Ohio History Journal

THE CINCINNATI TABLET: AN INTERPRETATION

By CHARLES C. WILLOUGHBY

The Great Horned Serpent of our American

tribes was usu-

ally considered a god of waters, lakes,

and streams. His anger

was manifested through storms, thunder,

and lightning. Forked

lightning was the darting of his

tongue. The Algonquians of

the Great Lakes believed that a monster

serpent, Gitche-Kenebig,

dwelt in these waters, who, unless

appeased with offerings, raised

a tempest, or broke the ice beneath the

feet of those trespassing

in his domain and swallowed them. When

the rivers or coastal

waters of Virginia were rough, the

priests went to the water side,

and after many outcries and invocations,

cast tobacco, copper, or

other offerings into the water to pacify

the god whom they

thought to be very angry.1

It is said that Michabo, the Algonquian

culture hero, de-

stroyed, by means of a dart, the serpent

who lived in a lake and

flooded the earth with its waters.

Michabo then clothed himself

in the skin of this foe and drove the

other serpents to the south.2

The Hidatsa made offerings to the Great

Serpent living in

the Missouri by placing poles in the

river to which robes and

blankets were attached.

The Chickasaw believed in a horned

snake, Sint-holo,3 who

lived along big creeks or in caves.

These serpents often moved

from one stream to another, and the

Indians believed that they

could cause rain in order to raise the

rivers, so as to leave their

hiding places with greater

facility. The Sint-holo is said to

have made a noise like thunder.

According to the Alabama In-

dians living in Texas, there were four

varieties of horned serpents,

distinguished by the color of their

horns. In one variety the

1 Edward Arber, ed., Works of Captain

John Smith (Edinburgh, 1910), 1, 373.

2 Daniel Garrison Brinton, Myths of

the New world, 2d ed. (New York, 1876),

122.

3 John Reed Swanton, "Social and

Religious Beliefs and Usages of the Chicka-

saw Indians," in Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report (Washington,

D. C.,

1881--), XLIV (1926), 251.

(257)

258

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

horns were yellow, in another white, in

the third red, and in the

fourth blue.

It is well known that the horned serpent

occurs in the myths

and ceremonies of various Pueblo tribes.

He was called Skatona

by the Sia, and in ancient times was

said to have eaten the people.

By the Zuni he was known as Kolowisi.

These Indians believe

the earth to be circular and surrounded

on all sides by the ocean.

The sky (stone cover) is thought to be

solid in substance and to

rest upon the earth like an inverted

bowl. Under the earth is a

system of covered waterways, all

connected with the surrounding

ocean.

Springs and lakes, which are regarded as sacred, are

openings to this system. The underground

waters are the home

of the horned serpent, Kolowisi.4

The Cherokee tell of the serpent Uktena.

It is as large as

a tree trunk and has horns on its head

and a bright blazing crest

like a diamond on its forehead. Whoever

is seen by this serpent

is so dazed by the bright light that he

runs toward the snake in-

stead of trying to escape. Even to see

the Uktena asleep is death,

not to the hunter himself but to his

family.5

The Jesuits found a legend current among

the Huron that

there existed a monster serpent,

Onniont, who wore on his fore-

head a horn that pierced rocks, trees,

hills, in short, everything

he encountered. Whoever could obtain a

piece of this horn was

very fortunate, for it was a powerful

charm and bringer of good

luck.

The Hurons confessed that none of them had been for-

tunate enough to find this monster and

break its horn, but their

neighbors, the Algonquians, furnished

them at times with small

fragments for a large consideration.6

The Algonquians seem to have been

especially successful in

their encounters with the horned

serpent, and it was a member of

this group, a Shawnee prisoner taken by

the Cherokee, who suc-

ceeded in securing the much-coveted

ulunsuti, or "diamond" from

its head in exchange for his liberty.

James Mooney says the

4 Ruth Leah Bunzel, "Zuni Original

Myths," ibid., XLVII (1929), 487.

5 James Mooney, "Myths of the

Cherokee," ibid., XIX (1897), Part 1, 287.

6 Brinton, op. cit., 119.

THE CINCINNATI TABLET 259

Cherokee still have this powerful

talisman. It is a large trans-

parent crystal with a blood-red streak

running through its center

from top to bottom. It is kept wrapped

in a whole deer skin

inside an earthen jar, hidden in a

secret cave in the mountains.7

This "diamond," or

"blazing star," on the head of Uktena,

on account of its glittering brightness,

was sometimes called

Igaguti, Daylight, but when detached and

in the hands of a con-

jurer it became Ulunsuti, transparent.

This "diamond" is doubt-

less analogous to the sun circle in the

center of the serpent head

of copper from the great mound of the

Hopewell group, and also

analogous to the fires of the

cobblestone altar in the center of

the head of the great horned serpent

mound of Adams County.8

The above references, while by no means

exhaustive, are

sufficient to indicate the sinister

attributes ascribed to the serpent

throughout a large part of North

America.

In opposition to the baneful qualities

embodied in the serpent

are others, beneficent in character,

belonging to certain beings

who are constantly working for the

advancement and welfare of

the people. Among the Algonquians,

Michabo, the Great Hare,

was one of these. These opposing forces

of good and evil were

clearly recognized, and especially among

the more advanced

tribes, were deified, and these deities

represented by prominent

priests. The sinister gods and their

priestly representatives were

commonly connected in some manner with

the serpent, which was

usually, though not always, represented

with four horns. They

sometimes appeared as anthropomorphic

beings, part human and

part serpent.

Among the Iroquois in the latter part of

the sixteenth cen-

tury these evil forces were embodied in

the priest Wathatotarho

(Thadodaho, Atotarho). He was haughty,

ambitious, crafty, re-

morseless, and a dreaded sorcerer.

Tradition attributes to Watha-

totarho the following preterhuman

characteristics, doubtless de-

rived from the god which he personified.

His head was clothed

7 Mooney, op. cit., 298,

299.

8 Charles Clark Willoughby, "The

Serpent Mound of Adams County, Ohio," in

American Anthropologist (Lancaster, Pennsylvania, 1888--), new

Series, XXI (1919),

153-163.

260 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

in lieu of hair with living vipers; his

hands and feet had the

shape of huge turtle-claws; his other

organs were similarly mon-

strous in form, in keeping with his

demoniacal mind. He is said

to have had "seven crooks in his

body," referring figuratively to

his unnatural hair, hands, and feet,

eyes, throat, hearing, sexual

parts, and mind.9 It will be

remembered that seven is a number

which constantly occurs in Indian

mythology. An earlier de-

scription of Wathatotarho by the same

accomplished student of

the Iroquoian people is as follows: His

hair was "composed of

writhing hissing serpents, his hands

were like unto the claws of a

turtle, his feet like unto bear's claws

in size and were awry like

those of a tortoice, and his body was

cinctured with many folds of

his membrum virile."10 These

mythical attributes seem to identify

him with the god of death and the

underworld.

A priest, apparently with similar

functions, is also found

among the Virginia Algonquians. He

presided for a period of

three days over the deliberations

of seven priests, which resulted

in the sentence of death to Captain John

Smith. As is well known,

Smith escaped execution through the

intercession of his young

friend Pocahontas. During the above

deliberations, this priest's

body was painted black and he wore a

headdress made of "a

dozen or sixteen" stuffed skins of

serpents and several weasels'

skins, their tails all tied together and

the skins hanging about his

head, back, and shoulders, and partly

covering his face.11 Is it

not possible to recognize in this priest

the attributes belonging also

to Wathatotarho of the Iroquois?

Among the Natches and the Creeks the

recognition of both

the sinister and beneficent

forces was highly developed, separate

towns being dedicated to the two

divisions, the former known as

red or war towns, and the latter as

white or peace towns. The

war chief of the Natches was called

Tattooed Serpent, the title

being hereditary.

9 John Napoleon Brinton

Hewitt, Wathatotarho, in Bureau of American Eth-

nology Bulletin (Washington, D.

C., 1887--), XXX (1910), Part 2, 921-922.

10 John Napoleon Brinton Hewitt,

"Legend of the Founding of the Iroquois

League," in American Anthropologist,

old Series, V (1892), 186.

11 Arber, op. cit., II,

398, 399.

THE CINCINNATI TABLET 261

With the above facts in mind, attention is turned to the Cin-

cinnati Tablet, which was discovered in December, 1841, with

a skeleton in the "old mound" in the western part of the city.

Two well-made pointed bone implements, each about seven inches

in length, were found with it.

During the destruction of the mound, several other skeletons

in a good state of preservation and near its surface were disin-

terred. This gave rise to the inference that these burials were

made since the mound was completed. The skeleton accompany-

ing the tablet and bone implements, however, was near the center

and rather below the level of the original surface, and there was

no doubt at the time of the discovery that this was the interment

over which the mound was erected.12

The tablet, Fig. 2, is made of a piece of fine-grained, compact

sandstone of light brown color, and is about one-half inch in

thickness. Upon its back are four longitudinal grooves, three

of them quite deep, and a shorter, shallower groove near either

end, the whole having the appearance of a sharpening stone for

grinding implements of bone similar to the two dagger-like objects

which accompanied it.

The anthropomorphic being engraved upon the tablet un-

doubtedly represents the Ohio Mound-builders' conception of the

personification of those sinister forces whose recognition forms a

prominent part of the beliefs of our native people.

A comparison of this Ohio figure with another representa-

tion of this sinister god from Mexico is interesting and profitable.

This Aztec god probably represents Tezcatlipoca, Lord of the

North and Underworld, and is now in the National Museum at

Mexico, Fig. 1. The humanized head of this anthropomorphic

being is made up of two serpent heads facing each other and

joined together. The eyes of the grotesque face are composed of

one eye from each of the serpent heads. Beneath the eyes is the

broad mouth with four teeth protruding. The forked tongue

appears beneath the teeth. A gruesome necklace of human hands

12 Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis, "Ancient Monuments

of the Mississippi Valley," in Smithsonian Institution Contributions to Knowledge

(Washington, D. C., 1848-1890), 1, 274, 275.

|

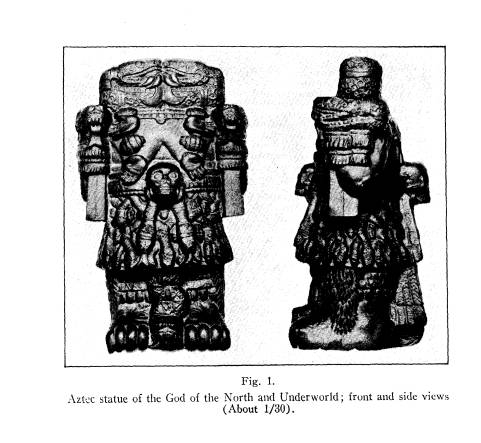

262 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY and hearts with a human skull as a pendant, overhangs the droop- ing breasts. The monstrous arms, flexed at the elbow, terminate in serpent heads. Upon the shoulder and elbow of each arm is a set of five claws, probably of the tortoise, one claw of each set at the elbows being "awry." This does not show clearly in the illus- tration, but is distinct in the statue itself. Upon the upper side of each of the great feet, and at the elbow and shoulder joints, are eyes with eyebrows clearly defined. The pair of eyes upon each foot seems to indicate that the feet also partake of the nature of heads, the four claws representing the teeth. This being is ap- parently bisexual, the male member taking the form of a serpent. This deity was associated with the color black and with the night. It is profitable to compare the description of Wathatotarho, given above, with this sinister being. |

|

|

|

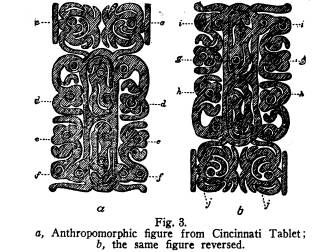

Attention is now turned to the Cincinnati Tablet as it ap- pears in Fig. 2, and in Fig. 3a. Here again is an anthropomorphic being, grotesquely human in general conception. The short, broad head has a bar-like ear upon either side, Fig. 3a, c--c. Each of the two eyes has a double curve extending downward. The broad, grinning mouth has four teeth occupying much the same position as those in the head of Fig. 1. Each arm termi- |

|

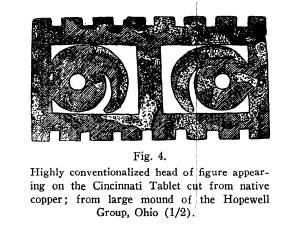

THE CINCINNATI TABLET 263 nates in a grotesque head-shaped hand, d--d, the ingenious ar- rangement of the five digits forming its outline. The feet, e--e, are like the hands reversed. These, and what seem to be the lower legs, are crooked upward at the knees, f--f. The narrow body has two oval designs, the significance of which is not clear. The hands, feet, and joints of the shoulders and legs, in addition to the various heads, are furnished with eyes, as in the Aztec sculpture. In Fig. 3b the drawing is reversed. The anthropomorphic head appears at the bottom, upside down, and in this position clearly shows the two serpent heads facing each other. Here is the typical four-horned serpent. Upon each of the heads are the four horns, two of which turn upward and two downward. The lower jaw appears in j. A further study of this curious bas-relief reveals other heads, notably at f--f, and at i--i. In the extensive deposit of native copper symbols from the Great Mound (number 25) of the Hopewell Group, Ohio, were several highly conventionalized examples of the head of this sinister god, one of which is shown one-half natural size in Fig. 4. |

|

|

|

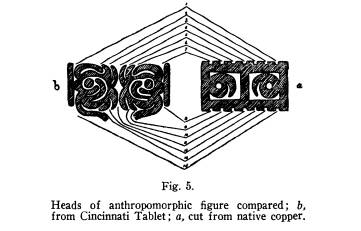

264 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY This again appears, much reduced, beside the head from the tablet in Fig. 5. |

|

|

|

It should be noted that there are seven indentations or open- ings at the top, and also at the lower portion of each. These are connected with numbered lines to make the relationship of the parts clearer. The eyes in the copper head, a, are each furnished with a single curved projection instead of with two, as in b. There are also seven diagonal lines above the head on the tablet, Fig. 2. It will be recalled that there were seven crooks in the body of Wathatotarho, and that there were seven priests, includ- ing the serpent priest who deliberated over the fate of Smith. There is undoubtedly a close connection between Watha- totarho of the Iroquois, the anthropomorphic serpent deity of the Cincinnati Tablet, and the cognate being appearing in the great Mexican statue, Fig. 1. That they are all variants of the same sinister being seems evident. There is much to be learned through a comparative study of the mythical traditions of the Indians and the various archaeo- logical remains constantly being brought to light. This phase of study has not received the attention which it deserves. |