Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

KENNETH W. ROSE

John D. Rockefeller's Philanthropy and

Problems in

Fundraising at Cleveland's

Floating Bethel Mission and the Home

for

Aged Colored People

In discussing attempts to organize

charity and philanthropy in the late nine-

teenth and early twentieth centuries,

historians have devoted much attention to

the institutions being organized-to the

charity organization societies, to phi-

lanthropic clearing houses, or to the

new foundations created by such wealthy,

public-spirited citizens as Andrew

Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Mrs.

Russell Sage-but have given little

concern to the impact such organizing

campaigns had on contemporary charity

work and existing social welfare in-

stitutions. Two institutions in

Cleveland which were affected by local efforts

to organize philanthropy were the

Floating Bethel Mission and the Home for

Aged Colored People. In the cases of

both of these institutions, records lo-

cated in the Rockefeller Family Archives

at the Rockefeller Archive Center in

Sleepy Hollow, New York, provide

valuable information about how these in-

stitutions fared around the turn of the

century. This material suggests some

of the problems associated with

fundraising at a time when donors were care-

ful to give only to worthy projects, and

when organizations were being estab-

lished to tell potential donors which

projects were, and which were not, meri-

torious.

As the wealthiest Clevelander with a widely

known reputation for giving,

John D. Rockefeller was a clear target

for organizations and individuals seek-

ing financial support for a wide array

of projects. From the time of his first

employment in a Cleveland mercantile

house in 1855, Rockefeller had been

making donations to needy individuals

and worthy charitable projects, giving

largely through his church.1 As

his income grew with his success in the oil

business, so too did the flow of his

charitable giving and his reputation as a

philanthropist. It was not unusual for Clevelanders to look

to the

Kenneth W. Rose has been the Assistant

to the Director of the Rockefeller Archive Center in

Sleepy Hollow, New York, since July

1987. He earned a Ph.D. in American Studies from Case

Western Reserve University in Cleveland,

where he also served as a senior editorial assistant

for the first edition of the

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (1987).

1. Rockefeller's first personal ledger,

"Ledger A," now preserved in the John D.

Rockefeller Papers at the Rockefeller

Archive Center, records his earliest charitable gifts.

146 OHIO

HISTORY

Rockefellers for contributions toward

projects they deemed favorable. The re-

sult was a steady stream of

correspondence between citizens of Cleveland,

Rockefeller, and his staff and advisors

in New York and Cleveland. Much of

this correspondence is now accessible to

researchers at the Rockefeller Archive

Center in the papers of John D.

Rockefeller and in the Cleveland project files

in the welfare series in the records of

the Office of the Messrs Rockefeller, the

office Rockefeller established to handle

his personal and philanthropic affairs.2

Material related to the Floating Bethel

Mission and the Home for Aged

Colored People reveals much about the

history of these two institutions,

about the nature of fundraising for

charitable enterprises at the turn of the cen-

tury, and about the process of

Rockefeller philanthropy.

The Floating Bethel Mission

The Floating Bethel Mission and its

founder, the Reverend John Davis

Jones, have received little attention

from Cleveland's historians. Neither the

man nor his mission appears in either

edition of the Encyclopedia of

Cleveland History, and William Ganson Rose's Cleveland: The Making of a

City gives only scant attention to the more spectacular

aspects of Jones'

work.3 Indeed, there appears

to have been little particularly remarkable or dis-

tinctive about the Floating Bethel

Mission: it was one of numerous reli-

2. Researchers can gain access to the

Cleveland material in the John D. Rockefeller Papers

most readily through an unpublished

index to Rockefeller's charity index cards, 1864-1903,

and the published name index for the 394

volumes of letterbooks in the collection, Index to the

John D. Rockefeller Letterbooks,

1877-1918 at the Rockefeller Archive Center (1987), com-

piled by Emily J. Oakhill and Claire

Collier. The Rockefeller Family Archives, Record Group

2, Office of the Messrs Rockefeller,

Welfare Interests series, contains four boxes of material

concerning a number of Cleveland

organizations: the Cleveland Associated Charities, the

Cleveland Automobile Club, the

Children"s Fresh Air Camp, the Cleveland Community Fund,

the Cleveland-Euclid Avenue Association,

the Cleveland Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy, Cleveland"s Federated

Churches, the Floating Bethel Mission, Fourth of July

Celebration-Cleveland, Hiram House, John

D. Rockefeller, Jr."s contribution to the History of

Cleveland by William Ganson Rose,

Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People, the Cleveland

Humane Society, the Children"s

Industrial School and Home, the Jones School and Home for

Friendless Children, the Cleveland

Medical Library, the Cleveland Orchestra Concerts, the

Cleveland Public Library, the Cleveland

School of Art, the Cleveland Foundation, the Phyllis

Wheatley Association, Case School of

Applied Science, and a folder entitled "Cleveland-

Miscellaneous Appeals." In addition

to this material, there is substantial material at the Archive

Center on the Rockefellers' business

interests in Cleveland, real estate holdings in Cleveland,

homes in Cleveland, and contributions to

area churches, as well as personal correspondence

with friends and relatives in the area.

3. Encyclopedia of Cleveland History,

edited by David D. Van Tassel and John

J.

Grabowski (Indianapolis, 1987; 2nd

edition, 1996), Dictionary of Cleveland Biography, edited

by David D. Van Tassel and John J.

Grabowski (Indianapolis, 1996), William Ganson Rose,

Cleveland: The Making of a City (Cleveland, 1950). One local historian who mentions

both

Jones and his relationship with John D.

Rockefeller is Grace Goulder in John D. Rockefeller:

The Cleveland Years (Cleveland, 1972), 100. "Brother Jones had only to

appear at

Rockefeller"s office to receive a

good size check," she reports, with exaggeration.

|

Problems in Fundraising 147 |

|

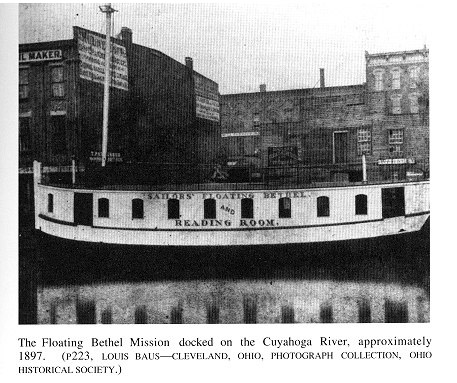

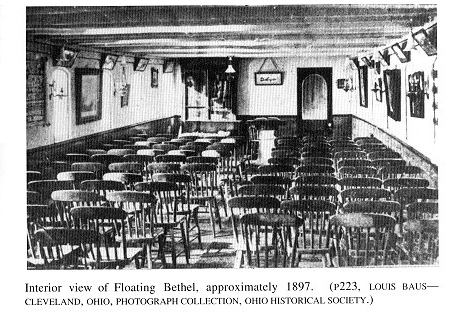

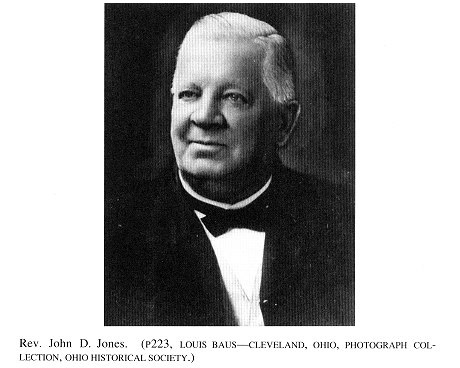

gious-based charitable works undertaken by Clevelanders to save the souls of their fellow citizens, to keep them from sin, and to help them in sickness and in need. Its reports invariably recounted the statistics of its services, report- ing the number of souls touched by its work, if not necessarily saved. For the first six months of 1887, for example, the Mission reported that "117 vis- its were made to the bedside of the sick at their homes...; provisions, medicine and clothing were furnished in all cases when needed. Thirty-two tons of coal were given, and rent paid in seven cases; twenty-two visits were made to the City Hospital and Invalids Home, four sick persons were assisted to their homes, two hundred and fifteen Bethel and funeral services were held, 7299 attended our Bethel services, 1367 arose for prayers." The mission's special task was to serve sailors in the lake shipping trade, and in 1887 it boasted "the largest Sailor Congregation" and "the best located and patronized" reading room on the lakes. So well attended was the reading room that its floor gave way under the strain.4

4. "Floating Bethel & City Mission Work, June 1887," leaflet located in the JDR Papers, Office Correspondence, box 21, folder 166. The collapse of the reading room floor is reported in an undated fundraising card, printed apparently in early 1889: "Our reading room floor |

148 OHIO

HISTORY

Although this "independent

unsectarian work" was under the direction of a

board of trustees, with a president, a

secretary, and a treasurer, the main force

behind its work was the Rev. John Davis

Jones. Indeed, it is the longevity

and dedication of "the one-armed

Missionary" that provides the Floating

Bethel Mission with much of its

distinctiveness. For more than five decades,

the Rev. Jones enjoyed the financial and

moral support of some of the city's

leading citizens for his work along the

docks and among the poor.5

The Rev. John Davis Jones (April 30,

1845-April 5, 1926) became a well-

known figure on the streets of Cleveland

as he ministered to the sick and

needy along the lakefront and in the

flats. The founder of the Floating Bethel

Mission and "a pastor-at-large to

the poor of the city,"6 the Rev. Jones was a

native Clevelander, one of eight

children born to David Jones, one of the

founders of the area's first rolling

mill. According to his obituary, Jones first

went to sea as a cabin boy, later

advancing to mate, before enlisting in the

gave way owing to the great numbers

visiting it, [and] we were compelled to put new timbers

under and refloor a part of it."

Other costs that year included construction of "a new dock on

our river front and, owing to the

building adjoining us being raised a story higher than ours,

made it necessary to extend our three

chimneys...." See "Summary of Current Expenses,"

which lists the amount of debt for

January 1, 1888 and January 1, 1889, signed by William H.

Doan, treasurer, and W. D. Rees,

secretary and treasurer, board of trustees.

5. The Floating Bethel"s work is

described as independent and unsectarian in the June 1887

circular described above. Jones is

described as the one-armed missionary in much of the lit-

erature about him, including one printed

card, dated June 10, 1887, that illustrates the nature of

the support for his work. It reads:

"We, the undersigned, are acquainted with and help to sup-

port the Bethel and City Mission Work

that Rev. J. D. Jones, the one-armed Missionary has

been engaged in for the past twenty

years, and cheerfully recommend his worthy work to the

support of the benevolent." The

undersigned included local political and civic leaders (the

mayor of Cleveland, B.D. Babcock; the

president of city council, W. M. Bayne; the port collec-

tor, William J. McKinnie; the county

treasurer, D.H. Kimberley; and the state senator from the

25th district, George H. Ely); the

managers of the leading newspapers (E.H. Purdue of the

Leader & Herald; and George F. Prescott of the Plain Dealer); many

businessmen associated

with the shipping industry and lake

trade (ship chandlers J.W. Grover & Son, and Upson,

Walton & Company; vessel owners

Thomas Wilson, M.A. Bradley, and Palmer & Benham; and

Cleveland, Brown & Company, iron

merchants); and other prominent citizens: Charles H.

Beardslee (with the Cleveland Gas

Company); William H. Doan, a local oil producer and one

of Rockefeller"s partners; and

Rufus P. Ranney, a prominent local lawyer who had served in

the Ohio Supreme Court. The card is in

the JDR Papers, Office Correspondence, box 21, folder

166.

Shipping interests played a major role

in supporting the Bethel, although that role appar-

ently declined along with business in

the first decade of the twentieth century. When the

Mission incurred a debt of $467.76 in

1901-1902, Jones explained that "the consolidation of

several Steamboat and Dry Dock and Ship

Building Companies has cut down our annual sub-

scriptions over $500.00, and at the same

time our work and expenses have increased." (Jones

to Rockefeller, June 19, 1902,

OMR/Welfare, box 28.) In 1908, when Rockefeller was the

major contributor to its work, the next

largest supporter was the Pittsburgh Steamship Company,

which reduced its annual subscription

from $300 in 1908 to $100 in 1909. N.A. Quilling to

Rockefeller, January 22, 1909.

6. The Rev. E. R. Wright, writing in his

"Church News" column in the Cleveland Leader,

September 26, 1912, offered this

description of Jones. "Everybody in Cleveland" knows his

story, the Rev. Wright wrote.

Problems in Fundraising

149

Union army in 1861. He served in the

Seventh Ohio Volunteer Infantry dur-

ing the Civil War until he was

discharged with a disability; then he re-enlisted

in the navy. While serving on the

gunboat Yantic, he was rendered partly

deaf by a cannon explosion during a

battle. Following the war, Jones worked

on the lakes during the summers and with

the railroads during the winter sea-

son. His work on the railroads led to

further disability: an accident "cost him

an arm and part of a foot."7

Jones' religious work reportedly began

following his own conversion in

1867 "at a noonday service

conducted by the Young Men's Christian

Association." Jones began

distributing religious tracts along the docks, but

soon extended his work into hospitals

and local prisons.8 By the early 1870s,

he was preaching in a Methodist church;

in 1876 he was ordained a sailor

evangelist; and on December 12, 1877, he

was ordained minister of the

Woodland Avenue Presbyterian Church,

where he served until failing health

forced him to retire in 1924. When and

how the Rev. Jones came to establish

the Floating Bethel Mission is unclear,

but the name he chose for his mis-

sion clearly proclaimed its original

intent: he used a boat to take the word of

God to men who made their living on the

open waters of Lake Erie. By the

late 1870s, Jones had, according to

William Ganson Rose, "fitted an old scow

in grand style" to attract sailors

to his ministry; by the mid 1880s, the

Sailors Floating Bethel and City Mission

Chapel was in operation on land at

165 River Street, with Jones as chaplain

and superintendent. A powerful

speaker, Jones reportedly combined

material service with his religious ser-

vices, giving tickets to his Sunday

prayer meetings that permitted their col-

lectors to redeem a certain number for

shoes or clothing.9 In addition to his

own work on behalf of the sick and

needy, the Rev. Jones was active in the

founding of the Jones' Home for

Friendless Children. He claimed to have in-

fluenced his uncle and aunt, Carlos L.

and Mary B. Jones, to donate their land

and home for the orphanage.10

Throughout its history, the Floating

Bethel Mission had trustees and offi-

cers in addition to the Rev. Jones, but

it remained largely a one-man opera-

tion. The Rev. Jones not only held the

services and ministered to those in

7. This brief biographical sketch relies

heavily upon his obituary in an unidentified

Cleveland newspaper, an undated copy of

which is located in the correspondence in the

Rockefeller Family Archives, Office of

the Messrs Rockefeller, John D. Rockefeller series,

box 15, folder 113. Laura W. Jones, his

second wife and widow, sent the obituary to

Rockefeller with a letter dated April 9,

1926. This record group and series will hereafter be

cited as OMR/JDR. For the date of

Jones" death, see the entry for Jones in the list of deaths in

Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 7, 1926.

8. Wright, "Church News," Leader,

September 26, 1912.

9 . Wright, "Church News," Leader,

September 26, 1912; and Rose, Cleveland, 414, 554.

10. Jones to Rockefeller, June 19, 1902,

in a letter that appeals for aid on behalf of both the

Floating Bethel and the Jones Home, in

OMR/Welfare, box 28, folder "Floating Bethel

Cleveland." For the history of the

Jones Home, see "Jones Home of Children"s Services,"

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (1987), 580-81.

150 OHIO

HISTORY

need, but was also the Mission's

fundraiser. Among those he solicited for aid

was an old acquaintance, John D.

Rockefeller. According to Jones, he and

Rockefeller were classmates together at

both the Brownell School and "the

Baptist Church Sunday School" at

the corner of Ohio and Erie streets.11

For

the most part, the preserved

correspondence between Jones and Rockefeller is

very businesslike, with few personal

touches. But there are strong indications

of a personal relationship. When the

Rev. Jones' daughter died in July 1904,

Rockefeller sent his sympathies; and

when he learned that Jones was ill in the

fall of 1905, Rockefeller instructed his

secretary to send him $250 for his per-

sonal use, along with Rockefeller's best

wishes for his recovery of health,

"the suggestion that he look into

the question of osteopathic treatment," and

Rockefeller's personal recommendation of

a specific physician in Cleveland.12

It is likely that Rockefeller began

making donations to the Rev. Jones'

missionary work in a casual way during

the 1870s, but exactly when he made

his first charitable contribution to the

Floating Bethel Mission is not clear.

Rockefeller's charity recording cards

show that by the mid-1880s he was a

regular supporter of the mission.

Between 1882 and 1888, Rockefeller made

annual contributions of $50 to the

mission; he increased his annual subscrip-

tion to $100 in 1889; to $200 in 1899;

and to $500 in 1903. By about

1908, Rockefeller was the largest

contributor to its work.13

During the 1880s two exceptions to these

annual donations occurred, excep-

tions which set a pattern for future

Rockefeller gifts to the Mission. One oc-

curred in 1889, when Rockefeller made

two $100 payments: one to help clear

up the mission's debts, pledged

conditionally upon the remainder of the debt

being pledged "by good and responsible

parties" before a certain date, and the

other a payment toward current expenses.14

This became a regular pattern for

Rockefeller donations to the Mission:

distinguishing between an annual sub-

scription for general support of the

work and donations to meet special needs.

Rockefeller also made occasional gifts

of money to the Rev. Jones for his

11. Jones to J. D. Rockefeller, October

22, 1923, OMR/JDR, box 15, folder 113. In his letter

to Jones' widow on April 9, 1926,

Rockefeller also noted the length of their friendship.

12. See Jones to Rockefeller, February

28, 1905; and Rockefeller to George D. Rogers,

October 17, 1905, in the Rockefeller

Family Archives, Record Group 2, Office of the Messrs

Rockefeller, Welfare series, box 28,

folder entitled "Floating Bethel Cleveland," hereafter

cited as OMR/Welfare. The osteopathic

doctor that Rockefeller recommended was a Dr.

Richardson, "of whom I think

well"; his office was in the Rose Building. On December 13,

1909, the Rev. Jones began a letter of

appeal to Rockefeller by acknowledging "Your kindness

in giving my wife and myself that long,

pleasant auto ride," apparently to a picnic in or near

Royalton. See OMR/Welfare, box 28.

13. See the charity recording cards,

"Cleveland Floating Bethel," card #1, in the John D.

Rockefeller Papers, hereafter cited as

the JDR Papers. The 1903 increase is described in a

letter from John D. Rockefeller, Jr., to

Jones, March 14, 1903, in OMR/Welfare, box 28.

Writing on his father"s behalf, the

younger Rockefeller explained the larger check as an effi-

cient means of avoiding two appeals and

two considerations during the year.

14. See Rockefeller to Jones, June 10,

1889, vol. 20, p. 112, in the letterbooks in the JDR

Papers.

Problems in Fundraising 151

own personal use.

The second exception to the annual gift

came earlier and illustrates the care

with which Rockefeller made donations,

even if they were to old acquain-

tances. In 1886, Rockefeller gave $300

to the Mission, in addition to his

regular $50 subscription for current

expenses. This significant departure from

prior practice is revealing. While in

New York, Rockefeller received an ap-

peal from the Rev. Jones explaining the

$1800 in debts the Mission had in-

curred for its land and buildings.

"I want to share in the good work" of the

Floating Bethel, Rockefeller replied,

but he asked to see "a list of contribu-

tions already obtained." When the

list was received, he advised the Rev.

Jones to call upon L. H. Severance, the

Standard Oil Company cashier, for an

answer to his appeal. Rockefeller, still

in New York, turned to Severance in

Cleveland as his agent and advisor in

this matter: "You may pledge for me

$200.00 or $300.00, and, if your

judgment approves, I will add $100 or $200

more, but kindly ascertain, in the

conversation with him, if others cannot be

found to join and make up the balance.

The more contributors, the better for

the work, for the present and the

future. I would want you to feel assured

from Mr. Doan [treasurer of the Floating

Bethel], also, that their financial af-

fairs are all honestly and carefully

managed."15

Here are several emerging principles of

Rockefeller philanthropy: he is

careful not to be the sole supporter of

the project, wanting others to be found

to join in this work; and he relies on

the expert advice of someone on the

scene who is able to investigate its

soundness more thoroughly than he him-

self could. This reliance on the advice

of others figured prominently in the

fate of later Rockefeller gifts to the

Mission.

As Rockefeller philanthropy became more

and more the function of experts

and advisors rather than the work of

Rockefeller himself, more and more peo-

ple were relied upon for advice with

regard to the Floating Bethel Mission.

Their suggestions varied according to

their opinions of the Rev. Jones and

new ideas about the nature of effective

philanthropy. Their descriptions of the

Rev. Jones and his work, however,

remained remarkably consistent over time.

"His big heart keeps him poor and

his nose on the grindstone all the time,"

wrote L.M. Bowers of the Rev. Jones in

1902. "He cannot keep a dime when

he sees suffering and his pocket is of

course empty most of the time." One

of Rockefeller's closest advisors, Starr

J. Murphy, gave his approval to the

Rev. Jones' work in both 1905 and 1906.

Noting that the number of contri-

butions fell from 256 in 1902 to 212 in

1905, Murphy argued that while "the

work is not of a kind which makes a

general appeal to modern ideas of philan-

thropy...the work seems to be one which

carries a ministry of love and com-

15. See the letters from Rockefeller to

Jones, April 14, 1886, vol. 10, p. 74; and April 19,

1886, vol. 10, p. 124; and Rockefeller

to L. H. Severance, April 19, 1886, vol. 10, p. 122, in the

letterbooks in the JDR Papers.

152 OHIO

HISTORY

fort to many people." "I

should think it worth maintaining," Murphy re-

ported, "at least during the

lifetime of Chaplain Jones.... [who is] a man of

advanced years, and of lovable

personality." Murphy, whose own father en-

gaged in city mission work similar to

that of Rev. Jones for twenty-five

years, recommended continued support at

$500 a year for the Floating Bethel

Mission. 16

Not everyone was so favorably impressed

by the Rev. Jones or the Floating

Bethel Mission. As it spearheaded

efforts to promote greater efficiency and

cooperation among the various charitable

organizations working in the grow-

ing city, the Cleveland Chamber of

Commerce established a Committee on

Benevolent Associations to assess the

work of each charitable organization

and to endorse those it believed were

doing worthy work.17 Such endorsement

was denied to the Floating Bethel

Mission on two grounds. According to

Howard Strong of the Chamber in a letter

to one of Rockefeller's Cleveland

advisors, the Committee on Benevolent

Associations found that the Floating

Bethel Mission "absolutely refused

to cooperate in its relief-giving work with

the other relief organizations of the

city." Moreover, he noted, the Floating

Bethel "seems rather to consider

these organizations as its rivals and to vie

with them for support." Both of

these tendencies ran counter to the commit-

tee's belief "that cooperation is a

fundamental principle of all charities." The

committee also determined that the

Floating Bethel's "administration of char-

ity...is not always of the wisest and

most effective character, tending occa-

sionally to pauperize rather than to

uplift."18 The charge that its actions

tended to pauperize rather than uplift

the poor was perhaps the most damning

charge that could be leveled against a

charitable organization according to the

tenets of modern charitable work at the

turn of the century.

The Chamber's refusal to endorse his

work was the beginning of a long and

bitter dispute between the one-armed

missionary and the proponents of orga-

nized charity in Cleveland. The Rev. Jones believed, according to one

Rockefeller agent, "that all

charitable organizations opposed him and were us-

ing desperate methods to injure his work

in order that they might get his sup-

porters and contributions. He gave me

proof." "Bitter feeling" had been

16. L.M. Bowers to John D. Rockefeller,

Jr., December 26, 1902; Starr Murphy to F.T.

Gates, March 16, 1905; and Murphy to

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., May 1, 1906, in

OMR/Welfare.

17. For a history of the business

community"s efforts to organize more efficient charity and

philanthropy in Cleveland, see Brian

Ross, "The New Philanthropy: The Reorganization of

Charity in Turn of the Century

Cleveland" (Ph.D. dissertation, Case Western Reserve

University, 1989).

18. Howard Strong, Assistant Secretary

of the Cleveland Chamber of Commerce, to N.A.

Quilling, December 21, 1909. One

apparent source of tension, disagreement, and lack of co-

operation was Jones" refusal to

reveal the names of the recipients of his charity. See Wright,

"Church News," Leader, September

26, 1912.

Problems in Fundraising 153

aroused and other organizations had made

"ugly charges" against Jones.19

These charges included an attempt by the

Chamber of Commerce to blame

Jones for the criminal acts of some of

the people he had tried to help. Nathan

A. Quilling, Rockefeller's agent in

Cleveland, reported that "the Chamber of

Commerce made specific charges against

Chaplain Jones and insisted that I

make an investigation through the police

department. I found the charges

groundless as Chaplain Jones is not

responsible for the conduct of the low

class of people he is trying to

help."20

The Chamber's refusal to endorse the

Floating Bethel Mission apparently

led Rockefeller to reconsider his own

support for it, and he asked Quilling to

investigate the Mission, its work, and

the nature of local support for it.

Quilling met with the Rev. Jones on

January 21, 1909, and reported on his

meeting and investigation to Rockefeller

in two letters during the next week,

with an additional report in May.

Quilling agreed with earlier assessments of

Jones and his work, including that of

the Chamber: "He may be overly gen-

erous, and some families helped a year

ago are no more self-respecting or self-

supporting to-day." Still, Quilling

was impressed by the religious nature and

value of Jones' work, as well as its

vastness: "Chaplain Jones is 90% of the

energy of the Floating Bethel; I do not

think it would last long without him.

He is widely known throughout the City

and it is impossible for him to meet

the demands of calls to the bedsides of

the poor, sick, and dying people....

With one helper I cannot understand how

he gets over so large a territory."

The Rev. Jones apparently gave a rousing

account of his work and its increas-

ing strength and support, and won

Quilling's moral support: "My sympa-

thies are decidedly with Chaplain Jones

in his fight with the Chamber of

Commerce and other organizations."

Despite his admiration for the Rev.

Jones, however, Quilling determined that

the local donations were sufficient

to support the Mission's work and that

Rockefeller should eventually cease

his contributions: "I recommend

that you do not contribute to last year's

Bethel deficit..., and that you

gradually decrease your contribution, or, discon-

tinue entirely after this year. The

Bethel is in good shape financially. The

Widlar Estate21 left them

$3,000 last year to be used as they saw fit. Part of

this sum was used in repairing their building,

and $2,000 of the amount re-

mains on hand." Clevelanders, he

believed, "would amply take care of the in-

stitution and...others would give more

if you gave less." Rockefeller's an-

nual donations to the Mission decreased

from $500 between 1904 and 1909 to

19. Quilling to John D. Rockefeller,

January 22, 1909 and January 27, 1909.

20. Quilling to Rockefeller, May 9,

1910.

21. Apparently a reference to the estate

of tea and coffee merchant Francis Widlar, a direc-

tor of the Floating Bethel Mission who

died on June 3, 1907. According to Widlar"s obituary in

the Plain Dealer (June 4, 1907),

he and the Rev. Jones were "lifelong friend[s] and boyhood

chum[s]." In addition to the

obituary, see the entry for Francis Widlar in The Cleveland

Directory of Directors 1905 (Cleveland, 1905).

154 OHIO HISTORY

$400 in 1910 and $325 in 1911, with an

additional $50 for a new Bethel dock

in October 1911. By that date,

Rockefeller had contributed a total of $10,260

to the Floating Bethel Mission.22

By September 1912, however, the Bethel

was $1,500 in debt and needed

another $2,500 for repairs on its

building "demanded by the City Building in-

spectors." Jones was discouraged by

the various battles he was waging. "It

is now a serious question whether I had

not better give up the Bethel work

and seek some other employment," he

wrote to Rockefeller. Money was a

constant headache, and he was growing

weary of the task of raising it. "I find

by past experience that many people are

just as willing to give their money

to our work as they are to give their

teeth to the Dentist. If I was only

skilled in the art of giving laughing

gas I might succeed in getting some of

their money." He vowed to

"make another effort to make a financial success

of the work," and embarked on

another fundraising campaign.23

Asked for his opinion of the Bethel in

1912, Quilling recommended that

Rockefeller "make no further

contributions to this object." A contribution

would not be "a wise and judicious

expenditure of your money," he wrote to

Rockefeller. Much more than in the past,

Quilling now relied upon and

echoed the ideas of organized charity in

assessing the Floating Bethel's work.

The Mission's board took little interest

in its work, knew "little of the chari-

table needs of our poor," and

placed all of the funds at the discretion of one

man, a poor administrator who was likely

to incur deficits repeatedly in the

future. Moreover, Quilling reported,

"the Bethel is playing a lone game.

There is no co-operation with any

organization. No investigation is made to

determine the actual needs in giving,

nor an after-investigation to learn

whether the expenditure was helpful or

harmful. I find that no commendation

is made of the charity end of the Bethel

work by disinterested charity work-

ers."24

Less than a year later, the Rev. Jones

reported to Quilling that the Bethel

was "in better physical and

financial condition than ever before." A new dock

had been built, a new roof put on, the

building had been made fireproof, and,

above all, the Mission was debt-free,

thanks to better financial support from

its own trustees. For his part,

Rockefeller continued to make annual contri-

butions of $250 to the Mission through

the 1910s into the 1920s, with occa-

sional special gifts to the Rev. Jones

or for special needs within the

Mission.25

22. Quilling to Rockefeller, January 22,

January 27, and May 9, 1910; the figures for

Rockefeller's annual donations come from

his charity index cards, correspondence, and office

memoranda that summarize his

contributions to the Floating Bethel Mission.

23. Jones to Rockefeller, September 11,

1912 and October 8, 1912.

24. Quilling to Rockefeller, October 17,

1912.

25. Quilling to Rockefeller, June 17,

1912; on annual giving during this period see the corre-

spondence in OMR/Welfare box 28.

|

Problems in Fundraising 155 |

|

|

|

The creation of Cleveland's Federation for Charity and Philanthropy in 1913 renewed the battle between the Floating Bethel Mission and the propo- nents of organized charity. At Rockefeller's urging, the Rev. Jones reported to his old friend his view of the Federation. For him, the Federation, chaired by a member of Cleveland's Jewish community, represented a coalition of in- terests opposed to the Christian gospel: "Jews, Roman Catholics and liquor dealers have no use for our gospel work," he wrote. "Many of their people and customers have been converted to Christianity through our instrumental- ity." The Bethel's exclusion from the Federation hampered its fundraising by implying that "something [was] wrong" with its work, Jones complained.26 Jones clearly resented the intrusion into the charity field of these "latter day scientific Charity workers." "They have come to Cleveland and want to dom- ineer over those of us who were engaged in the work before they were born," he complained in 1916. "They have succeeded in getting the charity givers to strain at a gnat and swallow a camel," and in the process "made it very hard for me to continue my work." Moreover, he hurled back at these intruders the same charge of pauperizing the poor that they leveled at him, only he returned the charge on a much grander scale. He was convinced that the well-publi- cized work of these new scientific charity workers brought into Cleveland

26. Jones to Rockefeller, October 23, 1913. For similar criticisms of other evangelical charities against the organizers of modern secular philanthropy in Cleveland, see Ross"s Chapter 4, "Modern Philanthropy and Denominational Enterprises," in "New Philanthropy," 210-62. |

156 OHIO HISTORY

"many hundreds of paupers...from

Canada and other countries and all parts of

our own country.... A number have

confessed to me that because of letters

and newspaper clippings they had

received from people who had come here

from their old homes, telling how easy

it was to get relief, they, too, came."

The result was a system that "so

humiliates the best poor of our City, that

they would rather suffer than be

registered with the many paupers." In addi-

tion to attracting paupers to Cleveland

and humiliating the worthy poor,

Jones argued, the system often failed

those most in need. The new scientific

system rendered "poor work":

"we have found sick and dying people in the

greatest distress who have confessed to

us they were already registered by this

Clearing House organization."

Accused often of duplicating the charity of

other organizations, the Rev. Jones

operated from the point of view that ser-

vice to the needy was paramount over

concerns about jurisdiction in specific

cases. He provided assistance first and

asked questions later. He claimed that

Solon Severance, a local banker and

philanthropist, had examined a complaint

that Jones had acted improperly in one

instance, sided with Jones in the han-

dling of the affair, and then withdrew

from the Associated Charities.27

The Rev. Jones' charges and complaints

against organized charity in

Cleveland suggest that these movements

did not proceed smoothly and un-

challenged. More was at stake than

merely the shape and form of charity in

Cleveland, for what emerged was a new

view of the poor as social problems

that needed to be fixed. The Rev. Jones

understood the poor and needy as dig-

nified individuals deserving of help,

with few questions asked. The one-armed

missionary, a veteran charity worker

with a clear religious point of view, and

with ties to some of the oldest families

and wealthiest individuals in

Cleveland, was certainly a formidable

opponent for the younger scientific

charity workers. His Floating Bethel

Mission was exactly the kind of work

they sought to force from the field of

charity, but only failing health in 1924

and death two years later could drive

him from the field. In the spring of

1925, the Floating Bethel's board of

trustees notified donors that Jones's

"increasing physical

disability" had prompted them to sell the property at

1322 West 1th Street and "give up

the Charter of the Institution."

Jones,

the trustees argued, was "in no

condition mentally or physically to carry on

any work": poor eyesight due to

cataracts on both eyes, a failing memory,

and fainting spells made it

"dangerous for him to be on the streets." Yet he

continued to try to raise funds and

minister to the needy, and the trustees felt

compelled to urge his former supporters

to refuse his appeals: "Former sub-

scribers sympathetically inclined will

be doing the Chaplain a great kindness

if they hereafter refuse his appeal of

funds." Proceeds from the sale of the

27. Jones to Rockefeller, August 31,

1916. For a biography of Solon Severance (1834-

1915), see The Dictionary of

Cleveland Biography, edited by David D. Van Tassel and John J.

Grabowski (Bloomington, 1996), 408.

Problems in Fundraising

157

Floating Bethel property had been used

to pay the debts Jones had incurred on

the institution's behalf, and the

remainder was used to establish a trust fund

for Jones and his wife. Jones died in

1926.28

The Home for Aged Colored People

The Home for Aged Colored People fared

much better with the proponents

of organized charity than did the

Floating Bethel Mission, enjoying the sup-

port of the Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy. It also has fared better

with local historians, who have

recounted its story in the standard works on

local African-American history, and it

has fared better over time: the first

non-religious institution organized by

Cleveland blacks continues to serve the

community as the Eliza Bryant Center.29

Efforts to organize the Home were begun

by a long-time resident of

Cleveland, Eliza Bryant. Her mother, a

freed slave from North Carolina, es-

tablished residence in Cleveland in

1858, and her home became a well-known

refuge for blacks coming north until

they could establish their own resi-

dences. Raised in a household that

regularly provided service to other African

Americans, Bryant in 1893 undertook

efforts to organize local women to cre-

ate an institution for poor elderly

blacks who were denied aid and service by

existing old-age homes. By 1895 they had

elected a president and established

a board of trustees, and in September

1896, the Home for Aged Colored

People was incorporated. On August 11,

1897, the Home opened at the cor-

ner of Giddings Street (E. 71st) and

Lexington Avenue. Purchase of the

$2,000 home left the officers with a

debt of $1,400, which they undertook to

raise through benefit parties, socials,

fairs, and appeals to local blacks and to

at least some of Cleveland's white

wealthy elite.30

The Rockefellers were early supporters

of the Home for Aged Colored

People. Records indicate that the first

appeals were directed to Mrs. John D.

Rockefeller, but it is unclear whether

there was any personal acquaintance be-

tween her and the leaders of the Home.

On July 29 and again on September

27, 1898, the Rockefellers contributed

$50 to the Home; in 1898 they made

28. Memorandum of May 27, 1925, Re:

Chaplain J.D. Jones and the Floating Bethel by C.W.

Brand for the Board of Trustees of the

Floating Bethel, in OMR/JDR, box 12, folder 87.

Jones"s "health broke down two

years ago," reported his obituary, and prevented him from

continuing his duties at the Woodland

Avenue Presbyterian Church, and, presumably, his duties

with the Floating Bethel Mission. In his

last letter to Rockefeller"s advisors, Jones reported that

he had been "sick with heart

trouble." See Jones to W.S. Richardson, July 11, 1924,

OMR/JDR, box 15, folder 113.

29. For overviews of its history, see

Russell Davis, Black Americans in Cleveland

(Cleveland, 1972), 192-94, 390; Kenneth

Kusmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape: Black Cleveland,

1870-1930 (Urbana, 1976), 105, 148; and the Encyclopedia of

Cleveland History (1987), 371.

30. See Davis, Black Americans in

Cleveland, 192-94, and Encyclopedia of Cleveland

History, 311.

158 OHIO HISTORY

two payments of $100 each; and they gave

a total of $175 in 1900; $100 in

1901; and in 1902 paid a $500 pledge

toward a mortgage for a new building

for the Home, to which they soon added

$200 on the strength of the fundrais-

ing work of the Home's leaders. By the

spring of 1904, the Rockefellers had

donated more than $1,305 to the

Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People.31

The Rockefellers were thus major

supporters of the Home in its first two

locations, donating a total of $700 to

the $2,275 debt that remained from the

purchase of a new location on Osborne

Street (E. 39th Street) in late 1901.

They also made occasional donations for

current expenses of the Home.

Other white donors during this period

included Samuel Mather and L.C.

Hanna.32 Leaders of the Home

succeeded in paying off the debt on the

Osborne Street house by March 1903, and

the Home enjoyed a stable period

at that location for the next decade.

But when a new home became desirable

in late 1913, the Home's officials once

again looked to the Rockefellers for

aid.

The letters of appeal to John D.

Rockefeller and his advisors from the

Special Fund Committee for the Home for

Aged Colored People clearly

spelled out the need for a new home,

described in some detail the new prop-

erty to be purchased, and explained the

limitations on their fundraising. The

old home housed twelve elderly residents,

with three more applicants awaiting

admission in the new larger house. The

plumbing, bathrooms, and ventila-

tion were poor at the old home, which

needed extensive repair and renovation.

Moreover, the old site at East 39th

Street near Woodland was located next to

an unsightly barrel factory and was

"somewhat away from the people we want

to visit our institution and take an

interest in its welfare." By contrast, the

new home at 4807 Cedar was a large,

fifteen-room, three-story brick house

"in excellent repair," with

"a full cemented cellar [and] an almost new fur-

nace," located such that it

"will put us in direct contact with the colored peo-

ple of our city."33

By 1913, the Home for Aged Colored

People had the endorsement of the

Federation for Charity and Philanthropy,

but this meant little in terms of rais-

ing funds for a new home. The Federation

provided support for current ex-

penses, but did not contribute to

building funds. Indeed, being a member or-

ganization of the Federation was

something of a hindrance in raising a build-

ing fund, as the Home's leaders

explained: "We, as one of the Institutions in

31. See the memorandum on the "Home

for Aged Colored People, Cleveland, Ohio," un-

dated, in the file for the Home in

OMR/Welfare box 29, and see also the following correspon-

dence in the letterbooks in the JDR

Papers: vol. 56, p. 416; vol. 58, p. 192; vol. 65, p. 305; vol.

75, p. 208, vol. 75, p. 269;

vol. 76, p. 19, and vol. 81, p. 356.

32. Cornelia F. Nickens and Marie

Perkins to N.A. Quilling, June 29, 1914.

33. Mrs. Hattie Fairfax, Mrs. Lethia

Fleming, and Mrs. Marie Taylor Perkins to John D.

Rockefeller, December 14, 1913; and

Marie Taylor Perkins to W.S. Richardson. December 15.

1913. Quotes are from the first letter.

|

Problems in Fundraising 159 |

|

the Federation are not permitted to solicit from...subscribers to the Federation, unless there is a special canvas on for us by this same body.... We have so far got very little or no encouragement from the Federation as there seem to be so many greater institutions who have deficits and need more building room that our work seems small and our representative given little encouragement." Support from within the black community was forthcom- ing through "various entertainments" and a general canvass organized by women's clubs, but, as the fundraising secretary put it, "the various colored societies as well as individuals of Cleveland have said WHEN you buy we will help you but we must have money to buy." The home was purchased in January 1914 with a down payment of $5,000 and a $4,000 loan from the Cleveland Trust Company.34 These appeals impressed one Rockefeller advisor, W. S. Richardson, "as worthy." "Such homes for aged colored people, when well managed, are very useful," he reported. "I think Mr. Rockefeller may wisely help. A contribu- tion of $300 would meet with my approval."35 No action was taken, how-

34. Marie Taylor Perkins to W.S. Richardson, December 15, 1913, and N.A. Quilling to John D. Rockefeller, January 29, 1914. Quilling described Perkins, the secretary for the fundraising drive, as "a very bright woman" who for seventeen years had worked as the private secretary in the home of Rockefeller's personal physician, Dr. Hamilton F. Biggar. 35. W. S. Richardson to Starr J. Murphy, December 23, 1913. |

160 OHIO HISTORY

ever, partly because Rockefeller's agent

in Cleveland believed no outside aid

was necessary. "The home for aged

colored people is undoubtedly worthy of

support," Quilling argued,

"but it does seem to me that the sense of duty and

pride of the colored people might be

sufficiently stimulated to support... [the

Home] without outside aid."36

Another factor in delaying action was

that further investigation had revealed

a more troubling issue: the question of improper expenditure of past

Rockefeller gifts. In April 1914, Marie

Taylor Perkins, the secretary for the

fundraising drive and a private

secretary in the home of Rockefeller's personal

physician, appealed directly to Mrs.

Rockefeller for aid. She was told that

"Mr. and Mrs. Rockefeller had a

very unfortunate experience in connection

with contributions to this Home some

years ago, through Mrs. Belle Bolden,

who had been very highly recommended to

them."37

This news shocked the new leaders of the

Home for Aged Colored People,

raised the concerns of the Federation

for Charity and Philanthropy, and

prompted an investigation by

Rockefeller's advisors. Perkins

responded

promptly with a sense of outrage and

regret, taking pains to make clear that

the Home was under new management:

"We younger women who are taking

and have taken up the work have only the

deepest regret that those who have

gone before or particularly Mrs. Bolden,

has so conducted business that we

who are now working must lose

subscriptions or any particular subscription

thru dishonesty on the part of a former

President.... It is deplorable." Word

of the apparent scandal soon reached the

Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy, which asked the leaders of

the Home for a report. "This partic-

ular incident...is holding up donations

of which we are sorely in need,"

Perkins explained to Rockefeller, asking

for the help of his office in clearing

up the matter.38

The money in dispute proved to be a loan

from the Rockefellers to a former

officer of the Home, and did not involve

the operation of the Home for Aged

Colored People. Belle Bolden had been

president of the Home at the turn of

the century, but her relationship with

the Home was ended in 1903 "on ac-

count of discrepancies which were at

that time reported," according to Perkins.

Rockefeller's main Cleveland agent

during this period, Nathan Quilling, de-

scribed Bolden as "Cassie Chadwick

Number 2," referring to the celebrated

female con artist who posed as the

illegitimate daughter of Andrew Carnegie

and swindled local banks out of

thousands of dollars between 1897 and 1905.

Quilling's first assignment for

Rockefeller was to investigate a letter Bolden

had written "begging for money to

pay off some pressing debts." She had

36. Quilling to Rockefeller, January 29,

1914.

37. Harry D. Sims to Mrs. Marie T.

Perkins, April 9, 1914, in reply to her letter to Mrs.

Rockefeller, April 7, 1914.

38. Perkins to Sims, April 11, 1914, and

Perkins to Rockefeller, April 27, 1914.

Problems in Fundraising 161

been recommended to the Rockefellers by

Mrs. Martha Tuttle, Mrs.

Rockefeller's secretary. Bolden had established a relationship with

the

Rockefellers through her work with the

Home, and, according to Quilling,

"continued to write pitiful letters

to Mrs. Rockefeller." Since his

wife

"seemed to be anxious to help her,

Mr. Rockefeller finally decided to place

with the Superior Savings & Trust

Company $3500, the amount we believed

to be her total indebtedness, and this

money to be used to pay off mortgages

and debts in order that she might save

her home." Instead, she defaulted on

the monthly payments, according to

Quilling, and "we finally sold the

home."39

The confusion between the personal loan

to Bolden and the administration

of the Home was undoubtedly a costly one

for the Home; indeed, it may well

have cost it further financial support

from the Rockefellers, for there is no in-

dication that they contributed to the

Home in response to the appeals of 1913-

1914. It was just this concern about the

proper and efficient appropriation of

donated funds that the proponents of

organized charity sought to address, seek-

ing to assure donors that their money

would be used well and effectively. The

Home apparently never lost the trust of

the Federation for Charity and

Philanthropy and enjoyed its status as a

financial participant in the Welfare

Federation in subsequent decades,40

but it still had to expend energy and time

to overcome the burden of Belle Bolden's

administrative and personal financial

problems.

Thus, the cases of the Floating Bethel

Mission and the Home for Aged

Colored People illustrate two kinds of

concerns for donors and their organiza-

tions: first, that the work be

effective, efficient, and as useful as possible,

and secondly, that the administration of

the charity be trustworthy and ac-

countable. These cases also illustrate

the dynamic interplay between donors,

charitable institutions, and organized

philanthropic clearinghouses such as the

Cleveland Chamber's Committee on

Benevolent Associations and the

Federation for Charity and Philanthropy,

an interplay that necessitates histo-

ries of charitable organizing efforts

that examine the impact of these efforts

on the charitable institutions and

charity workers who were as much their tar-

gets as the poor and needy of the lower

classes.

39. Quilling to Harry D. Sims, May 21, 1914.

For a brief review of the life and career of

Cassie Chadwick, see the Encyclopedia

of Cleveland History (1987), 170.

40. Davis, Black Americans in

Cleveland, 193-94.

KENNETH W. ROSE

John D. Rockefeller's Philanthropy and

Problems in

Fundraising at Cleveland's

Floating Bethel Mission and the Home

for

Aged Colored People

In discussing attempts to organize

charity and philanthropy in the late nine-

teenth and early twentieth centuries,

historians have devoted much attention to

the institutions being organized-to the

charity organization societies, to phi-

lanthropic clearing houses, or to the

new foundations created by such wealthy,

public-spirited citizens as Andrew

Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Mrs.

Russell Sage-but have given little

concern to the impact such organizing

campaigns had on contemporary charity

work and existing social welfare in-

stitutions. Two institutions in

Cleveland which were affected by local efforts

to organize philanthropy were the

Floating Bethel Mission and the Home for

Aged Colored People. In the cases of

both of these institutions, records lo-

cated in the Rockefeller Family Archives

at the Rockefeller Archive Center in

Sleepy Hollow, New York, provide

valuable information about how these in-

stitutions fared around the turn of the

century. This material suggests some

of the problems associated with

fundraising at a time when donors were care-

ful to give only to worthy projects, and

when organizations were being estab-

lished to tell potential donors which

projects were, and which were not, meri-

torious.

As the wealthiest Clevelander with a widely

known reputation for giving,

John D. Rockefeller was a clear target

for organizations and individuals seek-

ing financial support for a wide array

of projects. From the time of his first

employment in a Cleveland mercantile

house in 1855, Rockefeller had been

making donations to needy individuals

and worthy charitable projects, giving

largely through his church.1 As

his income grew with his success in the oil

business, so too did the flow of his

charitable giving and his reputation as a

philanthropist. It was not unusual for Clevelanders to look

to the

Kenneth W. Rose has been the Assistant

to the Director of the Rockefeller Archive Center in

Sleepy Hollow, New York, since July

1987. He earned a Ph.D. in American Studies from Case

Western Reserve University in Cleveland,

where he also served as a senior editorial assistant

for the first edition of the

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (1987).

1. Rockefeller's first personal ledger,

"Ledger A," now preserved in the John D.

Rockefeller Papers at the Rockefeller

Archive Center, records his earliest charitable gifts.

(614) 297-2300