Ohio History Journal

DONALD A. HUTSLAR

The Ohio Farmstead: Farm Buildings

as Cultural Artifacts

Ohio's rural landscape, though

dwindling, constitutes a signifi-

cant area of the state, some 17 million

acres, largely in the central

and western counties.1 However, Ohio's

agrarian past is still evident

in the urban centers where an occasional

farm building remains

on-site, often adapted to some

commercial use such as a dairy store

or carry-out-an ignominious end at best.

The barn, in particular, has become a

romantic symbol, another in

a long tradition of such symbols which

have become fashionable in

the United States. The cult of the barn

has become so strong that

several firms in the New England area

offer original barn frames for

conversion to dwellings; in fact, one

firm advertised newly manufac-

tured barn frames suitable for houses,

an anomaly perhaps better

interpreted by a psychiatrist than a

historian.2 Romance (defined

here as the imaginative or emotional

appeal of the heroic, adventur-

ous, remote, or idealized) has drawn

other architectural forms such

as water-powered gristmills and covered

bridges, and more recently

opera houses and log buildings, into its

camp. American printmak-

ers, such as the Currier and Ives

company, profited from a current of

romance, nostalgia, and sentiment from

the 1840s into the twen-

tieth century. Their lithographs

reflected a yearning for the "old

homestead," the rural countryside,

from which so many members of

the newly urbanized, industrialized

society had recently departed.3

Donald A. Hutslar is Curator of History,

the Ohio Historical Society.

1. Ohio Crop Reporting Service, United

States Department of Agriculture, Ohio

Agricultural Statistics, 1977 (Columbus, June, 1978), 6.

2. For professional literature on the

subject, see Mildred F. Schmertz, "Upgrading

Barns to be Inhabited by People," Architectural

Record, 115 (June, 1974), 117-22.

3. The allure of cultural artifacts

often becomes difficult to explain even in terms

of romance or nostalgia. For example,

can the present interest in Ohio canals be

classified as "roomantic hydraulic

engineering"? What are the artifacts? Canal beds,

aquaducts, and bridges have been

proposed for the National Register of Historic

Places, but the most important relics,

the original canal boats, no longer exist. A

222 OHIO HISTORY

A desire to return to the supposedly

simpler life-style of the past

demands its symbolism, whether today or

in the nineteenth century.

In Ohio and the Northwest Territory, the

round-log cabin became a

symbol of the settlement period to

persons old enough to remember

the "good old days." Such a

song as "The Log House,"published in

1826,4 was a precursor of the

log cabin songs of William Henry

Harrison's 1840 presidential campaign.

It is interesting to consider

that in 1840 the log cabin was both

symbolic and functional, depend-

ing upon where one lived. Today, the

barn occupies a similar dichot-

omous position in society; it is still a

necessity on many, though not

all, farms, but is regarded as a quaint

anachronism when found in

urban districts. There is an apparent

ignorance of the actual func-

tions of a barn, other than that it has

a haymow and stalls for

animals; in fact, the functions of the

nineteenth-century barn are

now largely unknown even to the rural

population.

Until the general adoption of harvesting

equipment in Ohio dur-

ing the 1850s, the two basic barn

designs - English and German -

had remained relatively unchanged for at

least 200 years, varying

only in exterior surface treatment or

size, depending upon the ex-

perience of the builder, the laborers

and construction materials

available, and the amount of arable land

and number of animals

maintained by the farmer.5

For all practical purposes, the barn was

an implement just as a

scythe or pitchfork; an implement of

heroic proportions, to be sure,

but as carefully designed to complement

the labor necessary in har-

vesting and storage as any hand-tool.

The interior spatial designs

originated in the British Isles and

Northern Europe, and were

brought to the middle American colonies

by the Germans and

Scotch-Irish, the pioneers on the

frontier. No unusual structural

alterations were required during the

settlement of Ohio, because

crop varieties were essentially the same

in the states immediately

east and south. However, New England

immigrants carried their

own barn design to northeastern Ohio, a

structure modified to dairy

similar situation involves the iron

furnaces of southeastern Ohio, of which only a few

derelict stone furnace stacks remain.

Admitting the point is obvious, the foregoing

examples do indicate that there are cultural artifacts

of broad romantic appeal, such

as the barn or mill, as well as

artifacts appealing to specific interest groups or

individuals.

4. "The Log House, A Song,

presented to the Western Minstrel, by John Mills

Brown. No. 19, Of the Sylviad, A.P.

Heinrich, To His Log House," Boston, March

14th, 1826. (Sheet music.)

5. These structures are well-defined in

Eric Arthur and Dudley Witney, The Barn

(Boston, 1972).

The Ohio Farmstead 223

rather than general farming. There is

still a distinct difference be-

tween the rural architecture of the

Connecticut Western Reserve

and the Mennonite/Amish settlements

south of the boundary along

Wayne and Stark counties, though the

dairy industry has since

shifted to the latter district.

The barns and outbuildings of late

eighteenth and early

nineteenth-century Ohio farmsteads were

a natural outgrowth of

three factors: (1) the specific

topography and geology of the indi-

vidual farms, which could dictate

structural configuration; (2) the

ethnic or environmental background of

the farmers (as reflected

through the barn-builders); and, (3)

the type of farming practiced,

whether general farms of mixed crops

and livestock or specialty

farms of a single crop or animal,

definitely determined the interior

spatial configuration of the barns and

the number of supportive

outbuildings.6

The majority of initial settlement

farms, which could date from

1788 to the mid-1850s, depending on the

area of the state, had small

field sizes because of the difficulties

of clearing, tilling, and harvest-

ing with a limited labor force and few

implements. On the other

hand, Ohio farmers never seriously

suffered from a lack of markets

or transportation for their surplus: the military

campaigns of the

Indian Wars of the 1790s; the War of

1812 and the following rush of

settlement; the availability of river and

lake transport; the quick

development of urban and industrial

centers; and the development

of canals and railroads in the second

quarter of the nineteeth cen-

tury gave most farmers adequate

markets. Pork production in

southwestern Ohio, with Cincinnati or

"Porkapolis" as its center,

and the dairy industry in northeastern

Ohio, with Cleveland as its

terminus, are examples of agricultural

specialization made possible

by the transportation facilities

developed between the War of 1812

and the Mexican War.7

The geography of the Ohio Country was

known prior to the settle-

ment of the area. By the mid-eighteenth

century, with the opening

of the fur trade to the English, the

region was being explored for its

agricultural and industrial potential

by the Ohio Land Company.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, the

Moravians, as well as indi-

6. Henry Glassie, "The Barns of

Appalachia," Mountain Life and Work, XL (1965),

21-30. Also see Glassie's, Pattern in

the Material Folk Culture of the Eastern United

States (Philadelphia, 1968).

7. The development of intrastate

transportation, particularly the canals, and its

impact on Ohio's economy during the

period 1820-61 is the subject of Harry N.

Scheiber, Ohio Canal Era (Athens,

Ohio, 1969).

|

224 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

vidual missionaries, were active among the Indians in the eastern half of the state. During the war, meat hunters, squatters, fugitives, soldiers, and militiamen made incursions throughout the future state. Following the war, the quick settlement of the Great Miami River Valley was due to the return of a large number of Kentucky militiamen who had served in campaigns to the Indian villages in the region which later included Greene, Clark, Logan, and Miami counties.8 A similar process of settlement occurred in eastern Ohio in the area of Columbiana, Jefferson, and Belmont counties, Belmont being the home of William Hogland who was elected governor "West of the Ohio" by 1787 by the squatters living illegally in the territory.9 Regardless of motive, this rapid immigration to the Ohio Country indicates that the settlers knew the territory was geog- raphically suited to the same farming operations which they were accustomed to in the eastern states, and, as a corollary, the same

8. Most of the information was probably word-of-mouth, although many indi- viduals did publish their journals. A typical example is David Jones, A Journal of Two Visits Made to Some Nations of Indians on the West Side of the River Ohio, in the Years 1772 and 1773 (Burlington, N.J., 1774). John Heckewelder, Narrative of the Mission of the United Brethren Among the Delaware and Mohegan Indians (Phil- adelphia, 1820) gives the flavor of the missionaries' work on the Ohio frontier. A good military narrative is "Bowman's Expedition Against Chillicothe, May-June, 1779," Ohio Archaelogical and Historical Quarterly, XIX (1910), 446-59. 9. Randolph C. Downes, "Ohio's Squatter Governor: William Hogland of Hoglands- town," Ohio Archaelogical and Historical Quarterly, XLIII (1934), 273-82. |

The Ohio Farmstead 225

type of farm buildings. Specific crop

varieties were soon sought to

meet local climate and soil conditions;

just as today, wheat and corn

were the mainstays.

Ohio displays some interesting

topographic settlement patterns

due to the different methods of survey

and sale of the land over an

extended period of time.10 At

one extreme is the Virginia Military

District with its indiscriminate metes

and bounds surveys. This

area, located between the Scioto and

Little Miami rivers northward

to the Greenville Treaty Line, was

reserved for Virginia veterans of

the Revolutionary War and the French and

Indian War. Acreage

granted, varying from 100 to 15,000

acres, was determined by mili-

tary rank and length of service. The

shapes of the tracts were unre-

stricted, thus creating many irregularly

shaped farms whose con-

figurations were often determined by

topographic features such as

hill, stream, and swamp margins. As

might be expected, farm build-

ings were usually sited with regard to

the peculiarities of the land-

scape, taking advantage of streams,

springs, and hillsides for water

supply, drainage, and protection from

winter winds.

The relaxed, meandering nature of the

landscape created by the

Virginians, however legally confusing,

can be contrasted with the

formal landscape of the Connecticut

Western Reserve. Though there

were inaccurate boundary and interior

surveys, the New England

proprietors laid out the five-mile

square townships and roads as

geometrically correct as possible. The

Greek Revival architecture of

the Western Reserve was as formal and

inflexible as the "lots"

themselves. Farm buildings seldom

nestled into the countryside;

instead, they bravely faced the

elements.

"The "Congress Lands,"

under the jurisdiction of several federal

land offices, composed the major portion

of the saleable land in Ohio.

The land was surveyed on a grid system

of six-mile square

townships composed of thirty-six

sections (unless reduced by topo-

graphic features). Each one-mile square

section contained 640 acres;

a one-family farm was generally

considered to be a quarter-section,

or 160 acres, which is little different

from today's average farm of

about 155 acres.11

These various methods of land division

were a major factor in

10. Several good books are available on

the survey of Ohio. C.W. Sherman, Origi-

nal Land Subdivisions, Volume III of the Final Report of the Ohio Cooperative

Topo

graphic Survey, 1925, is a standard. A

recent work is William D. Pattison, Begin-

nings of the American Rectangular

Land Survey System, 1784-1800 (Columbus,

Ohio,

1970).

11. Ohio Agricultural Statistics, 6.

|

226 OHIO HISTORY |

|

The Ohio Farmstead 227 |

|

228 OHIO HISTORY |

|

determining both the configuration and size of farms in the nineteenth century and the pattern of today's rural landscapes. The difference between the farms of the Virginia Military District and the Congress Lands is quite apparent in counties divided by the Scioto River, such as Franklin, Pickaway, Ross, Pike, and Scioto, as any outline map will show. If the personal character of the settlers marked the landscapes of the Virginia and New England districts, the same can be said of other areas which were settled by immi- grants from eastern states or foreign countries. |

|

The Ohio Farmstead 229 |

|

|

|

Today, while field patterns are often difficult to detect from public roads, farm buildings are usually visible and can serve to identify the initial residents of the land. The so-called Pennsylvania-Dutch influence, best reflected in large stone-gabled bank barns, is occa- sionally seen in Ohio but not as frequently as suggested in commer- cial advertising. The bank barn was adapted to a hilly or rolling countryside which allowed on-grade access to the first and second floors. The Mennonite/Amish evolved their own style of barn, a large braced-frame structure with an L or T extension at the rear, usually banked, which today is most prevalent in Holmes, Wayne, Stark, and Tuscarawas counties. However, members of the sects in Union and Madison counties do not display the same idiosyncrasies. |

230 OHIO HISTORY

The German Roman Catholics of Shelby,

Darke, Mercer, and Au-

glaize counties, many of whom immigrated

in the 1830s to work on

the Miami Extension Canal, replaced

their own log settlement

barns during the fourth quarter of the

nineteeth century with large

braced-frame barns inspired by the

agricultural literature of the

period. Neighboring the Germans

immediately to the south in

Darke and Miami counties are French

Roman Catholics, whose

ancestors immigrated in the late 1840s

and early '50s. In the pres-

ent age of agribusiness, these families

have retained their relative-

ly small nineteenth-century farms, which

range from 80 to 160

acres, and correspondingly small

three-and four-bay braced-frame

barns.

Southeastern Ohio was never suited for

large-scale crop farming

because of the hilly terrain, though

several river valleys have excel-

lent land, but small general farms were

common. Many of the resi-

dents worked at subsistence farming and

at one of the iron furnaces

or coal mines; industrial wages were

seldom sufficient to support

families. One-room log and braced-frame

barns are still in use, as

well as some well constructed double-pen

and braced-frame bank

barns in the prosperous valleys. In

addition, there are many tall

tobacco houses, both log and frame, once

used for heat-curing tobac-

co, a method no longer practiced in

Ohio. Northwestern Ohio was

opened to farming by extensive ditch and

tile drainage and the

Miami-Erie Canal during the second and

third quarters of the

nineteenth century. Farms were (and are)

devoted to wheat and

soybeans and market vegetables. The

barns are large multi-bay

braced-frame structures, and reflect the

eclecticism in design

brought about by the national

agricultural press during the second

half of the century.12

Southwestern Ohio, comprising most of

the Virginia Military Dis-

trict, "Symmes' Purchase"

between the Miami rivers, and some Con-

gress Lands, has the greatest variety of

barn designs and construc-

tion techniques due to the broad ethnic

background of those who

settled in the region, and a sound

economy throughout the

nineteenth century which allowed farmers

to improve old or con-

struct new buildings as needed. There

are many barns dating from

12. The agricultural press was a

significant force in amalgamating the diverse

sectionalism and foreign elements in

American agriculture. The first important

periodical in Ohio was the Ohio Cultivator,

published in Columbus beginning in

1845. An important compilation such as Barn

Plans and Outbuildings (New York,

1881) was the outgrowth of the national

periodical, the American Agriculturist, pub-

lished by Orange Judd.

The Ohio Farmstead 231

the first quarter of the century. Among

the various designs that can

be found in the region are double-pen

log barns and three-bay

braced-frame bank barns, stone gabled

Pennsylvania-style bank

barns, four-and five-bay braced-frame

barns, a few octagon barns,

and, for the twentieth century,

balloon-framed, brick, and tile barns

which often look more like industrial

buildings than farm struc-

tures.

An asymetrical entrance, four-bay barn

is most typical of this

section of the state. This design,

simply an enlargement of the En-

glish-style three-bay barn, allocates an

extra bay beside the en-

trance for an integrated two-bay dairy

or stanchion and box-stall

area. (Once common in the Western

Reserve, these barns, featuring

the square silos peculiar to this area

and dating from the last decade

or so of the nineteeth century, are

still in existence.)

The ancient Saxon combined barn and house,13

with the family

and livestock housed on the same level,

and the Swiss or Southern

German form (the so-called

"Sweitzer" barn14), with living quarters

above the livestock, must be considered

so rare in Ohio-as pur-

posefully chosen designs-to be nothing

but anachronisms. No

doubt many settlers shared temporary

quarters with their livestock

when first moving to the frontier, for

such arrangements are occa-

sionally mentioned in Ohio county

histories; but from an

architectural viewpoint, such folklore

is suspect. Historian Henry

Howe pictures a Swiss house in

Columbiana County simply because

such architecture was unusual in Ohio.15

Since a few Swiss-style

houses were constructed, it is entirely

possible the house-barn de-

sign was also utilized. No examples,

however, are known.

Historically, the three-bay barn is the

most interesting configura-

tion found in Ohio. This design dates

at least to the seventeenth

century and owes its popularity as much

to the requirements of the

single-family frontier farmstead of

North America as to English or

North European farming practices. By the

late eighteenth century

13. In Arthur and Witney, The Barn, the

authors discuss the Saxon barn, with its

church-nave interior and family living quarters, and

its alteration to a purely farm

structure in North America. George E.

Burcaw, The Saxon House (Moscow, Idaho,

1973), is a look at the living quarters

as they separated from the barn cum house.

Peter Kalm, a Swedish naturalist

traveling in the American colonies in 1748-51,

described the Dutch barn as the dominant

style between Trenton and New York City,

the "Dutch barn" being a

direct descendant of the Saxon barn: Travels in North

America, 2

vols. (New York, 1966, reprint of 1770 English version), vol. 1, 118-19.

14. Type F or G, according to Charles H.

Dornbusch's summary of styles in Penn-

sylvania German Barns (Allentown, Pennsylvania, 1958).

15. Henry Howe, Historical

Collections of Ohio (Cincinnati, 1848), 108. This writer

has seen photographs of a similar house

in Switzerland Township, Monroe County.

232 OHIO HISTORY

the three-bay barn had received an

official recommendation from

the British government and had been

described in builders' books

such as The Carpenter's Pocket

Directory by William Pain and, early

in the nineteenth century, Abraham Rees'

Cyclopaedia.16 Known

today as the "English" barn,

the design became as standard to the

ever-advancing frontier as the log cabin

and was as conveniently

constructed of logs as it was of mortised

posts and beams-the

"braced-frame" technique.

William C. Howells, a prominent Ohio

newspaper editor and

father of William Dean Howells,

described a three-bay, double-pen

barn built by his family in Jefferson

County shortly after the War of

1812:

This summer we also built a barn of logs

.... There were two pens put up

twenty-four feet apart, and raised on

one foundation .... They were in this

way carried up to a proper height, when

they were connected by logs and a

common roof. This made a double barn,

with stabling and more room at

each end, and a barn floor and

wagon-shed in the middle. Such was the

universal style of barns in that country

....

The settlers were mainly from western

Pennsylvania, though many had

come in from the western part of Maryland

and Virginia, and the prevailing

nationality was the Scotch-Irish of the

second generation ... .17

An interesting cultural interchange

occurred during the expan-

sion of the western frontier in the

eighteenth century. The Scotch-

Irish, who had no tradition of log

construction, learned the tech-

nique from colonists of Central European

background; the interior

arrangement of their houses and the

adherence to open fireplaces,

however, remained traditional to the

British Isles. The northern

Germans, on the other hand, rather than

adopting the Saxon barn

as it evolved in the Netherlands and

the Hudson Valley, with its

naves and gable entrance, constructed a

log version of the English

three-bay barn. In practical terms, log

construction was the quickest

16. William Pain, The Carpenter's

Pocket Directory (Philadelphia, 1797) was a

very influential builder's book. Abraham

Rees, The Cyclopaedia: or, Universal Dic-

tionary of Arts, Sciences, and

Literature, was noted by the

Englishman Henry Brad-

shaw Fearon when in Boston during his

American tour in 1817; Fearon said it was an

American edition. See Fearon, Sketches

of America (London, 1818), 105. Rees' Cyclo-

paedia, first published in England, was an important source of

technological informa-

tion on both sides of the Atlantic, and

contained forty plates of illustrations as well as

a lengthy text on barns and various

agricultural matters.

17. William Cooper Howells, Recollections

of Life In Ohio, from 1813 to 1840 (Cin-

cinnati, 1895), 118-19. An identical

barn was described in Highland County before

the War of 1812. See Daniel Scott, A

History of the Early Settlement of Highland

County, Ohio (Hillsborough, Ohio, 1890), 148-49.

The Ohio Farmstead 233

and easiest frontier building technique,

and the English-style barn

was best suited to the construction

methods available as well as the

exegencies of frontier farming.18

In constructing the three-bay log barn,

two log pens were raised,

separated by a space equal to the width

of one wall; a single roof

spanned the entire length of the two

pens, creating three distinct

work and storage areas. The structure

was spatially suited to the

manual labor of frontier farming or to

the small, non-mechanized

farm, regardless of period. One pen was

usually divided into stalls

for oxen or work horses; normally, a

haymow occupied the space

above the stalls. In Ohio, the entire

opposite pen almost always

served as a haymow; in a few exceptions,

dairy stanchions appear.19

Such was the case even in New England

three-bay, braced-frame

barns, according to a Massachusetts

historian:

On one side of the threshing floor of

the barn were the stables for the horses

and cattle and upon the other the great

haymow. On the scaffold over the

stables [haymow] the "horse

hay" was garnered, and upon the "little scaf-

fold" over the far end of the barn

floor [overbay] were nicely piled the bound

sheaves of wheat, rye or barley ... 20

The open, central space between the

pens, besides providing access

to the haymows, was used for threshing

and winnowing grain and

general chores. Until the mid-nineteenth

century, practically all

Ohio barns were aligned with their main

doors on an east-west axis

to allow the prevailing westerly winds

to blow through the "breeze-

way" and hopefully carry away the

dust and chaff of the winnowing.

Logs placed between the pens above the

breezeway formed an "over-

bay," where unthreshed sheaves of

cereal grains (usually wheat)

could be stored.

Threshing with a flail was slow work. In

a full working day of

twelve hours, the average farmer could

thresh about five bushels of

wheat; winnowing then occupied about

half the following day.21

Since the unthreshed grain could not be

left in the fields because it

would rot or sprout, storage was

provided in the barn. The grain

18. Clinton A. Weslager, The Log Cabin

in America (New Brunswick, New Jersey,

1969), is the best general history of

log construction in the United States.

19. For log construction in Ohio, see Ohio

Log Architecture (Columbus, Ohio, 1971

and 1977) by this writer.

20. Francis M. Thompson, History of

Greenfield, Massachusetts, (Greenfield, 1904),

II, 963, quoted in Percy W. Bidwell and

John I. Falconer, History of Agriculture in the

Northern United States, 1620-1860 (New York, 1941, reprint), 122.

21. Thirteenth Annual Report,

Commissioner of Labor, 1898, Hand and Machine

Labor, (Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 1899),

I, 470-73.

234 OHIO HISTORY

could then be threshed as needed. The

sheaves were pitched from

the overbay to the threshing floor and

arranged in parallel lines or a

circle; then, after flailing (or

treading by oxen), the straw was

pitched into the low mow over the

stalls, and the grain was swept up

for winnowing. Winnowing was a cleaning

technique of sifting for-

eign matter from the grain with a sieve and throwing the

grain into

the air to allow a breeze to blow away

the chaff. It was tedious work

at best. When there was no wind, a

bedsheet attached to poles was

used as a fan. The threshing floor, if

wood instead of tamped earth,

had to be tightly constructed to prevent

the grain from dropping

through. There were usually two layers

of flooring, so all the joints

between floorboards would be covered.

Hollow sections of tree

trunks-most often sycamore charred by

fire on the inside-made

acceptable grain bins.

The middle bay of the three-bay barn

could be considered an effi-

cient threshing machine in which the

farmer served as the prime

mover. During the 1820s and '30s the

farmer's hand-labor was re-

duced as horses and oxen were used to

power many of the simple

grain-processing machines, such as the

"groundhog" drum thresher

and the fanning mill. The

"horse-power," or sweep (capable of 200

revolutions per minute), was often built

as a permanent feature of

the barn, either on the main floor or in

the basement of a bank

barn.22 Other simple

machines, such as the corn sheller, feed grind-

er, and forage chopper, could be run

from the horse-power, thus

anticipating the convenience of the

internal combustion engine

some fifty years later. During the 1830s

and '40s the hay press,

requiring its own source of animal

power, was often constructed as

part of the barn framing. These presses

were popular on farms along

the Ohio River where there was easy

transport to the southern

market for the 300 pound bales. By the

Civil War, a wide variety of

crop-processing equipment had evolved

and the barn was gradually

relieved of its symbiotic partnership

with the farmer.23

Threshed grain and shelled corn were

stored in bins usually

placed in lean-to sheds attached to the

exterior of the barn. These

sheds also housed the few large

implements that every farmer pos-

sessed, such as a plow, harrow, mud sled

or boat, and wagon, as well

as the myriad of hand tools.24 The

breezeway doors could be attached

22. Marvin Smith Company Catalog, Chicago,

ca. 1897, 158-61.

23. There are many books on farm tools

and implements. Original company cata-

logs and broadsides are frequently found

in libraries. Among the best contemporary

sources are the exhibit catalogs from

the various world expositions, beginning in the

mid-19th century.

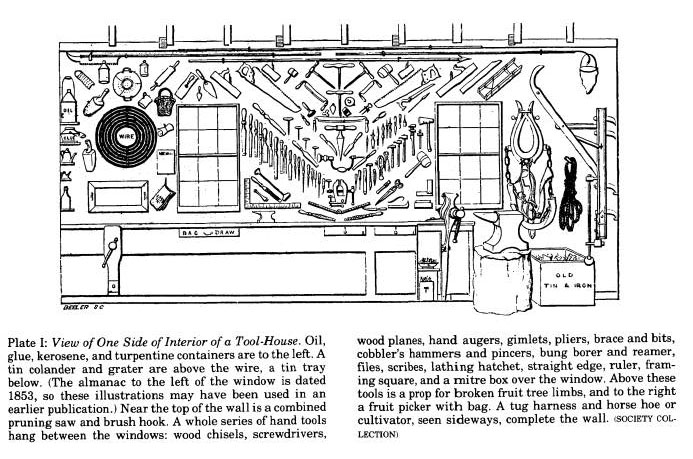

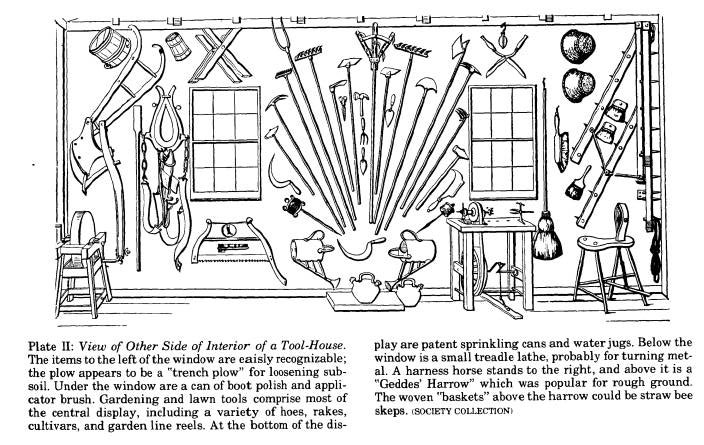

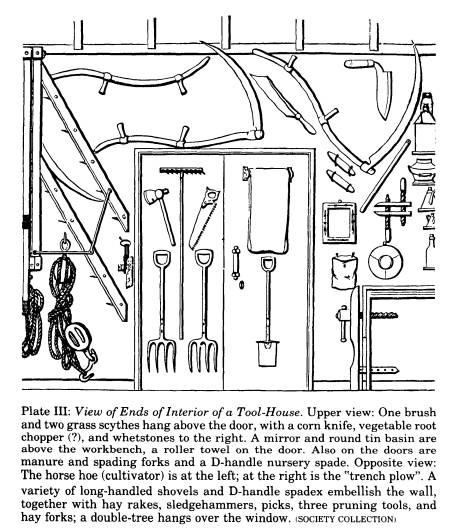

24. Plates 47, 48, and 49 in the Report

of the Commissioner of Patents for the Year

The Ohio Farmstead 235

to the main barn frame or to the shed

framing. Early in the

nineteenth century, there were two

opinions on how to store hay-

whether to leave the mows open or closed

to the weather. Because

"making hay" was a slow

job-cutting, curing, and pitching on

wagons and into mows-and very dependent

upon the weather,

there was a natural inclination for

farmers to put-up slightly green

hay. Ample ventilation reduced the

chances of mold or, even worse,

spontaneous combustion. Proponents of

ventilated haymows had

won their case by mid-century. The

spaces between the logs were

seldom chinked in a log barn, so there

was good air circulation in the

mows with or without attached sheds.

Indian corn was usually not stored in

the barn, for it was easier to

build a free-standing, pole corncrib (in

the same fashion as a log

cabin, but unnotched). Once again, ample

ventilation was necessary

to prevent the husked ears from molding.

Corn was usually cut and

shocked in the field, both to allow the

ears and fodder to dry and to

clear as much land as possible to plant

winter wheat. After the

wheat was planted and the ground frozen,

the corn could be husked

and hauled to the crib without danger to

the new crop. The tedious

job of shelling by hand took place in

the barn during odd intervals in

the daily routine or when needed. Or

course, if the corn was to be fed

to livestock, shelling was not

necessary. The time-honored "husking

bee" was held when the shocks were hauled

to the barn rather than

allowed to stand in the field. The

breezeway then became the scene

of such festive occasions as those

pictured by Currier and Ives.25

From pioneer times until at least the

1840s, it was not customary

to stable any farm animals except the

most valuable, such as the

work horses or oxen, though exceptions

were made in particularly

severe weather. If a farmer could afford

the structure, the bank barn

was an excellent solution for handling

both crops and livestock. By

utilizing a hillside or creating an

earthen ramp, a barn could have

two, occasionally three, distinct work

levels. The lower level was

customarily divided into loose stalls,

box stalls, stanchions, a feed-

ing pen, and often bins for storing

vegetable roots for feeding cattle.

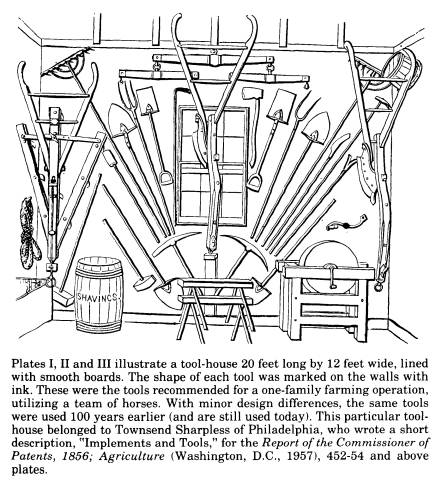

1856, Agriculture (Washington, D.C., 1857) picture the four walls of a

tool house

recommended for small farms. No

horse-drawn harvesting implements are shown.

Except in details of construction, the

same tools could be dated at least 100 years

earlier.

25. A good example is Eastman Johnson's

painting Husking, lithographed in large

folio by Currier and Ives in 1861.

However, in the November 18, 1837, issue of the

(Piqua) Western Courier &

Enquirer in an article entitled "Husking Party," a quilt-

ing frolic, apple-paring, and husking

party are referred to as the "customs and pas-

times of our ancestors."

236 OHIO HISTORY

For added protection and more storage

space, the upper structure

usually extended over the doors leading

into the basement, the ex-

tension being known as the

"forebay." The connected "barn lot" was

also part of the basement complex, where

livestock could be fed and

watered. The main barn floor was reached

from the side opposite the

basement doors, one level higher. This

created a problem in the lack

of a continuous passage for wagons

through the barn. On the other

hand, the storage of feed and hay

immediately above the livestock

and the warm shelter provided by the

basement were advantages. In

fact, the basement was often excessively

warm from the body heat of

the animals, and had to be ventilated

with ductwork reaching to

roof cupolas.

The large bank barn became a mark of

success for Ohio farmers

after mid-nineteenth century, though for

the average farmer the

three- or four-bay English-style barn

remained a viable form of

architecture through the century because

it was easily constructed

or remodeled to accommodate the gradual

mechanization of agricul-

ture. A good example of a double-pen

(three-bay) log barn is located

on the Piqua Historical Area's John

Johnston Farm, a state-owned

property administered by the Ohio

Historical Society.26 This barn,

the oldest documented example of its

type in the state, was con-

structed in 1808; it was enlarged with

framed sheds and had a

wooden threshing floor installed in

1826; in 1852 it was re-roofed for

a hay carrier; about 1930, the barn was

altered for a dairy operation.

Based on literary and on-site research,

the barn has been restored to

its 1826 appearance. The Johnston barn

is also the largest of its type

known in the state. The log pens measure

almost 30 feet square,

making the basic structure 90 by 30

feet; the sheds add an extra 20

feet to the perimeter. The average

double-pen barn was a third

smaller.

With the general availability and

acceptance of horse- and steam-

powered implements, which were not a

major influence on Ohio

agriculture until at least the 1850s,

barns were altered both in

function and physical appearance. The

most obvious alteration was

the heightening of roofs to gain space

for hay carriers (which in turn

increased mow capacities). Before the

Greek Revival period in

architecture, almost all roofs-barns and

houses alike-were con-

structed with about a 36 degree slope

from eave to ridge (9 inch rise

in 12 inch run). The need for increased

storage and mechanical forks

was the direct result of the mowing

machine, in itself an immediate

26. The Johnston barn is pictured in

Hutslar, Ohio Log Architecture, 44.

The Ohio Farmstead 237

by-product of the grain reaper of the

1840s. Although the reaping

machine had been proposed by various

inventors during the first

quarter of the century, it was not until

the 1830s that specific

machines were offered to the public, and

the 1840s before reliable

results could be expected.27 Quicker

harvesting meant more land

could be put in production. The physical

labor and time involved in

scything grain or hay was enormous:

reaping, binding, and shocking

an acre of wheat in 1829-30 took two men

approximately twenty

hours; sixty-five years later the same

amount of wheat could be

reaped, threshed, and sacked in about

eighteen minutes.28 The barn

had lost its function in threshing,

winnowing, and straw storage,

but had found a new role in providing

greater bin capacity for grain

and the attendant milling equipment.

Improved processing machinery, more land

in production, im-

proved livestock, better preserving and

distribution systems-each

contributed to the modification of the

barn as the nineteenth cen-

tury ended. Perhaps the barn was losing

something of its personal-

ity, its compatability with the land and

the farmer, as the machine

intruded. It is interesting to speculate

on the reasons for the decline

of the barn in Ohio. General farms, with

both crops and livestock,

have become scarce; instead, farmers

specialize in just one commod-

ity, each now requiring specific

structures. Aside from the Mennon-

ite or Amish barns, few, if any, barns

of the traditional general-use

design are being constructed. Instead,

the farmer buys prefabricated

structures designed for his needs,

whether cattle, sheep, or hog

sheds, machinery sheds, food processing

and storage buildings, or

cribs, bins, and silos. Of the wide

variety of farm buildings extant,

the barns built during the

pre-mechanization decades are the most

interesting, for, in order to survive,

they have been altered by gen-

erations of owners. Ohio barns are

indeed cultural artifacts, for in

their design, construction, and

alterations the history of agriculture

throughout the state can be read.

27. The catalog, Official

Retrospective Exhibition of the Development of Harvesting

Machinery for the Paris Exposition of

1900, by the Deering Harvester

Company,

Chicago (Paris, 1900), pictures all the

models made for the exhibit of historic reaping

and mowing machines, and is an excellent

quick reference.

28. Hand and Machine Labor, I, 470-73.