Ohio History Journal

ANTHONY GENE CAREY

The Second Party System Collapses:

The 1853

Maine Law Campaign in

Ohio

As he sat at his desk in Cincinnati in

late September, 1852,

Rutherford B. Hayes recorded his

thoughts on the apparent disintegra-

tion of a party system that had held the

loyalties of Americans for a

generation. "Government no longer

has its ancient importance," he

wrote, "Its duties and its powers

no longer reach to the happiness of

the people. The people's progress,

progress of every sort, no longer

depends on government." Even in the

midst of a Presidential cam-

paign, the people were not rallying to

the Whig and Democratic ban-

ners with customary enthusiasm. A

blurring of traditional distinctions

between the parties had left voters

confused and apathetic, and this

public malaise forced Hayes to conclude,

"Politics is no longer the

topic of this country."1

Hayes was witnessing the earliest stages

of a political realignment

that would eventually lead to the

formation of the Republican party in

Ohio and across the North. The

lackluster Presidential contest between

Franklin Pierce and Winfield Scott

convinced many Ohioans that the

major issues of the Jacksonian parties

were obsolete. A national bank,

the tariff, and federal internal

improvements, subjects of heated

controversy during the 1830s and 1840s,

seemed stale by 1852. The

most divisive national political issue

in the last six years had been

slavery, particularly the possible

extension of slavery into the western

territories acquired as a result of the

Mexican War. The question of

slavery extension had threatened to

sunder the national parties along

sectional lines and had created

divisions within both state parties in

Ohio. Large numbers of Northern Whigs

and Democrats had supported

Anthony Gene Carey is a Ph.D. candidate

in history at Emory University.

1. Entry for 24 September 1852,

Rutherford B. Hayes, Diary and Letters of

Rutherford Birchard Hayes: Nineteenth

President of the United States, ed.

Charles R.

Williams (Columbus, 1922), 1: 422.

130 OHIO HISTORY

the Wilmot Proviso, a proposal to bar

slavery from the territories by

Congressional legislation. Southerners

of both parties had condemned

the Proviso bitterly, even threatening

secession from the Union should

slavery be excluded from the Mexican

cession. Sectional strains had

weakened the Whig party especially, as

part of its Northern constitu-

ency had deserted to the Free Soilers

and as the Whig organization had

all but collapsed in several states of

the lower South. The Free Soil

party, which had formed in 1848 upon a

platform dedicated to opposing

slavery extension, was an important

force in Ohio, and the loss of

antislavery Whigs to the Free Soilers

had depleted the Whigs' state

electoral strength.

The Compromise of 1850 had temporarily

settled the territorial

question by admitting the free state of

California and erecting a

territorial government in New Mexico

without restrictions on slavery,

but it had done little to revitalize the

Jacksonian party system in Ohio

or elsewhere. After both major parties

endorsed the Compromise

during the 1852 campaign, Ohio partisans

were left without any

pressing national or state issues to

invigorate party competition. The

Ohio constitutional convention of 1851

had settled most questions of

state economic policy, and repeated

defeats had sapped the Whig

party's spirit. Scott's embarrassing

showing caused some Whig leaders

to contemplate a reorganization of

parties, and even Whig Congress-

man Lewis D. Campbell decided that his

party was "dead-dead-

dead !

"2

The loosening of old party ties and the

apparent irrelevance of past

issues opened opportunities for

reformers, and in 1853, the prohibition

issue dominated Ohio politics. Concern

over Americans' liberal con-

sumption of alcohol was hardly novel, of

course; temperance reformers

of the 1850s could trace their lineage

back into the colonial era. But the

fervent prohibitionism of the early

1850s was a new phenomenon. The

movement was particularly strong in New

England, where it was

fostered by religious and moral

opposition to strong drink, and

prohibitionism also attracted support

from native citizens dismayed by

the cultural influence of the tens of

thousands of supposedly hard-

drinking Irish and German immigrants who

had entered the country

since 1845, and from employers seeking

to cultivate abstemious habits

among their workers. For a combination

of reasons, the temperance

2. Lewis D. Campbell to Isaac Strohm, 4

November 1852, Isaac Strohm Papers,

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus;

Michael F. Holt, The Political Crisis of the 1850s

(New York, 1978), 101- 38; Stephen E.

Maizlish, The Triumph of Sectionalism: The

Transformation of Ohio Politics,

1844-1856 (Kent, Ohio, 1983), 149-86;

William E.

Gienapp, The Origins of the

Republican Party 1852-1856 (New York, 1987), 13-35.

Second Party System Collapses 131

reformers adopted as their favorite

measure the "Maine Law," a

stringent prohibition statute enacted in

Maine in 1851. The Maine Law

banned the manufacture and sale of

alcohol except for very limited

purposes, and provided for distribution

only through bonded agents.

Its provisions allowed authorities to

search for and to seize illegal

liquor, and its severe penalties made it

much harsher than previous

temperance legislation. Ohio temperance

advocates had flooded the

1852 legislature with petitions calling

for the enactment of a Maine

Law. The legislature had rebuffed their

pleas, and the anti-liquor forces

responded with plans to make the Maine

Law the test issue in the 1853

state elections. Ohio Free Soilers

joined the prohibitionists in the

Maine Law crusade, and together they

introduced a potent new issue

that finally destroyed the state's

tottering party system.3

The Ohio State Temperance Convention

assembled on January 5 in

Columbus. John A. Foote, a native New

Englander who had left the

Whig party to join the Free Soilers,

presided over the gathering that

unanimously endorsed the Maine Law, and

declared that prohibition-

ists would "be satisfied with no

measure which does not provide for

the utter extermination of the

distilleries and dram-shops of the

State."4 That evening,

the delegates heard an address by Samuel Cary,

the undisputed leader of Ohio temperance

reform. A burly man with

wild, wavy black hair, Cary had

abandoned a lucrative Cincinnati law

practice for a career as a temperance

lecturer. As a national leader of

3. For background on the temperance

movement in Ohio and elsewhere, see Ian R.

Tyrrell, Sobering Up: From Temperance

to Prohibition in Antebellum America, 1800-

1860 (Westport, Conneticut, 1979); Jed Dannenbaum, Drink

and Disorder: Temperance

Reform in Cincinnati from the

Washingtonian Revival to the WCTU (Urbana,

Illinois,

1984); W. J. Rorabaugh, The Alcoholic

Republic: An American Tradition (New York,

1979); Frank L. Byrne, Prophet of

Prohibition: Neal Dow and His Crusade (Madison,

Wisconsin, 1961); Leslie J. Stegh,

"Wet and Dry Battles in the Cradle State of

Prohibition: Robert J. Bulkey and the

Repeal of Prohibition in Ohio" (Ph. D. disserta-

tion, Kent State University, 1975),

1-30. Both Maizlish, Triumph of Sectionalism, 181-

86, and Gienapp, Origins of the

Republican Party, 56-60, have offered recent interpre-

tations of the 1853 campaign in Ohio.

Maizlish minimizes the importance of the Maine

Law question and argues that the

disintegration of the party system began as early as

1849, when sectional issues disrupted

the parties. Gienapp maintains that the

ethnocultural issues were crucial and

that 1853 was a critical year in the collapse of the

second party system. I find Gienapp's

argument more persuasive, but in this paper I

attempt to chart a middle ground between

the two positions. The Maine Law campaign

destroyed the old party system in Ohio

in 1853, but slavery-related questions were most

important in separating Whigs from Free

Soilers, and it was their differences on slavery

issues that had to be surmounted in

order to form a new organization, that is, to form the

Ohio Republican party.

4. Ashtabula Sentinel, 15 January 1853.

132 OHIO HISTORY

the Sons of Temperance, Cary had long

believed that temperance

advocates "must have a nobler,

higher, holier ambition than to reform

one generation of drunkards after

another. We must seal up the

fountain whence flows the desolating

stream of moral death."5 The

convention's crucial statement on

political action, adopted the follow-

ing morning, insisted that

prohibitionists had no "intention of framing

a political party, or interfering with

those already formed," but that

they were determined to "vote for

no man, for any legislative office,

who is not fully committed" to the

Maine Law.6 By arousing public

sentiment for prohibition, temperance

forces hoped to make the po-

litical parties bid for their support.7

The two major parties initially showed

little interest in the Maine

Law or any other issue. With the

Democrats confidently in control of

the state, factional infighting and

squabbling over patronage dominated

their January 8 meeting. The party had

split into two wings, one led by

Ohio Statesman editor Samuel Medary, the other by former United

States Senator William Allen. William

Medill, the son of Irish immi-

grants and a career officeholder, won

the gubernatorial nomination,

and the platform merely reiterated past

Democratic dogma.8 The

dispirited Whigs met on February 22 and

chose the colorless Nelson

Barrere, an old national Whig with upper

South roots and conservative

sympathies. The liquor question had

already exposed divisions in the

party ranks: the two principal party

organs, the Ohio State Journal and

the Cincinnati Gazette, had lined

up against the Maine Law, but other

papers had expressed support for

prohibition or had remained neutral.

The convention declined to express an

opinion; the platform flayed the

Democrats, praised the Constitution, and

mentioned no positive mea-

sures. The word "Whig" was

absent from the document, and the

self-styled "National Conservative

Party" entered the 1853 race

limping badly, with few hopes and even

fewer issues.9

5. Cary's address to the national

convention of the Sons of Temperance (1849),

quoted in Donald W. Beattie, "Sons of Temperance:

Pioneers in Total Abstinence and

'Constitutional' Prohibition" (Ph.

D. dissertation, Boston University, 1966), 202-03; Jed

Dannenbaum, "The Crusader: Samuel

Cary and Cincinnati Temperance," Cincinnati

Historical Society Bulletin, 33 (Summer, 1975), 138-43.

6. Ashtabula Sentinel, 15 January 1853.

7. Cincinnati Gazette, 8 January 1853; Ohio State Journal, 6, 7 January

1853; Daily

True Democrat, 7 January 1853 .

8. Cincinnati Gazette, 8, 10

January 1853; Daily Plain Dealer, 10, 11 January 1853;

Ohio Statesman, 9, 13 January 1853; Ohio State Journal, 10

January 1853; Maizlish,

Triumph of Sectionalism, 183; Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder, 110-13.

Medary's

maneuverings for an appointment in

Pierce's Cabinet preoccupied the Democrats. In the

end, their interparty feuding prevented

any Ohio Democrat from being chosen.

9. Ohio State Journal, 5, 14 January; 7, 15, 23, 24 February; 21 March 1853;

Cincinnati Gazette, 1, 2, 25 February 1853; Toledo Blade, 15, 21

January; 24, 25

|

Second Party System Collapses 133 |

|

|

|

The Free Soilers, convinced that the "old parties" and their "old issues" were obsolete, enthusiastically entered the 1853 campaign ex- pecting new accessions from both major parties.10 Their January 12 convention nominated Samuel Lewis for governor by acclamation; it was Lewis' third campaign at the head of the Free Soil party. Born in Massachusetts, Lewis was a former Methodist minister, had been active in the temperance crusade since the mid-1820s, and had been a founder of Ohio's Liberty party. He ran on a platform condemning slavery as "a sin against God and a crime against man" that would "eventually destroy any people or Government which upholds or perpetuates it." Pledging to "fight now and ever against the admission of any more slave States or slave territory," the Free Soilers also advocated full and impartial black suffrage.11 Their opposition to any further extension of slavery was the core of Free Soil ideology and the

February 1853; Sandusky Register, 5 February 1853, Benjamin Wade to Milton Sutliff, 13 February 1853, Milton Sutliff Letters, Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland. 10. Daily True Democrat, 4 January 1853. 11. Anti-Slavery Bugle, 22 January 1853. For Lewis' life, see William G. W. Lewis, Biography of Samuel Lewis: First Superintendent of Common Schools for the State of Ohio (Cincinnati, Ohio, 1857). |

134 OHIO HISTORY

cardinal principle that held together

the heterogeneous coalition of men

that comprised the party.

The Free Soilers eagerly incorporated

the Maine Law into their party

creed, but at this point they had no

idea of making it the paramount

issue in the upcoming canvass.

Prohibitionism fit comfortably among

the party's arsenal of reforms, and men

like John A. Foote and Samuel

Lewis were deeply committed to the

temperance cause. The strong-

hold of the Free Soilers was the Western

Reserve, a tract in the

northeast corner of Ohio primarily

settled by New England emigrants,

where the Maine Law would surely receive

a cordial reception. The

Free Soilers were, however, prone to factionalism

on matters other

than antislavery, because party members

retained their past "party

predilections" on economic issues

and other questions.12 The party

divided over leaders largely along lines

of previous party allegiances:

Free Soil Congressman Joshua Giddings of

Ashtabula County was the

leading old Whig in the party; and

Salmon P. Chase, who had been

elected to the United States Senate in

1849 through a bargain with the

Democrats, headed the party's other

wing. Since supporting the Maine

Law ultimately meant cooperating with

prohibitionists from the major

parties, the temperance issue created

problems for the Free Soilers and

tested the strength of their party

cohesion.13

The momentum of the Maine Law crusade

built slowly in the late

winter and early spring. The temperance

campaign was a grassroots

effort that pitted neighbor against

neighbor in dozens of communities

across Ohio. When local citizens

witnessed the evils of intemperance

or experienced frustration in battles

against the rum traffic, the Maine

Law gained new adherents. In the town of

New Lisbon in Columbiana

County, for example, residents of

different political parties cooperated

to elect mayor Fisher A. Blocksome, a

devoted Maine Law man. The

town council passed several stringent

laws to end the sale of liquor by

12. Sandusky Register, 22 January

1853.

13. Daily True Democrat, 18

January 1853; Ohio Columbian, 10 February 1853; Ohio

State Journal, 14

January 1853; Albert Gallatin Riddle, "The Rise of Anti-Slavery

Sentiment on the Western Reserve," Magazine

of Western History, 6 (June,

1887), 145;

Richard H. Sewell, Ballots for

Freedom: Antislavery Politics in the United States

1837-1860 (New York, 1976), 180-81, 206-11; Maizlish, Triumph

of Sectionalism, 121-

46. At this point, Giddings' allies

disapproved of possible fusion efforts with the major

parties, while Salmon P. Chase was

contemplating further cooperation with the

Democrats. See, for example: Ohio

Columbian, 10 February 1853; Ashtabula Sentinel,

22 January 1853; Salmon P. Chase to E.

S. Hamlin, 4 February 1853, in Edward G.

Bourne, et. al., eds., "Diary and

Letters of Salmon P. Chase," Annual Report of the

American Historical Association,

1902, 2 vols. (Washington, D.C.,

1903), 1I: 248-51. On

the careers of Giddings and Chase see:

James B. Stewart, Joshua Giddings and the

Tactics of Radical Politics (Cleveland, Ohio, 1970), and Frederick J. Blue, Salmon

P.

Chase: A Life in Politics (Kent, Ohio, 1987).

Second Party System Collapses 135

the drink, but the trade continued

illicitly, particularly in a notorious

Market Street grocery. Wives had noted

the staggering gait of their

husbands after several trips to the

market, and the women became

vigilantes when appeals to the sheriff

failed. They burst into the back

room of the grocery, startled a circle

of tipplers, and apprehended the

shopkeeper. The wives brought him into

court, where he was acquitted

despite obvious evidence of guilt. Such

incidents were common enough

to convince anti-liquor forces that

nothing short of the Maine Law

could accomplish their purposes.14

Ohioans held city and town elections in

April, and in some places

these contests offered tests of

temperance sentiment. In Akron,

attempts to enforce liquor laws prompted

attacks on the houses of the

mayor and a local judge, and the marshal

braved gunfire while arresting

rum vendors. Voters condemned vandalism

and lawlessness by choos-

ing candidates pledged to continue the

struggle against dram sellers.15

Elections in Columbus were more

tranquil, but the temperance alliance

there formed an independent

"Citizen's Ticket," and their nominee

finished a close second in the mayor's

race. John J. Janney, a

Virginia-born, antislavery Quaker who

was a member of the State

Temperance Central Committee, triumphed

in his race for School

Director.16 Unless temperance

forces were in the field, however, the

April elections generally aroused little

voter interest.

The most exciting political events of

the spring occurred in Cincin-

nati, where Archbishop John Purcell had

sponsored a petition asking

that a portion of the public money spent

on education be allotted to

parochial schools, because the regular

public schools used the King

James Bible and encouraged Catholic

children to dissent from the

Roman Church. Protestants, including

some non-Catholic Irish and

Germans, reacted with fury, and the

controversy became the sole issue

in the city election. The regular party

organizations dodged the

question, and this brought two

independent, Protestant-backed, Free

School tickets into the contest.

Although the Democrats won the

mayoral race with 40 percent of the

vote, the two Free School tickets

14. Ohio Patriot, 8 April 1853; Aurora,

6, 28 April; 11 May; 8 June 1853; Buckeye

State, 28 April; 2 June 1853. Although women could not vote

and seldom overtly

participated in politics, they played an

important part in the temperance crusade. The

Women's State Temperance Convention

strongly backed the Maine Law, and women

worked at the local level to arouse

prohibition sentiment. See Anti-Slavery Bugle, 29

January 1853; Cincinnati Gazette, 2

September 1853 ; lan R. Tyrrell, "Women and

Temperance in Antebellum America,

1830-1860," 28 Civil War History, (June, 1982),

131-44.

15. Akron Democratic Standard, 10

March: 7 April 1853.

16. Ohio Columbian, 7 April 1853.

136 OHIO HISTORY

combined 42 polled percent, and the

Whigs finished a distant third. The

school issue wrecked the old party

system in Cincinnati, and the

anti-Catholic furor created new Maine

Law supporters, as many

native-born Protestants almost

automatically associated Catholicism

with intemperance.17 The Catholic

Telegraph certainly drew no dis-

tinction between anti-Catholicism and

prohibitionism when it alleged

that "Maine Liquor Laws, State

Education Systems, Infidelity, Pan-

theism, are not isolated measures,

plans, doctrines, but parts of a great

whole, at war with God."18

As the spring elections closed, the

executive committee of the state

temperance organization met to plot

strategy for the fall campaign.

John Foote chaired the April 6 meeting

in which the committee laid

plans for a special convention in June

and initiated a fund-raising plan

to support travelling temperance

lecturers. Donations from local

temperance alliances eventually exceeded

$20,000, and the committee

at one point supervised seventeen

speakers scattered throughout the

state. Meanwhile, interest in the Maine

Law caused subscriptions to

Samuel Cary's Ohio Organ of

Temperance Reform to jump from 5,000

to 20,000 in the course of the year.19

Whig and Democratic newspapers had

avoided prominently discuss-

ing the temperance question, but growing

prohibitionist sentiment

forced a reconsideration. From late spring

through the fall election the

partisan press debated the Maine Law.

The Democrats quickly aligned

against prohibition, although reactions

among the party faithful at the

county level varied considerably. The

Whigs vacillated; party leaders

first gravitated toward an anti-Maine

Law position, and then retreated

from their opinions as prohibition

attracted support from the party

rank-and-file. Free Soilers solidly

backed the Maine Law from the

beginning, but they focused less on the

merits of the Maine Law and

more on convincing temperance voters to

abandon the old parties.

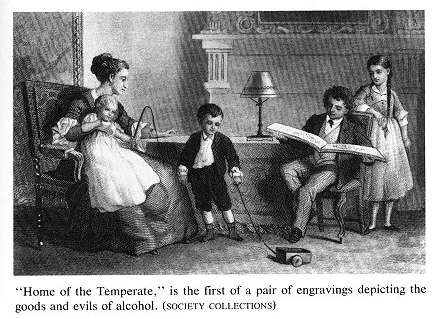

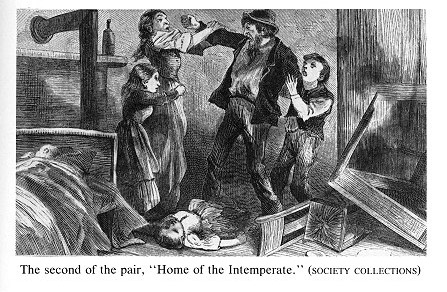

Maine Law proponents focused on the

republican theme that intem-

perance enslaved the individual and

eroded public virtue. Distilleries

and breweries spewed "forth a

constant stream of disease, and vice,

17. Cincinnati Gazette, 5

February; 16, 22 March 1853; Cincinnati Enquirer, 27

March 1853; Carl Wittke, "Ohio's

Germans, 1840-1875," Ohio Historical Quarterly, 66

(October, 1957), 339; John B. Weaver,

"Nativism and the Birth of the Republican Party

in Ohio, 1854-1860" (Ph. D.

dissertation, Ohio State University, 1982), 119; Dannenbaum,

Drink and Disorder, 117-124. About 40 percent of Cincinnati's population in

1853 was

foreign-born.

18. Catholic Telegraph, 19 March

1853.

19. Anti-Slavery Bugle, 23 April

1853; Ohio State Journal, 11 April 1853; Ohio

Columbian, 14 April 1853; Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder, 128-29.

|

Second Party System Collapses 137 |

|

|

|

and misery, and pauperism, and crime, and death."20 Liquor sellers were an "overwhelming army of leaches [sic], feeding upon the substance of the country."21 Samuel Cary predicted that "if all the liquor of this city [Cincinnati] could be annihilated at once ... we should have but little business for our police court, or use for the rookery or jail." 22 Prohibitionists believed that all previous legislation had been too lenient, unenforceable, and mistakenly aimed at restrict- ing, instead of abolishing, the sale of alcohol. Only the Maine Law could finally eradicate the liquor business and end "the long exercised right of a minority to grow fat by sucking the life-blood of the body politic."23 Like many antebellum Americans, temperance reformers dreaded conspiracies, and they often blamed the evil of intemperance on the "Rum Power." Sinister liquor interests supposedly conspired "to bring all parties to bear against" the prohibitionists and spent their

20. Newspaper clipping, 7 February 1853, James A. Briggs Scrapbooks, 2 vols., Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland: 1: 82. 21. "A Listener" in Toledo Blade, 3 September 1853. 22. Ohio Organ of Temperance Reform, 7 July 1853, quoted in Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder, 79. 23. Dudley A. Tyng in Cincinnati Gazette, 22 September 1853. |

138 OHIO HISTORY

"untold wealth" with

"lavish prodigality to defeat" reform efforts.24

Samuel Cary urged citizens to

"enroll your name, join the army of

temperance, and be prepared for a mighty

struggle with a mighty

foe."25 The fear of

plots to undermine liberty and the need for constant

vigilance in order to safeguard freedom

had been prominent themes in

American political discourse since the

Revolution, and their belief

in the "Rum Power" convinced

prohibitionists that the fate of the

Republic hinged on the battle for the

Maine Law.26

Critics of the Maine Law ridiculed the

idea of a "Rum Power" and

instead attributed intemperance to human

weakness and a bad envi-

ronment. A "brutish routine of

labor and sleep" made some working

men into inebriates, and these

unfortunates needed "places for spend-

ing the evening" that were

"free from all temptations," not the

misguided laws spawned by "the

fanaticism of reformers."27 The

moral failings of individuals were the

root of the problem; society could

remove some of the causes of

intemperance, but morality could not be

legislated. The Catholic Telegraph stressed

that the "Maine Liquor

Law, as enacted by an authority not

competent in its sphere, even

where it is passed, is never binding on

the consciences of the people.

It is a law purely penal, without any

moral sanction."28 The Demo-

cratic party had consistently opposed

the mixing of morality and

politics, and the Ohio Statesman proclaimed,

"Never has a merely

moral question been nailed to the Democratic platform."29

Democrats particularly argued that the

search and seizure provisions

of the Maine Law violated civil

liberties. The Maine Law encouraged

citizens to spy on their neighbors and

gave authorities license to invade

private property in search of illegal

liquor. The Maine Law was

fundamentally "at war with all just

notions of liberty," claimed the

Cincinnati Enquirer; and if enacted, it "would make our government

the most tyrannical one that ever

existed-Russia and Austria would

24. "Ohio," Journal of the

American Temperance Union, 17 (September, 1853),

quoted in Paul R. Meyer, "The

Transformation of American Temperance: The Popular-

ization and Radicalization of Reform

Movement, 1813-1860" (Ph.D. dissertation, Uni-

versity of Iowa, 1976), 168.

25. Ohio Organ of Temperance Reform, 25 February 1853, quoted in Dannenbaum,

Drink and Disorder, 131.

26. Jill Siegel Dodd, "The Working

Classes and the Temperance Movement in

Ante-Bellum Boston," Labor

History, 10 (Fall, 1978), 515. On the prevalence of

conspiracy theory in the United States,

see David B. Davis, The Slave Power Conspiracy

and the Paranoid Style (Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1969), and Richard Hofstadter,

The

Paranoid Style in American Politics

and Other Essays (New York, 1965).

27. Cincinnati Gazette, 16 April

1853.

28. Catholic Telegraph, 16 July

1853.

29. Ohio Statesman, 26 August

1853.

Second Party System Collapses 139

be mild and liberal in comparison."

When reformers made temperance

a "compulsory matter" and a

"political issue," the Enquirer warned

them to "expect the hostility of

everyone who is opposed to a most

odious despotism being exercised by

government."30 This civil liber-

ties argument was almost exclusively a

Democratic one, and it coin-

cided with the party's traditional

opposition to active government.

Even when Whigs opposed the Maine Law,

they acknowledged the

right to legislate for prohibition,

insisting only that the crusade would

be "injurious to the Temperance

cause" because it would drive away

less ardent supporters.31

Distinguishing between liberty and

license, Maine Law men con-

tended that a concern for social welfare

required that those "who had

not the strength to stand alone . ..

must be upheld, and restrained if

need be, by the strong arm of the

law." No one could "do wrong at his

own cost"; intemperance threatened

the lives and property of all.32

The "whole existence" of

government was "an infringement on the

natural rights of man," and

citizens relinquished "a portion of those

rights to secure peace and protection."

And reformers asked, "what

endangers our peace and safety more than

these drinking establish-

ments?"33 These

arguments had practical utilitarian overtones, but

they also appealed to transplanted New

Englanders whose Puritan

forebears had policed the morals of

their communities, and to the Whig

inclination to use positive government

to promote the general welfare.

The most prevalent argument against the

Maine Law was that it was

unenforceable. Whigs occasionally

sounded this theme, but the Dem-

ocrats were far more vocal. They thought

that it was futile "to pass acts

that public opinion will not

sustain" and that the failure of prohibition

would breed disrespect for the law in

general.34 Making liquor illegal

might assuage a few troubled

consciences, but it would not stop

drinking. With some justice, Democrats

claimed that so-called temper-

ance reformers really aimed at shutting

down taverns and groceries

frequented by immigrants and the

working-class. The Catholic Tele-

graph predicted that under

the Maine Law the rich would continue "to

buy admittance to the room in the hotels

where liquor is not sold, but

set on the table," while in poor households the "abused wife will

still

have her drunken husband, the ragged

children their tippling mother."35

30. Cincinnati Enquirer, 9 August

1853.

31. Toledo Blade, 25 April 1853.

32. Guernsey Times, 29 September

1853.

33. "Publicus" in Cincinnati

Gazette, 29 August 1853.

34. Cincinnati Enquirer, 3 August

1853 .

35. Catholic Telegraph, 24 August

1853.

140 OHIO HISTORY

Maine Law supporters had difficulty

answering questions about en-

forcement, especially because existing

township liquor laws were ob-

viously ineffectual. They simply relied

on the assertion that a vigilant

citizenry and officials would have

"little difficulty in enforcing"

prohibition.36

Economic concerns entered the Maine Law

debate, because Ohio

led the nation in the production of distilled

spirits. Unlike Maine, Ohio

was a "corn producing State,"

where "millions of dollars are invested

in distilleries." Liquor

manufacturing had "a direct influence upon the

price of corn and the price of pork, and

indirectly enters into the price

of almost everything we sell."37

Maine Law opponents even claimed

that "without whiskey, farmers, as

a matter of profit, could not afford

to produce corn at all."38 Prohibitionists

replied that feeding corn to

livestock was more profitable than

distilling it, and that farm lands

were "depreciated a full

twenty-five percent, in value, by the distill-

eries and grog shops in the

neighborhood." Maine Law sobriety would

also improve the productivity of farm

workers, reformers observed,

since the "great majority of

foreign laborers are more or less addicted

to the use of strong drinks."39

European traditions did include the

regular consumption of alcoholic

beverages, and it was among the

foreign-born that the Maine Law met

its strongest opposition. Immigrants,

mainly Germans and Irish, com-

prised more than 11 percent of Ohio's

population. Although most

ethnic groups heartily endorsed

temperance, which they defined as the

moderate use of beer and liquor, they

considered prohibition fanatical.

In Cleveland and Cincinnati, Germans and

Irish worked in the distilling

and brewing industries, and many

operated coffee houses, groceries,

and saloons that sold liquor by the

drink. These immigrant-owned

businesses were gathering places for

ethnic communities, and along

with church and home were the hubs of

social life. Religious differenc-

es separated Catholic immigrants from

the largely Protestant Maine

Law reformers, and the Catholic church

hierarchy was unremittingly

hostile to prohibition. Even Protestant

immigrants, who would join in

an anti-Catholic movement like the

Cincinnati school controversy,

were alienated by the Maine Law.

Catholics also tended to align with

the Democracy and therefore were

inclined to follow their party's

36. Cincinnati Gazette, 9 August

1853. See also Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder,

133; Sandusky Register, 25 June

1853.

37. Ohio State Journal, 7

February 1853.

38. Cincinnati Gazette, 1

September 1853.

39. Reprint from the Ohio Cultivator in

Toledo Blade, 5 October 1853. See also Tyrell,

Sobering Up, 243-44.

|

Second Party System Collapses 141 |

|

|

|

anti-Maine Law stance.40 Opposing politicians had often accused "Irish and Germans" of being "hewers of wood, and drawers of water" for Democratic party leaders, and this contempt further en- sured that the Maine Law would make little headway among foreign- born voters.41 By mid-summer, the prospect of forming Maine Law fusion tickets combining Whigs and Free Soilers had become the leading practical concern of state politicians. The gubernatorial contest attracted con- siderable attention, but the real work of the campaign had to be done at the county level, since the results of the races for the state legislature would determine the Maine Law's chances. Was Maine Law sentiment strong enough to narrow the gulf that separated Whigs and Free Soilers? Temperance reformers hoped so, but the past history of the parties made cooperation problematic. As the Ashtabula Sentinel phrased the problem, Whigs and Free Soilers "all desire to conquer their successful opponents, the Locos [i.e., Democrats]; but they have something else to conquer first-THEIR PREJUDICES AGAINST EACH OTHER."42 Joshua Giddings added that the "real obstacles"

40. Sandusky Register, 3 September 1853; Toledo Blade, 10 September 1853; Tyrrell, Sobering Up, 297-302; Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder, 124-26. 41. Daily Forest City Whig, 19 September 1853 . 42. Ashtabula Sentinel, 11 August 1853. |

142 OHIO HISTORY

to fusion were an attachment "to

party names and party pride and

party prejudices," and that

"feeling of personal hostility which has

been engendered between individuals who

have heretofore politically

opposed each other."43 In

the end, the fate of the Maine Law rested

not in the hands of non-partisan

temperance men, but in the hands of

partisan politicians.44

The Free Soilers campaigned strongly on

the Maine Law issue, but

their main goal was a more powerful

antislavery party. They thought

that it was time "to put Ohio right

on the great themes of Freedom and

Temperance, to break up thereby in the

State and in the Nation the old

organizations, and form, in their stead,

AN INDEPENDENT PARTY

OF PROGRESSION."45 Samuel

Lewis toured the state for over four

months, often joined by Joshua Giddings

and Salmon Chase, and

unless requested to speak on the

temperance question, they focused

almost exclusively on antislavery

appeals. Chase, although favoring

temperance, cared little for the Maine

Law compared to antislavery,

and his ambition for Free Soilers was

"to cast such a vote as will-if

not elect our candidate,-at least put an

end to [the] triangular

contest."46 "I am a

temperance man," Giddings had declared, "but

wholly opposed to throwing the burthen

of that reform upon the

movement for liberty."47

When Free Soilers spoke of fusion, they

normally meant the

abandonment of the Whig party and the

formation of a new antislavery

organization. If the Whig party

disbanded, the Free Soilers would have

"a clear field and a fair

fight" against the Democracy. "No intelligent

man hopes, or expects to see the Whigs

rally again as an organized

national party," they argued; let

"the Whigs withdraw their nomina-

tions" and "nine-tenths of the

Whig party will vote for liberty, justice

and humanity."48 Salmon

Chase warned Giddings not to allow "any

compromise of principles"; he

wanted no temporary arrangements and

thought Free Soilers should seek

"the union of all the Progressives

43. Letter

from Giddings in Toledo Blade, 25 August 1853.

44. Painesville Telegraph in Daily

True Democrat, 12 July 1853; Holmes County Whig

in Daily True Democrat, 2 July

1853; Daily Forest City Whig, 30 August 1853.

45. Daily True Democrat, 12 September 1853.

46. Salmon P. Chase to Charles Sumner, 3

September 1853, in Bourne, ed., "Diary

and Letters," American

Historical Association, II: 252.

47. Letter from Giddings in Ashtabula

Sentinel, 10 February 1853. See also,

Ashtabula Sentinel, 8 September 1853; Ohio Columbian, 14 April; 12

May 1853;

Hillsborough Gazette, 16 May 1853; Marietta Republican, 19 May 1853; Anti-Slavery

Bugle, 21 May 1853; Clinton Republican, 10 June 1853; Sandusky

Register, 25 June 1853;

Aurora, 7 September 1853. Reports of scores of other Free Soil

meetings can be found

in the issues of the Ohio Columbian for

1853.

48. Ashtabula Sentinel, 2 June

1853.

Second Party System Collapses 143

against all the Hunkers, rather than an

alliance with the Whigs."49 In

their quest to form a Northern

antislavery party strong enough to force

a showdown on the question of slavery

extension, the Free Soilers

repudiated the formula of intersectional

party coalitions that was the

basis of the Jacksonian party system.

The Free Soilers wanted no union with

men who were not thorough-

ly antislavery. A correspondent of the Ohio

Columbian clearly stated

the relative importance of

prohibitionism and anti-slavery in party

calculations:

We want the Maine Law; but we will not

support the Baltimore platform [that

endorsed the Compromise of 1850] even to

secure that law, and let the blame

fall where it is due. Our great cause has more than once been well nigh

ruined,

because our party has joined with one or

[the] other of [the] hunker parties for

a particular crisis. Let us be done with

it.50

The Free Soilers had never accepted the

Compromise of 1850 or the

new Fugitive Slave Law included in it,

so in fusion negotiations the

Free Soilers often demanded that Whigs

repudiate their past views on

the slavery question. The Ashtabula

Sentinel set down the basic

requirements for fusion in its county,

and the list amounted to terms for

Whig surrender. If they desired

cooperation, Ashtabula Whigs would

have to oppose the Fugitive Slave Law,

call for the separation of the

federal government from slavery, pledge

themselves to prevent the

admission of any slave states or slave

territory, and support the Maine

Law.51 The Free Soilers were

eager to unite with all men who put the

Maine Law "cause above party,"

but only if they could do so "without

sacrificing one Anti-Slavery

principle."52

The Western Reserve was of paramount

interest to the party, and

there was no conflict between the Maine

Law and anti-slavery in that

Free Soil bastion. Free Soilers could

espouse the Maine Law and

dictate antislavery platforms to the

Whigs without worrying about

alienating past party supporters.

Outside of the Western Reserve,

where the party was weak, Free Soilers

were not so doctrinaire. They

recognized that "various views will

be entertained, if not various

action demanded, according to the

circumstances in different locali-

49. Salmon P. Chase to Joshua Giddings,

1 June 1853, Salmon P. Chase Papers,

Historical Society of Pennsylvania,

Philadelphia.

50. "G" in Ohio Columbian, 4

August 1853.

51. Ashtabula Sentinel, 11 August

1853.

52. Daily True Democrat, 12

September 1853.

144 OHIO HISTORY

ties." The "same course"

was "neither necessary or expedient" for

Free Soilers "in every

county." The Free Soilers showed that they

were men of principle and astute

politicians by driving hard bargains on

the Western Reserve while assuming a

pragmatic stance in the rest of

the state.53

The Whigs had no such strategy and they

mounted almost no

campaign. Congressmen Lewis Campbell

complained that Barrere had

never ventured "out of the

corporate limits" of his home town, and

other speakers were equally inactive.54

The Whig press dropped its

earlier principled objections to the

Maine Law and belatedly endorsed

prohibition, but the party had already

forfeited any claim to temper-

ance leadership. Lewis Campbell revealed

the political motivation

behind this change when he confessed

that he was "not exactly a

Maine Law man," but added the

prayer: "Heaven send us anything

that will help, break down

Locofocoism."55 The desperation of Whig

leaders was justified, for their party

had virtually ceased to exist as a

statewide organization. It had

degenerated into a heterogeneous coa-

lition of men whose opinions on the

Maine Law ranged from total

opposition to rabid support-the only

thing they claimed in common

was the Whig name. Some men at both

extremes abandoned the party

because of its noncommittal stance, and

those in the middle became

hopelessly apathetic, as evidenced by a Whig

who considered the

Maine Law "one of the most

contemptible humbugs of the age" but

remained "entirely

indifferent" to "its passage."56 The inertia of party

loyalty was no longer enough to sustain

the Whigs, and perplexed

editors noted that never before had

"party bonds and shackles set so

loosely upon men of all parties as

they do at this present moment."57

The step out of an old party was a long

one, but the step into a new

one was even longer. Disaffected Whigs

were hardly eager to join the

Free Soilers. Benjamin Wade, who had

gained a seat in the United

States Senate in 1851 with aid from Free

Soilers, admitted that the

"Whig cause" looked

"rather blue," but was satisfied that "the same

apathy reigns in the ranks" of the

Democrats. "I care as little for

names as any one," he declared,

"but I am not to be driven from the

53. Ohio Columbian, 4 August

1853.

54. Lewis D. Campbell to Isaac Strohm,

28 June 1853, Strohm Papers, Ohio

Historical Society.

55. Lewis D. Campbell to Benjamin Wade,

16 August 1853, quoted in Maizlish,

Triumph of Sectionalism, 183.

56. Alexander Boys to [?], 3 October

1853, Alexander Boys Papers, Ohio Historical

Society, Columbus.

57. Ohio State Journal, 5 August

1853. See also Ohio State Journal, 1 July 1853;

Cincinnati Gazette, 6 August; 30 September 1853; Toledo Blade, 1

September 1853.

Second Party System Collapses 145

support of Whig principles, or from

acting with the glorious old party,

sink or swim."58 Conservative

Whigs loathed the Free Soilers on

principle as "agitators and

one-idea fanatics" obsessed with opposing

slavery.59 One such Whig was

Elisha Whittlesey, a distinguished

lawyer from the Western Reserve who had

served several terms in

Congress during the 1830s. He deplored

the breed of "fanatical

Yankee" politicians who hoped

"by taunts, hypocritical phylanthropy

[sic], & interfering with the

institution of slavery, to make the South to

take measures" to dissolve the

Union. Whittlesey and his kindred were

unlikely to support any measure that smacked

of Free Soil ultraism,

including the Maine Law.60

Most Whigs viewed a national party

system as essential, as one of

the strongest bonds that cemented the

Union, and they could foresee

that any party incorporating Free Soil

ideals would inevitably be a

sectional one. As early as 1849, Whig

United States Senator Thomas

Corwin had sensed the dangers stemming

from the Free Soilers'

single-minded devotion to opposing

slavery and slavery extension. "I

cannot comprehend the view of a party

that proposes just one thing &

cares for nothing else," he

confessed; "When I look at such a party, I

fear their motives or distrust their

judgement. I do not see any good but

much evil from its predominance."

Conservative Whigs who had

fought for years to maintain their

party's "nationality" would think

carefully before enlisting in an

antislavery party that had scant hope of

attracting support in any slaveholding

state.61

State Democratic leaders, with no

measures of their own to propose,

concentrated on attacking prospective

Whig and Free Soil fusionists.

Throughout the campaign, Democrats

denounced the Maine Law

movement as a "Whig ruse" to

snare credulous voters. The Cleveland

Plain Dealer alleged that "the prominent actors on the

temperance

stage, are manifestly aiming at

political preferment rather than social

reform."62 The Democrats

harked back to the "Log Cabin and Hard

58. Benjamin Wade to Lewis D. Campbell,

27 June 1853, Lewis D. Campbell Papers,

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus.

59. Ohio State Journal, 27 May

1853.

60. Elisha Whittlesey to Reverend James

Gallagher, 28 August 1853, Elisha Whittlesey

Papers, Western Reserve Historical

Society, Cleveland.

61. Thomas Corwin to Oran Follett, 31

August 1849, in Belle L. Hamlin, ed.,

"Selections from the Follett

Papers, 11," 9 Quarterly Publication of the Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio (July 1914), 96. Corwin was also worried about the Free

Soilers eroding Whig electoral strength

and depriving Whigs like him of federal and state

offices.

62. Daily Plain Dealer, 12

January 1853.

146 OHIO HISTORY

Cider" campaign of 1840 to prove

that the Whigs were utter hypocrites

on the temperance question.

"Whiggery in Ohio this fall seems to be

disposed to reverse the tactics of

1840," noted the Cincinnati Enquirer,

"... hoping that temperance will do

for it now what drunkenness did

then, giving it a triumph over the

Democracy.63

Although Democrats scarcely considered

the possibility of losing the

state in 1853, the prospect of eventual

Whig-Free Soil fusion was

worrisome. The Democrats had won the

last several elections with only

a plurality of the vote, and if their

opponents ever united, the anti-

Democratic forces could control Ohio.

Democratic politicians, there-

fore, viewed the apparent collapse of

the Whig party with ambivalent

feelings, because it threatened the

comfortable status quo of the party

system. The editor of the Enquirer admitted

that he preferred to

compete against the old Whig party

rather than a "conglomeration of

disaffected factionists, pretended

independents and neutrals, destitute

of political honesty."64 Victory

and spoils offered rewards for Demo-

cratic party leaders, but the appeals to

party loyalty which they relied

upon in 1853 did not generate mass

enthusiasm. As William Medill

remarked, virtually the sole goal of the

Democratic campaign was "to

keep up our organization, upon

which the attack is particularly made

at this time."65

The Maine Law fusion campaign varied widely

throughout the state.

The coalition efforts that occurred in

perhaps half of Ohio's counties

differed according to political

conditions and temperance sentiment in

each area. The Maine Law crusade

generally fared best in the northern

half of Ohio, where New England

influences were the strongest. The

southern part of the state was

comparatively untouched by the Maine

Law campaign, although temperance forces

made inroads in some

counties and waged an impressive

campaign in Cincinnati. Much of

southern Ohio had been settled

originally by emigrants from Virginia,

Kentucky, Tennessee, and other Southern

states, and many residents

there shared a contempt for Yankee

reform notions and a sympathy for

the national Democratic party with its

Southern ties.66 The Free Soilers

63. Cincinnati Enquirer, 24

September 1853. See also Ohio Statesman, 17 May; 27

July; 9, 26 September 1853; Hamilton

Telegraph, 16 June 1853; Stark County Democrat,

5 October 1853; Ohio Patriot, 2

September 1853.

64. Cincinnati Enquirer, 8

October 1853 .

65. William Medill to Ralph Leete, 12

July 1853, Ralph Leete Papers, Western

Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland.

See also Ralph Leete to William Medill, 20 July

1853, and, John E. Hanna to William

Medill, 10 August 1853, both in William Medill

Papers, Ohio Historical Society,

Columbus; Ohio Statesman, 27 July; 12 August 1853.

66. The Ohio State Journal, 14

October 1853, commented on this geographical

division after the election when it

noted that the "north has gone almost unanimously

Maine law. The south anti-Maine

law."

|

Second Party System Collapses 147 |

|

|

|

controlled proceedings on the Western Reserve, which was the center of fusion activity, while Whigs and Free Soilers formed uneasy partnerships in localities where Whigs predominated. The Whigs sometimes took the initiative on the Maine Law issue, then challenged Free Soilers and temperance Democrats to join them. The Democrats occasionally nominated their own Maine Law candidates, and Demo- cratic dominance in a score of counties discouraged any opposition fusion efforts. All of these varieties of fusion were unstable; fusion tickets were formed, abandoned, and then taken up again, often within a matter of days. Confusion kept politics in a state of flux, and for disillusioned Whigs the most prevalent form of "fusion" was the haphazard desertion of their old party. In the Western Reserve counties of Huron and Ashtabula, Free Soilers nominated straight tickets and urged others to support them, but elsewhere the antislavery party negotiated fusion arrangements with the Whigs.67 Anti-Democratic temperance forces in Summit County had cooperated in the Akron city elections in April, and they

67. Ashtabula Sentinel, 11 August; 8, 22 September 1853; Ashtabula Weekly Tele- graph, 17 September 1853; Ohio Columbian, 7 September 1853. |

148 OHIO HISTORY

extended their alliance with a fall

slate of Maine Law fusion candi-

dates. Lyman Hall, the editor of the

Free Soil newspaper in Portage

County, forged a tenuous Maine Law bond

between his party and local

Whigs, despite continued Whig antipathy

to the Free Soilers' anti-

slavery dogmas. This rapprochement was a

step toward healing the

split that had thrown most county

elections since 1848 to the minority

Democrats.68 Erie County Free

Soilers spurned Whig fusion offers,

proclaiming that they could not

"support one enormity to aid in the

suppression of another," and that

they would not coalesce with

"proslavery parties in order to

secure the election of a Maine Law

man." The Whig Sandusky Register

censured Erie Free Soilers for

professing "an abhorrence for

'party ties' and 'party subserviency,' "

and yet letting their own party

prejudices divide the Maine Law vote.

This charge rang true; Western Reserve

Free Soilers seldom sacrificed

antislavery principles to pursue Maine

Law fusion.69

The spirited fusion debate in Cuyahoga

County divided Free Soilers

along lines of past party allegiance. An

early September fusion meeting

in Cleveland nominated a mixed ticket of

Whigs and Free Soilers that

included John A. Foote. Such close

cooperation with the Whigs

alienated a group of Democratic Free

Soilers led by the volatile Rufus

Spaulding, and he launched a tirade

against the Whigs and fusion

before he and his allies stalked out of

the hall. Three weeks later,

Spaulding organized a convention that

made "regular" Free Soil

nominations, despite the protests of

Whig Free Soilers against

Spaulding's fratricidal course.

Meanwhile, Cuyahoga Democrats had

also split into two factions with

separate tickets, partly as a result of

personal feuds, but also because of

differing opinions on how to

balance the need for German Democratic

votes against the desire to

attract Maine Law supporters. Four

tickets, none of them bearing the

Whig name, thus competed for the favors

of Cuyahoga voters.70

Fusion efforts were yet more complicated

outside the Western

Reserve, as each group of county party

leaders maneuvered for

advantage. Free Soil strength in Morrow

County nearly equaled that of

the Whigs, and the two parties together

outnumbered the Democrats.

Morrow temperance men made independent

nominations, which were

68. Akron Democratic Standard, 25

August; 1, 22 September; 6 October 1853; Eric J.

Cardinal, "The Development of an

Anti-Slavery Political Majority: Portage County,

Ohio, 1830-1856 (M.A. thesis, Kent State

University, 1973), 80-92.

69. Sandusky Register, 3

September (quotations); 8 October 1853.

70. Daily True Democrat, 20

August; 5, 19, 26, 27 September; 7, 11 October 1853;

Daily Plain Dealer, 12, 13, 20 August; 3, 30 September 1853; Cleveland

Weekly Herald,

28 September 1853; Daily Forest City

Whig, 29 September 1853.

Second Party System Collapses 149

subsequently endorsed by the Free

Soilers, but a joint convention of

Whigs, Free Soilers, and temperance

advocates then formed a com-

promise Maine Law ticket. In Columbiana

County, New Lisbon

residents continued their temperance

battle. County Democrats re-

mained silent on the Maine Law at their

June convention, and the Free

Soilers met shortly afterwards and chose

prohibition candidates. The

Whigs responded by pushing for fusion,

and in a hastily organized

"People's" convention, they

selected Maine Law nominees of their

own. Neither Democrats nor Free Soilers

accepted this Whig-backed

ticket, and the Columbiana temperance

vote remained divided. Assess-

ing the situation, Free Soil editor

Marius Robinson aptly concluded,

"Politics are a little mixed up in

this county, this Fall."71

All sorts of political combinations and

shades of temperance senti-

ment entered into county races. In strongly

Democratic Crawford

County, temperance forces nominated a

Maine Law Democrat for state

representative. The Whig and Democratic

papers endorsed him and he

ran unopposed. Both Whigs and Democrats

in Guernsey County

formed Maine Law tickets, and this

unanimity on prohibition spawned

a reverse fusion effort when disaffected

men from both parties joined in

backing an anti-Maine Law slate. The

campaign around Toledo in

Lucas County centered on the activities

of James M. Ashley. He would

later win notoriety as an impeacher of

President Andrew Johnson, but

in 1853, he was a Democrat who was

dissatisfied with his party's

position on both slavery and temperance.

Ashley participated in a

Maine Law convention that nominated Sanford

L. Collins, an anti-

slavery Whig, for the legislature. When

local Democrats pressured

Ashley to renounce his Maine Law

sympathies, he and several friends

broke away from the party and actively

campaigned for Samuel Lewis.

Although Ashley was already discontented

with the Pierce administra-

tion, his case was an example of the

Maine Law's tendency to break

down party lines.72

71. Anti-Slavery Bugle, 9 July;

20 August (quotation) 1853; Ohio Columbian, 15

September 1853; Ohio Patriot, 1

July; 12 August 1853; Buckeye State, 11 August 1853.

72. Hillsborough Gazette, 22

August 1853; Guernsey Times, 8, 15, 29 September

1853; Toledo Blade, 1, 4 August;

24 September 1853; Robert F. Horowitz, The Great

Impeacher: A Political Biography of

James M. Ashley (New York, 1979),

15-16. The

variety of political combinations in

1853 almost defy general description. Free Soilers in

overwhelmingly Democratic counties often

stood alone and backed the Maine Law. See

Ohio Columbian, 25 August; 15 September 1853; if no fusion occurred in

a county, the

Whigs either supported the Maine Law or

lapsed into apathy. See Marietta Republican,

25 August; 10 October 1853; Clinton

Republican, 19 August 1853; and in several counties

the Democrats campaigned on the temperance

issue without endorsing the Maine Law.

See Hillsborough Gazette, 27

June; 6 September 1853; Ohio Democrat, 9 June; 21, 27

July; 11 August; 8 September 1853.

150 OHIO HISTORY

The party system in Cincinnati never

recovered from the free school

controversy, and the Cincinnati Times

believed that "there never was

such political confusion in Hamilton

County as there is at the present

time." "Old party ties have in

great measure been rent asunder," the

editor reported, "and the only

organizations that now exist, are

founded upon an entire new issue-that of

a prohibitory liquor law."73

Cincinnati prohibitionists carefully

balanced their Maine Law ticket,

selecting five Whigs, five Democrats,

and a Free Soiler. Three of the

Whigs were already on that party's

regular ticket, and the Free Soilers

subsequently ratified the Maine Law

nominations. The coalition move-

ment among their opponents unexpectedly

unified the Democrats,

most of whom supported the party

convention candidates pledged to

oppose the Maine Law.74

The final fusion effort was an impromptu

arrangement at the state

level between Whigs and Free Soilers.

The Free Soilers' candidate for

lieutenant governor, Benjamin Bissell,

announced his withdrawal in

early August. The party initially

selected a replacement, but then

changed course and adopted Isaac J.

Allen, the Whig nominee. Allen

was a political novice from heavily

Democratic Richland County who

had appealed for Free Soil support by

declaring his opposition to

slavery extension and to the Compromise

of 1850, and by firmly

endorsing the Maine Law. This

last-minute cooperation on a Maine

Law Whig with Free Soil principles was a

fitting climax to the

confusing 1853 campaign.75

The election results were a disaster for

both the Whigs and the Maine

Law reformers. Nelson Barrere polled the

lowest vote of any Whig

gubernatorial candidate in Ohio history

in an election that featured the

lowest turnout of any contest in the

1850s. Medill won easily with

147,663 votes, followed by Barrere with

85,843, and Samuel Lewis

trailed at 49,846. Barrere fell over

60,000 votes short of his party's total

in 1848-the last time the Whigs had

captured the governorship-while

Samuel Lewis improved on his 1851

showing by some 33,000 votes.

Non-voting affected all the parties, but

the most important product of

the campaign was the desertion of

thousands of Whigs to the Free

Soilers. These defections were enough to

destroy the already weak

Whig party. The Democrats elected a

large anti-Maine Law majority to

73. Cincinnati Times, 7 October

1853, quoted in Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder,

140.

74. Dannenbaum, Drink and Disorder, 141-44;

Cincinnati Gazette, 5, 15 September

1853.

75. Ohio Columbian, 18 August; 8,

28 September 1853; Cincinnati Gazette, 20

September 1853; Ashtabula Sentinel, 29

September 1853; Ohio Statesman, 26, 29

September; 5 October 1853.

Second Party System Collapses 151

the Legislature, and thus crushed the

hopes of temperance men. A few

scattered fusion victories confined

mainly to the Western Reserve,

such as the triumph of John A. Foote and

the People's ticket in

Cuyahoga County, offered Maine Law

advocates little consolation.

The Free Soilers were enthusiastic about

their gains, but fifty-thousand

votes in one state hardly approached

their goal of a powerful antislavery

party. As the Whig Cleveland Herald concluded,

the election showed

that there was only one party in Ohio

that remained as a viable

statewide organization, the Democracy.76

The primary effects of the Maine Law

agitation were destructive;

prohibitionists generated enough

enthusiasm to draw new adherents to

the Free Soil cause and to wreck the

Whig party, but they could not

overcome widespread voter apathy.

Instead of polarizing sentiment

along party lines, and perhaps

revitalizing the Whig party, the Maine

Law crusade scattered voters and left

the remnants of an old party

system with only a few indications of

how a new one might be

constructed. The liabilities of the

Maine Law as a reform issue in 1853

proved to be overwhelming, but its

liabilities as a potential future

partisan issue were even more serious.

The Maine Law alienated all but

the most zealous temperance

supporters-few could lukewarmly ad-

vocate total prohibition. A statewide party

could hardly be built upon

a measure that created more enemies than

friends, and furthermore, an

Ohio Maine Law party could have only the

remotest relation to politics

in the rest of the Union. If a party

realignment were to take place in

Ohio, it would have to be on issues

other than the Maine Law.77

A realignment began, of course, in 1854,

and the previous year's

Maine Law campaign contributed to the

success of the anti-Nebraska

fusion movement. The collapse of their

organization made Whigs less

inclined to cling to their party simply

for party's sake, and life-long

Whigs like editor Oran Follett of the Ohio

State Journal readily

admitted that "there is not much to

choose from between this or that

party or fragment of a party in the Free

States.78 After the 1853 contest,

Whigs and Free Soilers had a better

understanding of how fusion

worked, and how it could fail. They

still disagreed over how far the

anti-Nebraska coalition should go in

opposing slavery, but outrage at

76. Cleveland Herald, 26 October

1853; Ohio State Journal, 14 October 1853; Daily

Forest City Whig, 15 October 1853; Thomas W. Kremm, "The Rise of the

Republican

Party in Cleveland, 1848-1860" (Ph.

D. dissertation, Kent State University, 1974), 105-

07; Maizlish, Triumph of Sectionalism,

185, 242; Gienapp, Origins of the Republican

Party, 56-60, 494-95.

77. Gienapp, Origins of the

Republican Party, 38, distinguishes between the "party

decomposition" phase and the

realignment phase of party reorganization.

78. Ohio State Journal, 25 April

1853.

152 OHIO HISTORY

the repeal of the Missouri Compromise

overcame many of the suspi-

cions that had blocked fusion in 1853.

There were many individual links

between the 1853 and 1854 campaigns:

John A. Foote and Lafayette G.

Van Slyke, for example, served on both

the State Temperance Central

Committee and the Anti-Nebraska State

Central Committee. Also,

many of the Free Soilers who opposed

fusion in 1853, such as Rufus

Spaulding of Cleveland and Joseph Root

of Erie County, played

important roles in founding the

anti-Nebraska party.79

But the differences between the 1853 and

1854 campaigns were more

important than their similarities. A

battle against the "Slave Power"

was, for many reasons, a more potent

issue in Ohio than opposition to

the "Rum Power." Maine Law

crusaders attacked other Ohioans,

while the anti-Nebraska movement

concentrated its fire on Southern

slaveholders and on their supposed

instrument, the national Democrat-

ic party, thus uniting anti-Democratic

forces. The antislavery cause

was made more palatable for some by

dropping Ohio Free Soil ideas

such as black suffrage and relying on

appeals to Northern racism in

claiming the territories for free white

labor. The anti-Nebraska move-

ment attracted antislavery Democrats who

had been wholly unmoved

by the Maine Law, and anti-Catholic

elements in the anti-Nebraska

coalition included Protestant immigrants

who had spurned

prohibitionism. Conservative Whigs,

persuaded by recent events that

Free Soil concerns about slavery were

justified, or simply intent upon

the restoration of the Missouri

Compromise, joined in the anti-

Nebraska movement. Finally, the anti-Nebraska

agitation extended

beyond the borders of Ohio and offered

politicians potential state and

national power-power that meant offices

and patronage.

Diverse concerns motivated Ohioans who

joined the heterogeneous

anti-Nebraska party that rolled to

victory in the 1854 fall elections.

Rutherford B. Hayes captured the spirit

of the party when he pro-

claimed that "Anti-Nebraska,

Know-Nothings, and general disgust

79. Ohio State Journal, 14

February 1853; Benjamin F. Wade to Milton Sutliff, 21

April 1854, Sutliff Letters, Western

Reserve Historical Society; Cincinnati Gazette, 5

April 1854; Salmon P. Chase to N. S.

Townshend, 10 February 1854, Chase Papers,

Historical Society of Pennsylvania;

Thomas Ewing to Oran Follett, 28 April 1854, Oran

Follett to Thomas Ewing, 1 May 1854,

and, Thomas Ewing to Oran Follett, 2 May 1854,

all in Belle L. Hamlin, ed.,

"Selections from the Follett Papers, V," Quarterly

Publication of the Historical and

Philosophical Society of Ohio, 13

(April 1918), 50-55;

Cleveland Morning Leader, 6 July 1854; Joseph Smith, ed., History of the

Republican

Party in Ohio and Memoirs of its

Representative Supporters, 2 vols.

(Chicago, 1898), I:

19-25.

Second Party System Collapses 153

with the powers that be" had

conquered the Democrats, and he was

"pleased to see old organizations

blotted out." In a span of two years,

Hayes had seen the Maine Law and

anti-Nebraska fusion movements

transform the Ohio party system. A

difficult course lay ahead, but as

the Ohio Republican party took shape

over the next two years, a

bedrock commitment to opposing slavery

extension and the "Slave

Power" held the coalition together.80

80. Rutherford B. Hayes to Uncle S.

Birchard, 13 October 1854, in Hayes, Diary and

Letters, I: 470 (quotation); Cincinnati Gazette, 16, 25

March 1854; Cleveland Morning

Leader, 7 April 1854; Daily Forest City Democrat, 23

February 1854; Salmon P. Chase

to E. L. Pierce, 12 March 1854, in

Bourne, ed., "Diary and Letters," American

Historical Association, II: 258- 60; Larry Gara, "Slavery and the Slave

Power: A Crucial

Distinction," Civil War History,

15 (March 1969), 5-18; Gienapp, Origins of the

Republican Party, 113-19; Maizlish, Triumph of Sectionalism, 187-206.