Ohio History Journal

JAMES H. LEE

The Ohio Agricultural

Commission, 1913-1915

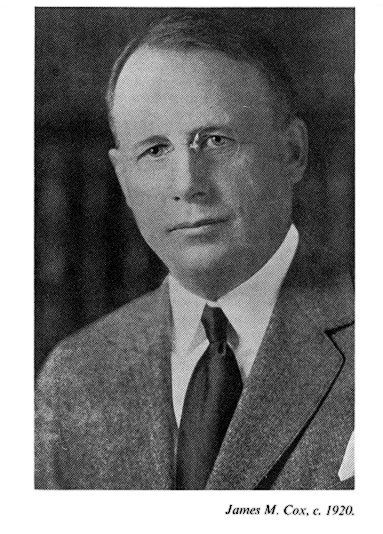

When James M. Cox assumed the

governorship for the first time, in 1913, Ohio

agriculture was passing through a period

of rapid transition. The demographic

expansion of the late nineteenth century

had inflated land values and crop prices,

a trend which converted agriculture into

a potentially highly profitable enterprise.

Ohio farmers responded by gradually

transforming themselves into rural business-

men; they specialized, developed more

efficient managerial techniques, and utilized

more intelligently the total resources

of their farms.1 This transformation of farm-

ing was accompanied by the expansion of

government activities designed to aid

agriculture. The State Board of

Agriculture, created in 1846 as an information

agency for farmers, had by 1910 assumed

considerable responsibility for the regula-

tion and promotion of agriculture in

Ohio. The board, in addition to collecting and

disseminating crop and cattle

statistics, also enforced plant and stock quarantine

laws and regulated the sale of

fertilizers and foodstuffs within the state.2 These

developments in agriculture, and

parallel ones in other sectors of the economy,

often generated jurisdictional

conflicts, duplication of activities, and confusion in

government since the state had assumed

new responsibilities for regulating and

promoting economic development, but its

administration was rather haphazard.

This was the situation when James M. Cox

entered office in January 1913. The

new governor hoped to eliminate these

problems by introducing into government

the principles of efficiency that

businessmen had developed over the years. Success

in this pioneer endeavor depended in

large part, he believed, on the consolidation

of government bureaus, to avoid waste,

and on the selection of trained experts to

staff the reorganized agencies. Soon

after entering office, therefore, Cox introduced

in the legislature a broad program of

administrative reorganization.3

The agricultural section of Governor

Cox's reform program was embodied in a

bill passed April 15, 1913, creating the

Ohio Agricultural Commission. Cox pro-

1. W. A. Lloyd, J. I. Falconer, C. E.

Thorne, The Agriculture of Ohio, Bulletin 326 of the Ohio

Agricultural Experiment Station

(Wooster, 1918), 15.

2. Robert Leslie Jones, "Ohio

Agriculture in History," Ohio Historical Quarterly, LXV (July

1956),

254-255; General Code of Ohio, 1910, Part

1, p. 231, 232, 233, 239, 241.

3. James M. Cox, Journey Through My

Years (New York, 1946), 137. Cox's views are set forth in

his first message to the General

Assembly in 1913, see James K. Mercer, Ohio Legislative History,

1913-1917 (Columbus, 1918), 30-58.

Mr. Lee is a doctoral candidate in

history at The Ohio State University.

|

|

|

posed that the new bureau coordinate the activities of the State Board of Agricul- ture, Board of Control of the State Agricultural Experiment Station, the State Dairy and Food Commissioner, the State Board of Veterinary Examiners, the Commission of Fish and Game, and, to a lesser extent, the State Board of Pharmacy. The new commission's duties would thus extend beyond the scope of strictly agriculturally related activities and would include enforcement of hunting and fishing laws, ap- pointment of members to the Board of Veterinary Examiners, and application of the pure food and drug laws. Unlike the 1908 amended law relating to the Board of Agriculture, the members of the commission could not be removed by the gov- ernor, but only by provisions of the law; the commission was to have four full-time paid members that would hold office for six years rather than have ten members who were paid only their expenses and worked on a part time basis; but both laws limited membership to persons directly identified with agriculture or agricultural education.4 Public reaction to the bill was somewhat mixed, as of February 17, before final amendments were added. The editor of the Cleveland Plain Dealer hailed the pro- 4. Laws of Ohio, XCIX, 592a-592c; CIII, 304-341. |

Agricultural Commission 221

posal as a significant step toward the

introduction of efficiency into this branch of

government service.5 The

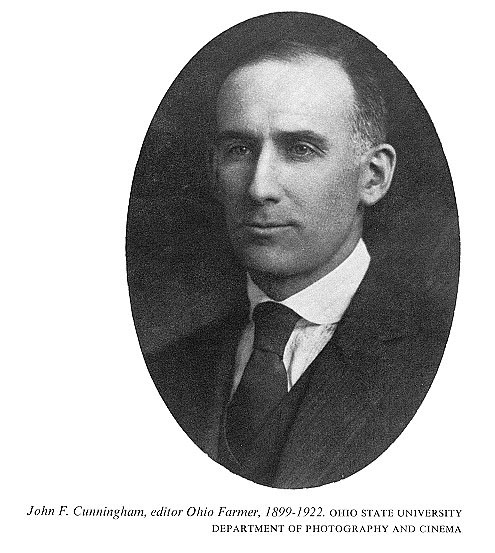

editors of the prestigious Ohio Farmer, on the other hand,

cautiously questioned the advisability

of the plan. They favored coordination of the

state's agricultural activities in order

to eliminate duplication but felt that the best

way to achieve such efficiency was

through creation of an advisory commission

composed of the heads of the state

agricultural institutions. The editors, who were

spokesmen for the Ohio farmers, also

questioned the ability of such a small group

of men that would head the commission to

handle competently the disparate respon-

sibilities assigned them in the

legislation, especially in view of the fact that the bill,

as originally submitted, established no

qualifications for members of the commission.6

Other rural elements also raised

objections to Governor Cox's reorganization

plan. Many farmers were simply reluctant

to abandon a familiar and, to them,

satisfactory system of management,

especially in favor of one that initially would

cost more to operate.7 Furthermore,

during a period when laissez faire attitudes

were still quite strong some farmers, at

least, regarded the agricultural bill as part

of a concerted effort to centralize

excessive power in the traditionally rather weak

office of the governorship.8 Probably

the most important single reason that many

rural leaders, especially the executive

council of the Ohio Grange, opposed the

governor's plan was the related fear

that it would lead to the injection of politics

into the state agricultural

institutions.9 This concern undoubtedly arose in part from

the fact that the bill originally

established no qualifications for membership on the

commission, that jurisdiction of the

agricultural educational institutions would be

divided between the commission and the

institutions, and from the conviction that

the considerable power and generous

salaries attached to the office of commissioner

would attract ambitious politicians.

These considerations help explain the Grangers'

satisfaction with the old part-time

unsalaried Board of Agriculture--an arrange-

ment which ensured the farmers that

control over agricultural policy would remain

in the hands of actual farmers and that

only truly dedicated men would seek mem-

bership on the board.10

Other groups that the reorganization

proposal affected were also disturbed over

the prospect of losing some or all of

their board's autonomy. Some veterinarians

were disturbed because they thought they

would lose control over appointments to

their board of examiners, which power

was transferred to the commissioners in

the Cox bill. At its annual meeting the

Ohio State Veterinary Medical Association

issued a statement that indicated the

basis of its opposition to the Cox plan: "We

feel that the veterinarians of this

state should have some voice in the selection of

the personnel of that office [the board

of examiners], because certificates should be

5. Cleveland Plain Dealer, February

17, 1913. While criticizing the Grange's opposition to the bill,

both the Ohio State Journal (Columbus)

and the Cincinnati Enquirer endorsed the measure, the form-

er's endorsement being unqualified while

the latter's was somewhat critical of Cox. Ohio State Journal,

March 6, 1913; Enquirer, May 4,

1913.

6. Ohio Farmer, February 1, 1913, p. 136; February 22, 1913, p. 202;

March 1, 1913, p. 296; March

8, 1913, p. 346.

7. This was implied by the Master of the

Grange in his speech to that organization's annual con-

vention in 1913. Journal of the

Proceedings of the Ohio State Grange (Lima, 1913), 16, 17. The editors

of the Ohio Farmer also shared

this sentiment; see March 8, 1913, p. 346.

8. See R. H. Triplett to James M.

Cox, March 8, 1913, Cox Papers, Ohio Historical Society. Triplett,

while he opposed Cox's efforts to increase

the power of the governor, was nevertheless a Democrat.

9. Ohio State Journal, March 13, July 15, 1913; Journal, Ohio State Grange (1913),

16, 17; Cox to

M. J. Lawrence, May 31, 1913, Cox Papers.

10. This point was made explicitly by

the editors of the Ohio Farmer in March 8, 1913, p. 346.

222 OHIO

HISTORY

granted only to those who are eminently

qualified and not to pay political debts."11

Also, in June 1913, Dr. Louis P. Cook,

Democrat state senator from the first dis-

trict in Cincinnati and ex-president of

the Ohio State Veterinary Medical Associa-

tion, sent out form letters to the

state's veterinarians opposing the law that had

just been passed and supporting a

referendum campaign started by the Ohio State

Grange. His opposition was based on the

ground that "the State certificates to

practice Veterinary Medicine will be in

the hands of machine politicians. . . . A

certificate will be issued to every

quack who has a political pull."12 These remarks

were made even though the law

specifically stated that "The agricultural commis-

sion shall appoint three men who shall

be graduates of reputable, but different,

veterinary schools or colleges, and . .

. skilled in their professions. . . ." to conduct

the qualifying examinations, and that

the applicant must pass a written examina-

tion covering specified subjects with a

grade of seventy percent or better.13

Similar considerations prompted

pharmacists to question certain provisions of

the Cox agricultural commission law. In

their case it removed the Pharmacy Board's

power to enforce the laws against sale

of drugs by persons lacking a pharmacist's

license.14 By including the

Pharmacy Board in the Agriculture Commission, the

commission assumed responsibility for

the protection of druggists in the control

of illicit sale of drugs, but it had no

authority over the licensing of pharmacists.

Even so, a highly respected member of

the profession, Dr. J. H. Beal, echoed the

sentiments of many pharmacists when he

declared several years later that "I have

never believed that the laws relating to

pharmacy and medicine should be enforced

by an agricultural commission composed

wholly of farmers. To my mind, there

would be just as much, or even greater,

reason for giving the Board of Pharmacy

the right to administer the laws which

related particularly to agriculture."15

The veterinarians and pharmacists,

however, lacked the numerical and organi-

zational strength to threaten seriously

the commission plan, but Governor Cox

could not ignore the widespread

discontent in rural areas over certain provisions

in his original bill. He consequently

called a conference of agricultural leaders to

iron out the difficulties. A committee

of four of these men introduced into the bill

the changes they thought were necessary,

and the governor accepted all of the

important amendments. One of the most

significant of these alterations required,

before the April passage of the bill,

that all members of the commission be men

"directly identified with

agriculture or agricultural education." This stipulation,

coupled with the recent enactment of a

state civil service law, seemed to eliminate

the danger that "politicians"

would gain control of the state agricultural institutions.

In return for this accommodation Cox

secured the pledge of the farm leaders not

to further oppose passage of the bill.16

The attitude of these men understandably

convinced the governor that his

consolidation plan, also, would encounter no fur-

11. Proceedings of the Ohio State

Veterinary Medical Association (1914), 59.

12. Louis P. Cook to "Dear

Doctor," June 23, 1913, Cox Papers.

13. Laws of Ohio, CIII, 328.

14. Ibid., 306.

15. Midland Druggist and Pharmaceutical Review, XLIX (June 1915),

260.

16. John Cunningham to M. J. Lawrence,

June 4, 1913; clipping from July 5, 1913 issue of the

National Stockman and Farmer, both in Cox Papers (Cunningham was not the senate sponsor

of the

bill but editor of Ohio Farmer, and

Lawrence was publisher of the journal); Ohio Farmer, March 22,

1913, p. 423. W. I. Chamberlain,

associate editor of the National Stockman and Farmer, was present at

the conference of agricultural leaders and

Cox. He claimed that T. C. Laylin, Master of the Grange,

pledged not to oppose passage of the

bill, but Laylin's later opposition, culminating in a referendum

movement, demonstrates that he was never

reconciled to the bill, even in its amended form.

Agricultural Commission 223

ther opposition from rural groups.

"You have doubtless noticed that the farmers

who were opposed to the Agricultural

Commission have endorsed it," he wrote in

response to a letter from an

antagonistic farmer. "They came here in a two or

three days' session, and the bill was so

changed in shape as to meet their cordial

endorsement."17 Even the

editors of the Ohio Farmer agreed that, in its amended

form, the bill was generally acceptable

to agricultural interests.18 Not surprisingly,

therefore, both houses of the General

Assembly passed the measure by large

majorities.19

Governor Cox, nonetheless, continually

was made aware of persistent rural un-

easiness over the membership of the

commission. The bill's senate sponsor John

Cunningham informed him: "Several

parties have written to me, stating their con-

cern of the make-up of this important

commission and I have always assured them

that you had promised that no one would

be appointed who would be in any way

hostile to our State Agricultural

Institutions. . . ."20 The question of control of the

institutions had been one of the

principal reasons behind the amendment estab-

lishing qualifications for membership on

the commission. The governor sought to

banish the last traces of this concern

by appointing as commissioner A. P. Sandles,

former Secretary of the Board of

Agriculture; S. E. Strode, former Dairy and Food

Commissioner; and Professor C. G.

Williams, member of the staff at the Agricul-

tural Experiment Station. Williams had

been specificially mentioned as acceptable

by W. I. Chamberlain, associate editor

of the National Stockman and Farmer, and

by T. C. Laylin, Master of the Ohio

State Grange. The fourth member, Dean

Homer C. Prince of the College of

Agriculture, was appointed by the trustees of

the Ohio State University, as stipulated

in the law.21 The announcement of these

appointments helped to persuade the

Grange leaders to abandon the referendum

campaign, and by late July 1913 it was

clear that the Agricultural Commission

would get a trial period of operation.22

One year later, in April 1914, Governor

Cox declared optimistically, "Today . . .

there isn't a single person in Ohio who

denies that the coalition [of state agricul-

tural agencies] not only promoted the

efficiency of the service, but its economy as

well."23 Unfortunately

for the governor, this statement was not precisely accurate.

17. Cox to R. H. Triplett, March 18,

1913, Cox Papers.

18. Ohio Farmer, March 29, 1913,

p. 460.

19. Ohio General Assembly, House

Journal, 1913, p. 1021; Ohio General Assembly, Senate Journal,

1913, p. 387.

20. John Cunningham (state senator) to

Cox, April 29, 1913, Cox Papers.

21. John Cunningham (editor) to M. J.

Lawrence, July 30, 1913, Cox Papers. Cunningham did not

criticize the selection of Sandles and

Strode, but he, Lawrence, and the Grange leaders all thought

Williams was the best man. Of Sandles

and Strode, Cunningham wrote, in the letter cited, that ". . .

each man was appointed largely for

political reasons and neither can be said to be a real strong man

from the standpoint of agriculture. Both

are capable . . . but I cannot help feel that it is their own

interests that are uppermost in their minds rather than the

general cause of agriculture." (Emphasis is

in the original.) Cunningham, who was an

editor of the Ohio Farmer, would later make this charge

against Sandles publicly in the columns

of his magazine.

For the preference of Grange leaders for

Williams, see T. C. Laylin to Cox, July 3, 1913, Cox

Papers. Sandles was not himself a

farmer, although he had been involved in agricultural activities for

the state since 1902. Strode was a

farmer. Mercer, Ohio Legislative History, 1909-1913, p. 192, 205.

22. Cincinnati Enquirer, April

16, June 24, 1913; Representative William A. Hite to Cox, June 30,

1913, Cox Papers. The pharmacists,

despite their dislike of the law, decided not to join the referendum

movement, contenting themselves for the

present with drawing up amendments they hoped Cox would

accept. Ohio State Journal, June

30, 1913; Ohio Farmer, June 28, 1913, p. 782.

23. Ohio State Journal, April 25,

1914.

|

By February 1914, charges of inefficiency were already being leveled against the commission; other criticisms would soon follow.24 One of the principal reasons for creating the commission had been the desire to eliminate duplication of tasks by different agricultural institutions, but in Feb- ruary 1914 the editors of the Ohio Farmer began to accuse the commission of fail- ing to achieve this goal. Specifically, they charged that the commissioners were asserting partial control over agricultural extension education, an activity which before 1913 had been the responsibility solely of the College of Agriculture. The editors argued that the commission should confine itself to supervising in a general way the activities of the institutions under its control, rather than intervening in 24. The commission's report to the governor on its activities contains a record of the meetings of the commission, but that record is too skimpy to be of any value in assessing the performance of the agricultural bureau. Other sources, however, do provide some examples of clashes between the com- mission and private groups, such as the Cattle Breeders Association and the State Veterinary Department over a veterinary appointee and the conflict between the Ohio Farmer and the secretary, A. P. Sandles. See John Welty to Cox, October 12, 1914; Welty to George Burba, October 14, 1914; Burba to Welty, October 13, 1914; A. P. Sandles to Cox, December 8, 1914 (on the problem of diseased cattle), all in Cox Papers; and The Midland Druggist and Pharmaceutical Review, XLVIII (June, 1914), 244-249. |

Agricultural Commission 225

the details of their work. When the

popular and respected Professor A. B. Graham,

who was deeply involved in the

agricultural extension work of the college, resigned

his position in July 1914, the editors

of the Ohio Farmer claimed that the action

was a protest against the confusion and

conflict of authority resulting from the

commission's policy.25 The

commission's "interference" with the activities of the

College of Agriculture was not a minor

irritant in the view of these rural spokes-

men. The seriousness of the issue is

suggested by the frequency with which they

returned to the question.26 Their

concern was probably due in part to the conviction

that since agricultural progress

depended significantly on the educational activities

of the College of Agriculture and the

Experiment Station, these institutions should

be administered by educators and not by

politicians.

A second general charge which the

editors of the Ohio Farmer leveled against

the commission was that it had become

involved in politics. As early as January

1914, the editors accused Governor Cox

of trying to force farm institute lecturers,

who were under the Agricultural

Commission, to support his policies in their con-

tacts with farmers.27 Then,

in late 1914, without mentioning names, they criticized

the commission:

One commission (especially its president

and a few employes not members of the commis-

sion) has been devoting time to

political work that should have been devoted to the work

that the commission is supposed to do.

Not only has the literature of this particular com-

mission been made a sort of advertising

service for its president, but the men employed

to travel over the state, in some

instances, devoted too much time to partisan politics and

spreading statements that were probably

expected to be useful in future political campaigns.

In the following months, the editors

repeated their charges, although again in

vague, imprecise terms, and demanded

that control of the state agricultural activi-

ties be placed in the hands of actual

farmers who were not involved in politics,

men whose principal concern would be the

advancement of agriculture rather than

their own personal political fortunes.28

These rural spokesmen never explicitly

advocated abolishment of the commission,

but their editorials left little doubt that

they believed the experiment with the

Agricultural Commission had failed.

Grange leaders shared this conviction.

Despite the civil service law and the

amendment establishing qualifications

for membership on the commission, some

members of the executive council had feared

from the beginning that the com-

mission might become involved in

politics.29 Although the Grangers did not explic-

itly state that these fears had been

realized, at their annual convention in Decem-

ber 1914, they did demand that the state

return control of agricultural institutions

to actual farmers. They went further

than the editors of the Ohio Farmer, however,

and advocated decentralization of these

institutions and the re-creation of the old

non-salaried State Board of Agriculture.30

It is impossible to prove, but it seems

probable, that one reason the Grangers

advocated decentralization was their belief

that only in this way

could the farmers regain effective control over agricultural

25. Ohio Farmer, February 21, 1914, p. 244; July 11, 1914, p. 22-23; and

August 1, 1914, p. 78.

26. Ibid., January 9, 1915, p. 6.

27. Ibid., January 24, 1914, p.

98; January 31, 1914, p. 128. In the latter issue, the editors claim to

have received several letters from

readers supporting their position that the lecturers should not become

involved in politics.

28. Ibid., November 14, 1914, p.

444; January 9, 1915, p. 34; January 23, 1915, p. 94.

29. This can be inferred from the speech

of Grange Master, T. C. Laylin at the Grange's annual

convention in 1913. Journal, Ohio

State Grange, (1913), 16, 17.

30. Ibid. (1914), 59, 61.

226

OHIO HISTORY

institutions. The rural leaders found

that in practice, centralization entailed the

transference of real power to the

salaried bureaucrats, the men charged with the

daily execution of agricultural policy.31

Rural sentiment concerning the

commission, however, was not unanimous. The

editor of one local farm journal

strongly opposed elimination of the Agricultural

Commission, maintaining that the new

bureau had increased efficiency and that

those who attacked it were really

jealous of the popularity president Sandles en-

joyed among many farmers.32 This

was almost certainly a minority view, and the

Grange, as the principal farm

organization in the state, probably reflected more

accurately the opinion of the majority

of farmers who cared about the issue one

way or the other.33

The Republican nominee for governor in

1914, Frank Willis, capitalized on this

rural opposition in his attack on Cox's record.

The general theme of the Repub-

lican's campaign was a repudiation of

the centralization and bureaucratization of

government that had characterized his

opponent's administration. "The fight is on

in Ohio," he declared,

"between the machine and the people, between appointive

government and elective government,

between centralization of power in the execu-

tive and retention of power by the

people. . . ."34 "One of the

methods whereby

much power has been placed in the hands

of the executive in recent years has been

through the gradual increase in the

number of Commissions appointed by the Gov-

ernor." Willis was plainly

disturbed by the proliferation of state bureaus and by

the extension of government intervention

into many areas of the economy and so-

ciety. This concern is reflected in his

belief that it was "costing too much to run the

government of the state. . . ."35

He did not believe that the solution to the prob-

lems of his day lay in an expansion of

the government's role or in centralization

of power in the state house. Even though

he won a narrow victory in the election,

Willis felt that a majority of Ohio

voters shared his concern over the growth of

government, and this attitude almost

certainly foretold the abolishment of the Agri-

cultural Commission.36

In his first message to the General

Assembly, the new governor recommended

that the commission be replaced by a

bi-partisan state board of agriculture, whose

members would serve without

compensation. He said, in making appointments to

the board, "the principle should be

constantly borne in mind that actual practical

farmers should be appointed to all

positions having to deal especially with the

agricultural interests of the

state." Willis also suggested an administrative decen-

tralization of the state agricultural

institutions. In short, the governor was proposing

the abandonment of his predecessor's

plan of consolidation and bureaucratization

of these institutions.37

Prominent rural groups, as has already

been shown, were quite favorable toward

31. The Grangers also undoubtedly hoped

decentralization would reduce the operating costs of the

Department of Agriculture. See the

speech of the Grange Master in Journal, Ohio State Grange (1914),

16; he, least, felt the present

operating costs were too high.

32. Tri-County Farmer, February

1, 1915. For a similar opinion, see Holmes County Farmer, Febru-

ary 11, 1915. The editor of the latter

paper supported the Democrats.

33. Grange opposition to the commission

was determined by vote of the entire organization; it was

not a decision merely of the executive

council. Journal, Ohio State Grange (1914), 59, 61.

34. Ohio State Journal, July 19,

1914.

35. Mercer, Ohio Legislative History,

1913-1917, p. 115, 107.

36. Gerald Ridinger, "The Political

Career of Frank B. Willis" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, The

Ohio State University, 1957), 75.

37. Mercer, Ohio Legislative History,

1913-1917, p. 116.

Agricultural Commission 227

Willis' proposals. The same cannot be

said of two other groups affected. The vet-

erinarians had originally opposed the

subordination of their examining board to

the commission because they feared that

they would lose control over their pro-

fession and that, as a consequence,

unqualified men would be permitted to enter

it. They may have changed their attitude

by 1915 because they discovered that

the dreaded decline in standards had not

in fact occurred. The state association's

legislative committee did not, in any

case, criticize the commission in its annual

report for 1915, although the committee

still did want the profession to control

appointments to the examining board.

"If these appointments could be made for

a number selected by this body to pick

from, it might remove it further from poli-

tics." The committee warned against

abolishing the commission itself, however.

"We wish to refer this Association

to the danger of changing from the Agricultural

Commission, possibly back to Board Rule,

as there was danger when changing

from Board to Commission. . . . We are

sorry that the Veterinary profession is

subject to the whims of political

disturbance."38 Thus, the uncertainty attending the

changes in the bureaus that controlled

the examining board apparently disturbed

the committee more than the mere

existence of such control. It is not clear whether

the rest of the state association shared

the views of the legislative committee, but

the veterinarians did not repudiate

their colleagues' report, and the association did

not take an official stand in favor of

abolishment of the Agricultural Commission.

The attitude of the pharmacists is

somewhat easier to determine. The Ohio State

Pharmaceutical Association had never

been enthusiastic over the provision of the

1913 act that deprived the Board of

Pharmacy of authority to enforce the laws

against sale of drugs by unqualified

persons. The legislative committee of that

body, however, did not enter the

campaign for repeal of the 1913 law until it learned

that such repeal formed a part of

Governor Willis' program. State agricultural

leaders agreed with the legislative

committee that the Board of Pharmacy should

enforce the pharmacy laws, and the

committee drew up a bill restoring these en-

forcement powers to the Pharmacy Board.

The committee also supported the effort

to repeal the Agricultural Commission

act and apparently contributed to the suc-

cess of that endeavor. The General

Assembly passed the committee's own act soon

after the agricultural bill became law,

but Governor Willis vetoed the former meas-

ure for reasons unrelated to the subject

of this essay. The enforcement of the

pharmacy laws, consequently, remained

the responsibility of the new Board of

Agriculture, and the pharmacists'

spokesman, the Midland Druggist, advised mem-

bers of the profession to employ their

influence to secure appointment of at least

one pharmacist to the agricultural

board.39 Frustrated in the attempt to regain

direct control over the enforcement of

the laws that protected the profession from

unscrupulous competitors, pharmacists

sought to obtain representation on the board

that did enjoy such control.40

The bill abolishing the Agricultural

Commission passed the General Assembly

38. The committee's report is in Proceedings

of the Ohio State Veterinary Medical Association (1915),

70, 71.

39. Midland Druggist and

Pharmaceutical Review, XLIX (August 1915), 255; XLIX (June 1915), 231,

255, 266; XLIX (June 1915), 266-267.

40. This paragraph is based partially on

the assumption that the actions of the Ohio State Pharma-

ceutical Association accurately

reflected the views of Ohio pharmacists, but such was not necessarily

the case. The president of the

association, himself, admitted that no more than one-third of the state's

druggists were members of the

organization. Since it was the only organization in Ohio representing

pharmacists at that time, it is the best

bellwether of opinion available for that profession.

228 OHIO

HISTORY

in April 1915 by an overwhelming

majority in the house, and by a vote of twenty

to twelve in the senate. In the house,

twenty-four of the twenty-eight farmer mem-

bers voting, including six Democrats,

favored the measure, and all four of those

opposed were Democrats; Republicans,

regardless of occupation, voted solidly for

the bill. Voting in the senate was

strictly along party lines.41

The new law re-creating the Board of

Agriculture provided that the ten mem-

bers of the board would serve without

compensation and stipulated that at least

six members of this bi-partisan board be

actual farmers.42 The law made no pro-

vision for coordination of the

activities of the board, the Experiment Station, and

the College of Agriculture, each of

which was to have a separate managerial heir-

archy. The board did, however, retain

the power to appoint the Board of Veterinary

Examiners, which provision did not

provoke any opposition from the Ohio State

Veterinary Medical Association.43

The repeal of the Agricultural

Commission act did not terminate efforts to re-

organize the Department of Agriculture.

In 1917 James Cox regained the gover-

norship, and a law was then passed

creating an agricultural advisory board com-

posed of the Secretary of the Board of

Agriculture, the Dean of the College of

Agriculture, and the Director of the

Agricultural Experiment Station; the law em-

powered the board to coordinate the

activities of the institutions its members

headed.44 The law, however,

also reduced the Board of Agriculture's control over

its secretary by requiring that the

board's nominee, from outside its membership,

receive the governor's approval. This

was a significant erosion of the farmers' direct

control over the activities of the

Department of Agriculture because the law also

authorized the secretary to act as the

board's agent in performing most of the

functions earlier laws assigned to that

body as a whole. Both the Grange and the

editors of the Ohio Farmer, nevertheless,

approved the law; they supported its

method of achieving coordination of

state agricultural activities, and they recognized

that the Board of Agriculture still had

the power to veto the secretary's acts and

to remove him from office.45

In 1921, however, farmers lost direct

control over the Department of Agriculture.

The General Assembly adopted a new

administrative code for the state which re-

duced the Board of Agriculture to a

purely advisory role and placed administrative

power in the hands of a Director of

Agriculture who owed his appointment to the

governor and not the board, but at the

same time the code provided that the direc-

tor should be a man actively identified

with agriculture. This stipulation furnishes

the clue why rural spokesmen did not

oppose too strenuously the new reorganiza-

tion plan.46 The editors of

the Ohio Farmer had never strongly opposed bureau-

cratic centralization in principle, but

they had always demanded that true repre-

sentatives of the farmer control

agricultural agencies. The new code seemed to

ensure that this requirement would be

met, but the editors nevertheless warned

newly-elected Governor Davis that the

farmers' attitude toward the reorganized

department would depend largely on whom

he appointed to the position of direc-

41. House Journal, 1915, p. 651; Senate

Journal, 1915, p. 416.

42. Laws of Ohio, CV, 143-177.

43. The annual report of that

organization's legislative committee contains no criticism of this pro-

vision of the law. Proceedings of the Ohio State

Veterinary Medical Association (1915), 70-73.

44. Laws of Ohio, CVII, 460-495.

45. Journal, Ohio State Grange (1917),

15-16; Ohio Farmer, February 3, 1917, p. 140; March 17,

1917, p. 396.

46. The new code was simply ratifying a

change that had actually occurred in 1917.

Agricultural Commission

229

tor. This was essentially the same

message that John F. Cunningham had delivered

to James Cox in 1913, but the governor

had failed to select the man whom the

principal rural leaders considered to be

the most qualified. Davis, however, shrewdly

eliminated potential opposition by

selecting L. J. Taber, Master of the Ohio State

Grange, as director.47 This

was the man who, in his capacity as leader of the Grange,

had in 1920 strongly opposed any

reorganization of the Department of Agriculture.48

The Grange did not, like the editors of

the Ohio Farmer, officially approve the

reorganization code, but its silence on

the question was eloquent--the organization

could hardly criticize the creation of a

position to whom its own leader had been

appointed. Harry L. Davis thus achieved

his predecessor's goal of bureaucratic cen-

tralization by ensuring the farmers that

they would continue to enjoy some control

over what they considered to be their

institutions.

A final word is due here on post-1915

organizational changes that affected vet-

erinarians and pharmacists. Subsequent

legislation did finally return to the Phar-

macy Board responsibility for

enforcement of the pharmacy laws, and appointment

of members of the Board of Veterinary

Examiners became the responsibility of the

governor.49

In conclusion, it can be stated that

efforts to reorganize the Department of Agri-

culture involved two different

conceptions of the proper relationship between gov-

ernment and private interest groups.

Governor Cox subscribed to the Progressive

ideal of government-controlled bureaus

staffed largely by public-spirited experts,

men whose specialized training and lack

of identification with any interest group

would permit them to handle expanding

responsibilities of government in such a

way as to promote the general welfare.

To achieve this goal, Cox centralized func-

tions in a number of appointive

commissions and supported the passage of a civil

service law.50

Some farmers, veterinarians, and

pharmacists, however, did not share the gov-

ernor's vision of a thoroughly

bureaucratized government. Their skepticism was due

to the fact that the United States was

just emerging from a period when political

corruption, in both national and state

governments, had reached unprecedented

levels, and many Americans traditionally

tended to believe that men who made a

career of government service were

naturally corrupt or at least self-seeking. Conse-

quently, these groups felt certain that

only their own members could manage com-

petently those state institutions that

affected their interests.

The clash between these two viewpoints

resulted in a compromise between Cox

and the most powerful of the interest

groups concerned, the farmers. The governor

was able to centralize control of

agricultural institutions in the Agricultural Com-

mission, but the farmers succeeded in

securing the appointment of rural representa-

tives to the positions on the

commission. This compromise eventually proved

unsatisfactory, however, partially

because farm leaders concluded that several of

the commissioners, despite their close

connections with agriculture, were more inter-

ested in advancing their own political

fortunes than in serving farmers. Cox's suc-

cessor, Davis, was more successful in

his reoganization efforts because he selected

the man to be director of agriculture

whom prominent rural spokesmen regarded

47. Ohio Farmer, May 7, 1921, p.

620; July 9, 1921, p. 28.

48. Journal, Ohio State Grange (1920),

33.

49. Service Edition of Page's Ohio

Revised Code (Cincinnati, 1953), III, 48, 76.

50. For a more general discussion of the

Progressive concept of government, see Robert Wiebe,

The Search for Order, 1877-1920 (New York, 1967), 159-163.

230 OHIO

HISTORY

as nonpolitical and as the best

representative of their interests.

This concession to rural demands,

however, should not obscure the fact that by

1921 farmers had accepted a modified

version of Governor Cox's concept of govern-

ment. In 1913 the Department of

Agriculture was under the control of a part-time,

unsalaried Board of Agriculture composed

wholly of actual farmers. After 1921 that

board played a purely advisory role

while effective power lay in the hands of a

Director of Agriculture, appointed by

the governor, and his subordinates. Even

though the director might be a

representative of the farmers, his limited term (two

years) meant that he would have to rely

heavily on the officials who were permanent

employees. Farmers could still exert

substantial influence over the officials who

formulated and executed state

agricultural policies, but they had yielded direct

control of their state institutions to

the career bureaucrats.