Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

LAWRENCE A. KREISER, Jr..

A Socioeconomic Study of Veterans

of the 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Regiment After

the Civil War

In the closing days of the Civil War,

Major General William Tecumseh

Sherman declared to Union soldiers

preparing to muster out his belief that,

"as in war you have been good soldiers, so in peace you

will make good citi-

zens."1 Many scholars

neglect the second half of Sherman's appeal, general-

izing about the adjustments that

soldiers made to peacetime society rather

than examining in detail how they made

this transition.2 This is

unfortunate

because the change of men from soldiers

to civilians was enormous in num-

bers alone. Of a total Northern

population in 1860 of twenty-two million,

nearly two million men served in the

Federal army. In Ohio, out of a prewar

population of 2,400,000, nearly 304,000

men served in the military.3

Hundreds of thousands of Northern

soldiers were demobilized at the conclu-

sion of the war and had to readjust to

civilian society. Their war-related expe-

riences exercised a profound influence

on how they resumed their places in

civilian society.4

In recent years, military historians

have gained a greater understanding of

the civilian society from which soldiers

are drawn.5 This

understanding is

Lawrence A. Kreiser, Jr., is a Ph.D.

candidate in the Department of History, University of

Alabama.

1. Quotation in Reid Mitchell, Civil War

Soldiers: Their Expectations and Experiences (New

York, 1988), 207. Portions of this paper

were presented at the 1995 Society for Military

History Conference, Gettysburg,

Pennsylvania. The author would like to thank David Skaggs,

Bowling Green State University; Harold

Selesky, The University of Alabama; Robert Gerber,

the 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Memorial Foundation; and Alicia Browne for their com-

ments and help with this essay.

2. Maris A. Vinovskis, "Have Social

Historians Lost the Civil War? Some Preliminary

Demographic Speculations," in Toward

a Social History of the American Civil War:

Exploratory Essays, ed., Maris A. Vinovskis (New York, 1990), 1-3.

3. E.B. Long, The Civil War Day by

Day (New York, 1971), 701; Frederick Dyer, A

Compendium of the War of the

Rebellion, vol. I Number and

Organization of the Armies of the

United States (reprint, New York, 1959), 11.

4. Stuart McConnell, Glorious

Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865-1900

(Chapel Hill, 1992), 15-16; Vinovskis,

"Have Social Historians Lost the Civil War?" 21;

Marcus Cunliffe, Soldiers &

Civilians: The Martial Spirit in America 1775-1865 (Boston,

1968), 429.

5. Some of the best works on the

relations between soldiers and civilian society during the

war are: Bell I. Wiley, The Life of

Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (Baton

Rouge, 1952); Gerald F. Linderman, Embattled

Courage: The Experience of Combat in the

172 OHIO

HISTORY

less certain when scholars examine how

soldiers return to, and influence, so-

ciety.6 Such an analysis for

the Civil War is hindered by the very reluctance

of soldiers to comment upon their

postwar experiences. Many veterans, if

they chose to write after the war,

believed that only their wartime service

would be of interest to readers. Others,

in an effort to repress the horrors of

combat, chose to talk about their

experiences only with those who also

served.7 As we in a

post-Vietnam and Persian Gulf society are reminded,

however, wartime service is a very

formative occurrence that frequently results

in long-term psychological influences.8

The experiences of sixty-one men from

the 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Regiment are employed in this study to

suggest some of the ways that the

Civil War affected the postwar lives of

former soldiers. The key element in

this analysis is a comparison of the

socioeconomic positions of these men in

1860, before they went to war, with

their status ten years later. Such a com-

parison can determine how and why

veterans of the regiment adjusted to the

changes brought about in Ohio by the

Civil War and the ongoing industrial

revolution.9

Several socioeconomic factors are

examined in this work. The marital sta-

tus and family size of veterans are

examined to see if the war interrupted or de-

layed the life course of soldiers.

Occupation is studied to examine what em-

ployment opportunities were available in

Ohio to veterans after 1865 and to

determine if soldiers resumed their

prewar careers or entered new professions.

Ethnicity and military rank also are

analyzed to study how these factors influ-

enced postwar occupational success.

The 103rd was recruited during summer

1862 primarily from Cuyahoga and

Lorain Counties. The regiment was

assigned to the Army of Kentucky in

October 1862 and transferred to the Army

of the Ohio in June 1863, where it

served until the end of the war. The

103rd saw significant action at

Knoxville, Tennessee, in November 1863

and during the Atlanta Campaign

in 1864. Out of a total enlistment of

1,036 volunteers in 1862, the unit suf-

fered forty battle fatalities, fifty-two

men wounded in action, and seventy-three

American Civil War (New York, 1987); Philip Shaw Paludan, "A

People's Contest": The

Union and the Civil War, 1861-1865 (New York, 1988); Reid Mitchell, The Vacant Chair

The

Northern Soldier Leaves Home (New York, 1993).

6. Richard Severe and Lewis Milford, The

Wages of War: When America's Soldiers Came

Home-From Valley Forge to Vietnam (New York, 1989), 266-71.

7. Linderman, Embattled Courage, 266-71.

8. Herbert Hendin and Ann Pollinger

Hass, The Wounds of War: The Psychologic Aftermath

of Combat in Vietnam (New York, 1984); Josefina J. Card, Lives after

Vietnam: The Personal

Impact of Military Service (Lexington, Mass., 1983); Jessica Wolfe, Pamela J.

Brown, and John

M. Kelley, "Reassessing War Stress:

Exposure, and the Persian Gulf War," The Journal of

Social Issues, 49 (1993), 15-31.

9. James M. McPherson, Ordeal By

Fire: The Civil War and Reconstruction (New York,

1982), 583-85; Harold G. Vatter, The

Drive to Industrial Maturity: The U.S. Economy, 1860-

1914 (Westport, Conn., 1975), 43-56.

103rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment After

the Civil War 173

deaths from disease. These casualty

figures place the 103rd slightly below the

average percentage of troops lost by

Ohio regiments.10 After participating in

the last stages of Sherman's Carolinas

Campaign, the unit's survivors were

mustered out in June 1865 near Raleigh,

North Carolina.11

The methodology employed in this study

involved the random sampling of

the 1,000 volunteers of the regiment in

1862.12 These men were organized

into three categories based upon their

final military rank achieved during the

war. Three categories of military rank

were employed: commissioned officer

(colonel, major, captain, and

lieutenant), noncommissioned officer (sergeant

and corporal), and enlisted personnel

(privates). Every other name was taken

from this list and searched for in the

1860 manuscript census of population

for Cuyahoga and Lorain Counties. If a

soldier died during the war either

from disease or as a result of battle,

the name immediately following his was

selected. The marital status, family

size, place of birth, occupation, and

wealth for each individual found was

recorded. The same process for the

individuals taken from the 1860 census

was repeated in the 1870 census. The

initial sample totaled 417 soldiers.

Sixty-one of these men, or 15 percent of

the sample, were found in both the 1860

and 1870 censuses and comprise the

database employed in this project. 13

Those analyzed in this study represent a

cross section of the soldiers in the

103rd. The men in the database reflect

the wartime service of the majority of

the soldiers in the regiment-they joined

the 103rd at its organization and

survived the war with only minor

physical wounds, if any. All of the mem-

bers of the database enlisted in the

regiment during summer 1862, similar to

the great majority of the men in the

unit. The average age of the soldiers in

the data base in 1862 was twenty-six,

compared with an average age in the

regiment of twenty-five.14 Seventy-six

percent of them resided in Cuyahoga

County, compared to 75 percent of the

soldiers in the regiment. Additionally,

62 percent of the soldiers in the

database were enlisted men, compared to 70

10. William F. Fox, Regimental Losses

in the American Civil War, 1861-1865 (Albany, 1893),

526, 528. Overall, 5.1 percent of

soldiers from Ohio died as a result of combat (either in battle

or from wounds) while the 103rd lost 3.8

percent of its men from enemy action. Nearly 9 per-

cent of soldiers from Ohio died as a

result of disease, compared to 7 percent of the men in the

103rd.

11. "103rd Regiment Ohio Volunteer

Infantry," in Personal Reminiscences and Experiences:

Campaign Life in the Union Army, from

1862-1865 (reprint, New York, 1984),

390-444;

Whitelaw Reid, Ohio in the War: Her

Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers, vol. 11 The

History of Her Regiments and Other

Military Organizations (Cincinnati,

1872), 172-74.

12. Roderick Floud, An Introduction

to Quantitative Methods for Historians, 2nd ed.,

(London, 1979), 169-82.

13. In order not to distort the

comparison of the socioeconomic status of veterans in 1860 as

compared to 1870, only soldiers who

lived away from their parents' place of residence during

both of these years were included in the

database.

14. Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank, 303.

The average age of the men in the database is higher

than that of all Union soldier. Slightly

over one-half of all Federal soldiers were under twenty-

five years of age.

174 OHIO HISTORY

percent of the men in the regiment. The

soldiers that comprise the database,

however, do not represent all of the men

who served in the 103rd. Nearly

one-half of the 140 men discharged from

the unit for medical reasons or dis-

abilities were searched for in the 1860

and 1870 censuses, but none of them

could be matched in both years. Thus,

the postwar effects of severe disease

and physical wounds are beyond the scope

of this study.

Military service during the Civil War

interrupted the life course of members

of the 103rd. Slightly under 60 percent

of the men in the database were mar-

ried in 1860, with an average family

size of two children. After the war, vet-

erans' marriage rates increased

dramatically, while their family size remained

stable. Over 60 percent of the unwed

soldiers in 1860 married by 1870, but

the average family size of all married

men remained at two children, below the

national average of four children.15 The

war caused soldiers to delay any im-

mediate plans or thoughts about

marriage. One soldier, Private Harlan

Chapman, expressed such thoughts,

writing to his fiancee shortly after his en-

listment that, "it made my heart

ach to leave you but all of the young men of

our town was enlisting."16

The stability in family size before and after the

war resulted because many soldiers were

away from their wives for extended

periods during the war and those who wed

after the conflict were married for

less than five years.

Occupation was the next factor examined

to study how successfully soldiers

made the transition from wartime to

civilian employment. Many soldiers in

the regiment expressed an eagerness near

the end of the war to return to their

homes, but few specified their future

plans. While waiting to muster out,

Sergeant Chauncey Mead wrote to a

friend, "I don't have anything to do but

hunt and fish but for all that I am getting

mighty anxious to get home."17

Another man recorded in his diary in May

1865, "expect to go home soon and

then my days here will end and I will be

determined to dig for a livelyhood for

the remainder of my days."18 An

analysis of soldiers' postwar occupations

helps to reveal whether these men

resumed interrupted jobs or made a fresh

start by entering into new employment

opportunities.

The prewar occupations of soldiers

analyzed in this study provide a strong

reflection of the types of jobs that

comprised the North's and Ohio's economy

15. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Series A

255-63, "Selected Characteristics of Households:

1790-1957, 11 in Historical

Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1957 (Washington,

D.C., 1960), 16.

16. Harlan P. Chapman to Mary Pitkins,

December 16, 1862. in the Harlan P. Chapman

Papers, Western Reserve Historical

Society Library, Cleveland, Ohio; hereafter cited as

WRHS. All quotations in this paper are

presented in their original form.

17. Chauncey Mead to Kate Litzel, June

8, 1865. Chauncey Mead Letter Collection, photo-

copies, WRHS, hereafter cited as 103rd

MF.

18. Henry A. Mills, May 13, 1865, Henry

A. Mills Personal Journal, microfilm, WRHS.

|

103rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment After the Civil War 175 |

|

|

|

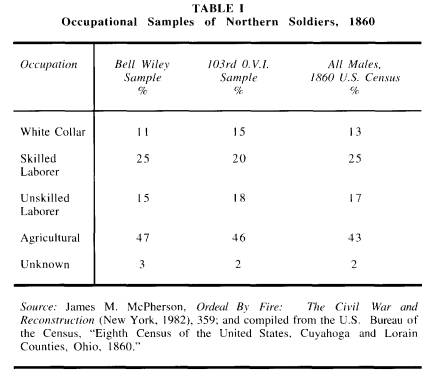

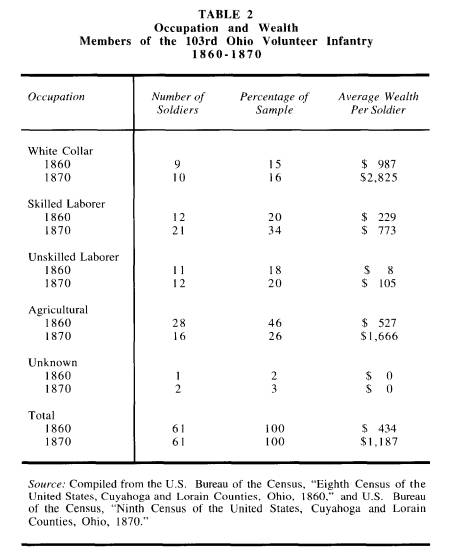

in 1860 (see Table 1). The five occupational classifications used throughout this study are: white collar, such as teachers, manufacturers, and salesmen; skilled laborers, such as craftsmen and construction workers; unskilled labor- ers, such as unskilled industrial workers and apprentices; agricultural, such as farm owners and farm laborers; and unknown, for men who had no occupation listed in the census.19 Veterans of the 103rd made a successful transition to civilian life. The postwar period represented for them a new beginning, in financial terms, without an extended period of dislocation. Between 1860 and 1870, the aver- age assets (or the sum of soldier's property owned and personal wealth) of men in the regiment increased by over two and one-half times, from $434 to $1,187 (see Table 2).20 The average wealth of Ohioans in 1870 was between

19. The occupational classifications employed in this study are derived from James Q. Graham, Dennis Kelly, and Paul D. Yon, Project Heritage: Wood County, Ohio, Index of the 1860 Federal Manuscript Census (Bowling Green, 1978), 22. 20. Throughout this study, wealth statements for 1870 are adjusted for inflation, by using the consumer price index, to represent 1860 real dollars. This was determined by dividing 1870 wealth figures by 1.45, the quotient of the average price of consumer goods in 1870, $135, di- vided by the average price of consumer goods in 1860, $93. |

176 OHIO

HISTORY

$550 and $1,300, indicating that

veterans of the 103rd ranked near the top of

this bracket.21

The rise in wealth among veterans of the

regiment was accompanied by

postwar occupational changes. Skilled

laborer became the most prevalent oc-

cupational category among veterans in

1870, as opposed to the agricultural

jobs that had dominated the regiment in

1860. Soldiers' shift away from

farming and toward skilled labor occupations

corresponds to a similar trend in

Ohio between 1860 and 1870, as the state

became increasingly industrialized

and urbanized during and after the

conflict.22 Members of the 103rd adjusted

to this shift in employment patterns at

a greater rate than the other citizens of

Ohio: 54 percent of the men in the

regiment were employed as either skilled

or unskilled laborers after the war,

compared to 50 percent of the state's popu-

lation.23

Private Jessie Walton and Corporal

Edward Linder's experiences after 1865

typify the ability of veterans to adjust

to the changing employment opportu-

nities available in postwar Ohio. Walton

remained a private throughout the

war while Linder was promoted to

corporal in October 1862. Prior to their

enlistments, Walton was a farm laborer

with no assets while Linder owned

his own farm worth $500. After the war,

Walton became a wholesale dealer

with nearly $700 in assets and Linder

became a skilled laborer with $1,925 in

assets.24 The ability of

these men to undertake new jobs in the business and

retail sector of the economy, jobs that

were not widely available in Cuyahoga

and Lorain Counties in 1860, point out

how veterans could become success-

ful in newly developing sectors of the

economy.25

There are several explanations for the

shift to skilled labor occupations

among soldiers in the 103rd. Many

Northerners in 1861 believed the "Free

Labor" ideology of the Republican

Party, or that the triumph of the federal

21. Data take from Plate XXXIII,

"Wealth," in Statistical Atlas of the United States, Based

on the Results of the Ninth Census

1870, U.S. Bureau of the Census

(Washington, D.C., 1874).

22. Data taken from U.S Bureau of the

Census, Table XCVL, "Manufacturers by Totals of

States and Territories," in A

Compendium of the Ninth Census 1870 (Washington, D.C., 1870),

796; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Series A

195-209, "Population of States, by Sex, Race,

Urban-Rural Residence, and Age: 1790 to

1970," in Historical Statistics of the United States:

From Colonial Times to the Present (Washington, D.C., 1976), 33.

23. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Table

XXX, "Selected Occupations with Age and Sex and

Nativity," in A Compendium of

the Ninth Census, 752.

24. Walton and Linder's assets in 1860

are taken from U.S. Bureau of the Census, "Eighth

Census of the United States, Cuyahoga

and Lorain Counties, Ohio, 1860." Their assets in 1870

are taken from U.S. Bureau of the

Census, "Ninth Census of the United States, Cuyahoga and

Lorain Counties, Ohio, 1870," and

adjusted for inflation to represent 1860 real dollars by using

the consumer price index.

25. William R. Coates, A History of

Cuyahoga County and the City of Cleveland (Chicago,

1924), 505; G. Frederick Wright, A

Standard History of Lorain County, Ohio (Chicago, 1916),

283.

|

103rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment After the Civil War 177 |

|

|

|

government during the Civil War would achieve social mobility for laborers and protect their economic and political liberties. Such a belief may have drawn veterans into labor occupations after the war.26 Or, these men may

26. Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party be- fore the Civil War (New York, 1970), 1139; Thomas R. Kemp, "Community and War: The Civil War Experience of Two New Hampshire Towns," in Toward a Social History of the Civil War, 67; Earl J. Hess, Liberty, Virtue, and Progress: Northerners and Their War for the Union (New York, 1988), 5-7. |

178 OHIO

HISTORY

have been following what historian

Stephan Thernstrom, in his study of so-

cial mobility in a nineteenth century

city, terms the "ideology of mobility."

Thernstrom argues that many Americans

believed they could achieve socioe-

conomic success by moving into new types

of business jobs that, although

not necessarily well-paying, at least

offered the potential for advancement.27

Such a decision would have been an

especially interesting choice for veterans

of the 103rd because men in skilled

labor positions possessed a lower average

wealth in 1870 than veterans in

agricultural occupations. The increased op-

portunities to move into labor

occupations may have attracted veterans to en-

ter into these jobs, however, because,

while they were in the military,

Cleveland grew into an important

manufacturing and industrial center in

northern Ohio.28

The adaptation of members of the

regiment to the changes in employment

patterns also reflects the influences

that military service had on these men.

Many of them started new careers after

1865 because their military service

took them away from their previous

occupations. Private Perry Mapes re-

called how the excitement of military

life appealed to him more than remain-

ing at home to work on his family's

farm.29 Sergeant Chauncey Mead wrote

to his fiancee that after an initial

sampling of Army life, he and the other men

in his company regretted "they did

not enlist sooner."30 To these men, the

chance to enter a new phase in their

lives by joining the military looked bet-

ter than remaining either at home or in

their prewar occupations.31

Military service exposed soldiers in the

103rd to a wider world. Private

Thomas Williams believed that his

wartime service broadened his mental

horizons. He recalled that he:

like thousands of others, was a farmer

boy, born and raised on a farm and knew

nothing of this great world of ours,

outside of two or three counties in the neigh-

borhood of his home. At that time I

thought I knew it all, but at this point in life I

look back to that time, and wonder how

it was that the army mule did not eat me up

when the vegetation was scarce, as I was

so green.32

27. Stephan Thernstrom, Poverty and

Progress: Social Mobility in a Nineteenth Century City

(Cambridge, Mass., 1964), 68-70.

28. Coates, A History of Cuyahoga

County and the City of Cleveland, 504-12.

29. Perry Mapes, "Personal

Experiences Before and During the Civil War," n.d.. typewrit-

ten, 11-13, WRHS.

30. Chauncey Mead to Kate Litzel,

September 27, 1862, Chauncey Mead Letter Collection,

photocopies, WRHS.

31. Glen H. Elder, Jr., "Military

Times and Turning Points in Men's Lives," Developmental

Psychology, 22 (March 1986), 238. Elder argues that military

service alters the life course of

veterans because this experience

"opens up new options and experiences, from exposure to

competent male models to the discipline

of group effort and social responsibility and the wider

perspective associated with

travel." Elder also asserts that

military service represents a

"pronounced break in the lifetime a

discontinuity between past and future."

32. Thomas H. Williams,

"Recollections of Army Life, as Seen by a Private Soldiers," in

Personal Reminiscences and

Experiences, 93.

103rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment After

the Civil War 179

Life on the farm after the war may not

have satisfied the taste for excitement

that soldiers developed while in the

military. Although Army life often was

mundane, the exhilaration of combat

could not be replicated on farms. The

energy and excitement of growing Ohio

cities increasingly beckoned veterans

seeking new jobs and potential

adventures.33

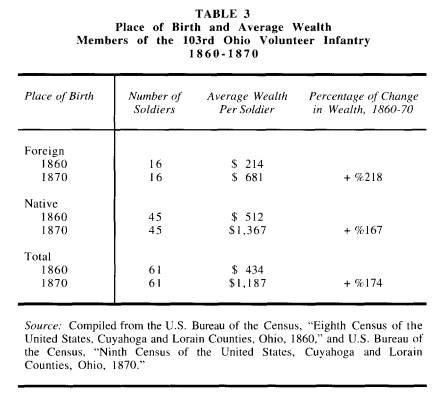

Place of birth was the next factor

examined to determine whether the in-

creased postwar prosperity of men in the

regiment applied equally to soldiers

of foreign and native birth. The

tensions and prejudices against white, for-

eign-born ethnic groups that had

troubled the country during the 1850s de-

clined after the war. A more tolerant

North, however, did not always translate

into increased economic opportunities

for foreigners at a local level.34

Foreign-born soldiers, the majority of

whom were natives of either Ireland

or Germany, experienced a significant

increase in assets between 1860 and

1870, although they still fared worse

than native-born men (see Table 3).35

Foreign-born soldiers achieved their

greatest financial success after the war in

labor related occupations, but they were

much less successful at entering and

succeeding in white-collar occupations.

Their inability to enter these profes-

sions may have been because they did not

have access to the same contacts, or

today what we think of as networks, as

did native-born veterans. They there-

fore did not have equal opportunities to

move into these jobs. This lack of

mobility also was because nativism,

although declining after 1865, did not

disappear entirely.36

Captain George Brady and Private Robert

Crawford provide examples of

how foreign-born veterans, as opposed to

native-born ones, increased their

wealth after the war but missed out on

opportunities to move into

white-collar occupations. Both Brady, who was born in Ireland, and

Crawford, who was born in the United

States, worked in skilled laborer occu-

pations before the war. Neither man was

listed in the 1860 census as pos-

sessing any assets, but both men

experienced a significant increase in wealth

after the war-Brady possessed total

assets of $480 while Crawford possessed

$2,750.37 But Brady had

remained a skilled laborer, while Crawford became a

county official, a white-collar

occupation, in Cuyahoga County. Although

33. James I. Robertson, Soldiers Blue

and Gray (Columbia, 1988), 8.

34. John Higham, Strangers in the

Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 (New

Brunswick, 1985), 13-19; McPherson, Battle

Cry of Freedom, 130-37.

35. The place of birth and total

percentage of foreign-born men in the database are: Ireland

8 (50 percent); Germany 5 (38 percent);

England 1 (6 percent); and Canada 1 (6 percent).

The average age of these men in 1862 was

twenty-five years old, compared to an average age

among the native-born soldiers in the

database of twenty-six years old.

36. Higham, Strangers in the Land, 28.

37. Brady and Crawford's assets in 1870

are taken from the U.S. Bureau of the Census,

"Ninth Census of the United States,

Cuyahoga and Lorain Counties, Ohio, 1870," and adjusted

for inflation to represent 1860 real

dollars by using the consumer price index.

|

180 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

both men increased their assets, Crawford, because he was native born, may have possessed the connections that Brady lacked to move into a job with a higher social status. There are several reasons why foreign-born veterans advanced economically after 1865. Labor struggles in America and Ohio during the late 1860s, a product of industrialization, created an alliance among workers of different ethnic backgrounds in their attempt to achieve better working and living con- ditions. Steven Ross, writing on nineteenth-century industry and labor rela- tions in Ohio, asserts that workers of different ethnic groups were united in their efforts to better their standards of living because of memories of com- mon wartime service. Despite ethnic differences, soldiers understood during the war that they were participating in a common cause. After 1865, the shared wartime efforts of foreign and native-born veterans, now turned work- ers, helped them to win increased levels of pay and economic mobility, al- though at unequal rates.38

38. Steven J. Ross, Workers on the Edge: Work, Leisure, and Politics in Industrializing Cincinnati, 1788-1890 (New York, 1985), 209. |

103rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment After

the Civil War 181

Foreign-born veterans also benefited

from an assimilation process during

their military service. Foreign soldiers

learned a great deal about American

society and culture while in the Army.

Many of them had not been away

from their homes for long periods of

time since their arrival in America, and

their service in the 103rd took them

over relatively wide expanses of the

country. They lived and fought alongside

their native-born comrades, in the

process undergoing what historian Ella

Lonn, in Foreigners in the Union

Army and Navy, terms "Americanization."39 As a

result, foreign-born sol-

diers found less overt discrimination in

their home communities after the war.

This allowed them, similar to Captain

Brady, to achieve greater economic as-

sets, but without necessarily

experiencing an increase in their social status.40

Military rank was the last variable

analyzed to determine postwar economic

success. Reid Mitchell contends in Civil

War Soldiers: Their Expectations

and Their Experiences that the experience of war psychologically transformed

men and altered their personal

identities.41 Service in various leadership posi-

tions, along with their wartime

experiences, transformed soldiers in the 103rd

and influenced their economic status

after 1865. The men in this paper were

organized into three categories based

upon their rank at the end of military

service. These three categories

are: commissioned officers, noncommis-

sioned officers, and enlisted men.

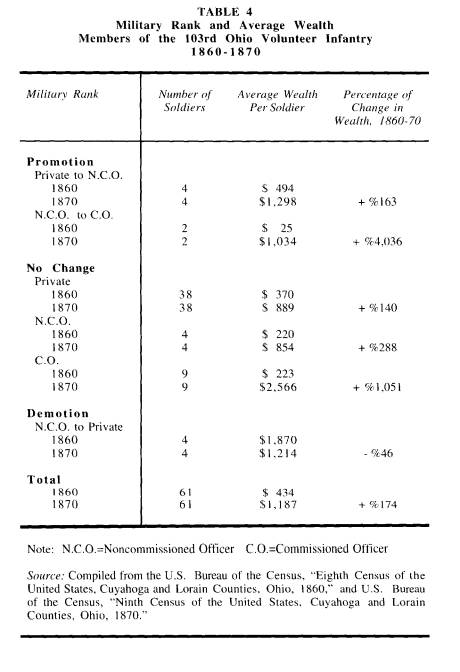

Military rank was a significant factor

in determining the financial status

that veterans of the 103rd achieved by

1870. Men who rose in rank during

the war developed confidence and

leadership skills that enabled them to take

advantage of new postwar employment

opportunities and to improve their fi-

nancial positions (see Table 4).42

First Lieutenant William Hall worked as

an unskilled industrial laborer, with no

assets, prior to his enlistment in the

103rd. Hall was promoted from first

sergeant to second lieutenant in October

1863 and from second to first lieutenant

in August 1864. After the war, Hall

worked as a skilled craftsman in

Cuyahoga County, accumulating total assets

of $1,925 by 1870.43 Men such

as Hall who rose in rank displayed in the

postwar economy the same sorts of

ability and ambition that made them suc-

cessful during wartime.

39. Ella Lonn, Foreigners in the

Union Army and Navy (reprint; Baton Rouge, 1985), 209.

40. Vinovskis, "Have Social

Historians Lost the Civil War?" 29; Michael H. Frisch, Town

into City: Springfield Massachusetts,

and the Meaning of Community, 1840-1880 (Cambridge,

Mass., 1972), 123-29.

41. Mitchell, Civil War Soldiers, 56-89.

42. On the need for Civil War officers

to demonstrate their leadership capabilities to gain the

respect of the soldiers under their

command, rather than relying only on their rank, see

Linderman, Embattled Courage, 43-60.

43. Hall's assets in 1870 are taken from

U.S. Bureau of the Census, "Ninth Census of the

United States, Cuyahoga County, Ohio,

1870," and adjusted for inflation using the consumer

price index to represent 1860 real

dollars.

103rd Ohio Volunteer Regiment After

the Civil War 183

Men promoted to commissioned officers

also took advantage of the prestige

that accompanied their wartime positions

to better their financial standing.

Officers were regarded, and treated,

differently from enlisted troops during the

war. The regimental surgeon, Luther

Griswold, wrote to his wife in 1862

that, "my intercourse is with men

of the best order of talents ... There is a

romance in the whole thing exceedingly

captivating to me and I do not won-

der that men (officers I should say)

become captivated with the army. I do not

see anything I confess very captivating

to the private soldiers."44 Officers

gained from their military rank the

social prestige that, when combined with

demonstrated leadership abilities,

enabled them to improve their economic sta-

tus upon returning to civilian society.45

All of the men in the 103rd did not

undergo a rise in wealth after the war.

By 1870, the assets of soldiers who were

demoted from noncommissioned of-

ficers to privates decreased by 46

percent. Private John Wiley was a farmer

before the war with total assets of

$2,100 in 1860. He mustered into the reg-

iment as a sergeant and was reduced to a

private in August 1864. Wiley re-

turned to his farm after the war and his

assets declined to $900 by 1870.46

Veterans such as Wiley who were demoted

in rank demonstrated a lack of ini-

tiative and leadership ability during

the war that carried over into their postwar

civilian careers. They also may have

been labeled with a social stigma that,

in contrast to the social prestige of

officers, hindered their opportunities for

social and economic advancement.47

In general, soldiers in the 103rd made a

successful transition to civilian so-

ciety after the conclusion of the Civil

War. Veterans were attracted to, and

succeeded in, the labor professions that

increasingly dominated Ohio's econ-

omy. Foreign-born soldiers improved

their financial situations after 1865, al-

though they did not achieve the wealth

and status of their native-born com-

rades. This suggests that during the

war, foreign-born soldiers gained enough

national and local goodwill to enable

them assimilate, at least economically,

more easily into their hometowns.

Finally, men promoted in rank displayed

the same initiative and ability after

the war that they demonstrated during the

conflict to improve their socioeconomic

status. Conversely, soldiers reduced

in rank suffered from a lack of

initiative and ability, and perhaps a social

44. Luther D. Griswold to Jerusha

Griswold, October 2, 1862, Luther D. Griswold Letter

Collection, WRHS.

45. On the close social connection

between soldiers and civilian society, see Robertson,

Soldiers Blue and Gray, 122-29; and Reid Mitchell, "The Northern Soldier

and His

Community," in Toward a Social

History of the American Civil War, 80-88.

46. Wiley's assets in 1860 are taken

from U.S. Bureau of the Census, "Eighth Census of the

United States, Lorain County,

1860." His assets in 1870 are taken from U.S. Bureau of the

Census, "Ninth Census of the United

States, Lorain County, 1870, and adjusted for inflation by

using the consumer price index, to

represent 1860 real dollars.

47. Mitchell, The Vacant Chair, 26-31.

184 OHIO HISTORY

stigma, that limited their chances for

advancement in post-war society.

The conclusions drawn in this study do

not prove absolutely the relation-

ship between military service and

various socioeconomic trends in nine-

teenth-century American society, but the

data do suggest that military service

during the Civil War influenced the

status of Union veterans between 1860

and 1870. More small-unit studies are

needed to clarify the broader implica-

tions of Civil War service on former

soldiers and the society to which they re-

turned in 1865. Similar investigations

also are needed for the veterans of

America's twentieth-century conflicts,

such as the influence of the G.I. Bill

on World War Two veterans and the

readjustment of soldiers who fought in

Korea, the United States first war with

limited national war aims. Once the

influence of wars on the lives of

veterans is further examined, scholars can

more accurately determine the long-range

affects of military service.

LAWRENCE A. KREISER, Jr..

A Socioeconomic Study of Veterans

of the 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Regiment After

the Civil War

In the closing days of the Civil War,

Major General William Tecumseh

Sherman declared to Union soldiers

preparing to muster out his belief that,

"as in war you have been good soldiers, so in peace you

will make good citi-

zens."1 Many scholars

neglect the second half of Sherman's appeal, general-

izing about the adjustments that

soldiers made to peacetime society rather

than examining in detail how they made

this transition.2 This is

unfortunate

because the change of men from soldiers

to civilians was enormous in num-

bers alone. Of a total Northern

population in 1860 of twenty-two million,

nearly two million men served in the

Federal army. In Ohio, out of a prewar

population of 2,400,000, nearly 304,000

men served in the military.3

Hundreds of thousands of Northern

soldiers were demobilized at the conclu-

sion of the war and had to readjust to

civilian society. Their war-related expe-

riences exercised a profound influence

on how they resumed their places in

civilian society.4

In recent years, military historians

have gained a greater understanding of

the civilian society from which soldiers

are drawn.5 This

understanding is

Lawrence A. Kreiser, Jr., is a Ph.D.

candidate in the Department of History, University of

Alabama.

1. Quotation in Reid Mitchell, Civil War

Soldiers: Their Expectations and Experiences (New

York, 1988), 207. Portions of this paper

were presented at the 1995 Society for Military

History Conference, Gettysburg,

Pennsylvania. The author would like to thank David Skaggs,

Bowling Green State University; Harold

Selesky, The University of Alabama; Robert Gerber,

the 103rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry

Memorial Foundation; and Alicia Browne for their com-

ments and help with this essay.

2. Maris A. Vinovskis, "Have Social

Historians Lost the Civil War? Some Preliminary

Demographic Speculations," in Toward

a Social History of the American Civil War:

Exploratory Essays, ed., Maris A. Vinovskis (New York, 1990), 1-3.

3. E.B. Long, The Civil War Day by

Day (New York, 1971), 701; Frederick Dyer, A

Compendium of the War of the

Rebellion, vol. I Number and

Organization of the Armies of the

United States (reprint, New York, 1959), 11.

4. Stuart McConnell, Glorious

Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865-1900

(Chapel Hill, 1992), 15-16; Vinovskis,

"Have Social Historians Lost the Civil War?" 21;

Marcus Cunliffe, Soldiers &

Civilians: The Martial Spirit in America 1775-1865 (Boston,

1968), 429.

5. Some of the best works on the

relations between soldiers and civilian society during the

war are: Bell I. Wiley, The Life of

Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (Baton

Rouge, 1952); Gerald F. Linderman, Embattled

Courage: The Experience of Combat in the

(614) 297-2300