Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

AMY HILL SHEVITZ

"Bull Moose" Rabbi: Judaism and

Progressivism in the Life of a

Reform Rabbi

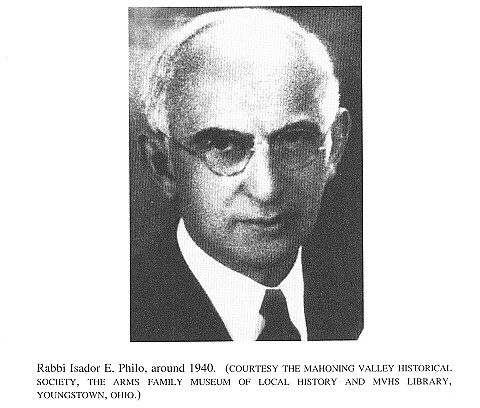

"When he spoke," Mrs. R. told

me, "it was just like the voice of God."

This is how one of his congregants

described Rabbi Isador Philo almost

fifty years after his death. His

successor in the pulpit of Reform temple

Rodef Sholom in Youngstown, Ohio,

eulogized Philo in 1948 with similar

words: "He was blessed with a rich,

resonant voice and a keen analytical

mind...his entire dignified physical appearance

and spiritual bearing were

those of one who walks with God."

Philo himself would have been most

pleased with another turn of phrase from

his successor, who praised the late

rabbi's "prophet-like restlessness

as a soldier of the Almighty."l

What was it that made this man so

impressive that though he had only a

regional career, he is remembered by

many in his local community as such a

source of Jewish pride? Certainly

dramatic flair was part of his appeal-and

his slight British accent could not have

hurt.2 But when we peel away the

layers surrounding the local myth of

Isador Philo, we encounter the fascinat-

ing story of an immigrant boy who

literally created his persona out of an am-

bition to become the perfect American

Jew. Isador Philo's life and career

provide an excellent case study of the

complex interplay of personality, op-

portunity, social mores, and Jewish

values which comprise the process of

"Americanization." Especially

compelling is the fact that Philo, adapting

himself in a way specific to his era and

its values, shaped for himself an intel-

lectual synthesis which illumines a

critical aspect of the intersection of

Judaism and Americanism in the early

twentieth century.

Little can be verified about Philo's

family, childhood, and education. He

was born on July 24, 1873, in Cardiff,

Wales. His family had immigrated to

Great Britain from Breslau, Germany, not

much before Isador's birth, in the

Amy Hill Shevitz is Instructor in

American Jewish History at California State University,

Northridge, and the University of

Judaism (Los Angeles). A doctoral candidate in American

history at the University of Oklahoma,

she is writing her dissertation on the small Jewish com-

munities of the Ohio River Valley.

1. Obituary of Isador Philo by Sidney

Berkowitz, Central Conference of American Rabbis

[CCAR] Yearbook, 59 (1949), 251.

2. Irving Ozer, et al., These are the

Names: The History of the Jews of Greater Youngstown,

Ohio, 1865 to 1990 (Youngstown, 1994), 91.

|

"Bull Moose" Rabbi 7 |

|

process Hellenizing the original family name of Lieb.3 Isador's father, Solomon, was born in Breslau in 1850.4 The Breslau Jewish community was the site of major communal struggles over religious reform beginning in the mid-1830s,5 so almost certainly Solomon was exposed to reforming ideas, whether or not he agreed with them. Most likely, Solomon, a fifth- generation rabbi trained in an Orthodox yeshiva, did not.6 Around 1880, the Philo family emigrated to North America, living in British Columbia and then in San Francisco.7 From this time until the be-

3. Jonathan P. Kendall, "Philo: A Biography" (Rabbinic thesis, Hebrew Union College, 1974), 1. Kendall is Philo's grandson. His work is useful, though it contains errors. Wherever possible, I have verified his data in reference or archival sources; otherwise, I have double- checked with other family members. 4. Cyrus Adler, ed., American Jewish Year Book 5664 (1903-04) (Philadelphia, 1903), 87. 5. Michael Meyer, Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism (Detroit, 1990), 97. 6. Kendall, "Philo: A Biography," 3; American Jewish Year Book 5664 , 87. On the other hand, why Hellenize rather than Anglicize the name? 7. Kendall, "Philo: A Biography," 2. |

8 OHIO

HISTORY

ginning of his career, Isador Philo's

life is a mystery. A biographical entry

for him in the 1903 American Jewish

Yearbook lists a B.A. from the City

College of New York and a Ph.D. from the

University of Illinois.8 Neither

of these claims is true.

According to Philo's grandsons, he

graduated from Columbia University in

1897 and took his rabbinical studies at

the Temple Emanu-El Seminary.9

Unfortunately, there is no documentary

evidence for these statements either.

Columbia University has no record of

him, and certain inconsistencies on his

diploma, which is extant, render it

questionable.l0 The Seminary at Temple

Emanu-El, organized as a radical Reform alternative

to the Hebrew Union

College, was not a functioning

institution after the mid- 1870s. It did provide

preparatory studies to students who then

continued at HUC or in Europe, but

there is no record that Philo was a

sponsored student. 11 Even

during Philo's

lifetime, questions were raised about

his ordination. In the 1903 American

Jewish Year Book biography, Philo claimed he was ordained by the Rev.

Dr.

Falk Vidaver of San Francisco.12 Vidaver was rabbi of Congregation

Shearith Israel during its transition to

Reform and may well have influenced

the young Philo's ideas in that

direction. Later in his career, many people in

Youngstown were skeptical of Philo's

ordination altogether.13

Whatever credentials he presented, Philo

took his first pulpit at Temple

Israel of Akron, Ohio, where he arrived

in the fall of 1897 at age twenty-

four.14 A local newspaper

reported that he had come to Akron from Altoona,

Pennsylvania, which was near the

hometown (Huntingdon, Pa.) of the

woman he had married just that summer.

In his earliest efforts, he impressed

people with his oratory. "He is

very pleasant in his address," the local paper

opined, "a deep thinker, a scholar,

and is sure to meet with success in

Akron."15

After ten years in the Akron pulpit,

Philo briefly left the rabbinate. For

several years, he had been reading law,

and in June 1907 he was admitted to

the Ohio bar.16 He kept a law

practice open in Akron until 1912, but in

8. American Jewish Year Book 5664 , 86.

9. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 3.

10. Philo Wasburn, letter to author,

March 28, 1996; author's telephone conversation with

Holly Haswell of the Columbiana

Archives, Columbia University, April 2, 1996.

11. Bertram Korn, "The Temple

Emanu-El Theological Seminary of New York City," in

Essays in American Jewish History, ed. Jacob R. Marcus (Cincinnati, 1958), 367.

12. American Jewish Year Book 5664,

86.

13. Biography of Isador Philo,

Collection #92, Youngstown Area Jewish Federation-Jewish

Archives, Mahoning Valley Historical

Society, Youngstown, Ohio.

14. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 5.

15. "Rabbi Philo's Successful

Beginning," clipping of article from unnamed newspaper,

reprinted from Akron Evening Journal,

March 6, [1898?] (Isador Philo-Nearprint Collection,

American Jewish Archives [AJA],

Cincinnati, Ohio).

16. Author's telephone conversation with

Attorney Registration Office, Supreme Court of

Ohio, March 29, 1996. Kendall mistakenly

says 1910.

"Bull Moose" Rabbi 9

1911 also began serving as occasional

substitute rabbi at Reform congrega-

tion Rodef Sholom in the steel city of

Youngstown, fifty miles from Akron.

When the ailing senior rabbi retired the

following year, Philo took his

place.17 He stayed in the

Youngstown pulpit until he retired in 1942. He

died six years later.

Both as a Jew and as an American, Philo

was quite literally a self-made

man. He seems to have emerged full-blown

into his career. Though his in-

tellectual and spiritual development

before 1897 are obscured, what is notable

is the persona which emerged. When he

came of age in the 1890s, progres-

sivism in politics and Reform Judaism in

religion were the hallmarks of

modernity.18 These two

movements presented themselves as mechanisms for

enlightenment and progress, as sure

roads to a better future. Philo had created

his American persona from the raw

materials of the ambient culture, includ-

ing, in a rising "culture of

professionalism," the appropriate-and appropri-

ated-academic credentials. He would be

no pathetic Orthodox "Reverend,"

eking out a living at the bottom of the

Jewish social scale.

The central characteristic of Philo' s

career was his attempt to merge Reform

Judaism with progressivism in the search

for true Americanism. Melvin

Urofsky has said of Rabbi Stephen S.

Wise (with whom Philo shared many

personal and intellectual characteristics),

"One can only understand his

Americanism through his passionate

Judaism, and his Judaism through his

fervent Americanism."19 For

Wise, "politics was but an extension of reli-

gion."20 For Philo,

progressive politics and liberal religion were one and the

same; one's religious duties and one's

civic duties were equivalent. Through

the years, he maintained his faith that

a synthesis of progressivism and

Reform Judaism was possible. In reality,

he was pulled between these two

attractive forces, and in the long run,

the effort failed.

The major activities of Philo's

rabbinate exemplify this effort. In the late

nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries, American Reform Judaism reached

its classical peak. Inspired by the

Protestant Social Gospel movement, Jews

began to involve themselves in

progressive social and political reform. "For

the Reform rabbinate as a whole,"

observes one scholar, "the transition from

17. Ozer, et al., These are the

Names, 87.

18. The Reform movement in Judaism arose

as a "response to modernity" in the wake of

Jewish emancipation in Western Europe.

Classically, the movement was characterized by ra-

tionalism, a universalized messianism,

an emphasis on ethical monotheism and the Prophets,

and the replacement of traditional Jewish

law with personal autonomy. Reform dispensed with

many traditional ritual practices and

(especially in America) acquired a pronounced Protestant

style. See Michael Meyer, Response to

Modernity, and Leon Jick, The Americanization of the

Synagogue (Hanover, N.H., 1976).

19. Melvin Urofsky, A Voice that

Spoke for Justice; The Life and Times of Stephen S. Wise

(Albany, 1982), viii. There are many

similarities and coincidences in the ideas and careers of

Wise and Philo. It is certainly possible

that Philo modeled himself after Wise.

20. Urofsky, A Voice that Spoke for

Justice, 106.

10 OHIO

HISTORY

a prophetic Judaism that spoke only of

individual conduct to one that ad-

dressed specific social issues is

ascribable to two outside influences:

the

American Progressive movement and the

Christian Social Gospel."21 As an-

other historian describes it, "Led

by a younger generation of rabbis, the

Reform movement then began to march to

the distinctively evangelical ca-

dences of the Progressive movement...."22

In Akron, Ohio, Isador Philo marched

right along with the others. His ear-

liest published remarks are replete with

the language of progressive reform.

Akron was a company town, the rubber

capital of the world, and Philo took a

special interest in labor issues. He

gave pro-union sermons, for instance, in

1904 when he announced,

"Organization on the part of the laboring class is a

moral, intellectual and physical

necessity. It is only by association that the

individual can render his best products

and receive the highest reward for his

work...."23 Unionism's moral quality was

socially transformative.

"Socialism will not solve the

problem," he argued in a 1903 speech at local

Labor Day festivities. "What will?

Laborers must become their own capital-

ist[s]. By combining their savings the

laboring men will be able to employ

themselves."24

Thus, in Philo's rhetoric, the cause of

labor took on religious overtones.

In a speech to an Akron men's club, he

called on the members to fight-as

Christians-injustices perpetrated by the

rubber companies.25 He wrote that

Akron needed a "People's

Church," referring to the People's Church estab-

lished in New York City in 1899, which

its founder called a "creedless church

for creedless people."26 Such

a church would bring workers back to religion,

providing, in Philo's opinion, far more

moral uplift to the workingman than

would liquor regulation.27

In the rhetorical extreme, Philo's

religious and social ideologies fused:

"...organized labor created the

world. God Almighty was the first union la-

borer. He brought harmony out of chaos

and order out of confusion by apply-

ing the principle of organized creation

to the unorganized and inert forces of

nature...."28 Likewise, his role as

rabbi fused with that of labor arbitrator.

21. Meyer, Response to Modernity, 287.

22. Jerold S. Auerbach, Rabbis and

Lawyers: The Journey from Torah to Constitution

(Bloomington, Ind., 1990), 82.

23. "The Unions," sermon given

March 1904, Temple Israel of Akron, quoted in Kendall,

"Philo: A Biography," 7.

24. "'Unionism Must Grow in Power

by the Nature of the Men it Produces,"' clipping from

unknown newspaper [Akron?, early

September 1903] (AJA).

25. "Sunday Talk," manuscript

dated May 4, 1901, quoted in Kendall, "Philo: A Biography,"

8-9.

26. Egal Feldman, Dual Destinies: The

Jewish Encounter with Protestant America (Urbana,

Ill., 1990), 127.

27. "A Few Things Tha[t] Akron

Needs," Akron Beacon-Journal, December 19, 1903

(AJA).

28. Address before the Central Labor

Union of Akron, June 30, 1904, quoted in Kendall,

"Bull Moose" Rabbi

11

As the idea of clergy serving as labor

mediators spread through American in-

dustry, Philo was one of the first

rabbis to assume this role.29 In 1902, he

mediated a strike at an Akron rubber

plant. Although he was not ultimately

successful in reaching an agreement

entirely on the union's terms, the work-

ers still awarded him a certificate of

appreciation.30

Other political views he also infused

and expressed with religious fervor.

In 1901, after a brief trip to Cuba,

Philo told the Akron Beacon-Journal that

"the historical argument for the

existence of a God predicates the finger in the

new condition of affairs.... I recognize

a divinity which has surely shaped the

end for our new possessions. Cuba is

ours, I hope, forever." After all, the

United States was the Moses that

liberated Cuba from the tyranny of Pharaoh

Spain.31 His

progressive passion for municipal reform also echoed the work

of the Social Gospel movement. Asked in

1903 by a Cleveland newspaper

for his views on the upcoming mayoral

race in Akron, Philo declared, "We

have plenty of politics in morals, but

no morals in politics. We have had

many political puppets, but few

political patriarchs. Morals and politics are

deadly enemies.... We need a man for mayor...who understands

that

American citizenship must be at the

highest service of all the people all the

time."32

The "highest service of all the

people all the time" was also the essence of

his universalist religious creed. Early

in his Akron years, Philo publicly ar-

ticulated religious universalism. Almost

as soon as he arrived in the city,33

he participated in pulpit exchanges, a

popular feature of liberal religion in the

1890s.34 " [L]et us

forget our disagreements," he told his Christian and

Jewish hearers, "...let us

accentuate our agreements."35

In 1902, he openly approved of rabbinic

officiation at intermarriages, under

certain circumstances, in language more

usually associated with Christianity:

"It is the spiritual aim of Judaism

to unite all the children of man in peace

and love and to bring them to the Father

of all.... When a Jewish man or

woman has reached that pass where marriage

with a Christian is inevitable...

I would marry them on the broad

principle that it is not the aim of

religion to

"Philo: A Biography," 7.

29. Leonard Mervis, "The Social

Justice Movement of the American Rabbis, 1890-1940"

(Ph.D. diss., University of Pittsburgh,

1951), 122.

30. "He Throws Up His Hands,"

undated clipping from unknown newspaper [Akron? 1902]

(AJA) and "Rabbi Philo's Effort to

Settle a Strike Fails," American Israelite, October 9, 1902,

6. See also Mervis, 123. Kendall

("Philo: A Biography," 7-8) mistakenly says 1905.

31. "Ours For All Time," Akron

Beacon-Journal [sometime after mid-July 1901] (AJA).

32. "Our Mayor Should Be a

Man," Cleveland Press, January 22, 1903 (AJA).

33. "A Sign of the Times," Akron

Beacon-Journal, May 26, 1898 (AJA).

34. Naomi Cohen, Encounter with

Emancipation: The German Jews in the United States,

1830-1914 (Philadelphia, 1984), 202.

35. "Since You Asked," Akron

Beacon-Journal, May 29, 1901 [?], quoted in Kendall,

"Philo: A Biography," 9.

12 OHIO HISTORY

separate those who truly love each

other.... God is love. Religion is love.

The basic principle of marriage is

love." What circumstances would qualify

for rabbinic officiation? Philo was

clear: it would be "a marriage between

Jew and Christian of equal social and

moral position...where no serious reli-

gious discrepancy exists" [emphasis added]. After all, he continued, Judaism

"as a sublime truth is destined to

become the common heritage of all

mankind. Intermarriage can in no way

impede or weaken its purpose."36

Philo exhibited a stubborn, even

defiant, pride as he asserted his understand-

ing of Judaism in the world. In a 1906

sermon on antisemitism, he pro-

claimed to his congregation, "We

can go to the sour cream of society and tell

them that when their ancestors were

groveling like swine in the filth of ani-

malism, the Jews were kings and princes,

the prosecuers [sic-precursors?]

and prophets of the world."37 Remarkably

enough, this sermon was pub-

lished in a local newspaper.

This statement was not, however, an

assertion of particularism, and "the

highest service of all the people all

the time," the essence of his universalist

religious creed, led Philo into his

brief legal career. His motivation for tak-

ing up law, which he articulated in his

resignation from Temple Israel, was

similar to the goal of his rabbinate: to

work for "peace, harmony, brother-

hood and social commitment,"

without sacrificing the needs of his congrega-

tion.38

In fact, there was no striking change in

the tone of his public activism. In

1907 he gave another Labor Day oration.

Expounding on the virtues of

unionism and the eight-hour day, he

averred, "The world's greatest benefactors

have been strikers. Jesus, Roosevelt,

Moses, Isaiah, Galileo, Lincoln and

Washington are a few of the greatest

strikers the world has known."39 In this

remarkable set of examples, Philo

identified himself formally with political

progressivism, and Theodore Roosevelt

with the authentic heritage of both

America and true religion.

Through his brief, but intense, career

in the law, Philo bound together his

Judaism and his Americanism even more

tightly. Jerold Auerbach has shown

how American rabbis and Jewish lawyers

at the turn of the century created a

powerful synthesis of Judaism and

Americanism by merging the two legal

traditions to which they were heirs. The

legal profession promised an espe-

cially powerful link to the new country:

"Law, quite uniquely, could link

Jewish history to American destiny....

Jews could claim fidelity to the spirit

of their own sacred-law tradition

precisely as they replaced it with the rule of

36. "The Intermarriage

Question," American Israelite, September 18, 1902, 3.

37. "Jews Did Not Crucify

Christ," clipping from unknown newspaper, [Akron?], April 2,

1906 (AJA).

38. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 12.

39. "Dr. Philo Delivers Sensational

Speech," [Akron Times ?, September 3, 1907?] (AJA).

|

"Bull Moose" Rabbi 13 |

|

American law."40 If, as Auerbach argues, lawyers replaced rabbis as the community's arbiters of power, then what could have been a more impressive path of leadership than to be both a rabbi and a lawyer! Philo practiced law in Akron for five years, but he was disappointed with the realities of his new career. Rather than advocating the rights of the worker and fighting oppression of the poor, he found himself preparing wills and handling real estate transfers.41 Attracted by the moral aspects of the law, he was disillusioned that the routine of a lawyer's professional obligations might conflict with his personal morals. In 1910, they did so conflict, with great force, when Philo discovered that the man he had successfully defended against a charge of murder was in fact guilty. In his diary he agonized, "I cannot reconcile this event with my conscience or my God. And who is to say that it will not happen again?"42 Though the practice of law disappointed him, Philo remained optimistic about political progressivism. Northern Ohio was a hotbed of progressivism; progressives in Cleveland and Toledo were nationally-known leaders in mu-

40. Auerbach, Rabbis and Lawyers, xix. 41. Kendall, "Philo: A Biography," 14. 42. Philo's diary for 1910, quoted in Kendall, "Philo: A Biography," 17. |

14 OHIO

HISTORY

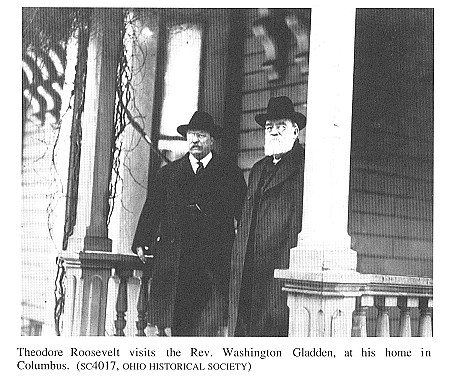

nicipal reform. Philo threw himself into

politics in 1912, following his hero

Theodore Roosevelt into the newly-formed

Progressive Party, the so-called

"Bull Moose." The ideals of

the party resonated with Philo's deeply opti-

mistic religio-political faith. In the

words of its national platform, the party

was "[u]nhampered by

tradition" yet also "born of the nation's sense of jus-

tice.... [dedicated] to the fulfillment

of the duty laid upon us by our fathers to

maintain the government of the people,

by the people, and for the peo-

ple...."43

Philo's activism was reinforced by a

personal meeting with Roosevelt in

early 1912, and he attended the national

Bull Moose convention in Chicago in

August of that year (though evidently as

an observer, not an official dele-

gate).44 The Ohio Bull Moose

also held a convention in Columbus the fol-

lowing month. The Chicago convention had

the exuberant and uplifting

spirit of an evangelical revival. At

Columbus, "[t]here was the same spirit of

mission among the rank and file of

delegates. Many of those present had

never attended a state convention before

and thought of themselves as soldiers

on the firing line, battling for the

Progressive party cause. The first session

opened with a blessing pronounced by

Washington Gladden, the reciting of

the Lord's Prayer in unison, and the

singing of 'America.'"45 The participa-

tion of Gladden, the Columbus clergyman

who was a pioneer in the Social

Gospel movement, must have been

particularly inspiring for Philo.46

As one scholar has observed, "For a

new party with an incomplete organi-

zation and a short time for campaigning,

[the Progressives] had made a re-

markable race."47 Despite

some success in the northern part of the state,

however, the Progressive crusade was

ultimately a failure. Under numerous

stresses and (in Ohio) riven by personal

ambitions, by 1916 the Party had

collapsed.48

Disappointed but not discouraged, Philo

devoted himself to the pulpit,

compensating for the failures of law and

politics with a rabbinic career of a

decidedly progressive tone. The 1915

dedication of Temple Rodef Sholom's

new building expressed his progressive

program. The goal of building was to

43. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ed., History

of U.S. Political Parties, Vol. III (New York,

1973), 2584.

44. "Ohio Bull Moose Hard at

Work," Buffalo Progressive, December 5, 1912; Kendall,

"Philo: A Biography," 28.

45. Hoyt Landon Warner, Progressivism

in Ohio, 1897-1917 (Columbus, 1964), 372.

46. It was reported in one newspaper

that Philo ran for office on the Progressive Party ticket

("Ohio Bull Moose Hard at

Work," Buffalo Progressive, December 5, 1912). This is evidently

erroneous since state records do not

list him as a candidate. Rabbi Gerson Levi of Chicago

was a Progressive Party candidate for

county commissioner in 1914, and Rabbi Samuel

Goldenson refused a Progressive

nomination for mayor of Albany, New York (see Mervis,

"Social Justice Movement,"

118-19).

47. Warner, Progressivism in Ohio, 376.

48. Warner, Progressivism in Ohio, 373.

"Bull Moose" Rabbi

15

"make the new Temple an expression

of the modem idea of the relation of the

church to humanity. Until a few years

ago the church was merely a place of

worship...to be used for services; now

and then for a church supper....

Within the last few years the conception

has changed; the new idea is part of

the renewal-the revitalizing one might

call it-of democracy, that has been

going on in this country. The church,

men are saying, must not keep aloof

from the common life of humanity; she

must take more active part in it than

ever.... In this time of great popular

movements, it must aim to influence

man on all his sides, in order to make

its character properly felt."49

Like many other former Bull-Moosers,

Philo turned to the other progres-

sive alternative, Woodrow Wilson, in

1916 and, like most progressives,

avidly supported United States

participation in the first World War. His 1918

prowar speech at Temple Rodef Sholom of

Pittsburgh was notable in several

respects. For one thing, Philo's

exaggerated protestations of Jewish alle-

giance to the United States suggest the

preposterous lengths to which

American Jews could go to prove their

patriotism: "There was never a time

in the history of the Jewish people,

under even the most unfavorable condi-

tions, when they failed to fill the

measure of devotion to the land of their

birth or adoption.... In Russia, dark

Russia, that until yesterday denied them

the common rights of common men, that

persecuted and pogromed, mal-

treated and maimed them,-their hearts,

though sorely rent, were faithful

still."50 One wonders if

many immigrant Jews from Russia would have

agreed.

Equally notable-and characteristic-is Philo's

fusion of the languages of

Jewish religious messianism and of

Wilsonian progressive messianism, what

has been called Wilson's

"Presbyterian foreign policy."51 The hoped-for

Allied victory had a distinctively

Jewish meaning: "the justification

of

Israel's mission, and the vindication of

his religious ministry. It means the

dawn of Israel's Messianic hope, the

ripening of the fruit of his religious

tree...." Yet the Allied victory

would also redeem in a peculiarly Christian

way: it "means a world redeemed

from its sins, chastened and purified...;"52

"[n]ational sin invites national

suicide. The wage of sin is death."53

Like many progressives, Philo was

disillusioned by World War I. Early in

the war, he began to despair, writing in

his diary, "reconciliation between

peoples and nations might have spared

[the soldiers'] lives and limbs....

49. "Dedication of the Magnificent

New Rodef Sholem Temple," Youngstown Vindicator,

June 6, 1915.

50. "The American Jew and the

War," reprint of lecture given April 21, 1918, Rodef

Shalom Congregation, Pittsburgh, Pa.,

1-2 (AJA).

51. Robert M. Crunden, Ministers of

Reform: The Progressives' Achievement in American

Civilization, 1889-1920 (New York, 1982), 225.

52. "The American Jew and the

War," 7.

53. "The American Jew and the

War," 15.

16 OHIO

HISTORY

nothing can be worth all of this

sorrow...."54 In 1918, he could still write

that "the success of America and

her Allies means the realization of the age-

long dream we have cherished-of humanity

emancipated.... It means the

making over of the old world...."55

In the 1920s, he was far less sanguine

about humanity's ability to force this

change. Commenting on the outlawry

of war movement, Philo agreed that the

movement's goal was noble and de-

sirable. But, he continued, before war

can be outlawed, "we must outlaw fear

from the human mind, hate from the

social heart, jealousy from the interna-

tional soul. And that demands a long and

large and deep education, the very

elements of which we are not yet

equipped to teach."56

But Philo still had his optimistic

religious faith to fall back on. As schol-

ars have pointed out, after the Great

War, American Jews remained more lib-

eral than Christians because the

inevitability of sin was not their intellectual

default.57 For all of Philo's

sin-laden, pseudo-Christian rhetoric, the experi-

ence of the war in fact invigorated his

sense of mission by providing oppor-

tunities, such as chaplaincy activities

at local army camps, for humanitarian

work and public exposure.58

After the war, Philo continued to

further his reputation as one of

Youngstown's preeminent liberal

spokesmen. In the 1920s, he wrote a regu-

lar column in the Youngstown

Vindicator under the pseudonym "Straw Bored

Green." He commented on local and

national events and politics in a light-

hearted tone, always emphasizing liberal

religion, enlightened morality, vir-

tuous government, worker rights, racial

equality, tolerance, and world peace.

Not surprisingly, interfaith relations

were high on his agenda. He was a

founder of Youngstown's Inter-Racial

League in 1922.59 He kept a hand in

labor relations, helping negotiate the

Youngstown Steel strike in 193760 and

a construction union contract in 1941.61

The greatest social conflict in

Youngstown during Philo's tenure was

caused by the rise of the Ku Klux Klan

in the early 1920s. The Great Lakes

54. Philo's diary for 1917, quoted in

Kendall, "Philo: A Biography," 29.

55. "The American Jew and the

War," 6-7.

56. Writing as Maftir in "Notes and

Comments," B'nai B'rith Messenger (Los Angeles), late

1925-early 1926 (AJA).

"Maftir" was the pseudonym used by Isidor Choynski, the San

Francisco correspondent of the American

Israelite from 1874 to 1893. Philo's adoption of this

pseudonym suggests his early San

Francisco connection (see above). In synagogue practice,

the maftir is the final section of the

weekly reading from the Torah (Pentateuch). By exten-

sion, it also designates the person who

reads this section -- in effect, the one with the "last

word."

57. Feldman, Dual Destinies, 198-99.

58. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 30.

59. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 34.

60. Obituary by Sidney Berkowitz in CCAR

Yearbook, 251; also, "Rabbi I.E. Philo is Dead at

74," Youngstown Vindicator, July

17, 1948.

61. "Metal Workers Get Pay

Raise," clipping from unknown newspaper, [Youngstown

Vindicator ?, sometime after 1937] (AJA).

"Bull Moose" Rabbi

17

Klan managed to enlist many ministers

with its program for the preservation

of so-called traditional Protestant

values.62 In alliance

with liberal

Protestants and Catholics, Youngstown

Jews, including, of course, Isador

Philo, were actively involved in the

battle to set the terms of social discourse.

Fighting the Klan's rhetoric of 100

percent Americanism, the local B'nai

B'rith charged the Klan itself with

being "un-American."63 Youngstown

Jews believed, in the words of one

liberal (Protestant) writer reprinted in a lo-

cal synagogue bulletin, that

"American liberalism... is and always has been

the true Americanism."64

In the long run, the Klan in industrial

northern Ohio stumbled over the fact

that ethnic diversity was an accepted

part of the social and cultural landscape

of the region. In 1922, the Klan

attempted to co-opt all religious groups

through a proposal that a joint

Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish commission

(consisting of representatives of the

Klan, the Knights of Columbus, and

B'nai B'rith) develop a religious

education curriculum for the Youngstown

public schools.65 This

"unite and conquer" strategy did not convince a suspi-

cious, multiethnic school board.66 A

few years later, "Straw Bored Green"

crowed cheerfully that the Ku Klux Klan

was "dead and buried, awaiting the

Judgment Day."67

But neither the failure of political

progressivism, the disappointments of

the war, nor the domestic intolerance of

the 1920s constituted the greatest

challenge to Philo's optimistic

synthesis of Reform Judaism and progres-

sivism. His religious liberalism had

already undergone considerable stress in

the wake of his suggestion, in his 1923

Rosh Hashanah sermon, that Sunday

be made the primary day for Jewish

communal worskhip.68 The rabbis of

several congregations in nearby cities

had instituted this practice, including

Abba Hillel Silver in Cleveland and J.

Leonard Levy in Pittsburgh, and the

idea was still gaining adherents in the

1920s.69 The response of the local

Orthodox was predictably harsh, but that

was not the reason Philo recanted

his proposal only ten days later in his

Yom Kippur sermon. Philo privately

scorned the Orthodox, though he was

publicly cordial, and their opposition

would, if anything, have hardened his

position.70 (He bragged about being a

62. See William D. Jenkins, Steel

Valley Klan: The Ku Klux Klan in Ohio's Mahoning Valley

(Kent, Ohio, 1990).

63. Youngstown Vindicator, December

6, 1922.

64. William Robinson Pattangall,

"100% Americans?" Anshe Emeth Recorder, 2 (October

1925), 13-14 (Mahoning Valley Historical

Society).

65. Youngstown Vindicator, December

9, 1922.

66. Youngstown Vindicator, December

5, 1922.

67. Writing as Straw Bored Green,

"News and Views," Sunday Vindicator [1929] (AJA).

68. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 36-38.

69. Meyer, Response to Modernity, 290-91,

328.

70. Source for Philo's privately

expressed opinion is his daughter (Kendall's mother), Ann

Philo Kendall. For his public

cordiality, see Ozer, et. al., These are the Names, 74.

18 OHIO HISTORY

rebellious and independent yeshiva

bochur.71) Rather, Philo recanted because

of the positive reaction from many

Christians. Their suggestions that he had

begun to see the light that would

inevitably lead him to Christianity caused

an instinctive, and rapid, withdrawal.

The greatest challenge to his psychic

unity was Zionism. Not surpris-

ingly, early in his career he considered

Zionism a chimera. Both physically

and culturally, America was to be the

salvation of the Jews.72 But as the ap-

peal of Zionism to American Jews grew

under the influence of Louis

Brandeis, the Wilsonian progressive,

Philo was caught up in the rising tide.

In 1916, he wrote a glowing letter to

Brandeis, reporting, "somewhat over-en-

thusiastically," that 90 percent of

Youngstown Jews were confirmed

Zionists.73

What sort of Zionist Philo considered

himself to be is open to debate.

Whether or not he was persuaded by

Brandeis's synthesis of Zionism and

Americanism, he was clearly not

persuaded by his emphasis on the practical

upbuilding of the land. In the 1920s,

Philo described himself in a B'nai

B'rith publication as a non-Zionist, not

an anti-Zionist: "On the whole phi-

losophy of Zionism, I have an open mind.

Only the educational, the spiri-

tual, the cultural sides of the

experiment appeal to me as having value."

Neither the economic development of

Palestine nor its potential role as a

refuge met his criteria for spiritual

goals.74 In a 1929 article, he advocated

the internationalization of the entire

Holy Land. While he based his position

partly on mistrust of the British, he

also thought that a Palestine which was

"a ward of the world" would

more likely achieve a condition appropriate to its

spiritual past as "the land of the

Prophets and Apostles."75

In 1931, Philo went to Vienna as

Youngstown's representative to an inter-

national Rotary convention. On the trip, he also visited Germany and

Palestine. His travel diary reveals

ambivalence about both places. Passing

through Germany, he wrote that he felt

"a cold, uneasy feeling, like hearing a

strange noise in the basement, but not

wanting to go down to look for fear of

what one might find."76 Yet

he changed his travel plans so he could spend

more time there.

71. Writing as Maftir in "Notes and

Comments," B'nai B'rith Messenger (Los Angeles),

[1920's?] (AJA)

72. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 49.

73. Letters of Louis D.

Brandeis. Vol. IV, 1916-1921, ed. Melvin I. Urofsky and David W.

Levy (Albany, N.Y., 1975), 13-14.

74. Writing as Maftir in "Notes and

Comments," B'nai B'rith Messenger (Los Angeles),

[1920's?] (AJA).

75. Writing as Straw Bored Green,

"News and Views," Youngstown Vindicator, September

1, 1929 (AJA).

76. Philo's diary for June-August 1931,

quoted in Kendall, "Philo: A Biography," 47.

"Bull Moose" Rabbi

19

Somewhat to his surprise, he had a

positive personal religious reaction to

Palestine.77 However, he

wrote in his diary, "Someday Palestine will be a

homeland for the Jewish people, but I

have my reservations. If there is ever a

State of Palestine, I doubt seriously

whether there will be peace in the

world."78 Whatever his

reservations, Philo became openly pro-Zionist in the

years following his trip to Palestine,

the years of the rise of Nazism. He

gave sermons and helped organize

"town hall meetings" to promote

Zionism.79 He took a

prominent role in the Youngstown Zionist District.80

His reservations were, if overcome by

activism at one level, sufficiently

obvious to cause problems at another.

People in the Youngstown Jewish

community felt that they received very

mixed messages from him about

Zionism. One local activist said, in

retrospect, that Philo was "of doubtful

value" to the cause, though the

Zionists cultivated him because of his stand-

ing in the community. They had to

maintain a precarious balance. During

World War II, the now-retired Rabbi

Philo was serving a small Reform con-

gregation in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, on

a part-time visiting basis.

Youngstown Zionist activists were so

alarmed by what they perceived to be

Philo's anti-Zionist messages there that

they arranged for Rabbi James Heller

of the Zionist Organization of America

(ZOA) to speak in Youngstown, to

counteract Philo's presumably negative

impact in their own community.

Scoffed a Youngstown Zionist,

"...Philo was very elusive about Zionism.

He was clever with words and had a knack

for avoiding the issues."81 Even in

1994, the writers of a local communal

history (none of whom seem to be

Reform) alleged that throughout the

1930s and 1940s, Philo "continued to

confuse the community with his

inconsistent stand on the Zionist

Movement."82

Others have been more sympathetic,

laying the blame on divisions over

Zionism within Temple Rodef Sholom. One

Youngstown Zionist suggested

that Philo, in deference to, if not in

agreement with, his congregation, was an

anti-Zionist early in his career:

"Toward the middle, he seemed to vacillate,

being quite inconsistent in his public

statements, according to current circum-

stances." This observer felt that

by the end of Philo's full-time career in

1942, as his congregation's mood

changed, Philo had become pro-Zionist.83

77. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 49.

78. Philo's diary for 1931, quoted in

Jonathan Kendall, "An Intellectual Digest of Rev. Dr.

Isador E. Philo, 1873-1946 [sic]"

(paper for History Special Readings course with Dr. Stanley

Chyet, Hebrew Union College, 1972), 8.

79. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 83; Ozer, et al., These are the Names, 68.

80. Ozer, et al., These are the

Names, 68.

81. Biography of Isador Philo,

Youngstown Area Jewish Federation Archives.

82. Ozer, et al., These are the

Names, 163.

83. Ozer, et al., These are the Names,

92.

20 OHIO

HISTORY

Setting these various partisan

statements into the highly charged emotional

context of wartime Zionism sheds light

both on the nature of these confu-

sions and conflicts and on the

increasing tenuousness of Philo's progressivist

religious synthesis. Youngstown's

Zionist activists were largely from the

Orthodox, East European community, a

group not disposed to think well of

Reform rabbis. As evidence of Philo's

duplicitousness, the writers of the

communal history offer the following

quotation from a 1938 speech:

"Millions of Jews love Palestine,

because it is a land they can call their own.

They have transformed swamps into orange

groves.... We are asking our-

selves now if Palestine is destined to

suffer the same fate as Czechoslovakia.

Are treaties to be ruthlessly cast

away? England has juggled with the

[Balfour] declaration in many ways. I cannot understand the attitude of

England, with a great history behind

her. A Jewish homeland does not mean

that the rights of Arabs will be

destroyed, but that the Jews want a country in

which they will have a majority."84

It is hard not to think that on this

occasion, at least, the Zionists "heard"

anti-Zionism because that is what they

expected to hear from this relic of

Classical Reform. As the situation of

European Jewry worsened, American

Zionists became increasingly

"aggressive and nationalistic," especially after

the Biltmore conference of 1942.85

Anything less than national sovereignty

seemed dangerously naive, and Philo

seemed to the Zionists to be-at the

very least-indulging in this naivete.

Undoubtedly Philo was under stress from

the antagonisms he saw in the

Jewish community. He was acquainted or

friendly with Reform rabbis on

both ends of the Zionist spectrum. On

the one hand, he had cordial social

contact with the liberal Zionist Rabbi

Stephen S. Wise and respected him

greatly.86 On the other hand,

one of the speakers at Temple Rodef Sholom's

75th anniversary in 1937 was Rabbi

Samuel Goldenson, a former political

progressive and "close friend of

Dr. Philo," later a prominent anti-Zionist ac-

tivist.87

Likewise, Philo's congregation was

seriously divided. Henry Moyer, one-

time president of the congregation,

emerged in the late 1940s as a significant

lay leader of the anti-Zionist American

Council for Judaism.88 In 1945, the

Rodef Sholom board, facing objections to

Moyer's views, but too mixed to

84. Ozer, et al., These are the

Names, 265.

85. Melvin I. Urofsky, American

Zionism from Herzl to the Holocaust (New York, 1975),

421.

86. Ozer, et al., These are the

Names, 89.

87. Ozer, et al., These are the

Names, 91.

88. Thomas A. Kolsky, Jews Against

Zionism: The American Council for Judaism, 1942-1948

(Philadelphia, 1990), 82. The Council

was founded by a minority of Reform rabbis critical of

their rabbinical association's support

of political Zionism, a position which they considered in-

compatible with true

"prophetic" Judaism and with American citizenship."

"Bull Moose" Rabbi

21

have a unified position, felt compelled

to pass a resolution that a member's

personal position on Zionism would

"in no wise impair his or her standing or

function with the Congregation."89

As his progressive optimism was

increasingly mocked by events, Philo

tried harder and harder to maintain his

synthesis of social progressivism and

universalist Reform Judaism. His

statements about Zionism echoed his con-

fusion. Disliking the anti-religious

stance of many Zionists, Philo tried to

distinguish between a '"pure

Zionism,'" which was nationalistic, and "true

Zionism," which was spiritual. He

tried to synthesize a non-nationalist

Zionism from his universalism and his

progressivism, not in practical

Brandeisian terms, but as somehow a

humanistic idea divorced from mere ge-

ographic considerations.90

So he clung to an impossible dream,

using terminology that could only

confuse his hearers: "Zionism

without Judaism is like theology without reli-

gion...patriotism as a national religion

is desirable when patriotism is more

than the creed of narrow politicians....

Nationalism as the religion of, by and

for the people has much to commend it

when it is more than geographical....

Humanism, the civilization of tomorrow,

will be a blend of Zionistic ideal-

ism, patriotic zeal and national

internationalism."91

It is therefore only slightly startling

to discover Philo's association with

the American Council for Judaism. He was

not among the rabbis who signed

the Council's anti-Zionist manifesto

published in the New York Times on

August 31, 1943.92 However, the previous

month he had sent membership

dues to the Council. The acknowledgement

letter from Rabbi Elmer Berger is

addressed to "Mr." Isador

Philo, with no street address.93 Was this because

someone else-perhaps Moyer-had convinced

Philo to join and had for-

warded his dues check? Or was it a

deliberate concealment of his rabbinical

status? Was he ambivalent about public

association with such a controversial

minority opinion?

For Philo, Zionism posed a dilemma with

no resolution. He was torn. He

believed in the Council's commitments to

a universal Jewish mission and to

89. Board meeting minutes for May 13,

1945, courtesy of Congregation Rodef Sholom,

Youngstown, Ohio.

90. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 55.

91. Quoted in Kendall,

"Intellectual Digest," 9.

92. Kolsky, Jews Against Zionism, 207.

There was a strong correlation between political and

social liberalism and anti-Zionism in

the careers of other Reform rabbis. In "The Social Justice

Movement of the American Reform

Rabbis," Leonard Mervis studied forty rabbis, chosen as

exemplars of social justice activism,

with no mention of their positions on Zionism. Of the

twenty-seven identified by Mervis who

were alive in 1943, over one-third were Council mem-

bers, even though the Council

represented a much smaller minority of the Reform rabbinate

overall.

93. Letter from Rabbi Elmer Berger to

Isador E. Philo, July 13, 1943, American Council for

Judaism Papers, State Historical Society

of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin.

22 OHIO HISTORY

liberal democracy. When prominent Reform anti-Zionists, like Julian

Morgenstern, realized that historical

circumstances forced a practical re-evalua-

tion of liberal expansiveness at the

practical expense of Jewish lives, they

cast their lots with Zionism. Philo

failed the test of progressive adaptability.

Through the early 1940s, Philo sank into

a depression. He told his wife

"that what he had accomplished

seemed all for naught, that he...wondered se-

riously if he had accomplished anything

at all."94 He was active in wartime

fundraising and the volunteer

chaplaincy,95 and he was at the peak of his es-

teem in the general Youngstown

community.96 But his religio-political syn-

thesis of progressivism and Judaism had

irretrievably collapsed, and it is

likely that his depression was a belated

recognition of that fact. His discour-

agement was even noted by the Vindicator

in a memorial editorial after

Philo's death in 1948. Despite his

disappointments, the editorial continued,

he was not dismayed, and kept "to

the end the conviction that the good in

human nature outweighs the bad."97

This conviction was by then in serious

disrepute among former progres-

sives. Writing in 1939, the Protestant

theologian Reinhold Niebuhr described

how world events of the previous decade

had provoked him to rethink com-

pletely his liberal theological and

social outlook. He realized, he wrote, that

faith in the goodness of human nature

and "the simple reinterpretation of the

Kingdom of God into the law of

progress" falsified the complexity of the

world. Liberal moralism, Niebuhr

charged, "does not know how to check evil

and historical injustice in politics,

because it would like to operate against in-

justice in terms of perfect moral

purity."98

Niebuhr's struggle would not have been

unfamiliar to the Reform rabbis.

During the 1930s, they were, as a group,

strongly pacifistic; this did not

change until a second World War was

imminent. In 1940, a prominent rabbi

commented, "As a former pacifist, I

have changed my point of view with a

great many others."99

In the 1930s, Philo indulged in exactly

the sort of moralizing attitude to

world affairs that Niebuhr criticized.

"The slogan 'Deutschland Ueber Alles,'

should make way for 'Freundschaft Ueber

Alles,'" he wrote in the Vindicator

in the early 1930s. "There is no

other basis on which to build an enduring

peace." On another occasion,

approving the cancellation of Germany's war

debts, he announced, "To make the

world our moral and spiritual rather than

our material debtor would hasten the day

of peace. The cost is small for so

94. Kendall, "Philo: A Biography,"

61.

95. Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 64.

96. "Dr. I.E. Philo Given Citation

for 'Distinguished Living,'" Youngstown Vindicator,

November 26, 1942.

97. Editorial, Youngstown Vindicator,

July 19, 1948.

98. "Ten Years That Shook My

World," Christian Century, 56 (April 26, 1939), 542-6.

99. Meyer, Response to Modernity, 313.

"Bull Moose" Rabbi

23

great a blessing."100 Even

in the late 1930s, in "A Rabbi's Easter Message,"

Philo prescribed moral and spiritual

uplift as the best response to Hitler:

"The only way to rid our world of

these malevolent influences is by more re-

ligion.... Because man is made in the

spiritual image and moral likeness of

God, he is dowered with power to think

God's thought after him, to be God-

like. Together, we of the church and

synagogue must build a human society

which will forever banish from the earth

atheism, paganism, injustice,

hate...."101

True to his Americanism, Philo

wholeheartedly supported the war effort

once the United States entered the

conflict. His Independence Day address in

1942 urged that "[t]he American way

of life must be made the way of life for

all people everywhere."102 But

he was no Niebuhr, grimly facing the appar-

ent fact of human depravity. The

rhetoric of Philo's World War II patriotism

sounded eerily like his rhetoric in

1918, when he declared, "America is in this

war because America is on the side of

God."103 That he had not really

changed is evident in his sympathy for

the American Council for Judaism.

The Council's ideologues feared, above

all, that Jewish nationalism would

eviscerate Judaism's universal spiritual

mission. These inveterate optimists

could not consider the prospect of

compromise with worldly realities for the

sake of Jewish survival. Even in the

short term of human history, they

would not surrender their messianic

faith that "perfect moral purity" could-

and would-save the Jewish people.

Indeed Philo was an unrepentant

progressive. If religion was love and hu-

man community the highest goal, religion

and community were failing. The

world in which Isador Philo had thrived,

and within which he searched for his

greatest satisfaction, was-beyond

question-gone. But he clung to it stub-

bornly. He still looked at the world

through a progressive's lens. During the

unprecedented challenges of the Great

Depression, he fought the old economic

battles in the old terminology:

"There is no more vicious paternalism in

America today than the Czarism of

private industrial power."104

In the

1930s, he described Judaism as itself

the paragon of progressivism: "Judaism

embodied the principle of evolution in

its prayer book many centuries ago and

the Talmud calls upon man to be a

co-worker with God in the task of bring-

ing to perfection the world He has made.

Human happiness and progress are

by-products of creative labor."105

In 1947, the year before his death, he gave

100. Writing as Straw Bored Green,

"News and Views," Youngstown Vindicator, [1930s]

(AJA).

101. "A Rabbi's Easter

Message," [Youngstown Vindicator?, late 1930's] (AJA).

102. "July Fourth, 1942," [Youngstown

Vindicator?, 1942] (AJA).

103. "The American Jew and the

War," 19.

104. Writing as Straw Bored Green,

"News and Views," Youngstown Vindicator, [1930s]

(AJA).

105. Quoted in Kendall,

"Intellectual Digest," 10.

24 OHIO HISTORY

a sermon on tolerance on the occasion of

his 50th anniversary in the rab-

binate. "Different ideals of life

[are] dependent to a large extent on environ-

ment," he told his audience,

"[and i]t is diversity of ideas that makes the world

progressive...." 106

From the end of World War I on, when he

was already forty-six years old,

Philo's rabbinic career was driven by

the need to find ways to express his

progressivism, to seek out a facsimile

of what Robert Crunden calls the

"climate of creativity" that

had been swept away by other cultural currents.

Philo was, in Crunden's words, a

"minister of Reform." Like

many

Protestant progressives, Philo replaced

revelation with democracy as the in-

strument for searching out truth. Also like many Protestant progressives,

Philo channelled his religious impulses

into secular avenues.107 Was it pos-

sible to be a progressive and a loyal

Jew? To be such, Philo's Judaism took

on the perfectionistic and

moralistic tones of Protestant

evangelicalism.

This he accomplished through a double

process of universalistic identifica-

tions.

When Judaism equals

Christianity, and Christianity equals

Americanism, then the transitive

is-Judaism equals Americanism!

Philo accomplished his ideological

purpose in a single paragraph of his

1918 sermon, "The American Jew and

the War." Like many progressives of

all backgrounds, and in a grand American

tradition, he identified America as

the metaphysical Jewish people. If the

Jews are Israel among the nations,

then, in Philo's words, "America is

the Israel of the nations." The American

spirit, he continued, "the spirit

in which this war was undertaken by America,

[is] the spirit which...speaks the ideal

embodied in the Statue of Liberty and

which is conveyed by the words of

Matthew: 'All ye that labor and are

heavy-laden, come unto me and I will

give you rest.'"108

In Philo's rhetoric, the

all-encompassing Statue of Liberty becomes the

Christ figure, the chosen nation, and

the culmination of humanity's in-

evitable progress. Just as Philo

believed that through Zionism, Judaism

could rescue nationalism, he was convinced that through Judaism and progres-

sivism, America could rescue the world.

His Reform Jewish universalist

faith nourished the messianic fervor of

his progressivism long after the secu-

lar manifestations of that messianism

were discredited.

Philo had a genuine passion for God,

truth, peace, brotherhood, and human

betterment. Just as genuine were his

conflicts, which came from trying to

reconcile an essentially Protestant

progressivism with his deeply-held, if lib-

erally interpreted, Judaism. Creating

himself as an American rabbi and

lawyer, largely with native gifts of

personality and an autodidact's determina-

106. "Tolerance," sermon given

at Temple Rodef Sholom of Youngstown, June 1947, quoted

in Kendall, "Philo: A

Biography," 66.

107. See Crunden, Ministers of

Reform.

108. "The American Jew and the

War," 18.

"Bull Moose" Rabbi 25

tion to prove himself, Isador Philo gave

Youngstown Jews someone to be

proud of for many decades. His

congregants could bask in the aura of his

public success and his acceptance by

Christian leaders. Though Philo's pow-

erful public presence kept his memory

alive for many decades, his message

seemed dated. Philo had constructed an

American Jewish persona which was

destabilized first by the failure of

perfect justice and of progressive politics,

and later by the practical failures of

prophetic, universalist humanism and re-

ligious liberalism. The dilemmas of

being an American Jew had not been

solved.

AMY HILL SHEVITZ

"Bull Moose" Rabbi: Judaism and

Progressivism in the Life of a

Reform Rabbi

"When he spoke," Mrs. R. told

me, "it was just like the voice of God."

This is how one of his congregants

described Rabbi Isador Philo almost

fifty years after his death. His

successor in the pulpit of Reform temple

Rodef Sholom in Youngstown, Ohio,

eulogized Philo in 1948 with similar

words: "He was blessed with a rich,

resonant voice and a keen analytical

mind...his entire dignified physical appearance

and spiritual bearing were

those of one who walks with God."

Philo himself would have been most

pleased with another turn of phrase from

his successor, who praised the late

rabbi's "prophet-like restlessness

as a soldier of the Almighty."l

What was it that made this man so

impressive that though he had only a

regional career, he is remembered by

many in his local community as such a

source of Jewish pride? Certainly

dramatic flair was part of his appeal-and

his slight British accent could not have

hurt.2 But when we peel away the

layers surrounding the local myth of

Isador Philo, we encounter the fascinat-

ing story of an immigrant boy who

literally created his persona out of an am-

bition to become the perfect American

Jew. Isador Philo's life and career

provide an excellent case study of the

complex interplay of personality, op-

portunity, social mores, and Jewish

values which comprise the process of

"Americanization." Especially

compelling is the fact that Philo, adapting

himself in a way specific to his era and

its values, shaped for himself an intel-

lectual synthesis which illumines a

critical aspect of the intersection of

Judaism and Americanism in the early

twentieth century.

Little can be verified about Philo's

family, childhood, and education. He

was born on July 24, 1873, in Cardiff,

Wales. His family had immigrated to

Great Britain from Breslau, Germany, not

much before Isador's birth, in the

Amy Hill Shevitz is Instructor in

American Jewish History at California State University,

Northridge, and the University of

Judaism (Los Angeles). A doctoral candidate in American

history at the University of Oklahoma,

she is writing her dissertation on the small Jewish com-

munities of the Ohio River Valley.

1. Obituary of Isador Philo by Sidney

Berkowitz, Central Conference of American Rabbis

[CCAR] Yearbook, 59 (1949), 251.

2. Irving Ozer, et al., These are the

Names: The History of the Jews of Greater Youngstown,

Ohio, 1865 to 1990 (Youngstown, 1994), 91.

(614) 297-2300