Ohio History Journal

OHIO

Archaeological and Historical

PUBLICATIONS

PREHISTORIC

EARTHWORKS IN WISCONSIN.

A. B. STOUT,

University of Wisconsin.

In presenting this subject it seems best

to the writer to treat

somewhat in detail the various classes

of earthworks and then

to give a summary for the state as a

whole with a brief discus-

sion of the archaeological area to which

it belongs. With this

plan in view the various artificial

earthen structures in Wis-

consin of prehistoric origin (at least

the greater number are

prehistoric) may be grouped into the

following rather well

defined types: enclosures, conical

mounds, flat topped mounds,

effigy mounds, linear mounds, intaglio

earthworks, refuse heaps,

garden beds and corn fields. Altho there

are some earth re-

mains that are intermediate between

various types, the above

classification serves to good advantage

for discussion and com-

parison, and may well be treated in the

order given.

Few enclosures exist in Wisconsin. Yet

the most famed

of the earthworks within the state is an

enclosure with accom-

panying earthworks which has been called

the Aztalan ruins.

It would be of no special value to

present here a review of the

literature pertaining to these

earthworks. Those who desire

this will find that West (I) has

recently made a complete his-

torical summary together with a critical

analysis of the literature

on Aztalan.

These remarkable ruins are now badly

mutilated by long

Vol. XX-1. (1)

|

2 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

cultivation of the land, but there can be little question concerning the main features as described by Hyer (I) and later by Lap- |

|

|

|

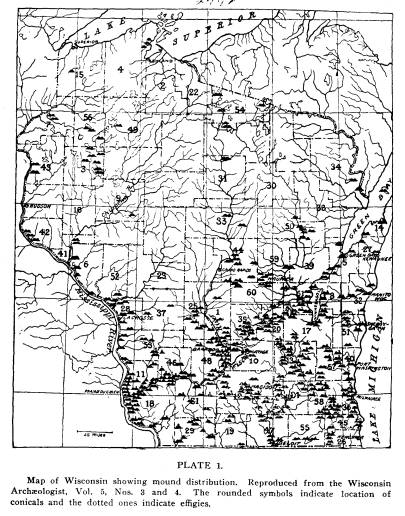

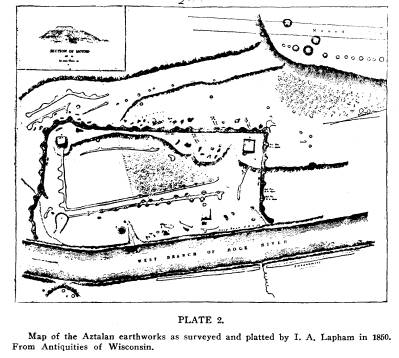

ham (I). The main wall formed three sides of an irregular parallelogram with the river forming the fourth side (See plate 2). The total length of the wall as given by Lapham was 2,750 |

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 3

feet. The width was about 22 feet and the height was from one to five feet. It enclosed 17 2/3 acres. Along its outer edge were projecting "bastions" which in some cases resembled con- ical mounds. At a few places (and only at a few points) on the surface of the wall a shallow layer of burned clay was found. The presence of this burned clay has led to unwarranted descriptions of a ruined "brick" wall. The wall was made of |

|

|

|

dirt taken from numerous excavations in the immediate vicinity. The clay "brickets" are most probably the remains of clay plastered huts. Within the enclosure were various earthworks. At least three were flat-topped, pyramidal mounds with graded ap- proaches and in one case with terraced sides. The largest was 15 feet high with a level top 53 feet square. Lapham (I) noted within the enclosure some two dozen circular mounds resembling |

|

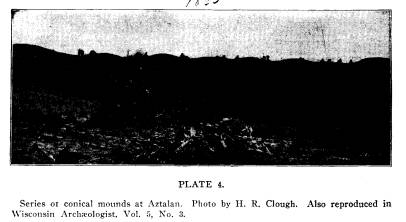

4 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. hut rings. Effigy mounds probably existed within the enclosure and linear and conical mounds were quite numerous in the im- mediate vicinity. Some of the latter which were 25 feet high in 1837 still show as conspicuous features (See plate 4). It is greatly to be regretted that the various efforts made to preserve these earthworks were not successful. Seventy years of continuous cultivation over the greater portion of the |

|

|

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 5

earthworks has so effaced the finer features that many im- portant questions can not be determined. In the light of the present knowledge of American archaeology the surface features might be interpreted readily. The judgment of to-day is that here was an inclosed Indian village. The presence of effigy mounds in and about the enclosure, of conical burial mounds, and of the abundance of Indian artifacts found on the site, all of which are characteristic of the archaeology of the region, leads to the conclusion of West (I) that Aztalan was "the site of a permanent village of prehistoric Indians of the effigy mound period." Besides the Aztalan enclosure some 20 other but smaller |

|

|

|

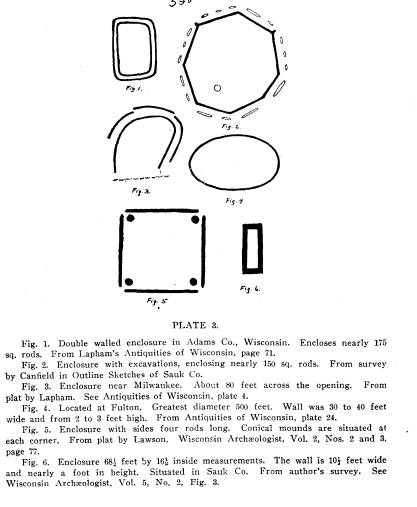

enclosures have been reported in various parts of the state. These include oval, square, rectangular, octagonal and horse- shoe shaped enclosures. A few of these are shown in Plate 3. Some are evidently the earthen remains of fortified areas, others were dance or play grounds and others lodge sites. Among the enclosures are several in the Green Bay region that are as- sociated with Indian villages of historic date. The enclosures of Wisconsin do not constitute an important or a distinguishing feature of its archeological remains. The best of them do not compare in extent or in exactitude of design to the numerous hill forts, enclosures and defensive walls of |

|

6 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Ohio. They are few in number, simple in plan of construction and of varied use. They give evidence of sporadic and feeble attempts at fortification, and of exceptional rather than general use of dirt walls in the construction of buildings. They are as- |

|

|

|

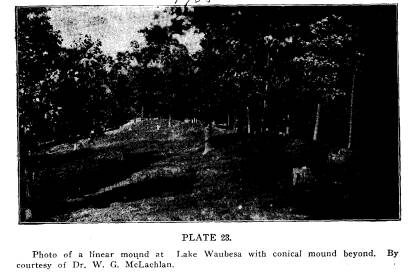

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 7

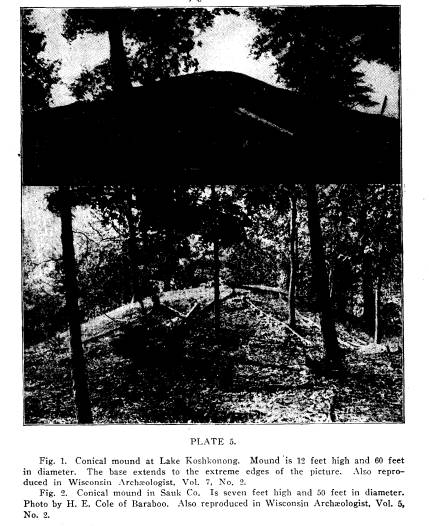

sociated with various other types of earthworks and with village sites in a manner which marks them as the work of Indians. In taking up the discussion of conical mounds we have to consider the type of mound most extensively distributed over the mound bearing area. Externally they are dome shaped heaps of dirt appearing to the eye as shown in plates 4, 5, and 6. In Wisconsin conical mounds range in diameter at the base from 10 to nearly 100 feet and from a few inches to about 25 feet in height above the surrounding level. Most of them are less than ten feet in height. |

|

|

|

The various modes of burial in these mounds do not admit of a satisfactory classification. Either stones were first used to construct a rude vault, or bark and logs were used for the same purpose or the remains were directly covered with dirt. When stones were used their arrangement varies from a low stone wall surrounding the remains to a rough vault of stones piled over the body. In the latter case if the dirt layer was originally thin, or possibly even omitted, the structure would now appear as a cairn burial. Lawson (I) has described about 30 cairns located in the vicinity of Lake Winneconne which are |

|

|

|

|

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 9

This feature is the result either of successive additions to a mound or of the employment of different soils which were laid on in layers. In any of the above cases one or many bodies may occur in a single mound. The body or bodies were either placed prostrate or in a sitting position with the feet extended or in a sitting position with the feet folded under the body. Burials were made below the original surface of the ground, on the |

|

|

|

dence as layers of ashes with charcoal or even charred and partly consumed timbers. A considerable number of mounds have been opened with the view of carefully studying the method of burial but these cases are few compared with those that have been ruthlessly opened by relic hunters. Various artifacts are often but not always found beside the remains of the dead. Of these pottery vessels, arrow points, stone axes, and pipes are most common. In the majority of mounds there is no evidence that they were built since the advent of the whites, yet there are numerous authentic records |

|

10 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

of the presence with the original burial of such articles as glass beads, iron implements, gun flint, copper kettles and even in one case (Hoy I) of "a small fur covered brass nailed trunk" containing cheap jewelry. These facts clearly indicate that some of the conical mounds were constructed after the establishment |

|

|

|

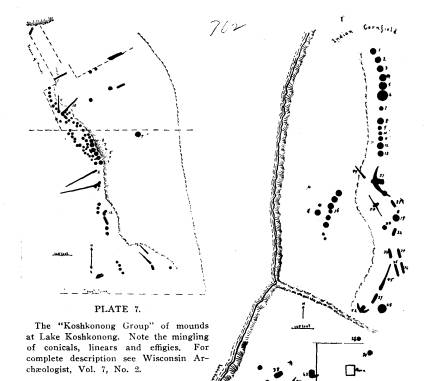

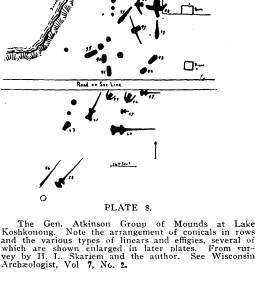

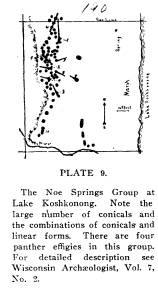

to be arranged in long rows as shown in plates 8 and 10, an archaeological feature characteristic of the so-called Wisconsin District (Thomas I). Short chains of conicals with edges over- lapping occur as indicated in plates 9 and 22. Conicals with linear connections are not uncommon (See plates 9 and 22). In regard to numbers the conicals far exceed the total of |

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 11

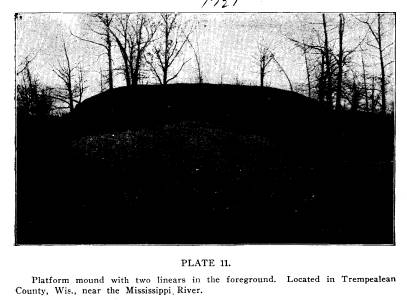

all other mounds in Wisconsin. Some data on this point will be presented later. The oval mound differs from the conical only in having an oval base. They are less frequent and shade into the short linear type. In Wisconsin flat topped and truncated pyramidal mounds are few in number. A few low broad topped "platform" mounds are found along the Mississippi River (See plate II.) Lapham |

|

|

|

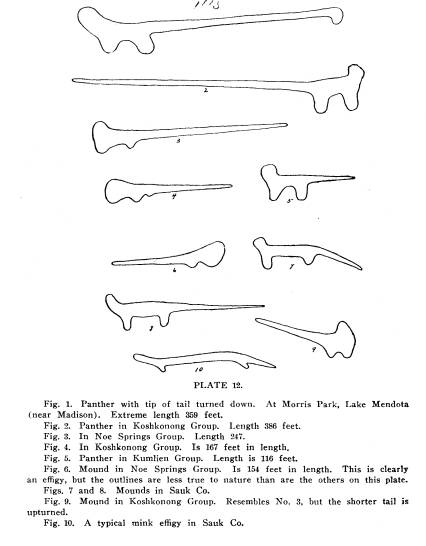

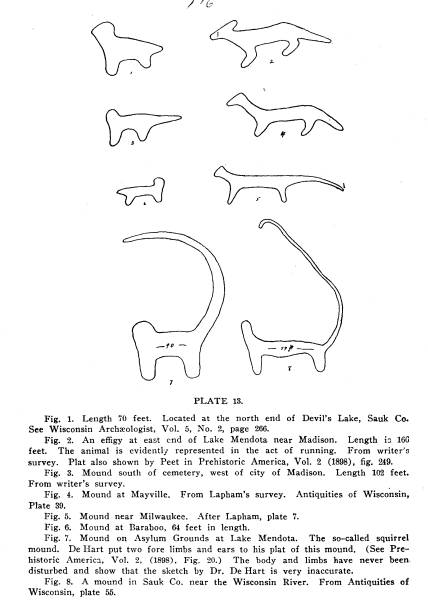

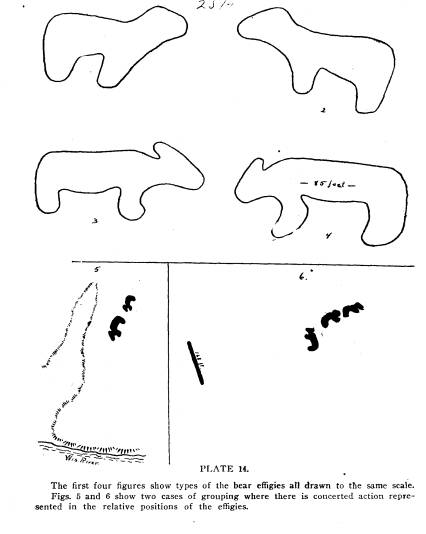

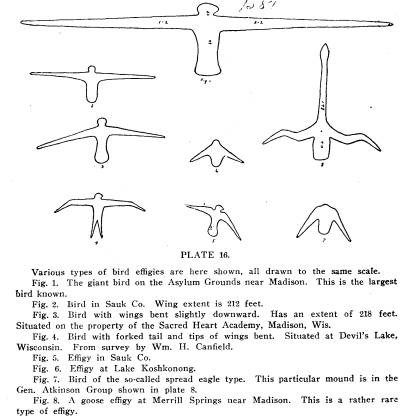

reported several pyramidal mounds nearly all of which were at Aztalan. We now come to the most interesting and remarkable of Wisconsin antiquities, the effigy mounds. These are dirt cameos built in the form of various animals or in some cases possibly to represent inanimate subjects. Some of the animals most accurately represented are the turtle, deer, mink, panther, bear, various types of birds and in at least two cases the human figure. Some are rather crude in outline but the greater number are well formed and of good proportions as can be seen in the plates |

|

12 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

illustrating this article. There is some degree of exaggeration in the extenuated tails of many of the turtle and panther effigies, but in the majority of cases the art displayed is realistic. This is especially shown in the fact that the animal is represented as it is usually observed in nature. The turtle, frog and lizard- |

|

|

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 13 |

|

|

|

14 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

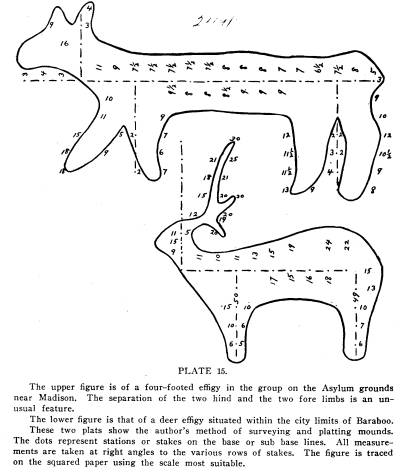

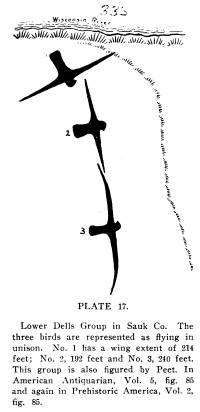

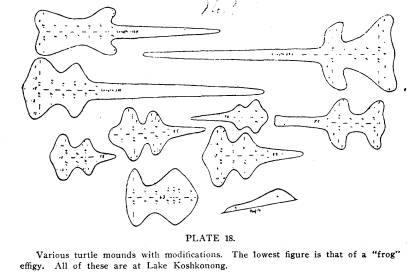

like effigies (See plate 18) are built with the limbs at each side of the body, thus representing the animal as it appears when one looks down on it. Birds of the air (Plates 16 and 17) are shown as they appear when flying overhead and often the bill is shown as if the head were turned to one side. The forked tail and curved wings are present in some cases (See plate 16). |

|

|

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 15

Land mammals as the bear, deer, mink and panther are repre- sented in profile which is the view one has of the animal either when alive or dead. In these, however, the two hind limbs and the two fore limbs are respectively united in the effigy, but in |

|

|

|

a few cases (As in plate 15) all four limbs are shown in the profile making the figure more realistic. The height of the majority of the effigy mounds is about 21/2 or 3 feet, altho a few are as high as 6 feet. Bear effigies |

|

16 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

range in length from 39 to 82 feet in length and birds with wings extended from 100 to 624 feet. The bird in the group on the State Asylum Grounds near Madison (See plate 16) is according to the data at hand, the largest bird effigy in existence. Its body stands six feet in height and the wing extent is 624 feet. During the field assembly of the Wisconsin Archaeological |

|

|

|

Society held during the summer of 1910, a tablet was erected on this mound with appropriate exercises. Effigies are in many cases grouped with linear and conical mounds (Plates 7, 8, 9 and 10) altho they may be found either singly or in groups entirely separated from mounds of any other |

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 17

class (Plate 17). In an individual group several types of effigies may be present and there may be duplicates of one or more types. In the arrangement of the effigies in a group no uniform method was followed, altho there is a tendency for them to be included with conicals in a long row. As a rule the effigies in a group bear no apparent relation to each other. Still in some |

|

|

|

is adequate statistical data. For the purpose of illustrating various points regarding the number and the distribution of the various types, two typical areas can be taken from the midst of the effigy bearing region. In seven townships in Sauk County the writer located 734 Vol. XX-2. |

18 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

mounds.

About 50 miles southeast of Sauk County lies Lake

Koshkonong

with a water surface of nearly 13 square miles.

The

following table shows the principal facts in the comparison

of

these two areas.

Sauk

Co. Area. L. Koshkonong Area.

Area

in sq. miles............. 200 31

Total

No. mounds ............ 734 481

" "conicals............ 337 309

" " effigies

............. 183 42

" " bear effigies........ 47 0

" " mink effigies....... 12 1

" " bird effigies........ 43 10

" " turtle effigies ....... 0 9

It

is to be noted that the effigies are less numerous than are

the

conicals. This is true of any given area. The character of

the

effigies in these two areas is different. The bear type so

abundant

in Sauk County is absent at Lake Koshkonong.

Twelve

mink are found at Sauk County and but one at Lake

Koshkonong.

The 43 birds in Sauk County have the wings ex-

tended

while nearly all of those at Lake Koshkonong are of a

very

different type with drooping wings as shown in No. 9,

plate

16.

The

above illustrates the fact that the dominant types of

various

areas are different. Peet (I)

has divided the effigy

bearing

area into seven clan habitats on the basis of the pre-

ponderance

of one type of effigy. While this division is based

on

incomplete data it is suggestive of what will be revealed if a

complete

census of the effigy mounds is ever made.

Any

discussion of effigies should not be concluded without

some

mention of the remarkable man mound at Baraboo, Wis-

consin.

In the early records of Wisconsin antiquities and in

some

later ones, it has been stated frequently that there are

numerous

mounds representing the human figure. The surveys

of

these, however, show the upper limbs to be greatly dispro-

portionate

to those of the human figure and that in many cases

there

is no suggestion of the lower limbs. A careful study of

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 19

this phase of Wisconsin archeology leads to the conclusion that there have been reported but two mounds with outlines that are true to those of the human figure. Both of these are located in Sauk County, which is geographically near the center of the effigy bearing area. Both were carefully surveyed by Wm. H. Canfield, a pioneer surveyor and archaeologist of Sauk County, who contributed several surveys to the work on Wisconsin An- tiquities by I. A. Lapham. One of these effigies known as the La Valle Man Mound has been leveled by cultivation and but for Mr. Canfield's timely survey all accurate data regarding it |

|

|

|

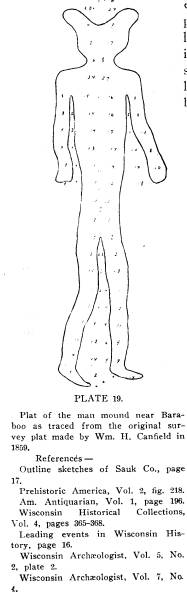

would be unavailable. The second and more perfect effigy lies near Baraboo. Its original length was 214 feet, but nearly 60 feet of the lower limbs have been destroyed by the construction of a public highway. The outline given in plate 19 was traced by the writer from the original plat made by Mr. Canfield in 1859. The head, arms, trunk and upper part of the legs are still well preserved. The outlines are definite and well formed and the resemblance to a human figure is in no way exaggerated in the survey. In height the mound is nearly uniformly 21/2 feet. It will be seen from the survey that the limbs are short in pro- |

20 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

portion to the length of the body and

that the figure is in the

attitude of walking toward the west. The

horn-like projections

which evidently represent a head dress

are noticeable features.

Through the activity of the Wisconsin

Archaeological Society, the

Sauk County Historical Society and the

Wisconsin Federation

of Woman's Clubs a public subscription

was raised and purchase

made of enough land surrounding the

mound to make a small

park. For complete data regarding the

preservation of this

mound those who are interested are

referred to Vol. 7, No. 4,

of the Wisconsin Archaeologist. In

comparison to these two

readily recognizable effigies of the

human figure the other

"man mounds" seem clearly to

be representations of birds or at

the least grotesque forms of a human

being.

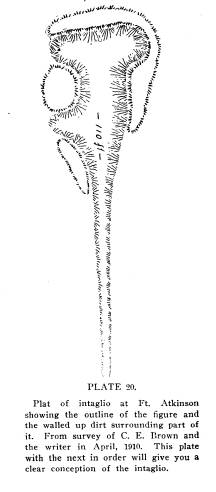

Associated with effigy mounds in a few

locations were earth-

works known as intaglios. In the

construction of these the dirt

was dug away and the form of the animal

represented in the

excavation, a method which is the

reverse of true mound con-

struction.

But eleven intaglios have ever been

reported. Nine of these

were figured by Lapham and the other two

were reported by his

contemporary Wm. H. Canfield. The plats

and descriptions

which these two men made some half a

century ago, give nearly

all that will probably be known

concerning intaglios. No others

have been found, and of the nine

reported all but one have been

destroyed. This one is located at Ft.

Atkinson. In form it is

of the rather common type known as the

panther mound. In

length it is 108 feet. The greatest

depth of 21/2 feet is in the

body, the depth of which is increased by

the dirt piled up at

the margin of the excavation. The tail

is a slight but decided

excavation and toward the tip it

gradually merges into the gen-

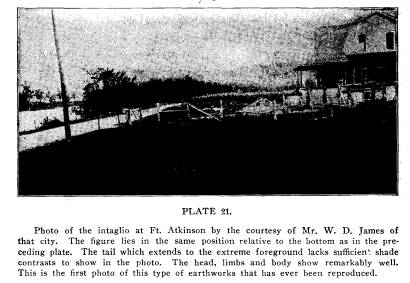

eral level. The photograph reproduced in

plate 21 shows quite

well the configuration of the body, head

and limbs. As a class,

intaglios constitute a unique and

distinctly local feature. Their

designs relate them to effigy mounds.

One is a cameo, the other

is an intaglio.

In distribution the effigy mounds are

almost exclusively lim-

ited to the southern half of Wisconsin.

A few are found in

adjoining portions of Illinois, Iowa,

and Minnesota. The noted

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 21

"serpent mound" and three other mounds in Ohio are undoubt- |

|

|

22 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

(Jones I). These resemble the earth

effigies of Wisconsin ex-

cept that they are constructed of

stones. The boulder mosaics

of the Dakotas are simpler in

construction for they consist of

the figure in outline.

The mounds thus far considered as

effigies are those that

clearly represent some animal more or

less recognizable. There

are, however, various types of linear

mounds and combinations

of conical and linear forms that may

have been constructed to

symbolize inanimate things and hence may

be called conven-

tionalized effigies.

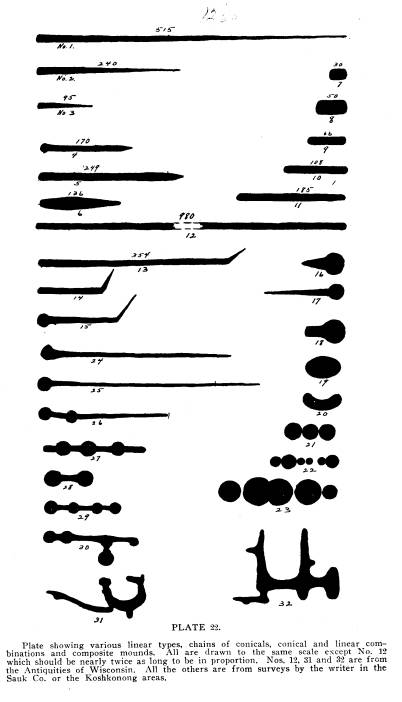

The principal classes of linear mounds

are as follows:

The pure linear type is a straight wall

like mound of uni-

form width and height. They are usually

about 21/2 feet in

height and from 10 to 20 feet in width. Some are so short

that they approach the oval and platform

mound types, while

the longest are over 900 feet in length.

For relative sizes of

this type see numbers 7 to 12 of plate 22.

The straight pointed linear is usually

of considerable length

and differs from the pure linear as

given above in having one

end tapering to a long drawn out point.

(See Nos. 1, 2 and 3,

plate 22). Variations from this type are

to be found in which

the pointed end may be bent to one side

at an angle (See num-

bers 4, 5, 13, 14, of plate 22).

Club shaped linears are frequently found

(Plate 22, No. 6)

and kidney shaped linears are not

wanting (No. 20, plate 22).

The various linear types described above

are sometimes

modified by an enlargement at one end

(See Nos. 4, 15, 16 and

17, plate 22). This ranges from a low,

flattened enlargement

to a rounded, well built conical mound.

Various projections or

appendages to some of the linear forms

(Fig. 25, plate 22) give

figures that shade toward effigies

proper. These types of linear

mounds are mingled in the mound groups

as shown in the vari-

ous group plats (Plates 7, 8, 9, and

10). The studies and

observations of the linear mounds made

in the field from purely

an archeological point of view have

convinced the writer that

the linear mounds of Wisconsin are

really effigy mounds erected

with symbolic meaning.

Besides the types already discussed

there are peculiar com-

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 23

binations and composite mounds (See plate 22, Nos. 30, 31, and 32) which do not admit of any rational explanation. As Fowke (I) aptly says regarding the anomalous earth structures of Ohio, "The builders of such figures probably knew what they were about, but we cannot even guess at their thoughts or intentions." Refuse heaps do not constitute a conspicuous feature on many of the Wisconsin village sites, yet they deserve some men- tion. The ones most noticeable are low and flattened heaps of various remains of camp refuse. No extensive explorations of village sites and refuse heaps have been carried on in Wis- consin. |

|

|

|

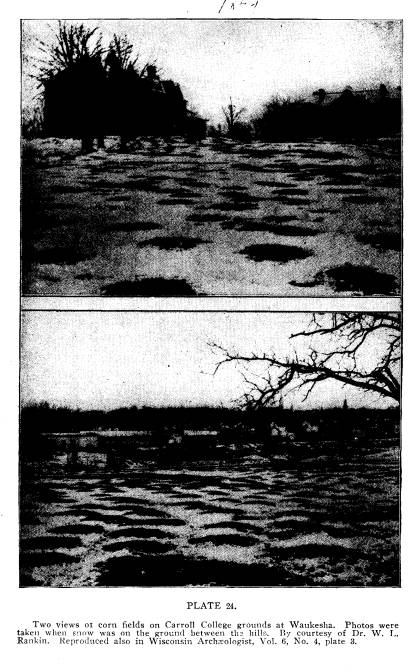

Corn fields are associated with many of the village sites. Where they have not been disturbed by the white man's culti- vation they are easily recognized. The hills are often 11/2 feet in height and about 3 feet apart. Each hill is a dome shaped pile of dirt the result of continued heaping up of the soil. The photos reproduced in plate 24 show well the appearance of a typical Indian corn field. The largest fields comprise at least 40 to 60 acres but usually the fields are much smaller. In at |

24 Ohio Arch. and

Hist. Society Publications.

least two places in the lake Winnebago

region [Lapham (I)

and Lawson (2)] the stones

scattered over a field "had been

carefully collected into little heaps

and ridges to make room for

the culture of crops. The stone heaps

are six to eight feet in

diameter and from one to two feet

high."

The present appearance of garden beds is

fairly well shown

in plate 25. As the name implies these

are patches covered with

ridges or beds. The best of these as

described by Lapham (3)

were "one hundred feet long, and

had a uniform width of six

feet. The depressions (paths) between

the beds are 8 inches

deep and 15 inches wide. Mr. Charles E.

Brown has recently

collected all the data on Wisconsin

garden beds (Brown I). He

finds that they are present in 17

different localities which are

nearly all in the eastern part of the

state between Green Bay

and Racine. They are of small area and

are laid out in simple

patterns displaying no such elaborate

designs as are reported in

Michigan. Garden beds are so often

intimately associated with

corn fields, village sites and mound

groups that they must be

ascribed to the same builders.

We have now considered the character of

the principal

archaeological features that may be

considered as within the

range of the title of this paper. In

regard to their general dis-

tribution it is to be noted that there

are but five counties which

at the present time have no record of at

least some of the vari-

ous classes of earthen remains. The most

recent archaeological

map of the state appeared in 1906 and is

here produced (See

plate I) as it appeared in the Wisconsin

Archaeologist, Vol. 5

Numbers 3 and 4. It shows in a grapic

way the main facts in

the distribution of conicals and

effigies. By far the greater

number of mounds are in the southern

part of the state along

the principal lakes and streams.

It is difficult to make an accurate estimate

of the total

number of mounds in the state for there

are but a few areas

in which a complete census has been

made. The author would

judge from the data at hand that there

are at least 20,000 conical,

linear and effigy mounds in the state.

The purposes for which most of these

earth works were

constructed are evident from the

foregoing. The difficult points

|

26 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

in this question are concerned with the effigy and linear mounds. In regard to the former it is now generally conceded that they were built as totems in connection with the clan system of In- dian organization. To the writer the only satisfactory explana- tion of the linear mounds is to assign them to the effigy class. The various types of linears which have been, from time to time, considered as defensive walls may be found on the crests of narrow ridges, or extending down the slopes of steep hill- sides, or even extending over a series of undulating ridges in such relation to each other and to the immediate topography that the theory of their use as a means of defense or as house |

|

|

|

sites must be rejected. Human remains are so seldom found in linear mounds that it is clear they were not built for pur- poses of burial. Rev. Peet's views regarding their use as game drives are not accepted by archaeological students. From the preceeding discussion of linear mounds it is evident that there are intermediate or transitional forms between the linears and the pure effigy types with which they are mingled. It must be admitted however that various elongated mounds extend west- ward into Minnesota and Manitoba beyond the limits of the |

Prehistoric Earthworks in

Wisconsin. 27

pure effigy types. Yet the character and

extent of these linears

are not adequately known. In fact no

satisfactory study has

been made of the range, number, and

classification of the vari-

ous types of linears and effigies. What

is most needed at pres-

ent is a complete systematic field

survey, not of isolated areas

here and there but of the entire area.

This would make clear

many perplexing questions and give

abundant data to correlate

with that obtained from historical and

ethnological sources.

In the minds of the readers of these

pages there will arise

many legitimate questions pertaining to

the authorship of these

earthworks. A complete discussion of

this problem is not in

place here. Fortunately West (I) has

recently compiled a work

of nearly 200 pages in which he discusses all

phases of the

problem. For the benefit of the readers

of this article the greater

part of the conclusions which he deducts

will be quoted although

it is hoped that those who are

especially critical will read the

entire discussion given by West upon

which the following con-

clusions are based.

1. The entrance of the principal

mound-builders into Wis-

consin appears to have been from the

south and southwest.

Other tribes, who erected some of the

more recent conical tumuli,

entered from the north and east.

2. The

effigy mounds and other earthworks closely associ-

ated with them were erected during the

same period, and by the

same tribe or culturally related tribes.

3. No information that we now possess

concerning the

earthworks of our state justifies the

conclusion that they are uni-

formly of great antiquity. The evidence

is plain that of the

burial mounds some were erected in early

historic times. The

date of the erection of the oldest mound

groups may safely be

placed at not to exceed three centuries

previous to the discov-

ery of America by Columbus.

4. The enclosure and closely associated

works at Aztalan

are the remains of an Indian village.

None of the Wisconsin

earthworks were built for purely

religious, and none for sacri-

ficial purposes. Cremation was not a

usual practice, but the

use of fire in burial ceremonies was a

common custom among

our ancient Indians.

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 29

5. The mounds explored give conclusive proof that the cul- ture status of their authors was practically the same as that of the early historic tribes. Their social conditions, domestic and burial customs are not found to differ. They alike lived in villages, manufactured such implements as their manner of life required, depended for subsistence on agriculture and the chase; carried on a traffic with distant tribes, understood the art of war and defense and used the streams as their principal highways. 6. That the Wisconsin earthworks were erected by the |

|

|

|

Indians is now so well established as to scarcely admit of ar- gument. That the authors of the effigy mounds were of Siouxan stock, probably the Winnebago, is a hypothesis that appears to be well founded. The author predicts that it will be ac- cepted as an undisputed fact, within the present generation. 7. From the evidence at hand, the occupation of Wisconsin soil can be classed in but two principal periods. The first be- ing the effigy mound-building era, during which all classes of earthworks were constructed; second, the time elapsing since the custom of erecting imitative earthworks ceased. |

30 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

In conclusion a word should be said

concerning the archaeo-

logical area to which the Wisconsin

region is related. Thomas

(I) has divided the entire mound bearing

area into several dis-

tricts each with a more or less marked

individuality in the char-

acter of the mound remains. According to

this division the area

included in N. Dak., S. Dak., Minn.,

Wis., adjoining portions of

Canada, the extreme northeastern portion

of Iowa and the north-

ern portion of Illinois constitutes what

is called the "Dakotan

District." The features

characteristic of this area are boulder

outlines, effigy mounds, linear or

elongate mounds, connected

series of conical mounds and long rows

of conical mounds.

While these classes show various

relationships that war-

rant this grouping they are not

characteristic of the area as

a whole. Boulder outlines are confined

to the western portion

of the arena as defined. Pure effigies

are chiefly confined to

Southern Wisconsin and it is in this

portion of the so-called

Dakotan District that all the

characteristic features excepting

boulder outlines reach their best

development.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT.

Certain portions of this article are

here given as written in

a paper on "Effigy Mounds and

Mosaics in the Valley of the

Mississippi" presented by the

writer before the Mississippi Val-

ley Historical Society at the annual

meeting for 191O and which

will appear in the proceedings of that

Society.

Many of the figures and plates

illustrating this paper have

appeared in various numbers of the

Wisconsin Archaeologist and

are here reproduced by permission.

For the above favors the writer wishes

to express here his

thanks to the above named organizations

and to the various in-

dividuals named in references and in

descriptions of plates.

REFERENCES CITED IN THE TEXT.

BROWN - Charles E. Brown.

1. Wisconsin Garden Beds, Wis.

Archaeologist, Vol. 8, No. 3.

FOWKE- Gerard Fowke.

1. Archaeological History of Ohio, page

295.

|

Prehistoric Earthworks in Wisconsin. 31

HYER - N. T. Hyer. 1. Milwaukee Advertiser, Feb. 25, 1837. HOY--Dr. P. R. Hoy. 1. Who Built the Mounds? (Racine 1886). JONES -C. C. Jones. 1. Smithsonian Report 9, 1877. LAPHAM - I. A. Lapham. 1. The Antiquities of Wisconsin. Smith. Cont. to knowledge, vol. 7, 1855. 2. Same. Page 61. 3. Same. Page 57. LAWSON -Hon. P. V. Lawson. 1. Wis. Archaeologist. Vol. 2, No. 1. 2. Same. Page 30. PEET-Rev. Stephen Peet. 1. Wisconsin Academy of Sciences. Vol. 8, page 299. THOMARS - Cyrus Thomas. 1. Twelfth Annual Report Bureau of Ethnology. WEST-Geo. A. West. 1. The Wis. Archaeologist. Vol. 6, No. 4. |

|

|