Ohio History Journal

TERRY A. BARNHART

James McBride: Historian and

Archaeologist of the Miami Valley

James McBride of Hamilton, Ohio, was a

man of many parts. At various

junctures of his busy life, McBride's

multifarious activities embraced mer-

chandising, architecture, banking, civil

engineering, and several avenues of

public service. As respectable as those

attainments were, however, his most

enduring contributions were made as an

amateur historian and archaeologist.

McBride is a prime example of the

antiquarian chronicler, of which the nine-

teenth century provides so numerous and

significant an offering. Those dili-

gent investigators dedicated themselves

to the collection of original historical

and archaeological materials with an

enthusiasm and single-mindedness of

purpose that command respect and

admiration. As a chronicler of early set-

tlement in the Miami Valley and a

surveyor and mapper of prehistoric Indian

sites, McBride made significant

contributions to Ohio history and archaeol-

ogy. Indeed, the value of his researches

in these fields led several of his con-

temporaries and successors to lament

that he has received less recognition

than is his due.1

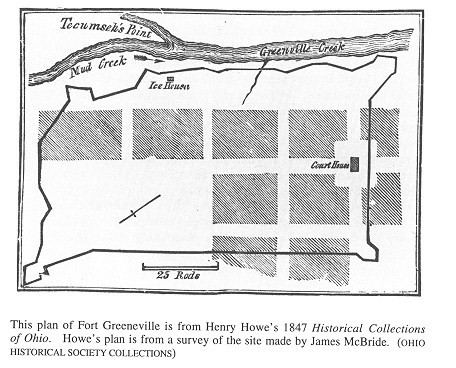

Those contributions were both numerous

and significant. Excerpts from

McBride's manuscripts relating to the

early history of the Miami Valley were

published in Henry Howe's Historical

Collections of Ohio (1847), and his ar-

chaeological surveys, field notes, and

drawings of artifacts form a conspicuous

feature of Ephraim George Squier and

Edwin Hamilton Davis's Ancient

Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (1848).

McBride's extensive

manuscript materials also resulted in

the posthumous publication of his two-

volume Pioneer Biography (1869,

1871) and his brief Notes on Hamilton

(1898). A charter member of the

Historical and Philosophical Society of

Ohio, his career closely parallels the

local history movement of the 1830s and

Terry A. Barnhart is a curator of

history with the Ohio Historical Society and an adjunct

faculty member in the history department

at Otterbein College.

1. Francis Richard Gilmore, "James

McBride" (M.A. thesis, Miami University, 1952), 85;

John Ewing Bradford, ed., "The

James McBride Manuscripts: Selections Relating to the Miami

University," Quarterly

Publication of the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, 4

(January-March, 1909), 4; A History

and Biographical Cyclopeadia of Butler County, Ohio

(Cincinnati, 1882), 170; and Laura

McBride Stembel, "James McBride" in James McBride,

Pioneer Biography: Sketches of the

Lives of Some of the Early Settlers of Butler County, Ohio, 1

(Cincinnati, 1869), ix.

24 OHIO

HISTORY

'40s. McBride's original contributions

on the early settlement of the Miami

Valley, the history of Miami University,

and his zealous activities as a sur-

veyor and mapper of prehistoric

earthworks gave full expression to the mis-

sion of that movement. Moreover, his

mass of manuscript histories of

Hamilton, Oxford, and Miami University

have been the grist for numerous

works of local history, including A

History and Biographical Cyclopeadia of

Butler County, Ohio (1882). Certainly the depth and range of McBride's in-

vestigations into the history and

archaeology of the Miami Valley are worthy

of remembrance in their own right.2

James McBride was born of Scottish

ancestry on November 2, 1788, on a

farm near Conococheaque Creek some three

miles from Greencastle,

Pennsylvania. His father, James Sr., was

a surveyor, land speculator, and

gristmill owner with landholdings in

Pennsylvania and Kentucky. James Sr.

was killed during an Indian raid at Dry

Ridge, Kentucky, in 1789 or '90.

That untoward occurrence set in motion

the train of events that ultimately

brought James Jr. to Ohio. The death of

James McBride Sr. left his year-old

son and wife, Margaret McRoberts McBride

(1771-1808), without an estate,

since James's out-of-date will passed on

his land holdings to his brothers and

sisters. Thus denied a patrimony, James

Jr. resided with his mother and ma-

ternal grandfather, James McRoberts

(1718-1805), on the family farm near

Conococheaque Creek. Had McBride come

into possession of his father's

property, his adult life may well have

been spent in Pennsylvania or

Kentucky instead of Hamilton, Ohio.3

The frugality of life on the family farm

denied McBride the opportunity of

acquiring a formal education.

Undoubtedly, this accounts for the persistent

pursuit of self-culture (a trait he

exemplified throughout his life) that enabled

him to develop his literary and

antiquarian interests into respectable attain-

ments as a scholar. Like many

self-educated and self-sufficient men of his

generation, McBride also received

practical training as a land surveyor during

his early years in Pennsylvania. That

skill would serve him well in laying

out county roads, turnpikes, and in the

mapping of prehistoric Indian mounds.

Such were the humble origins that led

McBride, in his eighteenth year, to

leave the family farm in Pennsylvania

and seek his fortune in Hamilton,

2. The significance of McBride's

contributions to local history and his own importance

within the history of Hamilton have

long-been noted. See Daniel Preston, "Market and Mill

Town: Hamilton, Ohio, 1795-1860"

(Ph.D dissertation, University of Maryland, 1987);

Gilmore, "James McBride," loc

cit; Alta Harvey Heiser, Hamilton in the Making (Oxford,

Ohio, 1941); Stephen D. Cone, Biographical

and Historical Sketches: A Narrative of Hamilton

and Its Residents from 1792 to 1896 (Hamilton, 1896); and A Concise History of Hamilton,

Ohio

(Middletown, 1901).

3. McBride, Pioneer Biography Vol.

1 (Cincinnati, 1869), 205-06; Stembel, "James

McBride," Ibid., vii-xi; A

History and Biographical Cyclopaedia of Butler County, Ohio, 169;

"Family Record," McBride Papers,

Typescript, Cincinnati Historical Society, 5; and Gilmore,

"James McBride", 1-4, 7.

|

James McBride 25 |

|

Ohio. His arrival there was part of a larger movement of emigrants from Pennsylvania who settled in the Miami Valley during the early 1800s. Those transplanted community builders made significant contributions to the early social, economic, and cultural history of southwestern Ohio.4 When McBride arrived at Hamilton in December of 1807, it was still a community in embryo-crude and rough, but ripe with opportunities for an ambitious, talented, and enterprising young man. Hamilton was still a center for the fur trade, and it was common to see Indians bartering deer skins and furs with local merchants.5 It was the seat of Butler County and its favorable location on the Great Miami River promised to make it a prosperous market town for agriculture produce. The community traced its origins to Fort Hamilton, erected in September of 1791 during the ill-starred Indian campaign of Arthur St. Clair. Several of Hamilton's first settlers were the officers, sol-

4. See W.H. Hunter, "Influence of Pennsylvania on Ohio," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications, 12 (Annual, 1903): 287-309. 5. James McBride, "History of the Town of Hamilton," MS Volume 1, McBride Papers, Cincinnati Historical Society, 135; Jacob Lewis to James McBride, September 4, 1843, McBride Papers Vol. 9, Cincinnati Historical Society; and James McBride, Notes on Hamilton (Hamilton, 1898), 26. |

26 OHIO

HISTORY

diers, and civilian contractors who

remained at the site after the Wayne cam-

paign of 1794 and the abandonment of

Fort Hamilton in June 1797.6

McBride observed that those first

residents of Hamilton lacked "energy and en-

terprise," and in many cases were

"dissipated and immoral." They were cer-

tainly "not the class of citizens

best calculated to promote the rapid improve-

ment of the place."7

McBride's first known employment in

Hamilton was as an assistant to

John Reily, the Butler County Clerk of

Courts and Postmaster. McBride's

early association with Reily was well

met. He was the clerk of the House of

Representatives in the territorial

legislature prior to Ohio statehood, a delegate

to the Ohio Constitutional Convention of

1802, and a trustee of Miami

University. The capabilities of the

youthful and hardworking McBride made

an immediate impression on Reily, thus

earning him the trust of an influen-

tial local official. It is likely that

it was Reily who also arranged for McBride

to apply his knowledge of surveying in

laying out the first county roads in

Oxford Township between 1809 and 1811,

thus beginning what would be a

long association with Oxford and Miami

University. McBride's relationship

with Reily was his entree into local

society.

But it was McBride's partnership with

Hamilton merchant Joseph Hough

(1783-1852) that firmly established him

in his adopted community. Between

1811 and 1815, McBride and Hough shipped

locally produced flour, pork, and

whiskey by flatboat to New Orleans. The

great demand for this produce made

the New Orleans trade a lucrative, if a

laborious and risky business.8

McBride's position as a community leader

in Hamilton was a direct result of

his successful mercantile partnership

with Hough and the prudent investments

that followed immediately from it. He

became the architect and proprietor of

the Hamilton House in 1812, a concern he

owned until his death, and was

elected county sheriff between 1813 and

1817. The profits from McBride's

mercantile business also enabled him to

purchase the printing press and type

used to issue the Miami

Intellegencer on June 22, 1814, the first newspaper

published in Hamilton. McBride's social

standing was further solidified on

6. McBride, Pioneer Biography 1:47.

For an account of Fort Hamilton and its importance in

the establishment of Hamilton, see David

A. Simmons, "Fort Hamilton, Ohio, 1791-1797: Its

Life and Architecture" (M.A.

thesis, Miami University, 1975).

7. McBride, Pioneer Biography 1:47.

8. For an account of McBride's

activities in the New Orleans trade, see McBride to [Mary

McRoberts], Mississippi River, April 1,

1812 in "Brief Accounts of Journeys in the Western

Country, 1809-1812," Quarterly

Publication of the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio,

5(January-March, 1910); 27-31. See also

Thomas Rentschler, ed., "A Brief Account of Mr.

Hough's Life Written by Himself in

1852," Cincinnati Historical Society Bulletin, 24(0ctober,

1966); 302-12; R. Pierce Beaver,

"Joseph Hough, an Early Miami Merchant," Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, 45(January, 1936), 37-45; A History and Biographical

Cyclopeadia of Bulter County, Ohio, 166-68. See also James McBride, "Joseph

Hough,"

Pioneer Biography, 1:311-26.

James McBride

27

September 1, 1814, when he married

Hannah Lytle, a daughter of Judge

Robert Lytle. The marriage of Hannah and

James resulted in three sons and

two daughters. Hannah remained his wife

for forty-five years until her death

of typhoid fever on September 23, 1859.

James would survive her for only

ten days.

By the conclusion of his partnership

with Hough, McBride had become a

man of substantial means and standing

within local society. Over the next

four decades, the versatile McBride

played many roles in the economic and

cultural development of Hamilton and the

Miami Valley. He was the archi-

tect of the Miami Bridge, the Butler

County Infirmary, and the Hamilton and

Rossville Female Academy. At other times

he was cashier of the Bank of

Hamilton, mayor of Hamilton, claims

commissioner for the Miami Canal,

surveyor of turnpike roads, chief clerk

of public works in Ohio, member of

the Ohio House of Representatives, and

throughout much of his life an officer

and trustee of Miami University. This

record of achievement resulted in a

collection of correspondence, journals,

and reports that are of inestimable

value to local historians. But it is his

own work as an historian that concerns

us here.

McBride began to gather the isolated

threads of local history soon after his

arrival at Hamilton. His historical

proclivities and keen powers of observa-

tion are evident even in his earliest

correspondence to friends and relatives in

Pennsylvania.9 Through his

many associations with the early settlers of the

community, he obtained reminiscences and

anecdotes relating to the military

campaigns of Harmar, St. Clair, and

Wayne, and the circumstances surround-

ing the establishment of the first

settlements of the Miami Valley. His

method was to solicit information

through written inquiries, verify them with

other sources, and submit the resulting

manuscripts to the scrutiny of his in-

formants.10 Those acquainted

with these materials have lauded McBride's

meticulous attention to detail and the

trustworthiness of his documentation.

McBride's researches epitomize the local

history movement of the 1830s

and '40s. It was then that amateur

historians began to chronicle the settle-

ment period of Ohio's history and to

preserve the documents of that history

for posterity. Their efforts came at a

time when recollections of those events

were fast fading from memory. Working

with a decided sense of urgency,

they gathered and compiled every

conceivable scrap of information about local

figures and events into well-crafted

narratives. The result of this movement

9. See, for example, his comments on the

Shakers at Union Village in James McBride to

Mary McRoberts, Hamilton, Ohio, July 14,

1811. This letter has been published as "The

Shakers of Ohio: An Early

Nineteenth-Century Account," The Cincinnati Historical Society

Bulletin, 29(Summer, 1971), 127-37.

10. McBride's correspondence provides

many examples of his methodology as a

local historian. See, for instance,

James McBride to Thomas Irwin, Hamilton, September 5,

1844, McBride Papers Vol. 9, Cincinnati

Historical Society.

28 OHIO HISTORY

was the familiar pioneer-life genre of

local history, which provided a nostalgic

look at Ohio's origins and the

Promethean accomplishments of the "venerable

pioneers." Those

"olden-times," little more than a generation removed from

the events being recalled, were lauded

as heroic days of pioneer adventure.

McBride shared much in common with these

early annalists in both his tech-

nique and approach to local history.

Like them, he tirelessly labored to col-

lect and preserve accounts of "a

comparatively recent but nevertheless fast fad-

ing past."11

McBride's historical bent naturally led

him to become a founding member

of the Historical and Philosophical

Society of Ohio in 1831. His interests

and activities mirrored the purposes of

the society, and he did as much as any

one in the state to further its objects.

The first attempt to form a state histor-

ical society was made on February 12,

1822, when the state legislature incor-

porated the first Ohio Historical

Society. That society was still-born and is

not known to have ever met as a body. On

February 11, 1831, the Ohio

General Assembly passed another act of

incorporation establishing the

Historical and Philosophical Society of

Ohio. The society's members were

drawn from all sections of the state,

including such early promoters of local

history as Benjamin Tappan, Joseph

Sullivant, Samuel P. Hildreth, Timothy

Flint, and the ever-assiduous James

McBride. Their mission was to "collect

the materials of history, a copious

store, from which some future Tacitus or

Gibbon may weave the strong and elegant

web of historic narrative."12

McBride was certainly no Tacitus nor a

Gibbon. But he was among that ad-

vance cadre of Ohio historians who began

the process of collecting research

materials and of writing the first

historical narratives.

The interpretive approach of these early

histories might well be called the

"what-the-pioneers-hath-wrought"

school of historiography. They were con-

ceived as odes to progress and were

written in the most triumphant tones of

whiggish history. The first of these

annalists was Nahum Ward, author of

the very rare Brief Sketch of the

State of Ohio (1822). Ward's work was fol-

lowed by Salmon Portland Chase's

"Preliminary Sketch of the History of

Ohio," appearing in his Statutes

of Ohio and of the Northwest Territory

(1833). Chase's sketch has been

referred to, with perhaps some hyperbole, as

"the first systematic presentation

of Ohio's history."13 Far more significant

was Caleb Atwater's History of the

State of Ohio (1838). Atwater's forays

into history and archaeology make him

the first major figure in the intellec-

tual and cultural history of Ohio.

11. W.H. Venable, Beginnings of

Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley (Cincinnati, 1891), 34n.

12. Benjamin Tappan, "Address

Delivered Before the Society, December 22, 1832,"

Journal of the Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, Part I,

Volume 1 (1838), 18.

13. W.H. Venable, "Some Early

Travelers and Annalists of the Ohio Valley," Ohio

Archaeological and Historical

Publications, I(June 1887-March 1888),

236.

|

James McBride 29 |

|

|

|

This emerging historical consciousness received further definition from Henry Howe's Historical Collections of Ohio (1847),14 Jacob Burnet's Notes on the Early Settlement of the North-Western Territory (1847), and Samuel P. Hildreth's Pioneer History (1848). This was the era of short-lived histori- cal periodicals, such as James Hall's Western Monthly Magazine (1833- 1837), John S. Williams's American Pioneer (1842-'43), Neville B. Craig's The Olden Time (1846, 1847), Charles Cist's The Cincinnati Miscellany (1845, 1846), and James Handasyd Perkins's popular Annals of the West 1847).15 Such was the intellectual tradition in which the history of James McBride was nurtured.

14. Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio (Cincinnati, 1847). This work was based on Howe's tour of the state made in 1846. More than eighteen thousand copies of the first edition were sold, making it the standard history of the day. Howe made a second tour of the state between 1886 and 1888, publishing an enlarged edition of this much consulted work. See Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio, 3 vols. (Columbus, 1889, 1891). See also Larry Nelson, "Here's Howe: Ohio's Wandering Historian," Timeline, 3(December 1986-January 1987), 42-51, and Joseph P. Smith, "Henry Howe, the Historian," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society Publications, 4(Annual 1895), 311-37. 15. James H. Perkins, Annals of the West (Cincinnati, 1847). Embracing the history of the entire Ohio Valley, the work was revised by James R. Albach and published at Pittsburgh in |

30 OHIO HISTORY

McBride's greatest contribution to this

historical genre was his two-volume

Pioneer Biography, posthumously published at Cincinnati as the fourth num-

ber of Robert Clarke's "Ohio Valley

Historical Series" in 1869 and 1871.

These volumes were based on the

memoranda, letters, and journals of early

settlers in Butler County, which are

preserved among McBride's valuable col-

lection of manuscripts. He had partially

prepared these materials for publica-

tion before his death in 1859, using

them in anonymous contributions to

Charles Cist's Western General

Advertiser and for anonymous obituaries of

early settlers submitted to local

newspapers. Especially useful are McBride's

sketches of his long-time associates

John Reily and Joseph Hough, which

have been frequently drawn upon by other

writers. Portions of McBride's

sketch of Reily, for example, were

published verbatim in Burnet's Notes on

the Early Settlement of the

North-Western Territory, but with no

attribution

of its source.16 In their

final form, these materials chronicle the lives of

twenty early settlers and refer to many

more. Each sketch is a tribute to

McBride's industry as a local historian.

McBride's Pioneer Biography is

typical of other nineteenth-century writings

which venerated the character and

fortitude of frontier settlers. His work cele-

brated their transformation of the

wilderness and provided their descendants

with an heroic past and a legitimizing

mythology about their origins.

The generation of hardy men, who first

settled the western country, who encoun-

tered the perils of Indian warfare and

wrested the beautiful country we now enjoy in

peace from the possession of the

savages, who encountered and endured all the

dangers and privations of a frontier

life, have now nearly all passed away. These

men should not be forgotten, who subdued

the dense forest and made the wilderness

to blossom as the rose; who, rifle in

hand, cleared up the broad acres, which now

yield to their descendants bountiful

harvests of golden grain, to gladden the heart

and swell the fortunes of their favored

sons. The story of their sufferings and

achievements should not be allowed to

sink into oblivion.17

This interpretation puts much distance

between McBride's Pioneer Biography

and the concerns of later historians.

But it is unfair to simply dismiss this

work as mere panegyric. It was an

earnest attempt to preserve the names and

to record the accomplishments of

ordinary people whose lives were not the

usual stuff of history. Without

question, he preserved much information

about the settlement of the Miami Valley

that otherwise would have been

lost.

1857.

16. Jacob Burnet, Notes on the Early

Settlement of the North-Western Territory (Cincinnati,

1847), Ch. 26, "Mr. John

Reily," 469-78; "Publishers' Notice" in McBride, Pioneer

Biography

l:i-iii, and Jacob Burnet to McBride,

Cincinnati, June 1, 1843, Appendix A, Ibid., 73-82.

Burnet's letter to McBride originally

appeared in the Cincinnati Gazette (October 28, 1843).

17. McBride, Pioneer Biography l:xiii-xiv.

James McBride 31

McBride also compiled many materials

relating to the history of Miami

University. No one took a more direct

interest in documenting the universi-

ty's origins or in fostering its

development than did McBride. Indeed, his

long association with Miami eminently

qualified him to become the institu-

tion's first historian. It was he who

surveyed the first county road through

what is now Oxford Township in 1808,

when Oxford and its would-be uni-

versity were nothing more than a stand

of blazed trees and a flowing spring of

water.18 After Miami was

incorporated in 1809, he served as secretary pro

tempore from 1810 to 1820. The

university then existed only as a corporate

entity, but secretary McBride dutifully

recorded all transactions relating to the

board of trustees and prepared annual

reports to the Ohio legislature from

1815-1818. Undoubtedly, it was McBride's

own lack of a formal education

and his persistent pursuit of

self-culture that led him to cherish his long asso-

ciation with Miami. He did much during

his tenure as secretary to ensure that

the much-maligned institution eventually

became a reality.

McBride's position as secretary made him

the logical choice to lead the

fight against removing the seat of the

university from Oxford Township to

Cincinnati. He assured the inhabitants

of the college lands in 1814 that the

university had been irrevocably planted

"on the banks of the Four Mile,"

where it would remain "till time

shall be no longer."19 McBride's eloquent

resolve ultimately carried the day. As a

member of the Ohio House of

Representatives in 1822-23, he mustered

enough votes to defeat the bill that

would have removed Miami from Oxford

Township. With agitation over the

site of Miami at an end, the first

classes were commenced on November 2,

1824. As a trustee, McBride's

stewardship of the infant institution continued

as it increased in respectability and

size. He was directly involved in planning

and supervising the construction of new

buildings in the 1820s and '30s,

worked on various other committees

between 1821 and 1852, and further

served as president of the board from

1852 to 1859. Significantly, those

many years of service resulted in an

extensive collection of correspondence,

documents, and manuscripts relating to

the history of Oxford and Miami

University.20

18. McBride's work in laying out the

first county road in Oxford Township was recalled in

James McBride to Unknown Party,

Hamilton, December 7, 1857, McBride Papers Vol. 15,

Cincinnati Historical Society.

19. Cited in Walter Havighurst, The

Miami Years, 1809-1969 (New York, 1969), 21. See

also James McBride, "A Speech for

the General Assembly of the State of Ohio, on the Bill to

Remove the Site of the Miami University

from Oxford," Quarterly Publication of the Historical

and Philosophical Society of Ohio, 4(April-June, 1909), 45-79, and McBride to John Reily,

Columbus, January 6, 1823, James McBride

Manuscripts, Covington Collection, Miami

University Library.

20. Bradford, ed., "The James

McBride Manuscripts: Selections Relating to the Miami

Unviersity," Quarterly

Publication of the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio,

4(January-March, 1909), 4; Ibid.,

(April-June), 41-44; "Publishers' Notice" to McBride,

32 OHIO

HISTORY

Apart from McBride's impassioned

interest in history and biography, he

also made lasting contributions to

archaeology. No subject was of more in-

terest to him than the prehistoric

Indian mounds and earthworks of the Miami

Valley, yet no aspect of his many-sided

life has received less attention from

historians. McBride expended much time,

money, and effort in surveying

these works and in collecting a valuable

cabinet of associated artifacts. These

remains had been the subject of

admiration and speculation since the begin-

ning of Euro-American settlement in the

Ohio Valley, but their origin and

purposes remained shrouded in obscurity.

One of the leading objectives of the

Historical and Philosophical Society of

Ohio, consequently, was to collect all

that was known about "the labors of

a race now extinct." It sought to pro-

mote a more systematic approach to the

subject by encouraging those who

lived near these remains to make

accurate diagrams and full descriptions of

them on its behalf.21 Only

then could a more connected view of the subject

be obtained. Few members of the society

were more favorably situated to

achieve this end than McBride.

The Miami Valley presented him with a

rich field for archaeological inves-

tigations. Archaeologists have recorded

the sites of at least 221 mounds in

Butler County alone, besides 30 other

earthworks and aboriginal sites of vari-

ous descriptions.22 Only Ross

County in the Scioto Valley has a greater

number of mounds and earthen enclosures.

The Great Miami meanders widely

through Butler County from the northeast

to the southwest, dividing the

county into two unequal sections. Most

of the county lies west of the river,

which is drained by the numerous creeks

that run in a southeasterly direction

to the Miami. It is here, on the

alluvial river terraces or "bottom" lands, that

the mounds and enclosures of Butler

County are most numerous. The largest

of these works occur at the broadest

extent of these bottoms, often at the con-

fluence of streams. The soil at these

junctions is among the most fertile and

easily cultivated in the Miami Valley.

McBride knew these sites well and

fully understood how precarious were the

chances of their continued survival.

Pioneer Biography, Vol. 1, iii; Laws Establishing the Miami Univeristy

and the Ordinances of

the President and Trustees (Hamilton, 1814); James McBride, ed., Laws Relating

to the Miami

University, Together with the

Ordinances of the President and Trustees (Cincinnati, 1833);

James McBride, "A Sketch of the

Topography, Statistics, and History of Oxford, and the Miami

University," Journal of the

Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Part I, Volume I

(1838), 85-103; and "The Miami

University and the Miami College Lands," MS, n.d., McBride

Papers, Cincinnati Historical Society,

53-54.

21. Benjamin Tappan, "Address

Delivered Before the Society, December 22, 1832,"

Journal of the Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, Part I,

Volume 1 (1838), 19-20.

22. William C. Mills, Archaeological

Atlas of Ohio (Columnus, 1914), 9. John Patterson

MacLean placed the number at 250 mounds

and seventeen enclosures. J. P. MacLean,

"Aboriginal History of Butler

County," Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications, 1

(June 1887-March 1888), 64. When MacLean

revisited these sites in the 1870s and '80s, he

found that continual cultivation had

further damaged the walls of some of the enclosures and

that some embankments were altogether

leveled. MacLean, Ibid., 65.

James McBride

33

When McBride first arrived at Hamilton

in 1807, most of the mounds and

earthworks of the Miami Valley were yet

undisturbed. They were covered

with mature trees of the same size,

species, and age as those found in the sur-

rounding woodlands. Moreover, on the

very summits of these works were the

remains of large trees which had already

fallen and decayed, suggesting an

even remoter antiquity. But when McBride

began to survey these works in the

1830s, the land on which many them were

located had been cleared and

brought under cultivation. The effect of

plowing along the sides of these em-

bankments greatly reduced their original

dimensions. There was also abun-

dant evidence that several of the mounds

had been recently excavated by local

inhabitants. McBride lamented that a

more conscious effort was not being

made to preserve these remains precisely

as they had been found. The demoli-

tion of a small mound within the

University Square at Oxford, for example,

elicited a typical response.

It is to be regretted that this was

done; it [the mound] ought to have been preserved

entire, with the natural forest-trees

which grew on it, as a shady grove, in which

the students might retire to study, or

ruminate on the existence of that race by

whom these ancient works were

constructed.23

McBride bears the distinction of being

the first investigator to undertake the

systematic surveying and mapping of the

prehistoric remains of the Miami

Valley while many of them still existed.

His accomplishments in this regard

are truly remarkable.

McBride made his first known

archaeological survey in 1828. Although he

occasionally excavated mounds, it is

surveying that constitutes his greatest

contribution to archaeology. His early

surveys were published in the first

volume of the Journal of the Ohio

Historical and Philosophical Society in

1838. McBride resumed this fieldwork in

1836, with the assistance of John

W. Erwin. Erwin was recognized as the

most experienced surveyor in Ohio.

He was an assistant engineer on the

National Road at Richmond, Indiana, be-

tween 1825 and 1835, laid out numerous

turnpike roads in Ohio during the

1830s, and became an engineer on the

Miami Canal in 1842. Erwin shared

McBride's interest in preserving

accurate information about the mounds and

earthworks which were everywhere being

threatened with destruction: "the

only memorial[s] of a former people, now

only known by those remains of

their skill and industry."24 The

McBride and McBride-Erwin surveys made be-

23. James McBride, "A Sketch of the

Topography, Statistics, and History of Oxford, and the

Miami University," Journal of

the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Part I, Volume

I(1838), 89.

24. McBride to Charles Whittlesey,

Hamilton, December 9, 1840, McBride Papers,

Cincinnati Historical Society.

34 OHIO

HISTORY

tween 1836 and 1847 are among the most

accurate archaeological surveys

made in the nineteenth century.25

With compass, chain, and level, McBride

and Erwin recorded the dimen-

sions of local works and noted their

relationship to the topography of the sur-

rounding countryside. McBride had

completed about twenty-five survey maps

based on this fieldwork by 1845. He then

thought it would take at least two

or three more years to complete the

survey of all known works in the Miami

Valley. His intention was to compile

this data into an archaeological map of

the Miami Valley, and present it to a

learned society for publication. His

first preference was the Ohio Historical

and Philosophical Society, of which

he was a charter member and through

which he had already published some of

his surveys.26 McBride

meticulously recorded these surveys into bound note-

books, which were greatly sought after

by those who wished to make copies

of their contents. The originality and

value of these materials firmly estab-

lished McBride's reputation as an

archaeological investigator, earning him

election as a corresponding member of

the American Ethnological Society in

1846.27

Besides making surveys, McBride

collected an outstanding cabinet of ar-

chaeological and ethnological artifacts.

Most of the collection was given him

by friends and acquaintances who knew

his taste for collecting. Very few ar-

chaeological materials were obtained by

mound excavations. Some were re-

covered from sites destroyed during the

construction of the Miami Canal,

while others were found on the surface

during McBride's surveys or given to

him by local farmers. The collection

also included a small number of historic

calumets, trade goods, and ethnological

specimens acquired from Indian

groups residing west of the Mississippi.

When McBride obtained a contract

in 1826 to supply provisions to the army

at Cantonment Gibson in the

Arkansas Territory, he made arrangements

with local merchants to obtain sev-

25. McBride's field work has rightly

earned him recognition as a pioneer archaeologist. See

Thomas Gilbert Tax, "The

Development of American Archaeology, 1800-1879" (Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Chicago,

1973), 100, 104, and 108. The accuracy of at least one of

his surveys has, however, been

criticized. See R.W. McFarland, "Ancient Work Near Oxford,

Ohio," Ohio Archaeological and

Historical Publications, 1(June 1887-March 1888), 261-67.

26. James McBride, "Survey and

Description of Ancient Fortifications Situated in Butler

County, Ohio," Journal of the

Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, Part 1, Volume

1(1838), 104-11. McBride's bound volumes

of surveys, field notes, and watercolor drawings

of his archaeological and ethnological

collections are on permanent loan to the Ohio Historical

Society from the Academy of Natural

Sciences of Philadelphia. See James McBride Papers,

circa 1828 to 1858, MS 24, Archives-Library Division, Ohio

Historical Society.

27. John R. Bartlett to McBride, New

York, July 5, 1846 and McBride to Bartlett, Columbus,

July 16, 1846, McBride Papers,

Cincinnati Historical Society. Further evidence of McBride's

reputation as an archaeologist is found

in [Wills De] Hass to McBride, Wellsburg, Va.,

September 12, 1845; McBride to De Hass,

Columbus, October 18, 1845; De Hass to McBride,

Wellsburg, October 25, 1845, Ibid.

James McBride 35

eral items from the Osage and Cherokee

Indians who traded there.28 McBride

made watercolor drawings, pencil

sketches, and descriptions of the contents of

his collection. The drawings were

usually made to the size and color of the

originals, and their place of origin,

when known, faithfully recorded.29

But the publication of McBride's

archaeological materials, like much of his

historical research, was a task left to

others. His surveys, field notes, and

drawings came to the attention of

Ephraim George Squier and Edwin

Hamilton Davis in 1846. Squier and Davis

were then conducting archaeolog-

ical explorations and surveys in the

Scioto Valley, and wanted to compare

their findings to those of McBride.

Typical of McBride's generosity, he gave

the investigators unrestricted access to

his materials. He lent his bound vol-

umes of surveys and drawings to Squier

in January of 1846, who presented

them before the American Ethnological

Society along with the surveys and

drawings he had made with Davis. After

receiving McBride's consent, Squier

incorporated several of his surveys and

drawings into the manuscript that he

was preparing for publication. Davis

later cautioned Squier to be sure that

McBride's name was placed on all his

surveys being prepared for publication,

understanding that he had expressed

concern over receiving due credit for his

contributions.30

Davis's concern proved well-founded. The

question of whether McBride

would receive sufficient recognition for

his original contributions did, in fact,

become a matter of contention. The

McBride controversy centered on the

publication of Squier's preliminary

account of the Squier-Davis researches,

which appeared in a pamphlet published

by the American Ethnological

Society in 1847.31 In a stinging letter

to the editors of the Cincinnati

Gazette, John W. Erwin charged Squier with appropriating the

credit due to

McBride for his years of original

research. Erwin, who had assisted McBride

in making many of his contributed

surveys, accused Squier of failing to prop-

erly credit McBride for his survey of an

earthwork located on the Great Miami

28. McBride to Irwin and Whiteman,

February 12, 1826, McBride Papers Vol. 5 and

McBride to William Thorton, Hamilton,

December 28, 1825, October 2, 1826, and August 25,

1828, McBride Papers Vol. 9, Cincinnati

Historical Society. McBride's efforts at collecting

"Indian curiosities" for his

cabinet can be traced in McBride to M.P. White, Carthage, March

2, 1827; McBride to Col. Nicks,

Cincinnati, March 5, 1827, Ibid., Vol. 5; A.P. Chouteau to

McBride, Arkansas, February 23, 1830;

Creek Agency, April 11, 1830; and McBride to A.P.

Chouteau, Hamilton, January 8, 1832,

Ibid., Vol. 6.

29. James McBride, "Drawings and

Description of Antiquities in the Cabinet of James

McBride, Hamilton, Ohio,"

Archives-Library Division, MS 24, Ohio Historical Society.

30. Davis to Squier, Chillicothe, June

14, 1846; July 3, 1846; and June 27, 1847, Ephraim

George Squier Papers, Library of

Congress; and Squier and Davis to McBride, Chillicothe,

September 10, 1846 and Davis to McBride

(same date), McBride Papers, Cincinnati Historical

Society.

31. See E.G. Squier, Observations on

the Aboriginal Monuments of the Mississippi Valley,

"Fortified Hill, Butler, County,

Ohio, J MCBRIDE 1836," Plate 2, facing page 18, and

Transactions of the American

Ethnological Society, 2(1848), Plate

2, facing page 146.

36 OHIO HISTORY

River in Butler County. "Had I not

been acquainted with this work, I should

have taken it for granted that it was

among the number of one hundred or

more which Mr. Squier had surveyed at his expense."

Although Squier had

dated the survey and placed McBride's

name upon it, Erwin complained the

credit was so small and indistinct that

it required the "aid of good glasses" to

find it.32

According to Erwin, when McBride

generously placed his bound volumes

of surveys and drawings in Squier's

hands, it was with "an express understand-

ing" that he would receive full recognition for his original

investigations.

"This would have been done by a

noble minded man without such an under-

standing, but some men have no other way

to bring themselves into notice

than upon the labor of others." As

a long-time associate of McBride, he

knew how much time and money had been

involved in collecting the materi-

als lent to Squier, and how anxious

McBride was that they someday be pub-

lished. "Those who know Mr. M. are

satisfied that he would scorn to appro-

priate to himself credit which justly belonged to another,

and that he has no

desire to acquire fame at the expense

of others, without giving due credit

therefor." Erwin hoped that the

situation would be rectified in the larger work

forthcoming from the recently-founded

Smithsonian Institution.

The charges made in Erwin's letter were

understandably troubling to George

Perkins Marsh, a regent of the

Smithsonian and a promoter of the Squier-

Davis researches. If McBride had made

his surveys independent of Squier, said

Marsh, then he had every right to expect

that his name should appear as delin-

eator as well as surveyor. McBride eased

tensions by graciously assuring

Squier that he had full confidence in

his integrity. He claimed not to have

read Erwin's letter and denied having

ever doubted that he would receive any-

thing but his full due. Although McBride

did later request that his son-in-law

call on Squier while he was in New York

in order to inspect the engravings

made from his materials, it does not

appear that McBride himself ever ex-

pressed concern in the matter until

after it became an open issue. Indeed, one

must conclude that Erwin's animus was

motivated more by his own

anonymity at Squier's hands-his name had

not appeared anywhere within the

pamphlet-than by any alleged ill-use of

his friend McBride. Squier had, in

fact, placed McBride's name on the

survey in question, albeit in a manner un-

acceptable to Erwin.33

The McBride controversy was finally put

to rest with the publication of

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi

Valley in the fall of 1848.34

32. J.W.E. to the editor, Cincinnati

Gazette (December 30, 1847), no pagination. This and

the following paragraph are based on

Erwin's letter to the editor.

33. McBride to Squier, Hamilton, January

25 and 27, 1848 and Marsh to Squier, Washington,

January 7, 1848, Squier Papers, Library

of Congress.

34. E.G. Squier, A.M., and E.H. Davis,

M.D., "Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley:

Comprising the Results of Extensive

Original Surveys and Explorations," Smithsonian

James McBride 37

Therein, Squier and Davis duly

acknowledged their debt to McBride. The au-

thors called attention to the

"minute fidelity" and primary importance of the

McBride-Erwin surveys, McBride's years

of investigations in the Miami

Valley, and the "generous

liberality" with which he gave them the unrestricted

use of his materials. His name

distinctly appears on all maps based on his

surveys. Moreover, where McBride's notes

were quoted verbatim they were

set off from the rest of the text and

clearly identified as being taken "From the

Surveys and Notes of James

McBride." Erwin's irate letter had served its pur-

pose. Yet despite such acknowledgment,

many in the Miami Valley remained

unsatisfied. McBride's daughter, Laura

McBride Stembell, still charged Squier

and Davis with having failed,

"either through negligence or design," to give

him due credit for his contributions.35

That opinion persists on the part of

many to this day.

Such were the fruits of a lifetime of

research into local history and archae-

ology. At McBride's death in 1859, he

left some 3,000 manuscript pages re-

lating to these subjects. Among them are

several unfinished manuscript his-

tories that have been repeatedly drawn

on in later works of local history. He

also collected a choice library of some

2,500 volumes of theological, legal,

scientific, literary, and historical

works, including complete files of several

national and local newspapers compiled

between 1814 and 1856.36 McBride's

private collection was later described

as the largest and rarest of its kind then

in Ohio, "probably the richest in

the incunabula of the West."37 Regrettably,

this collection was broken-up after

McBride's death. While some of his auto-

graphed books and pamphlets were sold to

individual collectors, most of his

newspapers files and rare pamphlets were

sold to a paper mill and converted to

pulp--a mindless act that Henry Howe

decried as "an irreparable loss" to his-

tory. A few of McBride's newspapers

were, fortunately, spared the paper mill

and sent to the Ohio State Library.

These files were transferred to the

Archives-Library of the Ohio Historical

Society in 1927.38

McBride's historical manuscript collections

and bound volumes of corre-

spondence met a kinder fate. They

appropriately went to the Ohio Historical

and Philosophical Society (the

Cincinnati Historical Society since 1963), an

organization he helped charter in 1831

and whose objectives he so ably em-

Contributions to Knowlege, l(Washington, D.C., 1848). There are eight McBride and

twenty

McBride-Erwin surveys present in this

volume.

35. Laura McBride Stembel in James

McBride, Pioneer Biography, ix.

36. McBride's library and cabinet were

sold at Hamilton on April 1, 1860, by John P.P. Peck,

administrator. Catalogue of the

M'Bride Library and Cabinet (Hamilton,1860). T.L. Cole,

"James McBride," Ex Libris,

l(October, 1896), 67-68.

37. The Biographical Cyclopaedia and

Portrait Gallery, 3(Cincinnati, 1884), 782.

38. Henry Howe, Historical

Collections of Ohio , l(Columbus, 1889), 356. Inventory of

Newspapers Transferred to the Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society by the State

Library Board, December 6, 1927,

Typescript, Office Files, Archives-Library Division, Ohio

Historical Society.

38 OHIO HISTORY

bodied as an amateur historian and

archaeologist. Happily, his archaeological

surveys, field notes, and artifacts also

survive. They were sold at public auc-

tion to William S. Vaux of Philadelphia

in 1859. McBride's will empowered

the executors of his estate to sell this

collection, requiring only that it be sold

as a whole and not divided. It was his

stated wish that the collection be

placed with a public institution in

Ohio, but there was no stipulation that it

was to remain in the state as was later

claimed by those who lamented its

sale.39 Vaux respected

McBride's wish that the collection not be dispersed.

He willed the bound-volumes of surveys,

field notes, drawings, and artifacts

from McBride's cabinet to the Academy of

Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

These materials have been on indefinite

loan to the Ohio Historical Society

since 1960.

In assessing McBride's contributions as

an historian and archaeologist, it

must be noted that he was neither a

great historian nor a great archaeologist.

His work possesses none of the

analytical and synthesizing attributes that are

associated with greatness in historical

and archaeological scholarship. But

judged by the intellectual and cultural

context in which he worked, McBride is

no worse for the comparison. His mission

was to gather the original materi-

als of the past, faithfully translate

them into narratives and survey maps, and

ensure that both were passed on to

posterity. He did so, moreover, in a pre-

professional era of history and

archaeology, when the only incentives for such

research were intellectual curiosity and

a personal sense and appreciation of

the past. These McBride possessed in

ample measure. What has been referred

to as his only intellectual

"aberration or eccentricity" was his belief in the

theory of concentric spheres developed

by John Cleves Symmes.40 This the-

ory held that the earth was hollow,

inhabitable within, and open at the poles.

McBride promoted this theory in an

anonymously published book.41

McBride's historical significance and

personal qualities as a scholar, how-

ever, were best appraised by Ohio's

roving historian, Henry Howe. Howe,

who first met McBride in May of 1846

during his first historical tour of the

state, made much use of McBride's

manuscripts in the original edition of his

Historical Collections of Ohio.42

Of the many fine characters Howe

had met

in his myriad travels, none made a

deeper impression on him than James

McBride of Hamilton, Ohio. As Howe

respectfully recalled of McBride,

39. Will of James McBride, May 27, 1859,

"Will Record," Volume 1, 336-41, Office of the

Probate Court, Butler County Courthouse,

Hamilton, Ohio.

40. T.L. Cole, Ex Libris, 1(October,

1896), 67.

41. [James McBride], Symmes' Theory

of Concentric Spheres (Cincinnati, 1826). For an

account of the Symmes-McBride

connection, see John Weld Peck, "Symmes' Theory," Ohio

Archaeological and Historical

Publications, 18(Annual, 1909), 28-42.

42. Henry Howe, Historical

Collections of Ohio (1847), 74, 141-42, 422-23. Henry Howe to

McBride, Springfield, November 26, 1846,

and McBride to Howe, November 30, 1846,

McBride Papers Vol. 12, Cincinnati

Historical Society.

James McBride 39

I can never forget how in my personal

interview I was impressed by the beautiful

modesty of the man, and the guileless,

trustful expression of his face as he looked

up at me from his writing . . . and then

unreservedly put in my possession the mass

of his materials, the gathered fruits of

a lifetime of loving industry. The State, I

am sure, had not a single man who had

done so much for its local history as he un-

less possibly it was Dr. S. P. Hildreth,

of Marietta, whom I well knew, and who re-

sembled him in that quiet modesty and

self-abnegation that is so winning to our

best instincts.43

McBride and Hildreth were, indeed,

similar in many ways. Both men were

archetypes of the antiquarian chronicler

who made significant contributions to

the history and archaeology of Ohio.44

Those who have succeeded them in

these fields remain conspicuously in

their debt.

Something of the essence of McBride's main

contribution to history was

once suggested by Jacob Burnet, author

of Notes on the Early Settlement of

the North-Western Territory. As Burnet observed to McBride in 1843, the

historian's role was too serve as a

counterfoil to those who received state-

ments about the past in an overly

zealous and careless manner.

Those persons, then, who labor

faithfully, and cautiously to preserve authentic

historical knowledge, entitle themselves

to the gratitude of the world. It should,

however, be born in mind, that the

office of the historian is one of immense re-

sponsibility, that it always tells for

good or for evil, and that its compiler will be

held responsible for the consequences of

a want of fidelity.45

Such is a fitting epitaph for McBride's

persevering efforts as a scribe. He

labored faithfully and cautiously to

verify the authenticity and fidelity of the

many original materials he gathered and

passed on to future generations. He

was known to contemporaries to be a man

of precise and valuable information

as a consequence of those efforts. As

fellow antiquary John Locke once ob-

served, "It is fortunate for the

history and science of the west that a few ama-

teurs like Mr. McBride have preserved

from oblivion many unique and valu-

able specimens."46 The

passage of time has not changed that verdict. This is

the legacy of James McBride, historian

and archaeologist of the Miami

Valley. His localized activities were a

significant part of a much larger

43. Henry Howe, Historical

Collections of Ohio, 1(1889), 356.

44. Samuel Prescott Hildreth, Pioneer

Biography: Being An Account of the First

Examinations of the Ohio Valley and

the Early Settlement of the Northwest Territory (Cincinnati

and New York, 1848); Biographical and

Historical Memoirs of the Early Pioneer Settlers of

Ohio (Cincinnati, 1852); and Contributions to the Early

History of the North-west, Including the

Moravian Missions in Ohio (Cincinnati, 1864). Hildreth also wrote several

historical and

archaeological pieces for the American

Pioneer (1842-1843). See Original Contributions to

the American Pioneer by Dr. Samuel

Prescott Hidlreth (Cincinnati, 1844).

45. Jacob Burnet to McBride, Cincinnati,

June 1, 1843, Appendix A of McBride's Pioneer

Biography, 1:82.

46. John Locke, "Dr. Locke's

Report" in W.W. Mather, Second Annual Report on the

Geological Survey of the State of

Ohio (Columbus, 1838), 274.

40 OHIO

HISTORY

movement,47 what David Russo

has called the great "antiquarian

enterprise."48 It was

that grassroots movement of gifted amateurs that

produced the first historical writing in

the United States, and established a yet

flourishing network of state and local

historical societies, research collections,

and journals that have made original

contributions to knowledge.49 Those

amateurs wrote histories that reflected

what ordinary people thought was

important about their past and present,

"namely the personal and close-to-

home."50 The

historiographical distance that separates us from those

historically-minded researchers should

not lessen our appreciation of their

truly remarkable accomplishments.

47. The origins of this national

movement have been traced in David D. Van Tassel's

Recording America's Past: An

Interpretation of the Development of Historical Studies in

America, 1607-1884 (Chicago, 1960), Chap. 10, "Historical Societies:

Bastions of Localism,

1815-60," 95-102, and Chapter 10,

"Documania: A National Obsession, Locally Inspired,

1815-50," 103-10.

48. David J. Russo, Keepers of Our

Past: Local Historical Writing in the United States, 1820s-

1930s (New York, 1988), xii.

49. Kathleen Neils Conzen,

"Community Studies, Urban History, and American Local

History" in Michael Kammen, ed., The

Past Before Us: Contemporary Historical Writing in the

United States (Ithaca and London, 1980), 270.

50. Russo, Keepers of Our Past, xii.