Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

|

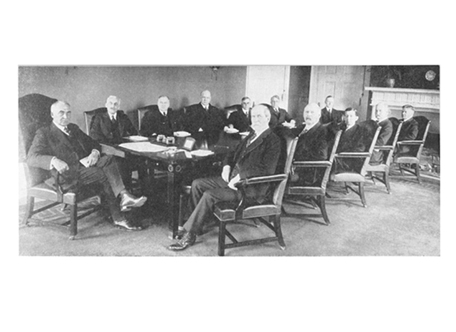

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET

by ROBERT K. MURRAY

Among the many controversial facets involving the life of the twenty-ninth president of the United States, few have prompted more conjecture and analysis than the choosing of his cabinet. The fact that one of his selections achieved the distinction of being the only cabinet officer to go to jail, that another resigned under a cloud of suspicion, and still a third narrowly missed criminal conviction, places Warren Gamaliel Harding in a unique position as a cabinet-maker. With this record it is little wonder that Harding's skill as a judge of men has been consistently downgraded both by historians and popular writers. Early observers, such as William Allen White, Frederick Lewis Allen, Mark Sullivan, and Samuel Hopkins Adams, all agreed that the Harding cabinet was a crazy quilt of both good and bad, with the bad far outweighing the good.1 Later writers, such as Frederick L. Paxson and Andrew Sinclair, soften the emphasis somewhat but basically arrive at the same conclusion.2 Thus, despite the recognized excellence of certain cabinet choices, the poor selections have captured the lion's share of popular and scholarly attention and have brought down upon the whole selection process a verdict of failure. But this verdict is based largely on the later scandals and not on the actual process of cabinet-making itself. Lost to view is Harding's personal wrestling with the alternative choices, the demands of the contemporary political situa- tion, and his own commitment to certain goals and principles. Until these factors are fully examined, the verdict of failure is at best incomplete and at worst erroneous.

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 185-188 |

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 109

With the taste of a stunning election

victory still in his mouth, President-

elect Warren Harding announced from the

front porch of his Marion, Ohio

home on November 5, 1920, that he

intended to leave the next day for a

month's vacation trip to Texas and

Panama, but that immediately upon his

return he would consult the "best

minds" of the country about his cabinet

and his future course of action. He warned

that all speculation in the interim

about cabinet selections would be

unfounded because he did not propose to

name anyone until he returned to Marion,

which he now dubbed "the Great

Listening Post."3

No sooner had Harding's special train

pointed southward than the press

was filled with intense speculation.

Each issue brought forth new names "on

the highest authority" or

eliminated old ones on the basis of the latest infor-

mation from "someone close to

Harding during the campaign." On the very

day Harding left, the New York Times contained

an editorial which prophe-

sied that Frank O. Lowden and General

Leonard Wood would be in the

cabinet.4 Others picked Senators Henry

Cabot Lodge and Harry S. New as

sure bets, while speculation for

Secretary of State centered around Charles

Evans Hughes, Elihu Root, or Senator

Philander C. Knox.5

Harding returned from Panama to

Washington on December 5. He was

aware of the newspaper comment and was

amused by most of it, but not by

the constant inference that the cabinet

would be packed with senators and,

indeed, that a "senate

oligarchy" would dictate the choices and set adminis-

tration policy. A hang-over from press

coverage of the Republican convention

and popularized by Democratic Governor

Cox during the campaign, this

charge of senate control was much on the

President-elect's mind when, on

December 5, the opening day of the third

session of the Sixty-sixth Congress,

he delivered a brief farewell address to

his senate colleagues. Expressing his

regret at leaving, he added this

interesting declaration:

Something has been said about the

"Senatorial oligarchy." Of course

everyone here knows that to be a bit of

highly imaginative and harmless

fiction...When my responsibilities begin

in the executive capacity, I

shall be as mindful of the Senate's

responsibilities as I have been jealous

for them as a member; but I mean at the

same time to be just as insistent

about the responsibilities of the

executive. Our governmental good

fortune does not lie in any surrender at

either end of the Avenue.6

Harding came into the presidential

office under obligation to no one. True,

he owed his Ohio supporters and a few

close friends, such as Harry M.

Daugherty, a debt of gratitude, but he

had received the nomination and

achieved final victory without

"deals" or promises. This gave him a freer

hand in selecting his official family

than most presidents have enjoyed.

He avowedly set out to acquire an

independent-minded, first-class cabinet.

His hope was to attract equals and not

echoes or rubber stamps. He hoped

to follow the tradition of Washington

and Lincoln in this respect, and not

Wilson. But he recognized there were,

necessarily, some restraints. Said he

to reporters, when lecturing them once

on the problems of cabinet-making:

Three things are to be considered in the

selection of a Cabinet. First,

there is the man's qualification for

public service. That is the most

110 OHIO HISTORY

important consideration of all. Second,

there is the attitude of the public

concerning the man under consideration.

Third, there is the political

consideration. As to that--well. This is

going to be a Republican

Cabinet.7

Despite having certain definite views on

cabinet selections, Harding was

no dictator. Indeed his political career

had been based on the adjudication

of differences and compromise. Always

attracted to party solidarity and a

firm believer in collective party

wisdom, Harding by choice, and not by force,

elected to consult widely -- the

"best minds" -- before making final decisions.

As a result, never had there been such a

pilgrimage of the party faithful

to a president-elect as occurred at

Marion, "the Great Listening Post," after

December 10. For the next month, as high

as six or seven leaders per day

funnelled through Harding's makeshift

office, being asked and giving advice

on a variety of matters, including

cabinet selections. No shade of opinion

was excluded. Once, when it came to

Harding's attention that Republican

house members were disgruntled because

of the preponderance of senators,

he ordered Will Hays, who was in charge

of the invitations, to include more

congressmen. Indeed, Hays found his

guest list constantly expanding as one

after another of the party's leaders

were requested to appear at Marion.8

At the same time, Harding consulted and

relied on "unofficial" representa-

tives in the field who reported to him,

especially on matters relating to the

cabinet. From time to time he gave them

specific assignments, and they

always sent their impressions directly

to him. The five most important of

these men were Harry M. Daugherty,

Charles D. Hilles, Senator Joseph

Frelinghuysen, Senator Harry S. New, and

Senator Frank Brandegee.9 Hard-

ing also sought the independent advice

of his running mate, Calvin Coolidge,

but Coolidge's cold personality made his

effectiveness minimal. Having made

a campaign promise that if elected he

would break precedent by bringing

the vice-president into cabinet

meetings, Harding believed it wise to consult

with him on cabinet choices. There is no

evidence, however, that Coolidge

ever played a significant role. In fact,

Brandegee took such a dim view of

Coolidge's contributions and talents in

general that he once wrote Harding:

"None of us here think much of the

idea of making the V.P. a Cabinet

officer 'Emeritus.'"10

There is no question that Harding was

the focal point of all discussions

on cabinet selections and was always in

command. The reins of decision he

held tightly in his own hands. He

rapidly became discouraged, however, by

the lack of advisory unity he discovered

among the "best minds." Worse,

he found himself suddenly the vortex of

subtle intrigues and cabals designed

to sway him one way or another. He soon

learned that the "big men" he

wanted for his cabinet also possessed

"big enemies" and that political con-

siderations often were used to cancel

out superior qualifications. Once, in the

midst of discouragement, he wrote to his

Ohio friend, Malcolm Jennings:

"What a job I have taken over. The

man who has a Cabinet to create has

one tremendous task."11 To

another friend he confided, "My cup is full."12

And the agony that he suffered he never

wholly forgot. Later when seeking

presidential clearance for an essay about

the Administration for the Saturday

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 111

Evening Post, H. H. Kohlsaat wrote Harding: "I did not think it

wise to use

any of the stories you have told me of

your Cabinet making -- it might

embarrass." The President

wholeheartedly agreed.13

Despite his inner turmoil, Harding

weathered the ordeal of selecting a

cabinet quite well. Insiders were amazed

at his patience and tact, his cor-

diality and sincerity. William Howard

Taft came away from his Marion

interview convinced that Harding was

trying to "do the right thing," and

Nicholas Murray Butler left with a solid

impression of "his good judgment

and sound common sense." Butler's

talks with Harding convinced the Co-

lumbia University president that the

Ohioan possessed a "perfect familiarity

with the various troublesome elements in

his political party."14

The marathon discussions, confusing as

they were, soon convinced Hard-

ing of several things: the Secretary of

State had to be a man universally

respected by the country yet able to

work with all elements in Congress;

the Secretary of Agriculture should be a

practical farmer and not merely a

professor of farming or an agricultural

lobbyist; the Labor post should go to

someone identified with labor, possibly

a union member, but not of the

"radical element;" and the

Treasury position should be filled from the Middle

West and not from New York or the

Northeast. Harding was also convinced

that one, if not two, positions in the

cabinet should be reserved for his

friends -- men to whom he could turn for

personal advice and whose loyalty

he could absolutely trust.15

These convictions provided the basic

framework for Harding's subsequent

cabinet-making and were reflected almost

immediately by his action in filling

the first position -- that of Secretary

of State. Much foolishness has been

written about this appointment. White,

Sullivan, and Adams all contend

that Harding really wanted to give the

post to his friend, Albert B. Fall,

but that visitors to Marion shook him

out of this notion with their sharp

opposition. It was claimed that he next

considered George Harvey and finally

turned to Root before deciding on

Hughes.16

There is little question that Harding

wanted Fall in the cabinet, but there

is no indication in any of Harding's

correspondence that he ever seriously

pushed Fall as Secretary of State. The

truth is that Harding offered the

position to Hughes on December 10 when

the New Yorker appeared in

Marion as one of his first visitors.

Three days later, Hughes wrote

Harding that he had talked the matter

over with his partners and "was glad

to say that I have arranged to be free

to assume the responsibilities of which

you spoke."17 On

December 22, Harding replied that he was "delighted" with

Hughes's decision and regarded the

matter closed. They both agreed that no

announcement would be made until later.

Such an announcement -- the first

regarding a cabinet selection -- was

made on February 19, 1921.18

In the meantime, ignorant of this

decision, the press continued its specula-

tion while the politicians argued.

Anti-League Republicans, such as William

E. Borah, championed the cause of Senator

Knox. Senator Brandegee, another

"bitter-ender," contended that

if Harding could not appoint Knox, he should

at least nominate Lodge.19 A

few, such as Senator James W. Wadsworth,

112 OHIO HISTORY

Jr., and Charles Hilles of New York,

clamored for the selection of Root;

and, when Harding invited Root to come

to Marion in mid-December, specu-

lation soared that he was about to be

chosen.20 Since no offer to Root was

apparently forthcoming, press interest

shifted back again to Hughes. At the

same time, the Old Guard, frightened by

increasing rumors of Hughes's

appointment, quickly closed ranks behind

Root even though they still wanted

Knox. Senator Boies Penrose made an

eleventh-hour fight in late January in

a futile attempt to block Hughes's

selection by dangling Root before Hard-

ing's eyes.21

But Harding, as noted, had already made

his decision back in early

December and he stuck with it. Moreover,

it was his decision and Hughes

was his choice -- his first choice.

It was a fearless act of cabinet-making

statesmanship.22

Another early decision which stemmed

from a strong Harding conviction

was the appointment of Henry C. Wallace

(father of Henry A. Wallace) as

Secretary of Agriculture. He felt

Wallace fulfilled the requirement that the

holder of this post should be a

"dirt" farmer. During the campaign, he and

Cox had jousted verbally over this

matter, with Harding charging that the

Wilson Administration had appointed only

university presidents and pub-

lishers to the position while the

Republican party traditionally had selected

bona fide farmers.23 By a

curious twisting of the definition, Harding classified

Wallace as a "dirt" farmer;

but in so doing he did violence to the truth. Born

into a farming family in Adair County,

Iowa, Wallace, after attempting farm-

ing for five years, ultimately found

more interest in teaching -- he was for a

time an assistant professor at Iowa

State -- and in farm journalism than

in plowing.

Wallace had been invaluable to Harding

during the campaign. One of the

best known agriculturalists in the

United States because of his editorship

of Wallaces' Farmer, he had

helped write the 1920 Republican farm plank

and had been Harding's chief advisor and

speech writer on farm matters.

Wallace, himself, was an able stump speaker;

and his slashing attacks on

the Wilson Administration, together with

his personal influence among

agricultural organizations, were

important factors in swinging a massive

farm vote to Harding.24

Even before the election, Harding had

his eye on Wallace as a potential

Secretary of Agriculture. On November 1,

1920, Harding wrote to Wallace:

"If the verdict on Tuesday is what

we are expecting it to be I shall very

much want your assistance in making good

the promises which we have made

to the American people."25 After

the election, when other names were brought

forward as candidates, such as Senator

Arthur Capper and Marion Butler,

Harding barely gave them consideration.

Wallace was still his man even

though press speculation did not center

on the Iowan until late December.

By that time, Harding was subjected to

extreme pressure regarding the

Wallace selection. Some conservative

leaders and certain vested interest

groups objected strongly. Wallace's liberal

tendencies unsettled Old Guard

members while his editorial assaults

against the malpractices of the packing

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 113

and food processing industries earned

him the hatred of these powerful

elements. Delegations, headed by no less

than Everett C. Brown of the

National Live Stock Association and C.

B. Stafford, President of the Chicago

Live Stock Exchange, hastened to Marion

to protest his nomination. The

packers and millers also had their

spokesmen present. But Harding did not

waver, and Wallace joined Hughes on the

cabinet list.26

The Hughes and Wallace appointments were

not to the liking of the

President-elect's senate cronies or

close political friends. This was all the

more true of still a third selection --

Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Com-

merce.

It is clear from the Harding

correspondence that from the very beginning

he was attracted to Hoover as a cabinet

candidate. It is equally clear that

certain elements in the party, close to

Harding, lived in constant fear that

Hoover might be selected. From the day

that Hoover arrived in Marion

(December 12) to confer with Harding, a

bitter campaign was conducted to

keep Hoover out of the cabinet. On the

other hand, Hoover, even more than

Hughes, had a "good press,"

and there was wide support in the country at

large for his appointment.27

The opposition to Hoover was both

impressive and articulate. Frank

Brandegee stated the anti-Hoover

position succintly: "Hoover gives most

of us gooseflesh."28 Too

liberal in his social philosophy, too internationally-

minded, too popular, and too ambitious

for the Old Guard, Hoover was not

opposed for a particular cabinet

post, but for any. Senators Philander Knox,

Charles Curtis, and Reed Smoot voiced

immediate opposition, and warned

Harding that Hoover was non-party

oriented and would not "get along well"

with other cabinet officers.29 Not

only the Old Guard, but even Insurgent

senators, such as Hiram Johnson, were

skeptical. Harry New, one of Hard-

ing's "trouble-shooters" on

cabinet appointments, wrote to Marion shortly

before Christmas: "Many senators

have expressed the hope that Hoover

may be omitted. [They] fear the effect

of this [selection] in the Senate ...

[Johnson] says it [Hoover's nomination]

would be personally so offensive

to him that he hoped from that

standpoint that it might not be found neces-

sary."30 Harry Daugherty

reported essentially the same information: that

there was little support for Hoover

among congressmen, that the Hearst

papers were against him, and that even such

Progressives as Raymond

Robins, Gifford Pinchot, and George W.

Norris did not endorse him.31

Indeed, there was little

enthusiasm for Hoover in the Republican party

leadership. Among Harding's close

advisers, only Frelinghuysen supported

Hoover's appointment as

"politically wise" and believed him superior to other

suggested candidates, such as Albert

Lasker of Chicago and Eugene Meyer,

Jr., of New York City.32

Harding's attitude toward Hoover

remained unshaken throughout this

debate. On January 12, 1921, in reply to

a letter from Hoover in which the

humanitarian had strongly endorsed

Wallace's appointment as Secretary of

Agriculture, Harding wrote: "Your

opinion concerning [Wallace] is important

to me. Indeed, I hold you in such esteem

that your opinion on any matter

114 OHIO HISTORY

is of real importance."33 Under

the fierce attacks, "such esteem" grew even

stronger. On February 9, Harding wrote

Daugherty: "The more I consider

[Hoover] the more do I come to think

well of him. Of course, I have no

quarrel with those who do not think as I

do, but inasmuch as I have the

responsibility to assume, I think my

judgment must be trusted in the matter.

The main thing to consider at the present

is whether Mr. Hoover will accept

the post which I am prepared to offer to

him."34

Several days later on February 12,

Harding offered him the post of Secre-

tary of Commerce. The precise position

was really immaterial to Harding;

he simply wanted Hoover in the cabinet.

Hoover, on the other hand, was not

so anxious. On December 22 he had

already indicated to Harding (in rela-

tion to overtures about a cabinet

position made by Harding at their meeting

in Marion on December 12) that he did

not desire to enter public service,

and had requested the Ohioan to

"dismiss from your mind all thought of

my appointment."35 In view of

certain subsequent opposition, Hoover was

even less inclined to accept. Hence, considerable

persuasion was necessary.

At this point Harding asked Hughes to

intercede, and the New Yorker invited

Hoover to his Sixty-fourth Street

apartment to talk matters over.36 Will

Hays was also sent by Harding to

convince Hoover of the wisdom of entering

the cabinet. On February 22, in a phone

call from St. Augustine, where he

sought some relaxation prior to his

inauguration, Harding, himself, reaffirmed

to Hoover his deep desire to have him

join his official family and assured him

that he could have free rein in running

the Commerce Department if he

accepted.* In a final show of

determination, Harding wrote Hiram Johnson

a personal note acknowledging the

Senator's bitter opposition to Hoover,

but indicated that he believed Johnson's

fellow Californian would be an

excellent choice and requested Johnson

"to accept my judgment on this

particular matter."37 In

the face of such sincerity, Hoover wavered and the

next day, February 23, wired Harding

that although he much preferred to

remain out of public life, "I have

no right to refuse your wish and I will

accept the Secretaryship of

Commerce." Formal announcement was made

to the press a day later.38

Hoover's appointment as Secretary of

Commerce was intimately connected

with that of Andrew W. Mellon as

Secretary of Treasury. Contrary to later

assertions, Harding, in this instance,

not only displayed his independence but

also his political shrewdness. Mellon

was not Harding's first choice for the

Treasury post. Indeed, his name was not even

mentioned among the early

candidates: John Weeks (Massachusetts),

Charles Dawes (Illinois), Frank

Lowden (Illinois), and Charles Hilles

(New York). Of these men, Dawes

was Harding's favorite. During his visit

to Marion in mid-December, the

Chicago banker was asked by Harding if

he could be enticed into the cabinet,

and Dawes replied probably not, but no

final decisions were reached one

way or the other.39 Dawes

possessed some attractive advantages: the Chicago

and the Midwestern banking fraternity

strongly endorsed him; he was re-

nowned for his tenacity and ability to

effect efficiency and economy; and he

was fearless, frank, and unpledged to

any particular faction in the party.

* Harding granted a similar freedom to

and demonstrated an equally cooperative attitude

toward Henry C. Wallace, Secretary of

Agriculture. See "Disharmony in the Harding

Cabinet" below, pp. 126-136.

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 115

But many in the East did not like Dawes,

considering him too erratic for

their tastes. Temporarily these elements

united behind John W. Weeks as

their candidate and urged his selection

on Harding. The Ohioan, however,

was not impressed by eastern arguments

against Dawes and, further, indi-

cated that he did not wish the post to

go to a New Englander or a New

Yorker because of "Wall

Street" connotations. As late as Christmas, Harding

still inclined toward the Chicagoan,

despite eastern opposition.40

The first mention of Mellon was made by

Senator Knox. Mellon had been a

heavy campaign contributor and had close

contacts with the party leader-

ship through Senators Knox and Penrose.

Once, in early December, while

Harding was wrestling with the Treasury

problem and weighing the pros and

cons of the Midwest versus the East,

Knox remarked that if he wanted a neat

geographic solution as well as experience

and competency in the job, Pennsyl-

vania could provide the Pittsburgh

multi-millionaire. It was agreed that Mel-

lon should be invited to Marion for a

talk.41

A short time later, Knox happened to be

lunching with Mellon and Henry C.

Frick, and he indicated to Mellon that

his name had been mentioned in

connection with the Treasury post.

Mellon said he absolutely did not want it,

but both Frick and Knox urged him to go

to Marion and consider it if an

offer were made. But no direct offer was

made. Mellon journeyed to Marion,

had lunch with Harding, and chatted for

about an hour. Harding did mention

the Treasury position and inquired if

Mellon were interested. The financier

did not give a flat "no," but

he did remind Harding of his vast holdings and

the impropriety of making such a wealthy

man Secretary of the Treasury.

Harding asked him to keep the matter

open.42

The President-elect still wanted Dawes

as the Treasury Secretary but

was forced to recognize the logic of a

Mellon appointment. Besides, the

Pennsylvanian rapidly garnered the

support of both eastern and midwestern

banking elements, as well as the heavy

endorsement of Old Guard stalwarts.

Senators Knox and Penrose,

Pennsylvania's Governor William Sproul, offi-

cials of the Carnegie Institute, and

innumerable others attested to his "un-

excelled judgment and ability in matters

of finance." Charles H. Sabin,

President of Guaranty Trust of New York,

indicated solid eastern support

by writing Harding that "no wiser choice

could be made." Meanwhile,

Daugherty's soundings in the field were

likewise enthusiastic.43

This turn of events presented Harding

with an unexpected opportunity.

He was in the midst of fighting off the

bitter attacks on Hoover and badly

needed something to assure Hoover's

confirmation if that selection were

made. At the same time, he was juggling

simultaneously his preference for

Dawes and a desire to placate certain

members of the Old Guard, including

the eastern money

"establishment." In late January at St. Augustine, Hard-

ing met a second time with Dawes and

explained this complex situation to

him. Dawes stated again that he really

did not want the Treasury post and

indicated his own willingness to endorse

Mellon. Harding then requested

that Dawes not let it be known that he

was withdrawing his name from

consideration because the President-elect wanted to

outflank Penrose, Knox,

116 OHIO HISTORY

and others who were bitterly opposed to

Hoover. Harding told Dawes that he

intended to make Mellon Secretary of the

Treasury in exchange for Hoover

for Commerce. Shortly thereafter,

Harding sent Daugherty to Washington to

indicate to Senators Knox and Penrose

that Mellon was a possibility, but

only if their attacks on Hoover ceased.

Reluctantly, they agreed -- and Mel-

lon was appointed.44

In his talk with Dawes, Harding had

commented: "Mellon probably has

too much money for a Secretary of the

Treasury. I may get as much criticism

over his appointment as I would if I put

J. P. Morgan in that place."45 He

almost did, but Harding was fully aware

of what he was doing and was pre-

pared to live with it. Mellon was not so

sure about himself. The multi-

millionaire did not relish the personal

sacrifices he would have to make or

the criticism he would have to endure.

At the same time, encouraged by

Senator Knox, Mellon was intrigued by

the thought of entering the strange

world of politics. As Mellon, himself,

later described his ambivalent feelings:

"I really didn't want to come to

Washington [but] I did not want absolutely

to refuse."46 He finally

capitulated, and an announcement was made to the

press in the last week in February.

The financier's appointment was a

curious blend of politics, chance, wisdom,

and clever calculation. It was shrewd

cabinet-making at its best. In the end,

everyone won -- the Old Guard, both

midwestern and eastern banking in-

terests, Hoover and Hoover supporters,

and most of all, Harding. Not every

President could boast that one of the

wealthiest men in the world was in his

cabinet. Bernard Baruch once remarked to

Clarence W. Barron, publisher

of the Wall Street Journal, that

when he had refused in 1912 to take the

Treasury position, President Wilson had

protested with tears in his eyes:

"I have no objection to

wealth." Obviously, neither had President-elect

Harding.47

While these four cabinet selections were

based, to a large extent, on

Harding's own desires as well as the

superior qualifications of the candidates,

four other appointments represented the

normal surrender to simple political

expediency. In these cases, the

President-elect merely followed the advice of

his political advisers or the dictates

of party necessity. Immediately after

the election, there was press

speculation that both General Leonard Wood

and Frank O. Lowden, the main contenders

for the Republican nomination

in 1920, would find their way into the

Harding cabinet. Although the election

result demonstrated that there was no

great need to sacrifice cabinet positions

to the Wood faction, Harding and his

advisers were nevertheless aware of

the General's personal popularity and

newspaper support. The "Great Listen-

ing Post" was bombarded by requests

that Wood be made Secretary of War

in order to "salve his

disappointment" over losing the nomination. In a

Literary Digest poll, two hundred forty-two of three hundred Republican

editors endorsed him for this cabinet

position.48

Within Harding's advisory circle there

was considerable opposition to the

General. The charge was made that Wood's

appointment would disrupt the

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 117

Army and cause intense internal friction

because of his controversial career

as a professional soldier. Moreover, it

did not seem wise to have him pass

on the promotions of senior officers

under whom he had served or with whom

he had been in school. Some of Harding's

advisers were opposed to Wood

because of his popular appeal and the

fear of his future ambitions. Besides,

old wounds still remained from the

pre-convention campaign fight in Ohio

in which the General's forces had taken

several favorite-son votes away from

Harding. Also damaging was the fact that

Wood had not worked enthusiastic-

ally for Harding during the campaign.

Interestingly enough, Harding found

less validity in most of these reasons

than did his advisers, but agreed that

political necessity precluded Wood's

appointment. He expressed the hope,

however, of using Wood's talents

elsewhere and later appointed him governor-

general of the Phillipines.49

Political and geographic requirements

pointed ultimately to John W. Weeks

of Massachusetts for the War cabinet

post. An early contender for the post

of Secretary of the Treasury, he had

been supported by New England banking

interests. Senator Lodge was one of his

primary backers and relinquished his

drive to place him in the Treasury

position only after receiving assurance

that Weeks would secure a slot

"somewhere" in the cabinet. At one time or

other, he was considered for Postmaster

General and Secretary of the Navy.50

His credentials for both these latter

positions were rather impressive.

Weeks had been a member of the House

from 1905 to 1913 and then had

served six years in the Senate. While in

the House, he had been chairman of

the Committee on Post Office and Post

Roads; in the Senate, he had been

a member of the Military Affairs

Committee. In addition, Weeks had a naval

record. In 1877, at age seventeen, he

had enlisted as a cadet midshipman

and, four years later, graduated from

the Naval Academy. He served in the

regular Navy for two years and was

honorably discharged. During the

Spanish-American War he again donned his

naval uniform, signing on as a

lieutenant for the duration.51

Thereafter, he returned to Boston and to his

banking business, which expanded so

rapidly that it made him one of the

major bankers in the New England area by

World War I. His defeat for

reelection to the Senate in November 1918

was a surprise to the Republicans,

especially to some of his close Senate

friends, such as Lodge. But Weeks

continued his political service in other

ways -- along with Mellon, he was

one of the chief financiers of the

Republican campaign of 1920.

Harding and Weeks had been friends in

the Senate, and Harding was more

than willing to have him represent the

Northeast in the cabinet. The logical

place seemed to be Secretary of the

Navy. But through friends, Weeks re-

vealed that he did not want the Navy

position for the same reasons which

were being discussed against General

Wood for War: it would not be wise

for him to pass on the qualifications

and promotions of those with whom he

had served or attended school. Just

prior to Christmas, therefore, feelers

were extended from Marion as to whether

Weeks would accept the post of

Secretary of War. The Boston banker then

contacted his Senate friend,

118 OHIO HISTORY

Harry New, currently serving on the

Senate Military Affairs Committee, and

asked him if he should take War if

offered. New replied: "absolutely" -- and

quickly wrote Harding that he was

confident Weeks would accept the War

post.52

On January 15, 1921, Weeks was summoned

to Marion to talk with Hard-

ing, and, as the New York Times phrased

it, "cabinet matters were brought

up."53 Rumors circulated that Weeks had

been tapped for Secretary of War

because, by now, it was an open secret

that he had an aversion to the Navy

post. But more than a month elapsed

before Harding made an official an-

nouncement to the press. The reason for

the delay was not because of any

latent opposition on the part of

Harding, or anyone else, but simply because

he wished to wait until announcements

could be made about other cabinet

choices as well. Indeed, Weeks's

appointment was a popular one with the

party and also with the military.

Senator Wadsworth, chairman of the Senate

Military Affairs Committee, wrote to

Harding just after the decision had

been made: "I would like a dollar

for every Army officer and every member

of Congress who during the last two

months has expressed the hope that

Weeks could put his hand to this great

big task."54

The job of Secretary of Labor posed a

particularly thorny political problem.

Continuing labor disturbances in the

immediate postwar period focused

unusual attention on government-labor

relations, and the Republicans were

anxious to placate the rank and file of

labor if possible. The strategy in

selecting a person to head Labor had

already been outlined by Harry L.

Fidler, special labor affairs

representative of the Republican National Com-

mittee, in a lengthy twelve-page letter

to Chairman Will Hays on November

24, 1920. Fidler, who was a staunch

Republican and a member of the Brother-

hood of Locomotive Engineers, pointed

out the fact that the whole Gompers

clique in the American Federation of

Labor had fought Harding in the cam-

paign and that it would be a mistake to

reward them in any way. But,

warned Fidler, while the Secretary of

Labor "must be an anti-Gompers

man ... he must also be a practical

labor man." Fidler may have hoped that

the lightning would strike him, and Hays

did later mention his name for the

post. Fidler, however, was never

seriously considered for Secretary of Labor,

although his recommended course of

action was endorsed.55

Among the persons most mentioned for the

position were James Duncan,

William L. Hutcheson, T. V. O'Connor,

and James J. Davis. Head of the

Stone-Cutters' Union and a

vice-president in the A. F. of L., James Duncan

was Gompers' personal candidate who,

interestingly enough, was also sup-

ported by Lodge -- Duncan was from

Massachusetts. Despite Lodge's bless-

ing, Gompers' support proved the kiss of

death.56 Hutcheson, as General

President of the Brotherhood of

Carpenters and Joiners, possessed con-

siderable rank and file labor support

but had no one in the Republican party

leadership strongly pushing him.57

T. V. O'Connor, however, was another

matter. As president of the Interna-

tional Longshoremen's Association, he

was vigorously championed by strong

elements in organized labor. He also had

the backing of numerous New York

businessmen as well as the support of

Nicholas Murray Butler. Originally

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 119

O'Connor had been a Democrat, but had

bolted that party because of Presi-

dent Wilson's postwar labor policy.

Moreover, he was solidly anti-Gompers,

a "conservative," and had

voted for Harding in 1920. But his earlier advocacy

of the closed shop and low tariffs had

created suspicion. And when Harding

requested that Charles Hilles check into

the record, he received some highly

adverse reports.58

Meanwhile, attention for the Labor

Secretary shifted to James Davis.

While Davis thought of himself as a

laboring man and had been an iron

"puddler" and an active union

member, he had long since become better

known for his lodge work.

Director-General of the Loyal Order of Moose and

one of the founders of Mooseheart (a

city of fatherless children in the Fox

River Valley, thirty-seven miles west of

Chicago), he was sometimes called

the "Napoleon of Fraternity"

and allegedly could call ten thousand men by

their first names.59 This

ability was a decided political asset as hundreds of

Moose lodges sent their endorsements of

"Puddler Jim" Davis to Marion.

When support also came from such labor

organizations as the Street Carmen's

Union and the Iron Moulders' Union,

Davis seemingly possessed an unbeat-

able combination -- especially since he

was also anti-Gompers, a hard-working

Republican party member, and had been a

staunch backer of Harding in

1920.60

The decision regarding the Labor post

was allowed to simmer until after

the Christmas holidays, while more

pressing cabinet business was settled.

Then, on January 7, Harding telegraphed

Davis to come to Marion to discuss

the "labor policy" of the new

Administration. Three days later he offered

Davis the position and Davis accepted.61

No announcement was made, how-

ever, and therefore press and labor

speculation continued regarding the

ultimate selection.

Sensing a decline in interest at Marion

in other potential candidates after

the Davis interview, many labor leaders

voiced concern over the possible

appointment of Davis. Indeed, the

various proponents of O'Connor, Hutche-

son, and Duncan joined forces after

mid-January to oppose Davis and threw

their combined weight behind O'Connor.

They did not consider Davis enough

labor-oriented to hold the post and

feared that his interest lay more in

Mooseheart than in the shops and mines.

In a last minute effort, without

mentioning names, Gompers sent a lengthy

telegram to Harding on February

7 stating that "no man is fully

capable to fill the position of Secretary of

Labor who lacks the sympathy, respect

and confidence of the wage workers

of our country."62

If Harding needed a reason to re-enforce

his earlier decision to appoint

Davis, Gompers' antipathy provided it.

Davis's selection was purely political

and designed to offset the various

forces within the laboring groups, while

at the same time denying control of the

office to Gompers. As Senator

Wadsworth later recalled: "The

appointment was regarded as suitable. I do

not think any of us had the idea that

the appointee was a great statesman."63

Of the final two political appointments,

the selection of the Postmaster

General was the easier. While a number

of candidates existed, there was

never any doubt that Will Hays, chairman

of the Republican National Com-

120 OHIO HISTORY

mittee, could claim it if he wished.

This action was traditional. Strangely

enough, Hays did not relish the thought

of supervising the nation's mail and

really preferred the Commerce post. But,

Harding made it clear that the

latter position was beyond his reach (it

had already been reserved for

Hoover), and on January 17 he gave Hays

his choice either of the Post

Office or chairman of the Commission to

Reorganize the Government. Three

weeks later, after weighing the various

possibilities, Hays told Harding that

he would accept the cabinet job.64

The selection of Secretary of the Navy

was almost an afterthought and

came at the very end of the wearisome

process of cabinet-making. After

ex-senator Weeks dropped out of the

running for the post in late December,

it was decided to offer it to Frank

Lowden. Unlike their feeling toward the

Wood element, Harding's advisers expressed

a belated desire to reward the

Lowden faction and Lowden, himself, for

supporting Harding during the

campaign. When, on January 17, Lowden

received an invitation from Hard-

ing to join his official family as

Secretary of the Navy, he was surprised.

Frankly, he had nursed a hope of

becoming either Secretary of Treasury or

Secretary of Agriculture and felt

qualified to hold either post. But he hardly

knew the bow of a battleship from the

stem. Hence, after some soul-searching,

he telegraphed Harding his refusal. But

Harding persisted and reaffirmed

the offer not simply as a courtesy, but

because of a genuine desire for him to

enter the cabinet. When Lowden again

demurred, Harding attempted a third

time to get him to reconsider. Harding's

last telegram of February 14 read:

"I think a great public approval

awaits your acceptance. If you insist once

more on the impossibility, I will accept

its finality."65 Lowden insisted;

another candidate had to be found.

Edwin L. Denby's name had first been

mentioned to Harding by Weeks

at the time the latter had expressed his

preference for War rather than

Navy. Lowden had also mentioned Denby

during his series of refusals of

the Navy position.66 Almost

in desperation, Harding then turned in Denby's

direction, too.

Actually, on the basis of apparent

qualifications and availability, Denby

was an excellent choice. He had served

as a gunner's mate in the Spanish-

American War; and in 1917, although

forty-seven years old had dropped a

civilian law practice and enlisted as a

private in the Marines and was dis-

charged as a major at the end of War I.

Previously he had served six years

in Congress where, among other

assignments, he had been a member of the

House Naval Affairs Committee. Although

a "Big Navy" man, he was

regarded as being too conservative by

followers of Theodore Roosevelt and

lost his seat in the election of 1910. After World War

I he returned to Detroit

and made a fortune manufacturing automobiles.

In the pre-convention days

of 1920, he had been a Lowden man, but

worked diligently for Harding in

the regular election.67

On Washington's birthday, February 22,

Harding offered him the Navy

post. Denby could not have been more amazed. Said he:

"The invitation

took me off my feet. I was

overwhelmed." Certainly he was no less surprised

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 121

than the press. Reporters at St.

Augustine greeted the announcement of his

acceptance with: "Denby, Denby --

who is Denby?"68

Much mystery and drama has been written

into the relatively simple story

of Harding's selection of two of his

personal friends for cabinet positions.

His friendship for Albert Fall and his

friendship and gratitude to Harry

Daugherty gave them both a high priority

on his list of available candidates.

In the case of Fall, Harding simply

liked him. He was not alone. Fall had

an attractive personality. Born in

Frankfort, Kentucky in 1861, Fall had

worked in a cotton mill in Nashville

when he was only eleven years old;

at eighteen, he had studied enough law

to become a lawyer. Shortly thereafter

he set out for the Red River country and

for three years was a United States

marshal in the Panhandle area. Turning

next to prospecting in Mexico, he

worked the region around Zacatecas as a

mucker, ore sorter, and drill

sharpener. The year 1885 found him back

in the United States digging for

riches in the mountains of New Mexico.

During the Spanish-American War

he rode with Roosevelt and the Rough

Riders, and finally settled down in

Las Cruces, where he served in the

legislature of New Mexico territory for

three terms. He was elected to the New

Mexico Senate in 1902 and then to

the United States Senate in 1912. There,

wearing his broad-rimmed Stetson,

flowing black cape, and handle-bar

mustaches, he occupied an adjoining seat

to Senator Harding and became a

poker-playing crony of the future president

of the United States.69

But friendship was not the sole factor

in Fall's selection. Harding had

respect for his ability. So did others.

Fall was considered an expert on western

matters and also on Mexican and South

American affairs. He wrote the

Mexican plank into the 1920 Republican

platform. He had served on the

Senate Foreign Relations Committee with

Harding and had been a strong

opponent of Wilson's League of Nations.

A ruthless gut-fighter, Fall was at

his best in the kind of give-and-take

political debate which automatically

endears a politician to party stalwarts.

Harding wanted Fall in the cabinet and

mentioned him casually in con-

nection with a number of positions. Yet,

he apparently considered him

seriously only for Secretary of the

Interior, and even then only after it

became clear that Hoover wanted Commerce

and not the Interior post. For

Harding, it was a marriage of his desire

with geography and expediency

rather than with any need for dispensing

spoils. Fall was from the West and

the Interior post generally went to a

westerner, just as Agriculture tradi-

tionally went to a midwesterner. That

Fall was basically anti-conservation in

his views evidently did not play a part

in Harding's calculations. Fall, in

turn, did not know definitely until late

January that he was to become

Secretary of Interior; hence later talk

of this appointment being the con-

summation of "deals" made with

oil interests at the 1920 nominating con-

vention is so much nonsense. His

appointment was the last to be officially

announced -- March 1.70

At no time was there any opposition to

Fall on ethical grounds. Indeed,

he was regarded as so far above

suspicion that on March 4 the Senate did

122 OHIO HISTORY

not even send his nomination to

committee but confirmed him by acclama-

tion, an honor never before granted to a

cabinet member. A few rabid conser-

vationists, such as Gifford Pinchot,

maintained a drum-fire of opposition to

the rumored Fall appointment during the

month of February, but they were

in a very small minority.71 From

virtually every point of view, the appoint-

ment was a perfectly logical one. As

Albert Shaw, editor of the Review of

Reviews, commented in 1933; "The Senator from New Mexico

was recom-

mended for a cabinet place by almost

every public man in Washington . . .

His appointment was made by Mr. Harding in

entire good faith."72

The selection of Harry Daugherty as

Attorney General, on the other hand,

was unquestionably the most

controversial appointment made by Harding.

From the Harding correspondence, it

becomes evident that Harding and

Daugherty were not "buddies"

in any sense of the term. They were friends,

but not to the exclusion of others.

Daugherty was not one of Harding's close

golfing or poker-playing companions.

Theirs was not a Damon-Pythias

relationship. Moreover, there was certainly

no subservience of Harding to

Daugherty. If anything, the relationship

was the other way around. Harding

showed him respect, but not deference;

Daugherty constantly deferred to

Harding. Of all the party leaders,

Daugherty had been absolutely loyal to

Harding and, more than any other man,

was responsible for Harding's eleva-

tion to the presidency. The

President-elect had a natural feeling of tremen-

dous gratitude for this man and in

appointing him simply desired to liquidate

his largest political debt.

From the outset, it was rumored that

Daugherty would be made a member

of the cabinet -- probably Attorney

General. His questionable Ohio past,

together with the host of extremely

high-placed enemies he had made as

Harding's political manager, caused immediate

cries of protest. From among

the stream of callers who visited

Marion, there was barely heard a kind word

for Daugherty. But Harding would not be

budged, any more than he would

be on the selection of Hoover. In

mid-December, to a protesting Senator

Wadsworth, he exclaimed: "I have

told him [Daugherty] that he can have

any place in my Cabinet he wants,

outside of Secretary of State. He tells

me that he wants to be Attorney-General

and by God he will be Attorney-

General!"73 When Dawes

met with the President-elect in Florida in January

and remarked that it would be a bad

appointment, Harding replied: "Well,

I wouldn't be here but for him. He has

asked me for the place, and I am going

to give it to him . . . I would not be

right with myself if I did not appoint

Harry."74 In answer to a letter

from William F. Anderson, Bishop of the

Methodist Episcopal Church, expressing

hope that he would not appoint

Daugherty, Harding stated bluntly that

he could not be "so much an ingrate

that I would ignore a man of Mr.

Daugherty's devotion to the party and to

me as an aspirant and a candidate."75

In his Inside Story of the Harding

Tragedy, Daugherty claims that he did

not want to be Attorney General and

urged upon Harding the appointment

of former Senator George Sutherland of

Utah instead.76 But whether he

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 123

formally asked for it or not, Harding

was determined to give him the post.

And there is little doubt that Daugherty

realized that a public offer would

give him increased prestige in the legal

profession and would help wipe out

the curse of dubiety on his past career.

To Ohio friends, he once confided

that one of the main reasons he might

take the position was so he could walk

down Broad Street in Columbus and tell

his arch-enemy and newspaper

man, Robert F. Wolfe, "to go to

hell."77 But it is also plain that Daugherty

was perfectly willing to abide by

Harding's decision and at no time put

pressure on him for the position. The

initiation of the offer certainly belonged

with Harding and not with his campaign

manager. Finley Peter Dunne,

writing in 1936, correctly gauged the

relationship: "I believe that if Harding

had refused him the appointment he would

have gone into a corner and

cried. But then he would have wiped away

the tears and come back and

served as faithfully as ever."78

Up to the moment of the formal

announcement, certain elements of the

press maintained bitter opposition to

Daugherty. This was especially true

with Louis Seibold of the New York World,

who was covering the political

scene at St. Augustine. His continuous

assaults on Daugherty stung Hard-

ing, and on February 21, seeing Seibold

in the crowd of reporters, the Presi-

dent-elect angrily stated: "I am

ready today to invite Mr. Daugherty into

the cabinet as my Attorney-General; when

he is ready there will be an

announcement, if he can persuade himself

to make the sacrifice."79 Later that

very day, Daugherty issued the

statement: "No man could refuse to serve

a friend and his country under the

circumstances."80 Seeing Daugherty a short

time later, Mark Sullivan, another

reporter who also had questioned his

qualifications, extended his hand in

congratulations: "Well, you're going to be

Attorney-General!" In apparent good

humor, Daugherty growled: "Yes, no

thanks to you, goddam you."81

In the midst of all this emotion, the

immediate merits of the appointment

were lost to sight. Daugherty was a

lawyer, and contrary to the opposition

propaganda, a shrewd one. True, he had

spent more of his time being a

lobbyist than a practicing attorney;

yet, that also had its advantages. He

knew lobbying tactics and was now in a

position to use such talent, if he

desired, for the protection of the

common good. As he once told Sullivan:

"I know who the crooks are and I

want to stand between Harding and them."82

Also, he was a consummate politician and

ace trouble-shooter. His potential

value to Harding in handling matters of

patronage was incalculable. But more

importantly, he was a proven and loyal

friend on whom the President-elect

could absolutely rely.

Later events, however, might cast doubt

on the validity of this assessment

as of March 1921. But even some of

Daugherty's contemporary detractors

ultimately mellowed their views. In

1935, in his book, Our Times, Sullivan

claimed that Daugherty was

"high-minded" about his fellow Ohioan and

"would not himself deliberately do

anything that might reflect on Harding."83

In that same year, Louis Seibold wrote:

"I have always believed that

124 OHIO HISTORY

Daugherty really wanted to protect

Harding."84 Writing in 1932, Daugherty's

own assessment of the situation was far

less charitable: "In a moment of

mental aberration I accepted the post of

Attorney-General in the Harding

Cabinet and made the tragic blunder of

my life."85

This was Harding's cabinet: two

Pennsylvanians, and one each from Cali-

fornia, New York, Massachusetts, Ohio,

Michigan, Iowa, Indiana, and New

Mexico. There were two bankers, an

automobile manufacturer, a lodge

director, a humanitarian, a rancher, a

farm-editor, an international lawyer,

and two professional politicians. The

cabinet was relatively young: Hays 41,

Hoover 46, Davis 47, Denby 51, Wallace

54, Hughes 58, Fall 59, Weeks 60,

Daugherty 61, and Mellon 65. There was

even a spread of religious affiliations:

Mellon and Hays were Presbyterian;

Hughes and Davis were Baptist; Weeks

was Unitarian; Daugherty was Methodist;

Hoover was Quaker; Wallace was

United Presbyterian; Denby was

Episcopalian; and Fall was unaffiliated.

Later, during the period of the oil

scandals, it was the vogue to sneer at

the "best minds" and

depreciate these selections. Journals such as the

New Republic and The Nation spoke of Hughes and Hoover as

mere

"deodorizers" for Daugherty

and Fall. Thus are myths born. In actuality, the

vast majority of the nation's press and

of its political observers had

greeted the final cabinet with approval

in 1921. Their chief reservation had

concerned only Daugherty. As the New

York Times put it: "From Hughes

to Daugherty is a pretty long

step." But aside from this, they appeared

content. Editorial comment used such

phrases as "high caliber" and "a

guarantee of success."86 Mark Sullivan,

writing in May 1921, called it

"one of the strongest groups of

Presidential advisors and department heads

in a generation."87 Another

contemporary observer, writing at the same

time, although skeptical of Harding's

own ability, admitted he had "sur-

rounded himself with able

associates."88 In an article for Atlantic Monthly

in March 1923, William B. Munro simply

stated a widely held belief: "No

presidential cabinet during the past

half-century has been better balanced,

or has included within its membership a

wider range of political experience."89

Only against this background can Harding

and his cabinet selections

be viewed with proper perspective. There

were no machinations of evil

intent; there were no "deals"

except the one to assure Hoover's place in

the cabinet; there were no long-range

plans for plunder and booty. Except

for Lowden, the persons whom Harding

really wanted, he got. Five of the

selections were his own (Hughes,

Wallace, Hoover, Fall, and Daugherty),

and four (all except Fall) were secured

in direct conflict with his advisers

or the party leadership. Mellon

represented no "sell-out" to Big Business,

but was a shrewd move in cabinet-making.

Except for the peculiar circum-

stances surrounding Hoover, Mellon would

probably not have been appointed.

Similarly, the Denby selection was the

result of chance and would not

have been made if Harding's own choice,

Lowden, had accepted.

Harding was not simply a cipher in the

selection process but was the

key figure in every critical instance. His penchant for

consultation may have

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET 125

made him appear weak and floundering. It

is true he was subject to occas-

sional fits of indecision. But these

periods were not debilitating, and in

the end he made the decisions and got

his way. Harding did a careful,

conscientious, and independent job of

choosing his cabinet. History's verdict

to the contrary has been unjust.

THE AUTHOR: Robert K. Murray is

Chairman of the Department of History

at The Pennsylvania State University.

|

PRESIDENT HARDING AND HIS CABINET

by ROBERT K. MURRAY

Among the many controversial facets involving the life of the twenty-ninth president of the United States, few have prompted more conjecture and analysis than the choosing of his cabinet. The fact that one of his selections achieved the distinction of being the only cabinet officer to go to jail, that another resigned under a cloud of suspicion, and still a third narrowly missed criminal conviction, places Warren Gamaliel Harding in a unique position as a cabinet-maker. With this record it is little wonder that Harding's skill as a judge of men has been consistently downgraded both by historians and popular writers. Early observers, such as William Allen White, Frederick Lewis Allen, Mark Sullivan, and Samuel Hopkins Adams, all agreed that the Harding cabinet was a crazy quilt of both good and bad, with the bad far outweighing the good.1 Later writers, such as Frederick L. Paxson and Andrew Sinclair, soften the emphasis somewhat but basically arrive at the same conclusion.2 Thus, despite the recognized excellence of certain cabinet choices, the poor selections have captured the lion's share of popular and scholarly attention and have brought down upon the whole selection process a verdict of failure. But this verdict is based largely on the later scandals and not on the actual process of cabinet-making itself. Lost to view is Harding's personal wrestling with the alternative choices, the demands of the contemporary political situa- tion, and his own commitment to certain goals and principles. Until these factors are fully examined, the verdict of failure is at best incomplete and at worst erroneous.

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 185-188 |

(614) 297-2300