Ohio History Journal

LARRY L. NELSON

Cultural Mediation, Cultural Exchange,

and the Invention of the Ohio Frontier

There was little rest for Alexander

McKee during the autumn of 1793.

Over the course of the preceding three

years, a loose confederation of Native

Americans from along the Maumee River

Valley had looked to their British

allies for assistance. In their campaign

to expel the United States from the

Ohio Country, the northwestern tribes

had already frustrated two American

expeditions into the region. In October

1790, troops commanded by Josiah

Harmar had retreated in disarray after

encountering unexpectedly stiff Indian re-

sistance at the headwaters of the

Maumee. In November of the following

year, the confederated tribes had

completely routed a second United States

army led by Arthur St. Clair. Now, the

tribes along the Maumee watched

with mounting concern as a third force,

with Anthony Wayne at its head,

poised itself to strike at the native

stronghold.1

Comprised of the Miami, Shawnee, and

Delaware tribes living along the

Maumee, together with individuals from

other bands who had fled to the area

after the commencement of hostilities,

the confederacy opposing Wayne was

as much a creation of McKee and the British

government as of the Indians

themselves. To be sure, the tribes

making up the coalition had voluntarily

come together for their mutual defense.

They pursued their own interests and

set their own agendas. But the aid that

McKee offered and the continued sup-

port that the British government

promised served as the glue which held the

alliance together.

Larry Nelson is site manager with the

Ohio Historical Society at Fort Meigs State Memorial.

1. This and the following two paragraphs

are based on the correspondence found in the

John Graves Simcoe Papers, (MG23 H11)

Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. See

also Earnest A. Cruikshank, ed., The

Correspondence of Lieutenant Governor John Graves

Simcoe, With Allied Documents

Relating to His Administration of Upper Canada, 5 vols.

(Toronto, 1923-31), passim; Wiley Sword,

President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle

fbr the Old Northwest, 1790-1795 (Norman, Okla., 1985); Reginald Horsman, "The British

Indian Department and Resistance to

General Anthony Wayne," Mississippi Valley Historical

Review, 49 (September, 1962), 269-90. For general studies, see

Robert F. Berkhofer, "Barrier

to Settlement: British Indian Policy in

the Old Northwest, 1783-1794," in David M. Ellis, ed.,

The Frontier in American Development:

Essays in Honor of Paul Wallace Gates (Ithaca

and

London, 1969), 249-76; Reginald Horsman,

"American Indian Policy in the Old Northwest,

1783-1812," William and Mary

Quarterly, 18 (January, 1961), 35-53; Robert S. Allen, His

Majesty's Indian Allies: British

Indian Policy in the Defense of Canada, 1774-1815 (Toronto

and Oxford, 1992), 57-87.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange

73

McKee (born c.1735-died 1799), a fur

trader, land speculator, and agent with

the British Indian Department, played an

active role in lower Great Lakes

Anglo-Indian affairs for nearly fifty

years. Fathered by a white trader but

raised, in part, by his Shawnee mother,

McKee was equally at home in either

culture. He had lived among, traded

with, and fought along side many of the

Ohio Country tribes. As tensions between

the western tribes and the United

States flared into open warfare during

the 1790s, he met with tribal delega-

tions at his post at the foot of the

Maumee Rapids to discuss strategy, dis-

pense gifts, and offer advice. He

attempted to persuade the reluctant northern-

lake tribes to join the league. At the

same time, he worked to isolate repre-

sentatives from the accommodationist

eastern Iroquois confederacy who felt

that it would be in their interests to

avoid armed conflict. He oversaw the

shipment of military supplies and

provisions from British officials at Detroit

to his storehouse on the Maumee and

coordinated covert British military as-

sistance to the warring tribes. He

entertained American envoys and received

emissaries from the Crown. He directed

spies, interrogated deserters, and ex-

changed prisoners. American ambition,

native apprehension, and imperial as-

piration converged at the British

outpost along the rapids. In the center stood

Alexander McKee.

McKee was a cultural mediator, a

go-between who linked the native and

European worlds. For much of the last

half of the eighteenth century he had

exploited his familial affiliation and

close economic ties to both communities

to encourage trade, foster diplomatic

relations, and to forge a military alliance

between the British government and the

tribes of the Old Northwest. A

shrewd, skilled negotiator and loyal

British partisan, McKee employed his

abilities throughout his career to

reconcile Crown and native political, mili-

tary, and economic interests.2

McKee was not alone as cultural

mediator. Throughout the frontier era

many others fulfilled similar roles.

Perhaps the best known cultural mediator

working within the Ohio Country was

McKee's British Indian Department

subordinate Simon Girty, the notorious

Tory renegade. Other mediators in-

2. McKee's life may be traced in the

Papers of Alexander and Thomas McKee, (MG19

F16), Public Archives of Canada, Ottawa,

Ontario; McKee Papers, Burton Historical

Collection, Detroit Public Library,

Detroit, Michigan; and McKee Family File, Fort Malden

National Historic Park, Amherstburg,

Ontario. For published biographies of McKee, see

Walter R. Hoberg, "Early History of

Colonel Alexander McKee," Pennsylvania Magazine of

History and Biography, 58 (January, 1934), 26-36; Walter R. Hoberg, "A

Tory in the

Northwest," Pennsylvania

Magazine of History and Biography, 59 (January, 1935), 32-41; John

H. Carter, "Alexander McKee, Our

Most Noted Tory," Northumberland County Historical

Society Proceedings, 22 (Spring, 1958), 60-75. See also Larry L. Nelson,

"Cultural Mediation

on the Great Lakes Frontier: Alexander

McKee and Anglo-American Indian Affairs, 1754-

1799" (Ph.D. diss., Bowling Green

State University, 1994); Frederick Wulff, "Colonel

Alexander McKee and British Indian

Policy, 1735-1799" (MA thesis, University of Wisconsin-

Milwaukee, 1969); Patricia Talbot Davis,

"Alexander McKee, Frontier Tory, 1776-1794" (MA

thesis, Bryn Mawr College, 1967).

74 OHIO

HISTORY

cluded Girty and McKee's Indian

department colleague Matthew Elliott;

Andrew Montour, a translator and

diplomatic envoy active in western

Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio during the

mid-eighteenth century; William

Wells, a white youth captured and raised

among the Indians who fought

against Arthur St. Clair in 1791 but who

served as a spy and translator for

Anthony Wayne at Fallen Timbers in 1794;

John Slover, another captive

who returned to white society and acted

as Colonel William Crawford's guide

during his ill-fated expedition against

the Ohio tribes in 1782 and who later

narrated Henry Breckinridge's famous

account of the American commander's

death at the hands of his Indian

captors; and Abraham Kuhn, a Pennsylvania

trader who married a Wyandot woman

living near Lower Sandusky and who

became known as "Chief Coon,"

a respected tribal statesman and advisor dur-

ing the late 1780s.3

Cultural mediators played a central role

in a complex process of cultural ex-

change that took place throughout the

Great Lakes frontier. It is axiomatic

that when two cultures meet, both are

changed by the experience. But when

two diverse peoples first come into

contact, much of the encounter is mutu-

ally incomprehensible. Differences of

language, custom, and world view con-

spire to deprive both parties of

opportunities for intelligible communication

on all but the most basic level. As a

result, cultures frequently resort to what

historian Richard White has

characterized as a process of creative and expedi-

ent misunderstandings. Individuals from

each culture attempt to direct their

efforts at communication to the

perceived beliefs and social conventions of

the other. That these initial

perceptions are often false is of little conse-

quence, for out of these

misunderstandings arise shared perceptions regarding

the meaning of the encounter. The form

and significance of a cultural en-

counter, then, are predetermined only in

small measure by the cultural impera-

3. Colin G. Calloway, "Simon Girty:

Interpreter and Intermediary," in James A. Clifton, ed.,

Being and Becoming Indian:

Biographical Studies of North American Frontiers (Chicago,

1989), 38-58; Reginald Horsman, Matthew

Elliott: British Indian Agent (Detroit, 1964); Nancy

L. Hagedorn, "'Faithful, Knowing

and Prudent': Andrew Montour as Interpreter and Cultural

Broker, 1740-1772," in Margaret

Connell Szasz, ed., Between Indian and White Worlds: The

Cultural Broker (Norman and London, 1994), 25-43; Paul A. Hutton,

"William Wells: Frontier

Scout and Indian Agent," Indiana

Magazine of History, 74 (September, 1978), 183-222; Consul

W. Butterfield, An Historical Account

of the Expedition against Sandusky under Col. William

Crawford in 1782 (Cincinnati, 1873), 126-28; Erminie Wheeler-Voegelin,

"Ethnohistorical

Report on the Wyandot, Ottawa, Chippewa,

Munsee, Delaware, Shawnee, and Potawatomi on

Royce Areas 53 and 54," in Indians

of Northern Ohio and Southeastern Michigan (New York,

1974), 174, 188-89. For other studies of

cultural mediation, see Nancy L. Hagedorn, "'A

Friend to Go Between Them': The

Interpreter as Cultural Broker During Anglo-Iroquois

Councils, 1740-79," Ethnohistory,

35 (Winter, 1988), 34-59; Yohuside Kawashima, "Forest

Diplomats, The Role of Interpreters in

Indian-White Relations on the Early Frontier,"

American Indian Quarterly, 13 (Winter, 1989), 1-14; Daniel K. Richter, "Cultural

Brokers and

Intercultural Politics: New

York-Iroquois Relations, 1664-1701," Journal of American History,

75 (June, 1988), 40-67; Clara Sue

Kidwell, "Indian Women as Cultural Mediators,"

Ethnohistory, 39 (Spring, 1992), 97-107.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange

75

tives brought to the meeting by each

party. They are also mediated to a sub-

stantial degree through the negotiated

manipulation of the encounter's specific

circumstances. As members of both

cultures interact, working relationships

are established, and through these

relationships a sense of common under-

standing emerges.4

As the encounter matures and grows more

complex, each party grows in-

creasingly reliant upon the services of

cultural mediators, individuals whose

experiences have bridged both cultures.

Always bilingual, usually related to

both societies through birth, marriage,

or adoption, and particularly adept at

transacting the affairs of each in the world

of the other, mediators become the

specialized medium through which

cultures become interconnected.

Historians Howard Lamar and Leonard

Thompson have suggested that the

frontier was a zone of cultural

inter-penetration, a region where indigenous

peoples and intruders encountered one

another and where, eventually, one or

the other imposed a cultural hegemony

over the entire area. But the frontier

was also a zone of mutual re-invention.

Europeans and natives alike volun-

tarily, indeed eagerly, adopted elements

of each other's culture. Moreover,

that adoption was always pragmatic and

highly selective. The Ohio frontier

was a new creation. Fashioned from

self-conscious choices by those engaged

in the region's myriad forms of cultural

interaction, the frontier contained

readily identifiable elements from both

Indian and white societies, but com-

bined them in ways that were new and

ingenious. Standing astride the cul-

tural divide as they guided and shaped

native and European interaction, cultural

mediators became creators as well as

creations of the Ohio frontier.5

The new world invented by the process of

cultural exchange was related to,

4. Richard White, The Middle Ground:

Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes

Region, 1650-1815 (Cambridge and New York, 1991), ix-x; Jeremy

Boissevain, Friends of

Friends: Networks, Manipulators, and

Coalitions (New York, 1974), 27;

Edward Spicer,

"Types of Contact and Process of

Change," in Edward Spicer, ed., Perspectives in American

Indian Cultural Change (Chicago, 1961), 153-67; Christopher L. Miller and

George R. Hamell,

"A New Perspective on Indian-White

Contact: Cultural Symbols and Colonial Trade," Journal

of American History, 73 (September, 1986), 326.

5. Howard Lamar and Leonard Thompson,

eds., The Frontier in History: North American

and Southern Africa Compared (New Haven, 1981), 1-13; For the frontier as a zone of

cre-

ation, see James Merrell, The Indians

New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from Contact

through the Era of Removal (Chapel Hill, 1989), and James Merrell, "'The

Customs of Our

Countrey': Indians and Colonists in

Early America," in Bernard Bailyn and Philip Morgan,

eds., Strangers within the Realm:

Cultural Margins of the First British Empire (Chapel Hill and

London, 1991), 117-56. For culturally

based studies of the Ohio frontier, see White, The

Middle Ground; Michael N. McConnell, A Country Between: The Upper

Ohio Valley and its

Peoples, 1724-1774 (Lincoln and London, 1992); Eric Alden Hinderaker,

"The Creation of the

American Frontier: Europeans and Indians

in the Ohio River Valley, 1673-1800" (Ph.D. diss.,

Harvard University, 1991). For summaries

of recent scholarship, see Gregory H. Nobles,

"Breaking into the Backcountry: New

Approaches to the Early American Frontier, 1750-

1800," William and Mary

Quarterly, 46 (October, 1989), 641-70, and Stephen Aron, "The

Significance of the Kentucky

Frontier," Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 91

(Summer, 1993), 298-323.

76 OHIO HISTORY

yet distinct from, both native and

European precedent. The Ohio Country

was socially diverse, an intricate

cultural mosaic whose members asserted and

defended a tangled web of interconnected

national, regional, local, and individ-

ual agendas. European aims within the

region were never unified and white

stratagems frequently collapsed along

opposing national, religious, or eco-

nomic lines. Indian allegiances were

equally fragmented. Sovereign tribes

and autonomous bands independently

pursued their own self-interests through

separate, often competing policies. But

inter- and intra-ethnic cooperation

also defined social reality along the

Ohio frontier as much as inter- and intra-

ethnic rivalry. Although cultural

encounters were occasionally marked by vi-

olence, more commonly the very fabric of

everyday life instigated a peaceful

process of cultural interaction. The

Great Lakes frontier became an open, as-

similative world of shifting

relationships in constant evolution. In this

world, political loyalties and cultural

values were fluid, pragmatic, and uncer-

tain. National, ethnic, even racial

affiliation could become problematic.

Social ambivalence and cultural

interdependence were the natural by-products

of the region's inter-cultural contact,

trade, marriage, and diplomacy. Within

this world, cultural mediators took on

great importance. Able to transcend

the boundaries of nation, race, and

culture, mediators employed their skills to

facilitate, and occasionally direct, the

course of native and European interac-

tion.6

All cultural mediators share several

characteristics. First, they live within a

socially complex environment where

opportunities for intercultural contact

and exchange are likely to occur.

Secondly, they occupy a position of central-

ity within that environment. Standing at

the cultural intersections permits

the broker to manipulate the terms under

which interaction takes place.

Cultural mediators also utilize first-

and second-order societal resources.

First-order resources are those directly

controlled by the mediator. They can

include commodities, such as trade goods

or furs; specific forms of empow-

erment, such as the ability to enact or

enforce trade regulations or the author-

ity to grant access to tribal lands; and

specialized skills or knowledge such as

facility in native and European

languages and expertise in the ordinary social

customs and highly conventionalized

protocols required for trade and diplo-

macy. Contacts with other individuals,

themselves often cultural brokers who

have access to first-order assets,

constitute second-order resources. First-order

assets, when combined with an extensive

network of family members, busi-

ness associates, and personal friends,

allowed a mediator to speak not only for

Indians, but as an Indian, not only for

Europeans, but as a European, not only

for tribal authorities and colonial

officials, but as one central to the decision-

6. Colin G. Calloway, "Beyond the

Vortex of Violence: Indian-White Relations in the Ohio

Country, 1783-1815," Northwest

Ohio Quarterly, 64 (Winter, 1992), 16-26. See also

"Introduction," in Bailyn and

Morgan, Strangers Within the Realm, 1-31.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange

77

making process on both sides of the

cultural line. The acquisition of first-

and second-order resources accorded

cultural mediators a position of great in-

fluence from which they could negotiate

the price of goods, demand a desired

quantity or insist upon a high standard

of quality for specific items, outlaw

certain products or trading practices,

prohibit or encourage trading activity at

specified locations or throughout entire

regions, and invite or evict individual

traders or groups of traders into or

from their territory.7

The fur trade was the great engine of

cultural transformation along the

western border. Commerce in pelts

supplied by Indians and trade goods ex-

changed by Europeans sparked the

creation of the interconnected net of per-

sonal relationships, business

partnerships, military alliances, and political ac-

cords that formed the institutional

framework within which native and white

encounters took place. Even on the Ohio

Valley frontier, literally at the very

edge of the British Empire, the fur

trade was a powerful, sophisticated instru-

ment of cultural and economic exchange.

Embodiments of the frontier's cul-

tural pluralism, mediators were at the

center of this process.8

The fur trade provided an impressive

array of goods destined for the western

nations. In June 1766 the eastern

trading firm of Baynton, Warton, and

Morgan invoiced Fort Pitt for a diverse

inventory that included claret, rum,

blankets, tobacco, gun flints, paint,

wampum, hatchets, brass kettles, bar

lead, thread, vermilion, lace, gun

powder, bullet molds, hunting saddles, tin

cups, jews harps, combs, knives, awls,

muskets, bed lacing, shears, ribbon,

pipes, looking glass, razors, silver

jewelry, needles, and articles of clothing

including ruffled shirts, plain shirts,

calico shirts, leggings, matchcoats, gar-

tering, and breechclouts. The following

year, the Indian department commis-

sary at the post reported that over

26,000 pounds sterling worth of merchan-

dise, including 6,500 gallons of rum,

had passed through the fort. He also

noted that over 13,000 gallons of rum

had been distributed by unlicensed

traders and that other sutlers had

exchanged up to 40,000 pounds sterling

worth of goods. In return, Fort Pitt had

taken in 10,587 pounds (weight) of

beaver pelts, 15,253 pounds of raccoon

skins, 178,613 pounds of "Fall

Skins," 104,016 pounds of

"Summer Skins," and smaller amounts of pelts

from otters, fishers, wolves, panthers,

elk, and bear.9

7. Boissevain, Friends of Friends, 147-69.

8. T. H. Breen, "An Empire of

Goods: The Anglicization of Colonial America, 1690-1776,"

Journal of British Studies, 25 (October, 1986), 467-99; James H. Merrell,

"'Our Bond of

Peace': Patterns of Intercultural

Exchange on the Carolina Piedmont, 1650-1750," in Peter

Wood, Gregory Waselkov, and Thomas

Hatley, eds., Powhatan's Mantel: Indians in the

Colonial Southeast (Lincoln, 1989), 198-222. For a general study, see

Carolyn Gilman, Where

Two Worlds Meet: The Great Lakes Fur

Trade (St. Paul, 1982).

9. "The Crown to Baynton, Wharton,

and Morgan For sundry goods delivered at different

Times, by order of Capt. Murray and Mr.

Alexander McKee assistant agent for Indian Affairs,

for the use of the Indians, June 12,

1766," James Sullivan, Alexander Flick, Milton W.

Hamilton, et. al., eds., The Papers

of Sir William Johnson, 14 vols. (Albany, 1921-1965), 5:

78 OHIO

HISTORY

At its most basic level the fur trade

permitted Indians simply to exchange

traditional items of native manufacture

for similar items made in Europe.

Blankets, for instance, might replace

pelts or woven mats; glass beads might

be used instead of wampum in ceremonial

belts; trade silver might substitute

for jewelry made from shell or copper;

kettles and pots of iron or brass would

serve for those earlier made of

fire-baked clay. But at a deeper, more subtle

level, the acceptance and use of trade

goods signaled a beginning of the pro-

cess of cultural change that was at the

very heart of the invented frontier.10

European travelers within the Ohio back

country often commented upon the

combination of native and European

elements that made up Indian dress.

Nicholas Cresswell, a young Englishman

who dabbled in the Ohio fur trade

just prior to the Revolution, visited

Captain White-Eyes, a Delaware head-

man, at his village on the Upper

Tuscarawas River in September, 1775. The

dress of the men at the village, noted

Cresswell,

is short, white linen or calico shirts

which come a little below their hips without

buttons at neck or wrists and in general

ruffled and a great number of small

brooches stuck in it. Silver plates

about three inches broad round the wrists of

their arms, silver wheels in their ears,

which are stretched long enough for the tip

of the ear to touch the shoulder, silver

rings in their noses, Breechclout and

Mockeysons with a matchcoat that serves

them for a bed at night . . . The women

wear the same sort of shirts as the men.

Wear their hair long, curled down the back

in silver plates, if they can afford it,

if not tied in a club with red gartering. No

rings in the nose but plenty in the

ears. Both men and women paint with

Vermilion and other colours mixed with

Bear's Oil and adorn themselves with any

tawdry thing they think pretty.11

Other observers made an explicit

connection between appearance and the

frontier's ambiguous sense of cultural

identity. In 1742 the Moravian bene-

factor and missionary Count Nicholas

Ludwig von Zinzendorf met with

Andrew Montour near Shamokin,

Pennsylvania. Zinzendorf had found

Montour, the son of a French woman and

an Oneida war chief, wearing a sky-

colored coat of fine cloth and a black

cordovan neckband decorated with silver

bugles, a red damask lapelled waistcoat,

breeches, shoes, stockings, and a hat.

The Moravian claimed that

although Montour's ears were "braided

with brass

and other wire like a handle on a

basket," and that he wore "an Indianish broad

ring of bear fat and paint" on his

face, his appearance was remarkably

246-60; "Return of the Amount of Merchandise

brought to Fort Pitt in the year 1767," Ibid., 12:

396; "Return of Peltry sent from

Fort Pitt in the Year 1767," Ibid., 397. See also Lawrence S.

Thurman, "An Account Book of

Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan at Fort Pitt, 1765-1767,"

Western Pennsylvania Historical

Magazine, 29 (September, 1946),

141-46.

10. Miller and Hamell, "A New

Perspective on Indian-White Contact," 318; James Axtell,

"The English Colonial Impact on

Indian Culture," in James Axtell, The European and the

Indian: Essays in the Ethnohistory of

Colonial America (Oxford, 1981),

253-54.

11. Lincoln MacVeagh, ed., The

Journal of Nicholas Cresswell: 1774-1777 (New York,

1924), 120-21.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange 79

European and that when addressed in

French, the interpreter responded cor-

dially in English.12

It was not just Indians who adopted

white articles of clothing. Whites

quickly sought out and acquired Indian

modes of dress which they found prac-

tical and eminently suited to the

frontier environment. In the spring of 1775

Cresswell traveled from Fort Pitt to

Harwood's (Harrod's) Landing, an iso-

lated settlement on the Kentucky River,

and then back again. His traveling

companions, whom he described as a

"motley, rascally, and ragged crew,"

consisted of "two Englishmen, two

Irishmen, one Welshman, two Dutchmen,

two Virginians, two Marylanders, one

Swede, one African Negro, and a

Mulatto." "I believe there is

but two pair of Breeches in the company," re-

marked Cresswell, "one belonging to

Mr. Tilling and the other to myself.

The rest wear breechclouts, leggings and

hunting shirts, which have never

been washed only by the rain since they

were made.13

The party's native garb was no mere

costume. Culturally, Cresswell and

the men in his party were no longer

completely European. Nor, despite their

clothing, had they become Indian.

Rather, they had selectively adopted ele-

ments from native culture and retained

others of their own to re-invent them-

selves in response to the region's

intercultural contact. The men's appearance

reflected an emerging frontier identity

in which national allegiance was blurred

and ethnic affiliation diffused.

Cresswell himself was aware of how his expe-

riences along the frontier had affected

his sense of self-identity. In August

1775 he employed an Indian woman to make

a pair of moccasins, leggings,

and other clothing that he hoped to wear

on his next trip to the Ohio

Country. His selection of native attire

was not haphazard. Rather, it was in-

formed by a finely-honed appreciation

for the frontier's evolving cultural val-

ues. Warned by another English trader

that his Indian clients would be in-

sulted by a white man coming among them

wearing a hunting shirt, he also

ordered a calico shirt "made in the

Indian fashion." When he wore his new

clothes for the first time,

"trimmed with Silver Brooches and Armplates," he

claimed that "I scarcely

know myself."14

The inventive process of reciprocal,

discretionary cultural exchange occa-

sionally led to unexpected

juxtapositions of the native and European worlds.

Margaret Handley Erskine, a captive who

lived with the Ohio Shawnee from

1779 until 1784, became fond of the wife

of a village chief, Blue Pocket, dur-

ing her time with the tribe. Erskine

remembered Blue Pocket's wife, a "half

French woman of Detroit," as a

woman who enjoyed living in great style in a

12. William C. Reichel, ed., Memorials

of the Moravian Church (Philadelphia, 1870), 1:95;

see also Hagedorn, "Faithful,

Knowing, and Prudent," 57, and Paul A. W. Wallace, Indians in

Pennsylvania (Harrisburg, 1968), 178.

13. MacVeagh, The Journal of Nicholas

Cresswell, 83-84, 87.

14. Ibid., 102-03.

80 OHIO

HISTORY

luxurious house furnished with curtained

beds and silver spoons. The Indian

party that captured a young Englishman,

Thomas Ridout, along the Ohio

River in 1787, gave their prisoner a

breakfast of chocolate and flour cakes as

they made their way back to their

villages on the Maumee River in northwest

Ohio. After reaching the Maumee, Ridout

lived with an "old Chief" named

Kakinathucca, his wife Metsigemewa, and

a negro slave. On Ridout's first

day with his new family, Metsigemewa

prepared breakfast by using bear's fat

to fry venison in an iron skillet,

boiling water in a copper kettle, and brewing

tea sweetened with maple sugar in a

yellow-ware teapot. When finished, she

served the meal on pewter plates and in

yellow cups and saucers matching the

teapot. David Jones, a Baptist

missionary who traveled to Indian villages

throughout east-central Ohio in 1772 and

1773, enjoyed a meal of fat buffalo,

beaver tails, and chocolate with his

Indian hosts while Nicholas Cresswell

drank tea with Captain White-Eyes and

Captain Wingenund in their cabin at

Kanaughtonhead (Gnadenhutten) in 1775.15

Native food choices reflected direct

contact with Europeans through the fur

trade, gift giving, military action (the

chocolate that Ridout was given after

his capture had been taken at the same

time that he was), and a selective adop-

tion of European crops and agricultural

practices. Lieutenant John Boyer, an

officer serving with General Anthony

Wayne along the Auglaize and Maumee

Rivers in the summer of 1794, commented

that Indian gardens within the re-

gion produced "vegetables of every

kind in abundance" and that corn fields

measuring "not less than one thousand

acres" stretched for miles along the

rich river flood plains near the Glaize,

a large Indian settlement located at the

confluence of the two rivers. Wayne

himself was amazed at the area's highly

cultivated gardens and noted that he had

never "before beheld such immense

fields of corn, in any part of America,

from Canada to Florida." In addition to

the traditional selection of corn,

beans, and squash, Indian fields throughout

the Ohio frontier frequently contained

European crops such as turnips, cab-

bage, pumpkins, cucumbers,

"Irish" potatoes (a Meso-American staple trans-

ported to the Old World by the Spanish

during the sixteenth century, spread

throughout Europe in the seventeenth

century and then introduced into Ohio

15. John H. Moore, ed., "A Captive

of the Shawnees, 1779-1784," West Virginia History, 23

(July, 1962), 291; Thomas Ridout,

"An Account of My Capture by the Shawaneses Indians,"

Western Pennsylvania Historical

Magazine, 12 (January, 1929), 10, 17.

In another example of

cultural mediation along the frontier, a

white man "about twenty-two years of age, who had

been taken prisoner when a lad and had

been adopted, and was now a chief among the

Shawanese," approached Ridout

immediately after his capture. The otherwise unidentified

mediator "stood up and said to me

in English, 'Don't be afraid, sir, you are in no danger, but

are given to a good man, a chief of the

Shawanese, who will not hurt you; but after some time

will take you to Detroit, where you may

ransom yourself. Come and take your breakfast.'"

See Ibid., 10. See also David Jones, A

Journal of Two Visits Made to some Nations of Indians on

the West Side of the River Ohio, In

the Years 1772 and 1773 (Burlington,

1774), 53; MacVeagh,

The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 111-12.

|

Cultural Mediation, Cultural Exchange 81 |

|

|

|

by the French and English in the eighteenth century), and African foods such as watermelons and muskmelons. "Regular and thrifty" orchards adjacent to Indian homes produced a cornucopia of fruits. Moreover, some tribes also raised livestock. Oliver Spencer, a captive who lived at the Glaize until 1794, claimed that the Indians along the Maumee River kept neither cattle, hogs, nor sheep. But the Moravian missionary David Zeisberger noted that several tribal bands in eastern Ohio were raising cattle because they had be- come "very fond of milk and butter," while his colleague, John Heckewelder, recorded that Indians also owned chickens and semi-domesticated pigs.16

16. Lt. [John] Boyer, A Journal of Wayne's Campaign ... (Cincinnati, 1866), 5; "Wayne to the Secretary of War, 14th August, 1794," American State Papers: Documents Legislative and Executive of the Congress of the United States-Indian Affairs (Washington, D.C., 1832), 1:490. The extent and wide diversity of native horticulture along the Maumee and Auglaize Rivers astounded Wayne's soldiers, eliciting nearly universal comment within the surviving journals and diaries. For representative observations, see "Isaac Paxton," in James McBride, Pioneer History ... (Cincinnati, 1871), 127; Richard C. Knopf, ed., "A Precise Journal of General Wayne's Last Campaign," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 64 (October, 1954), 284-85; Dwight Smith, ed., With Captain Edward Miller in the Wayne Campaign of 1794 (Ann Arbor, 1965), 3-4; Richard C. Knopf, ed., "Two Journals of the Kentucky Volunteers, 1793 and 1794," Filson Club Quarterly, 27 (July, 1953), 263; Reginald E. McGrane, ed., |

82 OHIO

HISTORY

In addition to agricultural practices,

the process of selective cultural re-in-

vention revealed itself in other areas

of the Ohio frontier's economy. When

the missionary David Jones began his

journey into Ohio in 1773, he traveled

well supplied with trade goods and other

useful items. Jones hoped to barter

with the region's Indians for provisions

and other supplies as he moved deep

within the Ohio back country, believing

that "these Indians as yet have not

the use of money." Jones, though,

was badly mistaken. The evangelist

learned that nearly every good or

service that he required during his trip could

only be purchased with cash. At a small

settlement north of the Hocking

River, Jones bought milk for himself and

corn for his horses "at a very ex-

pensive price." Later, he was

forced to pay twenty-five dollars for a horse and

six dollars for a guide to escort him

from the Muskingum River to the Ohio

even though, as Jones later discovered,

the guide "knew not the course."

When he tried to retain the services of

a translator for five pounds a month,

the translator easily dickered the price

up to seven pounds, causing Jones to

comment that the region's Indians

"from the greatest to the least, seem mer-

cenary and excessively greedy of

gain." Complaining that meat could not be

purchased at any price and that milk was

selling at nine-pence a quart and but-

ter for two shillings a pound, Jones

ended his journey "much discouraged ...

by hardships and want of

provisions."17

Other changes within the region's

economy were widely reflected through-

out the Ohio Country. By the early 1770s

many of the Indian communities

located along the Tuscarawas and

Muskingum Rivers had adapted to a cash

economy by becoming market-based centers

for the exchange of goods and

services. When Jones purchased milk and

corn while on his journey, he did so

from a Shawnee woman whom Jones

described as the chief of a small mixed-

band of Delaware and Shawnee families.

The woman, claimed the mission-

ary, was "esteemed very rich"

and frequently boarded travelers in a small cabin

usually occupied by her African slaves.

Moreover, she also kept a sizable

herd of cattle in order to produce both

milk and beef for sale to her guests.

"William Clark's Journal of Wayne's

Campaign," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 1

(December, 1915), 424. See also

Archer Butler Hulbert and William Nathaniel Schwarze,

eds., "David Zeisberger's History

of the Northern American Indians," Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society

Quarterly, 19 (Winter, 1910), 14-16;

John Heckewelder,

History, Manners, and Customs of The

Indian Nations Who Once Inhabited Pennsylvania and

the Neighboring States . . . (Philadelphia, 1876), 147, 157. Heckewelder also noted

the exis-

tence of domesticated house cats. See

also O. M. Spencer, Indian Captivity: A True Narrative

of the Capture of Rev. O. M. Spencer

by the Indians in the Neighborhood of Cincinnati . . .

(New York, 1835), 83. For Indian

orchards, see Franklin B. Dexter, ed., Diary of David

McClure, Doctor of Divinity,

1748-1820 (New York, 1899), 68. For

general discussions of na-

tive agricultural practices, see R.

Douglas Hurt, Indian Agriculture in America: Prehistory to

the Present (Lawrence, 1987), 27-41; J. Mclver Weatherford, Indian

Givers: How the Indians

of the Americas Transformed the World

(New York, 1988), particularly 79-115.

17. Jones, A Journal of Two Visits, 33,

85, 87, 99-101, 104, 108-09. See also Hinderaker,

"The Creation of the American

Frontier," 367-71.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange 83

Likewise, in 1804 the French traveler

Constantin Francois Volney reported

that the Miami chief Little Turtle kept

a cow and made butter at his home

near Fort Wayne, but that he did not

"indulge himself in these things, but re-

serves them for the whites."18

Cultural mediators, usually European men

who had married Indian women

and who maintained either a permanent or

semi-permanent residence among

the western tribes, also played an

active part in the region's transformed econ-

omy. Jones remarked that Richard Conner,

a trader from Maryland, had estab-

lished "sort of a tavern" for

the convenience of travelers on the upper-

Muskingum. Likewise, John Irwine kept a

considerable inventory of goods

at Chillicothe, a Shawnee village near

present-day Frankfort in south-central

Ohio. Irwine sold his wares to travelers

from a log building rented from an-

other Indian who resided in the town.

Chillicothe was also the home of

Moses Henry, a Lancaster trader and

gunsmith who pursued both occupations

for native and European clients at the

village. Henry lived "in a comfortable

manner, having plenty of good beef,

pork, milk, &c.," claimed Jones. "His

generosity to me was singular, and equal

to my highest wishes."19

Commercial establishments such as these

were common throughout the

Ohio frontier. The Glaize, a community

comprised of seven distinct

Shawnee, Delaware, and Miami villages,

was clustered around a centrally lo-

cated trader's town placed at the

confluence of the Maumee and Auglaize

Rivers. Residents of this commercial

district included Englishman George

Ironsides, who maintained a substantial

log dwelling and warehouse at the

community, and a French baker named

Pirault (Perault, Pero) who supplied

bread to both Europeans and natives.

Other entrepreneurs included John

Kinzie, a British silversmith; trader

James Girty, Simon Girty's younger

brother; and two Americans, Henry Ball

and Polly Meadows, who had been

captured after Arthur St. Clair's defeat

in 1791. Meadows supported herself

by taking in laundry and sewing, while

Ball found employment ferrying

goods and individuals to the Maumee

Rapids some forty miles down river.

The same type of commercial center made

up of French and English artisans,

mechanics, and traders also existed at

Kekionga, a Miami village located at

the headwaters of the Maumee River in

present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana.20

The process of intercultural exchange

also led to an evolution in the appear-

18. This and the following paragraph are

drawn from Jones, A Journal of Two Visits, 54-55,

87-88, and Hinderaker, "The

Creation of the American Frontier," 367-71. See also C. F.

Volney, A View of the Soil and

Climate of the United States of America ... (Philadelphia, 1804),

378.

19. For Richard Conner, see also Charles

N. Thompson, Sons of the Wilderness: John and

William Conner (Indianapolis, 1937), 11-14.

20. Spencer, Indian Captivity: A True

Narrative of the Capture of Rev. 0. M. Spencer, 90-

92. Helen Hornbeck Tanner, "The

Glaize in 1792: A Composite Indian Community,"

Ethnohistory, 25 (Winter, 1978), 15-39; M. M. Quaife, ed., "Fort

Wayne in 1790," Indiana

Historical Society Publications, 7 (Summer, 1921), 294-361.

84 OHIO

HISTORY

ance as well as the function of Ohio

frontier communities. As early as the

1750s, European travelers within the

Ohio Country noted that the region's

Indians were living in structures

similar to European log cabins. One of the

earliest descriptions of these dwellings

was made by James Smith, an eigh-

teen year old who had been captured by a

group of Caughnewagas and

Delawares in western Pennsylvania in 1755.

During the winter of 1755-56,

Smith was with a mixed band of

Caughnewagas, Delawares, and Wyandots

when they constructed such a building

near the mouth of the Black River,

west of present-day Cleveland. To

construct the cabin, they

cut logs about fifteen feet long, and

laid these logs upon each other, and drove

posts in the ground at each end to keep

them together; the posts they tied together

at the top with bark, and by this means

raised a wall fifteen feet long, and about

four feet high, and in the same manner

they raised another wall opposite to this, at

about twelve feet distance; then they

drove forks in the ground in the centre of

each end, and laid a strong pole from

end to end on these forks; and from these

walls to the poles, they set up poles

instead of rafters, and on these they tied small

poles in place of laths; and a cover was

made of lynn bark, which will run even in

the winter season.

At the end of these walls they set up

split timber, so that they had timber all

around, excepting a door at each end. At

the top, in place of a chimney, they left

an open place, and for bedding they laid

down the aforesaid kind of bark, on which

they spread bear skins. From end to end

of this hut along the middle there were

fires, which the squaws made of dry

split wood, and the holes or open places that

appeared, the squaws stopped with moss,

which they collected from old logs; and

at the door they hung bear skin, and

notwithstanding the winters are hard here, our

lodging was much better than what I

expected.

It may be that this type of structure

represented an adaptation of the traditional

native longhouse form to European

construction techniques and materials.21

Indian-built log structures never

completely replaced longhouses and bark-

covered wigwams. The Moravian mission at

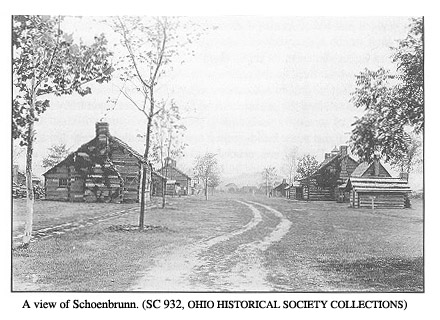

Schoenbrunn, for example, con-

tained about sixty log houses as well as

a substantial number of "huts and

lodges." But as the century

progressed, log homes became increasingly

common across the frontier. By the

1770s, many native log homes had taken

on a distinctively European character.

David Zeisberger remarked that the

Moravian Delawares living in eastern

Ohio "coming much in contact with the

whites, as they do not live more than a

hundred miles from Pittsburgh," had

21. James Smith, An Account of the

Remarkable Occurrences in the Life and Travels of Col.

James Smith . . . (Lexington, 1799), 18. For descriptions of similar

buildings, see John

Heckewelder, Narrative of the Mission

of the United Brethren among the Delaware and

Mohegan Indians ... (Philadelphia, 1820), 298, and Edmund De Schweinitz, The

Life and

Times of David Zeisberger . .. (Philadelphia, 1870), 529; Spencer, Indian

Captivity: A True

Narrative of the Capture of Rev. O.

M. Spencer, 78-81. For a general

discussion, see Donald

A. Hutslar, The Architecture of

Migration: Log Construction in the Ohio Country, 1750-1850

(Athens, 1986), particularly 81-94.

|

Cultural Mediation, Cultural Exchange 85 |

|

|

|

learned to build "proper and comfortable" hewed log homes. In some cases they had even hired whites to come to their villages and build the structures for them. William Albert Galloway, a twentieth century informant who had spent much time in the late nineteenth century with the Shawnee after their removal to Missouri, claimed that the Ohio tribes had purchased axes, saws, and augers for this purpose from French and English traders throughout the frontier era.22 Finely made hewed log homes could be found in Indian communities across the Ohio Country. Zeisberger described Gekelemukpechunk (Newcomers- town) as "a large and flourishing town of about one hundred houses, mostly built of logs." When the Reverend David McClure visited Netawatwes, a village leader living there in September 1772, he commented that "Some of the houses are well built, with hewed logs, with stone chimnies, chambers & sellers. These I was told were built by the english captives in the time of the French wars." Although Netawatwes' home was the largest in the village, it was certainly rivaled by another owned by the village shaman. According to McClure, a stone-lined cellar, a stair case leading to the second story, a well- built stone chimney and fireplace, closets, and a first floor divided into several smaller rooms gave the building the appearance of an English dwelling.23

22. Hulbert and Schwarze, "David Zeisberger's History," 17-18, 380; William Albert Galloway, Old Chillicothe (Xenia, 1934), 13. 23. De Schweinitz, Life and Times of David Zeisberger, 366; Dexter, Diary of David |

86 OHIO

HISTORY

It was not just Indian homes that

resembled English buildings. Entire vil-

lages took on the appearance of European

settlements. Nicholas Cresswell

described Schoenbrunn as "a pretty

town ... regularly laid out in three spa-

cious streets which meet in the centre,

where there is a large meeting house

built of logs." Cultural

transmission, though, remained selective. Many

Indian villages retained the organic

and, to European eyes, seemingly haphaz-

ard placement of structures

traditionally seen in native communities. David

Zeisberger noted that when building

their towns, the Indians rarely considered

a "regular plan." David Jones

echoed that observation. Commenting upon

the arrangement of buildings at

Chillicothe, he remarked that there was no

more "regularity observed in this

particular than in their morals, for any man

erects his house as fancy directs."24

Mutual transculturation was also

reflected in the social customs and institu-

tions that made up the fabric of

everyday life along the Ohio frontier. In early

September 1775, Cresswell was at

Coshocton where he witnessed an Indian

dance. According to the trader, the

Indians made their music with "an old Keg

with one head knocked out and covered

with a skin and beat with sticks."

Caught up in the excitement of the

moment, Cresswell, who had been

"painted by my Squaw in the most

elegant manner," stripped off all of his

clothing except for his shirt,

breechclout, leggings, and moccasins. Joining

the dance, he moved around the campfire

"whooping and hallooing" with the

most "uncouth and antic postures

imaginable." While Cresswell danced

across the cultural divide, his Indian

associates also used music to redefine

their place within frontier society. At

Newcomerstown three days after the

dance, Cresswell listened while an

Indian made "tolerable good music" play-

ing an old tin violin. The following

evening the trader was at Gnadenhutten.

Visiting the village's chapel, Cresswell

watched an Indian convert play the

congregation's spinet piano during the

Moravian worship service.25

Everyday social conventions also showed

the influence of cultural re-inven-

tion. David Zeisberger noted that when

Indians greeted one another, they did

so by shaking hands. Charles Johnston

was with a group of settlers floating

down the Ohio River in 1790 when his

boat was ambushed by Indians lying

in wait near the shore. The attackers

quickly overpowered the vessel, killing

several of Johnston's companions and

wounding others. The survivors were

herded toward one end of the boat as the

Indians boarded, killed the wounded,

stripped the dead, and threw the bodies

overboard. Johnston was convinced

that he and the others were about to be

summarily executed. To his immense

surprise, the war party's leader

approached Johnston, took the frightened

McClure, 61.

24. MacVeagh, The Journal of Nicholas

Cresswell, 106; Jones, A Journal of Two Visits, 56;

Hulbert and Schwarze, "David

Zeisberger's History," 87.

25. MacVeagh, The Journal of Nicholas

Cresswell, 109- 12.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange 87

American's right hand and forearm in

both of his hands and after pumping

them vigorously, exclaimed

"How-d'ye-do! How-d'ye-do!" Later, as he was

being led to his captor's home in

northern Ohio, Johnston commented that all

the Indians they met had "caught

the common salutation" and greeted each

other by shaking hands and exchanging

How-d'ye-dos. The custom seems to

have been of recent origin. James Smith

explicitly noted that in the 1750s

the Indians with whom he was familiar

did not use "how do you do," but re-

lied instead on greetings in their own

language that translated into exchanges

such as "You are my friend; Truly

friend, I am your friend," and "Cousin, you

yet exist; Certainly I do."26

Inter-cultural contact led Europeans to

incorporate Indian words and phrases

such as "squaw" and

"succotash" into their vocabularies. Native Americans

throughout the Ohio Country were equally

quick to selectively adopt

European expressions and figures of

speech. Charles Johnston noted that

while only two of the Indians in his

party could speak or understand his lan-

guage, virtually all of them cursed in

English. Oliver Spencer remembered

that when a pack horse carrying a heavy

load collapsed along a trail and re-

fused to go further, the horse's Indian

owner "began in broken English to

curse him, and after loading the poor

animal with all the opprobrious epithets

he could think of, left him lying in the

path." Likewise, Colonel William

Christian, an officer in the Virginia

Militia, reported that during the 1774

Battle of Point Pleasant, Indian

warriors came close to the American lines and

"damn'd our men often for

Sons-of-Bitches."27

James Smith claimed that the Indians

"never did curse or swear, until the

whites learned them." Furthermore,

he also stated that the Ohio Indians

would frequently use European expletives

without understanding their mean-

ing. While Smith was living with the

Ohio tribes, Tecaughretanego, one of

his Caughnewaga companions, became

angered and used the phrase "God

damn it" in Smith's presence. The

outburst offended Smith and when he ex-

plained that the expression meant

"calling upon the great spirit to punish the

object" that his friend was

displeased with, his companion first became em-

barrassed and then confused. "He

stood there for some time amazed," said

Smith,

and then said if this be the meaning of

these words, what sort of people are the

whites? When the traders were among us

these words seemed to be intermixed with

26. Hulbert and Schwarze, "David

Zeisberger's History," 115; Charles Johnston, A

Narrative of the Incidents Attending

the Capture, Detention, and Ransom of Charles Johnston, of

Botetourt County, Virginia . . . (New York,

1827), 16 and 40; Smith, An Account of the

Remarkable Occurrences, 78.

27. Johnston, A Narratives of the

Incidents, 40; Spencer, Indian Captivity: A True Narrative

of the Capture of Rev. 0. M. Spencer,

49-50. "Col. William Christian to

Col. William Preston,

15th Oct. 1774," 3QQ121, William

Preston Papers, Draper Collection, State Historical Society

of Wisconsin.

88 OHIO HISTORY

all their discourse . . . he said the

traders applied these words not only wickedly,

but often times very foolishly and

contrary to sense or reason. He said, he remem-

bered once of a trader's accidentally

breaking his gun lock, and on that occasion

calling out aloud God damn it-surely

said he the gun lock was not an object worthy

of punishment for Owaneeyo, or the Great

Spirit; he also observed the traders of-

ten used this expression when they were

in a good humour and not displeased with

any thing. I acknowledged that the

traders used this expression very often, in a

most irrational, inconsistent, and

impious manner, yet I still asserted that I had

given the true meaning of these words.

He replied, if so, the traders are as bad as

Oonasahroona, or the underground

inhabitants, which is the name they give the

devils.28

Social institutions, as well as social

customs, were re-invented in the wake

of the region's inter-cultural contact.

Native marriages were less permanent,

though no less solemn, than white

unions. According to John Heckewelder,

when Indians entered into marriage it

was understood by both partners that

they would not live together any longer

"than suits their pleasure or conve-

nience." "The husband may put

away his wife whenever he please," claimed

the evangelist, "and the woman may

in like manner abandon her husband."

European men, particularly traders and

merchants who resided in the Ohio

Country, frequently adopted the Indian

mode of marriage and took Indian

wives in the Indian fashion.29

Other Europeans occasionally attributed

the transitory nature of Indian mar-

riages and the traders' readiness to

enter into such unions to a widespread li-

centiousness among the Indians and a

general degradation of moral standards

along the frontier. David Jones, for

example, claimed that Indian women "are

purchased [by their husbands] by the

night, week, month or winter, so that

they depend on fornication for a

living," while Nicholas Cresswell described

the settlers living near Fort Pitt as

"nothing but whores and rogues." Indians,

however, and the Europeans who married

them, understood the marriage pact

differently.30

Kinship formed the fundamental basis of

native culture. Many of the activi-

ties and relationships that made up

village life as well as the trading partner-

ships and diplomatic allegiances that

defined a band's place within the broader

scope of native society were predicated

upon familial affiliation. Marriage

permitted Indians to extend political

and economic ties to the white world and

to carefully regulate the process

through which Europeans became fully ac-

cepted, integrated, and participating

members of Indian society. Natives bene-

28. Smith, An Account of the

Remarkable Occurrences, 42.

29. Heckewelder, History, Manners,

and Customs of the Indian Nations, 154. David

Zeisberger also described this type of

marital arrangement but was quick to point out that

"there are many cases where husband

and wife are faithful to one another throughout life."

See Hulbert and Schwarze, "David

Zeisberger's History," 79.

30. Jones, A Journal of Two Visits, 75-76;

MacVeagh, The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 98.

See also Dexter, Diary of David

McClure, 91.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange 89

fited from this arrangement in several

ways. Marriage allowed tribal bands to

enforce social customs and impose

standards of behavior and formalized social

obligations upon their new European

members. Further, trade acted as a

means of preserving peaceful relations,

both between natives and whites and

between tribal bands. Marriage served to

stabilize the broad inter-cultural bond

between Indians and Europeans and to

guarantee the supply of trade goods

necessary for the maintenance of

intra-cultural alliances. Whites benefited

from the arrangement as well. The power

of these marriages to cement eco-

nomic and diplomatic relationships was

self-evident to Captain Hector

McLean, the British commander at Fort

Maiden (Amherstburg, Ontario) in

1799. According to McLean, either

"marriage or concubinage" connected most

of the officers attached to the British

Indian Department at the post to the

Ohio Valley Shawnee. Likewise, the

Indian woman who accompanied

Nicholas Cresswell while he traveled

through Ohio in 1775 made his cloth-

ing, acted as a translator, tended his

horses, prepared his camp, and undoubt-

edly arranged for him to meet the tribal

leaders with whom he frequently dealt.

Cresswell was well aware of the

importance of this woman to his success.

"However base it may appear to

conscientious people," he noted, "it is abso-

lutely necessary to take a temporary

wife if they have to travel amongst the

Indians." The transculturation of

the Ohio Country, therefore, was based

upon the exchange of individuals as well

as goods, ideas, and customs.31

Alexander McKee's father, Thomas McKee,

a western Pennsylvania Indian

trader and sometime agent with the

British Indian Department, died near his

trading post along the Susquehanna River

in 1769. Four years later John

Parrish, a Quaker missionary from

Philadelphia, and two companions traveled

through western Pennsylvania and into

the Ohio Country. Their journey

was, in part, a social one, an

opportunity too long delayed to renew friend-

ships and strengthen acquaintances

throughout the region. On July 26th, in a

small settlement west of the Ohio River,

Parrish had the extraordinary good

fortune to run into an old and dear

friend, Thomas McKee. At their meeting

McKee, after inquiring about the health

of his friends, gave Parrish and his

companions a "hearty welcome,"

invited them to accompany him, and es-

corted the group to his home.

Throughout the following week, Parrish

and his friends were entertained

with great hospitality. McKee's Indian

wife lavished her attention on them,

saw to their every comfort, and prepared

their meals from the best provisions

31. The British Indian Department was

the Crown agency charged with maintaining Great

Britain's economic and military alliance

with the Ohio Country tribes. "Captain Hector

McLean to Major James Green, August 27,

1799," Michigan Pioneer and Historical

Collections, 40 vols. (Lansing, 1877-1929), 12:305; MacVeahgh, The

Journal of Nicholas

Cresswell, 102-08, 113-14, 122. See also Dexter, Diary of David

McClure, 53; J. B. Brebner,

"Subsidized Intermarriage with the

Indians: An Incident in British Colonial Policy," Canadian

Historical Review, 6 (March, 1925), 33-36, and Merrell, "Our Bond of

Peace," 198-201.

90 OHIO

HISTORY

available at the town. By August 3rd it

was time to return. McKee, having

business to transact in Pittsburgh,

decided to accompany the Quaker and his

friends to the frontier outpost. As they

traveled up the Ohio River, they

paused at Alexander McKee's trading post

and acquired the provisions to con-

tinue their journey. The party then

continued to Pittsburgh where, according

to Parrish, McKee met with all of the

town's "men of note."32

Thomas McKee was an Indian, a Delaware

who, as a token of respect for

his friend Thomas McKee, had taken the

trader's name and retained it after his

death. James Kenny, a Pittsburgh trader,

recorded many such Indians includ-

ing Jimmy Wilson, John Armstrong, Sir

William Johnson, William

Turnum, and John Doubty, as they

bartered for provisions at his establish-

ment. European traders found Indian

names notoriously difficult to pro-

nounce, and it is likely that many of

these Indians used their European names

only to facilitate their dealings with

Kenny and the other merchants within

the region. On one occasion, for

example, Kenny noted that when a young

Indian man "having no English

name" came to trade, "I gave him my name,

which he said he would keep."

Thomas McKee's acceptance of his friend's

name, though, appears to be more than a

matter of mere convenience.33

McKee bore the outward sign of a deeper

cultural reality. The Ohio frontier

was a place of great cultural

restlessness, a setting where personal identity re-

flected the impermanence of one's

ethnic, national, or racial affiliation.

McKee was part of a world that permitted

individuals to cross racial and ethnic

barriers both symbolically and literally

with a considerable degree of intimacy

and completeness. Indeed it was a world

that allowed certain individuals to be

either Indian or European at their

discretion. The eastern woodland Indians

had long used the "mourning

war" to take revenge upon their enemies. The

mourning war was fought using

small-scale raids to acquire either Indian or

European captives. These prisoners would

later be adopted into the tribe that

had captured them to replace other

tribal members who had died from disease

or combat. After James Smith's capture,

he was bathed, dressed in Indian

clothing, painted in Indian fashion, and

brought before a council of village

leaders. Eventually, one of the tribal

elders arose and said "My son, you are

now flesh of our flesh, and bone of our

bone."

32. "Extracts From Journal of John

Parrish, 1773," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and

Biography, 16 (October, 1892), 442-48; John Lacey, "Journal

of a Mission to the Indians in

Ohio by Friends from Pennsylvania,

July-September, 1773," in William Henry Egle, Notes and

Queries: Historical, Biographical,

and Genealogical, Relating Chiefly to Interior Pennsylvania,

12 vols. (Harrisburg, 1893-1900),

7:103-07.

33. John W. Jordan, "Journal of

James Kenny, 1761-1763," Pennsylvania Magazine of

History and Biography, 37 (January and April, 1913), 1-47, 152-201. For Thomas

McKee's

tribal affiliation, see American

Archives: Consisting of a Collection of Authentick Records,

State Papers, Debates, and Letters

and other Notices of Publick Affairs. ... In Six Series

(Washington, D. C., 1833), 4th series,

1:478.

Cultural Mediation, Cultural

Exchange 91

By the ceremony which was performed this

day, every drop of white blood was

washed out of your veins; you are taken into the

Caughnewaga nation, and initi-

ated into a warlike tribe; you are

adopted into a great family, and now received with

great seriousness and solemnity in the

room and place of a great man; after what

has passed this day, you are now one of

us by an old strong law and custom-My

son, you have now nothing to fear, we

are now under the same obligations to love,

support and defend you that we are to

love and to defend one another, therefore you

are to consider yourself as one of our

people.

Smith at first doubted the truth of what

he had been told, but later commented

that "from that day I never knew

them to make any distinction between me

and themselves in any respect

whatever." This evolving, fluid sense of per-

sonal identity shared by both Indians

and Europeans reflected the culturally

complex and pragmatic nature of the Ohio

frontier. Personal identity could be

expediently re-invented as circumstance

required. For many who lived in the

Ohio back country, racial and ethnic

affiliation became a temporary response

to altered personal relationships,

shifting political contexts, and emerging

economic opportunities.34

Indians and Europeans alike, then, had

transformed the Ohio Country and

with it themselves. An overtly

negotiated process of selective cultural ex-

change defined the encounter between

Native Americans and whites along the

Ohio frontier and had fashioned the

region into a zone of mutual re-invention.

Cultural mediators were at the heart of

this exchange. Relations between

Europeans and natives throughout the

Ohio hinterlands were always complex,

comprised of an interwoven net of

competing interests. For much of the

early frontier era, the process of

transculturation permitted both parties to rec-

oncile their differences and allowed

each to engage the other peacefully, prof-

itably, and with a degree of

understanding otherwise impossible.

34. Smith, An Account of the

Remarkable Occurrences, 10-11. See also James Axtell, "The

White Indians," in James Axtell, The

Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial

North America (Oxford and New York, 1985), 302-28; Daniel K. Richter,

"War and Culture:

The Iroquois Experience," William

and Mary Quarterly, 40 (October, 1983), 528-59.