Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

ROBERT A. BURNHAM

Obstacles to Plan Implementation in the

Age of Comprehensive City Planning:

Cincinnati's Experience

During the period from roughly 1915 to

1945, when city planning became

institutionalized in the United States,

efforts to rationalize the city through

comprehensive city planning often met

with only measured success.1 This

stemmed, in part, from the nature of

planning itself in that planning, at one

level, was just that, planning, a vision

to guide the future development of the

city. Realizing the city plan

represented a very different matter, one that ne-

cessitated overcoming an often

mind-boggling array of obstacles: city council

members or administrators who lacked a

strong commitment to planning,

competing interest groups that viewed

planning from the perspective of their

own special concerns, and budgets that

did not match the aspirations of city

planners. Although troublesome, these

problems were not what one might

call structural, as were those presented

by non-municipal governing bodies,

which included the county, state, and

federal governments. Because their au-

thority did not derive from, or

superceded, city government, these units of

government could ignore the

recommendations of local city planning com-

missions when making decisions about the

design or location of county,

state, or federal improvement projects.

This created special difficulties for

city planning commissions trying to

uphold the basic principles of

comprehensive city planning, which sought to

secure the welfare of the city as a

whole while simultaneously viewing it as a

pluralistic entity composed of separate

but equal and interdependent parts,

groups, and systems. This perceived

interdependence meant that planning for

one aspect of the city's physical

development would necessitate a thorough

consideration of its relationship to all

others, or what planners called

"coordination," a key concept

in comprehensive city planning. Having

adopted such notions, city planners were

made uneasy by the thought of the

federal government or a county or state

government going forward with a pro-

ject affecting a particular city without

the advice of the local city planning

Robert A. Burnham is Assistant Professor

of History at Macon College.

1. For an assessment of the success of

city planning through the 1930s, see Robert A.

Walker, The Planning Function in

Urban Government (Chicago, 1941), ix, 133, 135-36, 153-

57.

158 OHIO

HISTORY

commission, which was supposed to

perform the function of coordination,

with guidance provided by a

comprehensive city plan prepared by "experts."

In a sense, the problems planners

confronted were made problems by the ide-

als and aspirations of comprehensive

city planning itself, which hoped to di-

rect the course of development to

achieve some sense of unity, coherence, and

order. These aims, however, conflicted

with the division of authority that ex-

isted between various governmental units

whose physical boundaries over-

lapped, a structural feature of

government within the United States.2

The city planning commission of

Cincinnati faced such problems during

the late 1920s and 1930s as it sought to

carry out the recommendations of the

city's comprehensive city plan, which

had been adopted in 1925. Prepared by

planners George B. Ford and Ernest

Goodrich of the Technical Advisory

Corporation, a firm based in New York

City, the Official City Plan of

Cincinnati surpassed most other city plans of the day in terms of

its scope

and won recognition as an important

achievement in the new field of compre-

hensive city planning.3 The

adoption of the plan also had the effect of be-

stowing important powers upon the city

planning commission. Under Ohio

law, once a plan had been officially

adopted by a city planning commission,

all proposals for public improvement

projects had to be submitted to the

commission for approval. If the

commission disapproved, its decision could

be overruled only by a two-thirds vote

of the city council.4 This made the

city planning commission more than a

mere advisory body whose recommen-

dations could be ignored by city administrators

or city council members.5

The state law, however, applied only to

public improvement projects under

the jurisdiction of the city government.

The law did not require city planning

2. In saying that "the problems

were made problems" by the "ideas and aspirations" associ-

ated with comprehensive city planning, I

am not saying that comprehensive city planning was

wrong, misguided, unrealistic or

anything else that might be construed as a criticism. I am

merely trying to point out that

"problems" are often products of the way we choose to view

things. Had planners adopted a different

set of ideas and aspirations, they probably would

have still encountered

"problems" but of a different sort.

3. Cincinnati City Planning Commission, Agreement:

The City Planning Commission of

Cincinnati and Technical Advisory

Corporation of New York City (Cincinnati,

1922), 1-9;

Harlean James, Land Planning in the

United States for the City, State and Nation (New York,

1926), 277: Mel Scott, American City

Planning Since 1890 (Berkeley, Calif., 1969), 229.

4. Laws of Ohio, (1914-1915), vol. 105-06: 455-56; City Planning

Commission, The Official

City Plan of Cincinnati (Cincinnati, 1925), 243.

5. Ohio law, it should be noted, was

unusual in this respect. Few other states adopted the

two-thirds vote requirement, even though

it was favored by leaders in the national city planning

movement and recommended in the model

city planning enabling act adopted by the U. S.

Department of Commerce in 1928. See,

Theodora Kimball Hubbard and Henry Vincent

Hubbard, Our Cities To-Day anrd

To-Morrow: A Survey of Planning and Zoning in the United

States (Cambridge, 1929), 36-38; Scott, American City Planning

Since 1890, 143-44, 231, 243-

45; Advisory Committee on City Planning

and Zoning, U. S. Department of Commerce, A

Standard Planning Enabling Act (Washington, D. C.: U. S. Department of Commerce,

1928),

21.

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 159

commission approval for state or county

projects slated for construction

within the corporate limits of a

municipality.6 And, of course, the state of

Ohio did not have the power to impose

any requirements on the federal gov-

ernment.

Owing to these limitations on its

authority, the city planning commission

of Cincinnati, like those of other Ohio

cities, had to rely on the willingness

of non-municipal governing bodies to

submit their plans for its scrutiny and

to heed its recommendations. The

facilitation of such intergovernmental co-

operation became one of the primary

functions of the commission. Indeed,

'cooperation," a word frequently on

the lips of municipal reformers during the

1920s and 1930s, represents a key

concept for understanding how the com-

mission hoped to achieve the goals of

comprehensive city planning in the

face of (intergovernmental,

intragovernmental, and political) division.7

Because of its voluntary nature,

cooperation, on its face, provided little insur-

ance that the recommendations of the

planning commission would be fol-

lowed. Yet, non-municipal governing

bodies did cooperate with the commis-

sion, at least to the extent of

consulting with it. This may have been an in-

dication of the general acceptance of

the value of city planning. It may, how-

ever, also have been a testament to the

diligence of the Cincinnati city plan-

ning commission and its most influential

member, Alfred Bettman, who was

an insistent voice for adhering to the

principles of comprehensive city plan-

ning.8

A lawyer by training, Bettman became a

well-recognized expert in the field

of city planning and zoning law. He

helped draft the Ohio law that authorized

the creation of city planning

commissions, and was a founding member of the

Ohio Planning Conference, a statewide

organization which drafted and pro-

moted planning legislation. He also

served on the special committee, ap-

pointed by United States Secretary of

Commerce Herbert Hoover, that pre-

pared the United States Department of

Commerce's model city planning and

zoning enabling act of 1928. He is

perhaps best known, however, for con-

vincing the United States Supreme Court

of the constitutionality of zoning in

the case of Village of Euclid v.

Ambler Realty Company (1926).9

6. Though it seems rather clear that the

legislature intended the provisions of the law to apply

only to city governments, ambiguous

wording within the text permitted one to interpret it as ap-

plying to the county and state

governments also.

7. For the planning commission's efforts

to promote intragovernmental cooperation among

the various administrative departments

of the city government, see Robert A. Burnham,

"Planning versus Administration:

The Independent City Planning Commission in Cincinnati,

1918-1940." Urban History, 19

(October, 1992), 231-32, 235, 241-45, 250.

8. Scott, American City Planning

Since 1890, 215, 352; Burnham, "Planning Versus

Administration," 243, 247-48.

9. Robert B. Fairbanks, Making Better

Citizens: Housing Reform and the Community

Development Strategy in Cincinnati,

1890-1960 (Urbana, Ill., 1988), 5-6;

Michael Simpson,

People and Planning: History of the

Ohio Planning Conference (n. p.: Ohio

Planning

160 OHIO

HISTORY

Under Bettman's leadership, the city

planning commission's first and most

successful effort to secure cooperation

among non-municipal governing bod-

ies resulted in the development of a

"Five-Year Improvement Program," or

"coordinated bond program,"

for capital improvements.10 The commission

called upon the Board of County

Commissioners of Hamilton County, the

Board of Education, and the Board of

Trustees of the Public Library to join

together for the purpose of preparing a

bond program that would include all

public improvement projects scheduled

for construction over a five-year pe-

riod. In the past, each of these boards

had put their respective bond issues be-

fore the voters individually, with

little or no consideration for what the others

were doing. The planning commission saw

this piecemeal approach as ineffi-

cient, divisive, and contrary to the

aims of comprehensive city planning,

which emphasized the need to focus on

the city as a whole. By proposing a

coordinated bond program, the commission

hoped to insure that the most im-

portant public improvement projects

identified in the city plan would receive

attention first. Moreover, the

commission argued that a coordinated bond

program would enable the various bond

issuing bodies to present the voters

with a carefully considered group of

improvement projects-a "city-wide pro-

gram"-as opposed to individual

projects.11

To develop such a program, the planning

commission initiated a series of

meetings with the various bond issuing

bodies during the summer of 1926.

These meetings led to the establishment

of the City Committee for Bond

Coordination, which consisted of representatives

from each of the bond issu-

ing bodies and the planning commission.

The committee spent about seven-

teen months preparing a comprehensive

bond program, which the voters ap-

proved in the fall of 1927.12

Though the bond program effort proved

successful, the city planning com-

mission experienced much more difficulty

persuading non-municipal govern-

ing bodies to cooperate when it came to

decisions about the location, design,

Conference, 1969), 15, 40-41; Alfred

Bettman, City and Regional Planning Papers, ed. Arthur

C. Comey, Harvard City Planning Studies,

v. 13 (Cambridge, Mass., 1946), xi, xv-xvii; Scott,

American City Planning Since 1890, 164, 230-32, 238-40, 243-45, 304, 319-20, 325, 331.

10. Cincinnati, Municipal

Activities (1927), 167; City Planning

Commission, "Annual Report"

(1926), 4; City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 1 June 29, 1926, 531 (The repository for

the minutes of the city planning

commission is the office of the city planning commission,

Cincinnati City Hall.)

11. Alfred Bettman to the City Planning

Commission, June 29, 1926, 1-2, Alfred Bettman

Papers [hereafter cited as ABP], box 1,

folder 6 (University of Cincinnati Libraries, Archives

and Rare Books); City Planning

Commission, "Minutes," vol. 1, June 29, 1926, 531; Alfred

Bettman to John T. Faig, August 19,

1926, 1, ABP, box 1, folder 6; City Planning Commission,

The Official City Plan, 255.

12. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 1, July 13, 1926, 535; July 20, 1926, 537; July

27, 1926, 539; August 2, 1926, 541;

April 4, 1927, 593; May 31, 1927, 608; July 5, 1927, 616.

The voters approved public improvement

bonds in the amount of $8,686,000. See, Cincinnati,

Municipal Activities (1928), 12.

|

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 161 |

|

or construction of public improvements. In 1927, for example, the commis- sion became embroiled in a bitter dispute over a state highway project involv- ing the reconstruction of the Eighth Street Viaduct, which connected Cincinnati's central business district to its west-side residential neighbor- hoods. Prepared by county officials working in conjunction with the State |

162 OHIO HISTORY

Highway Department, the plan for the

Eighth Street Viaduct met with the

disapproval of the city planning

commission, which determined that the pro-

posed project was too long and wide,

unnecessarily expensive, a threat to in-

dustrial interests, and likely to

increase traffic congestion.13 Despite the

commission's objections, the Cincinnati

City Council approved the project

by a five to four vote. This sparked a

debate as to whether the requirement of

a two-thirds council vote to overrule

the planning commission applied to

state projects, an issue which was not

entirely clear at the time. The Ohio

law authorizing the creation of city

planning commissions stipulated that

once a planning commission had voiced

its disapproval, "no public" im-

provement could be constructed without a

two-thirds vote of council. Because

the law made no distinction between

city, county, or state projects, a literal

reading of it would lead one to conclude

that it applied to all public projects.

But, despite its specific language, the

law's general intent made it clear that it

was legislation that pertained only to

municipalities.14

The matter ultimately came before the

Ohio Supreme Court, which rendered

a decision on June 1, 1927. The court

held that the Eighth Street Viaduct, as

part of a state highway project, fell

under the section of the Ohio General

Code that authorized a board of county

commissioners to build a road into,

within, or through a municipality after

obtaining the consent of the city

council. Furthermore, the General Code

stipulated that if the consent of

council had been secured, and no part of

the construction was being paid by

the city, as was the case with the

Eighth Street Viaduct, the project would be

treated as if it were being built wholly

outside a municipality.15 The court,

therefore, ruled that the Eighth Street

Viaduct "cannot be affected in any man-

ner by an action or proceeding of

municipal authorities further than clearly

and expressly delegated."16 As

for the two-thirds vote provision of the state

city planning law, the court ruled that

it applied only to the public improve-

ment projects of the city government.

Hence, the majority vote of the

Cincinnati city council had sufficed as

an expression of the city's consent.17

Although the decision of the court

pertained only to the project in question,

the city planning commission realized

that the same reasoning could be easily

applied to other state and county

projects in the future. Expressing such con-

cern in its annual report of 1927, the

commission asserted that if the court's

decision represented "the law of

Ohio, then that law should certainly be

amended at the very next session of the

General Assembly." In the view of

the commission, the exemption of county

and state projects from proper "city

13. City Planning Commission,

"Annual Report" (1927), insert at 5.

14. Laws of Ohio, (1914-1915),

vol. 105-06: 455.

15. Ohio Supreme Court, Ohio State

Reports, vol. 116: 665-66.

16. Ibid., 658.

17. Ibid., 661-62.

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 163

planning procedure" promised to

"produce serious dislocations of the efficient

and orderly development of the

city" with "very detrimental effects upon the

welfare of the people of

Cincinnati."18 Worried that the court decision would

undermine the aims of comprehensive city

planning, Alfred Bettman launched

a campaign to amend the state law, a

campaign which he was well positioned

to lead. At the time, he not only sat on

the city planning commission of

Cincinnati but also chaired the

legislative committee of the Ohio Planning

Conference. In that capacity, he

functioned as the principle draftsperson of

bills that the organization sought to

get passed. In addition, he bore the ma-

jor responsibility for convincing

individual legislators to introduce the

bills.19

While Bettman worked on this legislative

problem, the city planning

commission became involved in another

jurisdictional dispute, this time with

the Board of Trustees of the Public

Library, over the selection of a site for a

new central library. Under Ohio law, the

Board of Trustees of the Public

Library existed as an independent body

which enjoyed sole authority over the

public library system of Cincinnati and

Hamilton County.20 In 1926, the li-

brary board secured the passage of a

bond issue to finance the construction of

a new central library building, the need

for which had been recognized for

some time.21 Indeed, the

planners who prepared the city plan of 1925 had

even recommended a specific location for

such a building, proposing the

block between Washington Park and

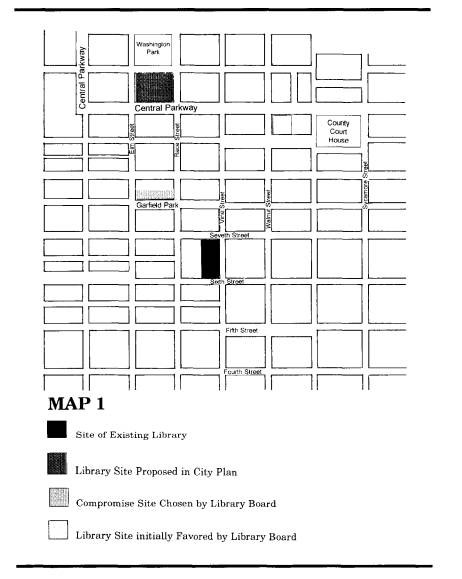

Central Parkway (see map 1).

The selection of this site, it should be

noted, attested to the planners' desire

to create a "civic center" by

grouping public and quasi-public buildings to-

gether near the western end of Central

Parkway, which extended east to west

along the northern rim of the central

business district before jutting northward

to link the downtown area with

residential neighborhoods to the north (see

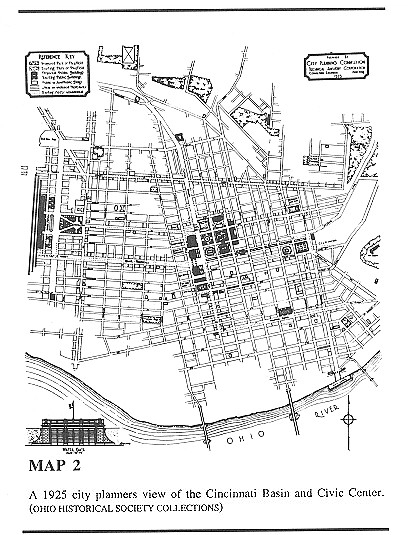

map 1 and map 2).22 As suggested by the

views expressed by the planners,

the proposed civic center represented an

important part of the city plan. They

argued that such a grouping of public

buildings would not only "form an en-

semble that is . . . more impressive

than any one building by itself," but also

help foster a sense of "civic

pride" among citizens and provide a "focal point

for all civic interests, thereby tending

to consolidate the loosely jointed parts

of the city into a cooperating

whole." The planners even went so far as to

18. City Planning Commission,

"Annual Report" (1927), insert at 5.

19. Simpson, People and Planning, 15,

40-41.

20. Jana C. Morford, "Bond Issues,

Sites, Legislation, Court Cases: The Attempt to Construct

a New Central Library for Cincinnati and

Hamilton County, 1923-1933," (Laboratory in

American Civilization, University of

Cincinnati, 1983) 2, 26. Unpublished manuscript in pos-

session of the author.

21. The library board decided on the

bond issue in March of 1926, before the movement for

a coordinated bond program got underway.

22. City Planning Commission, The

Official City Plan, 204.

164 OHIO

HISTORY

assert that there "seems nothing a

city can do that tends so to head up civic

consciousness as the creation of a

central gathering point in a civic center."23

The planners also claimed that the

western elbow of Central Parkway repre-

sented the best location for a civic

center from the perspective of proximity to

existing public buildings, namely City

Hall and Music Hall; accessibility

from the various parts of the city; and

projections concerning the future

growth of the city. Emphasizing

accessibility first, the planners noted that at

no other point in the city did so many

thoroughfares and transit lines con-

verge. As for the issue of growth

trends, it was thought that continued

northward expansion would eventually put

the centerpoint of the central busi-

ness district, which in the mid 1920s

stood at about Sixth Street, very near to

Central Parkway.24

As the first public building slated for

construction since the adoption of the

city plan, the proposed central library

held special import for the city plan-

ning commission, which feared that a

failure to select the site recommended

in the plan would, from the outset,

jeopardize the city's chances of obtaining

a civic center.25 Nothing,

however, required the library board, as a non-mu-

nicipal governing body, to follow the

city plan or even to seek the advice of

the city planning commission.

Nonetheless, in the spirit of cooperation,26

the two bodies met in October of 1927 to

discuss the issue. As a result of

that meeting, the library board agreed

to hire an outside consultant to assess

seven proposed sites.27 The

chosen consultant, William Emerson, chair of

the architecture department at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

studied the strengths and weaknesses of

each site and then ranked them accord-

ing to preference, with first place

going to the site recommended in the city

plan.28 To say the least, the

planning commission welcomed Emerson's re-

port, which seemed to confirm the wisdom

of adhering to the city plan.29

The site favored by Emerson and the city

planning commission, however,

23. Ibid., 202.

24. Ibid., 16, 203-04; "Brief

relative to Site for the new Main Library Building," n.d., 2, ABP,

box 8, folder 4.

25. Ibid., 1.

26. To what extent this cooperation

indicated a commitment to city planning on the part of

the library board is not clear. The

Cincinnati city council, however, apparently felt that some

encouragement was necessary, as suggested

by a resolution it passed in July of 1927 requesting

that the library board "advise

with" the city planning commission on the selection of a library

site. See, City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 1, July 11, 1927, 617.

27. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 1, October 17, 1927, 634. Alfred Bettman,

working behind the scenes, attempted to

influence the selection of the outside consultant in fa-

vor of Edward Bennett, a Chicago

architect who had worked with Daniel Burnham on the

Chicago Plan of 1909. See, Alfred

Bettman to Edgar K. Ruth, October 27, 1927, ABP, box 1,

folder 8.

28. Public Library of Cincinnati and

Hamilton County, Annual Report (1928), 5: Morford,

"Bond Issues, Sites, Legislation,

Court Cases," 14, 16.

29. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, January 24, 1928, 19.

|

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 165 |

|

|

|

had one significant drawback-its cost, which exceeded the amount that the library board had to spend. This factor ultimately proved crucial in determin- ing the decision of the library board, which opted instead for a site located on Central Parkway, three blocks east of the one proposed in the city plan (see map 1). In response, a disgruntled city planning commission passed a resolu- tion asserting its disapproval of the site. Moreover, the commission re- quested that the library board reconsider its decision on the grounds that it de- viated from the recommendations of its own consultant, who had ranked the |

166 OHIO HISTORY

chosen site fourth.30 The

library board, however, dismissed this suggestion,

claiming that its decision conformed

with the Emerson report.31

The library board's site selection upset

not only the city planning commis-

sion, but also the Cincinnatus

Association, one of the most influential civic

organizations in the city. Soon after

the library board announced its decision,

the Cincinnatus Association adopted a

report made by its city and regional

planning committee, which concluded that

the site recommended in the city

plan was the best. This report also

offered a possible solution to the sticky

matter of the cost of the site. It

suggested that the library board purchase a

portion of the land and then seek an

additional bond issue to acquire the re-

mainder.32 Boosted by this

show of support for adhering to the city plan, the

city planning commission decided that it

should "cooperate with civic organi-

zations" in order to prevent a

"great mistake in the selection of a site."33

Feeling the pressure, the library board

rescinded its decision on the building

site and called a public hearing to

allow all individuals and organizations to

express their views.34 The

public hearing, however, hardly indicated resound-

ing support for the site recommended in

the city plan. Some of those who at-

tended the hearing felt that the

utilitarian function of a library, as a place to

house books and do research, ought to

take precedent over any desire to create

a "beautiful monument."35

One wag suggested that the new library should be

built in Spring Grove Cemetery, which

would have placed it in a beautifully

landscaped, park-like setting, but one

created as a resting place for the dead.36

Other individuals, for their own

particular reasons, also favored sites other

than the one proposed by the city plan.

Some downtown office workers, for

example, wanted to erect the new

building on the site of the existing build-

ing, which was located on Vine Street,

between Sixth and Seventh streets (see

map 1). They argued that moving the

library farther north, as recommended

by the plan, would make it inconvenient

for them to use.37

In the face of many opposing interests

and opinions, the library board fi-

nally decided to place the new building

on Garfield Place between Race and

Elm streets, a site which the Emerson

report had dismissed as providing little

improvement over the existing location

(see map 1).38 Exactly why the

30. Ibid.

31. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, February 13, 1928, 26.

32. Committee on City and Regional

Planning, "Report on [the] New Library Site," n. d., but

ca, February 7, 1928, 3-4, ABP, box 8,

folder 4. The Cincinnati chapter of the American

Institute of Architects also favored the

site recommended in the city plan. See, Morford,

"Bond Issues, Sites, Legislation,

Court Cases," 18.

33. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, February 13, 1928, 26.

34. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, February 20, 1928, 27-28.

35. As quoted in, Morford, "Bond

Issues, Sites, Legislation, Court Cases," 18.

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid., 19.

38. Ibid., 20.

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 167

board settled on this site remains

unclear, but there is reason to believe that it

represented an effort to find a

compromise between the various views that had

been expressed at the public hearing.

This explanation seems reasonable con-

sidering that the chosen site was

located about halfway between the

Washington Park site, favored by the

city planning commission, and the site

of the existing library building, favored

by downtown workers. The site also

faced Garfield Park, which would have

provided an attractive setting, similar

to that of the Washington Park area, but

without the high price tag. Yet, de-

spite these agreeable attributes, the

site would prevent the library from be-

coming part of a civic center along

Central Parkway, the primary concern of

the city planning commission, which

remained unhappy about the course

taken by the library board.

It seems that the site also displeased

some powerful downtown businesses,

in particular those which owned valuable

commercial real estate between

Fourth and Sixth streets, the heart of

the central business district. Fearing a

drop in the value of their property,

these businesses tended to oppose devel-

opment that might promote the northward

expansion of the business dis-

trict.39 Their position on

this, of course, was at odds with the city plan,

which had projected that future growth

would naturally move the heart of the

business district farther north,

providing a justification for locating the pro-

posed civic center on Central Parkway.40

With this concern about downtown

property values looming in the back-

ground, the Central Trust Company, a

major banking institution with head-

quarters on Fourth Street, challenged

the validity of the bond issue for the li-

brary building on the grounds that the

statute under which the library board

operated represented special class

legislation, a violation of the Ohio constitu-

tion, which prohibited any grant of corporate

privileges except through gen-

eral laws applicable throughout the

state. The law which had conferred pow-

ers upon the library board clearly

applied to Cincinnati and Hamilton County

only.41 This matter became

the subject of a legal dispute which reached the

39. Cincinnatus Association,

"Report on [the] Federal Building Site," December 12, 1933,

15-16 (Public Library of Cincinnati and

Hamilton County, Department of Rare Books and

Special Collections).

40. "Brief relative to Site for the

new Main Library Building," 2.

41. Morford, "Bond Issues, Sites,

Legislation, Court Cases," 21. The prohibition against

special legislation was included in the

Ohio constitution of 1851, reflecting the emergence of a

national movement in favor of general

incorporation laws. In accordance with this provision

of the constitution, Ohio lawmakers

repealed all special legislation pertaining to municipal cor-

porations and passed in 1852 a general

law that divided Ohio cities into two classes, on the ba-

sis of population, and prescribed the

form of organization and corporate powers for all cities in

each class. Thereafter, all legislation

pertaining to municipal corporations took the form of

general laws that applied to all cities

within a class, a practice which the state courts accepted

as complying with the constitutional

prohibitions against special legislation. Over time, how-

ever, the legislature periodically

modified the classification system by making further divisions

and subdivisions, so that, by the turn

of the century, single-city categories had been created for

168 OHIO

HISTORY

Ohio Supreme Court in March of 1929. The

court not only ruled that the

law was a piece of special legislation,

and thus unconstitutional, but also di-

vested the library board of its legal

authority and invalidated the bond issue for

the library building. This bombshell put

the whole question of obtaining a

new library building in limbo, and the

matter would remain unresolved

through the 1930s.42

In the meantime, Alfred Bettman, working

through the Ohio Planning

Conference, secured the passage of a

state law that gave local city planning

commissions some say over the public

improvement projects of the state and

county governments. Passed by the

legislature in 1931, this law required "the

state, school, county, district or

township official, [or the] board, commission

or [other] body" with jurisdiction

over a project to submit plans to the city

planning commission of any effected

municipality for approval. If the plan-

ning commission disapproved, its

decision could be overruled by the official

or body with jurisdiction. In the case

of a board, commission, or other multi-

member body, however, the law required a

two-thirds majority vote to over-

rule the planning commission.43

The state law, of course, could not bind

the federal government.44 This

posed a problem for the city planning

commission in 1931 when a federal in-

terdepartmental committee composed of

representatives of the United States

Post Office and the United States

Treasury Department began considering

possible sites for the location of a new

federal building in Cincinnati.45 After

the major cities of the state. Under

this system, Cincinnati was the only city in the first grade of

the first class; Cleveland was the only

city in the second grade of the first class; Toledo was the

only city in the third grade of the

first class, and so on. In practice, this meant that a general

law passed for cities in the first grade

of the first class applied to Cincinnati alone, which, as

one commentator put it, rendered the

term "general law" a "legal fiction," and was tantamount

to special legislation. In 1902, this

issue came before the Ohio Supreme Court, which declared

the classification system

unconstitutional. In that same year, the Ohio legislature adopted a

new municipal code to comply with the

court's ruling. The law that granted corporate powers

to the Board of Trustees of the Public

Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, however,

had been passed in 1898 under the old

system. It applied to counties which contained within

their boundaries any city of the first

grade of the first class. Since Cincinnati was the only city

in the first grade of the first class,

the law pertained solely to Hamilton County. See, Edward

Kibler, "Ohio Municipal Code

Commission," Municipal Affairs, 3 (September, 1899), 528-29;

Max B. May, "The New Ohio Municipal

Code," The Annals of the American Academy of

Political and Social Science, 21 (January, 1903), 126; Laws of Ohio (1898),

vol. 93, 192.

42. Morford, "Bond Issues, Sites,

Legislation, Court Cases," 21-23; Cincinnati Historical

Society, The Bicentennial Guide to

Greater Cincinnati: A Portrait of Two Hundred Years

(Cincinnati, 1988), 78.

43. Laws of Ohio (1931), vol.

114, 218; City Planning Commission, "Annual Report" (1932),

6.

44. Alfred Bettman lamented this fact in

a speech delivered in 1927 at the National

Conference on City Planning. He felt

that the federal government as well as the county and

state governments should be made to

comply with the city plan. See, "How One City Enforces

Its City Plan," American City (August,

1928), 94.

45. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, March 30, 1931, 259; May 25, 1931, 266.

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 169

looking at a number of locations, the

committee expressed its preference for a

site on the east end of Central Parkway

near the County Court House (see

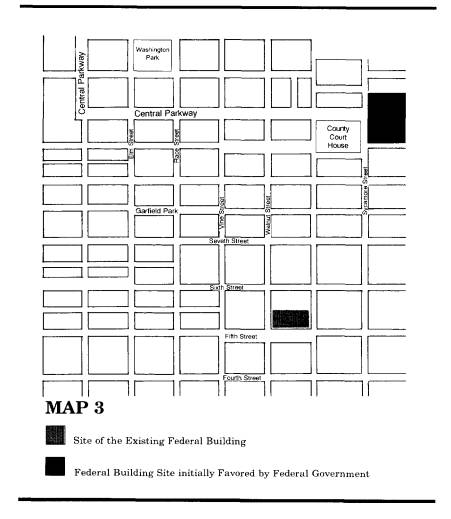

map 3).46 The planning commission

disapproved of this choice, however,

because the city plan recommended that

the federal building, like the proposed

library, be grouped with other public

and quasi-public buildings to form a

civic center along the western end of

Central Parkway. The commission ex-

pressed its position to Assistant

Secretary of the Treasury Ferry K. Heath and

Postmaster General Walter F. Brown,

claiming that the site proposed by the

federal government could "not be

justified by good city planning principles"

and would "handicap"

Cincinnati's efforts to carry out its comprehensive city

plan. The commission also asserted that

even though the federal government

could not be forced to submit its plans

to local planning bodies for approval,

it "should not disregard that

procedure." To drive home the point, the com-

mission also took the liberty of

reminding Heath and Brown that President

Herbert Hoover supported city planning

and recognized that the location of

public buildings, like all other public

improvements, ought to be determined

by a well conceived and comprehensive

city plan.47

The federal interdepartmental committee

showed a willingness to cooperate

by conferring with the planning

commission informally but chose not to

submit plans for its approval.48 To

officials in Washington the appeal of the

planning commission must have sounded

like just one of many opposing

voices emanating from Cincinnati.

Indeed, as in the case of the library, a

flurry of controversy developed over the

proposed federal building because var-

ious local interest groups favored

different sites. For different reasons, the

Cincinnati Bar Association, Chamber of

Commerce, and Cincinnatus

Association fought to maintain the site

of the existing federal building, which

was located in the heart of the central

business district on Fifth Street (see

map 3). The Cincinnati Bar Association

took this stance because it wanted to

insure that the federal building, which

housed the federal court, would remain

conveniently located for its members,

many of whom had offices in the area

around Fifth Street. The Chamber of

Commerce, however, seemed motivated

primarily by a concern for maintaining

the viability of the commercial core

against the forces of northward

expansion. Taking another bent, the

Cincinnatus Association favored not only

keeping the existing site, but the

existing building as well, claiming that

the erection of a new building would

be a wasteful expenditure at that particular

moment in time. Members of the

association said that they took this

position in opposition to increased gov-

46. Cincinnati Times Star, July

7, 1931; July 23, 1932; November 18, 1932.

47. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, November 7, 1932, 337-38. For an expres-

sion of Hoover's support for city

planning, see U. S. Department of Commerce, A Standard

Planning Enabling Act, III-IV.

48. Cincinnati Enquirer, January

20, 1934.

170 OHIO HISTORY

ernmental spending in the throes of the

Great Depression, even if the expendi-

ture meant an improvement for their own

city. Two other organizations, the

Central Parkway Association and the Main

Street Merchants Association,

weighed into the fight with the hope of

locating the federal building on

Central Parkway, presumably to enhance

their own property interests.

Rounding out the mix of concerned

interests, the Cincinnati Building Trades

Council and the American Federation of

Labor went on record as supporting

the construction of a new federal

building regardless of location. Viewing the

proposed building as a kind of work

relief measure, labor just wanted to make

sure that it got built.49

As if the differences between organized

groups were not enough, a number

of local realty firms, operating under

the profit motive, entered the fray, with

each one offering property for sale to

the federal government. Their actions

greatly complicated the selection

process by adding to the number of proposed

sites, which reached ten at one point.50

More important, however, the in-

tense private competition among

realtors-which yielded much "lobbying and

backstairs stuff'-worked to obscure the

important public question of how

best to plan for the city's future.51

This, unsurprisingly, deeply troubled

the city planning commission, which

attempted to separate itself from all of

the dissension and interest group bick-

ering by announcing its desire to remain

objective, which meant that it would

not endorse or reject any particular

site without subjecting it to thorough

study. Besides the site recommended in

the city plan, only one of the other

proposed sites, the one which the

federal government had tentatively endorsed,

had been studied by the commission.

Since none of the other proposed sites

had been thoroughly examined, the

commission refrained from expressing an

opinion on them. Instead, it reiterated

its position in favor of the site sug-

gested by the city plan, which

represented the product of detailed studies con-

ducted by experts. The commission,

however, refused to rule out other pos-

sible locations so long as they too

withstood careful study.52

After three years of local conflict over

this matter, the planning commis-

sion attempted to break the logjam and

strike a note for comprehensive city

planning by calling for the restudy of

the city plan as it pertained to the loca-

tion of a civic center. The lack of

local support for the recommendations of

the city plan, as indicated by the

diversity of opinion over where to locate the

federal building and the main branch

library, worried the commission. It

thought that a new study might help

"establish public confidence" in the idea

49. Cincinnati Times Star, October

5, 1931; October 8, 1931; November 30, 1931; Cincinnati

Enquirer, November 8, 1932; Cincinnati Times Star, December

6, 1932; December 21, 1932;

City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, November 13, 1933, 383.

50. Cincinnati Times Star, October

5, 1931.

51. Cincinnati Times Star, November

18, 1932.

52. Cincinnati Times Star, January

9, 1933; Cincinnati Post, January 20, 1934.

|

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 171 |

|

|

|

of creating a civic center,52 and perhaps enable the city to speak with one voice on the matter.53 In other words, the commission felt that a new study might provide a basis for cooperation between the various interested groups. But the commission also advocated restudy because local conditions seemed to

52. Cincinnati Enquirer, February 6, 1934. 53. One might argue that the planning commission's desire to unify public opinion paralleled its aims for the physical development of the city. Through the activity of city planning, the commission sought to coordinate the various aspects of urban development in order to achieve some sense of unity. |

172 OHIO

HISTORY

suggest that some of the projections of

the city plan needed reconsideration.

In particular, the commission had begun

to doubt that the city would experi-

ence the kind of growth envisioned in

the early 1920s, which had been a key

factor in determining the location for a

civic center.55

To make the study, the commission hired

Harland Bartholomew, a promi-

nent city planner from St. Louis.56

After four months of work, Bartholomew

presented the commission with a rather

inconclusive report in the fall of

1934. As two possible locations for a

civic center, Bartholomew suggested

(1) Fifth Street, east of Sycamore

Street, or (2) the eastern end of Central

Parkway near the Court House. But he

also recommended that neither loca-

tion be selected until they were

subjected to further study.57 This left the is-

sue of where to locate the civic center

unresolved, and the city would continue

to debate the matter into the 1940s.58

In the meantime, the federal govern-

ment erected a new federal building,

which was completed in 1939, on the site

of its predecessor.59

As the Cincinnati experience suggests,

the obstacles to plan implementa-

tion presented by non-municipal governing

bodies and special interest groups

presented significant problems for city

planning commissions during the

1920s and 1930s. Recognizing this, the

city planning commission of

Cincinnati tried to secure the

cooperation of county, state, and federal officials

by emphasizing the value of planning

and, more specifically, the importance

of adhering to the principles of

comprehensive city planning, which were

based on the assumption that the various

facets of the city's development

were interdependent and therefore must

be considered in relation to each other

and to the city as a whole. The city

planning commission also stressed that

the city plan, as the product of careful

studies made by experts, should be ac-

cepted as the appropriate guide for the

future development of the city. The

limited success of the city planning

commission, in a city that was renowned

for its commitment to planning,

highlighted the weaknesses of this ap-

55. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 2, February 5, 1934, 392; vol. 3, September 8,

1937, 241; Cincinnati Post, February 5, 1934, 1; City Planning Commission,

"Annual Report"

(1932), 4-5.

56. Cincinnati Post, January 20,

1934; City Planning Commission, "Minutes," vol. 2, May 23,

1934, 405; Cincinnati Enquirer, May

24, 1934; City Planning Commission, "Minutes," vol. 4,

April 11, 1938, 36.

57. Cincinnati Times Star, September

4, 1934; Cincinnati Enquirer, November

22, 1934; City

Planning Commission,

"Minutes," vol. 3, December 3, 1934, 24; Harland Bartholomew, "A

Public Buildings Group, Cincinnati,

Ohio," (1934), 19, 24, ABP, box 2, folder 8.

58. City Planning Commission,

"Minutes," September 23, 1935, 74-75: April 21, 1937, 201a-

201b; September 8, 1937, 241-42;

September 20, 1937, 244; March 7, 1938, 22; April 11, 1938,

34-36; April 11, 1945, 31-32.

59. Cincinnati Enquirer, November

13, 1934; Cincinnati Post, January 14, 1939. It should be

noted that those who favored the site of

the old federal building never rallied around the idea

of making a new civic center study. See,

Cincinnati Enquirer, March 31, 1934.

Obstacles to Plan Implementation 173

proach.60

But we should not forget that the

problem of plan implementation was per-

ceived and defined as such because it

interfered with the aims of comprehen-

sive city planning, which dominated the

planning discourse during the second

quarter of the twentieth century. By the

1950s, however, comprehensive city

planning itself began to be identified

as a problem or potential problem by

critics, both inside and outside of the

planning profession, who questioned the

advisability of trying to direct almost

every aspect of city development on the

basis of "scientific" studies

made by experts, a concern that seemed to be

rooted in fears about the imposition of

uniformity and the loss of individual-

ity via the exercise of central

authority. As the president of the American

Institute of Planners, John T. Howard,

put it in 1955, "'comprehensive plan-

ning'-that is, looking at the entire

structure of society and seeking to coor-

dinate planned improvements in all the

parts that are not perfect... may well

be not only impossible, but dangerous to

attempt, because of the serious risk

of endangering that essential aim, the

dignity-which includes freedom-of

the individual."61

As a result of this shift in thinking,

the problem of plan implementation,

as it had manifested itself during the

1920s, 30s, and 40s, was superceded by a

new problem, the problem of plan

imposition, which yielded a discourse of

its own. Out of that discourse, critics

of comprehensive city planning began

to stress that planning ought to address

the desires and concerns of the com-

munity as determined, not by experts,

but by the individuals who lived and

worked in the city's various

neighborhoods and districts. This view, more-

over, ushered in a new mode of city

planning which tended to focus on indi-

vidual neighborhoods and districts, as

opposed to the city as a whole, and on

the facilitation of the maximum feasible

participation of all concerned parties

in the planning process.62

60. Hubbard and Hubbard, Our Cities

To-Day and To-Morrow, 37-32; Scott, American City

Planning Since 1890, 253-54.

61. John T. Howard, "The Planner in

a Democratic Society--A Credo," Journal of the

American Institute of Planners, 21 (Spring-Summer, 1955), 53.

62. Howard W. Hallman, "Citizens

and Professionals Reconsider the Neighborhood,"

Journal of the American Institute of

Planners, 25 (August 1959), 126-27;

Coleman Woodbury,

ed., The Future of Cities and Urban

Redevelopment (Chicago, 1953), 296-97, 427-38, 452;

Bettie B. Sarchet and Eugene D. Wheeler,

"Behind Neighborhood Plans: Citizens at Work,"

Journal of the American Institute of

Planners, 24 (1958), 187-88, 193-95;

Scott, American City

Planning Since 1890, 525, 599 629-31; Zane L. Miller, "The Role and the

Concept of

Neighborhood in American Cities,"

in Robert Fisher and Peter Romanofsky, eds., Community

Organization for Urban Social Change (Westport, Conn., 1981), 21-24; John Clayton Thomas,

Between Citizen and City:

Neighborhood Organizations and Urban Politics in Cincinnati

(Lawrence, Kans., 1986), 28; Fairbanks, Making

Better Citizens, 176; Robert A. Burnham,

"The Divided Metropolis:

Subdivision Control and the Demise of Comprehensive Metropolitan

Planning in Hamilton County, Ohio,

1929-1953," Planning Perspectives, 6 (January, 1991),

59-60.

ROBERT A. BURNHAM

Obstacles to Plan Implementation in the

Age of Comprehensive City Planning:

Cincinnati's Experience

During the period from roughly 1915 to

1945, when city planning became

institutionalized in the United States,

efforts to rationalize the city through

comprehensive city planning often met

with only measured success.1 This

stemmed, in part, from the nature of

planning itself in that planning, at one

level, was just that, planning, a vision

to guide the future development of the

city. Realizing the city plan

represented a very different matter, one that ne-

cessitated overcoming an often

mind-boggling array of obstacles: city council

members or administrators who lacked a

strong commitment to planning,

competing interest groups that viewed

planning from the perspective of their

own special concerns, and budgets that

did not match the aspirations of city

planners. Although troublesome, these

problems were not what one might

call structural, as were those presented

by non-municipal governing bodies,

which included the county, state, and

federal governments. Because their au-

thority did not derive from, or

superceded, city government, these units of

government could ignore the

recommendations of local city planning com-

missions when making decisions about the

design or location of county,

state, or federal improvement projects.

This created special difficulties for

city planning commissions trying to

uphold the basic principles of

comprehensive city planning, which sought to

secure the welfare of the city as a

whole while simultaneously viewing it as a

pluralistic entity composed of separate

but equal and interdependent parts,

groups, and systems. This perceived

interdependence meant that planning for

one aspect of the city's physical

development would necessitate a thorough

consideration of its relationship to all

others, or what planners called

"coordination," a key concept

in comprehensive city planning. Having

adopted such notions, city planners were

made uneasy by the thought of the

federal government or a county or state

government going forward with a pro-

ject affecting a particular city without

the advice of the local city planning

Robert A. Burnham is Assistant Professor

of History at Macon College.

1. For an assessment of the success of

city planning through the 1930s, see Robert A.

Walker, The Planning Function in

Urban Government (Chicago, 1941), ix, 133, 135-36, 153-

57.

(614) 297-2300