Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

SAMUEL J. TAMBURRO

Frances Jennings Casement and the

Equal

Rights Association

of Painesville, Ohio:

The Fight

for Women's Suffrage,

1883-1889

The history of the national struggle for

women's suffrage is well chroni-

cled.1 While the Seneca Falls

Convention in 1848 is generally accepted as

the starting point of the campaign for

women's voting rights, women's civil

and political rights advanced slowly.

Although several states granted women

the right to vote in municipal and school

elections, only the Territory of

Wyoming, in 1869, granted full political

equality prior to 1890. Colorado,

Utah, and Idaho enfranchised women in

the 1890s, but few other states per-

mitted women's suffrage in state

elections before 1910.2

This slow pace of change did not reflect

a lack of organization. The suf-

fragists organized grassroots movements

in extremely imaginative ways, of-

ten attempting to link their cause with

those of other movements.3 At times,

women involved in the abolition and

temperance movements also became in-

Sam Tamburro is a historian with the

National Park Service and works in the Cuyahoga

Valley National Recreation Area. He

wishes to thank the staff at the Lake County Historical

Society for its assistance in locating

research materials and Dr. Carol Lasser of Oberlin

College for her thoughtful and observant

comments on the article.

1. The campaign for women's suffrage is

amply described in Eleanor Flexner, Century of

Struggle: The Women's Rights Movement

in the United States (Cambridge,

Mass., 1959);

Aileen S. Kraditor, The Ideas of the

Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890-1920 (New York,

1965); William O'Neill, Everyone was

Brave: The Rise and Fall of Feminism in America

(Chicago, 1969) and Feminism in

America: A History (New Brunswick, N.J., 1989); Janet

Zollinger Giele, Two Paths to Women's

Equality: Temperance, Suffrage, and the Origins of

Modern Feminism (New York, 1995); The Concise History of Woman

Suffrage, Mari Jo and

Paul Buhle, eds. (Chicago, 1978); and

Ellen Carol DuBois, Feminism and Suffrage: The

Emergence of an Independent Women's

Suffrage Movement in America, 1848-1869 (Ithaca,

N.Y., 1978); and Elizabeth Cady Stanton,

Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, et al.,

History of Woman Suffrage, vols. 1-6 (Rochester, N.Y., 1881-1902).

2. For a detailed description of the

progression of the women's suffrage cause after the

Civil War, see Flexner, Century of

Struggle and DuBois, Feminism and Suffrage.

3. According to DuBois in Feminism

and Suffrage, Stanton and Anthony attempted to estab-

lish women's suffrage as an independent

political movement by linking it with the emerging or-

ganized labor movement. The result was

the formation of the Working Women's Association

(WWA), a female wing of the National

Labor Union (NLU).

Frances Jennings Casement

163

volved in the push for voting

rights. Suffragist leaders such as

Susan B.

Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and

later Carrie Chapman Catt recruited

support from various organizations. It

was this degree of organizational effort

and support that eventually created the

political pressure to ratify the

Nineteenth Amendment, ensuring women's

voting rights in 1920.4 Local

leaders also significantly aided in the

early organization of the women's

movement especially in Ohio. One of

these local leaders was Painesville's

Frances Jennings Casement.5

Page through any study of the women's

suffrage movement and there is

scarcely a mention of Frances Jennings

Casement even though she was cen-

tral to the Ohio movement. Casement served as president of the

Ohio

Woman Suffrage Association (OWSA) from

1885 to 1888 and was a leading

activist for women's rights. Under her

influence, Warren, Ohio's, Harriet

Taylor Upton, the treasurer and one of

the founders of the National American

Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA),

became interested in the suffrage

movement. Upton wrote, "She

[Casement] bombarded me with letters and

pamphlets and helped me see the light

about the need for woman's suffrage."6

Casement also worked closely with

national women's rights leaders such as

Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and

Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Her work con-

centrated mainly in the formative period

of the Ohio women's suffrage

movement (1870 to 1888) and centered on

organizing the Equal Rights

Association (ERA) of Painesville (1883

to 1885).7

4. Giele, Two Paths, 1-15; The

relationship between women's suffrage and the abolition and

temperance movement in Ohio is explored

in Jack S. Blocker Jr., "Give to the Wind thy

Fears": The Women's Temperance

Crusade, 1873-1874 (Westport, Conn.,

1985), 163-76;

Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers

Shuler, Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story

of the Suffrage Movement (New York, 1926), 196-210; Charles B. Galbreath, History

of Ohio,

vol. 2 (New York, 1925), 153-351; Philip

D. Jordan, Ohio Comes of Age, 1873-1900

(Columbus, Ohio, 1968); and Eugene H.

Roseboom and Francis P. Weisenburger, A History of

Ohio (Columbus, Ohio, 1976).

5. To avoid confusion, Frances Jennings

Casement is referred to as Casement, Jack

Casement as Jack, and C.C. Jennings as

Jennings. Other local suffragists leaders in Ohio who

were active during the Reconstruction

era include Rosa L. Segur of Toledo and Elizabeth Coit

and Rebecca Janney of Columbus.

6. Virginia Clark Abbott, The History

of Woman Suffrage and the League of Women Voters

in Cuyahoga County, 1911-1945 (Cleveland, Ohio, 1945), 10-11. Ohio became central to

the

national suffrage movement, and from

1903-1909 the NAWSA headquarters was located in

Warren, Ohio, while Upton functioned as

treasurer and executive director of the organization.

In addition to her activities in NAWSA,

Upton served as president of the OWSA for 18 years

(1899-1903 and 1911-1920). Upton, in her

autobiography Random Recollections, Chapter

XIV, 4, credits Casement with

reorganizing the Ohio woman's suffrage movement. For fur-

ther bibliographic information regarding

Harriet Taylor Upton, see Phillip R. Shriver's descrip-

tion in Notable American Women,

1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, Edward T. James,

ed. vol. 3 (Cambridge, Mass., 1971),

501-02.

7. Prior to the Civil War, the women's

suffrage movement in Ohio remained closely linked

with the Abolition movement. During

Reconstruction, women began to realize that the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments

would apply only to African-American males and thus

established their own suffrage advocacy

organizations. The Ohio Woman Suffrage

164 OHIO

HISTORY

The formation and early history of

Painesville's Equal Rights Association

is worth close attention, as is Frances

Casement's role therein. Casement is

important because she represents the

type of suffrage leadership that emerged

from a local context and expanded to

influence the movement at the state and

national levels. Casement's ability to

organize and manage the ERA cannot

be understood without reviewing the

formative period of her life. Strong be-

liefs in temperance, abolition, and

religion affected her zeal for reform move-

ments. Moreover, supportive men in her

life enhanced Casement's leadership

qualities. Her father, C. C. Jennings,

and her husband, John S. (Jack)

Casement, encouraged her conviction in

causes such as abolition and wom-

en's rights, causes in which both men

actively participated. They became

prominent figures in the Painesville

community and received a high level of

respect. Their support of the ERA

afforded it a sense of respectability.

II

Frances Jennings Casement, born on 23

April 1840 to Charles C. and

Mehitabel Park Jennings, spent her

childhood on the "Jennings Place," a 400-

acre farm overlooking the Grand River in

Painesville, a small agricultural

community thirty miles east of

Cleveland.8 Being from one of the founding

families in the Western Reserve,

Casement did not experience a typical pio-

neer farm upbringing. The only child of

successful agriculturists who owned

an extensive apple orchard and nursery,

Casement rarely found herself toiling

on the family farm. In an

autobiographical sketch of her childhood, she re-

counted days spent in a playhouse,

complete with a set of fine china, built on

Association formed in 1869. This

formative period, 1870 to 1910, has been labeled the

"doldrum" years by historians

studying the period because efforts for women suffrage had few

successes during this time. For an

example see Olivia Coolidge, Women's Rights: The Suffrage

Movement in America, 1848-1920 (New York, 1966), 84-87.

For historical accounts of the women's

suffrage movement in Ohio that touch on the period

of Casement's activism, see Eileen

Regina Rausch, "Let the Women Vote: The Years to

Victory, 1900-1920," (Ph.D. diss.,

University of Notre Dame, 1984); Florence E. Allen and

Mary Wells, The Ohio Woman Suffrage

Movement: A Certain and Unalienable Right

(Columbus, Ohio, 1952); Harriet Taylor

Upton, Random Recollections of Harriet Taylor Upton

(Columbus, Ohio, 1927); Harriet Taylor

Upton, "The Woman Suffrage Movement in Ohio," in

Charles B. Galbreath, History of Ohio

vol. 2 (New York, 1925), 329-39; James R. Henry, "The

Woman Suffrage Movement in Dayton and

Montgomery County, 1912 to 1919," (M.A. thesis,

Miami University, 1977); Kevin Martin

Gerrard Kuethe, "The Courage of their Convictions:

The Woman's Suffrage Movement in

Cincinnati from 1912 to 1920," (M.A. thesis, Miami

University, 1995); Ralph Henry Mikesell,

"The Woman Suffrage Movement in Ohio 1910-

1920," (M.A. thesis, Ohio State

University, 1934); Mary Majorie Stanton, "The Woman

Suffrage Movement Prior to 1910,"

(M.A. thesis, Ohio State University, 1947); and Sabiha

Naz, "Woman Suffrage in Wood

County, Ohio: 1910-1920," (M.A. thesis, Bowling Green

State University, 1980).

8. Painesville was founded in 1797. By

the 1870s, its population consisted mainly of second

and third generation WASPs whose

families migrated from New England after the American

Revolution.

Frances Jennings Casement 165

the family property. The everyday chores

of farm children of this period es-

caped Casement. The Jennings's family

wealth also allowed her to receive

formal schooling, which was a rarity

during this time. Although Ohio had

11,661 public schools in 1850, only

approximately one out of four Ohioans

attended classes. This elite 25 percent

included Casement. She attended

Painesville District School in 1847 and

excelled in curriculum courses, espe-

cially reading. Casement graduated from

the Painesville Academy in 1852

and the Willoughby Female Seminary four

years later. Her parents were sup-

portive of her educational career and

stressed the importance of literacy and

speaking skills; the latter would serve

her well in her future role as a wom-

en's rights activist. Casement, however,

believed that the most useful educa-

tion was provided by her father's

personal and political activities. She devel-

oped her sense of social responsibility

from her father's beliefs. He supported

abolition and women's suffrage long

before they became generally accepted

ideologies.9

To claim that Charles C. Jennings served

as a strong role model would be

an understatement; he was truly a

dynamic and innovative man. In 1825, he

became a teacher in the Painesville

Public School system and a strong advo-

cate of free education. Even after he

established himself as a fruit grower and

horticulturist, Jennings acted as the

director of the school district.

Furthermore, he organized and led the

Painesville agricultural community.

Jennings founded the Patrons of

Husbandry, or the Grange, in 1870 and even-

tually was elected the executive master

of the organization. Moreover,

Jennings emerged as an influential

member of the Painesville religious com-

munity. Serving as president of the

Building Committee at the Methodist

Episcopal Church of Painesville, he

oversaw the construction of the new

church in 1868.10

Probably the most impressive part of

Jennings's resume centered on his po-

litical activities. From 1854 to 1856,

Jennings served his district in the Ohio

House of Representatives. He began his political

career as a Whig but even-

tually converted to the Republican

Party. An outspoken critic of the expan-

sion of slavery, he publicly called for

abolition on the House floor in 1854.

Jennings had become involved in the

abolition movement in the 1830s, and

9. Little historical information exists

regarding Mehitabel Parks Jennings (1815-1870). She

married C.C. Jennings in 1837 and

Frances was their only child. Jennings had been married

previously to Roxana Graham (1809-1833)

and had one child, Clymena (1833-1885). Graham

died three weeks after her daughter's

birth and Clymena was raised by Jennings's parents,

Oliver and Jerusha Jennings. Frances and

her stepsister remained close friends until Clymena's

death in 1870. Frances Jennings Casement

Papers, MSS 510, Box 2, Folder 2, Ohio Historical

Society, Columbus, Ohio, cited hereafter

as Casement Papers, OHS; Dan Dillon Casement, "A

Pioneer Childhood: Frances Jennings

Casement," The Bicentennial Edition Lake County History

(Mentor, Ohio, 1976), 257-60; George W.

Knepper, Ohio and Its People (Kent, Ohio, 1989),

189; Painesville Telegraph, 16

March 1876.

10. William Brothers, The History of

Lake and Geauga Counties (Cleveland, Ohio, 1876), 43;

Painesville Telegraph, 16 March 1876.

166 OHIO HISTORY

the ideology of William Lloyd Garrison,

leader of the American abolitionists,

influenced him greatly. This equal

rights ideology espoused by her father had

a lasting effect on Casement. Like most

early suffragists, her beliefs in polit-

ical equality for women formed from the

abolition movement.

Jennings ardently supported the first

Republican presidential candidate, John

C. Fremont, in the 1856 election. Four

years later, he backed Abraham

Lincoln and the cause to contain

slavery. In his political activity after the

Civil War, Jennings focused on the

grassroots populism of the Grange, be-

lieving that the Grange should not be

identified with any political party but

should serve as a check on dishonest

politicians. Jennings died before the

People's Party rose to prominence, but

he supported the movement in its

formative stages. It is reasonable to

conclude that Jennings's belief in social

equality helped to shape his daughter's

ideas on social causes.

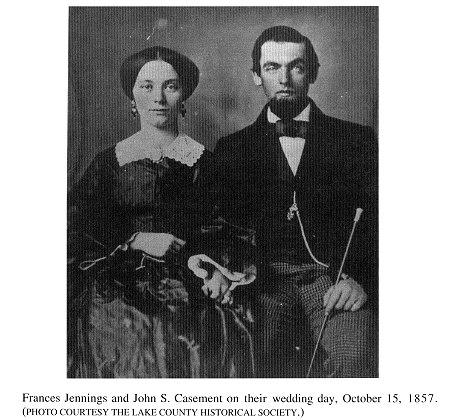

On 15 October 1857, Frances Jennings

married John S. Casement (1829-

1909), the other dominant influence in

her life. Born in Ontario County,

New York, "Jack" Casement

moved to a farm in Ann Arbor, Michigan, at age

fifteen, where he began working as one

of the many laborers constructing the

Michigan Central Railroad. In 1850, his

work brought him to Ohio to help

build the Cleveland, Columbus &

Cincinnati Railroad. By 1856, Jack be-

came a foreman and returned to Cleveland

to supervise a track-laying gang for

the Cleveland, Painesville &

Ashtabula Railroad (CP&A). The CP&A track

was laid near the "Jennings

Place," which enabled Casement and Jack to meet

in 1857 and marry three months later. 11

After marriage, Jack continued building

railroads. He later filled ravines and

laid track for the Grand Trunk and the

Erie & Pittsburgh. At the start of the

Civil War, Jack's abolitionist

convictions compelled him to join the Union

cause. He volunteered, was elected major

of the Seventh Ohio Volunteer

Infantry, and served in the Virginia

theater of the war where he saw combat at

Cross Lanes and Winchester; he also led

numerous attacks in Tennessee

against Mosby's guerrillas. Jack would

later be breveted to brigadier general

and assist in Sherman's "march to

the sea." More importantly, during

Sherman's campaign, Jack met General

Grenville Dodge who would later be-

come the chief engineer for the Union

Pacific Railroad. In 1866, Dodge con-

tacted Jack and informed him that the

U.S. Congress was anxious to complete

the transcontinental railroad. Jack,

with the help of his brother Daniel, en-

tered into a contract to complete the

Union Pacific Railroad. The Casement

brothers were responsible for laying

1,044 miles of track between Omaha,

Nebraska, and Promontory, Utah, and

participated in the ceremonial driving of

the "golden spike" upon the

completion of the link in May 1869.

11. Jack Daniels, "Railroads Big

Part of Casement's Life." Painesville Telegraph, 18

January 1986; Jessie Rayduk, "The

Truth about General Casement," Painesville Telegraph, 3

February 1958.

|

Frances Jennings Casement 167 |

|

|

|

Jack also became involved in the politics of the West. During his stay in the Wyoming Territory, the citizens elected him as their non-voting represen- tative to the U.S. Congress for the 1868 to 1869 term. Jack, a Republican, went to Washington, D.C., to lobby for Wyoming statehood and the exten- sion of equal voting rights to women; Wyoming granted women's suffrage in 1869.12 As a territorial representative, Jack met and worked closely with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton for women's rights in Wyoming. Casement, who had made several trips West to visit her husband, also became involved in the feminist cause in Wyoming and befriended both Stanton and Anthony. She brought feminist ideals back to Painesville in 1870. Even though neither Jack nor Jennings was directly responsible for Casement's activism in the feminist cause, they clearly supported her beliefs and actions. Thirteen years would pass before Casement attempted to organize the Equal

12. T.A. Larson, History of Wyoming (Lincoln, Nebraska, 1965), 67. |

168 OHIO HISTORY

Rights Association in 1883. The 1870s

proved to be a period of disunity

within the national women's suffrage

cause, and it is useful to review quickly

the issues that created the split.13

III

Two rival groups within the national

women's suffrage movement pursued

opposing policies in the years after the

Civil War. The National Woman

Suffrage Association (NWSA), founded by

Stanton and Anthony in 1869, ag-

itated for a federal constitutional

amendment that would give women the right

to vote. The NWSA promoted a broad

spectrum of women's rights such as

equal suffrage, equal pay, more liberal

divorce laws, and birth control to pro-

mote "self-sovereignty."

Furthermore, NWSA members denounced the

Fifteenth Amendment, which enfranchised

only African-American males, and

eventually decided to exclude men from

their organization.

The American Woman Suffrage Association

(AWSA), organized in 1869

by Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe, went

in another direction. The AWSA

recommended that women not seek federal

action until the campaign for black

suffrage succeeded. This association,

which included males within its ranks,

published the Woman's Journal and

waged state referendum campaigns for

women's suffrage. But after black male

suffrage was achieved with the ratifi-

cation of the Fifteenth Amendment in

1870, it became clear that the

Republican Party would not take up the

fight for women's suffrage as the

AWSA had hoped. Residual bitterness

between the two women's suffrage

groups kept them apart for another

twenty years, although the division over

the Fifteenth Amendment no longer

applied. The effective leadership of both

wings soon passed to younger, more

moderate women who realized reunifica-

tion was necessary to obtain women's

suffrage. In 1890, the two organiza-

tions merged to become the National

American Woman Suffrage Association

under the leadership of Susan B. Anthony

and later Carrie Chapman Catt.

Casement had seen the need for unity

seven years earlier when she founded the

ERA of Painesville.14

By 1883, the American Equal Rights

Association (AERA), founded in

1868, had been dismantled for nearly

fifteen years. Historian Janet Zollinger

Giele contends that the AERA, founded by

Susan B. Anthony, worked in uni-

son with the National Labor Union to

stress the need for women's suffrage.

Both the NWSA and the AWSA had grown out

of the AERA, which immedi-

13. Daniels, "Railroads," Painesville

Telegraph, 18 January 1986; Rayduk, "The Truth about

General Casement," Painesville

Telegraph, 3 February 1958; Ida Husted Harper, The Life and

Work of Susan B. Anthony, vol. 1 (Indianapolis, Ind., 1898), 432: Maury Klein, Union

Pacific:

Birth of a Railroad, 1862-1893 (New York, 1987), 63; Larson, History of Wyoming, 67.

14. Giele, Two Paths, 114-16;

O'Neill, Everyone Was Brave, 18-21; Kraditor, Ideas of the

Woman Suffrage Movement, 4-8.

Frances Jennings Casement

169

ately after the Civil War sought the

enfranchisement of both women and for-

mer slaves. The AERA disbanded after the

split within the women's suffrage

movement occurred.

Casement's ERA of Painesville differed

from other local suffrage organiza-

tions in Ohio in that it did not attempt

to avoid association with the national

suffrage groups. Casement reached out to

both the NWSA and AWSA, bor-

rowing ideas and techniques from each to

shape her group into an effective

suffrage association.

Additionally, she utilized

the ERA to

educate

Painesville's women about suffrage and

other women's issues. Her leadership

qualities gained her respect within the

national women's organizations, and

she may have influenced the 1890

suffrage "reunification."15

Early women's rights advocates can be

categorized into various groups that

illustrate their commitment to the

cause. Historian William L. O'Neill di-

vides early suffragists into two

categories: social feminists and "hard core" or

"extreme" feminists whom he

calls equalitarians. Social feminists wanted

equal rights for women but not at the

expense of other causes such as temper-

ance, while equalitarians were politically

radical reformers willing to place

women's individual rights before all

other causes. As an individual, Frances

Casement can be categorized as an

equalitarian, but she founded her ERA on a

social feminist ideology because of the

strong existence of the women's tem-

perance movement in Painesville.

Casement specifically designed the ERA

to develop a social network of women

committed to societal reform and edu-

cation, and her plan for widespread

appeal succeeded.16

IV

Unlike twentieth century women's suffrage

organizations, which normally

consisted primarily of middle-class

members, the Painesville ERA was com-

posed mostly of wealthy, upper-class

women.17 The group of twenty-one

15. Giele, Two Paths, 50; Rausch,

"Let Ohio Women Vote," 24-25; Carol Lasser, "Party,

Propriety, Politics, and Woman Suffrage

in the 1870s: National Developments and Ohio

Perspectives" New Viewpoints in

Women's History: Working Papers from the Schlesinger

Library 50th Anniversary Conference,

March 4-5, 1994 (Cambridge, Mass.,

1994), 153.

According to Lasser, Ohio's

Reconstruction era suffragists tended to avoid the partisanship that

came to characterize the rivalry between

the two major suffrage organizations in the country.

By 1870, Ohio had thirty-one suffrage

societies. Suffrage groups in Toledo, South Newbury,

Dayton, and the Western Reserve remained

disaffiliated from both the NWSA and the AWSA.

The fight for woman's suffrage was

viewed as a local issue. For the founding of other local

suffrage groups in Ohio, see Elizabeth

Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage,

et al, eds., History of Woman

Suffrage, vol. 3 (Rochester, N.Y., 1881-1902), 491-509, cited

hereafter as HWS.

16. O'Neill, Feminism in America, 18-21.

17. DuBois argues, in Feminism and

Suffrage, 160-61, that the NWSA's effort to reach

working-class women alerted the

suffragists to an entirely different constituency-the middle

class. Prior to 1890, the ranks of the

women's suffrage movement were filled with mostly

170 OHIO

HISTORY

charter members elected Casement as

president and met weekly at a member's

residence. Casement clearly defined the

objectives of the ERA. She believed

that the ERA would serve as a discussion

forum for the community's

"progressive" women, and that

the discussion of important social questions

would serve as a form of education. Influenced by her experiences in

Wyoming, Casement firmly believed that

the time would eventually come

when men and women would have equal

voices in the nation's government.

In her ERA diary, Casement wrote:

...there is a real need for a society in

which women could come together and talk of

the questions of the day and inform themselves

upon those questions and do what

they might for the education of

themselves and their sisters.... the time will soon

come when men and women will stand as

equals and have an equal voice in the

government of our nation.18

The group chose the ERA's name because

it expressed their goals without

alienating people who did not agree with

the women's suffrage cause.

Casement realized that some of the most

skilled and articulate anti-women's

suffrage leaders in Painesville were women.

For this reason, the ERA ex-

tended membership to women and men who

disagreed with equal suffrage.

Casement believed that effectively

refuting critics quickly gained converts to

the cause.

Furthermore, women from the Woman's

Christian Temperance Union

(WCTU) joined the ERA, such as Mary

Hickson, the president of the

Painesville WCTU, an outspoken critic of

women's suffrage and a founding

member of the ERA. Because of her

husband's drinking, Casement also be-

lieved strongly in temperance. During

his time away from Casement, Jack

had a tendency to find solace in

alcohol. Casement implored him to resist the

habit and went as far as to make him

swear a vow of temperance while in

Wyoming, a vow he did not keep.

Nevertheless, Casement never joined the

WCTU, and the topic rarely arose at

weekly meetings even though the tem-

perance cause was well represented

within the ERA.19

The discussions, which often developed

into debates, at the ERA sessions

centered mainly on the women's suffrage

cause. How Casement raised the is-

sue is fascinating and nothing short of

subterfuge. The ERA would headline

wealthy elite members. Painesville's ERA

was indicative of this trend. Out of the twenty-one

original members, nineteen could trace

their family's ancestry back to the founding of the

community. Two of the women were not

married, but most were married to prominent men in

Painesville. All lived within a mile

radius of Painesville's town square, and eleven lived in a

neighborhood once known as

"millionaires row," which was indicative of the wealthy families

that resided there.

18. ERA Diary, Casement Papers, Box 1,

Folder 60, OHS.

19. ERA Diary, Casement Papers, Box 1,

Folder 60, OHS; Klein, Union Pacific, 68; Frances

Jennings Casement to John S. Casement,

Frances Jennings Casement Papers, Box 1, Folder 2,

Lake County Historical Society, Mentor,

Ohio, cited hereafter as FJC Papers, LCHS.

|

Frances Jennings Casement 171 |

|

|

|

a feature speaker at each gathering, called a "parlor talk," and advertise each meeting on the society page of the Painesville Telegraph, which drew wom- en's interest to the discussion topic. The talk itself usually consisted of a lec- ture about something such as one's exotic vacation to Europe or Asia. For example, Louise Randolph, a member of the ERA, delivered eight lectures about "Rome, the ancient city." Although Casement considered such lectures "deadly dull," they remained popular among community women and an effec- tive way to attract new members. (The ERA's membership doubled within a matter of two months.) After the parlor talks, new members were introduced to the concepts of women's suffrage. Casement directed the topic of discus- sion toward equal voting rights by posing a question or reading a provocative article from the Woman's Journal concerning the subject. Often this tactic created disagreements and arguments, but it recruited new members who could be mobilized for the suffrage cause.20 The ERA first attempted to become active in a women's cause at Adelbert College, which would later become part of Case Western Reserve University. In 1880, Amasa Stone founded Adelbert College as a coeducational institu-

20. ERA Diary, Casement Papers, Box 1, Folder 59, Folder 60, OHS. |

172 OHIO HISTORY

tion. In March 1884, however, the

school's Board of Trustees proposed ex-

cluding women from admission.

Responding, the ERA spent two weeks cir-

culating petitions among citizens and

sending letters of protest to the Adelbert

College trustees; within a week, the ERA

helped to collect 1,000 signatures.

As a result of such pressure, the

trustees decided to retain co-education. More

importantly, for the sake of its cause,

the ERA developed a close relationship

with the Western Reserve Club (WRC) of

Cleveland, a women's suffrage

organization. The ERA and WRC would

continue to work together on

women's rights issues and hold joint

informational meetings. The ERA

doubled its mobilizing resources by

cooperating with the WRC and, with its

newly found strength, moved slowly

toward the equalitarian model of radical-

ism.21

On 26 April 1884, the ERA and the WRC

held a joint meeting to discuss

women's issues; fifteen members of the

ERA, including Jack, attended the

meeting. Casement delivered a paper endorsing the enfranchisement of

women, as well as equal opportunities

for them in education and labor. Her

well-received paper spurred a spirited

debate between anti- and pro-suffrage

members at the conference. No longer

viewed as simply a women's social

club, the Painesville ERA openly became

a leading advocate of equal voting

rights. Significantly, the ERA's stance

at the joint conference thrust it into a

position of importance in the Ohio state

suffrage movement.22

From November 1883 to May 1884, the ERA

tripled in membership and

formed two new branches in the

surrounding towns of Mentor and Kirtland.

Casement intended to establish ERA

chapters in every Lake County township

and called for all members to become

active recruiters. She also organized

several rallies at the Lake County

Courthouse to call attention to the need for

equality between the sexes; in one

especially pointed courthouse speech,

Casement called on the Ohio General

Assembly to allow women the right to

control their earnings or dowry and to

retain guardianship of their children in

the case of divorce. Her speech, which

met with a hostile reaction from a

segment of men in the audience, brought

attention to the real problem of do-

mestic inequality, including fair

treatment for divorced women.23

The ERA's rallies and Casement's

speeches drew an invitation to attend the

Ohio Woman Suffrage Association's (OWSA)

First Annual Convention.

Although the OWSA had existed since

1869, it remained largely unorganized

and did not hold a formal convention

until 1884. On 19 June 1884, the ERA

21. ERA Diary, Casement Papers, Box 1, Folder

60, OHS; HWS, vol.3, 499; C.H. Cramer,

Case Western Reserve: A History of

the University, 1826-1976 (Boston,

1976), 90-93; David D.

Van Tassel and John J. Grabowski, eds., The

Encyclopedia of Cleveland History (Bloomington,

Ind., 1987), 158-59.

22. Frances Jennings Casement's Speech

to the Western Reserve Club 26 April 1884, FJC

Papers, Box 1, Folder 3, LCHS; Farmers's

Institute Speech, Casement Papers, Box 1, Folder 58,

OHS; Cleveland Plain Dealer, 28

April 1884.

23. Painesville Telegraph, 27 April

1884.

Frances Jennings Casement 173

sent to the convention a delegation of

five women, which did not include

Casement. (She remained in Painesville

consoling a friend whose daughter

had suddenly died.) The Painesville

group found the state gathering small,

disorganized, and "laughable"

in its level of discussion. Nevertheless, the

ERA's party voted on amendments to the

OWSA Constitution and assisted in

electing as its new president U.S.

Congressman Ezra P. Taylor, Harriet

Taylor Upton's father. The conference

also elected the absent Casement as

OWSA's vice president. Shortly after the

conference, Taylor resigned from

the OWSA presidency, believing that his

responsibilities in Washington,

D.C., would limit his effectiveness in

the OWSA cause, and Casement be-

came de facto president of the suffrage

organization. The following year,

Casement would be elected the president

of the OWSA in her own right. At

this time, Casement's ERA began to gain

recognition in the national suffrage

arena as well.24

From the early formation of the ERA,

Frances Casement had reached out to

the AWSA. In return, Lucy Stone's AWSA

provided Casement with free

copies of the Woman's Journal and

additional pamphlets concerning women's

issues. Stone also aided in the drafting

of the ERA's Constitution and the

organizing of its governing structure.

Being impressed by the ERA's organi-

zation and leadership, Stone invited

Casement to speak at the Sixteenth

Annual AWSA Convention in Chicago on 20

November 1884. Casement's

speech centered around the state of the

women's suffrage movement in Ohio.

By making the speech, Casement became

one of the foremost spokespersons

of the Buckeye State's cause in 1884,

but her address also made a strong

statement regarding the larger movement.

She stated that the national crusade

needed to set aside its petty

differences between the AWSA and NWSA and

unite in action for the movement to be

successful; Casement's call for unity

came six years prior to the actual

reunification of the two associations. Her

statement characterized the mood of

numerous local suffrage organizations.

The fact that she remained friends with

both Lucy Stone and Susan B.

Anthony gave her declaration further

legitimacy. Casement realized that only

minor differences separated the AWSA and

the NWSA.25

24. Rausch, "Let Ohio Women

Vote," 23-26; Allen and Welles, The Ohio Woman Suffrage

Movement, 34-35; Harriet Taylor Upton, "The Womans Suffrage

Movement in Ohio" in

Charles B. Galbreath, History of

Ohio, vol. 2 (New York, 1925), 329-31; HWS, vol. 3, 502-09;

Courthouse Speech, FJC Papers, Box 1,

Folder 3, LCHS; Painesville Telegraph, 27 April 1884;

ERA Diary, Casement Papers, Box 1,

Folder 60, OHS. From 1885 to 1920 the OWSA had six

presidents: Frances Jennings Casement,

Painesville, 1885-1888; Martha H. Elwell, Willoughby,

1888-1891; Caroline M. Everhart,

Massillon, 1891-1898; Harriet B. Stanton, Cincinnati, 1898-

1899; Harriet Taylor Upton, Warren,

1899-1908 and 1911-1920; Pauline Steinem, Toledo,

1908-1911. The OWSA president was

elected during annual conferences usually in

northeastern Ohio towns.

25. In the mid-1880s the only minor

personal differences existed between the AWSA and

the NWSA leadership. By 1887, Lucy Stone

was ready to reconcile her personal disagree-

ments with Susan B. Anthony. For a

further description of the reunification issues see Friends

174 OHIO HISTORY

One week after the AWSA address, Susan

B. Anthony lectured in

Painesville at the behest of the ERA. An

audience of approximately 1,000

filled the Painesville Methodist Church

to capacity. A twenty-five cents ad-

mission charge raised nearly $300 for

the ERA's coffers. Anthony spoke as a

representative of NWSA, and her address

focused on the subject of equal rights

for women in politics, in the workplace,

and in the home. She emphasized

unity between the international and

national women's movements. In fact,

her message echoed Casement's speech at

the AWSA conference in calling for

a united women's front as the only way

to achieve the goal of suffrage. What

effect Casement's views on the reunion

of the associations had on Anthony's

speech is unknown, although we do know

that Anthony spent two days at the

Casement home prior to her talk.

Regardless of its inspiration, Anthony's

lecture highlighted the ERA's first

year.26

The first anniversary meeting of the ERA

had plenty to celebrate. In one

year, the association grew from

twenty-one to 131 members and branched out

into the surrounding communities of

Kirtland, Mentor, and Chardon.

Moreover, the level of the association's

discussions evolved from parlor talks

to petitioning the state General

Assembly to change property and inheritance

laws regarding women. Meetings moved

from leading members' residences to

the county courthouse and the

Painesville City Hall. The ERA's ability to

mobilize for women's causes became

evident. The ERA's anniversary cele-

bration echoed these themes of change.

Attending the meeting were members

of the NWSA and AWSA, in addition to the

WRC and OWSA. Casement

served as the mistress of ceremonies and

again emphasized the message of to-

getherness among women's organizations.

She stated:

The organization represented here today

differs in name alone, our outlook for the

future aim is toward the same object....

Let us work with renewed energy to in-

crease our numbers and more thoroughly

organize throughout the state and the na-

tion. We have only to look at our

sisters of the WCTU to see how thorough orga-

nization educates. There is much to be

done, but with the advice and counsel of

those who have had more experience, let

us do our part to help, knowing that be-

fore long right will prevail.7

The speech offered more, including the

need to amend the nation's laws that

had been written exclusively by men and

failed to consider women and chil-

dren. Additionally, Casement called for

social as well as voting equality.

and Sisters: Letters between Lucy

Stone and Antoinette Brown Blackwell, 1846-93, Carol Lasser

and Marlene Deahl Merrill, eds. (Urbana,

Ill., 1987), 227-36; ERA Diary, Casement Papers,

Box 1, Folder 60, OHS; Lucy Stone to

Frances Jennings Casement, transcript in the hand of

Stone, 10 October 1884, FJC Papers, Box

1, Folder 4, LCHS; Frances Jennings Casement's

Address to the AWSA, 20 November 1884,

FJC Papers, Box 1, Folder 4, LCHS.

26. ERA Diary, Casement Papers, Box 1,

Folder 60, OHS; Painesville Telegraph, 28

November 1884; Harper, Susan B.

Anthony, vol. 1,380.

27. Painesville Telegraph, 12

December 1884.

Frances Jennings Casement 175

She firmly believed that woman's

position in society would change only

through the acquisition of suffrage

rights.

Casement also persuaded her husband to

speak at the anniversary meeting.

His address echoed her message of

equality for women and called on the like-

minded men of Painesville to support the

cause of women's suffrage actively.

Utilizing her husband's talents

represented an astute maneuver on Casement's

part, as presenting a local,

well-respected man who backed the suffrage issue

resonated within the males in the

audience. Casement intended for her hus-

band to serve as a role model for the

community's men.28

The successes of the ERA created

increased publicity for Casement. Her

leadership abilities displayed in the

ERA and her progressive vision for the fu-

ture of the women's movement would

propel her to the presidency of the

Ohio Woman Suffrage Association in 1885,

a position from which she would

serve as a vocal advocate until 1888

when she resigned her office. Why

Casement resigned after only three years

of service is a mystery. But an edu-

cated guess would point to her extreme

fear of public speaking; she often be-

lieved herself to be an ineffectual

speaker and loathed the responsibility of lec-

turing. Being the president of the OWSA

presumably increased her public

speaking engagements, and thus it is

possible that her phobia may have in-

fluenced her decision to resign in 1888.

But it was more likely that a per-

sonal tragedy led to her resignation.

Her son, John Frank Casement, died on

11 March 1886 of typhoid fever at the

age of nineteen (of her three sons, only

one survived to adulthood, Dan Dillon

Casement), a tragedy which perhaps

helped sap her willingness to serve.29

In 1920, the National American Woman

Suffrage Association (NAWSA)

honored Frances Jennings Casement as a

pioneer in the movement, one who

served as a leader in the movement

before 1880. She displayed remarkable

foresight in her continual call for a

unified national front in the suffrage

cause. Ironically, when the NAWSA formed

in 1890, Casement was living

with her husband in Costa Rica where he

served as chief engineer on the San

Jose-Pacific Railroad construction

project. They remained in Costa Rica until

1903. Although she was not directly

involved with the creation of the na-

tional organization, it is certainly

likely that her efforts in the ERA and

OWSA helped lead to its birth.30

Casement died on 24 August 1928 at the

age of eighty-nine. She remained

active in women's causes relating to

education and labor until her death. She

never strayed from her social justice

ideals or her belief that solid organization

was the strongest asset to the women's

suffrage movement, and she fought to

28. ERA Diary, Casement Papers, Box 1,

Folder 60, OHS; Painesville Telegraph, 12

December 1884.

29. Painesville Telegraph, 18

March 1887.

30. Carrie Chapman Catt to Frances

Jennings Casement, 15 March 1920, typescript, FJC

Papers, Box 1, Folder 4, LCHS.

176 OHIO HISTORY

change state and national laws that were

discriminatory toward women. She

had realistic goals and pragmatic,

effective means of achieving them. In her

diary, Casement wrote, "To change

society, you must change government,

and voting is the only way." The

fate of the women's suffrage movement of-

fers testimony to her ideals and her

means of achieving them.31

31. Casement Papers, Box 2, Folder 3,

OHS.

SAMUEL J. TAMBURRO

Frances Jennings Casement and the

Equal

Rights Association

of Painesville, Ohio:

The Fight

for Women's Suffrage,

1883-1889

The history of the national struggle for

women's suffrage is well chroni-

cled.1 While the Seneca Falls

Convention in 1848 is generally accepted as

the starting point of the campaign for

women's voting rights, women's civil

and political rights advanced slowly.

Although several states granted women

the right to vote in municipal and school

elections, only the Territory of

Wyoming, in 1869, granted full political

equality prior to 1890. Colorado,

Utah, and Idaho enfranchised women in

the 1890s, but few other states per-

mitted women's suffrage in state

elections before 1910.2

This slow pace of change did not reflect

a lack of organization. The suf-

fragists organized grassroots movements

in extremely imaginative ways, of-

ten attempting to link their cause with

those of other movements.3 At times,

women involved in the abolition and

temperance movements also became in-

Sam Tamburro is a historian with the

National Park Service and works in the Cuyahoga

Valley National Recreation Area. He

wishes to thank the staff at the Lake County Historical

Society for its assistance in locating

research materials and Dr. Carol Lasser of Oberlin

College for her thoughtful and observant

comments on the article.

1. The campaign for women's suffrage is

amply described in Eleanor Flexner, Century of

Struggle: The Women's Rights Movement

in the United States (Cambridge,

Mass., 1959);

Aileen S. Kraditor, The Ideas of the

Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890-1920 (New York,

1965); William O'Neill, Everyone was

Brave: The Rise and Fall of Feminism in America

(Chicago, 1969) and Feminism in

America: A History (New Brunswick, N.J., 1989); Janet

Zollinger Giele, Two Paths to Women's

Equality: Temperance, Suffrage, and the Origins of

Modern Feminism (New York, 1995); The Concise History of Woman

Suffrage, Mari Jo and

Paul Buhle, eds. (Chicago, 1978); and

Ellen Carol DuBois, Feminism and Suffrage: The

Emergence of an Independent Women's

Suffrage Movement in America, 1848-1869 (Ithaca,

N.Y., 1978); and Elizabeth Cady Stanton,

Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, et al.,

History of Woman Suffrage, vols. 1-6 (Rochester, N.Y., 1881-1902).

2. For a detailed description of the

progression of the women's suffrage cause after the

Civil War, see Flexner, Century of

Struggle and DuBois, Feminism and Suffrage.

3. According to DuBois in Feminism

and Suffrage, Stanton and Anthony attempted to estab-

lish women's suffrage as an independent

political movement by linking it with the emerging or-

ganized labor movement. The result was

the formation of the Working Women's Association

(WWA), a female wing of the National

Labor Union (NLU).

(614) 297-2300