Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

MICHAEL SPEER

The "Little Steel" Strike:

Conflict for Control

Historically, strikes in the American

iron and steel industry have been bloody

affairs. The 1892 Homestead strike and

the 1919 steel strike stand as outstanding

examples of industry's militant refusal

to share the power of decision-making with

labor representatives; for steel

management such strikes provided what amounted

to an opportunity for crushing an

incipient union movement. By the mid-1930's,

however, the conflict between labor and

management was complicated by such

New Deal legislation as the Wagner Act

which theoretically guaranteed the right

of collective bargaining. In this new

framework steel management was again chal-

lenged by a young union. The resulting

"Little Steel" strike of 1937 was a two-

fold conflict in which steel executives

were striving to destroy a union as well as

reacting against the New Deal's apparent

support of organized labor. Management

appeared just as eager to realize the

general goal of demonstrating the new union-

ism to be "un-American" as

they were to secure an immediate victory over the

striking steelworkers. As a result, the

strike became a national issue, and the

company-inspired debate over the

question of union lawlessness ranged from the

President of the United States down to

local officials directly affected by the strike.

The efforts of the Steel Workers

Organizing Committee (SWOC) of the Congress

of Industrial Organization (CIO) to

unionize the iron and steel industry in the

United States began in the summer of

1936.1 By spring of the following year the

campaign had its first success: after

secret discussions with the CIO's John L.

Lewis, U.S. Steel's president Myron

Taylor agreed to recognize the SWOC as the

bargaining agent for its members. The

agreement further provided a five dollar

a day minimum for steel workers,

established a forty-hour week, and set up an

institutionalized grievance procedure.2

Taylor's decision won approval from the

liberal press, but the business

community was divided as to its merits, and the

officials of the Little Steel companies

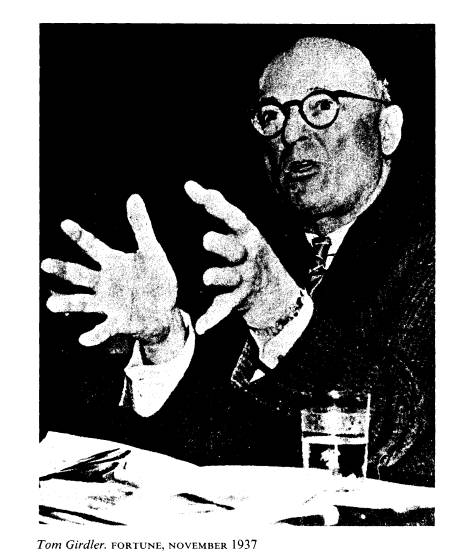

did not like Taylor's "capitulation." Tom

Girdler, president of Republic Steel and

defacto spokesman for all the Little Steel

companies, announced he "was bitter

about this" and called recognition of SWOC

a surrender to the CIO, harmful to both

the steel industry and the nation.3

1. The events of the strike are

recounted in most histories of the American labor movement. Unless

otherwise noted, the following general

discussion is taken from Donald G. Sofchalk, "The Little Steel

Strike of 1937" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, 1961).

2. Vincent D. Sweeney, The United

Steelworkers of America (n.p., n.d.), 28.

3. Tom Girdler, Bootstraps (New

York, 1943), 226; Girdler was also president of the American

Iron and Steel Institute.

Mr. Speer is a doctoral candidate at

Ohio State University.

|

|

|

Although SWOC had won recognition from U. S. Steel, the job of organizing the entire industry was far from complete.4 Following the initial success in Big Steel, union workers began to concentrate their efforts on the Little Steel companies. In late March, Clinton Golden, SWOC's northeastern regional director, sent identical letters to the presidents of the four firms: Republic Steel, Bethlehem Steel, Inland Steel, and Youngstown Sheet and Tube. Golden asked simply for negotiations with representatives of the new union. Sheet and Tube answered that it would be willing to talk, but the resulting April 28 conference ended in strife. The overt disagreement concerned procedure-the Youngstown firm would negotiate with the union but would not commit any agree- ment to a written and signed form. Philip Murray, SWOC national chairman, 4. Walter Galenson, "The Unionization of the American Steel Industry," in Jack Barbash, ed., Unions and Union Leadership, Their Human Meaning (New York, 1959), 126. SWOC attorney Lee Pressman announced after U.S. Steel's recognition of SWOC that the union could not have won an election among the steelworkers for collective bargaining. "This certainly applied not only to Little Steel but also to Big Steel." Quoted in ibid. |

"Little Steel" Strike

275

retorted that the union men would not be

satisfied with only verbal assent to a

contract; if the company was actually

bargaining in good faith, it would not refuse

to sign an agreement. At this impasse

the conference ended. During the final days

before the strike commenced

representatives of all the Little Steel companies met

with union officials and gave them the

same answer: "No signed contract." Man-

agement's position was presented to the

employees in a series of letters and notices.

The message from Republic was typical:

The C.I.O. made no complaints . . .

relative to hours or wages of Republic employees. In

spite of this the Union demanded that

the Company sign their Contract.

This is the only matter at issue, and

the Company at the May 11 meeting informed the

C.I.O. representatives that it still

believes it inadvisable to sign such a contract from the

standpoint of the employees and the

Company itself.

The company circular explained the

reasons for Republic's refusal to sign a

contract. It would be unfair to those

not interested in joining a union; the contract

would not improve wages or working

conditions; the CIO was working toward the

check-off and the closed shop. So far as

Republic was concerned, "MEMBERSHIP

OR NONMEMBERSHIP IN ANY ORGANIZATION IS

NOT A REQUIRE-

MENT FOR EMPLOYMENT." Though not so

outspoken as Republic, the other

companies concurred.5

Why did the managers of Little Steel

decide to fight the union at a time when

it appeared that settlements of the Big

Steel type were acceptable? Just what did

the company officers think they could

gain by forcing a stand-off with the union?

First of all, the executives thought

they could win the strike, especially since they

virtually had the power to decide when

and if it should take place. Also, any vio-

lence that might occur could work to

their advantage. The steel officials could have

negotiated either for longer or shorter

periods than they did. When management

stopped talking, the strike had to come

whether the union organizers were ready

or not; growing strike fever among the

ranks of the unionists would necessitate

this. Through the use of company spies,

management had good reports on the

strength of the union movement, and the

steel officials must have known that the

organizers had not finished their job

when the strike occurred.6 Management also

apparently reasoned that since the SWOC

made no immediate wage or hour

demands, the strike would not arouse

much sympathy for labor. Also, the desire

to fight the union was further

strengthened by a business downturn in May.7

Besides these immediate factors, company

resistance was hardened by the long-

standing tradition of anti-unionism in

the Little Steel companies. Though Republic

Steel had been organized only in 1930,

its president, Tom Girdler, was an old steel

man, and in the company town of

Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, he had pursued such

a strong anti-union policy that

"Girdlerism" had become synonymous with rigid

anti-unionism. The other Little Steel

presidents were as firm as Girdler in their

conviction: they knew they were right;

they thought they could win.

But the fight against the new steel

workers' union was more than an ideological

struggle. Girdler, in particular, was an

ambitious man. He hoped to make the

5. National Labor Relations Board, Decisions

and Orders (Washington, 1939), IX, 247-249.

6. See Senate Committee on Education and Labor, Reports

pursuant to Senate Resolution 266,

74th cong., 1st sess., Report No. 46,

Part 3, Industrial Espionage (Washington, 1938).

7. Walter Galenson, The C.I.O.

Challenge to the A.F.L. (Cambridge, 1960), 100-101.

276

OHIO HISTORY

Republic Steel Corporation so large that

it would be able to rival U. S. Steel. For

his projected merger schemes and for

maintenance of cheap production, he abso-

lutely needed a docile labor force.

Commitment to a signed contract would not

allow him sufficient room for economic

maneuvering.8

Though the other presidents of the

Little Steel companies may not have shared

Girdler's zeal for building a mammoth

steel company, they were just as anxious

as he to be rid of the "union

menace." The action of the steel executives, the com-

pany espionage, and the purchase of

great arsenals by the firms can lead only to

the conclusion that Little Steel was

preparing for a violent confrontation with the

workers.9 A defeat at this critical

moment might crush the SWOC and have reper-

cussions throughout the labor movement. Business

Week warned, "C.I.O.'s Fate

Hinges on Steel Strike." If

management were successful in riding out the strike,

other companies might be tempted to

follow this lead, and the C.I.O. which boasted

it had never lost a strike would lose

its "ever victorious" psychology; business would

regain the initiative.10

In their efforts to break the steel

strike the companies employed the Mohawk

Valley formula. This scheme had

originally been used by Republic to break a

strike in Ohio in 1935, but the name for

the tactic as well as nationwide atten-

tion was gained in a 1936 strike against

Remington Rand Corporation in Ilion,

New York.11 At the conclusion

of the strike in Ilion, the National Association of

Manufacturers published an account of

the struggle clearly setting forth the "for-

mula" for all who wished to use it.

The scheme provided a logical set of steps to

inflame public opinion against the

strikers. First, under company tutelage a citi-

zens committee of respected local

business and civic leaders, ostensibly with no

company connections, should be

established. This committee should then dissem-

inate information stating that local

labor leaders were not local at all but were

"outside agitators" determined

to destroy community prosperity. This step should

be followed by company efforts to

provoke violence on the part of the strikers and

to instill a fear of union-produced

anarchy in the local citizenry. Next, a back-to-

work movement, again ostensibly

initiated by loyal workers and patriotic business

leaders, should be organized while the

striking union was condemned for abridg-

ing the American right-to-work. Finally,

with community spirit outraged against

the union, an important public official

should declare a state of emergency; troops

should be called in to break up picket

lines and enable those who wished to return

to the factory under armed protection.

The strike would then be over.12

Overall, it was important that

management always retain the initiative and keep

the back-to-work movement growing. Crucial

was the necessity that troops or local

police act to favor the companies'

program. Any attempt to use troops to maintain

the status quo indicated a set-back for

the companies. In addition, successful exe-

8. Copy of undated memorandum from

Pierce Williams to Franklin D. Roosevelt; microfilm in

possession of David Brody. Speaking to

the Federal mediation board appointed by President Roosevelt,

Girdler later stated that he "would

not consent to a . . . signed contract because he believed it neces-

sary for the proper operation of his

company that he should be in a position to meet the fluctuating

price of steel by wage variations if

they became necessary. . ."Quoted in Philip Taft, Organized Labor

in American History (New York, 1964), 519.

9. Jerold Auerbach, Labor and

Liberty: The LaFollette Committee and the New Deal (Indianapolis,

1966), 101.

10. Editorial, Business Week, June

12, 1937, p. 13; Sofchalk, "Little Steel Strike," 379.

11. Committee on Education and Labor,

Report 151, Labor Policies of Employers' Associations,

Part 4, The "Little Steel"

Strike and Citizens Committees (Washington, 1940), 90.

"Little Steel" Strike 277

cution of the formula required that

communications media present news and edi-

torials that described the companies and

"loyal" workers as victims of union

violence and intimidation. Such

pro-company coverage would help create a climate

of opinion necessary for successful

functioning of the formula.

The pro-union journalists feared that

Tom Girdler and his fellow steel presidents

might have hit upon a winning

combination. The New Republic, for example, noted

"the Girdlers" had chosen war

by their refusal to sign the contract and were thus

obviously in the wrong. But the magazine

added that the companies' campaigns

for law and order and the right-to-work

seemed to be convincing not only busi-

nessmen, but the general public as well.

Citizens were urging state and national

officials to take the "American

side," the company side.13

On the union side, the SWOC leaders were

faced with the necessity of proving

their organization useful to the rank

and file. Impelled by the demand that SWOC

act, the union's leaders dared delay no

longer--though they were aware that a

strike call in late May would be

premature. As a result SWOC headquarters per-

mitted individual local unions to issue

strike calls.14 On May 25 three companies

were struck, and a strike at Bethlehem's

Johnstown, Pennsylvania, plant followed

in early June.

After four days the most notable event

of the strike occurred--the Memorial

Day riot, known in the annals of the CIO

as the Memorial Day "Massacre." In an

effort to disperse a peaceful parade of

pickets near the Republic mills in Chicago,

police killed ten men. Law officials and

company spokesmen called the occurrence

tragic, but added that the law would

have to be enforced in the face of "armed

union activists." The subsequent

call for law and order elicited by the Memorial

Day riot permeated all areas affected by

the strike. In Chicago the Daily Tribune

noted that the police had behaved with

"scrupulous correctness" and that the

strikers were "a well-trained

revolutionary cadre." Even after congressional investi-

gation had shown that the police had

attacked without provocation, the Tribune

refused to believe the facts, arguing

that the Senate committee was so prejudiced

toward labor that its findings were

"beneath notice."15 Most of the newspaper in

other cities did not take so extreme a

position in condemning the strikers. The

sentiments of the editors of the

Youngstown Vindicator, published in one of the

towns hardest hit by the strike, were

more typical:

12. Richard C. Wilcock, "Industrial

Management's Policies Toward Unionization," in Milton Derber

and Edwin Young, eds., Labor and the

New Deal (Madison, 1961), 293; see also Louis G. Silverberg,

"Citizens Committees: Their Role in

Industrial Conflict," Public Opinion Quarterly, V (March 1941),

17-37. Before the Little Steel strike

had begun the NAM improved on the original technique by pro-

viding anti-union speakers and

propaganda in those towns where unions appeared likely to spring

up in the future. In the autumn of 1936

such speakers were featured in most of the towns the SWOC

had selected for organization drives. See

Committee on Education and Labor, The "Little Steel" Strike,

302-303.

13. "The Girdlers Choose War,"

New Republic, June 30, 1937, p. 207.

14. In addition to the SWOC agreement

with U.S. Steel and the futile negotiations with the repre-

sentatives of Little Steel, other events

were causing union members to favor a strike. On April 12 the

Supreme Court had declared the Wagner

Act constitutional (National Labor Relations Board v. Jones and

Laughlin Steel Corporation, 301 U.S. I), and on the same day a thirty-six hour

strike began at the

Jones and Laughlin plants. The result of

this short-lived SWOC effort was a union victory in which

the firm signed an agreement similar to

that made with U.S. Steel and also went a step farther granting

the SWOC exclusive bargaining

rights with the company. See Taft, Organized Labor, 516.

15. The details of the riot are fully

recounted in Committee on Education and Labor, Report No.

46, Part 2, The Chicago Memorial Day

Incident (Washington, 1937); Chicago Daily Tribune, June 1, 7,

9, 25, 1937.

|

Since the beginning of the year strikers in one place and another have put their rights above those of the public. Indeed . . . it has seemed that the public has no longer had any rights. Unfortunately the authorities in Washington have too often given labor cause to assume that any lawbreaking on their part would be condoned. What happened in Chicago proves that the government is still supreme and that the people want it so. . . . True Americans . . . regret the loss of life, but they condemn men who assert their will is supreme and who defy the world to restrain them.16 In assessing the success of the utilization of the Mohawk Valley formula by the steel companies, it is important to remember the climate of opinion in which the strike was conducted. The sentiment that labor, abetted by New Dealers, was going too far too fast was widespread in 1937. The early months of the year had brought a series of crippling sit-down strikes to the automobile industry.17 Although public reaction to the settlement in Big Steel had been favorable, it should be noted that union gains were minimal and that a contract was signed without any work stop- page or violence. In the Little Steel strike, after the violence on Memorial Day, the companies were able to capitalize on the American myths of law and order, 16. Youngstown Vindicator, June 1, 1937. 17. Sidney Fine, Sit-Down: The General Motors Strike of 1936-1937 (Ann Arbor, 1969). |

"Little Steel" Strike 279

the right-to-work, the sanctity of

private property, and the chronic American fear

of Communist subversion, as successful

employment of the Mohawk Valley for-

mula required.

In Massillon, Ohio, for example, where

public officials were determined to re-

main neutral, Republic Steel was,

nevertheless, able to utilize the formula. The

original position of the city fathers

had been that local law enforcement agencies

would be used neither to intimidate

workers nor to break the strike, and local

opinion supported this decision.18 When

the strike began, a local law and order

league, independent of company support,

was established, but gradually with com-

pany prodding and financial aid, the

league came to espouse only the company

position. The management ruse which had

the most influence on local thought

was the threat that if the strike were

not halted, if Massillon could not provide

the kind of protection afforded in

Chicago, the company would move out. One

company official warned, "Massillon

would be a prairie." "Must Republic," he

asked, "submit to the communistic

dictates and terrorism of the C.I.O.?"19 The

Massillon strikers were exceptionally

well disciplined, but such company pressure

was telling, and the local league soon

initiated a back-to-work movement. Work-

ers were asked to sign a petition to

reopen the plant if they wished to have their

old jobs back. Many did.

Pressure on city officials was just as

constant as that on the league and the work-

ers. Almost daily, representatives of

the company and the law and order league

demanded the appointment of extra

policemen. Although there were fewer arrests

in the city during the strike period

than in other comparable times, Chief of Police

Stanley Switter finally agreed to

deputize extra men. He testified to the National

Labor Relations Board that, worn down

physically by constant harassment, he

agreed to the company plan, though he

could "see what was coming."20 Republic

paid the bond fee for the new policemen,

and on July 11 a "neutral" deputy led

an unprovoked attack on the CIO

headquarters. Three men were killed. The strike

in Massillon, already severely crippled

by Governor Martin L. Davey's use of the

National Guard, was effectively broken

though in some areas men did not return

to work until late summer.21

The editorials in the Massillon Evening

Independent show how the local press

was used to support the company

position. Before the strike actually began, the

paper observed that Massillon was a

steel town and that a strike should be avoided

because everybody would be hurt.22 This

in itself was leaning toward the company

position; and by the time the strike actually

started, the paper sounded like a

mouthpiece of the pro-company law and

order league. By the first week of June

18. National Labor Relations Board, Decisions

and Orders, IX, 252. The following events of the

strike are more vividly summarized in

Robert R. R. Brooks, As Steel Goes . . . Unionism in a Basic

Industry (New Haven, 1940), 131-134, 139-149.

19. National Labor Relations Board, Decisions

and Orders, IX, 267, 256.

20. Ibid., 259, 265-266.

21. The Mohawk Valley formula was also

successful in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, where officials never

made any attempt at neutrality.

Bethlehem Steel contributed generously to the mayor and to the local

citizens committee, and the strike was

broken. Bethlehem's victory in Johnstown was surpassed only in

Monroe, Michigan, site of a Republic

plant. After a series of company threats to leave town, local

vigilantes armed with deer rifles

marched on the mill and dispersed the pickets. See Frank H. Blumenthal,

"Anti-Union Publicity in the

Johnstown 'Little Steel' Strike of 1937," Public Opinion Quarterly, III

(October 1939), 676-682.

22. Massillon Evening Independent, May

15, 22, 1937.

|

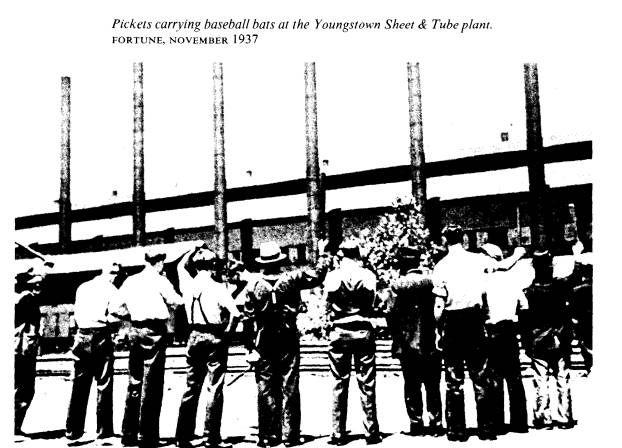

280 OHIO HISTORY it was attacking the Wagner Act because of its inability to prevent the outbreak of strikes. Shortly thereafter the editor noted that he was not taking sides but that the strike was an absolute tragedy for all concerned. This was precisely the "feigned neutrality" stand of law and order leagues and citizens committees in other strike areas. As the strike at Massillon continued, the paper moved more and more to the company side, until at the end it praised Governor Davey's use of the National Guard to enable the mills to reopen.23 A similar situation prevailed in Youngstown where editorial coverage of the strike was much more extensive than in Massillon. In that city where the SWOC had organized six locals in the plants of Republic and Youngstown Sheet and Tube, Police Chief Carl Olsen and Sheriff Ralph Elser were both recipients of arms from Sheet and Tube. These arms--rifles, tear gas, and ammunition--were donated to the law enforcement agencies for the purpose of keeping company-dominated peace in Youngstown. The police forces of Youngstown were also expanded during the strike period with one hundred fifty-two new deputies being sworn in; of this num- ber at least ninety-four were "loyal" company employees. In spite of this official favoritism toward the companies, the back-to-work campaign spread slowly in Youngstown, and it appeared that the strike might be successful. However, the constant pressure from the companies and from their business and civic represen- tatives again eventually succeeded. Violence in Youngstown was attributed solely to the strikers, and back-to-work sentiment was strong by late June.24 Once again change in opinion toward the strike can be seen by following the editorials of the local newspaper, the Youngstown Vindicator. On May 26 the edi- tors commented on a SWOC election victory in Lowellville, Ohio. It was noted that 23. Ibid., June 4, 23, 26, 1937. 24. Committee on Education and Labor, The "Little Steel" Strike, 165-183. |

"Little Steel" Strike

281

the CIO could be built into an effective

and responsible union--the winning of

democratic elections proved this. The

paper stated that it was imperative that the

CIO win the reputation of acting

responsibly and that orderly conduct of strikes

was a necessity. After the strike had

begun in Youngstown, the Vindicator stated

the SWOC should have held an election

there to determine worker sentiment

before calling the strike, but went on

to say the demand for a signed contract

appeared "reasonable."

Workers, warned the paper, must remain peaceful.25 Thus

the Vindicator initially took a

stand that could be interpreted as favoring SWOC.

Such support, however, was posited on

the base that the strike would be non-

violent and that the companies would

soon see the reasonableness of signed contracts.

The reaction in Youngstown to violence

could be predicted from the Vindica-

tor's report that praised the police before the facts of the

Memorial Day strife in

Chicago were fully known.26

But so far as Youngstown was concerned, the Vindica-

tor continued to maintain a neutral position until the

second week in June. At this

time editorials began moving to support

the company position. Although the paper

maintained the companies should sign and

management should face the realities

of new labor organizations, an editorial

on June 11 stated that companies were

within their rights to arm when it

appeared local officials were unable to keep

order. The next day editorials stated

that even if the majority of the steel workers

favored the strike, those who wished to

work should be permitted to do so.27 Prob-

ably such a position was not intended as

support for the companies, but this was

its effect. Management was in such a

position that any call for "law and order"

or for the "right-to-work" was

interpreted against the union. There were rarely any

calls for the companies to be less violent;

apparently no one thought of that. These

slogans were useful grist for the

citizens committee of Youngstown.28 By the end

of June the editorials of the Vindicator

were coinciding nicely with the advertise-

ments of the Youngstown citizens

committee; both deplored Governor Davey's

use of troops to maintain the status quo

in the strike zone while the Federal media-

tion board met, and both held striker

violence the main cause of SWOC's defeat.29

On the national level the Memorial Day

"Massacre" elicited a general call for

more law and order. Though perhaps not

calculated to do so, this fear of anarchy

served company purposes well. The

editors of the Washington Post represented the

majority of Americans when they

editorialized, "If the deplorable events of a week

ago should be repeated in other parts of

the country, the blame will have to be

laid at the door of local

law-enforcement agencies that have either been too weak

or too cowardly to put an end to the

state of anarchy existing in a number of

supposedly law-abiding

communities."30 William Green, president of the American

Federation of Labor and advocate of the

signed contract, criticized the "destruc-

tive tendencies" of the SWOC.31

Editors who had sympathized with the aims of

the strikers claimed that though the

strike was legitimate, the CIO was apparently

condoning illegal strong-arm tactics.

Most persons who took this position usually

25. Youngstown Vindicator. May

19, 26, 27, 1937.

26. See quotation above.

27. Youngstown Vindicator, June

13, 11, 12, 1937.

28. Committee advertisement, ibid., June

19, 1937.

29. Ibid., June 22, 23, 1937.

30. Washington Post, June 6,

1937.

31. New York Times, June 22, 1937;

see also Editorial by William Green, American Federationist

(August 1937), 809.

282

OHIO HISTORY

also believed that the companies were

within their legal rights in refusing to sign

the contract. They did maintain,

however, that the spirit of the Wagner Act

appeared to require a written agreement.32

Though a truly national sample of public

opinion on the Little Steel strike

itself is not available, surveys

indicate that many Americans at the time shared the

sentiment of the Post editorial

quoted above. For example, 47.4% of those polled

in a Fortune survey in October

1937 felt that plants should be kept open for those

who wished to work during a strike. Such

a view may have been partially a result

of traditional American individualism,

but it was also an integral part of manage-

ment's strategy of strike-breaking.

Opinion further supported the company position

when 44.6% of those interviewed agreed

that the CIO forced workers to join its

unions. (The "factory labor"

segment of the sample agreed 34.5% and disagreed

31.6%.) In June of the strike year 50%

of those interviewed by the Gallup Poll

stated their attitude toward organized

labor had changed in the last six months,

and of this number 71% were less in

favor of unions, especially CIO unions. In

more general terms, 45% of the

respondents felt President Roosevelt was "too

friendly" toward unions against

only 14% who believed the administration should

give more support to labor. Only 38%

favored the Wagner Act as it stood, many

apparently urging its amendment to

equalize the power of labor and management.33

Such a state of opinion indicated an

apparent sympathy for the steel companies'

efforts to assert their power and made

the immediate company goal of breaking

the strike much simpler than if opinion

had tended in the opposite direction.

If there was any single incident on

which management was able to capitalize,

it was that of non-delivery of mail in

the Warren and Niles, Ohio, strike areas.

This episode, along with the Memorial

Day riot, had the effect of making the

Little Steel strike a national issue

with ramifications far wider than that of a local

industrial conflict. The mail problem

provided apparent proof that a dangerous

union movement, ostensibly sanctioned by

the Federal Government, was leading

to anarchy--an idea that management

constantly reiterated.

In Warren and in Niles, the SWOC had

volunteered to place maintenance men

in the struck plants, but the company

insisted that non-striking workers who had

remained inside the plants since the

beginning of the strike tend the idle machin-

ery. Should these men leave the

building, however, they would be unable to re-

cross the picket line. Republic Steel

was thus left with the dilemma of supplying

the non-strikers inside the mills. After

a scheme of parachuting food to the plants

had gone awry, the company hit upon the

idea of mailing in supplies. Union pres-

sure was brought to bear on local postal

authorities, and they decided that since

the delivery of foodstuffs across picket

lines would provoke violence, only "reg-

ular" mail would be delivered. The New

Republic lauded the decision of the Post

Office and explained it was reasonable

for the government to refuse to let its

facilities be used for strike-breaking.34

But this was a small voice drowned by all

32. The Wagner Act required only that

companies "bargain in good faith." Not until the 1941

case of H. J. Heinz Company v.

National Labor Relations Board, 311 U.S. 514, did the Supreme Court

declare that actual signing of a

contract was part of this "good faith." In this year the NLRB forced

Little Steel to recognize SWOC.

33. "Survey," Fortune, October

1937, p. 160, 162, 167; Public Opinion Quarterly, II (July 1938),

380, 382. An analysis of newspaper

editorials for October 1935-October 1937 reveals a similar trend of

opinion against the CIO; See George

S. Cree, "A.F. of L. Versus C.I.O., Labor News in Five News-

papers" (unpublished M. A. thesis,

The Ohio State University, Columbus, 1940), 81.

"Little Steel" Strike 283

those raised in protest. After all,

"the mail had to go through."35

The Cleveland Plain Dealer, which

formerly had taken a neutral position and

favored mediation of the strike, stated

angrily, "The crowning evidence of govern-

ment ineptitude will be seen if the

Postoffice [sic] Department upholds the ruling

of its spokesmen in Warren and insists

that mail addressed to a beleaguered steel

plant cannot be accepted . . . because

it is 'irregular'."36 The St. Louis Post Dispatch

was similarly inclined: "We hold no

brief for the Republic Steel Corporation; its

tactics are out of place in this day and

age. But the Postoffice [sic] Department

should scrupulously avoid everything

that even suggests paying back John L. Lewis

for the money he collected for the

Roosevelt campaign last year."37 Both papers

praised President Cleveland's breaking

the Pullman strike of 1893 to get the United

States mail through. Rumors that the

strikers had a formal agreement with the

Post Office and that union members were

regularly examining mail shipments grew.

Both were unfounded. Though there were a

few instances of union men tampering

with the mails, there was never a policy

of allowing them to censor what went into

the plants, and those persons involved

in the tampering were prosecuted by Fed-

eral authorities.38

But the protestors were actually not so

concerned about the alleged mail tam-

perings as they were about the

government's apparent support of the CIO by not

accepting the food packages for delivery

into the struck plant. This sentiment put

President Roosevelt in a precarious

position. On the one hand, there were those

who urged him to intervene and force the

companies to sign a contract with the

steel workers.39 The most

common opinion, however, was that government was

doing too much to aid the strikers. A

sample of what the President could expect

if he made an unpopular move was

experienced when Pennsylvania's pro-labor

Governor George H. Earle used the

National Guard to maintain the status quo

and prevent violence in Johnstown, a

move many interpreted as favoring the incip-

ient union. Committees which had

formerly advocated the use of the Guard to

reopen the plants now made an abrupt

about-face and began to harp on the expense

of maintaining the troops. The national

papers were one in their condemnation of

the governor's action. "Chooses

Easiest Way Out," "Supports Gangsterism," "Brings

in Fascism," "Right to Labor

Denied," and "Surrendered to C.I.O." were typical

editorial titles.40

The Federal Government stayed out of the

strike until June 16 when Roosevelt

received a telegram from Ohio's Martin

L. Davey requesting help. Governor Davey's

mediation attempts had solved nothing,

and he was forced to ask for Federal inter-

vention. Before this date Roosevelt's

only utterance on the strike had been that he

34. "The Week," New Republic, July

16, 1937, p. 142.

35. The United Mine Workers Journal,

usually strongly favoring the SWOC made no editorial

comment on the postal question. The

Youngstown Vindicator agreed with the New Republic that the

Post Office should not be used as a

strike-breaker, but added that the union should refrain from mail

tampering (May 30, 1937). Both the

Canton, Ohio, Repository (June 10, 1937) and the Massillon Evening

Independent (June 24, 1937) castigated the Federal Government for

failure to act impartially, stating

that the strike was becoming a battle

over law and order and the sanctity of private property.

36. Cleveland Plain-Dealer, June

5, 1937.

37. Quoted in Sofchalk, "Little

Steel Strike," 266.

38. U.S. Senate Committee on Post

Offices and Post Roads, 75th cong., 1st sess., Hearings . . .

Regarding Delivery or Nondelivery of

Mail in Industrial Strife Areas (Washington,

1937), 1-17.

39. Thomas L. Stokes, "Washington

Looks at Steel," Nation, June 19, 1937, p. 696.

40. New York Times, June 22,

1937.

284

OHIO HISTORY

was no lawyer, but it seemed logical to

him that the companies should sign. He

had made it very clear, however, that

this was his personal opinion.41

At Davey's request the President took

the next step and appointed a Federal

mediation board. The nation's press

generally supported the move with many

editors stating such action was

tantamount to admitting the Wagner Act was a

failure; they suggested the move could

signal an administration desire to equalize

the power of unions and management.42

From the Little Steel officials, however,

this meek presidential move provoked

cries of anguish. Their back-to-work cam-

paigns were in full swing, and the

President had requested them to maintain the

status quo while negotiations were in

progress. The companies claimed this was a

government effort to halt their plans

for reopening the plants. It was not. It would

have been impossible to carry on any

sort of negotiations while police were break-

ing up the picket lines.43

But the Federal mediation board met the same fate as

that of Governor Davey's: Girdler and

his fellow managers once again refused to

agree to a written contract with the

CIO.44

After the failure of Federal mediation,

Roosevelt made the statement that marked

the beginning of his alienation from

John L. Lewis. Speaking at a press conference

on June 29 the President said he thought

he represented a majority of American

opinion when he said to management and

labor, "A pox on both of your houses."45

Roosevelt did not expatiate on his

remark, but he waived the usual rule and allowed

reporters to quote him directly. Lewis

reportedly retorted, "Which house, Hearst

or DuPont?"46 In September, when

the animosity between the two men was assum-

ing larger proportions, Lewis added

grandly, "It ill behooves one who has supped

at labor's table . . . to curse with

equal fervor and fine impartiality both labor and

its adversaries when they become locked

in deadly embrace."47

Perhaps Roosevelt's statement was the

best he could do at the time. First, as

he himself had said, the quotation

represented American opinion, but it would

have been more accurate to say that this

opinion demanded that the President

curse labor. Second, though the

executive department had been notably silent on

the steel strike issue, Congress had

not. Labor found few active supporters in the

chambers where congressmen from every

section of the country were denouncing

labor's "anarchy,"

"violence," and "communism." Given the growing alienation

of

Congress from the President, it is

evident he could not have emerged from those

violent days without angering someone.

It appears that Roosevelt chose the favor

of Congress and the public at the

expense of John L. Lewis.

Dissent in Congress, however, was only

one cause for the President's statement.

Tom Girdler demanded that Roosevelt rout

the terrorists and get the mails de-

livered. Also, indirect pressure came

from business journals and organizations which

constantly appealed to a public

sympathetic to management. These statements

41. Samuel I. Rosenman, ed., The

Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1937 (New

York, 1941), 264-265.

42. Washington Post, June 18,

1937.

43. Sofchalk, "Little Steel

Strike," 304-306.

44. A few weeks later Girdler reiterated

his position while testifying to the Senate Post Office Com-

mittee: "I am trying to tell this

distinguished committee that I won't have a contract, verbal or written,

with an irresponsible, racketeering,

violent, communistic body like the C.I.O., and until they pass a law

making me do it, I am not going to do

it." Hearings, 244.

45. New York Times, June 30, 1937.

46. Sofchalk, "Little Steel

Strike," 384.

47. Quoted in Taft, Organized Labor, 520.

"Little Steel" Strike 285

seem to have been prompted by two

apprehensions. In the first place, business

clearly shared with many persons the

fear that labor was becoming "too powerful,"

"too radical," and "too

lawless." Second, the deep-seated antipathy to organized

labor which had always existed in the

steel industry was spreading in direct pro-

portion to the growth of the CIO.

One reason the Mohawk Valley formula

worked so well during the Little Steel

strike was that many important business

men misconstrued the impact of the New

Deal and were afraid that Roosevelt was

trying to destroy business power and

perhaps even capitalism.48 Consequently,

they gave strong support to the besieged

steel managers. In a Fortune poll

taken after the strike, most business leaders

praised Girdler for his "gallant

stand" against the union and for "driving home

the point of the right to work."49

Businessmen who were afraid that they saw a

complete change in the American power

structure in the offing considered the new

unions as one important aspect of the

revolution. Business Week was especially

vitriolic: "This is really a new

deal . . . ! Troops are used not to protect property

and the right of willing workers to

work, but to violate property rights and to force

unionization! Business can expect more

of this sort of thing unless it puts up reso-

lute resistance."50 The

editorial castigated President Roosevelt and Governors Earle

and Davey, warning that the President

wanted the unions to win so he could

redistribute the wealth. Comparing the

1937 strike to that of 1919, Steel stated

that conditions were essentially the

same except that in 1919 "Law enforcement

agencies were neutral and gave no aid to

the lawless element, federal and state

troops being used to assure workers

safety in their employment."51 The pro-business

journals also expressed the more

immediate grievances that the CIO was violent,

red, and undemocratic.52

These ideas of business editors were

fully articulated in Congress. Representative

E. E. Cox of Georgia was especially

concerned over the "red menace." After a

long speech contrasting the virtues of

the American Federation of Labor with the

vices of the CIO, he concluded,

"the difference . . . between the AFL and the CIO

is the difference between American

Constitutional Government and the commu-

nistic concept of government in Soviet

Russia." Representative Cox urged Ameri-

cans to support a "voluntary,

democratic labor organization," not a coercive one

like the CIO.53

Representative Cox's fears were echoed

by a fellow congressman. Arthur P.

Lamneck of Columbus, Ohio, told his

colleagues that the country was experiencing

a "testing" during the steel

strike. "I feel that the very foundations of our National

Government are threatened by the

sinister implications which these strikes carry."

Like Cox, Lamneck admitted the right of

labor to organize and to strike, but strikes

should involve economic problems only; a

man who struck only for a signed con-

48. Paul Conkin, The New Deal (New

York, 1967), 74-75, 77-79. Such a view was very logical if

one assumed the American economy had

reached maturity and that future growth would be slight.

If such were the case, Roosevelt's

programs might have actually curbed business power considerably and

effectively redistributed the wealth of

the nation.

49. "In Our Own Experience," Fortune,

November 1937, p. 110, 180.

50. "Business Can Expect

This," Business Week, June 26, 1937, p. 64.

51. "Same Issue in 1919, But Law

Enforced," Steel, June 28, 1937, p. 19.

52. ". . . CIO Ruthlessness is

Censured," ibid., June 21, 1937, p. 22; Washington Post, June

14, 1937;

"In Our Own Experience," Fortune,

November 1937, p. 180.

53. Congressional Record, 75th

cong., 1st sess., 6634-6636.

286 OHIO

HISTORY

tract was apparently not interested in

the future of his country. Guided by wrong-

headed leaders, the growth of the CIO

would bring anarchy to America.54

The solution most advocated by those who

feared CIO's "irresponsibility" was

amendment of the Wagner Act. Few

advocated the act's outright repeal; most saw

this was impossible. A Fortune poll

revealed that less than 10% of management

favored the act--though they made the

most of it by noting it required no agree-

ment whatsoever, only bargaining. About

two-fifths of the executives said they

thought some act was needed, but they

favored a law which would require labor

to incorporate, which would allow employers

to call National Labor Relations

Board elections, and which would make

the closed shop and check-off illegal.55 In

its only official statement on the

strike the National Association of Manufacturers

observed that strikes crippled

production and set back recovery gains. The associa-

tion criticized the abdication of public

authority to "organized mobs" and urged

amendment of the Wagner Act to put an

end to violence and to provide "adequate

protection for the employer, the

intimidated worker, and the public."56

On the other hand, the CIO and the SWOC

had no direct national media for

molding opinion. The union appeared more

concerned with winning the strike by

fighting the steel companies than with

winning the struggle on all fronts as man-

agement was doing. The CIO position was,

in the main, supported by traditionally

liberal magazines such as the Nation and

New Republic, by publications of various

local CIO unions, and by a few members

of Congress. One member of the Senate

told his peers, "In every form of

business enterprise throughout the civilized world

there is an instrument known as the

written contract. No honest man hesitates to

use it."57 With only

slight elaboration this was the theme pursued by the pro-

unionists. Representative Jerry J.

O'Connell of Montana called Girdler a "parasite"

and a "gangster" and added all

that was needed for quick settlement of the strike

was the signatures of four men. From

Youngstown, Ohio, Representative Michael

J. Kirwan launched his congressional

career speaking in support of the SWOC.

Kirwan maintained that labor had

received a "raw deal" for 160 years. Labor was

only demanding its long-neglected

rights. The companies should sign.58

In the Nation and the New

Republic Girdler was featured as the bete noir. The

magazines were of the opinion that a

signed contract could be made flexible enough

to satisfy company officials and that

management's refusal to sign was only a

subterfuge for breaking the union.59

In one article the New Republic reported:

Mr. Girdler and his allies are revolting

against that constitutional victory of labor. They

are doing so by rendering new laws

ineffectual, mobilizing all the reactionary forces at their

command, and stimulating violence,

responsibility for which they attribute to their oppon-

ents. . . . If enough of us become dupes

of the reactionaries, we can help along the devel-

opment of an essentially fascist

counter-revolution.60

54. Ibid., 5749-5753.

55. James A. Rowan, "Closed Shop

and Checkoff," Iron Age, October 7, 1937, p. 92; Wilcock,

"Industrial Management's

Policies," 309-310; Edwin Young, "The Split in the Labor

Movement," in

Derber and Young, Labor and the New

Deal, 72.

56. Quoted in the New York Times, June

1, 1937.

57. Senator Joseph F. Guffey of

Pennsylvania; Congressional Record, 75th cong., 1st sess., 5522-5523.

58. Ibid., 5524, 5753, 6767,

6955.

59. "Steel Bargaining and

Agreement," New Republic, June 23, 1937, p. 171-172.

60. "Girdler's

Counter-Revolution," ibid., July 7, 1937, p. 237.

"Little Steel" Strike 287

The Nation gave an account of the

Memorial Day "Massacre" which was very

close to what the LaFollette Committee

would later disclose. The magazine noted

that none of the policemen were harmed

and that the actual shooting occurred one

and one half blocks from company

property. Other articles and editorials rehashed

the same ideas.

Similar ideas were expounded in labor

publications during this period. The

United Mine Workers Journal found Girdler "stupidly adamant" and said the

com-

panies were infringing upon the civil

rights of the strikers. This journal went further

than the other pro-union magazines in

calling the Chicago melee "planned mur-

der," but this was its only

deviation from typical liberal statements. The journal

maintained that if steel's management

were really bargaining in good faith, it would

be willing to sign a contract. If a

written agreement would lead to the closed shop,

why would not an oral contract do the

same? Why, since so many other steel firms

had signed contracts with the SWOC, did

Little Steel refuse? The obvious answer

was that the companies were acting

illegally.61

In the long run the unionists and their

allies were vindicated, but their efforts

during the strike were unavailing. The

liberals had maintained that a written and

signed contract was the key issue of the

strike and in doing so they neglected other,

very important facets of the conflict.

Though a signed contract had been the orig-

inal issue, the questions of law and

order and of government favoritism to union

labor eclipsed the union demand early in

the strike. In part this refocusing had

resulted from management's propaganda

efforts and from use of the Mohawk

Valley formula, but it was also a

consequence of many conservatives' dissatisfac-

tion with the New Deal, facts the

unionists did not recognize sufficiently. Presented

in pro-management terms, the strike

necessarily became a moral confrontation

without a middle ground for compromise.

In fact, the situation was such that offi-

cials in all levels of government were

led to give some support to the companies,

and management--for a few more

years--was able to convince many important

Americans that the CIO represented

malignant unionism and should not share con-

trol of industrial decisions.

61. See also New Republic: "The Week," June 9,

1937, p. 114; Mary Heaton Vorse, "The Tories

Attack Through Steel," July 7,

1937, p. 246-248; "The Right to Work," August 4, 1937, p. 350; Nation:

"The Shape of Things," June 5,

1937, p. 633; Meyer Levin, "Slaughter in Chicago," June 12, 1937, p.

671-672; Rose M. Stein, "Republic

Sticks to Its Guns," June 12, 1937, p. 668-669; "Settling Strikes:

Law and Reality," June 19, 1937, p.

692-693; Rose M. Stein, "It's War in Youngstown," July 3, 1937,

p. 12-14; Allen Grobin, "O Little

Town of Bethlehem," July 10, 1937, p. 37-39.

United Mine Workers Journal, news items and unsigned editorials, May 15, 1937, p.

12; July 1,

1937, p. 4-5: August 1, 1937, p. 4. See

also C.I.O. News and Steel Labor for similar arguments.

MICHAEL SPEER

The "Little Steel" Strike:

Conflict for Control

Historically, strikes in the American

iron and steel industry have been bloody

affairs. The 1892 Homestead strike and

the 1919 steel strike stand as outstanding

examples of industry's militant refusal

to share the power of decision-making with

labor representatives; for steel

management such strikes provided what amounted

to an opportunity for crushing an

incipient union movement. By the mid-1930's,

however, the conflict between labor and

management was complicated by such

New Deal legislation as the Wagner Act

which theoretically guaranteed the right

of collective bargaining. In this new

framework steel management was again chal-

lenged by a young union. The resulting

"Little Steel" strike of 1937 was a two-

fold conflict in which steel executives

were striving to destroy a union as well as

reacting against the New Deal's apparent

support of organized labor. Management

appeared just as eager to realize the

general goal of demonstrating the new union-

ism to be "un-American" as

they were to secure an immediate victory over the

striking steelworkers. As a result, the

strike became a national issue, and the

company-inspired debate over the

question of union lawlessness ranged from the

President of the United States down to

local officials directly affected by the strike.

The efforts of the Steel Workers

Organizing Committee (SWOC) of the Congress

of Industrial Organization (CIO) to

unionize the iron and steel industry in the

United States began in the summer of

1936.1 By spring of the following year the

campaign had its first success: after

secret discussions with the CIO's John L.

Lewis, U.S. Steel's president Myron

Taylor agreed to recognize the SWOC as the

bargaining agent for its members. The

agreement further provided a five dollar

a day minimum for steel workers,

established a forty-hour week, and set up an

institutionalized grievance procedure.2

Taylor's decision won approval from the

liberal press, but the business

community was divided as to its merits, and the

officials of the Little Steel companies

did not like Taylor's "capitulation." Tom

Girdler, president of Republic Steel and

defacto spokesman for all the Little Steel

companies, announced he "was bitter

about this" and called recognition of SWOC

a surrender to the CIO, harmful to both

the steel industry and the nation.3

1. The events of the strike are

recounted in most histories of the American labor movement. Unless

otherwise noted, the following general

discussion is taken from Donald G. Sofchalk, "The Little Steel

Strike of 1937" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, The Ohio State University, Columbus, 1961).

2. Vincent D. Sweeney, The United

Steelworkers of America (n.p., n.d.), 28.

3. Tom Girdler, Bootstraps (New

York, 1943), 226; Girdler was also president of the American

Iron and Steel Institute.

Mr. Speer is a doctoral candidate at

Ohio State University.

(614) 297-2300