Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

DONALD A. HUTSLAR

"God's Scourge": The Cholera

Years in Ohio

Introduction

Between 5 August and 23 September 1834,

fifty-six residents of the small

Ohio village of Zoar, Tuscarawas County,

died of cholera. Zoar was the

home of a communal society of about

three hundred German Separatists, per-

sons who had differed with the doctrine

of the Lutheran Church and migrated

to the United States. During the summer

of 1834 a boat on the Ohio Canal

stopped at Zoar with one sick passenger,

Mr. Allen Wallace; he was carried

into the canal tavern (which is still

standing) and nursed by the Zoarites until

he died. He was buried in the village

cemetery. A few days later a woman

claiming to be his wife arrived to

retrieve some money and papers Wallace

was carrying. Wallace was disinterred

and the items were recovered from his

clothing. That night cholera broke out

in the village.l

The cholera epidemics of the nineteenth

century reflected a basic change in

society: industrialization, worldwide

commerce, massive urban centers, social

unrest, a migratory population. The

disease followed the ever-quickening

transportation systems, first the

waterways, then the road networks inland,

and finally the quick railroad lines of

mid-century. The disease was deadly in

its homeland of India due to poor

sanitation and a dense population in the

cities; in western Europe and the United

States, these two factors characterized

the industrial cities with the added

complication of rapid transportation.

During the early 1830s western Europe

struggled with political unrest and

unstable economic conditions,2 causing

thousands of immigrants to cross the

Atlantic Ocean at about the time the

cholera arrived in Europe. The United

States and Canada were aware of the

danger; quarantine of the ports of entry

Donald A. Hutslar, long-time curator of

history at the Ohio Historical Society, is a Ph.D. stu-

dent in architectural history at The

Ohio State University. He would like to thank Professor

Joan Cashin of The Ohio State University

Department of History for her assistance with this

article.

1. Hilda D. Morhart, The Zoar Story (Dover,

Ohio, 1967), 75. The disease may have been

spread through the communal dairy rather

than Zoar's water supply, a highly efficient, en-

closed system supplied by a hillside

spring on the opposite side of the river from the tavern.

The Zoarites discovered that liquids

were an effective treatment for cholera.

2. R. E. McGrew, "The First Cholera

Epidemic and Social History," Bulletin of the History

of Medicine, XXXIV (1960), 66-67.

Cholera Years in Ohio 175

was tried, but there were too many ships

and too many immigrants. Cholera

was in the coastal cities of both

countries by June 1832.3 The devastating

cholera epidemic of 1849 in the United

States was fueled by similar condi-

tions.

The succeeding epidemics in the United

States were driven more by internal

factors than external affairs. With the

exception of Cincinnati, only minor

outbreaks occurred in the state of Ohio

in 1854 and 1866. The work of

William Farr and John Snow in London had

established that the source of

cholera was usually contaminated

drinking water. The last pandemic in 1873

centered in the large cities in the

United States and proved that sanitation re-

mained the major public health problem.

Robert Koch, a German bacteriolo-

gist, isolated Vibrio cholorae in

the early 1880s. Physicians finally knew

what they had been fighting for fifty

years, though through trial and error

their regimen was basically

correct--fluids and rest.

Louis Chevalier states the proposition

that an epidemic emphasizes specific

behavior patterns which can be abnormal;

however, if the social structure can

cope with the abnormalities, then it

must be fundamentally stable.4 Despite

the rhetoric during the first two

epidemics, and a severe economic depression,

the social structure did remain stable.

Caution, not despair, greeted the epi-

demics after 1849, and sanitation became

the byword. John Gunn's popular

self-help medical book, Domestic

Medicine, summarized the approach: "Pure

air, good substantial living, temperance

and regularity of life in all things,

strict cleanliness and a tranquil

mind."5

Cholera and the Medical Community

"Shall there be evil in a city, and

the Lord hath not done it?" John W.

Scott, professor of Natural Philosophy

at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio,

opened his discourse "Delivered on

the Occasion of a Fast Observed in

Reference to the Approach of the

Epidemic" with these words from Amos

3:6. The year was 1833 and the epidemic

was The Cholera, "God's Scourge

for the Chastisement of the

Nations."6 Fifty years passed before Robert Koch

discovered the cholera bacilli, and during

those fifty years physicians as well

as the general public learned both to

treat and prevent the disease by empirical

methods. Cholera was still a scourge,

but not a "divine" scourge.

3. John M. Woodworth, M.D., editor, The

Cholera Epidemic of 1873 in the United States,

Executive Document No. 95, 43d Congress,

2d Session (Washington, D.C., Government

Printing Office, 1875), 563-93.

4. McGrew, "The First Cholera

Epidemic and Social History," 71.

5. John C. Gunn, Gunn's Domestic

Medicine, or Poor Man's Friend (Xenia, 1838), 725.

6. John Witherspoon Scott, The

Cholera, God's Scourge for the Chastisement of the Nations

(Oxford. Ohio, 1833), 1-3.

176 OHIO

HISTORY

To understand cholera and to appreciate

the difficulties confronting nine-

teenth century physicians, a description

of the disease is in order: Cholera is

an acute infection of the small bowel,

and its symptoms are diarrhea, vomit-

ing, muscle cramps, dehydration, and

collapse. The recommended treatment

is rehydration with a solution

containing glucose, sodium chloride, sodium

bicarbonate, and potassium chloride.7

The solution replaces lost water and

electrolytes. Quick treatment is

absolutely essential. Individual responses to

cholera vary greatly, from death in a

few hours to total recovery in three to

five days. The death rate can be 50

percent in untreated cases, but is less than

one percent with prompt fluid treatment.

Recovered patients have a natural

immunity, although a few will become

carriers through chronic gallbladder

infection. Because of the bacilli's

sensitivity to gastric acid, some nineteenth

century high-acid treatments worked.

Several modern medicines, such as

tetracycline, lessen the severity of the

symptoms but no long-term vaccine is

available. Cholera is now endemic in its

old haunts of India, Asia, Africa,

the Middle East, and Central and South

America, and localized outbreaks are

possible anywhere in the world. The last

outbreak in the United States was

in Louisiana in the summer of 1986.8

For most of the nineteenth century

medical practice was divided into several

areas: domestic medicine, or self-care,

which was often supervised by the

woman of the household; academic

medicine, practiced by the formally trained

physician; and folk medicine, conducted

by the lay-healer.9 Medical texts

written for the general public abounded

in the eighteenth and nineteenth cen-

turies, the best known being William

Buchan's Domestic Medicine which

went through at least thirty editions in

the United States.10 Mid-century edi-

tions contain the chapter

"Malignant Cholera-Cholera Morbus," composed

of many physicians' opinions regarding

treatment of the disease.

John C. Gunn's work of 1832, also

entitled Domestic Medicine, replaced

Buchan's book in popularity by

mid-century. A tenth edition, published in

Xenia, Ohio, in 1838 contains an extra chapter on "Epidemic

Cholera," trac-

ing the history of the disease and

giving "the conflicting opinions of the most

7. Sharp Merck and Dohme Merck, Merck

Manual (New York, 1986), 110.

8. Twenty-Third Joint Conference on

Cholera, U.S.-Japan Cooperative Medical Science

Program, Williamsburg, Virginia,

November 10-12, 1987, "Environmental

Aspects of Vibrio

Cholerae in Transmission of

Cholera," 81-82. Microfiche. Eighteen persons were infected.

none died. Crabs, shrimp, and raw

oysters from the Gulf of Mexico caused the outbreak.

Cholera is endemic in the Gulf. Another

study, "Environmental Aspects of Virgio Cholerae,"

Ibid., 31-32, suggests that V. Cholerae

is a symbiont of plankton. Other intestinal diseases show

symptoms very similar to cholera;

Salmonella (food poisoning) and Escherichia coli (severe di-

arrhea) are two common examples. It is a

logical assumption that not all illnesses and deaths

attributed to V. cholerae were caused by

that bacillus.

9. Paul Starr, The Social

Transformation of American Medicine (New York, 1982), 32-55.

10. William Buchan, Domestic

Medicine; or, A Treatise on the Prevention and Cure of

Diseases (Waterford, N.Y., 1797). Several editions of Buchan are

in the Ohio Historical

Society Library.

Cholera Years in Ohio

177

distinguished physicians, and their

treatment of cholera."11 Gunn believed

that fear of cholera was as dangerous as

the disease itself; therefore religion

was a valuable ally in prevention and

treatment.12 He reflected the Protestant

view of Divine Providence, that illness

and misfortune (God's Scourge) were

the rewards of moral error. This theme

appears most often in the first cholera

epidemic in the early 1830s, and it

reappears with less emphasis in 1849.

Beginning in 1849, and predominating in

later epidemics, the practical prob-

lems of health and sanitation for all

groups in society overshadow metaphysi-

cal considerations.

Professional physicians in the United

States were strongly influenced by

Benjamin Rush at the University of

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and his con-

cept of one disease in the world and one

treatment, copious bleeding together

with emptying the stomach and bowels

with emetics and cathartics.l3 The

cathartic was calomel (mercurous

chloride) which was often given in large

doses. Dr. Henry Yandell used up to 120

grains of calomel and repeated the

dose every two to three hours: "A

frequent repetition was, however, not often

demanded, the patient either relieved or

dead in a few hours."14 Buchan was

positive that calomel cured forty-nine

of fifty cases. Calomel had many un-

pleasant side effects, other than

mercury poisoning and death, including heavy

salivation; Buchan commented, "I

say, better a sore mouth than a cold grave."

Many prominent physicians endorsed the

use of calomel, including Daniel

Drake, the most influential physician in

the American West.15

Calomel and other mineral drugs and

heroic treatments were used by the

formally trained, or allopathic,

physicians. Allopathists believed that reme-

dies should produce effects opposite to

those of the diseases under treatment.

Opposed to the Allopathists were the

Homeopathists, a small but active

group of physicians who felt that the

remedy for a disease must produce the

disease's symptoms in a healthy person.

Their success with cholera was,

needless to say, limited. Other schools

of medicine existed, a few quite legit-

imate. (Ohio city directories during the

mid-nineteenth century usually listed

physicians according to their schools of

practice.) Depending upon the con-

temporary sources, one-third to one-half

of Ohio's population were

Thomsonians.16 Samuel

Thomson's botanic system was simplicity itself:

Cold caused disease and heat was the

remedy. Thus, Thomsonian doctors

11. Gunn, Domestic Medicine, 711.

12. Ibid., 725. Gunn felt it was best

"at all times and under all circumstances, to place a re-

liance upon Almighty God."

13. Starr, Social Transformation of

American Medicine, 42.

14. Buchan, Domestic Medicine, 282,

284-85.

15. Ibid., 288. As late as 1912, in the

fifteenth edition of The Fenner Formulary, calomel is

still listed as a purgative or

"alternative," a drug used empirically to change the course of an

ailment. B. Fenner, The Fenner

Formulary (Westfield, N.Y., 1912), xv. "Calomel,"

"Cholera."

16. Starr, Social Transformation of

American Medicine, 51.

178 OHIO HISTORY

quickly acquired the nickname

"Steam Doctors." A rival botanicomedical

group known as the Eclectics absorbed

the Thomsonian Medical College in

Cincinnati. The Eclectics, led by

Wooster Beach, author of American

Practice of Medicine in 1833, rejected the use of minerals, especially

mercury.

Dr. John Snow's famous study of cholera

cases among the users of the

Broad Street pump in the Soho district of

London in 1854 finally established

how cholera spread. Disinfectants and

waste disposal became as important as

medical treatment. Snow's findings

countered the prevailing opinion that

cholera was a poison in the air that

entered the body through the respiratory

passages, the conclusion of a report by

the Royal College of Physicians in

the same year.17 Once the

method of transmission had been established,

cholera became less frightening because

it could be physically controlled

through the environment, an approach

anyone could understand.

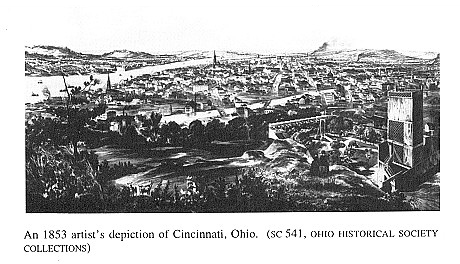

The Cholera in Ohio

Five cholera epidemics struck Ohio in

the nineteenth century, with

Cincinnati as the focal point of them

all because of its location on one of the

main routes of transportation in the

United States, the Ohio River. This arti-

cle will focus on the small city of

Xenia because it proved to be an excellent

source of information. Furthermore,

Xenia did not have some of Cincinnati's

problems; it was not near a navigable

water course or a main road. Therefore,

the community had no cholera during the

first epidemic in the 1830s. By

1845, however, the city was connected to

Cincinnati by a railroad line and

cholera arrived in 1849 in a

once-isolated community. Sources for this article

include Xenia City Council records for

the 1830s, local newspapers of the

1830s and 1840s, mortality schedules,

and reports by the health officers in the

1860s and 1870s.18

Xenia, the "seat of justice"

of Greene County, was surveyed and platted in

the autumn of 1803. The name Xenia is

from the Greek word meaning hos-

pitality. It was suggested by Robert

Armstrong, a Presbyterian minister, dur-

ing a meeting to name the new county

seat.19 Xenia was incorporated as a

village in 1817 and as a city in 1834;

its population was about one thousand

in 1820 and only fourteen hundred in

1830, according to the censuses. Many

of the first settlers in Xenia and Xenia

Township were veterans of the

Kentucky Militia and had known the area

during the frontier Indian wars of

17. N. R. Barrett, "A Tribute to

John Snow, M.D., London 1813-1853," Bulletin of the

History of Medicine, XIX

(1946), 531.

18. The Xenia city documents are located

in the Wright State University Library, American

History Research Center, Local

Government Records, Dayton, Ohio.

19. Michael A. Broadstone, ed., History

of Greene County, Ohio, 2 vols. (Indianapolis,

1918), vol. 1, 104; Chapter V.

"County Organization."

Cholera Years in Ohio

179

the 1770s and 1780s. (Old Chillicothe,

the home village of Tecumseh, was

about three miles north of Xenia.) Xenia

remained an out-of-the-way rural

market town until the arrival of the

Little Miami Rail Road in 1845 connect-

ing it to Cincinnati and, later,

Sandusky.

During the early 1830s the Ohio Canal,

from Cleveland to Portsmouth,

was the main route connecting Lake Erie

and the Ohio River. Construction

of the National Road reached halfway

between Wheeling and Columbus. A

road network did connect most

communities, but many roadbeds were unim-

proved, making travel difficult during

inclement weather. The Ohio River

remained the principal transportation

route connecting the western states with

the southern and eastern states. By 1849

both the Miami and the Ohio canals

connected Lake Erie and the Ohio River

through central and western Ohio.

The Little Miami Rail Road ran from

Cincinnati as far north as Sandusky,

Erie County, on a regular schedule. A

good road network made travel easier

for wagons and carriages. Immigrants and

travelers could reach the center of

the state in a day or two, and as a

consequence the entire state was susceptible

to an epidemic such as cholera.

The Cholera Epidemic of 1832-33

The first cholera epidemic took hold in

Cincinnati, but it only made short

excursions in the interior of the state.

Columbus had no known cholera

deaths in 1832, compared to several

hundred in Cincinnati. The Ohio Canal

brought the first cholera victim to

Franklin County in June 1833; one hun-

dred deaths were officially reported in

Columbus in July.20 Dayton had one

brief encounter with the epidemic when a

group of twenty-four German im-

migrants arrived in town in June 1832.

Nine died as well as two of the

nurses caring for them. No other cases

were reported.21 For whatever reason,

the Xenia Free Press did not

publish this information until 3 January 1833.

The Free Press published a

lengthy letter, dated 26 October 1832, by Daniel

Drake containing advice on prevention

and treatment of cholera-fluids,

calomel, rest. If the patient was near

death, the Thomsonian plan could be

tried. (Drake was having nothing to do

with the Steam Doctors.)22 The Free

Press reported on the cholera throughout the United States

during 1832 and

20. Jonathan Forman, M.D., The First

Cholera Epidemic in Columbus, Ohio (1833) (New

York, n.d.; reprint, Annals of

Medical History, New Series 6, No. 5), 425. The census returns

of 1830 gave Columbus a population of

2,437. The Columbus Health Board attributed the

spread of cholera to intemperance and

eating too much celery! Fresh vegetables were often

blamed for causing cholera (and "night

soil" was used as a fertilizer).

21. J. D. B. De Bow, ed., Mortality

Statistics of the Seventh Census of the United States, 1850,

Executive Document No. 98, 33d Congress,

2d Session (Washington, D.C., 1855), 587.

22. Drake thought a patient treated by

the "Thomsonian plan" would usually die. His letter is

printed in full in Gunn, Domestic

Medicine, 753-57.

180 OHIO HISTORY

1833 without mentioning a single case in

Xenia, although advertisements ap-

peared for disinfectants, such as

chlorides of lime and soda, and for burgundy

pitch plasters and alcoholic camphor as

preventatives.23 A local drug store

advertised Dr. Zolicoffer's

"Anti-Cholera Mixture," supposedly known only

to a few apothecaries in the United

States, in the summer of 1833.24

Following the epidemic of 1832-33, the

Xenia City Council prepared to de-

fend the city against a future outbreak

of the disease. On 9 August 1834,

they appointed a Board of Health and

proposed an ordinance restricting hogs

from roaming in the streets. On 16

September the council ordered the pave-

ment and gutters to be cleaned around

the public well on courthouse square

and heard a proposal for the removal of

all horse racks (hitching posts).

Ordinances banning hogs and horse racks

became official on 15 April 1835.25

The council closely monitored the

cleanliness of the public cisterns and wells

during the latter part of the 1830s.26

The prevention of cholera through

sanitary measures was taken seriously

throughout Ohio, but local conditions

were often impossible to overcome. A

city such as Cincinnati was simply too

large and its residents lacked a cohe-

siveness of purpose. The Dayton City

Council passed an ordinance on 17

December 1836 requiring physicians,

canal boat captains, boarding house

keepers, and owners of taverns and coffee

houses to report all cases of cholera,

or any malignant disease, to the mayor

in writing within twelve hours of dis-

covery.27 Many physicians in

Cincinnati, as elsewhere in major cities, kept

detailed records of their cases. Xenia

physicians probably kept records, but

none have been found. Medical

statistics, as a formal practice, had to wait

until the 1848 epidemic in England and

the work of William Farr. Farr's de-

tailed analysis of disease, death, and

demographics laid the factual basis for

sanitary reform by governmental action.

The Cholera Epidemic of 1849

"Where this destroyer will stop, or

when, none of us know. Almost entire

families are smitten down in our happy

land as if a judgment was upon us."28

Thus the editor of the Dayton

Tri-Weekly Bulletin related the fate of the

Skinner family of Wapakoneta. Mr. and

Mrs. Skinner and a daughter had

23. Xenia Free Press, 27 October

1832.

24. Ibid., 3 August 1833.

25. Xenia City Council Minutes, 9 August

1834 and 15 April 1835, Local Government

Records, Wright State University

Library, Dayton, Ohio.

26. One cistern contained 11,000 gallons

of water, two cisterns contained 6,750 gallons

apiece. Six wells with pumps were added

in 1840. Xenia City Council Minutes, 25 September

1840.

27. The Dayton Tri-Weekly Bulletin, 22

June 1849.

28. Ibid., 2 July 1849.

|

Cholera Years in Ohio 181 |

|

|

|

come to Dayton to visit another daughter and son. Perhaps Mr. Skinner had a premonition of death before leaving home, for he had settled his business af- fairs in Wapakoneta. He died soon after reaching Dayton, and his wife died a few hours later. The son and the visiting daughter died in the next two days, followed by two children of the married daughter-six deaths in the same fam- ily, from the same house, in five days. The newspaper's editor extolled the virtues of the Skinner family, and no doubt the family did represent many middle-class values of the period. Unfortunately, the disease of the allegedly intemperate, impious, and filthy could be found among the middle-class; it was losing its reputation as a judgment on the vices of society. The 1848 epidemic in Europe reached New York and New Orleans in December of that year, carried by French and German immigrants.29 The dis- ease followed the waterways to the interior, becoming pandemic during the summer. The following year, 1849, would see the epidemic at its worst. Because of the severity of the epidemic, mortality statistics were compiled with the population census of 1850.30 They bracket one year, June to June, 1849 and 1850, and record the worst months of the epidemic: 37,034 cholera deaths were reported. For comparison, during the same period thirty-three thousand people died from tuberculosis, twenty thousand from dysentery, and

29. Woodworth, The Cholera Epidemic of 1873, 608-11. 30. De Bow, Mortality Statistics of the Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, 1 June 1849 to 1 June 1850. |

182 OHIO HISTORY

between ten and thirteen thousand from

scarlet and typhoid fevers, pneumonia,

and dropsy. Ohio was divided into six

reporting districts, and the majority of

cholera deaths, almost four thousand,

occurred in the southwest district which

included Cincinnati, Dayton, and Xenia,

while about one thousand occurred in

the midwest district which included

Columbus. The other four districts to-

taled twelve hundred deaths.31

By this time the general public had

become aware that cholera could not be

transmitted through the air, the main

theory of the 1830s. This awareness

was reinforced by constant reminders in

the newspapers even during the height

of the epidemic, as on the editorial

page of the Dayton Tri-Weekly Bulletin,

22 June 1849. In Xenia, a medium-size

city in the late 1840s, with a popula-

tion under five thousand, the local

newspaper, the Xenia Torch-Light, kept

abreast of the cholera epidemic

throughout the country as well as locally.

The first death occurred in Xenia on 17

May, 1849, not a local resident but a

visitor from Circleville. Cholera

reached Kentucky, then Indiana, and, by 24

May, had entered Cincinnati. The Torch-Light

editorialized in June that "The

disease is much less dreaded now,"

and "Think for yourself and act for your-

self, and fear not the cholera-but if

sick, send for a physician in whom you

have confidence." This was good

advice, mitigated, perhaps, by the adver-

tisement of a Mr. Thomas, a local

daguerreotypist, who would take the like-

nesses of the sick and the dead "on

the shortest notice."32

All the known deaths from cholera among

Xenia citizens occurred during

the months of July and August, following

the Torch-Light's advice. But ru-

mors of deaths abounded.33 In

Dayton, a man from Cincinnati supposedly

stopped at the Farmers' and Mechanics'

Hotel, owned by J. A. Kline, where

he died that night, 18 May 1849.

According to the Lexington Observer and

Reporter, 18 July, the disease spread through the hotel and to

nearby towns.

Then, on 19 May, a man from Xenia ate at

the hotel, caught the disease then

returned to Xenia, where he caused fifty

deaths.34 These stories, confused and

not true, are indicative of the rumors

and fear of the disease prevalent during

the spring of 1849. Both the Xenia and

Dayton papers mention the deaths in

Kline's hotel, with Kline himself dying

on the 13th of June. No mention,

however, appears in any of the Torch-Light

newspapers of fifty deaths in

Xenia in the latter part of May or in

June. The Torch-Light of 28 June re-

31. With a population over 112,000,

Cincinnati was a true metropolis compared to other Ohio

cities; Columbus and Cleveland had

populations slightly over 16,000. Cincinnati had a death

rate at least triple that of the latter

cities.

32. Stanley B. Burns, M.D., Sleeping

Beauty: Memorial Photography in America (1839-

1883) (New York, 1990). This is a book of pre- and postmortem

images, several dated 1849.

33. Kathleen A. Taylor, "Cholera

Deaths Reported in the Torch-Light. 1849-1854," TMs.

Greene County Public Library, Xenia,

Ohio.

34. J. S. Chambes, M.D., The Conquest

of Cholera (New York, 1938), 224-25; Woodworth,

The Cholera Epidemic of 1873, 611.

Both sources quote the Lexington Observer and Reporter,

18 July 1849.

Cholera Years in Ohio

183

ported that five of the Irish laborers

working on the Columbus and Xenia rail-

road line had died, and that Dr. Samuel

Martin of Xenia had turned part of his

stable into a makeshift hospital for the

homeless Irishmen and had given

them free care.35 The first

Xenian to die was Mrs. Hilliary Neal, who expired

on 12 July at the age of twenty-eight;

she also had the honor of being the

first resident of Woodland, the new

cemetery.36 Sexton David B. Cline,

whose reminiscence was later published

in the Xenia Gazette, recalled that he

did not have a grave dug for Mrs. Neal

because it was almost impossible to

find grave diggers during the epidemic.37

During July and August, the Torch-Light

carried many columns about the

epidemic in Ohio: The cholera had

reached Columbus and the State

Penitentiary, Dayton, Springfield,

Piqua, Urbana, Eaton, Tiffin, and

Sandusky.38 Only one train

ran daily between Cincinnati and Sandusky, and

that one delivered mail.39 Advertisements

for "cholera specifics" filled the pa-

pers. People would try any remedy at the

height of the epidemic. The Torch-

Light editorialized that the users of these questionable

remedies "would make

it profitable to their heirs-in-law, by

having their lives insured."40

"Greenough's Mixture" sold by

the quart, and many who used it would never

again require medicine (a journalistic

"dark humor" appeared during the epi-

demic).

The small village of Clifton, northeast

of Xenia, had at least fifteen deaths,

perhaps as many as forty. The hotel

(still standing) used water from a street

well. A traveler died in the hotel; six

more expired in the same building; two

persons died across the street; several

more died in the neighborhood.41 (The

Torch-Light of 13 September, however, claimed that the reports of

"depopulation" were greatly

exaggerated, that only fifteen deaths occurred dur-

ing the epidemic.) In any event, the

public well collected water from the

limestone strata, but it also served as

a drain pit for nearby privies, barn

yards, kitchen waste, and microscopic

bacteria.42

35. George F. Robinson, History of

Greene County, Ohio (Chicago, 1902), 126. The de-

ceased Irishmen were buried near the

railroad embankment between Xenia and Cedarville,

not in a cemetery.

36. R. S. Dills, History of Greene

County (Dayton, 1881), 433-35. A typographic error

places the epidemic in 1848; later

county histories copied the error.

37. Ibid., 433-34. The Xenia City

Council hired four men to assist Cline; they were expected

to lay out the corpses, take them to the

cemetery, and bury them for "four dollars a head."

38. Xenia Torch-Light, 9 August

1849. Eaton, county seat of Preble County, had 101 occu-

pied and 84 vacant houses at the

beginning of August.

39. New Historical Atlas of Erie

County, Ohio, "Visitation of the Cholera in 1849, 1852,

1854" (Philadelphia, 1874), vi.

40. Xenia Torch-Light, 9 August

1849.

41. Dills, History of Greene County, 676-78.

42. On the south side of Clifton is a

deep gorge formed by the Little Miami River. Local

residents placed their privies near the

gorge, thinking the cesspits would drain into the river.

Wells were dug north of the gorge and

the privies. Unfortunately, the rock strata did not in-

184 OHIO HISTORY

Despite the severity of the epidemic,

Xenia lost about eighty-five residents,

a small proportion of its population,

approximately 1.3 percent, compared to

other Ohio communities; Cincinnati, for

example, lost 4.3 percent of its resi-

dents. Xenia's citizens took the warning

about cleanliness and public sanita-

tion seriously. The Torch-Light carried

many articles on these topics during

the summer, as did local newspapers

throughout the state. It is unfortunate

that the city council minutes are

missing for this period; given the evidence

of the council's activity during the

epidemic of 1866, they had learned by ex-

perience.

The Cholera Epidemic of 1854

The United States did not free itself of

cholera following the large outbreak

in 1849, and small, isolated incidents

recurred in Ohio. Thirty deaths occurred

in Sandusky, Erie County, during the

summer of 1852.43 A woman carried

the disease to Dayton, where she

recovered, but six residents of the house in

which she lived died; an estimated forty

deaths eventually resulted from this

incident.44 Immigration ports

as far distant as Quebec and New Orleans had

periodic outbreaks during 1852 and 1853.

In New York during the month of

November 1853, twenty-eight immigrant

ships arrived containing some

eleven hundred deceased victims of

cholera. Oddly, however, the first recog-

nized case of cholera did not occur in

New York but in Chicago in April

1854. The second recognized case

occurred in Detroit in May. The immi-

grants landed, then quickly traveled

west before they succumbed to the disease.

The epidemic began in New York in June.45

The Xenia newspapers devoted little

space to local conditions because the

cholera was not particularly severe in

Ohio in 1854. The Torch-Light carried

death notices from the small village of

Bowersville in the southeast corner of

Greene County, where six members of the

Moon family, five of the Shaner

family, and five of the Reaves family

died during July.46 There is no evidence

of how the cholera arrived or how it

spread so quickly through the three fami-

lies.

A few Ohio city directories of the 1850s

(Xenia did not have a directory un-

til 1870) do reveal a significant change

in public services, such as the advent

of the plumber. Cleveland installed a

new water system in the late 1850s

cline towards the gorge but towards the

wells. As a consequence, many residents died even

though the privies and wells had been

placed in a logical alignment. Ibid., 667.

43. Atlas of Erie County, vi.

44. Woodworth, The Cholera Epidemic

of 1873, 634.

45. Ibid., 634-35.

46. Taylor, "Cholera Deaths

Reported in the Torch-Light," 5. Bowersville was an isolated

farming community in 1854. The families

are not adjacent to one another in the 1850 census.

|

Cholera Years in Ohio 185 |

|

which had enough pressure for a fountain on Public Square-an added attrac- tion for the Ohio State Fair visitors in 1859. B. P. Bower, a "practical plumber," advertised that he had been licensed by the city commissioners to do work connected with the new waterworks, and that he could also install complete bathrooms in private residences.47

The Cholera Epidemic of 1866 During the early 1860s cholera again became pandemic in India. Pilgrims going to Mecca carried the disease to the Mediterranean, while English, French, Austrian, and Italian steamships transported the pilgrims to Alexandria. These same ships also carried passengers up the Atlantic coast so that cholera arrived in Paris by the summer of 1865. Beginning in April 1866, cholera-infested ships docked at New York from Liverpool, Hamburg, Antwerp, Le Havre, and London. Due to a strict disinfection policy by the Metropolitan Board of Health, the disease was held in check until July. Cholera joined the Army of the United States on Governor's Island in July, and subsequently spread throughout the country by steamship and railroad lines carrying troops to new posts following the Civil War.48 The death rate in the army remained quite low due to strict quarantine and sanitation, about

47. Directory of the City of Cleveland, 1859-60 (Cleveland, 1859). 48. Woodworth, The Cholera Epidemic of 1873, 664-82. |

186 OHIO HISTORY

250 in 1866 and 230 the following year.

The epidemic continued to be most

severe in the Mississippi Valley: 8.500

died in St. Louis compared to 1,406

in Cincinnati.49

The number of deaths in Xenia must have

been very low in 1866 because

the four standard county histories

contain no references at all to the epi-

demic-nor the 1873 epidemic, for that

matter.50 The report of the Xenia

Health Officer is missing, but his ledger

does exist.51 Beginning in April

1866 every building and lot in Xenia was

inspected, a total of 835 properties,

correction orders issued when necessary

for bad sanitary conditions, then re-in-

spected one or more times. Xenia had

four wards centered on the Public

Square. The First Ward, to the

northwest, contained the fewest residences and

businesses, and, aside from a few

"privy vaults" which needed cleaning, it was

in good condition. In the Second and

Third wards on the south side of town,

as many as one out of three properties

needed correction. Typical sanitation

problems included filled privy vaults

(most common), dirty or flooded cellars,

garbage thrown into the streets or house

lots, and unclean pig pens.52

The Health Officer and the City Council

certainly displayed great energy

and resolve in cleaning up Xenia.

Non-compliance notices were issued which

necessitated re-inspections, but the

citizens must have responded; no reports

of a calamity exist, and the Health

Officer could report 1867 as an unusually

healthy year.53

The Cholera Epidemic of 1873

The last cholera pandemic in the United

States began in New Orleans in

February 1873, although the disease had

been prevalent in central and eastern

Europe for at least three years. It

devastated the northern provinces of India,

and pilgrims to Mecca carried the

disease to the Persian Gulf region. The dis-

ease moved into northwest Europe and

England, carried by migrants, travelers,

and members of the military, and

immigrants from Hamburg, Bremen, and

Liverpool brought the cholera to New

Orleans.54 The epidemic spread rapidly

49. De Bow, Mortality Statistics of

the Seventh Census, 672-73.

50. The bound volumes of the Xenia

Torch-Light, which cover the Civil War years as well as

the year 1866, are missing from the Ohio

Historical Society Library.

51. "Examination of Premises,

Xenia, Ohio, 1866-1871." AMs. Greene County Public

Library, Xenia.

52. Ibid. Entries are by date, from 26

April to 17 May 1866 and a re-inspection in August.

53. "Annual Report of the Health

Officer, Xenia, April 13, 1868." "Examination of

Premises." Xenia City Council

Minutes, Local Government Records, Wright State University

Library, Dayton, Ohio. As an interesting

sidelight on the problems of urban sanitation, the

number of pigs and hogs in Xenia was

tabulated in May 1870; there were 496 swine in the four

wards. Horses, cattle, and chickens were

not counted but must have been numerous. These

domestic animals were common in Ohio's

small towns until the end of World War II.

54. Woodworth, The Cholera

Epidemic of 1873, 75-90,

109-11.

Cholera Years in Ohio 187

northward along the Mississippi and Ohio

rivers and followed the rail lines

and roads inland. The disease reached

Cincinnati on 27 May and Columbus

on July 4th. Over seven thousand victims

died in 1873, over seven hundred

in Ohio.55 The United States

Senate and House of Representatives passed a

joint resolution on 25 March 1874

requiring a report on the causes of epi-

demic cholera. President Grant forwarded

the document to the House and

Senate on 12 January 1875.

The Cholera Epidemic of 1873 in the

United States is a classic work of

medical reporting and health statistics.

All the epidemics in the United States

are reviewed, many detailed case studies

given for the 1873 epidemic, and a

bibliography of 314 pages is included.56

Dr. Halderman, physician at the

Ohio State Penitentiary, submitted a

report for Columbus including a map

showing the deaths in the city.57 The

City of Columbus took no sanitary

measures during the approach of the

disease, whereas the penitentiary took ev-

ery precaution. Sixty-nine persons died

in Columbus, twenty-one additional

died in the penitentiary. The cholera

struck in the lowlands along the Scioto

and Olentangy rivers which contained

railroad bridges, the waterworks, and

numerous factories and tenements for

workers. Many private wells became

contaminated from overflowing drainage

sinks and privy vaults.58 The toilets

on the trains emptied directly on the

tracks and so it is possible a railroad

passenger brought the cholera to

Columbus. The cholera-infected diarrhea

found its way into a well or the river.

Once established, the infection could

circulate from the privies and sewers to

the river and back into the water

system through the waterworks. The first

cholera victim lived in a house

near the railroad bridges over the

rivers.59

In contrast to Columbus and Cincinnati,

the Health Officer of Xenia could

report that no epidemic disease had been

reported in the city for the entire

year.60 No mention of cholera

appears in the Torch-Light during the summer

months of 1873, just small reminders on

the importance of cleanliness. The

efforts of the City Council and the

Health Officer during the previous years

had been rewarded.

Cincinnati was less fortunate. Author

Lafcadio Hearn, who worked as a re-

porter for the Cincinnati Daily

Enquirer, wrote a column about the appalling

sanitary conditions in Cincinnati,

"The Balm of a Thousand Water-

55. Ibid., 34-35.

56. Among the list of contributors to

the report are 103 physicians from Cincinnati and

Hamilton County. J. S. Chambers' book, The

Conquest of Cholera, is a summary of Ex. Doc.

No. 95 augmented with newspaper

accounts.

57. Woodworth, The Cholera Epidemic

of 1873, 360-68.

58. Ibid., 361.

59. Ibid., 363-63.

60. Xenia City Council Minutes,

April, 1875.

188 OHIO

HISTORY

Closets."61 High water

had cleaned out four miles of sewers and the contents

lay in sink-holes on the west side of

the city: "The effect is terrible." By

this time, the Cincinnati City Council

as well as the residents knew how to

protect themselves from cholera;

however, sewerage systems cost tens of

thousands of dollars and the United

States was gripped by an economic de-

pression, the Panic of 1873.

Public Health and Sanitation

From archaeological evidence, it is

apparent that the ancient civilizations

from the Near East to the Indus River

Valley understood basic hydraulics and

sanitary practices and provided

themselves with clean drinking water and sew-

erage systems. Baths, flushing latrines,

and sewers date to the third millen-

nium B.C.62 The Romans were

very conscious of public health and sanita-

tion and carried similar facilities to

every part of their Empire. Many of the

Christian monasteries adopted these

facilities. Christchurch Monastery in

Canterbury, England, is a textbook

example with its complete water and sew-

erage system constructed in 1150.

Due to its sanitary practices, the

monastery escaped the Black Death in

1349.63 Most Ohio towns could not

boast such a system five hundred years

later.

The importance of sanitation and

cleanliness to public health was under-

stood by many public officials through

the centuries following the Roman

Empire: The gradual increase in

population, the growth of urban centers with

compacted, inadequate housing for

laborers, improved land and water trans-

portation-and a myriad of local

complications, religious, political, commer-

cial, economic-often made the best

efforts to supply clean water or provide a

sewerage system ineffectual.

Books on sanitation became available to

Ohioans during the first quarter of

the nineteenth century.64 Probably

many Ohioans did not know or care about

clean drinking water or waste disposal

during this period, however, because

61. [Lafcadio Hearn], "Hold Your

Noses! The Balm of a Thousand Water-Closets,"

Cincinnati Enquirer, 11 May 1874, p. 8.

62. Lawrence Wright, Clean and

Decent: The Fascinating History of the Bathroom & the

Water Closet (Toronto, 1967), Chapter 1, "Man Becomes

House-Trained." Another well-re-

searched overview of sanitation is

Reginald Reynolds' book, Cleanliness & Godliness (New

York, 1946).

63. Wright, Clean and Decent, 26.

The original plans are extant for this ingenious system.

64. Abraham Rees, The Cyclopedia: or,

Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and

Literature (Philadelphia, n.d.), s.v. "Cholera"; John

Beckmann, A History of Inventions,

Discoveries and Origins, trans. William Johnston, ed., William Francis and J. W.

Griffith

(London, 1846), s.v. "Paving of

Streets," "Quarantine." Beckmann wrote several essays on

public health and sanitation, derived

from Classical sources, in the latter eighteenth century.

Rees compiled similar material from the

Encyclopaedists; the American edition of his

Cyclopedia, published about 1815, contains a description of

cholera.

Cholera Years in Ohio

189

outside the large cities of the cast

coast, the United States was still a predom-

inately agrarian society, and Ohio had

thousands of acres of unsettled land.

The city of Xenia did not have a public

waterworks in the 1830s, only

wells and cisterns which served both the

residents and the fire department. Of

course, the city did have numerous

private wells and cisterns. The "Town

Engineer," a post created by the City

Council in the spring of 1839, took

charge of the wells, cisterns, and pumps

belonging to the city, and kept them

clean and in repair.65 A

modern water system with two pumping stations was

constructed in 1887, but a municipal

sewerage system had been constructed

earlier because the City Council

recommended disinfecting the sewers with a

device called the "Duncan

Disinfecting Chest" on 23 July 1883. Municipal

water works remained rare in Ohio until

mid-nineteenth century. Cincinnati

had a privately funded pumping station

in operation in the early 1820s, the

first in Ohio.66 As for waste

disposal, the residents of Cincinnati, as in most

communities, including Xenia, simply

utilized the streets, letting hogs and

rainfall dispose of the excess; human

waste drained into cesspools or was

conveyed to a river. Xenia succeeded in

controlling the problem. If they did

nothing else, the cholera epidemics,

particularly those of 1832-33 and 1849,

revealed the public health problems

inherent in urban centers.

Many communities in Ohio passed health

codes during the cholera years,

but their effectiveness depended upon

enforcement by local government and

local funding. The Civil War bolstered

the efforts for health reforms because

of the large number of wounded and

disabled soldiers returning to all commu-

nities. Health Commissions and Sanitary

Fairs became common throughout

the northern states during the latter

part of the war. Afterward, the Federal

Government constructed hospitals as well

as "homes" for disabled veterans

and for children orphaned by the war,

with Xenia receiving the "Ohio

Soldiers' and Sailors' Orphans'

Home."67

S. F. Forbes, public health officer for

the city of Toledo, wrote one of the

finest reports in Ohio in 1866. Forbes,

who recognized that public health

measures could not keep pace with the

rapid growth of urban, industrial cen-

ters, emphasized the importance of

sewerage, paved streets, and a clean water

supply to reduce all contagious diseases

which "kill more persons than does

65. Xenia City Council Minutes,

April, 1839.

66. Cincinnati Directory Advertiser

for 1832 (Cincinnati, 1832), 187-88; Woodworth,

Cholera Epidemic of 1873, 349. Fourteen miles of pipe carried the water through

the city.

Unfortunately, the waterworks

distributed cholera-infested Ohio River water to its customers.

It was the practice of the steamboat

lines to wash bed linen both on board and on shore, and the

government report on cholera of 1875

credits this practice with the widespread outbreaks of

the disease in Cincinnati.

67. Xenia City Council Minutes, "Report

of Health Officer," 13 April 1868. A. H. Brundage,

the Health Officer, commented: "The

vast hospitals of the late war called forth the resources

of hygiene, and demonstrated the

life-saving power of preventive measures."

190 OHIO

HISTORY

the cholera."68

Among the excellent technical literature

which became available in the third

quarter of the nineteenth century is

George Waring's 1876 book, The Sanitary

Drainage of Houses and Towns. While Waring erred on the dissemination of

cholera (he thought it could be carried

by sewer gas as well as water), his ad-

vice on household sanitation was

excellent and covered all the "modern" de-

velopments such as flush toilets, bath

tubs and showers, wash basins, water

traps, and hot and cold tap water. These

technical achievements were ideas

whose time had come: American urban

society had developed to a point that

sanitary measures had become a

necessity, not a luxury.69

Conclusion

Cholera was a dangerous disease in a

century of dangerous diseases. It had a

strong psychological impact,

particularly during the epidemics of the 1830s

and 1840s. Its progression from India

into Europe and the British Isles could

not be prevented. Americans, informed by

their newspapers and immigrants

about the failure of quarantines to halt

the spread of the disease and of the in-

ability of physicians to cure the

victims, knew that cholera would eventually

come to the United Sates. Ships could be

quarantined at the major ports of

entry in Canada and the United States,

but many other ports existed for the

steady stream of immigrants.

The symptoms of cholera were not

progressive, as in the gradual wasting

away of the consumptive, but quick and

violent. The victims even repelled

physicians hardened to scenes of death

and dying. To add to the psychological

pressures, nobody knew how cholera was

contracted or whether it could be

treated. Thus it is small wonder that

the epidemic of the 1830s was regarded

as a "Scourge of God." As

Charles Rosenberg points out in his scholarly

study of the New York epidemics,

"Asiatic cholera was a disease not only of

the sinner but of the poor."70

Americans viewed their own "poor" as a hardy,

pious, and industrious class of laborers

intent on rising in the world, while

recent European and Irish immigrants

seemed to personify the intemperate and

impious element of society.71 In

cities and towns the poor usually found

68. S. F. Forbes, Annual Report of

the Health Officer of the City of Toledo, for the Year 1866

(Toledo, 1867), 3,21.

69. George E. Waring, The Sanitary

Conditions of City and Country Dwelling Houses (New

York, 1877). (Note the bibliographic

entries under the heading "Architectural Mechanics.")

Rural Americans, and small farming

communities, did not feel the same pressures. Most rural

farmhouses are still supplied by a well

and human wastes are conveyed through a septic tank.

Ground water, contaminated from many

causes, is probably a greater problem today around

farming communities than it was in the

nineteenth century.

70. Charles E. Rosenberg, The Cholera

Years (Chicago and London, 1962), 55.

71. Samuel Williams was an Ohio pioneer

and lay preacher who had little tolerance for

Cholera Years in Ohio

191

themselves crowded into the worst houses

and tenements, in the worst loca-

tions, and they could not afford to

leave when an epidemic struck.

Statistically, cholera did claim more

"poor" victims.72 Blacks are often men-

tioned in contemporary literature as

being the victims of cholera because so

many lived in the so-called poor

districts or slums, but this writer found no

evidence of their being blamed for

carrying the disease.

Cholera was considered a contagious

disease during the first epidemic,

spread by personal contact or through

the air by "invisible animalcula";

Avoid the slums and their denizens,

avoid the cholera. This theory had to be

abandoned as the disease became

pandemic, attacking all society. Sanitation,

as a preventative measure for all

diseases, proved to be the most important

civic achievement of the forty years of

cholera epidemics. Xenia, with its

straightforward policy about cleanliness

for all residents, proved that cholera

could be prevented by simple means.

Mechanical techniques for sanitary sys-

tems had been available long before

cholera appeared in the United States, and

the disease provided the impetus to

install such facilities as piped water and

covered sewers. Cholera's most important

contribution, however, is evident

today in public health programs that

encompass all members of society.

people and events he did not understand.

The following excerpt from a letter by Williams

(Cincinnati, 8 June 1849) to his brother

combines his own intolerance with ethnicity, religion,

and temperance: "The present

aggravation of the epidemic arises mainly from the reckless

dissipation of the German population on

last Sabbath, at their 'Musical Jubilee' on 'Bald Hill,'

back of Columbia, where several

thousands of them spent the day in drunkenness, & eating

fruits & poisonous viands, pastries

&c.--These furnish most of the new cases." Samuel

Williams, "Autobiography,"

TMs. The Ohio Historical Society Library, Columbus, The origi-

nal manuscript is in the collections of

the Ross County Historical Society, Chillicothe.

72. Rosenberg, The Cholera Years, 57.

DONALD A. HUTSLAR

"God's Scourge": The Cholera

Years in Ohio

Introduction

Between 5 August and 23 September 1834,

fifty-six residents of the small

Ohio village of Zoar, Tuscarawas County,

died of cholera. Zoar was the

home of a communal society of about

three hundred German Separatists, per-

sons who had differed with the doctrine

of the Lutheran Church and migrated

to the United States. During the summer

of 1834 a boat on the Ohio Canal

stopped at Zoar with one sick passenger,

Mr. Allen Wallace; he was carried

into the canal tavern (which is still

standing) and nursed by the Zoarites until

he died. He was buried in the village

cemetery. A few days later a woman

claiming to be his wife arrived to

retrieve some money and papers Wallace

was carrying. Wallace was disinterred

and the items were recovered from his

clothing. That night cholera broke out

in the village.l

The cholera epidemics of the nineteenth

century reflected a basic change in

society: industrialization, worldwide

commerce, massive urban centers, social

unrest, a migratory population. The

disease followed the ever-quickening

transportation systems, first the

waterways, then the road networks inland,

and finally the quick railroad lines of

mid-century. The disease was deadly in

its homeland of India due to poor

sanitation and a dense population in the

cities; in western Europe and the United

States, these two factors characterized

the industrial cities with the added

complication of rapid transportation.

During the early 1830s western Europe

struggled with political unrest and

unstable economic conditions,2 causing

thousands of immigrants to cross the

Atlantic Ocean at about the time the

cholera arrived in Europe. The United

States and Canada were aware of the

danger; quarantine of the ports of entry

Donald A. Hutslar, long-time curator of

history at the Ohio Historical Society, is a Ph.D. stu-

dent in architectural history at The

Ohio State University. He would like to thank Professor

Joan Cashin of The Ohio State University

Department of History for her assistance with this

article.

1. Hilda D. Morhart, The Zoar Story (Dover,

Ohio, 1967), 75. The disease may have been

spread through the communal dairy rather

than Zoar's water supply, a highly efficient, en-

closed system supplied by a hillside

spring on the opposite side of the river from the tavern.

The Zoarites discovered that liquids

were an effective treatment for cholera.

2. R. E. McGrew, "The First Cholera

Epidemic and Social History," Bulletin of the History

of Medicine, XXXIV (1960), 66-67.

(614) 297-2300