Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

MATTHEW OYOS

The Mobilization of the Ohio

Militia in the Civil War

Fort Sumter's fall in April 1861 broke

like a thunderclap over Ohio.

Overnight, fervent patriotism replaced

months of indecision regarding

Southern secession. When President

Abraham Lincoln called for

75,000 militia on April 15, thousands

of enthusiastic Ohioans rushed

forward. Among this mass, the state's

militia played an important role

in the first weeks of mobilization. At

the heights of state government,

officials struggled to overcome years

of neglect and put Ohio on a war

footing. From a lower level, existing

militia companies would supply a

base upon which authorities could

build. Although it showed some

strengths, Ohio's mobilization in the

Civil War demonstrated the need

for active federal direction of the

nation's militia forces.

In mid-nineteenth century America,

state militia organizations as-

sumed a crucial place in the national

defense. Ideally, the militia would

furnish a ready supplement to the

nation's regular army, a force that

totaled 1,108 officers and 15,259

enlisted men in early 1861. This

system originated in the nation's

colonial heritage and the first years of

independence. Distrustful of a large

standing army and powerful

central government, the Founding

Fathers gave the states considerable

responsibility for the country's

military establishment.1 Heavy reliance

upon the militia lessened following its

mixed performance during the

War of 1812 and was largely nullified

by the regulars' sound showing in

the Mexican War. Nevertheless, militia

forces still retained their status

as the nation's first reserve in 1861.

Mobilization in the Civil War

would put state military organizations

to their severest test ever.

Unlike previous American wars, the

enemy stood right at hand and

presented an immediate threat. In this

conflict, both sides lost the

luxury of time to prepare, which

America's geographic isolation would

have afforded in a major foreign war.

This loss of time especially

Matthew Oyos is a Ph.D. candidate in

history at The Ohio State University.

1. John Mahon, History of the Militia

and National Guard (New York, 1983),

2-3, 97.

148 OHIO HISTORY

plagued states that had failed to

maintain an adequate peacetime

militia. In Ohio, officials had tried to

upgrade military forces prior to

1861, but the state militia was sorely

lacking in many areas when the

call-up came. Weapons, equipment,

supplies, and uniforms all ran

short, and unsure leadership added to an

already trying situation. Still,

Ohio's existing militia system, however

rudimentary, laid the ground-

work for the eventual raising of 100,000

men by the close of 1861.

The story of Ohio's call-up allows not

only a study of a particular

mobilization but also illuminates many

of the militia's characteristics as

an institution. Based on volunteer

companies by 1860, the militia

served an important local function as

well as furnishing a federal

reserve force. In peacetime it

participated in patriotic celebrations,

quelled riots, and sponsored community

affairs. The local basis for

militia companies created priorities

that often differed from those of

federal authorities. Citizen-soldiers

entering national service wanted to

preserve units in which they had

invested time, labor, and pride during

peacetime. They desired to serve with officers

and men with whom

they had formed close associations both

as comrades and as neighbors.

In the years before the war and in the

first months of conflict, Ohio's

militia companies exhibited many of

these same attributes. As a result,

mistrust ensued between militia units

and the War Department, and

disorder plagued Ohio's early

mobilization effort.

In theory, the militia system should

have worked in close conjunc-

tion with the national government.

Federal authorities had the consti-

tutional responsibility of organizing,

arming, and disciplining militia

forces. Under legislation passed in 1792

and 1808, Congress established

the militia and began distributing arms

to the states proportional to

militia enrollments. For their part, the

states would have control over

officer appointments and the training of

citizen-soldiers.2 In Ohio, the

top military staff usually consisted of

the governor as commander in

chief with an adjutant general and

quartermaster general as his

immediate subordinates. Under this basic

staff existed a military

organization arranged hierarchically as

divisions, brigades, regiments,

battalions, and companies. When a

call-up came, the governor estab-

lished an allotment, and the adjutant

general forwarded these orders to

unit commanders. After these

instructions reached the company level,

a captain mustered men liable to service

and asked for volunteers. If

enough men failed to step forward,

compulsory assignment supposedly

took effect. All able-bodied white males

between the ages of eighteen

2. For the actual assigning of these

responsibilities see the United States Constitu-

tion, Article I, Section 8.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 149

and forty-five were legally subject to a

call-up. However, as the

mid-nineteenth century approached, most

states, including Ohio, be-

gan relying on volunteer companies as

their first-line forces.3

By the early 1850s, Ohio's militia

system had fallen into extreme

disrepair. At the highest level, the

posts of adjutant general and

quartermaster general had become

sinecures. As a consequence, the

state sometimes failed to file its

annual report to the War Department,

although its yearly arms allotment

depended upon this communication.4

Many of the higher commands went

unfilled, and the organization

existed more on paper than in actuality.

Those positions with occu-

pants often contained political

appointees who knew little about

military matters. Sometimes commanders

did not even know who

served as their immediate superiors and

subordinates.5 All hope of

making the universal obligation

meaningful had also passed away by

the early 1850s. The state now used

militia liability as a device to

produce revenue. For fifty cents or by

working on a public highway, a

man could dispense with each year's

militia duty.6

The arms situation was equally poor.

Through the years, authorities

had distributed weapons to volunteer

units with little discrimination

and then failed to provide for

maintenance and repair. As a result,

many muskets and other small arms simply

disappeared or became

unusable. Artillery pieces deteriorated

through display in public squares

or repeated use in firing ceremonial

salutes. Owing to this neglect, Ohio

would have been sorely pressed to arm

its troops even had the

command structure been in first-rate

shape.7

Many factors produced this weakness in

the state's militia system.

Outside of annual arms shipments, the

federal government did not

provide much leadership for the creation

of an effective force. As

mentioned, it stressed the regular army

rather than the militia after

1815. In any event, the prevailing

constitutional doctrine of states'

rights worked against active federal

guidance.8 Ohio's state govern-

3. Mahon, History of the Militia, 52-53,

60-61; William H. Riker, The Role of the

National Guard in American Democracy (Washington, D.C., 1957), 21-22.

4. H. B. Carrington, Ohio in the

Civil War (Columbus, no date), doc. 3, p. 2.

5. John S. Fulton to the Quartermaster

General of Ohio, 18 October 1852, Corre-

spondence of the Adjutant General,

Governor, Armory Board and Other Correspon-

dence Relating to the Civil War,

1842-1847, 1850-1856, 1861-1918, Series 1629, Box 1,

Folder 4, Ohio State Archives, Office of

the Adjutant General, Ohio Historical Society,

Columbus, Ohio. Hereinafter cited as

series 1629, OHS.

6. Henry Stanberry, letter, 31 July

1846, Series 1629, Box 1, Folder 2, OHS; Riker,

National Guard, 27-29.

7. Carrington, Ohio, doc. 3, p.

1; Annual Report of the Adjutant General, 1860

(Columbus, 1861), 13.

8. Riker, National Guard, 35-37.

150 OHIO HISTORY

ment also entertained little interest in

a vigorous peacetime militia

during the early 1850s. The Indian

threat had receded long ago, and the

few volunteer companies could meet most

civil disturbances. Building

a substantial militia would have drained

state revenues when no need

for such a force seemed apparent. In a

national emergency, Ohio

counted on having time to raise and

organize its forces. Also, the

potential for political opposition

presented an obstacle. Earlier public

hostility indicated that a revival of

the militia system might spark

popular antipathy. Before volunteer

companies assumed the role of

active forces in the 1840s, militia

musters evoked ridicule, disdain, and

deliberate evasion. Unless an obvious

need arose, any effort at

reviving the militia promised to attract

similar hostility.9

After 1855, Governor Salmon P. Chase and

opposition to the

Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 furnished the

impetus for militia reform.

Chase took office in 1856 as a prominent

figure in the emerging

Republican Party and a staunch opponent

of slavery. In the late 1830s,

he had been a leader in the abolitionist

Liberty Party and had exhibited

rigid anti-slavery views while a United

States Senator from 1849 to

1855.10 Soon after Chase assumed the

governor's chair, the Republican-

controlled legislature passed a series

of personal liberty laws to protect

the rights of free blacks and accused

fugitives. The laws did not block

enforcement of the federal fugitive

slave statute but did have the effect

of slowing the return of runaway

slaves.11 Although the personal

liberty legislation avoided a direct

clash, the actions of state courts put

Ohio and federal authorities on a

collision course. In one case during

1857, a state judge claimed jurisdiction

in fugitive slave actions, issued

a writ of habeas corpus, and then freed

the accused. The release raised

cries that Ohio had begun active

resistance against the federal law and

led Governor Chase to Washington in

hopes of resolving the matter. He

and President James Buchanan each agreed

to dismiss the affair, but

Chase later backed away from this

position. In the heat of his 1857

reelection campaign, he said that a

state had a right to enforce its own

laws and that the national government

should not overstep its bound-

aries. He pledged to defend state laws

against federal tyranny if

9. Riker, National Guard, 26-27,

29-32; Annual Report of the Adjutant General,

1859 (Columbus, 1860), 3-5.

10. Salmon P. Chase to E. S. Hamlin, 22

January 1855, "Diary and Correspondence

of Salmon P. Chase," Annual

Report of the American Historical Association, vol. 2

(Washington, D.C., 1903), 267; Salmon P.

Chase to Charles Sumner, 20 January 1860,

"Chase Diary," 284; Dick

Johnson, "The Role of Salmon P. Chase in the Formation of

the Republican Party," The Old

Northwest, 3 (March, 1977), 25-26, 35.

11. George Porter, "Ohio Politics

During the Civil War Period," Columbia University

Studies in History, Economics, and

Public Law, 50 (1911), 18-21.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 151

Washington attempted any interference.12

To give this position some

weight, Chase turned to the Ohio

militia.

A vigorous militia would help

demonstrate that Chase was serious

about his stand on the state courts.13

At the very least, the governor

wanted a force ready for any contingency

as the 1857 confrontation did

not promise to be the last. Whether he

would have resorted to force

will remain unknown. During the next

federal-state conflict in 1859, the

Ohio Supreme Court unexpectedly struck

down a lower court's

issuance of the writ and thus ended

Ohio's legal offensive against the

Fugitive Slave Law.14 From

Chase's perspective in 1857, the mere

possibility of state resistance might

have forced the Buchanan admin-

istration's hand. A federal retreat on

enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act

would have marked a tremendous victory

for anti-slavery forces and

raised Chase's reputation both in Ohio

and in Republican circles across

the North.

With the fugitive slave controversy

supplying political incentive,

Governor Chase launched a concerted

campaign to revitalize the Ohio

militia. His first efforts brought a

revision of the state's basic militia

law. Passed in March 1857, this measure

retained much of the original

organization but also made some

important changes. The bill left in

place the overall command structure and

kept the state apportioned

into twenty-three divisions with every

county, except Hamilton, serv-

ing as the basis for brigade

organization. Owing to Cincinnati's large

population base, Hamilton County would

provide three brigades.

These larger units were not intended as

field commands; rather they

existed for purposes of administration

and recruitment. As one of its

major changes, the bill stipulated that

divisions or brigades apply

money left over from annual funding

allotments to build or acquire

armories. Through this measure,

lawmakers hoped to reverse the

deterioration of state arms stocks and

provide for the better care of

weapons. Most significantly, the bill

tried to bring all volunteer

companies under tight regulation. The

state government would no

longer furnish units with arms and

equipment unless minimum require-

ments were met regarding uniforms and

company size. This clause

aimed at controlling the arms

distributed around the state and at

regularizing the available companies.15

12. Albert B. Hart, Salmon Portland

Chase (Boston, 1899), 166-69.

13. Carrington, Ohio, doc. 3, p.

5.

14. Salmon P. Chase to Charles Sumner,

20 June 1859, "Chase Diary," 280-81.

15. Acts of a General Nature and

Local Laws and Joint Resolutions, 52nd General

Assembly, 2nd Session, vol. 54 (Columbus, 1857), 44-45, 58; Annual Report,

1860, 5;

Annual Report, 1859, 6.

152 OHIO HISTORY

A number of other reform measures

followed passage of the basic

law. By 1859, the state legislature had

given the divisions and brigades

a more logical structure. A plan also

passed to reduce the overabun-

dance of general officers burdening the

state organization.16 This

measure would have little immediate

effect, however, for it allowed all

men to retain their commands if they so

desired. To improve care for

public weapons and equipment even

further, work began on a state

arsenal building in Columbus, and

Adjutant General Henry B.

Carrington requested funds to pay

militiamen directly for the mainte-

nance of state weapons. Not content with

the simple passage of

legislation, Carrington dispatched the

Quartermaster General to travel

to each county and locate all public

arms. Those companies not

meeting state standards would have to

surrender any public weapons to

the Quartermaster General for return to

Columbus or for sale as

obsolete equipment. As a part of the

reform program, a fresh interest

arose concerning actual conduct in the

field. Officers held sudden

musters to test their unit's

preparedness, and discipline became stricter

at summer encampments.This stress upon

order brought a marked

reduction in drunkenness at the 1859

encampment and saw more time

devoted to the instruction of troops.17

As an important component in the Chase

reforms and a backbone of

the 1861 mobilization, Ohio's volunteer

companies merit a close

examination. Under the legislation of

1857, these units could exist as

artillery, light artillery, cavalry,

infantry, light infantry, or rifle compa-

nies. All but the cavalry and light

artillery units required a minimum of

forty men before the election of

officers and state recognition could

take place. The cavalry and light

artillery formations only needed a

minimum of twenty men before undergoing

organization. To encourage

participation, the state offered

volunteers certain benefits. While a

citizen-soldier, a man was not liable to

labor on the highways or to jury

duty. Fulfilling five years of service

exempted a volunteer from any

further peacetime militia obligation.18

The state's efforts to promote

the militia system proved successful

because the late 1850s witnessed

the addition of many new companies. For

instance, Dayton had three

organized formations in 1856 and one in

the process of organization.

16. Acts of a General Nature and

Local Laws and Joint Resolutions, 53rd General

Assembly, vol.

55 (Columbus, 1858), 162-63; Annual Report, 1859, 12, 16.

17. Annual Report, 1859, 5-7, 11,

14-16; Annual Report, 1860, 5-6; Salmon P. Chase

to the General Assembly, 2 April 1859,

Salmon P. Chase Papers, Ohio Historical Society,

Columbus, Ohio.

18. Acts, 52nd General Assembly, 47,

49-50; H. B. Carrington to D. L. Wood, 16

January 1861, Series 1629, Box 4, Folder

1, OHS.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 153

These units had such titles as the

Montgomery Cavalry, the National

Guards, the Lafayette Jagers, and the

Montgomery Guards.19 By 1860,

the Dayton area had added the Clay

Guard, Dayton Light Guard,

Miamisburg Light Guard, and Dayton Light

Artillery to its military

formations.20 Other

communities also produced a series of new volun-

teer companies.21 Looking at

the overall situation in 1859, the adjutant

general could point with some pride

towards the militia's slow but

steady growth.22

The location and composition of the

volunteer units followed a basic

pattern. Almost all companies originated

in the state's largest towns

and cities. Cincinnati, Cleveland,

Columbus, Dayton, and Toledo by

far had the most numerous and active

militia organizations.23 In the

cities, the formation of companies would

encounter less difficulty as

there were more men with free time and

wealth to take an interest in the

militia. Also, city dwellers had a

larger demand for volunteer compa-

nies than rural residents as they were

more likely to experience civil

violence. The men who led these units

had a vested interest in their

communities. Company officers often

represented such middle-class

groups as store owners, small

manufacturers, and other proprieters.24

They were inspired not only by a desire

to keep order and a sense of

civic duty but also by a social

instinct. At this time, volunteer com-

panies served as an important center of

social life. Company musters

allowed neighbors to gather, and the

guard units periodically sponsored

events such as dances in which the

community could participate.25 The

chance to wear a uniform and have a

taste of military life also appealed

to some. Often gaudy and patterned after

European styles, company

uniforms attracted attention and

identified men as community leaders.26

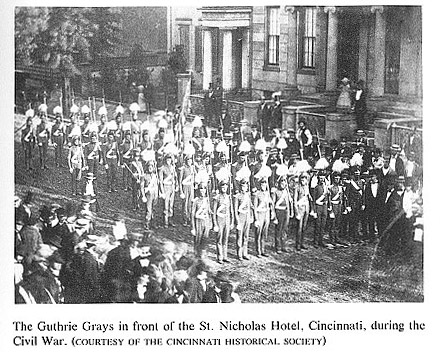

The activities of the Guthrie Grays, a

prestigious unit from Cincinnati,

serve as an example of the companies'

civic responsibilities. Subject to

call-out at anytime to keep order, the

Grays prevented the lynching of

19. Dayton Directory, City Guide, and Business Mirror, 1856-57 (Dayton,

1856), 42.

20. Dayton Directory, City Guide, and

Business Mirror, 1860-61 (Dayton,

1860), 27.

21. Directory of the City of

Cleveland, 1859-60 (Cleveland, 1860), 22; Zanesville

Directory, City Guide, and Business

Mirror, 1860-61 (Zanesville, 1860),

24.

22. Annual Report, 1859, 13.

23. "Annual Report of the

Quartermaster General," in Annual Report, 1860, 28-29;

Dayton Directory, City Guide, and

Business Mirror, 1858-59 (Dayton,

1858), 27;

Columbus Directory, For Two Years Ending

April 1862 (Columbus, 1862), 135-136;

Toledo Directory (Toledo, 1858), 244.

24. Toledo Directory, City Guide, and

Business Mirrorfor 1860 (Toledo, 1860), 23, 67,

119, 123; Dayton Directory, 1860-61, 27,

175, 117, 120; Zanesville Directory, 1860-61,

24, 57, 67, 92.

25. Daily Ohio State Journal (Columbus,

Ohio) 3 January 1861, 2-3; 1 April 1861, 2.

26. Annual Report, 1860, 6-7.

154 OHIO HISTORY

a suspect in the murder of two policemen

during January 1861. More

often, the organization received the

call to take part in public celebra-

tions. In late January 1860, it

participated in ceremonies honoring the

Kentucky and Tennessee legislatures as

they visited Ohio. In February

of the following year, the Grays

escorted President-elect Lincoln

through Cincinnati as he traveled to

Washington for his inaugural.27

Beyond ceremonial functions, the Guthrie

Grays also demonstrated

the political clout possessed by

volunteer units. In 1859, members

sponsored a bill to guarantee the

continued existence of independent

organizations and won approval from the

General Assembly. Their

action responded to the state's efforts

to bring all militia formations

under its direct control. The law

allowed the Grays access to state arms

and granted the same exemptions from

public service that the regular

militia enjoyed. Under this measure, the

unit also protected the right to

dress as it wished. For the state

militia system, the bill had a limited

impact as it applied only to counties

containing cities with more than

80,000 residents, in essence just Hamilton

County. The measure still

demonstrated the influence that

volunteer organizations could attain.28

Despite the restricted nature of the

Guthrie Grays' actions, their

success in the General Assembly still

indicated the limited reach of

Governor Chase's reforms. When Chase

left office in 1860, the state

militia had a long road to travel before

it would become an effective

military system. According to Adjutant

General Carrington, the militia

yet suffered in the higher levels of

organization. He wrote in 1859 that

the state could not claim one complete

regiment, nor did it even

possess the capability to call forth

"one compact, well combined and

well disciplined battalion...."29 The arms

situation also remained

poor, a circumstance that plagued Ohio

right up to April 1861. At the

end of Chase's governorship, the state

had 1,360 muskets, 241 rifles,

and 11 artillery pieces under its

control. This stock of arms would

hardly fulfill requirements in a major

mobilization. Still scattered

around the state were arms with an

estimated value equivalent to 7,505

muskets.30 State budgeting

for the militia system also remained sparse.

Carrington claimed that Ohio's funding

for its Military Department was

low when compared to the militia

expenditures of other states. His

27. E. Hannaford, The Story of a

Regiment: A History of the Campaigns and

Associations in the Field of the

Sixth Regiment, Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Cincinnati,

1868), 25-26.

28. Ibid., 24.

29. Carrington, Ohio, doc. 2, 1.

30. "Annual Report of the

Quartermaster General" in Annual Report, 1859, 18, 25;

Annual Report, 1859, 4-5.

|

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 155 |

|

|

|

assertion bore out as the legislature furnished a contingency fund of only $200, and the quartermaster general had trouble living on an annual salary of $400.31 Overall, the number of men available for immediate call-up provided a measure of Ohio's readiness. State officials could count on less than 2,000 organized, equipped, and drilled militia in November 1859. By comparison, Massachusetts had 4,974 active militia and a state arsenal prepared to arm and equip five times that number. In New York, 18,595 uniformed troops stood ready, while Connecticut could boast of eight regiments and an arms surplus greater than Ohio's total weapons stock.32 Under the next governor, the situation in Ohio would not improve dramatically in the months remaining before the war. Salmon Chase's successor, William Dennison, continued the pro- gram of militia reform upon taking office in early 1860. A Republican, Dennison did not adhere to Chase's inflexible anti-slavery views, but he still wanted to upgrade the militia system. In the past, Dennison had

31. Annual Report, 1859, 13-14; Annual Report, 1860, 15. 32. Annual Report, 1859, 4-5. |

156 OHIO HISTORY

affiliated with the Whigs, and when that

party dissolved he helped

organize the Republicans in Ohio. In

addition to opposing slavery, he

had made his reputation through a

successful law practice and the

railroad business, not to mention his

work in the party machinery.33

During Dennison's first year in office,

the state government just

followed the same reforms begun in 1857.

Collection of arms continued

so that the quartermaster general could

report at the end of 1860 that he

had accounted for 3,229 muskets, 485

rifles, and 30 artillery pieces.34

The number of organized companies did

not rise greatly because the

state still counted less than 2,000

active militia at the close of 1860.

With no new reforms initiated during the

year, the drive for improving

the militia seemed to be gradually

losing momentum.35

Even the secession crisis following

Lincoln's election failed to spark

energetic preparations for war. From

newspapers and other sources,

the public received an awareness of

danger as Southern states began

withdrawing from the Union. The

potential for armed conflict loomed

especially large after federal

authorities refused to abandon Fort

Sumter in Charleston Harbor.36 Yet

despite the possibility of trouble,

the Ohio militia system remained

quiescent. In the months preceding

the war, the state did not attempt to

increase the militia's readiness.

The General Assembly considered

resolutions to prepare the militia

system but produced nothing substantive.

Ironically, the only act

approved that affected the militia

passed on the day Southern guns

opened fire on Fort Sumter.37 Some

of the volunteer companies started

preparing on their own, but their

efforts amounted to very little. The

Guthrie Grays, for instance, entertained

a resolution to provide arms

and officers towards the creation of new

companies, but the proposal

suffered defeat. They settled only upon

firing a salute to the command-

er of Fort Sumter and the Union.38 Rather

than making preparations,

the volunteer companies went about their

business as usual in the

33. Whitelaw Reid, Ohio in the War:

Her Statesmen, Generals, and Soldiers, vol. 1

(Cincinnati, 1895), 20; James A.

Schaefer, "Governor William Dennison and Military

Preparations in Ohio, 1861," Lincoln

Herald, 78 (Summer, 1976), 52; Carl Wittke, ed.

The History of the State of Ohio, 6 vols. (Columbus, 1944), vol. 4: The Civil War Era,

by

Eugene Roseboom, 350.

34. "Annual Report of the

Quartermaster General" (1860), 28.

35. Annual Report, 1860, 11; Ohio

State Journal, 18 January 1861, 1.

36. Ohio State Journal, 10

November 1860, 3; 12 November 1860, 3; 12 April 1861,

2-3.

37. Ibid., 9 January 1861, 2; Acts of

a General Nature and Local Laws and Joint

Resolutions, 54th General Assembly, vol. 58 (Columbus, 1861), 81-83.

38. Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 28-29.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 157

winter of 1861. They remained content to

participate in various

ceremonies and the usual social events.39

The militia's inaction originated in an

anti-war mood that gripped the

state. Although talk of war flourished,

most people wanted peace.

Fighting their fellow citizens appalled

many, and some question

remained about resisting secession.40

In the legislature, the Republican

majority was badly split on how to

handle the issue of disunion and the

continuing question of the Fugitive

Slave Law. On secession, a spirit of

reconciliation prevailed. The

Republicans appeared willing to endorse

a constitutional amendment that

protected slavery where it already

existed, but hostilities commenced

before both chambers fully consid-

ered the measure.41 The

general sentiment to avoid war accounted in

large measure for the militia system's

failure to launch preparations.

From the highest reaches of the state

government down to company

commanders, people hesitated to take

provocative actions.

The attack on Fort Sumter drastically

reversed feeling in Ohio.

Hopes for peace evaporated. Instead,

unbridled patriotism and a desire

for the fight seized the people. After

hearing of the fort's surrender on

April 14, mobs of enthusiastic citizens

poured on to the streets of

Ohio's communities.42 Viewing

such displays of popular emotion, one

observer proclaimed that "the

people have gone stark raving mad!"43

The next day, President Lincoln issued

his call for 75,000 militiamen,

a proclamation greeted with applause in

Ohio. Instructions from the

War Department soon followed assigning

the state its quota of men

under the call-up. Ohio would raise

thirteen regiments of infantry and

could place one major general and three

brigadier generals at federal

disposal. The men enlisted under this

requisition would serve for only

three months, as most authorities

believed that one campaign would

end the war.44

39. Ohio State Journal, 3 January

1861, 2-3; 9 January 1861, 2; 1 April 1861, 2.

40. Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 27-28;

Wittke, History, 273-74.

41. On April 17, the state senate gave

its approval to the amendment, two days after

the call-up. Wittke, History, 375-76;

Reid, Ohio in the War, 20-21.

42. Harry L. Coles, Ohio Forms an

Army, Ohio Civil War Centennial Commission,

no. 5 (Columbus, 1962), 3; William

Kepler, History of the Three Months' and Three

Years' Service from April 16, 1861,

to June 22, 1864, of the Fourth Regiment Ohio

Volunteer Infantry in the War for the

Union (Cleveland, 1886), 14-15.

43. Jacob D. Cox, Military

Reminiscences of the Civil War, vol. 1 (New York,

1900), 3.

44. Altogether the state would

contribute 10,153 men, much more, of course, than it

could count as active militia; William

Dennison to Abraham Lincoln, 15 April 1861, The

War of the Rebellion: A Compiliation

of the Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies, Series III, vol. 1 (Washington, D.C., 1899), 73; Simon

Cameron to

William Dennison, 15 April 1861, Official

Records, Series III, vol. 1, 68-69. Hereinafter

the Official Records, Series III,

vol. 1, will be cited as O.R.

158 OHIO HISTORY

Although federal requirements far

exceeded Ohio's active militia

force, state volunteer companies still

supplied the foundation for the

mobilization. In the very first

regiments organized, the active militia

played a dominant role. Such units as

the Cleveland Grays, Dayton

Light Guards, Columbus Videttes, and

Rover Guards of Cincinnati

tendered their services at first word of

the requisition. All told, twenty

of these organizations filled the

complement of the first two regiments.45

In the atmosphere prevailing after

Sumter's fall, state officials eagerly

accepted companies without any objection

as to composition. They

valued any assistance offered and prized

the experience that the

prewar units represented.

The companies making up the First and

Second Regiments, howev-

er, did not enter service without some

change in their organization.

Most had to recruit new members because

companies required be-

tween seventy and 100 men to qualify for

the call-up. Judging from

prewar arms distribution figures, the

large majority of units had only

forty to fifty active members prior to

hostilities.46 Obtaining enough

men did not prove difficult owing to the

reigning climate of war fever.

In Columbus, the State Fencibles posted

notices around the city

announcing the unit's desire for

recruits. Early on April 16, one day

after the President's proclamation, the

company had filled its rolls.47

The Fencibles' sister units had an

equally good response, for they had

all reached Columbus by April 18 and

started forming into regiments.48

In this first muster of troops, the

state militia system had not yet

received a true test. The mobilization

seemed due more to the initiative

of local companies than to the direction

of state officials. Eager to

participate in the coming action, the

volunteer units flooded the state's

Military Department with offers once

word arrived of the call-up. In

reality, the state's capability to

mobilize men appeared rather limited.

Lacking an adequate military staff, the

governor and adjutant general

45. The full roster of these regiments

was as follows: First Regiment, Three-Month

Service, Company A-Lancaster Guards;

Company B-Lafayette Guards (Dayton); Com-

pany C-Dayton Light Guards; Company

D-Montgomery Guards; Company E-Cleveland

Grays; Company F-Hibernian Guards

(Cleveland); Company G-Portsmouth Guards;

Company H-Zanesville Guards; Company

I-Mansfield Guards; Company K-Jackson

Guards (Hamilton); Second Regiment,

Three-Month Service, Company A-Rover Guards

(Cincinnati); Company B-Columbus

Videttes; Company C-Columbus Fencibles; Com-

pany D-Zouave Guards (Cincinnati);

Company E-Lafayette Guards (Cincinnati); Com-

pany F-Springfield Zouaves; Company

G-Pickaway Company; Company H-Steubenville

Company; Company I-Covington Blues

(Miami); Company K-Pickaway Company. For

this listing see The Military History

of Ohio, 1669-1865 (New York, 1887), 148.

46. "Annual Report of the

Quartermaster General" (1859), 28-29.

47. Ohio State Journal, 17 April

1861, 2.

48. Wittke, History, 383-84.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 159

personally alerted the Columbus

companies about the requisition. The

night of April 15 both men visited the

homes of company officers and

told them to report their units in the

morning. They contacted

companies in other cities by telegraph

and left the same instructions.49

In retrospect, calling out troops

whether by foot or wire probably

amounted to the easiest task faced by

state officials. Taking care of

units once assembled and putting the

state on a war footing represented

much larger tasks.

The First and Second Regiments did not

stay in Ohio long enough to

tax the state's militia system. Concern

for the safety of Washington led

to the dispatch of the two regiments on

April 19, the day after assembly

in Columbus. Governor Dennison informed

the Secretary of War that

Ohio could send the regiments but

without much preparation. Despite

this warning, Secretary Simon Cameron

told him to send the troops.50

The War Department planned to supply the

regiments with full

complements of arms, equipment, and

uniforms once they reached the

capital.51 Unfortunately, the

governor of Maryland closed his state to

troop movements and thus blocked the way

to Washington. Without

the arms required to meet possible

resistance in Maryland, the Ohio

regiments remained in Pennsylvania.

Governor Andrew Curtin prom-

ised to provide for the men while they

were in his state. He boarded

them temporarily in the capital building

at Harrisburg but was unable

to furnish adequate supplies. Finally at

Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on

April 30, the First and Second Regiments

entered the federal service.

They reached Washington in early May and

later participated in the

First Battle of Bull Run before their

three-month term expired.52

To the regiments' satisfaction,

mustering in as federal volunteers did

not upset their original company

organization. State militia units

traditionally harbored the concern that

federal authorities would try to

break up prewar formations before

accepting volunteers into national

service. The citizen-soldiers wanted to

serve in their peacetime units

and resisted being viewed just as fillers

for federal forces. These fears

did not materialize for the First and

Second Regiments because the

national government accepted the units

as offered. Few men suffered

rejection, at least among the officers.

Many of those captains, first

lieutenants, and second lieutenants who

had led their companies before

49. Carrington, Ohio, doc. 1,

11-12.

50. William Dennison to Simon Cameron,

16 April 1861, O.R., 77.

51. Reid, Ohio in the War, 28.

52. Annual Report of the Adjutant

General, 1861 (Columbus, 1862), 6;

Coles, Ohio

Army, 5; Official Roster of the Soldiers of the State of

Ohio in the War of the Rebellion,

1861-1866, and in the War with

Mexico, 1846-1848, vol. 1 (Akron,

Ohio, 1893), 19.

160 OHIO HISTORY

April 1861 retained positions of

command. The companies also man-

aged to keep the regimental officers

that they had elected. Thus the

troops would face the three-month's

service led by commanders with

whom most were long familiar.53 Close

ties between officers and their

units, however, did not necessarily

bring battlefield effectiveness.

Company leaders often held their

positions because of their promi-

nence in the community and not their

military prowess. Some who

proved competent at raising and drilling

men would fail under the test

of fire.

While the First and Second Regiments had

undergone assembly and

then dispatch from Columbus, state

officials had begun to put Ohio on

a war footing. They worked with

remarkable speed and accomplished

much in a short space of time. In the

General Assembly, Republicans

and Democrats acted together to support

the mobilization. Responding

to the governor's appeal for funds, the

Senate passed a $1 million

appropriations bill on April 16. Two

days later, the measure cleared the

House by a unanimous vote. It provided

$500,000 to carry out the

President's requisition, $450,000 to arm

and equip the Ohio militia, and

$50,000 for a special contingency fund.

Before the legislature ad-

journed on May 13, it passed a number of

other mobilization bills.

Lawmakers protected the property of

volunteers from debt execution

and acted to prevent arms shipments to

Southern states.54 They also

defined treason against the state of

Ohio, authorized more general

officers, and stipulated that contracts

for provisions go to low bidders.55

Accomplished in large part by

cooperation between the General

Assembly and governor, this war

legislation did much to counter the

state's inaction during the secession

crisis. Problems that arose during

the mobilization would suggest that

these measures had come too late.

53. Prewar records on existing volunteer

companies are sketchy at best. State records

such as the Annual Reports of the

Adjutant General lack detail in regard to these units.

A determination concerning the retention

of command personnel can be made by

comparison of company lists found in the

Roster of Ohio Soldiers with pre-1861 city

directories. Within the directories can

usually be found a section on military units that

contains a list of officers for local

companies; Cox, Military Reminiscences, 18-19;

William Dennison to General John E.

Wool, 20 April 1861, Series 1629, Box 4, Folder 1,

OHS.

54. For the Governor's efforts to

enforce the latter measure see the following, William

Dennison to H. J. Jeivett, 20 April

1861, Adjutant General's Letterbook (April 20, 1861

- July 16, 1861), 65, Correspondence

from the Adjutant General, 1861-1876, 1880-1898,

Series 146, Box 1, Ohio State Archives,

Office of the Adjutant General, Ohio Historical

Society, Columbus, Ohio. Hereafter cited

as Series 146, AG's Letterbook, OHS. William

Dennison to Alfred Gaither, et al., April

29, 1861, Series 146, Box 1, AG's Letterbook,

190, OHS; William Dennison to T. W. King

and Company, 24 April 1861, Series 146,

Box 1, AG's Letterbook, 130, OHS.

55. Reid, Ohio in the War, 20-24;

Roseboom, History of Ohio, 380.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 161

One other bill passed by the General

Assembly provided the

governor with a larger military staff.56

This law was necessary because

the state maintained just a skeletal

Military Department in peacetime.

The adjutant general and quartermaster

general held the only two

full-time positions. Such offices as the

commissary general, engineer-

in-chief, judge advocate general, and

paymaster general remained filled

but became active only when a demand

arose. The need now was

obvious, and the governor took action to

expand the military staff. By

April 19, he had started organizing the

Commissary Department and,

two days later, indicated that he would

ask the legislature to authorize

assistant adjutant generals. These men

would help take the increasing

burden of work off their department

heads.57 Moving somewhat slower

in other areas, the state did not find a

surgeon general until early May.

At that time, Dr. G. G. Shumard received

the rank of colonel and began

to establish the Medical Department at

General Headquarters.58

While he expanded his military staff,

Governor Dennison also

appointed the four general officers

allotted under the federal quota. His

most important task was selecting a

major general. Dennison recog-

nized that he had no familiarity with

military matters and wanted the

new major general to function as his

principal military adviser. For his

first choice, he desired the services of

Major Irvin McDowell, an Ohio

native. McDowell, however, was attached

to the War Department and

unavailable for the assignment. Dennison

then turned to George B.

McClellan, a man promoted by some

prominent citizens of Cincinnati.

At the time, McClellan headed the

eastern division of the Ohio and

Mississippi Railroad, but he had

graduated from West Point and served

with distinction in the Mexican War. On

April 19, the governor ordered

McClellan to Columbus and made him major

general on April 23.59 In

his choices for brigadier general,

Dennison showed more regard for

politics. Only one of the three, Joshua

H. Bates of Cincinnati, had a

West Point background. The other two

held important positions in the

state senate. Jacob B. Cox of Warren,

Ohio, had obtained influence as

Republican Party leader, while Newton

Schleich of Lancaster, Ohio,

worked for the Democrats in the same

capacity. Though these last two

selections may have seemed poor on the

surface, they did have some

56. Reid, Ohio in the War, 23-24.

57. William Dennison to G. W. Runyan, 19

April 1861, Series 1629, Box 4, Folder 1,

OHS; William Dennison to William

Lawrence, 21 April 1861, Series 146, Box 1, AG's

Letterbook, OHS, 25.

58. Special Order no. 156, 8 May 1861,

Series 146, Box 1, AG's Letterbook, 309,

OHS.

59. Coles, Ohio Army, 7; William

Dennison to G. B. McClellan, 19 April 1861, Series

1629, Box 4, Folder 1, OHS; Cox, Military

Reminiscences, 8-9.

162 OHIO HISTORY

redeeming military qualities. Both men

had participated in the state

militia, and Cox showed an independent

aptitude for military matters.60

Having designated his major commanders,

Governor Dennison also

organized a system of camps for troop

rendezvous. In this undertaking,

state officials again had to recoup from

the lack of prewar preparations.

Ohio did not possess a single camp in

April 1861 for assembling and

training its volunteer units. As a

consequence, the first days of the

call-up were marked by inefficiency and

discomfort for the troops.

Rather than hold companies back until

the state had constructed

camps, the governor allowed units to

pour into Columbus. Without any

means to house or feed the men,

authorities placed them in the city's

hotels at reduced rates and hired

contractors to furnish food. This

arrangement proved expensive but

provided an important stopgap

while the state established camps. By

April 22, the establishment of

camps was almost completed. Officials

had organized Camp Taylor in

Cleveland and occupied Camp Jackson in

Columbus. The Columbus

site stood at Goodale Park, a location

just north of downtown. Both

facilities helped alleviate mobilization

problems, but the state still had

to rely for a time on the services of

hotels and contractors.61

After assuming command in late April,

General McClellan further

improved the troop assembly process.

Adept at administration and

organization, he perceived the need for

a third major camp outside

Cincinnati. McClellan envisioned a

system where the state would

organize its regiments at other locales

and then ship them to the new

facility after mustering into federal

service. Also concerned about

defending the state's southern boundary,

McClellan selected a location

about thirteen miles outside of

Cincinnati along the Little Miami River

and a railroad line. On April 30, work

began on the site, which received

the name of Camp Dennison in honor of

the governor.62

On the whole, the efforts to mobilize

Ohio for war reflected well on

William Dennison. He should receive

credit for his leadership in the

legislature and his fairly rapid expansion

of the military staff. Dennison

also did well by appointing an

experienced military adviser and by

working hard to surmount the problems of

organizing troops. Howev-

er, he brought upon himself many of the

difficulties associated with the

60. Cox, Military Reminiscences, 7-8,

27-28; W. Cooper, Sketches of the Senators

and Representatives in the

Fifty-Fourth General Assembly of the State of Ohio

(Columbus, 1861), 7, 25; Annual

Report, 1861, 7.

61. Reid, Ohio in the War, 28-29;

Coles, Ohio Army, 6; Cox, Military Reminiscences,

18-19; J. A. Peem to H. B. Carrington,

24 April 1861, Series 1629, Box 4, Folder 1, OHS.

62. Cox, Military Reminiscences, 12,

21; George L. Wood, The Seventh Regiment: A

Record (New York, 1867), 20, 23-24.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 163

call-up. The gathering of units without

any prior preparations led only

to confusion and great expense for the

state.

Dennison acted expeditiously because

Ohio needed to organize at

least eleven more regiments and faced

the possibility of federal

requisitions in the future. To assist

the raising of new units, Adjutant

General Carrington tried to use the

existing framework of divisions and

brigades. Officers of these commands

communicated with him, either

asking for instructions or reporting the

progress of recruitment in their

areas.63 The effectiveness of

the divisions and brigades seemed ques-

tionable, at best. When the eleven

regiments underwent organization,

the state did not observe the

mobilization structure established under

the divisions and brigades. Rather,

units originating in general geo-

graphic areas formed the new regiments.

The Fourth Ohio Volunteer

Infantry, for instance, came from

companies raised in Wayne, Stark,

Knox, Delaware, Marion, and Hardin

counties, a grouping that did not

fit any prewar divisional arrangement.

At year's end, the adjutant

general confirmed the system's

uselessness in his annual report. He

recommended abolishing the divisions and

brigades and advocated sole

reliance on regiments and companies as

the basis of organization.64

In the Third through the Thirteenth

Regiments, the existing militia

companies assumed an important role.

Like their counterparts in the

First and Second Regiments, they joined

their respective units with

their prewar organizations essentially

unchanged. The new regiments

differed, however, in that none

contained a majority of prewar com-

panies, a fact showing that the supply

of trained units had been quickly

depleted. Using this limited resource

wisely, the state distributed the

companies throughout the regiments,

seemingly to serve as a leaven of

experience. Thus in the Third Regiment,

the Governor's Guards of

Columbus provided companies A and B,

while the Steuben Guards and

Montgomery Guards of Columbus received

slots as Company I and

Company K respectively.65 The

other regiments followed a similar

pattern in their composition.66 It

should be added that the recruitment

63. Major General J. S. Norton to H. B.

Carrington, 18 April 1861, Series 1629, Box

4, Folder 1, OHS; G. McFall to H. B.

Carrington, 17 April 1861, Series 1629, Box 3,

Folder 7, OHS.

64. Annual Report, 1861, 171.

65. Ohio State Journal, 25 April

1861, 2. The Ohio State Journal lists the Montgomery

Guards as Company J in the Third Ohio

Volunteer Regiment. Presumably, this is an error

on the newspaper's part because the

military did not use the letter "J" to designate

companies. Instead, letter assignments

ran from "A" through "K" with the letter "J"

excepted.

66. Ibid., 26 April 1861, 2; Kepler, Fourth

Regiment, 22; Cox, Military Reminiscenc-

es, 34.

164 OHIO HISTORY

of volunteers into the existing

companies broadened even further the

base of experience. With many citizens

clamoring to serve, some units

grew to such an extent that they

reformed into two or three new

companies. All these expanded units

remained together in the same

regiments. Though willing to modify

their old organizations, the

militiamen did not show any inclination

to serve in different outfits.67

One prewar unit increased so much in

number that it claimed

regimental status. Cincinnati's Guthrie

Grays accomplished this feat

and took their place as the Sixth Ohio

Volunteer Infantry. Coming from

the state's most populous city, the

Grays had built a robust organiza-

tion in the prewar years. Formed in 1854

by a breakaway group from

the Rover Guards, the unit had attracted

so many members by 1858

that it organized into two companies and

called itself a battalion. Very

proud of their outfit, the prewar

volunteers did not dissolve it during

the 1861 mobilization. Rather, they

preserved the two original compa-

nies and just raised the rest under

their sponsorship. Though the

Guthrie Grays now called themselves a

regiment, the unit's composi-

tion actually resembled that of the

others forming under the call-up.

The only difference was that the Grays,

rather than the state, had

controlled the regiment's recruitment.68

As suggested, the majority of companies

in the Third through the

Thirteenth Regiments did not exist

before the war. An inspired

citizenry raised these units after the

President's proclamation of April

15. Recruitment often followed a process

whereby certain community

leaders would announce their intent to

establish a company. They then

held a public meeting at which speakers

delivered emotional speeches

to whip their listeners' patriotism to

new heights. Following the

orations, the sponsors of the new units

would take the names of

volunteers. In this charged atmosphere,

the rolls were not long in

filling. Organization proceeded after a

company achieved the requisite

seventy to 100 men. Normally, the men

who had raised the unit became

its officers. Often, they had some claim

to military knowledge through

a prior militia experience or service in

the Mexican War. With their

officers in place, the companies then

offered their services to the

adjutant general and hoped for

acceptance into one of the regiments.69

67. Ohio State Journal, 26 April

1861, 2.

68. Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 18-22,

30-37; William Dennison to W. K. Bosley, 19

April 1861, Series 1629, Box 4, Folder

1, OHS; Charles F. Goss, Cincinnati: The Queen

City 1788-1912, vol. 1 (Cincinnati, 1912), 316-17.

69. Cox, Military Reminiscences, 14;

Coles, Ohio Army, 7; Theodore Wilder, The

History of Company C. Seventh

Regiment, O.V.I. (Oberlin, OH, 1866),

2-3; H. B.

Carrington, order, 17 April 1861, Series

1629, Box 4, Folder 1, OHS; John F. Schutte

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 165

Having both old and new companies in the

regiments created certain

imbalances. Upon assembly, the new units

had to elect regimental

officers to field and staff commands.

Most men were unfamiliar with

the military qualities of those standing

for election and consistently

selected officers on the basis of their

prominence in prewar militia

companies. Leaders of the existing

volunteer units thus gained a

dominant role in the new regiments.70

Having commanders with at

least some claim to military experience

proved beneficial, but inequal-

ities in equipment, arms, and uniforms

contained the potential for

resentment. The original members of the

prewar militia companies

normally possessed weapons and other

supplies, while men in the new

units went without as a result of

shortages in state stocks. For example,

some men would have tents for shelter,

while others had to fend for

themselves, especially when hotels and

other lodgings were not

available.71 The regiments

adopted a standard form of clothing as one

way to ease the inequalities. As with

its other war supplies, Ohio

suffered from a severe shortage of

regulation uniforms. To get men out

of civilian clothing or impractical

militia costumes until the state

produced enough uniforms, units imitated

the clothing worn in the

Italian unification movement. The

"Garibaldi uniform" consisted of a

red flannel shirt, blue trousers, and

soft felt hat.72 With a clothing

standard established, the regiments

could begin developing some

degree of cohesion.

Although the state could not supply the

regiments with uniforms,

arms, or equipment, the muster into

federal service proceeded without

delay. When the muster took place in

late April and early May, it

occurred at Camps Jackson, Taylor,

Dennison, and a new state facility

near Cincinnati named Camp Harrison. The

induction process seemed

to go smoothly for the Ohio volunteers.

They had to undergo physical

examinations before acceptance, but few

suffered rejection. Federal

regulations stipulated a thorough

medical check, but examiners did not

apply these rules rigidly. One officer

from the Sixth Ohio arose from a

sickbed to avoid missing the enrollment.

He gained acceptance by

painting his cheeks to hide the flush

and by managing to stand

to William Dennison, 17 April 1861,

Series 1629, Box 4, Folder 1, OHS; W. Wilson to

H. B. Carrington, 17 April 1861, Series

1629, Box 3, Folder 7, OHS; W. C. Ferguson to

H. B. Carrington, 17 April 1861, Series

1629, OHS; Kepler, Fourth Regiment, 15-16, 22.

70. For the regiments that followed the

first thirteen, Governor Dennison sought out

men with educations from West Point. He

found fourteen and appointed them to

regimental commands. See Coles, Ohio

Army, 7.

71. Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 33-34.

72. Cox, Military Reminiscences, 13-14.

166 OHIO HISTORY

throughout the procedure.73 In

all, entry into the three-month service

caused few problems for the Ohio units.

Federal authorities accepted

the regiments as offered and did not

break up formations or remove

officers. Therefore the regimental

commands, prewar militia compa-

nies, and newly raised companies passed

into national service almost

untouched .74

As these units were preparing for the federal

muster, the Ohio

military establishment had become

strained to the breaking point.

Although the state could not hope to

arm, clothe, and equip all the men

in the federal quota, Adjutant General

Carrington had accepted com-

panies far above the required number. He

seemed to have lost his head

in the first rush of war and accepted

offers without keeping count. As

a result, Ohio had a total of 30,000

volunteers two weeks after the

President's call-up. Ten thousand went

towards filling the federal

quota, but that still left a large body

of men on hand.75

Not wanting to dampen the passion for

war, Carrington and Gover-

nor Dennison hesitated to disband the

excess units. Dennison first tried

to relieve Ohio of responsibility by

requesting an expansion of the War

Department quota. He wrote to Secretary

Cameron explaining that he

had accepted too many men in the

confusion of the call-up. Saying that

Ohio would have at least twenty

regiments, the governor asked

Cameron to take them all into federal

service. He reasoned that the

national government would eventually

require the troops, acceptance

would boost morale in Ohio, and a large

federal army could intimidate

the South.76 Despite

Dennison's arguments, Cameron was unmoved

and turned down the request.77 Determined

not to disperse the men,

Dennison and Carrington turned to the

state legislature for help. Here

they received a sympathetic hearing. On

April 26, a law passed

allowing the retention of nine extra

regiments as a state militia reserve.

This force would protect the state from

Confederate invasion and also

stand ready to fill any future federal

requisitions. The state also kept

4,000 additional men to serve as a

second reserve. Any units that still

remained would be dissolved.78

73. William Dennison to J. D. Phillips,

1 May 1861, Series 146, Box 1, AG's

Letterbook, 226, OHS; Directions for

Enlisting and Organizing Volunteer Forces in

Ohio, 1861, (Columbus, Ohio); Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 36;

Military History of Ohio,

148-49; Wood, Seventh Regiment, 21.

74. Kepler, Fourth Regiment, 23-25;

Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 34-36.

75. Coles, Ohio Army, 6; Annual

Report, 1861, 6; Carrington, Ohio, doc. 1, 3, 9.

76. William Dennison to Simon Cameron,

22 April 1861, O.R., 101-02.

77. Simon Cameron to H. B. Carrington,

27 April 1861, Series 1629, Box 4, Folder 9,

OHS; Carrington, Ohio, doc. 1, 9.

78. Annual Report, 1861, 6-7.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 167

Ohio's retention of the excess companies

proved extremely fortu-

nate. When Confederate forces cut the

strategically important Balti-

more and Ohio Railroad in western

Virginia, the state reserve force

furnished the first Union response. Not

mustered into federal service,

these troops crossed the Ohio River in

late May and reopened the

railway by occupying Grafton, Virginia.

On June 3, they routed a small

Confederate force at Philippi. McClellan

had chosen the reserve troops

for this task because he wanted to save

the federalized Ohio regiments

for a larger campaign in Virginia's

Kanawha Valley. The federal

regiments were also in the process of

reorganization and thus unavail-

able for immediate service in western

Virginia. Serving for three

months, Ohio's reserve forces performed

well and brought credit upon

Dennison, Carrington, and the General

Assembly for retaining the

excess troops.79

Weapons for the reserve force had to

come mainly from outside

Ohio. In the first weeks of war, the

state could not arm men called

under the federal quota, much less those

in reserve units.80 On April

27, Carrington reported that he had

8,000 unarmed men at Camp

Jackson and 5,000 men lacking weapons at

Camp Taylor. To deal with

this situation, the governor sent

Quartermaster General David L.

Wood and, later, Colonel C. P. Wolcott

to the East Coast to purchase

needed armaments. These men, however,

met only limited success

because of competition with buyers from

other states.81 Though Ohio

had shown much initiative, the federal

government would serve as the

state's chief supplier, and it acted

with relative dispatch to provide

relief. The army sent 10,000 muskets

from the Springfield Armory on

April 25 and, four days later, added

3,000 more to that total. Also,

Major General John E. Wool directed

Illinois to furnish Ohio with

5,000 muskets from state stocks. In its

efforts to arm, however, the

state did not neglect local businesses.

It hired such firms as Hall,

Aryres, and Company of Columbus to

provide caissons, battery

wagons, and traveling forges for

artillery outfits. The state also

contracted with Miles Greenwood of

Cincinnati to rifle smoothbore

muskets and set up a laboratory for

manufacturing ammunition.82 By

79. James McPherson, Ordeal by Fire:

The Civil War and Reconstruction (New York,

1982), 159; Annual Report, 1861, 7;

Cox, Military Reminiscences, 42-44; Carrington,

Ohio, doc. 1, 6-7.

80. Cox, Military Reminiscences, 10.

81. H. B. Carrington to S. W. Cochrane,

27 April 1861, Series 146, Box 1, AG's

Letterbook, 175, OHS; William Dennison

to General D. L. Wood, 18 April 1861, Series

1629, Box 4, Folder 26, OHS; Coles, Ohio

Army, 6-7, 19.

82. Major General John E. Wool to

Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, 25 April 1861,

O.R., 114; Major General John E. Wool to Simon Cameron, 29

April 1861, O.R., 127;

168 OHIO HISTORY

the beginning of May, Ohio could count

on significant supplies of

weapons to arm not only the troops under

federal requisition but a

substantial portion of the reserve

forces.

In early May, a new federal call for

troops supplanted the arms

situation in importance. President

Lincoln issued a proclamation on

May 3 asking for 42,034 volunteers to

enlist for three years or the

duration. Under the requisition, Ohio's

obligation was nine regiments.

This number had little relevance because

the new call eventually aimed

at converting the existing three-months

regiments into more permanent

units. The Secretary of War soon

instructed governors to muster their

three-months regiments into the

three-year service. Applying only to

units not yet sent forward, this order

did not compel three-month

volunteers to convert their enlistments.83

To Ohio, the three-year call

meant that the entire force of eleven

regiments would undergo reorga-

nization. The First and Second Regiments

were not subject, having

long since departed for Washington. This

fresh set of orders hampered

Ohio's ability to put its federalized

regiments in the field and caused

much discontent in the ranks. The

changeover also caused a break-

down in communications between Columbus

and Washington.

To carry out the reorganization, all

eleven regiments gathered at

Camp Dennison. Trouble broke out at once

over the appointment of

officers. The regiments had originally

assembled under state law,

which required the election of

commanders. Under federal jurisdiction

that rule no longer applied, and the

governor possessed full powers of

appointment. When this regulation became

known, discontent spread

throughout the ranks. Men worried that

they would have new officers

imposed upon them without any

consideration of their sentiments.

They saw in the federal rule a danger to

the companies and regimental

staffs with which they had first entered

the service. Removing the old

officers would go far towards destroying

the militia character of the

various units. Whether attached to

organizations with prewar origins or

those raised after April 15, troops

wanted to serve under officers whom

they had chosen.84

The fears about officer appointments

proved unfounded. Among the

eleven regiments, past commissions were

reaffirmed if officers wanted

Richard Yates to Major General John E.

Wool, 30 April 1861, O.R., 147; "Annual Report

of the Quartermaster General," in Messages

and Reports to the General Assembly and

Governor of the State of Ohio, 1861 (Columbus, 1861), part 1, 587-88; Coles, Ohio Army,

22.

83. Fred S. Shannon, The Organization

and Administration of the Union Army,

1861-1865. vol. 1 (Cleveland, 1928), 35-36.

84. Annual Report, 1861, 6;

Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 45-46.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 169

to join the three-year service.85 In

retrospect, the volunteers need not

have worried much about losing their

commanders. Because Governor

Dennison controlled the appointment

process and not federal officials,

a wholesale overthrow of officers was

not likely. Removing command-

ers would have risked a political

uproar, especially when communities

found out what the governor had done to

local units.

After concerns dissipated over officer

appointments, the conversion

to three-year regiments moved rapidly. A

large majority in all grades

enlisted in the long-term service. Among

regimental staffs, almost

every officer committed himself, and

most company officers followed

suit. In the enlisted ranks, about 75

percent made the conversion, while

approximately 25 percent declined

reenlistment.86 As these figures

indicate, the prewar militia and newly

raised companies passed suc-

cessfully into the three-year service.

Those men who did not sign up

would remain with the regiments until

their three-month term had

ended. Although they stayed, recruiting

commenced to fill their places

in the three-year service. Of the

volunteers who chose not to reenlist,

their reasons usually concerned the

length of service or disappointment

with military life. Some felt that their

homes and businesses could not

withstand three years in the army.

Others who had enlisted in the first

rush of patriotism now found their

spirits flagging due to the drudgery

and hardship of camp life.87

The retention of the three-month men

soon caused difficulties in

Camp Dennison and with Washington. With

new recruits filling vacan-

cies in the three-year enlistment,

quarters at the camp soon bulged

from overcrowding. Insubordination arose

as three-month and three-

year soldiers clashed over prerogatives.

To regain control, state

authorities wanted to separate the

three-month men from the rest.

They deemed that the best solution lay

in an immediate mustering out

with pay. The governor and his military

staff made repeated appeals to

Washington for permission to discharge

the three-month men. Suffer-

ing from its own unpreparedness, the War

Department failed to

answer. Frustrated by Washington's

silence, Ohio took matters into its

own hands. The colonels of each regiment

ordered all three-month men

85. Annual Report, 1861, 6;

William Dennison to Simon Cameron, 29 May 1861,

O.R., 242-43.

86. The Roster of Ohio Soldiers provided

the data necessary for these determinations.

Making calculations based upon every

regiment and company would have been a

daunting task. A sampling was taken,

therefore, of regimental officers in the Fifth, Sixth,

Seventh, Ninth, and Tenth Ohio

Volunteers. To examine retention of company officers

and enlisted men, samplings of at least

three companies were each taken from the Fifth,

Sixth, and Tenth Ohio Regiments. See

pages 85-104, 107-24, 133-47, 179-200, 209-33.

87. Wilder, Company C, 8-9;

Hannaford, Sixth Regiment, 45-46.

170 OHIO HISTORY

recruitment because it scattered two to

three thousand unpaid and

thoroughly disillusioned soldiers across

the state. Convinced that the

government did not keep its promises,

these men discouraged others

from volunteering.89

President Lincoln himself issued orders

dealing with the short-term

enlistees. Aware of the situation at

Camp Dennison, Lincoln did not

want the three-month men released. He

felt that such an action would

be a breach of faith and directed that

Ohio reincorporate these troops

into their regiments. Unfortunately, the

damage to future recruitment

had already occurred before these orders

arrived.90 Responsibility for

this problem rested primarily at the

door of Governor Dennison and his

military staff. They acted irresponsibly

in allowing the dispersal of the

three-month men without federal

approval. However, the War Depart-

ment's failure to respond in a timely

fashion brought some of the blame

upon it as well.

In Camp Dennison, the training and

outfitting of the regiments

continued despite the controversy over

the three-month men. These

units finally took to the field in late

June fully armed, equipped, and

uniformed. Under George McClellan, now a

major general in the U.S.

Volunteers, the Third through the

Thirteenth Regiments would see

their first action in western Virginia.91

The battles fought there would

make McClellan's reputation and bring

him command of the Army of

the Potomac.

As noted, the First and Second Regiments

were not included in the

three-year reorganization. Since the

prewar militia dominated in those

two regiments, their fate is worth

pursuing. Soon after the Battle of

Bull Run in late July 1861, the

regiments' three-month term expired,

and they were detached in early August.

Reorganization commenced

almost at once, and by October mustering

into the three-year service

had taken place.92 Having had

a different experience than their sister

units, the prewar companies did not

survive in the First and Second

Ohio. Many men who had served their

three months and experienced

battle felt they had done their duty and

owed no further obligation.

Others reenlisted, but their presence

did not preserve the units' original

militia character. Too few stayed, and

many now served in different

commands. The experience of Company A in

the First Regiment seems

88. Annual Report, 1861, 6-7.

89. Annual Report, 1861, 7.

90. Coles, Ohio Army, 13-14; Annual

Report, 1861, 7.

91. Annual Report, 1861, 7.

92. Roster, vol. 2 (Cincinnati,

1886), 1, 31.

Ohio Militia in the Civil War 171

typical. Originally the Lancaster

Guards, the company retained only its

old captain in the three-year service,

and he soon received a promotion

out of the unit. No other officers

reenlisted nor did many of the men in

the ranks.93 Some of the

three-month men did offer their services again

later in the war.94 They

would join as individual volunteers, however,