

Box 1, Folder 4, Beightler Papers, OHS.

45. This theme often shows up in

Beightler's correspondence with his various Ohio contacts

and he repeated it in his "Report

on the Activities of the 37th Infantry Division."

54 OHIO

HISTORY

by the Army. He relied heavily on Warren

D. Williams of the 37th Division

AEF Veterans Association to provide

items like 18,000 division shoulder

patches, Philippine Liberation ribbons,

photographic supplies, and donations

for the Division Fund. In return,

Beightler sent Williams a captured Japanese

machine gun and worked to provide the

Association with a list of those who

served in the division from 1940 to

1945.46

Through Beightler's efforts the Buckeye

connection was maintained in other

ways, especially by promoting extensive

coverage of the 37th by Ohio news-

papers and radio stations and, when

possible, by the national media. His con-

tacts in Ohio included David Baylor and

Carl George of WGAR Cleveland,

Gene DiMario of the Cincinnati Post, Robert

Harper of the Ohio State

Journal, and Preston Wolfe of the Columbus Dispatch. Frequently,

Beightler

turned to Alan ("Spike")

Drugan of the Columbus Citizen for updates and ad-

vice on the political scene back in

Ohio. The most noticeable results of this

effort were a series of stories by Toledo

Blade reporter Dick McGeorge, who

visited the division in 1944, the visit

of WGAR's Carl George in 1945, and

coverage by Time, Newsweek, and

wire services of the battle for Manila that

brought the 37th national attention for

the first time.47 Additionally, as a

proud Ohio State graduate, Beightler

arranged for the annual shipment to the

division of the Ohio State-Michigan

football game films.48

To redress what he saw as wrongs against

the Buckeyes committed by the

Army, Beightler mobilized his network of

Ohio contacts. In early 1945 the

War Department decided that the battles

on New Georgia and Bougainville

would count as only one campaign, thus

depriving the 37th of a second battle

star. The decision caused Beightler

"great concern," in large part because he

believed that other divisions that had

seen less combat or only as much as the

37th were getting more battle stars. He

alerted the 37th Division Association

to this slight, asking it to begin a

lobbying campaign to reverse this decision

46. Beightler carried on an extensive

correspondencewith Williams and other leaders of the

Association; see Box 1, Folders 2-5,

Beightler Papers, OHS.

47. Memo, 14 September 1945, Beightler

to Commanding Officer 148th Infantry, Box 1,

Folder 4, Beightler Papers, OHS.

Beightler carried on an extensive correspondence with Ohio

journalists; see Folders 2-5, Box 1,

Beightler Papers, OHS. A common theme in this correspon-

dence is how the 37th was not getting

the attention in the national media that its accomplish-

ments warranted. A major reason for this

was the policy of MacArthur to discourage media

attention on anyone but himself in his

theater of operations. See Perret, There's a War to be

Won, 498-99. However, attention from the national media

could backfire. In its coverage of

the "Race to Manila" between

the 37th and the 1st Cavalry Division, Newsweek printed quotes

from Beightler disparaging the

cavalrymen turned infantrymen. Beightler fired off a letter to

Newsweek (which it printed) denying those quotes and sent the

1st Cav's commander a letter

denying the quote and regretting any bad

feelings the article may have generated. Letter, 26

February 1945, Beightler to Editor, Newsweek,

and letter, 26 February 1945, Beightler to Major

General Verne D. Mudge, both in Box 1,

Folder 2, Beightler Papers, OHS.

48. Letter, 22 May 1945, Beightler to

John B. Fuller, Ohio State University Association, Box

1, Folder 2, Beightler Papers, OHS.

|

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye Division 55 |

|

|

|

since his position as a serving officer "prevented me from raising the question with some of my friends in Congress."49 Ultimately fruitless, this effort to gain separate campaign credits for New Georgia and Bougainville nevertheless generated an extensive correspondence in 1945 and 1946. The War Department's decision also had a more practical effect on the sol- diers of the 37th. Eligibility for rotation out of the Pacific Theater of Operations was based on a soldier's having a minimum number of points (set by the theater commander), as computed with a system established by the War Department, with the points being based on a number of factors, including the number of campaigns a soldier had served in. Beightler's Papers contain a number of his letters explaining this to relatives of soldiers whose point to- tals fell below the minimum necessary for rotation. Later in 1945, Beightler's frustration over this issue brought him out into the open when he wrote a number of Ohio congressmen thanking them for their involvement in the fight. Additionally, in his report to the people of Ohio on the 37th's ac-

49. Letter, 24 February 1945, Beightler to Warren D. Willians, Box 1, Folder 2, Beightler Papers, OHS. |

56 OHIO

HISTORY

tivities, Beightler called the decision

"an injustice that shouts for correction"

and vowed that "I'm not through

fighting about that battle-star injustice

yet."50

In the fall of 1945, Beightler became

concerned that divisions that had not

endured as much as the 37th were getting

a higher priority for shipment back

to the United States. Beightler feared

that this would badly damage morale in

the 37th, especially among the remaining

small core of Ohio veterans who

had been overseas now for more than

three years. This was an important con-

sideration, even with the war over, as

"civilian-soldiers" (and their families)

grew increasingly impatient for their

return home and discharge from the

Army. According to the division's

history, watching the departure of the

38th Infantry Division, which had

trained alongside the 37th at Camp Shelby

and "whose combat activities were

comparatively meager, and whose overseas

period was relatively short, broke the

stoical patience" of the 37th's soldiers.

Another consideration was that failure

to bring the 37th home by early

December would interfere with

welcome-home celebrations scheduled for mid-

December across Ohio. After first trying

to resolve the problem through reg-

ular military channels, Beightler

mobilized his network of Ohio contacts to

put pressure on the War Department.

Accompanying this was a flood of let-

ters and telegrams back to Ohio from the

impatient soldiers, reminding politi-

cians of the soldiers' vote. Shortly

afterwards, the 37th found itself sailing

back home.51

Beightler's concern over treatment of

the 37th extended to the division's

place in history. During the war he believed

that the 37th's soldiers were not

receiving the public credit they

deserved. Serving under I Corps in northern

Luzon, he wrote his friend General

Griswold of XIV Corps that the 37th "is

rather low and embittered by the

anonymity with which their operation has

been cloaked" and that the men were

"furious" over another division getting

the credit for capturing an important

objective.52 When General Yamashita,

commander of Japanese forces on Luzon,

praised the 37th in his post-VJ Day

interrogation, Beightler wrote that it

"takes the Japs to give the 37th the

50. Letter, 16 July 1945, Beightler to

Senator Harold H. Burton, Box 1, Folder 3, Beightler

Papers, OHS: Beightler, "Report on

the Activities of the 37th Infantry Division."

51. Frankel, The 37th Infantry

Division in World War II, 364-66; Mathias, G.I. Jive, 206-10;

Letter, 22 September 1945, Beightler to

John Vorys (copy to Clarence Brown) and Memo, 5

November 1945, Beightler to Commanding

General Army Forces Western Pacific, both in Box

1, Folder 4, Beightler Papers, OHS.

Charles Henne placed the blame for most of the discipline

problems on low-point men transferred

into the 37th from other divisions to replace high-point

37th men rotating home. He also thought

little of Beightler's response, a series of sessions

where soldiers brought their gripes

before the commanding general and other high-ranking di-

vision officers. Henne, "Reduction

of the Shobu Group", 200-03. The 38th Infantry Division

(Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia

National Guard) arrived on New Guinea in July 1944,

landed on Leyte in December 1944, then

moved to Luzon in January 1945, where it spent the

rest of the war. It had 786 killed and

2,814 wounded. Stanton, Order of Battle, 123-4.

52. Letter, 2 May 1945, Beightler to

Griswold.

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division 57

credit it so richly deserves."53

After World War I, Beightler had

participated in preparing a book covering

the 166th Infantry's experiences, and he

always maintained great pride in be-

ing a veteran of the famous Rainbow

Division.54 Like many Guard veterans

of World War I, he was angered by

efforts in the interwar period to belittle the

Guard's contribution and then by the

disdain of many Regular officers for the

Guard's contribution during 1940-45. In

1945 Beightler was determined to

produce a history of the 37th's World

War II experiences that would properly

commemorate the service of its

citizen-soldiers and secure the division's repu-

tation. Shortly after VJ Day he created

a Division Historical Board, chaired

by Brigadier General Leo Kreber, to

secure the necessary primary sources and

to produce a rough outline.

Beightler drafted Stanley Frankel,

adjutant of the 148th Infantry, to be the

book's author. Frankel, a native of

Dayton, was a prewar isolationist, maga-

zine writer, unenthusiastic 1941 draftee

and graduate of the Fiji Officer

Candidate School. He had spent much of

his career as an officer trying to get

out of the infantry and into military

journalism, but each attempt had been re-

jected. In August 1945 Frankel, who had

more than enough points for rota-

tion home, was ordered to report to the

commanding general. Beightler, after

apologizing for having had to reject all

those requests for transfers, told

Frankel that he was now going to honor

Frankel's request by having him

write the 37th's history. When Frankel

objected, saying that he would prefer

to rotate home instead, Beightler

replied that Frankel was the man for the job

and that "'[A]fter all, Major . . .

you realize that there is a peace to be

won. "'55

The Division Historical Board and

Frankel began the project in the

Philippines while awaiting shipment back

to the United States. After demo-

bilization, during 1946 and 1947,

Frankel and Chaplain Frederick A. Kirker

prepared drafts of the history that

Beightler spent many hours proofreading and

discussing with other senior veterans of

the division. Robert Ross Smith,

the Army's official historian of the

liberation of Luzon, called the book

53. Memo, 3 October 1945, Beightler to

Captain Stanley A. Frankel, Box 1, Folder 4,

Beightler Papers, OHS. According to

Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger, Beightler and

his senior officers placed much of the

blame for this on their higher echelon commanders dur-

ing most of the northern Luzon campaign,

Major General Innis Swift, commander of I Corps,

and General Walter Krueger, commander of

Sixth Army. See Jay Luvaas, editor, Dear Miss

Em: General Eichelberger's War in

the Pacific, 1942-1945 (Westport,

Conn., 1972), 286, 290.

Eichelberger commanded Eighth Army in

the Philippines and he intensely disliked General

Krueger.

54. R.M. Cheseldine, Ohio in the

Rainbow: Official Story of the 166th Infantry, 42d

Division

in the World Wir, (Columbus, Ohio, 1924). Cheseldine was an old friend

of Beightler and the

two wrote each other often during the

Second World War, much of which Cheseldine spent in

the Pentagon.

55.

Stanley A. Frankel, Frankel-y Speaking About World War II in the

South Pcific,

(privately printed, 1992), 144-46.

58

OHIO HISTORY

(published in 1948) that resulted an

"excellent piece of work that reflects ex-

tensive research."56

For Robert Beightler, in "a

lifetime filled with many achievements, both

military and civilian, command of the

37th Buckeye Division was far and

away the crown jewel. He was immensely

proud of the 37th and the Ohio

National Guard whence it came."57

As well he should have been. In large

part because of his leadership and

abilities, the 37th became one of the best

divisions of the U.S. Army in World War

II while at the same time retaining

in large measure its Ohio and National

Guard character.

56. Frankel, The 37th Division in World

War II; Smith, Triumph in the Philippines, 712.

There is an extensive correspondence

concerning this project in Box 1 of the Beightler Papers

and various drafts in Boxes 2 and 3.

57. Letter, January 1995, Robert S.

Beightler, Jr., to author. Beightler was one of two pre-

war National Guard generals to receive

postwar commissions as a general officer in the

Regular Army. According to his son,

Beightler took the commission because "he wanted to

continue the momentum of his WWII

experience---the greatest achievement of his life."

Beightler's postwar career in the

Regular Army began in 1946 with command of Fifth Service

Command at Ft. Hayes in Columbus.

Following that he was a member of the Army Personnel

Board; commander of the 5th Armored

Division (a training unit); and commander of the

Marianas-Bonins Command and commander of

the Ryukyus Command, both during the Korean

War. He retired in 1953, still a major

general and, according to his son, "somewhat embit-

tered" at not getting the

professional recognition of a third star. From his surviving postwar

letters, it appears Beightler believed

J. Lawton Collins (Chief of Staff of the Army, 1949-1953)

responsible in part for this turn of

events. Beightler and Collins apparently had a run-in during

the New Georgia campaign of 1943. See

letter, Beightler to John Bricker (undated, but prob-

ably September 1950), Box 90, Folder

1950 Personal, Bricker Papers, OHS;

Letters, 2

November 1950 and 9 October 1952,

Beightler to John C. Guenther (his former aide in the

37th), VFM 4379, Ohio Historical

Society.

WILLIAM M. DONNELLY

Keeping the Buckeye in the Buckeye

Division: Major General Robert S.

Beightler and the 37th Infantry

Division, 1940-1945

On 15 October 1940 Major General Robert

S. Beightler and the 37th

Infantry Division of the Ohio National

Guard reported for what was supposed

to be a one-year tour of Federal

service. Five years later Beightler and the

Buckeye Division returned to Ohio. Its

original mission had been to expand

to full wartime strength and train

draftees from Ohio at Camp Shelby,

Mississippi. The Buckeyes accomplished

that mission and performed well in

the Louisiana Maneuvers of 1941. These achievements led the

War

Department to select the 37th to be one

of the first American divisions de-

ployed overseas after Pearl Harbor. The

division arrived on Fiji in June 1942,

trained there and on Guadalcanal, after

which it fought two island jungle cam-

paigns against the Japanese on New

Georgia and Bougainville in 1943-1944.

The 37th then landed on the island of

Luzon in the Philippines in January

1945, engaging the Japanese in bitter

street fighting during the liberation of

Manila. The division then conducted a

combined arms attack through the is-

land's northern mountains to the coast.1 In 592 days of combat, the

Buckeyes earned a reputation as one of

the best Army divisions in the Pacific,

at a cost of 1,834 dead and 8,218

wounded.2

William M. Donnelly is a Ph.D candidate

in American history at The Ohio State University.

1. Stanley Frankel, The 37th Infantry

Division in World War II (Washington, D.C., 1948);

Christopher R. Gabel, The U.S. Army

GHQ Maneuvers of 1941 (Washington, D.C., 1991): John

Miller, Jr., Cartwheel: The Reduction

of Rabaul (Washington, D.C., 1959); Robert Ross Smith,

Triumph in the Philippines (Washington, D.C., 1963); Major General Robert S.

Beightler,

"Report on the Activities of the

37th Infantry Division 1940-1945" (n.p., n.d., copy in Box 63/9,

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus,

Ohio).

2. Frankel, The 37th Infantry

Division in World War 11, 387. On the 37th's reputation, see

Frankel, The 37th Infantry Division

in World War II; Beightler, "Report on the Activities of the

37th Infantry Division"; Geoffrey

Perret There's a War to be Won: The United States Army in

World War II (New York, 1991), 237-38, 489-93, 498; the memoirs of a

member of the 37th's

band, Frank F. Mathias, G.I. Jive: An

Army Bandsman in World War II (Lexington, Ky., 1982);

Bruce Jacobs, "Tensions Between the

Army National Guard and the Regular Army", Military

Review, (October, 1993), 5-17; Army Times, 14 October

1944, 10. Beightler noted that "a

reputation for getting things done

certainly gives us an abundance of opportunities to justify and

rejustify it." Letter, 12 May 1945,

Beightler to Major General Dudley J. Hard (a retired Ohio

National Guard officer), Box 1, Folder

2, Robert S. Beightler Papers, Ohio Historical Society

(614) 297-2300