Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

PATRICIA A. CARTER

Housing the Women Who Toiled: Planned

Residences for

Single Women, Cincinnati

1860-1960

The Lawrence [Home] stands as a barrier

to sickness and evil, she opens her doors

and invites the young, unprotected girl

to come in and make her home here-not

that she may be rescued as a brand from

the burning, but that she may not even get

near enough to the fire to be scorched.

She does not consider herself, nor is she

considered, a charity inmate. Her

independence and self-respect are guarded and

fostered by the management, although her

three and a-half dollars (sometimes the

larger part of her week's earning) does

not cover the expense of her maintenance.1

The above statement illustrates the

sentiments regarding many single,

women workers at the turn of the

century. Those separated from their fami-

lies and working long hours for low pay

were viewed as morally and physi-

cally vulnerable to the hazards of urban

life. By the early 1900s many cities

had established homes for unwed mothers

or reformatories for women who

"went bad." However,

residences for working women were seen, as the quote

suggests, as a preventive measures to

such deplorable outcomes. The move-

ment to provide safe and affordable housing

to single working women began

in England and moved to the U.S. in the

late nineteenth century. Throughout

the early twentieth century religious

groups and social service providers es-

tablished homes for the protection and

comfort of this new group of workers

in cities throughout the country.

Cincinnati was the third U.S. city to estab-

lish a home for women workers, when in

1858 the Sisters of Mercy founded

the House of Mercy. By 1930 at least

nineteen such institutions had opened

in the city. Though only one of the

homes still remains, this study finds

that the planned residences were

generally successful in providing their in-

tended services.

Previous research on the history of

housing for working women has tended

to focus primarily on an analysis of

specific homes and the degree to which

middle-class ideology dominated the

day-to-day interactions within them.2

Patricia Carter is on the Women's

Studies faculty at the University of Connecticut.

1. Annual Report of the Lawrence

Home, (n.p.: November 4th, 1908), 4-5.

2. M. Christine Anderson, in "Home

and Community for a Generation of Women: A Case

Study of the Cincinnati YWCA Residence,

1920-1940," Women in Cincinnati: Century of

Achievement, 1870-1970. (Cincinnati, 1987), 34-41; Lisa Fine, "Between Two

Worlds:

Business Women in a Chicago Boarding

House, 1900-1930," Journal of Social History, 19

Housing the Women Who Toiled 47

This essay provides another perspective

by taking an overview of planned

housing of this type in one city,

Cincinnati, over a period of one century.

This macro focus allows for a more

holistic review of the planning, devel-

opment, growth and decline of the

planned boarding units.

Several factors make a study of

Cincinnati's planned housing for working

women particularly interesting,

including: its early status as a major

Midwestern industrial city; the city's

centrality in the African-American

Diaspora; its large population of Reform

Jews; and its geographic location as

a basin city (bounded by the Ohio River

to the south and hillsides on the

other three). The importance of this

last factor is its influence in keeping

Cincinnati a walking city, meaning one

which could be traversed from one

side to the other without difficulty or

a lengthy amount of time. It therefore

remained a residential city for a longer

period than those not constrained by

similar geographical barriers.3 This

essay will show how the planned resi-

dences for women responded to shifts in

the city's population, deterioration

of the urban core, and general movement

to suburbanization.

Other evidence from this research

indicates that though homes for white,

middle-class women were better funded

and more prevalent, the needs of older,

working-class, Jewish and

African-American women were not completely ig-

nored. When viewing the history of these

latter homes one can see both the

rise of an era of interracial

cooperation on social service boards but also the

ease with which planners gave into

racism, ageism, and classism that created

the necessity for separate homes in the

first place.

Background on Homes for Single Women

The development of special housing for

single working women corre-

sponded to the increasing percentage of

young, white, native-born women in

the U.S. labor force in the latter part

of the nineteenth century. Higher educa-

tion, the women's movement, urbanization

of jobs, immigration, and migra-

tion patterns of southern

African-Americans contributed to the acceleration of

the female work force in Cincinnati and

the U.S. at-large. The image of this

group of neophyte laborers elicited the

sympathies of urban reformers and

drove them to develop an infrastructure

to secure the protection of the naive

farm girl in the big and friendless

city. Illustrative of this concern were the

(Spring, 1986), 511-19; Joanne

Meyerowitz, "Women Adrift": Wage-Earning Women Apart

from the Family in Chicago, 1880-1930 (Chicago, 1989); Lynn Weiner, "'Our Sister's

Keeper': The Minneapolis Woman's

Christian Association and Housing for Working Women,"

Minnesota History 64 (Spring, 1979),189-200.

3. For more information on the

relationship of Cincinnati's geography to its development see

Zane Miller, Boss Cox's Cincinnati:

Urban Politics in the Progressive Era (New York, 1968),

3-56; Glenn Miller, "Transportation

and Urban Growth in Cincinnati, Ohio and Vicinity: 1788-

1980" (Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Cincinnati, 1983).

48 OHIO

HISTORY

ads placed in small-town papers and in

train stations warning young women

not to move to urban areas without a

secure promise of employment or an

adequate means of support. Despite such

precautions, the allure of the city

prevailed, so reformers established

alliances with Traveler's Aid societies and

railroad workers who could direct new

arrivals to appropriate services or shel-

ters.4 The scarcity of jobs

and affordable housing was aggravated by the fact

that hoteliers and boarding housekeepers

often preferred male over female resi-

dents, believing that men were less

trouble.5 As a result women's wages,

only one-third to one-half their male

counterparts,' had to be stretched farther.

Comfortable housing in safe

neighborhoods came at a premium. Food was

more expensive for women who ate in the

better restaurants because the

cheaper ones were located in bars or in

bad neighborhoods. These difficulties

were further complicated by racism and

ethnocentrism, as well as the prevail-

ing middle-class values and expectations

of urban reformers and the piety of

the religious groups which sought to

rescue women from the streets.

The history of the women's housing

movement is inextricably tied to the

consumer reform movement which had its

origins within the women's suf-

frage movement. Margaret Gibbons Wilson

notes three types of early twen-

tieth century urban reformers: the civic

reformers who campaigned for a clean,

efficient government and an end to

"bossism"; the social reformers who

struggled to ameliorate the hardships of

urban life such as housing, disease,

and unsafe working conditions; and the

city planners who worked to rational-

ize and beautify the urban environment

in the hope of bettering the lives of

its inhabitants. It is safe to say that

all three movements played a part, often

simultaneously, in the development of

housing for working women.6

Aside from family homes, women workers

lived in a variety of structures:

lodging houses, apartments, boarding

houses, and employer-owned or subsi-

dized facilities. Lodging houses offered

sleeping quarters but not eating ac-

commodations. Boarding houses provided

renters with both an individual

sleeping room and a common dining room.

Apartment and tenement houses

were generally family units, in which

rooms were rented to boarders and food

4. Evidence of this can be seen in:

"A Philadelphia Warning to Girls," Religion and Social

Service, 46 (February 1, 1913), 234, which stated that the

Commission on Social Service of the

Philadelphia Interchurch Federation had

published warnings in the newspapers to "girls

throughout the country not to be led

into going to big cities unless they have been assured of

honest employment at more than $8 a

week"; or in Mrs. Newell Dwight Hillis, "The Home

Life of Working-Girls," The

Outlook, 98 (May 14, 1911), 72-75, which discussed the rising

number of young, inexperienced women

workers falling into "white slavery." See also

Florence Kelly, "Why Working Girls

Fall into Temptation," Ladies Home Journal, 26

(November, 1909),15-16; Harriet

Brankenhurst, "The Business Girl and the Confidential

Man," Ladies Home Journal, 28

(March 15, 1911), 26.

5. Lynn Weiner, From Working Girl to

Working Mother: The Female Labor Force in the

United States, 1820-1980 (Chapel Hill, 1985), 53.

6. Margaret Gibbons Wilson, The

American Woman in Transition: The Urban Influence,

1870-1920 (Westport, 1979), 93.

Housing the Women Who Toiled 49

preparation facilities were at times

included.7 Employer-owned housing was

designed similarly to the boarding house

but offered, at least, partially subsi-

dized rents. Finally, domestic workers

sometimes boarded with their employ-

ers, usually in small sleeping quarters

above the main house.

Mainstream housing theory of the period

generally ignored the housing

needs of single, working women. Housing

developments in England and the

U.S. focused almost exclusively on the

needs of working-class families.

Morris Knowles' Industrial Housing, considered

a critical work of its time,

clarified the general sentiment of

planners when he stated that: "Special build-

ings for housing women will, in

developments, be found unnecessary."8 The

response to working women's housing

needs came first from religious soci-

eties. Protection of the virtue of

working women from the moral depravity

of urban life provided a key explanation

for the intervention of these groups.

The roots of their interest began with

housing "fallen women," unwed moth-

ers or former prostitutes, who turned to

such organizations in contrition or as

their only means of getting off the

streets.

The transition into housing for young

working women came as reformers

began to recognize the dilemma faced by

naive young rural women when they

arrived in the big city seeking

employment.9 The origin of the homes for

Cincinnati working women is so closely related

to that of institutions for

"errant women" that it is

often difficult to discern between the two when

looking through primary documents.

During the first decades of their devel-

opment such residences were listed in

social service directories along with

those for such special populations,

cited as "incurables, invalids, elderly, in-

sane, and fallen women."10 The

Convent of the Good Shepherd opened four

homes in the Cincinnati area with a

two-fold purpose: "Bring back to the

pathways of virtue the unfortunate young

women who have strayed," and to

"shelter from peril young girls,

both white and colored, as yet innocent of

sin, but sorely exposed to untoward

social environments." 11 It could not be

determined what percentage of each group

constituted the Good Shepherd

homes or whether the two groups were

kept separated.

7. Albert Benedict Wolfe, The Lodging

Problem in Boston (Boston, 1906), 5.

8. Morris Knowles, Industrial Housing

(New York, 1920), 340-41.

9. See for instance "Her Sister in

the Country Who Wants to Come to the City to Make Her

Way," Ladies Home Journal, 28

(Spring, 1911), 16; Alice N. Lincoln, "Some Ways of

Benefiting a City: Working Girls

Homes," The American Monthly Review of Reviews, 18

(November, 1898), 604.

10. See for example Bureau of Census

Benevolent Institutions 1910 (Washington, D.C.,

1913) which lists homes for working

women with those for the aged, infirm, destitute, incur-

able, epileptics and convalescents; and

the 1900 Williams Cincinnati Directory (Cincinnati,

1900), 291-92.

11. Charles Frederic Goss, Cincinnati:

The Queen City, 1788-1912 (Cincinnati, 1912), 282.

|

50 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Two 1898 publications established early twentieth century standards for working women's housing. In the first, Mary S. Ferguson of the U.S. Department of Labor described the ideal boarding place as one in which "working girls and young women of good moral character can live at prices within their reach, in which they can find . . . the conveniences, social plea- sures, and good influences of a real home, and ... many comforts and wide opportunities for pleasure and culture."12 Concerned about homes "with the odor of charity," the author cautioned her readers "to distinguish between phi- lanthropic effort and charity."13 Ferguson also objected to unnecessary rules and suggested that administrators offer advice instead of interference. Future buildings, she insisted, should afford workers greater privacy in the form of individual sleeping rooms and rates which accommodated factory workers. The second publication, "Girls' Cooperative Boarding House," described the "women's hotel of the future." Author Robert Stein presented his vision of a "gigantic but elegant building" which featured a public dining room on the

12. Mary S. Ferguson, "Boarding Homes and Clubs for Working Women" Bulletin of the Department of Labor, 15 (March, 1898), 141. 13. Ibid., 142. |

Housing the Women Who Toiled 51

ground floor opened to both women and

men.14 The restaurant would subsi-

dize the hotel as well as employ some

residents as waitresses and cooks. The

training they received in these

positions would allow them eventually to

move to better paying positions outside

the hotel. Courses in dressmaking,

millinery, stenography, typing,

bookkeeping, photography, and typesetting

would be offered to residents as well as

free and regular lessons in "language,

elocution, dancing and physical

culture." Stein imagined that the hotel would

function as a place where society ladies

and girls of humble origins could mix

freely and engage in uplifting

activities such as literary and scientific clubs,

and dramatics and musical exercises. A

membership committee would screen

men invited to coed activities to ensure

that only "gentlemen" were admitted.

The hotel would also operate a farm on a

body of water about ten miles from

the city. There a spacious villa,

playgrounds, fields, orchards, boats, and

sandy beaches would provide a vacation

resort where tired the city dwellers

could recuperate in play and pleasant

work. An open invitation would be is-

sued to young rural women and men to

come and socialize with the city

women and participate in the educational

and evening offerings at the resort.15

Both of these early publications

exorcised the notion of charity as a primary

force in the establishment of homes for

working women, preferring instead to

consider the homes "endowed"

in the manner of other community services

such as libraries, schools, museums, and

hospitals.

Working Women in Cincinnati

The employment patterns of Cincinnati

women were fairly consistent with

those of the female U.S. labor force

at-large. The average single, white fe-

male worker in 1888 was just over 22

years old. She began work at age 15

and had been employed in her present

occupation for five years. She was

likely to have been born in the U.S. (81

percent) but of foreign-born parents

(74 percent fathers, 71 percent

mothers), most notably either Ireland or

Germany.16 Since men and

women participated about equally in the 1890-

1910 migration from the southern U.S.,

African-American women entered the

Cincinnati labor force in large numbers.

During this period the total number

of African-American women increased by

57 percent and single women by 63

percent. Of the single women 61 percent

were between the ages of 15 and 24

and 32 percent between 15 to 19 years

old.17 By 1910, 49 percent of all

14. Robert Stein, "Girls'

Cooperative Boarding Clubs," Arena, 19 (March, 1898), 397-417.

15. Ibid.

16. Working Women in Large Cities:

Fourth Annual Report of the Commissioner of Labor

(Washington D.C., 1889), 268-69.

17. William Loren Katz, ed., Negro

Population in the United States, 1790-1915, William

Loren Katz, editor, (New York, 1968),

273-76.

52 OHIO

HISTORY

Cincinnati African-American women over

the age of 16 worked outside the

home.18 In Ohio the largest

percentage of African-American workers engaged

in laundry (32 percent) and tobacco

factory (43 percent) labor.19

Women's employment was generally

characterized by low pay, long hours,

and unhealthy conditions. Wages in 1900

averaged $4.60 for a 58 hour

week.20 Employers' assertions

that women worked only to buy luxuries

were disputed by surveys such as those

done by the Ohio Bureau of Labor,

which clearly indicated that female

employees had difficulties in meeting ba-

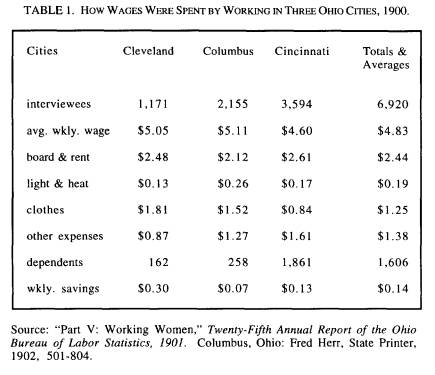

sic survival needs. 21 Table 1

illustrates the amounts spent by the average

Ohio female wage earner for basic needs

in 1900. Board, rent, light and heat

consumed over one-half of the average

worker's wage, leaving transportation,

health care, entertainment, and laundry

to be bought with a mere $1.38. A

more descriptive picture of the living

conditions afforded by the wages allot-

ted Cincinnati women was provided by

another survey which offered individ-

ual portraits of workers contained in

the aggregate statistics.22

Number 23

Packer in a cracker factory. Is probably

over 30 years of age, altho [sic] exact age

was not reported. Has had nearly 15

years experience in factory work. Began as a

minor, in a paper box factory, working

as a turner and a stitcher and finally ad-

vancing to assistant forelady. Due to a

seemingly justifiable cause, she left and

began work for a far lower wage. Does

her own sewing and sewing for a relative,

in return for which relative does her

laundry for less than market rate. Goes to

night school (free) and her desire for

improvement is evidenced by her entries for

lessons in dressmaking. Lives in 1 room

where she does light housekeeping.

Keeps her room neat and clean. Gets only

one real meal a day. Goes irregularly to

relatives in better circumstances for a

considerable number of meals. She has a

passion for flowers, but indulged

herself only to the extent of $0.50 worth during

the year. Rather more resigned than

cheerful. Factory conditions where she

works, according to her statement, are

without a menace to health. 23

Number 31

She is a bindery employee. Wages $7.00

per week, thirty-three years of age and

had five years and nine months

experience at bindery work, besides two years at

labeling. Her work was irregular on

account of her mother's poor health. If this

worker was not living in a boarding home

for working girls her condition would

be very serious, as she has been out of

work for fifteen weeks during the past year.

She has had to neglect some dental work

that she really should have had done, as

18. David A. Gerber, Black Ohio and

the Color Line, 1860-1915 (Urbana, 1968), 278-79.

19. Negro Population, 522.

20. Working Women in Large Cities, p.

17; Work and Wages of Men, Women and Children:

Eleventh Annual Report of the

Commissioner of Labor, 1895-96 (Washington

D.C., 1897), 30-

31.

21. "Part V: Working Women," Twenty-Fifth

Annual Report of the Ohio Bureau of Labor

Statistics (Columbus, 1902), 802-03.

22. Dept. of Investigation and

Statistics, Cost of Living of Working Women in Ohio

(Columbus, 1915).

23. Ibid., 175-76.

Housing the Women Who Toiled 53

she had no money to pay for it. She has

been in the habit of keeping an account

of her income, but her expenditures are

so nearly confined to absolute necessities

that she had not previously kept account

of them . . . her most unusual expenditure

is for a newspaper in order to look in

the want columns for work.24

Each of these portraits demonstrated the

frugality required of female workers.

Though in their thirties, both continued

to live hand-to-mouth existences,

sacrificing nutritional and physical

needs because of poor wages. In the case

of Number 31, one wonders whether the

boarding home for working girls was

able to provide the same type of support

structure provided Number 23 by her

relatives with whom she shared meals and

traded sewing for laundry duties.

The Origins of Housing for Cincinnati

Working Women

An 1888 U.S. Commission of Labor survey

of women who worked in

large cities found that the percentage

of working women living at home was

higher in Cincinnati than any of the

other twenty-one studied. Though this

was generally thought to indicate good

housing conditions, the survey author

noted otherwise, declaring that the

homes of Cincinnati working women were

"unusually uninviting."

The streets are dirty and closely built

up with ill-constructed houses, holding from

two to six families. Many of the poorer

parts of Cincinnati are as wretched as the

worst European cities, and the

population looks as degraded. Rents are dispropor-

tionately high and commodities dear. 25

Cincinnati compared poorly with other

midwestern cities such as Cleveland

where "separate houses, good

sanitation, comfortable surroundings, and a

general respectability are the rule

rather than the exception, and extreme

poverty is rarely witnessed." The

survey also noted that working women in

Indianapolis lived in

"cottages" which as a rule were neat and comfortable

with moderate rents. 26

Only one Cincinnati residence, the

Sacred Heart, founded in 1882, was in-

cluded in the survey. The home, managed

by a Miss McCabe, charged rents

which ranged from $1.00 to $3.00 a week.

Despite the rather high rates, the

survey noted it was crowded with four to

seven women sharing each tiny

sleeping room. Compared to the

"airy cottages" of Indianapolis, the Sacred

Heart seemed squalid and illustrated a

critical need for additional housing for

Cincinnati working women.

24. Ibid., 197-98.

25. Working Women in Large Cities, 17.

26. Ibid., 18.

Housing the Women Who Toiled 55

The report failed to mention the

existence of two similar homes: the House

of Mercy founded in 1858, and the YWCA

residence opened in 1868. Several

other units opened in the following

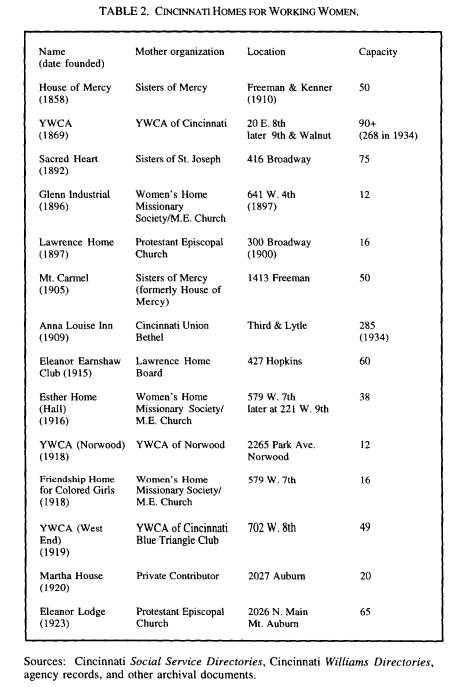

decades. Between 1858 and 1930 nine-

teen planned residences for single women

were developed in Cincinnati.

Some were short-lived, others merged,

and only one, the Anna Louise Inn,

remains in existence today. There is scant

information on several of the in-

stitutions, as many of the original

records have either been destroyed or are

privately held. But available

information suggests that particular ethnic, reli-

gious, and racial groups set up their

own homes, often with financial assis-

tance from white philanthropists. For

instance, by 1924, four homes had

been established for African-American

women: the Home for Colored Girls,

Colored Catholic Girls Home, the

Evangeline Booth Home for Colored Girls

(for unwed mothers), and the Cincinnati

Friendship Home. The first, the

Home for Colored Girls (HCG), was

founded in 1911 by the Cincinnati

Protective and Industrial Association

for Colored Women and Girls, a group

composed of local philanthropists and

reformers, both African-American and

white.27 The absence of

hotels and boarding houses open to African-

Americans in the city indicated a

critical need for the facility. The founders

intended the HCG to serve women, ages 14

to 35, seeking employment in

the city. Train depot employees and

volunteers greeted visitors with informa-

tion about the facility on their

arrival.28 Despite its initial success, after less

than a year the organizers abruptly

changed its mission to a home for younger

girls from "broken and troubled

homes."29

The Friendship Home, which opened in

1918, became the first permanent

planned residence for African-American

working women in Cincinnati.30

Though many of its residents came to the

city hoping to find industrial labor

connected to the war effort, few found

anything except domestic service, until

the mid-1920s when white-collar

opportunities such as teacher, social worker,

nurse, and librarian began to open to

African-American women.31 The Home

required each boarder to attend church

services. Piano and voice lessons were

offered regularly, and some residents

participated in the Friendship Home

Choir which performed at events

throughout the city to raise funds for the fa-

cility.32

The Blue Triangle Club, the West End

Branch of the Cincinnati YWCA,

27. Williams Directory of Cincinnati (Cincinnati,

1969), 326; Goss, Cincinnati: The Queen

City, 324.

28. Gerber, Black Ohio, 449-50;

Frances Kellor "Assisted Emigration from the South-the

Women," Charities, 17

(October 7, 1905), 12.

29. Home for Colored Girls (n.p.:

n.d.). Pamphlet located at the Cincinnati Historical Society.

30. Goss, Cincinnati: The Queen City,

324.

31. Ruth Esther Meeker, Six Decades

of Services, 1880-1940: A History of Woman's Home

Missionary Society of the Methodist

Church (n.p., Methodist Episcopal

Church, 1969).

32. Ibid.

56 OHIO

HISTORY

opened in 1919, accepting women ages

from 14 to 35.33 Both transients and

permanent members were welcome and fees

were based on ability to pay.

The three-story, twelve-room building

was largely supported by contributions

from local churches and lodges. The

first and second floors of the building

were used for club and recreational

purposes, and the third story was a dormi-

tory. 34 The name "the Blue

Triangle Club" was given to African-American

branches of the YWCA throughout the

country.35 The home ran a laundry,

the proceeds from which helped to

support the facility. Women who could

not find employment worked in the

laundry in exchange for their room and

board.36 A day nursery, also

housed in the facility, provided another em-

ployment opportunity for residents.

Working mothers could leave their chil-

dren at the center for five cents a day.37

A tea room served as a meeting place

for residents and nonresidents at an

affordable price. Recreational facilities in-

cluded a gymnasium, swimming pool, and

basketball and tennis courts which

were available to nonresidents as well.38

David Gerber contends that

African-American women's clubs of this period

tended to neglect the real needs of the

migrant poor. Unable to understand the

struggles of the too distant

lower-class, African-American clubwomen offered

them little more than platitudes.39

Gerda Lerner, however, suggests that

African-American women were deeply

involved in social work.40 In

Cincinnati it would appear that both

views had merit. African-American

women certainly were present on the

interracial boards which helped to de-

velop the planned residences for this

group of working women. However,

records do not explain to what extent

they were also key actors in the concep-

tualization and maintenance of these

projects.41 The Martha House, operated

by the Jewish Social Services and funded

primarily through the contributions

of one anonymous donor,42 appeared

to fill a specific need. When it opened

in 1920 the few Jewish women residing at

the YWCA left for the Martha

House, perhaps indicating that the 'Y'

had offered a less than hospitable

33. Wendall P. Dabney, Cincinnati's

Colored Citizens: Historical, Sociological, and

Biographical (New York, 1922), 216-18.

34. Ibid., 210.

35. Jane Olcott, The Work of Colored

Women (New York, 1919), 106-07.

36. Dabney, Cincinnati's Colored

Citizens, 210.

37. "Friendship Home Statement to

the Public," The Union, 14 (January 18 1920), 1.

38. Ibid.

39. Gerber, Black Ohio, 113.

40. Gerda Lerner, Black Women in

White America: A Documentary History (New York,

1972), 435-58.

41. Jane Edna Hunter's A Nickel and a

Prayer (Nashville, 1940) provides an interesting de-

scription of her struggle to gain

interracial cooperation in establishing a home for African-

American single working women in

Cleveland.

42. Frances Ivins Rich, Wage-Earning

Girls in Cincinnati: The Wages, Employment,

Housing, Food, Recreation, and

Education of a Sample Group (Cincinnati,

1927), 30.

|

Housing the Women Who Toiled 57 |

|

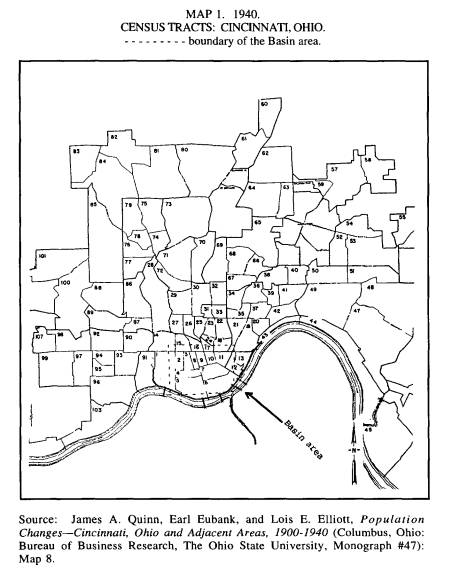

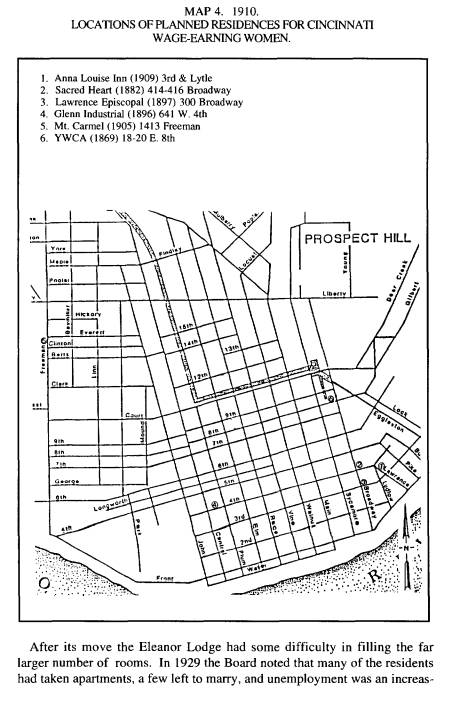

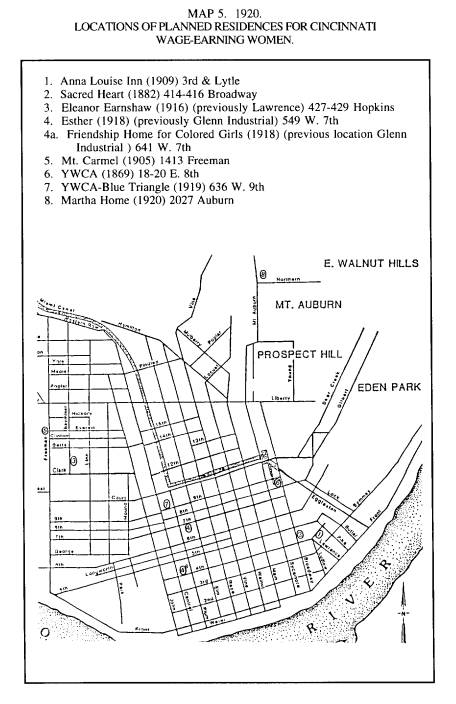

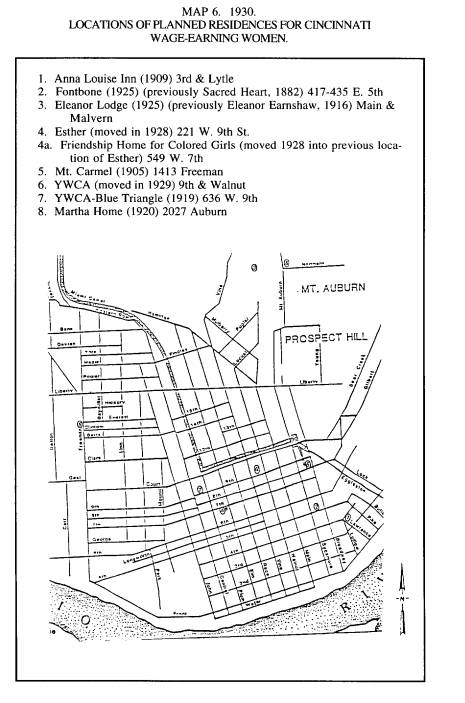

environment to its Jewish residents.43 Located on Auburn Avenue in Mt. Auburn in a section of Jewish homes (Map 1), this residence was the first to situate itself outside the walking city, forcing the residents to use public transportation to jobs downtown.

43. Anderson, "Home and Community," 36. |

58 OHIO HISTORY

Providing housing to women employed in

industrial occupations was an

initial goal of most of the planned

residences. Yet the evidence suggests that

this represented the planners' greatest

failure as facility after facility admitted

increasing numbers of white-collar

workers. This seems to have been related

to the fact that industrial workers,

with little formal schooling, earned less,

worked longer, and were older than their

white-collar counterparts. As a re-

sult they had less money to spend on

room and board. An example of this

dilemma can be seen in the Anna Louise

Inn, founded in 1909. The Union

Bethel, Cincinnati's oldest social

service institution, began its activities in

1830 with the goal of providing decent

living quarters and religious services

to riverboat workers along the

Cincinnati wharf area.44 In the style of the

Hull House in Chicago and Toynbee Hall

in London, the Union Bethel set

up, in 1900, a settlement house serving

19 blocks of Cincinnati's most im-

poverished population. Boys' and girls'

clubs were formed, a gymnasium and

library organized, public baths

installed, and Cincinnati's first kindergarten

established in the settlement. In 1906,

the Union Bethel opened a lunchroom

for women working in nearby factories.

It was through this effort that the

trustees learned of the need for better

housing for women workers and resulted

in the building, in 1909, of the Anna

Louise Inn for Working Women.45

The Inn, named after the daughter of

Charles P. and Anna Sinton Taft, ma-

jor donors in the construction of the

facility,46 became the largest home for

working women within Cincinnati. The

five-story brick and terra-cotta build-

ing had the latest amenities, including

steam heating and gas lighting.47

The home had 120 single sleeping rooms,

several parlors for entertaining

guests, a dining room, and offered

social, religious and educational activities.

Richly furnished with oriental carpets,

oil paintings, giant gilded mirrors, and

carved furniture, the facility must have

astounded its residents.48 The weekly

rent, based on a sliding scale,

averaged, in 1900, between $2.75 to $4.75 a

week for a room and 21 meals. To qualify

for residence workers had to earn

less than $10 a week.49 The

home met with immediate success and a long

waiting list resulted. In 1915, the

Tafts again responded to the need for addi-

tional rooms and made a gift of the

property adjoining the Inn so that a wing

could be built.50 Though the

bylaws stated that the Inn had no restrictions as

to race or religion of residents, there

were no African-American boarders until

44. Howard C. McClary, 150 Years of

Community Service: The Story of the Cincinnati Union

Bethel, 1830-1980 (Cincinnati, 1981), 1.

45. Ibid., 22.

46. Ibid., 32.

47. Sanborn Insurance Maps, located at

the Cincinnati Historical Society.

48. Goss, Cincinnati: The Queen City,

299.

49. Ibid.

50. McClary, 150 Years of Community

Service, 40.

Housing the Women Who Toiled 59

the 1960s.51 References were

required and, despite Bethel Union's original

intention of providing housing for

nearby factory workers, the majority of

residents held white-collar jobs such as

stenography, bookkeeping, office

clerk, telephone operator and sales.52

Although it is unclear as to why this

occurred, factory workers might have

been intimidated by the opulence, or

might not have known how to apply for

admission. Perhaps home managers

favored white-collar women, or the

trustees found it financially advantageous

to admit those capable of paying the fee

at the top of the sliding scale. That

this situation occurred more often at

the more grandly designed structures

suggests the latter explanation.

The homes which most successfully met

the needs of industrial workers

were those in which the residents were

older, such as the Sacred Heart Home

for Working Girls. Those employed as

white collar workers in clerical and

sales positions were generally younger

than those in industrial work. For ex-

ample, in 1900 two-thirds of the home's

73 residents were age 30 or older and

66 percent held either industrial or

domestic labor occupations. In 1910, 58

percent were age 30 or older with an

average resident age of 35. The

youngest boarder was 18 and the oldest

65. Sixty-three of the 80 residents

(79 percent) held occupations which

could be identified as industrial or domes-

tic labor. Thirteen of the residents had

been unemployed between one and 40

weeks in 1909. Comparatively lower

percentages of residents held indus-

trial or domestic labor jobs at the

Lawrence (42 percent), Anna Louise Inn

(29 percent), Glenn Industrial (24

percent) and the YWCA (22 percent). Ages

also ranged lower; 58 percent of

residents at the Sacred Heart were under the

age, compared to the Lawrence (29

percent), Anna Louise Inn (26 percent),

Glenn Industrial (24 percent), and the

YWCA (32 percent).53

The Decline of Housing for Cincinnati

Working Women

There are several reasons for the

general decline of planned housing for

women. At the top of these are the

influences of the changing city and the

societal conceptualization about women

and work. The rise of public and

private transportation facilitated the

suburbanization of Cincinnati. As

smaller neighborhoods sprang up around

Cincinnati they created their own

business districts where women could

also find employment, thus increasing

the availability of jobs closer to some

women's family homes. The electric

streetcar increased accessibility to

Cincinnati's outlying areas, such that for

the first time blue-collar workers could

afford to live beyond the city limits

51. Ibid., 65.

52. Information compiled by the author from:

U.S. Bureau, Thirteenth Census of the United

States (Washington, D.C., 1910), Sheet 8A.

53. Ibid.; and from U.S. Bureau, Twelfth

Census of United States (Washington D.C., 1910).

Housing the Women Who Toiled 61

and commute to work. As a result, it was

possible for young women to live

at home and travel progressively longer

distances to work. In addition, the

locus of female employment shifted as

businesses moved to the hilltops sur-

rounding the city, then to outer rings

in the concentric business zones which

emanated from the downtown river basin.54

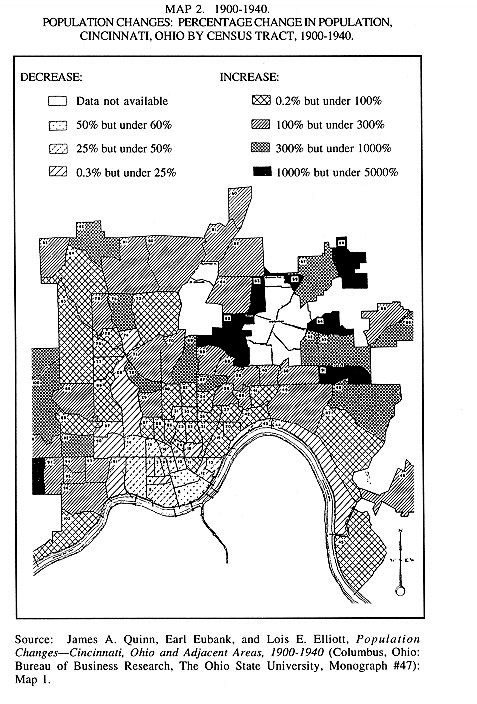

Between 1910 and 1920 the residential

population within the basin slowed

as a result of a number of factors,

including war casualties, a severe influenza

epidemic, and the temporary absence of

soldiers from their homes. By 1920,

the residential population decline began

to affect adversely the occupancy rates

of the planned units. A further decline

in the basin population between 1920

and 1930 occurred as heavy industry grew

in the area and the more prosperous

residents fled the deteriorating areas

of the city. Railroads, warehouses and

factories expanded and intruded upon the

basin's residential districts in the

west end of the city, pushing the now

mostly African-American population

of the West End farther north and east

into the city. Density increased as

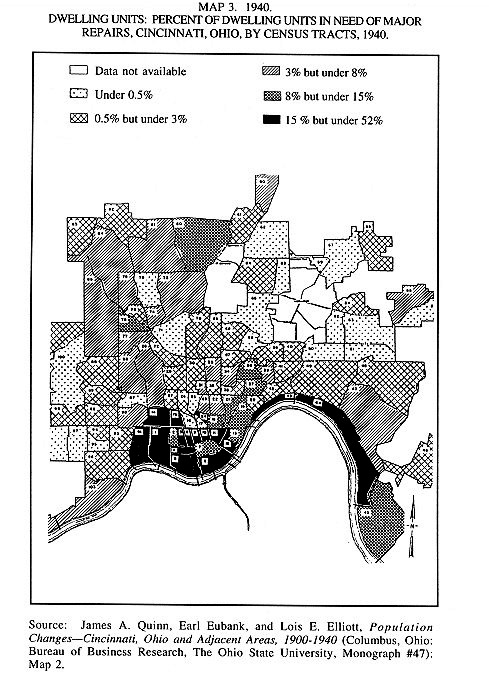

those too poor to leave crowded into the

ever-diminishing housing stock.

The Depression of the 1930s spurred a

wave of outward migration from urban

to suburban and rural areas in Hamilton

County, Ohio, and Campbell and

Kenton counties in Kentucky.55

The changing patterns in the city's

residential districts resulted in the ex-

tensive relocation of women's homes

throughout the period between 1910

and 1930. The planned units generally

moved north, following the trend to

suburbanization. In 1916 the Lawrence opened

a second home, the Eleanor

Earnshaw, in the northwest section of

the city (Map 2).56 Yet only seven

years later the home's trustees

complained that the neighborhood had grown

"rough and undesirable" and

worried that the "usefulness of the House is al-

most over."57 On the

other hand, the property around the Lawrence increased

in value, essentially as the result of

the demand for business office space in

the former residential area. With the

profit from the sale of the Lawrence and

a loan from the Procter family, the

trustees purchased the former Auburn

Hotel in Mt. Auburn, and both homes, the

Lawrence and the Eleanor

Earnshaw, combined into one facility,

called the Eleanor Lodge (Map 3).

This placed the home out of the basin,

and required some residents to use the

nearby streetcar for their daily commute

to work.58

54. Miller, Boss Cox's Cincinnati, 3-56.

55. James A. Quinn, Earle Eubank and

Lois E. Elliott, Population Changes-Cincinnati,

Ohio and Adjacent Areas 1900-1940 (Columbus, 1947), 7.

56. Cincinnati Enquirer, June 10,

November 4, 1916.

57. Twenty-Sixth Annual Report of the

Board of Managers of the Lawrence Home (n.p.,

1923), 11.

58. Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of

the Board of Managers of the Lawrence Home (n.p.,

1924), 7-8.

64 OHIO HISTORY

ingly serious problem especially

affecting older boarders.59 In 1930 the

Board began to discuss moving again to a

"more modern building in a more

convenient neighborhood"; however,

the Lodge struggled on in this same lo-

cation until it closed in 1948.60

The Glenn Industrial Home relocated in

1916, primarily due to a change in

the racial makeup of the neighborhood,

as the migration of southern African-

Americans expanded the boundaries of

their neighborhoods in this period

(Map 2).61 In 1928 the Glenn (now called

the Esther) moved still further

north.62 Though the primary

reasons for the relocations are attributable to

"white flight,"

African-American workers benefited indirectly as the

Friendship Home for Girls took over each

Glenn facility as it was abandoned

by whites (Map 3).63 Esther Hall

remained at its Ninth Street address until

1967 when it moved into suburban Walnut

Hills where it closed two years

later.64

The Sacred Heart changed both its

location and its name, becoming the

Fontbonne in 1925 (Map 3). Only the

Fontbonne, along with the Central

YWCA and the Anna Louise Inn, remained

in the basin area until the 1970s.

These three homes were rather large

institutions and heavily subsidized by

benefactors through financially

difficult periods, perhaps key factors in their

longevity.

It would appear that once the homes

moved out of walking distance from

the residents' place of employment, a

major part of the attraction for these

homes was lost. If women were going to

commute they could do so just as

well from their parents' homes. The

Depression of the 1930s pushed many

women out of the work force and the

planned homes suffered from a lack of

boarders throughout this period. Some

facilities never recovered from its fi-

nancial impact. Additionally, by the

1930s women were no longer considered

"adrift" when they left home

to engage in work. Young women had joined

the labor force in significant numbers

over a long enough time that the con-

troversy about them had all but faded.

The single wage-earner's presence in

the city was considered as normal as her

presence in the labor force.

Gradually, prohibitions against single

women living independently in their

own apartments were lifted and young

women began to reject the restrictive

59. The Thirty-Second Annual Report

of the Board of Managers of the Lawrence Home

Association (n.p., 1929), 6.

60. The Thirty-Third Annual Report of

the Board of Managers of the Lawrence Home

Association (n.p., 1930), 7-8.

61. Cincinnati Enquirer, October

5, 1916.

62. Meeker, Six Decades, 221.

63. Social Service Directory of

Cincinnati and Hamilton County (Cincinnati, 1934), 135.

64. Williams Directory of Cincinnati,

(Cincinnati, 1967), 337; Williams Directory of

Cincinnati (1969), 326.

Housing the Women Who Toiled 65

expectations of the planned home.

Cooperative apartments in which two or

more women shared the cost of rent

became more popular.

Analysis of the Homes

Despite the difficulty in obtaining

detailed information about them, it

would appear that Cincinnati homes for

working women met or exceeded

their original goal of providing a safe,

convenient, and financially accessible

shelter for single working women. In

fact, one might argue that the planned

housing offered better conditions than

those found in the average Cincinnati

home. In 1917 roughly one-third of all

U.S. citizens were judged to be living

in homes that were "bad by any

standard," and at least one-tenth of all

dwellings "constituted an acute

menace to health, moral, and family life."65

Similarly, a 1916 Cincinnati Consumer

League study found that, of 290

homes visited in the rooming house

district, only 60 met the requirements set

by the League's Room Registry Bureau. Of

the 60, 47 had rates in excess of

the average rents paid by working women.66

This condition did not improve

in the next decade as a 1927 survey,

comparing Cincinnati women living in

planned homes to those in regular

boarding houses or apartments, found that

the planned unit residents paid far less

rent: a weekly average of $2.75 com-

pared to $5.75.67 The survey concluded

that the few good rooms (outside the

planned units) available in the city

were priced so high that the average work-

ing woman could not afford them without

seriously impairing her resources

for food, clothing, health care, car

fare, recreation and other necessities.68

Rates in the planned shelters varied and

generally provided a better buy

than the alternatives. In 1927 weekly

rates could be found from $1.50 for

bed at the Friendship Home for Colored

Girls to $9.00 for a room and board

at the Eleanor Lodge. The average wage

of planned shelter residents was

$17.79 a week while those who boarded

in the rooming house district earned

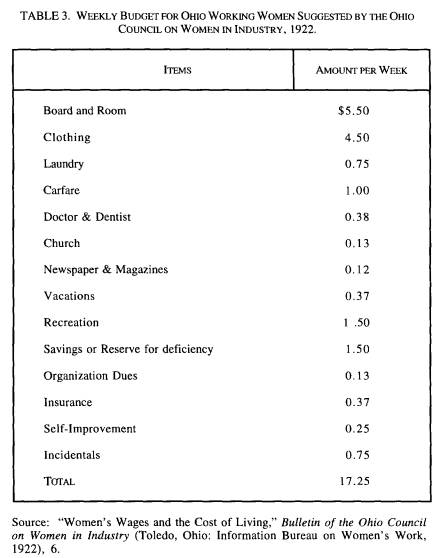

$18.36 a week. The Ohio Council of Women

in Industry designed a budget

to accommodate the average working

woman's salary (Table 3).

The suggested expenditure of $5.50 a

week for room and board illustrates

the economic difficulties faced by

working women of the era. Though

planned shelters required far less in

rent than traditional facilities, most of the

homes charged more than $5.50 a week. In

1926, only three of the eight fa-

65. Robert H. Bremner, From the

Depths: The Discovery of Poverty in the United States

(New York, 1956), 205.

66. The Consumer's League of Cincinnati,

A Study of Living Conditions in Rooming Houses,

Bulletin 20 (June, 1916), 2.

67. Rich, Wage-Earning Girls in

Cincinnati, 31-3la.

68. Ibid., 42-43.

|

66 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

cilities open to white women-the Esther Home for Girls, The Fontbonne, and the YWCA-charged $5.50 or less a week for room and board.69 The sliding scale for the Anna Louise Inn was set at $6 to $8 a week; Eleanor Lodge at $6 to $9; Emanuel $3.50 to $6 for rent and an additional $4.20 for board; the Mt. Carmel $6.25; and the Martha $6 to $7.50.

69. Social Service Directory of Cincinnati, 1926 |

Housing the Women Who Toiled 67

Unfortunately those earning below the

average wage or who had higher

than usual expenditures could not afford

to live in the planned homes. The

fees charged at the homes for

African-American women were substantially

less than those for white women. In

1929, the average African-American res-

ident's wage was $15 a week. The

Friendship Home still charged only $1.50

per bed for dormitory-style living

arrangements, and the Blue Triangle Club

charged $2 to $5 a week for rent.

However, the additional cost of a weekly

meal ticket at $2.50 pushed room and

board to $4.50 to $7.00, more than

many women's ability to pay.70

Night classes and planned units proved

another factor in attracting residents

to planned facilities. Twenty-one

percent of those living in planned housing

in 1927 possessed only an 8th grade

education (or less), 46 percent had com-

pleted high school, 15 percent had some

college, and 2 percent had four years

of college. A greater percentage of

those living in the planned units attended

night classes than those living in

private or boarding houses. Thirty-three

percent of office workers attended

evening classes, as did 8 percent of store

clerks, but less than 1 percent of

factory workers. 71 Though the most popu-

lar requests for classes included

psychology, music and art, facilities such as

the YWCA continued to offer only old

standards such as etiquette, dressmak-

ing, English, the life of Christ, and

Christmas crafts.72

At least 53 percent of the residents

returned to their parent's homes only

once a month or less. 73 Thus,

wage-earning women looked to the city to

provide amusements for their leisure

time. To that end the planned homes of-

fered libraries, classes, outings, and

other wholesome events to attract resi-

dents away from the more questionable

entertainments provided in the city.

In evaluating the social life at the

Cincinnati YWCA in the 1920s and 1930s

Anderson illustrates this by noting that

the residents "created an informal,

woman-centered community that reflected

both their shared consciousness as

paid workers and their anticipation of

future marriage" in such activities as

engagement parties, taffy pulls, and

mock weddings.74

Several of the planned residences owned

or had access to summer resorts

where residents could find relief from

the dirty and sweltering city. The Anna

Louise Inn had the Glen Vere, a camp

located about 15 miles northeast of the

city. The YWCA's summer cottage was in

Loveland, a rural community 25

miles from the city, and the Lawrence

and the Eleanor Earnshaw homes used

the Girls' Friendly Society summer

resort in Clermontville, located near the

70. Social Service Directory of

Cincinnati, 1929

71. Rich, Wage-Earning Girls, 55-57.

72. Ibid.

73. Ibid.

74. Anderson, "Home and

Community," 38.

|

68 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

70 OHIO HISTORY

Ohio River, twenty-five miles east of

the city on eight acres of land donated

by local philanthropist Thomas J. Emery

in 1903. At Clermontville the res-

idents usually stayed for two weeks

during the summer for which they paid

$2.50 a week. A vegetable garden

supplied a good portion of the meals, and

the surplus was sold to help support the

residence. Over three hundred

women each summer enjoyed the pleasures

of boating and swimming in the

river, hay rides, picnics, tennis, and

croquet, dancing, indoor games, and li-

braries, as well as orchards and

gardens.75 For many city-born women the re-

sorts became their first opportunity to

spend time in a rural environment.

Though few homes specified religious,

racial or class preferences, appar-

ently limitations regarding these

factors existed. The screening process pro-

vided the opportunity for eliminating

those with an "inappropriate" religion,

race or class background. Since none of

the homes, except those specifically

designed for them, had any

African-American boarders between 1890 and

1930, a bias seems evident; resistance

to integration likely worked against in-

terracial housing. Most of the

facilities attracted a young, educated, native-

born clientele with white-collar

occupations. The few units which catered to

older women holding industrial jobs

seemed marginally funded, offering little

or no support services and far less

glamorous surroundings. While segrega-

tion of the homes by race, age, and

income might have occurred as a result of

the filtering process established by the

resident's board and/or its administra-

tors, self-selection was also a likely

factor. For example, a Protestant might

have avoided homes run by Catholic

orders, while homes which featured a

large percentage of industrial workers

may have resulted from residents urging

their friends to board there.

Often there was an incongruity between the

intended clients and those actu-

ally served. For instance, though the

Sacred Heart rules required residents to

be between the ages of 14 and 30, in

1900, over 44 percent were beyond this

age. At the Anna Louise Inn, originally

founded as a residence for industrial

workers, only 18 of the 119 residents

held factory jobs. The imposing ele-

gance of the four-story mansion which

became the Glenn Industrial Home

must have been intimidating to the

unemployed transients for whom the fa-

cility was originally intended. The

Women's Home Missionary Society's

slogan of eradicating poverty by

stemming ignorance of economy and health,

and its mandatory attendance at twice

weekly religious services, doubtlessly

caused less pious workers to avoid the

home altogether.

Directors of the homes seemed unaware of

the acute need for permanent

housing facilities until their temporary

residents became increasingly long-

term. However, over time some flexible

funding agencies changed the mis-

sion of their facilities to reflect more

accurately the clients' needs. Some

75. Annie L. Roelker and Anna H. Foster,

The First Annual Report of the Girl's Friendly

Society Vacation House (n.p.: c.1904), pamphlet located at the Cincinnati

Historical Society.

Housing the Women Who Toiled 71

broadened age requirements, others set

rents on a sliding scale, while still

others provided opportunities for

unemployed women to work at the home

in exchange for rent, board, or both.

Even with the best of intentions these

homes never met the housing needs

of all single Cincinnati women workers,

particularly in the period between

1890 and 1930. As the number of rooms

increased so did the waiting lists.

For instance, in 1900 there were 35,150

Cincinnati wage-earning women

over the age of sixteen but only 165

places in planned residences.76 By

1920, through expansion and the

development of new facilities, 701 rooms

became available for the now increased

female work force of 50,231.77

Nor did planners anticipate the decline

in the need for the homes in later

decades. Eventually, as working women

gained a measure of indepedence, and

thus were more able to provide for

themselves, the homes suffered from in-

creasing vacancies and growing overhead

until, today, only one remains, the

Anna Louise Inn.

Despite its many problems, the housing

movement for women workers is

one of historical importance. It

documents a fundamental shift in American

attitudes about women's roles in the

workforce and in the cities and illustrates

how physical changes in the city and its

infrastructure indirectly influenced

those attitudes.

76. Women in Gainful Occupations, 141.

77. Mary Ferguson, "Boarding Homes

and Clubs," 191.

PATRICIA A. CARTER

Housing the Women Who Toiled: Planned

Residences for

Single Women, Cincinnati

1860-1960

The Lawrence [Home] stands as a barrier

to sickness and evil, she opens her doors

and invites the young, unprotected girl

to come in and make her home here-not

that she may be rescued as a brand from

the burning, but that she may not even get

near enough to the fire to be scorched.

She does not consider herself, nor is she

considered, a charity inmate. Her

independence and self-respect are guarded and

fostered by the management, although her

three and a-half dollars (sometimes the

larger part of her week's earning) does

not cover the expense of her maintenance.1

The above statement illustrates the

sentiments regarding many single,

women workers at the turn of the

century. Those separated from their fami-

lies and working long hours for low pay

were viewed as morally and physi-

cally vulnerable to the hazards of urban

life. By the early 1900s many cities

had established homes for unwed mothers

or reformatories for women who

"went bad." However,

residences for working women were seen, as the quote

suggests, as a preventive measures to

such deplorable outcomes. The move-

ment to provide safe and affordable housing

to single working women began

in England and moved to the U.S. in the

late nineteenth century. Throughout

the early twentieth century religious

groups and social service providers es-

tablished homes for the protection and

comfort of this new group of workers

in cities throughout the country.

Cincinnati was the third U.S. city to estab-

lish a home for women workers, when in

1858 the Sisters of Mercy founded

the House of Mercy. By 1930 at least

nineteen such institutions had opened

in the city. Though only one of the

homes still remains, this study finds

that the planned residences were

generally successful in providing their in-

tended services.

Previous research on the history of

housing for working women has tended

to focus primarily on an analysis of

specific homes and the degree to which

middle-class ideology dominated the

day-to-day interactions within them.2

Patricia Carter is on the Women's

Studies faculty at the University of Connecticut.

1. Annual Report of the Lawrence

Home, (n.p.: November 4th, 1908), 4-5.

2. M. Christine Anderson, in "Home

and Community for a Generation of Women: A Case

Study of the Cincinnati YWCA Residence,

1920-1940," Women in Cincinnati: Century of

Achievement, 1870-1970. (Cincinnati, 1987), 34-41; Lisa Fine, "Between Two

Worlds:

Business Women in a Chicago Boarding

House, 1900-1930," Journal of Social History, 19

(614) 297-2300