Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

CAROL STEINHAGEN

The Two Lives of Frances Dana Gage

In the year before her death, Frances

Dana Gage (1808-1884) wrote an auto-

biographical sketch for Woman's

Journal, the organ of the American Woman

Suffrage Association.1 It seems

appropriate that the infirm and isolated vet-

eran of so many antebellum woman's

rights campaigns would want to create

a link to the younger generation of

reformers, and to mark her place in the

history of nineteenth-century reform

movements. Gage might have character-

ized herself as an important messenger

of woman's rights ideology in the

West, a woman who delivered

"reformatory" lectures in remote areas where

the only platform was a schoolhouse. She

might have characterized herself as

an abolitionist who not only spoke for

but worked with slaves on the Sea

Islands plantations that were part of

the Port Royal experiment. She might

have characterized herself as a writer

whose poetry and newspaper correspon-

dence reached out to the working class

so often overlooked by reformers. But

Gage, in one of her last public

communications, had another aspect of her life

in mind. She wanted to assure readers

that she was not the daughter of a

cooper.

The provocation for this seemingly petty

concern was the publication, fif-

teen years earlier, of a tribute to Gage

by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In this

tribute Stanton identified Gage's

father, Joseph Barker, as "a farmer and a

cooper," and went on to explain

that Frances had "assisted her father in mak-

ing barrels and I have heard her often

tell that, as she would roll out a well-

made barrel, her father would pat her on

the head and say, 'Ah, Fanny, you

should have been a boy!'"2 The

story may have appealed to Stanton because

of its similarity to her own childhood

experience.3 For Frances Dana Gage,

however, the story as Stanton told it

was a distortion of history in general and

of a personal history that she had

repeatedly made part of her public corre-

spondence and lectures. In the

strident rebuttal written for Woman's

Journal, Gage declared, "As far as my knowledge goes, my

honored sire never

put a hoop even upon a

water-bucket." She went on to review his accom-

Carol Steinhagen is a Professor of

English at Marietta College.

1. "The Autobiography of Frances

Dana Gage," Woman's Journal, March 31, 1883.

2. "Frances D. Gage," in James

Parton et al., eds., Eminent Women of the Age (Hartford,

Conn., 1868), 383.

3. Stanton's efforts to please her

father by acting as would a son are recounted in Elisabeth

Griffith. In Her Own Right: The Life

of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (New York, 1984), 7-13.

The Two Lives of Fances Dana Gage 23

plishments--Ohio legislator, judge,

carpenter, inventor, pioneer settler of the

trans-Appalachian region, and farmer.

Her experience as a cooper, she re-

ported, was limited to making one

barrel. For this accomplishment her father

reprimanded her severely and sent her

back to the house. As she returned to

her proper place she heard him say to

the cooper, "What a pity she was not a

boy!"

Why was it so important for Frances Dana

Gage to tell the story of the bar-

rel-making episode in an

autobiographical sketch that concentrated on her an-

cestry more than on her accomplishments?

The answers to this question re-

flect not only on Gage's role as a

pioneer female activist but also on her

generation of antebellum reformers. One

answer lies in considering the im-

portance of autobiography for Gage and

her colleagues. They established,

through stories of personal history, the

collective historical basis for rejection

of social and legal barriers to women's

advancement. At the conclusion of

her story Gage declared, "Then and

there sprang up my hatred to the limita-

tions of sex. Then and there the

foundation was laid for all my woman suf-

frage work, which began in 1818, when I

was ten years old." Such claims

were not unique to Gage. As Blanche

Glassman Hersh observes of feminist-

abolitionists, "Most were

characterized as 'rebellious' and 'strong-minded' be-

cause they insisted on sharing in their

brothers' play and work. ... Bright

and achieving, most had been told by a

parent: 'What a pity you were not a

boy!'"4 This prototype

of female experience was so important to Gage that

she repeatedly told her barrel-making

story, each time with variations, until

it stands as a legend in her own

history.5

In addition to legitimating rebellion,

however, Gage's story established her

identity as part of a dynamic nation's

ruling class. Just as Gage embedded her

personal story in a celebration of her

pioneer father's heritage and achieve-

ments, so, according to Hersh, did her

fellow feminist abolitionists take pride

in their Yankee roots. "Their sense

of heritage gave them an aura of righ-

teousness and superiority, but it also

contributed to feelings of security and

self-confidence which enabled them to

survive in the face of hostility and dis-

4. The Slavery of Sex:

Feminist-Abolitionists in America (Urbana, Ill., 1978), 134.

5. Variations and/or repetitions of the

legend may be found in Frances D. Gage to S. S.

Barry, Una, December 1853;

"Address of Frances D. Gage," Proceedings of the

First

Anniversary of the American Equal

Rights Association Held at the Church of the Puritans, New

York, May 9 and 10, 1867 (New York, 1867), 66 [Cited hereafter as Proceedings.];

Celia

Burleigh, "People Worth Knowing-No.

2," Woman's Journal, July 9, 1870; Phebe A.

Hanaford, "Women Reformers," Daughters

of America, or Women of the Century (Augusta,

Maine, 1883), 340; Elizabeth Cady

Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds.,

The History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 2 (Rochester, N.Y., 1889), 224; Nettie T. Henery,

"Aunt

Fanny Gage: The Story of a Famous

McConnelsville Woman," Typescript written for the

Morgan County Herald, December 28, 1937, 6, Simpson Morgan Country Library,

McConnelsville; Eugene Roseboom,

"Frances Dana Gage," Notable American Women, 1607-

1950, Vol. 2 (Cambridge, Mass., 1971), 2-3.

24 OHIO HISTORY

approval."6 Thus, the very

"lords of creation," whose command of laws and

customs provoked their granddaughters'

and daughters' rebellion, were also a

mainstay for those defiant descendants.

Surely Gage, in celebrating her

rebellious spirit and the authority of her fa-

ther, was not consciously aware of

contradiction. Nor was she consciously

aware of the conflict underlying the

reform enterprise to which she devoted

much of her adult life. That conflict,

however, is echoed in her autobiograph-

ical sketch and may help to account for

her fixation on the barrel-making

story. In the image of the precocious

ten-year-old rejecting the boundaries of

the sphere designated for her sex is

also the image of a girl whose identity

was shaped by those boundaries.

Surrounded by the environment she loved,

the legendary young Fanny Barker is an

apt model of her real-life adult coun-

terpart and many other women who challenged

"the limitations of sex" in the

second and third quarters of the

nineteenth century. On the one hand Gage and

her cohorts defied the restrictions

imposed by law and by woman's sphere ide-

ology, and sought access to public

spheres as a means of overcoming these

restrictions. On the other hand they

found in the woman's sphere a source of

legitimacy, stability and solace. In

repeating the story of her introduction to

the public arena of woman's rights

activism, Gage revealed her dependence on

the woman's sphere-the home and the

patriarchal system that established the

home as a sanctuary for women. The

seemingly strange focus of her autobi-

ographical sketch represents the double

life she lived as a public figure. She

was committed to rejecting the concept

of separate spheres of action for men

and women, but she developed a public

persona that represented the virtues of

domesticity promoted by woman's sphere

ideology.

Gage's ties to the woman's sphere were

established by her experience in

two homes that shaped the fundamentals

of her character. Her original home

was the farm on the banks of the

Muskingum River outside Marietta, Ohio,

where the barrel-making story was set.

This home fostered her essential val-

ues. Here she developed an appreciation

for the importance of her Barker and

Dana ancestors' role in settling what

was, after the Revolutionary War, the

West. Here she developed gendered

values, inheriting from her mother and

grandmother Dana a sympathy for the

oppressed, and from her father an appre-

ciation of the intellectual heritage of

England.7 Here she came to relish in-

vigorating labor, for, although she was

discouraged from cooperage, she was

allowed to milk cows and plow fields.8

Such experiences, which she later

6. The Slavery of Sex, 121-22.

7. "The Autobiography of Frances D.

Gage"; L. P. Brockett and Mary C. Vaughan,

Woman's Work--in the Civil War: A Record of Heroism, Patriotism and Patience (Philadelphia,

1867), 683-84;

"Memoir of Frances Dana Barker," Janney Family

Papers, Mss, 142, Box 3/7,

Ohio Historical Society.

8. Burleigh, "People Worth

Knowing"; Frances D. Gage, "Woman's Sphere--What

Mrs.

Jones Said About It," Ohio

Cultvitator, January 1, 1851.

|

The Two Lives of Fances Dana Gage 25 |

|

|

|

characterized as early steps beyond the woman's sphere boundaries, reflect the realities of agrarian life unrefined by the guidelines for appropriate gender be- havior that were popularized in ladies' magazines. In the Barker household agricultural and domestic tasks were closely integrated. According to Frances's sister Catherine, "Many girls that I knew were smart enough, to spin and weave flannel and exchange it for calico for dresses. My mother thought it not good economy for us, but we milked the cows and made butter and cheese to do it."9 Living on a farm on the banks of the Muskingum also gave Fanny Barker a literal sense of freedom. Here she had "ample opportunity for indulging her love of outdoor life," which she preferred to the "dull monotonies of indoor life."l0 Freedom for young Fanny meant rushing through lessons in order to have "time to play and be in all sorts of mischiefs and every bad scrape that turned up in school."ll But it also meant hiding in the garret, "where thoughts could flow free," to write.12 If Fanny Barker was a "pest" and "the worst child that ever lived,' 13 she also impressed her neighbors (unfavorably) as a girl who "will want to get her side saddle on a comets tail and ride after a

9. Catherine Barker, "Written by Hand," Autobiography ms. B-57, Vol. 1, 8, Dawes Library Special Collections, Marietta College. 10. "Memoir of Frances Dana Barker," Janney Family Papers. 11. Barker, "Written by Hand," Vol. 1, 11. 12. Ibid., 12. 13. Burleigh, "People Worth Knowing." |

26 OHIO

HISTORY

bit."14 Although her

country home did not shelter her from criticism of be-

havior inappropriate for a girl, it did

foster energy and nourish "her lofty aspi-

rations." 15 It was a home she

yearned for throughout her life.16

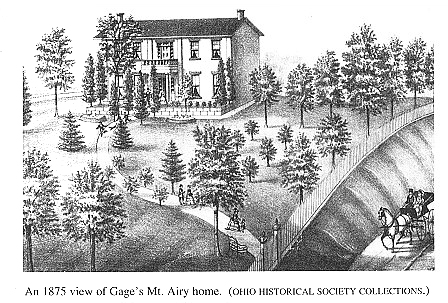

Her second important home was a large

brick house called Mount Airy that

loomed over the village of

McConnelsville, Ohio.17 Here Frances Dana

Barker Gage lived a fairly conventional

life in the first two decades of her mar-

riage to attorney and entrepreneur James

Lampson Gage (1800-1863).

Married at the age of twenty on January

1, 1829, she had eight children by

July 1842.18 The early years of her

marriage were consumed with the tasks

of mothering and keeping house, which

included taking in boarders. As she

complained to her sister Charlotte,

I have had no girl [housekeeping

assistant] for 2 months chick nor child but have

done

My washing baking brewing

Frying boiling roasting all myself.19

Scrubbing sweeping stewing

Whipping scolding toasting

Although full-time housekeeping and

mothering gave Frances Gage a large

measure of the "dull monotonies of

indoor life," she boasted that "few could

perform half the labor in the same time,

none plan so well, or meet more

readily every emergency."20 In

this home too Gage thrived, finding ample

occupation for her energies.

Proud as she was of her accomplishments

at Mount Airy, Gage wanted, as

she liked to put it, to "say my

say." The opportunity to write poetry and let-

ters for local and regional newspapers

meant that she no longer had to hide in

a garret to "scribble."

Writing for the papers in the late 1840s allowed Gage

to test the boundaries of the domestic

sphere. "If I can't make a commotion

in the midst of the sea, I can throw my

pebble into the edge of the ocean, and

who knows but the eddying ripples may

widen their circles, till they reach ...

the enormous verge of the waters of

life," she declared in 1852.21 Her

desire

to enter the "ocean" of

political activity was heightened when, on a trip to the

14. Barker, "Written by Hand,"

Vol. 1, 14.

15. "Memoir of Frances Dana

Barker," Janney Family Papers.

16. This yearning is a major theme of

Gage's poetry.

17. So fond was Gage of Mount Airy that

she gave this name to the family's second St. Louis

home, where she tried to recreate the

conditions of the first Mount Airy.

18. Genealogical information about the

Gages' children may be found in Richard Dana

Benton, compiler, The Danas and the

Dana Farm (privately printed, 1991), Washington County

(Ohio) Historical Society.

19. Gage to Charlotte C. Barker, n.d.

[probably late 1832], Collection of Jerry Devol.

Devola, Ohio. Note: Gage's letters were

never dated by year, and some lack any date. Dates

inferred from internal evidence will be

bracketed.

20. "Memoir of Frances Dana

Barker," Janney Family Papers.

21. Gage to Amelia Bloomer, Lily, 4

(March, 1852), 19.

The Two Lives of Fances Dana

Gage 27

Northeast with her husband and

father-in-law, she read a newspaper account of

the Seneca Falls convention of July

1848, the first convention organized to

advance the cause of women's rights.

Later, in her address to the Massillon,

Ohio, Woman's Rights Convention of 1852,

Gage reported that her friends

thought her "crazy" for

wishing she had gone to Seneca Falls. She, however,

could see the convention only as a sign

of hope that she could soon escape

from her "straight jacket."

This metaphor aptly characterizes the whalebone

corsets she wore in compliance with

fashion dictates and her sense of being

restrained by censure of her audacious

opinions.22

Even in the village of McConnelsville,

far from eastern cities where wom-

an's rights advocates found allies and

guidance among organized abolitionists

and temperance reformers, Gage was able

to make inroads into the public

sphere of politics. Before moving to St.

Louis, Missouri, in 1853, Gage was

instrumental in organizing three woman's

rights conventions in rural Ohio

(McConnelsville, Chesterfield, and Mount

Gilead), and she presided over two

important urban conventions in Akron and

Massillon.23 Her characterization

of the reputation she gained from such

activities is not only an interesting ad-

dition to the public record, it also

reflects her self-consciousness about her in-

cursions into the public sphere.

Gage's official entry into southeastern

Ohio politics was the May 29,

1850, woman's rights convention that she

and three other McConnelsville

women organized. They were able to

attract some seventy women to the

Masonic Hall and write a memorial

requesting that the words "white" and

"male" be omitted from the new

Ohio Constitution.24 Both the local Morgan

Herald and the Marietta Intelligencer took respectful

notice of the proceedings.

The Intelligencer estimated a

crowd of one to two hundred, "an array of

beauty" such as no political

convention ever assembled could boast.25

The

Morgan Herald reported that the resolution calling for woman suffrage

on the

principle of no taxation without

representation "called forth considerable dis-

cussion," but that objections were

addressed and "briefly and ably answered"

by F. D. Gage. The Herald added

that the memorial to the constitutional

convention was signed "by nearly

all present."26

In recalling the McConnelsville

convention years later, however, Gage took

a less sanguine view of her persuasive

skills. She remembered only forty

signatures on the memorial, and

emphasized her alienation from the commu-

nity. "My notoriety as an

Abolitionist made it difficult for me to reach peo-

22. George Gage, "Diary,

1848-49," Ms. 2385, Ohio Historical Society; Anti-Slavery Bugle,

June 5, 1852.

23. Ibid.; History of Woman Suffrage,

Vol. 1, 112-18.

24. History of Woman Suffrage, Vol.

1, 117. The other women were Hettie M. Little, Mary

T. Corner, and Harriet Brewster.

25. Marietta Intelligencer, June

6, 1850.

26. Morgan Herald, June 6, 1850.

28 OHIO

HISTORY

pie at home. and, consequently, I had to

work through press and social circle

.... For years I had been talking and

writing, and people were used to my

craziness.' But who expected Mrs. Corner

and others to take such a stand!

Of course, we were heartily

abused."27 This characterization, like her remarks

about local reaction to her interest in

the Seneca Falls convention, empha-

sizes the punishment Gage suffered for

taking unpopular public stands. A

tribute she wrote for her husband

reinforces the idea that to be a reformer in

McConnelsville was to be alienated.

"In those days, on the very borders of

slavedom, it required much nerve to be

true, and to stand alone. No Anti-

Slavery Society gave its support to the

isolated Abolitionist, who . . . stood

as it were the picket guard upon the

outpost of Freedom."28 This

statement

ignores the active network of

Underground Railroad agents and supporters in

the area, as well as the Western

Anti-Slavery Society, which, apparently,

Gage neverjoined.29 When she

moved to St. Louis she felt even more iso-

lated, complaining to fellow reformer

Rebecca Janney, "I have no helpers or

workers here, not the half you have in

Ohio . . . and they treat [me] in the

main as if I were a wild beast."30 Later Gage claimed, in Woman's Work in

the Civil War, that "it never seemed to her to require any

sacrifice to resist the

popular will." yet she went on to

detail several such sacrifices. She reported

that her bold stands on behalf of

abolitionism caused her to be fired as a corre-

spondent from three newspapers, the Ohio State Journal, the Missouri

Republican and the Missouri Democrat. She also claimed that

her bold ex-

pression of political views in St. Louis

had provoked personal threats and

three acts of arson against the Gages'

property.31

Certainly Gage did suffer public and

personal rebuke for her advocacy of

feminist, abolitionist, and temperance

sentiments. But her self-characteriza-

tion as a crazy lady and wild beast

overlooks her reputation as genial Aunt

Fanny, "a 'womanly woman,' highly

appreciated by the common people,"

27. History of Woman Suffrage, Vol.

1, 117. A record of the "abuse" of which Gage speaks

is found in a June 27, 1850, letter to

the Morgan Herald from three

unnamed men who belittled

the report of the convention and called

Gage a "very sarcastic" woman who made "unnatural

assertions" and "violent

censure."

28. National Anti-Slavery Standard, June

6, 1864.

29. Information about Underground

Railroad activities in Morgan County may be found in

Eck Humphries, The Underground

Railroad (McConnelsville, Ohio, 1931) and Wilbur Henry

Siebert, The Mysteries of Ohio's Underground

Railroads (Columbus, Ohio, 1951). No record

of Gage's involvement is found in

reports of the Western Anti-Slavery Society in the Anti-

Slavely Bugle throughout

the 1850s.

30. Gage to Janney, May 11 [1855],

Janney Family Papers, Mss. 142, Box 4/5.

31. Brockett and Vaughn, 684-88. The

claims of arson are difficult to substantiate. A

search of the Missouri Republican and

the Missouri Democrat yielded only one instance of fire

damage to Gage property. This, as

reported in the Democrat, September 2, 1856, was a fire

ignited in either tenements or a stable

that spread to, among other places, James Gage's

foundry. It seems unlikely that a

politically motivated arsonist would have burned poor peo-

ple's lodgings to send a message to

Frances Dana Gage. It is possible, though, that arsonists

started small fires too insignificant to

be reported in the papers.

The Two Lives of Fances Dana

Gage 29

"so well and favorably known

throughout the country, as a chaste and beauti-

ful writer, and as one of the ablest

advocates of reform known to the Press."32

Her emphasis on the cost of taking

unpopular stands reflects her admiration

for defiance of public opinion in the

name of truth and duty. The call to "dare

to 'stand alone,"' issued in the

poem "Stand for the Right" and similar poetic

proclamations, expressed approval of the

kind of public stands that merit cen-

sure and rejection.33 But such

proclamations may have masked her desire to

be accepted. As Gage revealed in a

letter to Susan B. Anthony, she hoped

that she, like Lucretia Mott, would be

able to work long for the cause of

woman's rights and be loved by the

people for what she had done.34 The po-

sition of one who stands alone is

fundamentally at odds with this desire and

with the image of Aunt Fanny upon which

her contemporary reputation

rested.

What emerges in Gage's declamatory

poetry and her personal stories of au-

dacity is a consciously crafted image of

a woman committed from her youth

to break out of the boundaries of the

woman's sphere in order to do her moral

duty, regardless of the personal costs.

This self-image underscores Gage's be-

lief that she and all women, divinely

designated as they were to determine the

mental, moral, and physical character of

every human being, had a responsi-

bility to work publicly on behalf of

reform. "Come out, then, Oh! my sis-

ters, from the quiet sheltered nooks of

domestic life," she called, urging

women to agitate on behalf of temperance

legislation. The ideal consequence

of such work would be the spread of

woman's influence beyond the home,

where it was of limited value, and into

the political and social arenas, where it

could effect sobriety, equality, and

improved education.35 What the declama-

tory poetry and personal stories do not

reveal, however, is Gage's apprehen-

sion that public arenas undermined the

security and assurance of moral superi-

ority that was nurtured within the home.

Gage gave veiled expression to this

apprehension in the poem "I Live Two

Lives."36 Overtly, the

poem contrasts two visions: one (stanzas one through

seven) informed by a perception of all

the nation's ills--intemperance, slav-

ery, war, female irresponsibility; the

other (stanzas eight through thirteen) in-

formed by faith in God that these ills

will be rectified when the domestic

virtue of love "blends" with

the call to duty. This blending of love and duty

32. W. H. Venable, Beginnings of

Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley: Historical and

Biographical Sketches (Cincinnati, Ohio, 1891), 280; Missouri Democrat, April 2, 1855.

33. First published in the Morgan

Herald, June 13, 1850. According to Woman's Work in the

Civil War, 685, this poem was written in answer to a Congressman

who wanted Gage to use her

influence in getting her husband

"to yield a point of principle."

34. Gage to Anthony. March 7, [1856],

Frances Dana Gage Papers, Schlesinger Library,

Radcliffe College.

35. Gage to New York Woman's Temperance

Convention, Lily, 4 (May, 1852), 37-38; Gage

to Amelia Bloomer, Lily, 4

(April, 1852), 26.

36. National Anti-Slavery Standard, February

7, 1862.

30 OHIO

HISTORY

would signal the ideal union of the

private and public spheres, a union that

would allow a reformer like Gage to live

one life governed by laws and cus-

toms shaped by female influence. The

poem, however, emphasizes disunity

rather than unity, two lives rather than

one. Although its vision of faith is

overtly triumphant, its structure

isolates this vision from descriptions of "the

inebriate's hell," the "groans

of bondmen," and the "red thunder" of war, mak-

ing these evils seem resistant to the

influence of faith and love. Gage's

rhetoric reinforces the division. The

first half of the poem employs the over-

wrought language characteristic of

contemporary reform rhetoric. The second

half is imbued with the sentimental

rhetoric that was conventionally used to

promote the virtues of domesticity. The

image of "dear woman" "lifting the

lowest to our God still nigher / Making

all earth more beautiful" by

"watching, tending / On all the

weak who fall" is Gage's version of the do-

mestic savior. The domestic ideology of

her time dictated that this savior

confine her mission to the home.

Although Gage was committed to extend-

ing the range of her mission, she had

difficulty envisioning a time in which

"dear woman" was not isolated

and protected from the world she was destined

to save.

A more overt expression of Gage's

apprehension about entering the public

sphere is found in a series of reports

to the Missouri Republican on an 1854

trip to New Orleans.37 The

series as a whole suggests the disjunction of her

two lives in that it omits any reference

to her historically significant speech

in New Orleans, the first woman's rights

lecture given in the Deep South.38

While she freely discussed the lecture

in Una, "A Paper Devoted to the

Celebration of Women," she cleansed

her Republican reports of overtly polit-

ical content.39 One episode within the

series is especially significant because

it concentrates on fear of the mobility

that was crucial to the success of the

reform enterprise. Usually Gage took the

difficulties of travel in stride as she

made her way from one lecture or

convention site to another, even when the

overturning of a carriage in September

1864 left her seriously injured.40

In

this report, however, she revealed her

ambivalence about assuming the free-

dom to go where she pleased.

Noting the benefit of travel for

developing her philosophical perspective on

"the migratory portions of our

restless world," she went on to report one of

37. Missouri Republican, March 24,

26, 27, 30, 1854, and April 2, 1854.

38. Diane Van Skiver Gagel, "Ohio

Women Unite: The Salem Convention of 1850,"

Women in Ohio History (Columbus, Ohio, 1976), 6-7. As Gage admitted in a May

1854 report

to Una, and as the New Orleans Daily

Picayune of March 17, 1854, reported with some satis-

faction, her audience in Lyceum Hall was

very small. She spoke on the social, industrial, and

civil disabilities of U.S. women.

39. Una, May 1854. It is possible

that her editors excised a report of her New Orleans

speech, but such self-censorship was

characteristic of Gage's newspaper correspondence in

St. Louis.

40. National Anti-Slavery Standard, October

22, 1864.

The Two Lives of Fances Dana Gage 31

the "unavoidable, but very

unpleasant" accidents to which the traveler is vul-

nerable. She had found herself alone on

the steamboat Martha Jewett when

her traveling companion, her son, had

failed to get on board. Contemplating

the prospect that no one would miss her

if she disappeared, she was drawn to

the inscription over the ladies' saloon:

"Be kind to the loved ones at home,"

and a plaque containing the boat's name.

Discovering this to be the name of

the captain's sister, Gage felt

bolstered by the power of domestic virtue.

Ah! thought 1-the man who can thus

consecrate himself to the holiest tie of life,

and put the name of a beloved sister

where it will be an hourly remembrancer of

childhood, of innocence, of home; the

mind that would conceive the idea of plac-

ing that beautiful sentiment . . . ever

before the gaze of the pleasure-seeking,

money-loving crowd, must be kind and

sympathizing.41

This overt expression of the consolation

of domestic ideology shows how

Gage could make public use of the

concept of private virtue. It also shows

her appreciation of the power of female

influence, as it was defined by this

ideology, to oppose the acquisitive

values associated with the marketplace.42

She was not alone among her political

colleagues in appreciating the concept

of separate spheres of influence for

women and men. As Paula Baker points

out, the social construct of the home

sphere was congenial to many nine-

teenth century women because "it

encouraged a sense of community and re-

sponsibility toward all women, and it

furnished a basis for political action."43

Underlying the concept of separate

spheres was the post-Revolution principle

of republican motherhood, which promised

a measure of empowerment for

women in the emerging nation by

recognizing mothers' role in educating the

future leaders of the republic.44 When

Frances Gage entered the public arenas

of the press, lecture sites, and

convention halls, she could draw on this his-

tory of respect for female influence

without seriously violating contemporary

notions of woman's proper place. She

could ask Ohio Cultivator readers if

they had made themselves fit for the "great

work" of becoming mothers of

"the agriculturist, the mechanic,

the manufacturer, the artisan, the statesman,

the professional man, and laborers of

both sexes."45 As long as she empha-

sized maternal prerogatives, she did not

risk being labeled crazy, and she could

keep her public and private lives in

balance.

41. Missouri Republican, April 2, 1854.

42. For a summary of the relationship

between domestic and marketplace values see Nancy

Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood (New

Haven, 1977), 67-70.

43. "The Domestication of Politics:

Women and American Political Society, 1780-1920,"

American Historical Review, 89 (June, 1984), 632. See also Mary P. Ryan, The

Empire of the

Mother: American Writing About

Domesticity, 1830-1860 (New York,

1982), 111.

44. Sara M. Evans, in Born for

Liberty: A History of Women in America (New York, 1989),

57, offers a lucid definition of this

concept.

45. "Life Springs of Health and

Usefulness," Ohio Cultivator, February 1, 1859.

32 OHIO HISTORY

Such balance, however, depended upon a

community receptive to female in-

fluence, a community that was an

extension of the homes of which it was

composed. Gage's temperance fiction

allowed her to create such a commu-

nity.46 The background of the

novel Elsie Magoon, for instance, is based

upon her memories of the Marietta area

in the early nineteenth century,

memories shaped to allow the novel's female

protagonists to gain moral sway

over the community. Elsie Magoon was

empowered by the grief that liquor

brought to her world to take charge of

her family and play a role in the com-

munity.

And so she toiled on, patient and

strong, striving to her utmost to rectify her hus-

band's mistakes; to think for him and

plan for him-working earnestly for the

good of all, conscientiously believing

that what was for the happiness of the

neighborhood, was for the happiness of

her household. Hence she was often com-

pelled to take a bold stand against what

seemed to be the immediate interest of her

husband.47

Beyond the world of fiction, however,

such an ideal balance of private and

public spheres did not exist. As Gage

made bolder strides into the political

arena she lost touch with the community

of pioneers that she liked to ideal-

ize, the community where "No party

feuds or politics / Disturbed their quiet

joys" and neighbors "lived

[like] a band of brothers."48 The Gage family's

move to St. Louis in 1853 confirmed the

loss. This move deserves examina-

tion not only because it broke Frances

Gage's ties to her most significant

homes, but because it represents the

general sense of dislocation that attended

entrepreneurial activity and westward

expansion in the antebellum years. Just

as this move aggravated the division

between Gage's two lives, so the mobil-

ity of a growing nation aggravated the

conditions that gave rise to the separate

spheres.

The historical context of women's-sphere

ideology, now commonly called

the cult of domesticity, was the

beginning, in the 1820s, of the long and

gradual process of the nation's shift

from an agrarian to an industrial econ-

omy. The movement to cities necessitated

by this shift weakened rural com-

munities like McConnelsville. The cult

of domesticity helped the nation to

reconcile itself to change dictated by

economic forces because it emphasized

the home as an unchanging moral force in

society. As Mary P. Ryan ex-

plains, "The cult celebrated and

prescribed intense and tenacious bonding with-

46. It should be noted that not all

Gage's temperance fiction had the feminist slant discussed

here. Much of it rehearsed the conventional

temperance format, outlining the process of a

man's bringing his family to ruin by

giving into the temptation of social drinking.

47. Elsie Magoon, or The Old

Still-House in the Hollow, A Tale of the Past (Philadelphia,

1867), 74.

48. Frances D. Gage, "When This Old

Ring Was New," Missouri Republican, May 29, 1853.

The Two Lives of

Fances Dana Gage 33

in the newly

constituted, mobile, nuclear family as a compensation for the

network of kin and

neighbors left behind."49

As the private

correspondence of both Frances Gage and her sister Catherine

Barker reveals, the

Gage-Barker network of kin in Morgan County was af-

fected by economic

insecurity.50 When Catherine and Francis Barker, hoping

to recover from their

debts, moved their family to Iowa, Frances Gage hoped

to follow them.51

Her husband's interest in the prospects of the West is indi-

cated by a letter he

submitted to the Morgan Herald from a California immi-

grant who described

the economic potential of the state.52 Indeed, James L.

Gage might be seen as

an embodiment of the restless spirit of the time.

During the years he

lived in McConnelsville he served as prosecuting attor-

ney, associate judge,

mayor, and foundry owner.53 The failure of his business

did not dampen his

entrepreneurial spirit; he looked to the railroad industry in

St. Louis as a new

source of opportunity. Here

he established the first car

wheel foundry west of

the Mississippi.54 His

celebratory attitude toward

progress is revealed

in his prediction in a local newspaper that the "real

Pacific road . . .

will be more lasting than the Pyramids of Egypt, or the

Chinese Wall."55

Although Frances Dana

Gage had written a popular poem, "Don't Go to

California," that

admonished opportunity seekers to "Stay home and gather

gold," and

although she dreaded leaving her ancestral land for a slave state, she

generally espoused

progressive views.56 The move to St. Louis heightened

her enthusiasm for the

prospects of westward expansion, and she reported to

the "Cultivator

girls" in Ohio successful business ventures that exemplified

the virtues upon which

achievement rested: industry, perseverance, and sobri-

ety.57 Her

public correspondence frequently contained blatant advertising for

products whose

efficiency, she claimed, would enable women to devote their

time to pursuits more

profitable than drudgery. The report entitled "Woman's

Rights and Patent

Washing Machine" illustrates her faith in machinery as an

agent of reform.58

49. The Empire of

the Mother, 45.

50. Catherine Barker's

autobiography includes descriptions of her husband's attempts to get

established in

business and correspondence from her sister that reveals Frances's ongoing con-

cern about her

husband's debts. See especially Vol. 2, 65; Vol. 3, 93-94.

51. Ibid., Vol. 3, 9.

52. Letter from

Erastus Everett, November 26, 1852.

53. Charles Robertson,

History of Morgan County, Ohio, with Portraits and Biographical

Sketches of some of

its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Chicago,

1886), 256.

54. Annual Review

of the Commerce of St. Louis, for the Year 1854 (St. Louis, 1855), 33.

55. Missouri

Republican, September 3, 1854.

56. Ohio

Cultivator, May 15, 1852. Frances D. Gage to Rebecca Janney, October 29,

[1852], Janney Family

Papers.

57. Ohio

Cultivator, July 1, 1855. July 15, 1855.

58. Frances D. Gage, Missouri

Republican, December 30, 1853.

34 OHIO

HISTORY

Unfortunately for the Gages, the

personal and cultural hopes represented by

the move to St. Louis were dashed by the

failure of James's second foundry,

and the Gages joined a general exodus

back to the East that was precipitated

by the financial panic of 1857.59 The home to which they retreated in

Carbondale, Illinois, was

"unpapered, unplastered, unlathed," and surrounded

by "a wilderness of dry bones, old

rags, [and] shoes"-a sorry mockery of the

Mount Airy Gage had lovingly described

in the Ohio Cultivator.60

As Gage

struggled to support the family that

remained with her by seeking lecture en-

gagements and opportunities to publish

her writing, she became acquainted

with the practical demands of the world

beyond the home.61 Access to public

spheres was not only a right she sought

as a female reformer, it was a neces-

sity for economic survival.62 Historical and economic forces combined to

leave Gage, on the eve of the Civil War,

without the home and community

that had sustained her hope for an ideal

union of domestic virtue and public

responsibility.

These conditions, however, spurred Gage

to do the most effective public

work of her life. She was never one to

remain despondent for long, and, as

she told her friend Rebecca Janney,

"when one resourse fails I can & will turn

to another-even [if] it has to be the

wash tub."63 The

invitation to edit the

Home Department of the Ohio

Cultivator saved her from the washtub and

brought her back to her native state. In

Columbus she appeared before the

Ohio Senate to promote legislation

protecting married women's rights,64 and

was engaged in a variety of efforts to

aid the Union cause. When she was re-

leased from her Cultivator contract

because of the paper's reduced circulation,

she sought a more active role in the

war. For the first time in her public ca-

reer, Gage gave the cause of the slave

her greatest attention. Learning of the

efforts to educate the

"contraband" population of the Sea Islands after the

North had recaptured this area in 1861,

she wrote to freedmen's associations

in Boston, New York and Philadelphia

seeking permission to go to Port

Royal. Finding no support from this

quarter, she wrote to such politicians as

59. The failure of the foundry is

discussed in, among other sources, Hannah M. T. Cutler's

eulogy for Gage, Woman's Journal,

December 13, 1884; and "Aunt Fanny's Greeting," Ohio

Cultivator, January 1, 1861. The aftermath of the panic of 1857 is

described in Jeffrey S.

Adler, Yankee Merchants and the

Making of the Urban West: The Rise and Fall of Antebellum

St. Louis (Cambridge, Mass., 1991), 151-52.

60. Frances D. Gage to Charlotte Fowler

Wells, May 21, [1860], Fowler and Wells Families

Papers, #97, Division of Rare and

Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. (The

quotation is punctuated for clarity.)

61. Frances D. Gage to Charlotte Fowler

Wells, February 12, [1860], Ibid.; Gage to William

Lloyd Garrison, June 17, [1859], Ms. A

1.2.29.63, Rare Books and Manuscripts Department,

Boston Public Library; Gage to Rebecca

Janney, July 7, [1860], Janney Family Papers.

62. "Address of Frances D. Gage,"

Proceedings, 65.

63. Gage to Janney, n.d. [1859], Janney

Family Papers.

64. Ohio State Journal, February

2, 1861. J. Elizabeth Jones and Hannah M. T. Cutler also

spoke to the Senate at this time.

|

The Two Lives of Fances Dana Gage 35 |

|

|

|

Salmon P. Chase, Benjamin F. Wade, and Edwin M. Stanton for authoriza- tion and a ten-dollar donation. After she "got leave to go and do and be any- thing [she] pleased," she was appointed by General Rufus Saxton to the post of General Superintendent of the 4th Division, Paris Island plantations.65 Her work in supervising the education of former slaves, her lecturing on their behalf, and her efforts to help establish the American Equal Rights Association after the war cap a public career that was halted when Gage had a stroke on July 26, 1867.66 When the accomplishments of Frances Dana Gage's public life are consid- ered along with those of her more famous colleagues, it seems fair to say that

65. Burleigh, "People Worth Knowing": Cutler, Eulogy for Frances D. Gage; "Address of Frances D. Gage," Proceedings, 26. 66. Burleigh, "People Worth Knowing": National Anti-Slavery Standard, August 24, 1867. Even though her mobility was limited by the stroke, Gage supported the causes of woman suf- frage and temperance by writing supportive letters to conventions and submitting commentary to Woman's Journal. In 1873, 1874, and 1875 she was able to attend some conventions. |

36 OHIO HISTORY

she did not fulfill her desire to be

revered as was Lucretia Mott. Nor did she

have the ideological grasp of issues

evident in the writings of Elizabeth Cady

Stanton, or the management skills and

singleness of purpose attributed to

Susan B. Anthony. Gage's chief

contribution to the cause of woman's rights

may lie in her means of addressing the

conflict between her two lives, private

and public, and the two lives of all her

contemporaries who sought to expand

women's opportunities without

undermining the cultural basis of respect for

woman. She did this by making her

private self public, by creating a public

identity based upon her experience as a

housekeeper, mother, and reformer.

By the time she was widely known as

"Aunt Fanny," in the early 1850s, she

could appear in the press and on the

platform as Frances Dana Gage and still

be recognized as the woman who had

initially communicated with the public

as if they were part of her kinship

network. In this manner she compensated

in part for the loss of home and

community that such activism intensified.

She found in newspapers, even those

unsympathetic to her politics, a fo-

rum for making public her personal life.

Newspapers that espoused liberal

causes were a more congenial forum, for

in these she could freely express her

political sentiments. In communicating to the National

Anti-Slavery

Standard about her work with the freedmen, for instance, she

could integrate

the political and the personal.

Reporting on the success of a late- 1863 speak-

ing campaign in upstate New York, she

warned Standard readers that "the

work of emancipating the slave is only

part of our duty; he must be taken by

the hand and taught the ways of freedom,

as we would teach the child the

ways of life." Condescending as

this rhetoric may seem, it reflects Gage's ex-

tension into a public sphere of her

sense of maternal duty. (She also called

the nation as a whole children.67)

In the same report she revealed her sadness

over the loss of her husband and the

scattering of her children. Her lament

that her sons were on the battlefield

and her old home was in the hands of

strangers gave a sense of personal commitment

to her interest in making citi-

zens of former slaves.68

The forum most congenial for Gage's

public performance of self was the

letter format she developed for readers

of a Whig paper, the Ohio State

Journal, and an agricultural paper, the Ohio Cultivator. The

political paper

seems an anomalous context for Gage's

contributions-both her poetry,

which was primarily sentimental, and her

series "Letters from the Kitchen,"

inaugurated in March 1850. But the

political context of her personal com-

munication aptly represents the

conjunction of her two lives. In writing the

letters from her home, she borrowed

consciously from the popular epistolary

67. See, for instance, "A Few

Thoughts About the War," National Anti-Slavery Standard,

August 1, 1863.

68. Ibid., December 5. 1863.

The Two Lives of Fances Dana

Gage 37

style, especially Jane Swisshelm's

"Letters to Country Girls."69

She wrote

from the kitchen because it was the site

of some of her best hours, because

she wanted to show the necessity and

dignity of women's domestic duties, and

because she wanted to prove, by teaching

means of efficient completion of

household tasks, that women in the home

could be devoted to "higher and

more intellectual duties."70 Her

choice of a political outlet rather than one of

the fashionable woman's periodicals, she

explained, was based on her lack of

notoriety and a desire to appeal to the

common people, for the fashionable

magazines appealed to "the upper

ten thousand."71 A similar

sentiment and

sense of mission informed her letters to

the "Cultivator girls" from Aunt

Fanny. In the Ohio Cultivator she

enjoyed the support of editor M. B.

Bateham's wife Josephine, whose Ladies'

Department addressed issues of edu-

cation, health, work, wages, peace,

temperance, and woman's rights, as well

as more traditional woman's fare such as

recipes and household advice.72

Aunt Fanny was one of several

contributors who assumed kinship titles or

domestic pseudonyms such as "Garden

Mary" or "Chamomile" to address their

extended family of readers.

In letters directed to working class

women, Gage was able to integrate as-

pects of her two lives and create a

bridge between her circumstances and those

of a large segment of the society she

endeavored to reform. By promoting the

importance and dignity of work done in

the home, and by showing through

personal anecdotes that such work need

not consume all a woman's energies,

Gage grounded in meaningful experience

her desire to make "woman herself .

. . more earnest for her own

freedom."73 She made feminist issues of tasks

like raising apples, washing clothes,

and making butter, appealing to women

to take pride in and demand just wages

for their labor. From a specific topic

like butter making, she could move to

consideration of larger political issues:

"One of these days we women folks

will get better wages for our work, if we

still do it well."74 Just

as work was necessary for Gage and women of her

class, so was consideration of work

essential to her concept of woman's

rights. She believed that their

unsalaried "unappreciated labor has taught

women to depreciate themselves,"

and that "women must set a true value on

themselves" if they are to assume

the full measure of their rights.75

The

Cultivator letters represented Gage's best opportunity to appeal

to women to

69. Frances D. Gage, "Letters from

the Kitchen #1," Ohio State Journal, March

1, 1850.

70. Ibid.

71. "Letters from the Kitchen

#4," Ohio State Journal, April 27, 1850.

72. Albert Lowther Demaree, The

American Agricultural Press, 1819-1860 (New York,

1941), 162-63; Frances W. Kaye,

"The Ladies' Department of the Ohio Cultivator, 1845-1855:

A Feminist Forum," Agricultural

History, 50 (April, 1976), 416.

73. Frances D. Gage, Letter to Ohio

Woman Suffrage Association, qtd. in Woman's Journal,

July 14, 1883.

74. "Letter from Mrs. Gage," Ohio

Cultivator, May 1, 1854.

75. "Aunt Fanny Responds," Ohio

Cultivator, May 15, 1860.

38 OHIO HISTORY

"prove by our works that we can ...

fill the places we ask for, and answer to

the needs of our natures."76

The Aunt Fanny persona did not allow

Gage to address the most fundamen-

tal issues underlying her commitment to

the political emancipation of

women. Most notably, it did not allow

her to analyze the cost to women of

the loss of their cultural status as

morally superior beings. Nor did Aunt

Fanny or Frances Dana Gage come to terms

with the inherent contradiction

between promotion of women's legal

equality on the basis of their home-cul-

tivated virtue and promotion of that

equality as a natural right. Although she

was nominally an advocate of natural

rights philosophy, Gage did not ques-

tion the assumptions of woman's sphere

ideology that allowed her to believe

in the power of female moral influence.

But she did question the social and

political restrictions on that

influence. By making herself the exemplar of a

woman who could transcend some of these

restrictions, by making public her

attempts to live two lives, Frances Dana

Gage helped to lead women of the

postbellum United States beyond the

boundaries of the woman's sphere.

76. Frances D. Gage, Letter to Ohio

Woman Suffrage Association.

CAROL STEINHAGEN

The Two Lives of Frances Dana Gage

In the year before her death, Frances

Dana Gage (1808-1884) wrote an auto-

biographical sketch for Woman's

Journal, the organ of the American Woman

Suffrage Association.1 It seems

appropriate that the infirm and isolated vet-

eran of so many antebellum woman's

rights campaigns would want to create

a link to the younger generation of

reformers, and to mark her place in the

history of nineteenth-century reform

movements. Gage might have character-

ized herself as an important messenger

of woman's rights ideology in the

West, a woman who delivered

"reformatory" lectures in remote areas where

the only platform was a schoolhouse. She

might have characterized herself as

an abolitionist who not only spoke for

but worked with slaves on the Sea

Islands plantations that were part of

the Port Royal experiment. She might

have characterized herself as a writer

whose poetry and newspaper correspon-

dence reached out to the working class

so often overlooked by reformers. But

Gage, in one of her last public

communications, had another aspect of her life

in mind. She wanted to assure readers

that she was not the daughter of a

cooper.

The provocation for this seemingly petty

concern was the publication, fif-

teen years earlier, of a tribute to Gage

by Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In this

tribute Stanton identified Gage's

father, Joseph Barker, as "a farmer and a

cooper," and went on to explain

that Frances had "assisted her father in mak-

ing barrels and I have heard her often

tell that, as she would roll out a well-

made barrel, her father would pat her on

the head and say, 'Ah, Fanny, you

should have been a boy!'"2 The

story may have appealed to Stanton because

of its similarity to her own childhood

experience.3 For Frances Dana Gage,

however, the story as Stanton told it

was a distortion of history in general and

of a personal history that she had

repeatedly made part of her public corre-

spondence and lectures. In the

strident rebuttal written for Woman's

Journal, Gage declared, "As far as my knowledge goes, my

honored sire never

put a hoop even upon a

water-bucket." She went on to review his accom-

Carol Steinhagen is a Professor of

English at Marietta College.

1. "The Autobiography of Frances

Dana Gage," Woman's Journal, March 31, 1883.

2. "Frances D. Gage," in James

Parton et al., eds., Eminent Women of the Age (Hartford,

Conn., 1868), 383.

3. Stanton's efforts to please her

father by acting as would a son are recounted in Elisabeth

Griffith. In Her Own Right: The Life

of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (New York, 1984), 7-13.

(614) 297-2300