Ohio History Journal

Samuel A. Hudson's Panorama

Of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers

By JOSEPH EARL ARRINGTON*

John Banvard and John Rowson Smith were

the pioneers in

applying the panoramic art form of

enlarged and continuous views

to the western river system.1 Samuel A.

Hudson followed close be-

hind them with his panorama of the Ohio

and Mississippi rivers, the

first to picture the majestic Ohio. He

had earlier created such a

panorama of the Hudson River,2 and

later was to make one of the

Gold Regions in California.3

The story of this artist has remained

unknown, though he came

from an old and prominent New England

family. Samuel Adams

Hudson was born February 13, 1813, at

Brimfield, Massachusetts,

the son of Samuel Hitchcock and Miriam

(Adams) Hitchcock.4

In 1823, when Samuel was ten years old,

his father died, leaving a

family of eleven children. This son and

two of his younger brothers,

William H. and George H., chose

tailoring as their occupation,

adopted "Hudson" as their new

family name (in 1836, at Sturbridge,

Massachusetts),5 and became interested in art as a

congenial

* Joseph Earl Arrington of New York City is the author of other articles

on

Mississippi River panoramists, among

them Leon D. Pomerede and Samuel B.

Stockwell.

He wishes to thank the many persons

along the two rivers and along the exhibition

routes of the panorama who generously

cooperated in furnishing the information

which made this article possible.

1 See John Francis McDermott, "News

Reel--Old Style, or Four Miles of Canvas,"

Antiques, XLIV (1943), 10-13; Boston Evening Transcript, September

12, 1839.

2 Hanington's Dioramas, a playbill dated Worcester, Massachusetts, June 25,

1851.

Copy in the library of the American

Antiquarian Society, Worcester.

3 Boston Mail, April

4, 1849; Boston Journal, April 7, 1849.

4 Mrs.

Edward Hitchcock, comp., The Genealogy of the Hitchcock Family

(Amherst, Mass., 1894), 292.

5 Secretary of the Commonwealth of

Massachusetts, List of Persons Whose Names

Have Been Changed in Massachusetts, 1780-1892 (Boston, 1893), 79; Vital Records of

Sturbridge, Mass. to the Year 1850 (Boston, 1906), 218.

?? JOSEPH

EARL ARRINGTON 1957

356

THE OHIO HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

avocation. Then, in 1838, Samuel,

having native ability and a special

talent for painting, made plans for the

creation of the huge pan-

oramas that were to become an absorbing

interest for a dozen years.6

He located at Boston in 1840 to follow

his occupation of merchant

tailor,7 but was mostly away

from the city from 1847 to 1852,

while painting and exhibiting his

panoramas. During the latter

two years when the creation and

exhibition of his large art projects

were drawing to a close, he and his

brother William were partners

in a tailoring business at Worcester,

Massachusetts.8 Samuel then

continued his regular work in Boston

from 1852 to 1875. Later

he took a trip westward to Springfield,

Illinois,9 where he died of

dropsy on February 19, 1877,10 leaving

his widow, Eliza Jane

(Goodwin) Hudson, and an only child,

Mrs. Mary Adele Gilbert.

His descendants continued to live in

the Boston area,"11 and honored

this ancestor by hanging three large

portraits of him in their homes.

Hudson's avocation was rewarding, for

we find records of a

number of his landscapes in addition to

the panoramas. An oil

painting, "Hanging Hills of

Meriden, Connecticut," painted

probably in the 1830's, is still

extant. It is a view overlooking

Farmington Valley, and is signed S. A.

Hudson.12 A second large

landscape, without signature but

credited to Hudson, and painted

probably in the 1840's, shows a distant

view down the "Hudson

River from Stony Point."13 Hudson

entered four landscapes in an

exhibition at Worcester in 1849. They

were listed only as "paintings

from interesting points of view."

Again in 1851 he placed two large

landscapes on view at the same place,

one of "Newburgh, New

York" and the other of the

"Lower Highlands of the Hudson

6 Providence (R.

I.) General Advertiser, September 30, 1848.

7 John H. A. Frost and Charles Stimpson,

Jr., pub., The Boston Directory (Boston

1840-75).

8 Henry J. Howland, The Worcester

Almanac, Directory, and Business Advertiser

(Worcester, 1850-51).

9 John Bigelow to Samuel A. Hudson,

Springfield, Ill., April 31, 1876. Copy in

the possession of Percival Gilbert, Sr.,

Boston.

10 Illinois State Journal (Springfield), February 20, 1877.

11 New England Historic and

Genealogical Register, LXXXIII (1929),

339-340;

Percival Gilbert, Jr., to the author,

August 2, 26, 1955.

12 It was reproduced in Harry S.

Newman's periodical, Panorama, in October 1947.

As late as 1953 the picture was in Mr.

Newman's Old Print Shop in New York

City. Letter to the author, April 30,

1953.

13 In 1953 it was owned by Albert Duveen of New York. Letter to the author,

March 10, 1953.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 359

River." The exhibitors

characterized both entries as specimens of

"a style of painting well adapted

to extensive views."14

Hudson's main contributions to the art

of the period were his

panoramas. These monuments are either

not extant or not available

today for direct study, but the main

facts about the creation, subject

matter, and exhibition of the Ohio and

Mississippi rivers painting

are discoverable in existing records.

There are three guide books

and two playbills in which the artist

describes his work,15 and

numerous press advertisements and

editorial comments about the

traveling exhibition. The artist started

his project "with the pros-

pect of producing the FIRST and largest

painting of the kind in the

world."16 The ambitious young man went on the spot to make the

first sketches when only twenty-five

years old, and it required ten

years of struggle and sacrifice to

complete the difficult undertak-

ing.17 He traveled up and

down the rivers four times to make all the

sketches and drawings for it, and then,

with a deep passion for

accuracy of representation, he

"transferred to the canvas, things as

God and man has shaped them."18 The

actual painting was done

in Louisville, Kentucky, the same city

where Banvard had set up

his studio. A local editor made known

the fact early in 1848 that

"this splendid production of the

ready and gifted Hudson has

been executed in this city. We have been

admitted to his painting

gallery during its progress, and have

watched its advancement with

14 Report of the Second Exhibition of Worcester County Mechanics'

Association

(Worcester, 1849), 27; Report of the

Third Exhibition . . . (Worcester, 1851), 34.

These canvases passed from an antique

shop in Worcester to a New York art

dealer in 1931, but their present

location is unknown. Clarence S. Brigham, director

of the American Antiquarian Society, to

A. O. Vietor, April 14, June 8, 1943. See also

the Hudson file in the Frick Art

Reference Library in New York City.

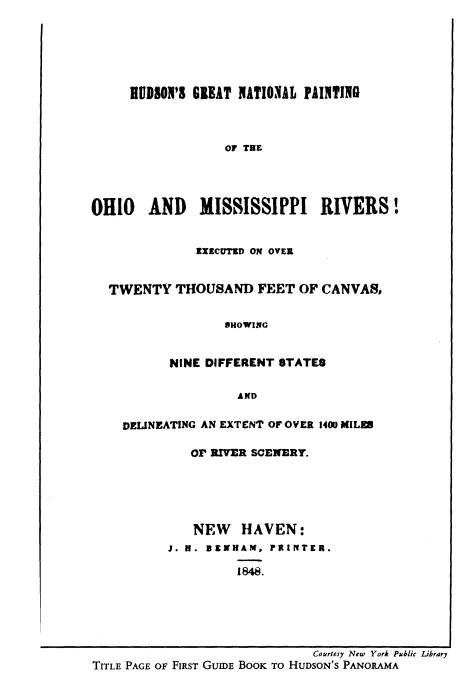

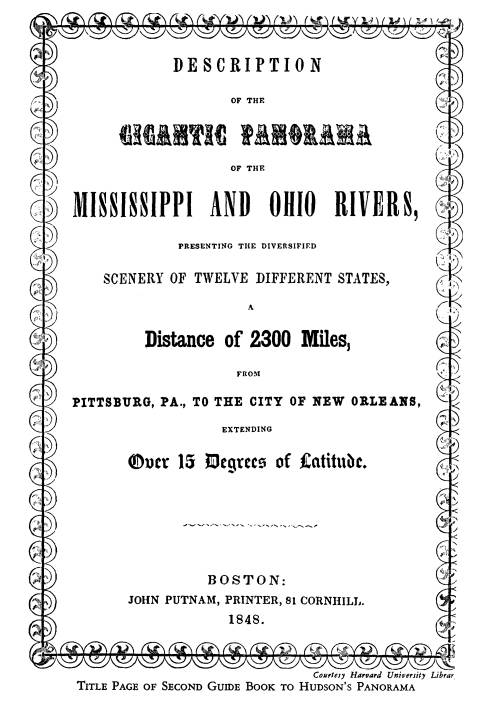

15 The guide books are: Hudson's Great National Painting of the Ohio and

Mississippi Rivers (New Haven, 1848), Gigantic Panorama of the Mississippi and

Ohio Rivers (Boston, 1848), and Geo. W. Cassidy's bewegliches

Riesen-Cylorama

des Mississippi und Ohioflusses (Leipzig, 1850). Copies of the first and third are

in the New York Public Library; a copy

of the second is in the Harvard University

Library.

The playbills are: Hudson's Mammoth

Panorama of the Ohio & Mississippi

Rivers, for

performances at Franklin Hall, Providence, Rhode Island, and The Mam-

moth Panorama of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, for performances at Hampden

Hall, Springfield, Massachusetts. A copy of the first

is at the Rhode Island Historical

Society, Providence; the second appears in the Springfield

Republican, March 17, 1849.

The guide books and playbills will be

cited hereafter by their place of publication.

16 New Haven guide book, Preface.

17 Troy (N. Y.) Post, April 20, 1849.

18 Cincinnati Commercial, April 14, 1848.

360

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

wonder and delight."19 To

him it was as true to nature, "as if re-

flected through a camera obscura."20

We know something of the artist's

technique and have appraisals

of his work from editorial opinion. The

scenes were not coarse

affairs, but were "put upon canvas

with a masterly hand," and "in

a bold and effective manner,"

using "vivid and distinct colors" to

bring out the subjects. Many points of

interest were given special

charm, "by the introduction of

highly artistic effects." These effects,

however, did not obscure the essential

details, for there was "a clear

and distinct view of every

object," as "seen under the most favorable

circumstances." In the town views,

"the buildings and streets are

not run into a confused mass," but

all parts were visible. Water

in the rivers was not static, but it

appeared to be in actual flow.

The drawing was skillful, "in

preserving proportions, and managing

light and shadow," and there was

"excellent judgement in colors

and the general effect produced by

artificial light." Whether viewed

from a distance or close up it was

"a highly finished picture

throughout." The scenes were

continuous and related as a whole,

yet many of them formed "admirable

pictures of themselves alone."

The final product was generally

considered to be one of "rare

excellence" and a credit to the

artist who created it by his "industry

and genius, through long years of toil

and study," with heavy

expenditure.21

Samuel A. Hudson did not work alone on

the project, but not

all of his associates have been

identified. Without giving names,

he mentions in one of the guide books

that "the artists have com-

pleted the sketches of the Mississippi

above the falls of St.

Anthony."22 An upper

Mississippi section, however, if planned

originally, failed to become an

important part of the completed

panorama. The names of the main artists

were revealed in the

19 Louisville Democrat, April 15, 1848.

20 Ibid., March 29, 1848.

21 Cincinnati Gazette, quoted in

New Haven guide book, p. 16; Providence (R. I.)

Republican Herald, September 13, 1848; Yankee Blade (Boston), November 11,

1848, Boston Daily Mail, November

11, 1848, both quoted in Boston guide book,

pp. 26-27, 28-29; Portland (Me.) Eastern

Argus, April 13, 1849; New Haven guide

book, p. 16; Hartford Courant, July 26, 1848; Boston

Courier, November 4, 1848;

Excelsior (Boston),

November 4, 1848, quoted in Boston guide book, p. 28; Bangor

(Me.) Whig and Courier, June 23,

1849.

22 New Haven guide book, Preface.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 361

press as the Messrs. Hudson, and were

described as "modest,

but very worthy and gentlemanly young

artists."23 One was later

identified as Samuel's younger brother,

George H. Hudson, by a

New

York minister, who congratulated him, after seeing "your

beautiful work of art."24 The

other brother, William, was probably

in the group of artists too, though not

specifically identified. George

W. Cassidy was another associate. A

German editor learned that

"Mr. Cassidy, with his friend

Hudson, had spent two years on those

rivers, in order to make the

sketches," for the panorama.25 This

artist became the proprietor of a

second copy of the painting, which

he exhibited.

Hudson's complete panorama was divided

into four sections,

with the canvas of each one being wound

around a large cylinder,

convenient for unrolling in exhibition

halls. The first three sections,

finished in April 1848 and put on

exhibition immediately, covered

the entire Ohio River and the

Mississippi River as far as the

Chickasaw Bluffs in Tennessee. These

sections were executed

on 20,000 to 22,000 square feet of

surface,26 the canvas being ten

feet high and its total length about

700 yards. The fourth section,

not finished or exhibited until the

fall of 1848, covered the lower

Mississippi Valley. It added some

17,000 or 18,000 square feet,

making the total surface of the whole

panorama between 37,000

and 40,000 square feet, and its

approximate length 1,300 yards,

or three-fourths of a mile.27 The

second copy of the whole painting,

produced in the same year and abridging

some of the upper Ohio

scenery, had an area of 27,000 or

30,000 square feet of canvas and

a length of half a mile.28 The

creation of this gigantic panorama

was generally conceded to be "a

great achievement of the palette

and the easel."29

23 Hartford Courant, July 21, August 2, 1848.

24 Worcester (Mass.) Spy, January

27, 1849, quoting a letter of A. V. C. Schenlk,

dated New York, June 28, 1848.

25 Leipzig

guide book, p. 27.

26 Louisville Morning Courier, April 18, 1848; New York Herald, June 10, 1848.

See also the cover of the New Haven

guide book and the Providence playbill.

27 Worcester Spy, January 24, 1849; Springfield Republican, March

13, 1849.

28 Leipzig guide book, Cover; Symbol (Boston),

November 4, 1848, quoted in

Boston guide book, p. 27.

29 Portland Eastern Argus, April 13, 1849; Providence General Advertiser, Sep-

tember 30, 1848.

362

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The subject matter of the panorama was

vast and varied,

especially as obliging editors of local

newspapers described it.

First of all, it delineated the

continuous and diversified landscape

along the majestic Ohio and Mississippi

rivers, with only a few de-

partures to places of natural curiosity

or historical interest. The

total coverage was nearly 2,500 miles,

extending through 15 degrees

of latitude and 12 degrees of

longitude, along the borders of eleven

states of the Union, and featuring the

scenes peculiar to the states

or regions passed, from the fir and

hemlock forests of the colder

northern Alleghanies, to the orange

groves of the sunny South.

On the canvas was a succession of many

physical features--forest

and plain, hills and hollows, mountains

and caverns, plateaus and

lowlands, stretching out in all

directions as far as the eye could see,

in the enlarging horizons of the

western country. Other scenes of

special interest were the earth mounds,

southern plantations, garden

spots, farm crops, and domestic

animals. All of these scenes "were

made to appear as they are seen by the

traveler" on the rivers, when

nature was robed in her best garments,

in all their natural colors.

Picturesque landscapes, at sunrise,

sunset, and by moonlight, ap-

peared regularly in the four days and

three nights covered in the

panorama voyage.30

The continuous rivers and their banks

formed the immediate

scenery. There were rocky snags,

sandbars, rapids, and falls; many

islets, islands, points, bends, deltas,

and marshes, all with luxuriant

plant life; and frequent cliffs from

250 to 500 feet above the water

level. The coverage was expanded by the

artist's method of giving

"views on both sides of the rivers--instead

of one side only, and his

perspective is so managed as to show

many creeks, and rivers, and

cutoffs, that could not be presented on

an apparently flat surface."31

Through this means were made visible

parts of the headwaters, the

mouths of numerous tributaries, some

canals on the Ohio, and many

bayous, lakes, and lagoons of the lower

Mississippi.

The painting depicted the flowing

waters of the river, and the

30 Portland Eastern Argus, April 13, 1849; Springfield

Republican, March 13,

1849; Boston guide book, p. 28; Hartford

Courant, July 21, 1848; Providence

Journal, October 9, 1848; Troy Post, April 20, 1849; Louisville

Journal, April 17,

1848; Providence Journal, August

8, 1848.

31 Boston Daily Courier, November 4, 1848.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 363

moving commerce on them--that vast

fleet of steam and flat boats,

going up and downstream, by day and

night. In the river scenes

were all types of western

watercraft--museums and palaces, Noah's

arks and lumber rafts, skiffs and

canoes, flat and keel boats, and

other cargo vessels. Splendid and

fashionable steamboats were

made "to float along amid the

variety of watercraft." Many of the

fatal boat wrecks alongs the

treacherous waters founds space on

the canvas.32

The most important subject matter of

the panorama consisted of

the many cities, towns, villages,

landings, and residences on the

banks of both rivers, so faithfully

portrayed they could be recog-

nized instantly. These scenes appeared

both during the day and

at night time. The geographical

distribution of the towns on the

rivers was such as to constitute mostly

"a panorama of the left

(East) bank of the Mississippi River,

from New Orleans up to the

mouth of the Ohio, and the right

(North) bank of the Ohio thence

up to Pittsburgh."33

The beginning or ending of the painting

depended upon the

way it was rolled on the cylinder, but

here we shall start on the

Ohio and follow Hudson's first guide

book as far as it goes, using

supplementary facts from the press.

Beginning in Pennsylvania,

there was first of all a striking view

of Pittsburgh, the Smoky City

of the West, at the junction of the

Alleghany and Monongahela

rivers, the head of the Ohio. This

large industrial city, with its

heavy river commerce and its

"surrounding superb scenery," all per-

fectly painted, formed the admirable

frontispiece of the whole

panorama.34 Opposite

Pittsburgh was Alleghany City, with its fine

bridge and seminary clearly visible

from the river. Then followed

George Rapp's utopian town of Economy,

and Beaver Town, on Big

Beaver Creek, across which a dam was

built and in full view.

Ohio, while sharing the river scenery

with two other states,

furnished most of the urban scenes.

There were views of Wellsville,

32 Providence playbill; Kennebec

Journal (Augusta, Me.), June 7, 1849; Spring-

field playbill; Lowell (Mass.) Advertiser,

December 9, 1848; Troy Post, April 20,

1849; New Haven Palladium, July 3,

1848.

33 Springfield Republican, March

20, 1849; Cincinnati Morning Chronicle, April

25, 1848; New Haven Palladium, July

3, 1848; Kennebec Journal, June 7, 1849.

34 Boston

guide book, pp. 28-29; Cincinnati Commercial, April 20, 1848; Hartford

Courant, July 17, 1848; Providence Republican Herald, September

27, 1848.

364

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

a New England type village; then

Steubenville and Martinsburg.

Next came the beautiful Wheeling

Island, on the Virginia side,

and the Mound Scene on the Little Grave

Creek, which the artist

thought was "one of the most

interesting scenes that can be put

upon canvas." Marietta, the

historic first settlement in Ohio, located

above the Muskingum River, had as its

showpiece "the remains of

an extensive ancient

fortification." Then appeared Point Harmar,

below the Muskingum, and Hockingport on

the Big Hocking

River. The moonlight view of

Blennerhassett's Island, with its

picturesque ruins of a splendid mansion

and the wooding-up scene

of the steamer Brilliant, was

the most beautiful island represented

on the Ohio. One observer was

captivated by "the cold steely tints

of the moon contrasting with the

firelight on the shore, and the

heavy profile of the woodland relieved

by standing out against

the silvery reach of waters through

which a noble steamboat is

cleaving its bright path."35 Then

followed the common views of

Coal Port, or Pomeroy's Landing, and

Gallipolis, with its semi-

globular mound.

The scenes on the river between Ohio

and Kentucky included

Hanging Rock by moonlight and Jackson

Furnace Landing at the

Little Scioto River. Two remarkably

accurate pictures, with elements

of pathos in them, were seen at

Portsmouth, on the big Scioto

River, where only the naked abutments

of the great bridge re-

mained after a flood disaster,36 and

at Manchester Bar and Islands,

where was still visible "the wreck

of the unfortunate steamer, A. N.

Johnson" that had taken its heavy toll of life. Both Aberdeen,

Ohio,

and the opposite town of Maysville,

Kentucky, were shown, as

well as Ripley, Ohio, just below Red

Oak Creek.37

The last city in Ohio, and terminal

point of the first section of

the panorama, was Cincinnati,38 the

Queen City of the West and the

largest one on the rivers except New

Orleans. In the picture were

the floating wharves and river traffic,

the commercial marts, social

halls, and professional colleges, and

such landmarks as the Observa-

tory, Mount Adams, and the Landslide. A

local editor felt "the

35 Yankee Blade, November 11,

1848, quoted in the Boston guide book, pp. 9, 29.

36 Louisville Democrat, March 13, 1848.

37 Cincinnati Commercial, April

14, 1848.

38 Hartford Courant, July 21, 1848.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 365

view of Cincinnati is represented as

very correct, surpassing any

other picture yet executed" of the

city.39

The towns on the lower Ohio formed the

second section of the

panorama. Indiana was well represented

with its cities and towns,

and the border state of Kentucky had a

few urban scenes. Starting

with the Miami River, near the Ohio

border, the views included

North Bend, with the residence and

grave of President William

Henry Harrison; Lawrenceburg, Aurora,

and Rising Sun; the Cleft,

or Devil's Hoof Mountain, and the Big

Bone Lick health resort;40

the Swiss town of Vevay, Carrollton

Point, and Boones Oak on the

Kentucky River; Madison, with its hills

three hundred feet high, and

the small town of New London. Just

above the Ohio Falls were a

near view of Jeffersonville, Indiana,

and a distant view of Louisville,

Kentucky. Here the falls made a very

attractive sight, and Corn

Island that divided the river, added to

the beauty of the scene. Next,

New Albany, the largest city in

Indiana, appeared below the falls,

with its wide streets lined with trees.

Then followed two romantic

spots--the Haunted Mill at Brandenburg,

Kentucky, and Leaven-

worth, Indiana, with an encampment of

Indians as seen by moon-

light. The concluding views of Indiana

were of the Cannelton Coal

Banks on the Rock Island Bend, the

enchanting Green River Islands,

and finally Evansville on the great

northern bend of the river.

Only a small part of Illinois touches

on the lower Ohio, and

the panoramic scenes there were few in

number but very impressive

ones. First, there was the Wabash

River, the border line between

Indiana and Illinois, and just below it

Shawnee Town, a commercial

center of southern Illinois. Then

appeared Caseyville, Kentucky,

with "tobacco plantations,

Caseyville Bluffs, a field of hemp shown

in the foreground [and] slaves at

work." Here is where the painter

"with infinite skill abandoned the

river, and laid his scene in the

romantic fields of Kentucky." The

excellent workmanship made this

a gem of the piece.41 Farther down the

river, on the Illinois side,

were depicted the famous chain of

bluffs that included Cave-in-Rock,

Battery Rock--standing 240 feet in the

middle of the river--the

Devil's Portico, and Castle Rock

towering 500 feet high. These

39 Cincinnati Morning Chronicle, April 25, 1848.

40 Boston guide book, pp.

11-12.

41 Louisville Democrat, April 21, 1848.

366

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

were all splendid views, "executed

with fine artificial effects," that

never failed to excite wonder and

admiration.42 After passing the

Golconda Islands and the villages of

Metropolis and America, we

come to Cairo, the last and corner city

of Illinois, at the mouth

of the Ohio. It was represented by two

views, one showing the

burning of the White Rose steamer

on the Ohio, and the other

showing the town from across the

Mississippi.43

The third section of the panorama,

probably a shorter one.

pictured the Mississippi River between

the mouth of the Ohio and

Memphis. On the west side, the views

were of "the low distant

shores of Missouri and Arkansas, with

their forests of cottonwood,

sycamore and ash." New Madrid,

Missouri, was featured as a

town destroyed by an earthquake that

reversed the course of the

river for a few miles. On the east

bank, below Cairo, were the well-

known iron and chalk banks of Kentucky.

Along the river were

special views of Wolf Island, Pilgrim's

Island, Needham's Cutoff,

Hales Point, with its cypress swamps,

and Plumb Point Bar, where

snags and wrecks abounded. In

Tennessee, the remaining part of

the third section included the

Chickasaw Bluffs, and an encamp-

ment of Indians, "viewing for the

last time their favorite hunting

grounds, and the graves of their

fathers."44

The fourth and last section covered the

lower Mississippi, with

the states of Tennessee and Mississippi

on the east and Arkansas

and Louisiana on the west. Here are

shown the characteristic

features of the southern country and

five of its large cities.45

Hudson's second guide book lists the

successive scenes. The first

one on the east side was Memphis, with

an impressive skyline 240

feet above the river, on the Fourth

Chickasaw Bluff. The United

States naval yards were at the mouth of

Wolf River, and Fort

Pickering was just below the city. On

both sides of the river were

shown many cultivated fields of

"sugar cane, cotton, tobacco and

hemp--with slaves at work on the

plantations."46

Farther down the river were St. Francis

Island and Horse Shoe

Cutoff, and then Walnut Hills, some of

them five hundred feet

42 Hartford Courant, July 22, 1848.

43 Boston Courier, November 4, 1848.

44 Springfield playbill.

46 New Haven Register, March 2, 1849.

46 Springfield playbill.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 367

high, on which stood Vicksburg,

Mississippi, with its surrounding

plantations and cotton fields. Then

passed in review Palmyra Island,

Arkansas, and its steamboat wrecks in

the narrow channel--the last

one the Prairie Bird--Grand

Gulf, Mississippi, the Cane Brakes, and

the Louisiana Lagoons, with their

Palmettos, Spanish moss, and

wilds of nature. Natchez, with its

elevated location, its pretentious

mansions of the planter class, its

characteristic woods covered with

giant grapevines--all presented an

impressive appearance. Then

followed Ellis' Sand Cliffs, the Red

River with a moonlight scene

of Red River Cutoff, and the Bayou Sara

Furnace, with another

moonlight view of the white cliffs.

After passing La Cour's planta-

tion, which featured a sugar-cane crop,

an old French mansion,

and the river levees, came a fine view

of Louisiana's capital city,

Baton Rouge, high above the river, with

its state house and United

States barracks. Nearby across the

river was General Zachary

Taylor's noted plantation. The other

scenes on the way to New

Orleans included Cantrell Church and

its cemetery on the western

shore, Old Red Church, the wharf at

Willow Grove, "with a ship

being loaded with sugar," Arnaud's

or College Point, the location

of the University of Louisiana and St.

Gabriel Church, Carlton,

and McCartey's Point, just west of the

Crescent City.

The last scenes on the canvas were

those of the colorful city of

New Orleans and just below it the

historic battleground of General

Andrew Jackson during the War of 1812.

The view of this com-

mercial emporium, with its upper and

lower shipping and its flat

and steamboat landing, revealed forests

of masts of ships from the

sea and its thousand river boats. Among

the prominent public

buildings were St. Charles Exchange and

Theater, St. Patrick

Cathedral, the Barracks, Water Works,

Government House, and

Branch Mint of the United States. The

picture of New Orleans,

greatest of southern seaports and

largest of western cities, con-

stituted a fitting climax to the

pageant of towns and cities bordering

on both the Ohio and Mississippi

rivers. In the whole panorama, this

great metropolis was "represented

with a correctness . . . seldom

seen surpassed on canvas."47 and,

like the other large cities, it

formed a magnificent picture of itself

alone.48

47 Providence Journal, January 2, 1849.

48 Louisville Democrat, March 29, 1848.

368

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Hudson exhibited his panorama first in

Louisville, Kentucky,

where it was produced. In March 1848 he

offered a preview of the

part from Portsmouth to Ripley, Ohio,

to some prominent people

who could help advertise the work. The

first public showing of the

three sections just completed was

announced for April 15, at the

Odd Fellows Hall, with tickets at fifty

cents. Editors were highly

receptive. The enterprising artist had

special claims for the fullest

patronage of the citizens of

Louisville, because his studio was there

and his work had merit.49 It

was superior to his earlier painting

of the Hudson River and even surpassed

Banvard's production in

scenic coverage and artistic skill.

Moreover, all western people

had a special interest in this great

picture that was soon to be

shown in the eastern cities and then

taken to Europe, where the

West would be on display. It was

therefore urgent that all those

living in the towns and states

bordering on these rivers should see

for themselves "whether the artist

has done justice to them in his

delineations."50

At the appointed time and place the new

painting was unrolled

before a very large audience that

watched attentively all the scenes

as they passed. Frequently they

demonstrated their feelings of ap-

proval by ovations, enthusiastic

exclamations, and thunderous ap-

plause, especially at the moonlight

views.51 After drawing large

crowds for one week, the painting was

boxed up and taken up the

river to Cincinnati on April 24. There

it came highly recommended

by editors, steamboat captains, and

river pilots. Mayor William R.

Vance and the city council of

Louisville extolled the work as "a

correct estimate of the beauty, extent

and fertility of the Great

Valleys."52

The citizens of Cincinnati had advance

notice of Hudson's new

panorama, which opened in College Hall

on April 24. Tickets

were reduced to twenty-five cents to

gain wider patronage. Oppor-

tunities were afforded all school

children to see this object-lesson

in geography, and sometimes three

crowded performances were

held in one day. Hudson was acclaimed

as a polished gentleman

49 Louisville Morning Courier, April 15, 1848.

50 Ibid., April 18, 1848.

51 Cincinnati Commercial, April 20, 1848; Louisville Morning Courier, April

17, 1848.

52 New Haven guide book, p. 15.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 369

and a great scenic artist, whose

panorama inspired viewers with

national pride.53 After a

successful run of one week, the proprietor

left Cincinnati on May 2 for Pittsburgh

and the East, taking with

him new recommendations from Mayor H.

M. L. Spencer, editors,

and river men.54

The Pittsburgh press announced the

coming of the picture on

May 9,55 but it failed to report its appearance there. Then it

opened

at Franklin Hall in Baltimore on May 15

for a run of two weeks,

with tickets starting at fifty cents

but later reduced one half. The

members of the Presbyterian General

Assembly, while convened in

that city, visited the exhibition and

gladly urged all church people

to profit by seeing it. After gaining

wide patronage, the show ended

on June 5 for an appearance in New

York.56

The press notices in New York began two

weeks before the

canvas arrived in the Apollo Rooms at

410 Broadway on June 12.

Past citations assured the public of

its merits and popularity. The

great production, always judged

creditable to the artist, met with

a good reception in this metropolis.

The people crowded the hall

daily to enjoy traveling at home, and

then the panorama left New

York on June 24 for Connecticut.57

On the same day, it opened at the

Temple in New Haven, where it

continued until July 14. The first

guide book was printed here and

sold at the hall for twelve and

one-half cents. William Goodwin

joined the Hudsons to promote

patronage, and W. P. Gardner

played a new pianoforte with aeolian

attachment, to accompany

the show. An interesting lecturer,

sometimes the artist himself,

always explained the passing scenes.

The population responded and

filled the hall nightly with admiring

crowds, and the school children,

as many as five hundred in a group,

eagerly attended the matinees.

The new panorama was becoming popular,

as "traveling made

easy and cheap 'for the million.'"58

53 Cincinnati Commercial, April 14, 24, 28, 1848; Cincinnati Morning

Chronicle,

April 29, 1848.

54 Boston guide book, p. 23.

55 Pittsburgh Dispatch, May

9, 1848.

56 Baltimore Sun, June 2, 1848; Providence playbill; Baltimore

Clipper, June 3, 1848.

57 New York Herald, June 12, 14,

1848; New York Sun, June 13, 1848; Worcester

Spy, January 27, 1849.

58 Hartford Courant, July 17, 19, 1848; New Haven Register, July

3-14, 1848;

New Haven Palladium, June 24, 1848.

370

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The artist, with new support for his

work coming from the

teachers, preachers, and editors, moved

on to the American Hall

at Hartford on July 18, where handsome

patronage awaited him,

and he continued there until August 1.

The people felt an increased

patriotic fervor for their great and

prosperous country.59 Mrs. L. H.

Sigourney expressed her thrills in a

poem about Hudson's pan-

oramic voyage,60 and a deaf

and dumb school shared the new

experience with the aid of their

teachers. The whole commmunity

had a moral uplift after seeing this

work, so elevating and refining

in its character, it was said. At this

point the Hudsons suspended

their tour for three weeks in August in

order to spare their visitors

the discomforts of the extreme hot

weather and to gain a period of

rest for themselves,61 and time to work

on the final section.

The exhibition went next to Providence,

Rhode Island, opening

in Franklin Hall on August 21 and

running for three months. It

received its best patronage there, from

both city and country.

Playbills, filled with favorable press

comments, were widely dis-

tributed, and advertisements stressed

the educational and moral

values of the picture. During the first

month many people of all

classes went to the performances. In

the second month, a thousand

school children were attending weekly,

and even after the thirteenth

week there were sometimes a thousand

visitors daily. This panorama

was still in Providence in November,

with an early removal north-

ward being planned.62

It was not long, however, before the

artist had completed the

long-expected final section of the

lower Mississippi and added it

to the other three sections on view in

Providence. Besides finishing

the original painting he had also

produced a second copy of it to

satisfy the great popular demand.

Thereafter the two panoramas

were exhibited to the public on

separate itineraries--one continuing

in Providence, the other opening in

Boston. The Providence press

announced on December 30 that "Mr.

Hudson, having completed

59 Hartford Courant, July 18, 21, 26, August 2, 1848; Hartford Weekly

Courant,

July 22, 1848.

60 Hartford Courant, July 27, 1848; Providence playbill.

61 Hartford Courant, August 2, 1848.

62 Providence General Advertiser, August 26, September 30, November 18, 1848;

Providence Republican Herald, October 4, November 8, 1848.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 371

his magnificent painting of the Ohio

and Mississippi rivers," would

reopen for exhibition at Franklin Hall

during the first week in

January 1849.63 Then it was removed to

Amory Hall in Woonsocket,

Rhode Island, on January 9 for another

week.64

Following the Woonsocket performances,

the artist opened his

show at Waldo Hall in Worcester,

Massachusetts, on January 24,

where it had good attendance for a

month. The picture was sched-

uled for reappearance in Hartford, but

the American Hall there

was destroyed by fire on February 11.

Hudson then remained

another week, giving the lectures

himself, and offering benefit per-

formances for the keeper of the hall

and the musician.65 He made

a return visit to New Haven on February

28, remaining until

March 10, where the lower Mississippi

section was featured. Again

many children saw it while it was in

that city.66 The show opened

next in Hampton Hall, at Springfield,

Massachusetts, on March 14

for two weeks. The record of its

unprecedented success during the

past year was well known, and the

attendance was heavy here too.

One more stop was scheduled, at Troy,

New York, in April, before

the European tour would begin in May.67

The famous picture appeared at Morris

Hall in Troy on April 10

for a period of ten days. Then a

tragedy occurred. The astounding

news came from the press that on April

19 "about half-past eleven

o'clock, p. m., fire was discovered

breaking out near the second

flight of stairs, in Morris Hall."

It soon swept across the building,

"wrapping the immense canvas of

the panorama in its flames." The

painting, which was valued by its

proprietors at $25,000 or $30,000

was only insured for $10,000.

Arrangements had been almost com-

pleted to send it to France. The artist

received the sympathy of the

whole community for the loss of his

work of rare merit and great

value.68

The news spread rapidly over the East

and West, where some

63 Providence General Advertiser, December 30, 1848.

64 Woonsocket

Patriot, January 5, 1849.

65 Worcester Spy, February 19, 22, 24, 1849.

66 New

Haven Register, February 27, March 10, 1849; Springfield Republican,

March 14, 1849.

67 Springfield Republican, March 8, 20, 1849.

68 Troy Budget, April 19, 20, 1849; Troy Post, April 20, 1849.

372

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

half million people had already paid

admission fees to see this

spectacle that had helped raise the

level of popular education in

America and rewarded the artist with a

fortune of some $100,000.69

Though the artist assured the public

that most of the original

sketches from which the painting was

made were preserved, and

that the work would be reproduced as

soon as possible,70 there seems

to be no evidence that it was replaced.

Fortunately, however,

another copy had already been created,

and George W. Cassidy was

exhibiting it in Portland, Maine, at

the time the original one was

destroyed. The editors there confirmed

the fact that the lost painting

was "a copy of the one which is

now exhibited in this city."71

The second painting of the Ohio and

Mississippi rivers, which

the Boston press announced that

"Mr. Samuel Hudson has just com-

pleted,"72 was first

advertised on October 12, 18, and 28, and then

it opened in Amory Hall, on October 30,

1848. The admission

charge was twenty-five cents, with

liberal terms offered for large

parties coming from neighboring towns.

Press notices appeared

regularly in Boston and other New England towns.73 The artist

again made known his many certificates

of merit from the South

and West, as well as the East, and he

also printed a new complete

guide book in Boston. Finally, the

editors reminded the citizens that

the painting was "the production

of a Boston boy," whose "skill

and genius must be honored at

home."74 The population responded

generously. During November, Amory Hall

was judged to be "one

of the most popular and attractive

entertainments in the city."75

The two hours spent in the hall seemed

like moments to the de-

lighted spectators, because of the

absorbing interest excited and the

frequent warm applause evoked.76 Olive

A. Stevens expressed her

69 Albany Argus, April 24, 1849; Woonsocket

Patriot, April 27, 1849; Springfield

Republican, April

20, 21, 1849; Hartford Courant, April 20, 21, 1849; Portsmouth

(N.H.) Journal, April 28, 1849.

70 Troy Post, April 20, 1849.

71 Portland Advertiser, April 25, 1849.

72 Boston Courier, November 4,

1848.

73 Boston

Mail, October 18, 1848; Worcester

Spy, January 24, 1849; Salem

Gazette, December 8, 1848; Portsmouth Journal, November

11, 1848; Portland

Advertiser, March

29, 1849.

74 Boston Chronotype, November

18, 1848.

75 Boston Atlas, November 10,

1848; Boston Journal, November 1, 18, 1848.

76 Boston Bee, November 11, 1848.

HUDSON'S PANORAMA 373

appreciation of the artist's work in

another poem.77 After being

seen by crowded halls for five weeks,

Hudson's first show in Boston

came to a close on December 7 and was

taken to Lowell,

Massachusetts.78

The exhibition opened in Wentworth Hall

at Lowell on De-

cember 11 for a run of two months. The

people in this factory

town were pleased to see this famous

work of art that had already

been seen in the eight large cities of

Cincinnati, Louisville, Balti-

more, New York, New Haven, Hartford,

Providence, and Boston

by more than 380,000 persons in a

period of eight months. Lowell

added to this number by attracting

throngs to the hall, and the

painting was still being advertised

there until February 8, 1849.79

The itinerary of this copy during

February and March is un-

certain. The Portland press stated

specifically that Hudson's

panorama "was exhibited in Boston

five months, to the admiration

of thousands of visitors,"80

and carried his advertisements there at

Amory Hall regularly from November 6,

1848, to March 31, 1849,

when the exhibition was removed to

Portland.81 The Boston press,

however, fails to offer supporting

facts, and does not carry Hudson's

notices at all after the removal to

Lowell in December 1848. There-

after the hall was occupied by other

exhibitors, but it was possible

for two panoramas to be in Amory Hall

at the same time, since

it had two large halls for public

meetings.82

The exhibition was well attended in

Maine, though the popula-

tion was sparser. It opened in Portland

on April 9. The manager

there, George W. Cassidy, incurred

heavy expense to bring out the

painting in great style, at Exchange

Hall, the only place in town

large enough to hold it. Cassidy

himself explained the moving

scenes, and appropriate music was

provided. The show was ap-

preciated in Portland and remained

there until the middle of May.83

77 Boston guide book, pp.31-32.

78 Boston Evening

Transcript, December 11, 1848.

79 Lowell Advertiser, December 9, 1848; Lowell Gazette, December 22,

1848;

Boston Mail, January 4, February 8, 1849.

80 Portland Eastern Argus, April 7, 1849.

81 Portland Advertiser, November 8, 1848--April 7, 1849.

82 Boston Mail, January-April,

1849; Boston Courier, July-December, 1848; January-

April, 1849; S. Damrell, A Half

Century of Boston Building (Boston, 1895), 31.

83 Portland Transcript, April 14, 1849; Portland Advertiser, April 5, 21, May

12, 1849.

374

THE OHIO HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

We find it on view in the State Street

Chapel at Augusta on June

1 for a period of two weeks, where the

people found it worthy

of their patronage.84 The

painting was taken to Bangor on June 18

and shown in Market Hall for three

weeks. There the proprietor

announced that "in a short time

the panorama will be removed to

Europe for exhibition," and it

closed in Bangor on July 7, 1849.85

Information on the full itinerary

abroad is lacking, but we find

the panorama on view next in Leipzig,

Germany, in September 1850.

Cassidy employed the Buchhandlerborse

for the purpose, and had a

new German edition of the Boston guide

book printed there. The

picture was at the Saale der Tonhalle,

in Hamburg during the

same year. The German press received

the American painting with

much interest.86 The later

disposition of the famous panorama,

either in America or in Europe, remains

obscure, and the final fate

of this copy of Hudson's work, unknown.

84 Kennebec Journal, May 31,

1849.

85 Bangor Whig and Courier, June 25, July 2, 4, 7, 1849.

86 Leipzig guide book, pp. 25-28.