Ohio History Journal

|

Lucy Webb Hayes and her Family by EMILY APT GEER |

|

|

|

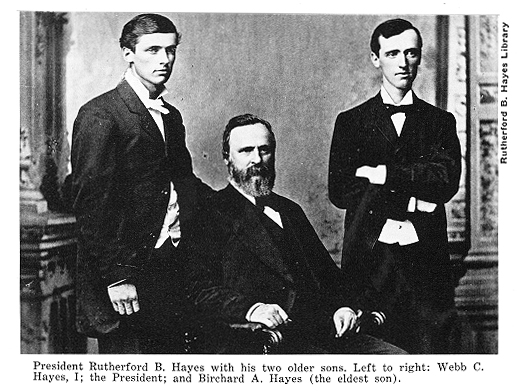

The public life of Rutherford Birchard Hayes has been studied by many historians but little has been written about the friendly, sparkling woman he married and their large and active family of eight children. Lucy Webb Hayes's concern for people helped her develop a lively interest in politics that served her equally well as the wife of a city solicitor in Cincinnati and as mistress of the White House while her husband was President. Their oldest son, Birchard Austin, became a prominent lawyer in Toledo; their second son, Webb Cook, after a career as a manufacturer and an army colonel, founded the Hayes State Memorial at Spiegel Grove in Fremont, Ohio. Rutherford Platt and Scott Russell were in various business fields; and Fanny Hayes Smith, the only girl among the Hayes children, lived until 1950, still able to recall vividly the days of her childhood in Washington and Spiegel Grove. Two little boys born during the Civil War in addition to the last Hayes baby died during the second summer of their lives. NOTES ON PAGE 186 |

34 OHIO HISTORY

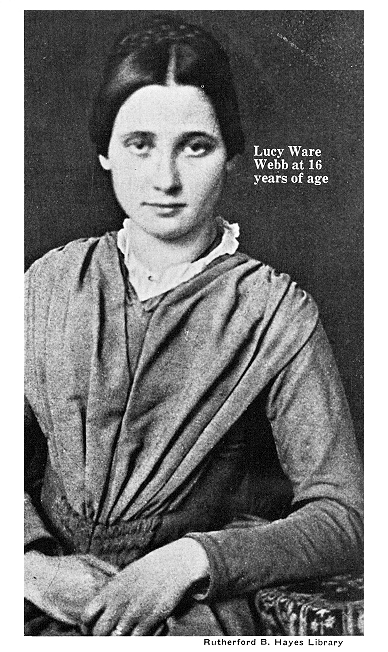

This account of the Hayes family begins

with the courtship of Lucy Ware

Webb by Rutherford B. Hayes; and

continues on to describe their early

married life in Cincinnati, the

difficult years of the Civil War, the period

of Hayes's political ascendancy, and

finally their retirement to Spiegel

Grove. Throughout the narrative, Lucy

Webb Hayes, as wife and mother,

is naturally the focal point about which

the life of the family revolves.

Rutherford Birchard Hayes and Lucy Ware

Webb were married on

December 30, 1852. The story of their

romance, from the time they first

met in Delaware to the day of their

marriage, was carefully chronicled by

Hayes in his Diary. By looking

back through the pages, he found the first

mention of Lucy on July 8, 1847. In a

letter written after their engagement,

he claimed that he had heard a great

deal about her from his mother's

friends, but because Lucy was only

sixteen, she impressed him as "a bright

sunny hearted little girl not

quite old enough to fall in love with--so I

didn't."1

A few years earlier, Lucy's widowed

mother, Maria Webb, had moved

from Chillicothe, where she had lived

all her life, to Delaware so that her

two sons, James and Joseph, could attend

the newly established college de-

partment of Ohio Wesleyan.2 Lucy

studied for a while in both the pre-

paratory and the college departments of

the school, although female

students were not officially enrolled at

that time in the college division. On

a term report that listed merit points

for Lucy Webb in both departments,

her conduct was marked

"unexceptionable" (beyond reproach).3

Sophia Hayes, Rutherford's mother, had met

the Webb family while

visiting in Delaware and had decided

that the "bright-eyed" Lucy, from a

good family and particularly beyond

reproach in her religious convictions,

would make a suitable wife for her son.

Mrs. Webb also encouraged the

friendship by taking Lucy with her when

she visited Mrs. Hayes in Colum-

bus, where she lived with her daughter,

Fanny Platt.4 Letters from Hayes

show that he was aware of the

conspiracy. Shortly after meeting Lucy, he

commented to his sister, "Mother

and Mrs. Lamb [a family friend] selected

a clever little schoolgirl named Webb

for me at Delaware."5 And a few

months later, half-teasingly, he told

his mother, "I wish I had a wife to

take care of my correspondence . . . I

hope you and Mother Lamb will see

to it that Lucy Webb is properly

instructed in this particular."6

In spite of the efforts of the

matchmakers, Rutherford Hayes and Lucy

Webb saw no more of each other until

after Christmas, 1849, when Hayes

moved to Cincinnati to establish a law

practice. He had heard that Lucy

was attending the Wesleyan Female

College in Cincinnati and had decided

that he wanted to see her again as soon

as possible. Hayes did not find Lucy

in until a second visit to the college

on January 5, 1850.7 After that the

young lawyer's frequent appearances at

the college's Friday night receptions,

and comments in his Diary reveal

his growing interest in the young girl.

Perhaps he saw her graduate from college

in June, 1850, and heard her read

her commencement essay, "The

Influence of Christianity on National Pros-

perity."8

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 35

A year later, Hayes was writing in his Diary,

"I guess I am a great deal

in love with-- [Lucy Webb] . . . Her low

sweet voice . . . her soft rich eyes."

Bemused as he was, Rutherford Hayes was

practical enough to look for

other reasons for his attachment.

"Intellect, she has too," he added, "a quick

spritely one, rather than a reflective

profound one. She sees at a glance what

others study upon, but will not,

perhaps, study out what she is unable to

see at a flash. She is a genuine woman,

right from instinct and impulse

rather than judgment and reflection."9

Lucy did not record her emotions, but

her intuitiveness must have pre-

pared her for Hayes's proposal on June

13, 1851, a Friday night. A delight-

ful paragraph from his Diary describes

the scene:

On a sudden the impulse seized me. . . I

grasped her hand hastily

in my own and with a smile--but

earnestly and in quick accents said--

"I love you." She did not

comprehend it--really no sham. . . . I knew

it was as I wished, but I waited,

perhaps repeated . . . until she said,

"I must confess I like you very

well." A queer, soft, lovely tone, it stole

to the very heart, and, I, without loosing

her hand took a seat by her

side and--and the faith was plighted for

life! . . . She said, "I don't

know but I am dreaming. I thought I was

too light and trifling for

you."10

Happy weeks followed until Lucy left for

a visit to the country and

Hayes discovered, much to his concern

and chagrin, that she very much

disliked letter writing.11 As

sometimes happens with voluble people, Lucy

Webb found it difficult, as well as

tedious, to record her thoughts on paper,

nevertheless her infrequent letters to

Rutherford Hayes were engaging

accounts of her activities and her

efforts to be elusive when questioned

about him. Lucy wrote that it was

amusing to keep their friends guessing

but his "likeness" lay hidden

"in a little corner of my formerly large heart,"

and she asked him to think kindly of her

as David did of Dora (an allusion

to characters in David Copperfield).12

Neither Rutherford Hayes nor Lucy Webb

seemed to be in any hurry

to set a date for their marriage.

Doubtless Hayes wanted to be able to sup-

port a household with a minimum of

assistance from his uncle and bene-

factor, Sardis Birchard, but not until

the summer of 1852 did Lucy's let-

ters show either inclination or desire

to set a wedding date. Perhaps Hayes's

infrequent letters from Columbus and

Fremont, where he was spending

the summer, with their gay accounts of

picnics and buggy rides, along with

the realization that she was approaching

twenty-one (August 28, 1852),

provided the impetus toward matrimony

that Lucy needed.13

Rutherford Hayes, who may have

deliberately exaggerated his social

activities, was also thinking about

matrimony, and for the first time men-

tioned living in Fremont. Uncle Sardis

had told his nephew that he would

like to build him a "summer

retreat" in a "pleasant grove," if he would

promise to spend part of the summer in

Fremont. "How say you," he asked

in a letter to Lucy, "shall I

promise? I feel like doing it."14

In August, Fanny Platt and her daughter,

Laura, joined Hayes at the

36 OHIO HISTORY

Valette farm near Fremont where Sardis

Birchard was living. On the last

evening of their visit, Rutherford's

marriage prospects were discussed, and

in answer to questions about Lucy, Fanny

described her as "quite pretty . . .

a charming disposition, is merry as a

cricket and if she were here tonight

her laugh would make Uncle ten years

younger." At this point, Sardis

interrupted, "Well why doesn't the

fool marry her? I don't believe she'll

have him."15

Soon after Hayes returned to Cincinnati

in September, he was able to

assure his uncle that Lucy and he

planned to be married as soon as her

brother Jim's health improved.16 He

hoped that they would not need finan-

cial assistance but would call upon

Birchard if necessary. By December

third, with his law practice measurably

increased and James Webb feeling

better, Hayes could tell his uncle that

they had agreed "as to the marrying

[date]."17

On December 30, 1852, the wedding took

place in the Webb home at

141 Sixth Street, Cincinnati. The two

o'clock ceremony was performed by

their friend, Professor L. D. McCabe of

Ohio Wesleyan University, before

a company of about forty relatives and

friends. Rutherford's niece, Laura

Platt, held Lucy's hand during the

ceremony.18 According to an account

by Lucy's friend, Eliza Davis, the

"radiant" bride looked lovely in her

figured satin dress, simply tailored

with a full skirt pleated to a fitted bodice,

and floor length veil fastened with

orange blossoms. The groom, Mrs. Davis

jokingly commented, was an honest

looking man who "might turn out

better than I expected."19 That

evening Lucy and Rutherford Hayes

boarded the five o'clock train for

Columbus where he hoped to combine

appearances before the Ohio Supreme

Court with a pleasant honeymoon.20

The years from 1853 to the beginning of

the Civil War were happy ones

for the growing Hayes family. The first

three of their children were born

during this period: Birchard Austin on

November 4, 1853; Webb Cook,

March 20, 1856; and Rutherford Platt,

June 24, 1858. For Rutherford

Hayes, who was elected to his first

political office in 1859, it was a time of

professional achievement as well as

marital bliss. His happiness and pride

in his loving wife and bouncing sons

were tempered only by the death in

1856 of his adored sister, Fanny H.

Platt.

During the month-long honeymoon with

Fanny Platt's family in Colum-

bus, Lucy's happy disposition and enjoyment

of the children won her the

affection of the household. Hayes

presented his arguments before the

Supreme Court the first week, and while

waiting for the decision "proudly"

escorted his wife to the social events

of the season. Fanny, describing their

activities wrote, "So to dinner

parties, tea drinking and evening fandangoes

they went with unremitted zeal."21

In February, the young couple returned

to Mrs. Webb's home in Cincinnati where

they remained for over a year.

At the end of the second month of wedded

life, Rutherford Hayes wrote

in his Diary, "A better wife

I never hoped to have. . . This is indeed life. . .

Blessings on his head who first invented

marriage."22 Lucy's letters echo

the same sentiment although she missed

her husband when he attended

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 37

club meetings and political gatherings.

"Well have patience a little longer,"

she entered in his diary.

"Woman is the only enemy that has ever overcome

the Club."23

Much of Lucy and Rutherford Hayes's

first summer together was spent

visiting his sister's family in

Columbus, Sardis Birchard in Fremont, and

Lucy's relatives in Chillicothe. Lucy's

grandfather, Isaac Cook, had been

a pioneer settler in Chillicothe recognized

for his qualities of leadership by

appointment as an associate justice of

the common pleas court and by elec-

tion to the state legislature.24 One

of his sons, Matthew Scott Cook, a fa-

vorite of the Webb children, married

Ellen Tiffin, daughter of Ohio's first

governor, and settled on a farm near

Chillicothe called Buena Vista. Fol-

lowing the death of Maria Webb's

husband, Dr. James Webb, from cholera

when Lucy was two years old, Scott Cook

had become his sister's chief

financial adviser.25 Lucy

also enjoyed visiting her aunts, Phebe Cook Mc-

Kell in Chillicothe, Margaret Cook Boggs

and Lucy Cook at Elmwood,

near Kingston, and other relatives in

the area. The highlight of their vaca-

tion though was a three-day trip in

August to Niagara Falls. The honey-

moon of their dreams, a trip up the St.

Lawrence had to be deferred (until

1860) , partly because of Lucy's

pregnancy.26

Their first child, a son, was born at

his grandmother's house on Sixth

Street on November 4, 1853. For a while

the baby's only name seemed to

be "Puds," until Fanny Platt's

and Sophia Hayes's protests caused Ruther-

ford and Lucy to name the baby Sardis

Birchard [later changed to Birchard

Austin].27 Perhaps it was

fortunate for the relatives' sense of propriety that

they did not realize that Lucy and

Rutherford's parenthood would be char-

acterized by a tendency to wait for the

name to take possession of the child.

With space in Maria Webb's house no

longer adequate for the growing

family, Hayes proposed to buy his own

home.28 In April, when Mrs. Webb

began to close her house, Lucy and

"Birchie" left for extended visits with

the Platts in Columbus, and relatives in

Chillicothe. Business affairs, the

search for a house, and then supervision

of its renovation kept Hayes in

Cincinnati most of the summer. Finally

the repairs were completed and

on September 4, 1854, the Hayes family

began to move into their own home

at 383 Sixth Street, Cincinnati. Hayes

wrote in his Diary that there was a

great deal of laughing over the assorted

loads of furniture, "a good deal of

Lucy's mother's when she went to

housekeeping."29

With the Hayes family settled in their

own home, visits from his mother

and sister were more frequent and

extensive. During one of her visits, the

mother-in-law noted in a letter to her

brother that Rutherford seemed too

busy to provide "anything but money

for his family."30 Fanny Platt's im-

pression of her brother's home was

somewhat different. She wrote that Lucy

made easy work of housekeeping, and

"Ruddy" romped with his boy and

turned the "whole of life into a

joke."31

The winter of 1855-56 was the coldest on

record for Cincinnati. Accord-

ing to Hayes's Diary, the

Ohio River was frozen solidly enough through the

month of January for "cattle,

teams, and runaway slaves" to cross on the

38 OHIO HISTORY

ice.32 On March 20, 1856, the

second Hayes son, James Webb (later changed

to Webb Cook), was born. While Lucy's

brother, Dr. Joseph Webb, as-

sisted with the delivery, Rutherford,

who was probably thinking about his

political future as a member of the new

party being formed from the dissi-

dent groups of the time, read

Jefferson's letters to Madison, particularly

noting the one in which Jefferson spoke

of his resolution to remain in pri-

vate life the rest of his days. "A

resolution," Hayes wrote, "about as well

kept as such resolutions usually are by

public men."33

Sophia Hayes came to visit her newest

grandchild, and stayed until solici-

tude over Fanny's approaching

confinement, her seventh, caused her to

hurry back to Columbus.34 In

June, Mrs. Platt gave birth to twin daugh-

ters, both of whom died almost

immediately. Fanny, who barely survived,

lingered in a critical condition for a

month before she too died on the

sixteenth of July.35

The Platt household in Columbus was

desolate, and Rutherford Hayes

poured out his grief in letters to

friends and relatives, and wrote in his

Diary: "The dearest friend of childhood--the affectionate

adviser, the con-

fidante of all my life--the one I loved

best is gone."36

Intense as was Hayes's grief, the loss

of Fanny was a greater one for Lucy.

Fanny's unusual intellectual ability and

range of interests had left an in-

delible impression upon her brother; but

Lucy, who was just twenty-five,

needed the stimulation of prolonged

association with an intelligent and

loving sister, such as Fanny Platt.

Fortunately, Lucy and Rutherford Hayes

could turn from their sorrow

to the absorbing political drama of

1856. The new Republican party, bol-

stered by success in Ohio the previous

year, entered the national arena

with the famous explorer, John C.

Fremont, as its candidate for President.

Lucy Hayes's latent interest in politics

was aroused by the antislavery senti-

ments of some of the members of the new

party, and by the picture of the

glamorous Fremont and his romantic wife,

Jessie Benton, as the ideal

couple to grace the White House. After

early election returns indicated

that Fremont would lose to James

Buchanan, Hayes wrote to his uncle,

"Lucy takes it to heart a good deal

that Jessie is not to be mistress of the

White House after all."37

Encouraged by Lucy's continued interest

in politics and his own inclina-

tions, Rutherford Hayes began to allow

his name to be mentioned for pub-

lic office. His reputation for

professional competency and his acceptability

to divergent political groups caused the

City Council to appoint him to

complete a term as City Solicitor for

Cincinnati in December 1858; at the

election a few months later he won the

office for two years.38

By this time a third son had been born,

June 23, 1858. This boy was

eventually named Rutherford Platt. Two

weeks later, Lucy came down

with a severe case of rheumatism, an

attack similar to one she had suffered

in 1851.39 The periodic recurrences of

this rheumatic condition plus the

severe headaches that she suffered

throughout the year belied the impres-

sion of nineteenth century writers that

Mrs. Hayes possessed robust health.40

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 39

Christmas in 1858 was a particularly

happy day for the Hayes family.

Lucy and Rutherford watched over their

children as they played beneath

the Christmas tree, which their German

"girls" had spirited into the base-

ment and trimmed to the surprise and

delight of the family. Five year old

Birtie was looking at his gift books, Jack

the Giant Killer, Hop o' My

Thumb, and Aladdin's Lamp, while little Webb,

persevering and deter-

mined even at two-and-a-half,

entertained the bright-eyed baby Ruddy.41

Through these years, the boys suffered

from the usual diseases of child-

hood. At the end of one long siege of

illness, Lucy lamented, "Sick chil-

dren -- then cross children -- poor

house girl -- and all the usual house-

hold troubles."42

Showing that he too was aware of family cares, Ruther-

ford jested in a letter to his niece:

I am in the boy business chiefly these

days. Playing with the boys,

scolding . . . Lucy is in a different

line of the boy business--washing

the hands of boys . . . making boys

pants, jackets, and shirts . . . Mother

Webb too has her branch of boy

enterprise . . . nursing . . . imparting

religious instruction . . . Uncle Joe is

overwhelmed by the boys, They

own him, jump on him . . .43

In August 1860, while the boys stayed

with their Grandma Webb, Lucy

and Rutherford took the long deferred

trip up the St. Lawrence River to

Montreal and Quebec, thence by rail to

visit Hayes's relatives in Vermont,

and finally back to New York and

Philadelphia. Hayes noted in his Diary

that Lucy loved sitting in the bow of

the boat as it plowed through the

rapids of the St. Lawrence, and

"like a child wished for more." According

to his carefully kept accounts, the

month-long trip cost $310.77.44

On their return to Ohio, they stopped in

Fremont to see how Sardis

Birchard was progressing with the house

he had started to build in Spiegel

Grove. Because he had assumed from the

beginning that Rutherford and

Lucy would live there some day, Sardis

had consulted his nephew about

every phase of the building.45 Hayes

had told his mother that the house

was "large and very handsome."46

Conservative, but at the same time sensi-

tive to the needs of humanity, Sophia

Hayes had suggested that the house

be finished "in a plain

manner." She did not think that a careful man like

her brother, Sardis Birchard,

"should encourage extravagance in Ohio

when there is so much need of money for

Preachers and Teachers to in-

struct the ignorant . . . The character

of our inhabitants is much more

important than their stile [sic] of

living."47

Apparently a long visit by Sophia Hayes

to her son's home during the

winter of 1860-61 created tensions

because Lucy managed to extend a trip

to a wedding in Chillicothe through the

Christmas holidays. The year

ended with a slight note of discord, one

of the few that appears in the

manuscripts of the Hayes family. On

Christmas Eve, 1860, Rutherford

wrote in his Diary, "Lucy

gone to Chillicothe. All ought to be at home to

make home happy on these festal

days." But he added a cheerful note:

"Eleven years ago tonight I came to

Cincinnati. A prosperous happy term

of life I have had. I cannot anticipate

a happier in the years to come. Only

40 OHIO HISTORY

one sad spot in all the time--the death

of my dear, dear sister. Mother is

with us."48

When the Hayes family discussed the

Civil War years, their most pleas-

ant memories were of the months they had

spent together in army camps

along the Kanawha River in western

Virginia. There were other periods

and events that recalled less happy

memories: the first months of separa-

tion, fear of Confederate raids into

southern Ohio, the Battle of South

Mountain where Hayes suffered his most

painful wound of the war, and

the campaign of 1864 in the Shenandoah

Valley.

When the news of the firing on Fort

Sumter by Confederate batteries

reached Cincinnati, Lucy Hayes,

unassailed by the doubts and questions

that worried more reflective minds, was

all for war. She even felt that if

she had been at Fort Sumter with a

garrison of women there might have

been no surrender.49 As she

reported in a letter, Sumter caused Cincinnati

to rally to the Union cause. "The

Northern heart," she wrote, "is truly

fired--the enthusiasm that prevails in

our city is perfectly irresistable. Those

who favor secession or even sympathy

with the South find it prudent to be

quiet."50

Rutherford Hayes might have left the

fighting to younger men without

family responsibilities, but Lucy's

enthusiasm for the cause and his own

inclination caused him to decide, with

his friend, Judge Stanley Matthews,

"to go into the service for the

war."51 After several weeks of communica-

tions, Matthews and Hayes were accepted

as lieutenant-colonel and major

respectively of the newly formed

Twenty-Third Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

It was the first Ohio regiment enlisted

for three years or the war. The vol-

unteer companies, mostly from the

northeastern part of the state, were

mustered into the regiment on June 10,

11, and 12 at Camp Jackson (later

named Camp Chase), four miles west of

Columbus on the national road.52

With her husband in camp and her initial

burst of enthusiasm fading,

Lucy Hayes began to think about the

loneliness of her situation. In her

first letter to her husband, she said

that she hoped to follow him wherever

he might be stationed, and assured him that

he would find that his "foolish

little trial of a wife was fit to

be a soldier's wife."53 Hayes tried to dispel

her anxieties with frequent letters,

assurances of his affection, and the news

that her brother, Dr. Joseph Webb had

been assigned to the same regi-

ment.54

As soon as possible, arrangements were

made for Lucy, her mother, and

the children to visit in Columbus while

the regiment trained at Camp

Chase. On July 25, 1861, less than a

month after her arrival, Lucy and her

mother watched the Twenty-Third O.V.I.

march up High Street to the

depot and entrain for Clarksburg,

Virginia.55

Lucy tried to be a good soldier's wife,

but, as her husband knew, it

would be contrary to her nature to have

hidden her worries completely.

News that her hero, General Fremont, was

being removed from command

of the Western Department, questions

about the federal policy in regard

to slavery, and discomfort because of

her pregnancy caused Lucy to be

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 41

worried and depressed at times. The

predominant tone, however, of her

letters was optimistic, and doubtless

she was correct in the observation that

she passed for one of the "most

cheerful, happy women."56 Items

about

the children in her letters mentioned

that Birchard was doing very well in

school; Webb, who was being taught at

home, provoked even as he amused

them by his efforts to avoid study; and

little Ruddy was both "the light

and torment of the house."57

Plans were made for Dr. Joseph Webb to

return to Cincinnati early in

December to assist with the birth of the

expected baby. In a letter to Hayes,

he commented that Cincinnati presented

none of the appearances of war

"save the number of Military coats

one meets with; business appears quite

brisk."58 A few weeks later,

December 21, 1861, Dr. Webb attended his

sister when she gave birth to her fourth

son, whom the older boys named

"little Joseph." When the news

reached Hayes, he admitted how worried

he had been. "I love you so

much," he wrote to Lucy, "and I have felt so

anxious about you . . . It is best it

was not a daughter. These are no times

for women."50

After Dr. Webb returned to the

regiment's winter quarters, it was Lieu-

tenant Colonel (promoted in October

1861) Rutherford Hayes's turn to

be away from camp. He arrived in

Cincinnati on February 4, 1862, for a

three week furlough. On a visit to his

mother, who was spending the winter

in Delaware, Hayes recalled the joys of

his childhood there and the mem-

ories of his beloved sister, Fanny

Platt, dead since 1856. Until his marriage,

Fanny had been the most important person

in his life; his confidante, his

favorite correspondent, and the spur to

his ambitions.60 Now Lucy served

these needs, as he tried to explain in a

letter to her. "Old Delaware is gone

. . .Old times come up to me--Sister

Fanny and I trudging down to the

tanyard with our little basket after

kindling--all strange--You are Sister

Fanny to me now, Dearest!"61

There were times during the spring of

1862 when Lucy felt she could

not endure the separation any longer.

"And yet with all my hearts longing,"

she wrote, "I would not call you

home . . ." She wondered if Rutherford

tired of her rambling letters for

"writing is not my forte but loving is . . ."

News of the children occupied much

space; Webb was growing more mis-

chievous every day, Ruddy was a smart

little one, Birch was "doing finely"

in school, "but little Joe--the

dearest liveliest brightest little five months

old chap"62 was

evidently her favorite. She had described him earlier as a

"miniature likeness of Lt. Col.

R.B.H."63

In the middle of August 1862, the

Twenty-Third Regiment was ordered

east to reinforce the Union army near

Washington. The troops in western

Virginia traveled by steamer down the

Kanawha to the Ohio River, then

up to Parkersburg where they changed to

the railroad for the balance of

the journey. The troops enjoyed the

cheers of the civilian population and

the profusion of food offered them as

they disembarked in Meigs County

to march around the shoals of the Ohio

River.64 When Lucy heard how

near her husband had been to

Chillicothe, where she and the children were

visiting, she was bitterly disappointed

not to have seen him.65

42 OHIO HISTORY

Soon after their arrival in Washington,

the Twenty-Third along with a

number of Ohio regiments marched with

General McClellan's army in

pursuit of Confederate forces that were

menacing Baltimore and Washing-

ton. At the Battle of South Mountain on

September 14, 1862, part of the

Antietam campaign, Hayes was painfully

wounded in the left arm. As soon

as conditions permitted, he was taken to

the residence of a Captain Rudy

in Middletown, Maryland, where he was

cared for by Dr. Joseph Webb.66

Tile morning after the battle, Hayes

dictated dispatches concerning his

injury to his wife; his brother-in-law,

William Platt; and his friend John

Herron in Cincinnati. Herron and Platt

received their telegrams but Lucy

Hayes did not. Later it was learned that

the orderly only had enough money

for two messages, and for some reason

the telegrapher selected the ones

addressed to Herron and Platt for

transmission.67

Lucy Hayes's animated account of the

incident of the missing telegram

plus that of a second and misleading

message, and the story of her long and

frustrating search for her wounded

husband became such a favorite with

the family that she was persuaded to

dictate it to a White House sten-

ographer. The original draft, typed

about 1880 in capital characters on

one of the early typewriters, is

preserved among the Hayes papers.68

Believing that his wife knew about his

wound, Hayes sent her a second

telegram, marked Washington, that read,

"I am here, come to me. I shall

not lose my arm." Leaving the three

older boys and the baby, who would

need a wet nurse, with relatives, Lucy

hurriedly took the stage to Colum-

bus where William Platt insisted upon

accompanying her to Washington.

Because of delays, it was a week after

Hayes had been wounded before they

reached the capital.

They were unable to find him at any of

the places in Washington where

he had said he might be, nor could they

secure any information from the

Surgeon General's office. Platt finally

located the original draft of one of

the telegrams on which the word

Middletown had been erased and Wash-

ington substituted. So as soon as possible,

Lucy and her brother-in-law

boarded the cars for Frederick,

Maryland--as far as the train could go.

Lucy remembered that she stood during

most of the hot and dusty three-

hour trip, and that the road-bed was

very rough--"we pitched and tossed

around very much." Dr. Joe Webb,

who had been meeting the train every

evening, was waiting for them at

Frederick, and drove them in the buggy

to Middletown where Hayes greeted Lucy

with the jest, "Well, you thought

you would visit Washington and

Baltimore."

Lucy spent her time looking after her

husband and visiting wounded

soldiers in the local homes and

make-shift hospitals. Two weeks later, her

husband and six or seven wounded men

from the Twenty-Third were

ready to begin the tiresome journey back

to Ohio. On one occasion, when

they had to change trains, Lucy Hayes

finding no seats in the coaches led

the way into the Pullman car where the

fashionable crowd returning from

Saratoga were making themselves

comfortable. Oblivious to the resentful

glances, she helped her "boys"

into the empty seats. When a telegraph

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 43

messenger came through paging Colonel

Hayes, the "society folk" became

interested in the group and offered them

grapes and other delicacies. Lucy

disdainfully declined them. As her

cousin remembered, "Even reminiscent-

ly, years afterward, as she told the

story, she declined them."69

By the end of November 1862, Colonel

Hayes was able to rejoin his

regiment then camped in western

Virginia. The Twenty-Third built a log-

cabin village at Camp Reynolds, on the

Kanawha near Gauley Bridge, and

Hayes's headquarters, a two-room cabin,

was comfortable enough for Lucy

and the older boys to join him.70 The

last of January, Lucy, Webb, and

Birch, arrived at Camp Reynolds after a

somewhat uneventful trip, except

for the ride of the last twenty-eight

miles in an ambulance that Lucy said

was "as muddy and rough as heart

could wish."71 Hayes recorded in his

Diary that mother and sons "rowed skiffs, fished, built

dams, sailed little

ships, played cards and enjoyed camp

life generally."72 Sometimes he wor-

ried because Lucy and her brother, Dr.

Joe, rode farther out from camp

than Hayes considered safe.73

In March, when the regiment was ordered

to Camp White, opposite Charleston, Lucy

and the boys returned to Cin-

cinnati.

A little later Lucy wrote that she was

so relieved to hear that Jenkins'

raiders, who had temporarily occupied

the lower Kanawha area, had been

forced to withdraw that she wanted to

begin her letter to Hayes with the

chorus of "John Brown's Body"

("Glory, glory hallelujah. . . His soul is

marching on") but her husband might

think her "daft." Another cause

for her rejoicing was the victory of the

Union ticket in the recent city

elections in Cincinnati. Referring to

the election of a former army officer,

Lucy said that she did not believe a

soldier should leave his post for office;

thus expressing a sentiment that Hayes

was to make famous later when he

refused to leave the army to canvass for

a seat in Congress.74

In June 1863, Lucy, her four sons, and

her mother journeyed to Camp

White. There were a few happy days

together for the Hayes family before

little Joseph became ill and died on the

twenty-fourth of June. The father

felt that he had known so little of the

baby that he did not "realize a loss;

but his mother and still more his

grandmother, lose their dear companion,

and are very much afflicted."75

In later years, Lucy said that the bitterest

hour of her life was when she stood by

the door of the cottage at Camp

White and watched the steamer with the

"lonely little body" depart for

Cincinnati.76 Her

brother, Dr. James Webb, assisted by friends, buried

the little boy in Spring Grove Cemetery.

Soon after the death of little Joe, Lucy

and the children left for Chilli-

cothe, arriving in time to share the

excitement and apprehension caused

by General John Morgan's raid into Ohio.

She described the panic in

Chillicothe that resulted in the burning

of the Paint Creek bridge when a

false rumor spread that Morgan's men

were approaching the town. Leaving

the condition of the city to her

husband's imagination, she guessed that

since at least 6000 men had rushed to

Chillicothe's defense "a goodly num-

ber of horses" were kept within the

town limits.77

44 OHIO HISTORY

During the winter of 1863-64, Lucy and

Rutherford rented their home

in Cincinnati and settled in a pretty

old house at Camp White. Lucy had

her sewing machine forwarded from

Cincinnati and along with sewing

and mending for the regiment made blue

soldier suits for the boys.78 Mrs.

Hayes was popular with the soldiers, not

only because she sewed for them,

but because she cared for them when they

were ill, mothered them, and

listened to their grievances. The wife

of a surgeon remembered that the

young lieutenant, William McKinley,

later President of the United States,

spent so much time tending the camp fire

that burned brightly before

headquarters every clear evening that

Mrs. Hayes nicknamed him Casa-

bianca (son of a French naval hero at

the battle of the Nile.) 79

Late in April 1864, the Twenty-Third

broke camp for what would be-

come the final campaign of the war. As

the troops marched along the Kana-

wha, Lucy and several of the wives

chartered a small boat on which they

steamed slowly up the river, until the

head of navigation was reached, cheer-

ing and waving to the troops as long as

they could keep pace with them.80

After leaving West Virginia, Lucy and

her family rented rooms in Chilli-

cothe in a "nice" boarding

house with a large play yard and space for a

garden.81 Hayes tried to keep

his wife informed concerning his safety by

telegraphing her after each engagement.

Following such a message, after

a foray into Virginia to destroy tracks

and stations of the East Tennessee

and Virginia Railroad, Lucy wrote that

they were very relieved to hear

from him; Webb talked only of the

"glory of victory" but Birch thought

more of the "desolate homes and

hearts."82

While the regiment was resting between

raids into the Shenandoah Val-

ley, Hayes wrote that the new flag Lucy

had sent was flying before head-

quarters. Somewhat chagrined, she

answered that the flag was not intended

for the officers but was meant to remind

the common soldiers that she was

thinking of them. "I want our

soldiers to know," she said, "that I sent it

to them . . . to let them know how near

they are to me . . ."83 Anxious as

usual to please his wife, Colonel Hayes

arranged to have the flag presented

to the regiment at dress parade.84

In August 1864, Hayes was nominated by

his friends in Cincinnati for

Congress from the second district.

Appreciative of the compliments and

congratulations, Lucy Hayes told Sardis

Birchard, "Of course dear Uncle

it is very gratifying to know how he

[Rutherford] stands with our citizens

and friends--I wonder if all women or

wives have such an unbounded

admiration for their better half."85 Doubtless

Hayes measured up to the

expectations of his wife in the

following answer to a plea that he take time

off from fighting to canvass: "An

officer fit for duty who at this crisis would

abandon his post to electioneer for a

seat in Congress ought to be scalped."86

The voters were sufficiently impressed

by Hayes's integrity of purpose and

war record to elect him to Congress in

October 1864.

With Hayes exposed to constant danger in

the fierce fighting in the

Shenandoah Valley and uncomfortable

because of her impending confine-

ment, the last days of August were a

nightmarish period for Lucy Hayes.

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 45

"I hope it is true," she wrote

"'the darkest hour is just before the day,' may

it be so--all is dark and gloomy."87

But by the next month Lucy was writ-

ing that she felt better. Birch and even

Webb were enjoying school, but

little Rud, visiting with the aunts at

Elmwood, was "positive" that he was

too young to go to school every day.

Recently, Rud had expressed the wish

that his "papa would get a little wounded--then

he would come home

again--and we would keep im."88

In one of his letters that discussed the

coming election, Hayes told Lucy

that although he preferred to see

Lincoln reelected he felt no apprehension

that a victory by George McClellan would

cause the war to be abandoned.

Evidently Lucy had mentioned that Webb

was shouting the same invec-

tives against McClellan as he had

against Vallandigham the previous year--

"Hurrah for Vallandigham . . . and

a rope to hang him"--because Hayes

asked Lucy to teach his boys to think

and talk well of General McClellan.89

While Rutherford Hayes was camped near

Harrisonburg, Virginia, a

fifth son, George Crook, was born to

Lucy, September 29, 1864. When she

was able to write, Lucy described the

baby as a "fine large child . . . We

have given Uncle Scott [Cook] the title

of Grandfather."90 About the same

time that this letter was posted,

Cincinnati papers carried the news that

Rutherford Hayes had been killed in the

battle of Cedar Creek, an en-

gagement immortalized by the poet's

description of Sheridan's ride. Soon

after the delivery of the paper, which

Uncle Scott purposely put aside, a

telegraph boy arrived with this message

for Lucy: "The report that your

husband was killed this morning is

untrue."91

Following the battle of Cedar Creek,

which ended the main campaign

in the Valley, General Sheridan approved

a recommendation that Hayes

be promoted to Brigadier-General.92

General Crook, Hayes's commander,

was so pleased that he presented him

with a pair of his shoulder straps;

the stars as Hayes described them were

"somewhat dimmed with hard

service."93 Lucy

answered that she would be glad to see him "with the old

star on your shoulder even though it is

dimmed."94

In common with much of the nation, Lucy

Hayes's joy in the fall of Rich-

mond and the surrender of Lee's army at

Appomattox Court House quickly

turned to sorrow with the assassination

of President Lincoln on April 14.

She began her letter, "From such

great joy how soon we were filled with

sorrow and grief past utterance."

Then continuing in her own words, she

declared, "I am sick of this

endless talk of Forgiveness . . . Justice and

Mercy should go together--Now don't say

to me Ruddy that I ought not

to write so."95

In May 1865, Hayes sent in his

resignation from the army and with Lucy

journeyed to Washington to see the Grand

Review of the Army. On May

23 and 24 they watched from the

congressional stand as the Union legions

marched in review along Pennsylvania

Avenue.

Directly opposite was the reviewing

stand with President Johnson, mem-

bers of the cabinet, and General Grant.

Lucy wrote in a letter to her mother

that she borrowed Hayes's field glasses

to watch the President, "earnestly

and often," and that she could not

help but feel confidence in such a "fine

46 OHIO HISTORY

noble looking man who impresses you with

the feeling of honesty and sin-

cerity." She observed that General

Grant appeared "noble" and "unas-

suming" and that his two little

boys were leaning on him with "all fond-

ness and love." She was thrilled as

she watched the cavalry that had fought

"so splendidly" in the Valley

and around Richmond but sorry that their

brave leader, General Sheridan, was not

with them. She hoped that foreign

ministers watching the parade would be

impressed by the power and

might of the United States.96 These

lines concluding her description of

the Grand Review briefly and eloquently

expressed her appraisal of the

victory:

While my heart was filled with joy at

the thought of our mighty

country--its victorious noble army--the

sad thought of thousands who

would never gladden home with their

presence made the joyful scene

mingled with so much sadness that I

could not shake it off.97

From a vantage point similar to the

congressional stand in Washington,

Lucy Hayes had viewed the vast panorama

of the Civil War for four long

years. When not living in army camps in

West Virginia, she had followed

the movements of the troops through

accounts in the newspapers and an

exchange of letters with her husband,

brothers, and cousins. While her

husband had carried out his role as a

soldier with efficiency and bravery,

Lucy and her family had faced the

problems of civilian life with courage

and ingenuity.

Following the difficult years of the

Civil War, the Hayes family might

have moved into a comfortable home in

Cincinnati or Fremont and settled

down to a well regulated and satisfying

existence. Instead, for the next

sixteen years, beginning with his

unexpired congressional term, the politi-

cal offices Hayes held would determine

whether the Hayes caravan would

establish headquarters in Cincinnati,

Columbus, Fremont, or Washington.

In January, Hayes persuaded Lucy to

leave the children with her mother

in Cincinnati and visit him in the

capital. Lucy wrote from Washington

that she was having a delightful time,

"in a quiet way." Her greatest pleas-

ures were connected with "the

Capitol, the Library and Garden." On one

occasion the Superintendent of the

Gardens had sent her a beautiful basket

of japonicas in appreciation of her

interest. Every afternoon that Congress

was in session she listened from the

gallery to the discussions of the prob-

lems of the day, and occasionally in the

evening they attended social func-

tions.98 At General Grant's reception

they purposely had been the first to

go through the receiving line so that

they could watch the arrival of the

other guests.99

On her return to Cincinnati, Lucy wrote

her husband that he could

not imagine how lonely she was without

him, and how much she missed

being able to talk politics with him. It

seemed to her that if "A[ndrew]

J[ohnson]" had the nerve to veto

another congressional act, it would "pitch

him clear from the Bosom of his family

[Republican party]."100 Other items

in her letters concerned the children:

Birch and Webb's efforts to learn

German, Rud's feeling at being left out

of the close comradeship between

the two older boys, and her love for

little George.101

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 47

The year following the Civil War was a

sad one for the Hayes family.

In the spring of 1866, scarlet fever

spread through the family with George

the most seriously affected. Maria Webb

and Lucy nursed him tenderly,

but after several brief rallies he died

on May 24, at the age of twenty

months.102 The excessive heat

of the summer, added to Maria Webb's grief

at the loss of her little favorite, was

more than her asthmatic heart could

stand. While staying with her sister at

Elmwood, she became seriously ill.

Lucy was able to go to her mother and to

sing "by the hour" the hymns

that seemed to comfort her. At length on

September 14, 1866, following a

request to have Lucy sing, "Rock of

Ages," Maria Webb was dead.103 A

few weeks after Hayes's reelection to

Congress and while he was on an ex-

cursion to the West, Sophia Hayes also

became ill and died on October 30,

1866.104

Thus passed from the scene two

remarkable pioneer women. Maria Webb

in her gentle, cheerful way had achieved

her goals: education, position,

and happiness for her children. Sophia

Hayes, a sturdy, self-sufficient, and

practical woman, but with the same

goals, could be proud of her son, satis-

fied with her daughter-in-law, and

hopeful for her grandchildren. Lucy

Hayes was so overcome with grief that it

was weeks before she could even

write to Birch and Webb visiting Uncle

Sardis in Fremont. She hinted

that Uncle Joseph Webb, who had returned

from medical study in Europe

shortly after his mother's death, had a

secret for them.105 When Birch

learned that his adored uncle was about

to marry Annie Matthews of Cin-

cinnati, a sister of Judge Stanley

Matthews, he wrote to him, "As to Mat-

rimony I do not know what to say but

Webb is quite jealous."106

In 1867, the Union Republican party

nominated Rutherford B. Hayes

for governor. Soon after the nomination,

Hayes decided that it would be

educational for Birch and Webb to

accompany him to Washington for

what might be his last appearance in

national halls.107 He told Lucy that

the boys made friends easily on the

train and in the House crowded close

to hear Thaddeus Stevens whenever he

rose to orate.108

While Hayes campaigned for the

governorship, Lucy waited for the birth

of their sixth baby; on September 2,

1867, the longed for baby girl was

born. This time there was none of the

hesitation that had characterized

the naming of the boys for almost

immediately the baby was christened

Fanny after Rutherford's sister. Hayes's

schedule of campaign speeches

barely permitted him to be with his wife

when the baby arrived, but for-

tunately Dr. Joseph Webb had returned

from his honeymoon in Europe

in time to assist with the delivery.109

Hayes won the election by a small

majority, and as soon as possible the

family moved into a rented house at 51

East State Street, Columbus.110

Lucy found happiness and satisfaction in

her role as governor's wife, par-

ticularly in efforts to establish a

soldiers' orphans' home. The Grand Army

of the Republic, having failed to get

the Ohio legislature to support their

plan, decided to start a home by

voluntary contributions in the hope that

the state would take it over. With the

help of Lucy Hayes and others,

money was raised to buy a tract of land

near Xenia.111 Lucy felt it neces-

48 OHIO HISTORY

sary, however, to refuse when one of the

principal promoters asked her to

be a member of the board because, as she

expressed it, "Just now on the

eve of a bitter contest [election of

1869] my name being mentioned might

occasion some remarks from the enemies

of the movement."112

Following Hayes's reelection in 1869,

the family moved from the East

State Street house to the nearby

residence of Judge Noah Swayne on Sev-

enth Street. Hayes described it as a

fine, large house with ample grounds

that rented for the modest sum of

$800.00 a year.113 An example of the

hospitality of the Hayes family is an

invitation to a Fremont friend to

visit them. Since the Reverend Mr.

Bushnell would be arriving after the

household had retired, Hayes told him to

look for the key under the mat,

and instructed him where to find his

room.114 Although it was the custom

to leave the house key under the mat,

their chickens were not safe from

marauders. Lucy wrote that after nine of

their nice chickens were carried

off, she had "the Carriage house

transformed into a big Coop and a good

lock."115

Little Fanny was the "darling"

of the family, particularly of her father.

It pleased him to see her watching from

the window as he walked across

the street to the State House.

"Fanny has a strong clear voice," he wrote,

"I can hear her call to me 'by-by'

from the parlor window as I enter the

door of the State House."116 In

February 1871, Fanny was happy when a

"little boy sister" was added

to the household. Scott Russell, named after

two branches of the family, was a

healthy good-natured baby.117

In bestowing attention on their

"second family" Rutherford and Lucy

Hayes did not neglect the three older

boys. On one occasion, Hayes wrote

that Rud "learns well, is forward,

and fond of wit and company."118 Dur-

ing the winter, Webb and Birchard Hayes

remained in Fremont where

they attended school, but they spent the

summers and vacation periods

with their parents in Columbus or

relatives in the Chillicothe area. Webb

particularly liked the farm homes of his

uncles and aunts. Hayes described

him in his Diary as a

"handsome, cheery, bright boy." At the same time,

he commented that Birch was a "fine

looking boy of noble character. A

deafness, slight, but noticeable is the

greatest drawback which I can see

for his future career."119

To alleviate the deafness, Birch had a

"polypus" removed from his ear

during the summer of 1869 in Cincinnati.

While in the city for post-opera-

tive treatments, he had an opportunity

to watch his favorite sport, a base-

ball game between the Eckfords

(Greenpoint, New York) and the Cincin-

nati Red Stockings.120 Later,

as Birch was nearing graduation from college,

he wrote, "I am inclined to think

that one reason for my dread of life after

leaving College is because I will be

unable to play ball."121

Rutherford Hayes often expressed his

happiness and content with Lucy.

As he approached his forty-eighth

birthday in 1870, he wrote, "My life

with you has been so happy--so

successful, so beyond reasonable anticipa-

tion that I think of you with a loving

gratitude that I do not know how

to express."122

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 49

Hayes did not run for a third term as

governor in 1871. The family lived

in rented rooms in Cincinnati until the

spring of 1873, when they moved

to Fremont and the house in Spiegel

Grove which Sardis Birchard had

built with them in mind. There on August

1, 1873, the eighth and last of

the Hayes children, another boy, was

born.123 The parents were soon de-

scribing the baby, who had been named

Manning Force after his father's

friend, General Force, as the

"sweetest" and "brightest" baby ever.124 Like

his two brothers of the war years,

little Manning did not survive his second

summer and before he was thirteen months

old died from what his father

described as "summer

complaint."125

Six months later the death of Sardis

Birchard further saddened the Hayes

family, as well as placing heavy

responsibilities on Hayes as executor of

the estate. In spite of financial

problems, Rutherford and Lucy Hayes were

soon absorbed in improving the house and

grounds in Spiegel Grove. Lucy

in a letter to her sons, Birch and Webb,

who were attending Cornell Uni-

versity, expressed her pleasure in the

thought of a permanent home. "You

do not know and indeed cannot imagine,"

she wrote, "what comfort and

happiness is found in Spiegel Grove and

the great pleasure in helping to

prepare our home."126

Although pleased with their life in

Fremont, Hayes succumbed to the

pleas of Ohio Republican leaders to run

for an unprecedented third term

as governor in 1875. His decision may

have been influenced again by Lucy's

interest in politics and the pride she

had always felt in his political achieve-

ments. Lucy had explained this interest

earlier in a letter to Birchard,

"Your ignorance of politics is not

a grave offense--you could not expect

to know and enjoy politics as she does

[I do]."127

Rutherford Hayes's victory on election

day almost automatically meant

that he would be considered for the

presidency in 1876. Rather fallaciously

Lucy Hayes assured her husband that she

had not been bitten by the

"Mania" [move to nominate

Hayes for the presidency], but she was "so

happy so proud to be your

wife."128 Their cook, Winnie Monroe, did not

try to conceal her hope that her

employer would become President. In

describing their Thanksgiving dinner in

1875, Lucy wrote, "Winnie as

you know would be in her element--and as

she is looking to the Top of

the Ladder--a little extra effort is the

consequence."129

Two months after his inauguration as governor,

the Hayes family again

moved to Columbus; this time they rented

a house at 60 East Broad Street.

Lucy wrote that the house was not large

enough to entertain "Legislative

bodies"; there was no yard for the

children but the grounds of the State

House, directly opposite, provided some

play space, and anyway, Scott's

chief sport was riding his velocipede on

the pavement. Fanny recited her

lessons with her cousins, and enjoyed

attending dancing school. Webb

Hayes was looking after the affairs in

Fremont, and young Rud was en-

rolled in the agricultural college at

Lansing, Michigan.130

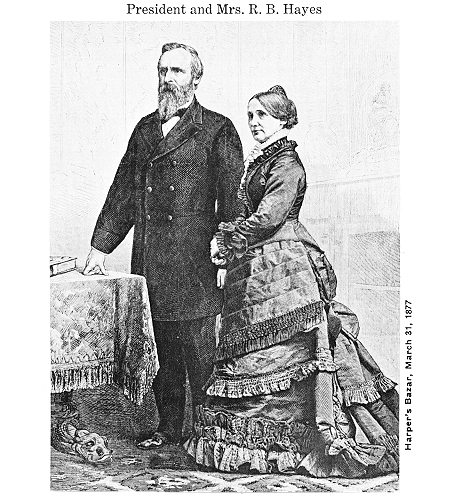

Rutherford Hayes was nominated for

President by the Republican con-

vention that met in Cincinnati in June

1876. The campaign was very dif-

ferent from the others in which Hayes

had participated because custom

50 OHIO HISTORY

decreed that the presidential nominee

should allow others to do the talk-

ing for him. Also for the first time

since Hayes had entered politics, Lucy

became a prime subject for newspaper

stories. The Columbus correspon-

dent for the New York Herald wrote,

"Mrs. Hayes is a most attractive and

lovable woman . . . For the mother of so

many children she is singularly

youthful in appearance."131

The presidential election of 1876 was

not a clear-cut victory for either

Rutherford B. Hayes or Samuel J. Tilden

and had to be decided by a

special electoral commission authorized

by Congress. This was a difficult

period for the Hayes family and Lucy's

friends wondered how she could

endure "sitting on the ragged

edge."132 Lucy's sense of humor did not

desert her as shown by this excerpt from

a letter to Birchard:

Your father and I are becoming more and

more attached to each

other--as time passes and the great

Lawsuit is in progress "I will never

desert Mr. Micawber"--and I will

remain loyal to my principles and

the "Republican Party"--so

dear boy you should be satisfied with re-

gard to your Mother's declaration of

principles.133

On March 1, 1877, before the last

electoral votes had been counted, the

Hayes caravan that included Mr. and Mrs.

Hayes; their children, Webb,

Scott, and Fanny; his niece, Laura

Mitchell; and a group of friends and

political associates left for

Washington. About dawn the next day, the

party was awakened near Harrisburg to

receive the news that Congress had

declared Hayes duly elected President of

the United States. Rutherford B.

Hayes as President-elect and Lucy Hayes,

soon to become First Lady of

the land, smiled happily as they

listened to the cheers of the crowd that

had gathered to welcome them.134

Long years as a public official's wife,

well educated for her time -- the

first wife of a President to have earned

a college degree -- and a sincere

interest in the welfare of people helped

to prepare Lucy Hayes for her

position as First Lady. In addition to

her duties as mistress of the White

House, she supervised the education of

her two young children, was the

adviser and confidante of her three older

boys, and, as she had been for

twenty-five years, the loved and

respected wife of Rutherford B. Hayes.

Lucy accepted her role as hostess of the

White House from the begin-

ning -- surprisingly, of the eighteen

Presidents who had preceded Hayes,

only eight had wives who were able to

assume for the full term the social

responsibilities of their position.135

Lucy also went out of her way to be

cordial toward the "ladies of the

press" as evidenced by their favorable

treatment of her. Mary Clemmer, in

particular, a well known reporter and

author of "A Woman's Letter from

Washington" that appeared periodical-

ly in The Independent, was

pleased with Mrs. Hayes, although she occa-

sionally criticized the President's

policies.

Observing Lucy during the inaugural

ceremony, Mary Clemmer wrote:

Meanwhile, on this man of whom everyone

in the nation is this mo-

ment thinking, a fair woman between two

little children looks down.

She has a singularly gentle and winning

face. It looks out from bands

|

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 51 of smooth dark hair with that tender light in the eyes which we have come to associate always with the Madonna. I have never seen such a face reign in the White House. I wonder what the world of Vanity Fair will do with it. Will it frizz that hair? powder that face? draw those sweet, fine lines awry with pride? bare those shoulders? . . . .136 Much to the relief of the White House staff, Lucy and Rutherford Hayes made few changes in personnel. The doorkeepers and ushers employed by Grant, most of whom were former soldiers, were retained. William T. Crump, who had been Hayes's orderly in the army, was installed as steward, and their family cook, Winnie Monroe, reached the "top of the ladder" when the White House kitchen became her domain. The correspondent for the Cleveland Plain Dealer noticed that the employees "are now all smiles and politeness whereas under the old regime they were rather surly and disobliging."137 In the spring of 1877, the President's family at the White House con- sisted of twenty-one year old Webb Hayes who served as an assistant-secre- tary to his father, six year old Scott, and Fanny who was nearly ten. Ruth- erford Platt Hayes, almost nineteen, was a student at Cornell, and Birchard, twenty-four, was attending Harvard Law School. Emily Platt, Rutherford's niece from Columbus, spent much of her time at the White House until her marriage in 1878. Since it was not the custom for a President's wife to have a staff of social assistants, Lucy Hayes made up for her lack of grown daughters by inviting nieces, cousins, and friends to visit the White House and to serve as hostesses and secretaries.138 |

|

|

52 OHIO HISTORY

Lucy seemed to manage her family and

domestic cares smoothly but

with kindness and affection. It is

doubtful if Lucy and Rutherford Hayes

set out, as Eckenrode suggested, to

follow the example of Victoria and Al-

bert in England to become "revered

religious parents of the nation."139

It was not in character for Lucy to plan

such an austere, deliberate, and

extended course of action. As Hayes had

noted in the days of their

courtship, "Intellect, she has too,

a quick spritely one, rather than a re-

flective profound one . . . She is a

genuine woman, right from instinct and

impulse rather than judgment and

reflection."140

Life in the White House soon settled

into a pleasant routine. After

breakfast at 8:30 and a walk through the

conservatories, the family and

guests gathered in the library where a

chapter from the Bible was read,

and then all repeated the Lord's Prayer.

By this time, the flowers had been

brought in from the conservatories, and

with the help and direction of

Mrs. Hayes they were arranged for the

White House. Other bouquets were

sent to friends and the Washington hospitals,

particularly to the children's

hospital. The rest of the morning Lucy

Hayes was busy receiving calls and

taking visiting friends and relatives on

tours of the city.141

The State Department and White House

staff knowing that liquor had

not been served in the Hayes household

in Ohio waited to see what the

policy would be in regard to formal

entertaining.142 Doubtless Winnie

Monroe had told them that Sardis

Birchard had been reputed to have had

a "fine cellar,"143 and that

Mrs. Hayes had helped her mother secure the

wine she had seemed to need for her

health.144 Politicians remembered that

Hayes sometimes had a

"schoppen" of beer when he visited in Cincinnati,145

and army friends could recall promotions

celebrated with spirits.146

At the first official dinner, April 19,

1877, given in honor of the Russian

Grand Duke Alexis and his companion,

Grand Duke Constantine, a "full

quota" of wine was served, but soon

after this Hayes made it known that

no alcoholic beverages would be served at

future affairs.147 The decision

must have been a joint resolution on the

part of Lucy and Rutherford

Hayes since that was the way they solved

all such problems. Many factors

probably entered into the decision: a

wish to set a good example, Lucy's

lifetime abstinence from liquor, a

desire to keep the temperance advocates

in the Republican ranks rather than have

them join the Prohibition Party,

and Hayes's firm conviction that

government officials should conduct them-

selves at all times with dignity and propriety.148

Hayes recorded in his

Diary that at several embassy receptions "disgraceful

things were done by

young men made reckless by too much

wine."149

During the summer, the Hayes family

sometimes left the heat and for-

mality of the White House for a cottage

on the shaded, rolling grounds of

the National Soldiers' Home on the

outskirts of the city.150 Also Hayes, ac-

companied by his wife and other members

of the family, traveled about tile

country seeking support from the people

for his policies.151

Every Thanksgiving Day, the White House

secretaries and clerks along

with their families were invited to

share the Hayes family dinner; and on

Christmas Day, the staff again gathered

at the White House where Mrs.

|

Hayes had a present for every one, which if possible she had purchased herself. Colonel XV. H. Crook, an executive clerk, wrote that Fanny and Scott distributed the presents, and "it was a real Christmas that came to the White House in those days."152 The first year ended with festivities that marked a highlight in the life of Lucy and Rutherford Hayes. Friends and relatives, many of whom had attended their wedding in 1852, gathered at the White House on Decem- ber 30, 1877, for their silver wedding anniversary. Lucy, wearing her orig- inal bridal gown -- extended at the seams -- and attended again by Laura Platt Mitchell, renewed her vows with her husband before Dr. L. D. Mc- Cabe who had performed the original ceremony. A fitting climax was a grand public reception the next evening with the Marine Band filling the house with music, and the conservatory "ablaze" with gas jets. Friends believed that no other social event of their "official lives" was quite so satisfying to the First Family as the observance of their silver wedding anniversary.153 The public was also intrigued by the Sunday evening musical soirees that the Hayes family instituted at the White House. Vivid word pictures remain of Lucy sitting at a Chickering square piano while the guests sang hymns that began "A few more years shall roll" or "There is a land of pure delight/ Where saints immortal stand."154 Sometimes it was Carl Schurz, called an "infidel and atheist" by Grant, who played such favorites as "Jesus Lover of My Soul," and "Blest Be the Tie that Binds."155 Schurz, whose wife had died prior to his appointment as Secretary of the Interior, lunched so frequently at the White House that he wondered if people would think he boarded there.156 Mrs. Hayes's hospitality strained the capacity of the White House. The family apartment on the second floor consisted of six or seven bedrooms and one sitting room. The office of the President and the Cabinet Room were also on the second floor and used the same corridors as did the fam- |

54 OHIO HISTORY

ily. During the Hayes administration the

old copper tubs were eliminated

and bathrooms with running water were

added.157 Another improvement

was the installation of a crude wall

telephone that was of little practical

use because of the few telephones in

Washington.158 Rud Hayes said that

when he and Birch came home from

college, they seldom had a bedroom

or even a bed to themselves. They might be

assigned a cot in the hall, a

couch in a reception room, or even a

bathtub as a "resting place."159

In spite of cramped living quarters,

Lucy was charmed with the White

House, not only because of the lovely

reception rooms, but also because

of the Mansion's association with the

history of the nation. It had been

customary when a new administration came

into office to appropriate

money to repair and redecorate the White

House. After eight years of the

Grant administration much renovating was

necessary, but because of

strained relations between Hayes and

Congress the appropriation was de-

layed.160 Holes in the carpet

and curtains were covered as much as possible

by reversing the ends of curtains and

covering worn spots with furni-

ture.161 The First Lady ransacked the

cellar and attic to find furniture

that could be restored. Crook said,

"Many really good things owed their

preservation to this energetic

lady."162

When Congress finally appropriated money

for repairs and remodeling,

Lucy preferred to enlarge the

conservatories rather than to undertake ex-

tensive redecorating that might not

please the next occupants. The billiard

room, which connected the house with the

conservatories, was converted

into a greenhouse and the table was

moved to the basement. Long closed

windows were opened so that the guests

in the State Dining Room could

look into the plant room.163 Being

very much interested in the movement

to complete the Washington Monument that

particularly involved strength-

ening the foundation, Lucy had gas posts

installed on the White House

grounds looking toward the monument.164

Nearly every night was reception night

for Lucy Hayes, and when her

husband was not too occupied with State

business he came down to join the

group around his wife. One such occasion

favorably impressed a young

graduate student, John F. Jameson, later

to gain fame as a historian and

archivist. Jameson and a friend called

on President Hayes with a letter of

introduction. After talking to the young

men, Hayes introduced them to

Mrs. Hayes who was chatting with a

friend in the Red Room. Describing

the evening to his mother, Jameson

wrote, "I had the chair next to Mrs.

Hayes . . . I thought Mrs. Hayes very

pleasant . . ." Later one of the Hayes

sons (probably Rud) took the students on

a tour of the state rooms. "The

son seemed a pleasant, off-hand sort of

fellow," Jameson continued, "and

the whole concern didn't sling nearly as

much style as I expected . . . We

had a very pleasant time."165

One of the infrequent weddings in the

White House was held during the

Hayes administration. On June 19, 1878,

Emily Platt, Hayes's niece and a

secretary and companion to Lucy, married

General Russell Hastings, a close

friend of the family who had served on

Hayes's staff during the Civil War.

|

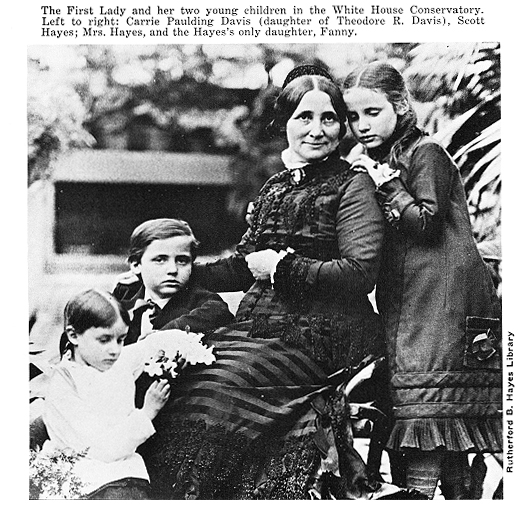

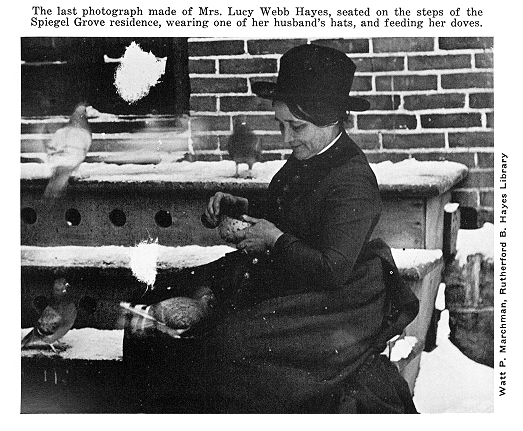

LUCY WEBB HAYES and Her Family 55 The press described the wedding in detail including a description of the wedding bell that was estimated to contain 15,000 roses.166 Many requests for assistance and positions were included in the multitude of letters that Lucy Hayes received.167 Occasionally she could not resist some of the more worthy applicants whose pleas had been sorted out by her volunteer secretaries.168 It also would have been contrary to her nature not to have tried to help the poor and needy of the District. The doorkeeper, Thomas Pendel, remembered being called upstairs often to be told by Mrs. Hayes to take money and a note to some destitute family.169 Lucy Hayes may have appreciated the desire of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union to have a portrait of her painted for the White House, but a nationwide request for contributions of ten cents or more to pay for the picture annoyed her as indicated by her note to Birchard that contained this phrase: "Only worth ten cents."170 Eventually a life-size portrait of Lucy Hayes was painted by Daniel Huntington, a noted artist of the time. Lucy wearing a lovely dark red dress with an ample train and lace ruching at the neck and sleeves was posed against a formal landscape. The presenta- tion to the White House was delayed until March 8, 1881, after the in- auguration of President Garfield.171 A composition more representative of Lucy's personality was a group photograph of Mrs. Hayes, Fanny, Scott, and a friend taken in the White House Conservatory. The appeal of her character is revealed in the midst of the flowers she loved and surrounded by the affection of the children.172 |

56 OHIO HISTORY

An attractive addition to the White

House china was an exquisite state

dinner service executed by Haviland

& Company from designs by the Amer-

ican artist, Theodore Davis. Among the

many interesting "flora and fauna"

patterns included in the set was one

called "Floating for Deer." In the

summer when the deer sought relief from

insects in shallow lake waters

hunters stalked them at night in small boats.

A lighted candle placed in the

front attracted the animal while a birch

bark reflector enabled the hunter

to remain invisible. This particular

scene shows a deer hypnotized into im-

mobility by the approaching light.173

The nineteenth century remembered Lucy

Hayes as a successful hostess.

Julia Bundy Foraker wrote, "Yet the

Cave Dwellers, those old Washington-