Ohio History Journal

LLOYD SPONHOLTZ

The Politics of Temperance

in Ohio, 1880-1912

The Price of an Ohio License

What's the price of a license? How much

did you say?

The price of men's souls in the market

today?

A license to sell, to deform, to

destroy,

From the gray hairs of age to the

innocent boy.

How much did you say?

How much is to pay? How compare with

your gold?

A license to poison .. .a crime oft

retold-

Fix a price on the years and the manhood

of man-

What's the price, did you say1

In 1913 the Anti-Saloon League of

America (ASL) announced its

drive for federal constitutional

prohibition. Within seven years the

nation ratified the Eighteenth

Amendment. This remarkable record of

political success glosses over the many

years of bitter struggle on the

state and local level that contributed

to this accomplishment. Fur-

thermore, the speed with which the ASL

achieved its goal suggests that

the wets were on the run by the time the

ASL made its announcement,

and that they were merely fighting a

holding action. An examination of

the political jockeying between Ohio

wets and drys in the years im-

mediately preceding 1913, however,

suggests that the pendulum there

was swinging in favor of the wets, a

development which culminated in

the adoption of a constitutional liquor

license in 1912.

Ohio was particularly significant to the

dry cause. As the birthplace of

the Anti-Saloon League, Ohio drys could

take pride in residing in the

state that spawned the leading

temperance organization in the nation by

1910. Not only did the ASL maintain its

national headquarters in Wes-

terville, near Columbus, but the Ohio

branch of the ASL was the

financial and administrative cornerstone

of the national organization.

Dr. Sponholtz is Assistant Professor of

History at The University of Kansas, Lawrence.

The author wishes to acknowledge that

the research for this study was in part made

possible by a University of Kansas

General Research Grant.

1. Peter Odegard, Pressure Politics:

The Story of the Anti-Saloon League (New York,

1928), 66.

Politics of Temperance 5

The Ohio affiliate alone accounted for

twenty-two percent of all state

league contributions to the national

coffers in 1913, and it served as the

political training ground for many who

later assumed leadership roles in

other state leagues as well as in

national offices.2 Thus the political

course of the liquor issue in Ohio

assumes an inordinately large role in

the prohibition movement at large.

For the most part the liquor question in

the state was directly trace-

able to the anomalous wording of the Ohio Constitution

of 1851. Written

within the background of the pre-Civil

War temperance fervor, dele-

gates to the 1851 Ohio constitutional

convention reached new heights of

ambiguity when they submitted to the

voters separate from the rest of

the constitution the following

amendment:

No license to traffic in intoxicating

liquors shall hereafter be granted in this state;

but the general assembly may, by law,

provide against evils resulting there-

from.3

Voter adoption of both the constitution

and the liquor proposal set the

stage for decades of bickering since the

amendment left quite unclear to

what extent the legislature was

empowered to regulate the liquor trade.4

Given this confusion, it is both ironic

and understandable that Ohio

should have become the birthplace of the

post-Civil War organized

temperance movement. The National

Woman's Christian Temperance

Union emerged in Cleveland in 1874,

while the Anti-Saloon League

grew out of the temperance fervor at

Oberlin College in 1893. Even the

Prohibition Party held its early

national conventions in Ohio from 1872

to 1880.5 Political interest

in the liquor question, as measured by legisla-

tive activity on the subject, peaked in

Ohio during the 1880s and again in

the first decade of the twentieth

century. In each case the peak occurred

in the decade following the emergence of

a national temperance body,

but for the most part the emphasis of

each wave differed.

The initial thrust of the 1880s involved

legislative attempts to evade

the anti-license provision by imposing

an annual tax on retail liquor

dealers. The state supreme court

declared the laws unconstitutional;

both the $1,000 bond required in the

Pond Law (1882) and the Scott Law

2. Ohio furnished over forty state

superintendents to the ASL, Ibid., 9, n. 6. The ASL

financial statement can be found in the

League's weekly journal, New Republic, De-

cember 26, 1913.

3. Ohio, Constitution (1851), Article

XV, Section 4.

4. Joe Hoover Bindley, "An Analysis

of Voting Behavior in Ohio" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Pittsburg,

1959), 66.

5. Ernest Cherrington, ed., Standard

Encyclopedia of the Alcohol Problem, 10 vols.

(Westerville, 1929), V, 2050-2052. Also

see F. M. Whitaker, "Ohio WCTU and the

Prohibition Amendment Campaign of

1883," Ohio History, LXXXIII (Spring 1974),

84-102.

6 OHIO HISTORY

proviso (1883) making the tax a lien

upon the premises constituted a

license law in the view of the judges.

In October of 1883 the legislature

made a further attempt to resolve the

matter by presenting voters with a

constitutional alternative: either

permit the general assembly to regulate

and tax the liquor traffic or enact

statewide prohibition. Although pro-

hibition achieved a plurality vote of

323,000 to 241,000, it failed to

receive the constitutionally required

majority of all votes cast in that

gubernatorial election, and unlicensed

confusion remained.

Three years later the General Assembly

passed the omnibus Dow Act

in a further attempt to overcome

judicial objections. Little difference

between it and its predecessors is

apparent to the casual observer. It

applied a $250 annual tax upon the

liquor traffic (defined as "buying,

procuring and selling" but not the

manufacture and wholesale distribu-

tion at the manufactory); forbade Sunday

and election day selling, as

well as sales to minors; created a

"dry zone" around most public

institutions and militia encampments;

and gave to municipalities

"power to regulate ale-, beer, and

porter-houses and shops."6 Court

approval of the Dow law appears to have

reflected a change of judicial

attitude as much as successful

legislative tinkering.7 In any event, by

1912 the annual tax had been raised to

$1,000.

Further legislative action on the liquor

question awaited the

emergence of the Anti-Saloon League in

1893. By the turn of the century

the temperance movement in Ohio had

become inseparably linked with

the League and its undisputed guiding

spirit, Wayne B. Wheeler.

Wheeler attended Oberlin College in the

1890s. Both the community and

the college had been in the vanguard of

the state temperance movement;

it was a meeting of the Oberlin

Temperance Alliance in 1893 under the

leadership of the Reverend Howard H.

Russell (Oberlin class of 1888)

that gave birth to the Anti-Saloon

League (ASL).8 Wheeler joined the

6. Cherrington, ed., Standard

Encyclopedia, V, 2045-2046; Bindley, "Analysis of

Voting Behavior in Ohio," 66-67.

The provisions of some or all of these acts are available

in a variety of sources: Ohio, Secretary

of State, Proceedings and Debates of the Constitu-

tional Convention of the State of

Ohio, January 9 to June 7, 1912, 2

vols. (Columbus,

1912), I, 367-68 (hereafter cited as CC

Debates); Philip D. Jordan, Ohio Comes of Age,

1873-1900, Vol. V of The History of the State of Ohio, ed.

by Carl Wittke (Columbus,

1943), 175-77,294. The Dow Act

specifically forbade sales in Cincinnati between midnight

and 6 a.m.

7. According to the state supreme court (Adler

v Whitbeck, 44 O.S. 559), "The differ-

ence between the tax upon a business and

what might be termed a license, is, that the

former is exacted by reason of the fact

that the business is carried on, and the latter is

enacted as a condition precedent to the

right to carry it on." Quoted in Augustus R.

Hatton, "The Liquor Situation in Ohio,"

Proceedings of the Buffalo Conference for Good

City Government and the Sixteenth Annual

Meeting of the National Municipal League

(1910), 412.

8. Justin Steuart, Wayne Wheeler, Dry

Boss (New York, 1928), 15-34, 47-49.

|

Politics of Temperance 7 |

|

|

|

organization after graduation in 1894, while studying law at Western Reserve University. He became attorney for the League after receiving his law degree in 1898, and five years later he began a twelve-year stint as superintendent of the Ohio ASL. The birth of the League coincided with what economist Kenneth Boulding termed The Organizational Revolution, in which the forces of industrialization, urbanization, and immigration resulted in the worldwide emergence and proliferation of business, trade, labor, farm, professional, and reform organizations. According to Samuel P. Hays, these organizations altered traditional patterns of human relationships within society in several ways. For example, business structures such as corporations that sought to utilize technology relied upon a large number of specialists. In order to bring about coordination among these specialists, corporations arranged them in a heirarchical pattern that defined lines of authority and responsibility, which resulted in the emergence of bureaucracies. The need for a compatible environment in which to operate led these technical systems to define their specific |

8 OHIO HISTORY

goals in broad, general terms; workers,

as well as the iron and steel

industry, need a protective tariff since

an expanded industry meant

more jobs. At the same time that

bureaucratic heirarchies were forming,

specialization spurred the development

of functional associations, in

which people of like interest or

specialty (such as physicians) main-

tained national contacts within an

egalitarian framework. In the process,

linkages developed between the local

community and society at large,

particularly in response to innovation.9

In many respects the Anti-Saloon League

symbolized these social

reorderings. Utilizing as a base

existing Protestant congregations (usu-

ally Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian,

and Congregational), the League

superimposed a large staff of full-time

paid professionals in which au-

thority was highly centralized.

Operationally the League focused upon

the one single issue embraced in its

title; it refused to take a stand on

other matters. Eschewing the third-party

route the ASL conscientiously

worked in a bipartisan fashion within

the two-party system-a tactic

dictated in Ohio by the existence of a

strong temperance element within

both major political parties.10

Wheeler personified the League. His

somewhat critical biographer

found several characteristics dominant

in Wheeler's makeup. For one

thing, no one ever questioned his

sincerity or tireless devotion to his

cause. At one point early in his career

he campaigned against a state

legislator by peddling a bicycle over

the entire legislative district.

Wheeler was an unquestioned opportunist.

A candidate need not be a

temperance man in his personal life in

order to receive League endorse-

ment; he only had to vote dry.

When asked why he supported a man who

owned two saloons Wheeler explained that

"his owning a saloon doesn't

have anything to do with his official

actions." He rarely attacked per-

sonally a wet who had political

influence-a restraint that presumably

swayed some to his cause.11

This opportunism extended into the

political sphere. "The League

stands for prohibition in those states

which have or are ready for such

laws. Elsewhere it favors local

option."12 "The League believes in

self-government," and "has

secured and used local option whenever it

9. Kenneth Boulding, The

Organizational Revolution (New York, 1952), 202; Samuel

P. Hays' introductory essay in Jerry

Israel, ed., Building the Organizational Society:

Essays on Associational Activities in

Modern America (New York, 1972), 1-15.

10. Odegard, Pressure Politics, 2-18,

79; Steuart, Wayne Wheeler, 15-34, 47.

11. Odegard, Pressure Politics, 87;

Steuart, Wayne Wheeler, 12, 62-64. Yet Steuart also

noted Wheeler's preference for threats

rather than persuasion, and his penchant for

stringent penalties and relentless

prosecution, 12-14.

12. Odegard, Pressure Politics, 117,

quoted from William H. Anderson, The Church in

Action Against the Saloon (n.p., n.d.), 30ff.

Politics of Temperance 9

has been possible to make an advance

along temperance lines thereby. It

has also, however, consistently opposed

the adoption and use of local

option where such adoption and use has

meant a backward step in

temperance reform."13

Wheeler and the League redirected the

thrust of the Ohio temperance

movement from that of the 1880s. There

was a renewed emphasis upon

the enforcement of existing liquor laws.

As League attorney, Wheeler

averaged better than a case a day in his

support of liquor law prosecu-

tions, totaling an estimated three

thousand cases over the span of his

career. Exposure of judicial efforts to

thwart enforcement also occupied

his time.14 More

significantly, the League embarked upon a series of

local option laws designed eventually to

dry up all but the metropolitan

areas of the state. In fact, early in

its existence the ASL was known as

the "Local Option League." Actually

the strategy built upon an 1888

amendment to the Dow Act, which provided

for a referendum on the

question of liquor sales in any township

outside of a municipal corpora-

tion whenever twenty-five percent of the

qualified voters so petitioned.

Its impact, of course, was to drive

liquor sales inside corporate limits.

The Beal Law (1902) provided the same

option for those inside town or

village limits, but raised the petition

requirements to forty percent. Two

years later the League-sponsored

Brannock Act further invaded munic-

ipal boundaries by permitting

inhabitants to establish residence districts

and then to hold an election upon a

forty percent petition. This, in turn,

was shortly amended to make the petition

itself sufficient to close

saloons; the election was eliminated.

The culmination of this local

option drive came in the 1908 Rose law,

extending the local option

election to counties if thirty-five

percent of the electors so desired. All of

the local option elections allowed for

periodic electoral reviews of the

initial decision, ranging from two years

for the Beal and Brannock acts

to three years for the Rose law.15

The Rose law proved to be so popular

that, by April 1909, elections

had been held in sixty-seven counties,

fifty-eight of which had voted

dry. Five additional counties had

previously chosen prohibition under

the Beal law, so that by mid-1909

sixty-three of Ohio's eighty-eight

counties had elected to outlaw the sale

of intoxicants.

13. The Anti-Saloon League Yearbook:

1909, 168. Hereafter cited as ASL, Yearbook.

14. Steuart, Wayne Wheeler, 49,

62.

15. Charles E. Zartman,

"Prohibition Question in Licking County, 1908-1912" (M.A.

thesis, Ohio State University, 1938),

3-4; Odegard, Pressure Politics, 116; Cherrington,

ed., Standard Encyclopedia, V, 2046-2047. The

residence district law as amended estab-

lished many criteria, including the

maximum dimensions of contiguous territory, the

maximum population embraced, the

proportion of residence versus commercial property

permissable on a block, etc. See William

H. Page, ed., The General Code of Ohio, 4 vols.

(Cincinnati, 1921), II, Sections

6140-6161.

|

10 OHIO HISTORY

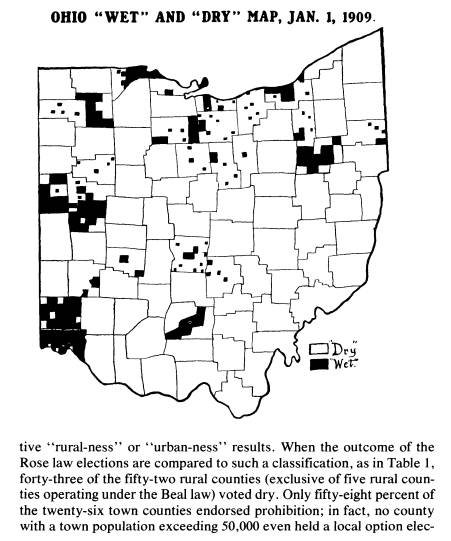

A visual summary of the various local option campaigns is presented in Map 1. Most of the dark "wet" areas embrace urban centers such as Cincinnati, Columbus, Toledo, Cleveland, and Canton. Major excep- tions are those German counties in northwest and west-central Ohio. Other evidence supports the rural nature of this prohibition movement. For instance, if Ohio counties are classified according to the population of the largest community within their borders, a rough index of compara- MAP 1 |

|

|

Politics of Temperance 11

tion. Even among those counties which did vote dry,

towns were fre-

quently outvoted by the numerically dominant rural

drys. In an exami-

nation of election results brewers noted that the towns

of Newark,

TABLE 1

Rose Law County Option Election Results

By County, 1908-1909, As Classified

Along A Rural-Urban Continuum

Rural

Town Urban

No. % No. % No. %

Dry 43* 83 15 58 0

Wet 4 8 5 19 0

No Vote 5 9 66 23 5 100

*Five additional counties voted dry under the Beal Law

Zanesville, and Steubenville all fell into this

situation, although in other

instances (Scioto and Columbiana counties) there was a

distinct division

of opinion within or among incorporated areas.16

Local option laws, of course, did not always eliminate

sale of intox-

icants. Where law enforcement was lax, such as in

Newark, former

saloons became speakeasies or "blind tigers,"

or saloonowners con-

tinued to dispense alcoholic beverages by operating

"soft drink" estab-

lishments. In other areas such as Columbiana County, a

"dress-suit case

trade" emerged, where bootleggers rode the interurban

train to nearby

West Virginia and returned with a valise full of

half-pint bottles. Drug-

gists retained the right to dispense alcohol upon the

prescription of a

physician, and although the laws sought their

particular cooperation,

there remained ample opportunity for abuse.17

In order to solidify their victories the Anti-Saloon

League

supplemented their local option campaigns by sponsoring

other laws to

harass the liquor trade. For example, private clubs

could not dispense

liquors if located within dry territory. Another law

forbade the shipment

of liquor C.O.D. into dry areas. Saloons could be

abated as a public

16. United States Brewers' Association Yearbook:

1910, 24-43 (hereafter cited as

USBA, Yearbook); Ohio, Secretary of State, Abstract

of Votes Cast in Ohio under the

Rose Local Option Law (Columbus, 1909), 3-4. For purposes of analysis here,

Ohio

counties were classified according to the size of the

largest community within their

boundaries in 1910. Counties whose largest municipality

was less than 10,000 population

were classified as rural. "Town" counties

embraced a community with a population

between 10,000 and 100,000. The five Urban counties

were Hamilton (Cincinnati),

Montgomery (Dayton), Franklin (Columbus), Cuyahoga

(Cleveland), and Lucas (Toledo).

17. USBA, Yearbook: 1910, 24-43.

12 OHIO HISTORY

nuisance upon the second conviction for

a liquor law violation. Most

serious, however, was the "Search

and Seizure" Law enacted in 1906,

which instructed the appropriate

judicial officer to issue a search war-

rant upon the sworn complaint of any

individual who "has reason to

believe and does believe that liquor

laws were being violated at a given

location." Further, any law

officer having personal knowledge of such

violations "shall search

such place without a warrant or an affidavit

being filed." Private residences

were immune to search by warrant

except that portion used commercially.

Finally, a 1909 amendment to

the act authorized the prosecuting

attorney (or, if he failed to do so, the

probate judge) to hire private

detectives at a maximum cost of $125 per

month to aid in uncovering evidence of

infractions.18 In this way the

League hoped to counteract lax law

enforcement with legislation com-

pelling local officers to take action.

By 1910, then, the Anti-Saloon League

was riding a wave of nearly

uninterrupted successes. It had proved

its lobbying prowess in a series

of laws designed to isolate wet areas

and eventually to choke them

out of existence. Wheeler, in fact,

candidly shared his formula for

successful lobbying upon which such

legislative victories were

based.19 The ASL had

achieved its success by a strategic policy of

bipartisanship, seen in the nearly

equal partisan support given the Rose

law in both Ohio houses; eighty

Republicans and seventy-five Demo-

crats voted for the measure.20 In

politics, the League's policy of reward-

ing its friends and punishing its

enemies had born fruit. Over seventy

Ohio legislators with whom the League

had been at odds between 1895

and 1903 failed to be reelected. Even

governors were not immune; when

Governor Myron T. Herrick's attitude on

the Brannock bill incurred

League hostility in 1905, Wheeler

successfully persuaded his followers

to elect Democrat John Pattison. Strong

moral and financial support by

rural Protestants permitted the League

to maintain a ten-thousand-

square-foot printing plant in

Westerville, Ohio that printed weekly edi-

tions of its newspaper, The American

Issue, for each state league in the

nation. By 1910 it was turning out

350,000 issues per month, although its

capacity was four times larger. With

such political pressure, and

18. Ibid., 1909, 30; Zartman,

"Prohibition in Licking County," 3-4; Page, ed., The

General Code of Ohio, II, sections 6169-6186. Italics added.

19. Odegard, Pressure Politics, 115-116,

quoted from American Issue, Anniversary

Number, May, 1909.

20. Ibid., 82.

Politics of Temperance 13

propaganda potential, the League seemed

poised to make its ultimate

push for prohibition.21

League hostility was directed primarily

against the brewers, perhaps

because their association with saloons

was always closer than that of the

distiller. Brewers therefore assumed

leadership of the fight against the

ASL, chiefly through their trade

organization, the United States Brew-

ers' Association (USBA). Organized in 1862

as a result of federal gov-

ernment efforts to tax the brewing

industry, the USBA claimed credit

for establishing the excise tax system

which eventually resulted. From

taxation the USBA turned its attentions

to the technical side of product

improvement, which extended to such

areas as interest in upgrading the

raw agricultural products that went into

beer production. Labor condi-

tions also attracted USBA interest.

Brewers were somewhat unique in

being a highly unionized industry by

1900, and in dealing with one of the

few early industrially-organized unions,

the Brewery Workers of

America. Brewers were proud of their

generally peaceful and advanced

relations with their workers, including

a form of workmen's compensa-

tion in advance of state regulation on

the subject.22

Technology revolutionized the industry

in the late nineteenth cen-

tury, particularly the development of

refrigeration and the pasteuriza-

tion process for beer. Taken together,

they permitted beer to invade

areas far removed from breweries-rural

areas in general and the South

in particular. Beer could not only be

preserved for longer periods of

time, but with the development of the

modern glass bottle, it permitted

more widespread consumption at home

rather than at the saloon. Re-

frigeration more than doubled brewing

capacity, creating a potential for

over production, and sharpened

competition among brewers that even

the heightened waves of immigration of

the late nineteenth century

failed to blunt. One manifestation of

this overcompetitive situation was

brewer financing of large numbers of

saloons-their primary retail out-

let. Brewers later acknowledged ASL

charges that they financed

saloonkeepers' costs of procuring

equipment, fixtures, and even the

annual license fee; they denied,

however, that this gave them control

21. Ibid., 89-90, 97; Steuart, Wayne

Wheeler, 66-69; ASL, Yearbook: 1910, 243,1911,

30. According to the League, "it is

not only worthless but absolutely harmful to enact

prohibition in any state before public

sentiment on the liquor question in that state is strong

enough to maintain such a system. .

." (Ibid., 1912, 143).

22. U.S., Congress, Senate, Subcommittee

of the Committee of the Judiciary, Reports

and Hearings, Brewing and Liquor Interests and German

and Bolshevik Propaganda,

66th Cong., 1st Sess., 1919, I, 82-83

(hereafter cited as Brewing and Liquor Hearings);

USBA, Yearbook: 1909, 11; Nuala

Drescher, "The Workman's Compensation and Pen-

sion Proposal in the Brewing Industry,

1910-1912: A Case Study in Conflicting Self-

Interest," Industrial and Labor

Relations Review, 24 (October 1970), 32-46.

14 OHIO HISTORY

over the saloons. "All that the

brewer got out of his bargain was the

furnishing of his particular brand of

beer," complained an industry

spokesman to a United States Senate

investigating committee in 1919.

Saloonkeepers were free to dispense

whiskey and other goods and

services as they saw fit. Reformist

efforts to eliminate saloons by an

exorbitant annual tax were actually

counterproductive. They not only

made the saloon owner more dependent

upon the brewer for financing,

but frequently prompted the bartender to

offer such services as gam-

bling and prostitution in order to make

a living.23

Around the turn of the century the

campaigns of the Anti-Saloon

League prompted the USBA to devote an

increasing amount of its

attention to combating the movement

directed against the saloon. Prior

to that time brewers had experienced

success in thwarting statewide

prohibition. Such proposals had been

defeated in ten states; "in all these

instances," a USBA publicist

boasted, "the arguments used by the

opponents of Prohibition were derived

directly from our publications."

Only Kansas and Iowa had enacted

prohibition over brewer opposi-

tion.24

Yet the ASL posed a much stronger

challenge than anything previ-

ously encountered by the brewers, and it

required them to adopt different

tactics. The new approach embraced

efforts to win public sympathy, if

not support. For instance, the USBA

tried to separate beer and light

wines from more potent distilled

beverages in a public mind made

sensitive to alcoholism by ASL

propaganda. More importantly, brewers

began to compete directly with the ASL

for public support, particularly

that of opinion leaders. The USBA began

reprinting articles favorable to

its cause in pamphlet form, which it

turned over to its state and local

affiliates for distribution. Another

manifestation of this public aware-

ness program was the new look given the

annual USBA Yearbook

beginning in 1909. Whereas formerly the Yearbook

was intended solely

for industry consumption, the new Yearbook

"is designed both for the

convenience of our members and for the

information of the public." The

contents reviewed recent liquor laws and

included articles concerning

the brewing industry. "We have

aimed to make it a valuable reference

book," the editors declared-one

intended for public use. Hopefully the

deliberate absence of any copyright

would contribute to that end.25

In an additional attempt to counter the

ASL, the USBA adopted, at

23. Brewing and Liquor Hearings, I,

83, 91; USBA, Yearbook: 1911, 9, 164; Hatton,

"Liquor Situation in Ohio,"

418-419. For the impact of a high annual saloon tax, see

Frederic C. Howe, The Confessions of

a Reformer (Chicago, 1967), 51-55.

24. USBA, Yearbook: 1909, 13-16,

17.

25. Ibid., Preface; Brewing

and Liquor Hearings, I, 82-84.

Politics of Temperance 15

their annual convention at Milwaukee in

1908, a Declaration of Princi-

ples that admitted the existence of

faults within the industry, such as an

excessive number of saloons. "THE

EXISTING EVILS, HOWEVER,

CAN BE ERADICATED BY ACTION ON THE PART

OF INDI-

VIDUALS IN THE TRADE ONLY IF THEY ARE

AIDED AND

SUPPORTED BY PUBLIC SENTIMENT AND

SUITABLE

LAWS.... Not only were the brewers

"READY AND ANXIOUS TO

DO THEIR SHARE," but they expressed

a willingness to cooperate

with any movement "looking to THE

PROMOTION OF HABITS OF

TEMPERANCE IN THE USE OF FERMENTED

BEVERAGES."26

At least one USBA affiliate backed up

this rhetoric with action. In a

daring move to win public confidence and

to blunt ASL barbs, the Ohio

Brewers' Association established a

Vigilance Bureau in 1907 to police

saloons within the state. The brewers

sent a letter to every Ohio saloon-

keeper, calling attention to state

liquor laws and urging compliance. The

letter warned that the Vigilance Bureau

would investigate complaints of

improper activities, and would turn over

to local authorities any evi-

dence of misconduct. When necessary, in

fact, the Bureau hired detec-

tives to gather evidence and cooperated

with local prosecuting attorneys

in securing convictions. It may well be

that the Bureau prompted drys to

retaliate by securing legislation in

1909 permitting local authorities to

secure private detective assistance.

The Vigilance Bureau activities extended

to towns and cities all over

Ohio, including Canton, Dayton,

Cleveland, Chillicothe, and Cincin-

nati. In the last-named city, brewers

claimed credit for closing over one

hundred saloons despite lack of local

police cooperation. Henry T.

Hunt, the vigorous prosecuting attorney

in Cincinnati, acknowledged

the "effective and valuable

assistance from your [Vigilance] Bureau

toward securing evidence against saloon

keepers who permit gambling

on their premises and harbor

disreputable women."27

Ohio brewers followed up this movement

to upgrade saloons by

sponsoring the Dean Character law in

1909. The act required retail liquor

vendors to respond annually to a number

of questions, ascertaining

whether anyone connected with the

business was an alien or un-

naturalized citizen, or was ever

convicted of a felony. Furthermore, the

questionnaire asked whether the vendor

had, within the past year,

knowingly permitted gambling or the

presence of "improper females"

upon the premises, and whether the

retailer had knowingly sold liquor to

minors, drunks, or habitual drunkards.

Perjury, refusal to respond, or an

26. USBA, Yearbook: 1909, 147-148.

27. Ibid., 1909, 156-157, 1910,

136-142; Hatton, "Liquor Situation in Ohio," 420-421.

16 OHIO HISTORY

affirmative response to any single

question resulted in a fine and/or

imprisonment. In addition, the law

permitted the abatement of any

disorderly saloon upon the petition of

five voting taxpayers who lived

within one thousand feet of the

establishment. Should the defendant

request a jury trial, a "YES"

answer to any question on the character

inquiry constituted prima facie evidence

of a disreputable establish-

ment.28

The decision to embark upon this

counteroffensive entailed certain

risks, especially for the Ohio Brewers'

Association. For one thing,

neither the state nor the national

organization represented a majority of

the brewers even though USBA members

accounted for nearly two-

thirds of the total annual beer

production of the country. By contrast,

the Ohio affiliate represented only

forty percent of the state's output in

1910. There was the distinct danger

either that the Vigilance Bureau

could become an expensive but

ineffectual campaign, or that the impact

would fall disproportionately upon

retailers affiliated with association

members, and thus alienate them from the

organziation. Deliberately

closing outlets in an already

overly-competitive industry might have

seemed counterproductive to some.29

Secondly, some apparently deep-seated

animosities existed within

the liquor industry, as revealed in

congressional testimony during the

Great War. "For too many years

there has been an everwidening chasm

between the Brewer and the Retail Liquor

Dealer," asserted the presi-

dent of the National Retail Liquor

Dealers' Association in an address

before the USBA. Brewers reciprocated.

In a speech before the liquor

dealers' annual convention in 1910,

brewer lobbyist Percy Andreae saw

the prohibition movement as a joint

problem which necessitated joint

cooperation. A similar gap also existed

between retailers and wholesal-

ers. The former group, according to testimony,

had spent nearly a score

of years in building bridges between

them, resulting in the erection of

"substantial cables" across

the chasm.30 Vigilance Bureau activity

could well accentuate internal lines of

cleavage.

Despite these potential risks, it

appears that the counteroffensive was

successful in uniting the industry.

According to brewer sources, nearly

one hundred breweries cooperated in the

drive to clean up Ohio saloons,

suggesting that nonmembers of the state brewers'

association partici-

28. Hatton, "Liquor Situation in

Ohio," 413-415.

29. USBA, Yearbook: 1911, 30-31.

The Ohio Brewers' Association embraced fifty-six

members in 1910 and ranked second lowest

among thirty-three state affiliates in the

proportion of state production by

members; Ibid., 305.

30. Percy Andreae, The Prohibition

Movement in Its Broader Bearings Upon Our

Social, Commercial and Religious

Liberties (Chicago, 1915), 135; Brewing

and Liquor

Hearings, I, 91, 365.

Politics of Temperance 17

pated in the program. Furthermore, the Ohio Wine and

Spirit Associa-

tion joined the brewers in printing and distributing

broadsides to the

state's retailers informing them of the Dean Character

law provisions

and requesting their cooperation in ferreting out

offenders. The USBA

also formed two groups to overcome the decentralized

nature of the

organization, as well as to build upon existing bridges.

One such group

was the Interstate Executives' Association, comprised

of officers of the

national as well as state and local brewers'

associations. It was to serve

as a clearing house of information gathering and

dissemination in such

areas as trade problems, court decisions, and

legislative activities in the

various states. The second group was the Organizational

Bureau, estab-

lished in 1907 to take charge of the liquor campaigns

in state wet-dry

contests.31

The impact of the counteroffensive reached beyond

solidifying indus-

try ranks and began to tip the balance in the

prohibition movement in

Ohio. "At the present time," Cleveland

reformer Augustus Hatton told

fellow members of the National Municipal League in

1910, "there are

indications that the wave of prohibition which has

swept over Ohio has

reached its maximum. In fact," he warned, "it

will require strenuous

work for the anti-saloon forces to retain all that they

have gained."32

Evidence underscores Hatton's assessment. For example,

Table 2,

TABLE 2

Liquor Dealers and Brewers In Ohio, 1907-1912

1907 1908 1909 1910 1911 1912

Retail Liquor Dealers* 13,616 13,655 12,523 11,630 12,264 13,937

Wholesale Dealers 351 401 362 317 367 370

Retail Dealers

Malt Liquor 306

261 199 339

247 273

Wholesale Dealers

Malt Liquor 661 624 522 418 405 687

Brewers 143 125 119 122 113 125

SOURCE: USBA Yearbook: 1909. p. 88, 1910, p.289,

1911, Appendix Table G, 1912,

Appendix Table G, 1913, p. 293.

*Probably includes some druggists, who were permitted

by law to dispense alcohol

upon physician's prescription. The USBA, for example,

gave the number of saloons in

January 1910 as 6,908 and as 7,097 in 1911.

31. USBA, Yearbook: 1911, 29-30, 208-210; Brewing

and Liquor Hearings, I, 327.

Testimony on the role of the Organizational Bureau in

Ohio is conflicting. One witness

asserted that the Bureau limited its activities in the

Buckeye State to an advisory role; but a

memorandum of the Bureau claims considerable credit for

the election of Governor

Harmon in 1908. See Brewing and Liquor Hearings, I,

404, 836.

32. Hatton, "Liquor Situation in Ohio," 421.

18 OHIO HISTORY

which provides some rough indicators of

the state of the liquor trade in

Ohio, suggests a general pattern of

liquor decline through 1909, reflect-

ing in part the impact of the Rose law

county option elections beginning

the previous year. After 1910, the

pattern is reversed, showing an

expansion in the number of those

connected with liquor marketing. This

expansion, in part, reflects a series

of reversals experienced by dry

forces in succeeding Rose law

elections. Beginning in 1911, counties

which had balloted initially on the

subject were eligible to hold another

election, and many of them did so. In

the eleven-month period, begin-

ning July 1, 1911, eighteen of

twenty-seven dry counties which held their

second election returned to the wet

column. In the only new election in

the period, the county voted dry. On

the town and township level in the

same period, the results were more

evenly split; yet even these returns

reflect a distinct change from the

general ASL successes of the pre-1909

era.33

The brewer drive to clean up the saloon

not only met with a favorable

outcome, but it placed drys on the

defensive. In explaining the county

election reversals of 1911 an

Anti-Saloon League editor conceded the

defensive posture forced upon them by

wets "through promises to

install so-called 'well-regulated

saloons' devoid of the objectionable

features connected with the saloons

that were voted out under the

county law in 1908."34 Ohio

citizens were witnessing the anomalous

situation of both antagonists

operating in parallel fashion, and although

the ASL could boast that some two

thousand saloons had been

abolished by 1910, it could no longer

take sole credit for the result.

Furthermore, brewer invitations seeking

ASL assistance in ferreting out

unscrupulous establishments placed drys

on the horns of a dilemma.

Acceding to the offer would compromise

ASL objectives of eliminating

the commercial traffic in alcohol;

while refusal to cooperate would

expose the League to charges of

hypocrisy. When the ASL countered

with a proposal of joint efforts to

eliminate bootleggers in dry areas, the

Vigilance Bureau superintendent

declined. " 'Dry' territory is the

peculiar property of the Anti-Saloon

League," he observed. "The Vigi-

lance Bureau has the right on the mere

face of the thing to assume that its

responsibility ends where local option

begins."35

Finally, although both agencies utilized

private detectives to expose

liquor law violators, Vigilance Bureau

efforts met with generally favor-

able reaction. By contrast, such

practices backfired at least once for the

ASL in the form of the so-called Newark

riot of 1909. When Licking

33. USBA, Yearbook: 1912, 106-107.

34. ASL, Yearbook: 1912, 184.

35. Quoted in USBA, Yearbook: 1911, 60.

Politics of Temperance 19

County voted dry in a Rose law election,

the outcome not only

threatened the existing saloons in the

county seat of Newark, but it

jeopardized the livelihood of some of

the two thousand men employed in

a beer-bottle factory. Speakeasies

continued to flourish with the indif-

ference if not connivance of local

authorities. Drys appealed to the state

ASL for relief. A nearby village mayor

granted search and seizure

warrants to ASL detectives, but when

they attempted to serve them in

July 1910, a mob assaulted them. The

crowd chased one, a nineteen-

year-old, over two miles and beat him.

In self-defense, the youthful

detective shot and killed one of his

assailants, a saloonkeeper. The

detective was arrested, jailed, and

later hanged by a mob which broke

into the jail and dragged him out. It

required state troopers sent in by the

governor to restore order. Despite

League efforts to portray the incident

as solely the result of the liquor

traffic, Licking County voted wet in the

second Rose law election in January

1912.36

It was at this point that the liquor

controversy spilled over from the

legislative halls and judicial chambers

into the Ohio Constitutional Con-

vention, which assembled at Columbus in

January 1912. Although the

convention was primarily the result of

efforts by the Ohio State Board of

Commerce, who wished to alter the tax

structure of the state, other

pressure groups also saw in the

convention a way to circumvent legisla-

tive obstructions to their respective

goals. Among the most active were

backers of the initiative and referendum

(led by advocates of the single

tax), woman suffragists, and those

active in the liquor controversy.37

At least two factors assured a prominent

role for the liquor question in

convention deliberations. First, once

voters approved the calling of a

constitutional convention in a 1910

referendum, the enabling act permit-

ted candidates for the 119 delegate

positions to declare whether or not

they supported a separate submission of

the liquor licensing question in

the convention. Many candidates, either

by conviction or as the result of

pressure applied by partisans of the

issue, took advantage of this oppor-

tunity. Further, the second round of the

county option elections began

by mid-1911. Not only did these Rose law

elections keep the liquor issue

36. Hatton, "Liquor Situation in

Ohio," 400-401; Cincinnati Enquirer, January 7, 1912.

For an "eyewitness" account of

a rather bizarre county option election in Chillicothe, see

USBA, Yearbook: 1911, 194-195.

37. The 1912 Ohio Constitutional

Convention is surveyed by Hoyt Landon Warner in

his Progressivism in Ohio, 1897-1917 (Columbus, Ohio, 1964), Ch. 12.

For a more detailed

analysis, see Lloyd Sponholtz,

"Progressivism in Microcosm: An Analysis of the Political

Forces at Work in the Ohio

Constitutional Convention of 1912" (unpublished Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Pittsburg,

1969).

20 OHIO HISTORY

before the public consciousness, but the

two-to-one ratio of wet vic-

tories encouraged brewers to press their

offensive further by seeking

adoption of a liquor license amendment

to the constitution. In that way

the legitimacy of the liquor trade would

be constitutionally established

and efforts to police the traffic

enhanced.

The Anti-Saloon League remained on the

defensive by working to

maintain the constitutional status quo,

fearing that any tampering with

the state's charter might undo their

progress to date. An ASL editor

aptly set the tone for the forthcoming

convention. "The struggle of 1912

between the temperance and liquor forces

will unquestionably be the

most desperately fought contest in which

these forces in the State of

Ohio have ever been engaged," he

observed grimly. "Whatever may be

the result in this specific contest, the

war will continue until there has

been established a permanent sentiment

in the state which will no longer

tolerate the liquor traffic."38

Because of its power of life-and-death

over any proposal involving the

question of liquor, the Liquor Traffic

Committee ranked among the most

significant of the convention. It was

one of the few to number twenty-

one members, and its composition was

watched with keen interest. Drys

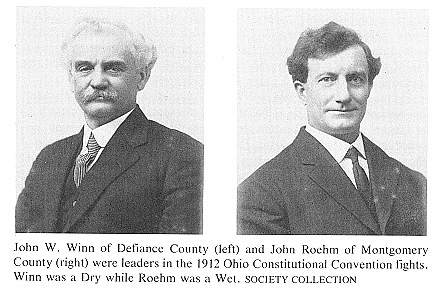

were represented by former state

representative John Winn, who had

authored one of the local option laws

passed by the general assembly, by

Professor Henry Elson of Ohio

University, a former Lutheran theolo-

gian and ardent prohibitionist, and by

William Kilpatrick, who had

recently resigned from the general

assembly in order to serve in the

convention. Kilpatrick was the author of

an equal suffrage proposal

currently favored by the Equal Suffrage

Committee. Wets could count

upon John Roehm, an officer of the Ohio

Personal Liberty League, and

Republican Judge Edmund King from

Sandusky, where the manufac-

ture of liquor was an important

industry.

Within the first month the committee

received over a dozen proposals

from delegates embracing a spectrum that

ran from a choice between

prohibition or license, through various

degrees of restrictive license, to a

license/no-license option. Both wets and

drys made their positions

perfectly clear. Brewer and liquor

retailers preferred a constitutionally

mandatory license system, but one that

would leave the details of license

38. Steuart, Wayne Wheeler, 70;

Cincinnati Enquirer, August 4, 1911; ASL, Yearbook:

1912, 184. A speech by USBA secretary Hugh Fox in 1910 or

1911 also shows the

organization's adoption of the license

idea, as well as a sensitivity to public relations.

Brewers, according to Fox, should pay

atttention to the saloon's physical appearance.

Attract laborers with "clean white

tiling on the walls; clean white glass beer counter; clean

floors and plain but comfortable

furniture." Remove screens, he urged, and open the

"premises to public scrutiny"

(USBA, Yearbook: 1911, 149-165).

|

Politics of Temperance 21 |

|

|

|

restriction to the general assembly. Brewer lobbyist Percy Andreae, in testifying before the Liquor Traffic Committee, blamed temperance forces for depriving the saloon of its only protection against disreputable elements, which would be a license imposing character restrictions upon the number and character of proprietors and patrons. "In asking for a license law," Andreae asserted of his clients, "they are not asking for greater freedom, but for greater restriction: they are not demanding of you a privilege, but a beneficent protection . .."39 Retailers, too, envisioned state regulation of the liquor trade and supervision of the license applicant's character: with "no doubt something in the shape of a special commission empowered to limit the number of saloons in ratio to population."40 By contrast, the Anti-Saloon League "has been, is now, and always will be opposed to licensing liquor traffic.'' Yet, sensing a good possibil- ity of convention endorsement of a licensing system the League prag- matically suggested that the license "be made permissive instead of mandatory and let it also be hedged about with such restrictions and regulations . . . such as forfeiture of license, limitation of the number of

39. Percy Andreae, "Argument on Constitutional License," made before the Liquor Traffic Committee of the Ohio Constitutional Convention, 1912, in his The Prohibition Movement, 187, 195. 40. Liberal Advocate, January 10, 1912. This weekly newspaper was the official organ of the Ohio Liquor League. |

22 OHIO HISTORY

saloons, prohibition of brewery-owned

saloons, etc ...." Furthermore,

should such a license proposal be

referred to the voters, the League

favored an alternative choice that

would prohibit all liquor traffic out-

side of the state's five largest

cities. Wayne Wheeler conveyed the

League's position to the Liquor Traffic

Committee.41

As it turned out, Andreae and Wheeler

established the parameters of

the convention's consideration of the

liquor question. On February 12

the Liquor Traffic Committee, by a

close vote of twelve to nine, en-

dorsed Judge King's proposal. King

presented voters with a choice of

the current no-license situation or an

unrestricted license which allowed

the general assembly to regulate the

traffic while retaining the local

option laws then in force. John Winn,

on behalf of the minority, reported

a proposal imposing strict limitations

upon a license system, including

one restricting saloons to one per one

thousand population. Over two

weeks of debate ensued, after which the

weary delegates killed all

proposals and started anew.42

All later proposals submitted to the

convention called for varying

degrees of restricted license. The

proposals and amendments indicate

that some informal agreement had been

reached. All called for a voter

choice between some form of restricted

license and a continuation of the

no-license status quo, and all provided

that the issue was to be submitted

to the voters separately from other

proposals. Furthermore, delegates

insisted that the licensee be an

American citizen of good moral character

who had no other liquor interests.

There were a number of key points at

issue. One concerned the proper

ratio of saloons to population.

Although strict regulationists favored a

limitation of one saloon per one

thousand population, the ratio of one per

five hundred was more commonly

accepted. The Anti-Saloon League

took great delight in the obvious

discomfiture of the liquor retailers over

the considerable reduction in the

number of saloons that would result,

estimated by retailers at twenty-five

hundred.43 Closely related was the

number of infractions to be tolerated

before a license would be revoked;

hard-liners fought for a maximum of one

liquor law violation. A third

area of controversy involved the degree

of latitude to be granted cities.

The liquor industry had chafed under

the Rose law because of the

coercive potential of rural areas to

outvote-and thus dry up-towns. "I

41. American Issue (Ohio

edition), January 27, 1912; Steuart, Wayne Wheeler, 70. See

also ASL, Yearbook: 1909, 176.

Unless otherwise indicated, all future references to the

American Issue are from the Ohio edition.

42. CC Debates, I, 249-250, 353,

542-543; Royal D. Frey, "The Ohio Constitutional

Convention of 1912" (unpublished

M.A. thesis, Ohio State University, 1950), 23-27.

43. Liberal Advocate, March 6,

1912; American Issue, March 16, 1912.

Politics of Temperance 23

have nothing to say against local

option," Percy Andreae told an Ohio

legislative committee on temperance.

"What I assert is that county

option is not local

option." Remembering the Newark riot several years

before, a liquor editor pleaded for

local administration of the law "in-

stead of an army of mercenary desperados

. . . financed by the Anti-

Saloon League and let loose upon these

communities, armed, blood

thirsty, reckless and

murderous..."44 The League, of course, feared

that such latitude would thwart the

eventual goal of statewide prohibi-

tion.

Proponents of home rule in liquor

licensing would permit municipal

corporations and townships to determine

the number of saloons and to

provide for the collection of license

fees, exempting those areas already

dry under one of the various local

option laws. Yet there were limits

here, too: delegates refused to exempt

cities totally from saloon limita-

tion, as proposed by two delegates from

Toledo and Cincinnati respec-

tively.45

Once delegate sentiment swung to saloon

limitations, wets sought to

soften the blow. One proposal sought to

reduce the number of saloons to

the prescribed ratio gradually, giving

existing saloonkeepers prece-

dence over other license applicants.

Furthermore, brewers and

wholesalers would be exempt from the

license provisions. The latter

groups especially aroused the wrath of

the ASL, which took the view

that those subject to liquor tax

payment should be included in the

limitations. Wholesalers "sell to

blind tigers and the bootleggers," the

League charged. "These houses have

to pay the Aiken tax and there is

no reason why they should be exempted

from the limitation clause."

Predictably, the League also opposed

any idea of providing compensa-

tion for saloons in excess of the

ratio, as had been suggested in the 1911

legislative session, nor did they favor

exempting resort areas from the

limitation clause.46

The proposal finally adopted called for

separate submission of no-

license versus a restricted license.

The license alternative called for a

mandatory limitation of one license per

five hundred population, allow-

ing municipalities to determine

individual limits within this framework.

A licensee had to be an American

citizen with a blameless record and

44. Percy Andreae, "Address before

the Committee on Temperance of the Ohio House

of Representatives in Support of Dean

Amendment to Rose Law," in his Prohibition

Movement, 153; Liberal Advocate, February 28, 1912.

45. CC Debates, I, 571-572, 596; Columbus Ohio State Journal, April

3, 1912; Dayton

Journal, March

5, 1912.

46. CC Debates, I, 975-978;

Liberal Advocate, April 3, 10, 1912; American Issue, April

13, May 18, 1912.

24 OHIO HSITORY

with no other liquor interests. This

latter clause was designed to prevent

ownership of saloons by breweries which

at that time owned or con-

trolled an estimated seventy percent of

the nation's saloons. In order to

preserve local control over liquor, the

licensee was required to live in the

same county as that in which his license

was issued, or in an adjacent

county. Lastly, the proposal defined a

saloon (the word "saloon" was

deliberately inserted by amendment) as

an establishment selling liquor

as a beverage in quantities less than

one gallon, thus in effect exempting

wholesalers.47

Because the end product represented a

compromise, it is difficult to

assess the relative success of the

antagonists. Both wets and drys

claimed victory. "The Anti-Saloon

League believes that so far the

temperance forces have held their own

and it is equally confident the

brewers are not satisfied with their own

child." Not so, the liquor

retailers replied; they summed up the

moral effect as "a victory for the

liberal element and a defeat for the

prohibition and Anti-Saloon

Leaguers," although it would work a

hardship "upon hundreds of

reputable men in the trade."48

Superficially, both claims appear valid.

Except for the saloon limita-

tion figure, the proposed amendment

differed little from what Percy

Andreae and the brewers had been

advocating for the previous few

years. By the same token, the provisions

sound very similar to the

recommendations put forward by Wayne

Wheeler in his testimony

before the Liquor Traffic Committee.

Each settled for less than the

optimum. The League conceded prohibition

in favor of apparent strin-

gent regulations; while liquor men

swallowed constitutional regulation

instead of the more flexible legislative

control in order to achieve their

goal of license.49

Taken within the broader context, it

appears that the balance tipped in

favor of the wets. Not only had they

again thwarted further dry en-

croachments by at least legitimizing

their trade, but by building upon

their recent county option electoral

successes they had transferred their

self-improvement campaign to the public

sector by securing constitu-

tional sanction for their efforts. In

addition, the legislature retained the

right to establish the specifics of the

licensing system, in terms of

47. CC Debates, II, 1807.

48. American Issue, March 16,

1912; Liberal Advocate, March 6, May 29, 1912.

49. Cincinnati Enquirer, February

6, 1912.

Politics of Temperance 25

determining the composition of the

licensing board(s), and the degree of

centralization within the system.50

The ultimate attitudes of both sides

toward the proposal underscores

this wet victory. By the end of June the

liquor forces backed up their

claims of satisfaction with endorsement

of the liquor license proposal by

the Ohio Brewers' Association and by the

Ohio Retail Liquor Dealers'

Association. Meanwhile the League lamely

sought the sentiment of its

readership on the license proposal. At

the end of June, the American

Issue reported that sentiment was running forty to one in

opposition.

The results allowed the League to

reverse its rhetoric and to oppose

license in the referendum campaign that

summer.51

The liquor license question was only one

of forty-two proposals

endorsed by the constitutional

convention. Compared to some of the

other issues, license maintained a low

profile in press coverage pre-

paratory to the September 3 special

election on the amendments. Pro-

posals such as those governing taxation,

labor, the initiative and referen-

dum, and woman suffrage captured voter

attention. The referendum

outcome extended this placid appearance.

Although license was among

the thirty-six proposals receiving voter

approval, it ranked last in the

number of total votes cast on any issue.

Its place on the ballot may have

contributed to this outcome. Not only

was license the last of the forty-

two proposals in order of appearance,

but it was located in a separate

column on the long, single ballot.

Oversight and voter fatigue might have

complemented absence of controversy

preceding the election.52

Such tranquility was short-lived in

Ohio. Far from resolving the liquor

question, the constitutional

convention's actions seemed to have fueled

the fires of this simmering issue. By

delegating to the legislature the task

of establishing a liquor license system,

the 1913 session of the general

assembly found itself embroiled in a

bitter controversy between wets

and drys as each sought to gain an

advantage. Then, too, voter adoption

of the initiative and referendum in 1912

permitted both sides to take the

issue directly to the voters almost

annually. Within a year wets submit-

ted a constitutional amendment aimed at

eroding rural prohibitionist

50. Liquor retailers saw the legal

recognition of the trade as the chief advantage; see

Liberal Advocate, May 29, 1912.

51. Liberal Advocate, July 3, 1912;

American Issue, June 29, 1912; USBA, Yearbook:

1912, 106; Steuart, Wayne Wheeler, 70-72.

52. Woman suffrage received the greatest

number of votes in suffering defeat-over

586,000 ballots. Liquor license was

approved by a vote of 273,361 to 188,825-an aggre-

gate vote about 124,000 less than woman

suffrage. See Ohio, Secretary of State, Annual

Report: 1912 (Columbus, 1912), 668-669. Voter turnout at the special

election was some-

what light-slightly less than half of

that of the November 1910 general election.

26 OHIO HISTORY

influence in the Ohio general assembly

by reducing the size of the lower

house. This unsuccessful effort led to

attempts in the next few years to

insure urban wet oases by providing

constitutional home rule on the

liquor question, and by restricting the

number of times drys could

submit prohibition amendments, which the

ASL had sponsored in 1914,

1915, and 1917. In addition to these

activities by the protagonists,

woman suffragists indirectly inserted

the temperance issue into the

public arena through their efforts to

secure the vote by initiative in 1914

and 1917.

It would exaggerate the significance of

the Ohio controversy over

liquor to say that failure to forestall

constitutional license in 1912 promp-

ted the Anti-Saloon League to embark

upon a campaign for a federal

prohibition amendment the following

year. There is no reason to doubt

the League's own explanation of this

decision as having been "hastened

by the passage of the Webb interstate

shipment law over the veto of the

president," Woodrow Wilson, which

indicated "a strong and favorable

congressional interest in the subject of

Prohibition."53 At the same time,

the Ohio experience could certainly call

into question Joseph Gusfield's

assertion that "from a number of

standpoints the drive for national

Prohibition, which began in 1913, was an

inexpedient movement."54

The record in Ohio strongly suggests

that the liquor industry had

mounted a successful counteroffensive

and that drys were losing

ground. The "equable

arrangement" described by Gusfield was en-

dangered by wet legislative and

electoral victories and in effect

suggested the natural parameters of wet

and dry territory as determined

by local popular commitment to

temperance.55 Should the liquor indus-

try have been successful in rejuvenating

the respectability of the saloon,

and should the "Ohio plan" of

self-regulation have spread to other

states, dry gains might also have faced

erosion.

In view of that possibility, and given

the increasing urban composition

of the nation's population-it was the

urban vote which repeatedly

defeated Ohio prohibition amendments-it

seemed politic for the ASL

to take advantage of rural

over-representation in Congress and to work

for national prohibition. Furthermore,

ratification of federal amend-

ments was also by rural-dominated state

legislatures. The issue would

53. New Republic, May 16, 1913.

54. Joseph Gusfield, Symbolic

Crusade: Status Politics and the American Temperance

Movement (University of Illinois Paperback, 1972), 109.

55. Ibid.

Politics of Temperance 27

never confront voters directly; urban

hostility as expressed in Ohio

could be successfully muted. Thus the

temperance movement in Ohio, if

not instrumental in national ASL

policy-making, certainly reinforced

their decisions. The apparent reversal

of the dry pendulum in Ohio

raises intriguing questions about the

temperance record in other urban-

industrial states, and it elevates the

possible role of the Great War with

its attendant nativism and sense of

national emergency as contributing

factors toward enactment of the

Eighteenth Amendment.56

56. The role of the Great War in

stimulating national prohibition is analyzed by Andrew

Sinclair, Era of Excess: A Social

History of the Prohibition Movement (New York, 1964),

116-28.