Ohio History Journal

GEORGE E. STEVENS

THE CINCINNA TI

POST AND

MUNICIPAL REFORM,

1914-1941

City government in Cincinnati underwent

a drastic overhaul in the 1920's. Once

called the worst governed city in the

United States by Lincoln Steffens,1 Cincinnati

became a model of good government so

quickly that the transformation amazed

even the most idealistic reformers.

"The new regime showed so complete a reversal

of form from the old that it left

observers dazed," wrote Alvin F. Harlow.2

This reversal of form was made possible

in 1924 when voters ended bossism by

amending the city charter to provide for

two basic changes in municipal government:

the election of a nonpartisan city

council by the Hare system of proportional repre-

sentation and the hiring of a city

manager. During a period when many Ohio cities

were cleaning house, Cincinnati became

the third large city in the state to adopt

a city manager form of government,

following Dayton and Cleveland, and one of

the first large cities in the United

States to make proportional representation work.

The changes were so successful that

Cincinnati soon enjoyed what many regarded

as "the best government in any of

the larger cities of the country."3

Reformers credited the Cincinnati Post

(now the Post and Times-Star) with the

successful advocacy of good city

government. In 1924 the Post stood alone among

the city's dailies to support extensive

revision of the city charter. In the years that

followed, it remained a steadfast

advocate of the reform-minded Charter party and

of proportional representation. Murray

Seasongood, a leader of the reform move-

ment and Cincinnati's first mayor under

the revised charter, called the Post the one

unfailing newspaper champion of good

government in Cincinnati, "like the shadow

of a great rock in a weary land."4

Russell Wilson, who followed Seasongood as

mayor, said the Post was

"one of the most important factors in the rehabilitation

of our beloved city."5

One of Ohio's largest newspapers, the Post

had a reputation as a reforming,

crusading newspaper which dated back to

1883, two and one-half years after its

1. Lincoln Steffens, "Ohio: A Tale

of Two Cities," McClure's, XXV (July 1905), 293.

2. Alvin F. Harlow, The Serene

Cincinnatians (New York, 1950), 415.

3. George H. Hallett, Jr., Proportional

Representation--The Key to Democracy (New York, 1950), 2.

4. "Civic Achievements of

Cincinnati Post Praised at Jubilee Dinner," Editor and Publisher, Jan-

uary 17, 1931, p. 12.

5. Ibid.

Mr. Stevens is assistant professor of

communication at Purdue University.

232 OHIO

HISTORY

founding, when Edward Wyllis Scripps

became its owner. Scripps set the Post on

a course of public service to improve

the lot of the common people and at the same

time build circulation. A combination of

local crusades, short and easy-to-read local

news stories, and a low price gave the Post

by 1886 the largest newspaper circula-

tion in Cincinnati. For most of the next

fifty-five years it kept this lead.

In politics the Post was

independent and prided itself on being free to advocate

only what it believed to be in the best

interests of the majority of the people;

the Times-Star and the Commercial

Tribune were staunchly Republican; and until

the 1930's the Enquirer was

Democratic, but conservative, and often silent on local

affairs. The city's most liberal daily,

the Post, concentrated on state and local issues,

supporting a variety of fusion tickets

and reformers in both major political parties.

During the early years of the twentieth

century the Post was the only Cincinnati

daily which consistently battled Boss

George B. Cox and vigorously backed state

constitutional reform.6

During the closing days of the Cox era,

political reformers in Cincinnati were in

a hopeful mood. One of the 1912

amendments to the Ohio constitution allowed

cities to adopt their own charters free

from restraint by the state legislature. In

1914, therefore, reformers in Cincinnati

tried to get a charter adopted which included

provisions for a nonpartisan city ballot

and a city council elected at large instead

of by wards. The Post campaigned

for this proposal with enthusiasm. The news-

paper was an old friend of the

nonpartisan city ballot idea, believing that bossism,

which it despised, would be seriously

hurt if party labels were removed from the

ballot. No longer would political

machines be able to round up illiterate voters and

pay them to vote for candidates listed

under party emblems. The Post also believed

that an "at large" system of

balloting was a step in the right direction since the

ward system was important to machine

control of city government. For six weeks

prior to the 1914 vote the Post ran

a series of "charter talks," listed civic leaders

who favored the proposal, and gave the

charter strong editorial support. But the

proposal was defeated. Its foes had

argued successfully that an "at large" council

would take away effective representation

of citizens.

The Post was the only Cincinnati

daily that had supported this proposal and

had been quick to point out why the Commercial

Tribune and the Enquirer were

against the charter and why the Times-Star

was neutral. Under existing law public

advertising had to appear in three city

newspapers, and usually the Post was left

out. According to its figures, from 1908

to the middle of 1914 the other three

large dailies in Cincinnati were paid a

total of $127,499 for public advertising while

the Post had received only

$5,237. The charter proposal had called for publication

of a City Bulletin in which all

official advertising would appear, and the Post sus-

pected that the city's other dailies did

not like the prospect of losing income.7

In 1917 the Post was silent when

another charter proposal, supported by the

Commercial Tribune, the Times-Star and the Republican machine, came

before

Cincinnati voters. The Post's only

effort was an unsuccessful attempt to elect the

paper's stockholder Alfred G. Allen

mayor. On April 11, seven months before the

vote, the newspaper simply presented the

credentials of each of the forty-five can-

6. The Cincinnati Post's crusades

for good local and state government are discussed in Hoyt Landon

Warner, Progressivism in Ohio,

1897-1917 (Columbus, 1964), 150-151, 159, 188, 305. For an account of

the history of the newspaper, see George

E. Stevens, "From Penny Paper to Post and Times-Star: Mr.

Scripp's First Link," Cincinnati

Historical Society, Bulletin, XXVII (1969), 207-222.

7. Post, July 2, 1914.

|

|

|

didates for the charter commission without endorsing the liberal Citizens' Charter Ticket. All fifteen candidates of the conservative Greater Cincinnati Charter Com- mittee were victorious. This committee drew up a charter which voters approved. It called for voting to continue under party emblems, a city council of thirty-two- twenty-six to be elected from wards-and a mayor as the city's chief executive officer. In essence, it continued the existing form of city government. Under this charter the Republican machine, in power almost without interrup- tion since the 1880's, continued to govern even though Boss George B. Cox's suc- cessor, Rudolph K. (Rud) Hynicka, had moved to New York to look after business investments and had to send instructions to city hall by telephone and telegraph. There was much criticism of this absentee control of local politics. Even the strongly Republican Times-Star did not like this arrangement and in 1920 called for Hynicka's ouster, declaring that "Hynicka should get out, or be put out, at the earliest prac- tical moment. His place should be taken by some Republican who lives here, who is in touch with the feelings of our people. .. ."8 Hynicka nevertheless remained as boss of Cincinnati politics, and the city council 8. Cincinnati Times-Star, June 17, 1920. |

234 OHIO

HISTORY

did as he wished, as the Post revealed

the following year. On November 26, 1921,

city council voted against an increase

in the natural gas rate but quickly reversed

the vote after receiving instructions

from Hynicka. The Post got a copy of a tele-

gram he had sent to local Republican

leaders and printed it across seven columns

of the front page on November 28:

Understand Council committee with help

of our friends working out most equitable gas

contract ordinance. Very essential that

Republican councilmen agree and that organization

get behind Council and share

responsibility. I assume measure will represent concessions

and compromises. While we should aim for

best obtainable we must not permit unfriendly

influences stampede. They will pick

anything to pieces. You are authorized to discreetly

make any use of this you see fit.9

Just how the Post was able to get

a copy of the telegram is not clear. Columnist

Alfred Segal wrote that a Western Union

operator, realizing that he was violating

Federal law but feeling that he had a

duty higher than the law, brought the tele-

gram to the Post.10 Reporter

Charles Rentrop believed that a copy of the telegram

may have been secured through the

contacts of Post city editor David S. Austin.11

The paper made the most of this

opportunity, no matter how the telegram was

obtained. On November 29, it asked in a

front page editorial: "Who are 'Our

Friends?' " and pointed out that

Hynicka had no right to dictate what should be

done by city council.12

The council, thirty-one Republicans and

only one Democrat, voted as ordered.

On November 29 it passed the gas

ordinance. The next day the Post commented,

"To the everlasting shame of the

municipal legislative body, the deal was put over

in this steam roller fashion with all

details in keeping with the secrecy and effrontery

that have marked the entire handling of

the gas matter."13

There were several problems confronting

the Cincinnati Republican machine in

the early 1920's in addition to those

revealed by the Post and those criticized by the

Times-Star. The facts show that the city, generally, was in pretty

bad shape. Its

per capita indebtedness was among the

highest in the nation, services were poor,

taxes were high, and crime and vice

flourished. The time was right for another

reform movement, and it was not long in

coming.

On October 10, 1923, Cincinnati

newspapers carried accounts of a speech given

by Murray Seasongood at a meeting of the

Cincinnatus Association the night before.

The association, founded in 1920 to

discuss matters of public concern, heard the

forty-five year old attorney call the

GOP machine "a blot on our city" and ques-

tion whether voters should approve a

three-mill levy the local Republican organiza-

tion had placed on the November ballot

to cover the city's financial deficit. The

time had come, he said, "to cut out

every tax levy, bond issue or anything else

that will give this bunch a chance to

squander money."14 This speech by Season-

good, a respected Republican and a

member in good standing of the Cincinnatus

Association, started a campaign to rid

the city of bossism and change the charac-

ter of Cincinnati city government.

Seasongood found two eager allies on the Post

9. Post, November 28, 29, 1921.

10. Ibid., August 5, 1948.

11. Interview with Charles Rentrop,

March 20, 1968.

12. Post, November 29, 1921.

13. Ibid., November 30, 1921.

14. Agnes Seasongood, Selections from

Speeches (1900-1959) of Murray Seasongood (New York,

1960), 52-54.

Cincinnati Post 235

for his battle against the machine. One

was Elmer P. Fries, editor of the news-

paper and a friend of reform. Fries

joined the Cincinnatus Association and liked

what he found there. The other was the

idealistic Alfred Segal, who had been

using his public service

"Cincinnatus" column on the Post's front page to promote

better government. (Segal was not a

member of the Association. The fact that his

column bore that title appears to have

been a coincidence since Segal referred to

himself as Cincinnatus.)

The day after Seasongood's speech the Post

summarized his remarks without

comment, but on October 11 Segal led off

his column with the following statement:

Cincinnatus is glad to hear other voices

joining his to cry out against the political evils that

afflict the city. He likes especially to

be joined by a good, clear voice like that of Murray

Seasongood, a former member of the

Republican Executive Committee, who has called

public attention to the tax spenders at

the City Hall who now are asking for millions more

to spend.

But merely to cry out is to be as

ineffective as the giant who thought he could crumble

a mountain with the thunder of his echo.

But when all the giants in the land combined,

not their voices, but their mental and

physical forces, they succeeded in moving the mountain.

It seems to Cincinnatus that the time is

at hand for a union of independent men to wreck

the political machine that is the

government of Cincinnati; an organization of Republicans

and Democrats to plan for the municipal

campaign of 1925 and, when the time comes, to

nominate and elect a competent mayor.

Let us make an end to crying out and

commence the doing. Who will lead in the doing?

Strong young men are needed for

leadership, zealous young men who are not afraid.15

For the time being, the

"doing" fell to Seasongood. The machine felt that criti-

cisms from respected Republicans should

be answered, so Vice-Mayor Froome

Morris and Seasongood countered one

another in a series of joint appearances

before civic groups. Seasongood also

made other speeches alone to support his

position. All Cincinnati newspapers gave

the speeches good coverage, especially

when the two men appeared together. In

Seasongood's opinion, city officials would

have been wiser to have ignored his

charges. "Had they done nothing the matter

would doubtless have ended right

there," he later wrote.16 But the attacks and

counterattacks made news and the

controversy was kept before the public.

The Post had little sympathy for

the Republican side. Typical was this report.

after Morris talked to the City Club:

"Froome Morris, vice mayor, spoke before

Seasongood. He painted a picture of

civic poverty and destitution with the city

administration battling desperately with

its army of officeholders to keep the wolf

away from the door at City Hall. . .

." Almost daily, Segal praised Seasongood's

position. On October 20 the columnist

suggested that a citizen's charter committee

be formed to draw up a type of

government under which "the business of the city

may be conducted for the benefit of the

citizens instead of for the benefit of a

political organization."17

The Times-Star, meanwhile, was

taking a dim view of the whole business. "The

time to effect changes in party or

government control is at the primaries or at an

election," the Taft newspaper

argued. "It does not help to strike at the city by refus-

ing to give those, to whom the voters

have entrusted the business of running the

15. Post, October 11, 1923.

16. Murray Seasongood, Local

Government in the United States (Cambridge, Mass., 1933), 23.

17. Post, October 20, 1923.

236 OHIO

HISTORY

municipal government, funds necessary

for carrying out their work."18 The Post

also had some concern about what the

levy's defeat would mean to citizens in

terms of curtailed services. An

alternative was suggested:

Popular resentment indicates a pretty

general feeling that the incompetents at City Hall

should be kicked out. . . . Those who

feel that way about it and still believe that the city

should have the funds it asks, so that

important public services may not be further crippled,

are embarrassed.

To them The Post offers the suggestion

that by voting for the tax measures, and thus

relieving their consciences, they may do

the city a great service if at the same time they

pledge themselves to vote out the ruling

crowd at the first opportunity and declare for a

new deal at City Hall.19

Disregarding the newspapers' appeals,

the voters rejected the three-mill levy by

14,000 votes. The Post immediately

issued a call for a nonpartisan form of govern-

ment to restore public confidence in

city hall. An editorial, probably written by

Segal, was printed in the Post November

7, the day after the levy's defeat. It read,

in part:

The results of Tuesday's vote on the

proposed city tax levy . . . give evidence that the peo-

ple have lost faith in the political

management of the city government. . . .

But merely to cry out on election day is

bootless; to protest one day of the year and to

shut our eyes on the other 364 days to

the political evils that afflict the city is worse than

folly. So on this day after election The

Post repeats its call for courageous citizens to orga-

nize to make an end of the rule of

politics and to put in its place a government without

politics and without

politicians--Democratic or Republican; a government that knows no

party and is conducted for the benefit

of the community and not for a political machine. . . .

What is needed is not a governmental

house-cleaning, but a new house-a new form of

government! A non-partisan form of

government, a new governmental house built on the

model that progressive cities in Ohio

have adopted.20

The Hamilton County Republican executive

and advisory committee, sensing

trouble ahead, soon appointed its own

study group, headed by Lent D. Upson,

director of Detroit's Bureau of

Governmental Research. While Seasongood, the

Cincinnatus Association, and other

reformers continued to point out the need for

better municipal government, the

GOP-sponsored study group went about its work

gathering information on the good and

bad in city politics. The Post kept an inter-

ested eye on the activities. In May

1924, the Post ran a series of civic progress

articles, and in his column Segal

continued to call for the adoption of nonpartisan

city government. Meanwhile, the status

of the incumbent mayor and council was

shrinking fast. Real estate taxes had to

be redistributed to meet city expenses and

services were seriously curtailed. Sewer

construction was virtually stopped, police

were laid off, fire stations were

closed, and street cleaning became less frequent.

The Upson Report, the work of the

special study committee, was released to the

press on July 28, 1924. It contained

several recommendations, including sugges-

tions for a nonpartisan ballot, a

nine-man council elected at large by proportional

representation, and the hiring of a city

manager. "Cincinnati's situation is to-day

unique in the completeness of

organization control and the degree of helplessness

18. Times-Star, October 20, 1923.

19. Post, November 5, 1923.

20. Ibid., November 7, 1923.

Cincinnati Post 237

of council," the committee

observed.21 Although the report was not entirely satis-

factory, this type of reorganization was

what the Post and other reformers were

seeking.

The Post liked the city manager

idea. On May 28 it had asked supporters of

nonpartisan government and the city

manager idea to unite. On July 29, the day

following the release of the Upson

Report, the Post editorial again called on Cin-

cinnatians to support proportional

representation and the city manager form of

government, stating, "Adoption of

the city manager plan will be equivalent to

exile for life-a fitting punishment for

the parasitical politicians, dominated by a

New York boss, who have brought distress

and shame upon the great city of Cin-

cinnati."22 The Times-Star

interpreted the Upson Report in a different way. It

argued that like other human

institutions, local government in Cincinnati was a

mixture of good and bad, and "It

has been our opinion that the good predominates."23

As a result of the recommendations made

in the report and the work of a non-

partisan city charter committee,

Cincinnati voters in November 1924 were given

the option of choosing one of three

possible amendments to the city charter, or

they could reject all three. Under

amendment one city government would remain

essentially the same except for two

changes: the number of councilmen would be

reduced to nine and they would be

elected from the city at large. Amendment two

called only for reducing the number of

councilmen to nine, but they would still

be elected from districts. The third

proposal was long and complicated and was

supported by those who sought basic changes

in the structure of city government.

Under this amendment the charter would

be changed to provide for nine city

councilmen to be elected at large on a

nonpartisan ballot by the Hare system of

proportional representation. Candidates

for council could be nominated by petition

only, not directly by parties. A mayor

would be selected by the councilmen, from

their number, but his powers would be

limited; and a city manager would be hired

to be the city's chief administration

officer. Amendment three also authorized city

council to appoint a commission to study

the charter thoroughly and submit other

revisions to the voters.

The Post liked amendment three

the best. During the late summer and early

fall of 1924, the paper backed this

proposition in a variety of ways. Editorials favor-

ing this amendment were run frequently,

as were letters to the editor in support

of a city manager and proportional

representation. Editor Fries knew how to make

the most of news in the campaign.

Speeches by Cincinnatus Association members

were covered, other reformers were

interviewed, and articles were printed describing

the experiences of cities that had

adopted city manager government. Seasongood

saw the Post's contributions as

primarily educational. Calling the newspaper a

"potent ally," he remarked

that it "helped familiarize the people with what we

were trying to accomplish and what our

opponents were trying to prevent. . . ."24

Segal, of course, threw the weight of

his column behind amendment three and also

covered many of the speeches discussing

the controversy.

The city's other dailies were divided on

the various proposals. The Times-Star,

which recognized that some changes were

needed in city government, liked amend-

ment one and called proposition three

"complicated, experimental and probably

21. Lent D. Upson, ed., The

Government of Cincinnati and Hamilton County (Cincinnati, 1924), 191.

22. Post, July 29, 1924.

23. Times-Star, July 29, 1924.

24. Seasongood, Local Government, 26.

238 OHIO

HISTORY

futile."25 The Commercial

Tribune, which depended on public advertising for much

of its income when the machine was in

control, did not particularly care for any

of the proposals and remained silent on

its amendment choice, repeating only the

Republican charge that proportional

representation might lead to "Sovietism."26 The

Enquirer favored amendment two and felt that the city manager

proposal, if adopted,

would only strengthen the Hynicka

machine since a small council and a city man-

ager with broad powers would be easier

for a political boss to control. Calling

upon Republicans to purge themselves of

"alien and reprehensible. leadership,"

the Enquirer told voters,

"Form means nothing; men everything."27

On November 3, the day before the

voting, the Post summed up its feelings in

a page one editorial which declared:

A vote against the city manager charter

would be a vote:

For Hynicka

For holes in the streets

For 10-cent car fare

For higher gas rates

For secrecy in government

For closed sessions of public officials'

negotiations on public utility contracts

For financial mismanagement that

constantly requires more bond issues and more tax

levies than come out of the taxpayer's

pocket

For all the other evils that result from

incompetent political mismanagement28

The hard work of the Post and

reformers paid off. The city manager charter

amendment won easily, receiving twice as

many yes votes as amendments one and

two combined, and more than twice as

many yes votes as no votes. The Post de-

clared, "The people have won a

great victory over government by politicians, and

by privilege. . . ."29

The next obstacle was to get candidates

of the newly-formed Charter party

elected to city council in November

1925. Six Republicans and three Democrats,

all pledged to reform, filed for council

under the sponsorship of the Charter party,

and the Post endorsed all nine of

them. "There are 39 candidates running for

Council, but The Post believes that only

by the united vote of all the friends of

good government can there be elected a

solid block of good government candidates,"

the newspaper explained.30 For

nine days immediately prior to the election, the

Post ran the name of one Charter candidate each day in large

type over its name-

plate and asked voters to "Memorize

This Name!" On the day before the election,

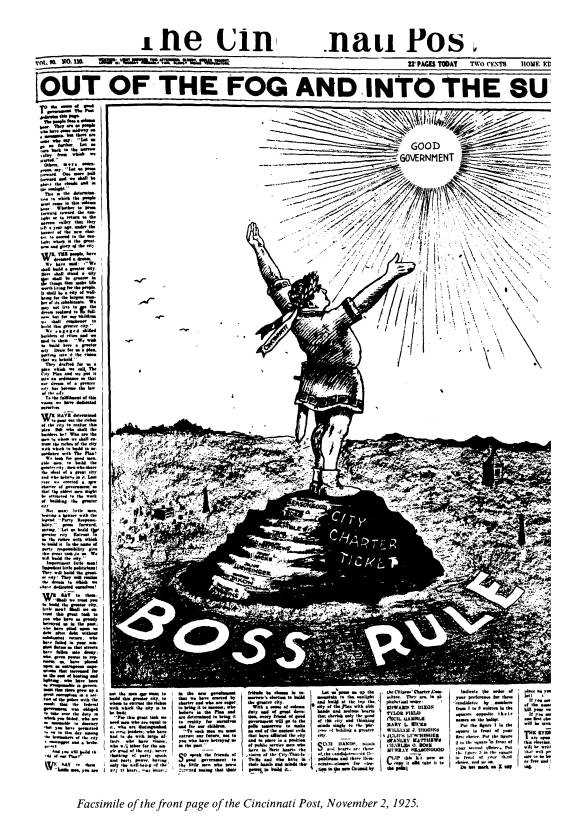

the Post ran a seven column

drawing by Claude Shafer showing "Cincinnati"

escaping the fog of "Boss

Rule" by climbing a mountain labeled "City Charter

Ticket" to look into the sun of

"Good Government." The Post added to the draw-

ing: "The eyes of the nation are

upon Cincinnati in this election. By its votes will

be written a message that will proclaim

its desire to be bossed and bled or free and

forward looking."31

The Times-Star endorsed six

Republicans and four Charterites, asking voters to

25. Times-Star, November 3, 1924.

26. Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, November

2, 1924.

27. Cincinnati Enquirer, November

2, 1924.

28. Post, November 3, 1924.

29. Ibid., November 5, 1924.

30. Ibid., October 29, 1925.

31. Ibid., November 2, 1925.

|

|

|

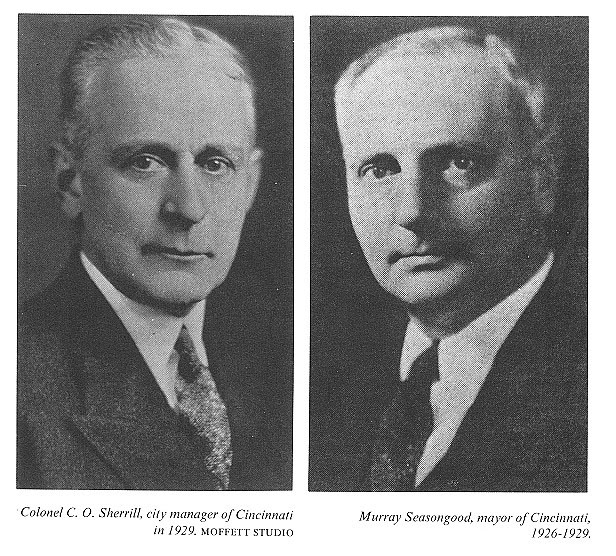

choose any nine of the ten candidates named.32 The Commercial Tribune backed nine "Republicans," although several Charter party candidates were included in its list.33 The Enquirer backed the Charterites, requesting voters to "Give the City Manager Plan of Government a fair trial at the hands of its friends."34 Six Charterites, including Seasongood, were elected to the nine-man council on November 3, 1925, and Seasongood was later named mayor by his fellow council- men. The forty-year domination of local politics by boss-ruled Republicans had come to an end. The Post declared: "The votes of the people have said that there shall be neither Republicans nor Democrats in the city government, but only pub- lic servants with minds single to the purpose of serving the city well." Segal sup- ported Seasongood for mayor, writing prior to his selection that he "possesses not only the qualifications, but is entitled to the recognition of the service he has ren- dered as a pioneer in the fight for better government." City council selected Colonel C. O. Sherrill, a West Point graduate who was Superintendent of Parks and Public 32. Times-Star, November 2, 1925. 33. Commercial Tribune, November 1, 1925. 34. Enquirer, November 1, 1925. |

Cincinnati Post 241

Buildings in Washington, D.C., as

Cincinnati's first city manager. Segal also en-

dorsed this choice, saying "He will

have no friends to reward here and no enemies

to punish. The great fault of city

government in Cincinnati has been that it has

been government by favor and government

for reward of insiders."35

The election of 1925 proved to be

"one of the great turning points of the Queen

City's history."36 The

power of the Hynicka machine in Cincinnati was broken,

and its boss retired in 1926. That same

year the charter was revised again to clarify

the city's home rule powers. The Charter

party and Sherrill put the city back on

its feet swiftly. Bond issues were passed

for a number of improved services, the

city's debts were paid, civil service

was reorganized, taxes were lowered, and out-

side investments flowed in as a result

of restored confidence in government.

The Charter party held a majority in

city council until 1941, and its efforts, along

with those of the talented city managers

who succeeded Sherrill, kept the govern-

ment running efficiently. When the GOP

recaptured control of council in 1941, it

was no longer boss-ridden and was

pledged to continue what the Charter party

had started.

After the 1925 election, other

newspapers than the Post soon began to support

the city manager government and the

Charter party. The least enthusiastic was the

Commercial Tribune. Although it praised Sherrill for his "unsurpassed

service,"

this paper considered many Republican

reformers to be "malcontents" who had

deserted the GOP only because they could

not have their way.37 The Enquirer paid

tribute to Sherrill and the Charterites

as early as 1927 but still felt that men were

more important than form.38 The

Times-Star felt much the same way, but in 1931

indicated it was for continuance in

power of the Charter party only "as long as

things go as well as they have been going."

In the same editorial it was also ad-

mitted that the Charter party had given

Cincinnati "a good city administration."39

The Post continued to be a

steadfast friend of the new city government and pro-

portional representation. While the

city's other dailies endorsed a mixture of can-

didates for city council during the

1930's, the Post endorsed all nine Charter

candidates at every city election until

1941, when two Republican candidates were

added to its list. Proportional

representation was the most controversial provision

of the new city charter. Neither the Times-Star

nor the Enquirer liked the system,

and other foes thought it was too

complicated or was based on appeals to minority

blocks. In 1936 and 1939 attempts were

made to eliminate this provision from the

charter, but the Post vigorously

defended it both times. When it was under siege

in 1936, the Post literally

borrowed a page from the 1936 PR Speaker's Manual to

editorialize: "The PR system is the

finest and most democratic system of election

that Cincinnati has ever had. . . . The

PR system has given union labor, the Negroes,

every minority able to muster a quota

vote, genuine representation in council with-

out overrepresenting the majority."40

In 1939, when another proposal to kill "PR"

was on the city ballot, the Post sent

a staff member to Kansas City, where there

35. Post, November 14, 16,

December 4, 5, 1925.

36. Louis Leonard Tucker, Cincinnati's

Citizen Crusaders: A History of the Cincinnatus Association,

1920-1965 (Cincinnati, 1967), 142.

37. Commercial Tribune, November

4, 1927. The Commercial Tribune went out of business on

December 3, 1930. It had been existing

on political subsidies for several years, and after Republican

defeats in Cincinnati and Hamilton

County it suspended publication.

38. Enquirer, November 6, 1927.

39. Times-Star, November 2, 1931.

40. Post, March 2, 1936.

242

OHIO HISTORY

was a city manager but not proportional

representation, to report on the Pendergast

machine's control of the city. As a

result of its study, the newspaper issued the

warning that those seeking repeal of

proportional representation in Cincinnati were

trying to reestablish bossism in the

Queen City. This Post campaign was credited

with turning possible defeat of

"PR" into victory.41

The Post won the lasting

gratitude of reformers for its part in starting the re-

forms and keeping watch to see that they

were successful. After the newspaper's

1939 defense of proportional

representation, civic leaders recommended the paper

for a Pulitzer prize. In a letter to the

Pulitzer committee, reformer and civic leader

Ed F. Alexander called the Post's defense

"extremely effective" and pointed out:

"For at least forty years [the Post]

has been the spearhead of every reform move-

ment in the city of Cincinnati.

Practically always it has fought alone among local

newspapers."42

The paper's local government crusades

from 1914 to 1941 gave the Post's staff

members a feeling of great satisfaction.

In 1931 Segal said that the staff considered

themselves "not merely hired hands,

but the bearers of a flaming spirit and the

voices of a brave and warm heart."43

Taking pride in what the newspaper helped

to accomplish, the columnist wrote,

"The motto which The Post flies from its mast-

head is: 'Give light and the people will

find their own way.' The Post rejoices that

the people by the light it has offered

have found their way."44

41. Ralph A. Straetz, PR Politics in

Cincinnati (New York, 1958), 246. Proportional representation

was finally voted out in 1957 after two other attempts

to kill it and was replaced by a "9X" voting

system. The Post defended PR

vigorously until the end.

42. Ed F. Alexander to Carl W. Ackerman,

January 25, 1940, Box 2, Folder 9, Ed. F. Alexander

Papers, Cincinnati Historical Society.

Civic leaders had also recommended the Post for a Pulitzer Prize

in 1931 after a crusade for county

government reform. On neither occasion did the newspaper win

the award.

43. Address by Segal to the Golden

Jubilee Celebration of the Cincinnati Post, January 12, 1931.

Located in Post and Times-Star library.

44. Post, November 5, 1930.